As Thailand heads into summer, the country faces the possibility of having to endure harsh drought conditions again. And it could be more severe than in 2016. The weak El Niño conditions in 2018 was evident in the extended dry season and below-average rainfall in 2019, which has reduced the total volume of water available across the country. Moving into 2020, the critically-low levels imply risk of water shortage in many areas. The effects will be felt not just within the agriculture industry but also in the industrial sector. In the agricultural sector, crops that are sensitive to drought will be most affected over the next few months, notably off-season rice and cassava. But the drought will also be felt throughout entire manufacturing supply chains. The impact may be more severe for downstream industries than upstream producers. The drought in 2020 is expected to cost the country THB46bn, or 0.27% of GDP.

Thailand needs to brace for another drought in 2020

There are increasingly clear indicators that Thailand would face another drought in 2020 due to climate change. The signs have been visible since 2019.

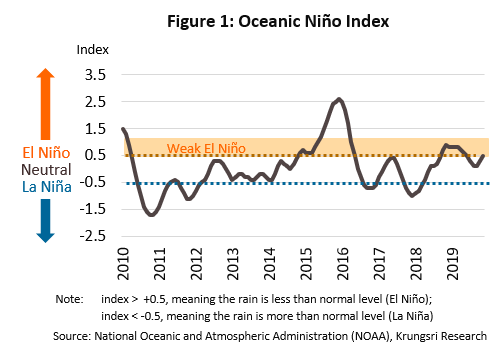

1. The Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), which measures sea surface temperatures, transitioned to a weak El Niño[1] in October 2018, which continued through to June 2019. In these conditions, rainfall typically drop, especially in Thailand. As a result, total rainfall was 10% below average (Figure 1).

2. T

he 2019 dry season was extended. Although the country officially entered the 2019 rainy season on May 20, there was an extended dry spell from the end of June to the middle of July, which shortened the period available to store water.

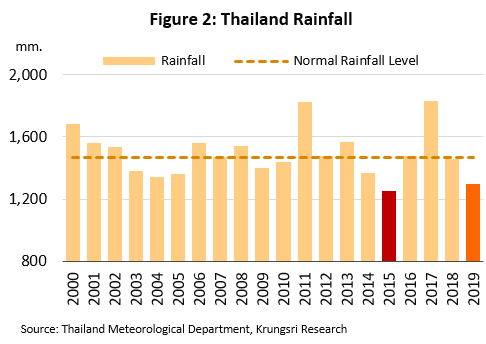

3. Total rainfall throughout 2019 rainy season was 5-10% below average[2]. Rainfall averaged 1,298 mm for the year, close to the 1,251 mm recorded in 2015 (the precursor to the 2016 drought) (Figure 2). This means the national water supply is at a critical level.

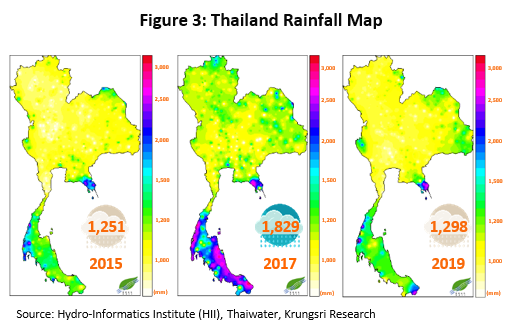

4. A large fraction of rainfall in the country fell outside watersheds of reservoirs and dams in 2019 (Figure 3). Total rainfall in these areas were comparable to 2015.

5. Volume of water available from natural sources has also dropped, especially in the Mekong River. The construction of a large number of dams by members of the Mekong River Commission[3] has seriously reduced river flow.

Critical water levels underlines the need to deal with possibly acute drought in Thailand

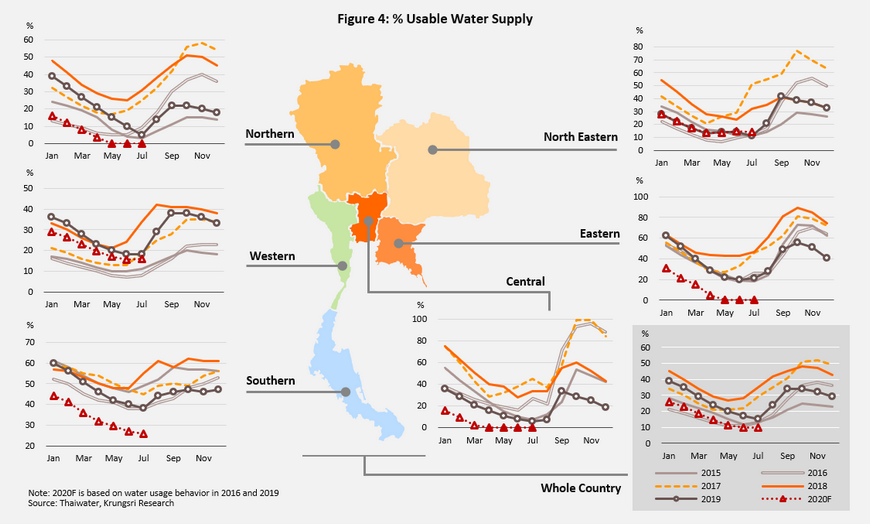

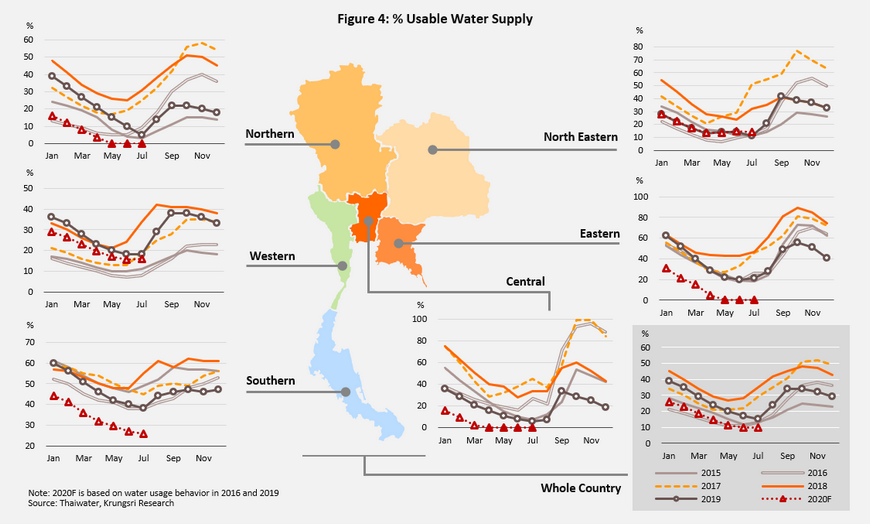

At the end of 2019, there was a total of 44.28 billion cu.m. of water stored in reservoirs across the country. This represented 62% of storage capacity, close to the situation in 2015 with 39.75 billion cu.m. of water or 56% of capacity. But the more important figure is the volume of useable water in reservoirs. At end-2019, this was critically-low at only 29% of capacity, close to 2015 level of 23% (Figure 4). The water in storage and that will be available for use must now be managed to meet four different sources of demand, by order of importance: (i) direct consumption and supply to municipal water systems, (ii) maintenance of environmental systems, for example to prevent saltwater intrusion[4], distribute waste water, or preserve riverine ecosystems, (iii) farming activity (in particular to irrigate dry season crops between November 2019 and April 2020), and (iv) industrial activities.

Water shortage in 2020 could be worse than experienced during 2016 drought

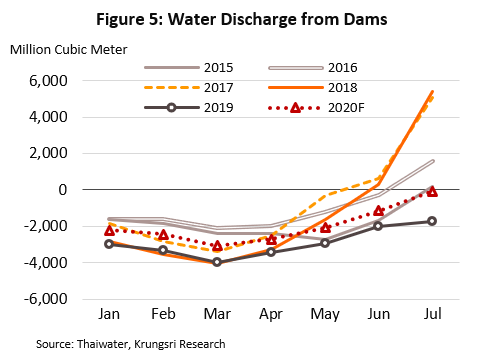

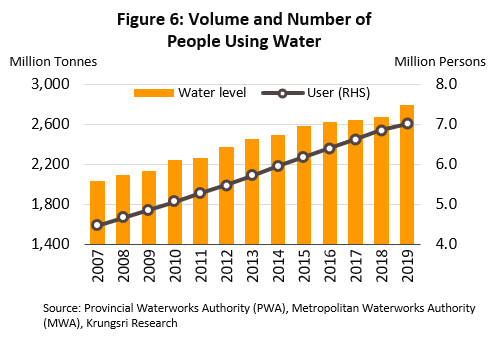

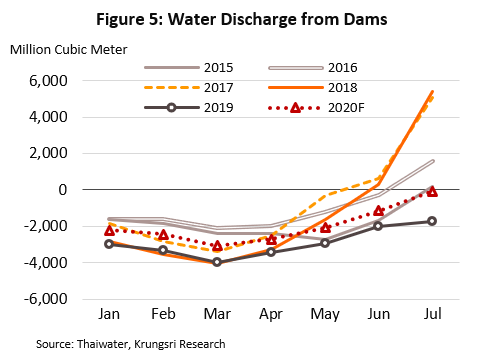

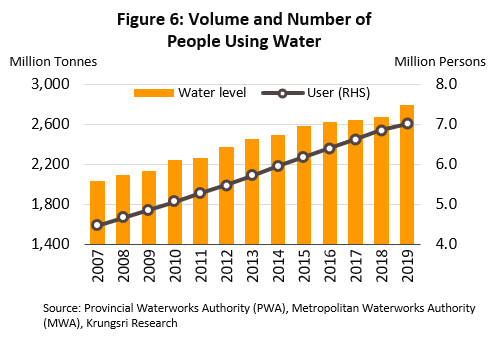

In 2019, an average of 3.0-4.0 billion cu.m. of water was released from reservoirs each month, significantly higher than the monthly average of 1.6-2.4 billion cu.m. released in 2015 (Figure 5). The difference is explained by steady and relentless growth in demand every year for both direct consumption and industrial activities. Data from the Metropolitan Waterworks Authority and from the Provincial Waterworks Authority show that in 2019, 2.8 billion cu.m. of water was distributed to 7.0 million households, higher than the 2.6 billion cu.m. and 6.2 million households registered in 2015 (data compiled from the same period for two years preceding a drought). Between 2016 and 2019, water demand grew by a compounded rate of 2.1% and in the number of household consumers grew by 3.1% (Figure 6). The natural increase in demand will make the impact of the shortfall in water supply in 2020 more severe than in 2016. This increases risk of water shortage for consumer and industry use in central and eastern Thailand, while in the north and northeast, the agriculture sector would suffer.

In addition to these problems, state agencies could need to allocate water resources for environmental management, for example to protect against saltwater intrusion into drinking water supply during high tide, to prevent damage to machinery used in municipal water supplies, and to preserve natural ecosystems. Hence, the country will start to experience water shortages and the situation is likely to evolve more rapidly and be more acute than during the previous drought[5]. Indeed, as of February 6, 20 provinces6/, mostly in north, northeast and central Thailand, had declared drought emergencies as a prelude to providing assistance to affected districts.

Krungsri Research expects 2020 drought to be more severe than in 2016 given low dam water levels, steadily rising demand for agricultural, industrial and domestic use, higher evaporation rate (as temperatures rise), and a greater need to release fresh water from reservoirs to preventing salt water intrusion due to rising sea levels. Meanwhile, the volume of water flows is much less than water released from reservoirs, while there is insufficient moisture in the air in drought-affected areas to artificially induce rain. Worse, current ONI levels remain close to that which indicate the return of weak El Niño conditions. So, it is likely rainfall levels will remain below average through to May this year, and return to normal only in June but there may still be dry spells in early July.

The impact will vary depending on the region, but the most seriously affected is likely to be the central region because its supply of usable water may be exhausted by April. This would be followed by eastern and northern Thailand where water supply could be exhausted by May.

Impact on industrial activity and manufacturing supply chains

Krungsri Research analyzed the possible impact of the 2020 drought on several industries:

1) Agricultural output

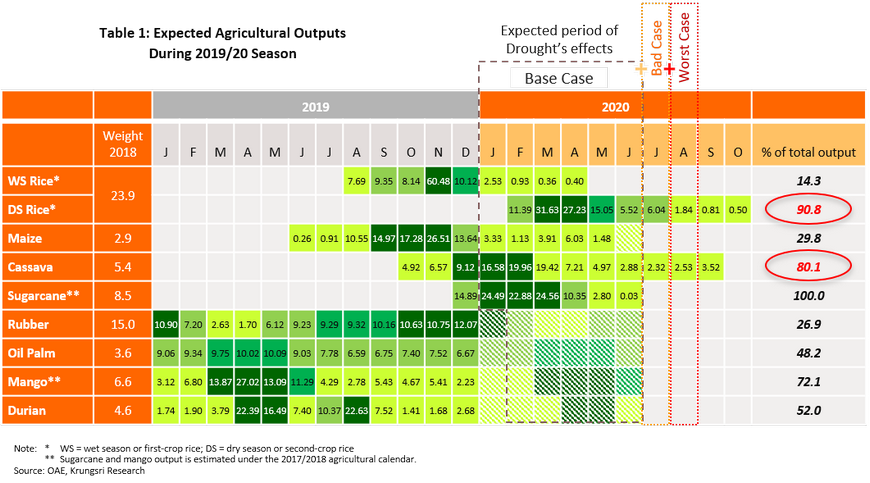

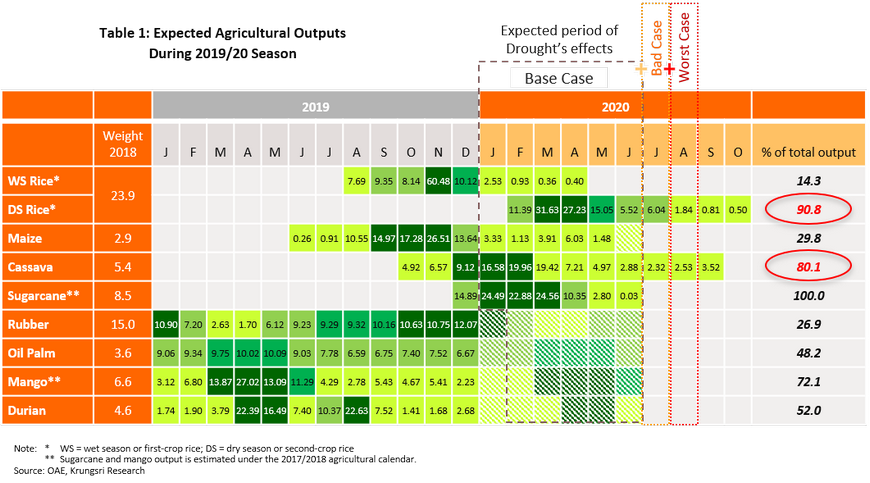

The drought will hurt the output of several important crops, including second rice, cassava, sugarcane, mango, and durian (Table 1). However, the magnitude of the impact will depend on the crop, and when it is planted and harvested. For example, tree crops such as mango and durian can tolerate drought conditions much longer than annual crop or smaller perennials, although in the latter, especially sugarcane, processors will see less impact because harvesting is already underway or completed. In contrast, the most affected will be plants that are freshly planted or have not matured, most notably off-season rice and cassava. Hence, Krungsri Research based its evaluation of agricultural losses on what would happen to these two crops and considered the reduction in output, and how much prices would rise because of the supply shortage.

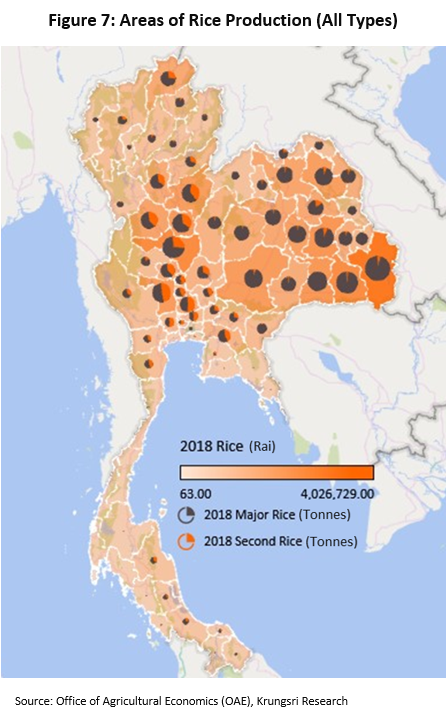

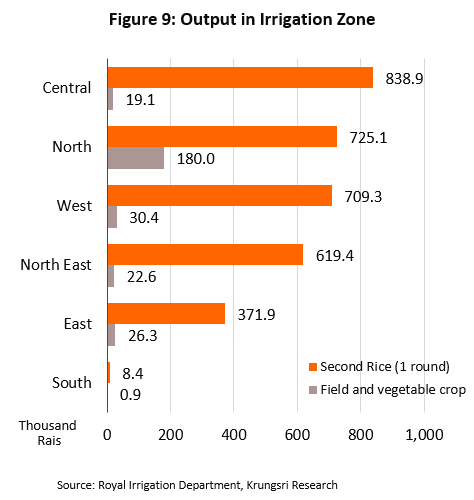

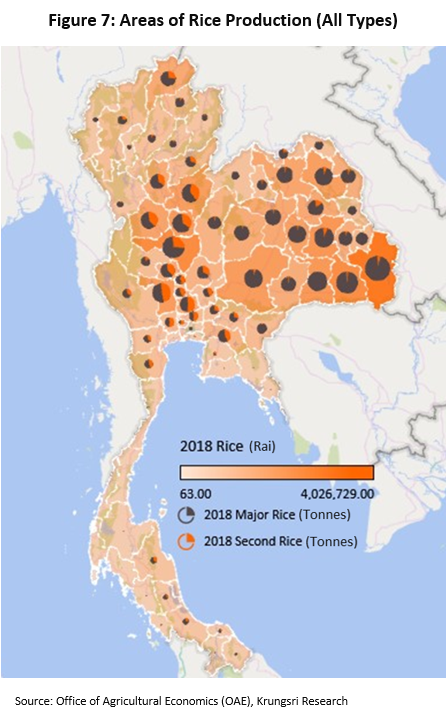

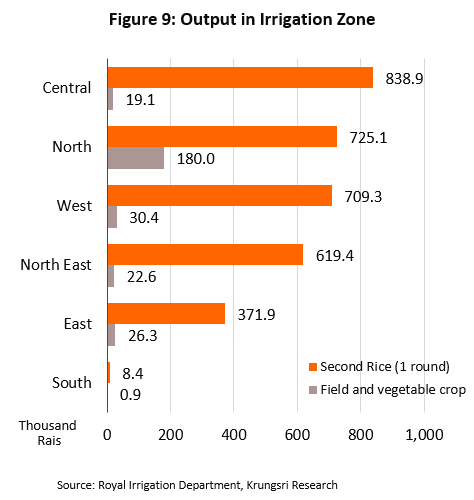

Second rice will be the most seriously affected major crop because the drought would coincide with the peak growing season[7] and it is a water-intensive crop. The bulk of second rice is grown in the central and northern regions (Figures 7 and 9). Thailand had planned to cultivate 2.31 million rai of irrigated rice this season, but it reached 3.32 million rai, 43.6%[8] more than expected.

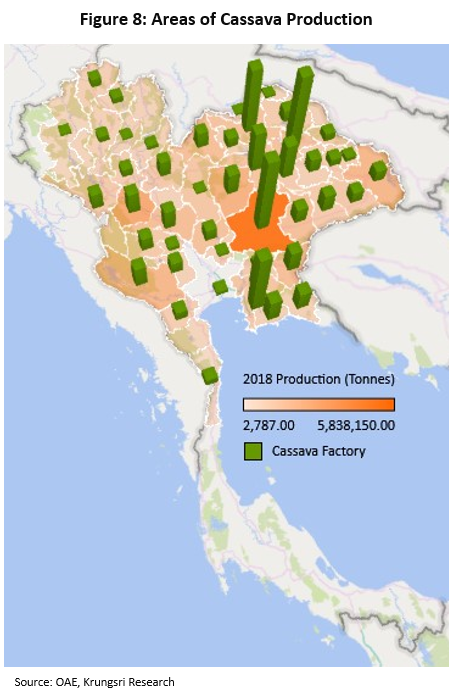

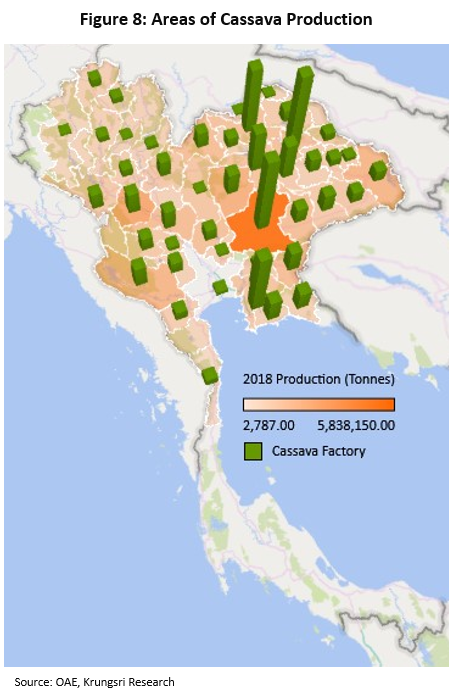

And in the Chao Phraya river basin, although farmers have been asked not to grow second rice at all in the 2019-2020 season, 1.84 million rai was planted. Cassava also faces drought risks. National cassava cultivation in 2019 was 8.63 million rai, mostly in the northeast at 55% of total cultivated area. This is followed by the central region at 23% and northern region at 22%. All 3 regions are vulnerable to the drought (Figure 8).

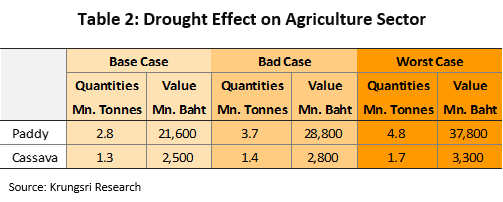

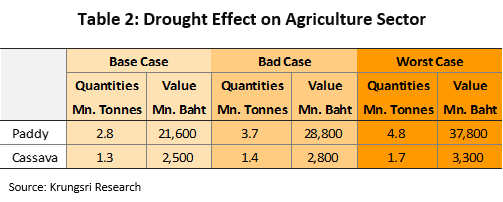

Krungsri Research’s evaluation of agricultural losses is based on reduced yields for second rice and cassava[9] in three different scenarios (Table 2).

- Baseline scenario (drought continues through to May): Losses from rice crop is estimated at THB21.6bn1[10] and THB2.5bn for cassava. Total is THB24.1bn.

- Bad case scenario (drought continues through to June): Losses from rice crop is estimated at THB28.8bn and THB2.8bn for cassava. Total is THB31.6bn.

- Worst case scenario (drought continues through to July): Losses from rice crop is estimated at THB37.8bn and THB3.3bn for cassava. Total is THB41.1bn.

However, the losses could exceed these estimates because water for direct consumption should be the first priority, so water levels in dams and reservoirs need to be managed to ensure sufficient demand for that in the future. This will, unfortunately, have an immediate impact on the output of off-season rice which is widely grown in the central and northern parts of the country (Figure 9).

2) Impact on manufacturing supply chains

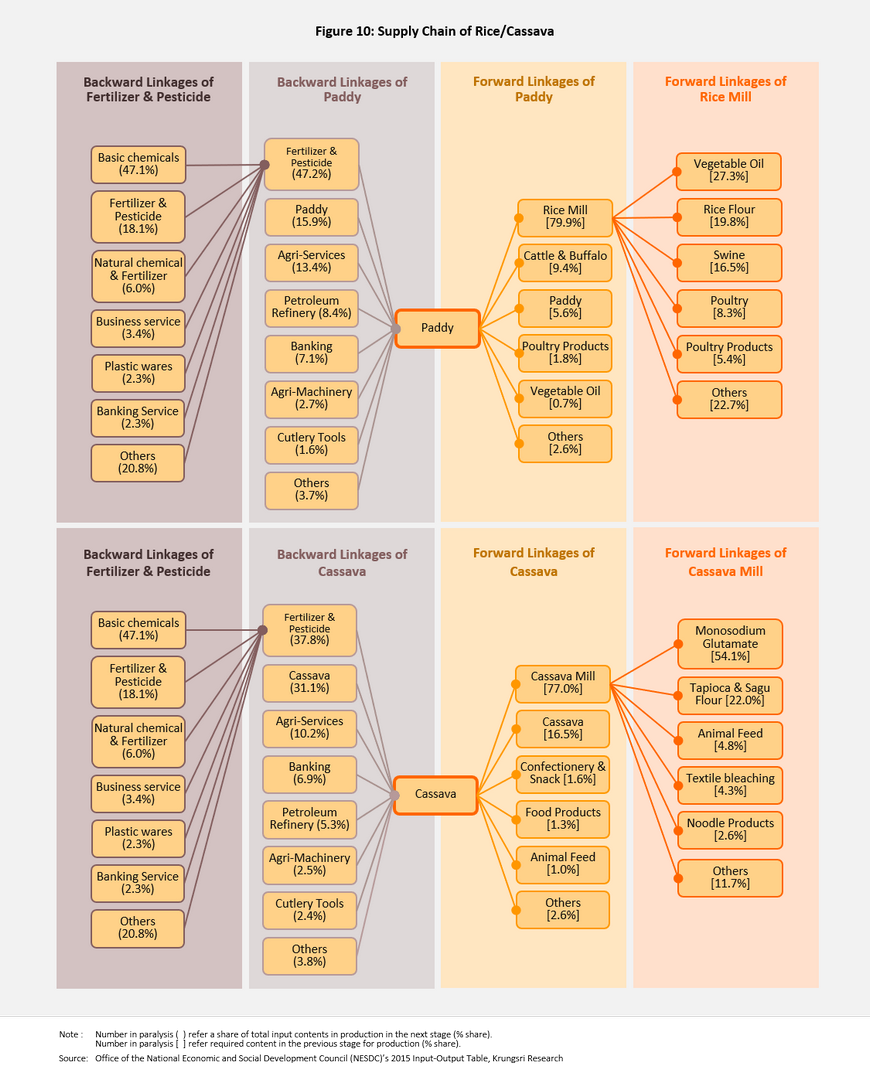

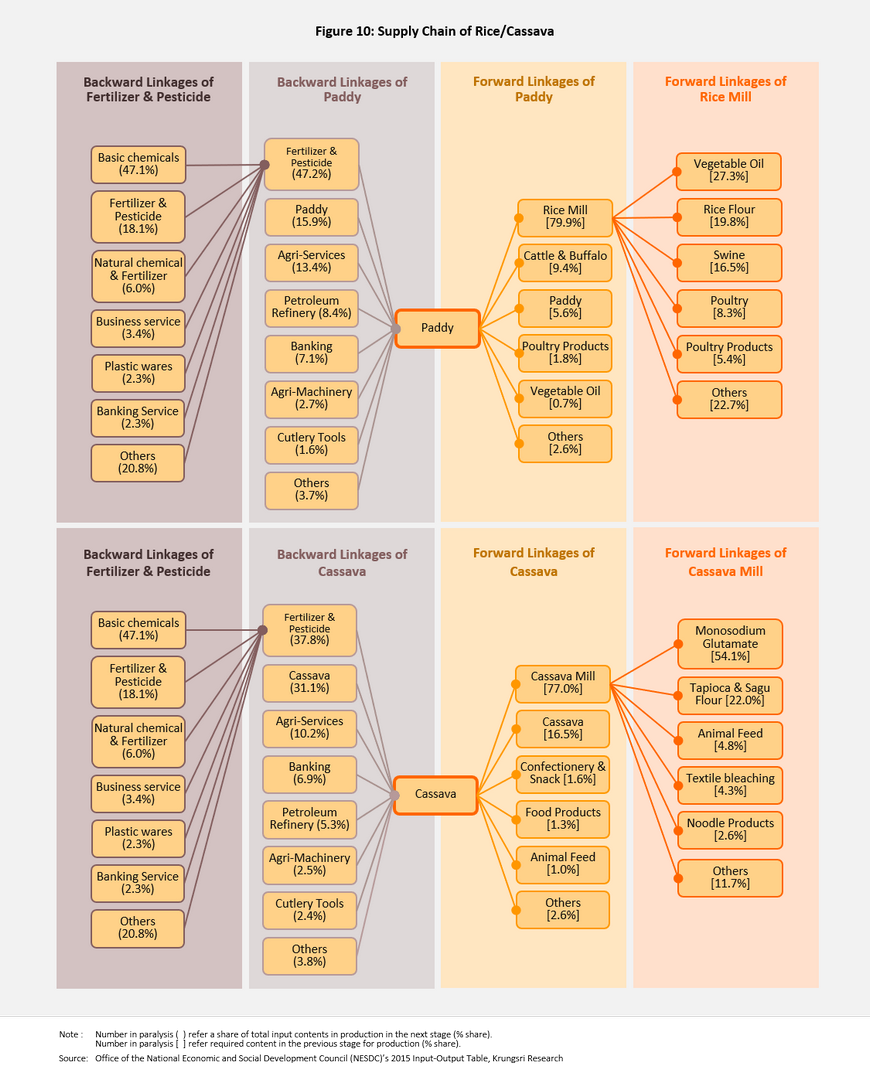

Krungsri Research also evaluated the economic impact of the drought on the manufacturing sector, specifically supply chains that involve agricultural goods, in particular rice and cassava (because these would be the most affected). We applied the 2015 input-output table produced by the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. Our findings suggest losses arising from the drought would also have spillover effects on upstream industries (i.e. lower demand for machinery and products that are used in planting rice and cassava) as well as downstream industries (e.g. reduced production volume and higher input prices driven by supply shortage).

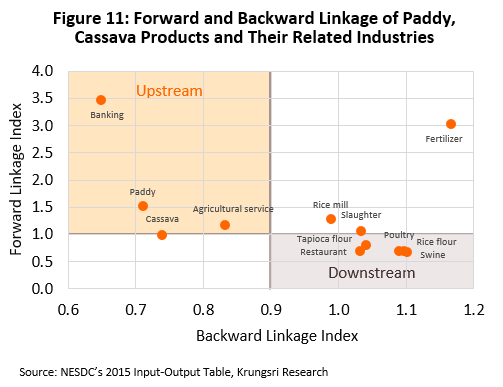

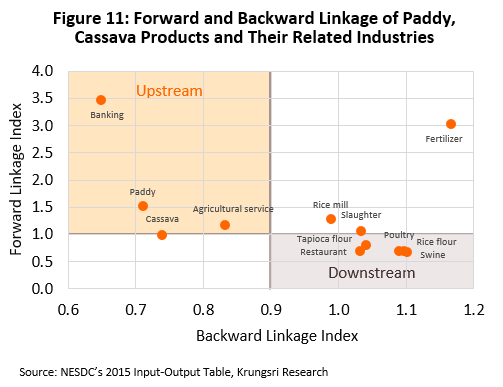

Krungsri Research calculated the FL and BL indices for rice and cassava and quantified the relationship between this and the major manufacturing industries in the supply chains that involve these two crop. The conclusion is that rice and cassava farming are both closely forward-linked than they are backward-linked; the BL and FL indices are 0.71 and 1.53 for rice, respectively, and 0.74 and 0.99 for cassava. This implies the most important role for these two products is as raw material or input for further processing. Because of this, reduced output would have significant knock-on effects on those parts of the manufacturing sector that consume these crop.

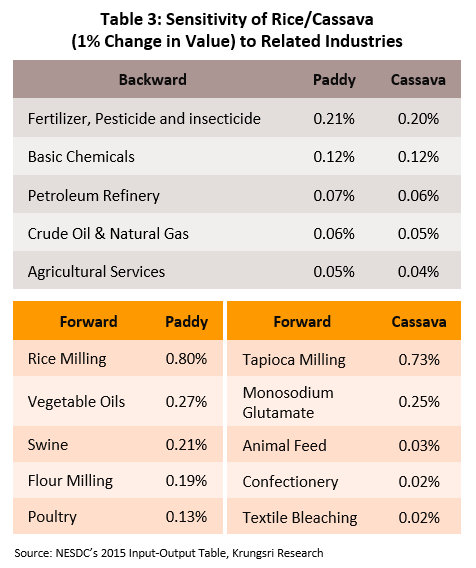

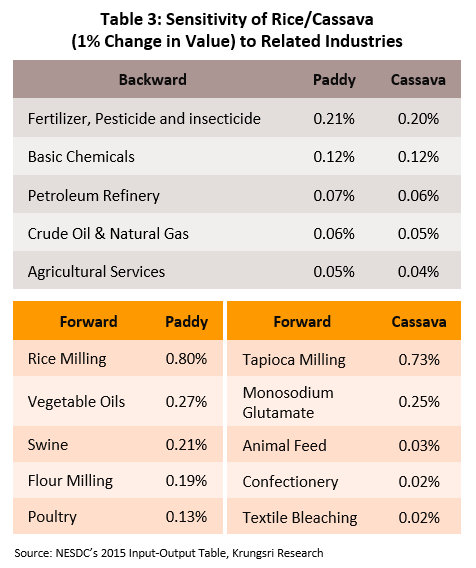

Krungsri Research also conducted a Sensitivity Analysis on the impact of Rice and Cassava on related industries throughout the entire manufacturing supply chains. We estimated how the reduction in rice and cassava output (in value terms) would affect the relevant industrial sectors:

- If drought were to reduce the value of rice output by 1%, it would lead to losses in upstream industries (in value terms), including: Fertilizer -0.21%, Basic Chemicals -0.12%, Petroleum Refinery -0.07%, Crude Oil -0.06%, and Agricultural Services -0.05% (Table 3).

Supply chains involving Rice and Cassava

Backward Linkage (BL): Industries that supply input to farmers

- Rice farming: Fertilizer and insecticides account for 47.2% of costs, followed by seeds (15.9%), agricultural services (13.4%), fuel for farm machinery (8.4%), and debt repayment to financial institutions (7.1%) (Figure 10).

- Cassava farming: 37.8% of costs are attributable to fertilizer and insecticides, 31.1% to purchases of cassava growth stock, 10.2% to farming services, 6.9% to debt repayment, and 5.3% to fuel for machinery.

Forward Linkage (FL): Industries that use rice or cassava as input

- Rice farming: Approximately 79.9% of farmed rice is sent to rice mills for processing to be sold as milled rice. Broken rice bran or other rice by-product are used as animal feed (9.4%), and rice seeds for new planting (5.6%).

- Cassava farming: In terms of total value of cassava-based intermediate products, 77.0% is for downstream processing into manufactured tapioca, 16.5% is replanted, and 1.6% is processed into confectionery and snack products.

- If the value of rice output were reduced by 1%, it would reduce the value of downstream industries as follows: Rice Milling -0.80%, Vegetable Oils -0.27%, Swine -0.21%, Flour Milling -0.19%, and Poultry -0.13%.

- If the value of cassava output were reduced by 1%, it would reduce the value of upstream industries as follows: Fertilizer -0.20%, Basic Chemicals -0.12%, Petroleum Refinery -0.06%, Crude Oil -0.05%, and Agricultural Services -0.04%.

- Every 1% loss in the value of cassava output would reduce the value of downstream industries as follows: Tapioca Milling -0.73%, Monosodium Glutamate -0.25%, Animal Feed -0.03%, Confectionery -0.02%, and Textile Bleach -0.02%.

Based on our analysis, the drought would have direct and indirect effects on upstream industries. At the same time, there would be spillover effects on downstream industries as input costs would rise driven by supply scarcity. Hence, the drought will not only have a direct impact on rice and cassava growers, but also indirect effects on other agricultural products, manufacturing and services sectors.

3) Macroeconomic impact

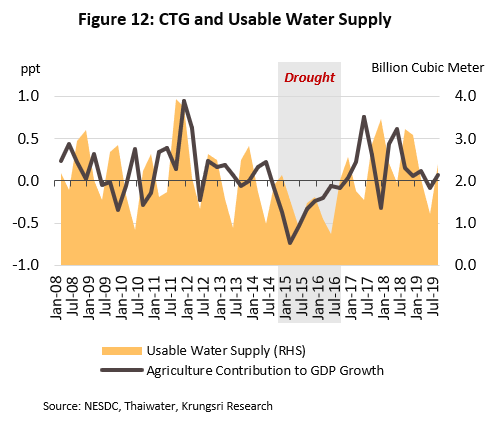

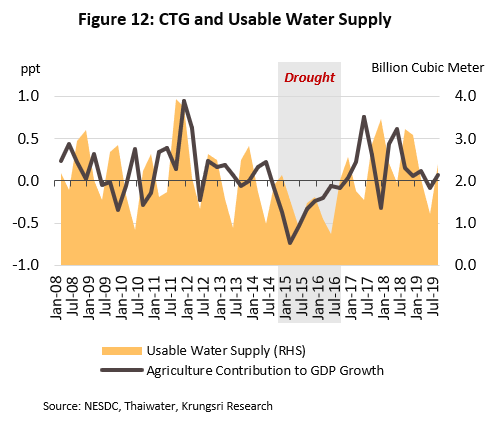

The 2015-16 drought had reduced agricultural sector output and nudged down GDP by 0.3 ppt per quarter (Figure 12). The impact is related to the total quantity of water available for use and prospects of rainfall.

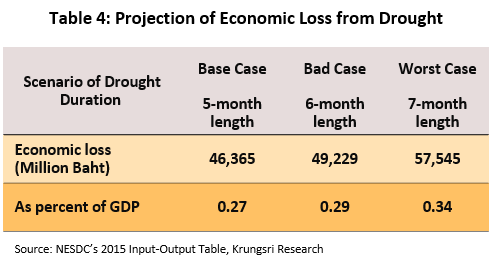

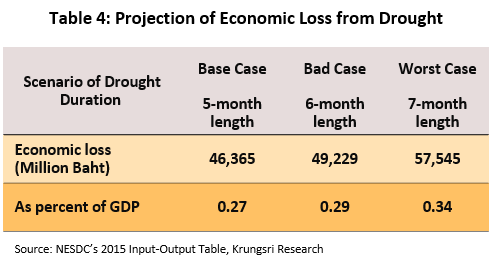

Krungsri Research modeled 3 scenarios to evaluate the financial consequences of drought-induced impact on economic activity.

- Baseline scenario (drought continues through to May): Total losses is estimated at THB46.37bn, or 0.27% of GDP.

- Bad case scenario (drought continues through to June): Total losses is estimated at THB49.23bn, or 0.29% of GDP.

- Worst case scenario (drought continues through to July): Total losses is estimated at THB57.55bn, or 0.34% of GDP.

Initial estimate of damage and quick response by Thai authorities

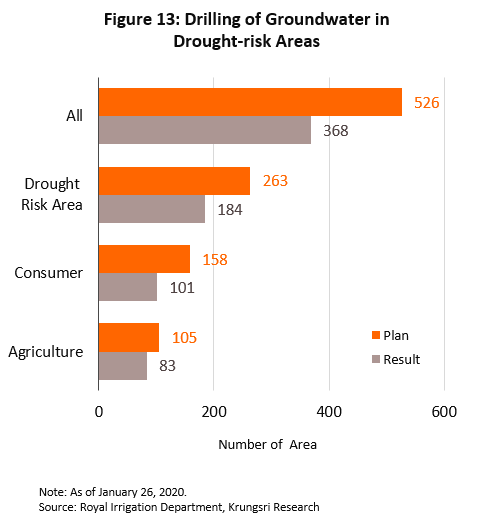

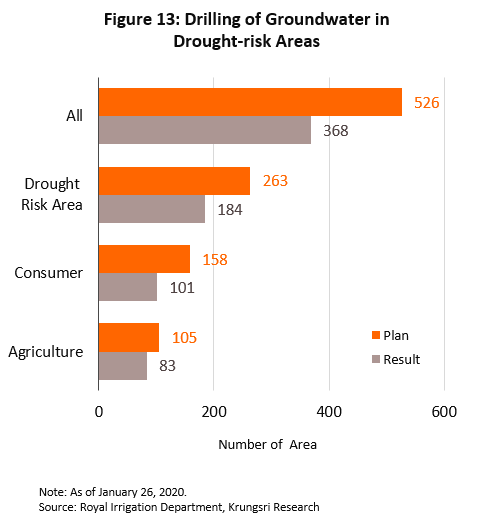

In terms of losses arising from the drought, the Office of Agricultural Economics estimates that losses have so far occurred in 20 provinces, affected 0.12 million farmers and impacted almost 1.27 million rai of farmland, split between 1.11 million rai of rice, 0.16 million rai of other cereals and field crops, and 778 rai of horticultural and other crops. These losses total THB1.42bn, although some help has been forthcoming from government agencies, which have paid compensation for a portion of the losses, distributed drinking water in certain areas, and helped with the digging of new wells, even if the total number of wells that have been dug has not yet reached the targets set (Figure 13).

As regards assistance for those affected by the drought, the government has raised the importance of the issue on the national agenda and at the suggestion of the Office of National Water Resources, on January 7, the cabinet approved the allocation of THB3.08bn from central government funds reserved for emergencies to alleviate problems arising from water shortages in the period 2019-2020. This money will be used to pay for well-digging, management of surface water, and repairs to water mains, and also to aid farmers impacted by the drought, who will be provided with assistance and consultation in the form of education about and help with cultivating less water-intensive crops and/or relaxation of the repayment of debts owed to government-operated financial institutions.

Drought is estimated to shave 0.3ppt off 2020 GDP growth

Krungsri Research concludes Thailand could face harsh drought conditions again this year, and it could be more severe than in 2016. The emergence of weak El Niño conditions in 2018 was evident in the extended dry season and below-average rainfall in 2019, which has reduced the total volume of water available across the country. Moving into 2020, the critically-low levels imply risk of water shortage in many areas. The effects will be felt not just within the agriculture industry but also in the industrial sector. In the agricultural sector, crops that are sensitive to drought will be most affected over the next few months, notably off-season rice and cassava. But the drought will also be felt throughout entire manufacturing supply chains. The impact may be more severe for downstream industries than upstream producers. Our baseline projection is that losses in rice and cassava output (by value) could reach THB21.6bn and THB2.5bn, respectively, and the 2020 drought would cost the country THB46bn, or 0.27% of Thailand’s GDP. The impact could be more severe if the drought crisis lasted longer than the baseline scenario assumes. In the worst case scenario, losses in rice and cassava output (by value) could reach THB37.8bn and THB3.3bn, respectively, and total losses are projected to reach THB58bn, or 0.34% of GDP.

Beyond this, the government has prepared measures to cope with the impending drought, including a relief budget from the Central Fund and income-guarantee for rice and cassava growers. However, there is uncertainty over budget disbursements following the prolonged delay in enactment of the fiscal 2020 Budget Bill. Meanwhile, the government is authorized to comply with the previous year’s budget bill as a framework to roll out disbursements pending the passage of the current year’s budget bill. However, the fiscal 2019 budget seems insufficient to cope with the drought this year because it is expected to be more severe, especially the rehabilitation budget for farmers and manufacturers affected by the drought.

Water allocation and situation as of January 29, 2020

1) Plans are for the release of 17.70 bn cu.m. of water (61%) for use during November 2019-April 2020.

- Water for domestic consumption: 2.3 bn cu.m.

- Water for environmental uses: 7.01 bn cu.m.

- Water for use in agriculture: 7.87 bn cu.m.

- Water for use in industry: 0.52 bn cu.m.

2) Planned water reserve of 11.34 bn cu.m. (39%) for use during May–July 2020, comprising:

- Water for domestic consumption, environmental purposes and other uses: 4.91 bn cu.m. (43%).

- Reserved for dry season use: 6.43 bn cu.m. (57%)

3) There is a risk the volume of water distributed could exceed the targets

- Of the total, 7.95 billion cu.m. (or 45% of the total) had been distributed as of January 29, leaving 55% or 9.75 billion cu.m. still to be released. And although there is 42.08 billion cu.m. of water stored (59% of capacity), the volume of usable water is much lower at just 18.54 billion cu.m. (or 26% of capacity).

- Currently, the volume of water released in two zones, the Chao Phraya river basin (where there are 4 major reservoirs) and the Mae Klang river basin, has exceed the targets by 0.3-0.5 billion cu.m. However, in the Mekong, Chi and Mul river basins, and in the EEC zone, water release is according to the plan put in place by The Office of National Water Resources. This suggest the central region faces highest risk of experiencing a shortage of drinking water, followed by the northeast and the north.

Assistance and support provided by the public and private sectors

As of January 26, 2020, the following official assistance are provided in response to the drought:

- Ministry of the Interior: The armed forces have been assisting by distributing water, providing water tanks, checking dams and digging wells.

- Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation: The Department is supplying pumps and machinery to help maintain mains water supplies and to extract water from wells.

- Department of Irrigation: The Department has revised its plans for releasing water from large and medium-sized reservoirs where levels are below 30% of capacity, and is supporting the use of pumps, continuously checking on water quality, and preventing saltwater intrusion along the Chao Phraya River.

- The Department of Water Resources: The Department is supporting the use of pumps and other machinery in agricultural areas and distributing water where needed.

- Department of Groundwater Resources: The Department is establishing permanent new water distribution points, using trucks to distribute water, checking water quality and digging new wells.

- Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC): The BAAC is: (i) extending the period for loan repayments (both interest and principal) to December 31, 2021 for farmers who have experienced drought for 2 years, and (ii) is offering low-interest loans (3% p.a.) from a THB5bn fund to farmers and businesses who use the loan to manage drought conditions by developing alternative sources of water.

As of January 26, 2020, the following official assistance has been provided in response to the drought:

- The Cooperative Promotion Department (CPD) has set up three projects in response to the drought:

- Loans are being made available to members who engage in mixed farming (i.e. who grow crops and raise livestock) and who need to develop an onsite water source (e.g. a pond or well) to use for agricultural purposes. Loans are from a THB500m fund and each loan could be up to THB50,000. The loans are repayable over 5 years and interest is charged at 1% per year.

- A project has been set up to provide funds to co-operatives in areas affected by drought. This provides them with the capital required to buy produce from co-operative members (produced by members borrowing under project (1). So members will be able to sell their produce to the co-operatives, which would use this fund to buy the produce. The THB415m program will run until September, and interest would be charged at 1% per year.

- The CPD has an ongoing project to promote corn cultivation after the rice harvest. But for 2020, the target is to plant corn on co-operative land in 28 provinces. The THB100m fund can be used to help co-operative members buy inputs such as seeds and fertilizer. Interest is charged at 1% per year.

- Income guarantees: These are expected to help farmers but the drawback of price support is that when prices go up, the additional benefits that farmers receive drop immediately. And generally, droughts tend to lead to significant price increases. Hence, income guarantees could have limited positive impact on farmers.

[1] If the ONI Index is in the range of 0.5-1.0, this signifies that a weak El Niño has emerged, a value of 1.0-1.5 is classified as a medium-strength El Niño and a value over 1.5 qualifies as a strong El Niño. When the index turns negative (i.e. moves in the opposite direction), the same risk scales are used, but these are applied to a La Niña event instead.

[2] Data from the Meteorological Department.

[3] The Mekong River Commission comprises Thailand, Myanmar, Lao PDR, Cambodia, China (Yunnan) and Vietnam.

[4] To prevent salt levels rising above 0.25 gram]liter.

[5] Based on assumptions about water management in 2016 and usage in 2019.

[6] Chiang Rai, Nan, Nakhon Phanom, Maha Sarakham, Bueng Kan, Nong Khai, Buriram, Kalasin, Kanchanaburi, Chachoengsao, Phetchabun, Uthai Thani, Nakhon Ratchasima, Uttaradit, Chainat, Nakhon Sawan, Sukhothai, Suphanburi, Phayao, and Sakon Nakhon (source: Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Ministry of the Interior).

[7] Farmers generally plant second rice in November and then harvest in March and April. Plantation area for second rice accounts for 19.0% of total plantation area for rice.

[8] Data from the Royal Irrigation Department, January 29, 2020.

[9] The impacts cover white rice and will occur through the period from November 2019 to April 2020, which are the main months for growing second rice. 91.4% of the rice grown in this period is standard white rice and a further 8.6% is glutinous rice. Jasmine rice is generally grown during the wet season.

[10] Taking into account the month of harvest, the proportion of the total area cultivated that is both irrigated and not irrigated, the type of crop, the chances that yields will be impacted, and current prices.