Introduction

Even though the Thai economy has started to recover from the COVID-19 crisis for some time, household spending in Thailand has been slow and remains sluggish. Krungsri Research found that after the COVID-19 crisis, the average liquid assets and fixed assets used as collateral for loans by households have increased very little and have even decreased in certain household groups. Meanwhile, financial assets for investment have decreased in almost all income groups. At the same time, household debt and the burden of debt repayment remain high, and credit risk is at a worrying level. These indicators serve as warning signs, reinforcing financial vulnerability and acting as a major factor contributing to weak domestic spending.

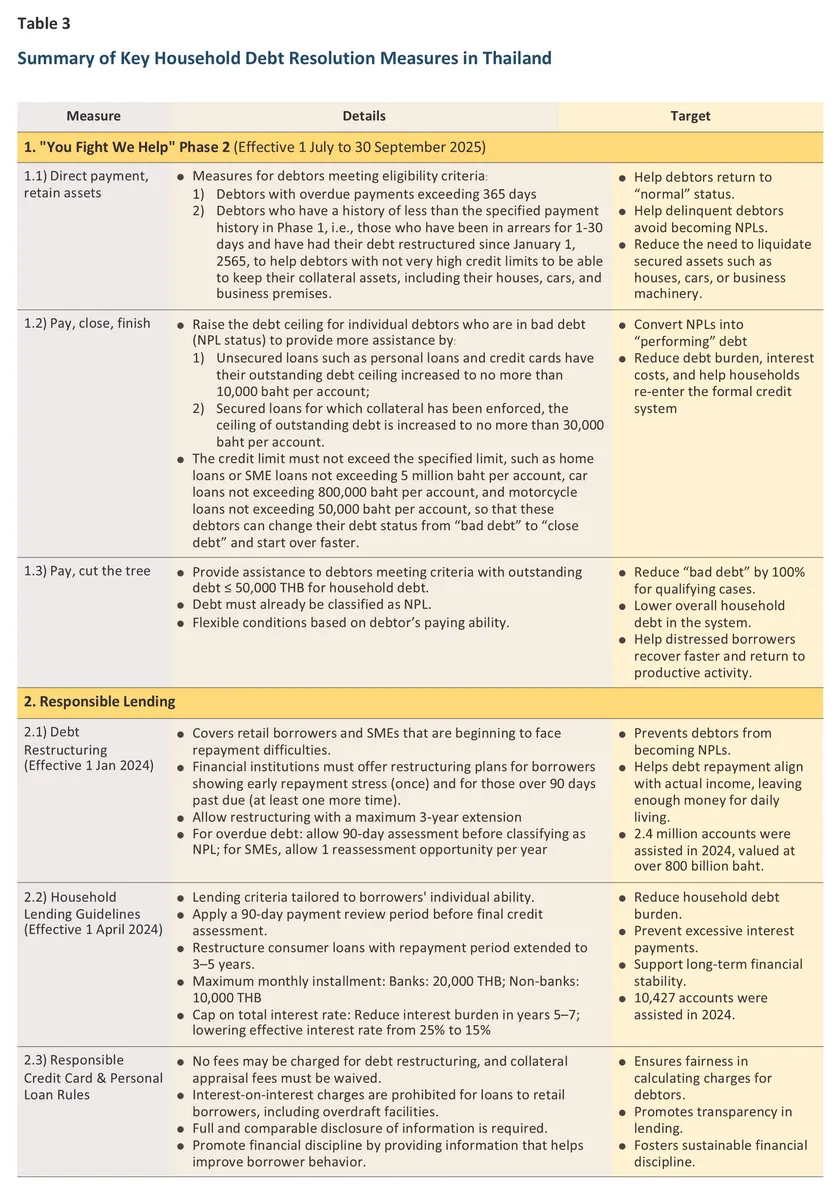

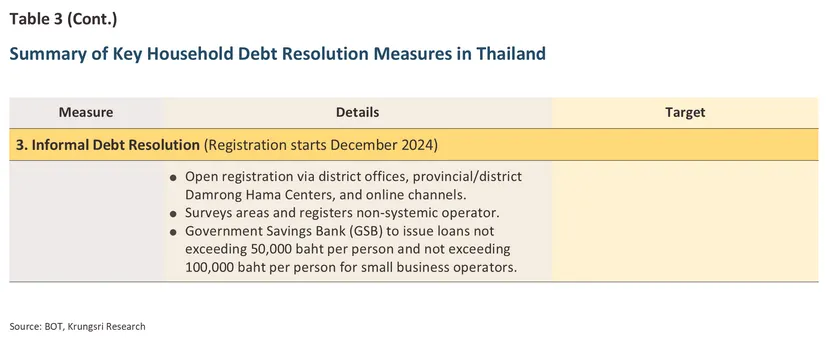

Although the government and the Bank of Thailand (BOT) have implemented assistance measures, including debt restructuring, interest burden relief, and informal debt management, most of these focus on mitigating the impact of existing debt problems. Therefore, a more effective solution would be to urgently address the root causes, such as insufficient income and unstable employment, which would help strengthen the financial status of households. This would allow household spending to become an economic engine that drives Thailand's economy to grow to its full potential.

Thai Household Liquid Assets: Stuttering Growth

Even as the Thai economy gradually recovers from the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, evidenced by a continuously falling unemployment rate, this momentum is insufficient to stimulate robust growth in household consumption. Over the past 3-4 years, household spending has remained low and sluggish, partly due to high household debt levels and debt servicing burdens that limit spending potential. The fragility of purchasing power may also reflect other structural factors, including income, job stability, and household assets not increasing in line with expenses, which affects consumer confidence and prevents its full recovery.

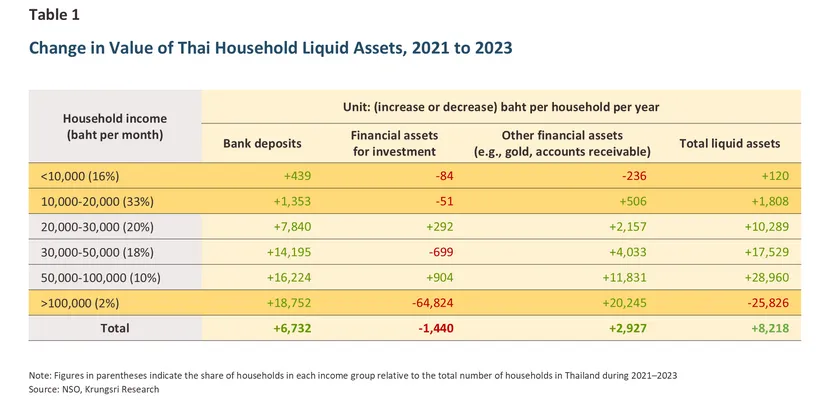

The latest survey results from the National Statistical Office (NSO) between 2021–2023 show that liquid assets of Thai households

1/ in the post-COVID-19 period increased very little, averaging only 8,218 baht per household per year (Table 1). Various asset types reflect weak purchasing power:

-

Bank Deposits: Increased by only 6,732 baht per household per year, which is minimal compared to the continuously rising cost of living.

-

Financial Assets for Investment (e.g., debentures, mutual funds, and bonds): Decreased in value by an average of -1,440 baht per household per year. This decrease was seen across almost all income groups, particularly in the highest income group (above 100,000 baht per month, which is about 2% of all Thai households) where it dropped by as much as -64,824 baht per household per year. This is attributed to the slowing Thai economy, reduced confidence, and the overall significant decline in Thai stock prices.2/

-

Overall Liquid Assets: For the group of households with income below 20,000 baht per month, which accounts for nearly half (about 49%) of all Thai households, the increase was less than 2,000 baht per household per year.

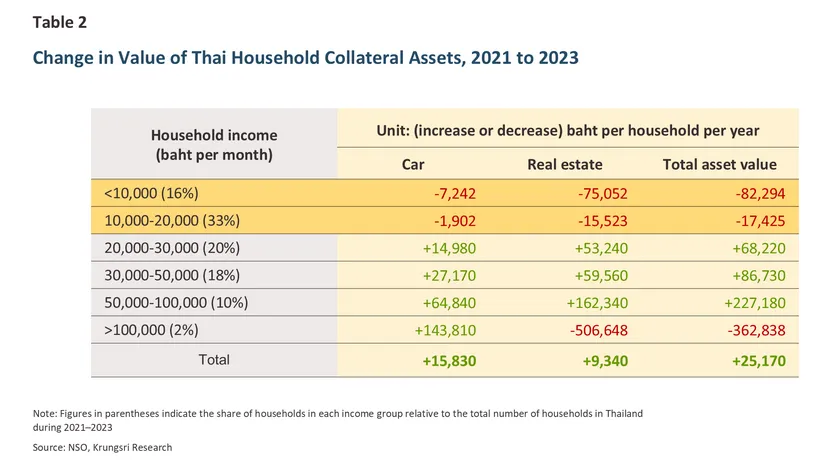

Fixed Assets: Vulnerability of Low-Income Households and the Problem of Lacking a Financial Buffer

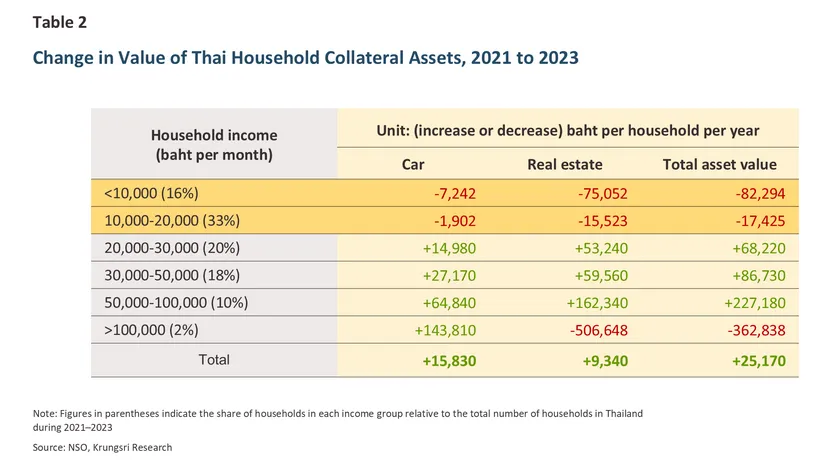

In addition to the minimal increase in liquid assets, an analysis of other asset types, particularly fixed assets—which are a measure of household wealth and can be used as loan collateral (i.e., real estate like houses and land, and cars)—shows that their value has also decreased.

-

Low-income households: For households with income below 10,000 baht per month, the value of real estate and cars decreased by -82,294 baht per household per year. For the group with income between 10,000-20,000 baht per month (33% of all households), the value of these assets decreased by over -17,425 baht per household per year.

-

High-income households: For households with income more than 100,000 baht per month (only 2% of Thai households), the value of real estate holdings significantly decreased by -506,648 baht per household per year. However, the value of cars for this group increased by 143,810 baht per household per year.

However, middle-income households earning between 20,000 and 100,000 baht per month—accounting for 48% of Thai households—continue to exhibit solid wealth levels, as measured by asset holdings. On average, their real estate and vehicle assets increased by 382,130 baht per household per year.

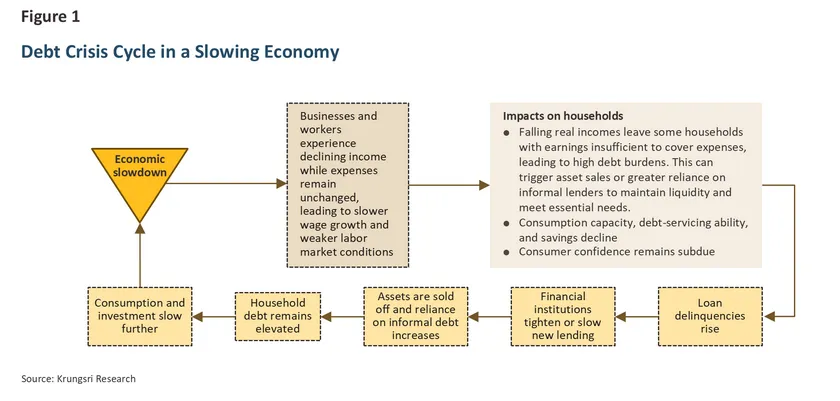

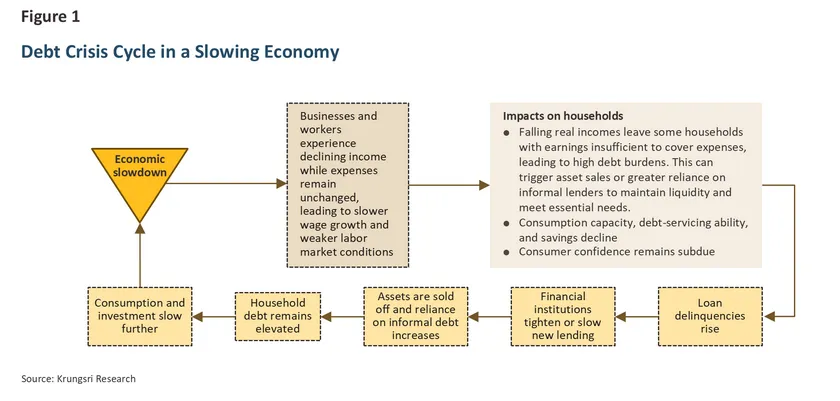

When liquid assets barely increase and fixed assets decrease, household wealth declines. This is especially for the low-income group, who are facing deep-rooted structural problems in the Thai economy: insufficient income for expenses, high debt burdens, and a subdue economic growth. The decrease in assets reduces purchasing power due to the Wealth Effect. When assets—an indicator of wealth—grow slowly, consumers feel insecure and postpone spending, leading to a slowdown in macro-level private consumption, creating a difficult debt cycle to escape. The decline in fixed assets also makes it harder for households to access credit because they have less property to use as collateral.

Furthermore, it indicates a lack of "Financial Buffer" or reserve funds to manage risks. If this situation continues, it could lead to a more severe and expanding debt crisis cycle3/ in the future.

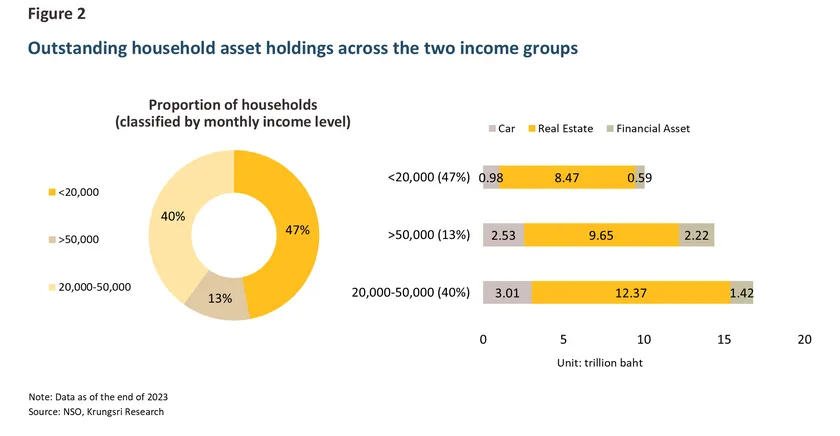

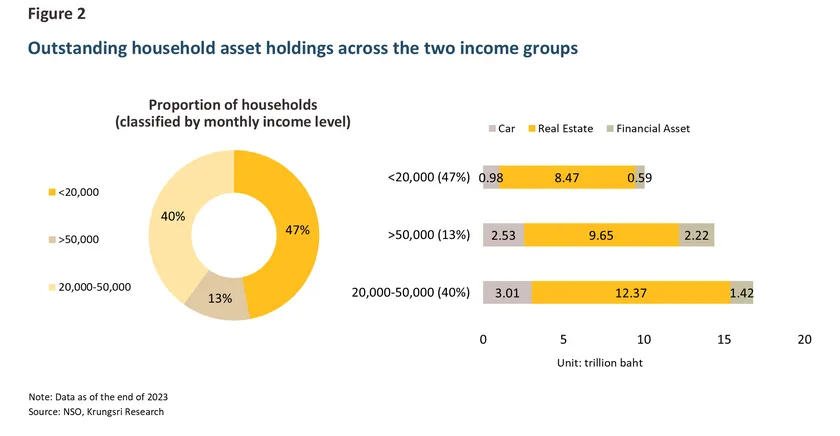

The data also reveals a high level of inequality in asset holdings. Households with income above 50,000 baht per month (only 12% of total households) hold a combined value of real estate, cars, and financial assets totaling 14.4 trillion baht (or 35% of total asset value). In contrast, households with income below 20,000 baht per month (a substantial 49% of all Thai households) hold a combined value of these assets totaling only 10 trillion baht (or 24% of total asset value).

These indicators reflect that low-income households have a high level of financial vulnerability and limited financial buffers if they face economic volatility or increased debt burdens in the future. The decline in asset value for this group further exacerbates their financial status and may lead to a delayed recovery in spending.

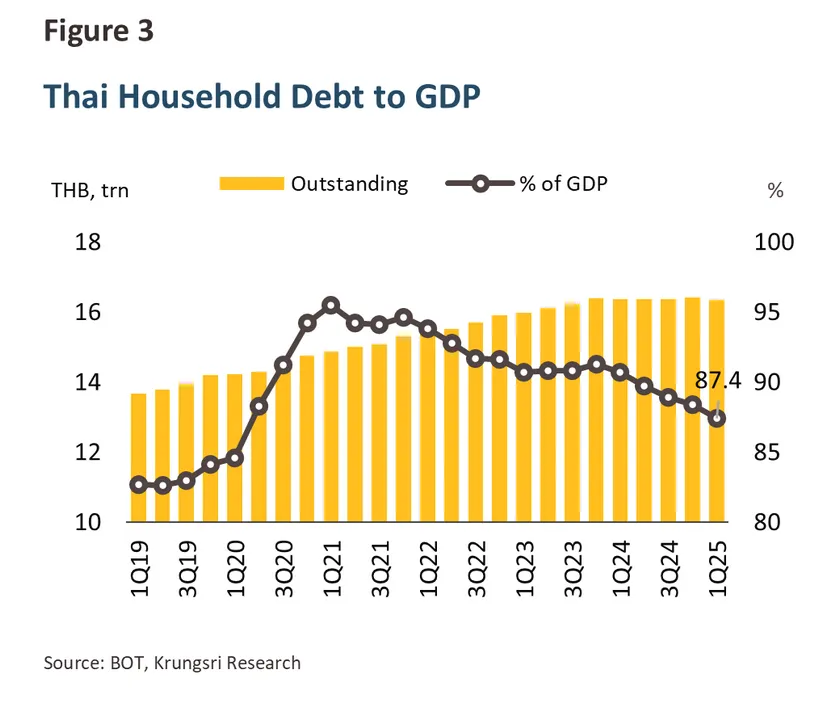

Household Debt Situation and Credit Risk

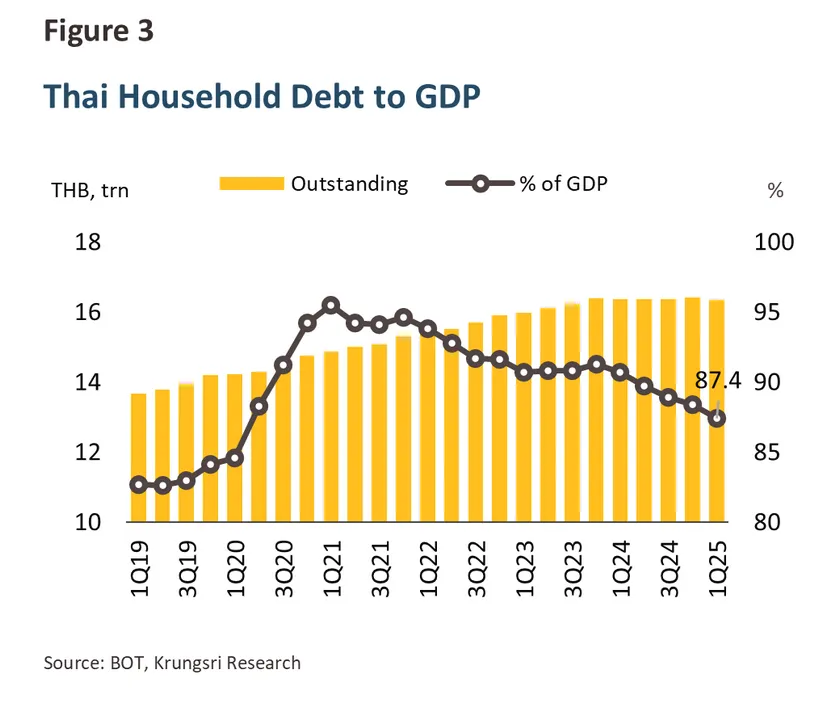

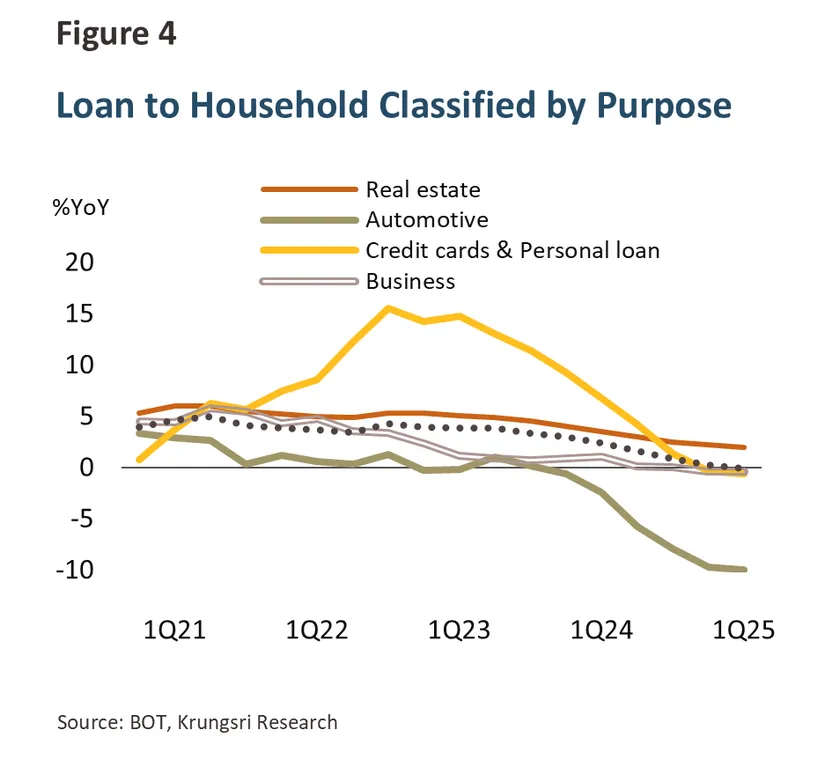

Amid rising financial fragility and weakened asset positions among households, household debt remains another key factor weighing on consumption. According to the latest data from the Bank of Thailand (BOT), as of Q1 2025, Thai household debt stood at 16.35 trillion-baht, equivalent to 87.4% of GDP. Although this is the lowest ratio in five years, it remains relatively high.

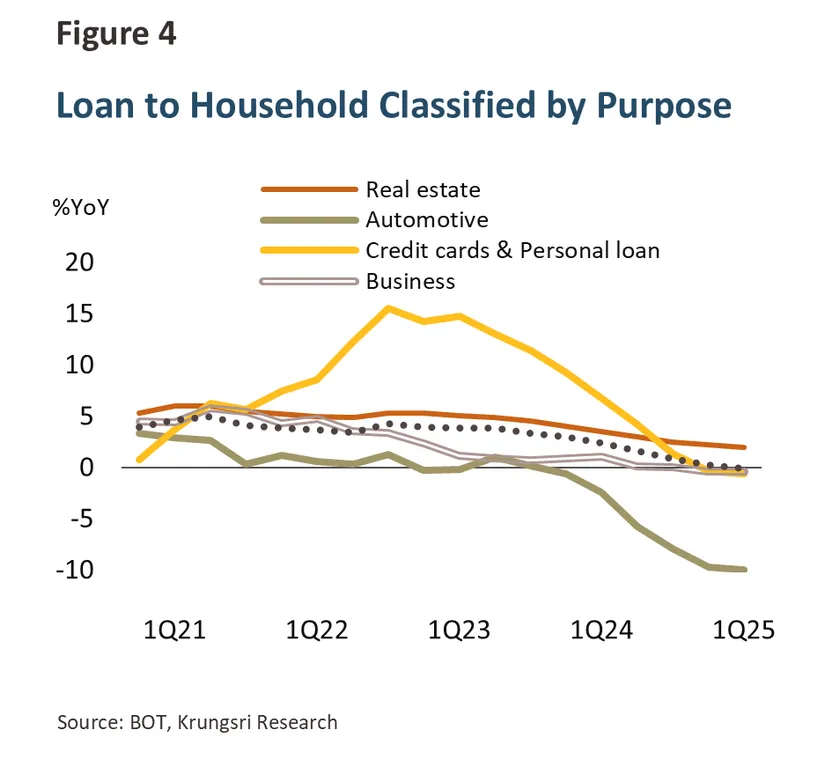

The main reasons decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio are debt repayments and a contraction in lending. Household loans at the end of Q1 2025 fell by -0.12% YoY, reflecting tighter credit conditions as financial institutions remain cautious in issuing new loans due to persistently high credit risks.

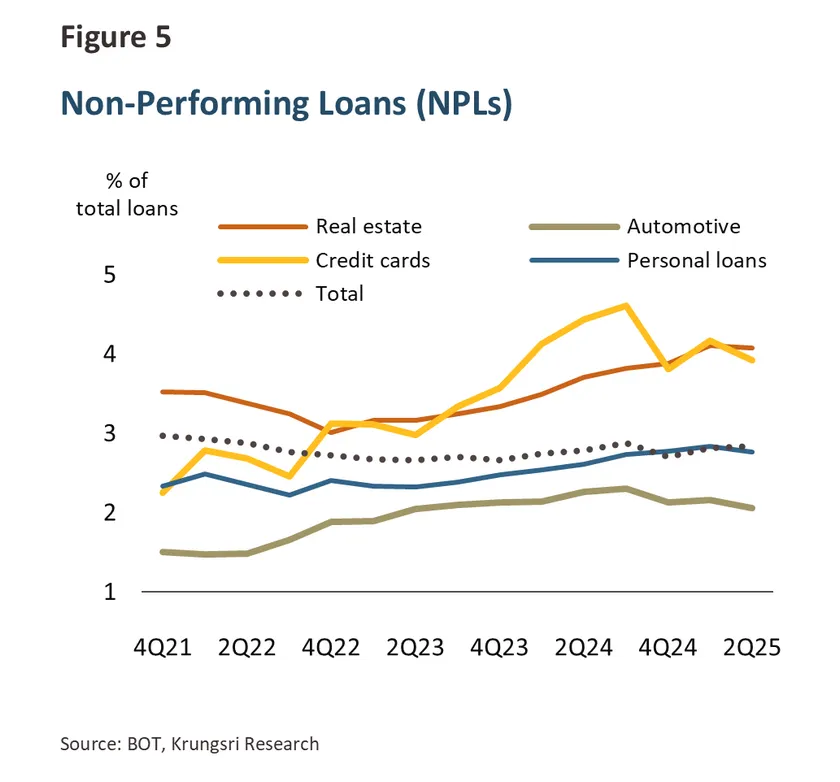

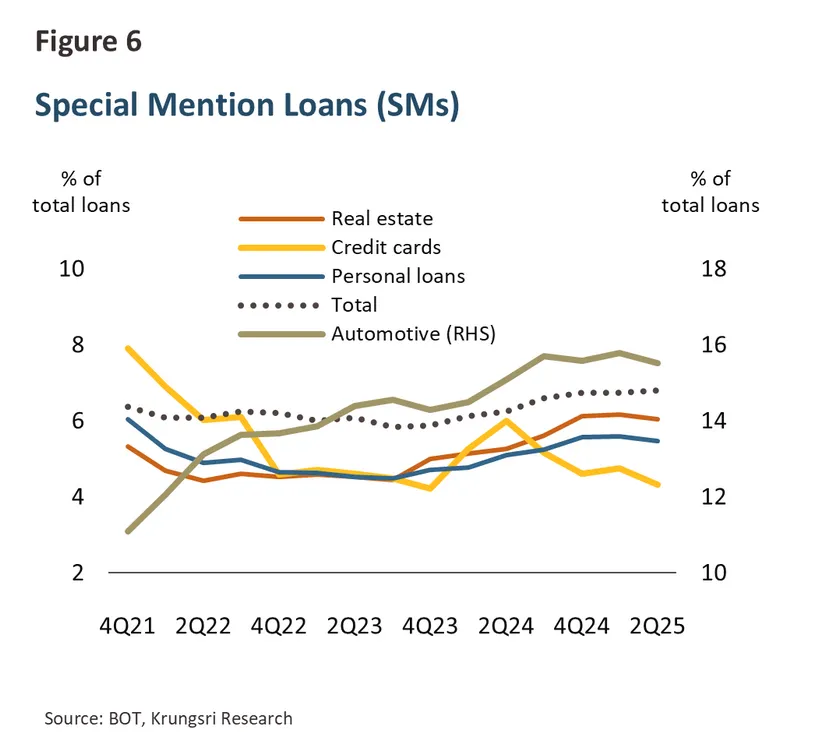

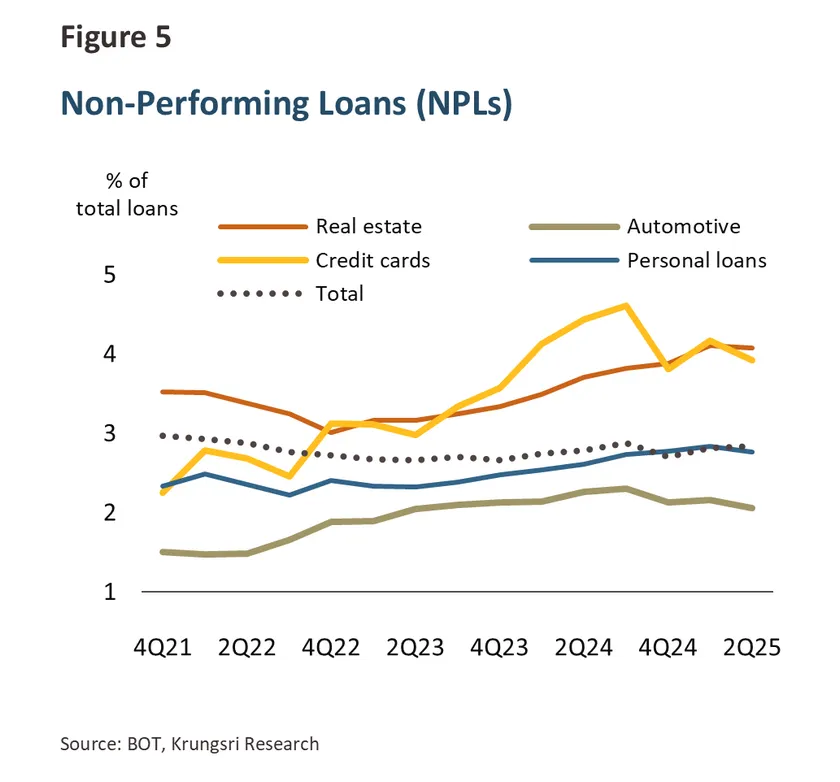

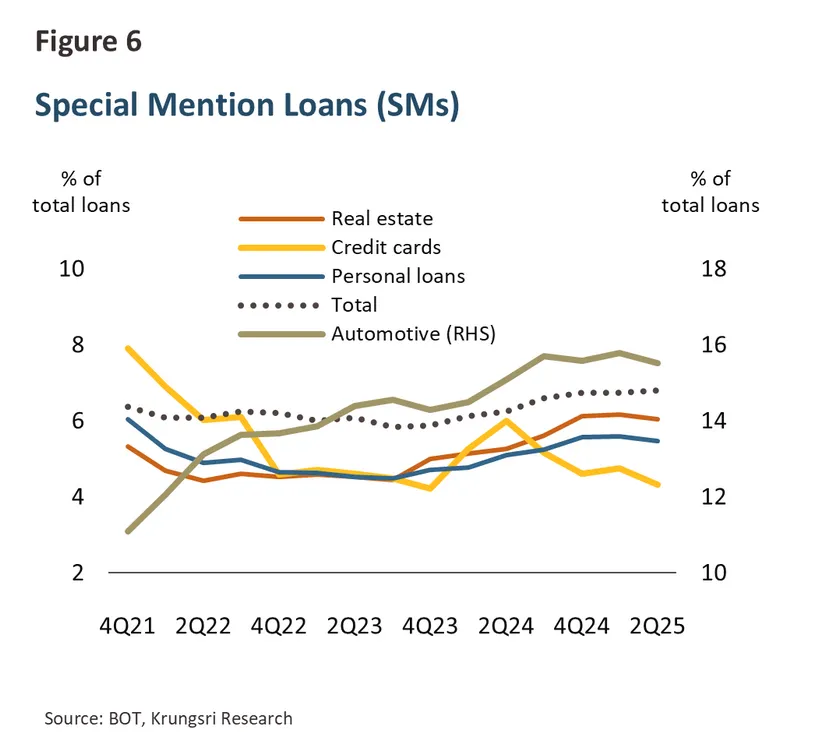

Credit risk continues to be a concern and has led banks to remain strict in extending new credit4/. Although the ratios of non-performing loans (NPLs)5/ and special-mention loans (SMs)6/ saw a slight decline in Q2 2025, they remain elevated across several loan categories. The BOT also noted that it must closely monitor the debt-servicing capacity of vulnerable borrowers, as Thailand’s current household-debt level remains above the sustainable threshold of 80% set by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and is the highest among Southeast Asian countries.

Limitations of Current Debt Resolution Measures

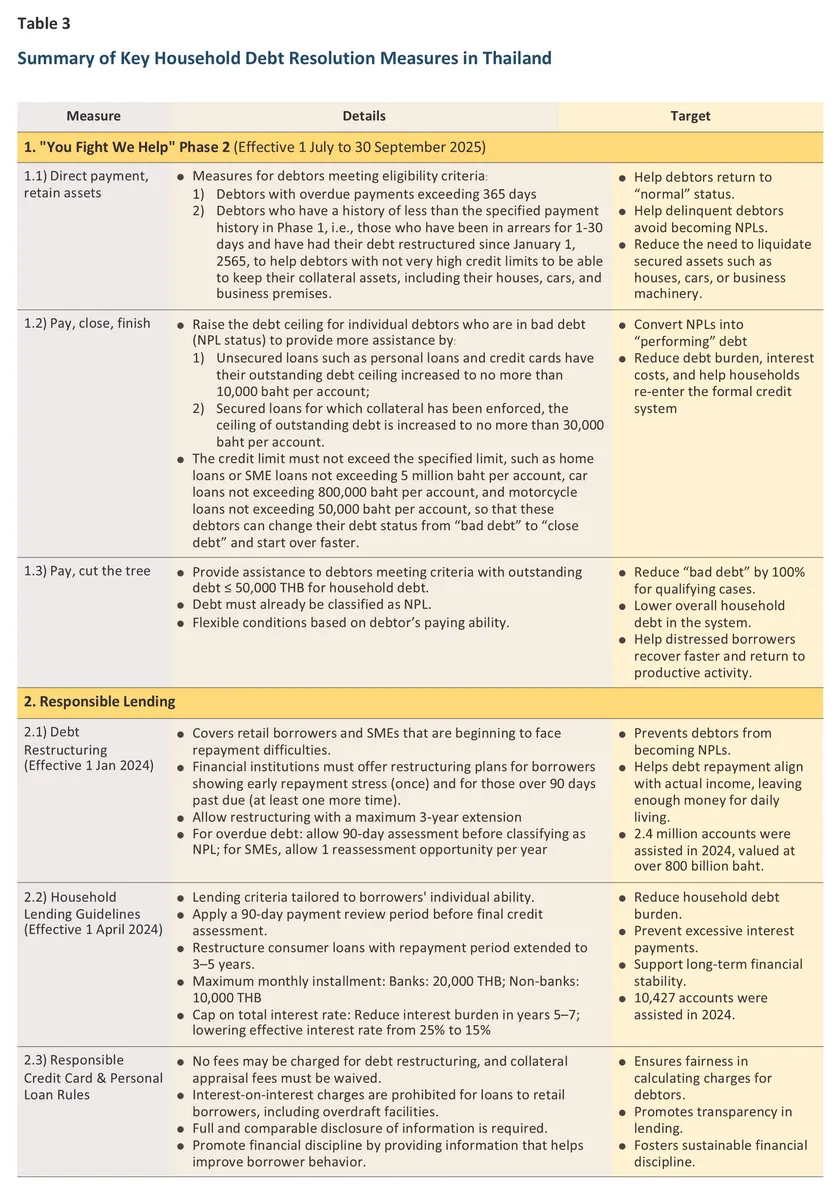

To address the complexity of Thailand’s household-debt problem, the government and the Bank of Thailand (BOT) have introduced a range of preventive and corrective measures. However, the implementation of these measures still faces several limitations that may undermine their long-term effectiveness and sustainability.

A key limitation is the behavior of taking on new debt. Measures such as debt moratoriums or interest-payment freezes can provide short-term relief but may also create moral hazard7/. Some borrowers may come to expect repeated assistance and thus fail to improve their financial structure or change their financial behavior. In addition, interest often continues to accrue during the moratorium period, potentially accumulating into a heavy burden once payments resume, pushing some borrowers back into a debt cycle.

The second issue relates to the coverage of target groups. Assistance programs, such as the “Khun Su, Rao Chuay” (You Fight, We Help) initiative, may not fully reach all borrowers—particularly those with previously good repayment histories who are now facing reduced income. These borrowers are still classified as having sufficient creditworthiness to access formal credit and therefore may not qualify for support under such schemes.

Another important challenge is the problem of informal debt. Efforts to address this issue face difficulty in reaching target borrowers, while law enforcement against illegal informal lenders remains limited8/. As a result, low-income households continue to rely heavily on informal borrowing.

The most significant limitation is that current efforts still address the symptoms rather than the root causes. Most measures focus on mitigating the impact rather than tackling underlying structural issues, such as unstable employment, insufficient income, and inadequate financial literacy among households. Without addressing these root causes, solutions to the household-debt problem are unlikely to yield sustainable results.

Structural Problem: Low Income Growth is the Major Challenge for Thai Households

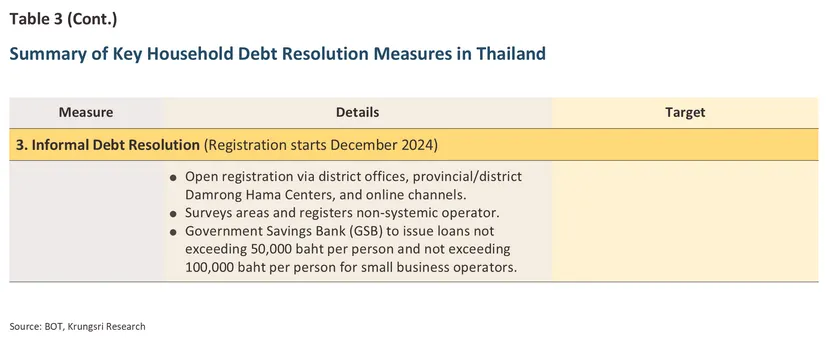

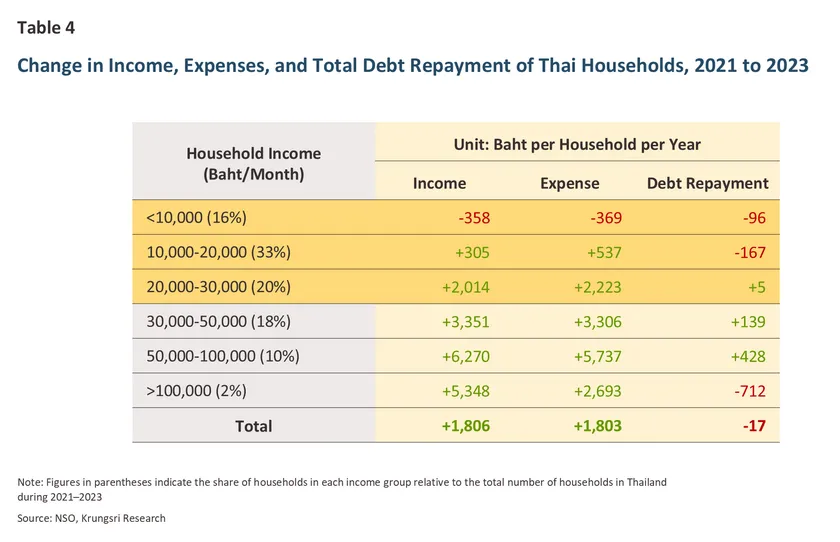

An analysis of household income and expenditure data from the latest NSO survey (2021–2023) (Table 4) reveals a significant structural problem. The average income for all households increased by only 1,806 baht per household per year, which is nearly identical to the increase in expenses of 1,803 baht per household per year. This reflects a lack of sufficient surplus income9/ for spending or saving among Thai households.

The most concerning group is households with a monthly income below 30,000 baht, which constitutes more than 69% of all households. This group is facing the problem of income growth not keeping pace with the rise in expenses. Specifically, the lowest income group (below 10,000 baht per month) experienced a decrease in both income and expenses, indicating a contraction of economic activity within this group.

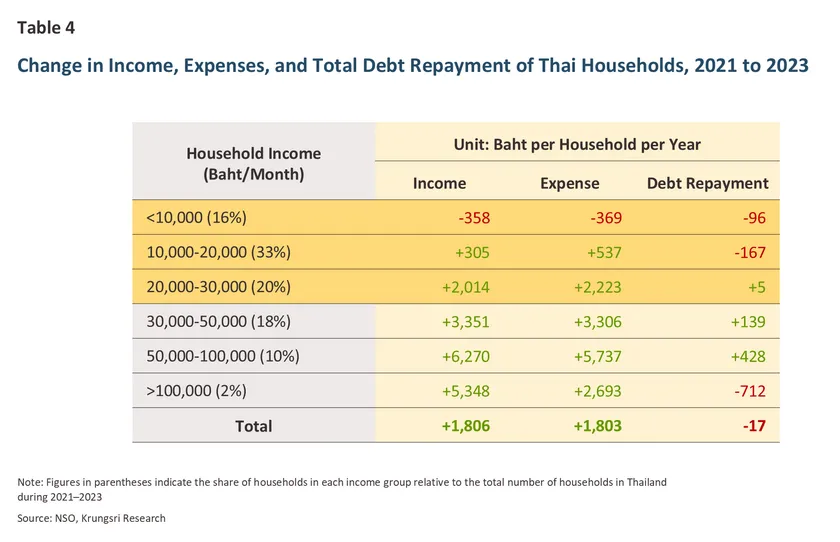

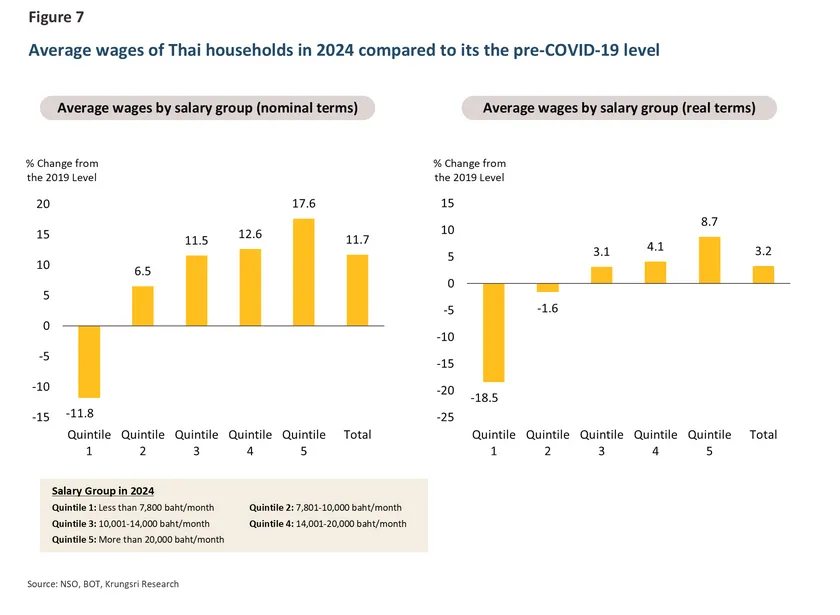

The income of Thai workers remains slow compared to pre-COVID levels, underscoring financial vulnerability, especially among the vulnerable middle-to-low-income groups.

Labor and wage survey data for 2024 further highlights the financial vulnerability of Thai households. The average nominal income of workers in 2024 increased by 11.7% from pre-COVID levels, an average rate of only 2.8% per year. After adjusting for inflation, real income increased by only 3.2% from pre-COVID levels, or an average increase of 0.8% per year. This indicates weak purchasing power due to slow recovery in worker income and financial stability.

This vulnerability is most severe among workers with income below 7,800 baht per month, whose average nominal income decreased by -11.8% (or a -2.5% decrease per year). When adjusted for inflation, their real income decreased significantly by -18.5% (a -4.0% decrease per year). This suggests that this group of workers, which is a crucial foundation of the economy, is facing increasing financial difficulties, reflected macroscopically as weak private consumption.

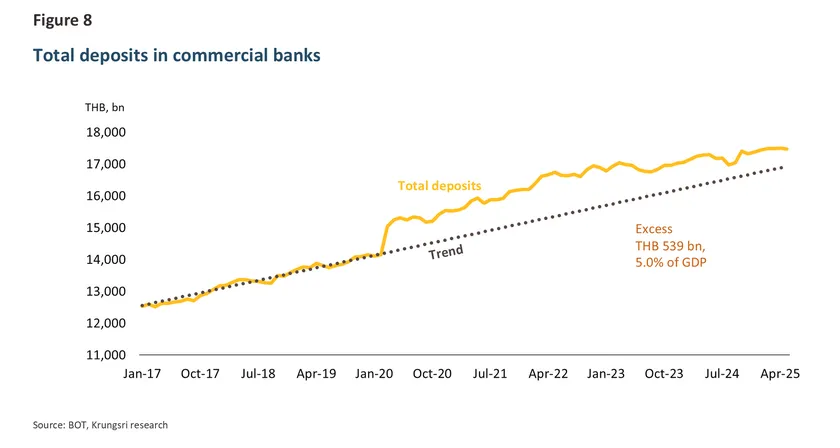

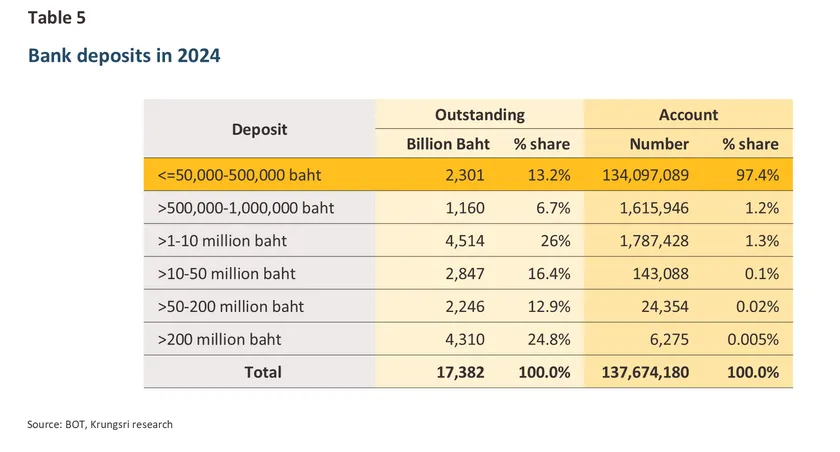

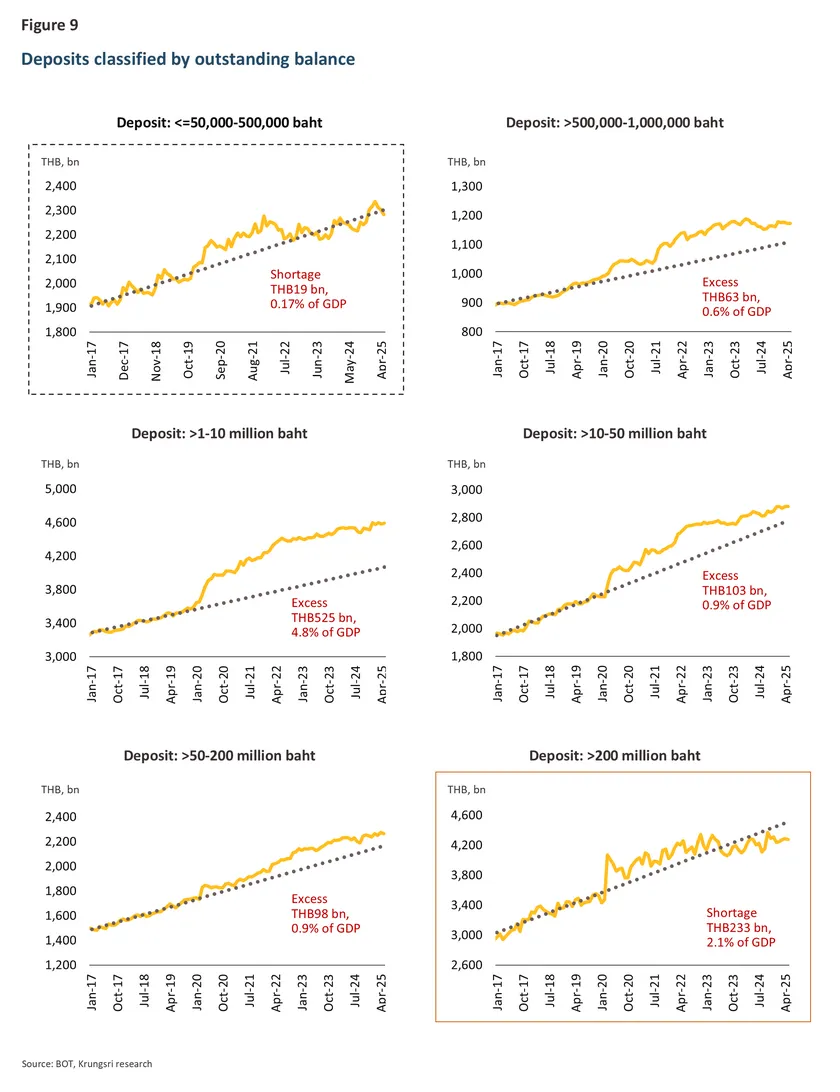

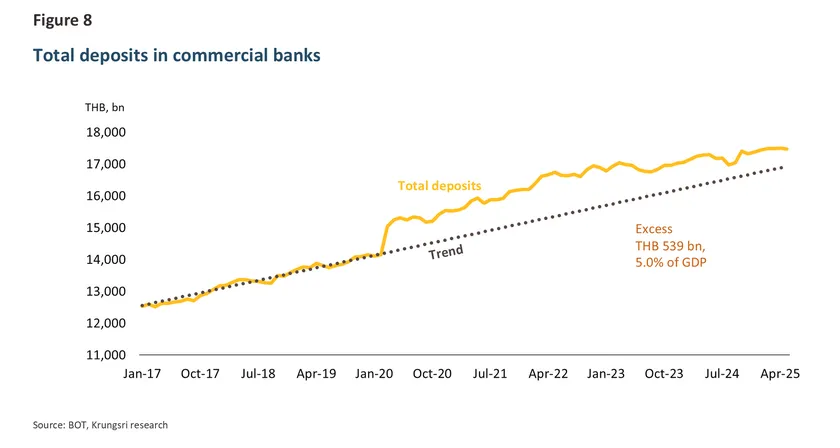

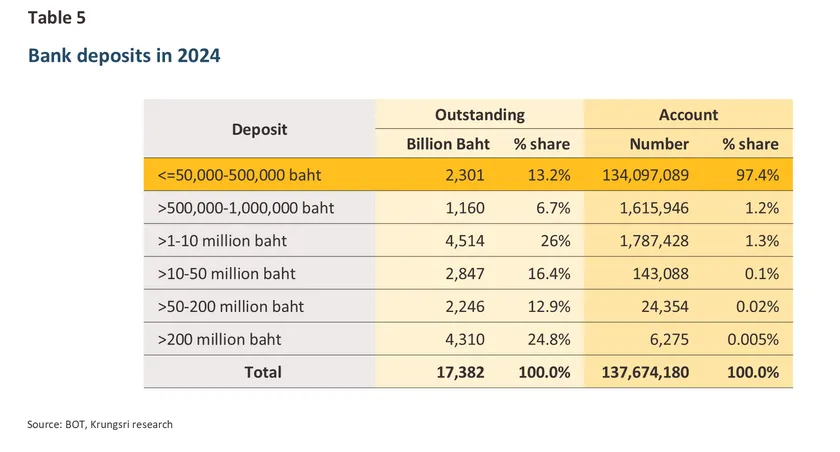

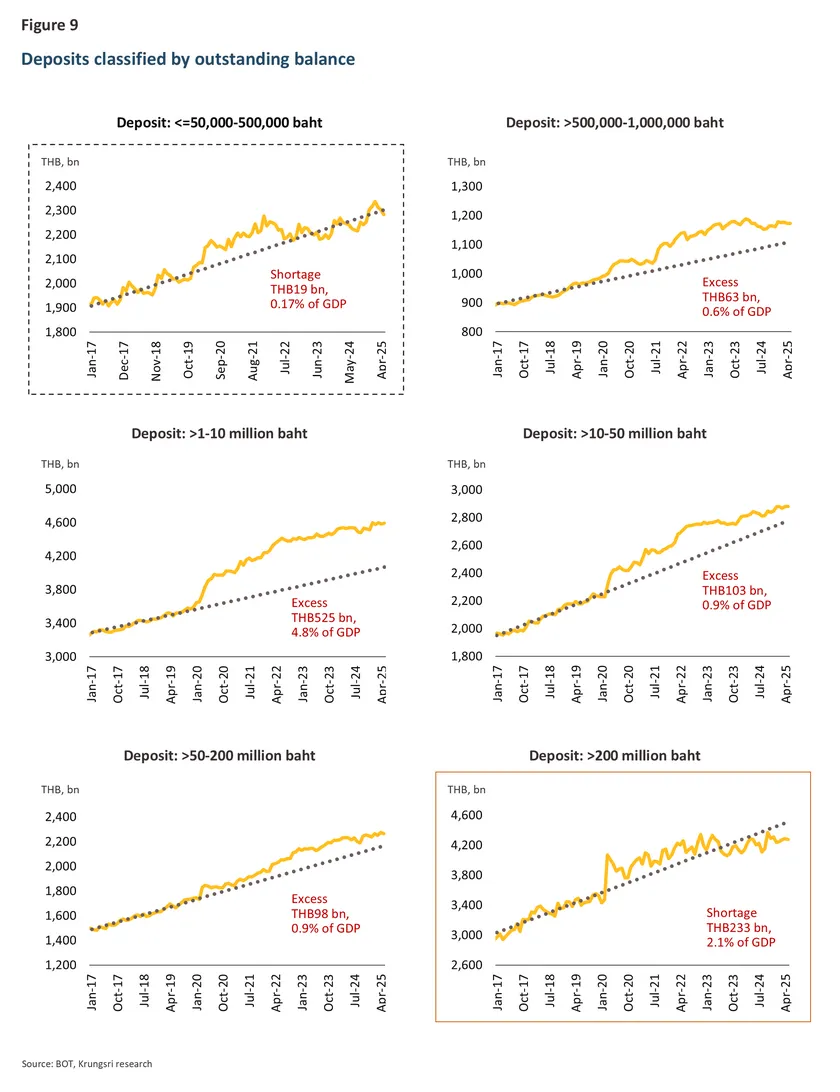

The data reinforces the escalating financial vulnerability of Thai households, partly due to a "scar" from the 2020 COVID-19 crisis that reduced workers' incomes. This aligns with the decreased value of assets held by Thai households. Furthermore, analysis of bank deposit data shows that the liquidity shortage problem is intensifying. The group of depositors with bank deposits less than 500,000 baht, which accounts for 134,097,089 accounts or 97.4% of all deposit accounts in Thailand, is continuously seeing a reduction in their surplus savings (Figure 9).

These figures indicate that the majority of the population is experiencing problems with spending and accessing credit, as well as a liquidity shortage that is likely to intensify in the future.

Krungsri Research View

Based on the above findings, we can conclude that the financial vulnerability of Thai households after the COVID-19 crisis has become a major obstacle to the recovery of domestic spending and economic activity. This is especially true for middle- and low-income households, which continue to face slow real-income recovery and low levels of liquid assets—reflecting the fragility of the grassroots economy.

Asset inequality further exacerbates this vulnerability. Low-income households tend to have limited assets and financial buffers, which restrict their access to credit and diminish their ability to withstand economic shocks. At the same time, although household debt has begun to decline in some areas, it remains above international norms, with certain borrower groups still posing notable risks.

Although the government and the Bank of Thailand have introduced various support measures—such as debt restructuring, interest-burden relief, and efforts to tackle informal debt—these initiatives still face constraints in terms of accessibility and addressing root causes, such as insufficient income and unstable employment. These issues directly hinder households' ability to accumulate assets in different forms.

For this reason, Krungsri Research believes that achieving a sustainable solution to household debt and supporting long-term economic recovery will require a serious restructuring of the household sector. Such efforts must span several dimensions: raising incomes through stable employment, developing workforce skills that align with the demands of the modern labor market, and supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as key generators of stable and quality jobs.

In addition, it is crucial to strengthen welfare systems and financial products that enhance household security—particularly accessible and appropriately-designed credit for business activities or home purchases, along with comprehensive and sustainable labor-welfare and social-security systems. These will help build adequate financial buffers for households to cope with various risks.

Furthermore, debt resolution must be both comprehensive and sustainable. This includes early intervention through effective early-warning systems, flexible debt-restructuring mechanisms tailored to each borrower’s repayment capacity, and decisive action on informal debt, supported by strict law enforcement and accessible financial alternatives.

Equally important is elevating financial literacy as a national priority. This will help cultivate sound financial discipline and prevent cyclical or more severe debt crises in the future. Financial-literacy development should begin at the basic-education level and extend to the general public through various channels to build understanding of money management, investment, and financial-risk prevention.

In summary, domestic economic activity and household spending cannot fully recover if most households remain financially vulnerable. Effective household-debt solutions must shift from short-term relief to strengthening the foundations of the household economy to ensure stability and prosperity. This approach will unlock the country’s consumption potential, support long-term sustainable growth, and meaningfully reduce inequality.

Achieving these goals requires cooperation across all sectors—government, private sector, the financial industry, and civil society—to build an enabling environment for balanced economic and social development. This will allow Thai households to achieve stable and sustainable living in the years ahead.

References

Bank of Thailand. (2024). “How critical is Thai household debt, and why shouldn't it be overlooked?”. Retrieved from https://projects.pier.or.th/household-debt

Chula Digital Collections. (2022). “The Determinants of Thai Household Debt: A Macro-level Study”. Retrieved from https://digital.car.chula.ac.th/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1337&context=jdm

Bank of Thailand. (2025). “Media Briefing You Fight, We Help, Phase 2”. Retrieved from : https://www.bot.or.th/th/news-and-media/news/news-20250701.html

Bank of Thailand. (2025). “Banking Sector Quarterly Brief (Q2 2025)”. Retrieved from : https://www.bot.or.th/en/news-and-media/news/news-20250819-2.html

Krungsri Research. (2024). “Thai household debt and the risks to the economy”. Retrieved from : https://www.krungsri.com/getmedia/022e5984-6554-4ec6-bf31-8f6ea7cc3c77/RI_Household_Debt_240516_TH.pdf.aspx

1/ Liquid assets include bank deposits, financial assets for investment, as well as other assets such as gold, jewelry, and accounts receivable

2/ The SET Index fell more than 2.3% during 2021–2023. Measured from the beginning of 2022 (1,664.5 points), it posted a cumulative loss of over 14.9%, weighed down by Thailand’s sluggish economic recovery, elevated global and domestic interest rates, and rising geopolitical tensions, including the Russia–Ukraine and Israel–Hamas conflicts.

3/ A cyclical debt crisis refers to a situation in which individuals become trapped in a continuous loop of accumulating debt. The main causes often include overspending, poor financial planning, and income that falls short of covering expenses and existing debt obligations. As a result, individuals take on additional debt to sustain daily living expenses or to repay previous debts.

4/ Commercial-bank credit (including subsidiaries) continued to contract in Q2 2025, marking the fourth consecutive quarter of negative growth at -0.9% YoY — the longest period of contraction in more than 20 years. This decline was driven by ongoing contractions in SME lending and consumer loans, reflecting persistently high credit risk.

5/ Non-Performing Loan (NPLs) refers to bad debt or loans overdue for more than 3 months or 90 consecutive days.

6/ Special Mention Loan (SMs) refers to loans overdue between 1-3 months.

7/ Moral Hazard refers to a situation where stakeholders decide to take on more risk because they believe they will not have to bear the resulting losses or negative consequences, often occurring in cases of insurance, financial assistance, or government subsidies. held with financial institutions and financial service providers regulated by the Bank of Thailand (such as commercial banks and non-bank lenders). However, many borrowers—especially those with unstable income—rely on informal lenders, who are not directly included in the scope of assistance. Moreover, although laws specify penalties for illegal lenders, enforcement remains limited due to difficulties in tracing illegal operations and constraints in legal procedures. As a result, informal lenders continue to operate, while many borrowers are reluctant to report them due to fear of intimidation or losing access to future loans.

8/ Government debt-relief measures continue to focus mainly on formal-sector borrowers, rather than those in the informal loan market. The measures cover only debts

9/ Surplus income refers to the change in net total income after deducting total expenses for household groups during 2021-2023, used to assess the spending and saving capacity of each household group.

10/ All Commercial Banks' Deposits Classified by Sizes and Maturity (2025) | Bank of Thailand