Executive Summary

The announcement of a framework for a trade agreement between Thailand and the U.S. on October 26 might be considered “good news” by many parties. However, Thailand had to make substantial concessions to the U.S. in exchange for a reciprocal tariff of 19%, which is higher than the Effective Tariff Rate (ETR) previously imposed on Thailand, averaging only 0.7%. Meanwhile, Thailand remains subject to product-specific tariffs under Section 232 at the same rate as most countries and risks facing strict enforcement of a transshipment tariff in the future.

One of the key concessions Thailand had to make was eliminating tariffs on U.S. goods, covering 99% of all products. We estimate that such a concession could lead to a significant increase in Thailand’s imports from the U.S., further exacerbating the existing influx of Chinese goods and resulting in a “Twin Influx.” Furthermore, even if the U.S. Supreme Court were to invalidate the reciprocal tariffs, the U.S. could still use other legal instruments to impose tariffs at levels comparable to current rates.

Regardless of whether “the price Thailand has to pay” is ultimately worth it, we cannot deny that the Thai economy is currently facing growing risks. Thus, Thailand needs to swiftly reduce its reliance on the U.S. market, seek new trade partners, and expand cooperation with existing partners simultaneously. This is to allow Thailand to regain more autonomy in conducting proactive trade policies. It is also necessary to prepare support measures for Thai businesses in advance in a “prudent, comprehensive, and rigorous” manner. These changes will enable Thai businesses and the export sector to grow strongly and sustainably under a “Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous” (VUCA) world.

Recent Developments on U.S. tariffs

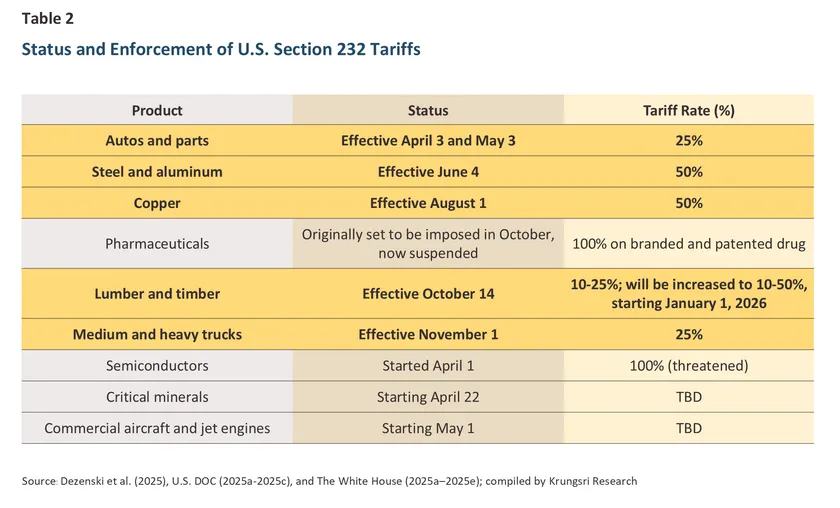

After Donald Trump began his second term at the beginning of this year, the U.S. announced that it would impose tariffs on various countries, which can be classified into two main groups: 1) Reciprocal tariffs, imposed on almost all products at the same rate, and 2) Section 232 tariffs under the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, imposed on certain products, including autos and parts, steel and aluminum, copper, lumber and timber, and trucks. Meanwhile, many countries have reached a framework for a trade agreement with the U.S. to reduce such tariffs in exchange for increased imports and market access for U.S. goods, reduced tariff and non-tariff barriers, and expanded investment in the U.S.

Reciprocal Tariffs

Even though reciprocal tariffs might be ruled invalid, the U.S. can still use other legal instruments to impose tariffs at levels close to current rates.

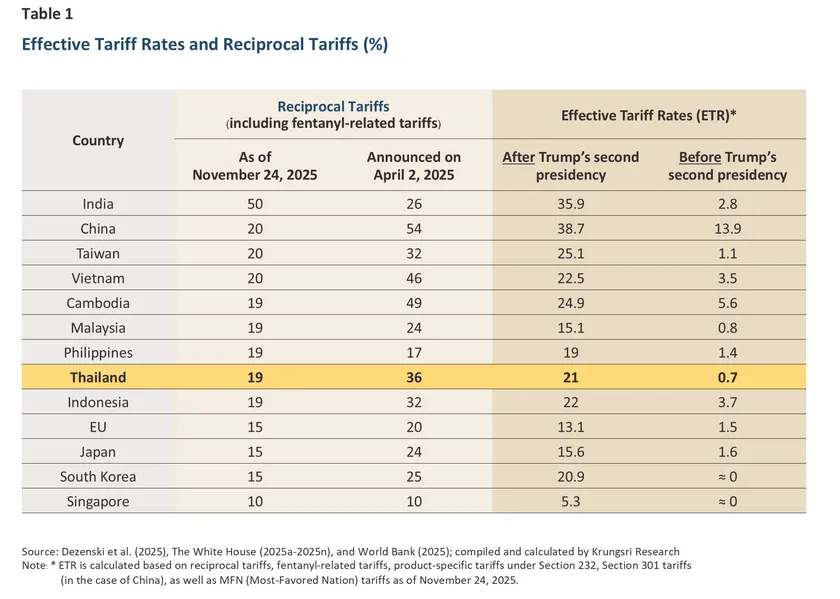

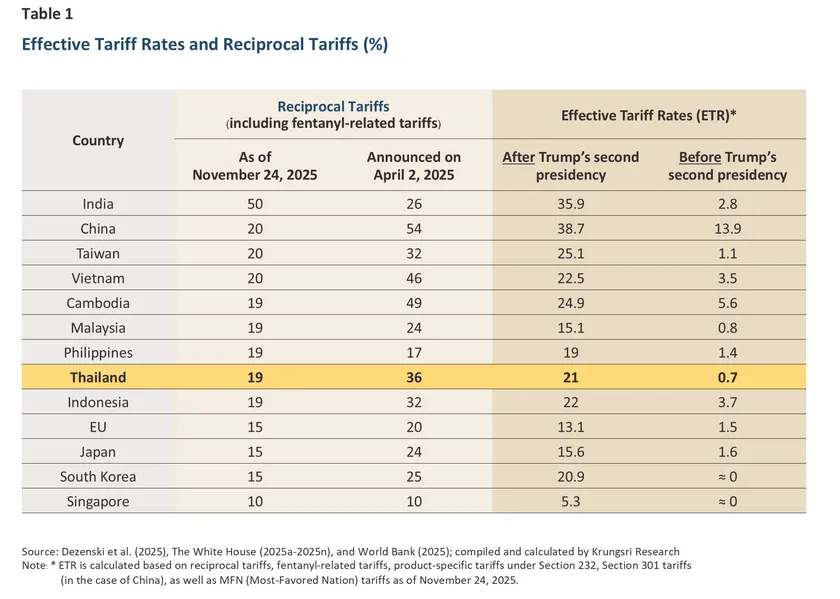

Although the U.S. has significantly reduced reciprocal tariff rates from those originally announced on April 2, 2025, these rates remain substantially higher compared to the Effective Tariff Rates (ETR) the U.S. previously imposed on various countries at very low levels (Table 1). Specifically, the U.S. now imposes a reciprocal tariff on Thailand at 19%, down from the 36% announced on April 2. While this rate is close to those of other ASEAN nations such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Cambodia, it remains higher than those for certain countries, including South Korea, Japan, the EU, and Singapore. Moreover, it far exceeds the ETR previously imposed on Thailand, which averaged only 0.7%.

The imposition of the reciprocal tariffs is carried out under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which is currently facing legal challenges in court. On August 29, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the ruling of the Court of International Trade (CIT), stating that the reciprocal tariffs constituted an overreach of authority. However, the reciprocal tariffs remain in effect for now. The Supreme Court of the U.S. (SCOTUS) granted a fast-track review, hearing arguments on November 5, 2025. It is expected that the Supreme Court will issue a ruling as early as the end of 2025 or early 2026 (Krungsri Research, 2025a, 2025b; Rodriguez, 2025).

If the Supreme Court upholds the rulings of the appellate and lower courts, the U.S. would no longer be able to impose the reciprocal tariffs. However, the Trump administration could still utilize other legal instruments to impose additional tariffs at levels close to current rates, including 1) Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974, which authorizes tariffs of up to 15% for no more than 150 days, 2) Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930, which authorizes tariffs of up to 50% on countries that discriminate against U.S. commerce, and 3) an expansion of Section 232 under the Trade Expansion Act, which could cover a wider range of products (Gottlieb, 2025; Krungsri Research, 2025a).

Product-specific Tariffs under Section 232

Thailand continues to face Section 232 tariffs at the same rates as most countries, despite reaching a framework for a trade agreement with the U.S.

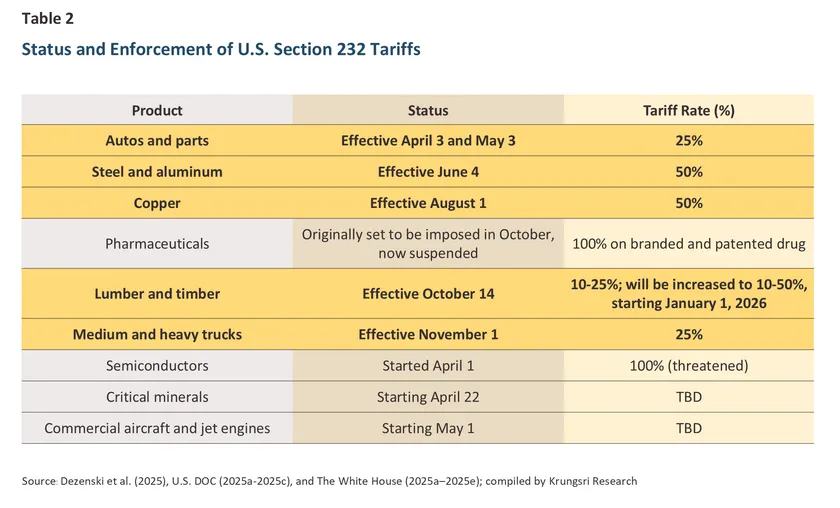

Section 232 tariffs are imposed on the grounds of national security and require an investigation prior to enforcement. As of November 24, 2025, goods currently subject to such tariffs include autos and parts, steel and aluminum, copper, lumber and timber, as well as medium and heavy trucks (Table 2). At the same time, the enforcement of tariffs on pharmaceuticals has been postponed and will target only branded or patented drugs. Furthermore, pharmaceuticals may qualify for future exemptions from reciprocal tariffs, as outlined in the annex of Executive Order 14346 (Potential Tariff Adjustments for Aligned Partners: PTAAP) (The White House, 2025m).

Although certain goods are currently exempt from reciprocal tariffs, they may face Section 232 tariffs in the future. The U.S. plans to expand the scope of such tariffs to other goods, particularly semiconductors. Trump has threatened to raise tariffs on semiconductors to as high as 100%, with exceptions for the EU and Japan due to their existing trade agreements (which cap tariffs at a maximum of 15%). However, regarding Thailand and other ASEAN nations, which preliminarily agreed to a framework for a trade agreement on October 26, 2025, there has been no reduction in Section 232 tariffs in the same manner as the EU and Japan (The White House, 2025h–2025j).

Trade Agreement Framework with the U.S.

Thailand had to make substantial concessions to the U.S. in exchange for the reciprocal tariff of 19%.

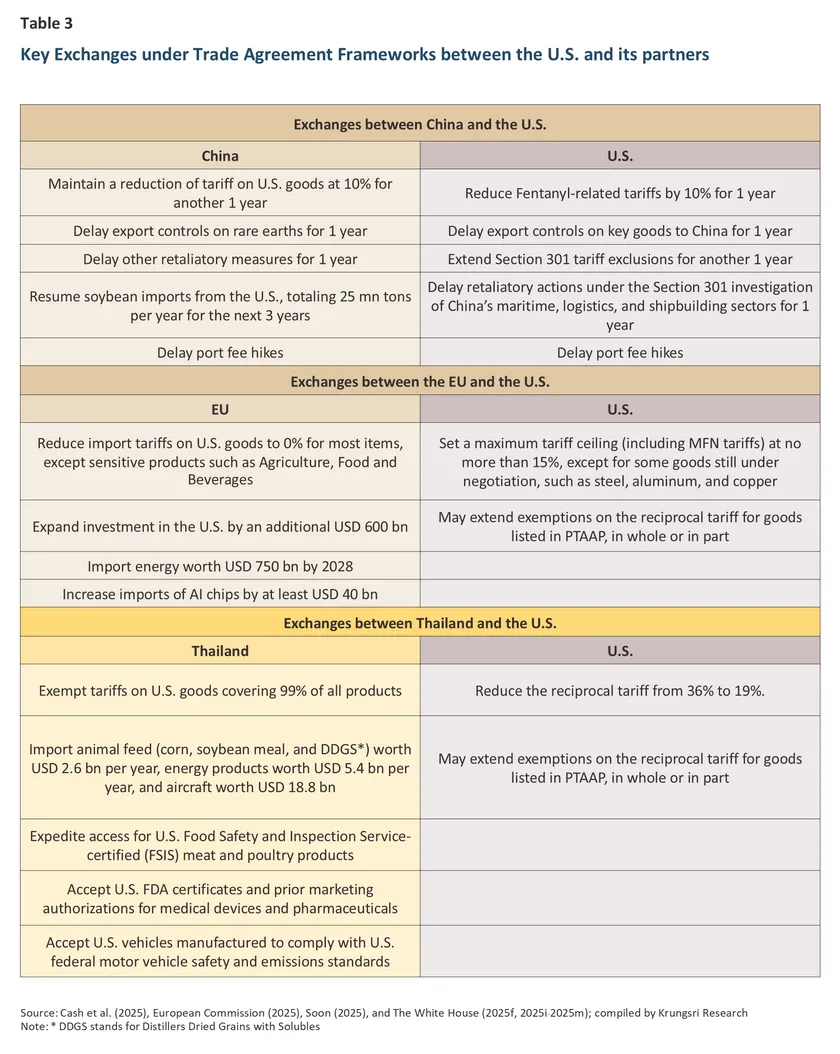

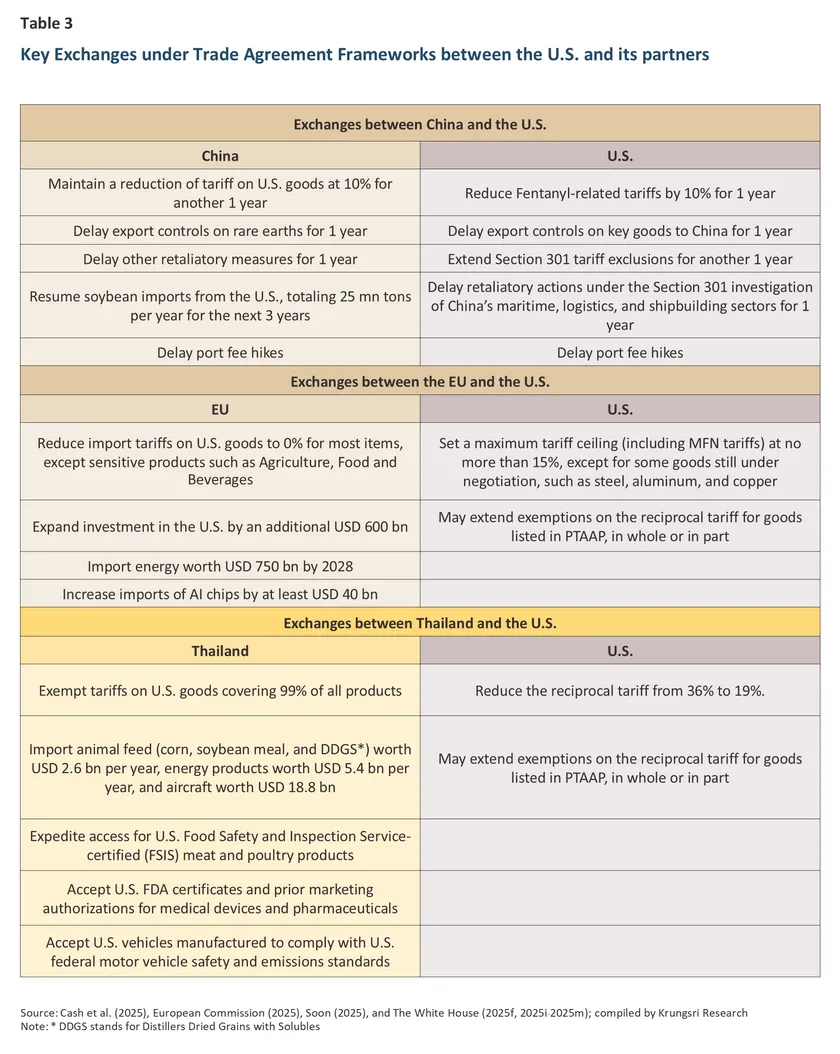

Trump’s implementation of tariff policies aligns with the analysis by Krungsri Research from early 2025 (Itthiphatwong, 2025), according to which Trump continues to use tariffs as a bargaining “threat” to secure favorable trade agreements rather than actually imposing high tariffs as previously announced, as they might “not be worth the cost” to the U.S. In particular, U.S. exports could contract at a double-digit level if such high tariffs were imposed. Given this circumstance, many countries have agreed to a framework for a trade agreement with the U.S. to reduce tariffs under several key exchanges (Table 3).

Although Thailand’s reciprocal tariff has been significantly reduced from 36% to 19% under various trade-offs, Thailand faces growing risks in several areas compared with the pre-Trump’s second-term period, including 1) direct impacts from U.S. tariffs, 2) the Twin Influx, 3) an expansion of Section 232 tariffs, and 4) potential transshipment tariffs of 40%, which will be discussed in the following sections.

Direct Impacts from U.S. tariffs

Even with the reciprocal tariff reduced to 19%, it continues to threaten Thailand’s exports, and the impact could worsen if the country fails to accelerate market diversification.

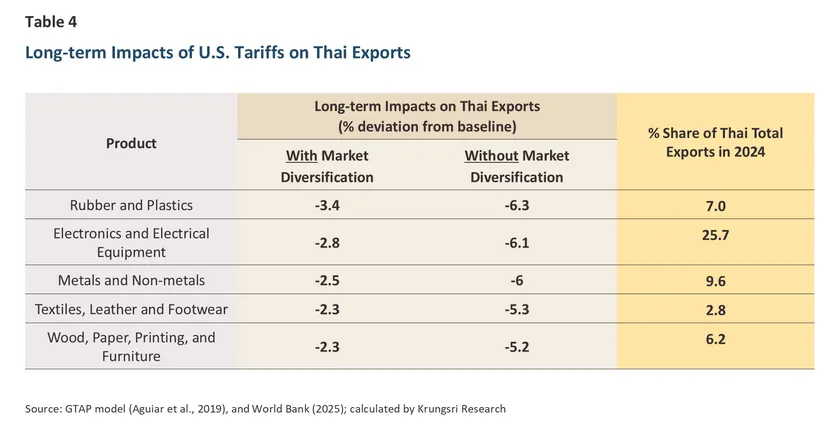

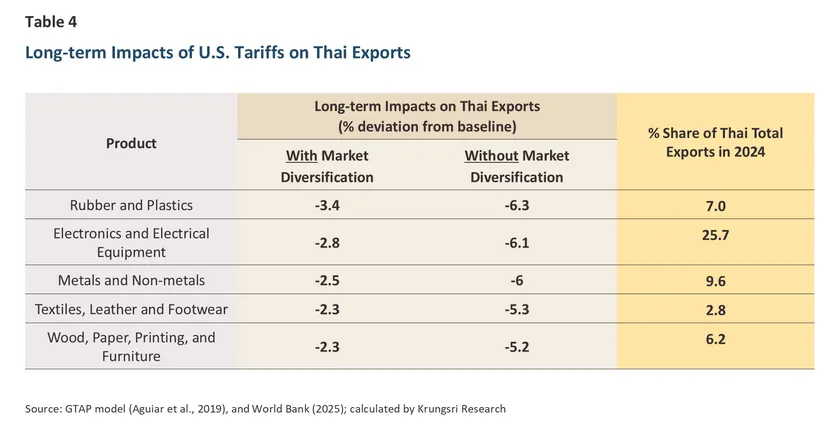

According to our estimation using the GTAP model, the reduction of the reciprocal tariff from 36% to 19% would mitigate long-term export losses by sevenfold, from THB -163.3 bn to just THB -23.2 bn. Furthermore, if Thailand reduces its reliance on the U.S. market through market diversification, export losses would be even less severe. However, even with successful market diversification, several Thai goods may still experience negative impacts from the reciprocal tariff. Specifically, exports of Electronics and Electrical Equipment could decline by -2.8% from the baseline, Metals and Non-Metals by -2.5%, and Rubber and Plastics by -3.4%. In 2024, these three groups made up a significant share of Thailand’s total exports, totaling 42.3% (Table 4)

In addition, in the worst-case scenario where Thai businesses fail to diversify into other markets, the negative impact on exports could become more severe in the long run. For example, export losses could worsen from the baseline of -2.8% to -6.1% for Electronics and Electrical Equipment, from -2.5% to -6% for Metals and Non-metals, and from -3.4% to -6.3% for Rubber and Plastics.

Twin Influx

Exempting 99% of U.S. goods from Thai import tariffs could substantially increase imports from the U.S., aggravating the existing influx of Chinese goods, and in turn resulting in a “Twin Influx.”

Although the U.S. has reduced the reciprocal tariff from 36% to 19%, the key trade-off is that Thailand has to grant tariff exemptions (i.e., a 0% tariff) on U.S. goods, which is expected to cover 99% of all products.

We expect this trade-off could cause U.S. imports to surge by as much as 30% in the long term, resulting in what we call a “Twin Influx.” This phenomenon refers to a situation in which Thailand faces a simultaneous surge of both U.S. and Chinese goods, with the latter having been flooding the Thai market since the first U.S.-China trade war.

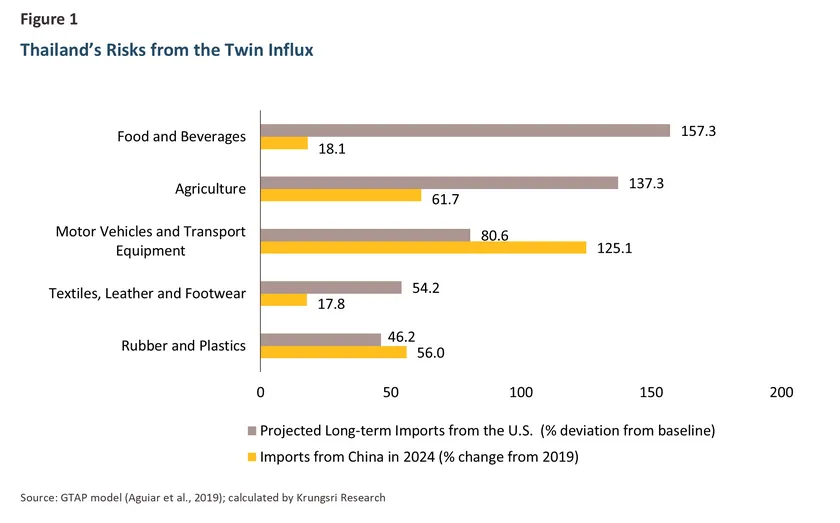

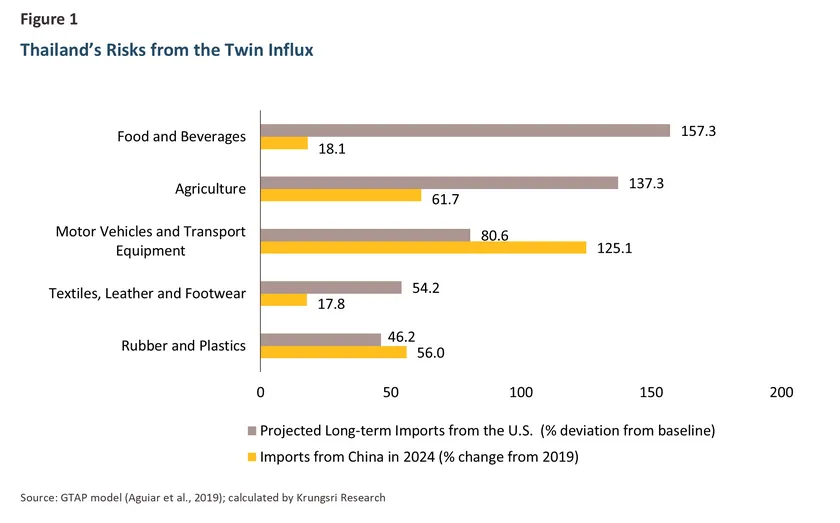

With the Twin Influx, Agriculture, as well as Motor Vehicles and Transport Equipment, are at higher risk. In the long term, imports of such goods from the U.S. could surge by up to 137.3% and 80.6% compared to the baseline, respectively. At the same time, Thailand continues to face a surge of Chinese goods in these sectors, with imports from China in 2024 increasing by 61.7% and 125.1%, respectively, compared to pre-COVID levels in 2019 (Figure 1).

The Twin Influx could be a “double-edged sword.” On the one hand, it may benefit consumers through greater product variety and lower prices due to increased competition, particularly for Chinese products, which gain advantages from economies of scale. In addition, some producers could purchase raw materials from the U.S. and China at lower costs. On the other hand, this phenomenon could intensify competition for domestic producers of the same products, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and may have knock-on effects on employment in other sectors within the supply chain.

Expansion of Section 232 Tariffs

Even Section 232 tariffs alone can significantly affect Thai exports, at a level not much lower than the combined effect of both types of U.S. tariffs.

As previously mentioned, the U.S. has begun implementing Section 232 tariffs on several goods (Table 2). A key product group currently under investigation, which could significantly impact both the global and Thai economies, is semiconductors. This also includes semiconductor manufacturing machinery and electronic devices using semiconductors (U.S. DOC, 2025c). In 2024, Thai exports of these goods to the U.S. accounted for 36.7% of Thailand's total global exports of these goods.

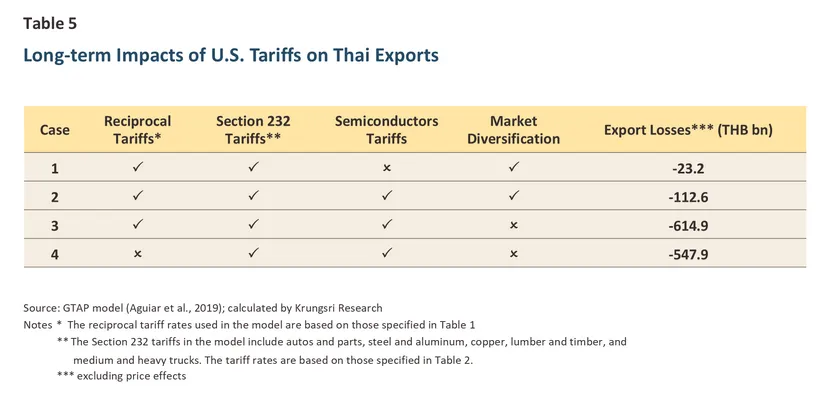

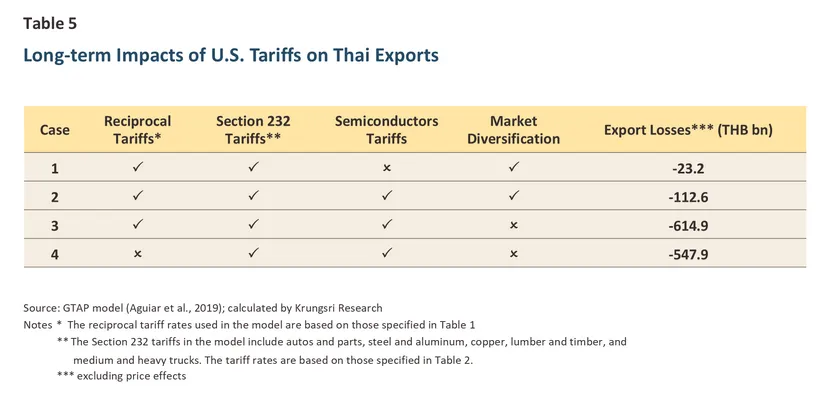

If the U.S. imposes a 100% tariff on semiconductors for all countries (with the rate capped at 15% for the EU and Japan), the long-term negative impact on Thai exports would increase fivefold (Case 2 in Table 5) compared with the current tariff scenario (which includes reciprocal tariffs and product-specific tariffs, or Case 1 in Table 5). However, if Thailand fails to sufficiently reduce its reliance on the U.S. market through export diversification, the impact could intensify by up to 27 times (Case 3 in Table 5). Furthermore, if the U.S. Supreme Court rules to invalidate the reciprocal tariffs1/, the impact on Thailand from Section 232 tariffs alone (including semiconductors) would be no less significant than in other scenarios. Specifically, in the worst-case scenario where Thailand cannot sufficiently diversify markets (Case 4 in Table 5), the impact on Thai exports would intensify 24 times compared with the current tariff scenario.

Potential Transshipment Tariffs

If Thailand is subjected to strict enforcement of transshipment tariffs, the impact on its exports could become even more severe, particularly for Electronics and Electrical Equipment, as well as Motor Vehicles and Transport Equipment.

Under Executive Order 14326 (The White House, 2025h), the U.S. has set 40% transshipment tariffs on goods deemed to circumvent tariffs, or “transshipped goods.” These tariffs serve as a tool to close loopholes in cases where China reroutes its exports to the U.S. via third countries, particularly ASEAN nations (trade rerouting). If the U.S. strictly enforces the transshipment tariff on Thailand, the impact on Thai exports could become even more severe2/.

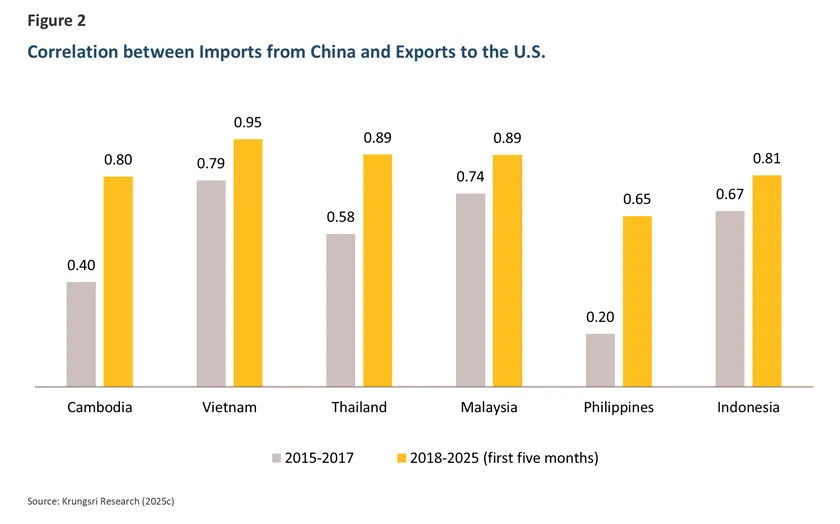

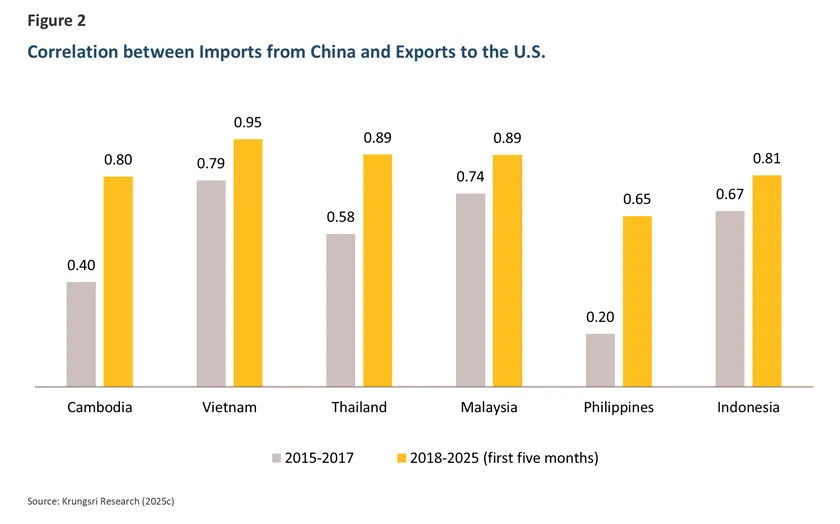

According to Krungsri Research (2025c), the correlation between imports from China and exports to the U.S. by ASEAN countries increased following the first China-U.S. trade war, which began around 2018. During that period, China’s exports to the U.S. declined as a result of U.S. tariffs, prompting China to diversify its exports to other countries, particularly ASEAN. The higher correlation observed may partly reflect China’s strategy of rerouting its exports through ASEAN to avoid direct U.S. tariffs (Figure 2).

Although Thailand and several ASEAN countries preliminarily agreed to a framework for a trade agreement with the U.S. on October 26, 2025, there are still no clear details (as of November 24, 2025) regarding the criteria for determining which goods qualify as transshipped goods. These include requirements such as the share of ASEAN inputs used in production (Regional Value Content: RVC), the proportion of Chinese inputs used in production, or the share of domestic content (Local Content).

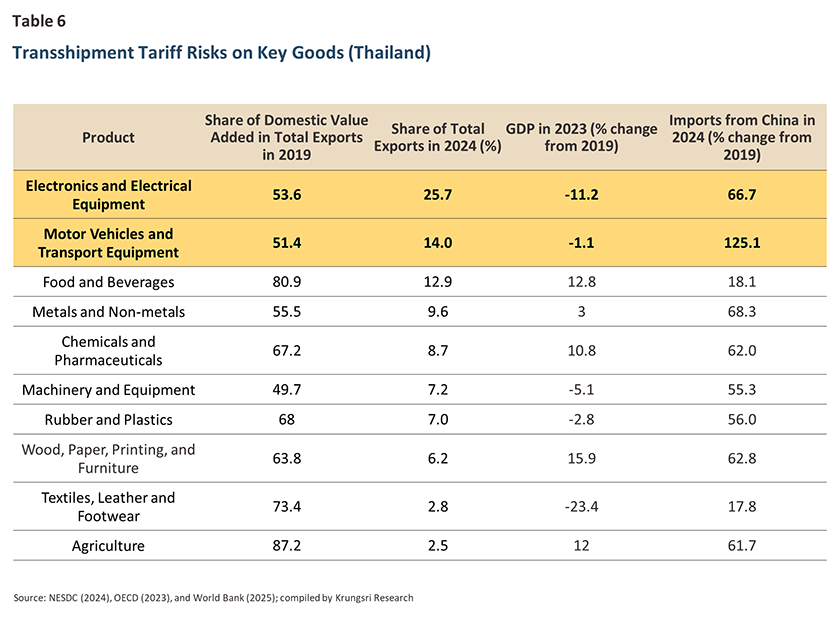

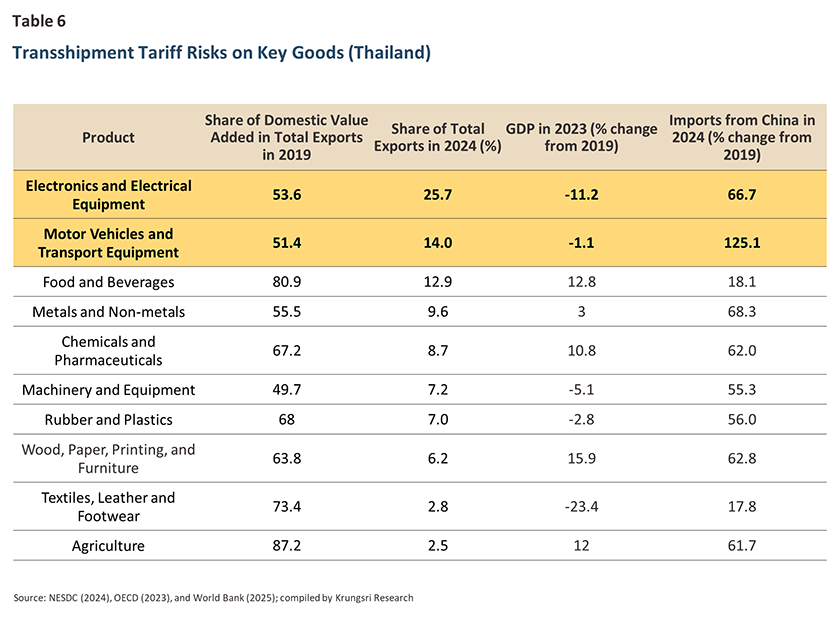

Considering only domestic content, or the share of domestic value added in total exports in 2019 (Table 6), and applying a 60% threshold, Electronics and Electrical Equipment, as well as Motor Vehicles and Transport Equipment, Thailand’s main export goods, are at high risk of negative impacts. This is consistent with imports of these goods from China in 2024, which increased by 66.7% and 125.1% compared with 2019, in contrast to the slowdown in GDP or domestic value added.

Krungsri Research View: Small Gains, Big Losses, Worth It?

The announcement of the trade agreement framework between Thailand and the U.S. on October 26, 2025, may be considered “good news” by many parties. However, a closer examination reveals several points that require careful consideration.

First, Thailand still faces the reciprocal tariff of 19%, far exceeding the previous Effective Tariff Rate (ETR) of just 0.7%. Thailand also remains subject to Section 232 tariffs of 10%-50%, unlike the EU and Japan, whose trade agreement frameworks cap tariffs for various products at 15%. In addition, the U.S. reciprocal tariff rate applied to Thailand is broadly in line with those imposed on other countries in the region. Moreover, Thailand still risks facing stricter enforcement of the transshipment tariff going forward. As a result, the 19% reciprocal tariff may not substantially mitigate the negative impacts on the competitiveness of Thai exports.

Second, the U.S. tariff exemption that covers 99% of all products could lead to a surge in Thailand’s imports from the U.S., further exacerbating the existing influx of Chinese goods and leading to the “Twin Influx”. Such a situation will intensify competition in the domestic market and may, in turn, affect labor markets in some sectors. If Thailand can secure additional exclusions for sensitive products under the trade agreement framework, it could help mitigate the negative impact, as reflected in the case of the EU. The EU reduced tariffs on U.S. goods to 0% for almost all goods but kept tariffs on sensitive products, such as Agriculture and Food and Beverages, mostly unchanged on average. In addition, the EU has imposed quotas on some U.S. products that are eligible for the 0% tariff.

Third, non-tariff commitments such as increasing imports of U.S. animal feed by USD 2.6 bn per year (41 times higher than Thailand’s animal feed imports from the U.S. in 2024 and roughly 1.3 times Thailand’s total imports), expanding imports of energy products and aircraft, accepting FDA certification for medical devices and pharmaceuticals, and accelerating access for FSIS-certified meat and poultry could limit Thailand’s flexibility in implementing its trade policies and affect producers’ ability to adjust in response to price changes. They may also create long-term obligations for future Thai governments, regardless of whether the reciprocal tariffs are eventually invalidated.

Fourth, even under an optimistic scenario where the U.S. expands the list of Thai products exempted from the reciprocal tariff to fully cover those specified in the PTAAP (adding to the current exemptions), the coverage would still account for just 15.2% of Thailand’s exports of sensitive goods to the U.S. in 2024. These goods include Agriculture, Food and Beverages, and Rubber and Plastics. Therefore, the average tariff rate imposed by the U.S. on Thailand’s sensitive goods would likely remain largely unchanged.

Overall, regardless of whether the “price Thailand has to pay” is ultimately worth it, the reality is that the Thai economy is facing growing risks from U.S. tariffs and other obligations under the trade agreement framework. These could affect businesses, employment, and the country’s competitiveness. Going forward, Thailand needs to reduce its reliance on the U.S. market, seek new trading partners, and expand cooperation with existing ones simultaneously so that Thailand can regain more autonomy in conducting proactive trade policies, instead of being forced into defensive responses to pressures from major powers. This approach is neither easy nor new, but it is necessary as long as U.S. trade policy remains highly uncertain, major economies continue to move toward economic decoupling, and Thailand still faces structural challenges and economic vulnerabilities.

In addition, Thailand should prepare measures for Thai businesses in advance in a “prudent, comprehensive, and rigorous” manner, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are particularly vulnerable. These measures could include reducing or waiving certain government fees, providing low-interest loans, and expanding subsidy programs to help businesses improve their productivity. Thailand should also subsidize firms to diversify their supply chains and avoid over-reliance on any single source of inputs, thereby reducing the risk of future trade conflicts similar to those currently affecting Chinese products. Furthermore, subsidizing and encouraging businesses to adopt new technologies will be crucial for ensuring that Thai businesses and the Thai export sector can grow in a strong and sustainable manner, ready to navigate an increasingly “volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous” (VUCA) world.

References

Aguiar, A., Chepeliev, M., Corong, E., McDougall, R., & van der Mensbrugghe, D. (2019). The GTAP data base: Version 10. Journal of Global Economic Analysis, 4(1), 1-27. https://www.jgea.org/ojs/index.php/jgea/article/view/77

Cash, J., Wang, E., Cao, E., & Thukral, N. (2025, November 6). Beijing lifts some tariffs on US farm goods but soybeans stay costly. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-confirms-suspension-24-tariff-us-goods-retains-10-levy-2025-11-05/

Dezenski, L., Muller, M., & Dlouhy, J. A. (2025, September 26). Trump plans new tariff push with 100% rate on patented drugs. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-26/trump-plans-new-tariff-push-with-100-rate-on-patented-drugs

European Commission. (2025, July 29). EU-US trade deal explained. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/united-states-america/eu-us-trade-deal-explained_en

Gottlieb, I. (2025, November 5). Here are Trump’s options if the Supreme Court says his tariffs are illegal. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-11-04/supreme-court-tariffs-case-trump-s-options-if-levies-upheld-as-illegal

Itthiphatwong, S. (2025, January 20). Impact of trade war 2.0 on the Thai economy. Krungsri Research. https://www.krungsri.com/th/research/research-intelligence/trade-war-2025

Krungsri Research. (2025a, September 1). Legal disputes over reciprocal tariffs. https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/macroeconomic/research-flash/20250902

Krungsri Research. (2025b, September 17). Monthly economic bulletin (September 2025). https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/macroeconomic/monthly-bulletin/bulletin-202509

Krungsri Research. (2025c, August 1). Regional economic outlook 2025 update. https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/regional-economic/regional-outlook/2025-update

Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council [NESDC]. (2024). National income of Thailand 2023 chain volume measures [Data file]. https://www.nesdc.go.th/en/?p=36308&ddl=36309

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2023). Trade in Value Added (TiVA) indicators, 2023 edition [Database]. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/trade-in-value-added.html

Rodriguez, A. (2025, November 18). U.S. trade strategy evolves as IEEPA tariffs face legal scrutiny. Plante Moran. https://www.plantemoran.com/explore-our-thinking/insight/2025/11/us-trade-strategy-evolves-as-ieepa-tariffs-face-legal-scrutiny

Soon, W. (2025, October 30). US, China to suspend reciprocal port fees by one year. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-30/us-delays-china-port-fee-talks-as-focus-turns-to-shipbuilding

U.S. Department of Commerce [U.S. DoC]. (2025a, May 13). Notice of request for public comments on section 232 national security investigation of imports of commercial aircraft and jet engines and parts for commercial aircraft and jet engines. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/05/13/2025-08500/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of

U.S. Department of Commerce [U.S. DoC]. (2025b, April 25). Notice of request for public comments on section 232 national security investigation of imports of processed critical minerals and derivative products. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/25/2025-07273/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of

U.S. Department of Commerce [U.S. DoC]. (2025c, April 16). Notice of request for public comments on section 232 national security investigation of imports of semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/16/2025-06591/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of

Aguiar, A., Chepeliev, M., Corong, E., McDougall, R., & van der Mensbrugghe, D. (2019). The GTAP data base: Version 10. Journal of Global Economic Analysis, 4(1), 1-27. https://www.jgea.org/ojs/index.php/jgea/article/view/77

Cash, J., Wang, E., Cao, E., & Thukral, N. (2025, November 6). Beijing lifts some tariffs on US farm goods but soybeans stay costly. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-confirms-suspension-24-tariff-us-goods-retains-10-levy-2025-11-05/

Dezenski, L., Muller, M., & Dlouhy, J. A. (2025, September 26). Trump plans new tariff push with 100% rate on patented drugs. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-26/trump-plans-new-tariff-push-with-100-rate-on-patented-drugs

European Commission. (2025, July 29). EU-US trade deal explained. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/united-states-america/eu-us-trade-deal-explained_en

Gottlieb, I. (2025, November 5). Here are Trump’s options if the Supreme Court says his tariffs are illegal. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-11-04/supreme-court-tariffs-case-trump-s-options-if-levies-upheld-as-illegal

Itthiphatwong, S. (2025, January 20). Impact of trade war 2.0 on the Thai economy. Krungsri Research. https://www.krungsri.com/th/research/research-intelligence/trade-war-2025

Krungsri Research. (2025a, September 1). Legal disputes over reciprocal tariffs. https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/macroeconomic/research-flash/20250902

Krungsri Research. (2025b, September 17). Monthly economic bulletin (September 2025). https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/macroeconomic/monthly-bulletin/bulletin-202509

Krungsri Research. (2025c, August 1). Regional economic outlook 2025 update. https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/regional-economic/regional-outlook/2025-update

Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council [NESDC]. (2024). National income of Thailand 2023 chain volume measures [Data file]. https://www.nesdc.go.th/en/?p=36308&ddl=36309

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2023). Trade in Value Added (TiVA) indicators, 2023 edition [Database]. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/trade-in-value-added.html

Rodriguez, A. (2025, November 18). U.S. trade strategy evolves as IEEPA tariffs face legal scrutiny. Plante Moran. https://www.plantemoran.com/explore-our-thinking/insight/2025/11/us-trade-strategy-evolves-as-ieepa-tariffs-face-legal-scrutiny

Soon, W. (2025, October 30). US, China to suspend reciprocal port fees by one year. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-30/us-delays-china-port-fee-talks-as-focus-turns-to-shipbuilding

U.S. Department of Commerce [U.S. DoC]. (2025a, May 13). Notice of request for public comments on section 232 national security investigation of imports of commercial aircraft and jet engines and parts for commercial aircraft and jet engines. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/05/13/2025-08500/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of

U.S. Department of Commerce [U.S. DoC]. (2025b, April 25). Notice of request for public comments on section 232 national security investigation of imports of processed critical minerals and derivative products. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/25/2025-07273/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of

U.S. Department of Commerce [U.S. DoC]. (2025c, April 16). Notice of request for public comments on section 232 national security investigation of imports of semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/16/2025-06591/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of

The White House. (2025a, June 3). Adjusting imports of aluminum and steel into the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/06/adjusting-imports-of-aluminum-and-steel-into-the-united-states/

The White House. (2025b, March 26). Adjusting imports of automobiles and automobile parts into the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/adjusting-imports-of-automobiles-and-autombile-parts-into-the-united-states/

The White House. (2025c, July 30). Adjusting imports of copper into the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/07/adjusting-imports-of-copper-into-the-united-states/

The White House. (2025d, October 17). Adjusting imports of medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, medium- and heavy-duty vehicle parts, and buses into the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/10/adjusting-imports-of-medium-and-heavy-duty-vehicles-medium-and-heavy-duty-vehicle-parts-and-buses-into-the-united-states/

The White House. (2025e, September 29). Adjusting imports of timber, lumber, and their derivative products into the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/09/adjusting-imports-of-timber-lumber-and-their-derivative-products-into-the-united-states/

The White House. (2025f, November 1). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump strikes deal on economic and trade relations with China. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/11/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-strikes-deal-on-economic-and-trade-relations-with-china/

The White House. (2025g, July 31). Further modifying the reciprocal tariff rates. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/07/further-modifying-the-reciprocal-tariff-rates/

The White House. (2025h, September 4). Implementing the United States–Japan agreement. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/09/implementing-the-united-states-japan-agreement/

The White House. (2025i, October 26). Joint statement on a framework for a United States-Thailand agreement on reciprocal trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/10/joint-statement-on-a-framework-for-a-united-states-thailand-agreement-on-reciprocal-trade/

The White House. (2025j, August 21). Joint statement on a United States-European Union framework on an agreement on reciprocal, fair, and balanced trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/08/joint-statement-on-a-united-states-european-union-framework-on-an-agreement-on-reciprocal-fair-and-balanced-trade/

The White House. (2025k, November 4). Modifying duties addressing the synthetic opioid supply chain in the People's Republic of China. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/11/modifying-duties-addressing-the-synthetic-opioid-supply-chain-in-the-peoples-republic-of-china/

The White House. (2025l, November 4). Modifying reciprocal tariff rates consistent with the economic and trade arrangement between the United States and the People's Republic of China. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/11/modifying-reciprocal-tariff-rates-consistent-with-the-economic-and-trade-arrangement-between-the-united-states-and-the-peoples-republic-of-china/

The White House. (2025m, September 5). Modifying the scope of reciprocal tariffs and establishing procedures for implementing trade and security agreements. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/09/modifying-the-scope-of-reciprocal-tariffs-and-establishing-procedures-for-implementing-trade-and-security-agreements/

The White House. (2025n, April 2). Regulating imports with a reciprocal tariff to rectify trade practices that contribute to large and persistent annual United States goods trade deficits. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/regulating-imports-with-a-reciprocal-tariff-to-rectify-trade-practices-that-contribute-to-large-and-persistent-annual-united-states-goods-trade-deficits/

World Bank. (2025). World integrated trade solution [Database]. https://wits.worldbank.org/

1/ As of November 24, 2025, the dispute over the legality of the reciprocal tariffs is currently under consideration by the U.S. Supreme Court, with a ruling expected between late 2025 and early 2026.

2/ Compared with the scenario where only reciprocal tariffs and Section 232 tariffs are imposed, which represents the current situation (As-is).