Construction in the CLMV region: Opportunities for Thai contractors

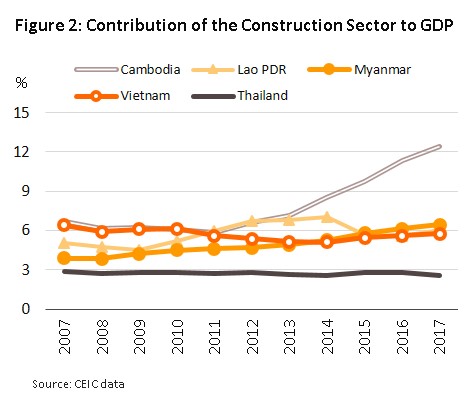

The CLMV countries have attracted increasing attention from foreign investors following the formal establishment of the Asean Economics Community (AEC) in 2015. Economic expansion and increasing levels of urbanization have also spurred the development of infrastructure to support further growth within these countries, and this represents opportunities for Thai construction companies to expand into countries that are seeing ongoing growth.

This analysis thus evaluates the construction sector across the CLMV countries in terms of the opportunities and limitations. The research is based on a country by country macro-level consideration of sectoral readiness, together with the sectors’ structural features, and the result of this analysis is that because of the volume of large-scale construction projects being undertaken and the rate of growth in the sector. Vietnam is at present the most promising market for construction business, followed by Cambodia, which is seeing strong growth in construction, as well as benefitting from a lengthy shared border with Thailand. Myanmar, although outside investors in the country face a greater number of obstacles than they do when investing in the other CLMV nations, the government is attempting to ease regulation for attracting higher levels of investment. For its part, Lao PDR is seeing only a relatively low level of construction value, however opportunities still exist in mid- to small-sized developments. Overall, those entering the construction market in the CLMV zone will encounter high competition from overseas players and so to ensure a continuing stream of work, Thai operators should look for domestic companies within the business supply chain to partner with. These could include local property developers or construction contractors, or agencies providing employment for local workers.

Growth potential in the CLMV region…supporting players in the construction market

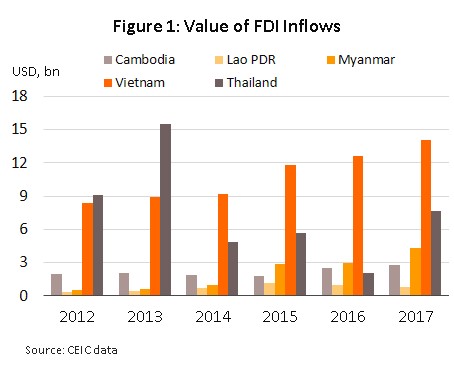

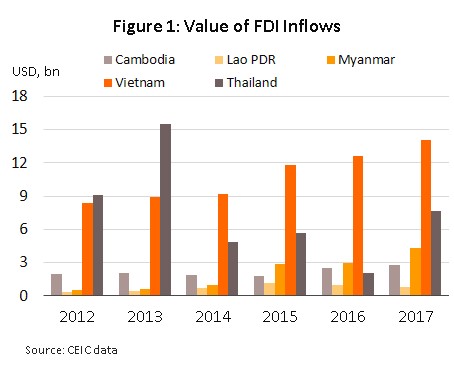

In the recent past, the CLMV countries of Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam have been able to attract a steady stream of foreign direct investment (FDI) (Figure 1). During 2012-2017, FDI inflows to these countries increased by 18% per year. This state of affairs was supported by: (i) strong economic growth in the region, which averaged 6.5% per year in the period; (ii) the abundance of natural resources in these countries, which serve as important sources of raw materials for the manufacturing sector; and (iii) the large supply of low-cost labor in the region.

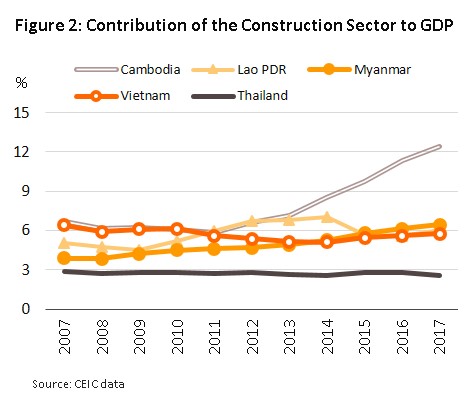

In addition, the profile of these countries has risen following the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015, which has led to an increase in economic activity and with this a rush to develop the infrastructure required to support growing rates of urbanization. These changes can be seen in the steadily growing proportion of national GDP taken by construction within the CLMV countries during 2012 and 2017 (Figure 2). Growth has been most pronounced in Cambodia, where the construction sector has expanded by an average of 25% per year. In the other three countries of Myanmar, Lao PDR and Vietnam, their respective construction sectors have grown at annual rates of 19%, 12% and 10%. However, in terms of overall size of the construction market, Vietnam is the most important of the CLMV nations, followed by Myanmar, Cambodia and Lao PDR (figures 3-4). This difference has arisen because Vietnam receives the most FDI in the group and this has fed a greater level of investment in infrastructure and real estate projects.

These trends thus present Thai construction companies with an opportunity to expand their operations into the growing markets in these countries, whether that be for infrastructure work, industrial, commercial or residential buildings. Currently, with the exception of Myanmar, the authorities in these nations permit foreign investors to hold 100% of the shares of local construction companies. This helps to reduce the difficulties companies might have with bringing in specialist labor, such as engineers and architects, and Thai construction companies that use specialist techniques and that have particular engineering expertise will therefore benefit from this fact. From a geographical perspective, Thailand’s shared border with three of the four CLMV countries also helps to reduce the costs of doing business by making it cheaper to move labor, and machinery to sites overseas.

Factors indicating attractiveness of doing business in construction sector in the CLMV

An evaluation of the factors that have an influence on decisions to move into the CLMV market is based on (i) the readiness of macro-level factors and (ii) structural factors relating to the construction sector. An exploration of these is given below.

i. The readiness of macro-level factors in the construction sector is analyzed through an application of “the Five Force Model” to the indicators that point to both the opportunities and limitations confronting investors.

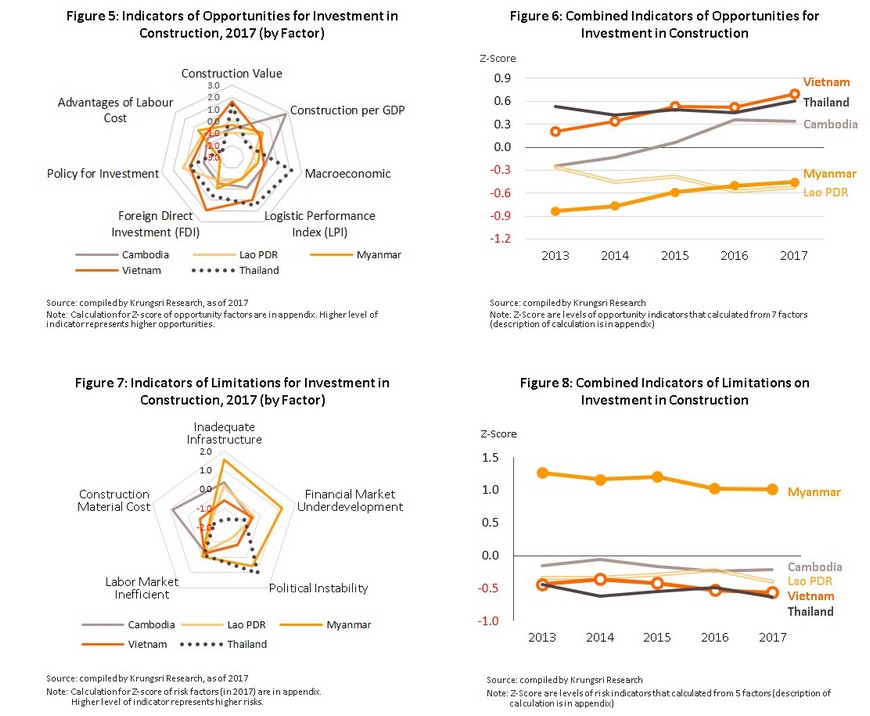

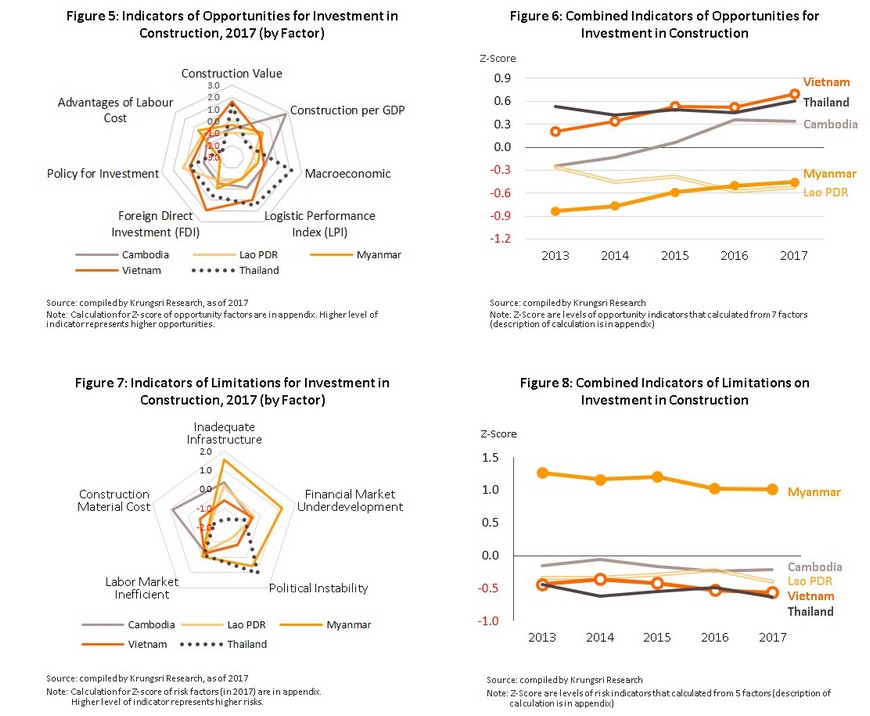

- indicators of opportunities are assessed through 7 factors: 1) construction value (measured by its contribution to GDP); 2) construction per GDP; (3) macroeconomic environments (evaluated from an economy’s score on the Global Competitiveness Index, or GCI); (4) the readiness of logistics networks (evaluated from Logistic Performance Index, or LPI); (5) the level of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country; (6) national policy related to investment (evaluated from the ‘institution’ component of the GCI); and (7) advantages of labor cost. These indicators are ranked and a higher score indicates greater opportunities with regard to that factor (figure 5), while overall, the country with the greatest score will have the most positive environment for investors, relative to the other countries that have been scored (figure 6).

- Indicators of limitations are assessed through 5 factors: 1) inadequate Infrastructure for construction projects (converted score of the ‘infrastructure’ component of the GCI); 2) financial market underdevelopment (converted score of the ‘financial market development’ component of the GCI); 3) political instability (evaluated from the Political Stability Index); 4) labour market inefficiency (converted score of the ‘labor market efficiency’ component of the GCI); and 5) construction material cost (for which cement prices stand as a proxy). As above, these factors are divided out and a higher score indicates that in that country, that factor is more limiting on investment (figure 7), while a country that has a higher total score from the summing of all these factors will have a market that investors will find to be more restrictive (figure 8).

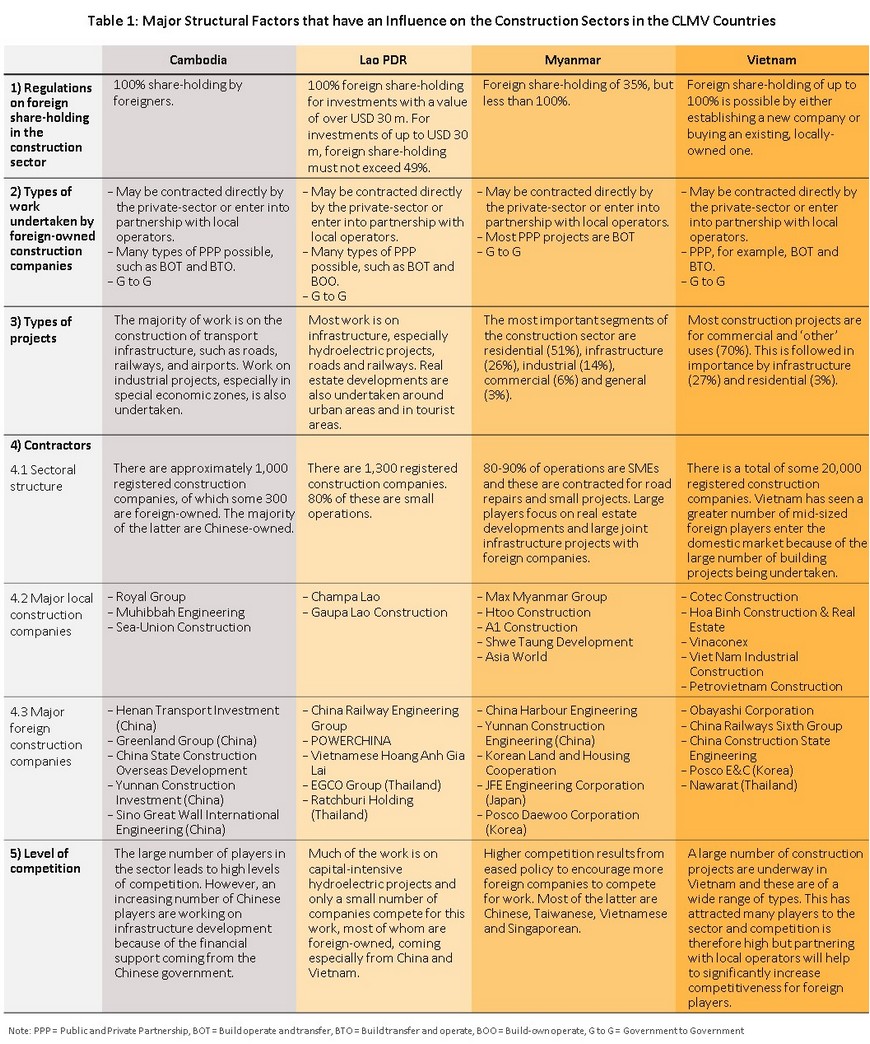

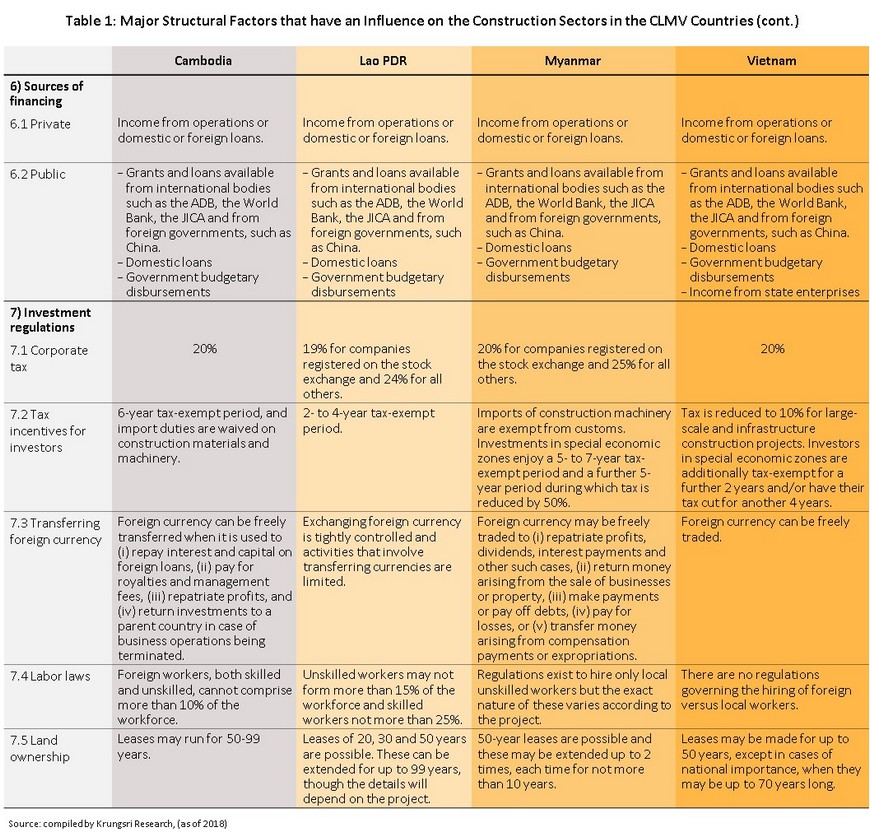

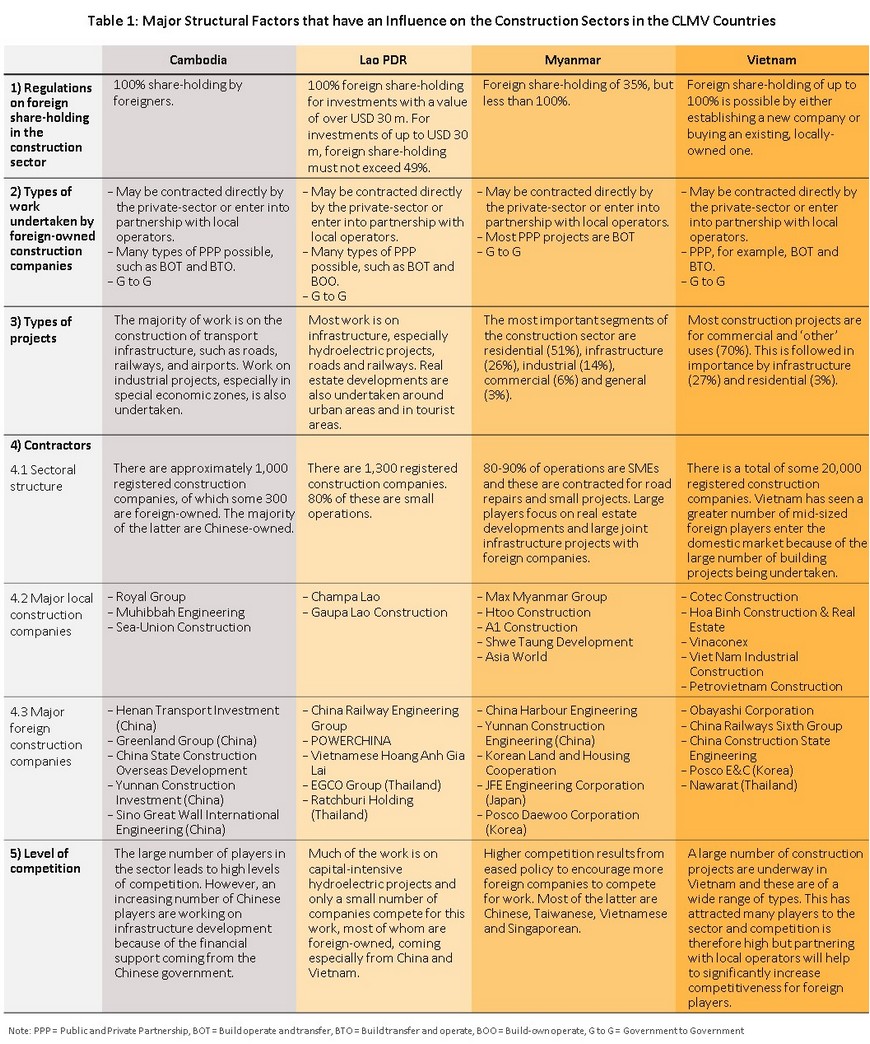

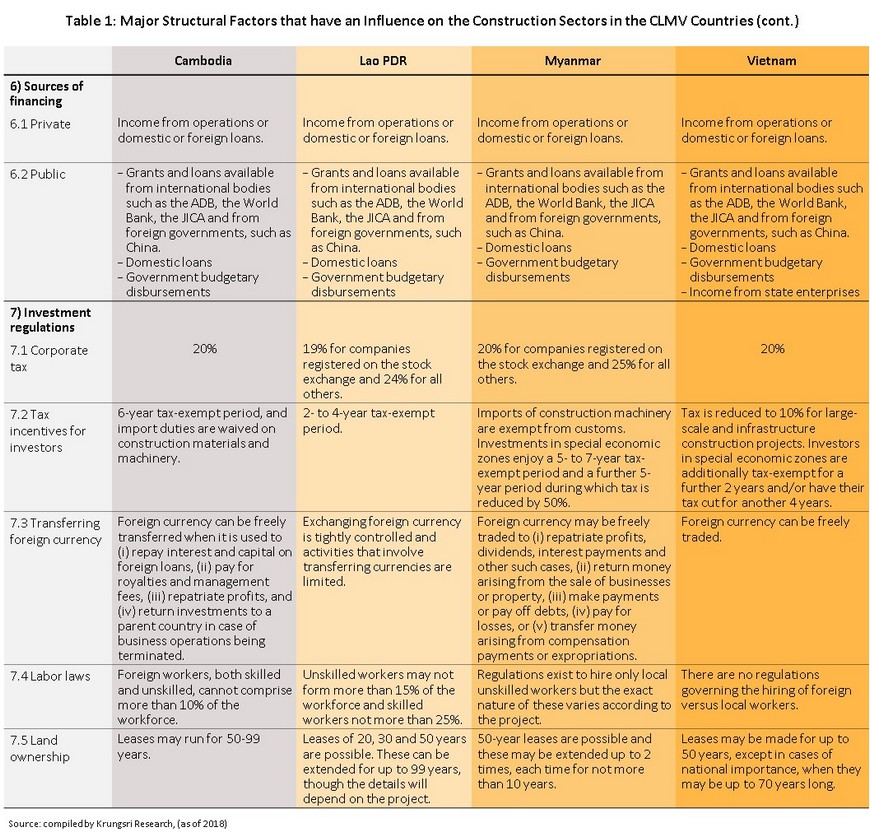

ii. Structural factors of construction contractor businesses are assessed from basic information on the structure of the market that can be expected to have an impact on construction contractors operating in the CLMV countries. These are: 1) limitations on share-holding in construction companies by non-nationals; 2) type of work undertaken by foreign-owned construction companies; 3) the types of construction work being undertaken; 4) the level of competition in the market; 5) the characteristics of the players in the construction sector; 6) sources of financing; and 7) regulations governing investment, in particular with regard to tax and non-tax incentives (table 1).

The evaluation of macro-level factors in the CLMV’s construction sector:

I. Krungsri Research evaluation of the macro-level factors determining the attractiveness of the construction sectors of the CLMV nations is based on principle component analysis (PCA). This shows that the indicators for opportunities are weighted 23% the construction value, 23% the construction per GDP and 17% the macro-economics environment. For the limitations, the factors are: inadequate infrastructure (37%), financial market underdevelopment (29%) and political instability (22%) (further details are given in the appendix.) Between 2013 and 2017, under this analysis, Vietnam had the greatest level of positive factors supporting the construction sector and the lowest level of limitations on it. Myanmar was in the opposite position to Vietnam, having the fewest positive factors and the greatest limitations (figures 6 and 8), though this said, the situation in Myanmar is evolving and opportunities in construction are steadily improving. Details of the situation for individual countries in the period 2013-2017 are given below.

- Vietnam enjoys advantages arising from the size of its construction sector and the number of construction projects underway, which is the highest in the CLMV region. Although the rate of growth of the Vietnamese construction sector is lower than that in Cambodia and Myanmar, it is still on an upward trend and the country also benefits from a number of other positive factors relative to the other CLMV countries, including the size of its FDI inflows, the development of its logistics sector, and the low level of limitations on construction contractors, particularly in terms of the development of national infrastructure and financial markets.

- Cambodia, in terms of the opportunities it presents to operators in construction, is the second-most attractive of the countries that are considered here thanks to the rapid rate of expansion of its construction sector, which contributes a larger share to GDP than in the other CLMV countries. However, the nation still needs to develop its logistics sector and to put in place better policies to attract FDI. In terms of limitations, construction materials are more expensive than elsewhere and there is a lack of access to public utilities.

- Myanmar benefits from large number of infrastructure project and this has helped to lift growth in construction sector to the second-highest in the CLMV group. However, on the flip side of the coin, looked at in terms of opportunities for construction companies, between 2013 and 2015, the country was the lowest performing in the group and in 2016 and 2017, Myanmar performed better than only Lao PDR in this regard. Positive factors for Myanmar are the acceleration of its logistics system development and the increasing levels of FDI, while in terms of limitations, these were the highest of the group, with political instability, insufficient infrastructure support and the weak development of financial markets being a particular concern.

- For Lao PDR, between 2013 and 2017, its advantages included low labor costs and government policy which aimed at making investment easier but the country still needs to develop its transport system to attract greater levels of FDI. In terms of limitations, these were at a relatively low level by 2017, having fallen from higher levels four years earlier on (i) a decline in the price of construction materials, due to manufacturers opening production facilities within the country itself, and (ii) the improving situation with access to public utilities, especially electricity.

ii. The evaluation of structural factors in the CLMV’s construction sector:

Apart from the assessment of macro-level factors that indicated the opportunities and limitations of doing business in the CLMV countries, the evaluation of structural factors on construction sector in each countries should be considered together. Krungsri Research’s study is showed the details on table 1

The assessment of the structural factors affecting construction operators in the CLMV region (given in the table above) shows that in all countries, governments have tried to ease regulations and to make it easier for foreign players to invest in construction in the domestic market, for example by (with the exception of Myanmar) allowing 100% foreign ownership of construction companies and by offering higher levels of tax and non-tax incentives to investors. With regard to public investment, the governments of all countries have put in place policies to push forward the rollout of improvements to national infrastructure and public utilities and this will help to stimulate increased private construction by spurring on increased levels of commercial, industrial and residential building work. However, each of the four countries has its own particular features that make it attractive to players in construction, and these are detailed below.

- Vietnam: Here, relaxation of regulations in favor of foreign operators has been fairly extensive and has included: allowing the purchase of local companies by foreign players, who may then hold 100% of shares in these companies; increasing tax incentives to companies investing in large-scale projects; allowing leases of up to 70 years for developments of national important projects; and permitting foreign exchange transfer to be carried out without hindrance.

- Cambodia: The Cambodian government now offers tax and non-tax incentives to attract foreign investors to the country. These include allowing operators to return their investments to their home country should they need to suspend operations, and to lease sites for up to 99 years, which will help to appeal to concession holders of, for example, motorways. Although restrictions on foreign currency transfers are tighter than in Vietnam.

- Myanmar: Moves are underway in Myanmar by the government to increase opportunities for foreign players to participate in the local construction market, including for example allowing foreign companies to invest in infrastructure under the public private infrastructure partnerships (PPPs) but restrictions on the market remain tighter and less inviting to overseas operations than elsewhere. Thus, foreign players may not fully own local operations and the government maintains restrictions on hiring foreign workers and on making transfers of foreign currency.

- Lao PDR: The most attractive feature of the market in Laos is the offering of concessions of up to 99 years for some projects, although the details of this vary with the type of development. However, the country is relatively sparsely populated and is largely composed of mountains or highlands, so work in construction and transportation faces a number of obstacles, while restriction on exchanging the local currency tends to weaken investor confidence.

In conclusion, the macro-evaluation of each country’s sectoral readiness, taken together with the assessment of the impact of the structural factors on players in construction in the CLMV region, shows that Vietnam is the country which is most favorable towards investment in construction. Construction in Vietnam is worth more than in the other countries, encompasses a greater number of projects, and continues to exhibit steady growth. With regard to the provision of utilities, the cost of construction supplies, political stability, and the development of financial services to support that they offer business investment, the market is also less restrictive and more supportive of business than in the other countries surveyed. Following Vietnam comes Cambodia, where the construction sector is growing at a high rate and which benefits, with regard to Thai operators, from its shared border with Thailand, which makes transporting labor and machinery easier and more convenient. By comparison, the provision of utilities and infrastructure in Myanmar is somewhat lacking, while financial institutions are relatively immature and the direction of change in the country’s politics remains at risk, though at the same time, the government is attempting to relax the regulations governing investment and to speed up work on the build-out of basic utilities, including the expansion of the national power grid. It is expected that this will pull in greater levels of private investment in its wake, for example, the real estate development projects. As for Lao PDR, investment by foreign players is lower than in the other three countries due to the country’s relatively small number of construction projects and the fact that the projects that are undertaken tend mostly to be for hydroelectric power generation. Moves to develop the national transportation network are still mostly only small-scale and dependent on funding by international organizations or foreign governments. Despite this, some building projects in Laos may be suitable for operators that take on small and mid-sized projects, such as the construction of roads and small power stations.

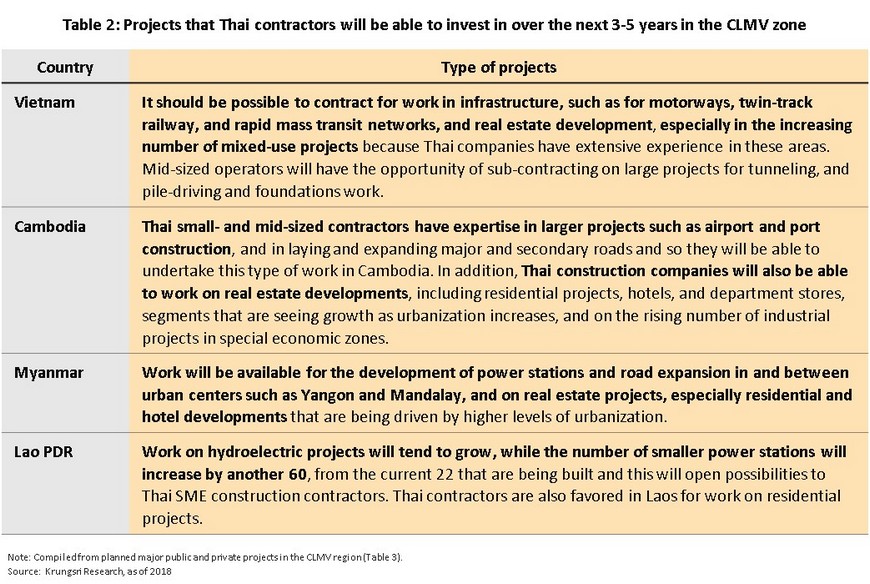

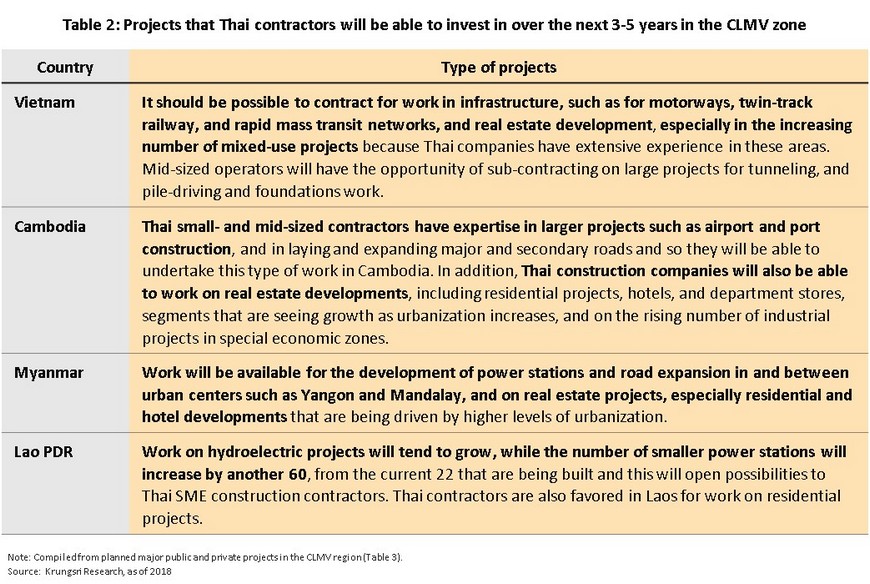

Looking at the major projects that are likely to get underway in the CLMV countries over the next three years, it is clear that the value of construction work in the region will see double-digit growth in the coming period and as such, significant opportunities will exist for Thai contractors to expand their markets. The situation is, though, complicated by the fact that within the CLMV group, major foreign contractors already have a presence in the market through participating in, for example, government-to-government projects with other influential countries in the region, such as China, Japan and South Korea, or in projects that are funded by global organizations such as the ADB and the IMF, which may then push contracts to companies from their home countries. Thus, Thai contractors would be advised to partner with local operators when attempting to move into these markets. These partners should be positioned within the local construction supply chain, and might include real estate developers, local building contractors, manufacturers or distributors of construction materials, and agencies sourcing manual labor. Doing so will help to open a channel through which to secure contracts on an ongoing basis, especially for projects that secure a steady stream of income, such as concessions to operate road tolls, as well as creating continuing opportunities for subcontracting.

The types of projects with which Thai contractors have experience and that are expected to become more numerous in the coming period (according to plans produced by the public and private sector) are summarized in the following table.

Appendix

1) Indicators of opportunities

The index of business opportunities for construction companies in each of the CLMVT nations between 2013 and 2016 is calculated from 7 variables: (i) the value of the construction sector (from the contribution of construction to GDP); (ii) the proportion of GDP attributable to construction; (iii) the state of the national logistics sector (calculated from the Logistic Performance Index, or LPI); (iv) the level of foreign direct investment (FDI); (v) the state of macroeconomic factors (assessed from the macroeconomic aspect of the country’s Global Competitiveness Index, GCI); (vi) labor costs; and (vii) government policy as it relates to investment (assessed from the ‘Institutional’ score of the GCI). Each factor is standardized according to its z-score, with the score for each factor reflecting the extent of the business opportunities that it reflects, and the higher the score, the greater the opportunities. Following this, average scores for the period 2013-2016 were calculated for each of the 7 variables and, by using principle component analysis (PCA), the most significant factors were isolated. This then allowed the indices for the different countries to be compared and ranked. Details of the 7 variables are as follows.

- Construction Value: This factor reflects the level of investment in construction in each of the countries. The value draws on information from the value of construction in each country’s annual GDP.

- Construction per GDP: This shows the importance of construction to each country’s economy, and it is calculated from the proportion of construction in the total national GDP.

- Macroeconomic Environment: This shows the overall state of each country’s economy and is based on the ‘Macroeconomic Environment’ factor of the World Bank’s GCI.

- Logistic Performance Index (LPI): This indicates the state of national logistics and transportation infrastructure. The value is based on the World Bank’s Logistic Performance Index (LPI).

- Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): This factor reflects the direction of growth in investment inflows from overseas and is based on the value of FDI.

- Policy for Investment: The last factor is based on government policies and regulations that support investment in each country. This is based on the ‘Institution’ aspect of the World Economic Forum’s GCI.

- Advantages of Labor Cost (minimum wage): This factor reflects the advantages a country may have with regard to its labor costs, and is calculated from the country’s minimum wage.

2) Indicators of limitations

The index of limitations facing construction contractors in the CLMVT countries in 2013-2016 is calculated from 5 variables: (i) the cost of construction materials; (ii) the level of political stability; (iii) the level of development of the country’s financial markets; (iv) the provision of public utilities; and (v) the level of development of the workforce. As before, the variables are standardized using z-scores, and the higher the score for each variable, the greater the obstacle or risk it is to carrying out business. Average scores for the years 2013 to 2016 were calculated for each of the 5 variables and principle component analysis was used to determine which variables have the greatest impact on risk overall. The countries’ scores were then ranked and compared. The five variables were as follows.

- Inadequate Infrastructure: This measures the provision of national infrastructure and utilities and draws on the ‘Infrastructure’ score of the GCI.

- Financial Market Underdevelopment: This is based on the ‘Financial Market Development’ score of the World Economic Forum’s GCI.

- Political Instability: This is based on the Political Stability Index provided by the website www.theglobaleconomy.com.

- Labor Market Inefficiency: This is based on the GCI ‘Labor Market Efficiency’ score.

- Construction Material Cost: This reflects the cost of construction materials in each country, using the cost of cement as a proxy.

.jpg?width=100&height=100&ext=.jpg)