Executive Summary

Long-running US-China trade tensions have spun off into a struggle over access to rare earth elements, thanks to their central role in a range of modern technologies, from EVs and wind turbines to a wide variety of electronic components. At present, China has a stranglehold on the market due to its control over the mining and processing of rare earth minerals, but the US is rushing to build partnerships and to agree MOUs as it tries to develop new supply chains that sidestep China, and Thailand now finds itself among these potential new partners. Thailand thus has the potential to develop an expanding role in the upstream processing and export of rare earth minerals, while domestic downstream industries would benefit from greater foreign direct investment in the production of rare earth alloys and magnets. Going forward, ongoing technological progress will boost demand further, and if Thailand is well positioned within these supply chains, benefits will naturally flow to the country. However, such a move would not be without costs, and developing a domestic rare earth industry will bring with it a higher risk that communities, society and the wider environment will have to carry the cost of a greater exposure to hazardous waste.

What are rare earth elements and why are they so central to the trade war?

Rare earth elements

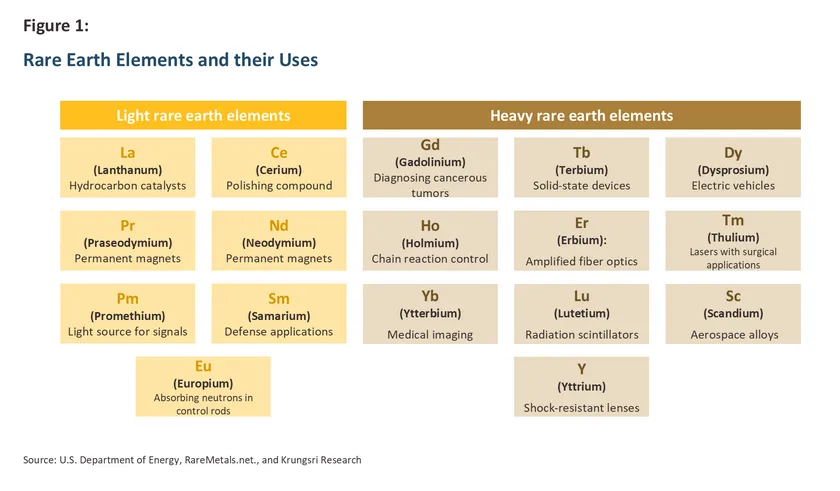

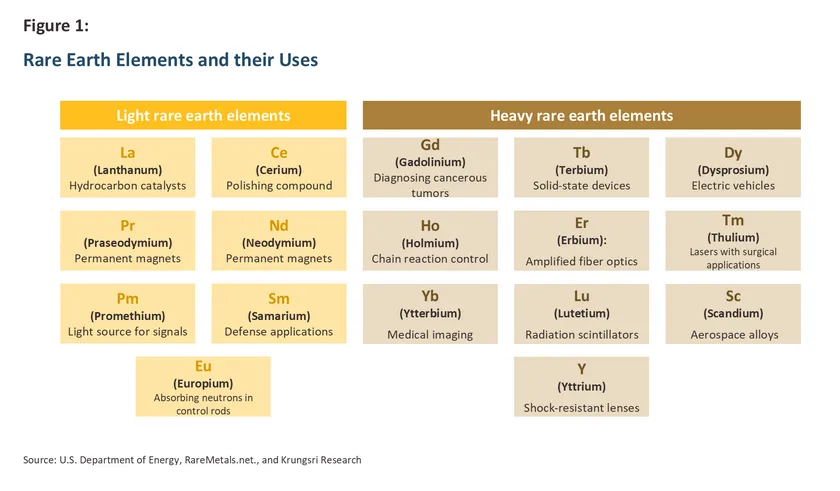

Rare earth elements (REEs) form a class of metals that are found in a wide variety of ores, but despite their name, REEs are in fact widely dispersed around the planet. Rather, their rarity comes from their low levels of concentration within these ores and the difficulties involved in extracting these in a pure form. The latter often entails the use of hazardous chemicals and so processing rare earth ores generates significant quantities of toxic waste. As such, production costs are generally high, and extraction and processing often results in major environmental impacts. Overall, REEs can be split into two main groups (Figure 1).

-

Light rare earth elements (LREEs): Examples of these include lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, and neodymium. These elements are found in locations around the world, and are easier than HREEs to extract from ores.

-

Heavy rare earth elements (HREEs): Examples of these include terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium. These are rarer and more difficult to process than LREEs, and production is concentrated in China and Myanmar.

Rare earth elements are key inputs into the production of many modern hi-tech goods, including electric vehicles (where they are used in high-performance electric motors made from permanent magnets), the machinery used in the generation of renewable power (in batteries and wind turbines), electronics parts (in semiconductors and screens for tablets and smartphones), medical devices (MRI machines), defense equipment (radar, guidance systems and missiles). Given this central role in both the economy and national security, nations around the world regard rare earth elements as strategically important resources.

Rare earth elements: A negotiating tool in the US-China trade war

Against the backdrop of extended US-China trade tensions, control over rare earth elements has become an important point of leverage since on the one hand, China has a dominant role in their extraction and processing, while on the other, the US is in the uncomfortable position of depending on Chinese exports of REEs. Needless to say, China has not shied away from exploiting this situation, and so on October 9, 2025, the Chinese authorities announced that export controls were being tightened on 12 rare earth elements and that henceforth, overseas sales of these would require official authorization1/. At the same time, the US responded with additional 100% tariffs on all imports from China as well as further restrictions on exports of some hi-tech products. However, some of the tensions that had built in US-China relations were released during negotiations held at the start of November, which ended in an agreement to suspend these moves for one year (i.e., until November 2026).

Although these negotiations have helped to temporarily ease the situation, the US remains keen to reduce its long-term dependency on China and to counterbalance Chinese power by developing supply chains that weaken its opponent’s current monopoly position. US officials are thus now attempting to develop relationships with alternative suppliers by rushing to sign MOUs and build partnerships with countries such as Australia, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand2/. The MOU agreed between Thailand and the US encompasses a framework for how the two countries should cooperate on developing processing technologies and evaluating the country’s potential as a source of rare earth elements3/. Thailand is therefore now in the position of seeing its involvement in these supply chains possibly grow substantially.

With these contests shaping much of the current trade environment, this paper aims to examine global rare earth supply chains, to assess Thailand’s place within these, and to evaluate the opportunities and challenges involved in developing its REE industry while the US-China trade war continues to rumble on.

Where does Thailand stand within global rare earth supply chains?

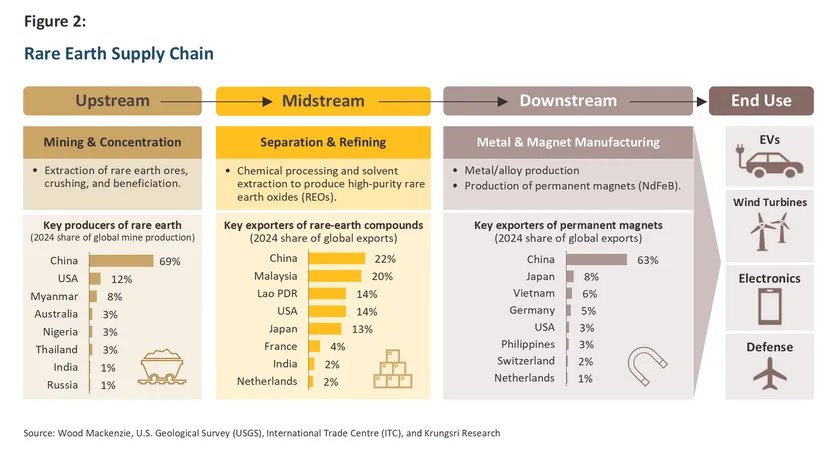

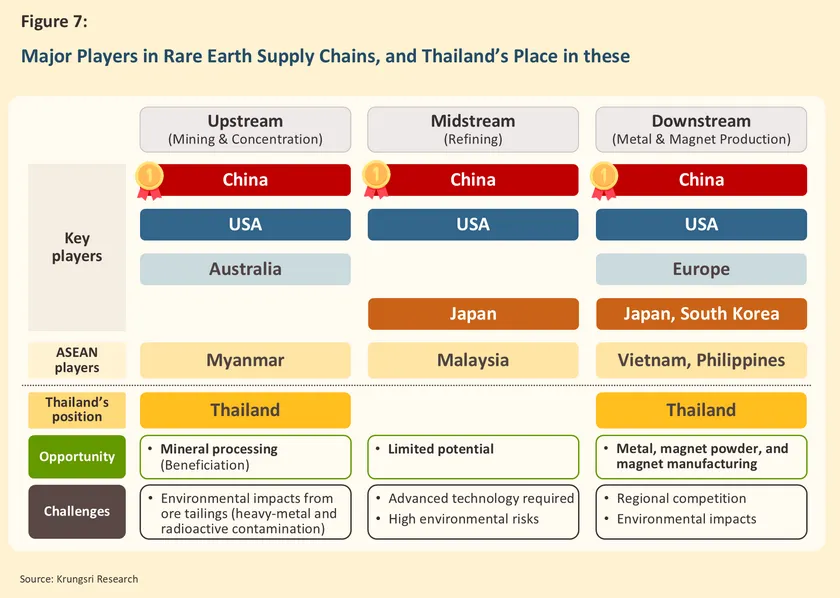

The rare earth supply chain begins with mining, extends through the separation and refining of the minerals that have been extracted, and ends with the production of metals, alloys and permanent magnets. China is the dominant player at every stage of this supply chain thanks to its possession of the world’s largest reserves of rare earth elements, though in addition, efforts by the government to integrate and accelerate the development of the REE supply chain date back to 1991 and the declaration of these as a strategic resource

4/. China Rare Earth Group and China Northern Rare Earth are the country’s most important players, with ongoing support from the government. On the other side of the Pacific, the US is now attempting to balance China’s undoubted power with an expansion in production capacity and the forging of new partnerships, while ASEAN member states have a range of roles to play across upstream and downstream production (Figure 2).

Details of the global rare earth supply chain are given below.

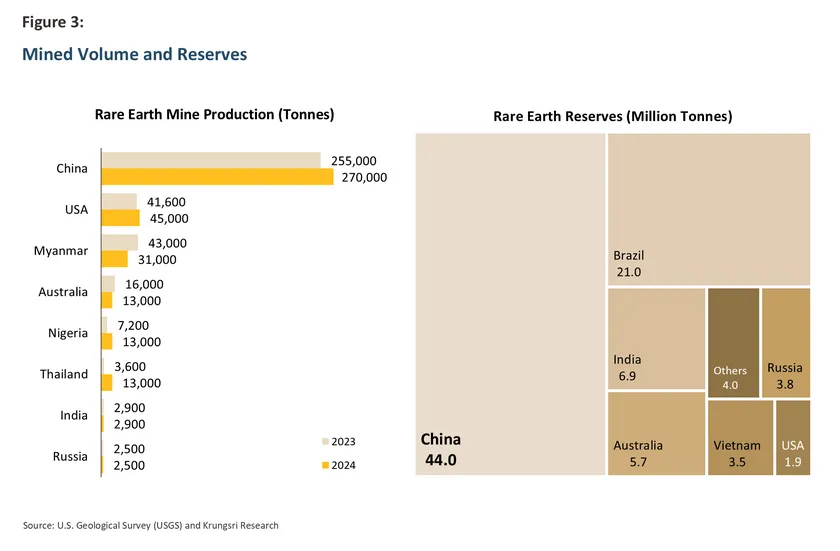

Upstream extraction: Mining

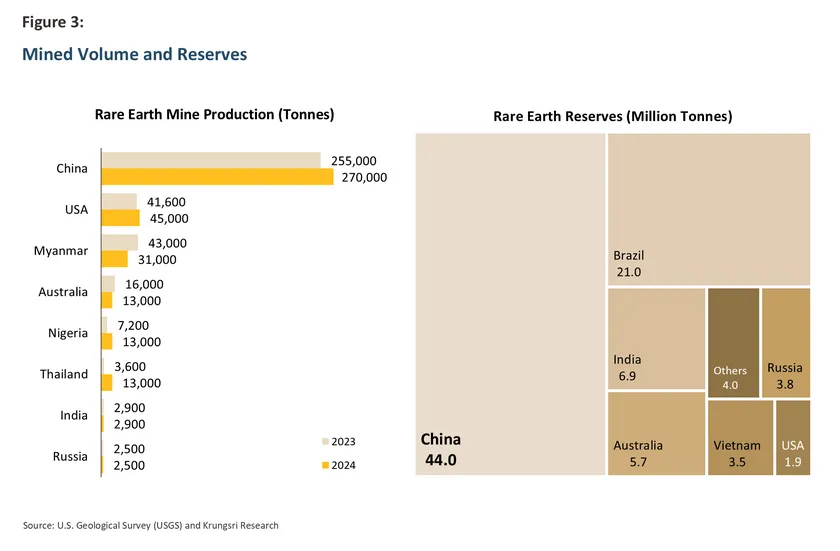

The rare earth supply chain originates with the upstream mining of ores such as bastnaesite and monazite that contain these elements, and these are then processed into mineral concentrate. Data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) show that in 2024, China was the world leader in rare earth mining, and so with an output of 270,000 tonnes5/, the country accounted for 70% of global production. China was followed in importance by the US (output of 45,000 tonnes), Myanmar (31,000 tonnes) and in fourth place, Thailand (13,000 tonnes), Australia and Nigeria. China’s dominance is also reflected in the size of its reserves, which at 44 million tonnes are the largest in the world. Some way behind China is Brazil (21 million tonnes), India (6.9 million tonnes), Australia (5.7 million tonnes), Russia (3.8 million tonnes) and Vietnam (3.5 million tonnes). By contrast, the US must content itself with reserves of just 1.9 million tonnes6/ (Figure 3).

Where does Thailand stand? Currently, there is no commercial mining of rare earth minerals in Thailand, though domestic companies are involved in ‘beneficiation’, that is, mined products are imported and processed to separate ores containing rare earth-bearing minerals from other rocks. These more concentrated products are then exported to countries that are able to refine these further7/. These activities were sufficiently large for the USGS to rank Thailand as the world’s 4th most important source of rare earth products (as of 2024), although in terms of reserves, the country’s 4,500 tonnes are only enough to warrant 12th place. The most important domestic players are Sakorn Minerals in Prachuap Khiri Khan and Ratanarungsiwat in Pang Nga8/.

Midstream processing: Separation and refining

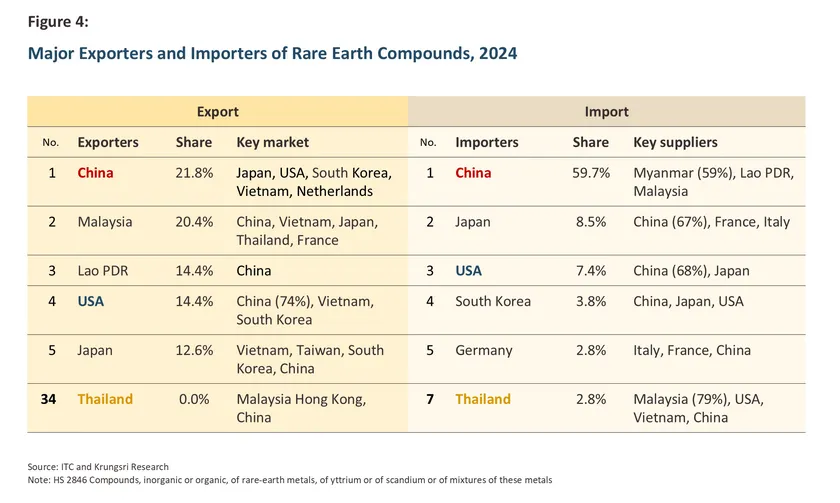

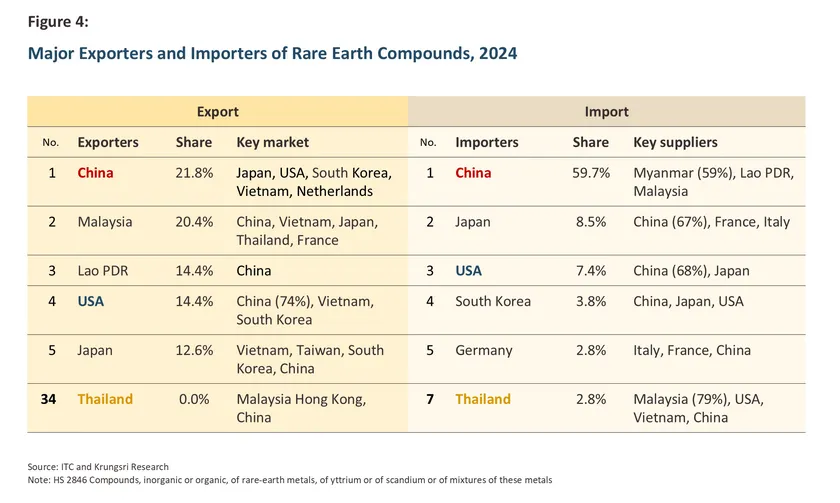

The mineral concentrates obtained from mining are then subjected to additional chemical processing to produce purified rare earth metal compounds or rare earth oxides (REOs). These are then used as inputs into the downstream production of metals and magnets, and due to the technological complexity of these processes, these are regarded as high-value-added activities. China dominates this market and its 80-90% share of global manufacturing capacity9/ ensures that it is comfortably the world’s biggest exporter. On the demand side, countries with extensive hi-tech manufacturing industries such as the US, Japan and South Korea are heavily dependent on sourcing goods from China (Figure 4), although Malaysia is emerging as a major player and the country is now the world’s 2nd most important exporter of rare earth compounds. Malaysian production is driven by the Australian company Lynas Rare Earths, which opened its first Malaysian production facility in 201210/, and since 2014, the country has been the world’s leading exporter of REOs. The US comes after China and Malaysia in the global rankings, selling mainly to China, Vietnam and South Korea, though the country is now accelerating the expansion of its domestic production capacity; as part of this, Lynas Rare Earths is opening a processing facility in Texas, with commercial operations due to begin in 2026.

Where does Thailand stand? Thailand currently lacks commercial midstream processing facilities. The country is thus reliant on the import of intermediate goods for processing by downstream industries into metals and magnets.

Downstream manufacturing: Production of metals and magnets

At this stage of the supply chain, rare earth chemical compounds, including rare earth oxides, are transformed into metals and alloys that are then used to manufacture very powerful permanent magnets, such as those made from neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB). These play a central role in the manufacture of many goods including EV motors, wind turbines, and smartphones.

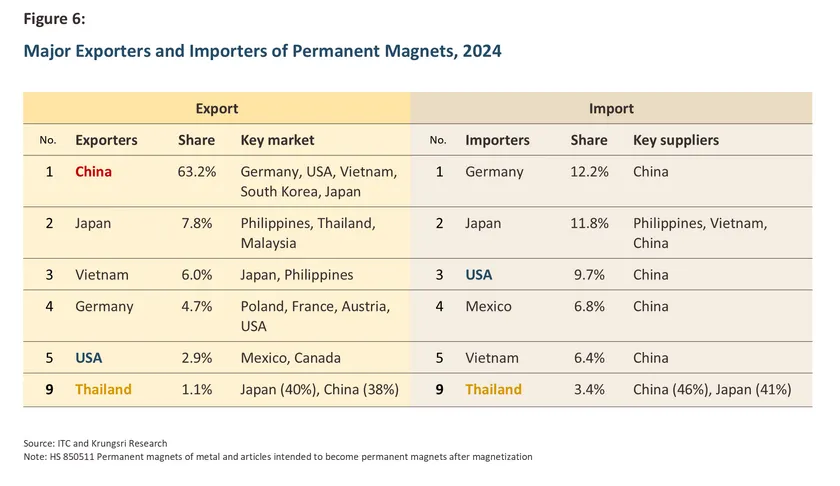

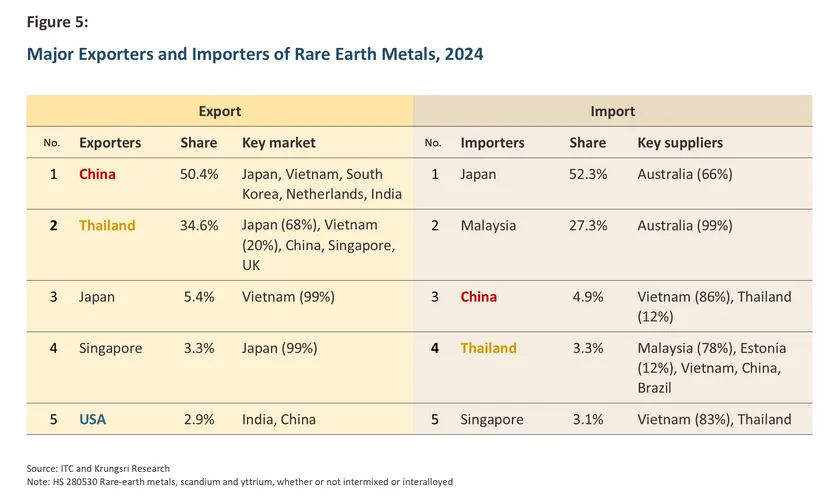

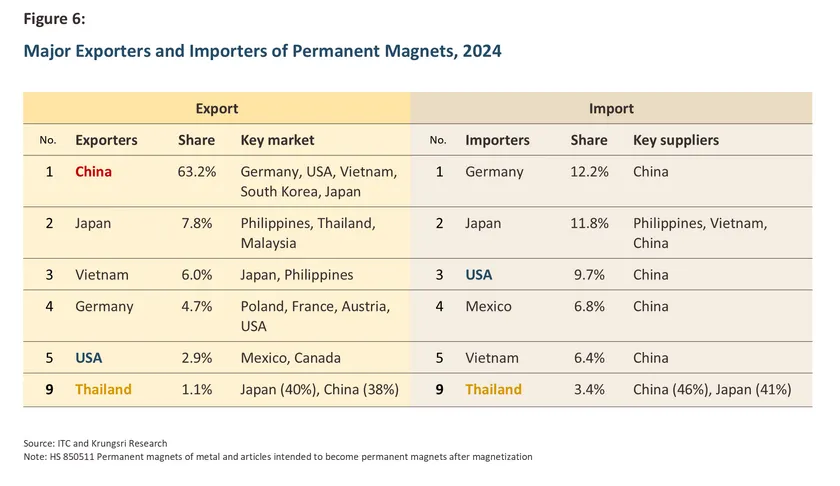

China controls most of the world’s production capacity for permanent magnets and as a result, it has a 63% share of global exports. Japanese suppliers (e.g., Proterial11/) are in second place, followed by Vietnam (e.g., Shin-Etsu Chemical), Germany (e.g., Vacuumschmelze) and the US (e.g., MP Materials), though combined, these have a market share of just 20% and so countries with significant EV, electronics, and wind power industries are dependent on imports from China. Nevertheless, China is facing increasing competition from companies in the US, Australia, Canada, Japan and South Korea, which are expanding production facilities in many countries, including in the ASEAN region.

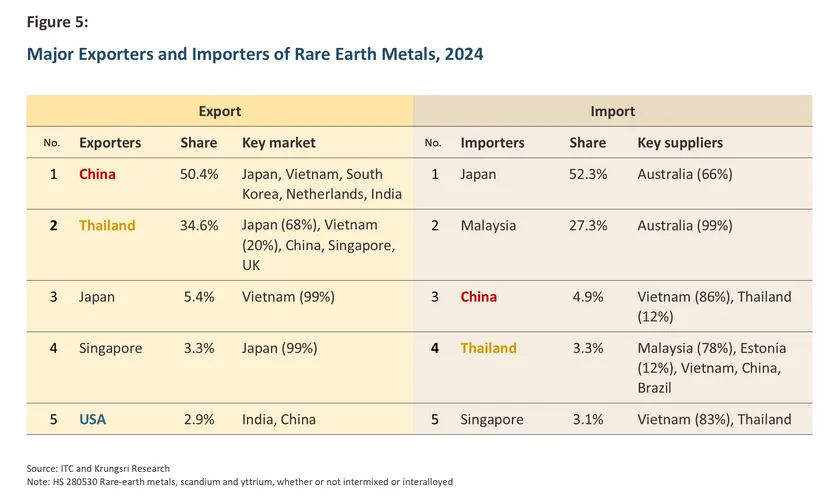

Where does Thailand stand? Trade data suggest that Thailand imports intermediate rare earth goods for use in the production of metals and magnets, which are then either consumed domestically or exported. In 2024, Thailand spent USD 64.4 million on imports of rare earth compounds (HS284612/), making it the world’s 7th largest market for these, and almost 80% of these goods came from Malaysia, which was followed in importance by the US, Vietnam and China (Figure 4). Exports of rare earth metals (HS 28053013/) came to USD 65.9 million, giving Thailand a one-third market share and putting it 2nd in the global rankings after China. Some 70% of these exports went to Japan, with the majority of the remainder going to Vietnam, China and Singapore (Figure 5). In addition, Thailand is also the 4th biggest global importer of rare earth metals (a key input into the production of permanent magnets), sourcing goods from Malaysia (78%), Estonia14/, Vietnam, and China. Most recently, exports of permanent magnets generated receipts worth USD 55.5 million, and Thailand’s 1.1% market share makes it the 9th most important supplier of these to global markets. The country sells principally to Japan (a 40% market share) and China (38%) (Figure 6).

The most important domestic player is Magnequench (Korat), which is based in Nakhon Ratchasima and that manufactures magnetic powder. This is a subsidiary of the Canadian company Neo Performance Materials, a world-leading manufacturer of magnets, though Magnequench is their only ASEAN manufacturing facility.

In summary, official data and surveys show that Thailand has only limited involvement in midstream activities in rare earth supply chains, partly because these are technologically intensive processes and partly because the country has not benefited from large-scale FDI into these segments. However, Thailand is playing an increasingly significant role in both the upstream and downstream industries, relying on the import of raw ores and refined rare earth elements for domestic value-added processing, while benefiting from foreign direct investment.

Krungsri Research view: Opportunities and threats for Thailand in the battle for rare earths

Rare earth elements are scarce, yet are essential for future industries such as EVs, technology and clean energy, and McKinsey & Company thus sees the demand for rare earth elements for use in the production of magnets expanding three-fold between 2022 and 203515/. As shown above, China has a firm hold over the industry and across the length of global supply chains, the country controls at least half of the world’s manufacturing capacity. Nevertheless, the advanced economies of the US, Europe, South Korea and Japan are now attempting to reduce their reliance on Chinese suppliers and to this end, these countries are looking to expand production facilities in the ASEAN region, including in Thailand. As described earlier, Thailand already has a presence in upstream and downstream sections of this supply chain and so the question now is whether, under pressure from the intensifying struggle for access to rare earth elements, it should expand its involvement in these areas.

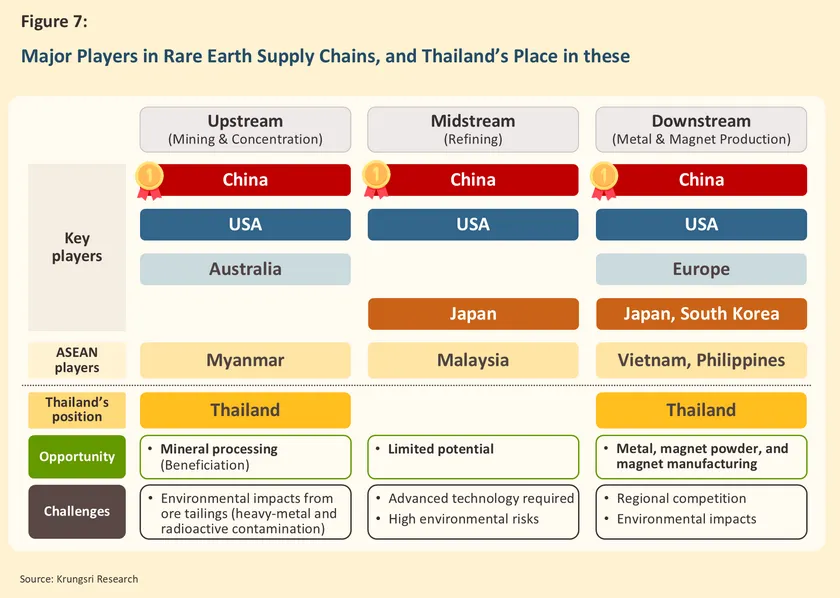

Answering this question requires recognizing that developing the rare earth industry is potentially a double-edged sword, and while undoubted global growth in clean-energy and tech-heavy industries will mean that deeper involvement in rare earth supply chains will open up new opportunities for growth, processing rare earth elements often entails the use of industrial processes that result in air pollution and the contamination of land and water resources with chemicals, heavy metals, and other toxic byproducts. Krungsri Research therefore sees that Thailand’s opportunities and challenges in the rare earth industry vary across different segments of the supply chain, and policymakers and businesses will need to be alert to these differences and carefully balance the wider benefits and risks that come with deeper engagement in these trends (Figure 7).

-

Upstream extraction: Over the short term, Thailand will continue to benefit from its beneficiation industries and the generation of added value from the import of ores for processing, concentrating and re-export. With major economic powers competing to develop their own rare earth industries, Thailand will also gain from its position as a supplier of upstream inputs to countries that are able to process these into refined rare earth elements. However, beneficiation can generate significant environmental impacts, including pollution from heavy metals and radioactive elements present in the waste generated by these processes. To this can be added air pollution resulting from the grinding and separation of minerals. In terms of developing a domestic rare earth mining industry, which requires long-term investment, Thailand needs to further explore the potential of its rare earth deposits to assess the commercial viability of mining. Preliminary data from the USGS, however, indicate that the country’s reserves remain limited, and work by the Department of Mineral Resources shows that these are concentrated in the west of the country in Chiang Rai, Mae Hong Son, Chiang Mai, Uthai Thani, Kanchanaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Chumphon, Ranong, Pang Nga, and Surat Thani16/. The authorities thus need to make a careful assessment of the likely social and environmental impacts of any moves in this direction, though it would be wise to heed the lessons from Myanmar, where the mining of rare earth elements in Shan state resulted in arsenic levels rising beyond safe levels in the Kok and Sai rivers, thereby impacting the health of riverine communities in both Myanmar and Thailand.

-

Midstream processing: Opportunities in this area are limited by the fact that processing rare earth minerals involves advanced technology that is currently not in commercial use within Thailand. At the same time, investments by the Australian company Lynas Rare Earths in Malaysia mean that it is one of the global leaders in this area. However, it should be noted that although midstream processing offers opportunities to generate significant added value, the environmental and social impacts can be equally high. Thus, a rare earth processing facility in Pahang state in Malaysia faced substantial local opposition and as a result, the government ordered the operators to build an additional facility to process waste and to ensure that the release of radioactivity was kept within safe limits17/. Likewise, operations at a processing facility in Baotou in Inner Mongolia, China have resulted in widespread contamination of the local area with cadmium and lead, exposure to which affects the nervous and respiratory systems and can result in developmental problems in children.

-

Downstream manufacturing: Opportunities exist for Thailand to attract greater investment from overseas manufacturers of rare earth magnets. Demand for the latter will come especially from downstream industries already operating in Thailand, which in the case of EVs include BYD and Great Wall Motor (GWM) and Western Digital and Seagate Technology in electronics production. Greater investment in these downstream rare earth industries would help to strengthen competitiveness across domestic hi-tech supply chains as Thailand is a net importer of permanent magnets and as of 2024, 46% of these (by value) were sourced from China and 41% from Japan. However, moves in this area will have to overcome competition from within the wider region since many other ASEAN countries are likewise attempting to pull in additional investment inflows from advanced economies looking to expand their own production of permanent magnets. Thus, Malaysia, which is already home to an Australian processor of rare earth elements, is moving into the production of magnets18/, while Vietnam, which benefits from sizeable reserves of rare earth elements, is also home to manufacturing plants producing permanent magnets operated by Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean companies19/. Moreover, as with other parts of the supply chain, the manufacture of rare earth metals and permanent magnets also entails the risk of negative environmental impacts via the heavy metals that may be found in industrial waste, and ensuring that these do not contaminate soil and water would require the rollout and enforcement of effective waste-management processes.

With major economic powers competing over rare earth supply chains, Thailand is being presented with a way to develop its own rare earth industry, which it can achieve by attracting foreign investment and supporting the domestic exploration and development of rare earth resources. Moreover, although Thailand will face strong competition from other ASEAN nations looking to tread the same path, the country should be able to overcome these problems through greater regional cooperation. Nevertheless, any decision on how to proceed will need to be made only after a careful and comprehensive analysis of the trade-offs between the likely economic benefits and environmental impacts. And any decision to develop the domestic rare earth supply chain will need to be coupled with the enforcement of strong, effective and transparent environmental measures that are able to protect communities, society, and Thailand’s commitment to long-term sustainability.

1/ China placed controls on the export of 7 REEs in April 2025.

2/ U.S. secures rare earths and trade deals in Southeast Asia amid China supply concerns | NewsTarget

3/ Thailand and the US sign their first rare earth MOU as they look to develop new supply chains | iGreen

4/ China’s Rare-Earth Empire: A 30-Year Playbook of Strategy and Dominance | Timesnownews.com

5/ Output from mining is measured in rare-earth-oxide (REO) equivalent.

6/ U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2025 | USGS

7/ USGS data on imports to China implies that most Thai exports are to China, where it is processed and refined further.

8/ Rare Earth Imports to Thailand | Bangkokbiznews

9/ Rare Earth Processing 2025 - Global Capacity and Key Players | Rare Earth Exchanges

10/ Lynas Rare Earths imports mineral concentrates from Australian mines for processing in Malaysia.

11/ Previously called Hitachi Metals.

12/ HS 2846 Compounds, inorganic or organic, of rare-earth metals, of yttrium or of scandium or of mixtures of these metals

13/ HS 280530 Rare-earth metals, scandium and yttrium, whether or not intermixed or interalloyed

14/ Believed to be imports from a company in the Neo Performance Materials group that is based in Estonia.

15/ Powering the energy transition’s motor: Circular rare earth elements | McKinsey & Company

16/ Rare earth elements may be found in tin and tungsten deposits, and so the former can be extracted as a byproduct of processing of the latter (Get to Know ‘Rare Earth Minerals’ – Rare Minerals Found in Several Provinces of Thailand | Department of Mineral Resources and Rare earth elements | Facebook Department of Mineral Resources)

17/ Malaysia's rare earths ambition: Lynas expands operations | The Straits Times | The Straits Times

18/ Malaysia aims to become a major player in global rare earth supply chains by 2030. This will involve the development of midstream and downstream industries, including the manufacturing of magnets and the recycling of rare earth elements.

19/ For example, Star Group (South Korea's Star Group to Launch $80 Million Magnet Factory in Vietnam | Rare Earth Exchanges)