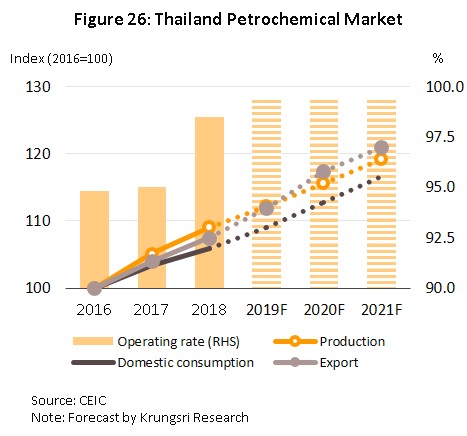

During the next three years (2019-2021), the petrochemical sector is forecast to see satisfactory levels of growth thanks to rising demand on domestic and export markets. The outlook is thus for consumption of petrochemical products within Thailand to grow by 2.9-3.5% annually, while the volume of exports should rise by 3.0-5.0% per year, and given this, capacity utilization will increase and may even touch 99%.

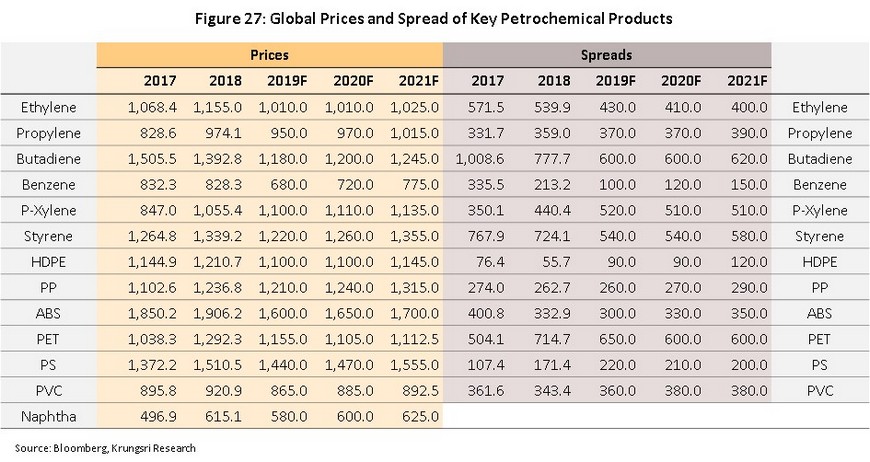

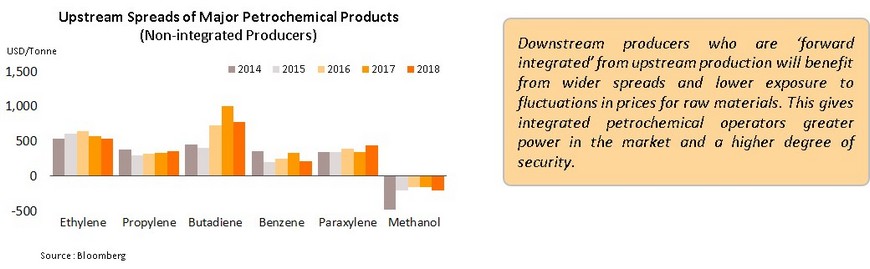

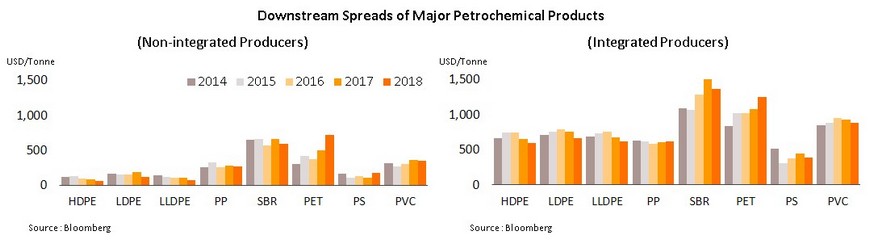

Net margins for players in the petrochemical sector, however, will tend to fall as spreads tighten on a combination of a supply glut of some products and the rising cost of raw materials.

Overview

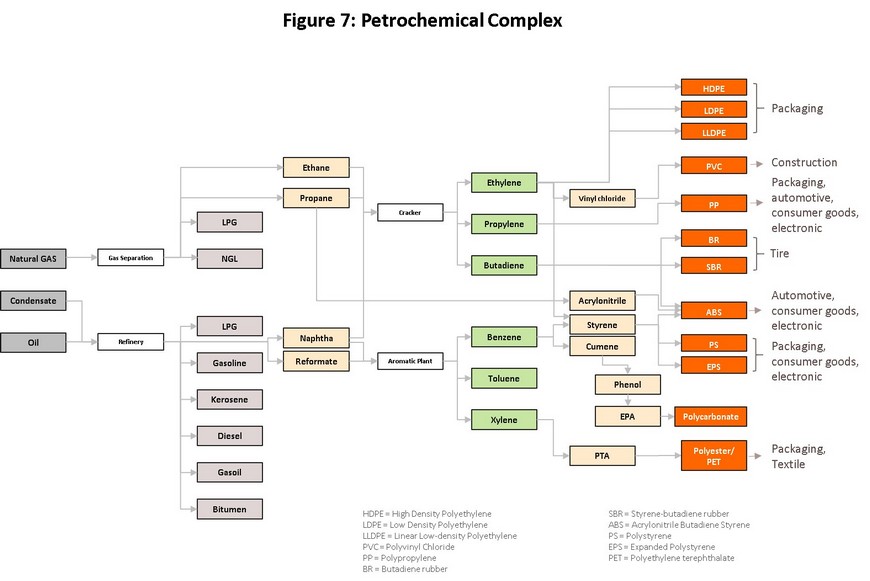

The production of petrochemicals entails the setting up of large-scale operations and the use of many complicated and tightly inter-connected industrial processes. As such, establishing petrochemical facilities involves investment in capital intensive ‘petrochemical complexes’ that are dependent on the use of advanced technologies. In addition, sites that host these complexes also need to have ready access to a wide range of industrial-scale utilities and so returns on investment in the sector are made over relatively lengthy timescales.

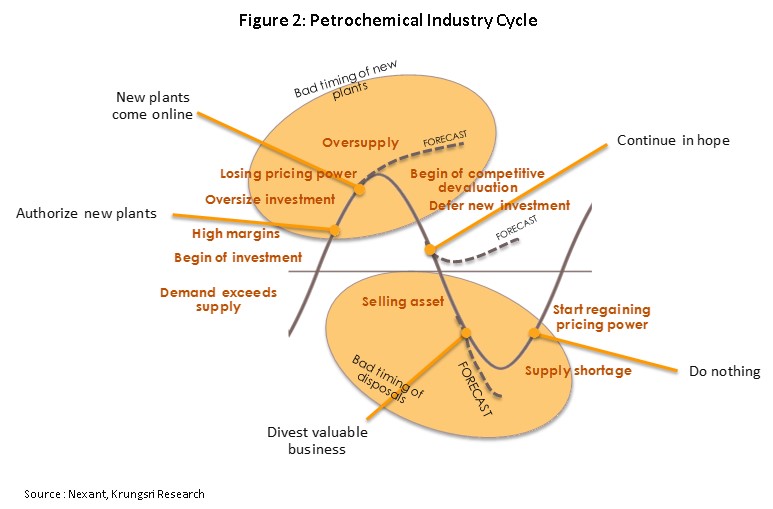

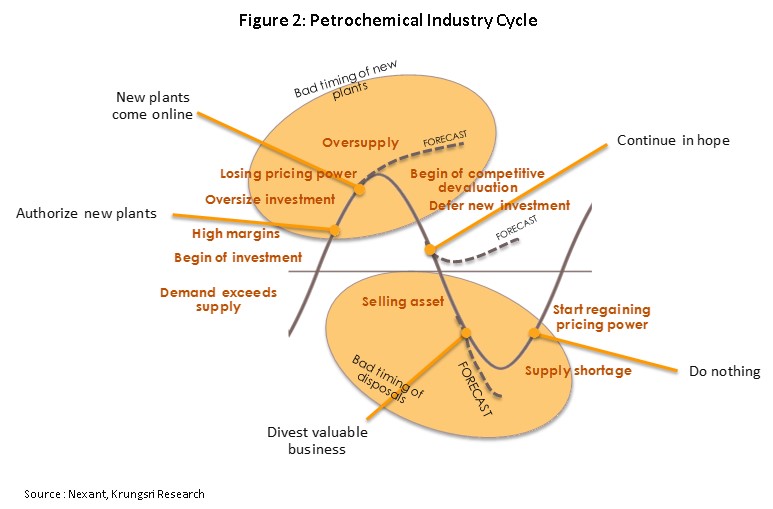

The petrochemical sector and the prices of petrochemical products move in a cyclical fashion, driven by the fact that the desire to exploit economies of scale tends to encourage large-scale investments as a way of meeting anticipated future demand. Decisions to invest in new facilities or to expand existing ones are usually made when the prices for petrochemicals are high, and this would normally be when an expanding economy is feeding rising demand for these products, or when supply shortages are being felt. However, construction of facilities can take anywhere from three to seven years and this extended lead time may cause oversized investments to be made. If, over these years, actual demand has failed to keep pace with projections, the market for petrochemicals will then be oversupplied and prices for products will tend to be depressed. The history of these cycles indicates that globally, they normally play out over a period of six to nine years but changes in the world economy also affect the petrochemical sector on both the supply and demand sides of the equation and more recently, it has been harder to identify cyclical movements that have occurred in the sector at the global scale.

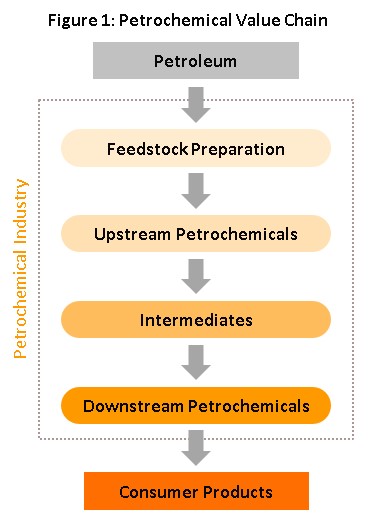

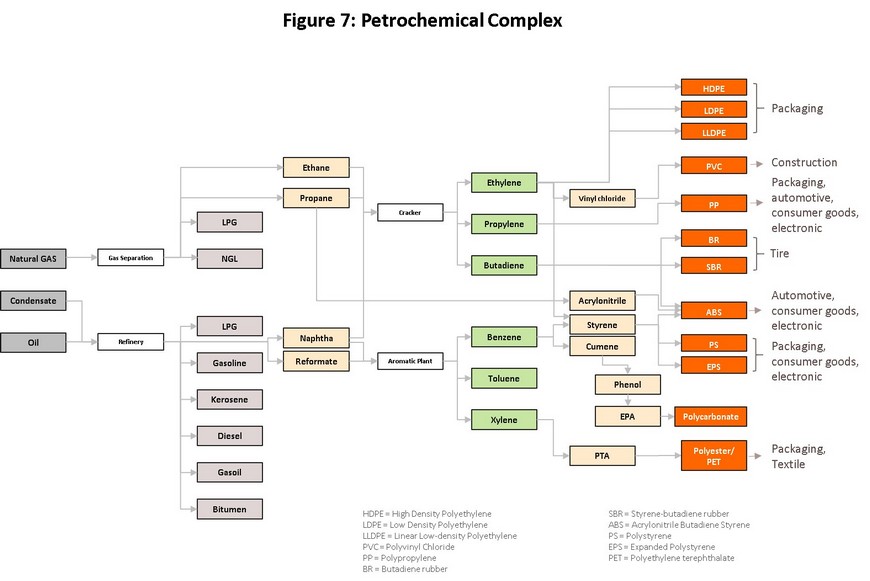

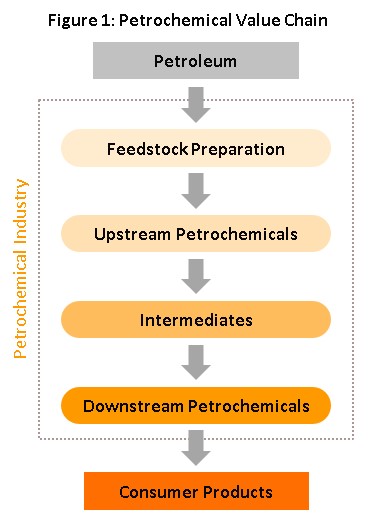

Investments in large global petrochemical complexes are typically connected to the oil sector as it uses petroleum products as key inputs, while petrochemical outputs may themselves also be bound for use as feedstocks or as primary ingredients in a wide variety of yet more industrial processes. The manufacture of petrochemicals can be divided into four main stages:

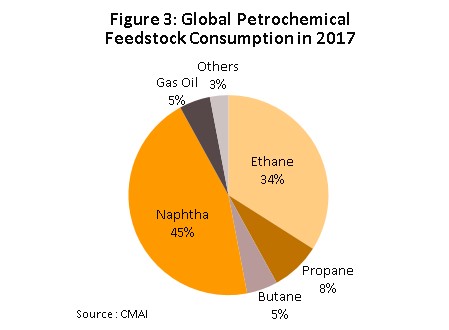

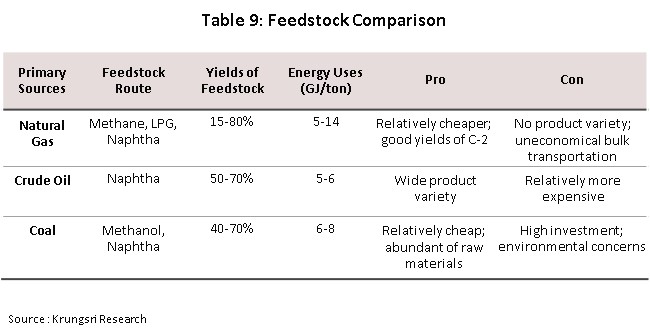

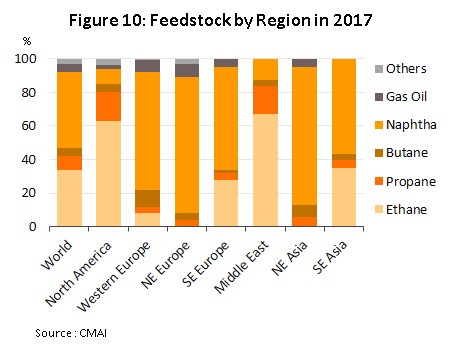

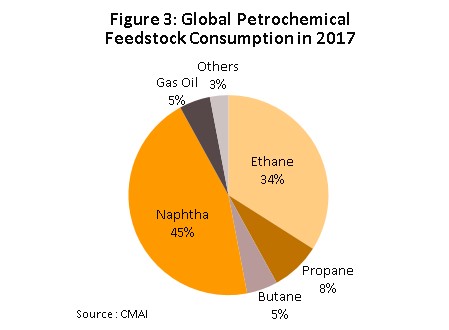

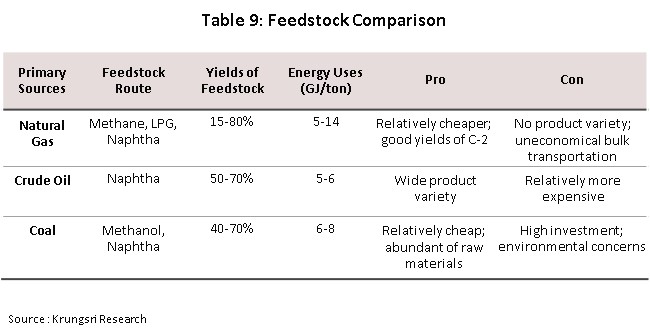

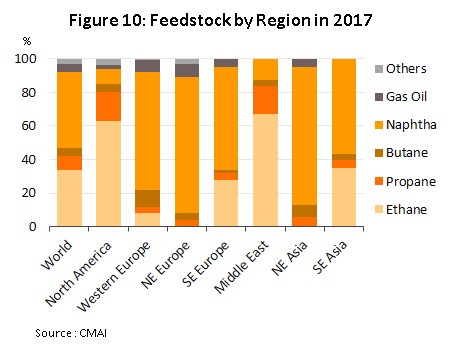

Stage 1: Manufacturers of feedstocks typically use products from the petroleum sector, including natural gas, condensates (a product of gas distillation), and naphtha (from the distillation of crude oil). Over half of petrochemical production capacity uses naphtha as its feedstock and this is especially common in facilities in Asia and Europe. In North America and the Middle East, by contrast, gas is used as the feedstock of choice because these areas are particularly rich in natural gas deposits. In addition, recent technological developments are allowing organic products such as sugarcane, cassava and palm to be used as raw materials in the production of bioplastics and investment in these areas will expand in the future (Figure 3).

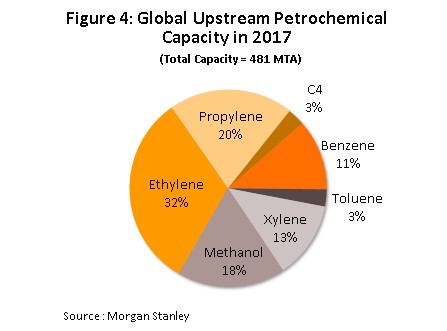

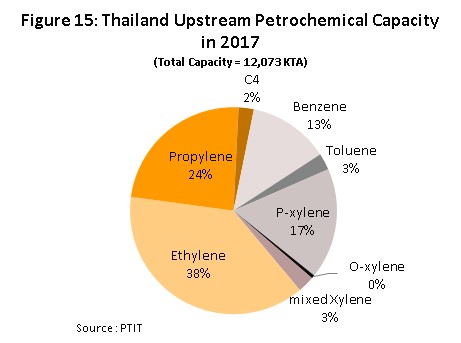

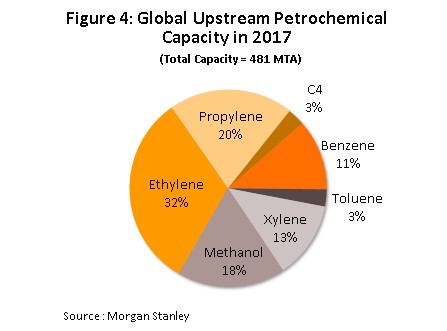

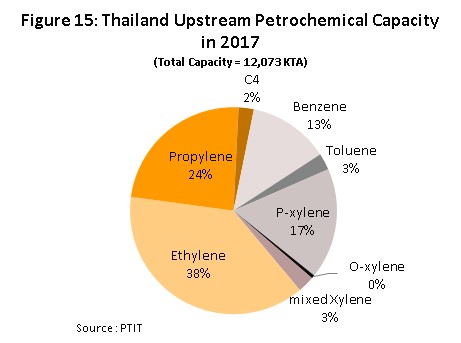

Stage 2: Upstream petrochemical industries take feedstocks and use them to produce precursor or preliminary petrochemical products. These may be divided into two groups, according to their molecular structure: (i) the olefins, which include methane, ethylene, propylene and other chemicals, and which have a base structure formed from four carbon atoms (so-called ‘mixed C4’ chemicals); and (ii) the aromatics, which include benzene, toluene and xylene, and which are used as inputs in the manufacture of other petrochemical products.

Stage 3: Intermediate petrochemical industries consume products originating in the upstream sector, including both olefins and aromatics, which are combined to produce intermediate products, some important examples of which include vinyl chloride and styrene. These are then used by downstream sector.

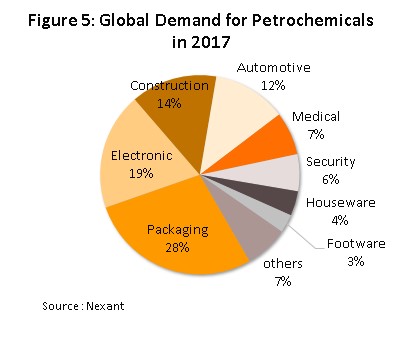

Stage 4. Downstream petrochemical industries take upstream and intermediate products and use these to make final products for use in related sectors (Figure 5). Products originating in the downstream petrochemical industry can be divided into 4 groups:

- Plastic resins are the most commonly used products in industries that are downstream from the petrochemical sector, these including packaging, automotive manufacture, building materials, and consumer goods. The most important chemical products used in these and other industries include polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polystyrene (PS).

- Synthetic fibers, for example polyester and polyamide or nylon fiber, are consumed by several sectors, including textiles and packaging.

- Synthetic rubber/elastomers are used in the manufacture of automotive parts, tires, and consumer goods. Examples include styrene butadiene (SBR) and butadiene (BR).

- Synthetic coatings and adhesive materials, which include polycarbonate and polyvinyl acetate, are used in construction and a variety of other industries.

The selection of different feedstocks for use in production is a decision made by individual operators and is determined by the nature of the products to be manufactured because each feedstock has a different hydrocarbon composition and will produce different petrochemical outputs. For example, using natural gas to produce ethylene returns approximately 80% ethylene and 20% other products, whereas using naphtha returns only 30% ethylene and 70% other products (Figure 8).

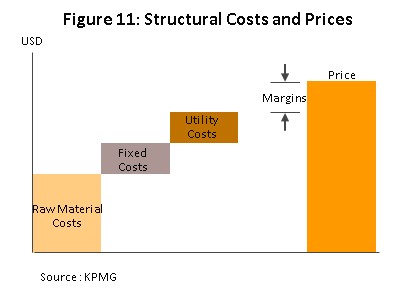

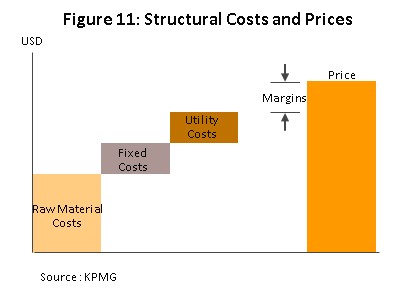

The cost structure of the sector is such that feedstocks comprise around 60-70% of the total, power and transport account for another 15-20% and the remaining 15-20% are attributable to fixed costs. Overall, expenses are thus largely dependent on the price of petrochemicals, making this a cost-based industry and producers who are able to keep these under control will gain competitive advantage. More specifically, production overheads, or the cash costs, will depend on the type of feedstock used, the production technologies deployed, and access to feedstocks. Feedstock management is therefore an important factor in determining costs, and locating production facilities in sites with easy access to raw materials and to markets will reduce transportation overheads and add further to a player’s competitive advantage.

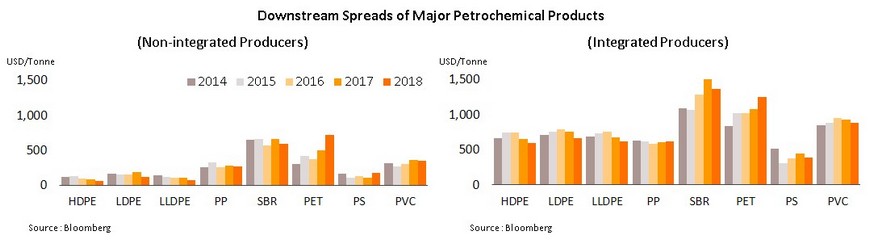

In addition, the ability to manage complex investments is another important factor in maintaining successful business operations because complex investments allow manufacturers to better manage costs and production, to reduce exposure to risks arising from fluctuations in the price of products, and to plan production better. Product flexibility also permits manufacturers to more easily adjust production to meet changing demand, while large-scale operations open the way for manufacturers to benefit from economies of scale, reducing the marginal costs of production.

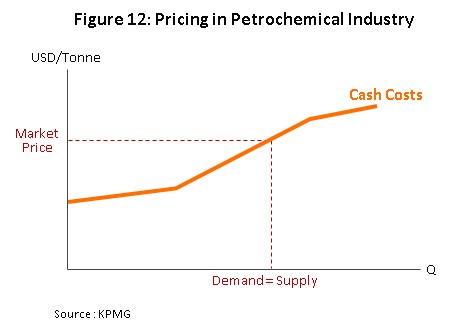

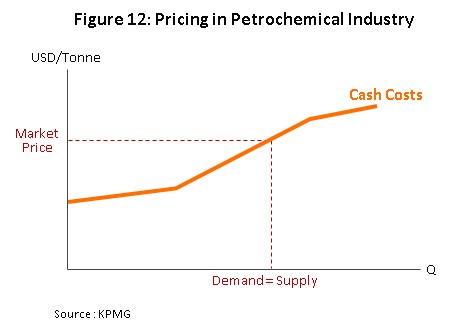

The petrochemical market is large and globally interconnected, and prices are therefore set by a combination of supply and demand on global exchanges and production costs. Global prices are determined by what is called ‘laggard-driven pricing’, that is to say, the market price is set by the cost of producing the last unit consumed and so when the cost of the feedstocks used in producing that last unit changes, this will have a direct effect on prices. In support of this, research shows that the prices of upstream and downstream petrochemical products are 70–85% and 40-70% correlated with the cost of feedstocks, respectively.

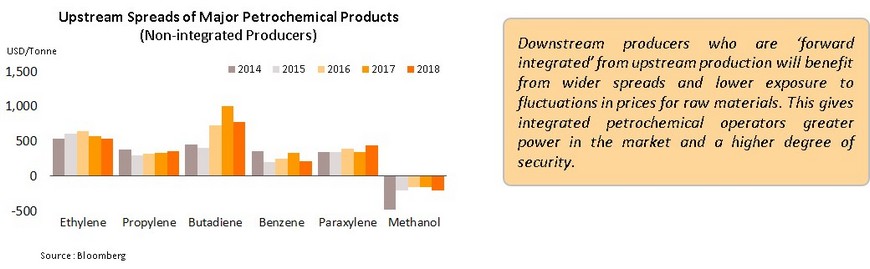

The ‘spread’ of a particular petrochemical product refers to the difference between product prices and the cost of raw materials, and this thus represents the gross profit margin for each product. However, because most downstream petrochemical industries have a product chain stretching from upstream products, through intermediate to downstream outputs, when calculating profits, the spread of all the products in the supply chain should be considered.

When considering the profitability of operators, the gross integrated margins (GIM) may be assessed. The GIM is calculated from the balance of the total value of petrochemical products less the total cost of production, and so depends on the spread of all the products manufactured, which will rise and fall according to the operator’s cash costs, and the capacity utilization. However, product mixes will vary for different production sites and for different operators and this makes assessing competitiveness through a direct comparison of GIMs somewhat difficult. Generally, cash costs are used instead as the preferred metric for assessing competitiveness and in particular, the cash costs for ethylene are used because, at 32% of the global total, it is the world’s most commonly produced upstream product, while also being used as a feedstock in a wide variety of processes.

The global petrochemical sector

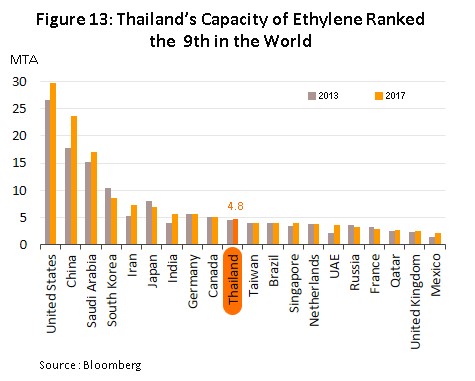

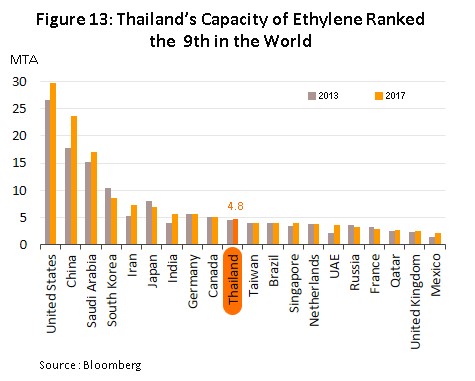

An assessment made by Information Handling Service (IHS) shows that in 2017, the global petrochemical sector had a market value of around USD 700 bn and it is expected that in a further five years, this value will exceed USD 1 trn. Globally, China is both the biggest producer and consumer of petrochemicals, being responsible for 29% of all production and 28% of all consumption, while the United States is the world’s single largest processor of ethylene, holding 18% of global production capacity (Figure 13).

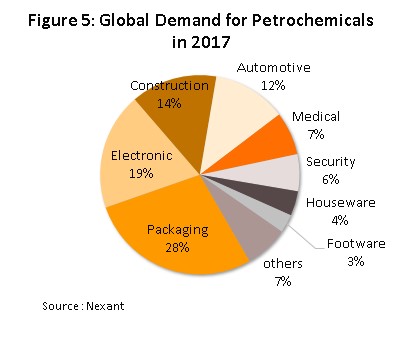

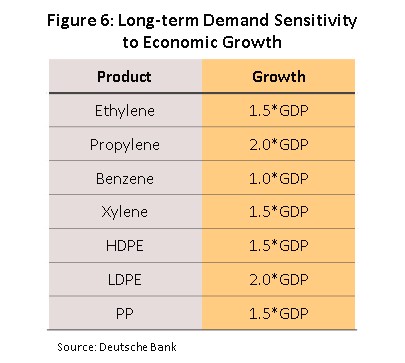

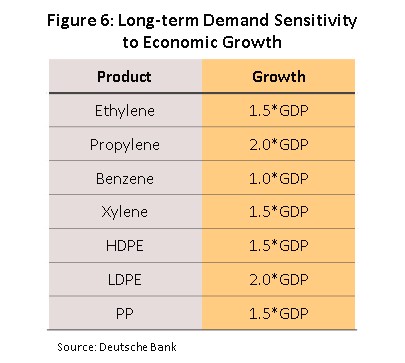

Worldwide, petrochemical products are used in packaging (28% of output), electronics (19%), construction (14%), automobile manufacture (12%) and a range of other related sectors (27%). Demand for petrochemical products typically increases at a rate 1-2 times growth in the economy generally.

The Thai petrochemical sector

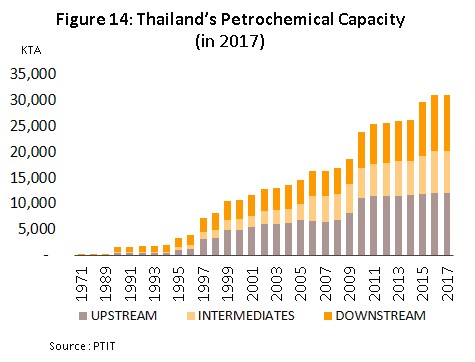

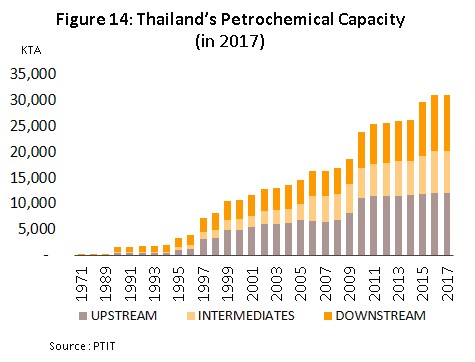

In 2017, the Thai petrochemical sector had a total production capacity of 32 million tonnes, making it the largest in the ASEAN region and the 16th largest in the world.

- Output was divided between upstream products (12 million tonnes), intermediate products (8 million tonnes), and downstream products (10.8 million tonnes).

- Output was divided between upstream products (12 million tonnes), intermediate products (8 million tonnes), and downstream products (10.8 million tonnes).

- Over 80% of Thai upstream and intermediate production is used within the country as inputs to further downstream processes, and as a result of the domestic production of a wide variety of industrial products, 45% of the sector’s downstream output is consumed within Thailand. The primary consumers of downstream products within Thailand are packaging (38% of the total), textiles (18%), automobile manufacture (12%), electronics (11%), and others (21%) and so demand from within the country is strong. The remaining 55% goes to export markets (largely in the form of plastic pellets, or nurdles), the most important of which are China (31%), Japan (10%), Indonesia (10%), Vietnam (9%) and India (8%).

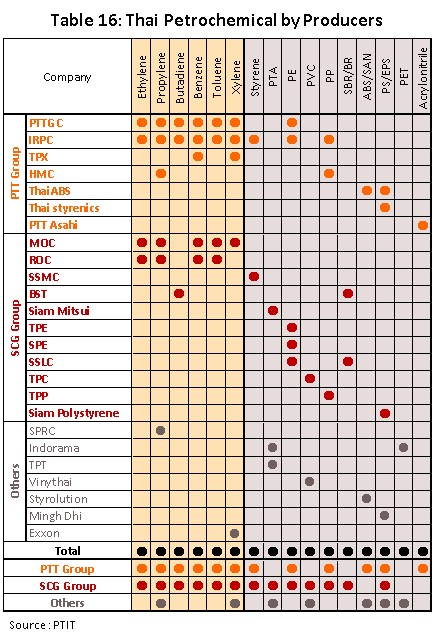

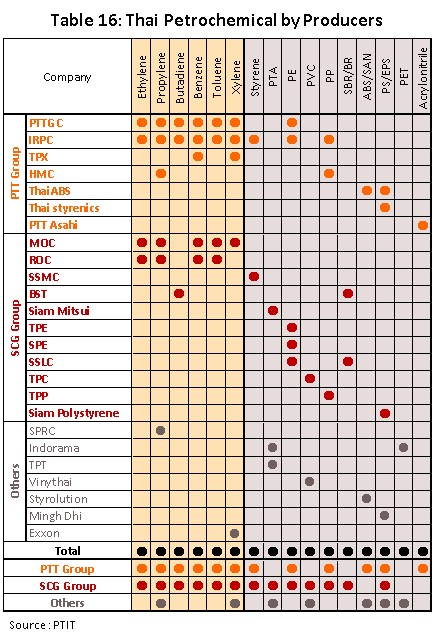

There are two major players in the domestic petrochemical sector: PTT, with a 54% market share, and SCG, with a 29% market share, and to gain manufacturing and marketing advantages, both have engaged in ongoing investment in related sectors in Thailand and in other countries. PTT are linked to upstream industries, including oil drilling, natural gas production, oil refining, and the production of a wide variety of petrochemical products. The SCG group, meanwhile, includes businesses in industries that are consumers of petrochemical inputs such as consumer goods and building materials. In addition to these two corporations, other businesses are active in the sector and these tend to focus on the production of intermediate and downstream goods. These businesses include both Thai companies, for example Vinythai, and international operators or joint ventures with foreign companies such as Indorama, Exxon, and MingDih.

and this is prompting changes in the domestic petrochemical sector. These changes include:

- Increasingly switching to the use of naphtha, a crude oil product, as a replacement feedstock for those which come from natural gas. This will have consequences for the upstream product mix, which will shift from its historical norms.

- Developing a greater range of new downstream products, especially higher value goods and at the same time, moving away from competition on price, all of which is in line with the third phase of the development plan for the sector for the years 2004-2018.

- Expanding production facilities in countries with access to supplies of raw materials and a sufficiently large domestic market. These countries include Indonesia, China and America. An example of this is PTT Global Chemical’s investment in the construction of a petrochemical complex in the United States that has been built in order to exploit the supply of cheap shale gas in the region.

Situation

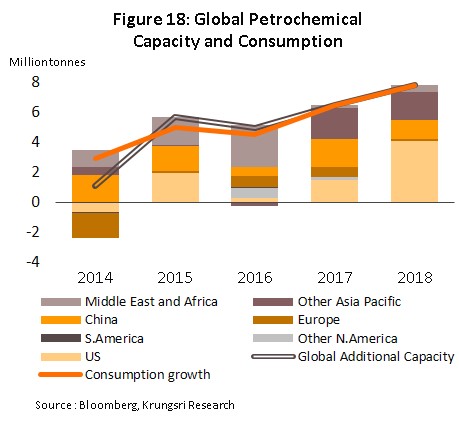

In 2018, the global economy strengthened and with this, per capita consumption of plastics increased. This then supported rising demand for petrochemical products, which increased by 4.3% in the year. However, while output grew, so did production capacity, which expanded by 4.2% and so overall, capacity utilization remained largely unchanged at 80.4%.

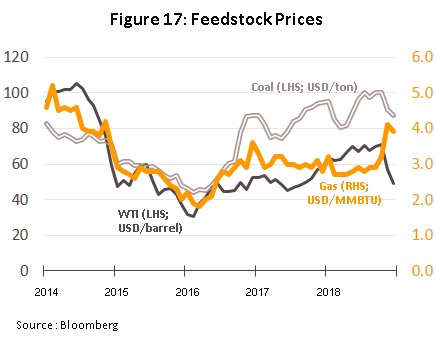

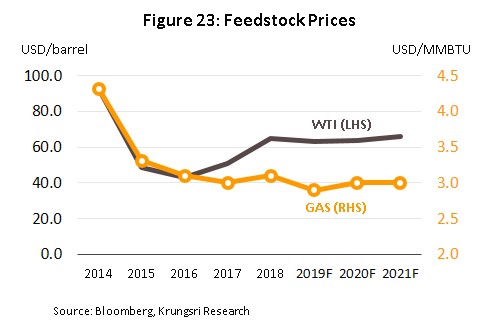

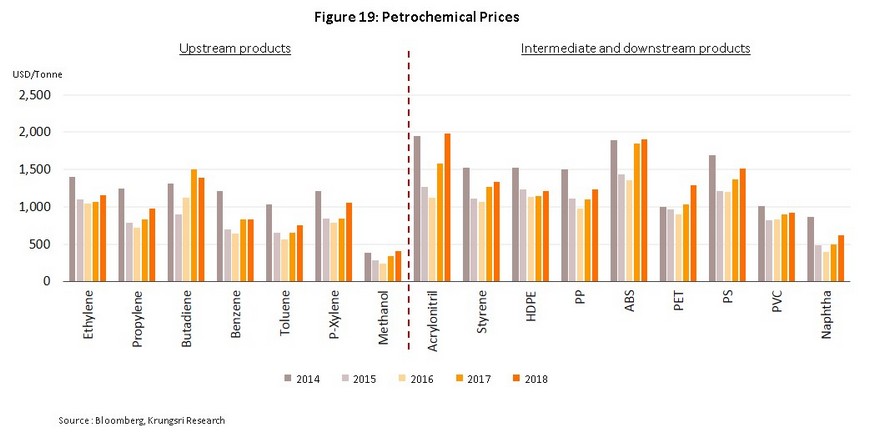

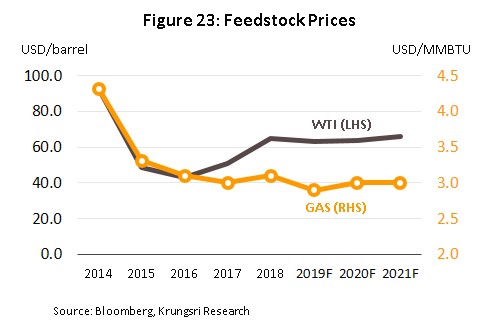

Feedstock prices rose through 2018 on a 27.1% increase in the cost of West Texas International (WTI) crude, which rose to an average of USD 64.9/bbl. This was driven by rising demand for petroleum products and the consequence for the petrochemical sector was to lift the cost of naphtha by 23.8% to an average of USD 615.1/tonne. Prices for natural gas rose at a slower rate, going from USD 3.0/MMBTU to USD 3.1/MMBTU in 2018, and this widening gap between prices for naphtha and natural gas led to feedstock advantages for players using gas as the primary input into their production processes.

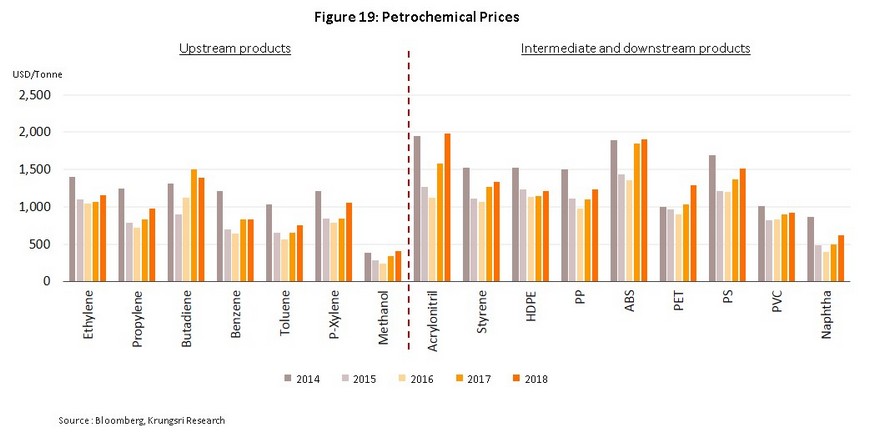

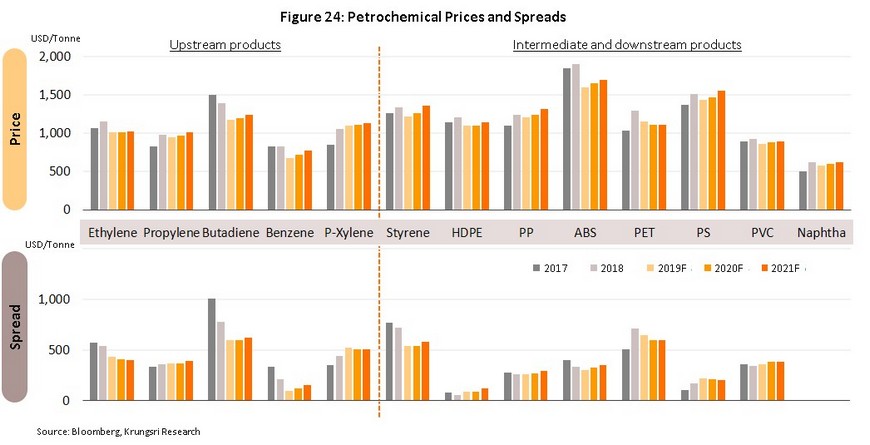

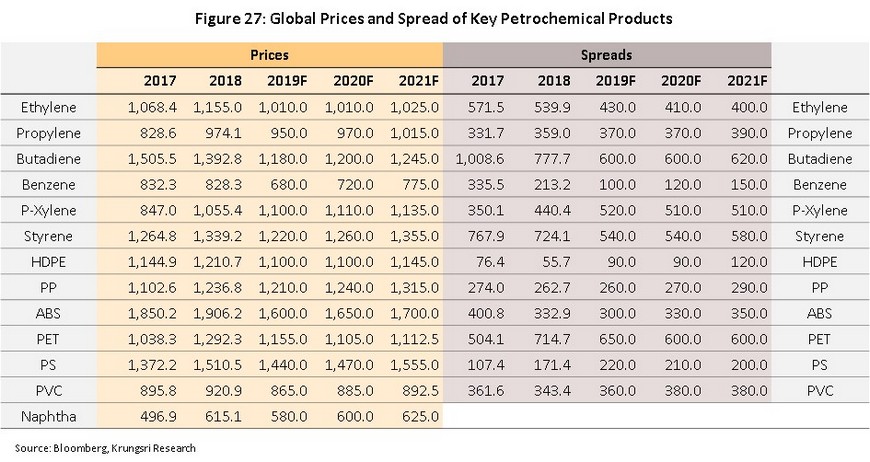

Rising costs for feedstocks then caused spreads for petrochemical products to tighten.

- Upstream petrochemicals

- Some ethylene markets showed signs of oversupply, which has been triggered by a gradual increase in new supply coming online, especially in the United States and the Middle East. This caused the ethylene spread to fall from USD 571.5/tonne in 2017 to USD 539.9/tonne in 2018, a fall of -5.5%.

- Likewise, the benzene market continued to suffer under a supply glut and in the year, the spread shrank by -36.5% YoY to USD 213.2/tonne.

- Downstream products

- The HDPE-ethylene spread fell from USD 76.4/tonne to USD 55.7/tonne on increases in supply outpacing those in demand.

- The polystyrene spread moved in the opposite direction and increasing demand lifted this from USD 107.4/tonne to USD 171.4/tonne

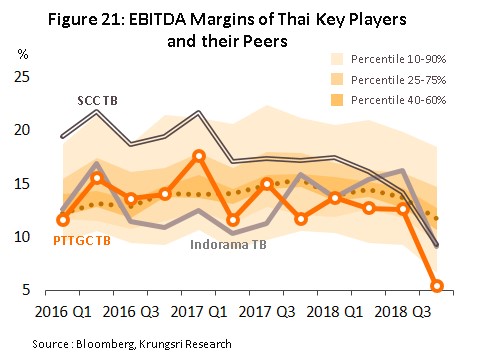

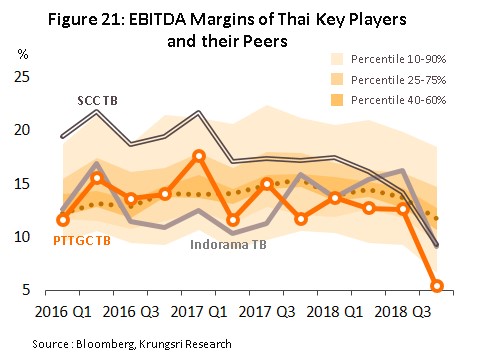

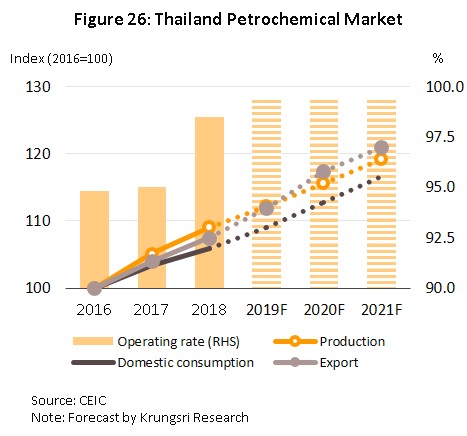

Greater demand from both domestic and export markets for Thai petrochemical products pushed capacity utilization to high levels and this then helped to keep turnover and profits for the Thai petrochemical sector at a satisfactory level in 2018, even though net profits weakened somewhat on narrowing spreads (Figure 21).

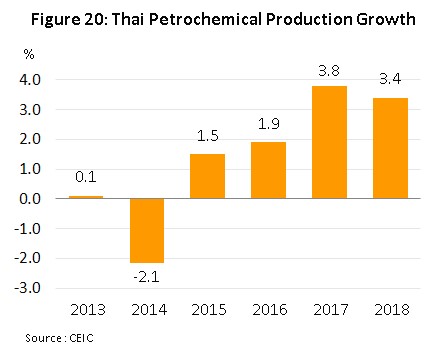

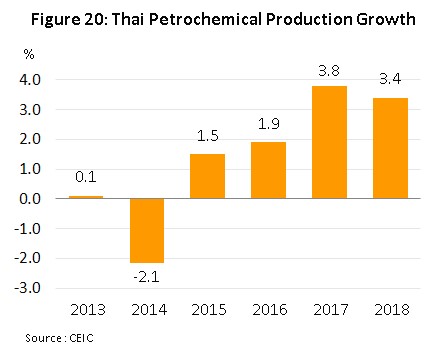

- Domestic consumption of petrochemical products rose by 2.4% YoY, with production benefiting from greater demand for consumer goods, and from the construction and agricultural sectors (Figure 20).

- Exports rose at the slightly higher rate of 3.4% YoY, driven by greater demand for plastics.

- Strengthening demand fed into a 3.8% increase in production, while a lack of any significant expansion in production capacity lifted the utilization rate for the sector from 95.0% to 98.5%.

Outlook

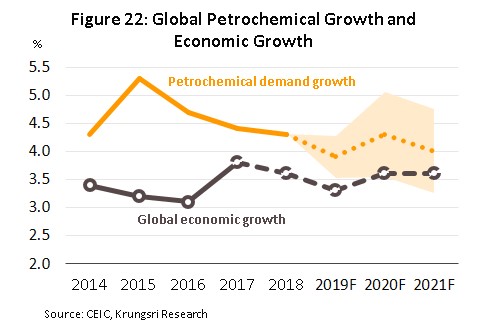

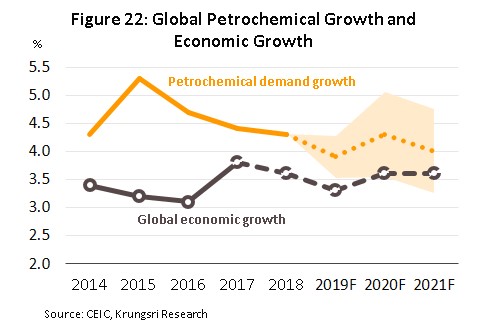

The world economy is forecast to grow by an average of 3.5% per year over the three years of 2019-2021 (source: IMF) (Figure 22). This will be a slight fall on 2018’s growth and this will lead to a similar sized fall in anticipated demand for petrochemical products. Krungsri Research thus believes that total demand for petrochemicals on global exchanges will record average annual growth rates of 4.2% between 2019 and 2021. However, through this same period of time, production capacity is forecast to grow by around 5.0% per year and so global production utilization should fall from 95.4% in 2018 to 93.8% in 2021.

The price of raw materials, both crude oil and natural gas, is expected to increase only slightly, if at all, and so operators using natural gas as a feedstock will maintain their feedstock advantages. Thus, the price of WTI is forecast to increase to USD 63/bbl, USD 64/bbl and USD 66/bbl in each of 2019, 2020 and 2021, while in the same years, the price of natural gas should run to USD 2.9/MMBTU, USD 3.0/MMBTU and USD 3.0/MMBTU. Beyond this, strengthening demand for gasoline will tend to incentivize refineries to switch from naphtha to gasoline production and because of this, naphtha prices are forecast to rise to USD 580/tonne, USD 600/tonne and USD 625/tonne in 2019, 2020 and 2021.

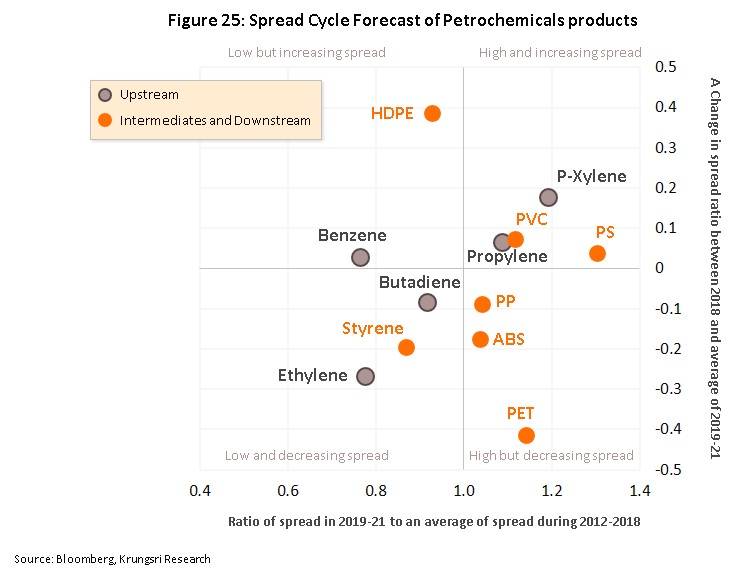

The prices for petrochemical products will tend to rise globally on a combination of demand pull and cost push factors, although an oversupply of many products will cause spreads to contract slightly, while in addition, new supply will steadily come onto the market over the next three years. The expected outcome of this for the spreads of the main products is thus given below.

- Spreads that are high and are expected to grow: P-xylene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polystyrene (PS) and propylene.

- Spreads that are high but are expected to fall: Polypropylene (PP), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

- Spreads that are low and are expected to fall: Butadiene, styrene and ethylene.

- Spreads that are low but expected to grow: Polyethylene (PE) and benzene.

Forecasts for important products 2018-2020

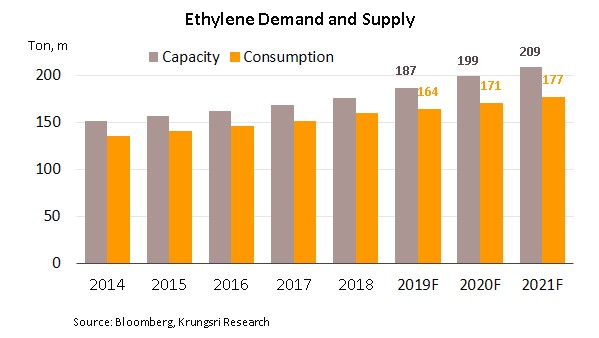

Ethylene

Ethylene is the sector’s most important upstream product and annual production runs to over 160 million tonnes, or approximately a quarter of combined global petrochemical output. The major ethylene producing regions are East Asia (24%), North America (22%) and the Middle East (19%). Around 60% of output is used in the production of polyethylene (PE), an important input to the packing industry, though in addition, ethylene is used to make ethylene oxide, ethylene dichloride and ethyl-benzene, which are used in packaging as well as in construction.

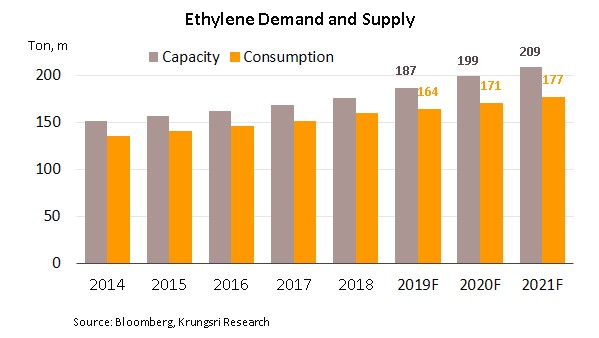

Demand for ethylene worldwide is expected to rise by 3-4% annually over the next 3 years, although the expansion in production capacity is forecast to run ahead of this, at 4-5% per year. The majority of new capacity will be in regions that enjoy advantages with regard to their access to inputs, that is, countries in the Middle East, North America and China, and this will be one factor in holding back world ethylene cash costs. Ethylene producers will therefore have difficulty raising their prices to offset the higher cost of feedstocks and so the ethylene-naphtha spread will tend to weaken.

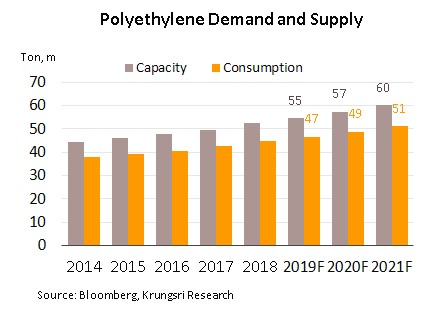

Polyethylene: PE

This is made from ethylene and is the most commonly produced type of plastic pellet. Around 70% of output is consumed by packaging industries.

Demand is forecast to rise annually by 3-4%, while production capacity should grow by 4-5% per year, and this difference will likely trigger a supply glut in the polyethylene market. However, the falling price of ethylene will help the polyethylene-ethylene spread to remain stable or possibly widen slightly.

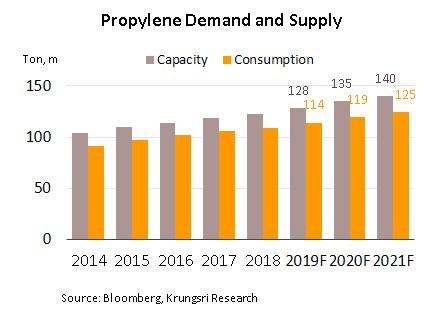

Propylene

After ethylene, propylene is the second most important petrochemical product. Propylene may be manufactured from naphtha, LPG or coal, and it is largely used to produce polypropylene (65% of output), a plastic for which automotive assembly is the major market, though polypropylene is also used as an input in the production of other industrial and consumer goods.

Demand is likely to rise by 4.0-5.0% per year, greater than the forecast expansion in production capacity in coal-to-olefin plants in China, which grew rapidly in 2017 and which is expected to continue to increase over the next two years. Despite this, though, the price of propylene will be put under pressure by ethylene price (an alternative petrochemical product) and this will keep the polypropylene spread stable in the region of USD 380/tonne over the next three years.

Benzene

Of all the aromatics, benzene is produced in the highest quantities. Benzene may be made from naphtha, and globally, around 63 million tonnes are manufactured annually. Roughly half of this is used as an input into the production of ethyl-benzene, which is then used to manufacture polystyrene, while a further 20% is consumed in the production of cumene, a petrochemical product that is sent for further processing in the packing, construction and consumer goods sectors.

The expectation is that for 2019-2021, annual growth will run to 3.0-3.5%, ahead of the forecast 1.8% annual expansion in production capacity. Spreads will, though, come under pressure from the current high level of production capacity and the rising price of naphtha.

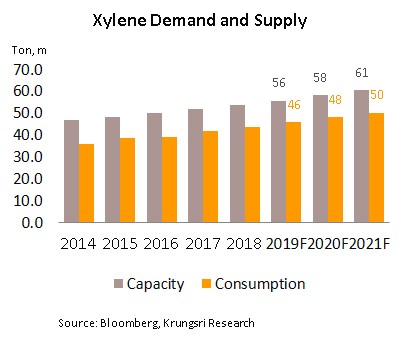

Xylene

Xylene (which can be produced from naphtha) is an important aromatic within the Thai petrochemical sector, and more than two-thirds of production originates in oil refineries. The majority of output is used in the production of polyester and PET, which is then bound for the packaging and textiles sectors.

Demand is likely to rise by 4.0-4.5% per annum over the next 3 years, while production capacity should grow by around 2% annually, and this will help the xylene spread to steadily widen.

Polystyrene (PS)

Polystyrene is a downstream aromatic. At present, global production capacity stands at around 11 million tonnes. Polystyrene is made from styrene monomer, and it is used in a number of industries, including electronics, packaging and construction materials.

3-4% annual growth in demand is forecast for the next 3 years, which will be somewhat higher than the anticipated 2.5% growth in production capacity. The supply glut of polystyrene will therefore likely start to clear, and the spread will rise to an average of USD 200/tonne.

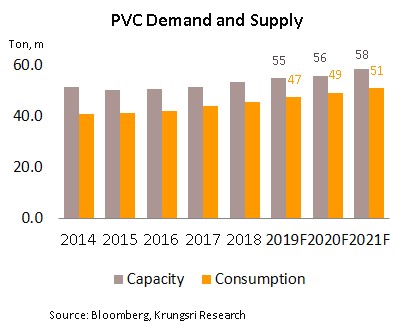

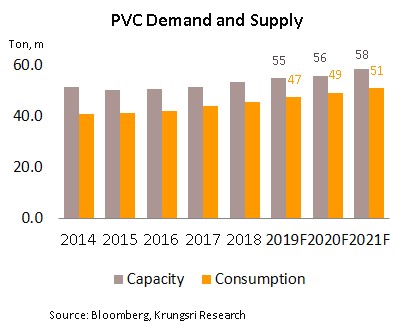

Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC)

PVC is a polymer of vinyl chloride monomer that is produced from ethylene and chloride. Global production capacity stands at around 50 million tonnes, and over 70% of output is used in the construction sector.

The forecast for demand for PVC is for growth of 3.5-4.5% annually, which will be above the 1% annual growth in production capacity. PVC spreads are thus forecast to widen.

As regards the domestic market for petrochemicals, growth is expected to be steady and to run in line with that of the wider economy. Expansion in demand will also be supported by growth in the use of plastic packaging, and increasing consumption in the construction sector and in automobile assembly. Overall domestic consumption of petrochemical products is therefore forecast to increase by 2.9-3.5% per annum over the next three years, while exports are expected to grow at the higher rate of 3.0-5.0% per annum on rising per capita consumption of plastics in developing countries. This strengthening demand on domestic and export markets will lift production by 2.8-3.1% and push average capacity utilization to high levels, possibly as high as 99% in this period.

In light of this, the forecast is that players in the Thai petrochemical sector will be able to maintain satisfactory income and profit rates through the coming three years, but although the sector will be positively affected by steadily rising demand and high levels of capacity utilization, tightening spreads for many products will tend to reduce net profits.

Krungsri Research view

Although spreads will tend to tighten, the forecast is that steadily growing demand will allow players in the Thai petrochemical sector to maintain satisfactory levels of income. In addition, most Thai manufacturers also have a presence through the length of the supply chain from upstream to downstream production, as well as operating in other related industries, both within Thailand and overseas (especially in markets with strongly growing demand such as China, Indonesia, and the CLMV region), and this then helps in streamlining production planning.

However, despite this positive outlook, Thai players are exposed to risk in the form of access to feedstocks, since natural gas reserves in the Gulf of Thailand are almost exhausted. Operators will thus potentially face problems with securing access to feedstocks and, should these need to be imported, they will be likely to have to pay higher costs for both natural gas and crude oil. Against this background, margins will then weaken.

Another factor which may limit the growth of the sector in the future is the stance of major export markets, especially of China, Indonesia and Vietnam, which are emphasizing increasing self-reliance in petrochemical production. Thai producers may need to adjust their business strategies in light of these changes by engaging in joint partnerships with existing players in markets such as in Indonesia, which, for example, is seeing solid growth in demand for plastics and benefits from easy access to raw materials. In addition, as a means of reducing exposure to competition on price, producers should also attempt to move out of the commodity-grade market and up the value chain by producing more specialized products.

Over the medium- to long-term, some Thai producers may switch to the production of environmentally-friendly bio-plastics since Thailand has abundant domestic sources of biomass inputs such as cassava, palm and sugarcane, which can potentially be used as alternative feedstocks. These high added-value products are currently in vogue due to their ability to help reduce environmental problems and, as a further advantage, the Thai government is also promoting investment in this area by offering investors special tax privileges.

.webp.aspx)