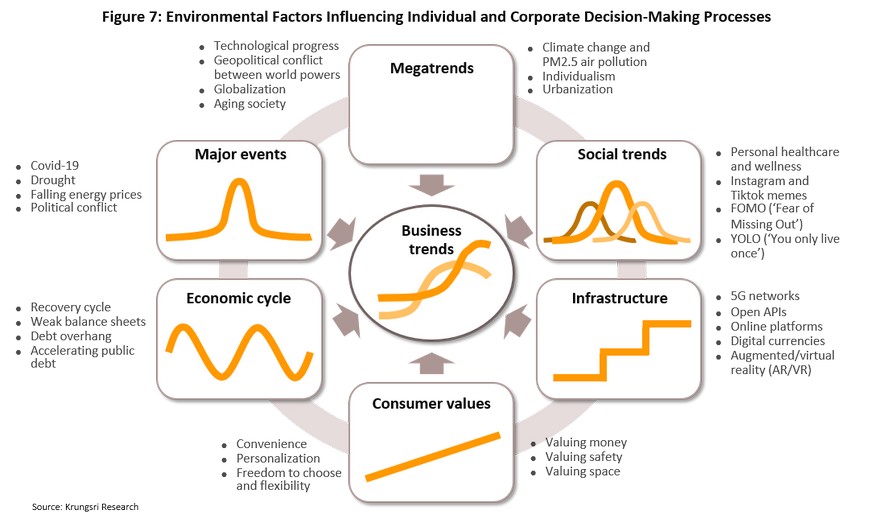

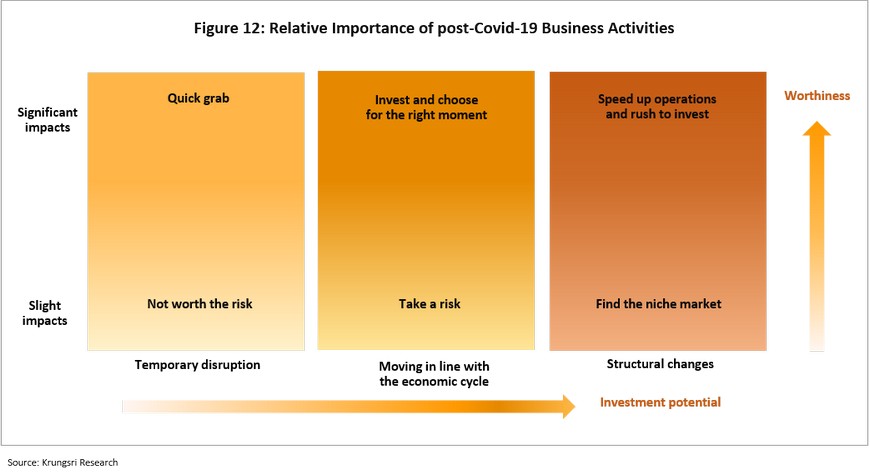

By ordering changes according to their degree and the length of their effect, it allows players to focus their attention where it is most deserving particularly that are supported by the widest variety of trends since these will have the greatest and longest impact. Next in importance are those changes that are moving in a direction with long-term trends but which are not as widely supported by factors in the business environment. Finally, changes that will only short-live are likely not worth investing in. (Figure 12)

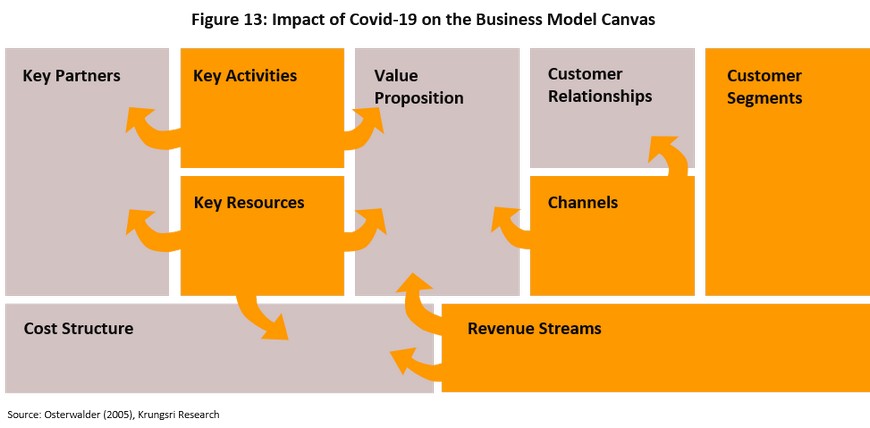

Evaluating the impacts of Covid-19 on business models using the ‘business model canvas’[15] shows that the crisis has had direct effects on businesses, but because of the interconnections between these effects, each has then had further impacts on other aspects of the business (Figure 13).

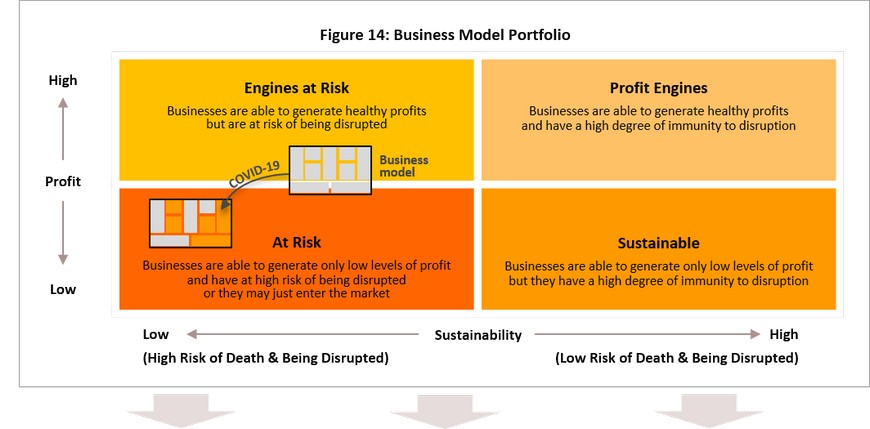

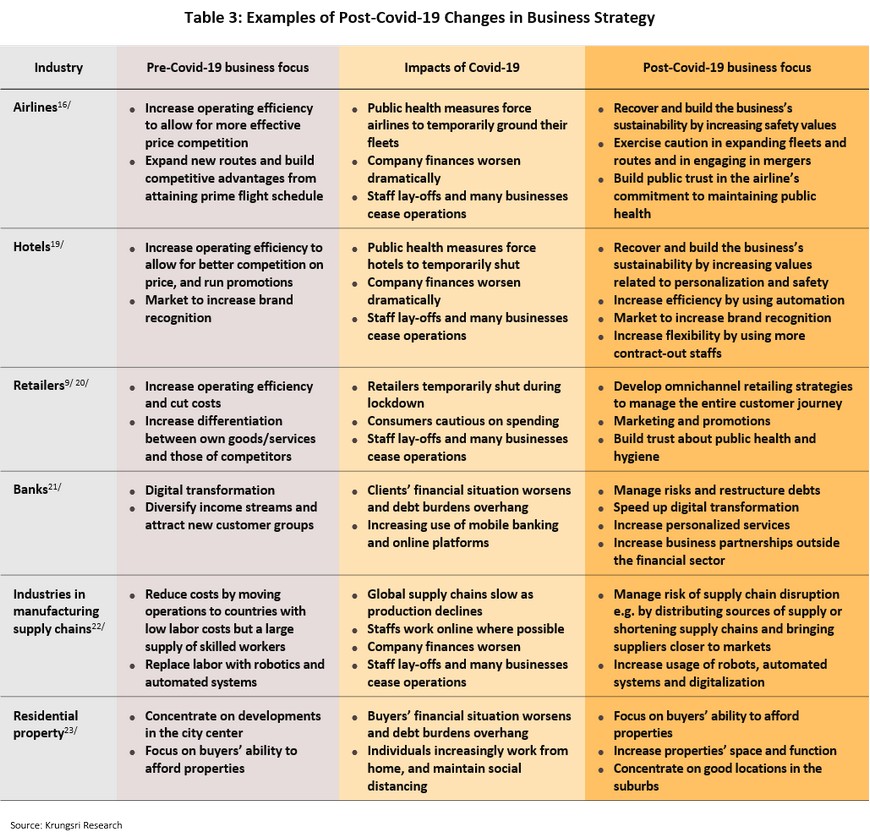

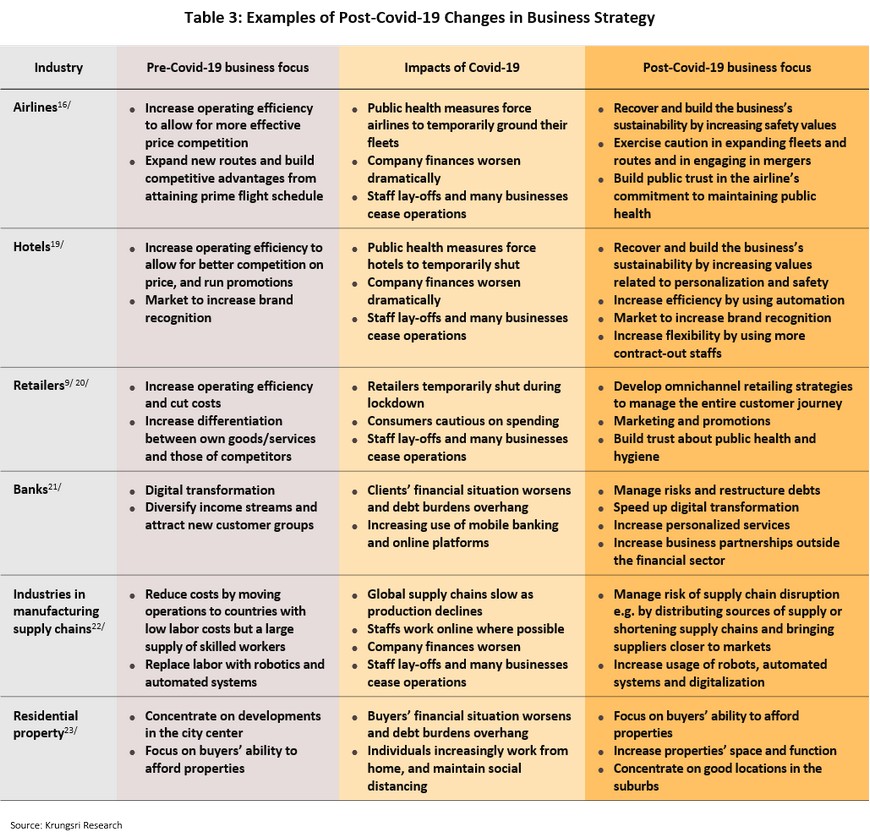

Other industries that have fallen into the ‘at risk’ group following the outbreak of Covid-19 include the following (Table 3).

- Hotels[19]: Pre-Covid-19, firms typically competed on price, running promotions to attract customers and advertising through online platforms and travel agents, which generally charge a fee of at least 15% of the monies paid for bookings. This then resulted in operations typically having fairly low profits but high fixed costs, while it is difficult for hotels to generate repeat customers, and this then put them in the ‘engines at risk’ category. However, the pandemic has had immediate and direct impacts on hotels, which have only been very slow to reopen following lockdowns and this has had serious consequences for operations’ financial status, pushing them into the ‘at risk’ category. Hotels will thus need to revamp their business models, though initially most important will be developing strategies that build consumer confidence and that are in line with the seven values described above, especially values that relate to providing safe services and reassurance to clients. Also important will be providing especially noteworthy services that result in customer recommendations and looking again at ways to improve operations with regard to cost management and flexibility.

- Retail operations[20]: The crisis has had an important influence on consumer behavior, increasing consumers’ familiarity with online shopping and reducing their willingness to shop in crowded indoor spaces, such as department stores. Because of this, in the post-Covid-19 business environment, retailers that will perform best will be those that have built efficient online communications and distribution channels, while operations that continue to rely solely on offline channels will find themselves moving to the ‘engines at risk’ or ‘at risk’ categories. Retailers therefore need to adjust their operations by creating a unified strategy for their off- and online outlets (or so-called ‘omnichannel retailing’) that provides the optimal customer journey, drawing on the unique benefits of each; online distribution offers the greatest convenience for shopping and delivery but offline outlets allow customers to see goods in the flesh and to try them out before making a purchasing decision. If retailers are successful in adopting this mixed approach, they will be able to offer customers a more satisfying experience than was available under earlier business models, and this will help to move them back to the ‘sustainable’ or ‘profit engine’ categories.

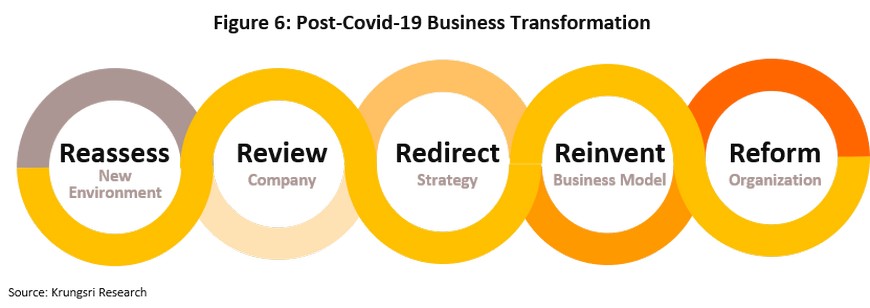

3. REDIRECT: Transform the business to thrive in the post-Covid-19 world

Clayton Christensen, the Harvard economist and thought-leader on business innovation[24], shows that business innovation should aim at creating disruptive business models that can provide services that are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller and more convenient to use, rather than simply increasing efficiency, cutting costs or engaging in research and development. An example of this is provided by Netflix, which revolutionized the video industry[25] and in the process killed Blockbuster, an earlier market leader with over 10,000 video rental outlets. In 1997, Netflix entered the market with a new business model, offering a monthly subscription service that delivered videos direct to individuals’ homes through the mail. A decade later, the company turned its business upside down by developing a video streaming service, at which point the video rental market collapsed and a new market for online streaming was born.

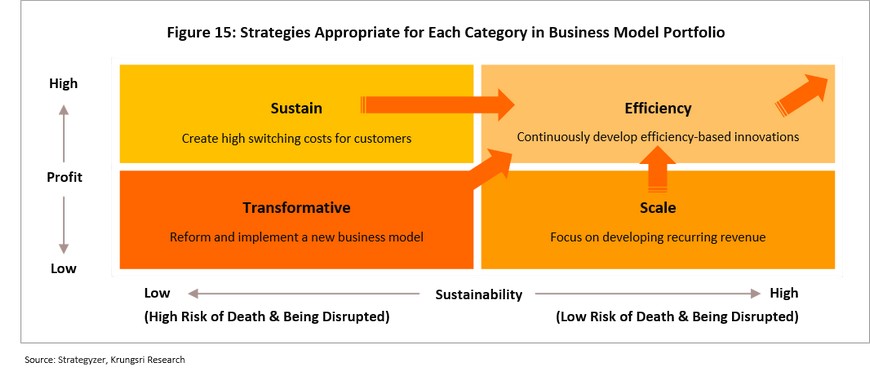

Another example of a company that has adjusted its business model repeatedly as it has moved to sustain the scale of its profitability can be seen in the Nespresso coffee capsule brand[26]. Having invented the concept of the coffee capsule and then creating coffee machines that could use these, Nespresso began life as a business to business operation (B2B) trying to sell its products to restaurants and offices, but this proved to be somewhat unsuccessful. Nespresso then reinvented itself as a business to consumer (B2C) operation, selling its goods to the public. The company also separated distribution of Nespresso machines from the capsules, selling coffee makers through retail outlets to increase its customer base because once somebody had a Nespresso machine at home, their only option was to buy replacement capsules directly from Nespresso itself, which could be done in shops, by phone or online. This business model had the advantage of enforcing high switching costs for existing customers if they decided to use a coffee machine made by a competitor and of ensuring recurring revenue from existing customers, who needed constantly to buy new supplies of coffee. However, Nespresso’s patent expired in 2012 and at that point, competitors flooded the coffee capsule market with alternative products, forcing Nespresso to again overhaul its business model as it looked to re-establish its sustainability, and at the start of 2018, the company joined with Starbucks to sell Starbucks-branded Nespresso capsules to the company’s huge number of loyal customers in America and Asia.

Within the Thai context, PTT[27] provides an interesting case study of a company that has overhauled its business model and, in the process, become a market leader. Initially, transnational players, including Shell, Esso and Caltex, had a stranglehold on the service station market because of the greater trust on fuel quality that Thai consumers put in them relative to domestic players. However, through the intelligent use of marketing campaigns upcountry, PTT built national recognition to compete against these transnational players. The most important turning point coming in 2002 when PTT expanded its operations to include activities outside the scope of simply selling fuels. This included partnering with 7-Eleven and launching the Café Amazon brand and not long afterwards, PTT opened service stations offering a full range of services under the brand ‘PTT Life Station’, as well as then acquiring Jet (another service station operator) in 2007, together with its chain of convenience stores, Jiffy. From this point onwards, PTT has consistently maintained its position as the market leader in service stations in Thailand, with its operations being notable for the quality of their non-fuel services and the full range of conveniences.

Osterwalder[28] also notes that there are lessons to be learnt from leading companies in the ‘profit engine’ category and these players often share three characteristics. (i) Engage in a continuous process of reinventing their business model because the rapid pace of technological change is forcing the business world to evolve at an ever-faster rate and often taking completely unforeseen forms. (ii) Compete on establishing superior business models, not through a rat race on new products, services, prices and technologies alone. (iii) Transcend or even tear down industry boundaries as they move out of their earlier area of competition and constantly enlarge the business territory within which they build value. Their action is then not confined in any particular industry or industry forces but being in business arenas that extend beyond traditional industry boundaries.

4. REINVENT: The path to business excellence in the ‘new normal’

“All you touch will not turn gold.

Make many small bets to catch

one success”

- Strategyzer,

the author team of “The Invincible Company”

In the post-pandemic business environment, the kinds of business plans that were used earlier may well turn out to be useless because, in a world that is marked by its rapid degree of change and high level of uncertainty, producing forecasts based on assumptions may very well lead to their failure.

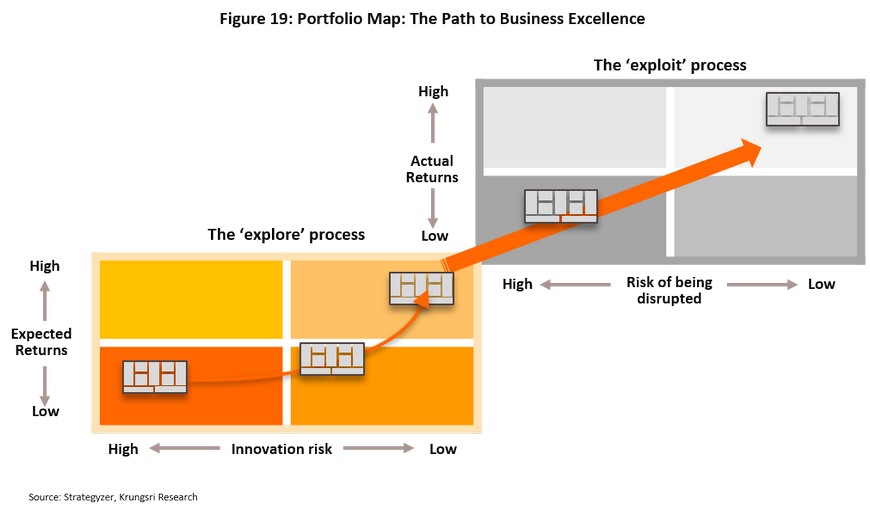

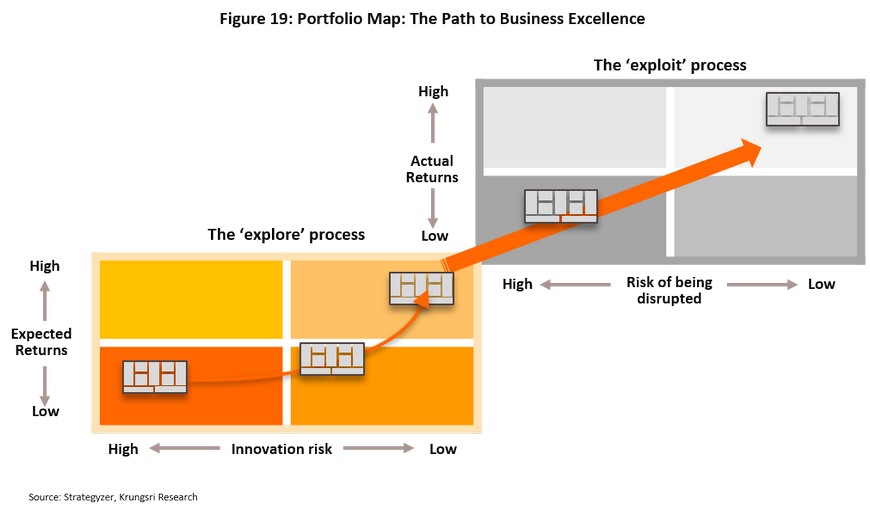

In light of the above, Osterwalder[28] suggests that businesses would be better served by making a large number of small investments in a wide range of projects and then gradually raising their involvement as time goes by, rather than making high-stakes, high-value wagers in a small number of investment projects. This way of operating is similar to the investment strategies that venture capitalists use when funding startups. But, in this case, it is used internally within an organization, originating in a bottom-up fashion that involves staffs at all levels. These types of processes can be divided into two classes, which are labeled ‘explore’ and ‘exploit’ strategies.

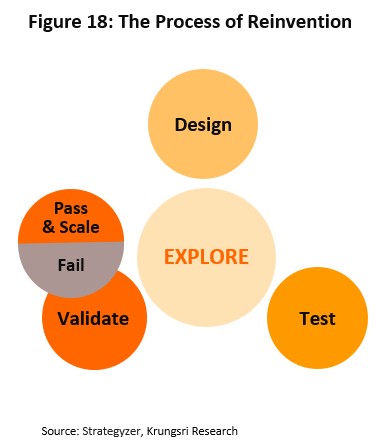

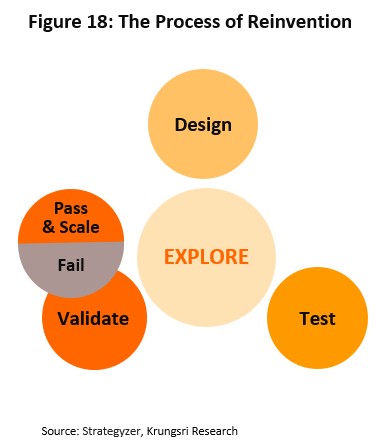

The ‘explore’ process is similar to organizing a hackathon[29] except that the explore process is ongoing. In this procedure, a large number of business development teams compete against one another by researching, refining and presenting a business model, which will then be tested by the risks that it is exposed to and the potential opportunities of the model to grow in the future in order to screen out unsuccessful projects. Successful contestants return for another round of design and testing (Figure 18). This process places a premium on risk taking and trial and error since in reality, given historical data, it can often be extremely difficult to assess the likely success of a novel business idea. When a proposal has passed a sufficient number of rounds of testing, it will be selected for implementation into a real business or the ‘exploit’ phase of the process, which is on the upper right of the Portfolio Map below.

To help the business grow as rapidly as possible, the development of the ‘exploit’ phase follows the general stages of business development, beginning with forecasting and planning based as far as possible on high-quality historical data, laying out an organizational structure that will support the planned business activities through to execution, and then assessing performance to avoid making mistakes. During the exploit phase of the project’s development, it may be the case that returns are somewhat low at the beginning but this is simply the nature of new ventures. In the end, the project has potential to generate healthy and sustainable profits (Figure 19).

In conclusion, at the heart of the ‘reinvention’ stage is the goal of creating a new business model. Although it may not yet be clear what the current market will be for this, it may have the potential to create its own market in the future. Likewise, in developing new business models, innovations should not be valued through the lens of the old model. New models should not be required to meet the needs of old customers and the threshold of return on investment (ROI). Beyond this, spreading investments through many projects will help to increase the chances of hitting on a new model that has sufficiently high potential to disrupt the market.

5. REFORM: Innovation is the key to excellence

“Leaders don’t create growth. Leaders create conditions for growth”

- Strategyzer, the author team of “The Invincible Company”

In order to constantly drive businesses with innovation to build proprietary advantages over competitors, firms need to overhaul all business processes and bring them into alignment so that they all aim at this same goal. If one compares innovation to a tree that needs a sufficient supply of earth, water, light and fertilizer to grow, an organization, in similar, needs to ensure suitable conditions to foster innovation. Osterwalder thus describes three aspects by which the potential to innovate may be judged28/.

- Organizational management: Factors to consider under this heading are whether the management has set aside sufficient time to determine the business’s clear direction, whether the organization’s goals, directions and the logics behind these have been communicated sufficiently, and whether sufficient resources have been allocated for these activities to succeed.

- Organizational structure: Successful companies will set up departments or offices that are responsible for supporting and pushing forward innovation and which are separate from general management duties. For example, Ping An, a huge Chinese insurer, has created the position of Chief Entrepreneur Officer, who is responsible for the future development of the company and who has the power and authority equal to the Chief Executive Office. Departments responsible for innovation will need to cooperate with the core business departments and though need to have processes in place to encourage new thinking about innovation and to urge a willingness to engage in trial and error.

- Organizational culture: One might ask whether the organization has sufficient tools to innovate, whether it can attract talents, whether it can develop the skills of its workforce, and whether it has the processes in place to successfully evaluate the innovations that it carries out.

Krungsri Research view: In crisis lies opportunity

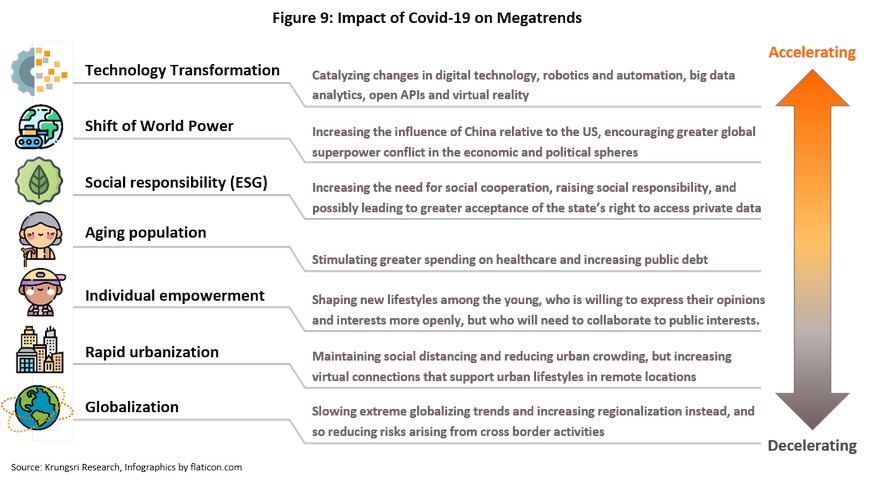

The Covid-19 crisis has triggered huge transformations across many different parts of the economy as well as significantly accelerating the impact of megatrends that were already impacting society and the economy. Many of these changes will in the future solidify into the ‘new normal’, most obviously the surge in the use of technology in daily life. In addition, the crisis has also reminded us about our tremendous exposures to risks, ‘black swan’ events, and uncertainty. Businesses that were in the past classified as ‘engines at risk’ may have suddenly fallen into the ‘at risk’ group as a result of the crisis, including airlines, hotels and other businesses reliant on the tourism industry, and retailers and restaurants that provide older, offline-only services. This dramatic change in the environment illustrates how evaluating an organization’s potential with regard only to the current business environment may well be insufficient to the task in dealing with sudden future changes.

Krungsri Research believes that in the coming period, the key to survival for many businesses will be our adaptability and our ability to develop stronger, more vibrant business models, especially with regard to the value propositions in offering a solution to consumer problem. Simultaneously, organizations will need to look for ways to encourage business innovation and to develop new markets. In some cases, companies will need to leave the environments where they used to compete in new arenas. Indeed, the track record of many companies and the recent experience of Covid-19 show that although new business models may not provide huge returns today, they may nevertheless have the potential to transform industries in the future.

The pandemic is providing an opportunity for businesses to reassess ourselves and to start afresh. For example in the tourism sector, when the crisis finally passes, there may be a very fewer number of players left, which will present an opportunity for companies to pivot to creating business sustainability and immunity, rather than simply continuing to compete with one another on price. Players may also consider raising the role of the domestic market as a way of widening a customer base and so increasing resilience to possible future international shocks. As regards the banking sector, the spread of Covid-19 has affected banks by increasing the fragility of our customers’ finances, although at the same time, it has encouraged a much greater awareness of the need to better manage financial risks and a greater usage of online and mobile banking platforms. This constitutes a major challenge for banks, but it will also open the door to a significant opportunity for the banking sector to overhaul itself, and speedup the digital transformation in aiming for supporting customers to manage their finances and risks in a much more personalized fashion.

Beyond this, post-crisis conditions will encourage organizations to engage in major internal reforms, as well as marking a turning point in business transformation and the implementing of internal processes that support the development of new business models and the provision of new value to consumers. Implementing these new business models will then help businesses surpass our competition, progress towards excellence and insulate ourselves from disruption.

“Ideas are easy. Execution is everything. It takes a team to win.”

- John Doerr, a venture capitalist at Kleiner Perkins and the author of “Measure What Matters”

Endnotes

Adhi, P., Davis, A., Jayakumar, J. & Touse, S. (2020). Reimagining stores for retail’s next normal. McKinsey & Company.

Amarsy, N. (2015). Why some business models are better than others. Strategyzer website.

Asia Aviation Public Company Limited (AAV)’s Annual Report. (2019).

Bank of Thailand. (2020). Bank of Thailand’s 2020-2022 strategic plan: Central bank in a transformative world.

CAPA. (2020). COVID-19. By the end of May, most world airlines will be bankrupt. CAPA Analysis Reports at 17 March 2020.

Christensen, C. (1997). The Innovator's dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business Review Press.

Dahl, J., Giudici, V., Kumar, S., Patwari, V. & Vigo, G. (2020). Lessons from Asian banks on their coronavirus response. McKinsey & Company.

Downes, L. & Nunes, P. (2013). Blockbuster becomes a casualty of big bang disruption. Harvard Business Review.

Grill-Goodman, J. (2020). 10 retailers riding the BOPIS wave. RIS Retail Info System website.

Jaiwat, W. (2020). IATA projects airline industry to incur losses more than THB 2.6 trn this year but cargo businesses continue to grow. BrandInside. Retrieved Jun 15, 2020 from https://brandinside.asia/

Jirath Chenphuengpawn, Patcharapon Leepipatpiboon and Ruja Adisonkanj (2017). 6 Mega trends and the Thai economy. Bank of Thailand.

Klinchuanchun, P. (2020). Housing in BMR. Thailand Industry Outlook 2020-2022. Krungsri Research.

Kuijpers, D., Wintels, S. & Yamakawa, N. (2020). Reimagining food retail in Asia after COVID-19. McKinsey & Company.

Herman, D. (2011). Understanding FoMO. FOMO Fear of Missing Out website

Ma, C., Rogers, J. & Zhou S. (2020). Global economic and financial effects of 21st century pandemics and epidemics. COVID Economic, Vetted and Real-time Papers Issue 5. Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Mission to the Moon Podcast. (2020). Insights on retail business: never be the same again. Mission to the Moon EP.1.

Mission to the Moon Podcast. (2020). Airline Industry and the perfect storms. Mission to the Moon EP.758.

Monetary Policy Report. (Jun 2020). Bank of Thailand.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Etiemble, F. & Smith, A. (2020). The invincible company. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Osterwalder, A. (2005). Business Model Canvas. Retrieved Jun 15, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_Model_Canvas/

Sahota, P. (2014). How brick and mortar guideshops are changing the e-tailer marketplace. Startup Fashion website.

Seric, A., Gorg, H., Mosle, S. & Windisch, M. (2020). Managing COVID-19: How the pandemic disrupts global value chains. United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). World Economic Forum.

Shiller, R. (2019). Narrative economics: How stories go viral & drive major economic events. Princeton University Press.

Sneader, K. & Singhal, S. (2020). The future is not what it used to be: Thoughts on the shape of the next normal. McKinsey & Company.

The Secret Sauce Podcast. (2020). Tassapon Bijleveld Thai AirAsia Talk on the Future of Aviation “I will never do airline business again”. The Secret Sauce EP.229. The Standard.

Williamson, P. & Zeng, M. (2009). Value-for-money strategies for recessionary times. Harvard Business Review.

World Economic Outlook Reports. (June 2020). A Crisis Like No Other, An Uncertain Recovery. International Monetary Fund.

Data of COVID-19 cumulative cases. Europe from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Retrieved from Jul 13, 2020 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases/

Data of COVID-19 cumulative cases. Retrieved Jul 13, 2020 from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?/

Data of COVID-19 vaccine. Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_vaccine/

Data of Thailand’s real GDP. Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC). Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://www.nesdc.go.th/main.php?filename=qgdp_page/

Disease outbreaks. World Health Organization (WHO), Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://www.who.org/

Disease outbreaks. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/

Ebola outbreak. Ebola. Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebola/

H1N1 outbreak. Pandemic H1N1/09 virus. Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandemic_H1N1/09_virus/

MERS outbreak. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_East_respiratory_syndrome/

SARS outbreak. 2002-2004 SARS outbreak. Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2002%E2%80%932004_SARS_outbreak/

Zika outbreaks. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://www.paho.org/en/

Zika outbreaks. 2015–2016 Zika virus epidemic. Retrieved Jun 24, 2020 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015%E2%80%932016_Zika_virus_epidemic/

[1] Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

[2] World Economic Outlook Reports (Jun 2020), International Monetary Fund (IMF)

[3] Monetary Policy Report (June 2020), Bank of Thailand

[4] Data on real GDP is from the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC). Comparisons with past recessions are based on the annual year-on-year contractions (i.e. on the four quarters following the initial crisis), which the 1997 crisis runs from 2Q97 to 1Q98 and the 2008 crisis goes from 4Q08 to 3Q09

[5] Ma, C., Rogers, J. & Zhou S. (2020) with data from the World Health Organization (WHO), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the Wikipedia website.

[6] Data on the number of European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)

[7] From an interview with Soumya Swaminathan, Chief Scientist for the WHO (June 18, 2020), AFP

[8] The Bank of Thailand’s 2020-2022 Strategic Plan 2020-2022: Central Bank in a Transformative World

[9] Kuijpers, D., Wintels, S. & Yamakawa, N. (2020), McKinsey & Company

[10] Williamson, P. & Zeng, M. (2009), Harvard Business Review

[11] Sneader, K. & Singhal, S. (2020), McKinsey & Company

[12] Shiller, R. (2019)

[13] Jirath Chenphuengpawn, Patcharapon Leepipatpiboon and Ruja Adisonkanj (2017)

[14] Herman, D. (2011)

[15] Osterwalder, A. (2005)

[16] From interviews on The Secret Sauce Podcast (2020), Mission to the Moon Podcast (2020) and the 2019 annual financial report of Asia Aviation Public Company Limited (AAV)

[17] Jaiwat, W. (2020) and an analysis of CAPA (2020)

[18] Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. (2010)

[19] From interviews with the Thai hotel business entrepreneurs

[20] Adhi, P., Davis, A., Jayakumar, J. & Touse, S. (2020), McKinsey & Company and Mission to the Moon Podcast (2020)

[21] Dahl, J., Giudici, V., Kumar, S., Patwari, V. & Vigo, G. (2020), McKinsey & Company

[22] Seric, A., Gorg, H., Mosle, S. & Windisch, M. (2020), McKinsey & Company

[23] Klinchuanchun, P. (2020), Krungsri Research

[24] Christensen, C. (1997)

[25] Downes, L. & Nunes, P. (2013), Harvard Business Review

[26] Amarsy, N. (2015)

[27] Retrieved from https://www.pttplc.com/

[28] Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Etiemble, F. & Smith, A. (2020)

[29] Hackathons are events at which teams cooperate and generate ideas as they compete to solve problems posed by the event organizers. Generally, hackathons will last for 2-5 days and entrance to the competition may be restricted to within an organization or it may be open to the public. Teams will often be cross-functional, containing a mix of inventors, designers, marketers, software designers, technologists, graphic designers and scientists.