In response to the outbreak of COVID-19, governments around the world instituted a broad range of strict social controls to slow the spread of the pandemic, with these tending to involve lockdowns and restrictions on international travel, and although these measures have helped to save lives, they have also imposed a very heavy economic cost in the form of a dramatic decline in global economic output and constrained international trade. Given Thailand’s status as a major exporter, the country has not escaped the impacts of these disruptions to global value chains, but the consequences of these events will extend far beyond the short-term, and 2020’s unprecedented economic turmoil will likely act as a catalyst accelerating the changes being wrought by megatrends that were already playing out on the world stage, whether that be changing patterns in demand, uncertainty over trade policy and the siting of production facilities, or the growing impact of technology on economic life. How these factors take shape and evolve will be key to determining how future value chains become shorter, more diversified and more regionalized.

Prompted by this likely transformation of supply chains, Krungsri Research has used the input-output tables to analyze the probable shape of global value chains in 2025, and this has revealed three important findings. Firstly, Thailand’s participation in global supply chains will increase but the country’s position within these is not expected to change markedly, secondly, there would be a trend of servicification, and finally, regionalization should increase. From this, and if they are to prepare themselves successfully, Thai companies need to become aware of how the post-crisis business environment will be altered. Those organizations that are sufficiently flexible to adapt to this changing situation should then be to meet future challenges.

Modern production is such that manufacturing particular goods often depends on coordinating the assembly of raw materials, components and expertise that is distributed across many different countries, and because of this, each of the stages of production involved in what can be very complex supply chains helps to add value to the finished goods, disseminate knowledge and know-how between companies, and integrate economies across the world. This global distribution of production thus helps to pull individual national economies into global value chains (GVCs).

Given their role as drivers of increased manufacturing capability, investment and employment, through which they support economic growth and improvements in standards of living, these global value chains are extremely important, but when each stage of a supply chain is connected to all the others, the consequences of changes in one part of the production process are rapidly felt throughout the whole, with contagion potentially spreading along the supply chain and into economies in all regions of the world, as has been the case during the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, since the outbreak of the disease at the start of 2020, the Thai economy has been impacted far beyond the obvious case of the tourism industry, and the linkages between the Thai economy and global supply chains have meant that the effects of the pandemic are clearly reflected in this year’s sharp fall in imports and exports. Nevertheless, the crisis has also helped to raise awareness of the importance of managing risk arising from the siting of production facilities and the need to unravel some degree of economic interdependence and doing this will go some way towards determining how future value chains are structured. Understanding how these changes will unfold will thus not only enable businesses to better manage risk but will also allow manufacturers to seize global market and investment opportunities.

The Thai economy has been battered by the COVID-19 crisis, and trade channels have been a major vector through which impacts have been transmitted

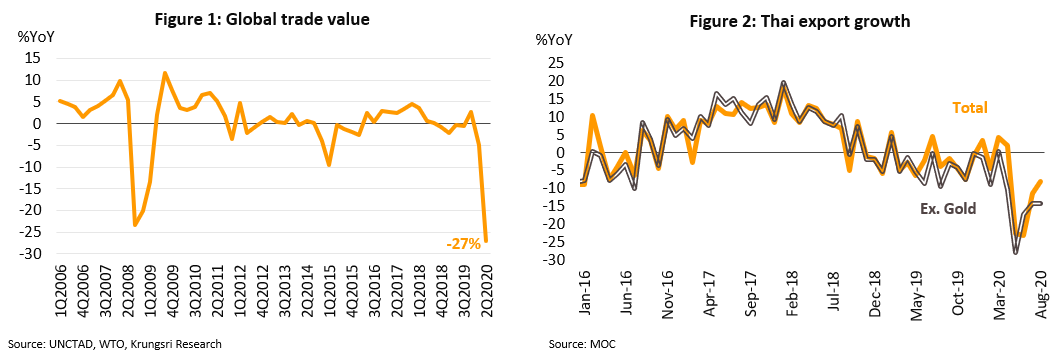

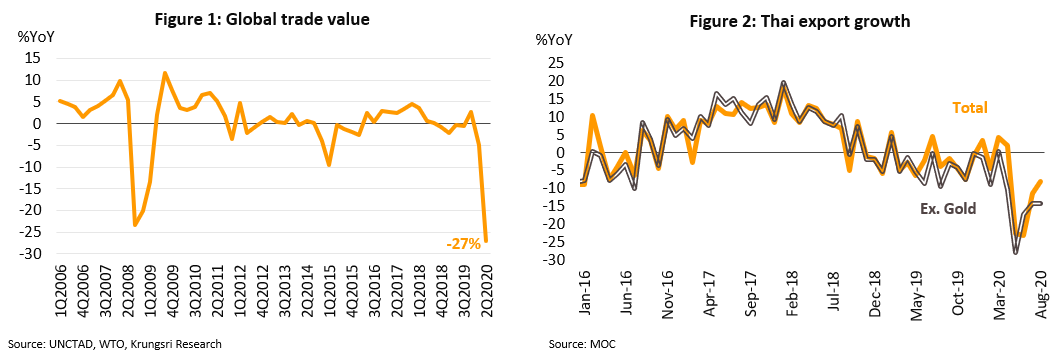

Although the COVID-19 crisis began as a public health issue, the slump in output and demand that it has precipitated has triggered a major global economic problem, with trade channels acting as the channel that have transmitted these economic woes worldwide. Data from UNCTAD shows that the global trade in goods fell by more than -5% in the first quarter of the year compared to the previous year, and it is expected that for the second quarter, when the epidemic was at its peak, the decline will hit -27% (Figure 1). These figures are in agreement with those of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which forecasts that world trade will fall by between -13% and -32% in 2020, the wide spread of the forecast indicating the uncertainty of the world economy.

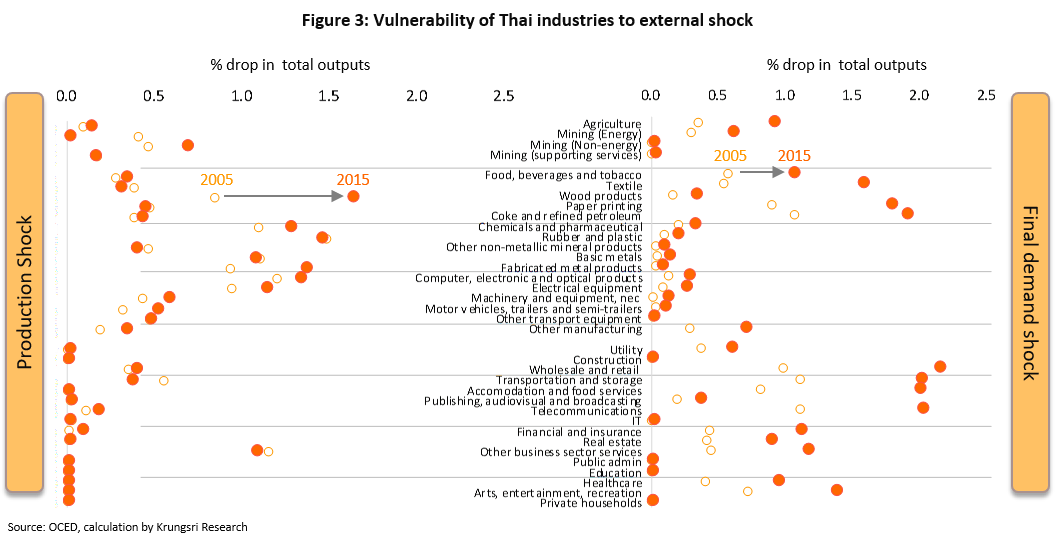

With a sharp contraction in global trade underway and high levels of uncertainty over the outlook for the world economy, the Thai export sector, which has historically been a significant underwriter of domestic economic growth, has naturally struggled against headwinds on both the supply and demand sides of the market. The latest data from the Ministry of Commerce shows that for the fourth month running, Thai exports have weakened, falling in August by another -7.9% (Figure 2) as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage in many countries and the number of cases rises ever upwards, undercutting global demand. These declines are particularly important because, since the Plaza Accord of 1985, Thailand has been host to production facilities for a large number of international companies, becoming in the process a major regional industrial power and this has created deep links between Thai industry and global economy, as a result of which during normal periods, the country imports large quantities of inputs for use in manufacturing processes and then exports these finished goods to other countries.

Thai industry is exposed to risk from both production and demand, and these risks are escalating

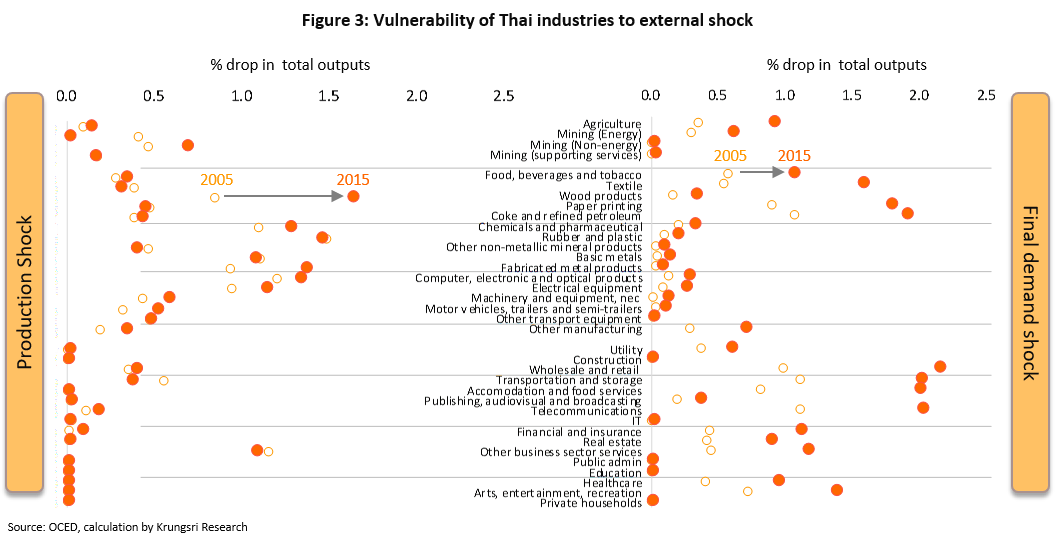

Krungsri Research has used the input-output tables to analyze linkages between Thai industry and global value chains between 2005 and 2015, and this analysis shows that Thai industry is sensitive to shocks to both production and final demand. However, whereas technology-dependent industries such as electronics, machinery manufacturers and auto assembly respond rapidly to the supply disruption, basic industries such as food and beverages production and the textiles industry are, together with the service sector, more sensitive to changes in demand. Significantly, Thai industry is increasingly exposed to these risks, and one can assume that if risks are rising in the global economy, the impacts of these on the Thai economy will likewise rise (Figure 3).

Trends in economic growth and trade in the post-COVID-19 environment

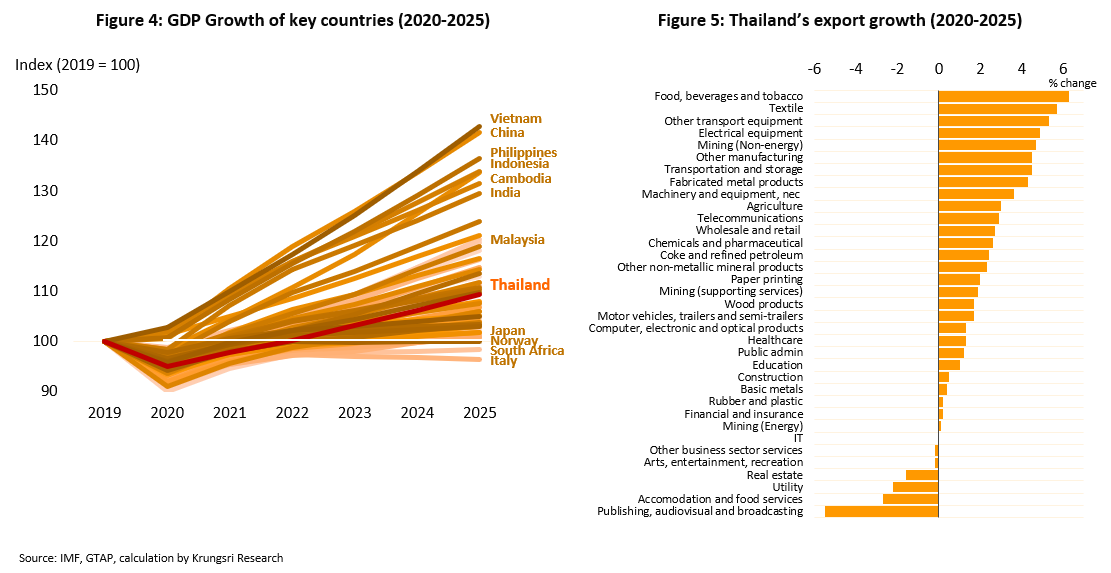

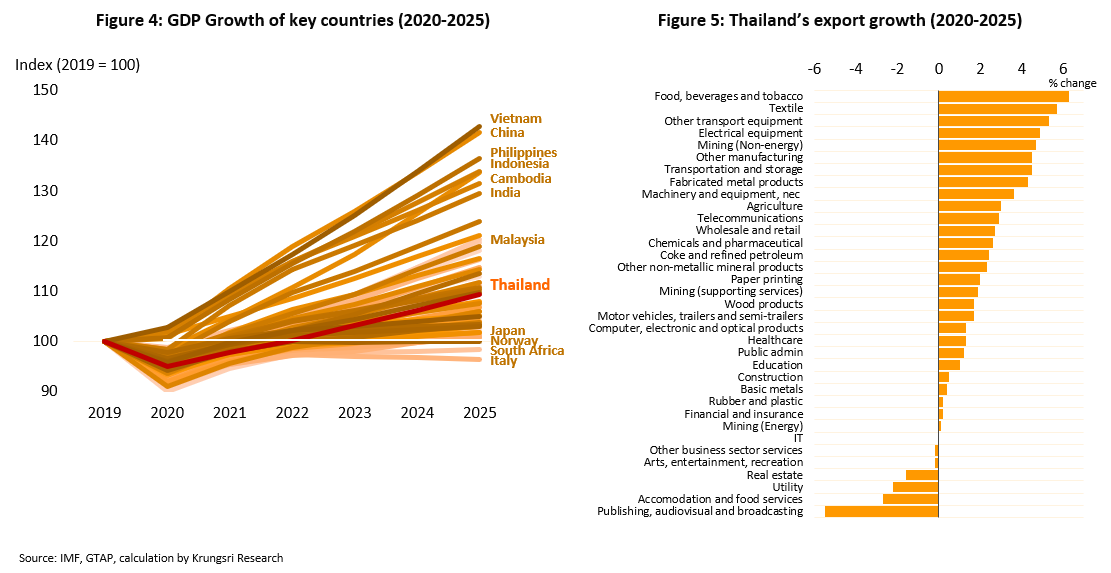

Krungsri Research sees global economic recovery being staggered, with different countries rebounding at different rates. Over the period 2020-2025, the most rapidly rebounding countries will be, in order, Vietnam, China, the Philippines and Indonesia, while the slowest will include Japan, Norway, South Africa and Italy, which may take more than 5 years to return to their pre-COVID-19 state. Thailand is expected to sit between these two groups, with recovery taking 3-4 years. The drop in the value of international trade during the COVID-19 crisis has also added to widespread fears in business and industry over the pace of recovery but looking forward, the rebound in the world economy would remain a positive factor supporting an improvement in the situation for exports, and this will brighten the outlook for the Thai economy. In fact, an analysis of forecast growth in exports from 2020 to 2025 shows that income-sensitive industries (those that produce goods with a high price elasticity of demand) will be on the leading edge of the recovery, most notably suppliers of food and beverage products, followed by transport equipment and electrical equipment, since when the COVID-19 crisis abates, consumer purchasing power will rebound and demand for goods and services in these categories will be quickest to respond (Figure 4).

COVID-19 and megatrends will transform Global Value Chains

COVID-19 pandemic has both short-term and long-term effects on Thai economy. In the short term, the outbreak forced many countries into national lockdowns as they strived to hammer down rates of domestic transmission, and this then caused economic activity to slow dramatically, unemployment to explode, and consumption to crash, and when this was added to the slump in imports and exports, many economies naturally slid into deep recessions, with the GDPs of many countries seeing their worst performance since the global financial crisis of 2008-09. Over the long term, the epidemic may also leave deep scars on the economy, although it will transform it in the process. This is because labor productivity has fallen and economic growth may drop below its potential, leaving an unrecoverable gap in output, while businesses will need to be more flexible and more agile in responding to future challenges, but beyond this, the protracted slowdown in international trade may push some countries to reconsider their economies’ relative dependence on internal and to control potential losses by spreading the risks that arise from distributed production facilities. These factors will thus have a major role to play in shaping future global value chains.

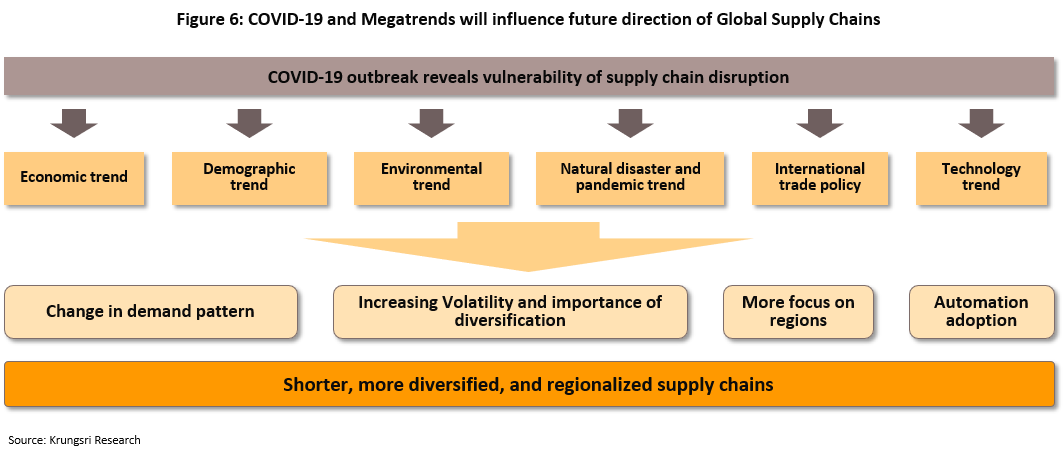

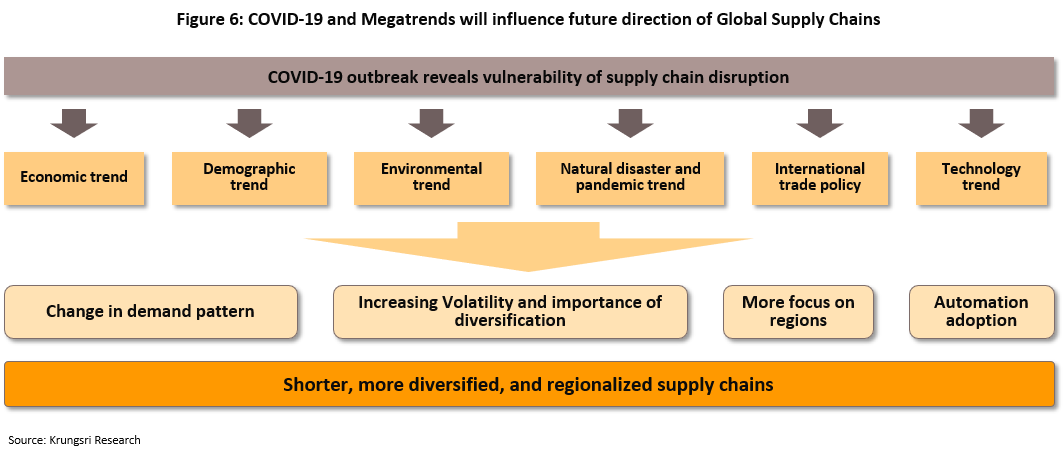

COVID-19 may also have indirect effects on global value chains by accelerating the impact of megatrends, and Krungsri Research see 6 megatrends reshaping global supply chains (Figure 6).

Economic factors will affect global value chains through changes in global economic power and the increasing importance of emerging markets, including China, Vietnam and South Korea. Growth in these countries’ GDPs is outpacing that of the developed economies and their purchasing power is thus relatively stronger, such that these are now attractive targets for manufacturers to expand their markets. Demographic and social considerations will also have a role to play, and in the 21st century, the trend across much of the world will be for societies to age, in some cases very substantially, and so patterns of demand for goods and services will likewise shift, with happy consequences for companies that meet the needs of elderly consumers but with the unfortunate side-effect of reducing the size of the workforce, possibly leading to labor shortages, which would then hit production. These two factors will then help to shape future demand pattern.

Environmental factors become greater influential. In addition to achieving the highest efficiency, production planning will also have to consider sustainability and environmental impacts, and to balance between traditional business purposes and possible environmental costs. Also, considerations over the potential impacts of natural disasters and pandemics will play a greater role, particularly now that COVID-19 has highlighted so many potential pitfalls for business, especially of how concentrating production facilities in a single location can cause major production problems through the economic system. This is also taking place against the background of the ‘VUCA world’ (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity) and so to ensure the long-term security, manufacturers need seriously to consider how to reduce these risks, for example, by dispersing production facilities and by increasing the focus on maintaining corporate flexibility in the face of change, rather than maintaining the more usual single-minded obsession with achieving the highest possible level of efficiency.

Due to the attempt to increase reliance on domestic markets, international trade will be another factor molding the economy in the coming period, and in fact, in the past few years, several countries have begun to introduce protectionist measures as they try to support domestic industry and markets. The United States has been a notable example of this, with the current administration deploying nationalist policies as it seeks to emphasize the production, distribution and consumption of goods internally while reducing reliance of production outside the country, for example, in China, even though reversing the offshoring trend is no easy matter and organizations that attempt to bring production back to domestic sites have to overcome significant problems with maintaining their cost structure and standards if they are going to be able to offer goods and services that continue to meet the demands of the market. However, rapid technological progress can make huge contributions to addressing these challenges and surmounting the problems involved in onshoring and thus, technological factors will also have an impact on the evolution of global value chains.

These profound changes in the world economy, together with COVID-19 consequences, are now determining the changes in global value chains. Corporations are thus now attempting to unpick some of the complexity, while also trying to shorten the distance between production sites and their home country or to disperse production among a larger number of countries and so reduce the risk of losses in the event of another crisis or from trade policy that is becoming steadily more aggressive. Because of this, countries are now looking for distribution channels for goods that are closer to production sites or that are in the same region as these, and these factors are now influencing the restructuring of value chains, making them shorter, more diversified and more regionalized.

Krungsri Research has carried out research to investigate what the development of these short, diverse and regional supply chains will mean for Thai industry by 2025, and this has revealed three main findings: increasing Thailand’s participation in global supply chains, the role of servicification, and regionalization.

I. Thai participation in global value chains will increase but Thailand’s position in supply chains will be unaffected.

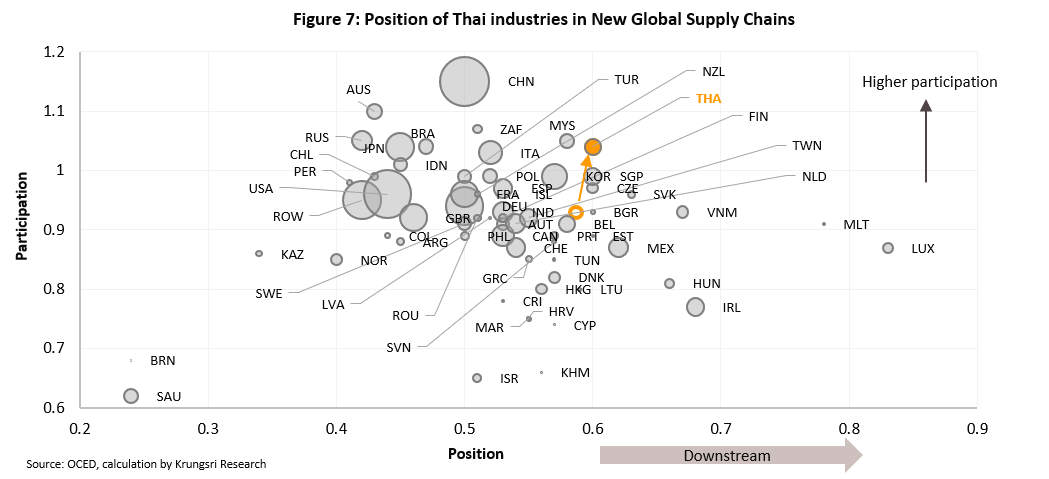

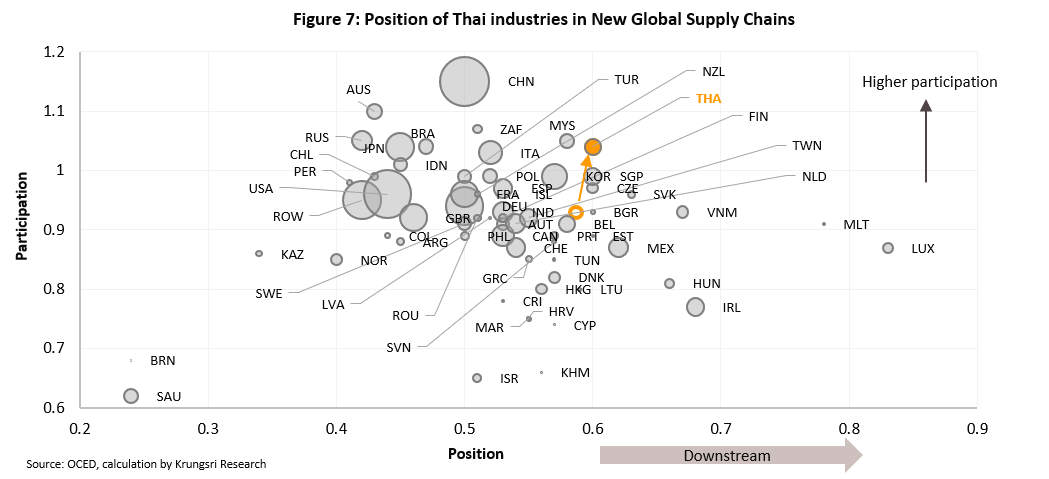

Any analysis of the role of a country in global value chains needs to begin from an understanding of both participation and position of that country in global supply chain. In the case of Thailand, over the next 5 years, the country’s participation in global value chains will rise and its index of participation is forecast to increase from a value of 0.93 in 2020 to 1.03 in 2025 (Figure 7), while its role within those supply chains will remain largely unchanged, that is, the country will remain in a somewhat downstream position. These two forecasts represent a prime opportunity for Thai manufacturers, and in this situation, Thai industry should be able to benefit from its longstanding manufacturing expertise.

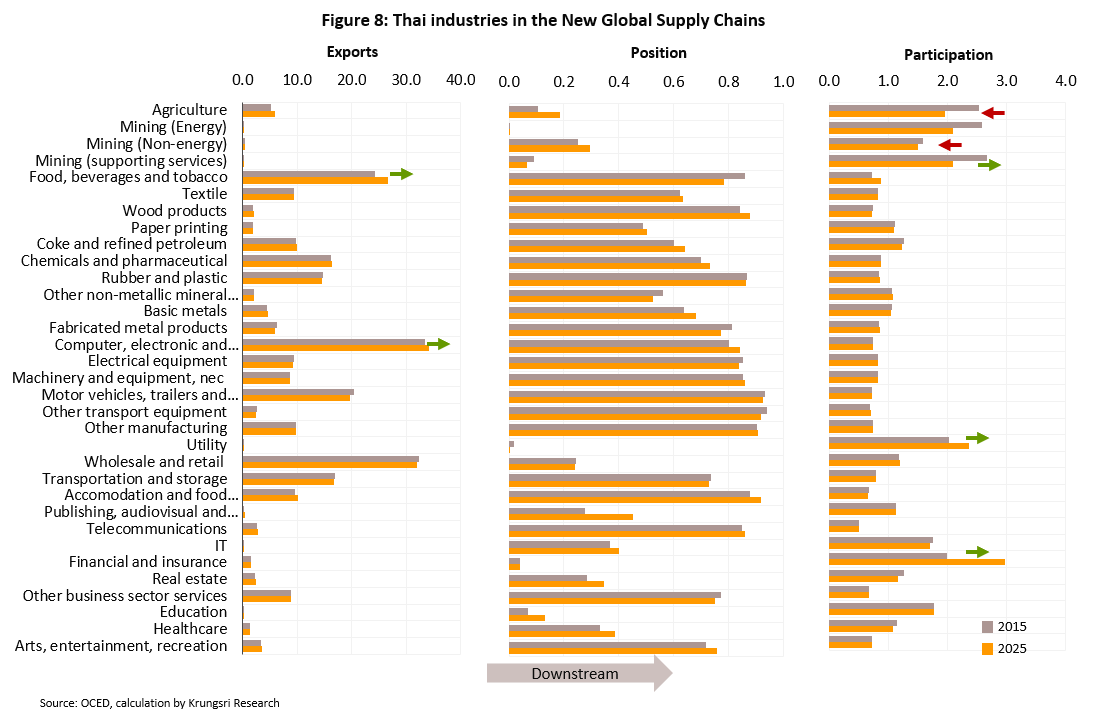

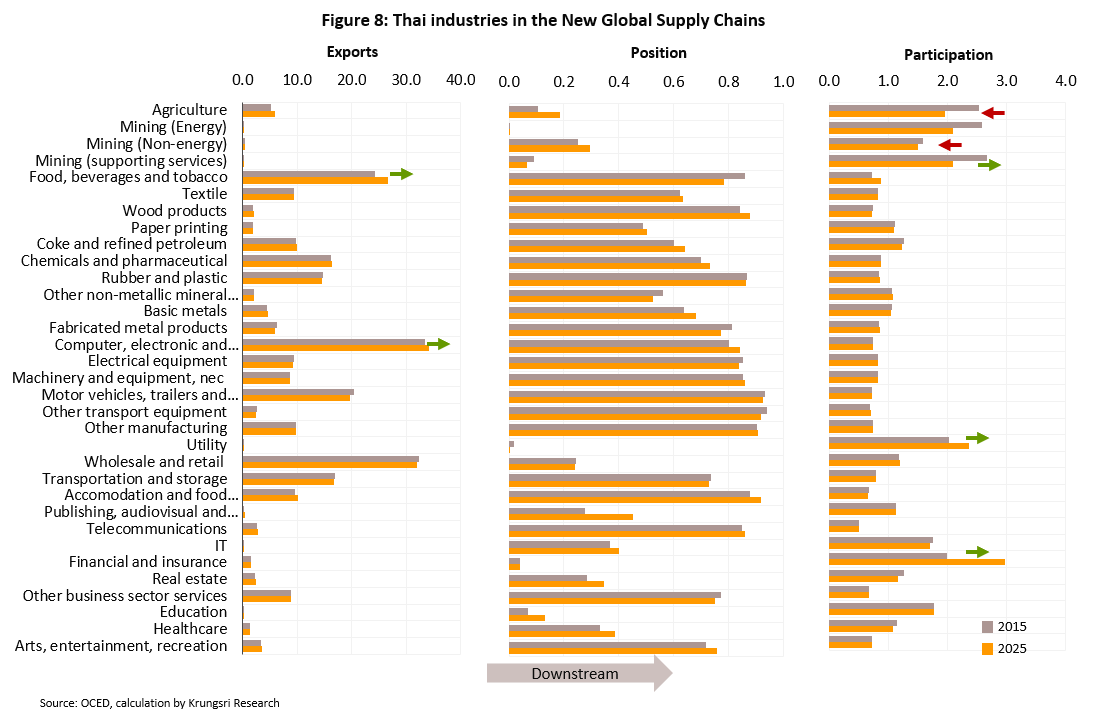

Nevertheless, changes in value chains will affect different industries in different ways, depending on how participation rates in supply chains alters and how successful each industry is at exporting its outputs (Figure 8).

- Industries that will benefit from these changes are those that will tend to see their participation in global value chains increase because competition in global markets will increase their production capabilities and efficiency, and if players in these areas are able to lift their exports in the near future, this will naturally support growth in those same industries. Examples of industries in this group include food and beverages suppliers and manufacturers of computers and electronics.

- Industries that will tend to lose out from these changes will be those that will see participation in global value chains decline. These tend to be upstream industries, and they may experience a fall in demand because their ability to exploit the raw materials and technology that global value chains make available drops, or because growth in exports from these industries weakens or even stalls completely. Members of this group include agriculture and mining.

II. Servicification

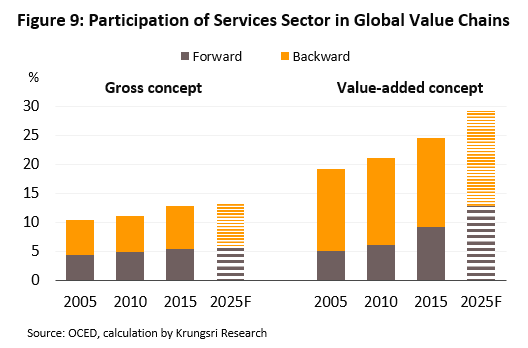

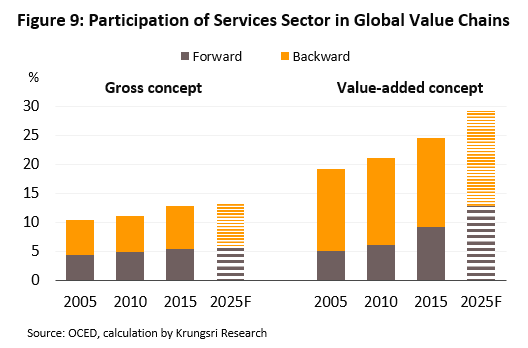

Recently, expansion in the global economy has been built on growth in value, a process that has in turn been underpinned by advances in technology, knowledge and innovation, and through this, the service sector has now become a major driver of the economy, helping to sustain growth in value by increasing manufacturing capabilities and raising competitiveness, which are important factors in building economic growth. In addition, technological progress and the world of industrial production are seamlessly connected, and this means that the deepening and broadening of linkages between manufacturing and the service sector that has happened in the recent past can be expected to continue into the future. Looking out over the next 5 years, given the trends in increasing added-value, participation by the service sector in global value chains is forecast to rise to 28% (Figure 9).

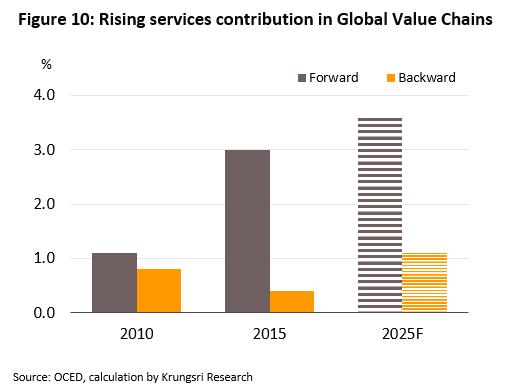

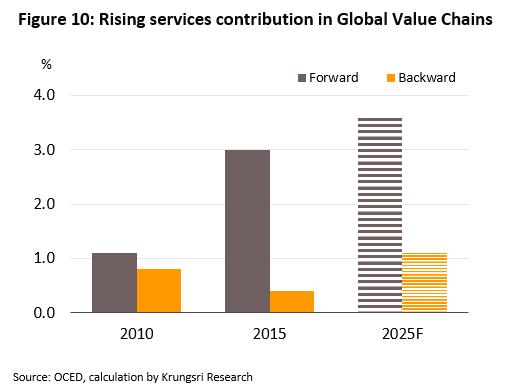

Looking at the forward linkages, the added value that services contribute to manufacturing is forecast to rise from around 3% in 2015 to 3.6% in 2025, underlining the fact that services have a role to play beyond the manufacture of downstream goods, and that the service sector will increasingly participate as intermediate goods, too (Figure 10). This newly evolving relationship differs from the situation in the past, when services were considered as final product, for example, in the way that auto distribution was tied to after-sales services, insurance, and servicing. However, in this new environment where services are ever-more important, the rate at which innovation in, for example, automotive products moves forward can be expected to accelerate thanks to efforts in research and development and to advances in transportation and communication, factors that also help to add value to these products.

From this, businesses need to transform themselves by integrating the service sector into their operations, which would then allow them to better benefit from services’ ability to help manufacturing add value to their products. Successfully exploiting these developments will also increase players’ involvement in global value chains since in addition to providing businesses with short-term gains in the form of increased opportunities and better profits, over the long term, they will also see their competitiveness increase and be better placed to adjust to future changes in the economy.

III. A global reordering of supply chains will increase regionalization

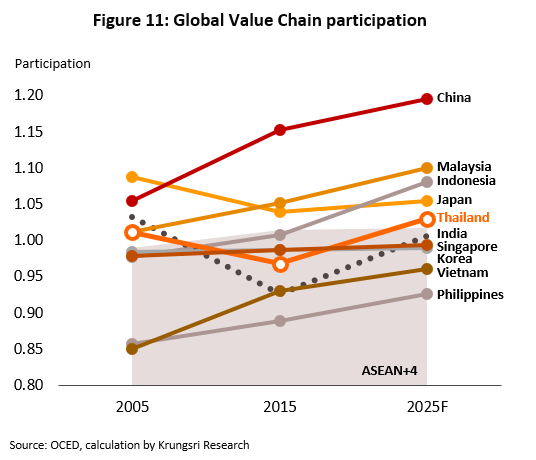

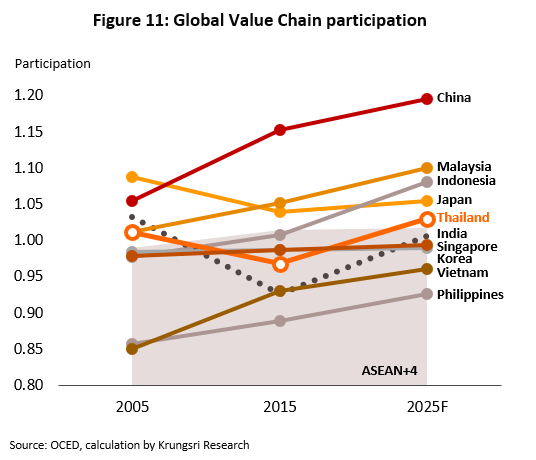

Looking at the participation in global value chains by the ASEAN+4 group of nations (the ASEAN member states together with China, Japan, South Korea and India), these countries will tend to increase their mutual interdependence. Analysis shows that individually, participation in global supply chains by the ASEAN+4 countries will increase at a faster rate than will participation by the group as a whole, indicating that increases in participation will be due to greater regional integration (Figure 11). In addition to greater regionalization, the domestic purchasing power in these countries is also expected to rise significantly in the coming period.

In the past, technological limitations tended to amplify the problems involved in manufacturing in different locations, since expertise, technological know-how and raw materials varied from region to region, but the rapid development of technology is helping to overcome these problems. At the same time, industry is being affected by stricter controls on international trade and rising risks. So, manufacturers are now showing a greater tendency to look for production sites close to the markets to better serve demand. One consequence of which is that because of their relative homogeneity, regional markets are becoming more attractive. Beyond this, the recent interest in shortening and simplifying supply chains is also tending to bolster greater regional trade and integration.

The combination of regional economic growth and a greater reliance on regional markets will present an opportunity to Thai corporations in terms of both manufacturing and investment, although given the likely future importance of local competition, Thailand is also fortunate in being a major center of production that is located close to regional markets, allowing manufacturers to easily distribute goods and so meet consumer needs. This greater focus on the local region will also allow for the more systematic management of risk and an increase in manufacturing efficiency.

Krungsri Research’s view

The outlines of the post-COVID-19 world are still hard to make out, but it is clear that whatever shape this new world takes, life will never be the same again, whether that be with regard to the individual, where social distancing may become a permanent new social norm, or to how answers to business and economic problems are formed. Thus, international relations may be turned upside down by the crisis, especially with regard to global trade and manufacturing linkages, and the global value chain would change from lengthening to shorter chain, from taking advantage of expertise and geographical concentration to more diversification, and from globalization to regionalization. These are done to reduce risks and to better meet market needs.

It is becoming clear that Thai businesses’ participation in global value chains will increase and industries that will benefit from this process need to move to increase their capabilities, while the likely greater role of the service sector in building added-value for manufacturers will also increase the need for businesses to integrate services into their production processes. In addition, the trend to greater regional integration and consumption will also open the door to locally-sited Thai industries to better meet this growing demand, providing that they are able to compete on the regional level. Most importantly, though, with the changes to global value chains that are expected in the near future, a key to business success in the coming period will be staying abreast of how these transformations are unfolding and then preparing to adjust to and to exploit these challenges.

In the past, technological limitations tended to amplify the problems involved in manufacturing in different locations, since expertise, technological know-how and raw materials varied from region to region, but the rapid development of technology is helping to overcome these problems. At the same time, industry is being affected by stricter controls on international trade and rising risks. So, manufacturers are now showing a greater tendency to look for production sites close to the markets to better serve demand. One consequence of which is that because of their relative homogeneity, regional markets are becoming more attractive. Beyond this, the recent interest in shortening and simplifying supply chains is also tending to bolster greater regional trade and integration.