EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Operators of mass transit systems will enjoy an improving outlook over 2024 to 2026 thanks to domestic economic growth and the positive effects of this on consumer purchasing power. At the same time, ongoing expansion to the metro network will help to stimulate greater private-sector investment in both residential and commercial property in areas newly served by the mass transit system, adding further to potential demand for travel services. Expansion in the network will also help to increase integration and connectivity across the system, making it a faster and more convenient option for those traveling into the city center from suburban areas. Concession holders will thus see income rise from fares, the management of commercial space, operations and management services, and maintenance of equipment and rolling stock. Nevertheless, energy costs are increasing, and recovery in purchasing power remains somewhat patchy. This may drag on profits.

Krungsri Research view

Mass transit service providers enjoy a considerable degree of business stability since their investments are made in joint ventures with the government in necessary public utility. In addition, mass transit concessions are typically awarded for lengthy periods (generally for 25 years or longer), while the conditions laid out in concession contracts for the division of returns typically ensure that private-sector partners are able to maintain profitability over the long-term.

-

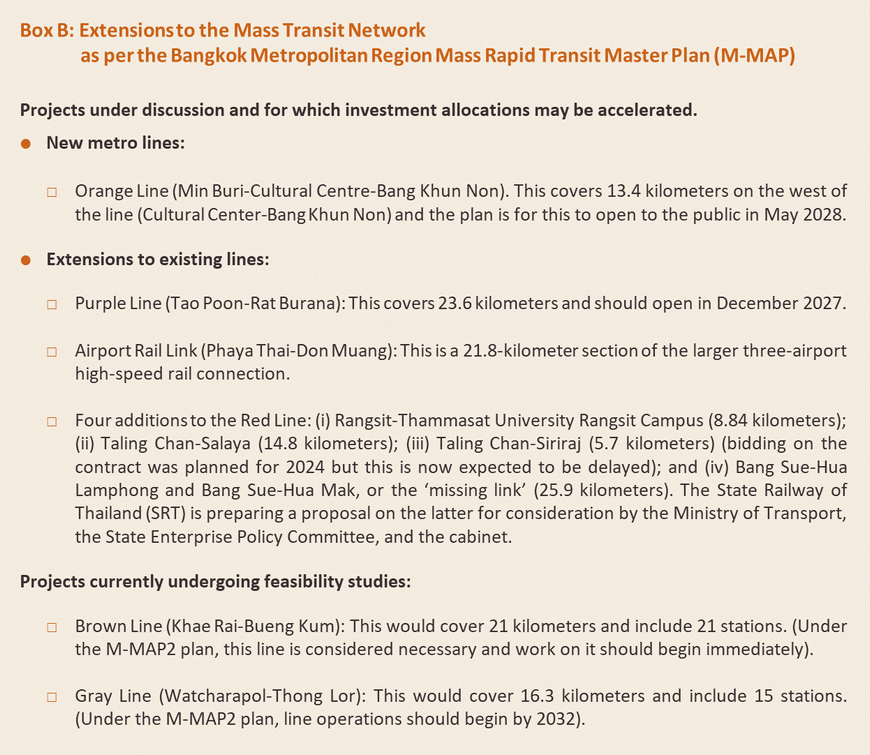

Over 2024 to 2026, growth in total track length and in the number of stations (currently standing at 192 stations) will boost the number of individuals served by the system, and thanks to this, operators’ income will rise. In addition, 2024 will be the first full year during which the Yellow and Pink lines offer commercial services, and so this will add further to corporate turnover. Beyond receipts from fares, operators will continue to generate income from services such as operation management, maintenance and repairs, as well as the rental of commercial space in stations and on rolling stock, and this will likely remain stable over the long term. hat includes measures to promote domestic tourism.

OVERVIEW

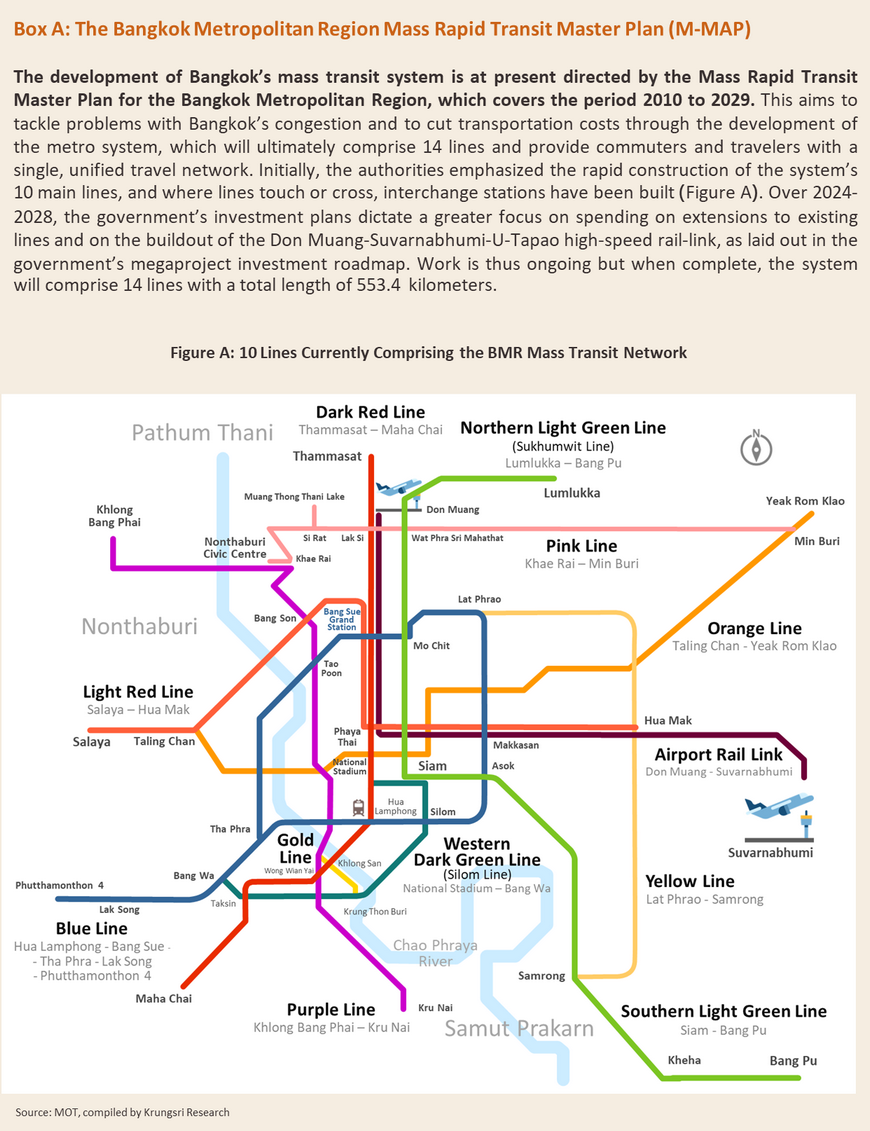

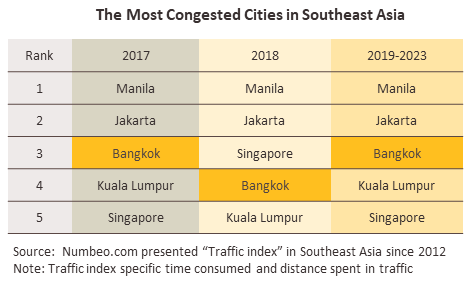

Mass rapid transit systems are a type of public rail transport1/ that has attracted ongoing spending by the Thai government as it looks to alleviate traffic congestion problems in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR)2/. Bangkok’s mass rapid transit system has thus developed as a public utility or public service provided by the government for commuters and travelers, who may choose between using the metro system or other forms of public transport that are available in the BMR, such as buses, shared taxis, minivans, the Bus Rapid Transit system, the suburban-urban rail system, and boat services running on rivers and canals.

Urban mass rapid transit systems use rolling stock that travels at mid to high speeds (80-160 kph) on tracks that are separated from other transport systems (i.e., there is no interaction between mass rapid transit systems and other transport modalities). Metros may run underground, at ground level, or on elevated platforms depending on the environment in which the system is constructed. Urban rail, light trams, monorail, and light and heavy capacity rail trains may all be used in such a system.

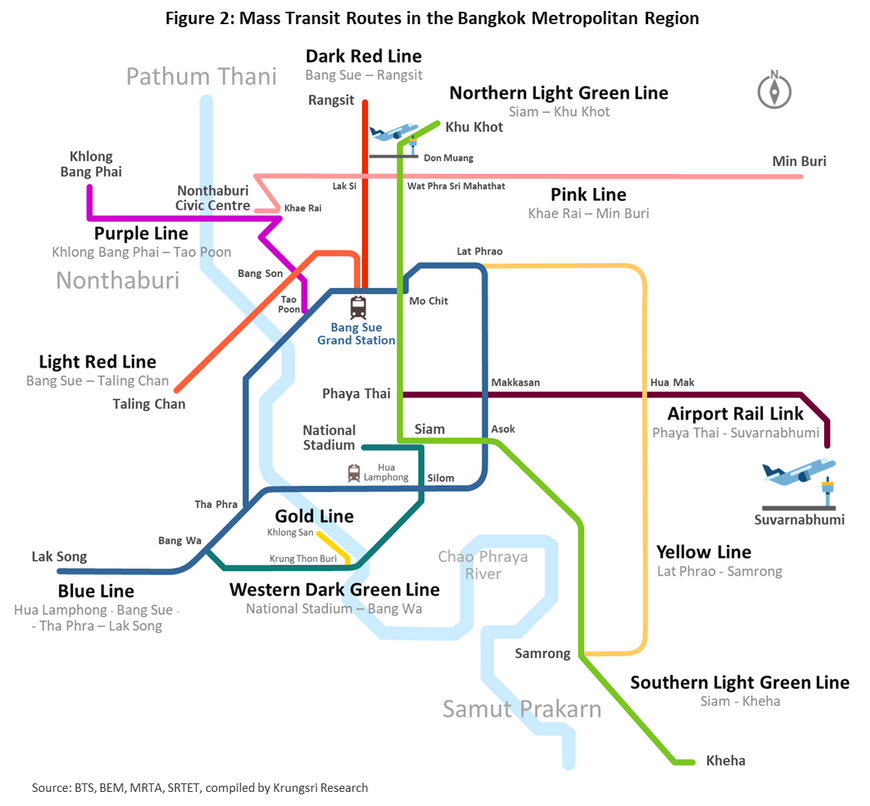

The first mass rapid transit line to begin operations in Bangkok was the Chalerm Prakiet Skytrain line, which is a heavy rail line that connects inner Bangkok with a wider area of central Bangkok3/. This opened for operations in 1999 and since then new lines have continued to be added or extended such that at present, the city’s rapid mass transit system comprises 10 lines, 192 stations, and 276.0 kilometers of track (Figure 2). The entire system is composed of the following:

1) Bangkok Mass Transit System (BTS) Green Line: This is a heavy rail line in the north and east of the area that connects the three provinces of Pathum Thani, Bangkok, and Samut Prakan. The line covers 70.1 kilometers and 63 stations (including the interchange station Siam), and is made up of 2 sub-lines.

-

The BTS Chaloem Phra Kiat or Sukhumvit line (the Light Green Line): This runs from Khu Khot in Pathum Thani to Samrong/Kheha over 54.25 kilometers and through 47 stations. The first section of the line (Mor Chit-On Nut) opened in 1999 and is operated by Bangkok Mass Transit System Plc (BTSC). The company was awarded a 30-year concession that runs from 1999 to 2029 by the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority (BMA) to run this section. Under this, the BTSC is required to install equipment, maintain and repair rolling stock, and manage operations across the line. The Mo Chit-Khu Khot and On Nut-Bearing-Samut Prakan extensions to the line were opened progressively over 2011 to 2020, with BTSC again in charge of operations, though this time it was brought in by Krungthep Thanakom (KT), a commercial operation owned by the BMA. This concession will run until 2042.

-

Silom (Dark Green Line): This runs from National stadium to Bang Wa, covers 14 kilometers, and passes through 13 stations. Operations began in 2004, with extensions to the original line then opening to the public between 2009 and 2013. BTSC won the right to operate this line and so is responsible for the installation and maintenance of equipment and of daily operations. The Silom Line connects to the Sukhumvit Line at Siam station, which with a 2019 pre-COVID daily average of 66,000 users, was the network’s busiest.

2) BTS Gold Line: This is a light railway built using a straddle-type monorail that runs for 2.7 kilometers from Krung Thonburi to Khlong San and Saphan Phut. This is an automatic system that operates without drivers and that passes through highly congested central areas. The line operates as a ‘feeder’ integrating rail transport with travelers moving by bus along nearby roads and by water along the Chao Phraya River. Phase one of Gold Line operations began in 2020 and connected Krung Thonburi to Khlong San through 3 stations and over 1.8 kilometers of track, and again, BTSC has been granted a 30-year concession to manage operations and maintenance. Phase two of the line will add 0.9 kilometers of track and one more station (Prajadhipok), but this is not yet operational.

3) Metropolitan Rapid Transit (MRT) lines: This network encompasses both a heavy rail mass transit system (the Blue and Purple lines) that circles the city to connect central parts of Bangkok, Thonburi, and Nonthaburi, and an automated light capacity monorail (the Yellow Line that links the north of Bangkok with Samut Prakan and the Pink Line that links the east of outer-Bangkok with Nonthaburi). In total, the MRT covers 135.9 kilometers of track and includes 107 stations. The MRT network is split into 4 core lines.

-

MRT Chalerm Ratchamongkhon Line (the Blue Line): This stretches for 48 kilometers from Hua Lamphong to Lak Song and passes through 38 stations. The Hua Lamphong-Bang Sue section was opened in 2004, though as time has gone by, the number of interchanges with other lines has increased. Thus, in 2017, this was linked with the Chalong Ratchadham Line (the Purple Line) at Tao Poon, with the Hua Lamphong-Lak Song section in 2019, and with the Bang Sue-Tha Phra section in 2020. The Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA) has granted the operating concession to Bangkok Expressway and Metro (BEM) for the 33 years between 2017 and 2040, and this works as a ‘through operation’, with the Blue and Purple lines running as part of a single network.

-

MRT Chalong Ratchadham (Purple Line): This covers 23 kilometers and 16 stations between Khlong Bang Phai and Tao Poon. Operations began in 2016 and then in 2017, services were extended with the construction of an interchange with the Blue Line, and connect with the Nakhon Withi (Light Red Line) at Bang Son station in 2021. The MRTA has awarded BEM a concession to operate and to maintain the line for the 30 years from 2016 to 2046.

-

MRT Yellow Line: This covers the 30.4 kilometers and 23 stations between Lat Phrao and Samrong. The line began operations in July 2023 and offers 3 connections with other lines: with the Blue Line at Lat Phrao, the Airport Rail Link at Hua Mak, and the Green Line at Samrong. The line is run and serviced by Eastern Bangkok Monorail (EBM), which has been granted a 30-year concession by the MRTA (from 2023 to 2053).

-

MRT Pink Line: The Pink Line runs between Khae Rai and Min Buri over 34.5 kilometers of track and through 30 stations. The line trial runs at the end of 2023 and connects with the Green Line at Wat Phra Sri Mahathat, the Red Line at Lak Si, and the Purple Line at the Nonthaburi Civic Centre. The line is run and serviced by Northern Bangkok Monorail (NBM), which has been granted a 30-year concession by the MRTA (from 2023 to 2053).

4) The Airport Rail Link (ARL), also called the AERA1 City Line: This heavy rail line connects Suvarnabhumi Airport with the City Air Terminal at Makkasan Station. Asia Era One has been given a 50-year concession (2019-2069) by the State Railway of Thailand and the Eastern Economic Corridor Office of Thailand to operate rail services and to develop commercial space within the station. The company is also building and managing the high-speed rail-link connecting the three airports of Don Muang, Suvarnabhumi, and U-Tapao, which will then connect with the existing Airport Rail Link. This is split into two sections.

-

Suvarnabhumi Airport City Line (SA): The section from Phaya Thai to Suvarnabhumi comprises 8 stations and 28.5 kilometers of track. This was opened to the public in 2010.

-

Suvarnabhumi Express Line (MAS): This covers the 25.7 kilometers from Makkasan to Suvarnabhumi but because this is an express service, there are no intermediate stations. The line offers a check-in counter and a system for transporting passengers’ baggage to Suvarnabhumi. The line was open for operations between 2010 and 2014 but at present it is inactive.

5) S.R.T. Mass Transit Commuter Train (Red Line): This is a heavy rail line that provides a feeder service for people traveling in suburban areas along the Taling Chan-Bang Sue (Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Station4/) -Rangsit axis. This is currently operated by SRTET (a state enterprise under the management of the State Railway of Thailand) on a rolling annual basis, though the SRT plans to offer a 50-year operating concession to the private sector once all 54.24 kilometers of the line are operational. Initially, 14 stations (including the Bang Sue Central Station) and 41.5 kilometers of track were opened to the public at the end of 2021. This line is composed of 2 sections.

-

Nakhon Withi (Light Red Line): This covers 15.2 kilometers between Bang Sue and Taling Chan. At present, 3 of 5 stations are operational but this is just the initial stage of what will be a 54-kilometer line running east-west between Hua Mak and Salaya in Nakhon Pathom.

-

Thani Ratthaya (Dark Red Line): This line passes through 10 stations and covers 26.3 kilometers along the stretch from Bang Sue to Rangsit. This is, though, only the first section of a planned 80.5-kilometer north-south line that will connect Mahachai in Samut Sakhon with the Thammasat University Rangsit campus.

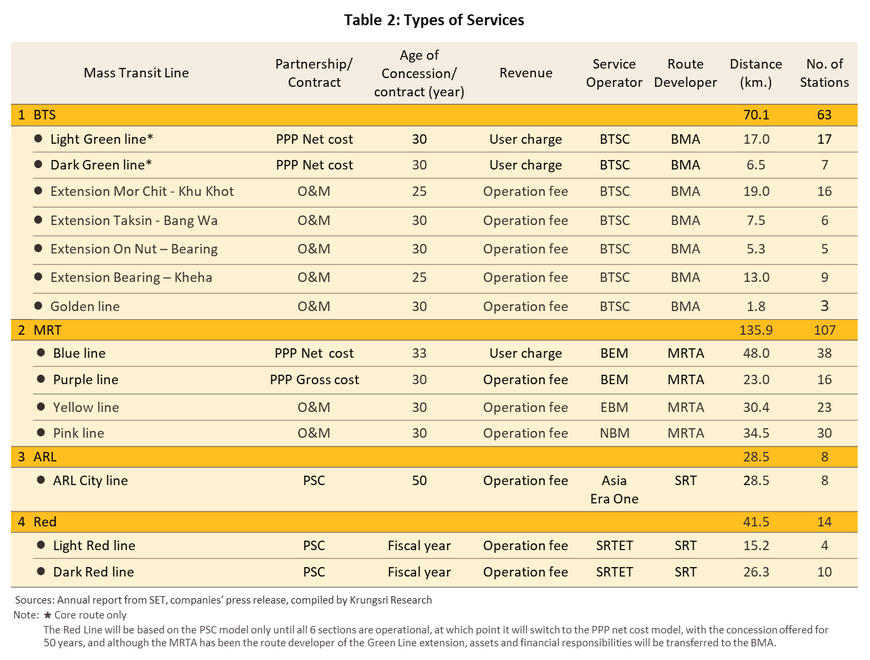

Private-sector players wishing to offer services as mass transit operators need to obtain a concession from the government, and so corporations will compete against one another to bid for these at auctions, though concessions are offered for each line independently. In these cases, the ‘route developer’, i.e., the body responsible for overseeing the project, will be the government or one of three state bodies: (i) the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), although its operations are managed through the BMA’s commercial undertaking, Krungthep Thanakom (KT); (ii) the Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA); or (iii) the State Railway of Thailand (SRT). The winner of the concession is referred to as the ‘service operator’, and at present there are five of these: (i) Bangkok Mass Transit System Public Company (BTSC); (ii) Bangkok Expressway and Metro Public Company Limited (BEM); (iii) SRT Electric Train Company (SRTET); (iv) Eastern Bangkok Monorail (EBM); and (v) Northern Bangkok Monorail (NBM).

In addition to the state of the economy and the cost of living (both of which may influence ridership), concession holders’ income may also be affected by the particular terms and conditions of individual contracts and any additional agreements reached between service operators and the government or other state bodies. These agreements may be structured in a number of different ways, as described below.

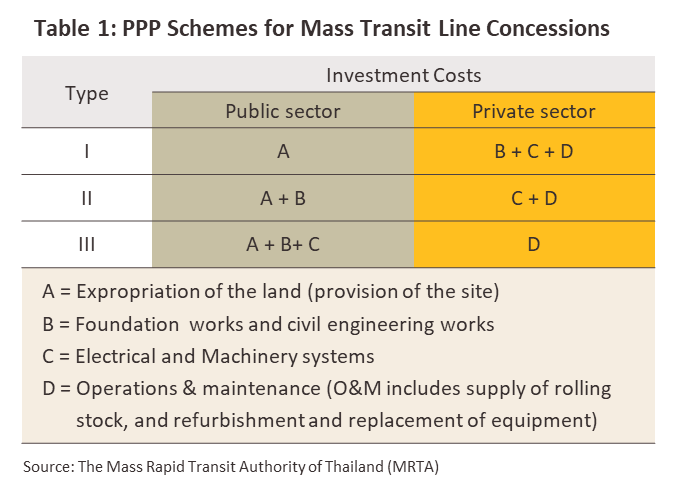

1) Investment structure: Because investing in mass transit systems typically entails considerable up-front costs for which returns are generally made over only extended timescales, these projects are normally undertaken as joint investments by the public and private sectors. There are two main ways of structuring these:

1.1 Public-private partnerships (PPPs)5/: These all involve some degree of joint investment by the public and private sectors, but how this is split between the two and decisions over how the project will be managed will depend upon individual circumstances6/. Nevertheless, PPPs can be divided into three main groups (Table 1): (i) the public-sector partner is responsible only for land expropriation cost in the project, and all other costs are borne by the commercial partner, including structural engineering, construction work and civil engineering, installing electrical equipment and machinery, and operating rolling stock (sourcing trains, operating these, and maintaining and repairing electrical systems and equipment); (ii) the public-sector partner is responsible for land expropriation cost in the project and for overseeing structural engineering, construction work, and civil engineering, while the private-sector partner is responsible for installing electrical systems and equipment and for operating rolling stock; and (iii) the public-sector partner is responsible for all aspects of the project with the exception of the operation of the trains, which is left to the commercial partner.

1.2 Public sector comparator (PSC) system: The public sector is solely responsible for all spending at all stages of the project, with the involvement of the private-sector partner restricted to running the system. In these projects, the route developer will therefore pay the commercial partner a rate as laid out in the concession contract, though this may expose the private-sector player to the risk of seeing their contract cancelled if income fails to meet the targets set for the project or if the company generates losses.

2) For PPP concessions, there are three main ways of splitting the returns between the service provider and the route operator7/, though this covers only income from fares and the management of commercial space within or around stations and excludes income from the maintenance and repair of equipment.

2.1 Net cost concession: Under these schemes, the private-sector partner will retain the income generated from operating the system and collecting fares, though the service provider will have to return a fixed fee to their public-sector partner as per the concession agreement. The commercial partner therefore has the opportunity to generate additional income if receipts from fares or from the renting out of commercial property in stations is greater than anticipated. However, the reverse of this is also true, and the company may have to accept losses if ridership fails to meet the target.

2.2 Gross cost concessions: These are the reverse of net cost concessions, with the government collecting fares and then making regular fixed payments to the private-sector partner, again, as determined in their service contract. Under this system, income for rapid mass transit system operators will not fluctuate with overall operations and so this form of concession helps to reduce risk for private sector partners in the first ten years of operations, a period when income may be uncertain and investors may face the possibility of making losses.

2.3 Modified gross cost concession: Under this system, as with gross cost concessions, the government will collect fares from passengers and make payments to the private sector partners, which consist of two parts: (i) fixed payments as compensation for the operation of services, made on a timetable and to a level set in advance in the contract (as with the gross cost concession model); and (ii) a bonus, paid when the number of journeys/travelers or income from commercial property is greater than expected. However, as yet, no Thai mass transit projects have been structured on this basis.

Of the 10 lines that are currently open to the public, the largest share are public-private partnerships structured on the net cost model. These include the BTS Green line (this is actually 2 lines), Gold line, and the MRT Blue, Yellow, and Pink lines. The MRT Purple Line is a PPP gross cost concession, while the ARL and the SRT Red Line (also 2 lines) split public- and private-sector responsibilities and returns according to the public sector comparator model, with the state hiring in the service operator to oversee management of the system as agreed in the relevant contract (Table 2).

Future changes in income and improvements in the general business outlook for service operators will largely be determined by increases in ridership, the expansion in the service area and the number of stations, and the development of additional commercial space. As for fares and charges for repairs and operations, while these have a significant impact on income, to a large extent they are determined by the government, and how and when increases in these may be made will be specified in the original concession agreement, although occasionally, fares may even be cut (for example during economic crises). There is therefore substantial variation in the prospects for individual service providers, with the opportunities and threats faced by concession holders or service operators heavily influenced by the length and the structure of their particular investment.

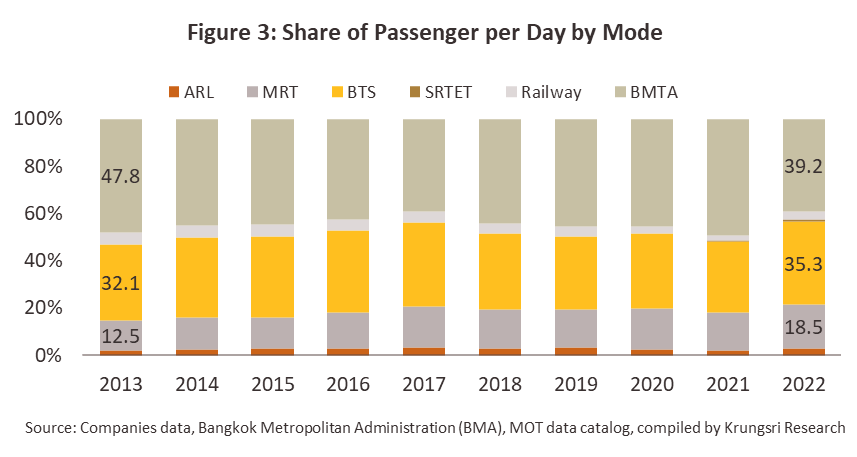

The metro system provides travelers with a reliable option for reaching the center of the city quickly and conveniently, according to a fixed timetable, and without the risk of being stuck in traffic. Thanks to the buildout of extensions and interchanges, the network is now reasonably extensive and its increasing reach means that the proportion of travelers using the system rose from 46.8% of all commuters in 2013 to 57.6% in 2022 (Figure 3). Nevertheless, thanks to their lower cost and greater coverage, bus services operated by the BMTA and by private-sector players currently have higher usage rates within the BMR.

SITUATION

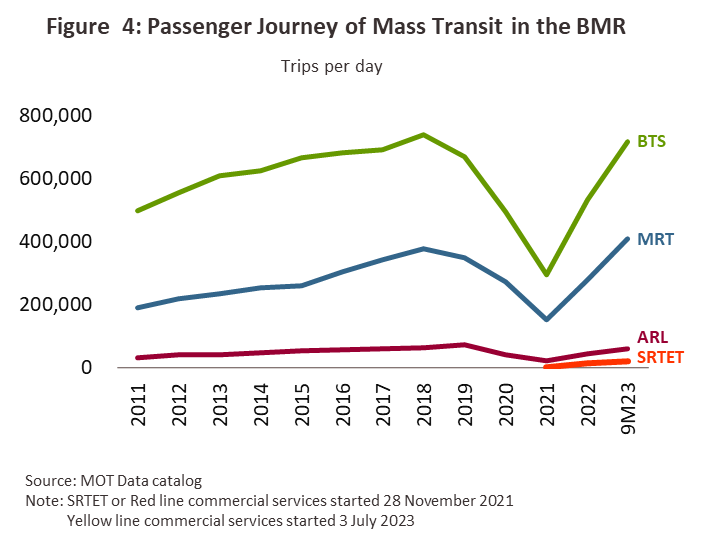

The abating of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022, which allowed domestic social and economic life to return to normal, and the full reopening of the country to foreign arrivals in 2H22, which boosted the tourism sector, combined to stoke strengthening demand for mass transit services. This then fed into a jump in ridership to 0.87 million trips per day, up 84.1% from its 2021 level (Figure 4) and not far off the pre-pandemic daily average of 0.95 million trips. Growth in demand stretched into 9M23 as the outlook for both private-sector consumption and the tourism sector continued to brighten, helped in part by government stimulus measures that targeted both domestic consumption (i.e., the Shop and Refund and phase 5 of the We Travel Together programs) and foreign tourism (i.e., ending vaccination requirements and extending the permitted length of stay in Thailand for some tourists), the latter then helping to lift arrivals to some 20 million. The industry also benefited from the start of full commercial operations on the Yellow Line in July 2023, which helped to facilitate the transfer of passengers to and from the main lines.

To help boost demand, operators have steadily lifted pandemic-era restrictions on services, including controls on the number of passengers per train (with effect from May 1, 2023), while on the MRT, service operators also held back on fare increases to help alleviate problems with the rising cost of living. Alongside this, operators also increased the number and frequency of train services and extended operating hours when major events were underway. To help increase integration across the wider rail network, trains servicing 52 lines operated by the State Railway of Thailand in the north, northeast, and south of the country have switched to running out of Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Terminal Station. This change came into effect on January 19, 2023, and has helped to make onward travel to central Bangkok, the suburbs, and the rest of the country much easier.

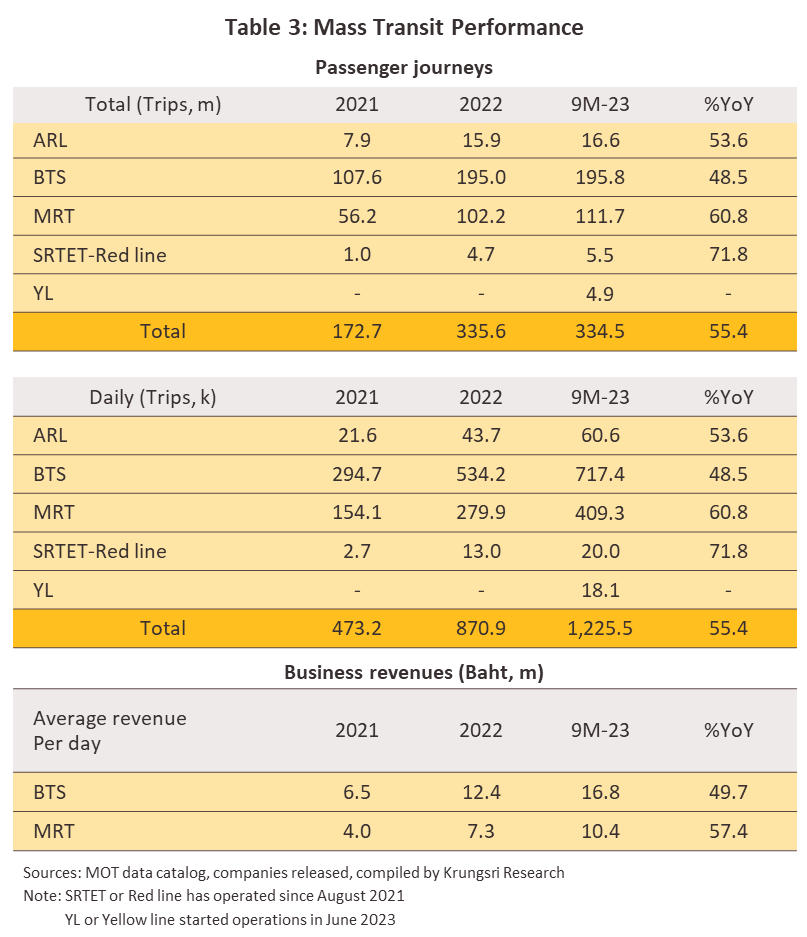

Ridership on the mass transit system over 9M23 has been as follows (Table 3):

-

Over 9M23, ridership increased 55.4% YoY to a total of 334.5 million person-trips, or an average of 1.2 million per day. Usage rose 48.5% YoY on the BTS (58.5% of all person-trips), 60.8% YoY on the MRT (33.4% of the total), 53.6% YoY on the ARL (4.9% of the total), and 71.8% YoY on the SRTET Red Line (1.6%). On the YL Yellow Line, ridership totaled 4.9 million person-trips, or an average of 18,000 per day (1.5% of the total).

-

Income from fares on the core routes jumped 52.5% YoY to THB 7.4 billion. An average 7% rise in fares from THB 16-44 to THB 17-47 on the BTS Green Line (from 1 January 2023) lifted receipts 49.7% YoY to THB 4.6 billion, while income on the MRT Blue Line surged 57.4% YoY to THB 2.8 billion.

Operators will continue to benefit from tailwinds through the remainder of 2023. (i) The government is cutting fares to THB 20 for all journeys on the SRT Red and Purple lines between 16 October 2023, and 30 November 2024. These connect to the main Green and Blue lines and so the fare reductions should help to lift overall ridership, especially from travelers transiting through Don Muang. In addition, the start of commercial operations on the Pink Line in November 2023, which connects to the Green, Purple and Red lines, will add further to the number of passengers on the main metro routes. (ii) The rising cost of transport fuels is diverting demand away from the use of private vehicles and towards the metro system, which offers the additional benefit of not being affected by traffic congestion. (iii) Demand will rise with the start of the year-end celebrations and the onset of the tourism high season, which will boost ridership on the main lines running into the city center and secondary lines serving Don Muang and Suvarnabhumi airports. For 2023 overall, 427.5 million person-trips should be made across the network, or an average of 1.6 million per day, a rise of 79.8% YoY. Likewise, income is expected to hit THB 10.2 billion, up 41.2% from its 2022 level. This will be split between increases of 38.1% YoY for the BTS (to THB 6.3 billion) and 46.5% YoY for the MRT (to THB 3.9 billion).

OUTLOOK

Krungsri Research sees demand for mass transit services continuing to grow solidly over 2024 to 2026, with demand lifted by the following factors.

-

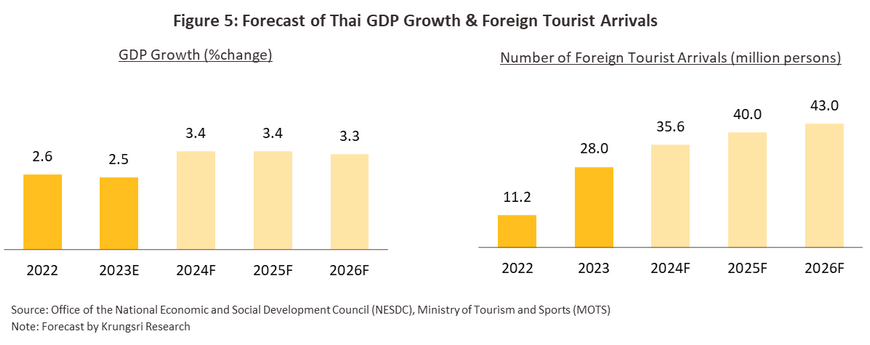

Consumer spending power will strengthen in line with forecast 3.0-4.0% annual growth in the domestic economy. This will then stimulate an uptick in economic and social activity which, alongside the return of tourist arrivals to their pre-COVID total of around 40 million (expected by 2025), will directly add to the number of passenger-trips being made across the metro system (Figure 5).

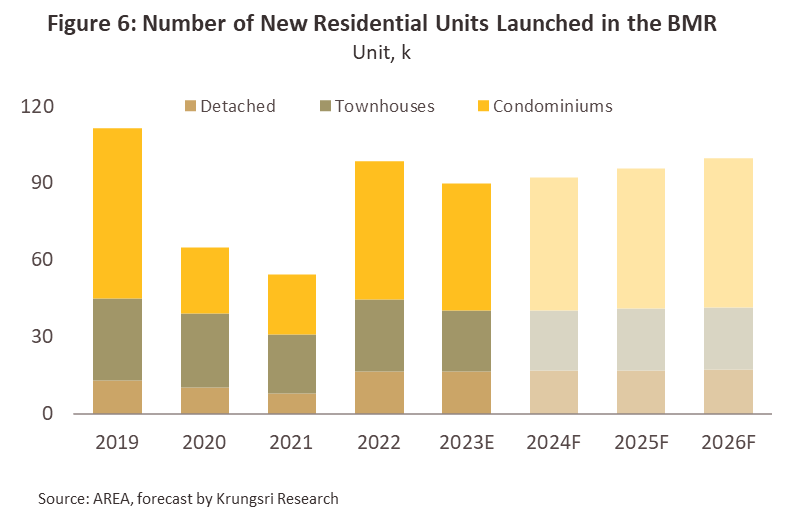

- Opening new lines will encourage the private sector to increase investment in commercial projects in areas newly served by these, and this will then feed an expansion in communities in these areas. Investments will be directed to the development of both residential property (working-age individuals are especially keen to live in areas easily accessible by the mass transit network) and commercial units (e.g., larger shopping centers and community malls), which will steadily spread further out into remoter, more suburban areas. Krungsri Research thus expects that over 2024 to 2026, an average of new 96,000 residential units launch will come to market annually (Figure 6). In addition, the fourth amendment to the city planning regulations will expand both ‘orange areas’ (land approved for the development of medium density residential property) and ‘red areas’ (land approved for commercial use) in locations served by new metro lines. This includes Ramkhamhaeng Road (the Orange Line), Lat Phrao Road (the Yellow Line) and Min Buri (the Pink and Orange lines). This will then allow property developers to expand their investments in these areas and to construct buildings over 23 meters high, adding to the future uptake of metro services.

-

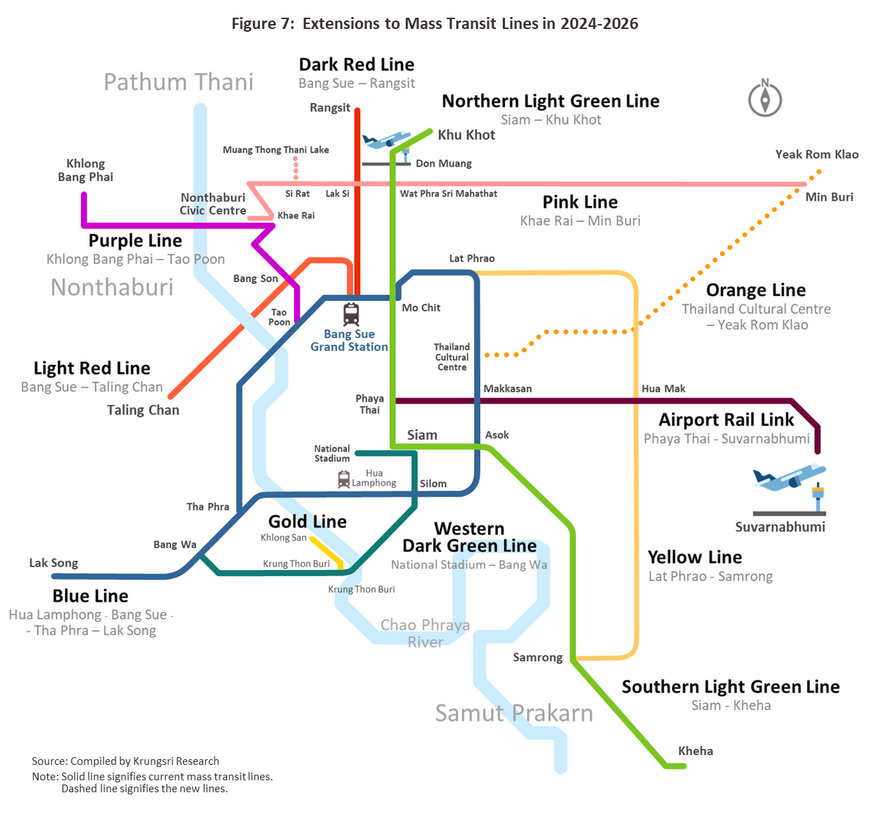

Over the next three years, new routes and extensions to existing lines will include the Pink Line (in 2024) and extensions to this (Sirat-Muang Thong Thani, 2025), and the Eastern Orange Line (Cultural Centre-Min Buri, 2026) (Figure 7). This will then facilitate travel between outer and central parts of Bangkok, increase the circulation of passengers from areas further out through the Green, Purple, Red, and Yellow lines, and add to the number of travelers on routes passing through residential communities and other important areas such as the Government complex at Chaengwattana, the Government civic centre at Nonthaburi and Muang Thong Thani. 2024 will also be the first year during which service operators will receive an entire year’s worth of income from the commercial operation of the Yellow and Pink lines, which will add to receipts coming from other commercial operations (e.g., rents from commercial units and advertising space).

-

Consumers will likely show a growing preference for using the metro system, though this will be particularly noticeable among middle class travelers since these have the disposable income to pay for the services while also valuing rapid, reliable transport that sidesteps problems with congestion. Indeed, the 2022 TomTom Traffic Index ranks Bangkok the 57th worst of the 390 major cities surveyed for traffic congestion. These problems are largely driven by the increasing number of vehicles on Thai roads, which jumped 11.9% (or by 849,388 autos) in 2022, and this total is expected to rise by another 3.0-4.0% annually over 2024 to 2026. In addition, transport fuels will remain expensive through the next few years (Dubai crude is forecast to average USD 80-90/bbl through the period) and this will make comprehensive public transport networks more attractive by comparison.

-

The government plans to increase the integration of other public transport modalities (e.g., boats, regular buses, shuttle buses, and motorcycle taxis) into the metro system and to use a common ticket or to offer discounts for travelers switching between these. This will include moves such as imposing a single charge on travelers when they enter the state rail network (i.e., the mass transit system and the commuter rail system). In fact, this began to operate in November 2023 where the Red and Purple lines join, and when travelers pay by EMV contactless cards, their fare will be cut to THB 20 for a single or THB 40 for a day return, or to a single charge of THB 800 per month. This system is expected to become operational in 2024, and this will then encourage greater mixing of transport routes.

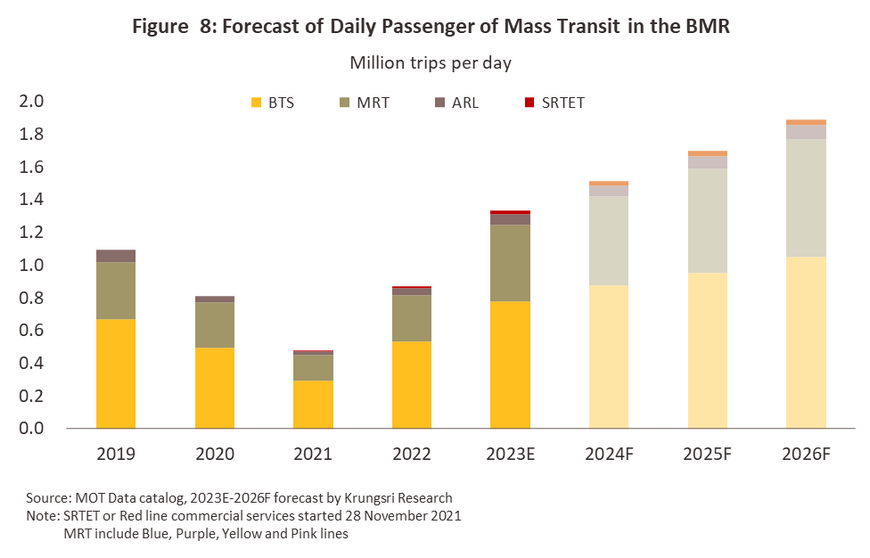

Krungsri Research sees ridership and income strengthening through 2024 to 2026.

-

Overall ridership should increase at an average rate of 10.0-12.0% annually, or to 1.85 million passenger-trips per day. Demand is forecast to be up 9-10% on the BTS, 13-15% on the MRT, 9-11% on the ARL, and 12-15% on the SRTET.

-

Income from fares will rise by an average of 7.6% per year on the core routes, split between an increase of 5.8% on the BTS Green Line and one of 10.4% on the MRT Blue Line.

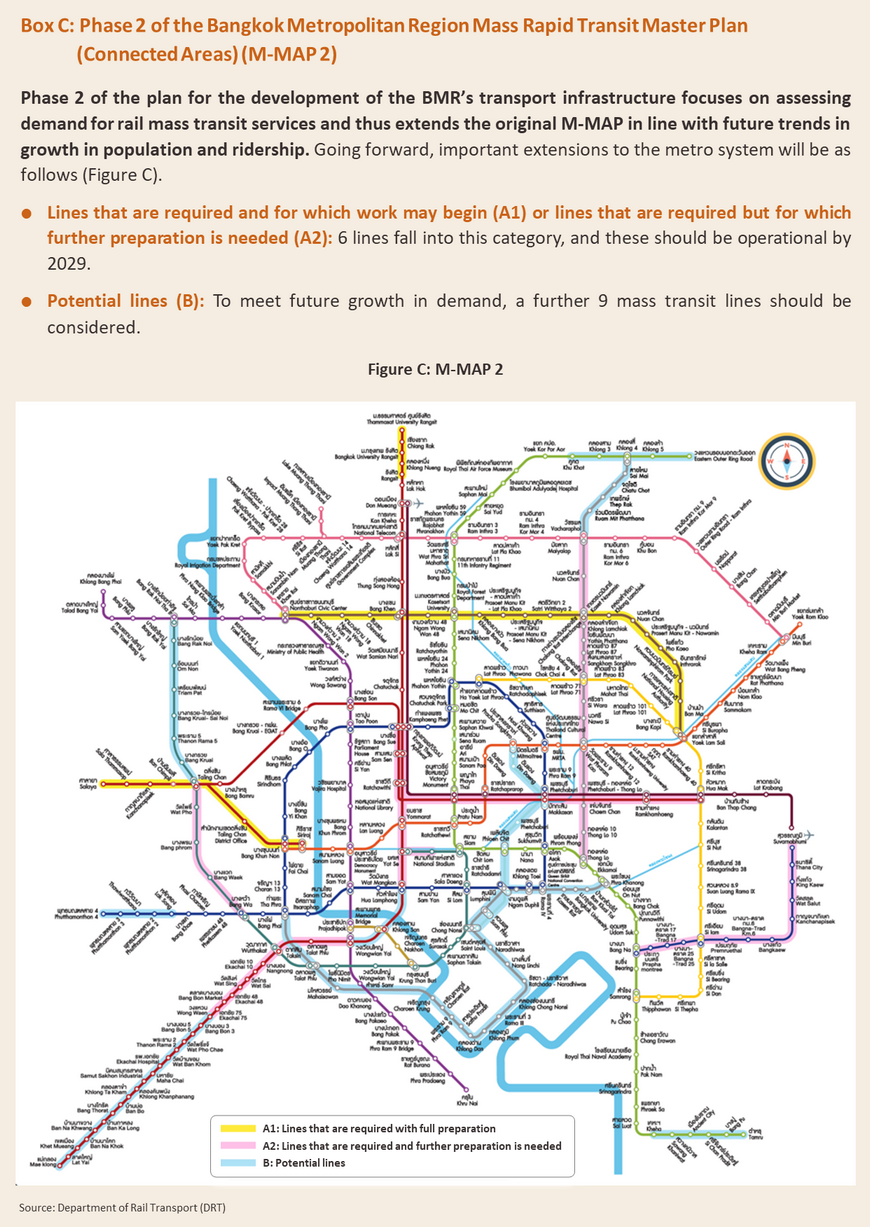

More broadly, ongoing government support for investment in the expansion of the mass transit network and the construction of new lines will increase integration across the system. Corporations already playing a role as mass transit service providers will thus have the opportunity to significantly step up their investments, and this will then allow players to generate additional income from operating metro lines (i.e., from passenger fares and from service incomes for the maintenance and repair of equipment) and from connected services (i.e., from managing commercial space for advertising, the use of telecommunications system, or leasing out rental units) in carriages and in and around stations.

Despite this broadly positive outlook, a number of headwinds have the potential to trouble the industry, including: (i) the impact of high levels of household debt on consumer purchasing power, which may then affect affordability to pay for transport services; (ii) slow growth in both the domestic and the international economies, which may drag on demand from tourists; and (iii) operating costs (especially for labor and electricity) that will tend to track upwards, and this may periodically affect profitability.

1/ Mass transit systems are defined as transport systems that move large numbers of passengers along fixed routes according to predetermined schedules. Land-, air- and water-based mass transit systems are all found in Thailand, although land-based services (including rail) are the primary means of travel. These services include: (i) buses, both standard types and minibuses, and (ii) rail transport, including suburban railways (operated by the State Railway of Thailand) and the mass rapid transit (the MRT and BTS) (a joint public-private initiative).

2/ According to the Numbeo Traffic index, Bangkok is one of the 5 worst cities in Southeast Asia for traffic congestion.

3/ Bangkok can be divided into three zones according to its administrative arrangements. (i) The inner zone is composed of Phra Nakhon, Pom Prap Sattru Phai, Samphanthawong, Pathum Wan, Bang Rak, Yan Nawa, Sathon, Bang Kho Laem, Dusit, Bang Sue, Phayathai, Ratchathewi, Huai Khwang, Khlong Toei, Jatujak, Thonburi, Khlong San, Bangkok Noi, Bangkok Yai, Din Daeng and Watthana. (ii) Further out is the middle or central region, which includes Phra Khanong, Prawet, Bang Khen, Bang Kapi, Lat Phrao, Bueng Kum, Bang Phlat, Phasi Charoen, Chom Thong, Rat Burana, Suan Luang, Bang Na, Thung Khru, Bang Khae, Wang Thonglang, Khan Na Yao, Saphan Sung and Sai Mai. (iii) Finally come the outer, suburban districts of Min Buri, Don Muang, Nong Chok, Lat Krabang, Taling Chan, Nong Khaem, Bang Khun Thian, Lak Si, Khlong Sam Wa, Bang Bon and Thawi Watthana.

4/ Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Terminal Station, or Bang Sue Grand Station, is a major rail hub linking the S.R.T. Red Line, the ARL, and long-distance trains. In the future, this will also connect with high-speed lines.

5/ As per the Private Participation in State Undertaking Act of 2019, development of the urban metro system is one of the areas under which public-private partnerships are currently permitted.

6/ Stages of the project at which the private sector may choose to invest and participate include laying foundations, construction and civil engineering works, instillation of the electrical system and/or machinery, supplying and operating the rolling stock, managing commercial space in and around stations, and undertaking maintenance of trains and the system equipment. If the private sector operator that wins the bidding for the concession chooses to invest at these various stages, it will generate profits from a range of different sources, including: fees for demolition, construction work, and civil engineering; income from the installation of equipment, charges for managing the system; fees for providing services to maintain electrical systems and equipment; fares collected from travelers; and charges from the use of advertising space in trains and for the commercial development of land in and around stations (e.g., renting out advertising or retail space, or leasing access to installers of communications equipment).

7/ The division of returns specified in contracts may include additional conditions, such as that the share of income may increase after a set period of time (every 10 or 15 years, for example) or that the burden of bearing some costs should be eased (e.g., that maintenance costs should be cut at a fixed rate every 5 years.)

8/ The central business district (CBD) is an area that is dominated by business activities and that is located in the easy-to-reach center of the urban region. The CBD is densely populated and so expansion tends to occur vertically. In Bangkok, the CBD comprises Silom, Sathorn, Surawong, Rama 4, Ploenchit, Wireless Road, Sukhumvit (Sois 1-71) and Asoke.

.webp.aspx)