From Pipeline to Platform: New Wave of Change in Payment Business

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is precipitating enormous changes in the world of business, and financial institutions will not escape these rising challenges. As they become increasingly driven by technology and innovation, payment systems worldwide including in Thailand, will become more and more dependent on electronic payments, and this will drive banks to shift their operations to a ‘platform business model’. Through this period, financial institutions that are major providers of payment services will find themselves in an ever more unstable position, with the foundations of their business being undermined by new players entering the market as suppliers of platform services, and so to preserve competitiveness, banks are being forced to transform their businesses and to shift as rapidly as possible from their older models of business organization to one in which they too are platform businesses.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is leading to global changes in the provision of payment services

“The world is at an inflection point where the effect of these digital technologies will manifest with full force

through automation and making of unprecedented things”

Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee (2014)

These remarks by Professor Erik Brynjolfsson and Dr. Andrew McAfee reflect the fact that the world is at a point of intense change, arguably the most profound and radical in the last 200 years, and that the advances in technology and innovation that we are currently witnessing will lead to profound transformations in all aspects of our lives. This is the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which the World Economic Forum has correctly described as a period of sustained breakthroughs in technology that are progressing at an exponential rate of growth. As these changes wash through it, all areas of the economy will be transformed as the production and supply of goods and services take on a wide range of new forms (Figure 1). In light of these deep transformations, significant opportunities and challenges lie ahead for business.[1]

Financial institutions around the world are now awakening to and preparing to meet the effects of these technological innovations. These are expected to come in two broad forms. (i) Disruptive innovation in payment systems from distributed ledger technology (DLT) will have deep impacts on the structure of the sector. (ii) Non-disruptive innovation will change how parts of the sector work but banks will continue to play a role in settling financial transactions, although at the same time, new players from outside the banking sector will have an increasingly important presence in the market, which they will enter via channels such as mobile payment systems and the introduction of new payment gateways. Of these two, in the coming period, it is non-disruptive innovation and technology that will play an increasingly important role in how payments are made and that will drive a rise in the use of cashless payment systems. For its part, the development of DLT, or Blockchain technologies, will likely take some time to reach the point that distributed ledgers will be able to be used in payment systems in a way that is sufficiently secure and efficient to handle the vast number of large-scale transactions that occur globally every day and which demand high-levels of speed and liquidity. [2]

The storm of change that is building in the financial sector will likely make its impacts first felt on payment systems, which will be the first outpost of the banking system to fall to the advances of FinTech. FinTech players will use payment services to gather data on consumer behavior and then use this to better understand consumer needs and to build other, better targeted financial services. The outcome of competition over the application of non-disruptive payment innovations may therefore be that in the future, the role of banks within the market may be displaced. Given this, understanding the past and likely future changes to the Thai payment system will clearly be of primary importance in helping financial institutions manage the coming changes to the financial system.

Looking back…earlier payment systems

If one looks at the recent history of the Thai financial sector, it appears that global-level changes to the provision of financial systems that have been propelled by technological change and which have in only a few years transformed the provision of payment services have in fact only had a very limited impact on domestic payment systems. This resistance of Thai payments to technology-driven change is reflected in the fact that as of 2017, the value of cash in circulation in Thailand remained at the high level of 11.6% of Thai GDP. The reasons for this are varied but there are four main factors that Influence the rate of uptake of electronic payment services. These are: (i) the level of development of financial systems within a country; (ii) the level of technological development; (iii) the extent of government support; and (iv) the development of new technologies that allow non-bank players to have a greater role in the provision of payment services. Weakness in any of these four areas will tend to hold back the spread of electronic payments and in the case of Thailand, although domestic financial systems are generally well developed, the technological side has lagged behind and is generally at a level that is too low for the majority of consumers to become familiar or comfortable with making non-cash payments. This has been caused by the following.

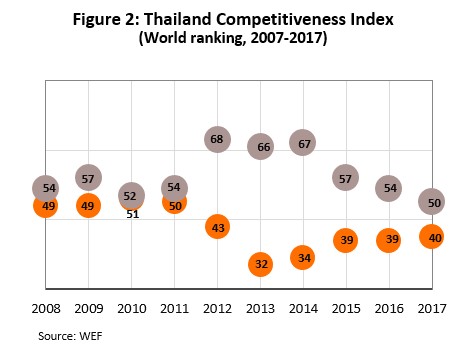

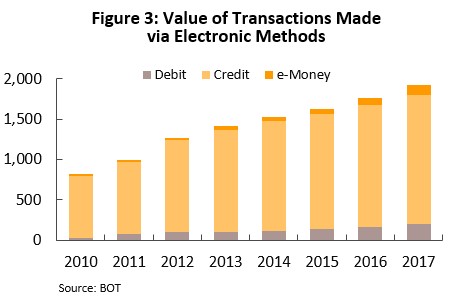

1) Thai banks’ financial systems are not yet supportive of the widespread use of electronic payment systems, and despite the fact that the competitiveness index of the Thai financial sector has risen steadily in recent years (Figure 2) and that figures from 2017 show that a total of 53.0 million debit and credit cards were in use in Thailand, the volume of payments made by debit cards remains extremely low (Figure 3).

- Thai consumers generally prefer to use their debit cards to withdraw cash, rather than to make payments. The majority of debit card use is thus for activities other than making debit payments (e.g. withdrawals from ATMs).

- Consumers are not yet comfortable using debit cards in day-to-day life to make low-value payments. Data on the average value of individual transactions made by debit cards shows that these have in fact risen steadily from THB 76 per card per month in 2010 to THB 285 per card per month in 2017.

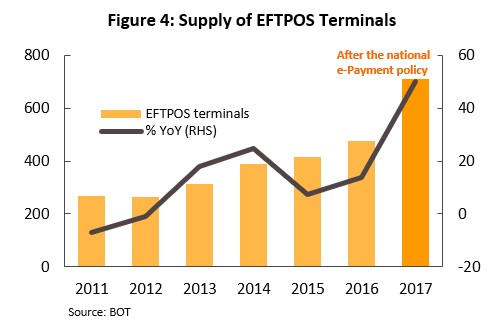

- The number of credit card machines (technically, ‘electronic funds transfer at point of sale’ machines, or EFTPOS machines) ready to take payments from customers is still insufficient when considered in comparison to the number of cards that have been issued. This is particularly the case for the number installed to take payments for goods and services; in 2016, prior to the introduction of the national e-payment policy, there was a total of approximately 477,363 EFTPOS machines in place, though thanks to the policy by 2017, this figure had risen to 711,221 (Figure 4).

2) Within Thailand, the national technological infrastructure and the level of innovation are both currently insufficient to create a situation where consumers are comfortable with the use of technology in daily life. This is because the level of basic digital skills has an important influence on the level of consumers’ ICT adoption and through this, helps to determine both the use of technology in daily life and consumers’ trust in electronic payment systems, and in Thailand, these tend to be low. Evidence for this can be seen in the 2018 WEF ranking of countries for their level of ICT adoption; Thailand was placed 64 out of 140 countries, and the workforce’s digital skills (its computer literacy and basic coding skills) were also ranked 61st. This level of development in ICT is reflected in the fact that Thai competitiveness in technology and innovation has long fallen behind that of its financial sector (Figure 2).

Looking forward…future payments systems

Despite this situation, though, the Thai payment system will increasingly tend to the use of electronic payments under pressure from a number of important factors. Among the latter will be government policy and the entry of non-bank operators to the sector. Prior work by Krungsri Research (available in the report ‘Future Payment Systems’ available from https://www.krungsri.com/bank/getmedia/d479ca9c-43b5-4d92-9b0a-ee8703a7ed47/RI_13_Payment_EN.aspx) shows that in a number of locations, including China, India and South Africa, these factors have played an important role in shortening the stages of development in the transition to a reduction in the volume of cash in circulation. Government policy, which may work through either direct or indirect measures, can help to create a general environment that builds consumer trust in electronic payments, while the emergence of non-bank service providers typically leads to a significant widening of the choices available to consumers for making payments and this too tends to precipitate changes in consumer behavior. The influence of the most important of these factors within the Thai context is summarized below.

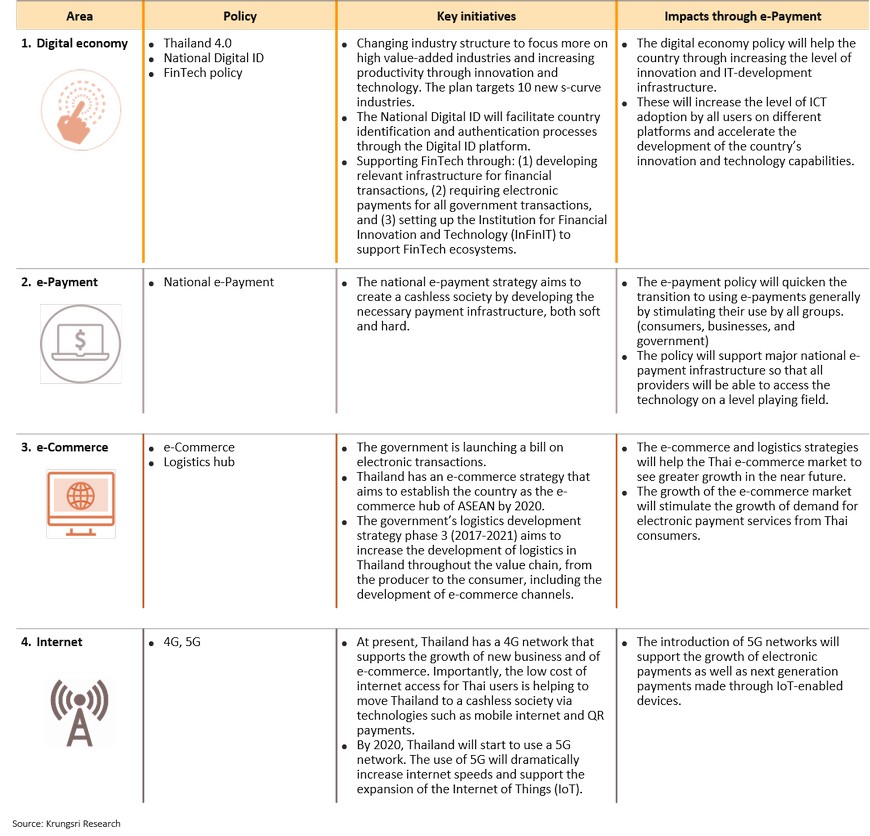

1) A number of policies put in place by the Thai government may increase demand for electronic payment services. These include those related to the digital economy, those that promote the development of electronic payment systems, those that will stimulate the expansion of e-commerce and logistics, and those that aim at developing wireless 4G and 5G networks (Table 1). These are all expected to raise levels of consumer ICT adoption.

- The government’s ‘digital economy’ policy will raise consumer use of technology over the long-term by strengthening the national technology and innovation infrastructure, and shifting economic development to be more focused on supporting high-value industries will help to raise levels of technology and innovation, which are important variables in determining the level of ICT adoption in the general population.

- The development of the infrastructure required for 4G and 5G wireless networks will also help to support the extension of the ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT). Under the IoT, a dramatic increase in the range of connected devices will occur, with these collecting information through sensors and the conglomeration of this will then lead to an explosion in the size and possibilities of ‘big data’. This is expected to then mark a turning point in the development of direct payment systems, i.e. machine to machine payments, and an increase in the volume of automatic payments.

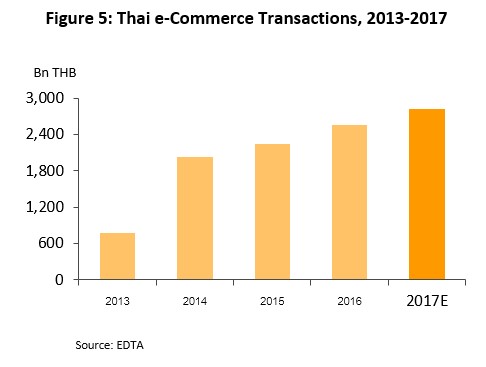

- Consumer acceptance of electronic payment systems is also being lifted by growth in e-commerce, this thanks to direct and indirect government support in the form of efforts to establish Thailand as a hub of ASEAN e-commerce by 2020, progress on the national logistics policy, and the development of electronic payment systems themselves. The effect of these moves will be to help e-commerce to continue to grow from its 2017 value of THB 2.8 trn. (For the years 2014-2017, growth in e-commerce averaged 11.4% YoY.) (Figure 5)

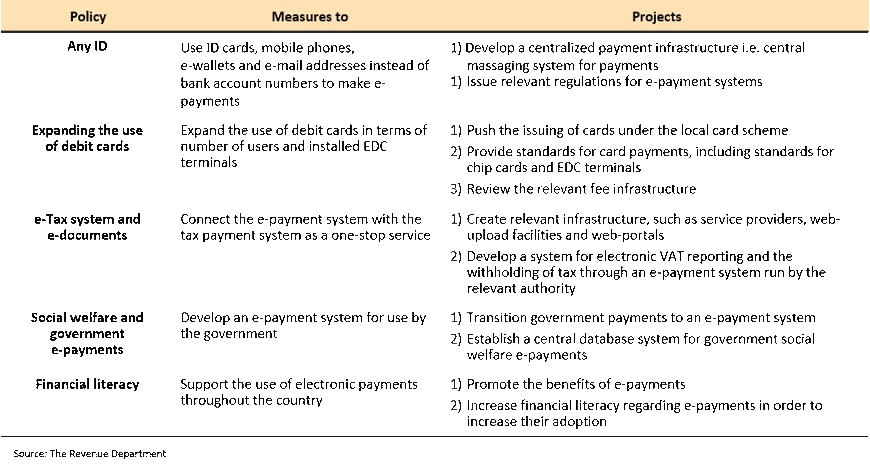

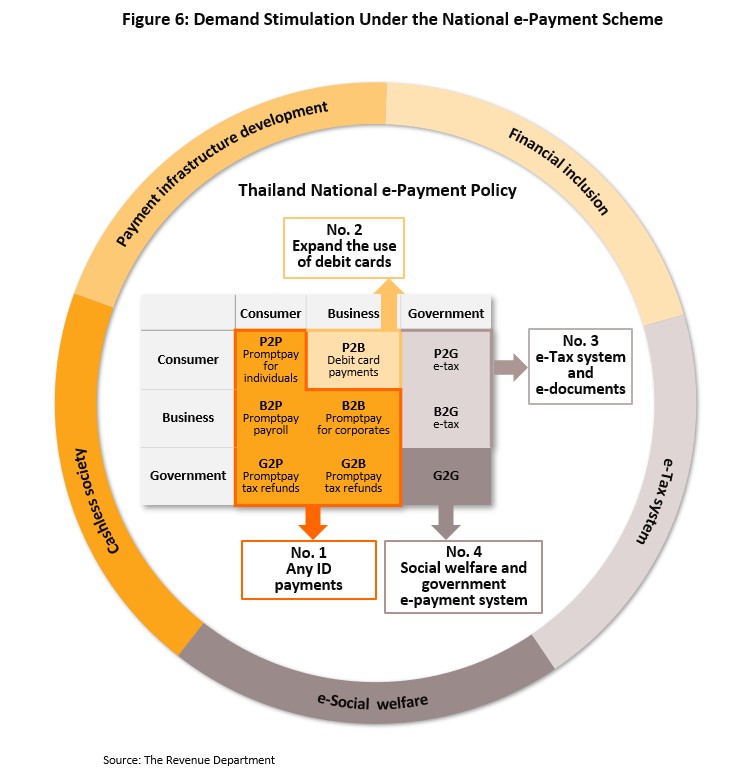

- The development of electronic payment systems for use by the government has raised the quality of the national payment infrastructure and players that previously used different technologies with different associated costs can now compete to provide electronic payment services with lower overall overheads thanks to the existence of central systems that connect service providers. These include: (i) the PromptPay system; (ii) the increased distribution of POS terminals in the provinces and the development of shared POS terminals; (iii) the amendments to the Payment Systems Act to bring payments up to international standards; (iv) the creation of a centralized payment gateway; (v) the setting of standards for QR codes; and (vi) the establishment of a central system for electronic bill presentment and payment (Table 2).

Table 1: Government Policy Facilitating Development of e-Payment Ecosystems

Table 2: National e-Payment Policy

The national e-payment policy encourages the use of debit cards for making payments from the sides of both holders and issuers, and as a result of the policy, the number of debit card machines in use has increased from its earlier total of 474,363 in 2016 to 711,221 in 2017. Notable aspects of the government policy include reducing registration fees for shops and the ‘jaek chok’ initiative, a draw that offers prizes totaling THB 84 m for consumers making payments with debit cards and shops installing debit card POS machines. Through the period during which these promotions were in place, (May 2017-April 2018), the value of debit card transactions increased by 38.3%.

The national e-payment policy (which has run since 2016) has also been an important factor in underpinning the development of electronic payments over the long-term. The policy is helping to encourage electronic payments across the whole of the business value chain, from individual consumers to businesses and the government, through a number of projects, including the ability to make transfers through ‘Any ID’, which at present allows users to transfer money using mobile phone numbers or national identity cards, and plans exist to extend the use of this to include e-wallet numbers, e-mail addresses and cross-bank bill payment. Beyond this, through the issuing of its welfare card for low-income earners, the government is also supporting an increase in the use of debit cards by expanding the extent of contact between financial service providers and the general population, especially in more remote areas (Figure 6). At the same time, commercial banks are steadily replacing ATM cards with ‘chip’ cards(i.e. cards that have a chip in place of the earlier magnetic strip) a process that should be completed by the end of 2019, while they are also developing measures on how to use chip cards and POS machines that will, it is hoped, increase the use of debit cards for making low-value purchases in place of the current tendency to use cash.

2) The increase in the supply of electronic payment services is being driven by non-banks, startups, tech companies and players in the communications sector. FinTech startups are tending to provide payment gateways to connect to payment systems operated by other service providers, offering e-wallet services for the purchase of goods and the payment of utilities, or running payment gateways that make financial transfers through social media channels. Players are also entering the market from other industries by offering e-wallet services, such as the mobile phone operators True, DTAC and AIS, or retailers such as Central. Given their access to a pre-existing customer base, these players will likely enjoy advantages over startups (Figure 7).

3) Consumer behaviors are also tending to support greater use of electronic payments. These include the increasing use of mobile internet, the rising preference for making purchases online and the higher volume of money transferred via mobile phones.

- Data on the use of mobile telephones by the Thai population (from the 2017 ICT Development Index) shows that usage per 100 head of population has increased steadily and is now higher than the global average, and that since 2012, it has also been higher than that of developing nations (Figure 8). In addition, the number of active mobile-broadband subscriptions per 100 people is also higher than the average for developed countries (Figure 9).

- The rising popularity of making online purchases is reflected in the reported rise in the number of e-commerce transactions carried out, which rose by an average of 49.8% YoY between 2014 and 2017 (Figure 5) as greater numbers of Thais came online and online businesses expanded. A comparison of ASEAN countries also showed that in 2016, the per capita value of Thai business to consumer (B2C) e-commerce placed the country third in the region, behind only Singapore and Malaysia (Figure 10).

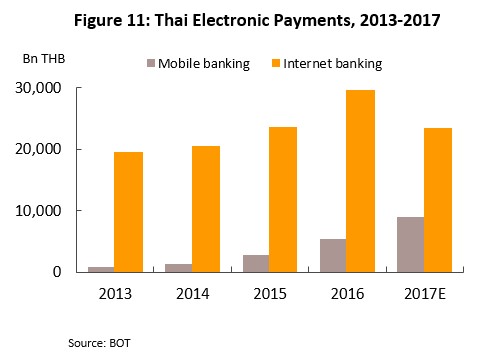

- The value of transfers made by mobile phones has increased sharply over the past 4-5 years and between 2014 and 2017, this jumped at an average rate of 86.5% YoY. Meanwhile, although the value of transfers made via internet banking slipped in 2017, that made by mobile phones continued to rise (Figure 11).

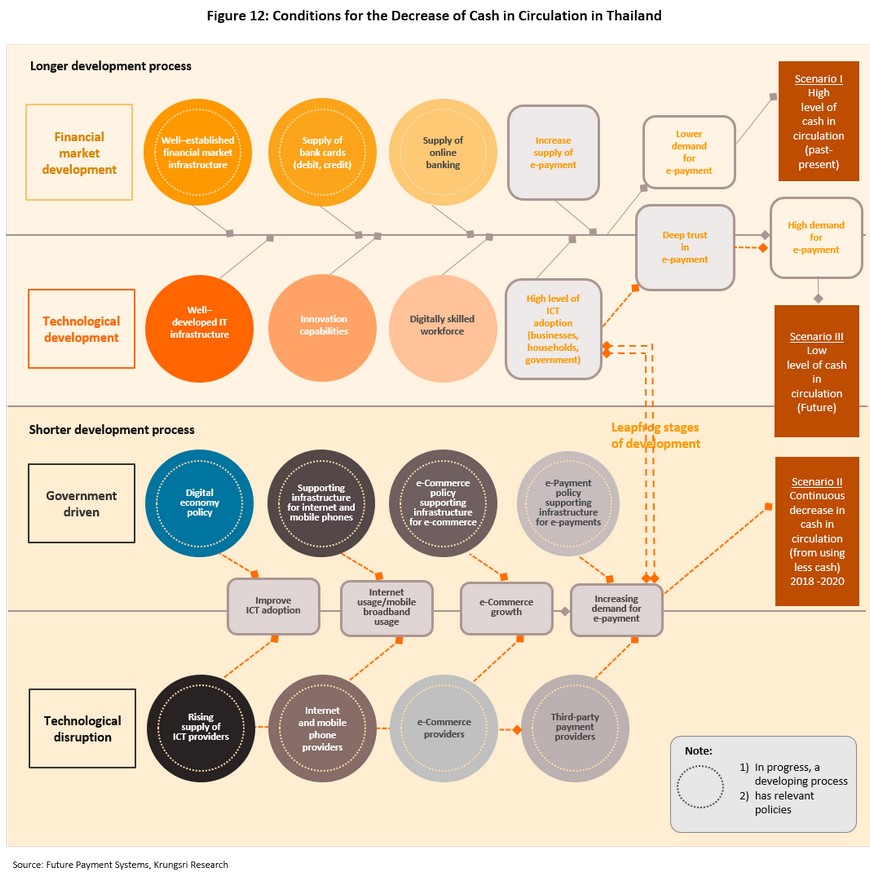

Given this situation, the evaluation by Krungsri Research is that the market for payment systems in Thailand is entering a period of change and that demand for electronic payment options will increase through the next three years, with the consequence that the economy will move to having a lower level of cash in circulation (Figure 12: Scenario II). This process will likely unfold at a faster pace than has been seen in developed economies, with these changes being accelerated by a number of government policies, direct and otherwise, and the increasing role. of non-bank payment service providers within the system. The rising visibility and importance of non-bank payment providers and of e-commerce players is helping to change consumer norms and to speed up the acceptance of electronic payment systems and this could precipitate an increase in the speed of Thailand’s conversion to a low-cash economy as confidence in and demand for cashless electronic payments rises in the coming period, prior to a later fall in demand for cash leading to low level of cash in circulation.(Figure 12: Scenario III).

Within this new environment, competition between providers of electronic payment services is certain to stiffen in the future. Because Thai financial institutions are on a well-developed footing, they will have a more extended period of time during which to adjust themselves to changing market conditions and to maintain their central role as market leaders in the provision of these services, but in the final analysis, only those players that understand the changing business landscape and that grasp the transformations opened up by disruptive technology will be able to maintain and extend their competitiveness.

New payment systems in a changing world

Overall, the sector will be increasingly marked by the provision of electronic payment systems and this realization is driving Thai financial institutions to begin to respond to the changing environment in which they find themselves by developing new electronic payment systems of their own. These have taken several different forms but most financial institutions have established partnerships with FinTech startups that have the ability to develop new payment systems. At the same time, telcos and tech companies have also begun to rapidly expand their operations and to grow their customer base through the introduction of mobile applications.

The rapid growth in the use of mobile-based payment systems that is being seen is transforming the nature of competition in the Thai financial sector, which has moved from its earlier form to one based on the new ‘platform economy’, a development that has the potential to pose major challenges to all businesses. An understanding of this new world and of the drivers of platform businesses will therefore be important for predicting how future competition in the provision of payment services will play out.

1) The difference between ‘pipeline’ and ‘platform’ businesses

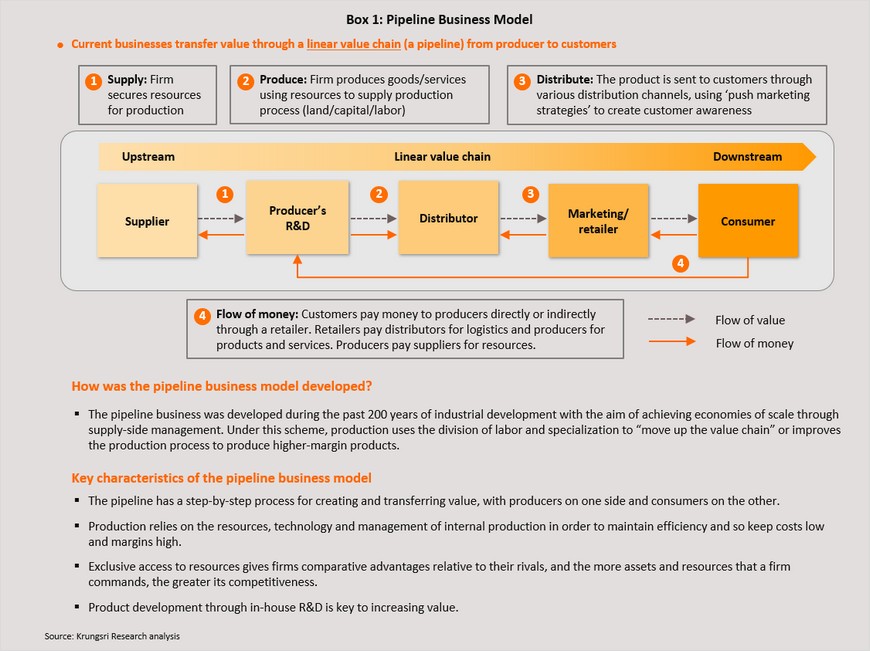

Through the twentieth century, the majority of businesses had their roots in the First Industrial Revolution and so they were built on the model of the ‘pipeline business’, under which competitiveness was increased by building supply-side economies of scale. That is, manufacturing efficiencies were maximized to reduce marginal production costs by producing in bulk and because of this, the larger the business, the greater its cost advantage and the more difficult it was for other players to compete against it.

However, the wave of technological disruption that has broken on the first decades of the twenty-first century has changed the business environment and placed technology in a crucially important role within organizational activity. Among these changes, one that has had important impacts on manufacturing is the emergence of the ‘platform economy’. Under this model, building networks that connect those within a platform creates demand-side economies of scale. These economies of scale stem from building network externalities such that demand for goods and services grows with the increasing number of users or consumers itself, and the larger the network, the larger the value that is added by the platform. These networks then become themselves the barriers that hinder or prevent new players from entering the market and competing against existing operators.

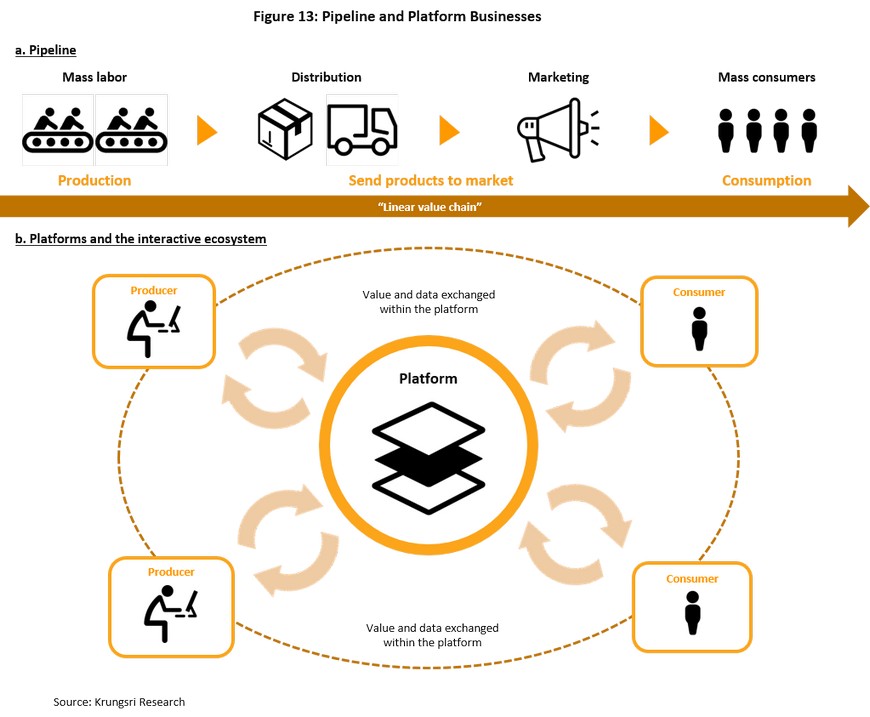

The most important differences between pipeline and platform business models lie in the different ways in which value creation occurs within the production chain. Under the pipeline model, there is a linear value chain, which runs from the creation or instantiation of a good or service, by which value is created, through to the end of the production chain, which terminates with the consumer. In the case of platform businesses, value is created in a more complex process involving a value matrix because in this case, value creation may come from producers and consumers, whose roles may flip from one to the other simultaneously. Those interacting on the platform may do so in a wide number of ways, though the exact relationship between a user and a platform will depend on the services provided in that particular instance. Overall, though, platforms will generate value in multiple directions simultaneously, as opposed to the unidirectional value creation of pipelines (Figure 13).

Under production based on earlier pipeline models, it is therefore possible to add value by production at all stages of the value chain, from upstream through to downstream segments and so the basic principle for building competitiveness is to maximize efficiency throughout the value chain by: (i) taking possession of the resources that represent major factors of production and to which competitors lack access, and so blocking their entry to the market; (ii) reducing marginal costs by maximizing economies of scale and maximizing production; and (iii) increasing the efficiency of production throughout the production chain, an important means of lowering manufacturing costs and so of increasing profits. In this way, the whole of the production value chain is under the control of the manufacturer and should production need to be increased to raise profits, this can be achieved through increasing the throughput of factors of production or by using technology to increase output (Box 1).

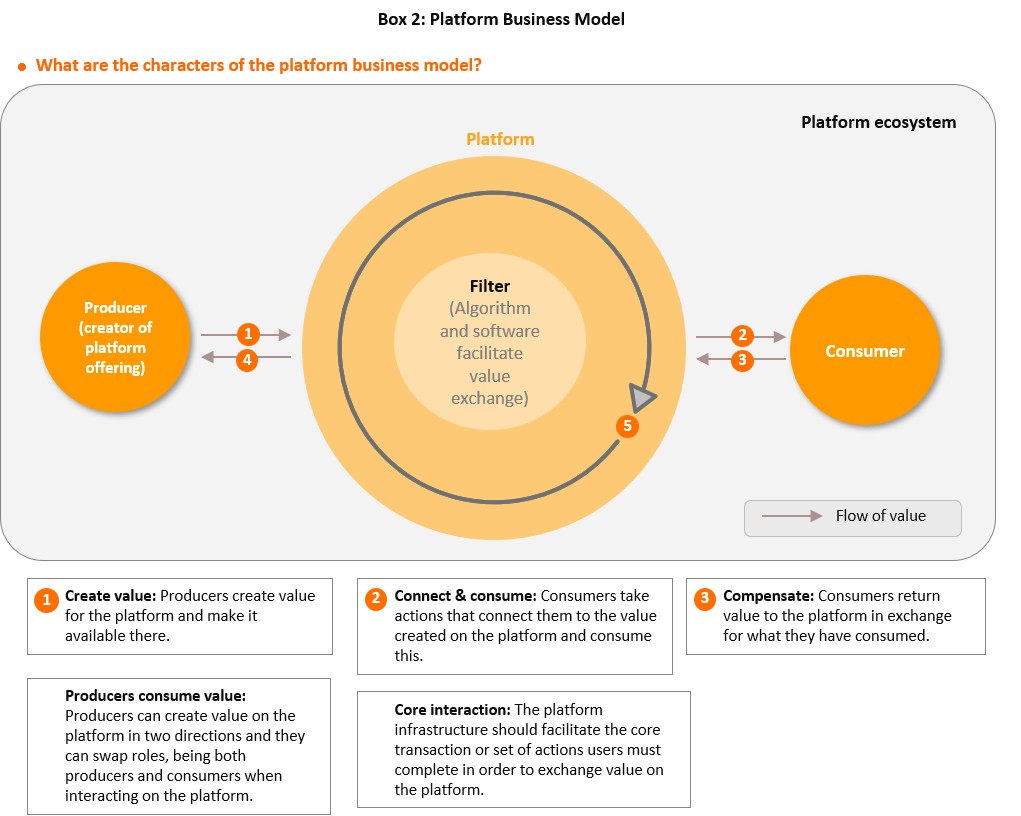

Production or interaction that occurs under the platform model is fundamentally different to this. Within the ecosystem of platform-based economies, the main organizing principle of production is to maintain and support core interactions, or the activities that are the primary goal of that particular platform. These activities will lead to the exchange of ‘value units’ between users of the platform, whether these exchanges are between producers and consumers or between consumers themselves, though in either case, the aim of the platform remains the same, that is to facilitate the smooth exchange of value units. This then encourages those who are on the platform to engage in ‘core interactions’ with one another, as well as helping to pair producers and consumers in such a way as to maximize their satisfaction by ensuring that each side of the transaction feels that it has benefited from their platform-mediated interaction

Platform business models can be sub-divided into the four major groups of: (i) transactional platforms, which act as middlemen to facilitate business transactions between users, (e.g. PayPal and Uber); (ii) innovation platforms, which operate as the foundations for other platforms (e.g. Microsoft, which largely provides technology to support the services available on other platforms); (iii) integrated platforms, which both act as middlemen for business transactions and offer services associated with innovation platforms (e.g. Apple, Facebook and Alibaba); and (iv) investment platforms, which provide portfolio services for investors (Box 2).

How was the platform business model developed?

- The platform is a new business model that uses technology to connect people, organizations, and resources in an interactive ecosystem in which an amazing amount of value can be created and exchanged. (Platform Revolution, 2016) Digital technology has empowered platforms to grow exponentially and to reduce barriers to users, who can connect and participate on the platform.

Key characteristics of the platform business model

- The platform provides consumers and producers with tools to help them to easily connect and to encourage more valuable exchanges through the platform with best matches between users.

- The ‘network effect’ is the main source of value creation and comparative advantage for platform businesses. The power of platforms stems from the fact that an increase in the number of users on a platform will attract greater numbers to it.

- Platforms do not function like the linear assembly lines by which pipeline businesses create value. Platforms rely on humans to drive the exchange, so these are constantly changing and evolving rather than being static processes that rely on exact inputs and outputs for production.

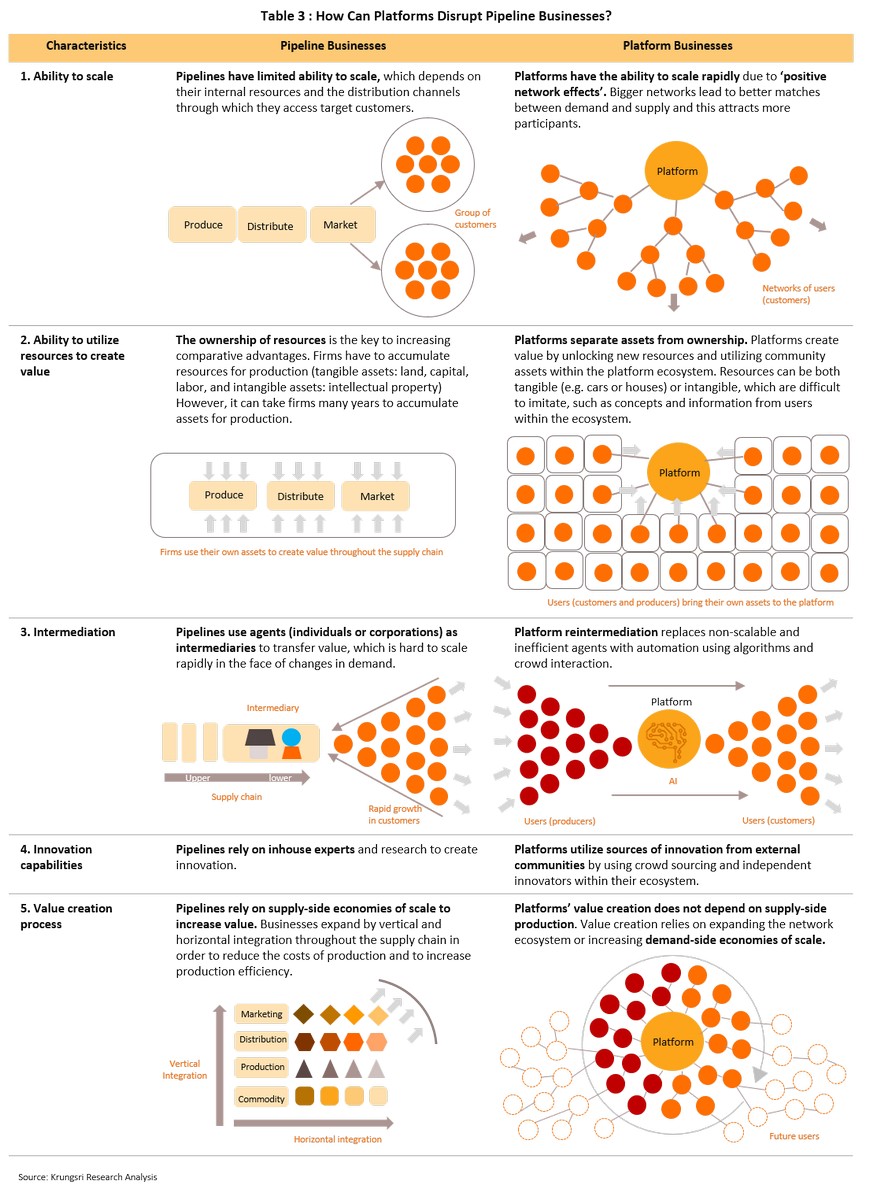

There is a widespread belief that whenever a pipeline operation is forced into competition with a platform-based one, the platform business will inevitably win, and indeed, if one looks at those recently successful businesses that have very rapidly become world-leaders, one can see that the majority of them are indeed platform-based operations. This imbalance between the two types of business is grounded in the differences between pipeline- and platform-based production, which rests on the ability of platform businesses to overcome earlier limitations on production in a number of different ways (Table 3).

- In terms of their abilities to scale, platform-based operations have an advantage over pipeline businesses because the former are able to expand their customer bases and so secure growth through the so-called ‘network effect’, or the connection between purchasers that is created through their relationship within the network and which causes them to join the platform. Parker, Alstyne and Choudary (2016) have compared the network effect to telephone ownership and usage. In the case of the telephone, owning a single unit is valueless to its owner but when this is connected to a second telephone, its value grows, and the more telephones are connected and used, the more the value of telephone ownership is multiplied, and the more incentive there is to join the platform. Because of the way in which the network effect works, its emergence will tend to cause users who come onto a platform to have a more extended long-term relationship with it, rather than doing so only temporarily, while the network effect also makes it possible to build a huge and geographically dispersed user base in only a short period of time. This has been the case with, for example, Facebook, which has attracted users on the basis that a large number of their friends are already consumers of the platform and so it has an implicit appeal to those that are outside it. By contrast, for businesses built on earlier models, gaining access to customers may be limited by physical or infrastructure factors, such as the need to use older types of advertising or the need to be in a particular location in order to distribute goods and services, and this thus puts them at a disadvantage relative to businesses that can exploit network effects to grow their customer base.

- As regards the capacity of businesses to utilize resources to create value, platforms can circumvent many of the earlier limitations on business expansion. In the past, expansion typically relied on capital accumulation, which is normally a lengthy process, though one in which earlier pipeline-based businesses had an advantage, because these businesses control a wide range of factors of production and so can naturally lower their marginal costs. Platform businesses, on the other hand, can use resources for production that originate from users within the platform ecosystem of producers and consumers, rather than relying on the producer’s having exclusive access to its own factors. Platforms may accomplish this by building business models based on the sharing economy, under which resources or factors of production may be exploited with high levels of efficiency, as is the case with the rentals service Airbnb, where those letting out properties may also be the platform’s customers. Given the fact that platforms may not have to concern themselves with either managing resources or accumulating capital (restrictions that for pipeline businesses may in the past have required even large operators to wait years to secure enough financing to fund expansion), it can be possible for them to grow very rapidly without experiencing any supply-side limitations.

- Platforms also have advantages in terms of their ability to act as intermediaries between producers and consumers (i.e. intermediation), or they can connect consumers directly, without the presence of an intermediary, which may otherwise not be put in place sufficiently quickly to meet increases in demand. Platforms also gain from being able to collect and use big data that is gathered from interactions between consumers and producers on the platform and then algorithmically analyze this to rapidly and efficiently uncover consumer needs in real time.

- In the past, an organization’s capacity for innovation and its ability to develop new technologies and applications would usually depend on research and development activities carried out within that particular organization itself, but platforms may be able to access the expertise of users throughout the entire platform ecosystem.

- In terms of the value creation process, traditional businesses will typically engage in vertical integration to expand the value chain, which may involve either backward or forward integration, moving respectively upstream or downstream. Alternatively, businesses may look to horizontal integration as a route for expansion, increasing the range of their offerings at particular points of the value chain. These moves create supply-side economies of scale and examples would include expanding operations to produce inputs that were previously bought from outside suppliers, or buying a logistics operator to reduce transportation costs. By contrast, in the case of platform businesses, value can be created by exploiting data on interactions within the platform to build growth in demand.

Industries that are liable to be disrupted by platform-based production tend to fall into the following groups: (i) information intensive industries; (ii) industries that are based on the existence of middlemen but which are at a disadvantage in terms of their growth potential when compared to the rapid demand growth caused by modern technological advances; (iii) highly fragmented industries; and (iv) industries based on asymmetric information. Businesses that are closely regulated may encounter disruption over a longer timescale, such as those in the financial sector, or those that are highly dependent on the use of resources, for example mining and other extractive industries. However, the development of new platforms is eroding the dividing line between different industries and making competition between players from different sectors of the economy easier, and while the finance sector is heavily regulated, it is also an information intensive industry and so the sector faces the possibility of operators being displaced by platform businesses, a situation that in fact could easily come about. For finance, the most threatening competitors are therefore businesses that have access to big data on their customers, and this is something that is typical of platform-based operators.

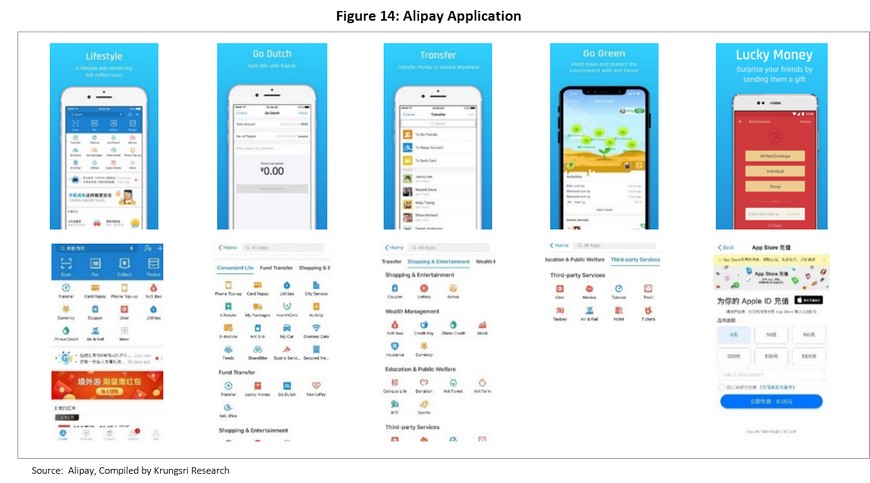

2) Lesson learn from Alipay: A Payment Platform that has achieved global success

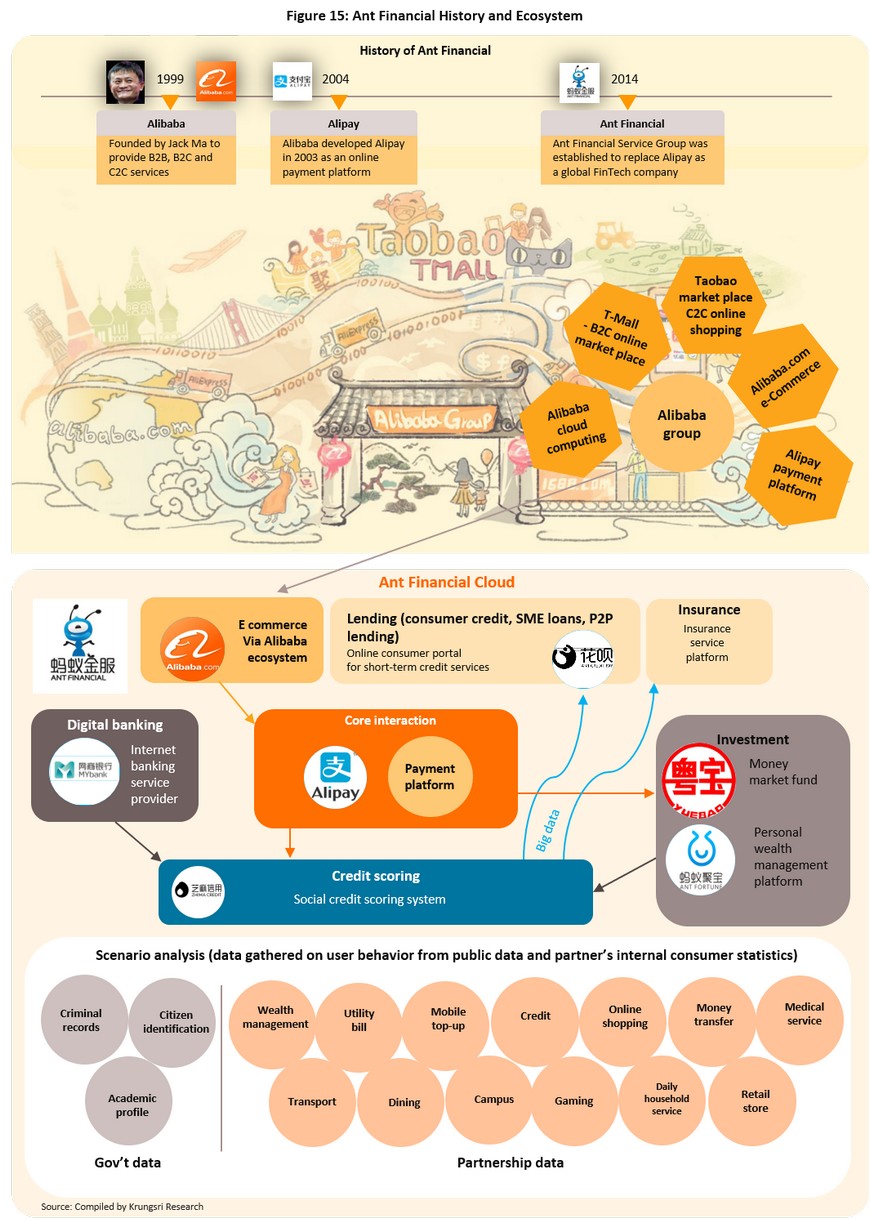

Alipay is an example of a platform-based business that has reached a global level of success, in its case by entering the Chinese finance sector. The company is operated by Ant Financial, a FinTech company that separated from Alibaba in order to offer financial services directly (Figure 14) and is categorized as an innovative platform. The company has an active user base of 450 million people and having beaten Chinese commercial banks to the prize of market dominance, has established itself as the market leader in electronic payment services in China. Ant Financial has expanded the range of financial services that it offers through its platform, and these now include Yu’e Bao, a money market fund, and MYBank, a digital-only bank. The company also operates a related platform that supports its financial operations, this being Zhima Credit, a credit scoring agency. The success of Ant Financial is attributable to two main sets of factors, these being on respectively the demand and supply sides of the business.

Demand side factors

Ant Financial has been able to fill a gap in the market in China very effectively. Before Alipay came on the scene, Chinese payment systems were weak and underdeveloped and they lay outside the reach of much of the (especially rural) population, in addition to neglecting the needs of SMEs. In this environment, it was possible for non-banks such as Alipay to offer very competitive electronic payment services and to move into and occupy a commanding position within this market in a very short period of time. This compares markedly with the situation in developed economies, where traditional banks have long offered well-established payment systems and so in these economies, non-banks typically develop alongside traditional banks, supplementing rather than replacing them. In addition, the rapid expansion of internet access also helped to underwrite Alipay’s position; the number of Chinese internet users grew from 564 million in 2012 to 772 million in 2017 (growth of 36.9%) and this fed additional demand for consumer-friendly electronic payment systems. More broadly, before Alipay began offering its services, Chinese consumers lacked confidence in the existing payment networks because of the inefficient payment infrastructure and weak consumer protection regulations. In light of this, Alipay was able to overcome these limitations and in the process transform the market by offering escrow services. By ensuring that buyers and sellers were both protected, it thus rapidly built confidence in electronic payment services and assured its own success.

Supply-side factors

The strategies for developing the Alipay platform services that Ant Financial initiated were enormously successful and led to a very rapid expansion in the uptake of its services. A number of factors helped to support its dramatic rates of growth (Figure 15).

- The Alibaba empire draws considerable strength from its ability to connect the sizeable customer bases of businesses within its e-commerce network, including T-Mall (B2C), Taobao (C2C) and Alibaba.com.

- The development of the ‘Ant Financial Cloud’ computing system enables the company to evaluate a vast quantity of information in a very short time, and this has helped to increase the efficiency of the Alipay platform in several ways. (i) IT costs have fallen dramatically and the per-transaction cost is now only RMB 0.1. By operating within the cloud, the company has been able to replace traditional database servers with clusters of low-cost personal computers and if they need to expand capacity to handle a greater volume of transactions, this can be done simply by adding more PCs. This has slashed Alipay’s hardware costs, while the company is still able to operate its servers with a high level of efficiency. (ii) Restrictions on managing real-time information flows have been reduced and this has led to millisecond-level risk prevention. By using cloud-based services, management of daily transfers is more efficient and the number of transactions made has risen to tens of billions per day. With this infrastructure, the core interaction of the platform (payments and transfers) can proceed without interruption, and Alipay has in fact set the world record for the greatest number of transactions evaluated and settled per second. This reached 120,000 on ‘Singles Day’ 2016, celebrated in China every year on November 11.

- Ant Financial has also established a credit profiling agency. In 2015, the Chinese government gave permission to Zhima Credit, a platform that operates as a subsidiary of Ant Financial, to offer credit rating services under which the credit worthiness of Chinese citizens is assessed on a scale from 350 to 950 points. In making this assessment, data are gathered and analyzed in five categories. (i) Credit history includes citizens’ loan repayments, credit card debt, utilities payments, and so on. (ii) Behavior and preferences deals with consumers’ online behavior, such as frequency of use and history of purchases of goods and services. (iii) Fulfillment capacity refers to an individual’s ability to fulfill his or her obligations, which is assessed through an evaluation of purchases and possessions, social security payments, payments for property and cars, purchases of financial products from the parent platform, and bank deposits. (iv) Personal characteristics include factors such as address, telephone number, level of education and employment status. Data may come from other platforms, so for example, it is possible to use a LinkedIn profile to join Alipay and this data will then be used in the evaluation. (v) Interpersonal relationships are evaluated through the individual’s interactions on social network platforms. Data are gathered in these five different areas from a wide range of sources, including government databases, databases operated by associated or cooperating companies, and directly from within the agency’s own platform. Government databases will yield data on a user’s criminal history, citizen identification information and educational history, while partnering companies and the platform itself will provide information on behavior and preferences with that individual’s consent. The platform also cooperates with retailers to encourage individuals to improve their credit scores in return for benefits from participating outlets. These include being able to book hotel rooms without making a deposit, borrowing umbrellas and having access to mobile phone charging facilities in convenience stores that cooperate with Alipay.

- Developing scenario-driven analyses is a foundational building block in constructing FinTech offerings. This strategy lies at the root of Alipay’s success in China, which was built on rolling out and testing a range of FinTech products in order to attract a large body of users to the platform and which then formed the backbone of the company offerings. This helped to create consumer product awareness with regard to Alipay and from this, to the adoption of its technology, which then fed back into greater incentives to the consumer to enter the platform. Key to developing these scenarios is being able to build financial products that respond to the needs of consumers that arise in daily life and this in turn comes from answering the most important question: “How will this financial innovation succeed in different circumstances?” Ant Financial thus developed its offerings via its platform by building thirteen different consumption scenarios that consumers would encounter in their day-to-day life. These fall under the headings of: (i) dining, (ii) gaming (iii) online shopping, (iv) transportation; (v) adding credit to mobile phones; (vi) making credit card purchases; (vii) transferring money; making gifts/’red pocket’; (viii) paying for regular household services; (ix) making purchases offline in retail stores; (x) paying for medical services; (xi) paying for education; (xii) using financial services; (xiii) payment for public welfare and The number of users of the platform who operated under more than four scenarios jumped from 17% in 2013 to 40% in 2015 and through these operations, Ant Financial has been able to build a very large database of users and transactions and then to use this to gain a deep understanding of consumer behavior. An example of a scenario that met considerable success is the 11th November Singles Day celebration, which Alibaba developed into a global shopping festival in 2018. Over 200,000 bricks-and-mortar retailers joined in the festival, with these coming from both China and other countries. Six countries that Lazada operates in (Alibaba holds stock in Lazada) joined, these being Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam.

- The platform has been able to build core interactions that are simple to navigate, convenient and secure by facilitating the easy and smooth processing of payments. In pursuit of this, Ant Financial has put considerable effort into designing its risk management system, while also emphasizing data privacy and related areas, such as having sound data security standards by ensuring that its network of over 2,000 computers is continuously evaluated and assessed for risk by 1,500 personnel, or over 20% of the total workforce. In addition, the risk management system is based on the latest technology and is able to process big data in real time with a high level of efficiency.

- Value creation also occurs through peripheral interactions within the platform that arise through the use of other financial services. These include arranging insurance and loans through Ant Credit Pay, a short-term credit service, and investing via Yu’e Bao, a money market fund, and Ant Fortune, a platform for managing personal investments and securities. The platform connects to electronic banking services provided by MYBank, an internet banking service provider that operates on its ‘3-1-0’ principle. The ‘3’ refers to the registration process, which takes at most 3 minutes, the ‘1’ to the decision to release funds, which takes no more than 1minute, and the ‘0’ is a reference to the zero human intervention in the entire procedure. Decisions are instead made to approve or reject loan applications on the basis of an automated evaluation of the individual’s credit score, a process that has the advantage of allowing consumers to access credit without the traditional lengthy and complicated application procedure or its associated high costs.

- The potential of untapped markets has also been recognized and is seen in the moves to develop strategies to extend financial services to those who are at present excluded from the financial sector due to their uncertain incomes or work in the informal economy, a group that includes many farmers. Important here is the rural strategy that Ant Financial has established with Alibaba to bring rural populations within the reach of the Alibaba platform through the Rural Taobao development. The aim of this is to help rural communities access modern, innovative technology by a five-part strategy of (i) one village center, (ii) one dedicated network cable, (iii) one computer, (iv) one large screen, and (v) one group of trained technicians. It is hoped that this will help those in rural areas engage in online business transactions to buy and to sell as well as providing a ‘cultural service center’ for each village.

This would then increase the volume of electronic financial transactions that occur in areas where the local population traditionally prefers to use cash, as well as allowing people in these communities to gain access to loans and other facilities such as making internet money transfers and themselves receiving transfers and payments. Ant Financial aims to establish 100,000 of these centers across the country over the next 3-5 years.

Conclusion: Financial institutions are entering a period when they will face significant challenges and rising competition from platform-based businesses

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is ushering in a period during which financial institutions will have to overcome intense challenges. Within this broad set of changes, the accompanying spread of technology and innovation-driven payment systems is pushing countries around the world, including Thailand, into an era of upheaval, one in which electronic payment systems will become considerably more widespread. In the face of these changes, financial institutions will have to adapt their operations in two regards. Firstly, they will have to deal with increased competition from non-bank providers of payment services and secondly, they will have to manage the difficulties involved in transitioning to a platform business model. At the same time, the effect of the challenges mounted on financial institutions by new players, almost all of which have built their businesses on a platform model, will be to weaken and erode the advantages that older banks and financial institutions previously enjoyed in virtue of their central position in the provision of payment services. To maintain competitiveness as providers of payment services, financial institutions will need to understand the fundamental changes that are working their way through the economic system, and then to apply the lessons learned by world-leading businesses in competing as platform operators to their own situation as rapidly as possible.

References

Alstyne, M. W. V., Parker, G.G., Parker, G.G., (2016). Pipelines, Platforms, and the New Rules of Strategy. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from

Chen, L. (2016). From Fintech to Finlife: the Case of FinTech Development in China. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17538963.2016.1215057

Evan, C. P., Gawer, A. (2016). The Rise of the Platform Enterprise: A Global Survey. https://www.thecge.net/app/uploads/2016/01/PDF-WEB-Platform-Survey_01_12.pdf

Lozic, J., Marin, Milkovi, M., Lozic, I. (2017) Economics of Platforms and Changes in Management Paradigms: Transformation of Production System from Linear to Circular Model. Retrieved from

Parker, G.G., Alstyne, M. W. V., & Choudary, S. P. (2016). Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets are Transforming the Economy-and How to Make Them Work for You. New York, NY: Norton & Company, Inc. Schwab, K. (2016). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Retrieved from https://luminariaz.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-2016-21.pdf

Thanadhidhasuwanna, T. (2018). Future Payment Systems. Retrieved from https://www.krungsri.com/bank/getmedia/d479ca9c-43b5-4d92-9b0a-ee8703a7ed47/RI_13_Payment_EN.aspx

World Economic Forum (2016). Beyond FinTech: A Pragmatic Assessment of Disruptive Potential in Financial Services. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Beyond_Fintech_-_A_Pragmatic_Assessment_of_Disruptive_Potential_in_Financial_Services.pdf

Zhu, F., Zhang, Y., Palepu, G. K., Woo, K. A., Dai, H. N. (2018). Ant Financial (A). Harvard Business School Case 617-060. Retrieved from https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=52493

[1] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/

[2] https://www.krungsri.com/bank/getmedia/d479ca9c-43b5-4d92-9b0a-ee8703a7ed47/RI_13_Payment_EN.aspx

.jpg?width=100&height=100&ext=.jpg)