Following a sharp contraction in 2020, over the period 2021 to 2023, demand for land (to buy or rent) on Thai industrial estates is forecast to grow by an average of 20% per year. This outlook is supported by: (i) progress on government infrastructure projects, especially in the EEC, which will then crowd in greater private-sector investment; (ii) investor sentiment that will tend to strengthen in step with a return to growth in both the Thai and global economies; (iii) a move by some foreign companies to relocate production facilities to Thailand or for those already in the country, to expand these; and (iv) government efforts to stimulate the economy and to reform the investment regulatory environment.

In the coming period, operators will tend to develop industrial estates in the form of smart parks that are equipped with modern production technology, transportation and communications equipment, and power supplies, while to support growth in future industries, operators will, in addition, look to develop sites that are more environmentally friendly. Players within the industry will also try to build revenue for industrial estates by investing in activities in other parts of the economy, especially in high-tech industries (e.g., digital platforms).

Overview

Industrial estates make available land for purchase or rent to industrial and commercial operators. Providers of industrial estate services also supply businesses located on these sites with access to amenities and utilities such as electricity, water, flood defenses, centralized sewage services and so on.

Within Thailand, industrial estates come under the oversight of the Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand (IEAT), which manages both (i) industrial estates that the IEAT owns and operates alone, and (ii) industrial estates that the IEAT owns and operates in partnership with private-sector players. In addition to industrial estates, industrial parks and industrial zones also exist and broadly speaking, these share the characteristics of industrial estates, though they are privately owned and run[1]. These come under the control of the Board of Investment (BOI), which has assigned their regulation to offices of the Department of Industrial Works in each province.

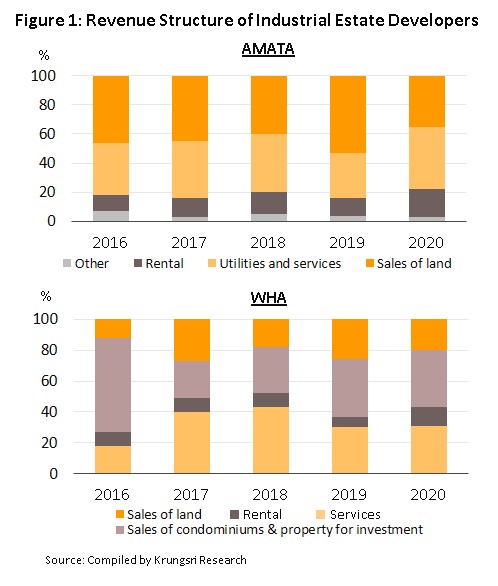

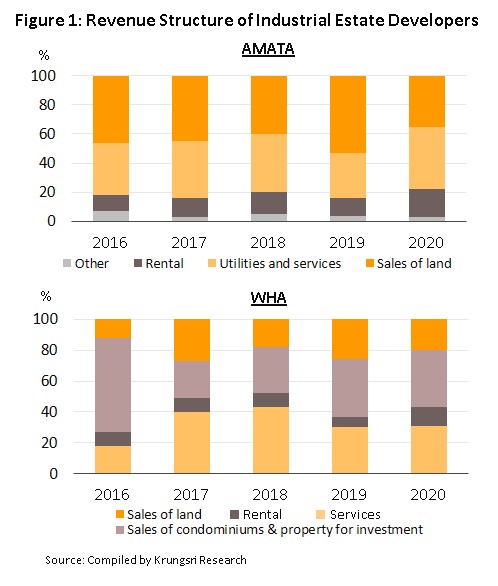

Revenue for these businesses comes from two principal sources: (i) the sale and leasing of land; and (ii) revenue from the leasing of factories and warehouses, and for the supply of utilities (e.g., water and electricity). The latter is a form of recurring income, and this then helps to reduce players’ exposure to the risk of fluctuations in revenue that may arise from relying on the sale of land (the revenue streams of two major players are given in Figure 1).

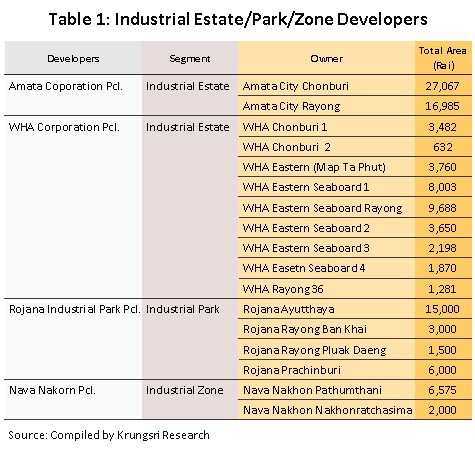

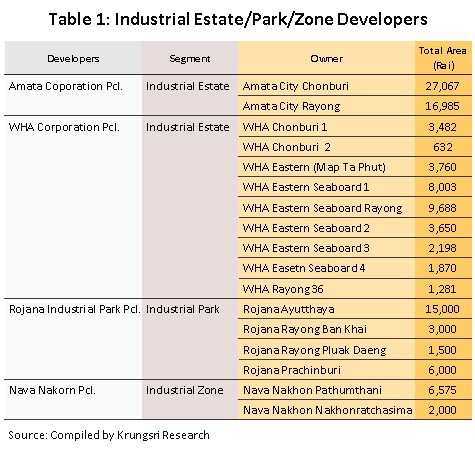

Businesses may prefer to move onto sites on industrial estates rather than build from scratch on empty land because the former are already equipped with the requisite infrastructure, utilities and transportation links. Establishing operations on industrial estates may also benefit companies financially, since if they do this, they may qualify for incentives provided by the government in the form of tax relief or other forms of investment support. The two major operators of industrial estates in Thailand are Amata Corporation and WHA Group, while Rojana Industrial Park and Navanakorn are the most important operators of industrial parks and industrial zones.

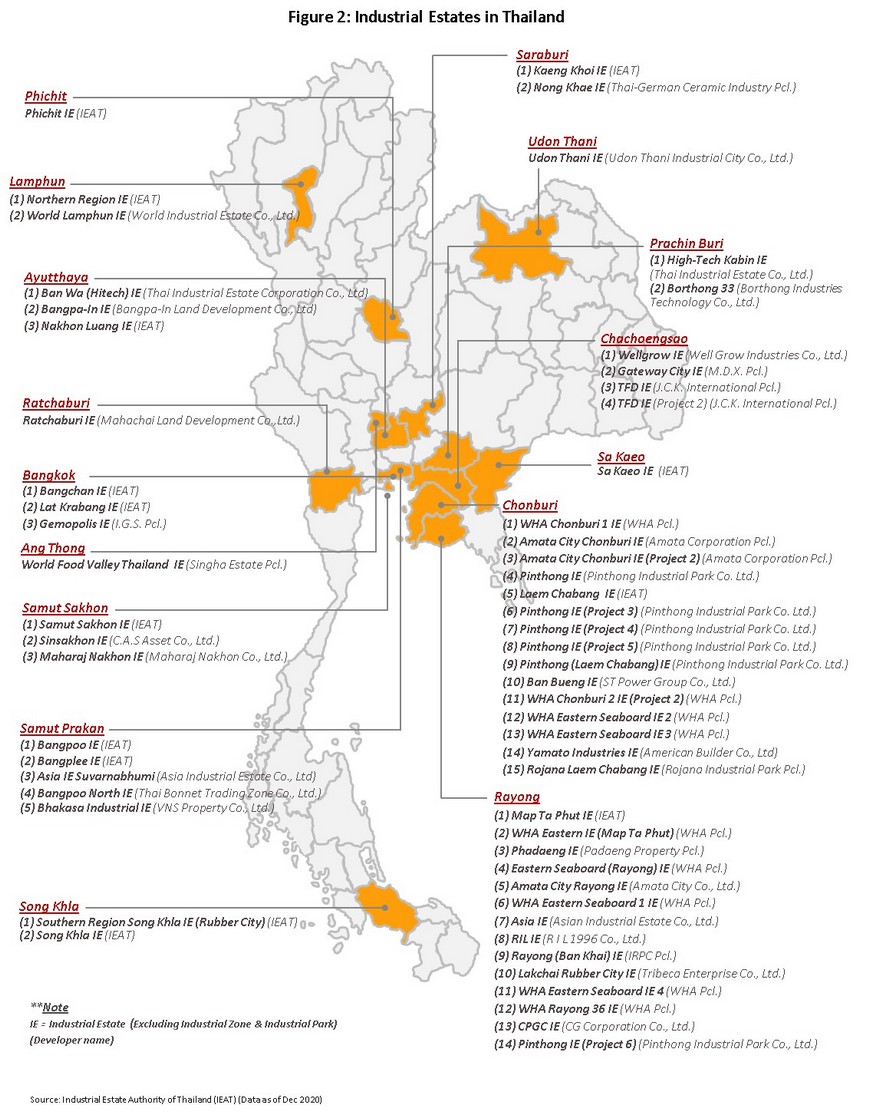

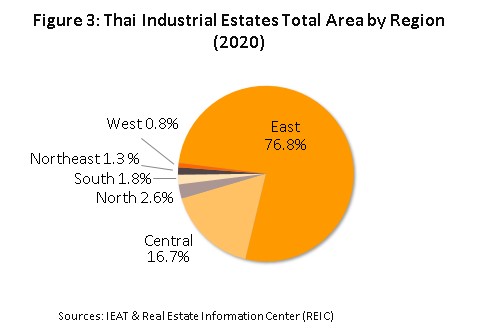

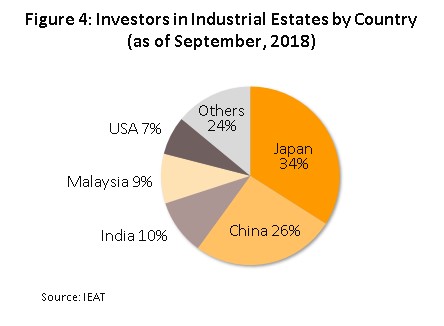

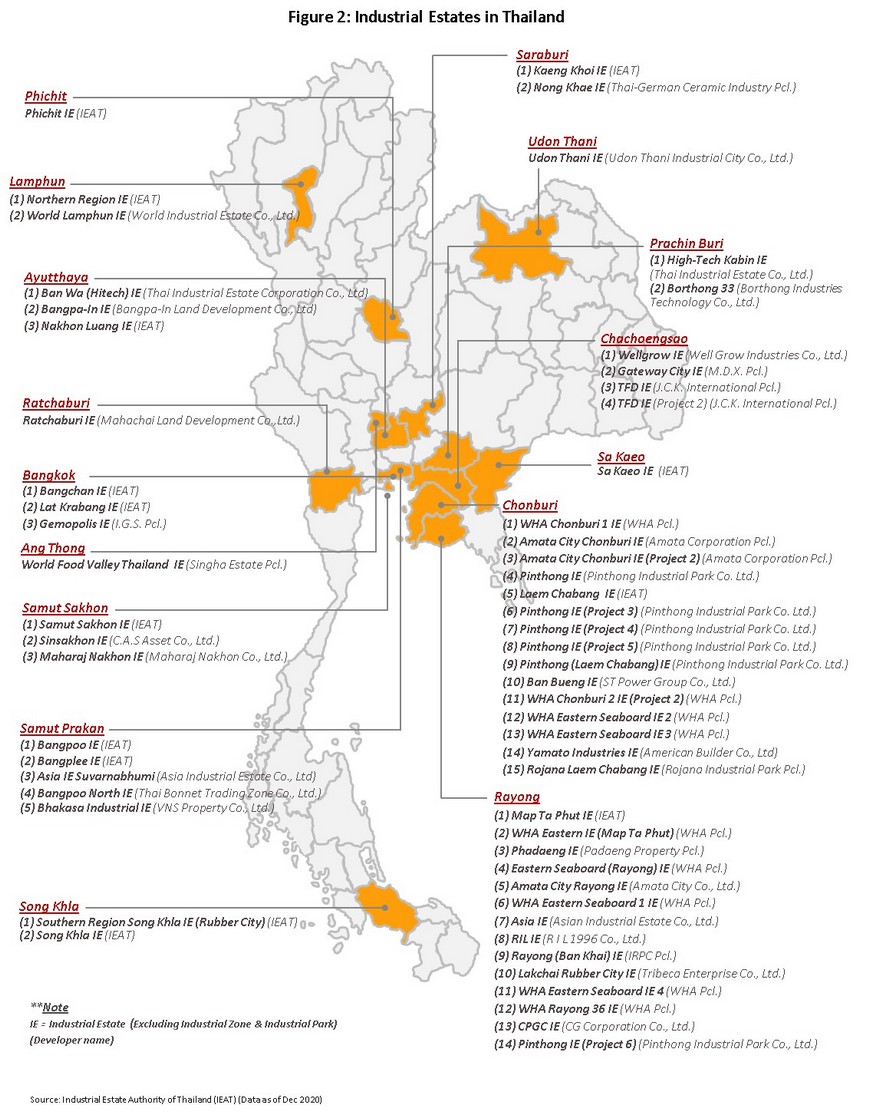

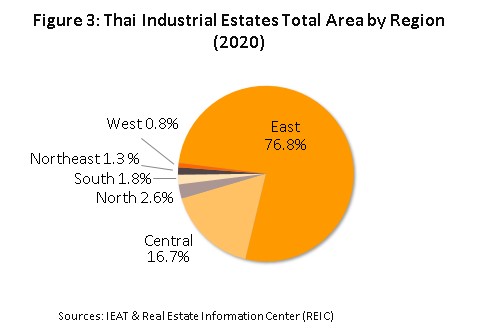

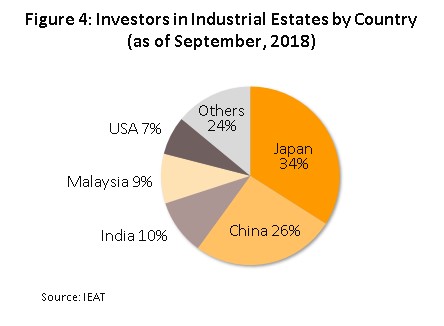

The most important factors influencing the growth of the industrial estate sector are: (i) the state of the domestic and international economies and of local political conditions; (ii) multinational companies’ approach to investing and establishing production facilities in Thailand; (iii) the physical and geographical conditions of the country; and (iv) the extent to which government rules and regulations support investment in domestic industrial estates, and the level of concessions and incentives that the government provides for investors in the sector. As of the end of 2020, there were 60 industrial estates in Thailand, spread across 16 different provinces (Figure 2). Of this total, 14 sites were operated by the IEAT alone and the remaining 46 were joint ventures with the private sector. The eastern region housed the vast majority of these (Figure 3), with 76.8% of the total, followed in importance by the central area (including the Bangkok Metropolitan Region), which contained another 16.7% of the total. In terms of investors’ origins, Japanese operators are by value the most important overseas players active in the industry, followed by those from China and India (Figure 4).

Across the country, the growth potential of the industry varies from area to area. Details for individual regions are given below.

- The eastern region: This area, which extends over the provinces of Chonburi, Rayong, Chachoengsao, Prachinburi and Sa Kaeo, has the greatest potential for growth since it is home to a wide range of major industries, including oil refining and petrochemicals, chemicals, auto assembly and auto parts manufacturing, electronics, and food processing. As such, the government has provided ongoing support for the development of manufacturing within the region. The outcome of this has then been that not only does the eastern region have the greatest concentration of industrial estates in the country, it also continues to attract the most interest from investors. Moreover, for some time now, manufacturers operating on industrial estates in other provinces have also been relocating their factories to this area because of its connection to the Eastern Seaboard Development Program and its well-established transportation network. Indeed, the area has convenient road transport connections, is close to airlinks (Suvarnabhumi and U-Tapao airports) and commercial shipping (Laem Chabang and Map Ta Phut ports), and Bangkok is nearby and easily accessible

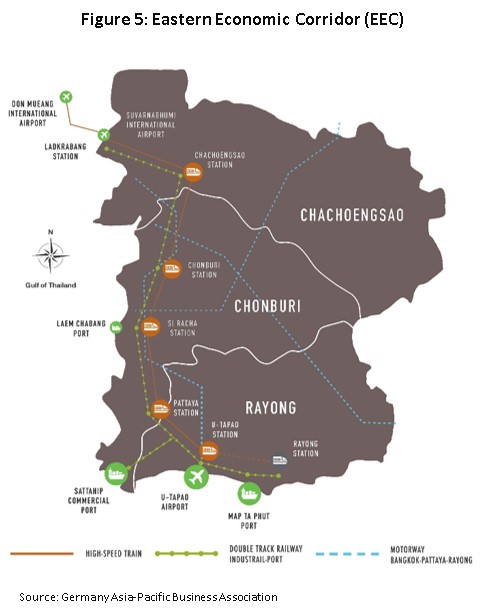

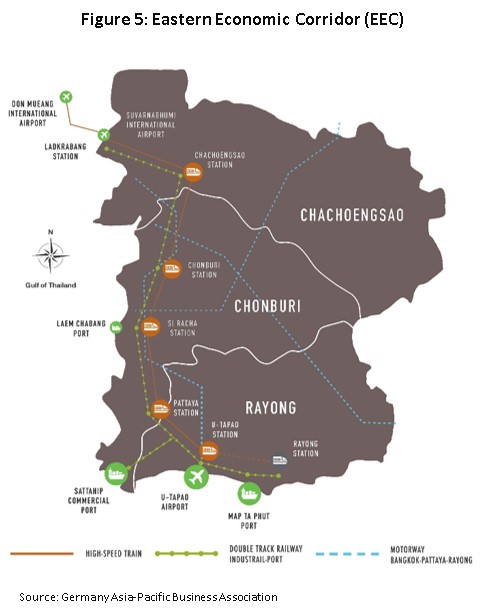

In addition, Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao have been designated as home to the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) development. This area has been chosen for this strategically important development thanks to the provision of infrastructure in these provinces. Because of this, private-sector players can move straight in and begin operations almost without delay. The government is especially hoping that investment will be forthcoming in its twelve targeted industries[2], all of which are technologically and capital intensive. This hope is underpinned by government spending on infrastructure megaprojects that will help to strengthen the area’s transportation network and so increase its potential. The government is thus working to attract investment from domestic and international sources for programs including the development of: (i) the high-speed rail link connecting the area’s 3 airports; (ii) U-Tapao International Airport; (iii) the intercity motorway; (iv) the dual-track railway; (v) phase 3 of Laem Chabang Port; and (vi) phase 3 of Map Ta Phut Industrial Port (Figure 5).

- The central region: This region benefits from its location, which is a center of manufacturing and the focus of the national transport and transportation networks. The central region includes Bangkok itself, which is home to per unit, the most expensive industrial land in the country, and provinces that contain important industrial estates, including Samut Prakan, Ayutthaya, Saraburi, Ratchaburi and Samut Sakhon. Auto parts, electrical appliances and electronics manufacturers are concentrated in the area, in addition to industries that utilize local resources, such as food processing and construction materials, and factories operated by SMEs. However, industrial estates in the area were badly affected by the extensive flooding in 2011 and the lease and sales of all industrial space in the region came to just 8.6% and 4.8% of the national total in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Following this low, the situation improved somewhat, and between 2014 and 2018, these figures returned to double-digit growth, a fact that helps to illustrate the continuing ability of industrial estates in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region and the wider central zone of the country to attract interest from investors.

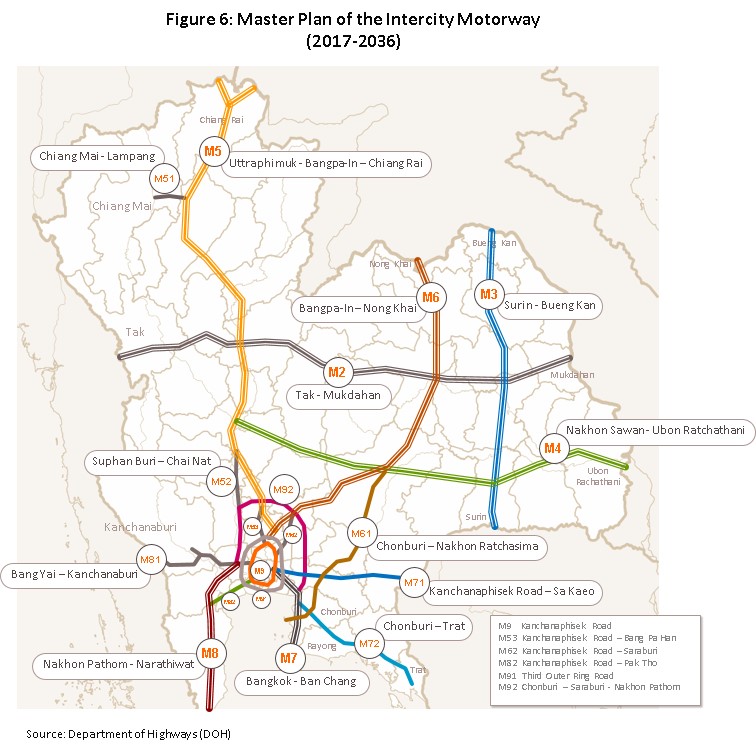

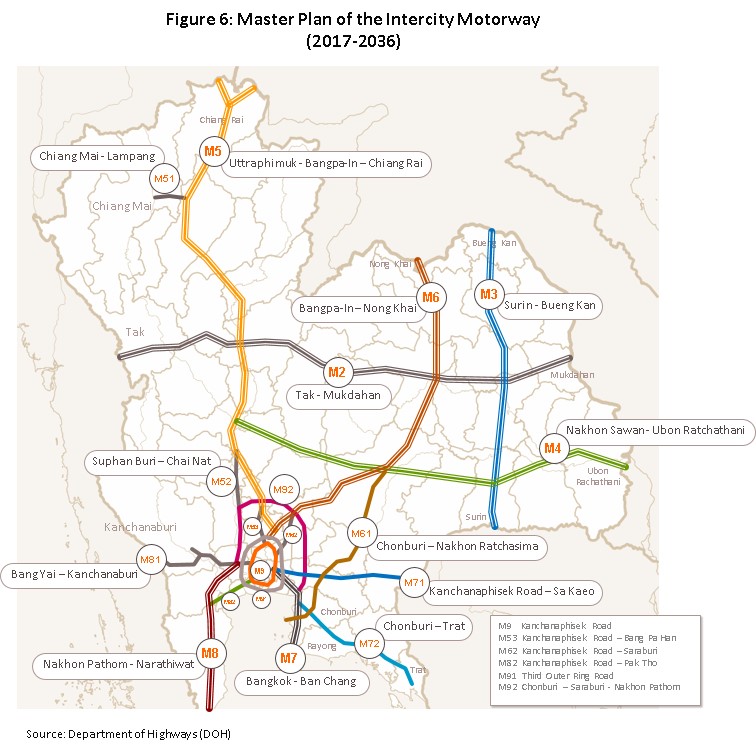

- The northern and northeastern regions: Generally, industrial estates in these areas host food processing industries together with some electronics manufacturers, but transportation links are inferior to those in other parts of the country and this has tended to curb interest from investors. However, progress on developing roads (Figure 6) and rail links in the north and northeast that will connect Thailand to its neighbors (Northern line: dual-track railway Denchai-Chiang Rai-Chiang Khong; Northeastern line: dual-track railway Bann Phai-Nakhon Phanom) and then on to China and Vietnam should help to stimulate future investment. At present, industrial estates are located in the northeastern province of Udon Thani and in the northern provinces of Lamphun and Phichit.

- The western region: This area is largely still awaiting development. The Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand had planned to develop a new industrial estate to support and connect to the proposed industrial zone and deep-water port in Dawei, Myanmar, but the importance of the latter has slipped and the authorities in Myanmar are instead now focusing on the development of an industrial area in the Thilawa special economic zone. Given this, the impetus for investing in industrial estates in the western region has slackened, though at present, there is an industrial estate in Ratchaburi

- The southern region: This region is being developed with the goal of improving connections between the south of Thailand and Malaysia. The area’s major industry is rubber cultivation, but at present, it is host to only a single industrial estate (in Songkhla). In 2016, the IEAT decided to halt development of a new industrial estate in Pattani province planned for producers of halal food since interest from major operators, both Thai and international, was lacking. Unfortunately, the ongoing disturbances in the deep south and subsequent fears over security combined with an insufficient local supply of electricity have meant that development of industrial estates in this area has not proceeded as might have been hoped.

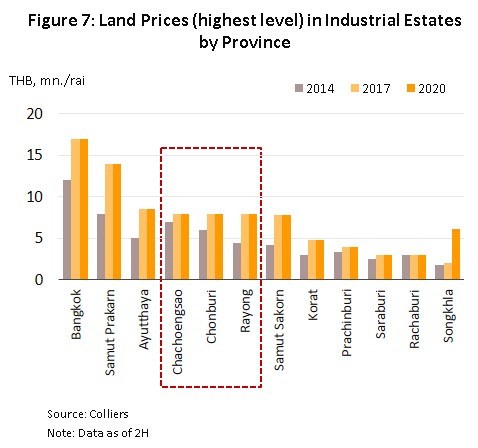

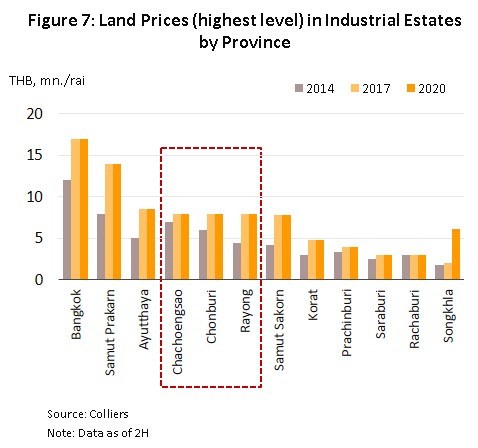

Land prices (for both sale and rent) in industrial estates vary from one site to the next and depend on factors including (i) location, (ii) the provision of utilities, (iii) access to transportation and travel links and (iv) access to raw materials (Figure 7). Bangkok’s position in the center of the country’s land, water and air travel networks means that land on industrial estates in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region is the most expensive in the country and this also tends to lift prices in adjacent areas, so industrial estate land prices are high in areas such as Samut Prakan, too. Space in the EEC (in the provinces of Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao) is the second most expensive in the country and in 2020, prices in the three provinces of the EEC rose as high as THB 8 million/rai, a roughly 50% rise on the THB 5.3 million/rai seen in 2014, before the start of wider government efforts to promote the EEC (source: Colliers International). This buoyancy in the market points to the potential of the area for future development, an important factor in attracting interest from investors and one that is further supported by current government policy.

Situation

In 2019, the market for industrial estates expanded following 5 years of sluggishness. This return to life was helped by (i) economic growth (GDP grew 2.3% in 2019, following growth of 4.2% in 2018), and (ii) clearer progress on infrastructure projects that support the development of the EEC. The latter follows the signing of construction contracts, including those for phase 3 of the Map Ta Phut industrial port development and the high-speed rail link connecting the area’s 3 airports.

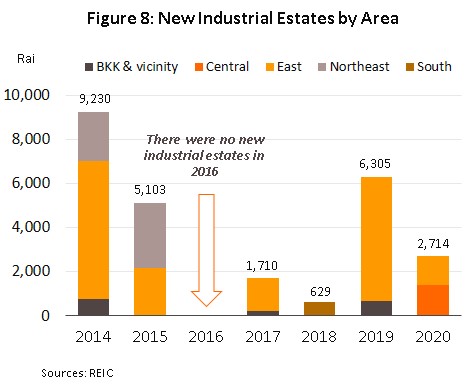

- Supply: 4 new industrial estates were established in 2019 with a combined footprint of 6,305 rai (an increase of 902.4% on a year earlier) (Figure 8). 3 of these new sites were in the eastern region and with an area of 5,656 rai, these accounted for 90% of all new supply in the year.

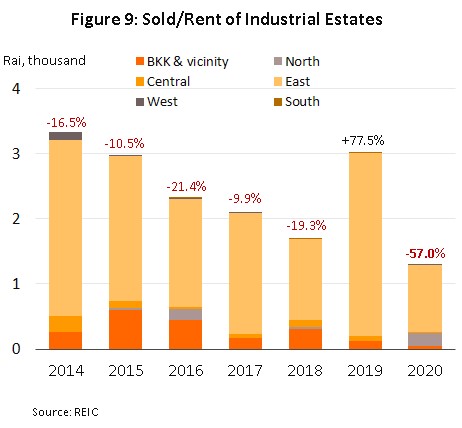

- Demand: Sales and leases of land on industrial estates rose 77.5% from the 2018 level to 3,022 rai (Figure 9). 2,812 rai of this was in the eastern region (93% of all sales and leases), a rise of 124.6% thus underlining the continuing potential of the area to attract greater interest than elsewhere in the country.

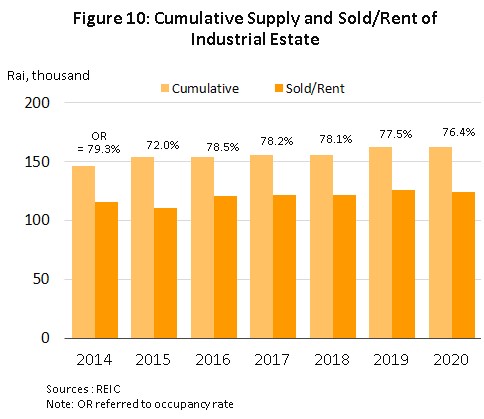

At the end of 2019, the cumulative supply of land sold or leased on industrial estates stood at 126,004 rai, giving an occupancy rate of 77.5% (Figure 10).

However, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy (GDP fell 6.1% in 2020 compared to growth of 2.3% in 2019) pushed the market for land on industrial estates into a sharp contraction in 2020.

- Supply: 2 new industrial estates were established in the year, these having a combined area of 2,714 rai (-57.0%) (Figure 8). These were: (i) Pinthong Industrial Estate 6 in Rayong province, which has an area of 1,322 rai; and (ii) World Food Valley Thailand Industrial Estate in Ang Thong Province, which covers 1,790 rai. Given this, as of 2020, Thailand was home to 60 industrial estates in 16 different provinces. Combined, these covered 162,078 rai (Figure 10), with 76.8% of this located in the eastern region.

- Demand: The spread of COVID-19 and the need to impose lockdowns meant that alongside other factors, it was extremely difficult for potential investors to travel to Thailand to view sites. Because of this, sales and leases slipped 57.0% to 1,300 rai (Figure 9), with 80% of total sales and leases (1,041 rai) happening in the eastern region. This represented a fall of 63.0%, with declines steepest in Rayong province (-78.5%).

At the close of 2020, total sales and leases of industrial estate space came to 123,861 rai, meaning that for the year, the occupancy rate dropped to 76.4% from 77.5% a year earlier (Figure 10).

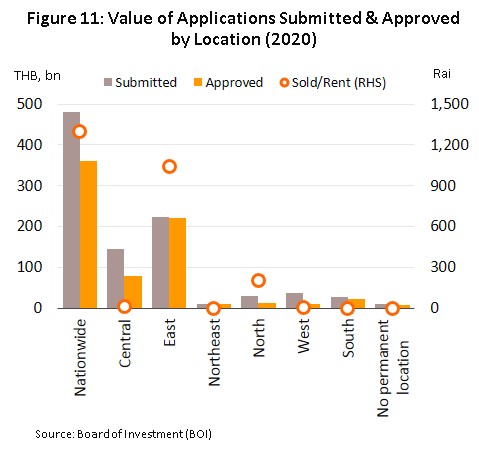

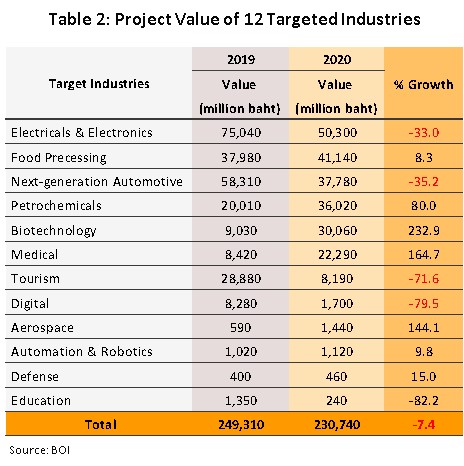

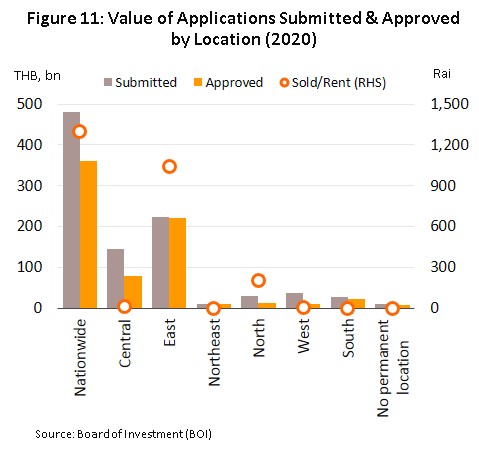

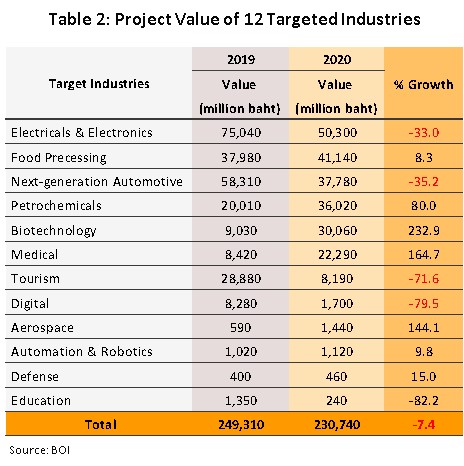

In 2020, the value of applications made to the BOI for investment support crashed 30.4% to THB 480 billion. 46% of this, or THB 220 billion, was for planned investments in the eastern region. Although this represented a decline of 43.5%, a sharper drop than the national average, this continuing predominance of the area matched demand in the market for land for rent or sale on industrial estates, where the eastern region remains the most active (Figure 11). Of the government’s target industries for the EEC, applications for investment support were highest by value in the categories of electrical goods and electronics, followed by food processing and then by next-generation automotive industries (Table 2).

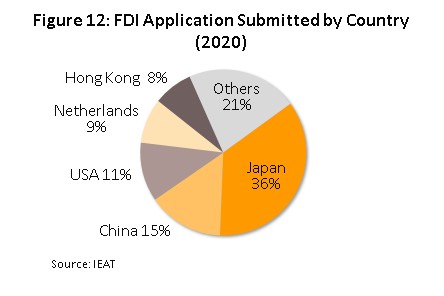

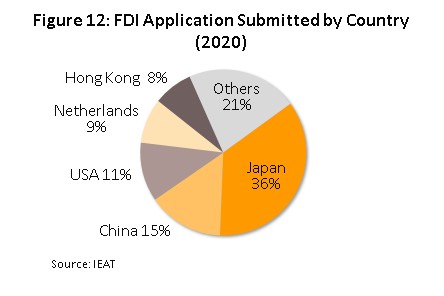

Overall applications for BOI investment support for inflows of foreign direct investment also contracted in the year, slumping 54.2% to THB 210 billion, though by value, applications for investments in industrial parks and zones weakened at a slower rate (-19.5%). Accounting for 36% of the total (THB 76 billion), Japanese investors contributed the largest individual slice of this, followed in importance by those from China and the United States (Figure 12).

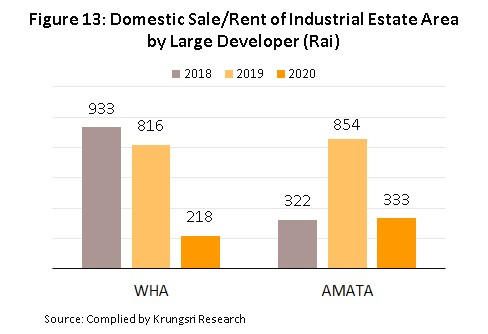

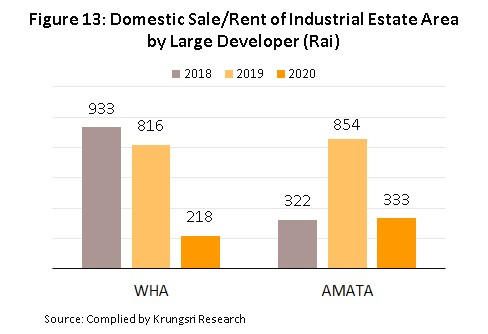

Sales of land by the main players in the industrial estate market fell heavily on the 2020 lockdown and the generally depressed investment environment (Figure 13). Thus, overall revenue for WHA and Amata Corporation fell by respectively 28.3% and 28.8%, though against this, recurring income (e.g., from rents) rose 7.5% for Amata.

Outlook

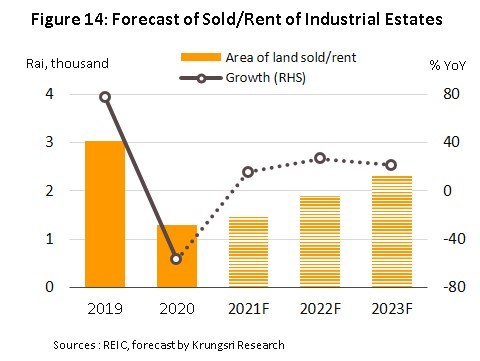

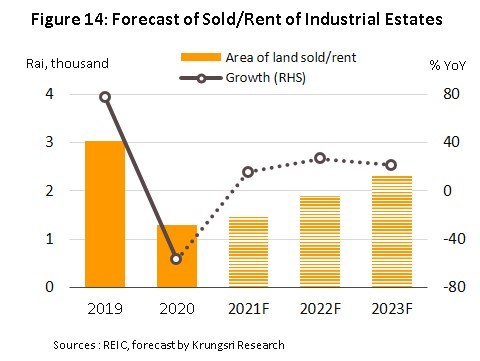

Following a contraction in the market in 2020, over the period 2021 to 2023, demand for space on industrial estates is expected to rise by an annual average of 20%, lifting the combined total of sales and leases to 1,500, 1,900 and then 2,300 rai in each of the next 3 years (Figure 14). Revenue from the provision of services and utilities will also rise over the same period, with this outlook supported by the following factors.

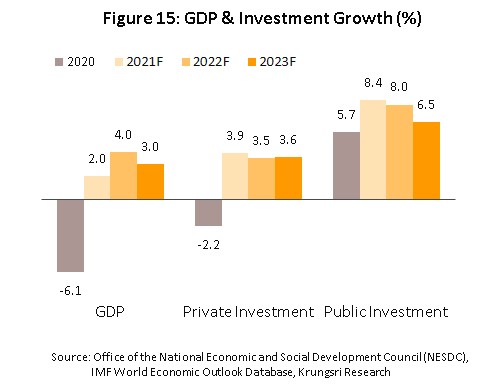

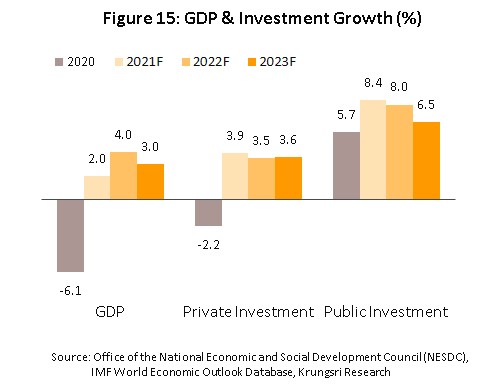

- The outlook will improve for the Thai economy and domestic investment over 2021-2023. Following a 6.1% fall in GDP in 2020, Krungsri Research sees Thailand managing growth of 2.0% in 2021, which will then accelerate to 4.0% in 2022 and 3.0% in 2023. Investment by both the public and private sectors will also strengthen over this time period (Figure 15), helped by the following.

- Continuing progress on the development of infrastructure will help to more fully integrate transportation networks, lowering travel and transport times while increasing the ease and convenience of using transport services.

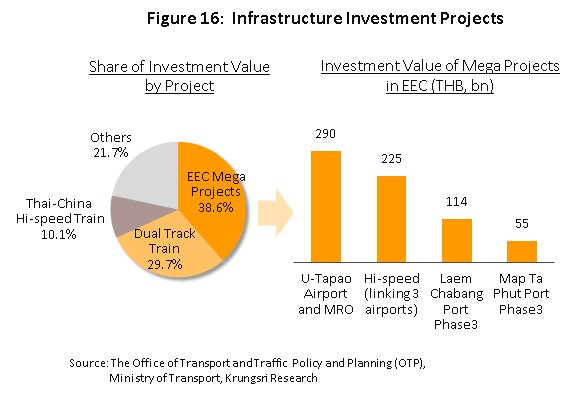

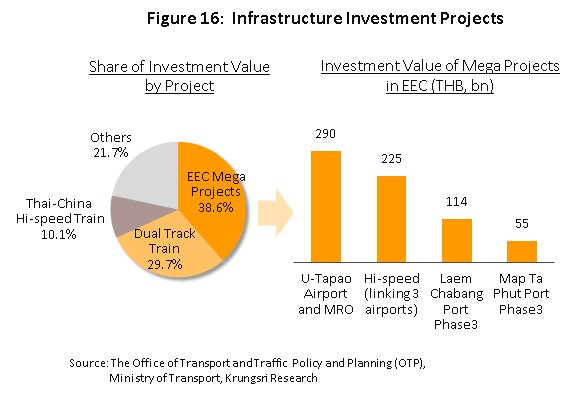

- The EEC has a strategically important role to play in connecting and integrating investment in the area, and this will then be an important factor supporting the growth potential of industrial estates in the eastern region. Given this, projects connected to the EEC will be the most important undertaken by the public-sector, and these will account for 38.6% of the value of all government spending on construction (Figure 16). Because of this strategic importance, many megaprojects that support the development of the EEC will see work commence in 2021, including: (i) the first phase (Suvarnabhumi-U-Taphao) of the high-speed rail-link connecting the area’s three airports (Don Muang, Suvarnabhumi and U-Taphao); (ii) phase 3 of the Map Ta Phut and Laem Chabang Port development, scheduled for construction and land reclamation work; and (iii) the construction of a new passenger terminal at U-Taphao. Spending on these 3 projects will come to over THB 60 billion in 2021 from a total cost of more than THB 680 billion. In addition, the government has also approved plans to expand the scope of some existing projects, including the development of Laem Chabang Port so that it better connects the EEC to the south of Thailand and neighboring countries, thus helping to establish Thailand as an ASEAN transportation hub. As part of this, new projects will be undertaken, such as the building of a dry port. This should be completed in 2023-2024, and the whole development will then help to extend transportation links to other regions by means of a multimodal transport network.

- An improving economic outlook is feeding a strengthening of sentiment among overseas investors, while plans to begin the reopening of the country to tourist and business arrivals (for example through special tourist visas, the Thailand Elite Card and the ‘tourism sandbox’) will help to boost business travel, for example for those inspecting construction sites, engaging in business negotiations and signing contracts. Indeed, being able to make a physical inspection of a proposed business site is considered an important factor in facilitating investment decisions since investors need to be able to make an informed judgement about the entire environment surrounding the proposed site. This is then one reason why, in the first quarter of this year, applications for BOI investment support rose 80.1% YoY to a value of THB 120 billion, 52% of which (or investments worth THB 64 billion) was for projects located in the EEC.

- Foreign investors are also increasingly moving production facilities to Thailand, or expanding these for those already in the country. This includes players from China (especially manufacturers of electronics, electronics parts and IT products), Japan (office equipment and air conditioners) and Malaysia (hard disks) (source: The Center for International Trade Studies, University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce). These organizations are being attracted to Thailand by a combination of supply chain disruption caused by the long rumbling US-China trade conflict and the desire to establish more resilient supply chains that can withstand unforeseen shocks. In addition, Thailand enjoys advantages in terms of its geographical position as a manufacturing region at the heart of the ASEAN zone, as a center of regional trade, and as a logistics hub linked by road and rail to the wider region. These factors thus all help to make the country an attractive investment target.

- Government measures to stimulate investment, including in particular extending special tax privileges and reforming the regulatory environment to make it more business-friendly, should help to attract greater interest from foreign companies. These policies have included BOI support schemes that waive corporation tax for 13 years (up from the earlier 8-year waiver) and reduce companies’ tax burden by 50% for a further 5 years, while other measures that aim to attract investors by ameliorating the impacts of COVID-19 include extending the window for making tax payments and slashing land and building taxes by 90% for the 2021 financial year.

In the coming period, operators of industrial estates will tend to reduce their dependence on revenue from sales and leases of land, which tends to be influenced somewhat heavily by the broader economic conditions, thus exposing company revenue to a degree of risk. Instead, players will increase the proportion of revenue that comes from charges for services and the provision of utilities (e.g., generating and distributing electricity and processing waste water) since this is a source of revenue that is both recuring and relatively stable. In terms of investments, operators plan to move forward with the development of ‘smart parks’ that are fully fitted out with modern production technology, transportation and communications equipment and networks, and power systems, as well as developing more environmentally friendly industrial estates that are able to support future industries and that will be able to compete better against industrial space located outside industrial parks and estates. Players are also likely to become increasingly interested in investing in external industries that support growth in demand for industrial estates, especially in modern high-tech industries such as digital platforms. This will be because this will encourage manufacturers located on industrial estates to increase their uptake of digital technology (i.e., of robotics and automation systems) as they try to increase the efficiency of their operations and raise their competitiveness.

In some parts of the country, interest in investing in new industrial estates is undermined by the sluggish progress on implementing government policy. For example, the development of special economic zones in 10 provinces[3] has encountered problems with competitive bidding, which has repeatedly failed, with investors having abandoned their contracts when it transpired that the benefits, and the conditions under which these are granted, are not a good match for investor requirements. In addition, in many parts of the country, the development or upgrade of infrastructure is still insufficient, which then further weighs on investor interest. In response to these problems, the government is considering a new approach that will see these developments repackaged as an ‘economic corridor’ under the EEC model. The Policy Committee on Special Economic Zone Development sets a plan to encourage four special economic zones in four regions of Thailand (Table 3). Under the initiated plan, the NESDC is currently studying targets of development, development guidelines, and administration and management on Special Economic Corridors. Afterward, the BOI will propose privileges for investments in targeted industries in each area (source: Krungthep Turakij, 28 May 2021). However, it will be some time before it becomes possible to see clear signs of a change in investor sentiment, while in the meantime, Thailand’s neighbors may become more attractive investment targets than Thailand itself; in these countries, more favorable access to manufacturing inputs and more attractive labor markets may mean that investors in labor intensive industries put their money into developing industrial estates in these countries, rather than in Thailand.

Krungsri Research view

Over the three years from 2021 to 2023, the business conditions for industrial estates will tend to revive and demand for industrial land to purchase or rent will rise with a rebound in the economy and an uptick in private-sector investment. Operators of industrial estates will put into effect plans to invest in ‘smart park’ that are fully equipped with a wide range of modern machinery and services, as well as investing in environmentally-friendly developments that will be suitable sites for the location of future industries. Revenue streams will also be restructured as players move to a greater emphasis on revenue from stable and recurring sources (e.g., the supply of electricity, water and other utilities, and receipts from rents). However, revenue will vary from area to area, and so the outlook for the main regions is given below.

- Industrial estates in the eastern region: Revenue will tend to rise at a sharper rate for operators in the eastern region than for those in other areas, with this driven by strong growth in demand for land to purchase or rent. The market will be boosted by government spending on infrastructure construction that will support the development of the EEC (in the three provinces of Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao). This will then serve to attract greater interest from domestic and international investors, especially for those active in industries that are targeted for support by the Thai government. However, in the coming period, the supply of new space on industrial estates (both new developments and extensions to existing ones) will tend to be limited due to steadily rising land prices and the increasing difficulty that developers are having in finding suitable new sites.

- Industrial estates in the central region: Revenue will tend to grow solidly for players in this group, especially from rents and charges for the supply of services and utilities. However, growth in the supply of space on industrial estates will again be limited, though in this case this will arise from the concentration of suitable sites in Bangkok, Samut Prakan, Ayutthaya and Saraburi, which have advantages over other provinces due to their proximity to the area’s transportations networks.

- Industrial estates in other regions: Revenue will tend to remain flat due to low demand in these areas. Local markets for industrial space continue to wait for more concrete government action, especially for progress on infrastructure projects in the special economic zones and in nearby areas, which would connect transportation networks to industrial estates. However, in the absence of this, growth in the market for industrial estates outside the central and eastern regions will be relatively sluggish.

[1]The principal differences between on the one hand, industrial estates and on the other, industrial parks and zones, are that: (i) foreign companies may purchase land on industrial estates without the approval of the BOI, but may not do so in the case of industrial parks and zones; and (ii) the IEAT acts on behalf of businesses on industrial estates as the certifier and provider of a variety of services, such as issuing permits to build and to operate factories, and thanks to its being a government agency, it is able to have applications to the Department of Industrial Works for these processed more smoothly and more rapidly than can private sector operators. In the case of industrial parks and zones, conversely, the operator of the park/zone will itself be responsible for handling these services on behalf of the lessees or purchasers.

[2]The twelve targeted industries are: (i) next-generation automotive industries; (ii) intelligent electronics; (iii) high-value and medical tourism; (iv) advanced agriculture and biotechnology; (v) food for the future; (vi) automation and robotics; (vii) aviation and logistics; (viii) biofuels and biochemicals; (ix) digital industries; (x) medical industries and comprehensive healthcare; (xi) defense industries; and (xii) education and human resource development.

[3]Phase 1: Tak (Mae Sot), Songkhla, Mukdahan, Sa Kaew, and Trat provinces. Phase 2: Chiang Rai, Kanchanaburi, Nong Khai, Nakhon Phanom and Narathiwat provinces.

.webp.aspx)