Executive summary

The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which formally came into effect on July 25, 2024, requires that large companies carry out comprehensive supply chain auditing to ensure that any risk of infringements to human rights and environmental protections is accounted for. These regulations will potentially have significant consequences for Thai companies investing in or exporting to the EU, or that are otherwise entangled in EU supply chains, and as such, these may now have to contend with: (i) rising costs connected to the need to carry out supply chain due diligence and to transition their operations to a more sustainable footing; and (ii) shrinking market share and declining competitiveness in the event that they are unable to meet these new obligations. For Thai players, these changes will be most consequential for businesses in rubber, food processing, automotive, electronics, textiles, jewelry, and retail. Thus, in response to the emergence of these more challenging conditions, companies will need to adopt the ‘4Cs’. These are: collecting data on their supply chains; checking risks to labor and the environment; changing the business to become more sustainable; and capturing opportunities to exploit new openings to invest in the EU and in other markets that will adopt similar measures in the future.

Supply chain legislation

What is supply chain legislation?

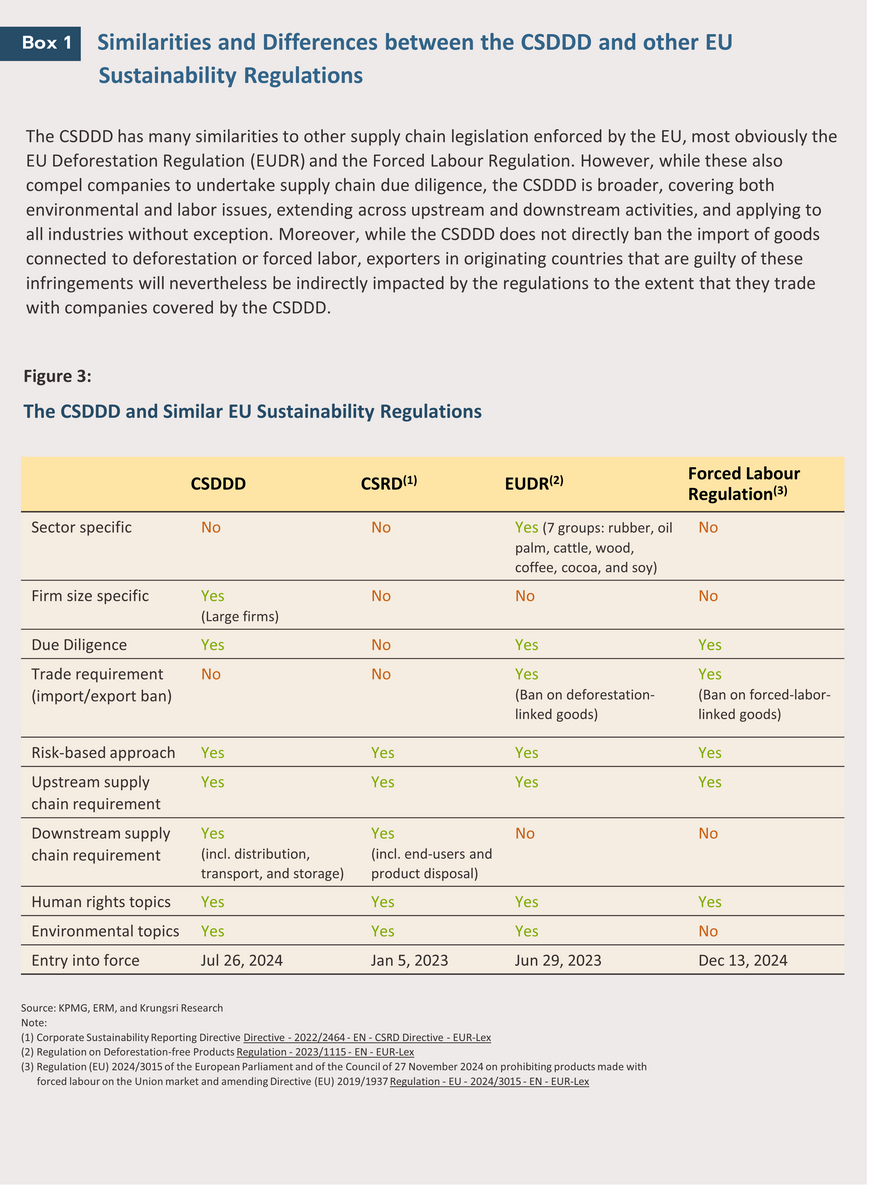

There is a major risk that if corporations ignore issues of sustainability, their supply chains will involve exploitative practices and human rights abuses, and so their activities may have potentially significant negative impacts on the environment, local communities and the broader society. In response to rising awareness of the importance of these issues, countries around the world, including Germany, France, Norway, the UK, Canada, and the US, are moving to compel companies to integrate issues of sustainability into their supply chain management systems, and laws of this kind are often referred to as ‘supply chain acts’. These typically require that companies carry out comprehensive supply chain due diligence to ensure that activities connected to these do not entail the infringement of human rights, employment law, or environmental protections.

On July 25, 2024, the European Union—recognized as a global leader in sustainability regulations—officially enacted its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which is widely seen as one of the most comprehensive and stringent such laws yet enacted. This requires that large companies active in the EU carry out supply chain due diligence and report on their environmental and social responsibilities in areas such as emissions controls, deforestation, and labor protections across the length of their supply chains. This paper thus aims to provide a clear assessment of the requirements mandated by the CSDDD and to assess the likely impacts of these on Thailand, given the country’s investment and trade ties with the EU.

What requirements are laid out in the CSDDD?

The CSDDD focuses on two primary areas of concern.

1) Companies are required to carry out supply chain due diligence focusing in particular on issues connected to the environment and human rights. This should be done at least annually and the results of this process should be made publicly available on the company’s website. These requirements are based on international standards and conventions

1/, and cover the following areas.

-

Human rights: This includes child labor, forced labor, freedom of association and collective bargaining, and discrimination in employment.

-

The environment: This includes issues connected to biodiversity, the preservation of endangered wildlife and plant species, the disposal of hazardous waste, the protection of cultural and national heritage, the prevention of pollution from ships, and the control of maritime pollution.

2) Companies are required to act to reduce the impacts arising from climate change, in particular by: (i) drafting a transition plan that details how the company will move to a more sustainable footing, including its carbon emissions reduction targets, its proposed means of meeting these goals, the funds allocated to this, and the individuals responsible for overseeing these activities; and (ii) implementing this plan as fully as possible. Companies are further required to engage in a process of revising and improving this plan and reporting on the progress that they have made towards this, and to do this at least once per year.

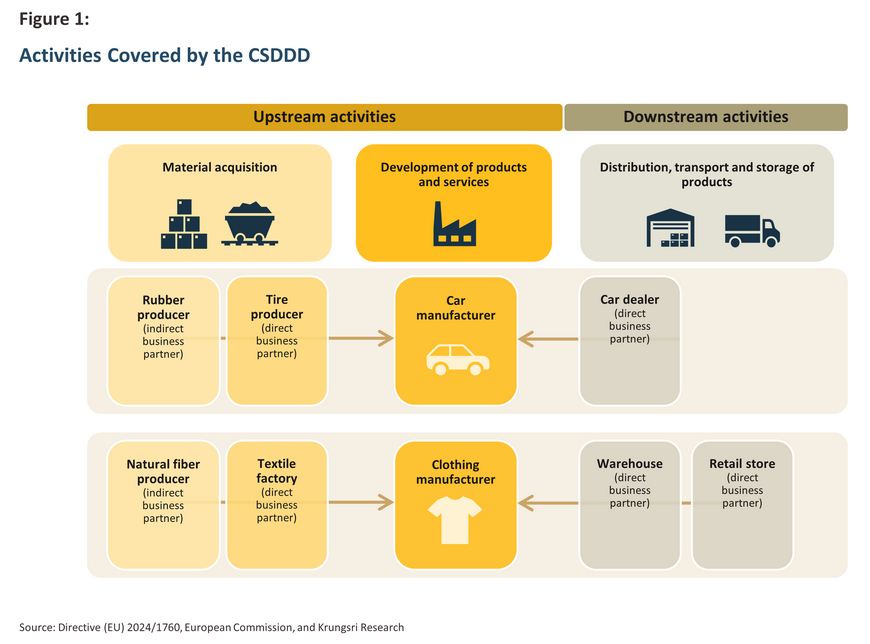

A core requirement of the CSDDD is that companies carry out due diligence across the length and breadth of corporate supply chains. This covers upstream activities, such as sourcing raw materials or other inputs, manufacturing and the development of products and services, and downstream businesses, including for example, transportation, warehousing and distribution. Moreover, these requirements also encompass the activities of external providers with contractual relationships with the company (i.e., direct business partners) as well as those with looser, less intimate relationships (i.e., indirect business partners). For example, the upstream activities of an apparel manufacturer could include their relations with textile manufacturers, while downstream activities might be centered on retailers that distribute their goods to end consumers. In the case of an auto assembler, direct business partners might include tire manufacturers, while indirect partners could include the rubber growers supplying rubber to these companies (Figure 1).

What happens if a CSDDD violation is identified? Under the CSDDD, if activities within a company’s supply chain are found to have had adverse environmental or social impacts that cannot be remediated or mitigated, the company will be required to suspend or terminate any business relationships that it has with that supplier. If the company fails to comply with the requirements specified in the CSDDD, it will face a maximum fine of at least 5% of its global net profits. The company may also be banned from tendering for public-sector contracts and may face the prospect of civil cases being brought against it for infringement of human rights or the imposition of negative environmental impacts on third parties.

Which companies are affected by the CSDDD?

The CSDDD covers the activities of large companies that fall into one of the following three categories.

-

EU-based companies that report a global net annual turnover2/ of at least EUR 450 million and that employ at least 1,000 individuals (including parent companies).

-

Non-EU companies that report a net annual turnover from activities carried out within the EU of at least EUR 450 million (including parent companies).

-

Franchised companies that have agreed a franchise agreement with or that collect royalties from companies active in the EU that have a global net annual turnover of at least EUR 80 million, and that earn at least EUR 22.5 million from royalties.

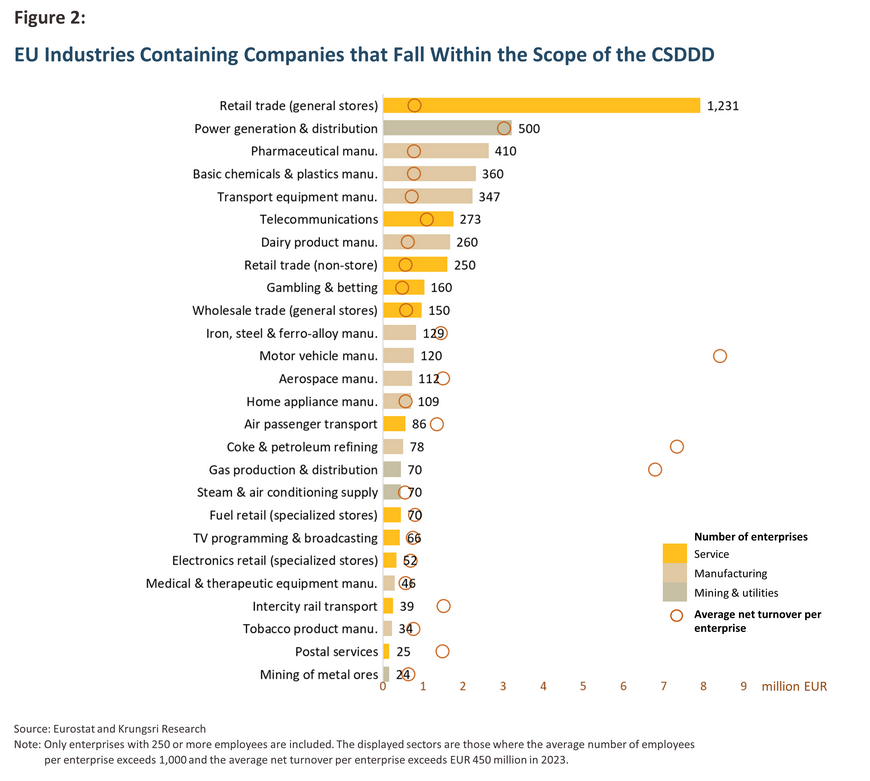

EU-based companies that have a sufficiently large turnover and payrolls to be affected by these regulations (group 1) are found across the economy in the service sector (e.g., in retail, telecommunications, and transportation), manufacturing (e.g., pharmaceuticals, chemicals, dairy products, iron and steel, motor vehicles, and electrical appliances), and utilities (e.g., power generation and distribution, gas production and distribution, and steam supply) (Figure 2). However, while major companies in these areas can be expected to be most impacted by the new requirements, companies that are outside these areas will not escape the fallout from these changes. This will include in particular SMEs in Europe and elsewhere that are embedded in the supply chains of major corporations and that will thus be exposed to indirect impacts.

When will the CSDDD be enforced?

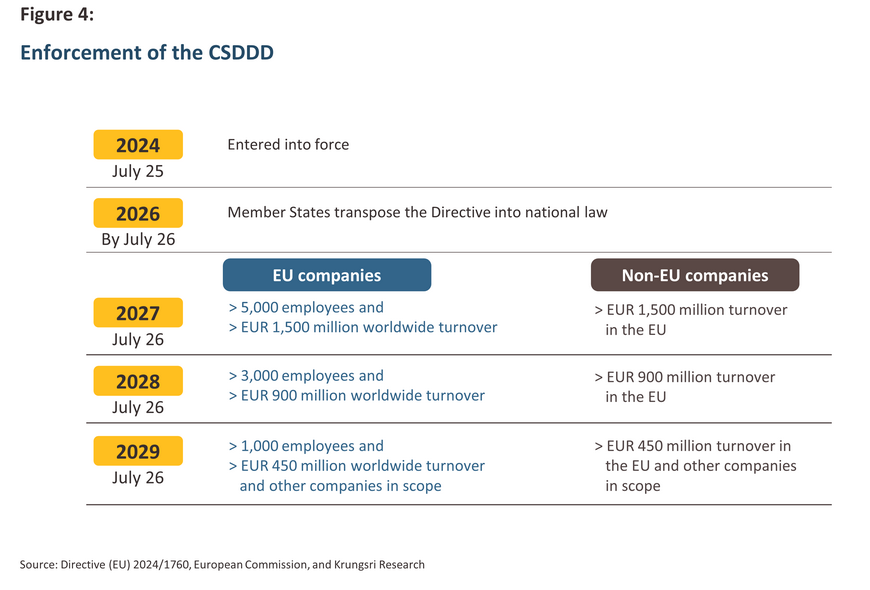

The CSDDD regulations entered into force on July 25, 2024 but a transitionary period that will allow companies to adjust to these changes is currently in effect. Actual enforcement will begin on July 26, 2027. Initially, this will apply only to the largest corporations but the scope of the regulations will be extended, and from July 26, 2029, these will cover all activities undertaken by companies targeted by the legislation (Figure 4)

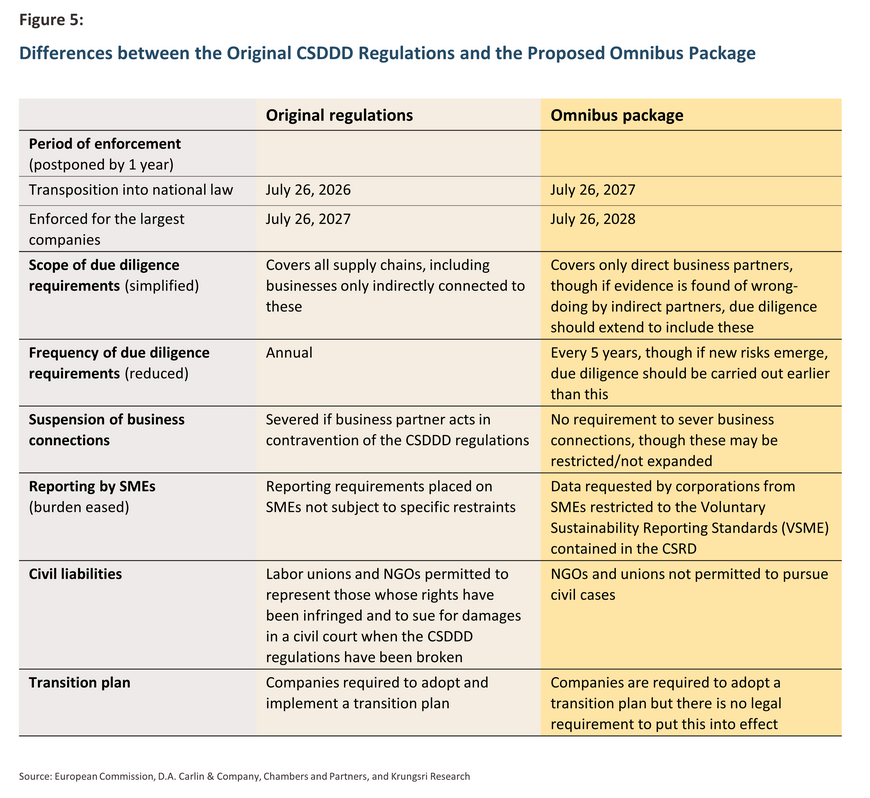

However, the proposed enforcement schedule may be delayed following the February 26, 2025, introduction by the European Commission of a proposed ‘omnibus package’ that aims to simplify the EU’s current sustainability legislation3/. This includes postponing enforcement of the CSDDD regulations by 1 year (i.e., from 2027 to 2028) to allow businesses additional time to prepare. In addition, by simplifying the requirements for supply chain due diligence and restricting this to only direct business partners, reducing the frequency of these checks, and loosening the data-collection requirements placed on SMEs, the package aims to streamline a number of other regulations (Figure 5). These changes are still under consideration by the European Parliament and the European Council, and so it waits to be seen how the regulatory environment will evolve.

Impacts of the EU supply chain legislation

EU supply chain legislation applies to businesses operating in all parts of the economy and so this has the potential to generate widespread impacts. Thai businesses that will be exposed to risk arising from the enforcement of the CSDDD will include: (i) large corporations investing directly in the EU; (ii) companies that have business relationships that tie them to the EU, most obviously exporters; and (iii) companies that are linked to the supply chains of other businesses that fall within the scope of (i) or (ii). Players in any of these three groups will potentially face a number of impacts.

Negative impacts

-

Rising operating costs: This will have two primary drivers. (i) Compliance costs will come from the additional expenses entailed in collecting data on supply chain activities, carrying out due diligence and sustainability planning, and preparing the documentation required to support these activities. (ii) Transition costs will include the overheads resulting from investing in overhauling business and value chain operations and bringing these into line with international sustainability standards and best practices.

-

Shrinking market share and declining competitiveness: If companies are unable to align their operations with the new requirements, they may face greater obstacles investing in or exporting to the EU. Moreover, these problems will not be faced only by major corporations but will potentially expand to include indirect impacts on micro, small, and medium sized enterprises (MSMEs) that are suppliers to larger companies since these will need to collect and disclose data on their own sustainability efforts. Thai companies may therefore be at risk of being excluded from global supply chains if domestic or EU-based corporations decide to switch to sourcing goods from suppliers that have lower social or environmental impacts.

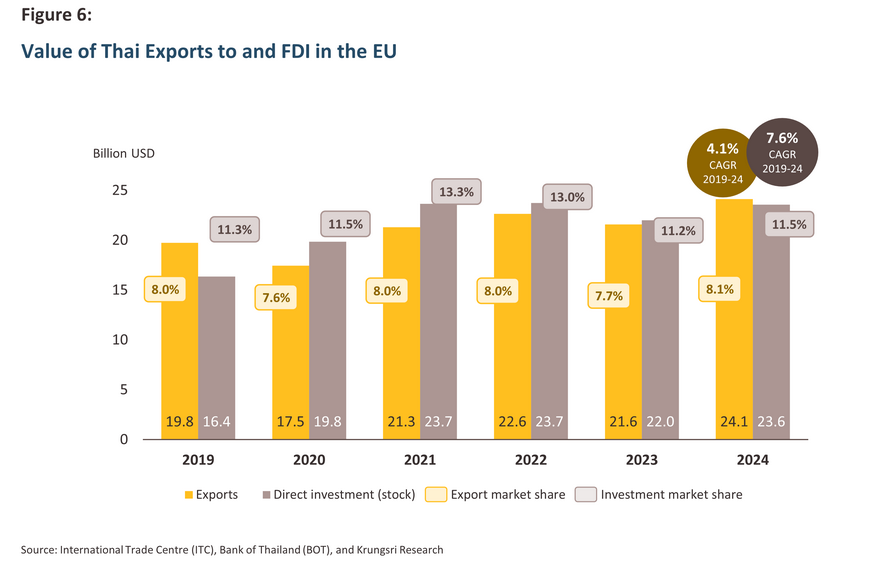

Clearly, it is extremely important that the impacts of the CSDDD are carefully assessed, which necessarily involves an examination of the extent of Thai trade and investment in Europe (Figure 6). The EU is Thailand’s fourth most important export market, coming behind only the ASEAN region, the US, and China, and so in 2024, exports to the bloc from Thailand totaled USD 24.1 billion, or 8.1% of all Thai exports (close to the value of those going to Japan). At the same time, the EU comes third after the ASEAN region and Hong Kong in the ranking of Thai investment targets, and in 2024, Thai direct investment stock in the EU totaled USD 23.6 billion (11.5% of all FDI made by Thai companies)4/. Given this, economic activities exposed to the risk of negative impacts from the CSDDD are valued at around USD 50 billion, or THB 1.6 trillion, annually.

On the other hand, legislation that encourages companies to make their supply chains more sustainable will not only have positive impacts on Thailand but will also help to open up new business opportunities.

Positive impacts

-

Improved opportunities for trade and investment: Enterprises that are able to meet the requirements of the CSDDD and that transition their operations to a more sustainable footing across their supply chains will be rewarded with market shares that remain stable or expand. This will be particularly important because for Thai exporters, the EU market has recently grown substantially, increasing in size by some 4.1% and 7.6% annually over 2019 to 2024 with regard to respectively exports and investments. Moreover, other markets have also introduced or will introduce similar types of supply chain legislation, and responding successfully in one market will carry over into others. More generally, with the environment and human rights now much more prominent, this will also help to boost the competitiveness of Thai exporters on the global stage, and indeed, issues around sustainability are now an important factor to consider when negotiating international trade agreements.

-

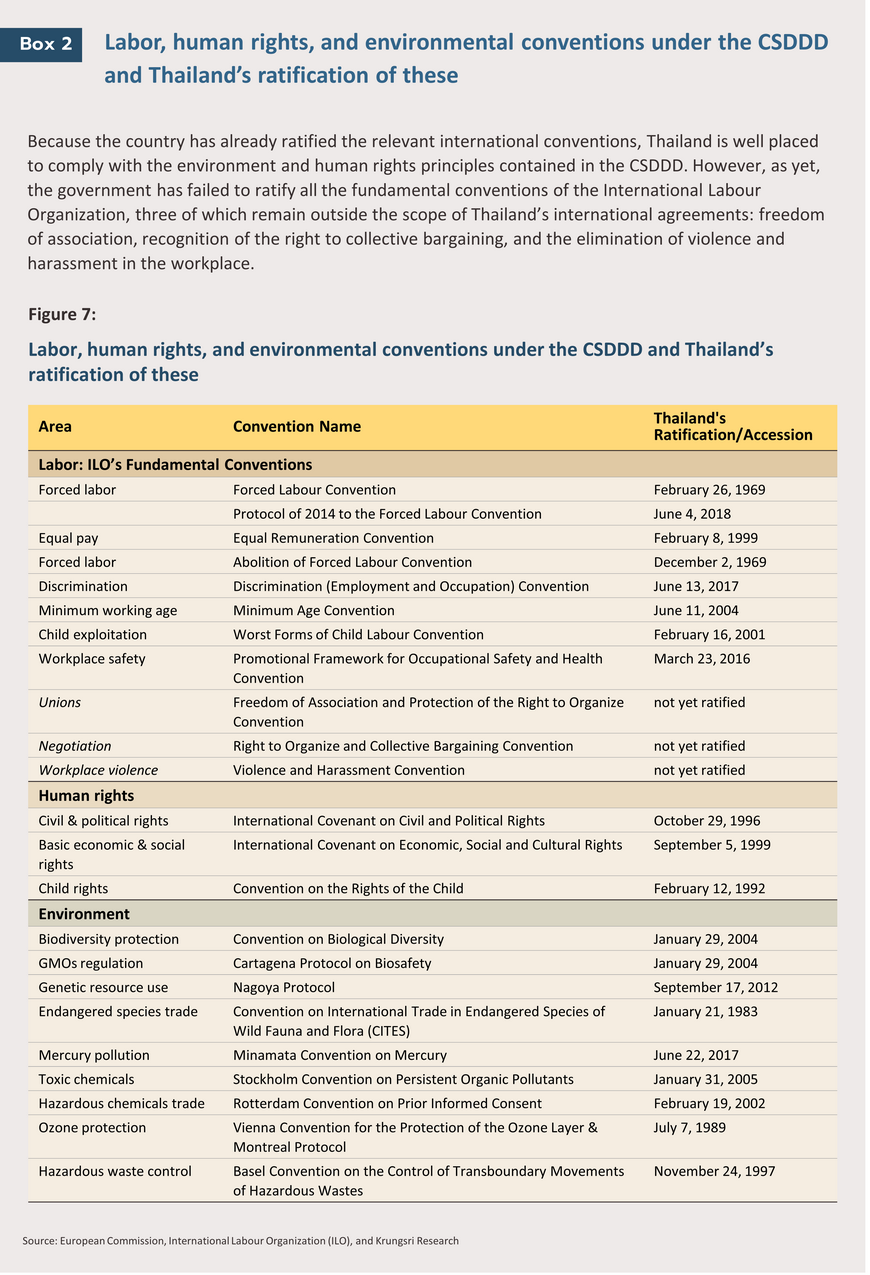

Improved domestic standards for the protection of human rights and the environment: Legislation targeting sustainability will help to compel businesses to take seriously their relationships with their workforce, the environment, and society, while importantly, Thai policymakers are also expected to accelerate the enforcement of similar laws. The latter may include intensifying efforts to match Europe in moving towards climate change targets and reforming labor laws to better align these with international standards, especially in areas such as freedom of association and collective bargaining, key parts of the International Labour Organization (ILO) declaration that Thailand has yet to ratify (Figure 7). Ultimately, efforts in these areas will help to pay dividends in the form of long-term sustainable growth, higher living standards for workers, and improved environmental stewardship.

Key industries affected by the CSDDD

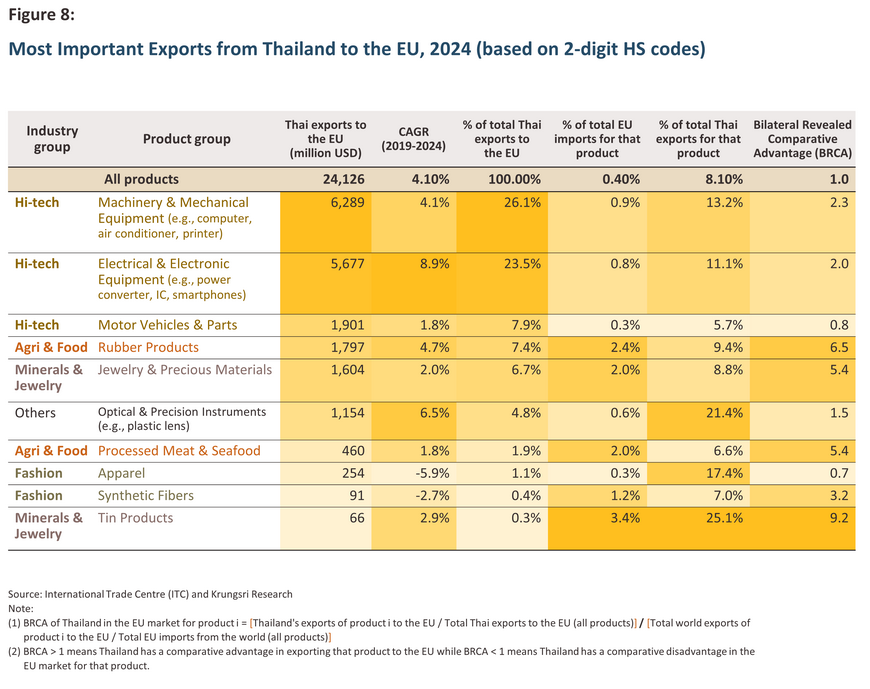

Analysis of the impacts of the CSDDD by industry has been undertaken with reference to the total value of exports by that industry to the EU, the trade dependence between Thailand and the EU, and the level of investment in each type of business. The results of this analysis are as follows.

-

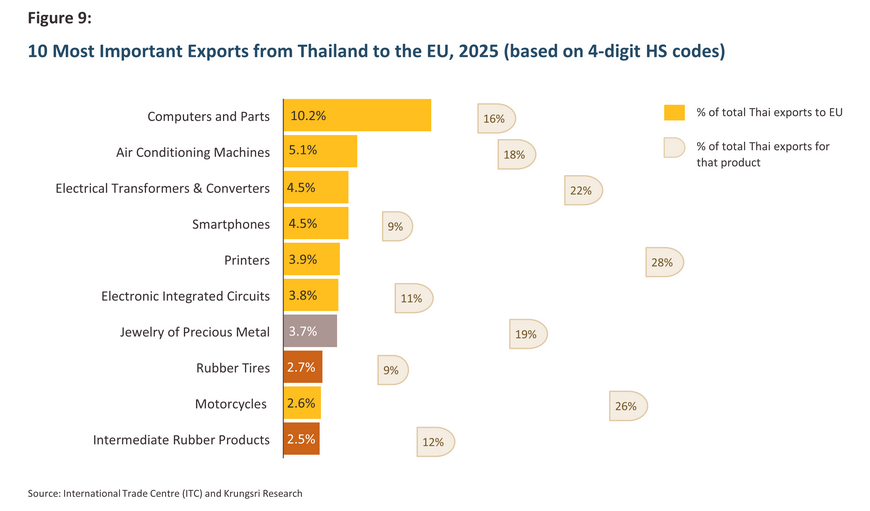

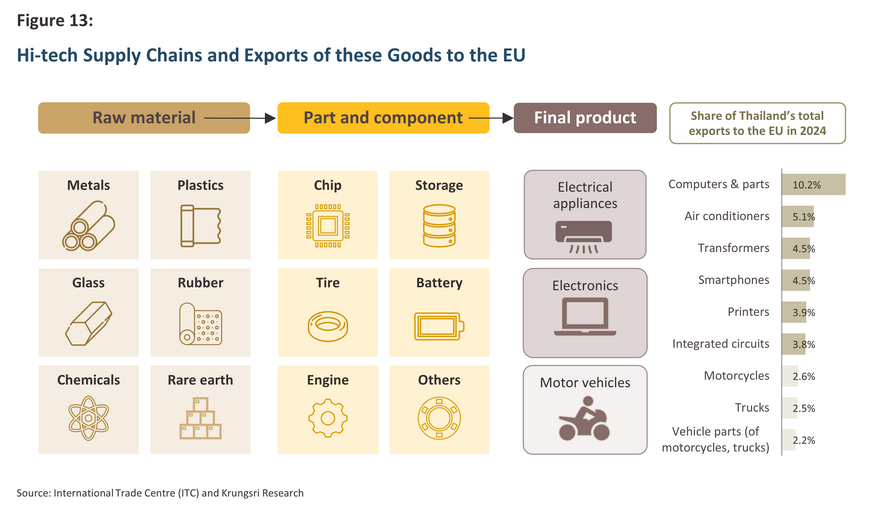

Export value: The most important exports to the EU are of electrical appliances and electronics, which account for around a half of all exports to the region (Figure 8). Among these, the most significant product categories were computers and computer parts (10.2% of all exports), air conditioners, electrical converters, smartphones, and printers, which comprised the 5 biggest export categories in 2024 (Figure 9). Electrical appliances and electronics were followed in importance by autos and auto parts, especially motorcycles, rubber products, most notably tires and processed rubber, and gems and jewelry.

-

Thailand–EU trade interdependence: The areas where Thai exports are most highly dependent on sales into Europe are electronics and electrical appliances, apparel, lenses, gems and jewelry, and tin. From the perspective of European importers, the bloc is most reliant on Thailand as a source of rubber, jewelry, processed food, and tin. Thailand is thus at a comparative advantage with regard to exports of these products.

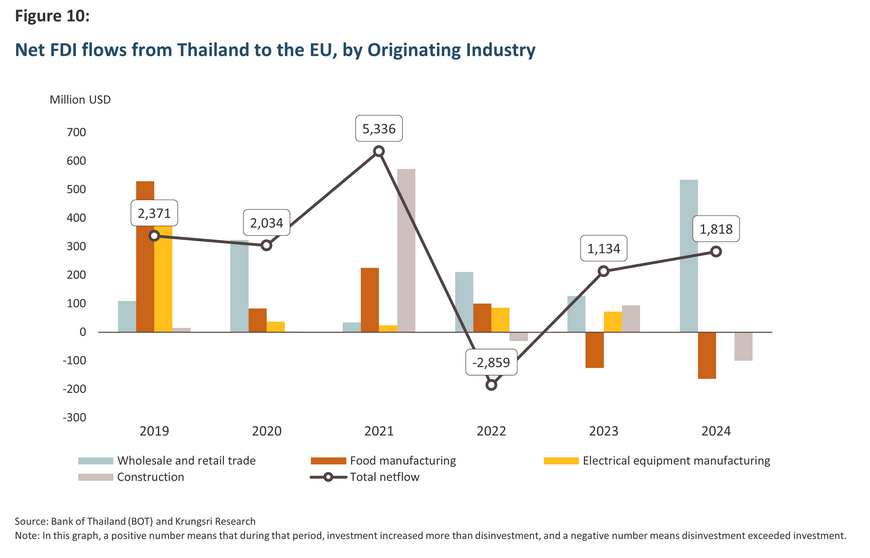

- Investments in the EU: Over 2019-2024, the largest accumulated net direct investment flows from Thai investors in the EU went into in order retail/wholesale businesses, food processing, the manufacture of electrical equipment, and construction. Most notably, net FDI flows from Thailand’s retail and wholesale businesses to the EU grew through all of these 6 years (Figure 11).

Given the picture painted by the data on trade and investment in the EU, it can be seen that the agriculture and food processing, hi-tech (i.e., automotive and electronics), textiles and apparel, gems and jewelry, and retail and wholesale industries will be most seriously affected by the CSDDD. Further details on these industries are given below.

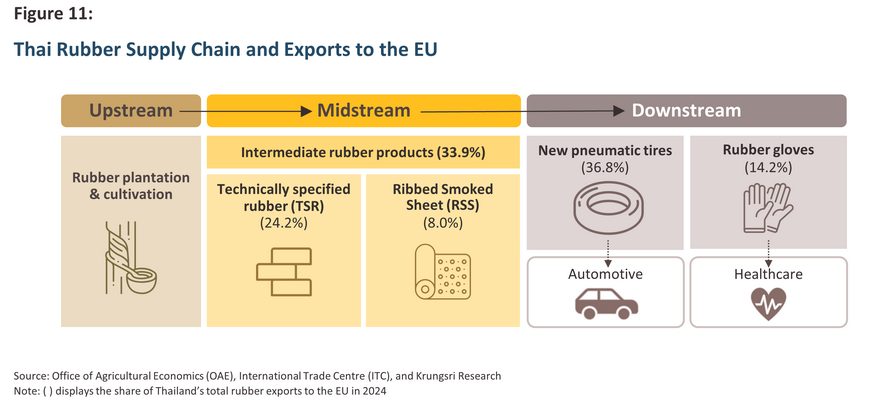

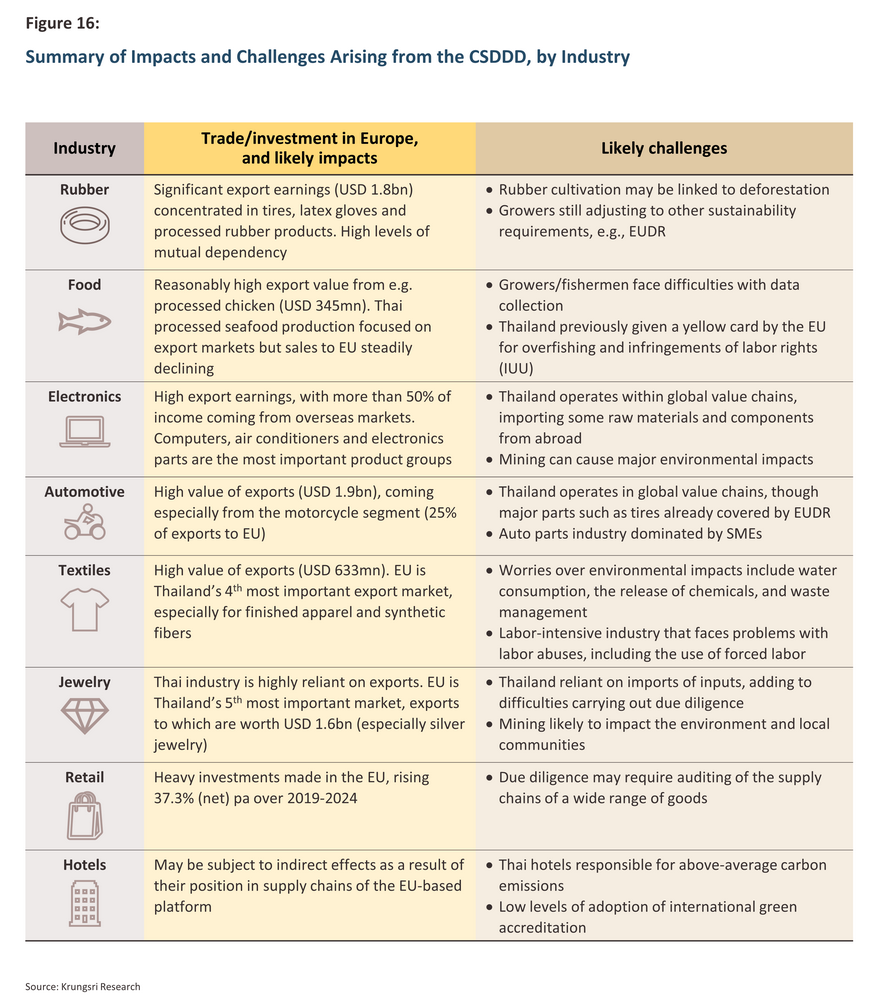

Agriculture and food

Rubber: Exports of rubber and rubber products generated receipts worth USD 1.8 billion in 2024, or 7.5% of all exports to the EU. 36.8% of sales into the EU were of downstream goods, most importantly tires, especially for buses and trucks, and latex gloves. Midstream processed rubber products were also important, including technically specified rubber (TSR) and rubber smoked sheet (RSS). Across all rubber categories, sales into the European Union account for an average of 9.4% of all exports, although for some products (e.g., for latex gloves and RSS), this rises as high as 17%-18%. Thai companies in midstream and downstream positions within the rubber industry will thus need to be proactive in preparing for these changes if they wish to secure their access to a market with such high potential.

Overall, players in the Thai rubber industry face a range of challenges when attempting to carry out due diligence and to manage rubber supply chains in a sustainable fashion. Problems are particularly intense when attempting to verify the provenance of goods and to ensure that the production of these did not involve deforestation, which is then problematic with regard to the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). At present, systems for tracking the provenance of rubber products do not fully cover the country, and many producers have not yet reached the standards set by or are not yet certified under internationally recognized schemes such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). As such, Thai companies will likely come under increasingly intense competitive pressures, especially given the fact that rubber is used in high-value industries such as automotive and healthcare. It is therefore imperative that even if they do not export directly to the EU, players begin to collect data on, for example, auditing of supply chains, and then to use this as proof of their compliance when dealing with partners and customers.

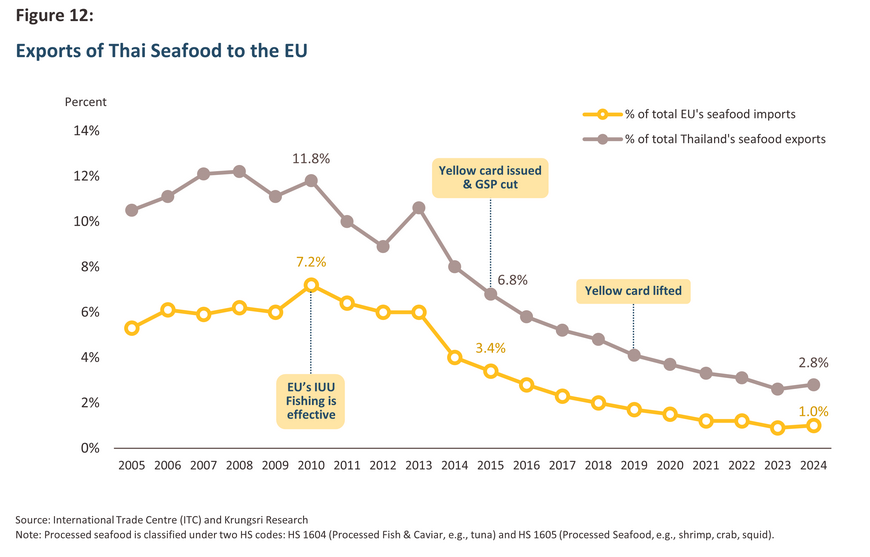

Food products: The Thai seafood industry is primarily focused on export markets, but unfortunately, this also faces challenges transitioning to a sustainable business model. These troubles begin at the most upstream point of the supply chain, namely with the fisheries industry, where overfishing is impacting inshore ecosystems and exploitation of labor on Thai trawlers remains a serious problem. For export markets sensitive to these issues, this poses a significant block on growth, though these problems are most clearly at the fore when attempting to access EU markets. Over the period 2005-2010, more than 10% of exports of Thai seafood products were sold into the bloc, while from the EU’s point of view, imports from Thailand accounted for some 5%-7% of all seafood sourced externally. However, reliance on Thai products began to wane after 2010 and the introduction of the EU’s regulations on illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing), which required a boycott of imports of seafood linked to overfishing and the abuse of labor, and so in 20155/, the EU issued Thailand with a yellow card as a result of the country’s failure to address problems in these areas. This has then helped to perpetuate the drop off in Thai-EU trade in seafood products, even while globally, overall Thai exports and EU imports of these same goods have not declined (Figure 12).

Although the EU’s yellow card against Thailand was rescinded in 2019, seafood exports have failed to recover, and as of 2024, sales into the EU represented just 2.8% of all exports of Thai seafood. IUU fishing thus remains a problem and if players are not able to demonstrate that seafood supply chains operate in accordance with EU regulations, the ability of exporters to compete effectively on world markets will continue to be undercut. Moreover, these impacts also have the potential to multiply because from 2018 onwards, the US, Thailand’s most important export market for seafood products, has required that importers report data on activities across their entire supply chain.

In addition to seafood, the EU is also a major export target for sellers of processed chicken, and so in 2024, sales into Europe generated income worth USD 344.9 million, or 11.7% of all Thai processed chicken exports. Players in the industry will now need to audit supply chains back to the originating but geographically diverse chicken farms, and thus smaller entrepreneurs will need to shoulder the burden of costs generated by additional data collection. Major Thai corporations have also expanded into Europe, and so CP has invested in a Belgium manufacturer of ready-to-eat meals and in Poland operates businesses connected to seafood processing, chicken farming, food processing, and the manufacture of animal feed6/. Companies in this position will now need to carry out more extensive supply chain due diligence.

Hi-tech industries

In this context, hi-tech industries include Thai automotive assemblers together with manufacturers of electronics, electrical appliances and machinery, for which exports to the EU were worth USD 13.9 billion in 2024, or 60% of all earnings from exports to the EU in that year7/. A common feature of these industries is the fact that they operate within global value chains and that they depend on inputs (e.g., of minerals, metals, plastics, rubber, glass, etc.) to produce intermediate goods, some of which still require further imports to manufacture. These are then assembled into the high-value finished products that are so important for the development of the global economy (Figure 13).

However, these industries can have significant environmental impacts as a result of the need for metals and rare earth elements in the production of chips, electronic goods and autos. The mining needed to extract these from the earth is often linked to deforestation, pollution, and the release of radioactivity, while at the end of their lifecycle, these goods may also be the source of a considerable quantity of e-waste. Beyond this, these industries may be linked to unfair labor practices at all stages of the production process, from mining through to factory-based assembly of intermediate and finished goods.

In detail, the Thai electronics and electrical appliance industries are expected to be significantly impacted by the new regulations because for players in these supply chains, the EU is their third most important export market, coming after just the US and the ASEAN region. The most important product category is computers and computer parts, which alone accounts for 10.2% of exports to the EU, and within this broad category, the most valuable segments are laptops, data storage devices, and electronics parts such as static converters and integrated circuits, for which sales to the EU represent respectively 22.4% and 10.7% of the total. Within the electrical appliances category, air conditioning units and printers are the most important items, with the EU absorbing 17.8% and 28.0% of all exports. It can be seen that the majority of exports are of finished goods, but unfortunately, the length of their supply chains makes carrying out due diligence more onerous. Moreover, Thai production and assembly is reliant on imports of raw materials and other inputs, adding to the difficulties involved in carrying out due diligence.

The auto and auto parts industry is a major driver of the Thai economy and a significant source of export earnings, and so its fate is of national significance. The most valuable exports to the EU are, in order of importance, motorcycles (the EU buys approximately a quarter of all Thai exports of these), trucks, and parts for both of these (the EU absorbs 16.4% of all Thai exports of motorcycle parts). However, a great many companies contribute to these supply chains and so carrying out due diligence is complex, while production of some inputs (e.g., tires) may be linked to negative environmental impacts and so these are covered by separate requirements for supply chain auditing. Moreover, thanks to their sizeable turnover and large workforces, EU auto assemblers will be among the first companies to be affected by the enforcement of the CSDDD regulations (Figure 2), and so their Thai counterparts, including a great many SME manufacturers of auto parts, will likewise be among those exposed to the first wave of impacts.

Nevertheless, players in hi-tech industries will be able to lessen the force of some of these headwinds, for example by switching to more environmentally friendly inputs (e.g., green steel, and bioplastics), extending the lifespan of electrical appliances, recycling major components (e.g., batteries), using renewables to power their industries, and managing e-waste more efficiently.

Textiles and apparel

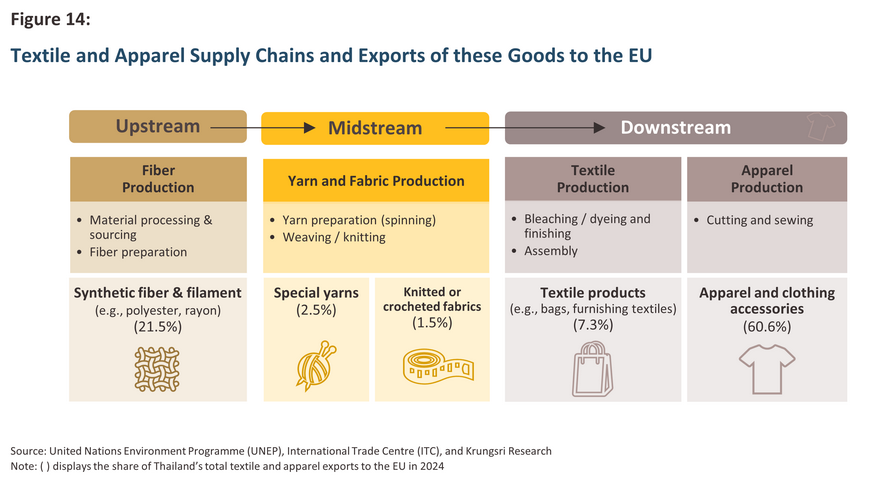

The textiles and apparel supply chain begins with the production of fiber, which may be either made from petrochemical products, and hence is considered artificial, or from natural products such as cotton, silk and wool. Intermediate production is based on the conversion of fibers into yarn and the weaving of fabrics, either directly from fiber or from yarn. Finally, these midstream products will be cut, sewn or otherwise assembled into finished textile and apparel products for wholesale or retail distribution (Figure 14).

The EU is Thailand’s fourth most important market for exports of textiles and apparel, coming after the ASEAN region, the US and Japan in order of importance. In 2024, sales into the bloc generated income worth USD 633 million, or 10.1% of all earnings from exports of these. 60.6% of this was from just the export of finished clothing, though Thai manufacturers also export fibers, both artificial (e.g., polyester, rayon and aramid) and natural (e.g., wool and silk). The former is of greater importance than the latter.

However, the industry faces challenges meeting environmental and human rights targets. In particular, the industry is linked to negative environmental impacts relating to excessive water use and pollution resulting from bleaching and dying yarns and textiles8/. Moreover, mass production, which is due especially to the rise of fast fashion, has added to problems with waste disposal, and with water and air pollution. The industry also remains highly labor intensive and continues to face scrutiny over its poor labor relations. Thus, the Ethical Fashion Report 20249/ reveals that in some areas, textile and fashion workers can work up to 75 hours a week, and almost 90% of companies fail to pay their workers a living wage. For companies embedded in the supply chains of European manufacturers such as Zara (Spanish), Puma or Adidas (both German), or of other manufacturers that distribute globally, the enforcement of the CSDDD will expose companies to the risk of significant impacts from the need for due diligence and sustainability auditing.

Gems and jewelry

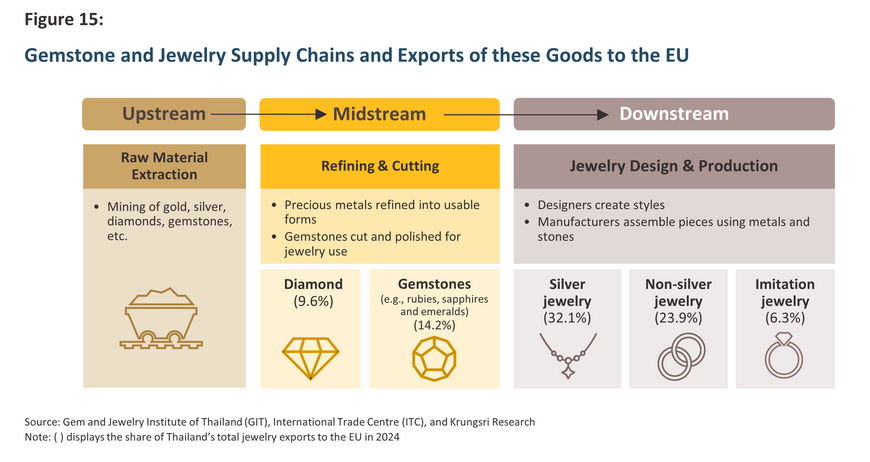

Gems and jewelry have long been an important component of the Thai export sector, and over 80% of production is now targeted at overseas markets. Upstream parts of the supply chain are centered on the mining required to supply the industry with the metals and gemstones that it needs, although domestic production of these is insufficient to meet demand and so Thailand is dependent on imports of inputs such as gold, silver, diamonds and other gemstones. These typically come from suppliers in Hong Kong, Switzerland, China and India. These inputs will then be processed by midstream players such as gemstone cutters and polishers, operations that are themselves dependent on both advanced technology and access to skilled staff. From there, downstream processes include the design and production of jewelry, its transport and distribution, and the provision of insurance for this.

The EU is Thailand’s 5th most important market for exports of gems and jewelry, the USD 1.6 billion in sales (8.7% of the total) placing the bloc behind the ASEAN region, Switzerland, Hong Kong, and the US in terms of income. Jewelry is the most important product category within the broader industry, though silver items are particularly significant and sales of these represent around a third of the export values of gems and jewelry to the EU. The importance of the bloc to the industry is underscored by the fact that Europe accounts for 26.9% of all global sales of Thai-made silver jewelry, which is followed in importance by gold and platinum items. Thailand is also a major source of exports of intermediate goods such as diamonds and other gemstones, including rubies, sapphires, and emeralds, and so some 10% of all exports of these are to the EU.

As a result, exporters operating within this industry will face increased scrutiny of what may be long and complex supply chains10/. This is particularly the case for upstream processes involving mining because this is often carried out in remote areas, and whether at home or abroad, extractive industries may have significant negative impacts on both local communities and the surrounding environment. Beyond this, players are also coming under pressure to improve their production processes and to meet international standards for sustainability, such as those set by the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), an independent body that sets standards and offers certification based on the four areas of business ethics, human and labor rights, environmental stewardship, and supply chain management11/.

In addition to gems and jewelry, other manufacturing industries that may feel the effects of the new regulations will include the production of the non-ferrous metals tin and nickel, and although total exports of these to the EU are not especially notable, the continent is nevertheless a major source of earnings for players in these industries. Thus, a quarter of the earnings generated by tin exporters come from the EU market, though mining of this has major environmental impacts. Thailand is also an important manufacturer of eyeglass lenses, coming after only China in the global rankings of suppliers to world markets, and because many of the world’s leading manufacturers of glasses are based in Europe12/, the EU is an important market for Thai exporters. This is most pronounced for manufacturers of plastic lenses since Thai players sell 41.6% of their output to the bloc. Thai lens manufacturers should thus consider improving the sustainability of their products, perhaps by using a greater proportion of environmentally friendly plastics in their goods.

Services

Retail and wholesale: Thai corporations have been investing in European retail and wholesale operations for some time, and over 2019-2024, net investment flows to these businesses surged by an average of 37.3% per year. In 2024, the net value of FDI flows from Thailand increased by USD 534.9 million, the highest of any category of business. Central Group is now the most prominent Thai investor in the retail segment13/, having steadily expanded its investments in department stores in Germany, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Italy. The retail industry is thus another area where Thai players will be exposed to the risk of negative impacts arising from the in-depth supply chain due diligence, especially since this will need to stretch back to the production of the upstream agricultural and manufactured goods used as inputs into the consumer goods sitting on department store shelves. The variety of the latter will add to worries over the range of possible environmental impacts or human rights infringements that might be connected to their production, thus making the auditing of their provenance particularly challenging.

Tourism and hotels: Although Thai hotel operators have not made any large-scale investments in the EU, they may nevertheless be affected by the introduction of the CSDDD regulations. This is thanks to the fact that many Thai hotels are listed on Booking.com, a platform that is registered in the Netherlands, and to ensure that its supply chains have as small an environmental footprint as possible, this may require that hotels around the world likewise make their operations as sustainable as possible. For Thai hotels, this could be particularly problematic because their carbon emissions are substantially higher than the global average. In particular, the 2024 Cornell Hotel Sustainability Benchmarking Index shows that for Thai hotels, emissions average 0.061 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) per occupied room against a global average of 0.026 tCO2e. European platforms may also insist that hotels using their services pass relevant international sustainability accreditation (e.g., EarthCheck, Green Globe and Travelife), though at present, among Thai hoteliers, only major hotel groups operating in the primary tourist areas have done so. Moreover, going forward, hotels will likely feel more pressure originating directly from consumers as the latter become increasingly concerned about environmental issues, as seen in the survey carried out by Booking.com in 2024 that showed that three-quarters of travelers would be looking for more sustainable travel options in the coming year14/.

Krungsri Research view: How should Thailand respond to deepening regulation of supply chains and sustainability?

The introduction of the EU’s supply chain due diligence requirements is adding to the difficulties faced by businesses around the world because in addition to targeting companies based in Europe, this will also impact their suppliers, whether or not these are in Europe. A survey by the EQS Group and the University of Applied Sciences, Ansbach15/ thus revealed that 55% of EU companies that responded to the survey reported being concerned that their suppliers would not meet the EU’s sustainability requirements due to the assumed high or very high risk that these were guilty of environmental and/or human rights violations. As a result, companies that fall within the scope of the CSDDD will tend to put increased pressure on companies and business partners within their supply chains and to push these to remedy these issues, and this will naturally include Thai companies exporting to or investing in the EU. Krungsri Research thus believes that Thai companies that are exposed to these risks should prepare for these changes and the consequent increase in competitive pressures and business headwinds by adopting the ‘4Cs’ of collect, check, change and capture. These are described below.

-

Collect: Companies will need to collect data on the environmental and social impacts of both their own operations and those of companies operating within their supply chains. This will include information on areas such as land use, energy consumption, carbon footprints, waste management, working hours, working conditions, and the names of the company’s suppliers. It will then be possible to use this data to help analyze and evaluate the distribution of risk through the supply chain and to act appropriately on this. It will also become increasingly common for requests for this type of information to come from business partners outside the EU, and so given this, companies should begin as soon as possible to set up systems to collect and store data relating to their supply chains.

-

Check: Companies will need to check or assess the sustainability of operations across their supply chains. This will then allow players to identify and evaluate the extent of risk and any potential impacts on stakeholders, including farmers, employees, consumers, local communities, and the wider environment. However, exact risks will vary according to the business type and the nature of their activities. Thus, farming and mining, which typically provide the inputs needed for downstream industries, carry an elevated risk of social and environmental impacts, especially in their immediate vicinity. By contrast, labor-intensive sectors are much more likely to be linked to unfair labor practices. Businesses will therefore need to identify points in their supply chains where risk is most pronounced and then to mitigate and ultimately eliminate this.

-

Change: This stage of adaptation involves bringing business operations into line with international standards by transitioning these to a more sustainable footing. Regarding the preservation of labor and human rights, this will include registering workers as required by law, specifying fair working hours, wages and benefits, prohibiting child and forced labor, and ensuring that workplaces are free from discrimination. To improve compliance with environmental regulations, players could increase their use of environmentally friendly inputs (e.g., green steel and bioplastics) and renewable energy, choose to partner with companies that are heavily focused on their own sustainability, and apply for recognized sustainability certification. Beyond this, companies should demonstrate their commitment to net zero by drawing up a plan for their transition to the green economy and by setting their own sustainability targets.

-

Capture: Players will need to capture opportunities for trade and investment as these arise within the EU and in other markets. However, if Thai companies are successful in preparing their supply chains for the challenge of meeting more stringent sustainability requirements, this will put them in a much better position to maintain and then potentially to expand their market share in Europe. This will be especially so for industries where Thailand is at an advantage, for example in agriculture and food processing, certain hi-tech industries, and jewelry. Nevertheless, this should be balanced by an acknowledgment that the global economic and political system is undergoing a rapid structural shift and that as companies transition to a greater emphasis on their sustainability, they should also consider reducing their dependency on any particular market, including the EU. Instead, players may find it more beneficial to diversify across a wider range of trade partners, especially those located in the ASEAN region.

Looked at more broadly, the sustainability transition that is being carried out by the private sector will need to be supported by concrete government action on both environmental and labor policies. On the environmental front, this should include the adoption of a national climate change law to underpin the green transition within the business sector. On the labor side, it should involve recognition and incorporation of key provisions of the ILO conventions, which would help facilitate discussions on free trade agreements with partners that prioritize these issues (i.e., the EU16/). Moreover, where appropriate, government agencies should also put in place measures to support SMEs that operate within EU-linked supply chains and that are now feeling the consequences of this. Ultimately, a coordinated approach that synergizes the work of policymakers and businesses, and that is then bolstered by the work of sustainable finance, will help to optimally position Thailand to first weather and then benefit from the changes to the global trading environment that are now unfolding and that are bringing issues around sustainability to the fore

References

Baker McKenzie. (2024). “European Union: The new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive what does it mean for companies?” Retrieved from https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2024/01/corporate-sustainability-due-diligence-directive

Chambers and Partners. (2025). “EU Simplification Package - CSRD, CSDDD and CBAM under revision.” Retrieved from https://chambers.com/articles/eu-simplification-package-csrd-csddd-and-cbam-under-revision.

ERM. (2024). “Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).” Retrieved from https://www.erm.com/globalassets/insights/documents/erm-policy-alert-csddd-april-2024.pdf

European Commission. (2025). “Commission simplifies rules on sustainability and EU investments, delivering over €6 billion in administrative relief.” Retrieved from https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/commission-simplifies-rules-sustainability-and-eu-investments-delivering-over-eu6-billion_en

European Parliament, Council of the European Union. (2024). “Directive (EU) 2024/1760 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on corporate sustainability due diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and Regulation (EU) 2023/2859 (Text with EEA relevance).” Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1760/oj/eng

Gem and Jewelry Information Center. (2025). “Thailand’s Gem and Jewelry Export Situation from January to December 2024.” Retrieved from https://infocenter.git.or.th/storage/files/kXqG08Euv2FLwlumvHsFkerkkBHculEwk6COuXtW.pdf

KResearch. (2018). “How is Thai Fisheries Adapting? Under the Conditions of IUU Fishing.” Retrieved from https://www.kasikornbank.com/th/business/sme/KSMEKnowledge/article/KSMEAnalysis/Documents/Thai-Fisheries_IUU-Fishing.pdf

Warudom Paenduang and Wannisa Uthaisean. (2024). “What is CSDDD and Why Should the Rubber Industry Start Paying Attention to It?” Rubber Journal, Vol. 45, No. 4, July – September 2024.

TradeBeyond. “The List of Global Supply Chain Due Diligence Laws Keeps Growing.” Retrieved from https://tradebeyond.com/the-list-of-global-supply-chain-due-diligence-laws-keeps-growing/

1/ Such as the United Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines), and the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy

2/ Net turnover means the amounts derived from the sale of products and the provision of services after deducting sales rebates and value added tax and other taxes directly linked to turnover (Source: Directive 2013/34/EU, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32013L0034).

3/ The omnibus package covers a number of regulations including the CSDDD, CSRD, EU Taxonomy and the CBAM.

4/ Almost 70% of investments in the EU are made in the Netherlands, which is followed in importance by Germany (7.5%), France (3.5%), Belgium (1.8%), and others.

5/ In the same year (i.e., from January 1, 2015 onwards), the EU withdraw Thailand from its ‘Generalized System of Preferences’ (GSP) following the country’s recategorization as an upper middle-income economy.

6/ Exports of animal feed are approximately equal in value to those of processed chicken.

7/ The value of exports of goods covered by HS codes 84, 85 and 87.

8/ Source: Bangkokbiznews, https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/environment/1142007

9/ Ethical Fashion Report 2024, prepared by Baptist World Aid Australia, evaluates 120 fashion companies on environmental sustainability and labor practices throughout their supply chains. (Source: Baptist World Aid, Read The Ethical Fashion Report - Baptist World Aid)

10/ Source: GIT Information Center, https://www.thaitextile.org/th/insign/detail.2346.1.0.html

11/ Source: imode, https://www.imode.co.th/what-is-rjc-responsible-jewellery-council/

12/ Source: Longtunman, Thai Optical Group บริษัทไทย ผู้ผลิตเลนส์แว่นตาระดับโลก

13/ The Central Group has declared its intention to operate its supply chains in accordance with international best practices for the support of labor and human rights, the environment and anti-corruption efforts. Moreover, as part of efforts to better assess business impacts and risks, the company has joined the UN Global Compact and has adopted EU standards, including the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) (source: One Report CPN, One Report CPN, cpn-one-report-2024-th-v2)

14/ Read more about sustainable tourism and relevant standards at: Sustainable Tourism: A New Era of Travel Prioritizing Sustainability

15/ Source: Maya Derrick (Sustainability Magazine), EU Firms Rush to Meet New CSDDD Sustainability Standards | Sustainability Magazine

16/ The EU may use the Thai-EU FTA to negotiate Thailand’s ratification of core ILO principles (The Momentum, https://themomentum.co/report-european-parliament-fta-negotiate-thai-to-reform-its-laws/)