EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Thailand’s electric vehicle (EV) industry is expected to continue growing during 2026–2028, with new passenger BEV registrations projected at 125,000 units annually, or 3.8% CAGR. Key drivers include: (i) the launch of new models with longer ranges, (ii) the full enforcement of Euro 6 standards in 2026, which will raise ICE vehicle costs and prices, and (iii) the easing EV price war in Thailand, as automakers seek to preserve shrinking profit margins amid previous intense competition and persistently high unit production costs due to limited economies of scale in local offset production. However, demand may slow after subsidies under the EV3.5 scheme expire. In the meantime, supply is set to rise due to offset production under EV3.0 and 3.5, potentially intensifying domestic competition. Meanwhile, passenger BEV exports are projected to reach 20,000 units per year, supported by the rule that “one exported passenger BEV counts as 1.5 offset units” and rising global demand driven by stricter environmental standards. Still, exports may face tough competition, especially from China, which is expected to offload excess supply globally. Thai-made BEVs may also face cost disadvantages due to small-scale production, limiting global price competitiveness.

Krungsri Research view

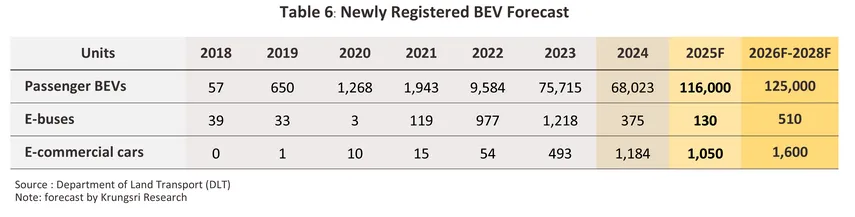

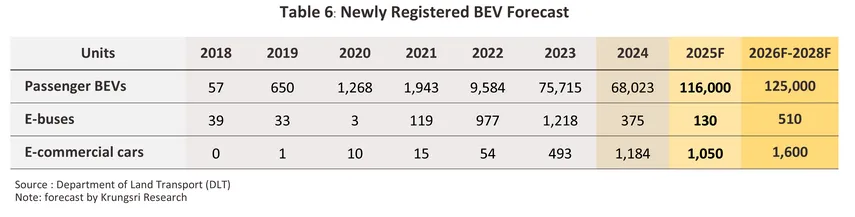

During 2026–2028, new registrations of electric passenger cars, electric buses, and electric commercial vehicles are expected to continue rising.

-

Passenger BEVs: New registrations are expected to continue growing, though at a slower pace following the expiration of EV3.5 subsidies in 2025. Demand will be partly supported by more stable BEV prices as the domestic price war eases, in contrast to ICE vehicles, which may face rising costs and prices due to the enforcement of the Euro 6 standard in 2026. On the supply side, competition remains strong with the launch of new, more advanced models offering longer ranges, particularly from Chinese automakers, due to accelerated offset production during 2026–2027. Additionally, export markets may contribute more significantly to revenue, despite ongoing challenges from China’s continued efforts to offload excess supply.

-

e-buses and e-commercial vehicles: New registrations are expected to rise, supported by (i) a new investment cycle in e-bus services, targeting 1,520 units during 2026–2032, (ii) longer driving ranges per charge and falling prices, driven by recent investments in large EV battery development, and (iii) the launch of new electric commercial models, especially BEV pickups from leading Japanese automakers in Thailand. However, growth may remain limited due to the lack of charging stations in provincial areas.

Overview

The electric vehicle (EV) industry is an emerging sector, driven initially more by government-policy—both international and national—than by market-driven forces, which remain underdeveloped. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) set a global target to limit the rise in average temperature to no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Thailand ratified the agreement in 2016, leading to the formulation of a national energy framework that promotes clean energy adoption. The country aims to achieve net-zero carbon dioxide emissions between 2065 and 2070. One of the key energy policies involves transitioning the transport sector toward green energy through EV technology. As a result, various measures have been introduced to stimulate the growth of Thailand’s EV industry, as follows:

The initial phase (2016–2021) of EV industry development was implemented alongside with the support measures for energy-efficient compact cars under the Eco-car program. The government allowed manufacturers to include EV production volumes in their Eco-car production count, on the condition that they produced more than 100,000 units annually, to qualify for the program incentives. These benefits included an 8-year corporate income tax exemption, a 90% reduction in import duties on auto parts, and import tax reductions on machinery used in production1/.

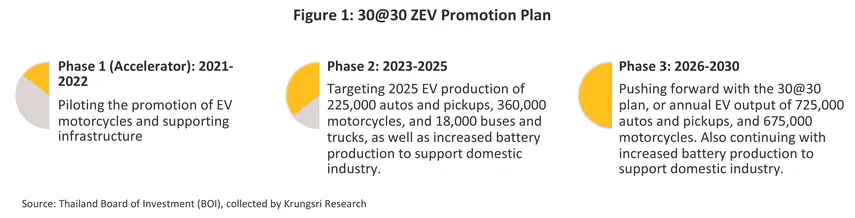

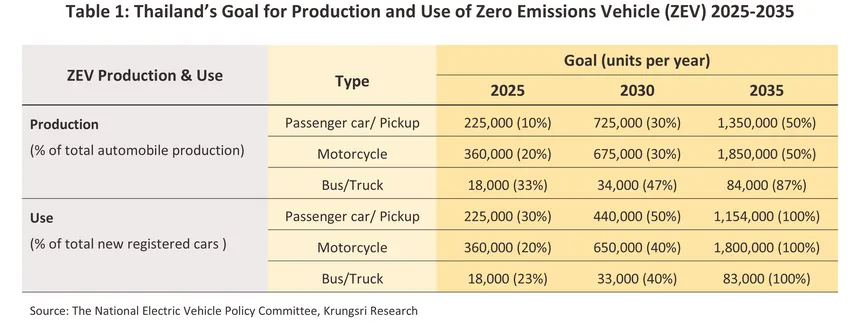

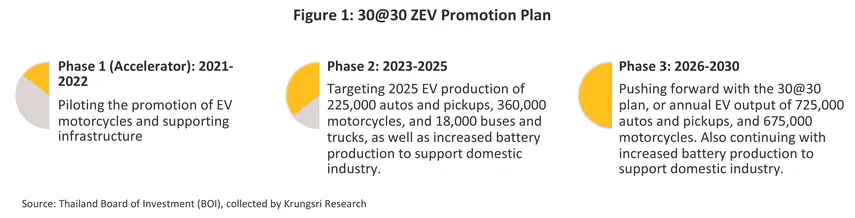

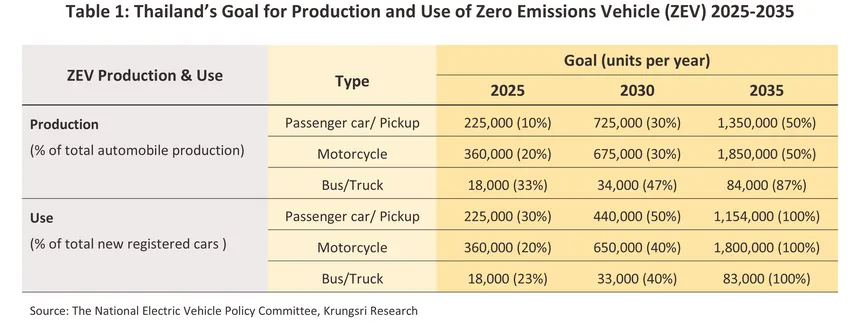

The subsequence phrase (from 2021 onward), introduced the driving measures aimed to stimulate market growth and support investment. On May 12, 2021, the national EV policy committee officially launched the Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) framework under the 30@30 policy, targeting for ZEVs to account for at least 30% of total vehicle output by 2030. The roadmap is divided into three phases (Figure 1), with production and usage targets clearly set by 2025, passenger EVs and electric pickup trucks are expected to represent 10% of total output, with ZEVs making up 30% of new registrations. By 2030, the targets rise to 30% for production and 50% for registrations, and by 2035, to 50% and 100%, respectively (Table 1), under the following measures::

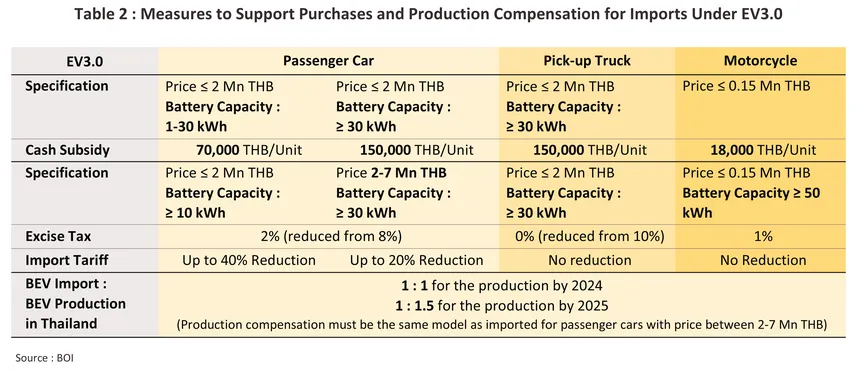

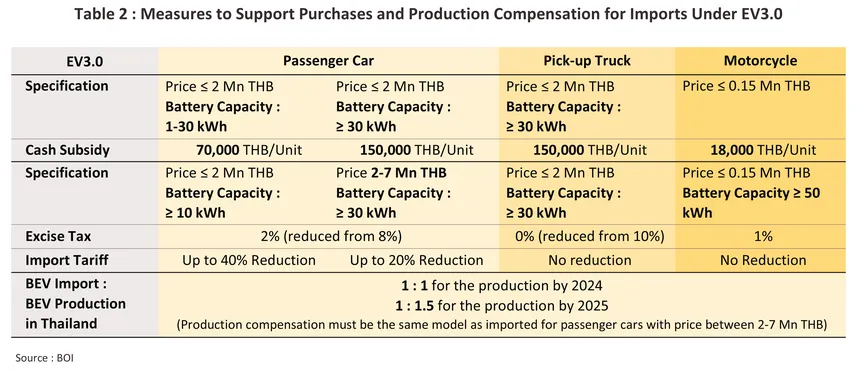

EV3.0 measures (2022–2025)2/ were introduced to promote investment in Thailand’s EV industry. The government provided support to EV manufacturers across several areas (Table 2), including: (i) subsidies for Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs3/) imported for domestic sale during 2022–2023, offering 70,000–150,000 baht per unit for locally produced passenger BEVs and pickup truck BEVs; (ii) import duty reductions of 20%–40% for BEVs brought in between January 1, 2024 and December 31, 2025; and (iii) other measures such as restructuring the excise tax system to gradually reduce rates for BEVs, Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV) and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), while increasing rates for internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles every two years from 2026 to 2030. Additional support includes annual tax reductions for BEVs registered between October 1, 2022 and September 30, 2025, and initiatives to expand EV charging stations by both public and private sectors to facilitate EV usage.

Manufacturers receiving benefits under the EV3.0 scheme and importing electric vehicles for domestic sale during 2022–2023 are required to offset production locally within 2024–2025, subject to the following conditions: (i) in terms of production, manufacturers must produce an equivalent volume for vehicles imported in 2022, and 1.5 times the volume for those imported in 2023; (ii) in terms of vehicle models, for imported passenger BEVs with battery capacity not over 30 kWh and priced below 2 million baht, manufacturers may produce and sell any BEV model locally. However, for passenger BEVs with battery capacity from 30 kWh and priced between 2–7 million baht, manufacturers must produce the same model as imported for domestic sale.

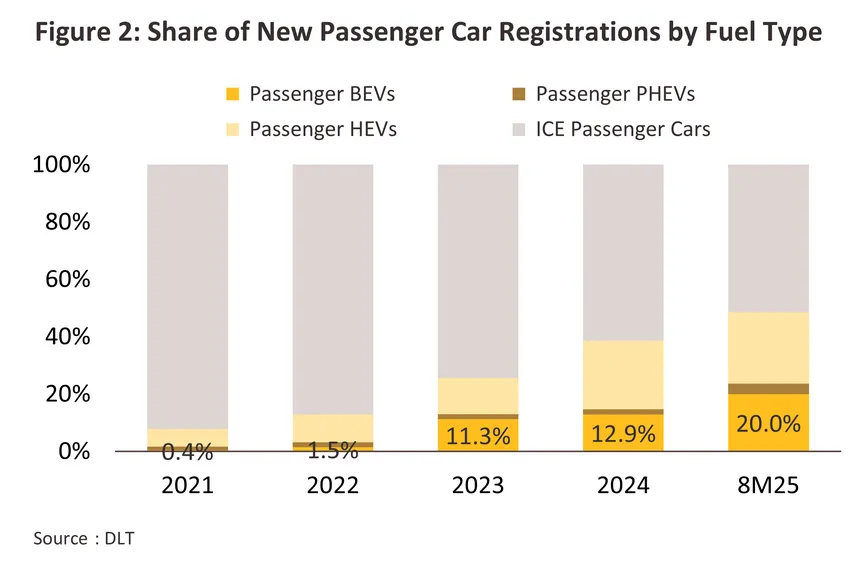

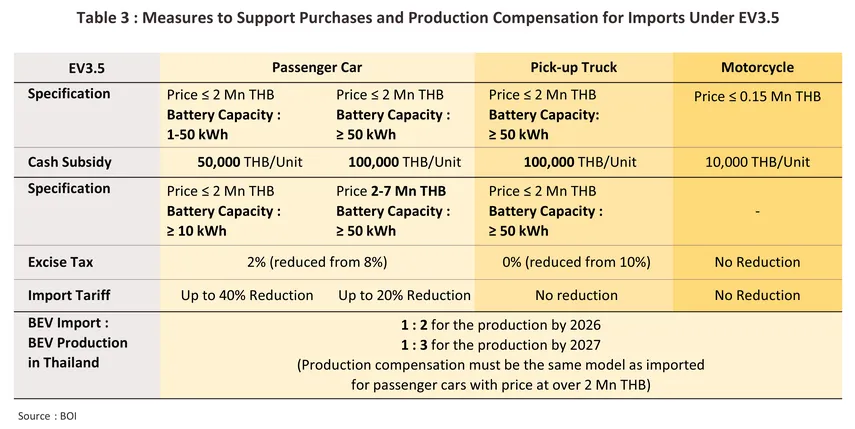

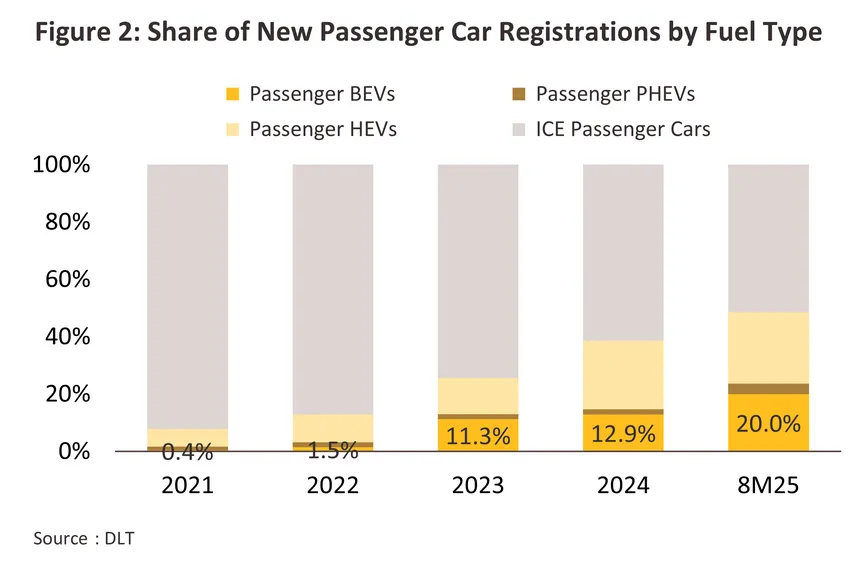

As a result of the EV3.0 measures, domestic EV adoption has surged significantly. This is evident from the registration of 85,299 passenger BEVs during 2022–2023, up from just 0.4% of total passenger vehicle registrations in 2021 (prior to the incentive scheme) to 11.3% in 2023 under EV3.0 (Figure 2). The measures also attracted continued investment from new EV manufacturers establishing production bases in Thailand. Subsequently, the government launched EV3.5 measures (2024–2027) to further support industry growth, with official implementation beginning on January 2, 2024 (Table 3), as follows:

-

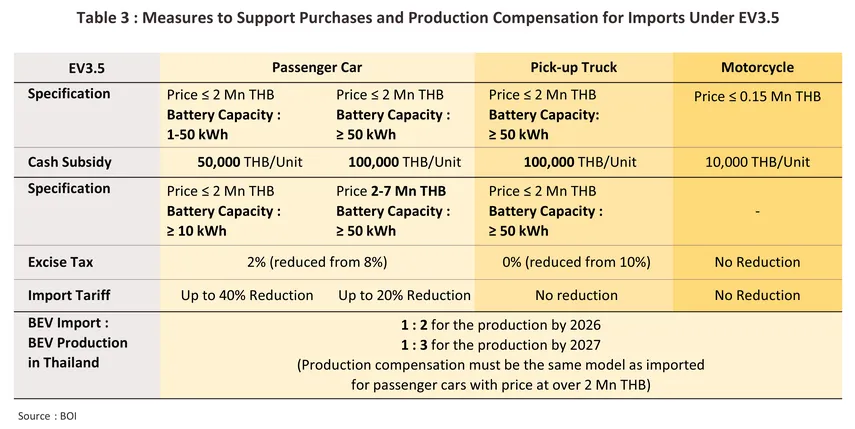

Subsidy scheme: financial support for BEVs imported for domestic sale during 2024–2025 has been adjusted as follows: (i) 50,000–100,000 baht per unit for passenger BEVs priced below 2 million baht; and (ii) 100,000 baht per unit for pickup truck BEVs priced below 2 million baht with battery capacity exceeding 50 kWh.

-

Tax reduction measures: import duties and excise tax rates for fully built passenger BEVs and pickup truck BEVs remain unchanged from those applied under the EV3.0 scheme4/.

-

Production measures: manufacturers receiving benefits under the EV3.5 scheme and importing BEVs for domestic sale during 2024–2025 must offset production locally within 2026–2027 under the following conditions: (i) production requirements: manufacturers must produce two times and three times the volume of imported BEVs for those starting production in 2026 and 2027, respectively; and (ii) vehicle model requirements: for imported passenger BEVs priced from 2 million baht upward, manufacturers must produce the same model as imported for domestic sale.

However, on December 4, 2024, the National Electric Vehicle Policy Board (EV Board) approved a deferral of offset production under the EV3.0 scheme, following lower-than-expected BEV passenger car sales in 2024. Manufacturers supported under the EV3.0 scheme are now permitted to shift their offset production to 2026–2027 under the EV3.5 scheme, at a ratio of 2–3 times the number of previously imported units, replacing the original requirement of 1 to 1.5 times within 2024–2025.

In addition, due to lower-than-expected offset production under the EV3.0 scheme (2024–2025), the EV Board resolved to revise the subsidy disbursement criteria of the Excise Department for manufacturers supported under both EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes5/. The resolution was passed on July 30, 2025, with the following details:

-

Participants in the EV3.0 scheme who do not opt for a deferral must submit a forecast plan and report monthly offset production. The excise department will withhold subsidy disbursement until cumulative offset production reaches at least 50% of the required total.

-

Participants in the EV3.0 scheme seeking a deferral may establish additional EV manufacturing facilities to ensure offset production is completed within the designated timeframe.

-

Participants in the EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes are required to submit forecast plans and report offset production to the excise department. Subsidy disbursement will be withheld if cumulative offset production falls below the specified threshold6/.

-

Participants in the EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes may reconsider their subsidy claims. For EVs already imported and registered but not yet subsidized, companies may opt to return the excise tax differential along with applicable surcharges and penalties, in order to exclude those units from offset production requirements.

The EV Board also revised the calculation criteria for offset production under the EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes. Starting in 2025, 1 unit of BEV produced and exported will be counted as 1.5 units toward offset production, aiming to incentivize manufacturers to expand into export markets

Promotion of Investment in the EV Industry

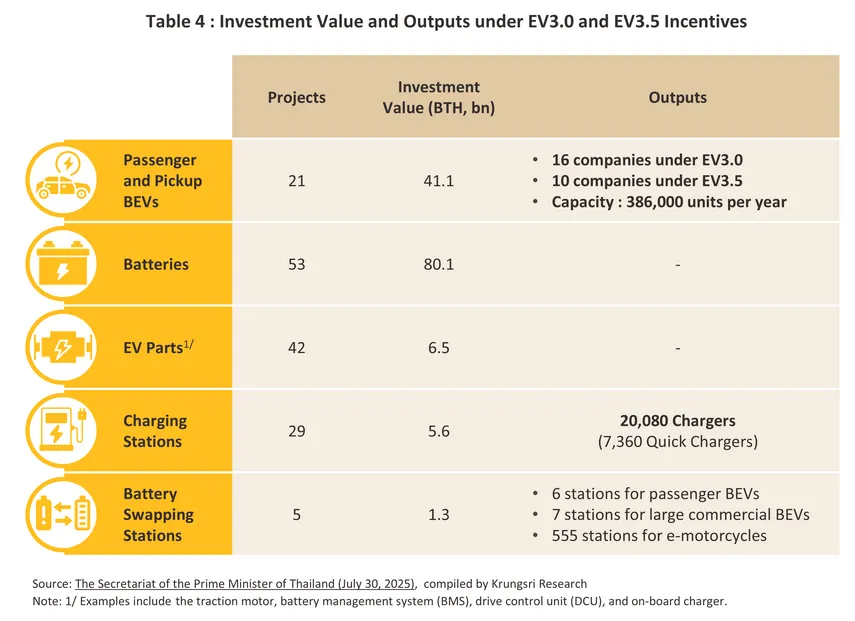

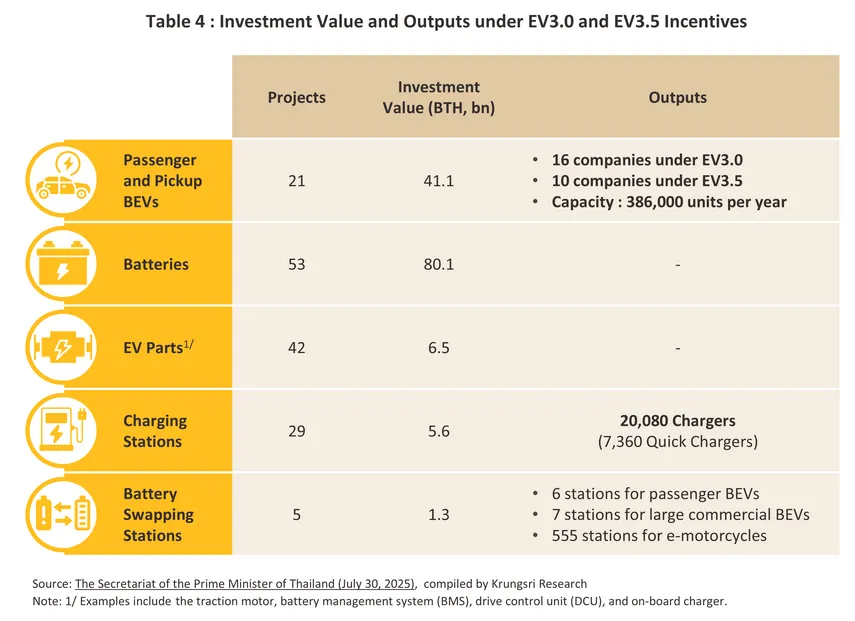

Under the EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes, from 2022 to June 20257/, Thailand approved several investment projects and capital commitments in businesses and industries related to electric vehicle manufacturing (Table 4), as follows:

-

BEV production: investment in passenger BEVs and pickup truck BEVs manufacturing totaled THB 41.1 billion, with a combined annual production capacity of 386,000 units. Investment in bus BEVs and truck BEVs manufacturing amounted to THB 2.2 billion, with a total capacity of 4,800 units per year. There are 16 companies participating in the EV3.0 scheme and 10 companies in the EV3.5 scheme8/. Cumulative registrations of eligible BEV passenger cars and 1-ton pickup trucks under both schemes reached 175,064 units, accounting for 86.2% of the total cumulative registrations of over 203,000 units9/.

-

BEV Parts Production: This includes (i) battery manufacturing, with total investment value of THB 80.1 billion, and (ii) EV parts such as traction motors, Battery Management Systems (BMS), Drive Control Units (DCU), and on-board chargers, with total investment value of THB 6.5 billion.

-

Electric Infrastructure: This includes (i) chargers, with total investment of THB 5.562 billion for 20,080 chargers. As of June 2025, 11,832 chargers10/ had been installed, representing 58.9% of total supported chargers. Previous installations have focused on fast chargers, with 6,760 units installed—91.8% of the supported fast chargers. Meanwhile, 5,072 regular chargers have been installed, accounting for 39.9% of the supported regular chargers. (ii) Battery swapping stations, with total investment of THB 1.3 billion, comprising 6 stations for BEV passenger cars, 7 stations for BEV commercial vehicles, and 555 stations for electric motorcycles.

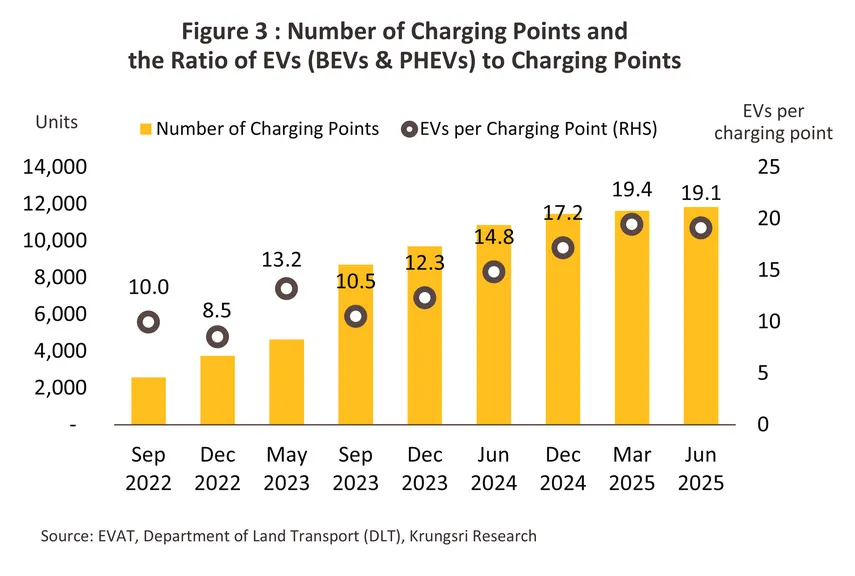

Despite the continued expansion of EV charger installations in Thailand, the current number of chargers remains insufficient to support the rapid growth of EVs. A comparison between the number of chargers and the cumulative registrations of chargeable electric vehicles (BEVs and PHEVs) in May 2023 and June 2025 reveals that Thailand saw an average increase of 59.9% CAGR in EV chargers (from 4,628 units in May 2023 to 11,832 units in June 2025). This growth rate is lower than the 92.4% CAGR in cumulative registrations of chargeable EVs (from 61,001 vehicles in May 2023 to 225,792 vehicles in June 2025), indicating that the country’s electrical infrastructure remains inadequate to accommodate the rising number of EVs. In May 2025, Thailand had a ratio of 13.2 EVs per charger, which rose to 19.1 EVs per charger in June 2025 (Figure 3).

Situation

BEV registrations

Passenger BEVs

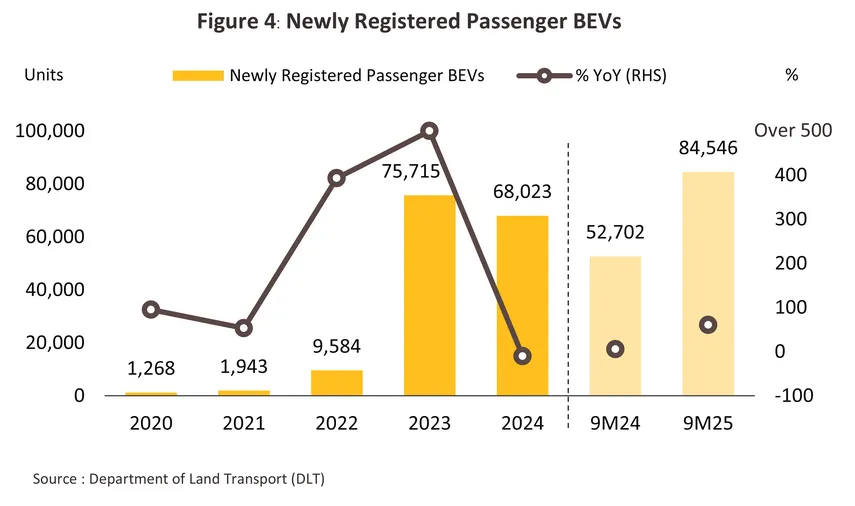

New registrations of passenger BEVs during the first 9 months of 2025 surged 60.4% YoY to 84,546 units (Figure 4), accounting for 48.9% of total passenger car registrations. Key supporting factors include the following:

-

The easing of the EV price war in 2025: This was reflected in the retail prices of Chinese passenger BEVs sold at the Motor Show 2025 (March–April 2025), which stabilized with only a -2.7% decline compared to the Motor Expo 2024 (November–December 2024), where prices had dropped over -13.0%. This trend was driven by: (i) Continuous declines in EV manufacturers’ net profits resulted from the EV price war that began in 2022, forcing some automakers to face financial difficulties and slow down further price cuts to preserve margins, and (ii) the conditions under the EV3.0 scheme, which require manufacturers receiving incentives to produce locally. However, due to limited production volumes, they have yet to benefit from economies of scale, resulting in high unit costs and constraints in price reduction. The stabilization of EV prices has helped unlock pent-up demand from consumers who had planned to purchase BEV passenger cars last year but postponed their decisions in anticipation of price stabilization11/.

-

The easing of credit approval standards by financial institutions: This is evident from the credit approval index and the rebound in total passenger car sales, which rose 0.16% YoY to 154,449 units during the first 8 months of 2025 (compared to a -20.6% YoY in the same period of 2024). The improvement followed a continued decline in outstanding Non-Performing Loans (NPL) and Special Mention Loans (SML) since Q3 2024, with contractions of -18.6% YoY and -8.4% YoY, respectively, in Q2 2025. This was partly driven by the strict credit approval measures implemented earlier and ongoing initiatives by financial institutions to curb NPLs, such as debt payment holidays and debt restructuring programs12/ .

-

The launch of new BEV passenger car models: Featuring more advanced technology at affordable prices, these introductions have expanded consumer choices. During the first 9 months of 2025, the number of passenger BEV brands registered in Thailand reached 5813/, up 34.9% YoY. Newly introduced brands in 2025 include Denza (accounting for 3.3% of total passenger BEV registrations), Omoda (2.0%), and Jaecoo (2.0%).

-

Continued support from government measures: Through the EV3.5 scheme, which offers subsidies of up to THB 100,000 per BEV passenger car and related tax incentives, these measures have continued to stimulate demand by making passenger BEVs more affordable14/. At the same time, these measures also boost supply by attracting EV manufacturers to expand investment and launch promotional campaigns in Thailand.

However, BEV passenger car sales continue to face headwinds affecting consumer confidence in several areas15/. Those include: (i) after-sales service issues such as shortages of spare parts for maintenance and delays in dealer services; (ii) insurance claim issues, as some consumers are unable to claim coverage purchased through dealers or face rejection from insurers, particularly for EVs that were provided with complimentary insurance coverage under promotional programs; and (iii) financial difficulties among certain EV manufacturers, which could lead to business closures in Thailand, raising concerns among consumers about future after-sales services and software updates.

Electric buses and electric commercial vehicles (including electric pickup trucks and electric trucks)

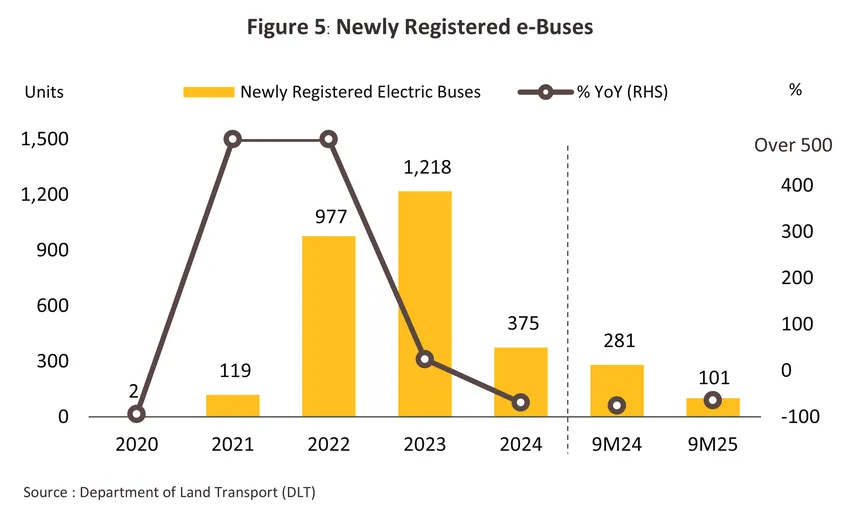

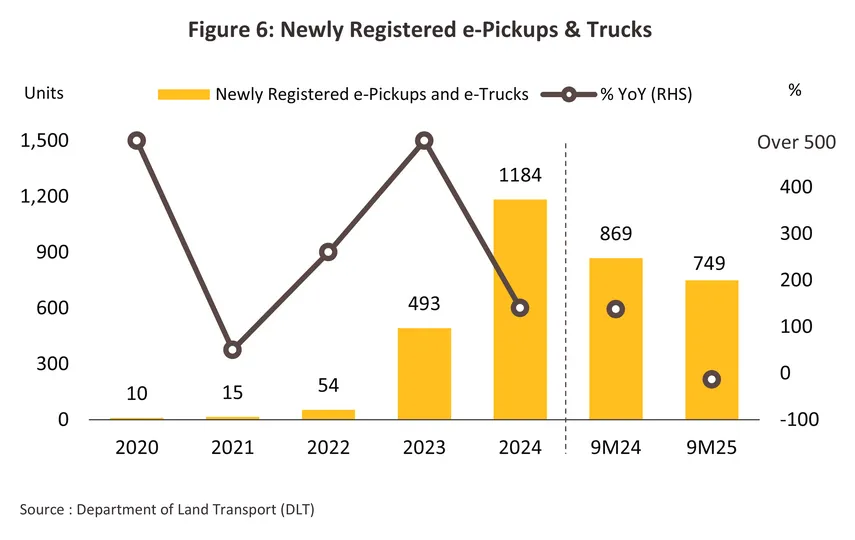

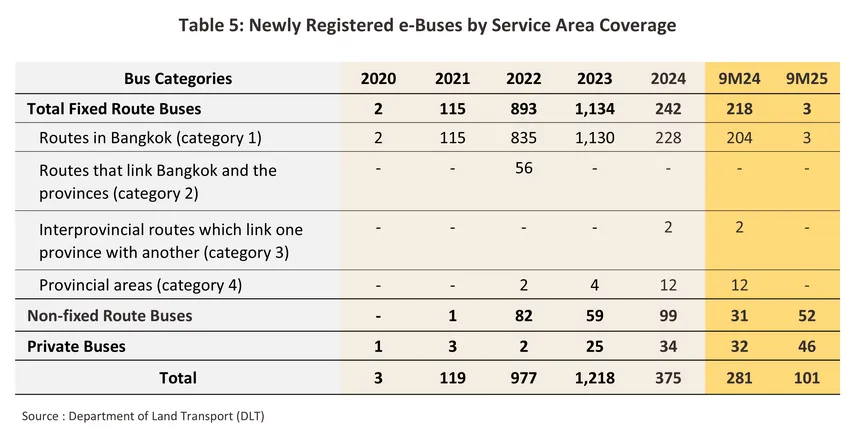

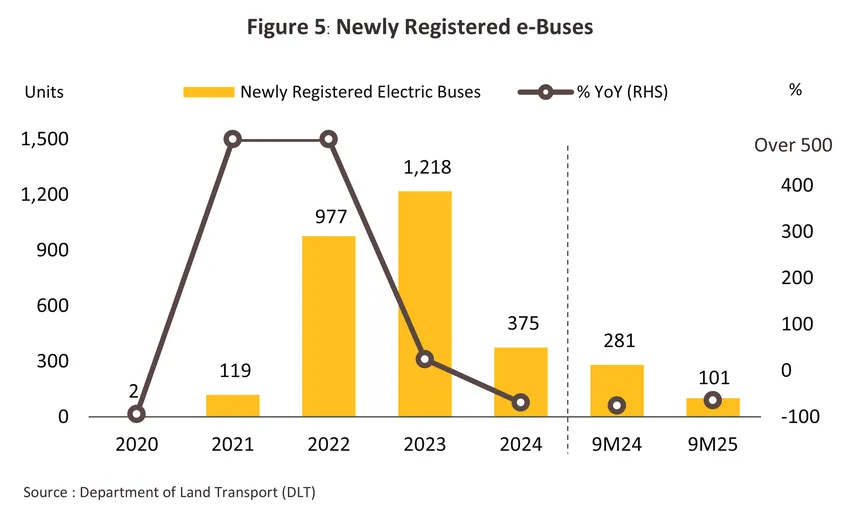

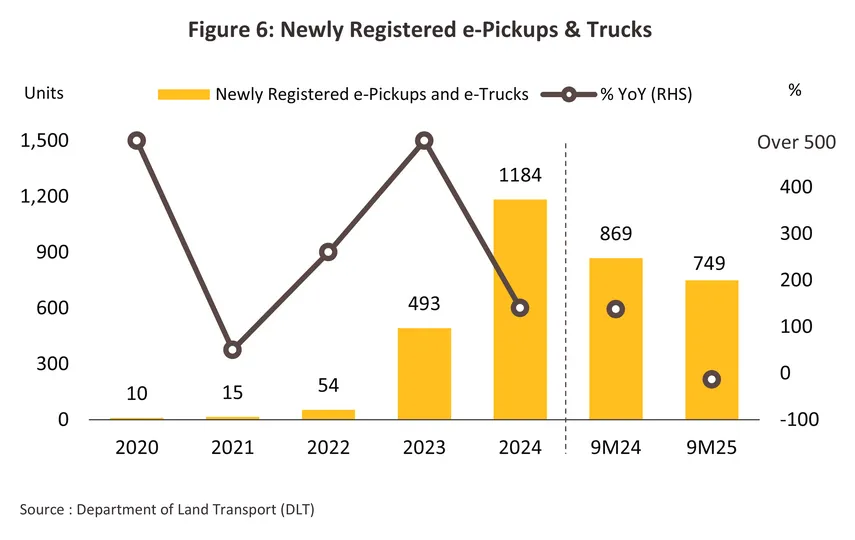

New registrations of electric buses dropped -64.1% YoY to 101 units during the first 9 months of 2025 (Figure 5), accounting for 2.9% of total new bus registrations. This comprised 55 public electric buses and 46 private electric buses. Meanwhile, electric commercial vehicles declined -13.8% YoY to 749 units (Figure 6), representing 0.7% of total new commercial vehicle registrations. Key constraints include:

-

Public investment slowdown in electric public buses: New registrations of electric public buses have continued to decline from their peak levels in 2022 and 2023, when the government accelerated deployment following the initial wave of COVID-19. In those years, electric public buses accounted for 91.4% and 93.1% of total new electric bus registrations. In the first nine months of 2025, the government further delayed investment in new electric buses for public service, resulting in a sharp -98.6% YoY drop in new registrations, down to just 3 units, or 3.0% of total new electric bus registrations.

-

High costs of vehicle and charging infrastructure: These remain key barriers for small businesses aiming to adopt electric vehicles for transporting people or goods, as the investment is still commercially unviable. For instance, an electric truck with an 800-kWh battery has a vehicle purchase cost accounting for 20–25% of its Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), compared to just 10% for a large diesel truck averaging 500 kilometers per day. Moreover, businesses investing in electric buses or commercial EVs must also install chargers and electrical systems, adding to infrastructure costs14/.

-

Driving range limitations: Battery capacity for large electric vehicles remains insufficient for long-distance commercial use, while the lack of charging stations in provincial areas further limits adoption. As a result, nearly all newly registered electric buses have been Category 1 operating only in Bangkok. Likewise, registrations of electric commercial vehicles remain concentrated in Bangkok and its vicinity, accounting for 90.0% of the total. In addition, payload restrictions continue to hinder electric trucks, as large batteries add significant weight. This makes electric trucks the slowest-growing EV segment in terms of consumer adoption compared to other types of electric vehicles16/.

However, overall electric bus registrations have benefited from the continued growth in business adoption, driven by environmental strategies aimed at achieving Net Zero. More companies have shifted from ICE buses to electric buses for employee transportation. This has resulted in a 67.7% YoY increase in registrations of non-fixed-route electric buses (mostly operated by bus rental businesses), reaching 52 units, and a 43.8% YoY increase in personal-use electric buses (mostly purchased by general businesses for internal use), totaling 46 units (Table 5).

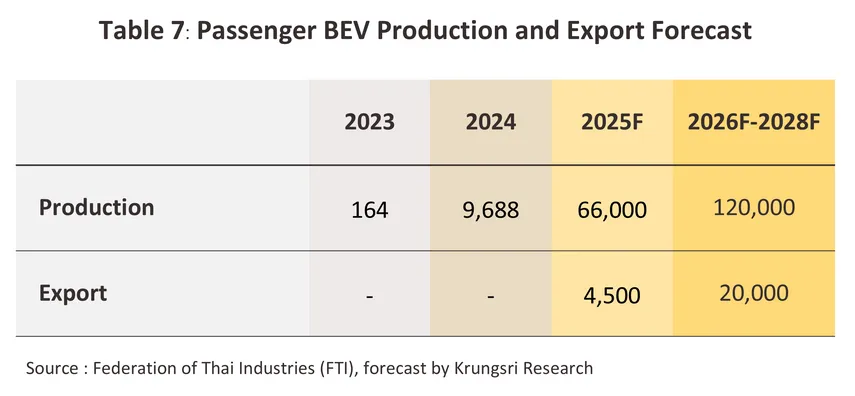

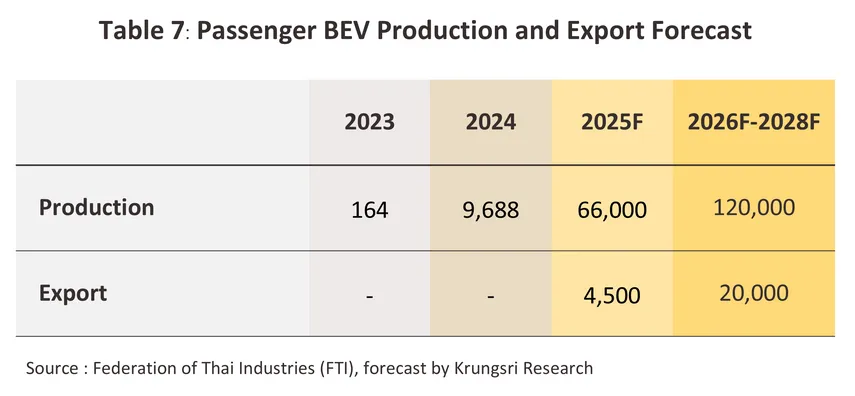

Production of passenger BEVs

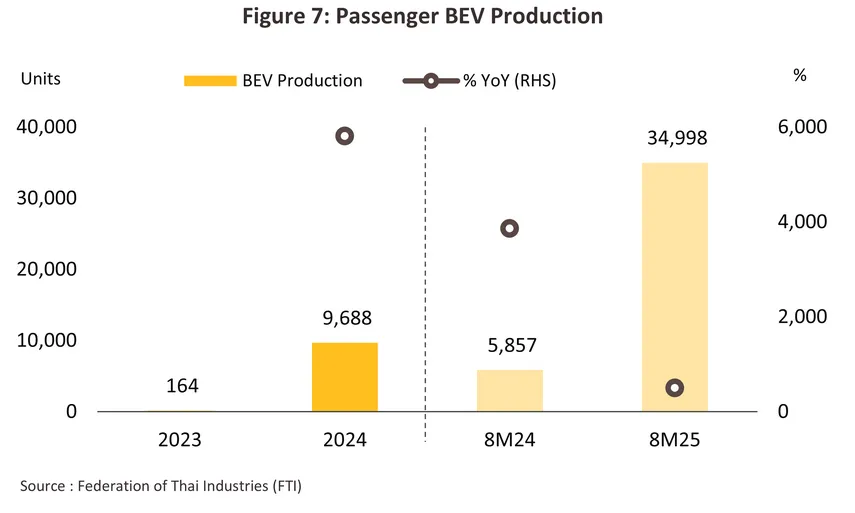

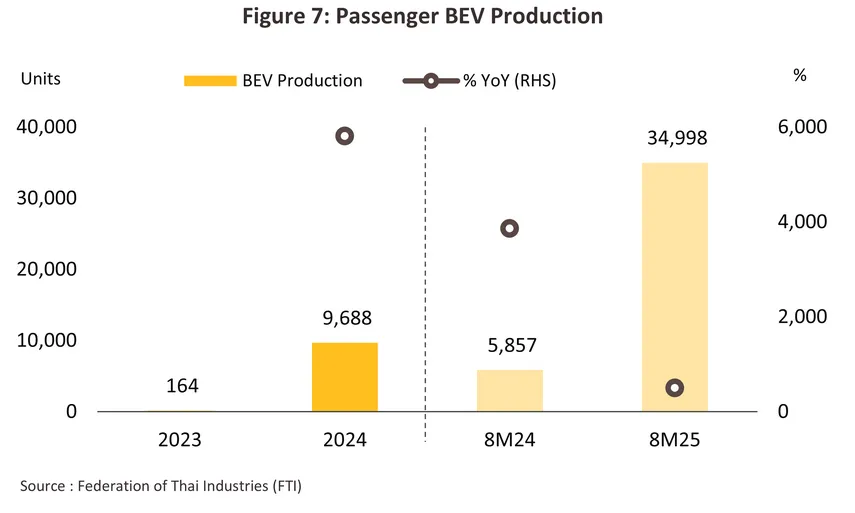

In the first 8 months of 2025, production of passenger BEVs surged 497.5% YoY to 34,998 units (Figure 7), accounting for 10.3% of total passenger vehicle production. This achievement meets the EV Board’s target of 10% by 2025 and represents approximately 12.1% of net production capacity, most of which remains focused on serving the domestic market.

The continued rise in new registrations of passenger BEVs has been driven by investment promotion in BEV manufacturing under the EV3.0 scheme, which requires EV carmakers to produce passenger BEVs at 1.5 times the volume of previously imported units (from 2022–2023) by 2025. Several companies have already started production lines17/, including MG (Q1/2024), BYD (Q2/2024), GAC AION (Q2/2024), and Changan (Q1/2025).

However, from 2024 to the first 8 months of 2025, Thailand recorded a cumulative production of 44,686 passenger BEVs, equivalent to only 0.3 times the volume of passenger BEVs imported and sold during 2022–2023 under the EV3.0 scheme. This drop is due to (i) weakened purchasing power amid the economic slowdown and a fierce price war, which pressured the BEV market, especially in 2024, when new registrations of passenger BEVs fell -10.2%, and (ii) the extension of the compensation production timeline under EV3.0, allowing EV carmakers to postpone production to 2026–2027 (approved by the EV Board on 4 December 2024), instead of the original requirement to produce 1 to 1.5 times the imported volume by 2025.

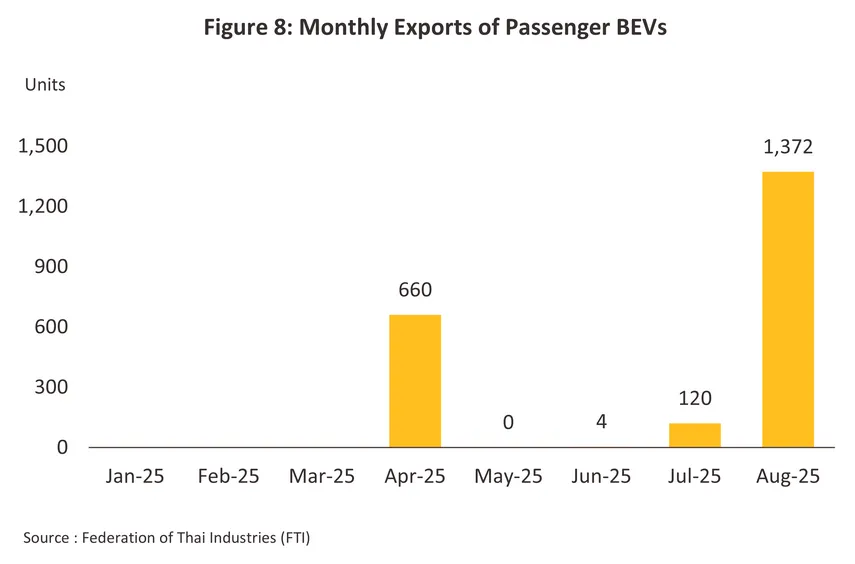

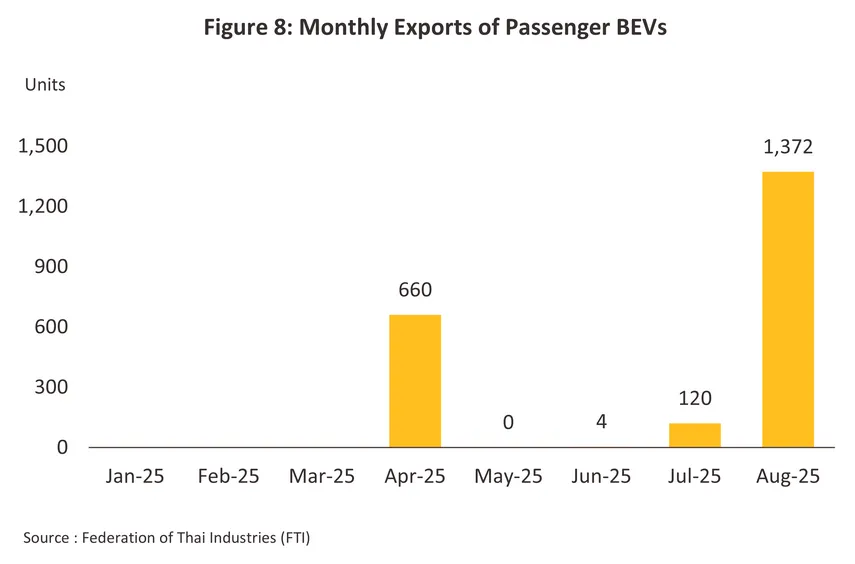

Export of passenger BEVs

In April 2025, Thailand began exporting passenger BEVs for the first time, 15 months after domestic production started under the EV3.0 scheme in January 2024. As a result, the country exported a total of 2,156 passenger BEVs during the first 8 months of 2025, accounting for 1.6% of total passenger vehicle exports and 6.2% of passenger BEV production (Figure 8). This was supported by the EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes, along with revised compensation conditions that incentivized EV manufacturers to focus more on exports. According to the EV Board’s resolution on 30 July 2025, “1 unit produced for export counts as 1.5 units” toward the compensation requirement. Consequently, passenger BEV exports in August 2025 rose to 1,372 units, up from just 120 units in July, representing 18.4% of passenger BEV production in August.

Examples of manufacturers that have recently exported passenger BEVs include BYD, which shipped 959 units of the BYD Dolphin, produced at its Rayong plant, to Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the UK18/.

In the remainder of 2025, new registrations of passenger BEVs are expected to benefit from intensified sales promotion efforts by EV carmakers to stimulate pent-up demand before the EV3.5 subsidy program ends. Meanwhile, passenger BEV production is projected to increase as manufacturers accelerate compensation production ahead of the EV3.0 deadline. Passenger BEV exports are also likely to continue expanding, supported by the incentive that “1 unit produced for export counts as 1.5 units” under the EV Board’s resolution effective from August 2025. As a result, full-year 2025 projections for passenger BEVs include 116,000 units in new registrations, 66,000 units in production, and 4,500 units in exports. In contrast, electric buses and electric commercial vehicles are expected to remain under pressure from earlier constraints, with new registrations declining to 130 and 1,050 units, respectively.

Outlook

New registrations of passenger BEVs, electric buses, and electric pickup trucks

New registrations of passenger BEVs are expected to maintain steady growth. During 2026–2028, after the EV3.5 scheme ends, new registrations of passenger BEVs are projected to average 125,000 units per year (Table 6), representing a 3.8% CAGR, supported by the following factors:

-

The launch of new models with advanced technology and longer driving ranges, particularly from Chinese automakers investing in Thailand, will be a key driver. According to the IEA (2025), continuous BEV technology development by global manufacturers will lead to an average 13.0% CAGR in new EV models (including BEVs and PHEVs) worldwide between 2024 and 2027, reaching 1,130 models by 2027 (41.7% of all new models). In contrast, new ICE models are expected to grow only 0.8% CAGR to 1,378 models (50.8%), with the remainder largely HEVs.

-

Implementation of Euro 6 standards: From 2026 onward, full enforcement of Euro 6 standards for diesel and gasoline vehicles, based on Thai Industrial Standards (TIS), aims to curb air pollution and reduce PM 2.5. This shift is expected to raise production costs and prices for ICE vehicles, especially compared to EVs.

-

The easing EV price war in Thailand: This is driven by (i) the continuous decline in net profits of BEV automakers amid the intense price competition in the previous period, and (ii) the limited scale of passenger BEV production in Thailand, which has yet to achieve economies of scale, resulting in higher unit production costs compared with Chinese passenger BEVs imported previously. These factors continue to constrain price reductions for passenger BEVs sold in Thailand, leading to a more stable price trend compared with the previous period.

However, Thailand’s passenger BEV market is expected to grow at a slower pace after the EV3.5 scheme ends, compared with the strong growth under the EV3.0 (2022-2023) and EV3.5 phases (2024-2025), when new passenger BEV registrations rose 524.2% and 30.0% CAGR, respectively. The slowdown reflects expectations that post-EV3.5 support in 2025 will offer weaker incentives than earlier phases, which required strong government measures to boost demand and build market momentum for the New S-curve industries.

New registrations of electric buses and electric commercial vehicles are projected to reach 510 and 1,600 units per year, growing at average rates of 98.1% and 24.1% CAGR, respectively, during 2026–2031, supported by the following factors:

-

Investment trend in new electric bus services: The initiative will proceed through the electric bus leasing project, approved by the Cabinet on 17 June 2025 with a budget of THB 15.355 billion, under which the BMTA will lease 1,520 electric buses over seven years. Deliveries from the winning bidders are scheduled to begin in late 202619/, which will help boost new registrations of fixed-route electric buses.

-

Launch of new electric commercial vehicles: The introduction of new models, particularly BEV 1-ton pickup trucks from leading Japanese manufacturers in Thailand20/, such as Toyota Hilux BEV and Isuzu D-Max EV—with driving ranges of 300–400 kilometers per charge, by 2025. Meanwhile, electric truck models imported into Thailand are also expected to increase, in line with the global trend, where the number of electric truck models grew at an average 28.4% CAGR during 2020–2025, reaching 335 models by 202521/. Battery development for large electric trucks will enhance energy storage, resulting in driving ranges per charge increasing at 6.3% CAGR over 2020–2025, reaching 200-310 km per charge by 202521/.

-

Declining total cost of ownership: Driven by rising battery production for electric trucks, unit costs are trending downward due to economies of scale—making commercial deployment increasingly cost-effective. According to IEA (2025), global electric truck prices are expected to drop by approximately 15–35% by 2030, with total cost of ownership approaching parity with diesel trucks used for long-haul transport.

Production and export of passenger BEVs

Passenger BEV production is expected to increase to an average of 120,000 units per year (Table 7), representing an average growth of 41.4% CAGR and accounting for 31.1% of total passenger BEV production capacity during 2026–2028, supported by several key drivers.

-

Rising offset production under the EV3.5 scheme: The cumulative registrations of passenger BEVs supported under the EV3.5 scheme are expected to reach 140,000–160,000 units during 2024–2025, approximately double the cumulative registrations under the EV3.0 scheme. Most of the previous registrations were imported and sold in Thailand, and automakers will need to compensate through domestic production under the scheme’s conditions during 2026–2027.

-

Increasing offset production ratio: During 2026–2027, EV manufacturers supported under the EV3.5 scheme will be required to offset their earlier imports by producing 2–3 times the number of BEVs previously sold. This ratio is significantly higher than the offset requirement under the earlier EV3.0 scheme, which was set at 1–1.5 times.

-

Outstanding compensatory production under the EV3.0 scheme: This stems from the EV Board’s resolution allowing manufacturers to extend the compensatory production timeline. It is estimated that around 100,000 passenger BEVs remain to be produced as compensation. However, the required production volume must be 2–3 times higher than the number of units previously imported for sale.

-

Stricter monitoring measures for compensatory production: Following the EV Board’s resolution, automakers are now required to submit production forecasts and report compensatory output to the Excise Department. The Excise Department will withhold subsidy payments if the cumulative compensatory production falls below the specified threshold.

However, domestic compensatory production of passenger BEVs may face several risks: (i) delays or production suspension in Thailand due to weak finances of some BEV makers, especially smaller ones suffering continued losses22/ amid fierce competition and recent price wars; (ii) withdrawal requests under a new rule allowing manufacturers yet to receive subsidies to refund excise tax differences instead of producing compensatory units; and (iii) global supply chain disruptions from China’s export controls on rare earths, which could particularly impact EV production as it uses about twice as many rare earth elements as ICE vehicles23/.

Passenger BEV exports are expected to rise to around 20,000 units per year during 2026–2028, supported by:

-

The regulation “Each passenger BEV produced for export counts as 1.5 units of compensatory production”: taking effect from 2025 onward, it is expected to prompt BEV manufacturers to prioritize exports. This is driven by the substantial outstanding compensatory production under the EV3.0 scheme and the increased compensatory rates under EV3.5, enabling them to fulfill their compensatory obligations within the stipulated timeframe.

-

Continuous growth in global EV demand: According to the IEA (2025), global EV demand is projected to grow at an average rate of 15% CAGR during 2024–2030. The share of EV sales is expected to increase from 14% of total car sales in 2024 to 39% in 2030.

-

Indirect impact from trade barriers on China-made EVs: Trade barriers imposed by China’s partners—such as Mexico, Brazil, and Europe—may create an opportunity for Thailand to serve as a production base for passenger BEVs targeting markets that restrict Chinese imports.

-

Stricter environmental standards in certain countries: For example, the European Union’s new CO2 emission regulations, effective from 2025, are expected to drive demand for small passenger BEVs in EU16/.

-

Continuous decline in global battery prices: Prices are expected to fall to USD 80 per kilowatt-hour24/ by 2026, around half the cost in 2023, supporting a shift toward cost parity between BEV passenger cars and ICE vehicles without government subsidies.

However, export market expansion may face significant competitive challenges, particularly from BEVs produced in China, which are expected to offload excess supply to global markets amid U.S. tariff pressures and a slowdown in domestic demand in China. Meanwhile, most BEV exports from Thailand rely on production under support schemes, with higher per-unit costs from small volumes, keeping them comparatively less competitive internationally.

1/In addition, a measure introduced in 2019 to accelerate EV production allowed applicants seeking investment promotion for Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) manufacturingto also apply for Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV) support, with applications due by December 31, 2019. Under BOI conditions, HEV production must begin within three years of receiving the promotion certificate, followed by BEV production within three years from the HEV start date.

2/Further details can be found in Industry Outlook 2024-2026: Electric Vehicle Industry, pages 5 and 6.

3/Specifications of different EV types are shown in Box 1 on page 4 of Industry Outlook 2024-2026: Electric Vehicle Industry

4/Specifications of different EV types are shown in Box 1 on page 4 of Industry Outlook 2024-2026: Electric Vehicle Industry

5/Source: Office of the Prime Minister (July 30, 2025) and Prachachat Business (July 30, 2025)

6/EV3.0 participants who defer offset production to 2026 and 2027 must meet offset ratios of 2x and 3x, respectively. They are required to achieve cumulative production of at least 35% and 25% of the total offset obligation. Meanwhile, EV3.5 participants must reach cumulative offset production of at least 15% of the imported volume under the scheme within the specified timeframe.

7/Further details can be found in Industry Outlook 2025-2027: Automobile Industry, pages 6 and 7.

8/Source: Office of the Prime Minister (July 30, 2025)

9/Source: Department of Land Transport (DLT)

10/Source: EVAT

11/Further details can be found in ‘EV Price War’ Will EV Prices Drop Further or Is This the Bottom?

12/Further details can be found in Industry Outlook 2025-2027: Automobile Industry, pages 12 and 13.

13/Including brands that have received investment promotion under the EV3.0 and EV3.5 schemes, as well as brands imported for sale without investment promotion incentives.

14/In 2024 (under the EV3.5 scheme), the average price of passenger BEVs sold in Thailand matched the average price of ICE passenger cars for the first time, while the average price of Chinese passenger BEVs was lower than that of ICE passenger cars (IEA, 2025).

15/Source: Prachachat Turakij (July 2, 2025) and Thansettakij (September 5, 2025).

16/Source: Global EV Outlook 2025, IEA

17/Further details can be found in Industry Outlook 2024-2026: Electric Vehicle Industry, page 16.

18/Source: Autolifethailand (August 25, 2025)

19/Source: Thai Rath (June 18, 2025) and Thansettakij (September 18, 2025)

20/Source: Autolifethailand (April 29, 2025) and Prachachat Turakij (August 23, 2025)

21/Source: ZETI Data Explorer

22/For example, NETA has already halted its contract manufacturing operations. The Excise Department is closely monitoring the situation, as the company still has 19,000 units to fulfill under the compensatory production requirement. It is unlikely to meet the target within 2025 and is expected to extend production over the next 1–2 years under the EV3.5 scheme. (Source: Krungthep Turakij (August 18, 2025))

23/Rare earth elements are used in the production of automotive components, including batteries, electric drive motors, electronic systems, fuel leak detection sensors, and brake sensors (Sources: Reuters (June 9, 2025) and MGROnline (June 18, 2025))

24/This is driven by supportive factors, including continuous technological advancements that have increased the energy density of new EV batteries, as well as declining raw material costs—particularly lithium and cobalt, which account for nearly 60% of battery costs (Source: Thansettakij (January 3, 2025))

.webp.aspx)