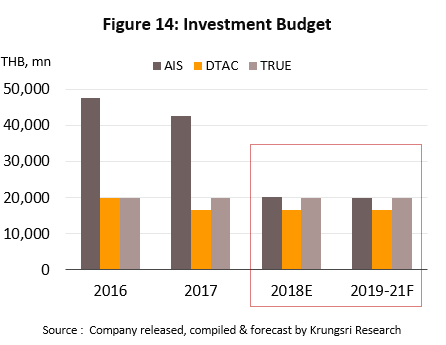

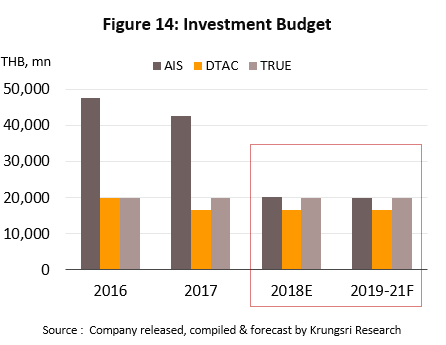

Krungsri Research believes that from 2019 to 2021, mobile phone operators will be able to maintain steady growth in turnover. In this period, income from service charges should strengthen by 4-5% per year on a combination of a general recovery in consumption and, as network coverage expands, growth in operators’ subscriber base. However, price competition remains fierce within the sector and business costs have risen as a result of the twin burdens of having to bid for access to government-controlled frequencies and continuing investments in network upgrades and extensions. As such, turnover and profitability are being put under pressure.

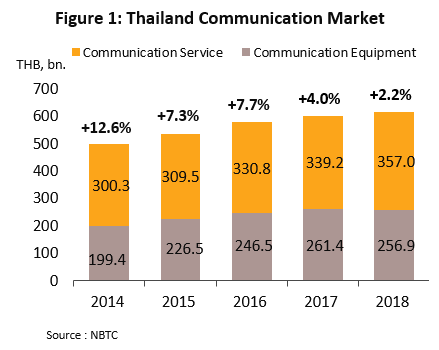

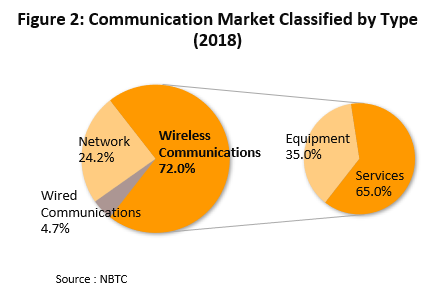

In 2018, the Thai communications sector[1] had a total value equivalent to some 3.9% of GDP with a large-scaled of turnover for the year coming to around THB 610 bn (growth of 2.2% on the 2018 figure), and this was split between income from the provision of communication services and that from communication equipment; the former had a value of THB 360 bn (58.2% of the communication market) and the latter THB 260 bn (41.8% of total communication market) (Figure 1). Growth in the communications sector comes mostly from the mobile phone (wireless) segment and in 2018, this had a share of 72.0% of the communications market. In this segment, it is divided into services (63.0% of the total) and equipment (the remaining 35.0%) (Figure 2). Expansion has been driven by the rapid pace of technological change in both network provision and the development of mobile phones and other related devices, though in addition, operators have also been very active in making investments to expand network coverage, and the outcome of this has been that in only a short period of time, wireless communications have improved dramatically in quality and coverage. Pushed on by consumer preferences for ease and convenience in all things at all times, mobile services have found a wide range of applications and uses, and this has thus sustained positive business conditions for operators.

Mobile phone operators can be split into two groups.

- The first group comprises those operators that have the right to carry signals on a certain frequency (i.e. mobile network operators, or MNOs) and which have the infrastructure or network to independently offer mobile telecommunications services. This group may be subdivided into:

- State enterprises, in this case TOT and CAT Telecoms[2].

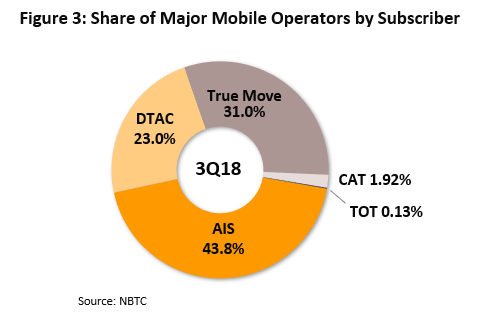

- Private enterprises, such as the AIS Group (Advanced Wireless Network, or AWN), the DTAC Group (Total Access Communication, DTAC and DTAC Trinet, or DTN), and the True Group (True Move H Universal Communication, or TUC).

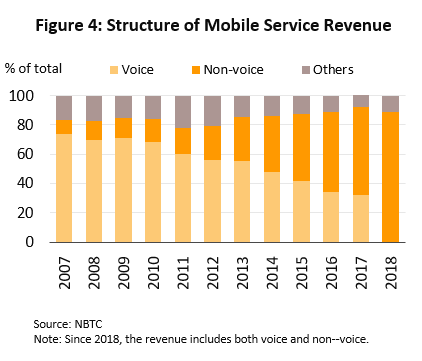

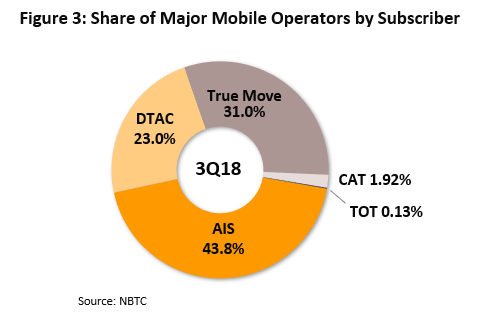

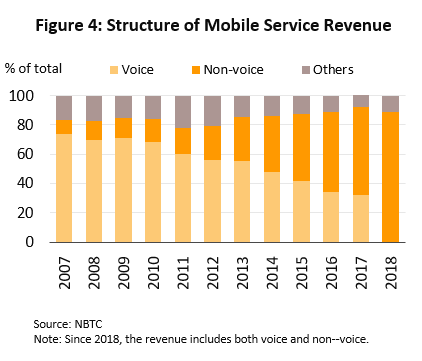

With a combined 97.8% share of the total user base, private operators enjoy almost complete control of the market (Figure 3) All mobile operators offer a wide variety of services, including voice and non-voice/data services, with the latter ranging from connecting to the internet to content provision and other services related to communications, and these services are offered and paid for on either a monthly billing basis or via prepaid, pay-as-you-go credit. Following the introduction of 3G services by operators and the development of handsets able to send and receive data at a suitably high rate, consumption of data services has jumped substantially and now, this has replaced voice-based services and become operators’ main source of income (Figure 4).

- The second group of mobile phone operators encompasses players that offer services on virtual networks, and which are thus called mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs). These companies offer mobile phone services, although they do not have a license to operate at a specified frequency themselves and do not have their own networks. Instead, they buy capacity from TOT and CAT Telecom, in some cases acting as wholesalers and resellers of services to customers Examples of companies in this group include (i) operators that use the TOT network, such as Buzzme and TuneTalk, and (ii) companies that operate on the CAT network, such as Real Move, 168 Communication, Penguin Sim and My World.

Overall, the mobile telephony market shows oligopoly with a small group of large players. Operating in this sector requires access to significant sources of capital to cover the costs of building a network and of keeping abreast of rapid technological changes; operators that are on a strong financial footing are able to exploit the advantages of being in this position and this gives them a monopolistic role within the market. In addition, restrictions that are imposed through official policy also help to influence the operators. These include specifying the initial price of operating licenses, the annual revenue sharing fee, and the requirements and timescale for investing in systems, installing equipment and expanding networks to ensure comprehensive coverage. Moreover, at present, foreign share-holding in mobile phone operators is limited to at most a 49% stake. Entry into the market by small and/or new operators is therefore difficult and new operators will first have to clear a large number of obstacles, so it is no surprise that in the government-held auctions for operating frequencies, no new entrants have appeared. Instead, those new players that have moved into the market have been MVNOs, which lease network capacity from state enterprises. In 2016, two such operators began to provide mobile phone services, these being The White Space (the Penguin brand) and Data CDMA Communication (with My World brand).

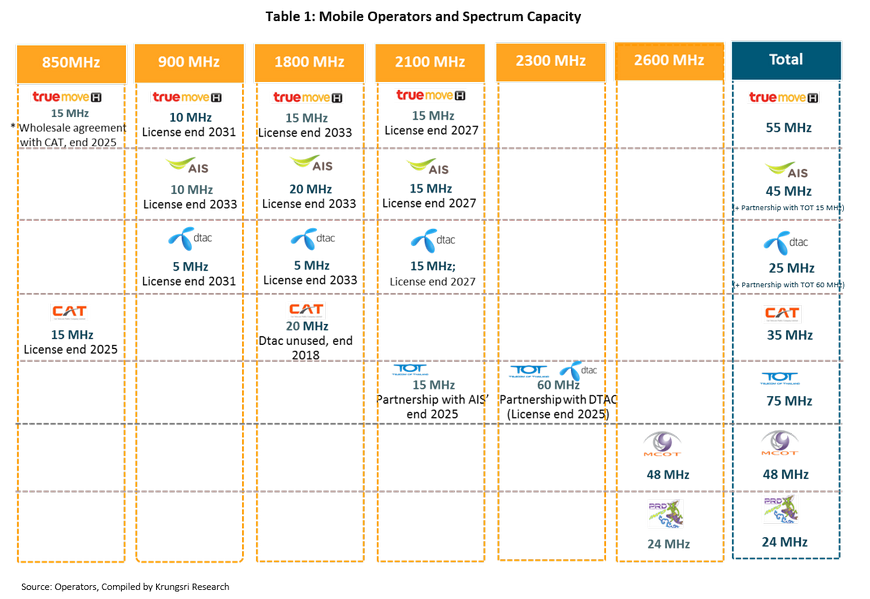

At present, the major players in the sector are, in order of the bandwidth that they operate: AIS, with 45 MHz (allied with TOT for another 15 MHz), TRUE, with 55 MHz, and DTAC, with 25 MHz (joined with TOT to manage another 60 MHz of bandwidth) (Table 1).

The development of the Thai mobile phone sector

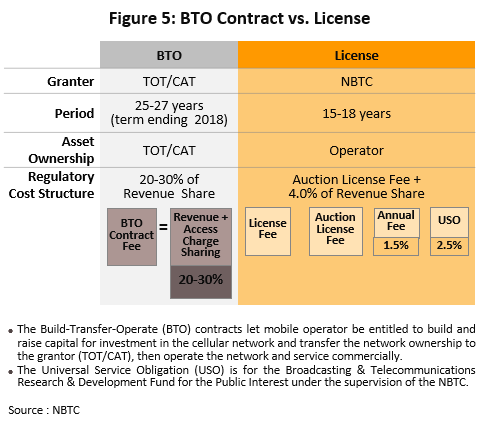

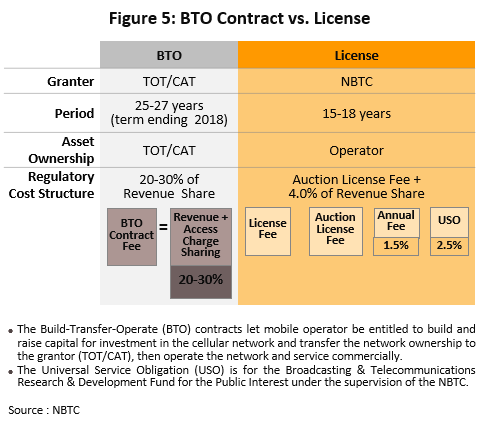

The first Thai mobile phone carriers were two state enterprises, the Telephone Organization of Thailand (TOT) and CAT Telecom Public Company Limited, because these organizations held the rights to the radio frequencies used for mobile communications and because they already operated as telephony service providers. Operations began first with TOT, which used the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system, carrying signals at 470 MHz, while CAT used the alternative Advanced Mobile Phone System, transmitting on 800 MHz. However, both organizations switched their model of operations to the granting of concessions to private operators which then provided services under a build-transfer-operate (BTO) system (Figure 5). In this model, the private service provider invested in building and running the network and then collected fees under a revenue-sharing agreement (with 20-40% of revenue being returned to the granter of the concession). On the termination of the agreement, ownership of the equipment used to provide services was transferred from the concessionaire to the concession granter (i.e. to TOT or CAT Telecom). The private sector companies that were initially granted concessions under this scheme were: (i) Advanced Info Services (AIS), which operated the analogue NMT 900 system, transmitting at 900 MHz, before switching to the digital GSM 900 system; and (ii) Total Access Communications (TAC and now DTAC), which operated the AMPS system on Band B at 800 MHz, before transitioning to a digital system, transmitting at 1,800 MHz. In addition, TOT and CAT granted local concessions to other mobile service providers, including DPC, Hutch and Real Move.

In 2005, officials granted a greater degree of freedom to the communications sector and for the first time these began to operate under a licensing system, although at that time, no new frequencies were allocated for use by mobile phone carriers. More important for mobile operators was the decision by officials the following year to raise the limit on foreign ownership of telecommunications businesses to 49%, which had previously been set at 25% in the Telecommunications Business Act (2001). In addition, the 2010 Act on Organization Assigning Frequency Waves and Supervising Broadcasting and Telecommunications Business Operations legislated for the National Broadcasting and Telecommunication Commission (NBTC)[3] to organize bidding for operators to purchase the licenses used to carry mobile traffic at specified frequencies. This paved the way for bidding for the 2.1 GHz frequencies in 2012, which in turn helped to kickstart the provision of 3G services within the country and it was thus at this point that smart phones and the associated telecommunications technologies really took off in Thailand. Under this new system, from 2013, as CAT and TOT concessions expire, these frequencies have been managed by the NBTC, which is tasked with organizing competitive bidding for them.

These developments have stimulated rapid growth for Thai mobile operators, especially after the introduction of 3G services. At the same time, the ability of operators to partner with non-Thai companies means that Thai players are able to draw on large investment pools and these have been sufficient to cover not just operating costs, such as the upgrades from analogue to digital systems, but also spending on the expansion of networks. As a result, these now help improve the quality and coverage of services more comprehensively.

To date, the NBTC has run five auctions to assign broadcast frequencies to mobile operators as follows;

- The 2.1 GHz frequencies (2012), which went to (i) Advanced Wireless Network (AWN), part of Advanced Info Services (AIS), for THB 14.63 bn, (ii) DTAC Trinet (DTN), part of Digital Total Access Communication (DTAC), for THB 13.50 bn, and (iii) Real Future, part of True Corp., for THB 13.50 bn.

- The 1.8 GHz frequencies (2015), which went to (i) True Move H Universal Communication (TUC), part of True Corp., for THB 39.79 bn and (ii) AWN, for THB 40.97 bn.

- The 900 MHz frequencies (2015), which went to (i) TUC for THB 76.29 bn and (ii) Jas Mobile Broadband (JMB) for THB 75.65 bn. However, JMB failed to fulfill its obligations within the specified time so the frequency was re-auctioned[4].

- The second offering of the 900 MHz frequency (2015) went to AWN for THB 75.65 bn.

- The 900 MHz frequencies (2018), which went to DTN for THB 38.01 bn, and the 1.8 GHz frequencies, which went to AWN and DTN, both of whom paid THB 12.51 bn.

Situation

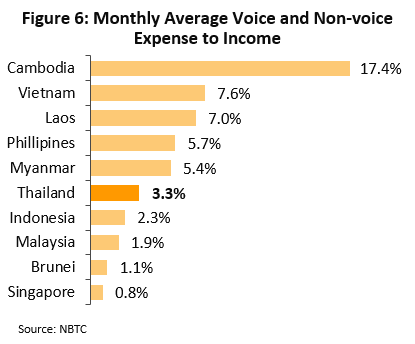

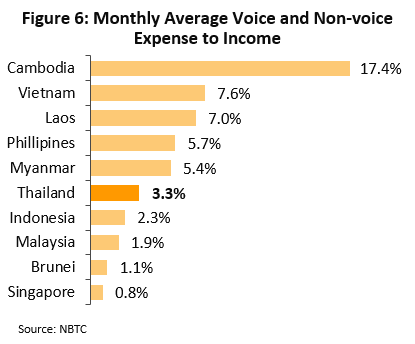

Although, as has been stated above, the sector is marked by the relatively low number of players within it, competition is stiff. Operators are focused on achieving income growth through the expansion of their user base and in pursuit of this, service providers use aggressive pricing strategies and are constantly investing in upgrades and expansion of networks. The result of this has been explosive growth in the use of mobile phones, and especially of smartphones. Indeed, the Mobility Report[5] states that in 2016, there were more smartphones than landlines in use in Thailand and that by 2021, the number of smartphones in the country is expected to double to 80 million from the 2015 total of 40 million. This rapid increase in the use of smartphones and consumption of mobile internet led to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) including Thailand in the group of ‘most dynamically improved countries within the past 5 years’ in 2015, while in 2017, Thailand was placed 78 out of 176 in the ICT Development Index, an improvement on its 2016 ranking (Table 2). In terms of costs, a comparison of these for combined voice and internet mobile charges relative to average monthly income in the ASEAN zone[6] showed that costs in Thailand were the 5th lowest in the region (behind Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia) and were 38% lower than the ASEAN average (Figure 6). It is likely that these relatively low costs for mobile voice and data are one factor underpinning high rates of consumption in the country.

Overall state of the sector in 2018

- Market shares for the main players (in terms of both income and subscribers) in 2018 are as follows:

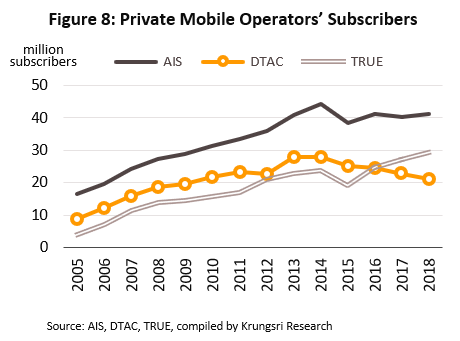

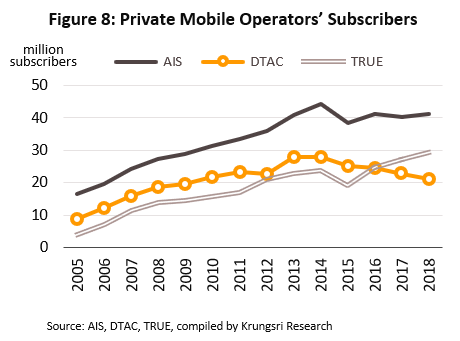

- AIS and its associated commercial group (AWN) had a 49.5% market share of all mobile telephony income and a total subscriber base of 41.2 million accounts, a rise of 1.1 million accounts from the end of 2017.

- TRUE Corp. and associated players (Real Move, True Move H, and TUC) had a 27.2% share. True also had 29.2 million subscribers, an increase of 2 million accounts from 2017.

- DTAC and its commercial network (DTAC Trinet) had a 23.3% share of sectoral income. DTAC’s subscriber base of 21.2 million accounts, falling by 900,000 accounts users from the end of 2017.

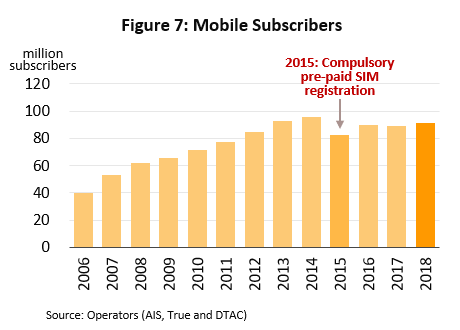

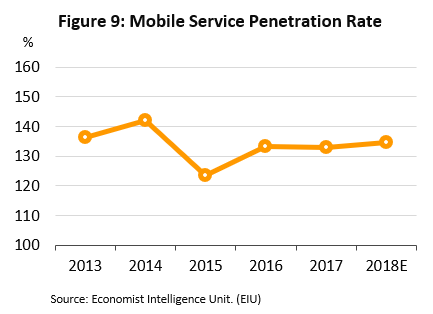

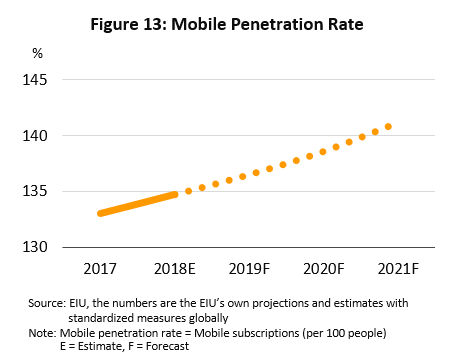

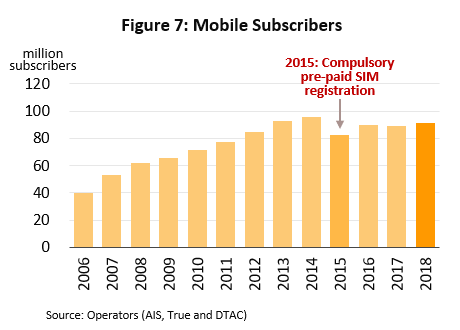

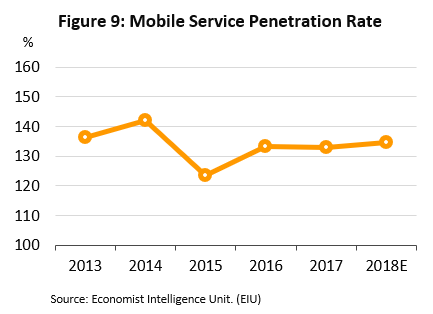

- Both the total number of subscribers to mobile phone services and the mobile penetration rate have steadily increased because consumers typically now use their mobile phone as their main point of contact, while consumption of data services on mobiles is also rising rapidly. At the same time, operators have been pursuing a strategy of constantly investing in their networks such that coverage now extends over a very wide part of the country, while speeds have increased notably too, even in more remote regions. The market has been further stimulated byhandsets that have fallen in price, even as their capabilities continue to improve. Thus by the end of 2018, there was a total of 91.6 million mobile phone subscriptions active in Thailand, up from 85 million in 2012 (figures 7 and 8), the year when 3G services first came into operation. Of total, 69.7 million were for prepaid (or pay as you go) accounts, while the remaining 21.9 million were postpaid (i.e. on monthly billing). The mobile penetration rate now stands at 134.7%, so there is now more than one mobile account per head of population (Figure 9).

In 2015, the number of mobile phone users dropped significantly as a result of the introduction of new government regulations that required the registration and confirmation of the identity of purchasers of prepaid telephone numbers; following the introduction of these measures, some subscribers gave up using their accounts

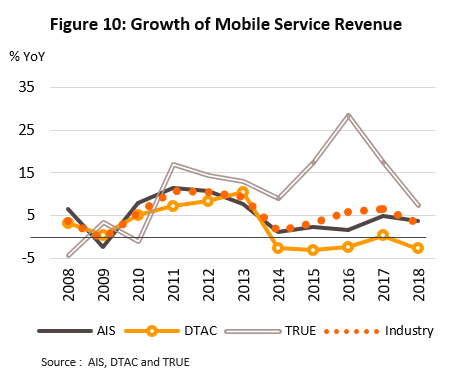

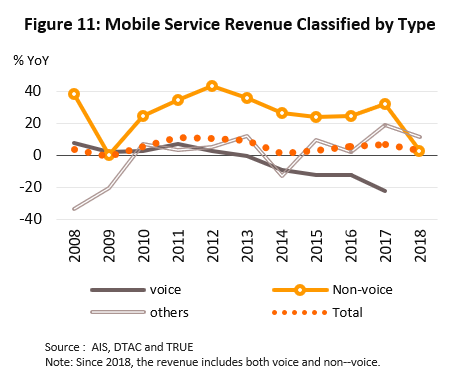

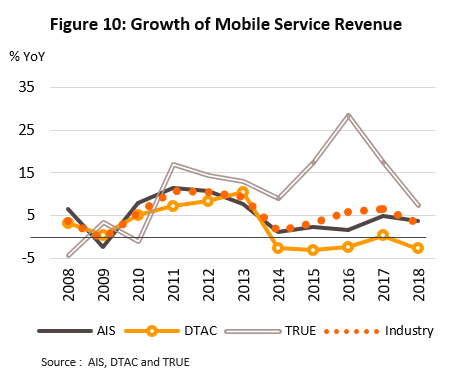

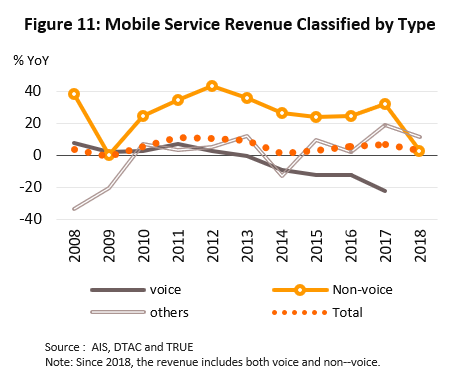

- Combined income from services (voice, data and other types) rose 3.1% YoY in 2018. Growth was supported by the continuing expansion of network coverage to include almost the entire country, and this helped to increase the number of accounts serviced by mobile carriers. In addition, growth has also come from consumer behavior that is increasingly favoring the use of mobiles as a platform for streaming video, from content provision by carriers, and from consumers’ preference for sending and receiving information through mobile phones, which has helped to boost the volume of online business conducted through mobile devices. Service providers have also adapted their marketing strategies and have developed monthly packages targeted at each segment of the market, and this move has then helped to encourage customers who use internet and data services to switch to monthly accounts, which typically report average revenue per user do prepaid ones. It is notable that average growth in income from services has slipped substantially from the highs of 2011-2012, when it averaged 10% annually (Figure 10). This change has been brought about by: (i) the pressure on operators to increase market share by competing fiercely on price, such as through offering cut-price packages and subsidizing the cost of mobile phones for subscribers; (ii) the only slow recovery in consumer purchasing power; and (iii) the fact that the market is likely close to saturation (as reflected in a mobile penetration rate that is over 130%), which is slowing the rate of expansion in subscribers.

Non-voice and data services are playing an increasingly important role in sustaining income growth for operators as consumer behavior continues to shift and with this, consumption of data services rises. Therefore, income from data services posted increasing share of 60.6% of all income in 2017, higher than 22.1% in 2012. On the other hand, income from voice services showed continuously declining share. For 2018, income from services (voice and data) rose 2.5% YoY (AIS +1.3%, True +7.9%, and DTAC -0.7%). However, other incomes increased 11.2% (Figure 11).

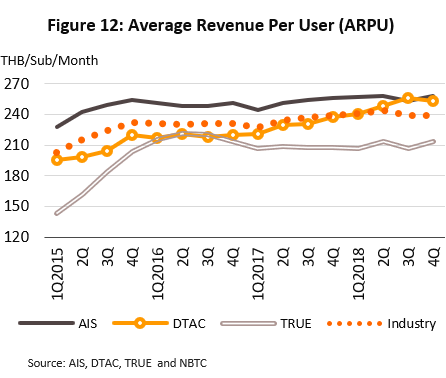

- Average revenue per unit (ARPU) increased at a low rate on ongoing price competition between operators looking to expand their subscription base. For 2018, the industry ARPU average was THB 241 (+3.0% YoY). In terms of individual operators, the AIS ARPU was THB 256 (+1.7% YoY), the DTAC ARPU averaged THB 254 (+4.9%) and the True ARPU was stable at THB 208 (Figure 12).

- Pressure from business costs relaxed somewhat in 2017 thanks to the government decision to cut fees for operators’ universal service obligations (USO)[7] from 3.75% to 2.5% of income from services. This had effect from May 2017 and because of this, operating costs arising from government requirements fell from 5.25% of service income (USO fees of 3.75% combined with business operating fees of 1.5%) to 4%.

Industry Outlook

Mobile phone service providers will see positive business conditions in the period 2019-2021, and Krungsri Research estimates that growth should run to an annual average of 4-5%. This outlook is supported by the following factors.

- Demand for accessing the internet via mobile telephones will help to displace voice services from their central role in revenue generation and to replace this with income from data services. Ericsson estimates that the number of smartphones in Thailand will increase to 100 million units in 2020 from the 65 million units in use in 2017, and this will prompt service providers to put in place a wide range of packages mixing telephony and internet services as they attempt to increase the number of subscribers on monthly billing accounts (which tend to spend more per account than do prepaid accounts). This would then help to increase average revenue per unit.

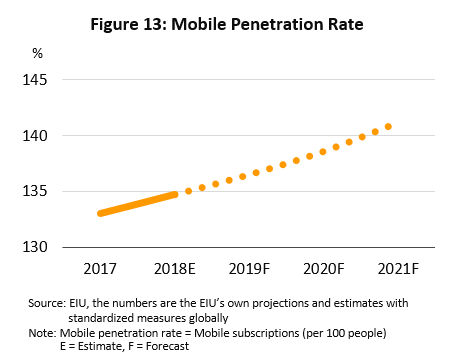

- Opportunities to expand their provincial subscriber bases will increase as operators complete the roll out of 3G/4G networks to customers in remoter regions. These network upgrades will increase network capacity and average speeds for mobile broadband and so will help to stimulate mobile internet use and thus consumption of mobile services in new parts of the country, though this will be particularly important in provinces that have greater purchasing power. Indeed, the EIU estimates that in Thailand, the number of mobile phone accounts per 100 people will rise from 133.0 in 2017 to 141.2 by 2021 (Figure 13).

- Some of the weight of business costs will be removed following the switch away from a concession-based system, under which operators have to return a high proportion of their income (20-30% of that from services) to the government as concession charges. Instead, the current system is based around competitive bidding for licenses, and fees for these are both paid on a pre-arranged schedule and tend to be lower than those for concessions. Beyond this, the government has cut USO fees to 2.5% of income from services, down from its earlier level of 3.75%.

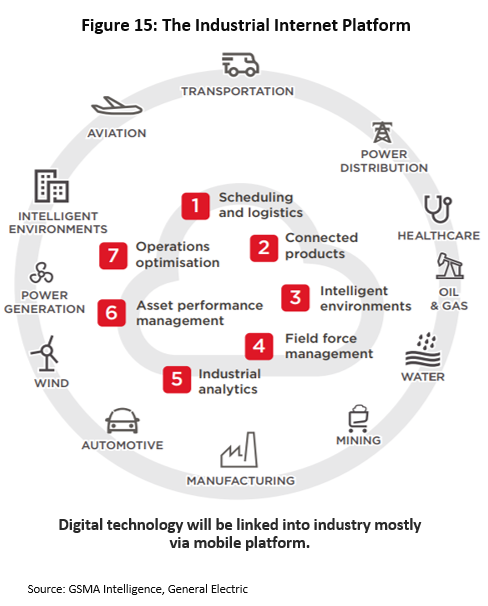

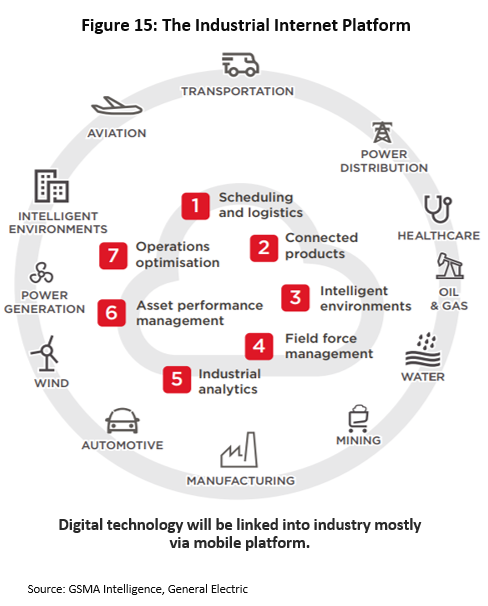

- In addition, the rapid speed of innovation and technological change is forcing businesses to increasingly enter the digital world and to use e-commerce applications to market and to sell their goods and services. Consumers too are increasingly at ease using online services and Ericsson8/ reports that Thailand is ranked third in Asia for the use of smartphone applications. Apps that are popular in the country include those for use in finance, buying goods and services, entertainment, social media, travel and health, and these will have an important impact on the growth of mobile phone companies. Meanwhile, the internet of things (IoT) will be deployed in almost all sections of the economy and IDC (Thailand) believes that between 2015 and 2020, use of the IoT in Thailand will grow by an average of 13.2% per year, while by 2019, Thais will be using an average of 2.2 IoT-enabled devices each. Naturally, this will then stoke additional demand for mobile phone services in the future (Figure 15).

- The government’s push to develop Thailand’s digital economy and to connect the population to digital services will help to develop national telecommunications infrastructure. Recent projects undertaken by the government that fall under this heading include the provision of high-speed internet connections and mobile phone networks to almost 30,000 households in border areas, the installation of 10,000 free Wi-Fi access points, the establishment of 600 community digital centers, and policies such as the development of the Eastern Economic Corridor, which will increase demand for telecommunications services through an expansion of the user base.

- Related industries that will benefit from sectoral expansion include those involved in the installation and provision of network coverage, which will have the opportunity to generate additional income given mobile phone service providers’ rolling plans for network upgrades as their business expands. In addition, further opportunities will exist in other areas, such as the transition from overhead to underground cabling.

However, despite this generally positive outlook, operators will still face a number of challenges and these may limit income growth.

- Competition on price will tend to stiffen as players look to build their subscriber base and to expand their share of the sector’s income from data services. Thus, although the total number of users of mobile phone services may increase, average revenue per unit will likely remain flat or increase only slightly. Operators also have to carry the costs of constantly upgrading their infrastructure, as well as for bidding in auctions for broadcast frequencies, as they have done in the past and will do again in the future. This will therefore help to restrict profitability.

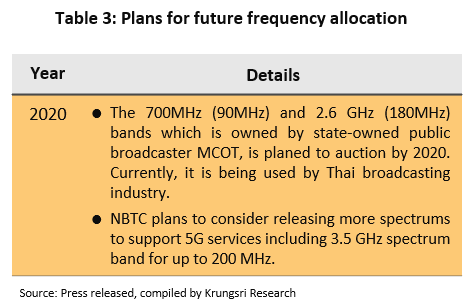

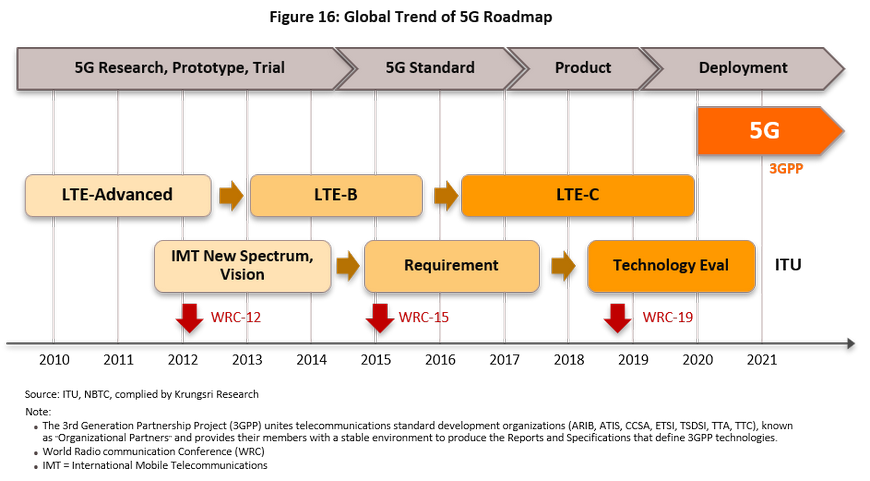

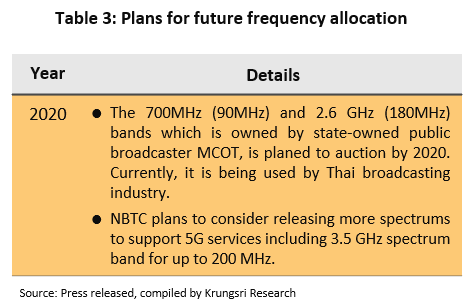

- Transmission frequencies for mobile telephony are limited and government plans over how to allocate these through auctioning are unclear, with the result that operators’ ability to plan effectively is hindered by uncertainty (Table 3). In the period 2019-2021, it is expected that 5G technology will begin to play an increasingly important role in business and in daily life. 5G systems receive and transmit a large volume of data in each transmission and equipment that uses this technology, such as electrical appliances, smart cars and smart homes, will be connected to each other through the internet of things, with the mobile phone playing a pivotal role in increasingly at ease using online services and Ericsson[8] reports that Thailand is ranked third in Asia for the use of smartphone applications. Apps that are popular in the country include those for use in finance, buying goods and services, entertainment, social media, travel and health, and these will have an important impact on the growth of mobile phone companies. Meanwhile, the internet of things (IoT) these networks. However, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) states that providers of 5G services (Figure 16) will require at least 100 MHz of bandwidth[9] if they are going to be able to transmit sufficiently large quantities of data to make the service viable, while the NBTC believes that 5G operators will need 690 MHz of transmission frequencies, compared to the current 420 MHz. Unfortunately, at present, the Thai authorities lack a clear plan for how to allocate frequencies and this is increasing risk for players in the sector, and these are now facing difficulties in planning for business operations and investing in new equipment and infrastructure.

- Other challenges faced by service providers include: (i) the setting by the authorities of caps on service charges and official standards for the provision of services; (ii) the expansion of the service area, as set by the government; (iii) the push to invest in expansion of network coverage, which may raise costs; and (iv) the implementation of government policy, such as the speed of disbursements for work on infrastructure and communications projects (which may not keep pace with official plans) and the slow work on planning the auctioning of broadcast frequencies.

Krungsri Research’s view:

The outlook for mobile phone carriers is broadly positive and Krungsri Research estimates that players should see growth in income from services of 4-5% annually, supported by a general expansion in the economy that is lifting consumption, a boost in the subscriber base as network coverage extends to cover almost the whole country, and increasing demand for data services. However, players will also come under pressure from costs arising from the need to increase the number and capacity of base stations and to pay for the operating licenses that cover the present period.

- Mobile phone service providers: Income for carriers will likely grow steadily on increasing demand for mobile phone services. This will be underpinned by: (i) growing consumption of mobile data services; and (ii) government policy promoting the digital economy, which has had the effect of extending the coverage of telecommunications infrastructure in the provinces (e.g. through the ‘Net Pracharat’ and border internet projects), and the development of the special economic zones and the Eastern Economic Corridor. These policies will help to build demand for mobile phone and data services from consumers in the provinces, though at the same time, strong competition on price and high operating costs will tend to put limits on growth in profitability.

- Network installers: These companies will experience growth in line with expansion in telecommunications networks according to their particular requirements, such as for 3G and 4G wireless networks, local digital television networks and network infrastructure supporting the development of the digital economy (e.g. for internet access).

- Income for large players will grow solidly and these operators will be able to expand into markets in neighboring countries. These players may also benefit from work on changes to network types (e.g. from overhead to underground cabling).

- Income for smaller operators and for subcontractors will tend to remain flat. These operators are hindered by being at a disadvantage relative to large players due to their weaker business networks and higher operating costs, in addition to the fact that within this segment, the large number of players stokes strong competition.

- Distributors/retailers of handsets and other devices: Income from sales will tend to remain flat or to decline somewhat as, while demand for smartphones continues to strengthen, the cost of handsets is falling. Operators will face strong competition, both from other retailers of handsets and from mobile phone carriers that are subsidizing the cost of handsets for their subscribers, while the rapid turnover of models, whether through the speed of innovation or because of changing tastes, also exposes players to the risk of stock losses from holding out of date models. Distributors/agents and wholesalers, which benefit from being in a stronger negotiating position, will be exposed to lower levels of risk than will smaller retailers.

[1] Communication market includes fixed-line handset, mobile handset, telco network equipment, and wireless equipment

[2] Before taking their current form as TOT and CAT Telecom, the forerunners of these organizations had responsibility for managing, respectively, domestic and international telecommunications.

[3] The National Broadcasting and Telecommunication Commission (NBTC) is an independent state agency established by the Act on Organization Assigning Frequency Waves and Supervising Broadcasting and Telecommunications Business Operations (2010). Under this Act, two sub-committees have been established to carry out the work of the NBTC. These are (i) the broadcasting committee, which manages matters related to television and radio and (ii) the telecommunications committee, which, naturally enough, looks after issues related to telecommunications.

[4] JMB was unable to make the payments required to cover its license and guarantees in the specified time-frame and so the NBTC invalidated that auction, holding a new one (its fourth) on May 27, 2016.

[5] Ericsson Mobility Report: June 2016

[6] Research comparing mobile telephone costs in ASEAN countries conducted by the NBTC, published in 2017.

[7] The fund for the research and development of radio, television and telecommunications for the public benefit, or alternatively, the ‘universal services obligation’ (USO) is funded from charges]income-sharing arrangements with radio and television broadcasters and telecommunications companies. This money is then used to support the development of these services in areas that currently lack them or related activities.

[8] Ericsson Mobility Report: June

[9] Bandwidth refers to the size of the data pipeline available to service providers; the bigger the pipeline, the more data that can be sent at the same time.

.webp.aspx)