Introduction

Amid the intensifying technological rivalry between the United States and China, semiconductors have emerged as products that shape both global economic power and security. These tiny components are far more than small parts inside smartphones or electric vehicles; they serve as the “brains” controlling nearly every modern innovation, from Artificial Intelligence (AI) and satellites to advanced military systems. As a result, countries capable of producing and controlling the semiconductor and high-end chip supply chain gain a clear strategic advantage over others.

This semiconductor momentum is not limited to the two major powers. Investment flows are increasingly shifting toward Southeast Asia. For Thailand, this trend may present a crucial opportunity to upgrade its manufacturing sector toward higher-value electronics and to cultivate new technological capabilities that can drive future economic growth.

What Are Semiconductors?

A semiconductor material is a substance with partial electrical conductivity—meaning its conductivity lies between that of a conductor and an insulator. Semiconductor properties can be enhanced or tuned through a process known as “doping,” in which impurities are intentionally added. Commonly used semiconductor materials include silicon, germanium, gallium arsenide, silicon carbide, and gallium nitride

1/. Each possesses distinct properties that make it suitable for different applications.

Because of these characteristics, semiconductor materials serve as essential inputs for

semiconductor devices, i.e., electronic components capable of “switching” electrical current on and off or responding to changes in light, heat, or voltage. These devices form the building blocks of countless electronic systems, including smartphones, computers, home appliances, communication networks, automotive technologies, energy systems, medical equipment, automation systems, data centers, and rapidly expanding AI applications. According to

the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics (WSTS), the global semiconductor market is projected to reach USD 728 billion in 2025, an increase of 15.4% from USD 631 billion in 2024, with continued long-term growth expected

2/.

From Semiconductor Materials to “Chips”

The transformation of semiconductor materials into usable components begins with slicing semiconductor crystal ingots into thin circular disks known as wafers. These wafers then undergo multiple processing steps, such as material deposition and surface etching, to create intricate electrical circuits on their surface, ultimately forming integrated circuits (ICs).

Once fabrication is complete, the wafer is cut into small pieces called dies or chips. These units then proceed through packaging, assembly, and quality testing before they are ready for use in electronic devices.

Types of Semiconductor Devices and Their Applications

Semiconductor devices come in several forms, each designed to perform specific functions such as data processing, data storage, or electrical signal conversion. Broadly, semiconductors can be classified into three groups: Logic, Memory, and Others (Discrete, Analog, and Other: DAO)

3/. These devices are used across a wide range of industries—from household appliances, computers, and communication systems to smart energy management, medical technologies, transportation, manufacturing, and automation systems (Table 1).

The Global Semiconductor Supply Chain

The semiconductor industry is one of the world’s most complex and globally interconnected sectors. Producing a single chip requires highly specialized expertise—from design to final assembly—with each stage handled by dedicated manufacturers and service providers dispersed across multiple countries.

Accenture and the Global Semiconductor Alliance (GSA) estimate that each step of the supply chain involves, on average, direct suppliers from 25 countries, with another 23 countries contributing to supporting processes. As a result, a chip may cross international borders more than 70 times before reaching end consumers

4/.

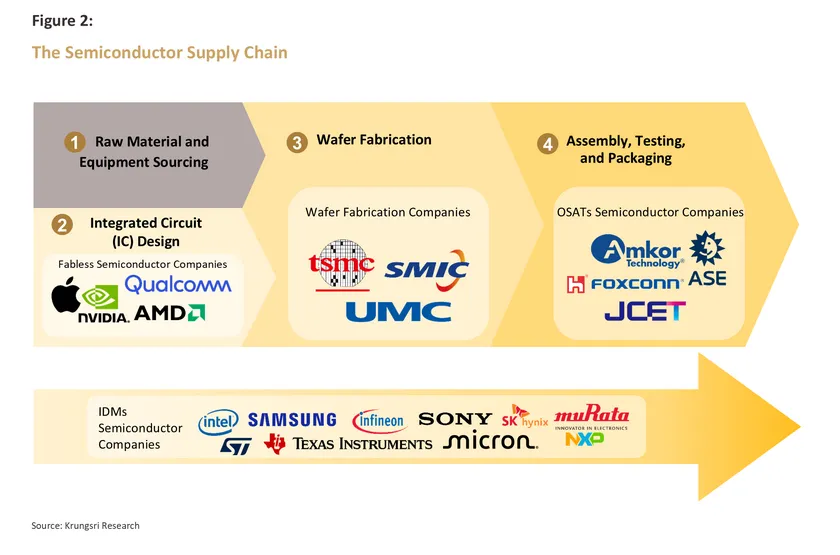

The global semiconductor supply chain can be divided into four main stages:

- Materials & Equipment: Key raw materials used in semiconductor manufacturing include silicon, gallium, and germanium, sourced primarily from companies in China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. Specialized semiconductor devices—such as photonic components, lasers, and magnetic devices—also require rare earth elements such as scandium and yttrium. China remains the dominant producer of rare earths, accounting for about 70% of global output in 20245/. Meanwhile, most semiconductor manufacturing equipment comes from countries with advanced chip-fabrication technologies—mainly the United States, the European Union, and Japan—giving these economies strong bargaining power in global trade.

- Integrated Circuit (IC) Design: At this stage, engineers use Electronic Design Automation (EDA) software to create chip models and blueprints. IC design activities are concentrated in the United States, Taiwan, and China. Companies in this segment fall into two groups: (1) Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs), which design, fabricate, and assemble chips in-house. Major players include Intel (U.S.) and Samsung Electronics (South Korea); and (2) Fabless companies, which focus solely on chip design and outsource production. Leading global fabless firms include Apple, NVIDIA, Qualcomm, and AMD (all U.S.).

- Wafer Fabrication: This stage transforms semiconductor wafers into functional integrated circuits. Fabrication is heavily concentrated in East Asia—particularly Taiwan, China, Japan, and South Korea. Major players include TSMC (Taiwan), SMIC (China), and UMC (Taiwan).

- Assembly, Testing, and Packaging (ATP): In this final stage, wafers are diced into individual dies, packaged to prevent damage, and tested for functionality, performance, and reliability before being delivered for use in consumer and industrial products. ATP operations are primarily located in Taiwan, China, and Southeast Asia—including Thailand. Key companies include both IDMs and specialized Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) providers, such as Foxconn (Taiwan), ASE (Taiwan), Amkor (U.S.), and JCET (China).

Where Does Thailand Sit in the Semiconductor Supply Chain?

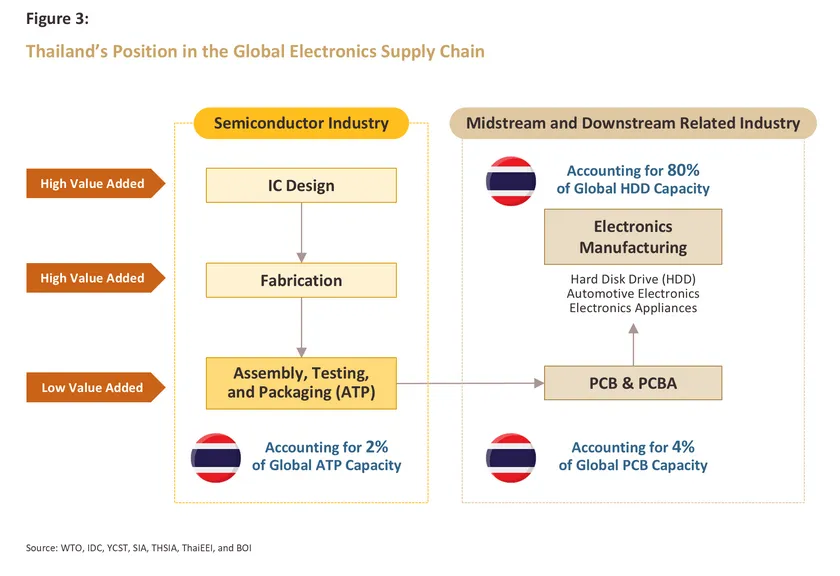

Thailand’s primary role in the global semiconductor supply chain lies at the downstream end, particularly in the Assembly, Test, and Packaging (ATP) stage. In 2022, Thailand accounted for around 2% of global ATP capacity6/ (Figure 3). However, this stage generates relatively low value added—only about 6% of the total value created along the semiconductor value chain. Most value is concentrated upstream, namely in chip design (59%) and wafer fabrication (19%), where Thailand lacks both the critical mineral resources and the advanced equipment technologies needed for commercial-scale development. In the ATP stage, Thailand mainly receives processed wafers from overseas for assembly and testing before exporting the finished components back to global markets. As a result, the value created domestically comes largely from labor, service fees, and operational costs rather than from high technology or intellectual property.

Compared with Malaysia—Thailand’s regional competitor and ASEAN’s most advanced ATP hub with 7% of global capacity—Thailand still trails in process sophistication, technological capability, and workforce expertise. By 2032, Thailand’s share of global ATP capacity is projected to decline further to just 1%7/ . In contrast, Malaysia is expected to expand its share to 9%, supported by strong government incentives and increased investment from leading global firms. Vietnam is also emerging rapidly; its ATP share is expected to surge from less than 1% today to around 8%, driven by major multinational investments and the country’s advantages in labor cost, skill availability, and workforce size.

Despite these challenges, Thailand continues to have meaningful opportunities in the semiconductor value chain, supported by its strong midstream and downstream industries. Key midstream strengths include printed circuit board (PCB) manufacturing and hard disk drive (HDD) production—both essential components for downstream sectors such as data centers and a wide range of electronic devices used in appliances and electric vehicles. Thailand produced roughly 4% of the world’s PCBs in 2023, ranking first in ASEAN, and this share is expected to rise to around 10% within the next 3–5 years8/. In HDDs, Thailand is the global leader, accounting for approximately 80% of worldwide production (as of 2024)9/.

Most semiconductor companies operating in Thailand are facilities specializing in Assembly, Test, and Packaging (ATP). These include both Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs) and Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) providers. The majority are multinational firms that rely on imported materials and key components from their overseas parent companies. Thailand also hosts production facilities for the DAO segment (Discrete, Analog, and Others), including transistors, diodes, power semiconductors, sensors, and light-emitting diodes. These products primarily serve the automotive, medical, and broader electronics industries, led by firms such as Infineon, NXP, Analog Devices, Sony, HANA Microelectronics, and Stars Microelectronics.

In addition, Thailand has a sizable Printed Circuit Board (PCB) manufacturing base. In 2023, the country had 163 PCB manufacturers10/ , more than half of which were large enterprises (51%). Most are multinational firms from China, Taiwan, and Japan, including Delta Electronics, Mektec, Fujikura, Chin Poon Electronics, and Cal-Comp Electronics. These firms are predominantly positioned in the mid- and downstream stages of the PCB value chain, focusing on manufacturing and assembly. Thailand is also home to two global leaders in Hard Disk Drive (HDD) manufacturing—Western Digital and Seagate Technology—both U.S.-based multinationals with major production facilities across the country. Thailand serves as a strategic manufacturing base for both companies.

Thailand’s trade structure in semiconductors and electronics reflects a production model heavily dependent on imported components for assembly and re-export. The country imports high-value materials and components from technologically advanced economies, assembles or tests the products, integrates them into electronic systems, and exports them to global markets.

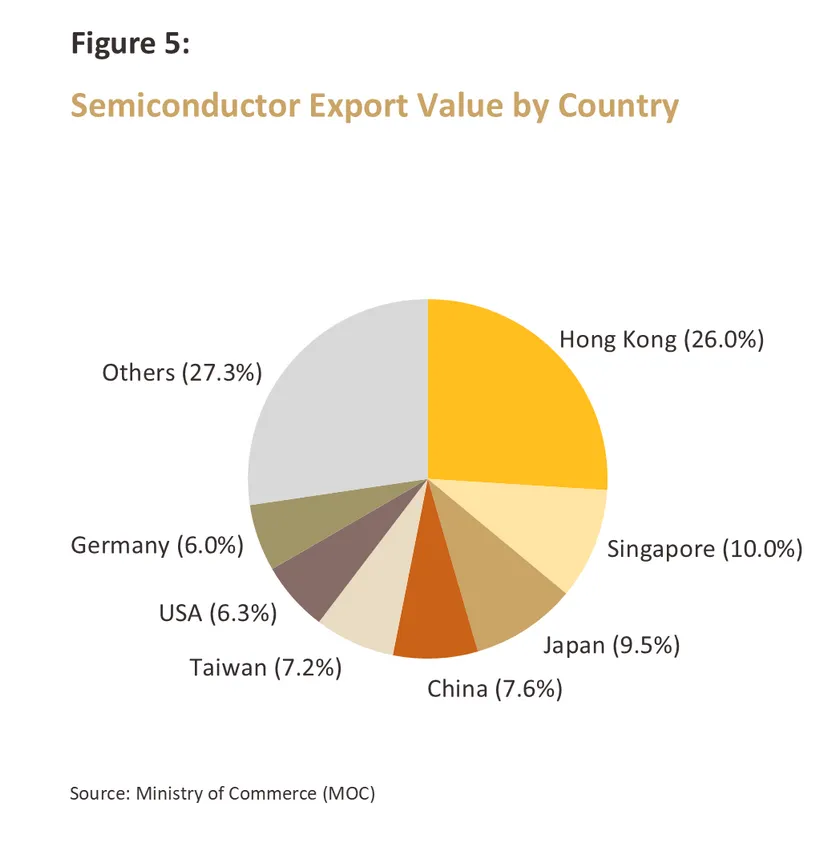

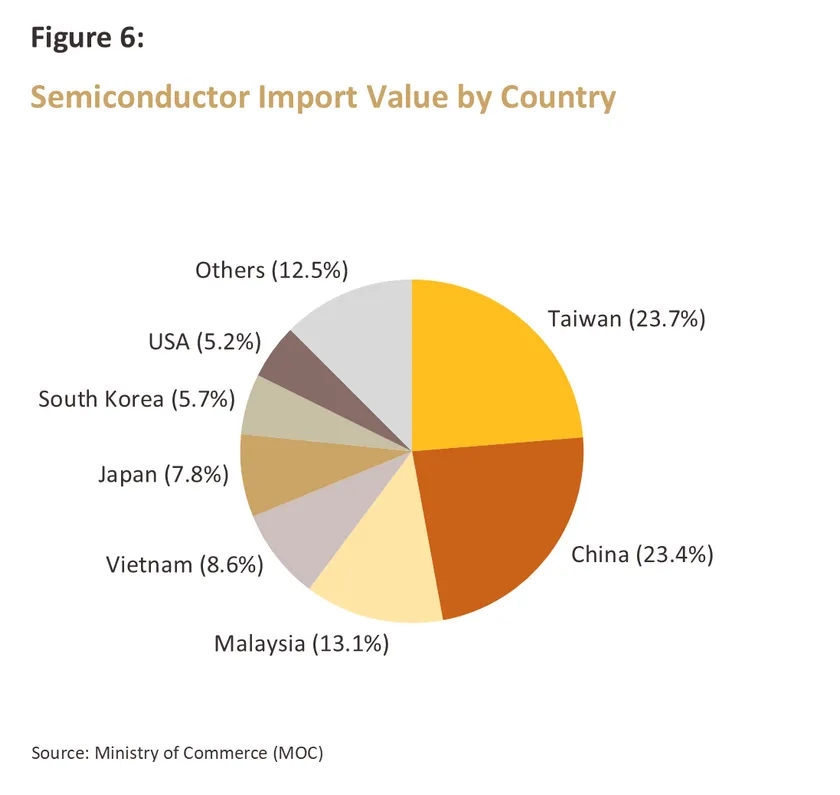

In 2024, Thailand imported semiconductors worth USD 7.81 billion—around 2.6% of total imports. Key import sources included Taiwan (23.7% of semiconductor imports), China (23.4%), Malaysia (13.1%), Vietnam (8.6%), and Japan (7.8%). Taiwan, China, and Japan are among the world’s largest semiconductor producers, together accounting for more than 63% of global semiconductor ATP capacity in 2022, underscoring their central role in the supply chain. Malaysia is a major hub for high-complexity semiconductor assembly, while Vietnam is emerging rapidly due to substantial investment from leading semiconductor firms.

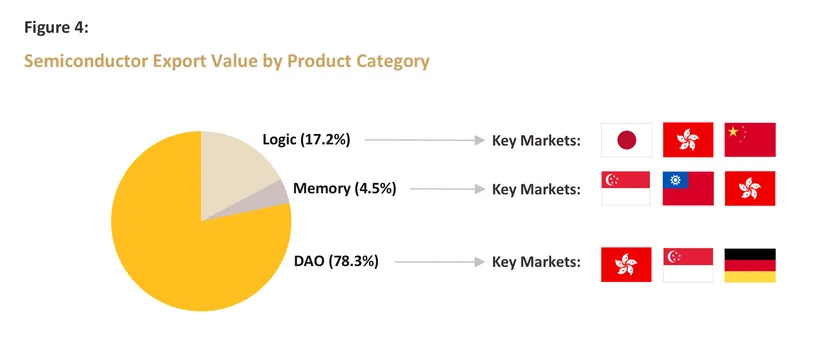

On the export side, Thailand exported semiconductors worth USD 8.57 billion in 2024, accounting for 2.9% of total exports. However, semiconductor exports contracted by –12.7% that year. Key export destinations included Hong Kong (26.0% of semiconductor export value), Singapore (10.0%), Japan (9.5%), China (7.6%), and Taiwan (7.2%). Export value by product category was as follows:

-

Logic: USD 1.48 billion (17.2% of semiconductor exports), with Japan, Hong Kong, and China as major destinations.

-

Memory: USD 0.38 billion (4.5%), primarily exported to Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

-

DAO: USD 6.71 billion (78.3%), with Hong Kong, Singapore, and Germany as key markets.

Exports of two other semiconductor-related products—PCBs and HDDs—were also significant. In 2024, PCB exports reached USD 1.33 billion, growing 0.8%, with China, Japan, and the United States as major markets. HDD exports totaled USD 6.35 billion, increasing 41.9%, and were shipped to markets worldwide

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of Thailand’s Semiconductor Industry

With long-standing expertise in downstream assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP), Thailand has the potential to move up the global value chain toward higher-value semiconductor design and upstream manufacturing. Krungsri Research evaluates Thailand’s strategic position and competitiveness through a SWOT analysis, as follows:

Strengths

-

Robust mid- to downstream ecosystem: Thailand benefits from decades of foreign and domestic investment in ATP facilities, alongside strong capabilities in Discrete, Analog, and Other Devices (DAO). The country also has a solid midstream industry—especially printed circuit boards (PCBs), a core component used together with semiconductors in electronic assemblies. At the same time, Thailand hosts diverse downstream industries—including HDD, home appliances, telecommunications, data centers, and modern automotive manufacturing—which generates stable domestic demand for semiconductor-related products. These advantages continue to attract new investments, particularly in higher-value upstream activities.

-

Supportive investment incentives: The Board of Investment (BOI) has strengthened its incentive schemes across the electronics value chain, including corporate income tax exemptions and ecosystem-building support. Between 2022 and June 2025, BOI approved THB 650 billion in investment for electrical and electronics industries, representing 24.6% of total approved investment. Related sectors such as digital industries (THB 460 billion; 17.6%) and automotive and parts (THB 210 billion; 8.0%) also received substantial support. Importantly, BOI recently enhanced incentives for upstream activities by extending tax holidays to 8 years for IC design and 10 years11/ for wafer fabrication—longer than the 3–8 years offered to mid- and downstream electronics manufacturing.

-

Strategic geographic location: Thailand’s position between East and South Asia—supported by deep-sea ports, international airports, and the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC)—provides efficient logistical connectivity and underpins long-term industrial expansion. The EEC spans three provinces: Chonburi, Rayong, and Chachoengsao.

Weaknesses

-

High reliance on imported raw materials and equipment: Thailand depends heavily on imports of key semiconductor inputs such as wafers and specialty chemicals from East Asia and the United States. The country also relies on importing advanced machinery and production technology, contributing to high production costs and limiting competitiveness.

-

Limited upstream presence: Thailand lacks strong capabilities in high-value upstream segments such as integrated circuit design and wafer fabrication. Most domestic production remains concentrated in the downstream ATP segment, resulting in a dominance of lower-value products such as transistors and diodes. Higher-value categories such as Logic ICs and Memory ICs represent only a small share, contributing to Thailand’s modest 1.0% share of global semiconductor exports in 202412/.

-

Shortage of high-skilled talent: Although Thailand has an experienced workforce in ATP, it faces shortages of specialized personnel required for upstream design and wafer fabrication—such as semiconductor researchers skilled in electronics, big-data analytics, AI, and materials science, as well as manufacturing engineers with expertise in industrial electrical systems, programming, and IoT13/. As a result, technology transfer from foreign investors remains limited.

Opportunities

-

Supply chain diversification amid geopolitical tensions: U.S.–China trade and technology tensions are driving firms to diversify production into ASEAN. Thailand’s geopolitical neutrality and ongoing investment incentives position the country as an attractive hub for advanced electronics and related supply chains14/. From 2023–2025, investment applications in advanced electronics projects grew at a robust CAGR of 39.6%15/.

-

Rising global semiconductor demand: PwC projects global semiconductor demand to rise at a CAGR of 7.7% during 2024–203016/. By 2030, the top three demand segments will be: (1) Computing (41%) – especially Logic and Memory chips17/; (2) Communications (31%) – especially Analog devices18/; and (3) Automotive (13%) – especially OSD and Logic components19/. These trends present opportunities for Thailand to expand participation in both upstream and downstream segments.

Threats

- Risks from China’s export controls on critical minerals: China dominates global production of key semiconductor minerals such as gallium (98%) and germanium (68%)20/, as well as antimony and rare-earth elements like dysprosium—essential for wafers, high-power chips, high-frequency chips, and sensor semiconductors. Export restrictions could disrupt global production and undermine Thailand’s competitiveness, given its heavy reliance on imported inputs.

- Risk of U.S. classification as “Chinese-origin” goods leading to higher US tariffs: Thailand’s electronics industry remains focused on mid- to downstream production and highly dependent on imported components, with local content accounting for only 22.5% in 202421/. This creates vulnerability to tightened rules of origin, especially for new or frequently updated products with low domestic value content. If classified as indirectly Chinese-origin, Thai exports could face higher U.S. tariffs.

Krungsri Research View: The Role of the Public and Private Sectors in Advancing Thailand’s Semiconductor Industry

To elevate Thailand’s semiconductor industry toward higher-value activities such as chip design and upstream manufacturing, the government and relevant agencies can deploy targeted industrial policies that leverage the country’s strengths and opportunities while addressing structural weaknesses and mitigating emerging risks. Key strategic directions include:

-

Technology Development: Thailand should promote upstream semiconductor activities with higher value added in which Thailand currently has limited market share, such as Logic and Memory chips. These efforts would help expand Thailand’s share of global semiconductor exports. At the same time, policy support should encourage investment in advanced manufacturing technologies and process innovation for ATP (Assembly, Test, and Packaging) firms, which face intensifying global competition. Enhancing manufacturing efficiency will help reduce costs and strengthen Thailand’s competitive position.

-

Human Capital: Thailand needs to build a pipeline of high-skill talent in IC research and design, as well as wafer fabrication. In the short term, the government can support reskilling and upskilling programs for relevant occupations and incentivize the hiring of foreign experts. In the longer term, Thailand should expand funding and specialized semiconductor curricula while strengthening collaboration between universities and semiconductor manufacturers to ensure workforce development and research that align with industry needs.

-

Market Development: Public policy should also stimulate domestic market expansion to support business matching between local semiconductor producers and mid- to downstream industries—particularly electrical appliances, digital industries, and automotive manufacturers, which have seen rising investment over the past 2–3 years.

Meanwhile, the private sector should adjust business strategies to seize emerging opportunities and mitigate new challenges: (1) Invest in technology to develop higher-performance products that meet the needs of rapidly advancing downstream industries—especially computing, communications, and next-generation automotive. Firms should also upgrade production processes to reduce costs and maintain competitiveness; (2) Diversify raw-material sources by developing supply relationships with non-Chinese suppliers to hedge against China’s export controls on critical minerals and to minimize the risk of U.S. tariff hikes on products classified as “China-routed.”; (3) Build strategic collaborations, particularly with domestic downstream manufacturers, to strengthen technological capabilities, expand market share, and capture opportunities created by growing foreign investment in Thailand’s downstream electronics sectors.

Although Thailand’s semiconductor industry currently faces multiple structural constraints, the country continues to benefit from strong mid- and downstream production bases and rising foreign investment driven by global supply-chain diversification. These conditions provide Thailand with a meaningful window to advance further upstream to meet rising global demand—particularly from fast-growing sectors such as data centers and AI-driven smart devices. To fully realize this potential, public and private stakeholders must work together to remove existing bottlenecks and articulate a clear national semiconductor master plan. Doing so would enable Thailand to develop a globally competitive semiconductor industry, strengthen its bargaining power, and secure its position in an increasingly technology-intensive global economy.

References

กรุงเทพธุรกิจ. (2025). “ภาษี 19%สหรัฐ ซัด 'อิเล็กทรอนิกส์ไทย'! ดีมานด์หด ผู้ผลิตเร่งปรับตัวรับมือ ‘เกมใหม่’”. กรุงเทพธุรกิจ. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/tech/gadget/1192643

ฐานเศรษฐกิจ. (2024). “เปิดบิ๊กเนมผู้ผลิตเซมิคอนดักเตอร์โลก และศักยภาพของไทย”. Thansettakij. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.thansettakij.com/world/591146

ประชาชาติธุรกิจ. (2025). “ห่วง 7 กลุ่มสินค้า RVC ต่ำ ภาษี 40% เร่งต่อรองสหรัฐ”. ประชาชาติธุรกิจ. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.prachachat.net/economy/news-1862080

วรรณเลิศลักษณ์, ว. (2017). “สารกึ่งตัวนำ”. SciMath. Retrieved Nov 15, 2025, from https://www.scimath.org/lesson-physics/item/7237-2017-06-11-14-15-33

สถาบันไฟฟ้าและอิเล็กทรอนิกส์. (2567). “การศึกษาเชิงลึกของอุตสาหกรรมวงจรพิมพ์และอุตสาหกรรมเกี่ยวเนื่อง”. ThaiEEI. Retrieved Nov 20, 2025, from เล่มการวิเคราะห์เชิงลึกฉบับสมบูรณ์ 09.05.2024_2024-10-01_145222555.pdf

สำนักงานคณะกรรมการส่งเสริมการลงทุน. (2021). “การปรับปรุงการส่งเสริมการลงทุนอุตสาหกรรมเซมิคอนดักเตอร์”. BOI. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.faq108.co.th/boi/announcement/pdf/2564_sor06.pdf

สำนักงานคณะกรรมการส่งเสริมการลงทุน. (2567). “อุตสาหกรรม PCB ผู้เปลี่ยนเกม ขับเคลื่อนไทยสู่ผู้นำเทคโนโลยีในภูมิภาค”. BOI. Retrieved Nov 20, 2025, from PCB.pdf

อัตถิ, น. (2025). “‘อุตสาหกรรมเซมิคอนดักเตอร์ไทยแข็งแกร่งตั้งแต่ต้นน้ำถึงปลายน้ำ’ วลีที่เป็นได้มากกว่าภาพฝัน”. NSTDA. Retrieved Nov 5, 2025, from https://www.nstda.or.th/sci2pub/semiconductor-ecosystem/

Alam, S., et al. (2020). “Globality and Complexity of the Semiconductor Ecosystem”. GSA. Retrieved Nov 6, 2025, from https://www.gsaglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/GSA-Accenture-Globality-and-Complexity-of-the-Semiconductor-Ecosystem.pdf

Baskaran, G. and Schwartz, M. (2024). “From Mine to Microchip: Addressing Critical Mineral Supply Chain Risks in Semiconductor Production”. Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS). Retrieved Nov 18, 2025, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/mine-microchip

Boston Consulting Group & Semiconductor Industry Association. (2024). “Emerging Resilience in The Semiconductor Supply Chain”. BCG & SIA. Retrieved Nov 20, 2025, from Report_Emerging-Resilience-in-the-Semiconductor-Supply-Chain.pdf

Dunde, A., Finselberg, B., and Rolfes, P. (2022). “Resilience of the Semiconductor Supply Chain”. Semi. Retrieved Nov 18, 2025, from https://www.semi.org/sites/semi.org/files/2022-12/glo-csi-dhl-resilience-of-the-semiconductor-supply-chain.pdf

Financial Times. (2023). “China’s Curb on Metal Exports Reverberates Across Chip Sector”. Financial Times. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.ft.com/content/2fa865a7-176f-4292-8842-38bb6470d732

Flinders, M. and Smalley, I. (n.d.). “What is a semiconductor?”. IBM. Retrieved Nov 4, 2025, from https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/semiconductors

Intel. (2023). “What are Semiconductors?”. Intel. Retrieved Nov 5, 2025, from https://newsroom.intel.com/tech101/what-are-semiconductors

Khan, S. (2025). “China’s Rare Earth Stranglehold: A Global Threat to Defence and Tech”. Modern Diplomacy. Retrieved Nov 19, 2025, from https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/10/09/chinas-strategic-tightening-of-rare-earth-export-controls-implications-for-global-defence-and-semiconductor-supply-chains/

National Minerals Information Center. (2025). “Rare Earths Statistics and Information”. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Retrieved Nov 18, 2025, from https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/rare-earths-statistics-and-information

Nation Thailand. (2024). “Growth expected for Thailand’s HDD industry”. Nation Thailand. Retrieved Nov 20, 2025, from Growth expected for Thailand’s HDD industry

NXPO. (2025). “Thailand Talent Landscape 2025-2029”. NXPO. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.nxpo.or.th/th/report/32407/

OECD. (2024). “Chips, nodes and wafers: a Taxonomy for semiconductor data collection”. OECD. Retrieved Nov 10, 2025, from https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/08/chips-nodes-and-wafers_1189c2a2/f68de895-en.pdf

PWC. (2024). “State of the Semiconductor Industry: Trends and Drivers Shaping the Semiconductor Landscape”. PWC. Retrieved Nov 7, 2025, from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/technology/state-of-the-semiconductor-industry-report.pdf

Semiconductor Industry Association. (2025). “State of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry 2025”. SIA. Retrieved Nov 11, 2025, from https://www.semiconductors.org/2025-state-of-the-u-s-semiconductor-industry/

Stanford Advanced Materials. (2025). “Types and Classifications of Semiconductor Materials”. Stanford Advanced Materials. Retrieved Nov 12, 2025, from https://www.samaterials.com/blog/types-and-classifications-of-semiconductor-materials.html

Wafer World. (2024). “Rare Earth Metals and Semiconductors”. Wafer World. Retrieved Nov 19, 2025, from https://www.waferworld.com/post/rare-earth-metals-and-semiconductors

World Semiconductor Trade Statistics. (2020). “WSTS Product Classification 2021”. SIA. Retrieved Nov 10, 2025, from https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Product_Classification_2021.pdf

World Semiconductor Trade Statistics. (2025). “Global Semiconductor Market show continued growth in Q2 2025”. WSTS. Retrieved Nov 6, 2025, from https://www.wsts.org/esraCMS/extension/media/f/WST/7175/WSTS-Q2-Release-2025-08-04.pdf

Yamada Consulting Group. (2025). “Thailand’s Semiconductor and Electronics Industry”. Yamada Consulting & Spire. Retrieved Nov 13, 2025, from https://www.yamada-spire-th.com/market_research/thailands-semiconductor-and-electronics-industry/

1/ Types and Classifications of Semiconductor Materials | Stanford Advanced Materials

2/ Global Semiconductor Market show continued growth in Q2 2025 | WSTS

3/ Consists of the Discrete, Analog, Optoelectronics, and Sensors

4/ Globality and Complexity of the Semiconductor Ecosystem | GSA Global

5/ Calculated from Mine production in 2024, China produced 270,000 tons of rare earth, while global production reached 390,000 tons. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025 | USGS

6/ Emerging Resilience In The Semiconductor Supply Chain | Semiconductor Industry Association

7/ Ibid

8/ อุตสาหกรรม PCB ผู้เปลี่ยนเกม ขับเคลื่อนไทยสู่ผู้นำเทคโนโลยีในภูมิภาค | BOI, คาดใน 3-5 ปีไทยชิงแชร์ตลาด PCB เพิ่มจาก 4% เป็น 10% | LINE TODAY

9/ Growth expected for Thailand’s HDD industry | The Nation, 'อุตสาหกรรมเซมิคอนดักเตอร์ไทยแข็งแกร่งตั้งแต่ต้นน้ำถึงปลายน้ำ' วลีนี้เป็นได้มากกว่าภาพฝัน | NSTDA

10/ ที่มา: สมาคมแผ่นวงจรพิมพ์ไทย (THPCA), รายงานการศึกษาเชิงลึกของอุตสาหกรรมวงจรพิมพ์และอุตสาหกรรมเกี่ยวเนื่อง | สถาบันไฟฟ้าและอิเล็กทรอนิส์ (ThaiEEI), Thailands Semiconductor and Electronics Industry | Yamada Consulting Group

11/ ประกาศคณะกรรมการส่งเสริมการลงทุน เรื่อง การปรับปรุงการส่งเสริมการลงทุนอุตสาหกรรมเซมิคอนดักเตอร์ (16 ก.ย. 2564) | BOI

12/ Trademap และ ห่วง 7 กลุ่มสินค้า RVC ต่ำ ภาษี 40% เร่งต่อรองสหรัฐ | ประชาชาติธุรกิจ

13/ การสำรวจความต้องการบุคลากรทักษะสูง ในอุตสาหกรรมเป้าหมาย พ.ศ. 2568-2572 | สอวช.

14/ มูลค่าการอนุมัติส่งเสริมการลงทุนสะสมตั้งแต่ปี 2566 ถึงเดือน มิ.ย. 2568 อยู่ที่ 6.5 แสนล้านบาท คิดเป็นสัดส่วนสูงถึง 24.6% ของมูลค่าการส่งเสริมการลงทุนทุกประเภท

15/ จำนวนโครงการด้านอิเล็กทรอนิกส์ขั้นสูงที่ขอรับการส่งเสริมการลงทุนยังคงเพิ่มขึ้นต่อเนื่อง จาก 58 โครงการในช่วง 6 เดือนแรกปี 2566 เป็น 113 โครงการ ในช่วง 6 เดือนแรกปี 2568

16/ มูลค่าตลาดเซมิคอนดักเตอร์ทั่วโลกคาดว่าจะเพิ่มขึ้นจาก 0.6 ล้านล้านดอลลาร์สหรัฐในปี 2567 เป็น 1.0 ล้านล้านดอลลาร์สหรัฐในปี 2573 ที่มา: State of the semiconductor industry | PWC

17/ อาทิ Microcontroller Units (MCU), Graphics Processing Unit (GPU), และ High Bandwidth Memory (HBM)

18/ อาทิ Radio-Frequency IC, Application-Specific IC และ Analog IC

19/ อาทิ Power IC, Sensor IC และ Microcontroller Unit

20/ China’s curb on metal exports reverberates across chip sector | Financial Times

21/ ห่วง 7 กลุ่มสินค้า RVC ต่ำ ภาษี 40% เร่งต่อรองสหรัฐ | ประชาชาติธุรกิจ, ภาษี 19%สหรัฐ ซัด 'อิเล็กทรอนิกส์ไทย'! ดีมานด์หด ผู้ผลิตเร่งปรับตัวรับมือ ‘เกมใหม่’ | กรุงเทพธุรกิจ