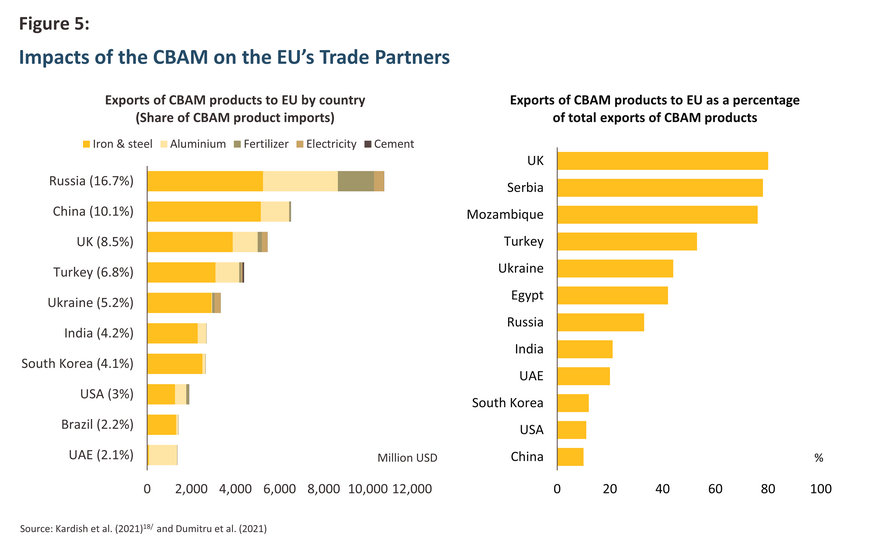

In addition to the extent to which an industry relies on exports to the EU, other factors that will influence the impacts of the CBAM include the carbon intensity of manufacturing processes, the ability of importers to pass on higher costs to exporters, and the existence of and access to alternative markets for both importers and exporters. However, the costs associated with the CBAM could also be lessened if export-originating countries set a domestic price for carbon and introduce measures to tighten emissions.

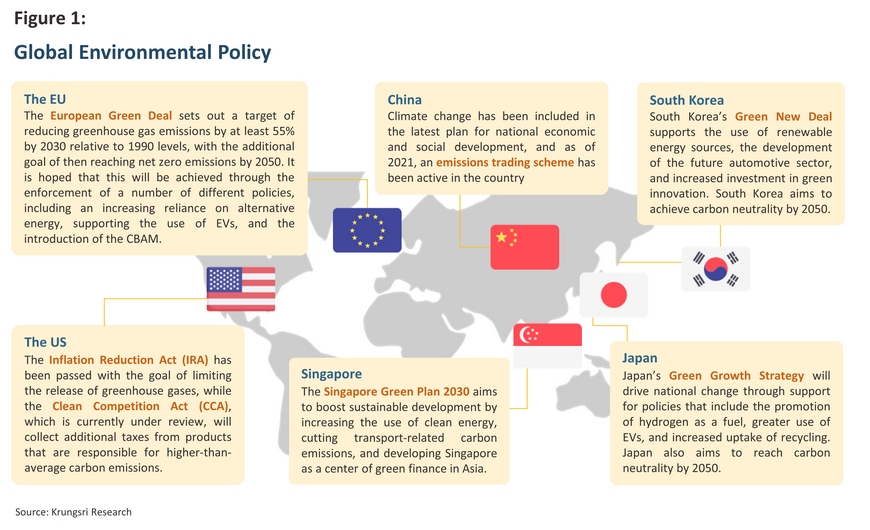

Going forward, the move by the EU to introduce a CBAM has encouraged many other countries to consider developing their own equivalents. This is most evident in the US’s CCA, though in the UK, the government is also consulting on measures to reduce carbon leakage, including through the introduction of a proposed UK-CBAM and of mandatory product standards (MPS), which will help to create a regulatory environment best suited for the reduction of carbon emissions from industry20/. Other countries involved in this process include Canada, which is now officially consulting on its CBAM21/. What is sure to be a growing use of these measures will therefore have potentially significant impacts on global manufacturing and trade, and countries that are home to the least environmentally friendly industries will increasingly feel the pressure to bring these into line with emerging trends to green global production.

Although the initial enforcement of the CBAM, which begins in October 2023, will be restricted to a transition period during which importers will be required to report carbon emissions but not to purchase CBAM certificates, this will still impose additional costs on Thai manufacturers and exporters due to the required emissions checks and accompanying paperwork. In addition, over the long term, these costs will likely broaden, especially in the event that Thai players are not able to bring their production processes and operations into line with new global standards. The expected impacts of the CBAM on Thai industry are summarized below.

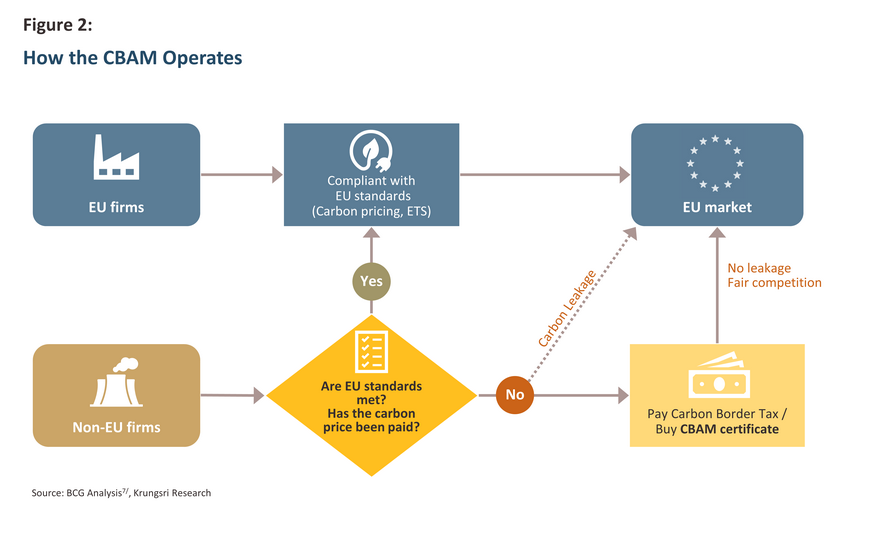

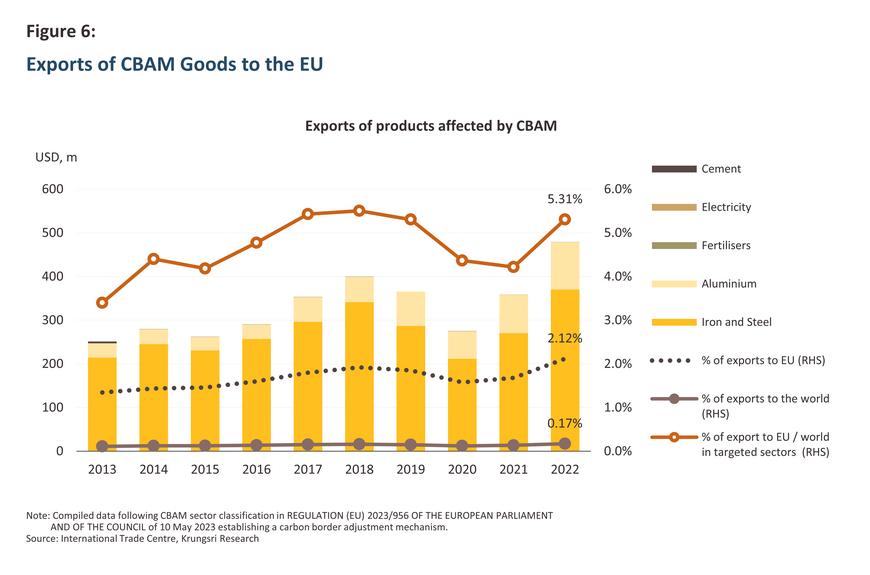

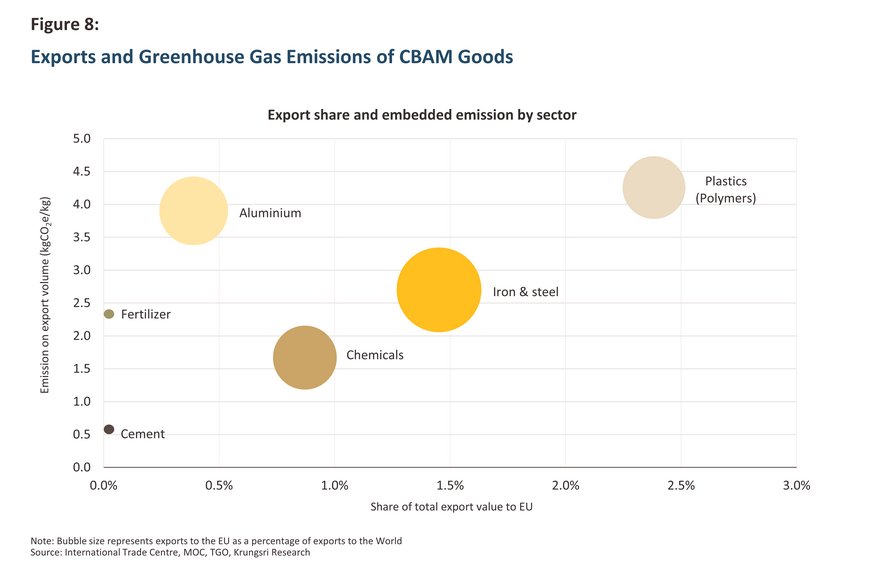

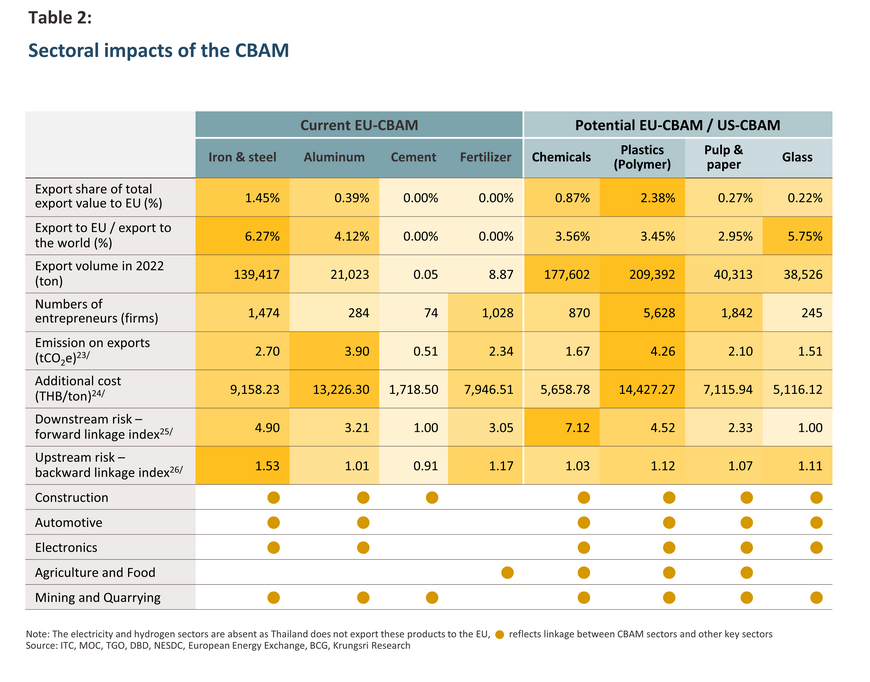

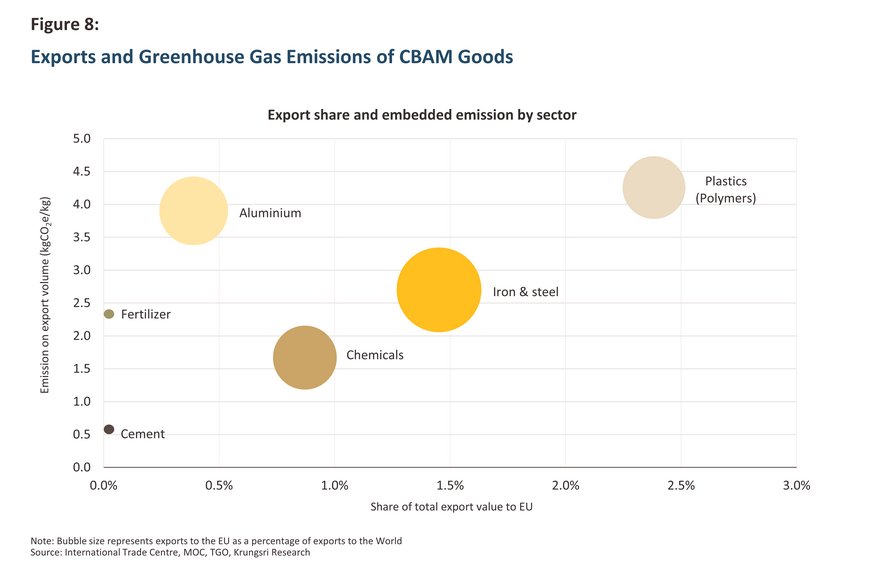

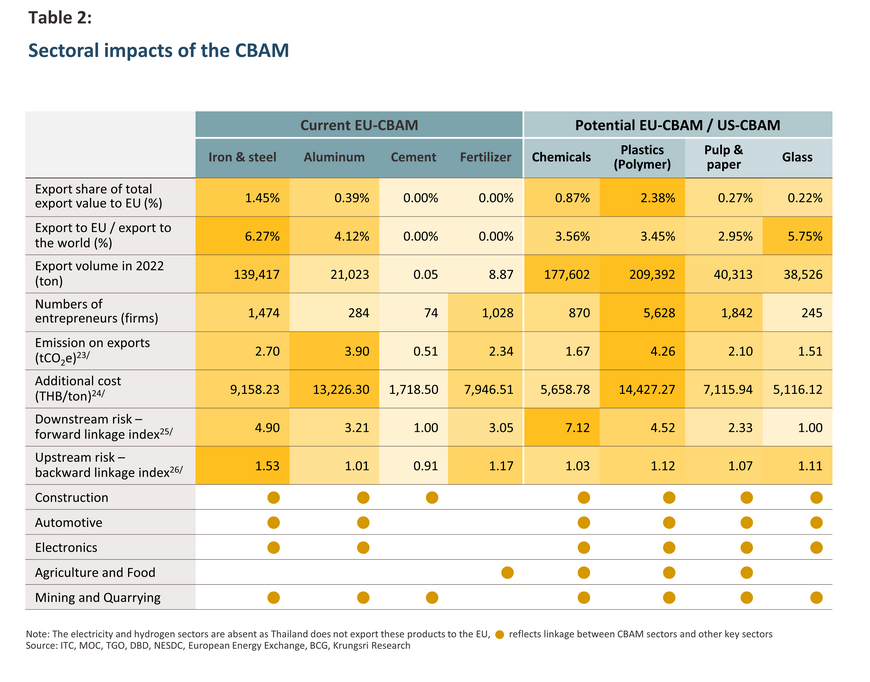

It is highly likely that the charges that the CBAM will put in place for the importing of high-emitting products will be passed on by importers to manufacturers and exporters, and so the mechanism will add to export costs for those selling into markets in the EU. These additional costs will come from both direct sources, that is for charges levied on excess emissions, and indirect sources, that is for measuring and reporting emissions and for paying for associated paperwork. Nevertheless, over the short term, the impacts of this on the Thai manufacturing sector are expected to be only slight because exports to the EU of goods covered by the CBAM regulations account for just 2.1% by value of all Thai exports to the bloc, and just 0.17% of all Thai exports in total. Among the CBAM goods exported to the EU, the most important for Thailand are iron and steel (1.5% of exports to the EU) and aluminium (0.4% of exports), while sales to EU customers of other CBAM goods are either very low or non-existent. Moreover, as a share of all exports from Thailand of CBAM goods, those going to the EU represent just 5.3% of the total, underlining the fact that at least for these product categories, the EU is not a major market. This thus puts Thailand in a very different position to countries such as the UK, Serbia, and Mozambique, which as described above, are much more exposed to the potential negative impacts of the CBAM.

Industry-level impacts in Thailand

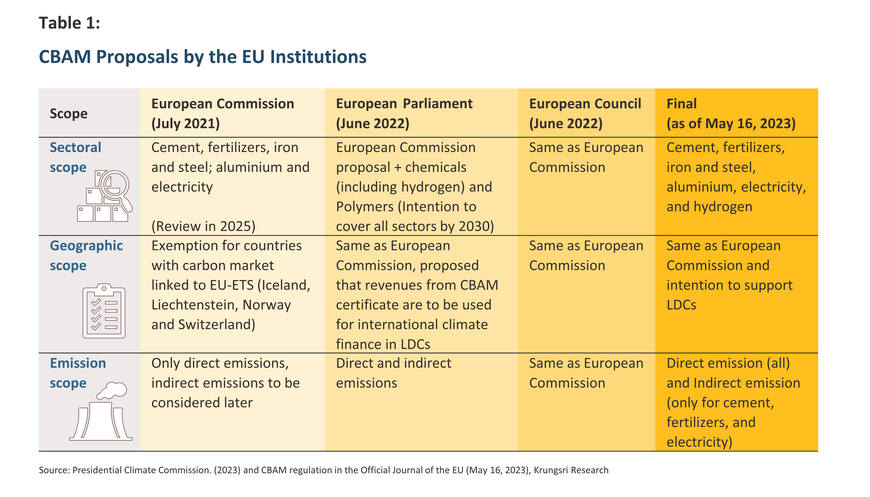

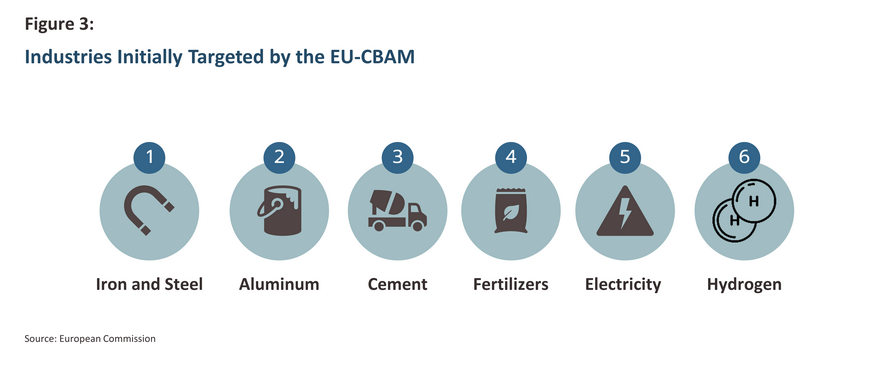

Clearly, the impacts of the CBAM will differ across the economy depending on a broad set of variables including the size of an industry’s export sector, its reliance on exports to the EU, the structure of its manufacturing supply chains, and its carbon intensity and the quantity of greenhouse gas emissions for which it is responsible. In the following, a comparative analysis of these impacts is therefore given for industries targeted by the CBAM. It is hoped that this will present a clearer picture of how the introduction of the CBAM will affect these various industries.

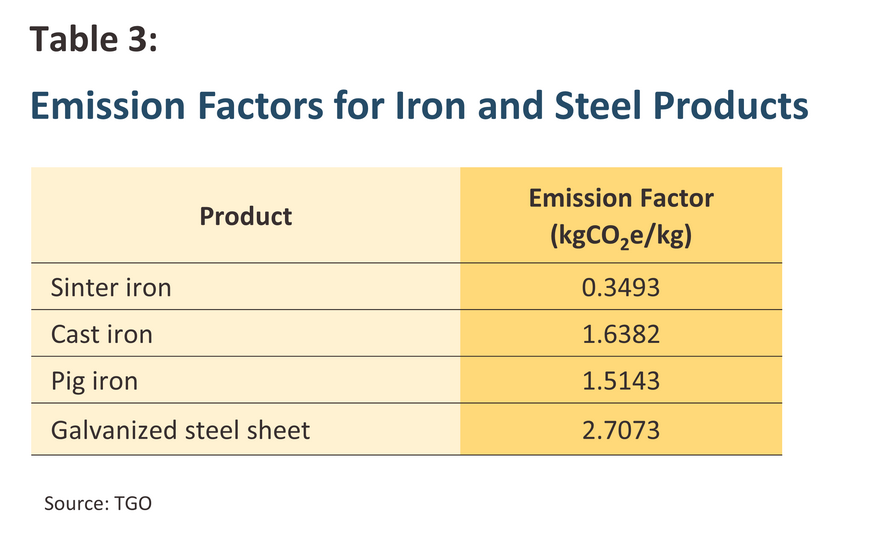

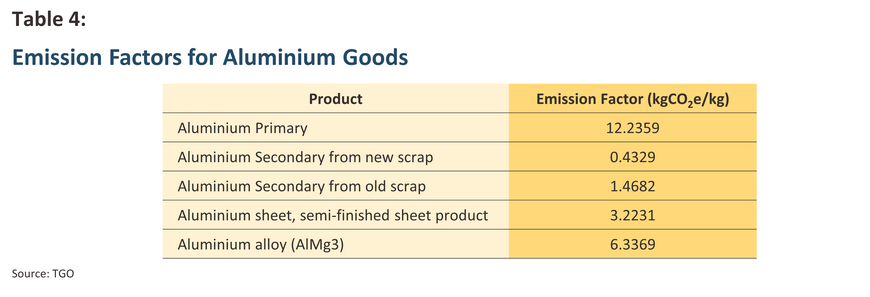

The introduction of the CBAM will have the most serious consequences for the iron and steel industry (including downstream steel products). This will be because compared to other CBAM goods, at 6.3% of sales, Thai iron and steel exports are more heavily dependent on markets in the EU. In addition, the industry is also very carbon intensive, and after plastics and aluminium production, it has the highest per unit emissions of greenhouse gases. Next in line will be the aluminium industry, which will be the second most seriously affected part of the Thai economy. Although the EU is a less important market for aluminium producers than it is for exporters of iron and steel goods, the industry is more carbon intensive and so the marginal costs associated with imports are likely to be higher. However, examination of the forward and backward linkage indices shows that the aluminium industry is less heavily integrated with other parts of the economy than is the iron and steel industry, which indicates that for the aluminium manufacturers, enforcing the CBAM will have fewer impacts on either upstream or downstream supply chains. Within Thailand, other industries targeted by the CBAM will be largely unaffected by its introduction because either exports to the EU are low and represent only a small proportion of overall sales (as is the case for cement and fertilizer) or there are no exports to the EU at all (as is the case for electricity and hydrogen production).

Despite the relatively mild impacts that are forecast, worries persist that in the future, any widening of the scope of the CBAM may have more far-reaching consequences for Thai industry, especially if the rules on imports are expanded to include chemicals and plastics. This was in fact suggested in discussions in the European Parliament but the proposal was later dropped. The inclusion of plastic products and polymers in the CBAM measures would be particularly troubling for Thailand since compared to iron and steel, exports of these to the EU are more substantial, and accounts for a larger proportion of total sales to the bloc. These goods are also strongly associated with a high level of direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions, and so the industry is keeping a close eye on developments.

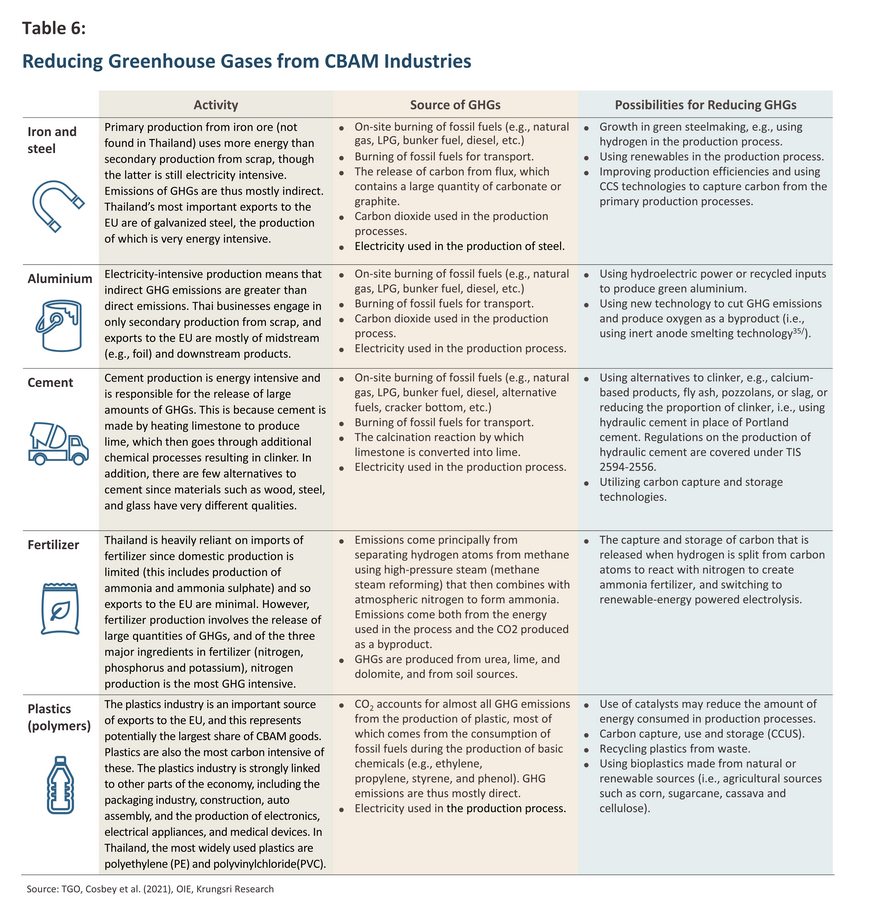

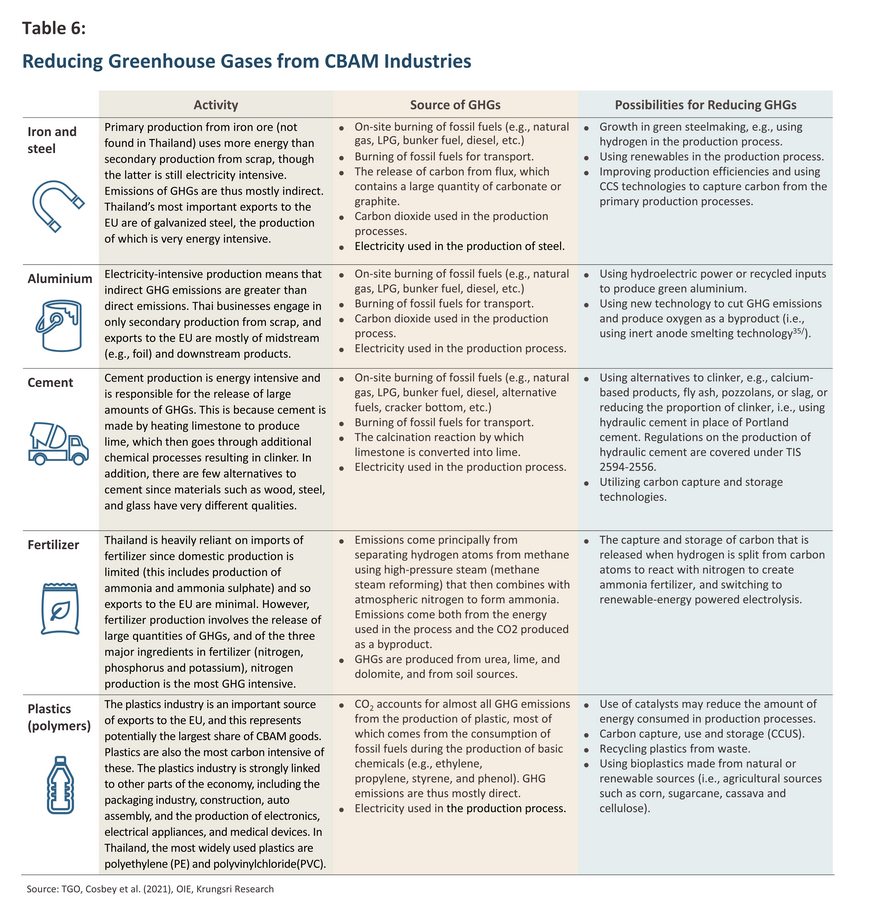

Details on the industries expected to be most heavily affected by the CBAM, the likely consequences of this, and ways in which they might reduce their greenhouse gas emissions are detailed below.

Iron and steel

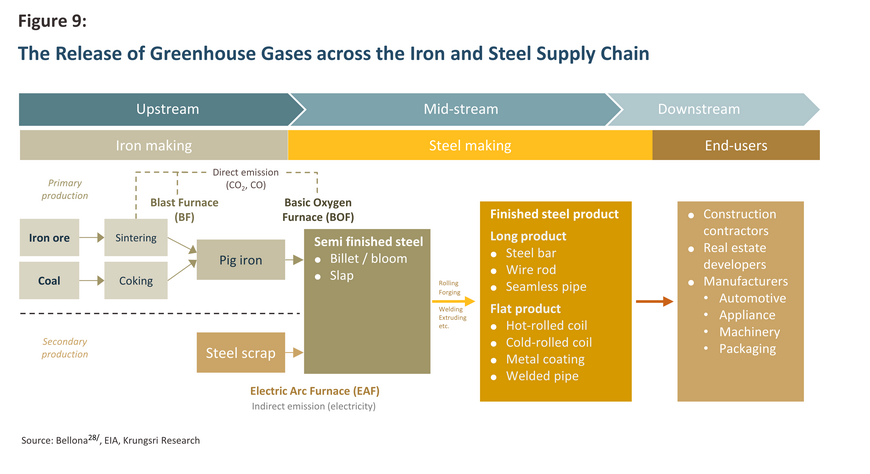

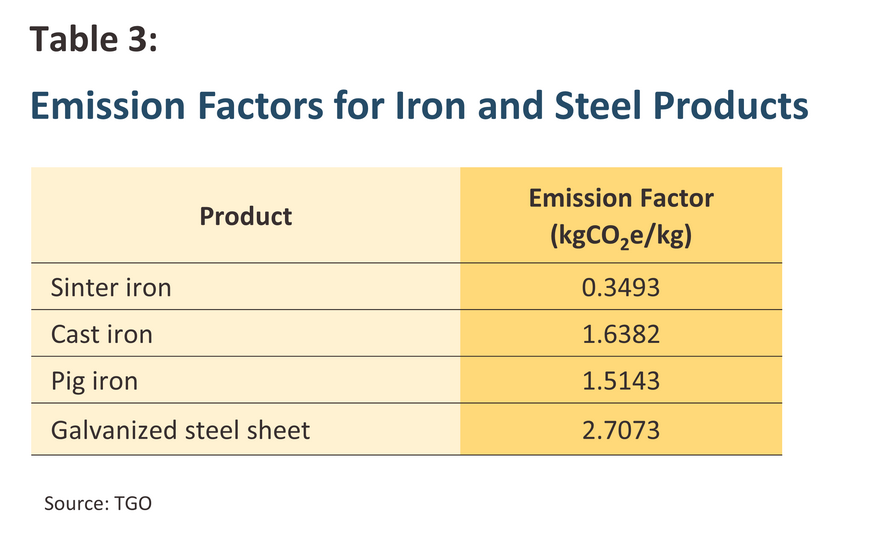

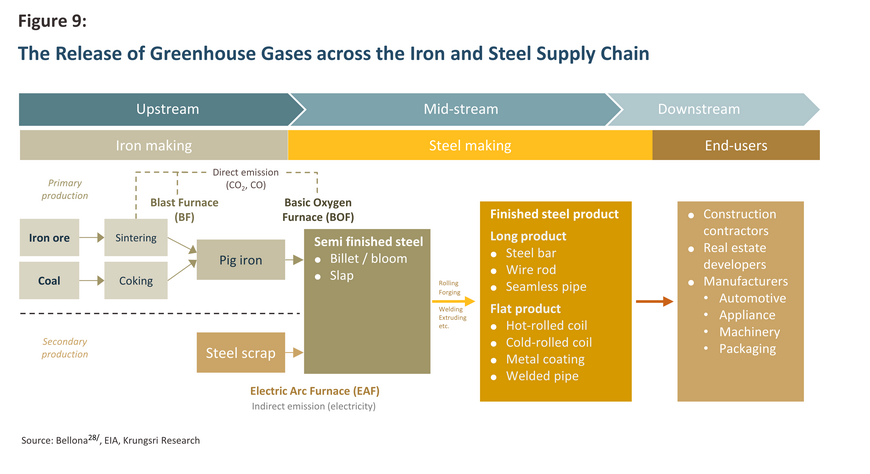

The iron and steel industry is a major consumer of energy, with upstream production of pig iron or iron inputs generally relying on one of two methods. (i) Primary production involves the processing and melting of iron ore in blast furnaces, which is then transformed into pig iron in basic oxygen furnaces. Each of these stages entails the release of significant quantities of carbon, and typically, primary processing of iron ore is responsible for the release of 2.3 tonnes of carbon for every 1 tonne of iron that is produced27/. However, this type of processing is not carried out in Thailand. (ii) Secondary production involves the smelting of scrap and the direct rolling of steel in electric arc furnaces, which also leads to the indirect release of a large quantity of greenhouse gases. Midstream parts of the iron industry convert iron into steel, outputting semi-finished steel products, which then passes through additional downstream processes to be turned into finished products such as sheet steel or steel bar.

In addition to raw iron and steel, the goods covered by the CBAM include products made from these (e.g., nails, nuts and bolts, containers, packaging, etc.) and for Thai exporters, these comprise the most important category of goods sold into the EU; in 2022, 69,000 tonnes of these were shipped from Thailand to buyers in Europe. These were followed in importance by rolled stainless steel products, of which 26,000 tonnes were sold to the bloc. In terms of the greenhouse gas emissions connected to lifecycle production and use (i.e., a product’s emission factor), galvanized steel (used to prevent rusting) is the worst offender, and so it is evident that a high proportion of the steel products exported to the EU from Thailand carry with them heavy per-unit carbon costs.

However, efforts are underway to shift businesses towards green steelmaking and thus to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of the iron and steel industry. One example of this is the development of hydrogen-based steelmaking, which should be commercially feasible by 203029/, and indeed the Chief Executive Officer and founder of Singapore’s Meranti Steel, a driving force in the move to sustainable steel production, estimates that global demand for green steel will reach 41 million tonnes by 2025 and 235 million tonnes by 2040. Likewise, demand for low-polluting products is forecast to jump from 1% of total demand for flat steel products to 26%30/. This type of transformation of the market may be possible over the long term, but in the short term, manufacturers will need to cut direct emissions of greenhouse gases from primary production processes through the use of carbon capture and storage technologies (CCS), while problems with excessive indirect emissions can be addressed through increased energy efficiency and the switch to renewable sources of energy.

Aluminium

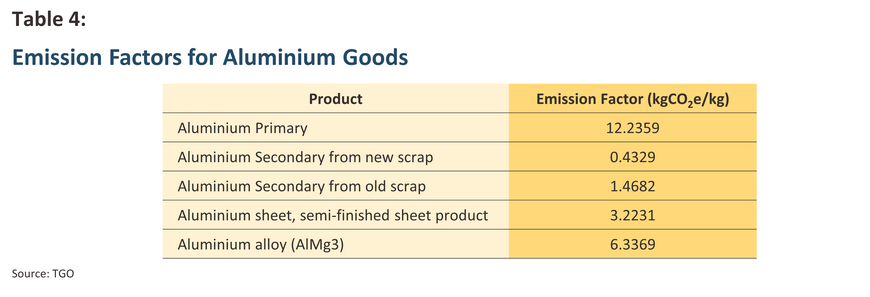

In its initial production, aluminium is the most energy hungry of all non-ferrous metals due to the large quantities of electricity that this process consumes (this is thus an indirect source of greenhouse gases). As with iron, there are two methods for manufacturing aluminium. (i) Aluminium can be produced from bauxite, which is smelted to produce alumina powder, and an electrical process is then used to transform this into aluminium. However, because Thailand has no bauxite mines, this process is not employed domestically. (ii) aluminium may also be made from scrap, and because this uses only 5% of the electricity of producing aluminium from bauxite31/, this is a popular route to take. The emission factor for the second technique is thus significantly lower than for the first, and so producing aluminium from scrap will have an important role to play in reducing industry emissions.

In 2022, the most important category of aluminium exports from Thailand to the EU was aluminium foil, a midstream product for which sales totaled 9,900 tonnes. This was followed in importance by ‘other’ downstream aluminium products (2,400 tonnes). Nevertheless, when the CBAM is first enforced, although it will apply to downstream aluminium goods, indirect emissions will not be counted when calculating the total embedded emissions of aluminium, iron, and steel products. Over the short term, costs will therefore not rise substantially.

Over the longer term, a transition to the production of ‘green aluminium’ will play an important part in reducing the industry’s release of greenhouse gases. This is because green aluminium is produced from alternative energy (often from hydroelectric power) and so the manufacturing process typically produces less than 4 tonnes of carbon for every 1 tonne of aluminium, or less than a quarter of the average 16.6 tonnes of carbon released per tonne of aluminium when standard production processes are used. Moreover, output is rising, and this is expected to jump by 10% in 2023 alone. Among other beneficiaries of this will be the auto industry since aluminium is widely used in the manufacture of auto parts (e.g., for the production of bumpers) and so using green aluminium will help to reduce the carbon intensity of downstream goods such as this32/.

Plastics

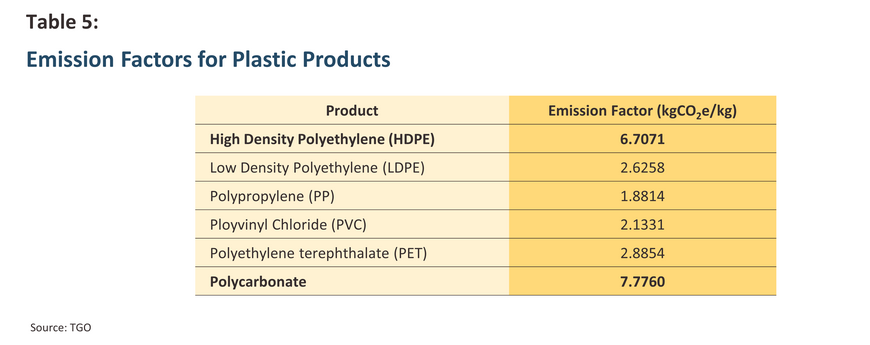

Although at present, plastic products have not been included within the scope of the CBAM rules, this was in fact proposed by the European Parliament, and because plastics are both the most important of the potential CBAM goods exported from Thailand to Europe and the most carbon intensive, any move to expand the mechanism to cover these would have substantial consequences for Thai industry. The impacts of such a move would be amplified by the fact that the plastic industry is tightly linked to many other parts of the economy, including the manufacture of packaging, construction materials, automobiles, electronics, electrical goods, and medical devices. Some of the plastics that are most widely used include polyethylene (PE)33/, which is used in the manufacture of products such as bags, bottles, buckets, and film, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is used in construction and domestic settings (e.g., for water pipes and connections, and cabling).

Plastics production begins with the refining of crude oil or the distillation of natural gas, and the outcome of these processes is then separated into basic chemicals including ethylene, propylene, styrene and phenol. These are used as precursors in the production of plastic resins. Following this, the plastic products themselves are manufactured by melting plastic pellets and then using processes such as blowing, injection molding, pressing, rolling, and so on to form the plastic into the desired shape. Almost all of the greenhouse gases associated with the production of plastics is released as carbon dioxide that comes from the fossil fuel-derived power used to isolate the basic chemicals. Embodied emissions are thus mostly direct, though plastic production also consumes a significant amount of electricity and this is therefore a sizeable additional source of indirect emissions.

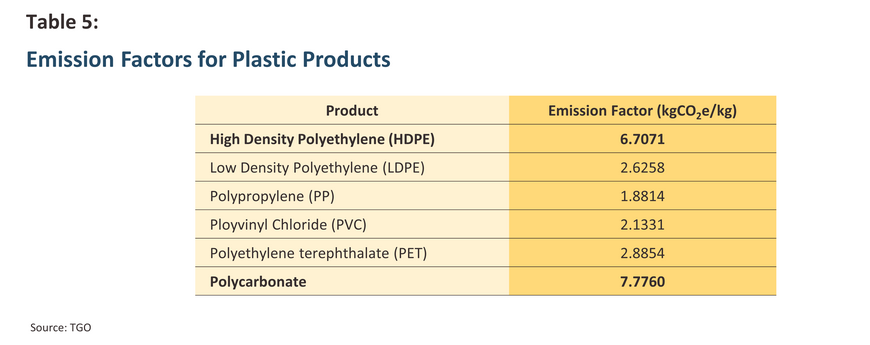

A consideration of the emission factor of different plastics shows that among those most widely used in Thailand, polycarbonates used in the auto and medical devices industries and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) have the highest per unit greenhouse gas emissions. In 2022, a major share of Thai exports to the EU of plastics came from sales of high- and low-density polyethylene (HDPE and LDPE) and of plastic bags and packaging also manufactured from polyethylene. Thai manufacturers and exporters are thus exposed to a significant risk that in the future, the high carbon emissions that these products are responsible for will translate into higher costs.

A number of different routes may be taken to reduce emissions from the production of plastics, including the use of catalysts to cut the amount of energy used in the manufacturing process, and taking advantage of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies. In addition, it will be possible to cut carbon emissions by substituting regular plastics with alternatives, including recycled plastics manufactured from waste products and bioplastics made from natural products. The latter includes renewable resources and agricultural products (e.g., cellulose fiber, collagen, flour, and bean proteins), and because bioplastics are biodegradable, they are regarded as more environmentally friendly than regular oil-based plastics. These also offer the advantage of being able to be used in roles as varied as food packaging and medical applications (e.g., as artificial skin)34/.

Exports from Thailand to the EU of other goods covered by the CBAM regulations (i.e., cement and fertilizer) are very limited and so the associated greenhouse gas emissions are likewise negligible. In the case of cement, emissions come mainly from heating limestone to produce clinker and so emission reduction efforts are focused on replacing clinker and promoting the use of hydraulic cement in place of Portland cement. For fertilizers, greenhouse gases are produced mainly during the splitting of hydrogen from methane, which is then combined with atmospheric nitrogen to produce ammonia (i.e., nitrogen fertilizer). However, Thailand is an importer of fertilizer and with only minimal exports, the environmental consequences of Thai production are very limited.

Table 6 below summarizes details on the primary activities of industries targeted by the CBAM, how these are responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, and how these emissions may be reduced.

How prepared is Thailand for the rapidly approaching introduction of the CBAM?

Having looked at the likely impacts of the CBAM, it is natural to then ask ‘How prepared is Thai industry for this?’, though any answer to this question must take into account not just the impacts of the EU’s CBAM but also the likely future introduction of similar mechanisms by other countries. Consideration of the structure of the CBAM shows that the costs that will arise from it will be strongly influenced by how players respond to three particular challenges.

Challenge 1: Measuring carbon emissions

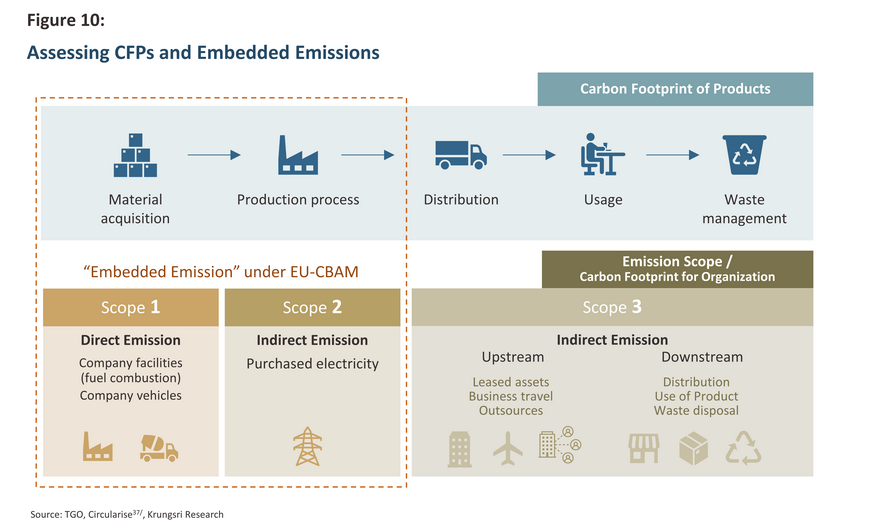

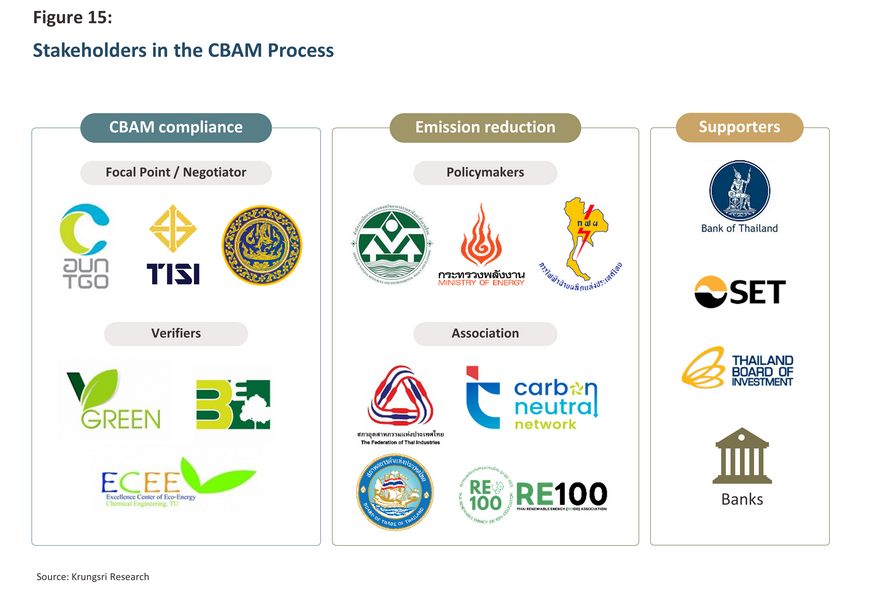

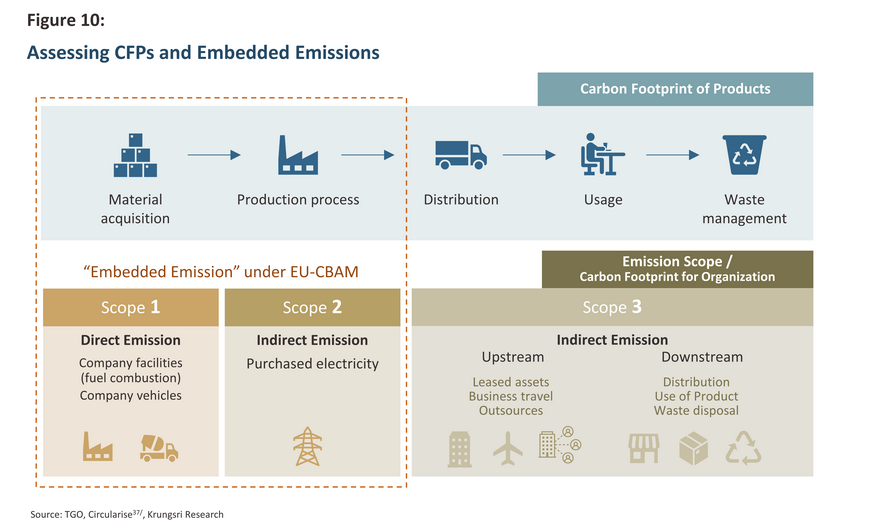

The most important variable influencing the costs arising from the introduction of the CBAM is the extent of embedded greenhouse gas emissions associated with particular products because this will determine the cost of CBAM certificates. Thailand has already begun work on the development of systems for the measurement of greenhouse gas emissions, and these may now be adapted for use in measuring CBAM embedded emissions. This includes the ‘carbon footprint of product’ (CFP) mark, which has been designed to reflect an assessment of a product’s complete lifecycle emissions, from sourcing inputs and raw materials, through production, distribution and use, to end of lifecycle disposal. This will then help to communicate to consumers that particular products are (or are not) environmentally friendly. Manufacturers are able to request certification from the Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization (TGO), though producers are responsible for calculating the carbon footprint of products, which they may do themselves or they may contract out to a consultant. These assessments are then subject to verification by certified individuals or organizations and, following this, confirmation and certification by the TGO36/.

It is important at this stage to be clear about how far the CFP and the CBAM’s definitions of embedded emissions overlap, and comparing how these two procedures assess the greenhouse gas emissions associated with particular products, clear differences emerge. Thus, CBAM embedded emissions measure only those direct and indirect (i.e., from electricity use) emissions that result from the production process itself38/, and so the total lifecycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions required under the CFP is much wider than the CBAM assessment of embedded emissions.

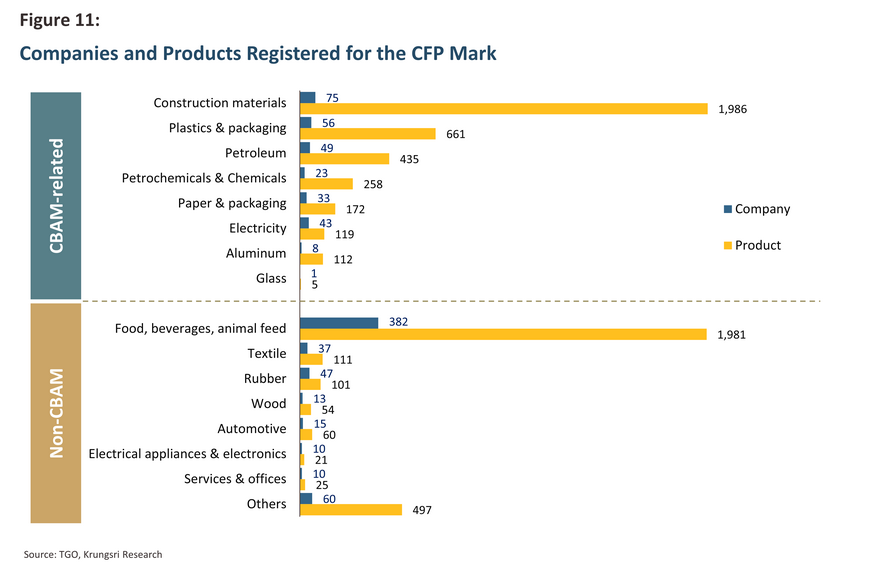

The CFP doubtless marks a positive start for Thailand since in addition to preparing the way for measuring and verifying carbon emissions, the CFP has also been included in the list of recognized marks in the Thai Rating of Energy and Environmental Sustainability (TREES), a green building assessment, and in the Thai Green Card list, which is used to measure products’ environmental friendliness and which is gaining popularity among consumers. However, the costs of measuring and verifying emissions and then of registering with the CFP are significant39/, and worse, registration is valid for only two years, at which point the verification and registration process needs to be repeated. This may be one reason why registrations are at present somewhat limited.

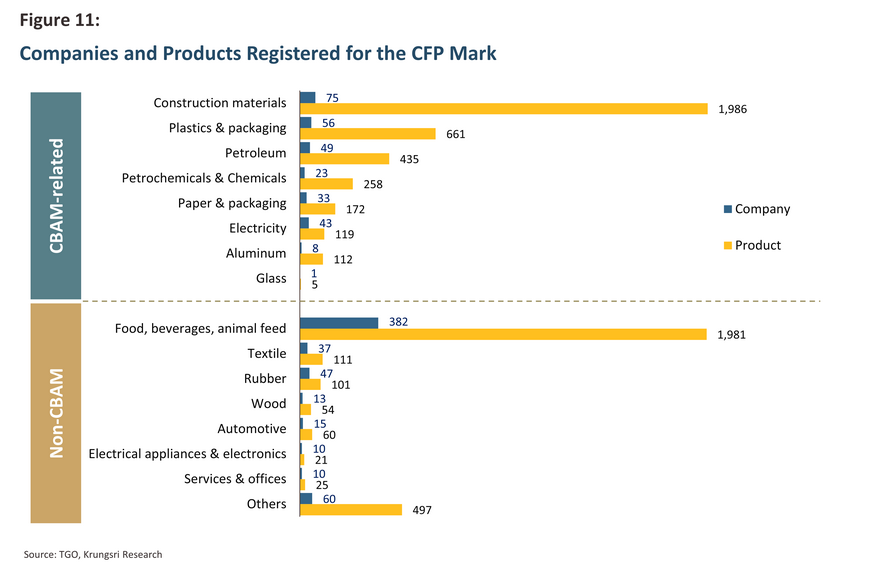

As of 13 June, 2023, a total of 7,122 products produced by 820 companies had been registered for the CFP mark, though of this total, only 2,872 products from 268 companies still had an active registration. With 1,986 products, construction materials (including steel and cement) were the most heavily represented in the historical total, followed by food and drink products. Interestingly, comparing on the one hand goods that are currently or that are likely to be covered by the CBAM regulations and, on the other those that are outside the scope of the regulations, the former are more heavily represented in CFP registrations than the latter. This is especially the case for construction materials, plastics, chemicals, petroleum products, and petrochemicals. Nevertheless, as a share of all businesses active in particular industries, those registered with the CFP represent only a very small fraction of the total. At 4.8%, this share is highest for producers of construction materials, falling to 2.7% for producers of aluminium, and around just 1.0% for manufacturers of plastics. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that many manufacturers are not yet prepared for official testing and verification of their greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition to differences between how the Thai and EU systems measure emissions, an additional issue involves the standards, systems and personnel involved in verification processes. The EU has specified that independent auditors verifying greenhouse gas emissions must be registered either with the EU ETS or with the national accreditation bodies of individual member states. The Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization (TGO) and the Thai Industrial Standards Institute (TSI) are jointly developing Thailand’s measurement and verification systems in line with the standards established by the EU, and it is hoped that this will result in the creation of a digital platform that can be used to calculate embedded emissions as defined by the CBAM. Alongside this, personnel with expertise in measuring and verifying emissions are also being trained in how to follow these standards, and in the near future, there is likely to be significant demand for these skills. The development of these native Thai systems for measurement, reporting and verification will help to reduce the costs faced by exporters, with the additional advantage that rather than divert funds to overseas organizations, any such expenditure will remain within Thai borders.

Challenge 2: Using domestic carbon pricing to reduce the costs connected with the CBAM

The CBAM regulations specify that if an importer can show that the cost of goods brought into the EU already includes payments relating to the release of carbon during the production process, these can be set against the fee for the CBAM certificate that importers need to buy. Thus, if the originating country has introduced an effective carbon pricing mechanism that operates in line with the EU principles, this can help to cut costs arising from the introduction of the CBAM.

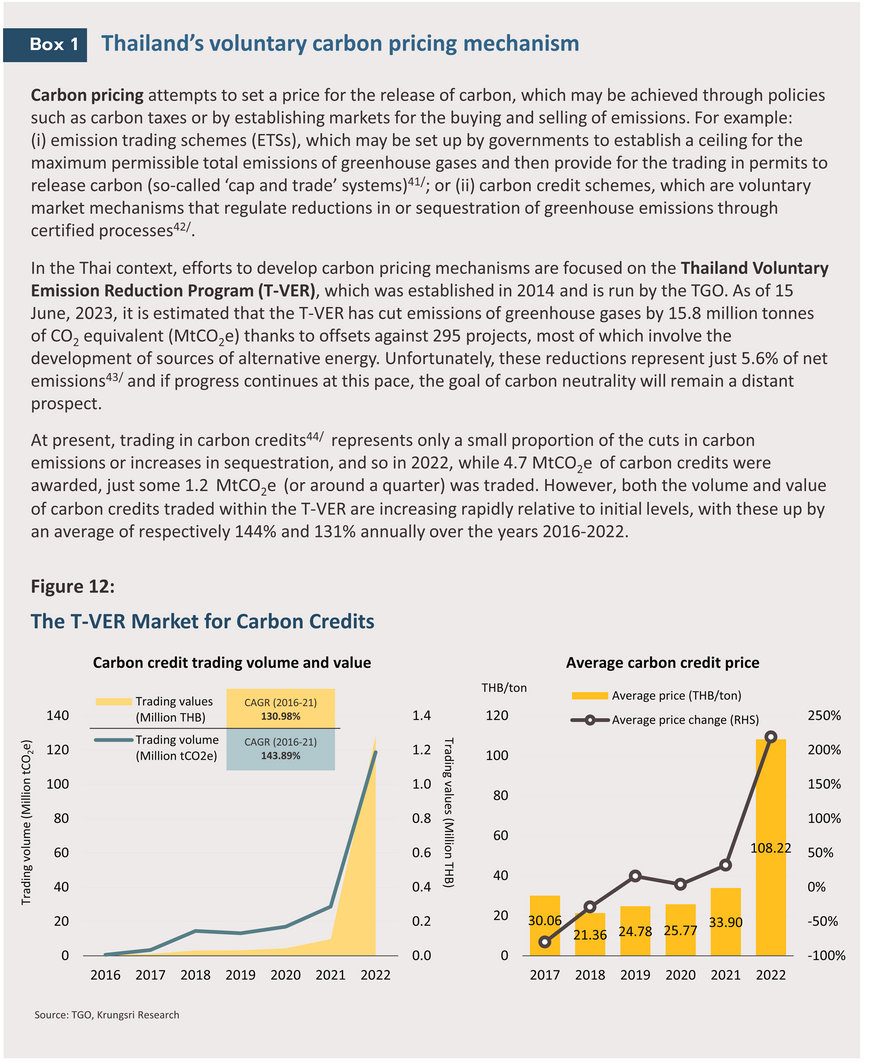

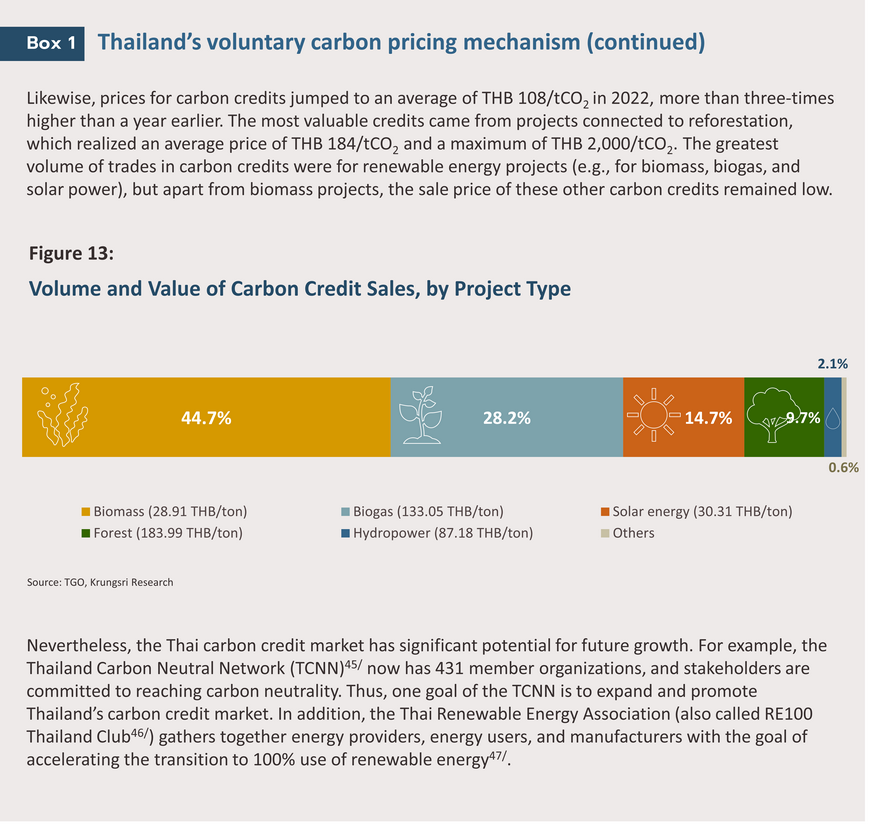

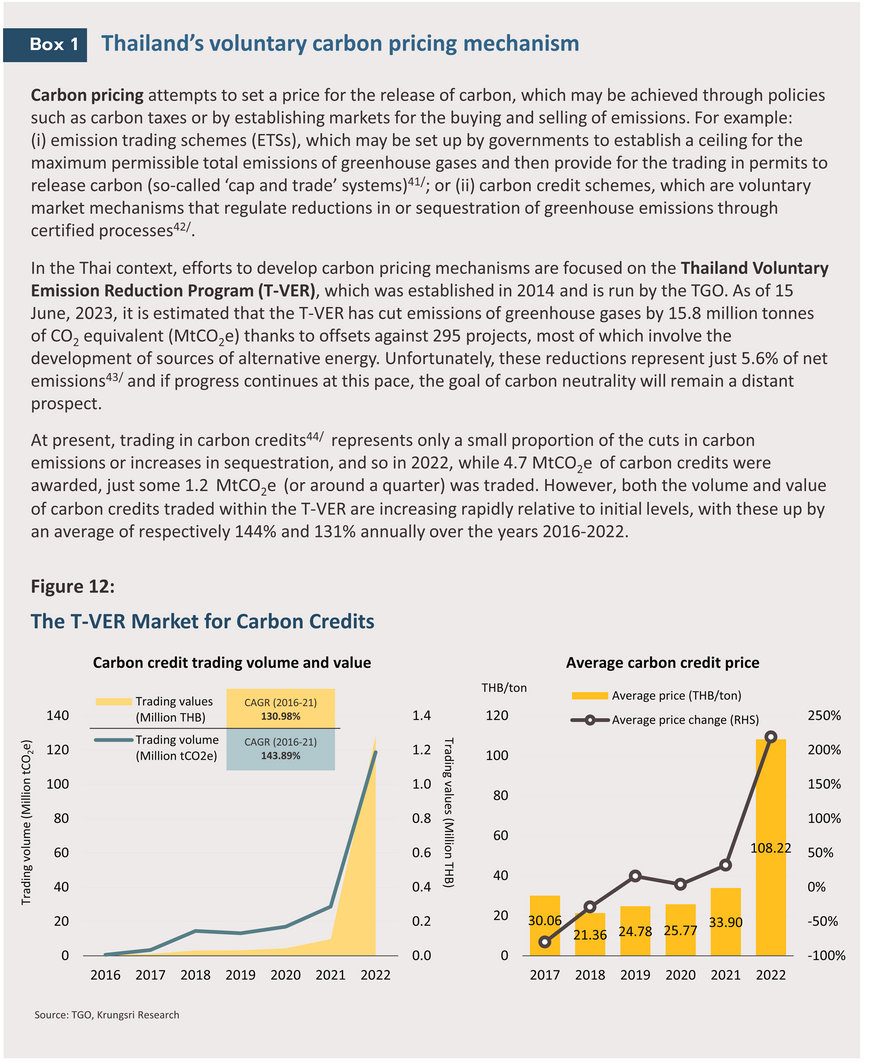

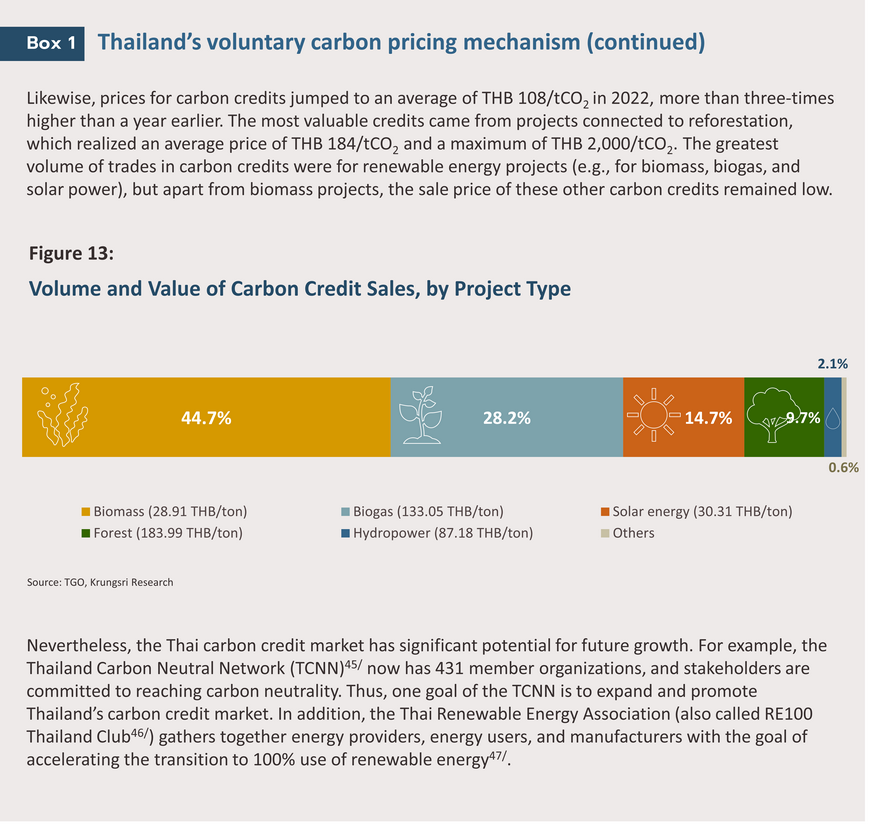

At present, Thailand’s market for carbon credits takes the form of the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Program (or T-VER), though this remains somewhat small. Carbon prices thus averaged just THB 108/tonne of CO2 in 2022, and relative to the total approved issuance of carbon credits, sales are still low. This is partly a result of the fact that participation in the market remains voluntary and so the incentives encouraging businesses to participate are weak. In addition, understanding of how carbon markets work and what benefits they offer is not yet widespread, while the costs of registering with the T-VER and of requesting carbon credits, as well as of measuring, assessing, and verifying emissions can be substantial40/. Nevertheless, given the need to reach carbon neutrality, the Thai market for carbon credits has potential for rapid growth on both its demand and supply sides, and when the market has improved in terms of both quantity and quality, this may help to reduce the costs faced by Thai exporters when purchasing CBAM certificates. In light of these clear potential benefits, agencies involved in the development of these areas should accelerate negotiations with the EU to bring the T-VER program, or other domestic carbon pricing mechanisms in the future, into line with the requirements imposed by the CBAM.

Challenge 3: Transitioning to a low-carbon economy

In addition to short-term efforts to cut the costs required to meet the CBAM standards by improving measurement and verification systems and developing domestic carbon pricing mechanisms, as described above, over the longer term, it will be more important to cut greenhouse gas emissions connected to economic activity. This will then accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy, which would necessarily be the most efficient way of cutting embedded emissions.

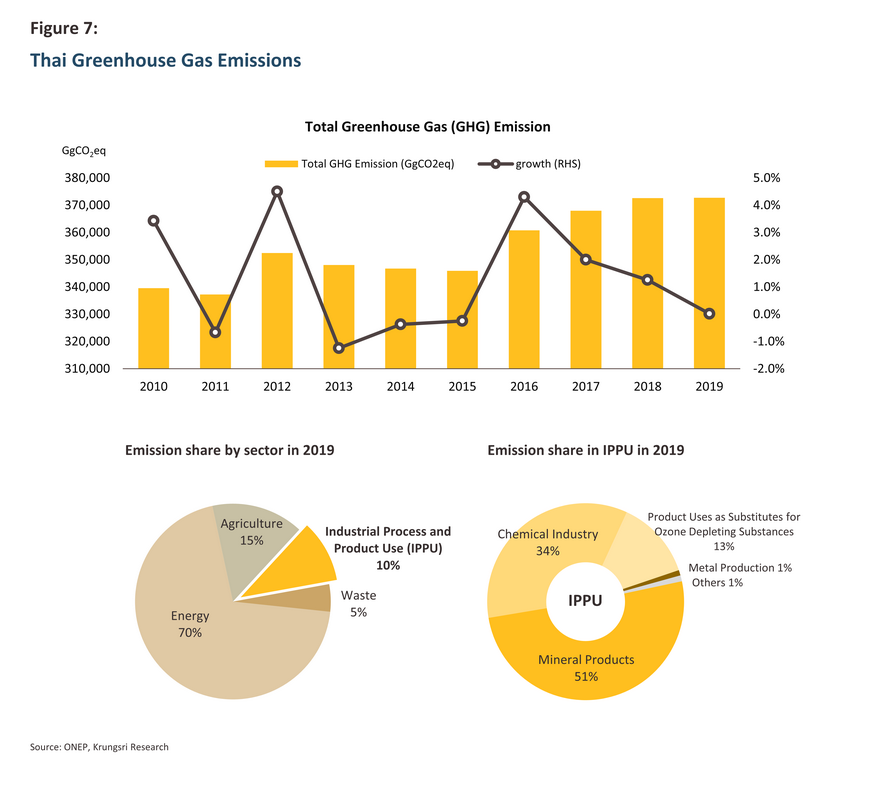

The next issue to address is therefore considering where Thailand currently stands with regard to the goal of becoming a low-carbon economy. Thailand’s ‘Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategy (Amended Version)’, produced by the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (part of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment) was submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)48/ in 2022. This estimates that to reach net zero emissions, Thailand’s emissions should be no more than 120 MtCO2e by 2065, which allowing for sequestration by forests would result in zero net emissions. Unfortunately, as of 2019, Thailand’s total emissions came to 373 MtCO2e, or more than triple the target and because the country remains so far from achieving its goals, efforts in that direction will doubtless need to be accelerated. However, as things stand, Thailand lacks the explicit regulatory framework required to drive the transition to a low-carbon economy, though efforts have been made to draft a climate change bill. If the latter is passed in the near future, this would certainly help to increase pressure across all parts of the economy, pushing stakeholders to step up their efforts to control carbon emissions and to jointly bring the net zero goal much closer to fruition49/.

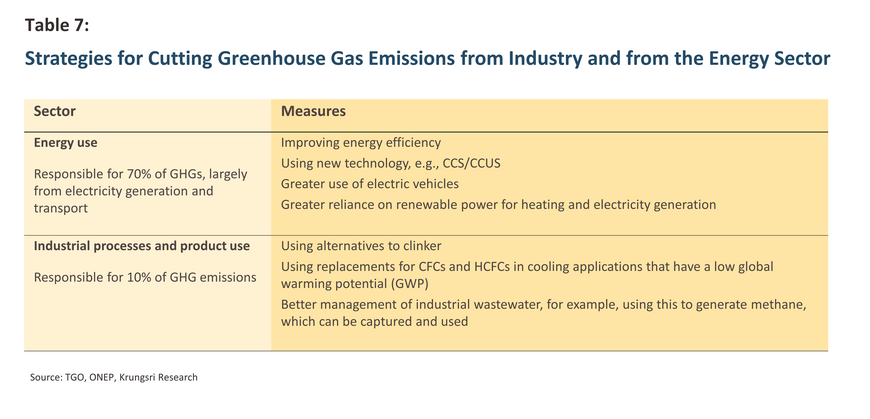

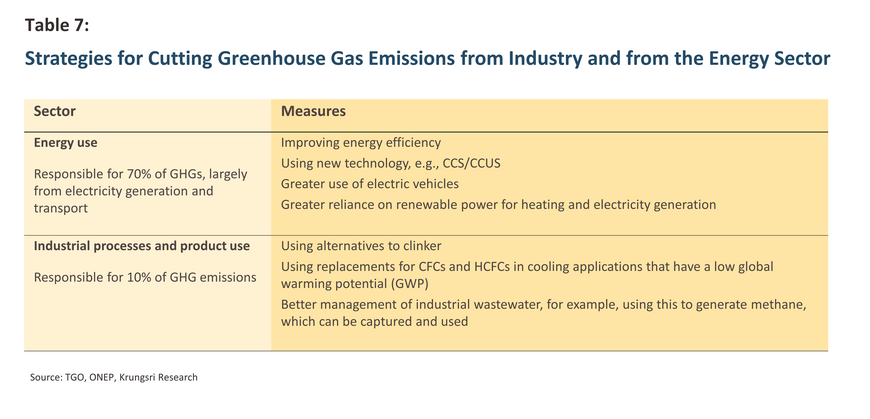

Given the tendency of different sectors to generate different levels of greenhouse gas emissions, Thailand’s long-term strategy for addressing these issues focuses on cutting emissions from industries affected by the CBAM directly, that is, the energy sector and carbon-intensive industrial processes. This strategy therefore involves exploiting alternative energy sources, greater use of EVs, and intensified research and development of related technologies, such as carbon capture and storage, and these measures will then help to reduce both direct and indirect emissions, as the CBAM intends. In addition, measures unique to particular industries are also being pursued, so for example, cement producers are developing alternatives to clinker. However, such alternatives have yet to emerge in the iron and steel and aluminium industries, partly because in these areas, emissions largely originate from the electricity and fossil fuels used in production, and these are already accounted for in the energy sector.

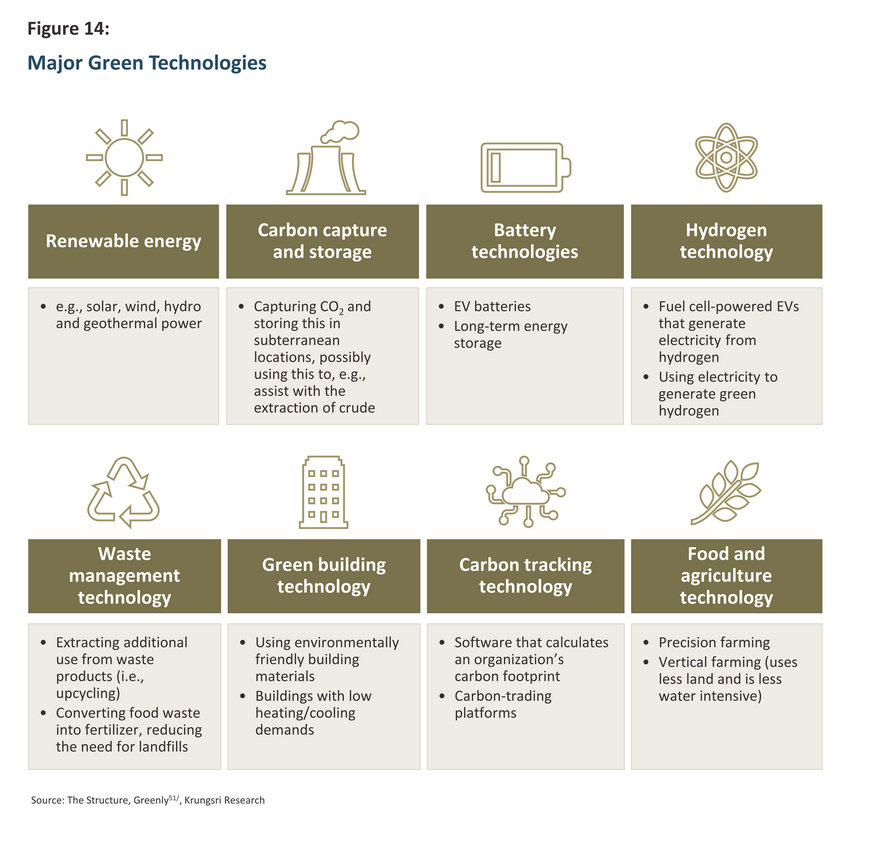

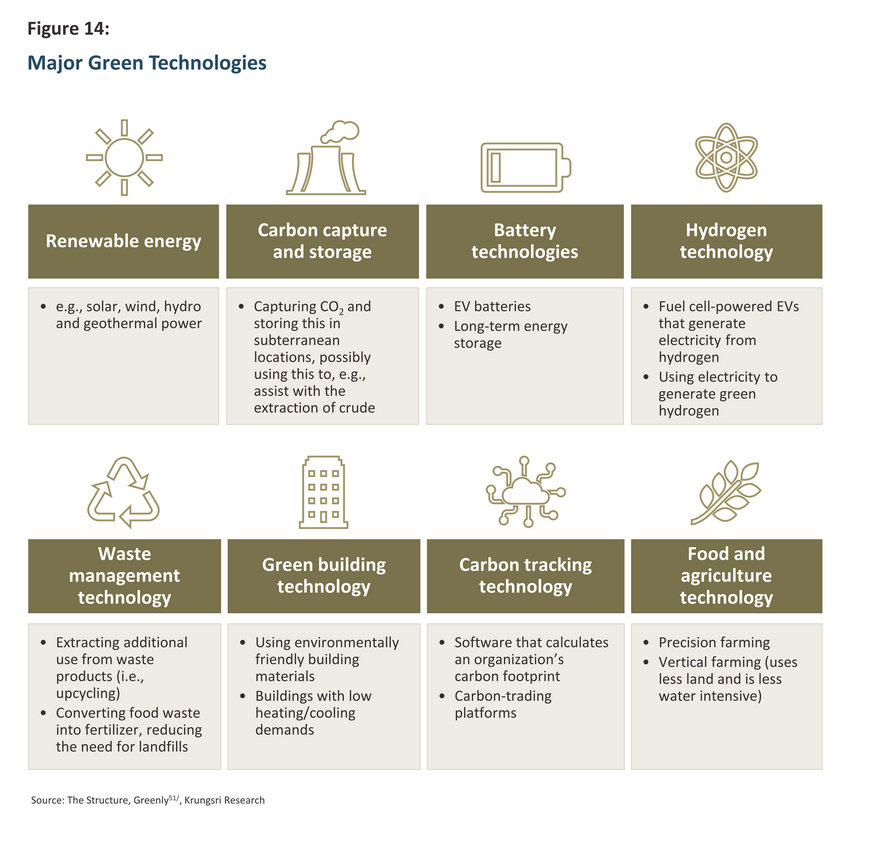

Thailand’s strong focus on cutting carbon emissions through action involving the energy sector carries with it a significant reliance on technology, and although low-carbon or ‘green’ technologies are showing increased potential to assist in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, greater research and development is needed before these will achieve widespread adoption. Moreover, the costs associated with many of these innovations (e.g., CCS and hydrogen-based power) remain significant, although with regard to the former, PTT Exploration and Production began researching the feasibility of using CCS in Thailand in 2021, and the company estimates that it will be possible to begin commercial CCS operations in the Arthit gas field in 202650/.

Stakeholder responsibilities for driving the transition to a low carbon future

While it is certainly true that the private sector will have a central role to play in determining the success or otherwise of the transition to the low-carbon economy, many other stakeholders will also play their part in supporting this process and in ensuring that the transformation of the economy is as smooth and painless as possible. It is interesting to note that in 2022, the United Nations Global Compact–Accenture CEO Study sought the opinions of more than 2,600 executives in 128 countries52/, and the survey revealed that 52% of CEOs saw the government as having the greatest influence over issues relating to sustainability. Moreover, 21% of CEOs surveyed believed that the banking sector also had an important role to play in this area, with the proportion up from just 6% in 2021. This survey therefore underlines the importance of stakeholders such as the public sector and the financial industry in helping to bring about these changes.

Among these, the government will have a central influence in setting the direction of change, in facilitating this change, and in ensuring that industry follows its lead. In this regard, one of the Thai government’s most important strategies has been the 30@30 policy, which aims to ensure that by 2030, 30% of autos coming off Thai production lines are zero emission vehicles (ZEVs). To help bring this about and to encourage increased domestic production and use of EVs, the government has made changes to the tax system and provided other assistance to industry. Because EV production is linked with many other parts of the economy, it is also hoped that an increase in the former will help to accelerate the green transformation in other parts of the economy. With regard to industry overall, the Board of Investment (BOI) rolled out its ‘Smart and Sustainable Industry’ policy at the start of 2023. This has the goal of encouraging the private sector to increase investment in industrial sustainability53/, for example through increased energy efficiency, greater use of alternative energy, reduced industrial impacts on the environment, and more rapid adoption of international sustainability standards54/. In the first quarter of 2023, the policy attracted 60 applications with a combined value of THB 3.33 billion. This reflects the widespread acceptance of these measures, and providing funding by the government now represents a valuable opportunity for increasing the sustainability of the Thai manufacturing sector55/.

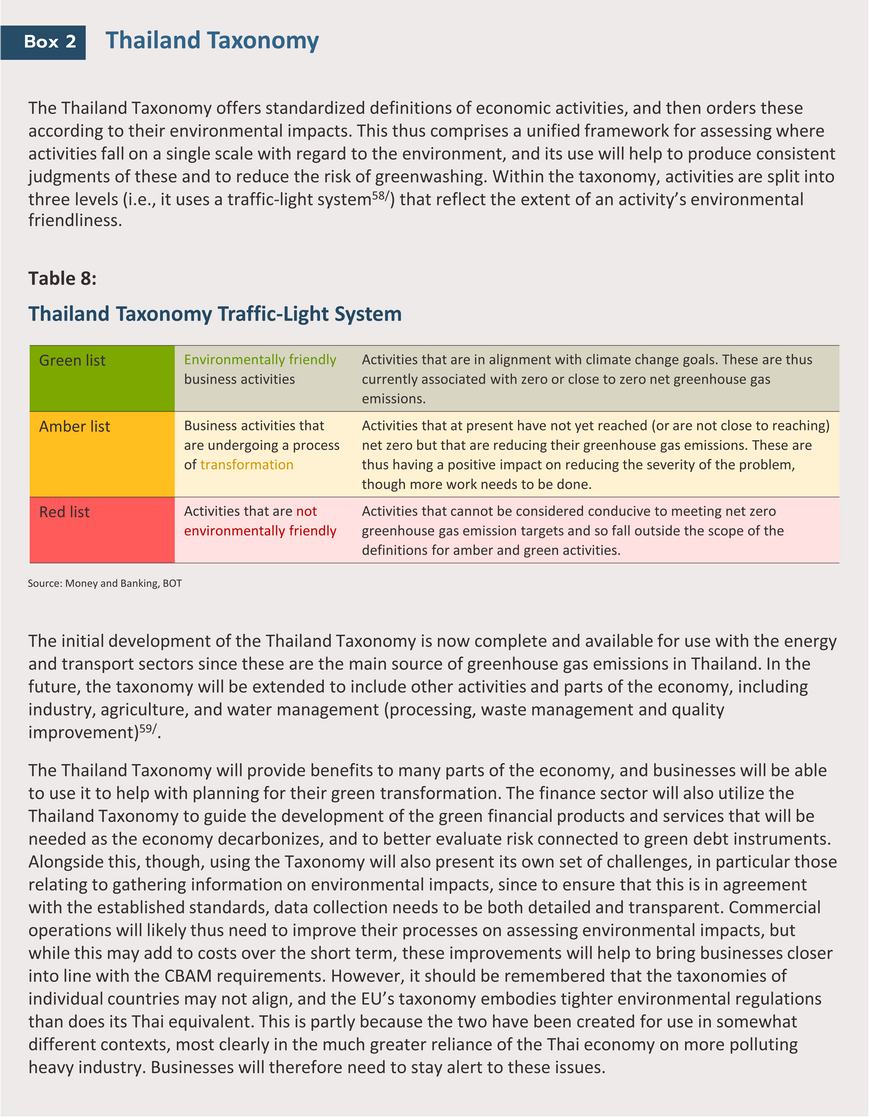

Because the transition to the green economy will carry with it a heavy price tag, a crucial role will be played by sustainable finance, since this will help to allocate capital efficiently. In Thailand, the issuance of sustainability bonds has undergone rapid growth, and as of the first quarter of 2023, these had a value of THB 550 billion, up around five-fold from their 2020 value of THB 110 billion. The majority of these are for financing related to projects that aim to cut greenhouse gas emissions56/. However, the development of the market for green finance involves both opportunities and threats. With regard to the former, this development will help to boost demand for green finance products, though with regard to the latter, it can be difficult to distinguish between worthwhile projects and those that represent less good value. To help address these problems, the Thailand Taxonomy has been created. This has the goal of establishing standards for classifying economic activities that are connected with the environment and for assessing their sustainability and environmental impacts.

Given, as described above, the problems arising from the implementation of the CBAM, the roles played by stakeholders in transitioning to the green economy, and the interconnections between these and how this will play out in determining how successful the country will be in meeting the challenges posed by the enforcement of the CBAM, it is clear that stakeholders will need to work hard to coordinate their efforts. However, if they are successful in this, this will then reduce the severity of the impacts associated with the new EU policies, and may even help to turn a crisis into an opportunity.

Krungsri Research view: Challenges confront opportunities on the path to the green transformation

The EU’s announcement of the introduction of the CBAM is further evidence of the rising international will to seriously confront climate change and to begin the transition to a low-carbon society. Although Thailand has set a target of reaching net zero emissions that is 15 years behind that of the EU, the country cannot avoid the need to adjust to this changing reality and to follow the lead set by countries at the forefront of the movement to manage problems with carbon emissions. As stated above, initially, the CBAM will come into effect for a transition period lasting somewhat longer than 2 years, but following this, the regulations will then be fully enforced. The impacts on Thai industry that can be expected over these two periods are described below.

- In the transition period (October 2023-December 2025), although it will not be necessary for manufacturers and exporters to purchase CBAM certificates, they will still face rising costs due to the need to report the greenhouse gas emissions connected to the manufacture of their exports. This will most seriously affect producers of iron, steel and aluminium, since these are the most important of the CBAM goods exported to the EU. Unfortunately, at present, Thai manufacturers, and especially MSMEs, are not well prepared to meet these challenges and to effectively measure and report their carbon emissions, and this lack of preparedness is reflected in the only low levels of participation in carbon labeling schemes. At the same time, Thailand’s ability to measure, report and verify emissions (MRV) is also underdeveloped and additional work is needed to bring this into line with the CBAM requirements and to prepare for future expansion in demand. The latter might include developing appropriate online platforms, increasing the knowledge and awareness of exporters, training assessors to verify carbon emissions, and cutting the costs of MRV systems since this may be a factor affecting businesses, most obviously MSMEs.

- Once the EU-CBAM is fully enforced (i.e., from 2026 onwards), exporters and other businesses connected to the export process should already be familiar with the measuring, reporting and verification processes. At this point, the major challenge facing Thai players will instead be meeting the additional costs arising from the need to purchase CBAM certificates to balance any additional carbon emissions connected to imports to the EU beyond that which is permitted. These challenges can be split into two main groups.

- The embedded emissions of Thai exports remain high since at present, reductions in overall greenhouse gas emissions remain a very long way off the goal of reaching carbon neutrality. In addition, unlike the EU, the Thai economy is still weighted towards industries and industrial processes that are energy and emissions intensive.

- The impacts of the CBAM will be amplified by: (i) any future expansion in the scope of the regulations beyond the six industries initially targeted; and (ii) the EU-CBAM triggering a domino effect by which other countries are encouraged to introduce similar measures, possibly led by nations on the opposite side of the Atlantic, namely the US and Canada.

Although in the eyes of the EU, these new measures may play the role of the hero in the drama of reaching net zero, given the likely impacts of the CBAM on their domestic industry and the wider economy, other countries could be forgiven for wondering if instead they would do better to regard the policy as the villain of the piece. The resolution of this question will, though, depend on the context in which individual countries find themselves, and for Thailand, the CBAM may in fact play a role in opening up new opportunities.

- Opportunities in the private sector: The introduction of the CBAM will help to build awareness of the importance of environmental issues across the private sector, and this will then help to accelerate the transition by Thai businesses to a low carbon future and therefore of meeting the country’s net zero goals. Meeting the requirements of the CBAM will also likely widen the use of carbon pricing mechanisms in originating countries, including for example carbon credit markets, which are used by businesses as a tool for cutting the costs associated with decarbonizing. These may in fact help to kill two birds with one stone: firstly by generating income from the sale of carbon credits, and secondly by providing confirmation in export markets that emissions reduction targets have been met. Moreover, the growth of the green economy will help to expand opportunities for new businesses, such as those connected with measuring and verifying carbon emissions and offering sustainability consulting services. This will also open up new investment possibilities connected to the development of green technology.

- Opportunities for the public sector: The enforcement of the CBAM will push policymakers to speed up their efforts to build a regulatory environment that will mirror international standards and encourage a fall in greenhouse gas emissions. This will include developing and extending carbon credit markets, the Thailand Taxonomy, and systems for measuring and verifying carbon emissions, while legislators will also be encouraged to pass a climate change law. As these measures come into effect, Thailand will move ever-closer towards the long-term goal of transitioning to a green economy.

- Opportunities for the finance sector: The financial sector will have a crucial role to play in softening the impacts of green policies such as the CBAM, on industries that are competing to cut greenhouse gas emissions and to win the race to carbon neutrality and the transition to a green economy. As part of this and to cover the necessary spending on technology, businesses will need access to sufficient capital reserves, and so thanks to its role as a financial intermediary, the finance sector, and especially banks, will occupy a central place in helping countries meet their net zero commitments. In this greener future, companies that will see major opportunities for growth but that will also therefore require additional capital will include those specializing in green technology, e.g., renewable energy, carbon capture and storage, battery technology, hydrogen power, green building, and the platforms needed to help with the measurement, calculation and trade in carbon.

In conclusion, although a superficial assessment of the CBAM might conclude that this will only generate problems and difficulties for manufacturers and exporters, a deeper look at these issues shows clearly that the introduction of these measures signals the start of a more serious attempt to push forward with the move to a green economy. This is no easy task, and so it is perhaps inevitable that this will bring with it both challenges and opportunities, but with effort and intelligence, the business and finance sectors will be able to maximize the latter and minimize the former.

References

Alexandra Dumitru, Barbara Kölbl, Maartje Wijffelaars. (2021). “The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism explained”. Retrieved from

https://www.rabobank.com/knowledge/d011297275-the-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-explained

Beaufils, T., Ward, H., Jakob, M. et al. (2023). “Assessing different European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism implementations and their impact on trade partners”. Commun Earth Environ 4, 131. Retrieved from

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00788-4

Chris Kardish, Mattia Mäder, Mary Hellmich, and Maia Hall. (2021). “Which countries are most exposed to the EU’s proposed carbon tariffs?”. Retrieved from

https://resourcetrade.earth/publications/which-countries-are-most-exposed-to-the-eus-proposed-carbon-tariffs

Cosbey, Aaron and Mehling, Michael and Marcu, Andrei. (2021). “Border Carbon Adjustments in the EU: Sectoral Deep Dive”. Retrieved from SSRN:

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3817779 or

http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3817779

He Xiaobei, Zhai Fan, Ma Jun. (2022). “The Global Impact of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: A Quantitative Assessment”. Retrieved from

https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2022/03/TF-WP-001-FIN.pdf

Iron and Steel Institute of Thailand. (2014). “Full report on the status of the non-ferrous metals and aluminium industry, carried out under the project for the development of an in-depth data analysis center for the metals industry, 2014”. Retrieved from

https://iiu.isit.or.th/en/reports/In-Depth%20Research%20Report/download.aspx?Content=1142

Judy Chao. (2023). “Carbon tariff: U.S. rules of the game”. Retrieved from

Patcha Thamrong-ajariyakun. (2022) “Singapore: Towards a green and sustainable future” Retrieved from

https://www.itd.or.th/itd-data-center/singapore-green-sdgs/

Presidential Climate Commission. (2023). “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms and Implications for South Africa”. Retrieved from

https://pccommissionflow.imgix.net/uploads/images/PCC-Working-Paper-CBAM.pdf.

The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. (2023). “REGULATION (EU) 2023/956 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 10 May 2023 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism”. Retrieved from

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R0956

1/ https://www.setsustainability.com/libraries/1035/item/european-green-deal

2/ https://www.energy.gov/lpo/inflation-reduction-act-2022 and https://www.bot.or.th/th/research-and-publications-listing.html

3/ https://thaibizchina.com/article/dual-carbon/

4/ Patcha Thamrong-ajariyakun (2022) “Singapore: Towards a green and sustainable future” Retrieved from https://www.itd.or.th/itd-data-center/singapore-green-sdgs/

5/ https://tha.mofa.go.kr/th-th/brd/m_3129/view.do?seq=744835#:~:text=ในขณะที่เกาหลีใต้นั้น,นิเวศ%20การจัดหาพลังงานคาร์บอน

6/ https://api.dtn.go.th/files/v3/63bbd0c9ef4140d9817e6047/download

7/ https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/eu-carbon-border-tax

8/ Presidential Climate Commission. (2023). “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms and Implications for South Africa”. Retrieved from https://pccommissionflow.imgix.net/uploads/images/PCC-Working-Paper-CBAM.pdf.

9/ The Thai government is currently negotiating with the EU over accrediting a number of independent auditors for the CBAM embedded emissions accounting process. These include the Centre of Excellence on enVironmental Strategy for GREEN business (VGREEN) at Kasetsart University, the Research Unit for Energy Economic & Ecological Management at Chiang Mai University, and the Center of Excellence for Eco-Energy (CEEE) at Thammasat University, as well as independent auditors from the public and private sector and from other educational institutions. For more details, please see: http://thaicarbonlabel.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=ZG1WeWFXWnBaWEk9&action=Y0hKdlpIVmpkSE09

10/ https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en

11/ https://www.eex.com/en/market-data/environmentals/eu-ets-auctions

12/ REGULATION (EU) 2023/956 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 10 May 2023 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R0956

13/ https://www.dtn.go.th/th/content/page/index/id/11332

14/ Judy Chao. (2023). “Carbon tariff: U.S. rules of the game”. Retrieved from

15/ He Xiaobei, Zhai Fan, Ma Jun. (2022). “The Global Impact of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: A Quantitative Assessment”. Retrieved from https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2022/03/TF-WP-001-FIN.pdf

16/ Alexandra Dumitru, Barbara Kölbl, Maartje Wijffelaars. (2021). “The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism explained”. Retrieved from https://www.rabobank.com/knowledge/d011297275-the-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-explained

17/ Beaufils, T., Ward, H., Jakob, M. et al. (2023). “Assessing different European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism implementations and their impact on trade partners”. Commun Earth Environ 4, 131. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00788-4

18/ Chris Kardish, Mattia Mäder, Mary Hellmich, and Maia Hall. (2021). “Which countries are most exposed to the EU’s proposed carbon tariffs?”. Retrieved from https://resourcetrade.earth/publications/which-countries-are-most-exposed-to-the-eus-proposed-carbon-tariffs

19/ https://allafrica.com/stories/202211140007.html

20/ https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/addressing-carbon-leakage-risk-to-support-decarbonisation

21/ https://ccsi.columbia.edu/content/event-highlights-carbon-border-adjustments-eu-us-and-beyond and https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/consultations/2021/border-carbon-adjustments.html

22/ Carbon neutrality refers to the point when the quantity of greenhouse gas emissions is equal to the quantity of greenhouse gas being removed from the atmosphere. This may be achieved through three means: (i) emissions reductions, for example by reducing consumption of fossil fuels; (ii) the removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, for example by reforesting or by making use of carbon capture and storage facilities; and (iii) offsets, for example through carbon credits. This differs from net zero emissions in that this occurs when there is a balance between the quantity of greenhouse gases released into and reclaimed from the atmosphere. This thus excludes the use of offsets or carbon credits in the accounting process. Net zero also extends to include other greenhouse gases in addition to carbon dioxide (e.g., methane, nitrous oxide), and so reaching net zero is more challenging than reaching carbon neutrality (Thanisa Thawitchasri (2022). “Carbon neutrality and net zero emissions: What’s the difference and why is this important?” Retrieved from https://www.pier.or.th/blog/2022/0301/)

23/ Calculated from exports (tonnes) x emission factor (tCO2e/tonne) for each product, and then as a weighted average for the industry as a whole.

24/ Calculated from emissions (tCO2e) x CBAM price (weekly average of ETS auction = EUR 91.56/tCO2e as of April 23, source: https://www.eex.com/en/market-data/environmentals/eu-ets-auctions) x exchange rate calculated at an average of THB 37: EUR 1.

25/ If the index has a high value, this indicates that this segment is heavily integrated with downstream production, and so any shock (e.g., from higher costs) is likely to have major impacts on downstream industries.

26/ If the index has a high value, this indicates that this segment is heavily integrated with upstream production, and so any shock (e.g., from a decline in exports) is likely to have major impacts on upstream industries.

27/ Cosbey, Aaron and Mehling, Michael and Marcu, Andrei. (2021). “Border Carbon Adjustments in the EU: Sectoral Deep Dive”. Retrieved from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3817779 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3817779

28/ https://bellona.org/news/fossil-fuels/2019-03-is-steel-ste

29/ https://www.toolmakers.co/green-steel-การผลิตเครื่องมือและ/

30/ https://news.isit.or.th:8080/isit/2023/04/10/ความต้องการ-green-steel-เพิ่มขึ้น/

31/ Full report on the status of the non-ferrous metals and aluminium industry, carried out under the project for the development of an in-depth data analysis center for the metals industry, 2014.

32/ https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/bumper-green-aluminium-output-is-good-news-carmakers-climate-2022-12-17/

33/ High-density polyethylene (HDPE) is not transparent, whereas low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is.

34/ https://www.bio-eco.co.th/bioplastics/ and https://packingdd.com/blogs/news/พลาสติกชีวภาพ-คืออะไร-ทำไมถึงมีความสำคัญต่อบรรจุภัณฑ์

35/ https://packaging.oie.go.th/new/admin_control_new/html-demo/file_technology/8405319726.pdf

36/ For more details, please see http://thaicarbonlabel.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=Y0hKdlpIVmpkSE5mY0hKdlkyVnpjdz09

37/ https://www.circularise.com/blogs/scope-1-2-3-emissions-explained

38/ “Embedded emissions mean direct emissions released during the production of goods and indirect emissions from the production of electricity that is consumed during the production processes” (REGULATION (EU) 2023/956 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL)

39/ Registering one product with the CFP costs THB 8,500, with this rising to THB 110,000 for those registering 101 or more products. (http://thaicarbonlabel.tgo.or.th/admin/uploadfiles/files/ts_7e7d2db8ca.pdf)

40/ For further details, please see https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/tver-step/tver-fee.html

41/ Thailand’s voluntary pilot project for trading in carbon permits is run by the TGO. For more details see http://carbonmarket.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=Y29uY2VwdF92ZXRz

42/ Carbon credits or reductions in greenhouse gas emissions below the business-as-usual case that can be traded in the market need to be certified, for example by the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), the Gold Standard (GS), the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), or the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Program (T-VER).

43/ As of 2019, net emissions of greenhouse gases were equal to 280.7 MtCO2e (https://climate.onep.go.th/th/topic/database/ghg-inventory/#1629282850097-8b14e636-4ba4)

44/ This can be done in two ways: (i) directly made agreements between buyers and sellers to trade that do not occur on the open market (i.e., over-the-counter, or OTC sales), which is the main way of carrying out T-VER trades; and (ii) through a trading platform, which first became available in the 2023 financial year.

45/ http://tcnn.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=YUc5dFpRPT0

46/ https://re100th.org/#

47/ As part of the drive to meet the RE100 goals, companies have been given the opportunity to apply for a ‘Renewable Energy Certificate’ (REC), which recognizes the right of an organization to produce and use renewable energy. This is issued only by approved organizations. Like carbon credits, RECs can be traded, though the goal of RECs is to reduce the release of scope 2 greenhouse gases, whereas carbon credits aim to cut emissions of scope 1, 2 and 3 gases (the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand and the Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization. See https://egc.egat.co.th/rec-คืออะไร/)

48/ Thailand submitted its targets and long-term strategies under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

49/ https://www.greenpeace.org/thailand/story/17760/climate-emergency-thai-climate-change-law/

50/ https://www.pttep.com/th/Sustainability/Carbon-Capture-And-Storage.aspx

51/ https://greenly.earth/en-us/blog/ecology-news/everything-you-need-to-know-about-green-technology-in-2022

52/ Jointly organized by UN Global Compact and Accenture in 2022. For more details, please see http://ebook.globalcompact-th.com/books/vsbf/#p=7

53/ Incentives available to investors include: (i) waivers on import duties on plant and machinery that will increase production efficiency; and (ii) waiving taxes for 3 years to a value of 50% of the investment, excluding purchases of land and working capital. However, the minimum investment is set at THB 1 million, though for SMEs this is reduced to THB 500,000. (https://www.boi.go.th/th/smart_sustainable)

54/ Examples of international sustainability standards include accreditation by Good Agriculture Practices (GAP), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Scheme (PEFCs), and the ISO 22000 food safety standards.

55/ https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/environment/1069788

56/ https://thaipublica.org/2023/06/pier-research-climate-adaptation-financing/

57/ https://www.sec.or.th/TH/Template3/Articles/2566/210166.pdf

58/ https://moneyandbanking.co.th/2023/18096/

59/ https://www2.deloitte.com/th/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/thailand-taxonomy-th.html