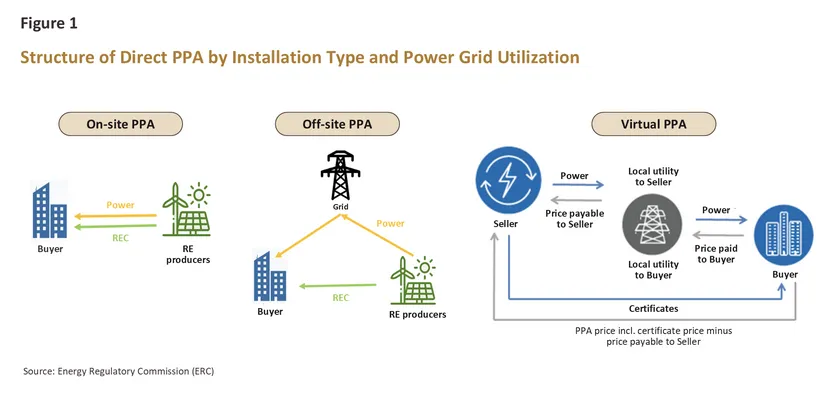

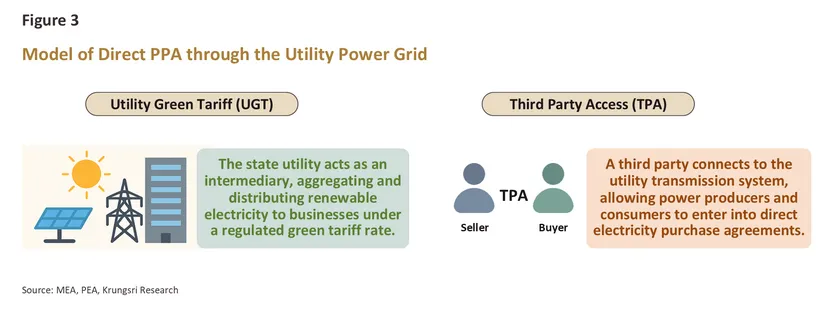

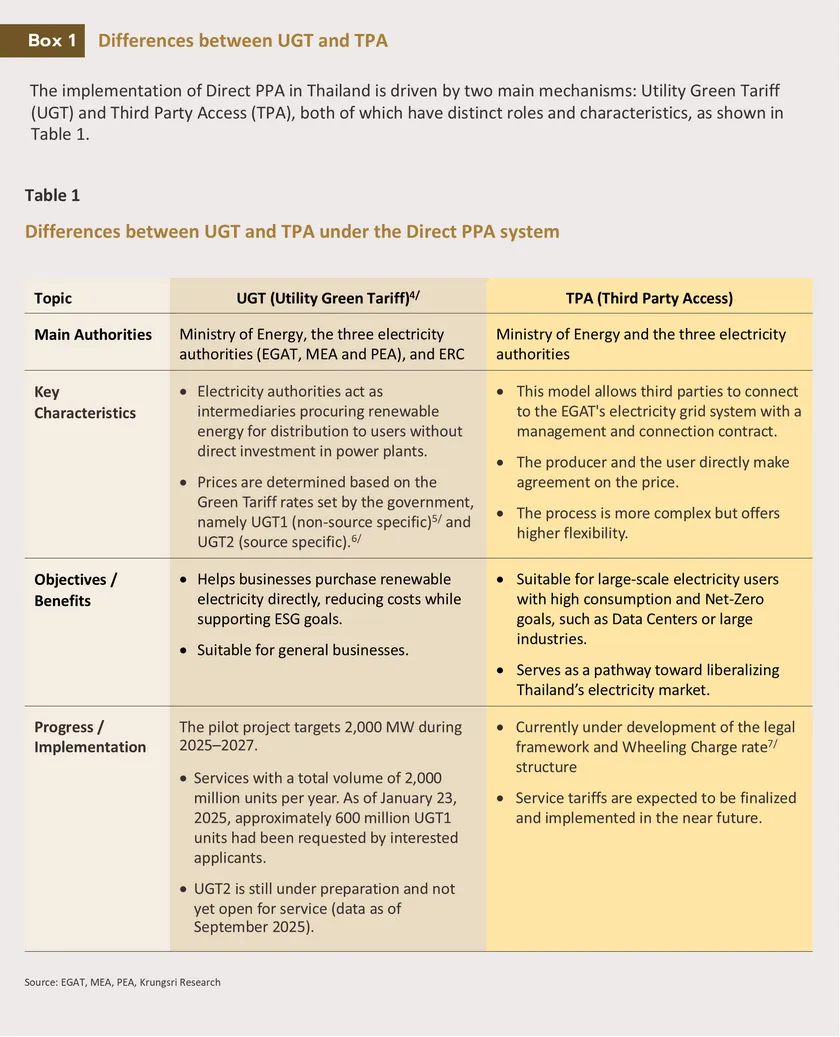

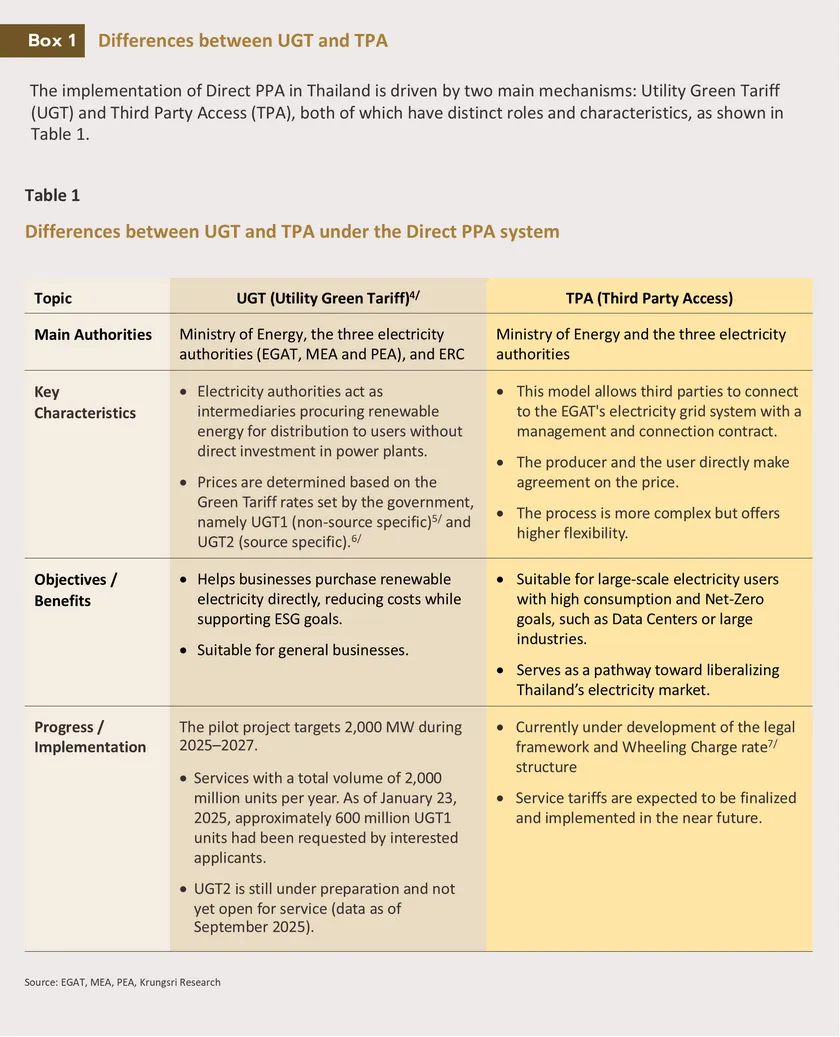

These can also be subdivided into two smaller categories.

Direct PPAs organized as UGTs are thus most suitable for companies that wish to simplify operations while maintaining a high level of electricity supply reliability, whereas TPAs will help increase choice and provide greater freedom for companies that are sourcing power generated from renewables, and over longer timeframes, this will drive further liberalization of Thailand’s electricity market. Being able to choose a model that fits an individual company’s procurement and usage needs will, together with stability and clarity in government policy, be important factors in allowing the private sector to plan effectively for investment in energy management and corporate infrastructure.

This will be particularly so when TPAs are implemented and fully operational since these will help to improve flexibility, transparency and competition within the market. These will also have the advantage of serving as an important vehicle through which innovations and new energy technologies can be disseminated (e.g., peer-to-peer energy trading),3/ and over the long term, this will then help improve the efficiency of the country’s energy system and put it on a much more sustainable footing.

Current Landscape & Key Market Drivers

Benefits of using direct PPAs

Direct PPAs offer a wide range of benefits for businesses, power producers, commercial end users, and the country at large. For companies, direct PPAs serve as a key mechanism to reduce costs and manage risk arising from volatility in energy prices, address ESG requirements, and comply with international trade and environmental standards, thereby contributing to national competitiveness. For power generation companies, direct PPAs will guarantee more stable markets, providing incentives to invest in renewables (e.g., rooftop solar, and wind and solar farms) and related technologies, such as energy storage systems and smart grid applications.

Meanwhile, at the national level, the use of direct PPAs will improve overall energy security, reduce dependency on fossil fuels, attract additional FDI inflows, and contribute to the development of new supply chains related to rooftop solar installations and AI-powered energy platforms. In addition, clear policy support from the government will help accelerate the energy sector’s transition to clean energy.

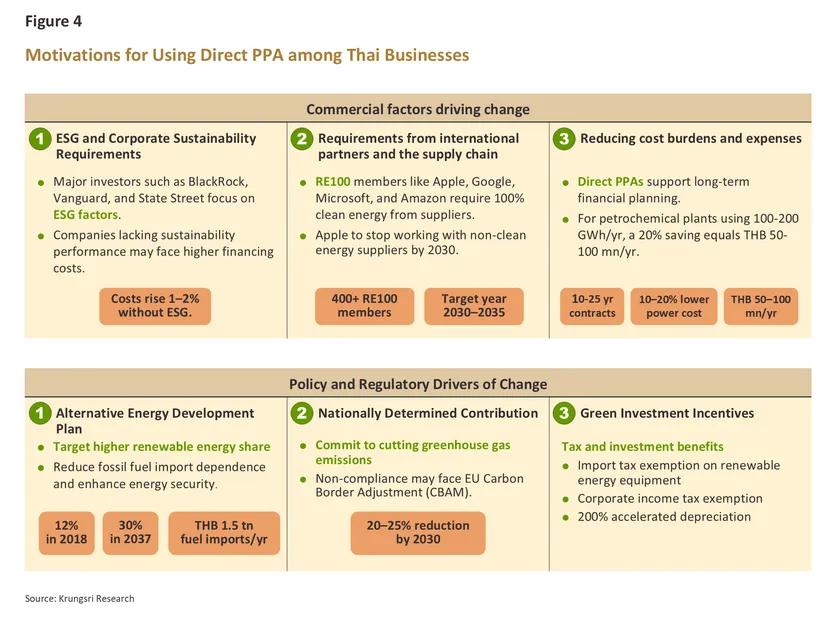

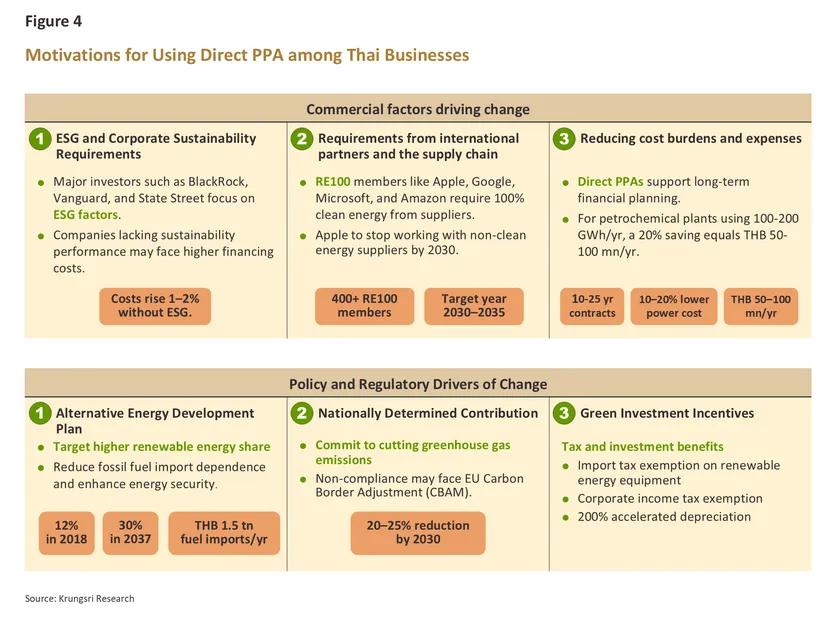

Commercial factors driving change

-

ESG and corporate sustainability requirements: These are becoming an ever-more significant factor in the contemporary business environment, as reflected in the significant shift by institutional investors at leading global powerhouses and the greater weight that these are now putting on ESG issues. For example, BlackRock has called on companies that they invest in to engage in public ESG reporting, while Vanguard has pledged its support for players that invest in ESG implementation. There is thus a risk that organizations that neglect or overlook ESG-related issues will lose competitive advantage to rivals that address these issues, and one consequence of this could be that they then face higher business costs.

-

Requirements imposed by international trade partners or supply chain commitments: The RE100 initiative has now been joined by over 400 major global corporations, including Apple, Google, Microsoft and Amazon, but in addition to pledging to the use of 100% renewable energy themselves, membership also requires that a corporation’s suppliers do likewise. Apple has therefore requested that over 200 of its suppliers switch to the use of clean energy and that they commit to transitioning to net zero emissions.8/ Thai businesses thus need to step up their own commitments to the use of renewables if they are to maintain their current positions within transnational supply chains.

-

Cost pressures: Companies are particularly motivated to reduce their exposure to price volatility in energy markets, and direct PPAs are able to facilitate this since these typically involve 10-25-year supply contracts. This allows companies to manage long-term costs more effectively, though in addition, these contracts may offer the additional attraction of undercutting grid-supplied power.9/ This is especially the case for major consumers of electricity, such as large petrochemical plants, which can draw 100-200 gigawatt hours of power annually. For players such as these, savings can easily run into double-digit percentages,10/ which translates into cost reductions of tens or even hundreds of millions of baht per year, though the exact extent of the savings will depend on the tariff structure, the size of the project, and the details of the individual PPA.

Policy and Regulatory Drivers of Change

-

The 2018-2037 Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) promotes electricity generation from renewable energy and to this end, it has set a goal of raising the contribution of renewables from 12% of supply as of 2018 to 30% by 2037. This will help to cut the bill for imports of fossil fuels from its current level of more than THB 1.5 trillion annually.

-

Thailand’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), as outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement, call for 20-25% reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and this will necessarily imply that the private sector will move to a greater reliance on renewable energy sources. Moreover, failure to meet these goals may result in Thailand being downgraded to less favorable trading arrangements, for example as would be the case under the EU’s CBAM.

-

Government investment promotion schemes: These include the waiving of duties on imports of equipment used by renewables generators, tax exemption for companies investing in energy production, and accelerated depreciation rates on renewables generating equipment (up to 200%). These measures have had a significant impact on costs, thereby helping to increase the appeal of investments in clean energy and encouraging an uptick in investment inflows.

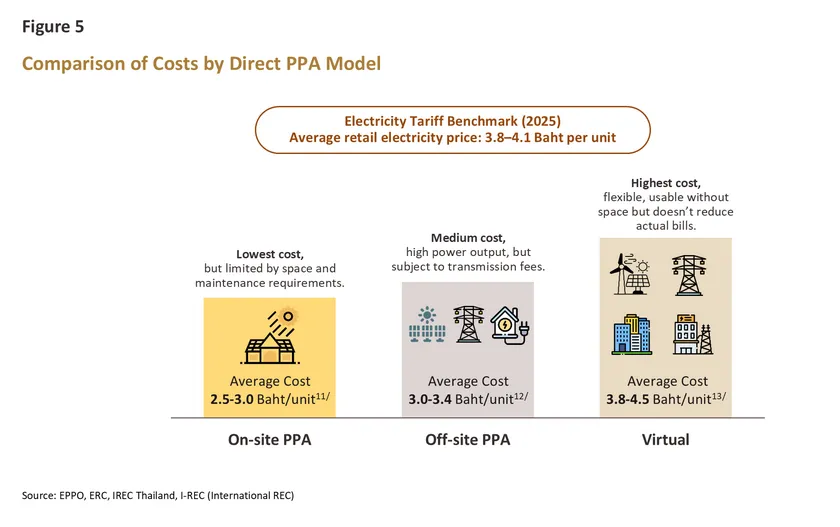

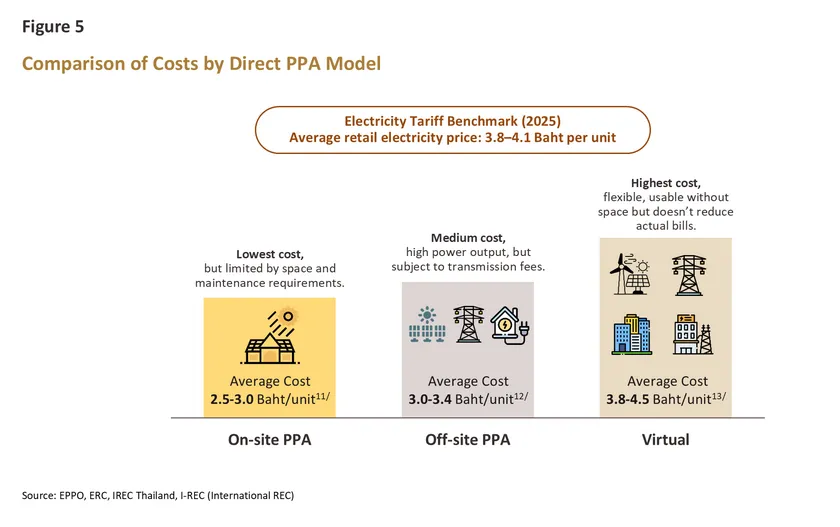

In terms of electricity costs

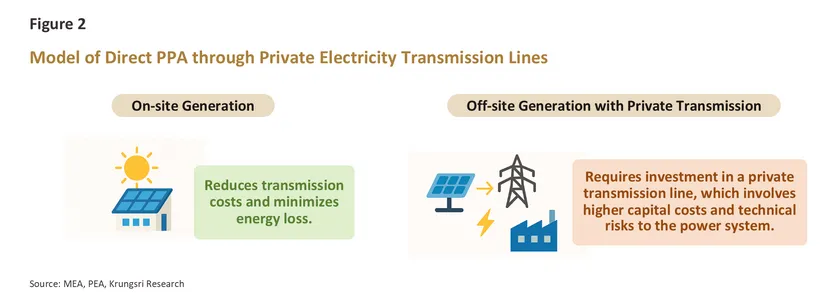

Direct PPAs can generate significant long-term cost savings relative to grid-supplied electricity, especially for companies that consume significant amounts of electricity. This is because suppliers of renewable-powered electricity are able to offer competitive prices without needing to match the price structure of the state supplier, which includes the energy charge, the automatic Ft adjustment, and the addition of wheeling charges. On-site PPAs are the lowest cost option, as they eliminate any costs related to the transmission of electricity, though this comes at the expense of restricted production times (solar energy can only be generated when the sun is shining), site-related limitations, and additional maintenance overheads. Off-site PPAs sit in the middle of the cost curve since while use of a distribution network imposes greater costs, producers have more flexibility over where they site their facilities and this generally then allows them to generate more electricity. Virtual PPAs are the most expensive option, and cost savings may only be negligible since under these arrangements, power is bought from the grid, while companies also have to pay THB 0.2-0.5/unit for their RECs. Nevertheless, for companies looking for a straightforward way to meet ESG requirements that they demonstrate their use of renewables, these remain a viable option.

Opportunities and Threats of Direct PPAs for Thai Businesses

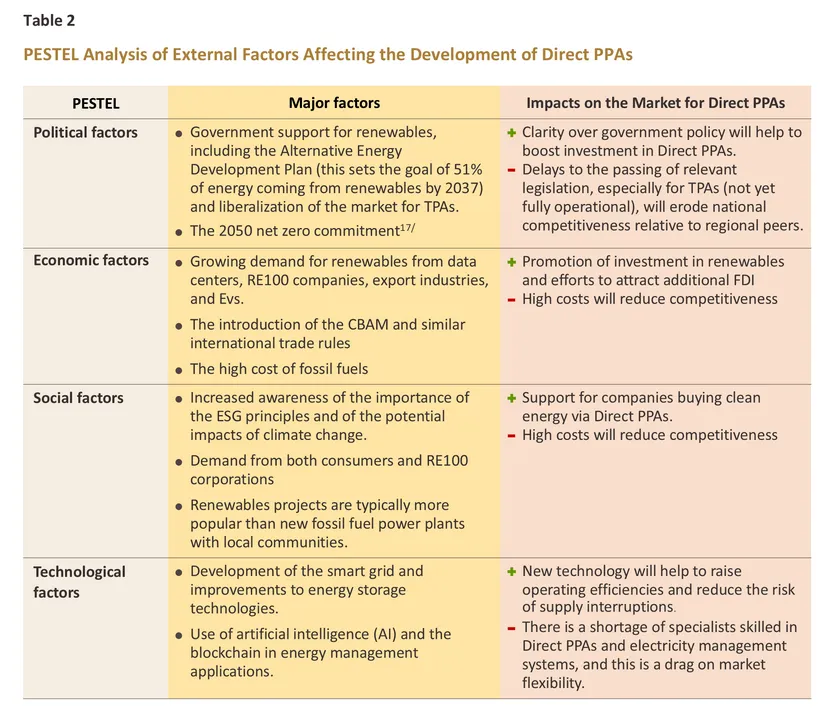

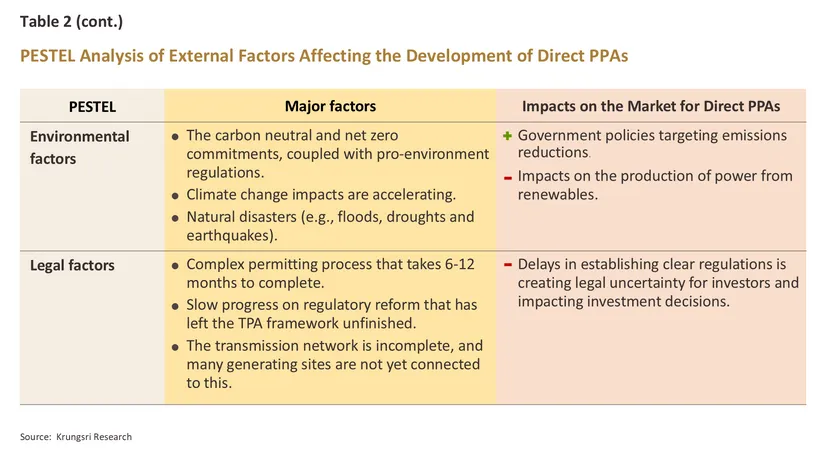

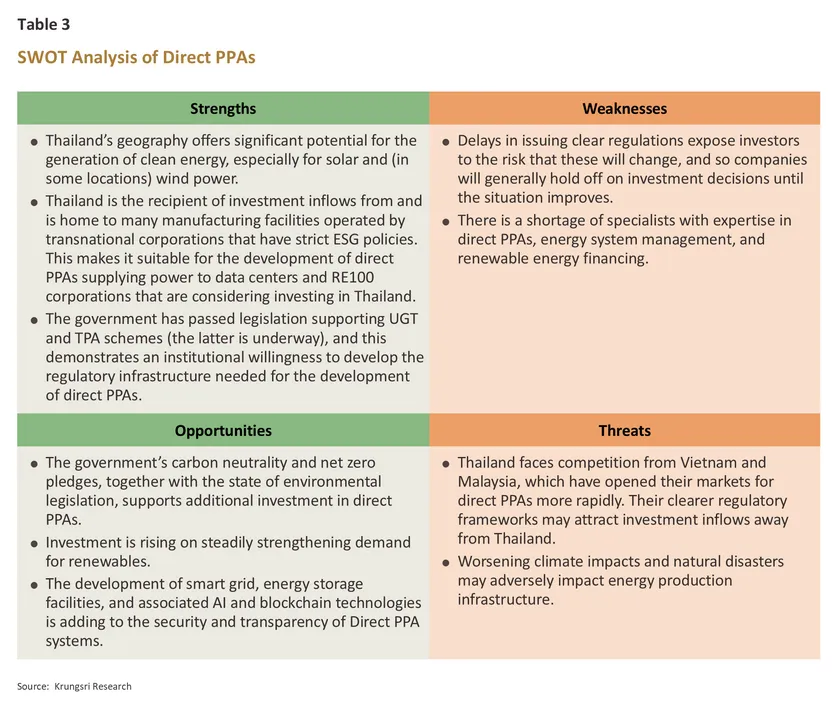

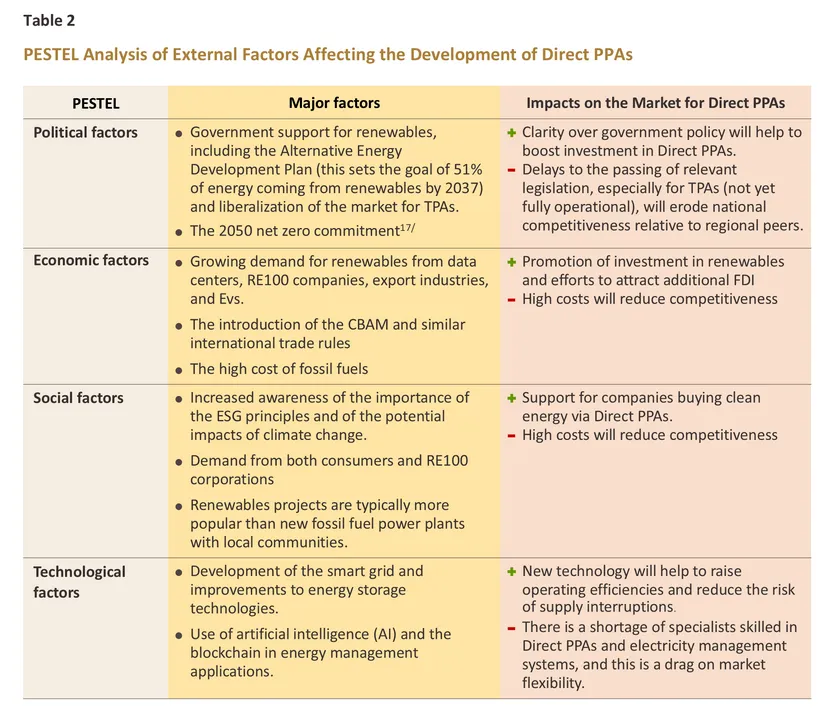

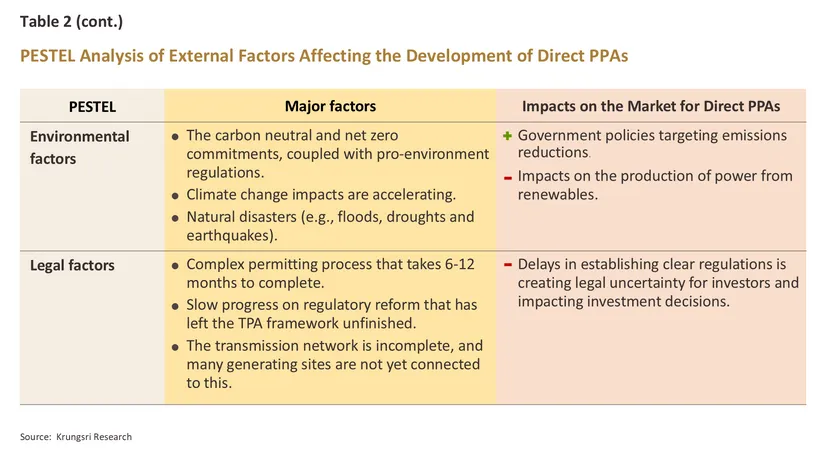

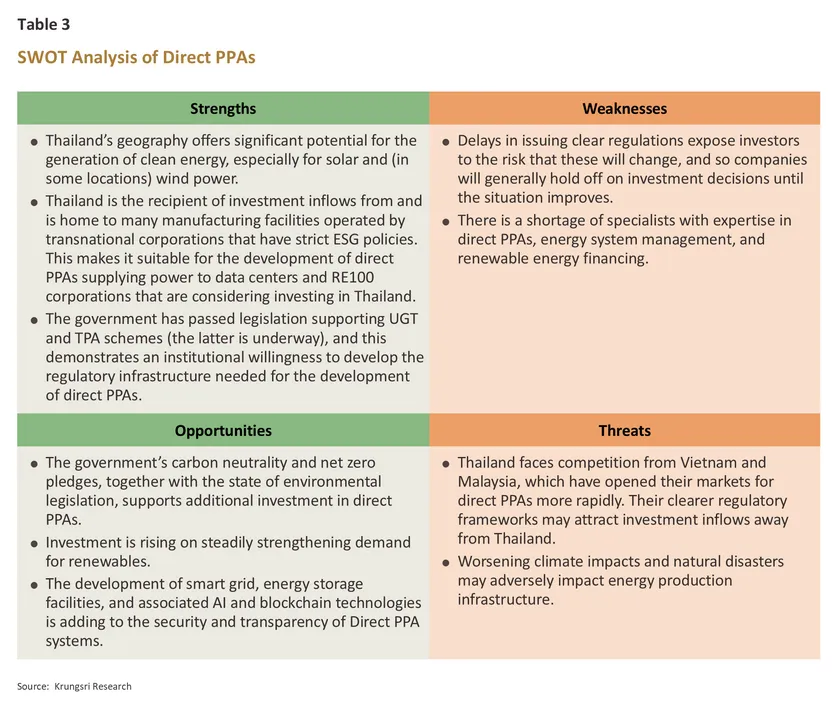

Carrying out an analysis of the opportunities and threats connected to the development of Direct PPAs will depend on an understanding of external factors and the extent of domestic readiness for these changes (i.e., internal factors) as these relate to society, the economy, the state of technological preparedness, the regulatory framework, and the business environment. In this paper, a PESTEL (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal) framework is adopted to analyze the external factors affecting the market for Direct PPAs. Separately, a SWOT analysis is used to assess the internal factors, which are therefore investigated in terms of their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Use of these two analytical tools will help policymakers and stakeholders better understand the state of the overall business landscape and key drivers of the market. This will further allow companies to address their weaknesses and threats and to exploit their strengths and opportunities, thereby boosting the effectiveness and efficiency of long-term strategic planning (see Table 2 and Table 3 for details).

Tables 2 and 3 show that thanks to the positive impacts of government policy, demand from Thai businesses, pressure from overseas trade partners, and the inflow of investment funds into the development of new technologies, the domestic market for direct PPAs has substantial growth potential. Moreover, these provide clear support for companies working towards meeting the ESG goals, while Thailand has also been blessed with many sites suitable for use in the generation of clean energy. Nevertheless, challenges remain, specifically in the areas of legislation, infrastructure, human capital, regional competition, and the ever-present possibility of a shift in government policy.

To address these issues, Thailand needs to convert market headwinds into tailwinds. This is especially so with regard to regulations, which need to be streamlined and clarified, and in particular, the development of the TPA framework must be completed. The government also needs to develop a more comprehensive set of incentives to attract investment into the development of technologies connected to smart grids and energy storage, as well as into work on digital platforms. The industry’s skill shortage remains another area of concern and measures to deal with this will need to focus on the development of greater expertise in the areas of direct PPAs and related technologies. Nevertheless, success in these endeavors would help to increase the market’s long-term flexibility and would go a long way towards establishing direct PPAs as a key mechanism for helping companies engage in strategic planning and to more effectively manage their energy supplies. More broadly, this would also sharpen the ability of Thai corporations to compete effectively on the world stage.

Strategic recommendations

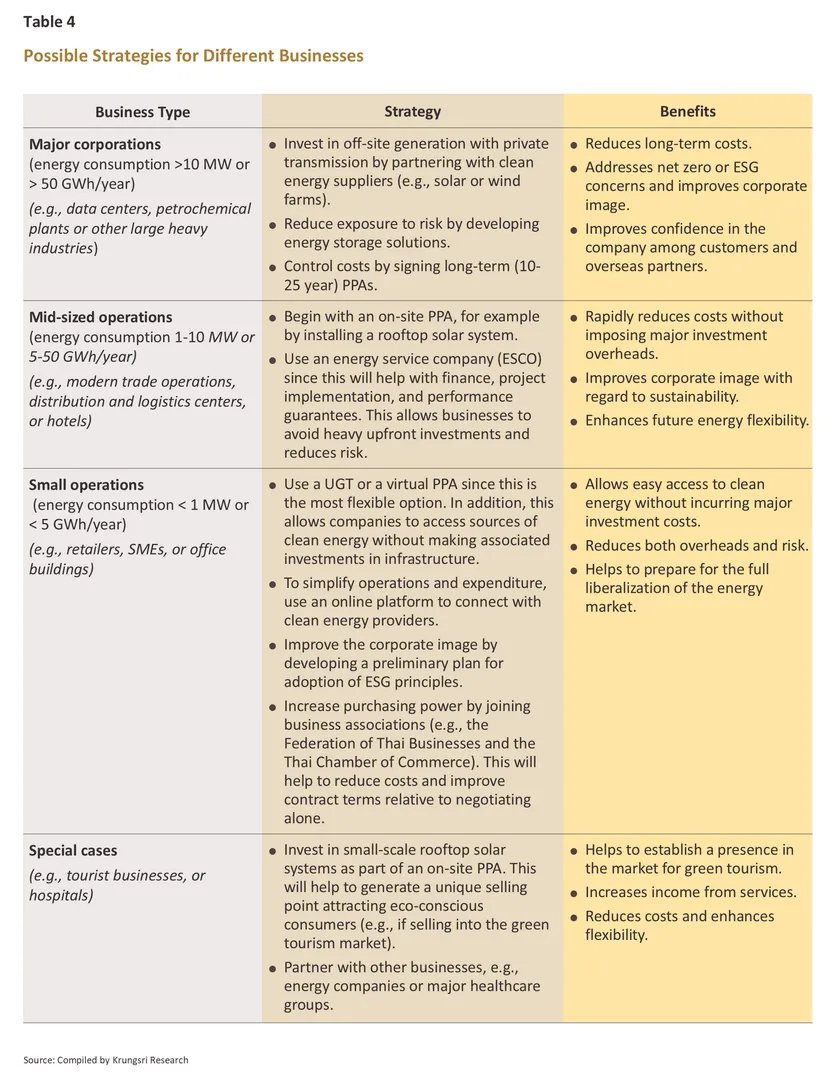

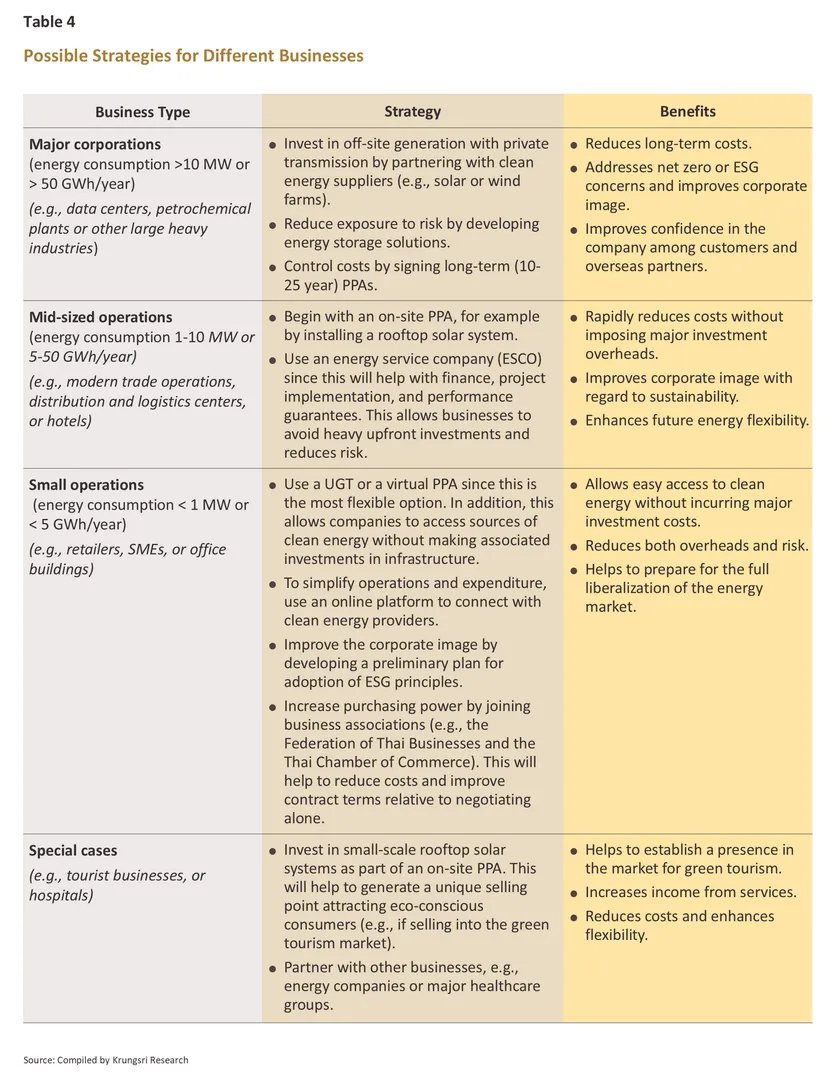

Having carried out a macro assessment of the factors influencing opportunities and threats to the development of direct PPAs, the next issue to be addressed is a consideration of how businesses should best move forward. Players in different sectors of the economy will need to choose the PPA model that is the best fit for their electricity consumption and general needs, though the selection process will begin with a decision over whether an on-site, off-site or virtual PPA is best since making the right choice here will be a key determinant of overall success later (Table 4).

Indeed, choosing the appropriate model will not only help to reduce costs and improve competitiveness, but this will also aid the company in better managing risks to its energy supply, all the while boosting the confidence of both investors and overseas trade partners in their operations. Beyond this, greater cooperation between the public and private sectors, including financial institutions, will help to underpin sustained growth in the market for Direct PPAs.

The Domestic Development of Direct PPAs

With businesses under pressure from changes to trade and environmental legislation and approaches to investment overseas, the development of the domestic market for direct PPAs is approaching a turning point as this moves from being simply one option among many to a core determinant of a business’s competitiveness. Three primary factors can be identified that are shaping this transition: government policy, the most important of these, is moving direct PPAs from being a choice to a necessity; demand from business is rapidly expanding the overall size of the market; and technological advances are raising efficiencies, lowering costs and enabling further business innovation. Given this context, the following section will discuss significant trends in investment and market growth, as well as areas of technological progress that will further attract inflows of global capital and so accelerate investment in direct PPAs.

-

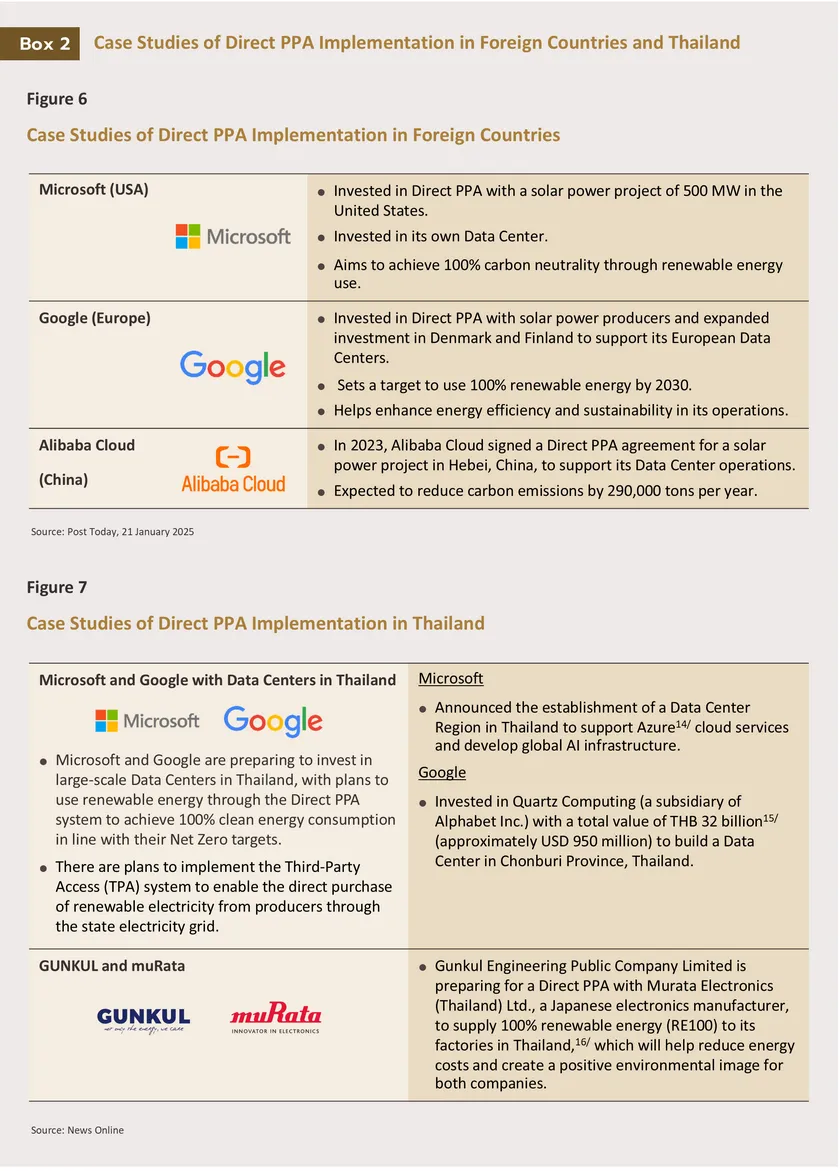

Investment inflows are increasing, and the market is continuing to expand on widespread growth in demand for clean energy across much of the economy. This is then stimulating greater investment in renewables both within Thailand and overseas, and downstream from this, direct PPA projects are attracting ever-growing interest

-

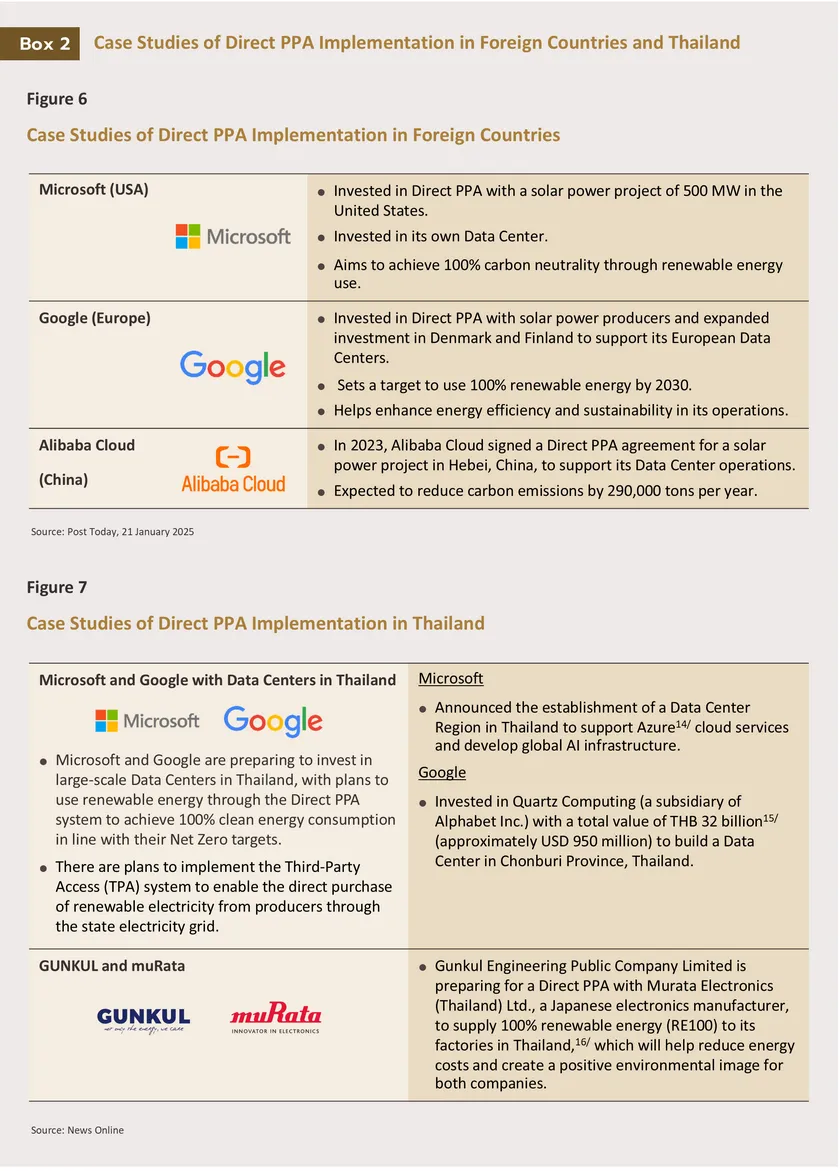

Investment by overseas corporations in Thailand, especially by RE100 members, is rising thanks to the pressures exerted by ESG assurances, net zero pledges, and the introduction of regulations such as the EU’s CBAM. In particular, members of the RE100 group will aim to align their operations with their ESG and net zero commitments by securing access to 100% renewables-based power, and as part of this, global leaders in the operation of data centers such as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon Web Services are planning to build these in Thailand and to power these on locally supplied clean energy. Indeed, after Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia, Thailand is emerging as one of the most attractive investment targets in the ASEAN zone, and more than THB 100 billion in additional foreign direct investment (FDI) is now expected. This will necessarily boost demand for clean energy and should prompt the government to accelerate development of UGT2 and to implement third-party access (TPA) regulations.

-

Thai energy companies are expanding the services that they offer and strengthening their international partnerships. Leading players including EGCO, BCPG, GPSC, and B.Grimm Power together with companies in target industries that will in the future be heavy consumers of clean energy (including advanced automotive, digital, comprehensive healthcare and the bio, green and circular industries) are starting to increase the range of services that they are involved in, from renewables generation through to energy management. This includes the development of large-scale solar and wind farms, the buildout of which will then help to add to total domestic installed renewables capacity. In addition, these players are partnering with companies in Japan, Germany, and Australia to develop smart grid applications and to accelerate the transfer of advanced technologies. This will then help to develop new value chains connected to energy storage, AI-based energy management systems, and rooftop solar installations.

-

Intensifying competition in Southeast Asia is pushing Thailand to speed up the development of the domestic market for direct PPAs. Elsewhere in the region, Vietnam has moved ahead of Thailand by rolling out a clear regulatory framework and developing the infrastructure necessary to fully support its own Direct PPA market. Indonesia has also introduced measures that will underpin increased use of renewables, partly by opening sites suitable for large-scale wind and solar farms. Given this, if Thailand continues to delay, it may fall further behind other economies in the region, and if this happens, the country will lose opportunities to attract foreign investment and risks being excluded from global supply chains.

- Further advances in technology will be an important factor improving the stability, transparency and efficiency of direct PPAs.

Technology is clearly a major driver of growth across almost all parts of the economy, and within the energy sector, digital technologies and energy storage systems have a particularly important role to play in how the industry will evolve. Three areas will be especially important for the future of direct PPAs. (i) AI and smart grid technologies can be used to provide real-time data analysis, thereby helping electricity producers and consumers better manage the load placed on the system. Current examples of this include the development of smart transformers by the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA), which has now enhanced its ability to manage electricity usage, and through this, demonstrated how AI can be applied to the development of smart grids. (ii) Energy Storage Systems (ESSs) can help to address problems with intermittent supply from renewables (Investment is beginning to flow into ESSs linked to large solar farms in the Eastern Economic Corridor). (iii) Blockchain and Peer-to-Peer trading will improve the transparency and verifiability of electricity trading, though companies will have to wait for the full liberalization of the market for TPAs before this becomes a reality (Table 5).

Direct PPAs present a real opportunity for Thai businesses to transition toward a sustainable energy system

The market development for direct PPAs marks a potentially major turning point for Thai businesses, and this is providing an opportunity for the country to both transition to the green economy and to hone its ability to compete effectively in global markets. Moreover, in addition to lower energy costs for businesses, moving forward with these changes will also allow companies to meet their ESG commitments while simultaneously generating tangible and positive outcomes from investments in renewables. However, in the initial stages of this transition, a wide range of challenges will need to be overcome, including the current inadequate state of energy infrastructure, regulatory confusion, high initial overheads, and a shortage of skilled labor, though these problems can be addressed through cooperation between stakeholders. In particular, it is imperative that public authorities navigate the existing legislative complexities to establish a clear and consistent regulatory environment, as success in this area will be a key determinant of positive investor sentiment and the long-term growth of the direct PPA market. Beyond this, ensuring that the energy transition is strong and sustainable will require that the business sector undertakes a strategic shift and strengthens its capacities in the following three areas.

-

The development of specialized service providers: To better respond to rapidly growing demand, this will include energy service companies (ESCOs) that have expertise in the design, analysis and management of renewable power systems, and financial service companies that understand both direct PPAs and the clean energy industry, and that are therefore able to help clients better manage risk and access sources of capital.

-

Investment in research and development: This will help Thailand transition from being technology consumer to being a technology developer and a source of high-value exports. This would have the additional benefit of deepening linkages to energy supply chains.

-

The creation of energy-management digital platforms: These will connect generators, end users, service providers and regulators, thereby increasing the transparency and efficiency of the market.

Making greater progress on these three fronts will help to develop the market, and through this add to its flexibility, reduce the costs businesses pay for their energy supplies, sharpen national competitiveness, and help public- and private-sector bodies meet their ESG and net zero pledges.

Importantly, there is also a major role for government to play in these processes, and if the public sector adopts a proactive stance towards policy, infrastructure development, finance and skills development, this will have a significant impact on the development of a supporting ecosystem that boosts investment and fosters stronger business confidence. Action will thus be necessary across five interacting and mutually supportive areas.

1) Accelerating the development of third-party access (TPA) protocols: Because this enables companies that generate electricity from renewables to distribute this directly to business customers via the national grid, TPA-driven liberalization of the electricity market is a cornerstone of the overall development of direct PPAs. Progress on this will deliver benefits across three core areas.

-

Economic benefits: Using the national grid to transmit electricity is cheaper than using UGT systems so this will lower business costs and pull in greater investment inflows, especially from data center operators and RE100 members. By contrast, failure to move forward with TPA liberalization will put more than THB 1.1 trillion in FDI at risk and will threaten over THB 700 billion worth of investments in the new target industries of EV manufacturers, and digital and green technologies.22/.

-

Social benefits: These moves will create high-quality employment opportunities and lift the overall level of skills within the workforce, helping to shift this towards a greater focus on green jobs, although to date, this transition has been slow; over 2013-2022, employment within green industries grew by just 1% (TDRI, July 25, 2025).

-

Environmental benefits: Naturally, these changes will increase the share of renewables within the national energy mix, thereby accelerating the move to carbon neutrality and net zero.

2) Overhauling the relevant legislation and streamlining oversight: Clarifying and simplifying the regulatory environment would go a long way towards building investor confidence and accelerating growth in the market. Moves in this area should include expediting the development of technical and safety standards to ensure alignment with international norms and reducing the timeline for the permitting process from its current 6-12 months to something closer to 3-6 months. The latter could be facilitated by greater use of online systems and the establishment of ‘one stop service centers’. In addition, legislation needs to encompass new technologies, such as blockchain-based energy trading, AI-powered energy management systems, and the integration of direct PPAs and energy storage systems, thereby modernizing the energy system and making it more flexible.

3) Providing financial assistance: Providing financial support to companies will cut their costs and reduce their exposure to risk, thereby speeding up investments in direct PPAs and accelerating growth in the market. Examples of this could include: waiving duties on imports of plant and machinery used in energy storage or the generation of clean energy (currently set at 5-10%), which would help to cut upfront costs; giving tax credits to investors in direct PPAs, allowing these to reclaim tax to 100-200% of the value of their investments over a period of 5-10 years; establishing a fund to provide low-interest financing to Direct PPA projects, especially for SMEs that otherwise have difficulty accessing sources of capital; and implementing government-backed credit guarantee schemes that ease private-sector access to lower-cost financing while reducing financial risk and strengthening investor confidence.

4) Developing the necessary energy infrastructure: If the infrastructure that underpins the market is inadequate, direct PPAs will struggle to make progress, though transmission and energy storage systems are areas of particular concern since these are core facilitators of energy market liberalization. The government should therefore step up spending on the development of smart grid infrastructure and ensure that this is capable of aggregating supply that may be widely distributed across rooftop solar installations, wind farms and biomass generating plants. Equally important will be the construction of large-scale energy storage facilities since these will be needed to offset fluctuations in the quantity of renewables power entering the grid and so ensure stability of supply. The transmission network will also need to be upgraded to handle bi-directional electricity flows, while the establishment of real-time data centers will improve market transparency and attract greater investment inflows.

5) Developing new areas of expertise and upskilling the workforce: A key factor determining growth in the market for direct PPAs is corporate access to staff with the necessary technical, legal and operational skills and knowledge. The government should therefore respond to this potential bottleneck by working with universities to develop clean energy curricula and courses, providing specialist training and certification, and promoting knowledge transfer from countries that have already substantially increased the share of renewables in their national energy mix, developed and implemented smart grids, and liberalized their energy markets. Examples of the latter include Germany, where the ‘Energiewende’ policy has resulted in the rollout of a smart grid system that integrates energy supplied from external renewables-based generators,23/ and Australia, where a blockchain-based peer-to-peer energy trading system is being trialed24/ and the electricity market is being liberalized.

These five measures will provide key support for the development of direct PPAs and as such, all five need to be implemented concurrently. However, achieving success in this area will help to build a market that is secure, flexible and competitive, and then to carry the country closer towards its carbon neutrality and net zero goals. Additional benefits will also be seen in the consequent improvements to energy security, competitiveness and sustainability.

Over the long term, the full implementation of TPAs will mark a major milestone on the path toward liberalizing the domestic electricity market and introducing genuine competition. This will also help to facilitate the more rapid adoption of new technologies, such as peer-to-peer energy trading, and the development of new business models, and in turn, this will attract major investments into the industry, especially from data center operators and companies looking to fulfil their net zero and ESG pledges. Ongoing government action in this space could also act as a catalyst transforming pressure on the energy sector into opportunities for green growth, job creation, and improvements to national competitiveness. However, the flip side of this is that if the authorities delay further or are only inconsistently attentive to the energy sector, there is a risk that Thailand will miss out on investment opportunities and will see its global competitiveness suffer as its nimbler and more swift-footed regional peers step into the market space that it has vacated. As such, it is imperative that private-sector players, financial institutions, and the authorities coordinate their activities if Thailand is to develop the resilient, stable and sustainable energy system that will be needed to confront the challenges posed by the 21st century and the transition to a world where sustainability is no longer a choice but a necessary precondition for long-term business survival and growth.

References

Bangkok Post. (2025). “Thailand gears up for green energy transition and Direct PPA market.”

Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE). (2024). Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) 2024–2041.

DENA (German Energy Agency). (n.d.). Smart Grids in Germany: Current Situation. Retrieved from https://www.dena.de/fileadmin/dena/Dokumente/Projektportrait/Projektarchiv/Entrans/Smart_Grids_in_Germany_Current_Situation_EN.pdf

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT). (2025). Annual Report on Electricity Statistics and Power Demand 2025.

Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT). (May 6, 2025). “Virtual Power Plant” — A New Technology for Enhancing Energy Security toward a Sustainable Carbon-Free Society.

Energy News Center (ENC). (February 25, 2025). “ERC prepares 10,000 million units of green electricity for the market.”

Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC). (February 2025). Feasibility of Achieving 24/7 Carbon-Free Energy Consumption.

Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO). (2024). Power Development Plan (PDP) 2024–2041.

Energy Policy and Planning Office, Ministry of Energy. (n.d.). Energy Policy Journal, Issue 134: Direct PPA and Green Electricity.

IEA (International Energy Agency). (2024). Renewables 2024. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org

IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency). (2024). World Energy Transitions Outlook 2024. Retrieved from https://www.irena.org

McKinsey & Company. (n.d.). The Future of Energy Transition in Asia-Pacific. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com

PV Magazine. (August 25, 2025). Peer-to-peer solar trading boosts returns and stability, say Australian researchers. Retrieved from https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/08/25/peer-to-peer-solar-trading-boosts-returns-stability-say-australian-researchers/

Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI). (July 25, 2025). “When the State is Slow… The Industrial Sector’s Survival amid Insufficient Clean Power.” Retrieved from file:///D:/Direct%20PPA/EEC-Final-Steering-Committee-1.pdf

Thai PBS. (November 19, 2024). “Policy Watch: Progress on the Liberalized Electricity Market and the UGT2 Program.”

Thansettakij. (April 18, 2024). “Apple increases global investment in clean energy and water initiatives.”

1/ The term Electricity Authority refers to the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA), and the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA).”

2/ Currently in the pilot phase in Thailand (Source: ERC Sandbox: Thailand’s Pilot Virtual PPA and How RECs and Virtual PPAs Can Further Its Decarbonization Goals).

3/ This business model operates on an interconnected platform that serves as an online marketplace where consumers and producers “meet” to trade electricity directly without the need for intermediaries.

4/ On November 7, 2022, the National Energy Policy Council (NEPC) approved the policy and guidelines for determining the Utility Green Tariff (UGT) rates. Subsequently, on June 14 and November 22, 2023, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) approved the regulations and tariff structure for the Utility Green Tariff, which were announced in the Royal Gazette on January 8, 2024. The tariffs are divided into two types: 1) UGT1 – Non-Source-Specific Utility Green Tariff, and 2) UGT2 – Source-Specific Utility Green Tariff. (Source: Public Hearing on the Draft Proposal for the Utility Green Tariff Rates, January 16–31, 2024.).

5/ Businesses pay the regular electricity tariff plus an additional premium charge, initially set at approximately 0.0594 baht per unit. Green electricity is sourced from existing renewable power plants in the system, making it suitable for businesses that wish to start using green electricity without complexity.

6/ Electricity users who wish to specify the source of green electricity are provided with Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) services from new renewable power plants. The government has established a new tariff structure that directly reflects the generation costs of those power plants, with a service contract period of 10 years.

7/ The Wheeling Charge refers to the cost of using the electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure of the Electricity Authorities.

8/ On Thansettakij. (April 18, 2024). Apple expands investments in clean energy and water initiatives worldwide.

9/ KPMG, Corporate PPAs: The Future of Renewable Energy Procurement in Asia-Pacific, 2023.

10/ Example: CKD Thai implemented a Solar PPA and reduced its electricity costs by approximately 25% (NC-net, 2024).

11/ Based on data from Solar Rooftop providers such as BCPG, SCG Clean Energy, and B.Grimm, the average PPA cost for factories and retail businesses is approximately 2.5–3.0 baht per unit, under long-term contracts (15–20 years) (Thansettakij, April 22, 2025).

12/ The Wheeling Charge applied in the UGT pilot project ranges from 0.25–0.30 baht per unit, in addition to the average electricity

13/ The cost of purchasing electricity from utilities (MEA/PEA/EGAT) is currently 3.99 baht per unit, plus the cost of purchasing RECs (Renewable Energy Certificates) ranging from 0.15–0.50 baht per unit (based on REC market data from I-REC in Thailand and Southeast Asia). generation cost from solar or wind power of 2.7–3.0 baht per unit.

14/ A cloud service developed by Microsoft, used to build, manage, and deploy various applications and services. It offers a wide range of tools and capabilities, including data processing, storage, and analytics.

15/ https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/thailand-board-of-investment-approves-two-more-large-data-center-projects/

16/ https://brandinside.asia/gunkul-murata

17/ The Thai government announced on September 29, 2025, its commitment to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, in response to global trade challenges and climate change. (Source: www.thaigov.go.th).

18/ The PDP 2024 places emphasis on the role of energy storage systems, which are essential for balancing the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power.

19/ Blockchain-based energy trading — for example, BCPG, in collaboration with the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) and Power Ledger, utilizes software to enable peer-to-peer solar energy trading between buildings.

20/ An advanced technology being developed by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) to integrate distributed renewable energy resources (DERs) nationwide into a new electricity ecosystem. This system enhances Thailand’s power stability and reliability, reduces dependence on fossil fuels, and supports the country’s goals of carbon neutrality and a sustainable low-carbon society. (https://www.egat.co.th/home/20250506-art01/)

21/ Refers to the change in electricity consumption behavior and patterns of users on the demand side, aimed at responding to system management requirements, fluctuations in electricity prices during specific periods, or incentive programs designed to encourage consumers to shift or reduce electricity usage during times of high prices or system reliability constraints. (Source: Smart Grid Thailand, https://thai-smartgrid.com )

22/ TDRI. (July 25, 2025). “When the State Moves Slowly… The Industrial Sector’s Survival Amid Insufficient Clean Energy.”

23/ Smart grids in Germany: Current situation” by Dena (German Energy Agency)

24/ https://greenreview.com.au/energy/australians-invited-to-join-peer-energy-trading/