EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The renewable electricity (or green electricity) industry can look forward to solid growth, driven by a shift toward greater reliance on clean energy sources. Overall demand for electricity is forecast to rise by 2.5-3.5% annually over the next several years, and within this general trend, the renewables segment will see a significant expansion in opportunities that will come on the back of: (i) greater demand from commercial and industrial users seeking to enhance their competitiveness amid pressure from supply-chain partners and stricter trade regulations, especially from the EU; (ii) ongoing growth in sales of electric vehicles; and (iii) increased investment in Thailand by overseas operators of data centers, many of which aim to be powered entirely by renewables. Total green electricity generation will expand by 4.0–5.0% per year, helped by government action that will include investment incentives directed through the BOI and the specification of targets for renewables supply in the power development plans (PDPs), together with the general decline in the costs of energy technology, especially for solar cells. Challenges facing the industry will include: (i) slow progress by the government on the roll-out of the new PDP (currently under consideration) and the development of the regulatory environment required to support demand for green energy; (ii) the expected slow pace of Thai economic growth, which will tend to erode overall demand for electricity; and (iii) issues related to intermittency and the cost of renewables-generated power.

Krungsri Research view

Krungsri Research sees the market for renewables developing in the following directions.

Renewables generators: Revenue will track upwards thanks to government support including investment incentives (e.g., tax breaks offered by the BOI) and renewable-energy purchase targets, which will support long-term growth in turnover. However, the industry will face limitations and uncertainties from supply constraints including variability in solar insolation, wind power density, and the availability of biomass and biogas, which may affect overall power generation. In some areas, inadequate infrastructure and limited access to transmission lines may also delay the connection of generating facilities to the grid. Major corporations will be able to leverage economies of scale to lower marginal costs, and this will ease access to sources of financing and help to fund the development of new technology, including energy storage facilities. Nevertheless, major projects can be extremely capital intensive, and developers will be exposed to potential changes in energy policy. SME developers will not need access to financing on the same scale, but they will face higher risks related to liquidity and technology, while their inability to exploit economies of scale will mean that their marginal profits will be narrower.

Overview

Domestic electricity generation and distribution

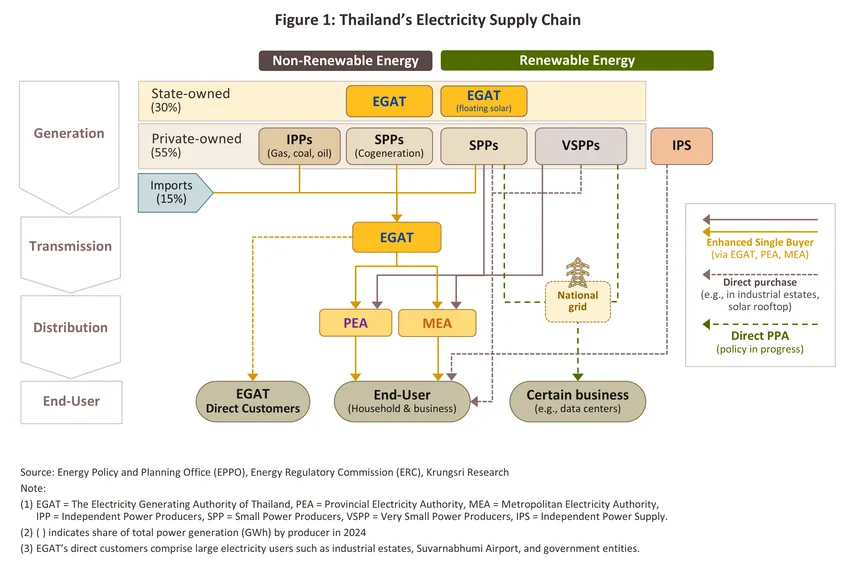

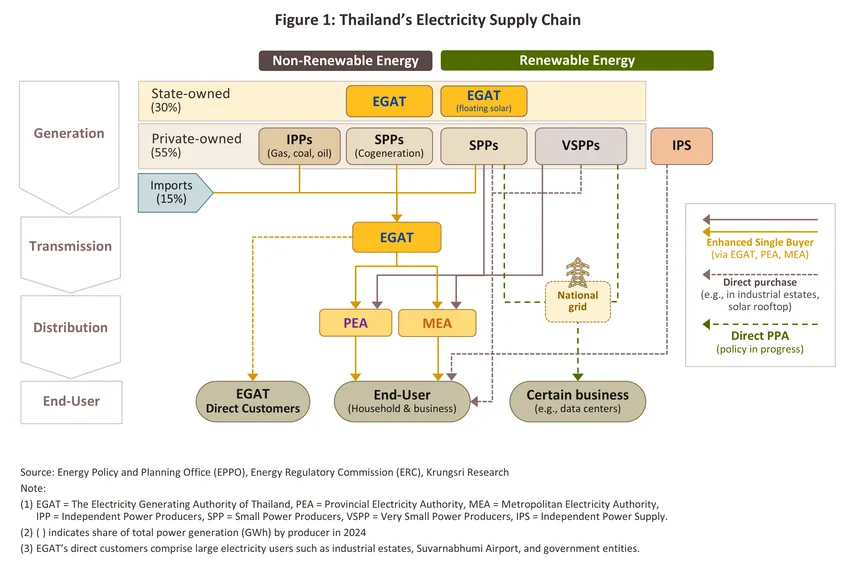

The Thai energy market is based on an ‘enhanced single buyer’ (ESB) model. Under this, the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) is responsible for supplying power to the grid, though in addition to generating electricity itself, EGAT also purchases power from ‘independent power producers’1/ (IPPs) and ‘small power producers’2/ (SPPs), which is then supplemented by imports from Lao PDR and Malaysia. The Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) and the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) also source electricity from ‘very small power producers’3/ (VSPPs). EGAT has a monopoly on transmission lines, while MEA and PEA are tasked with distributing power to end users across the country.

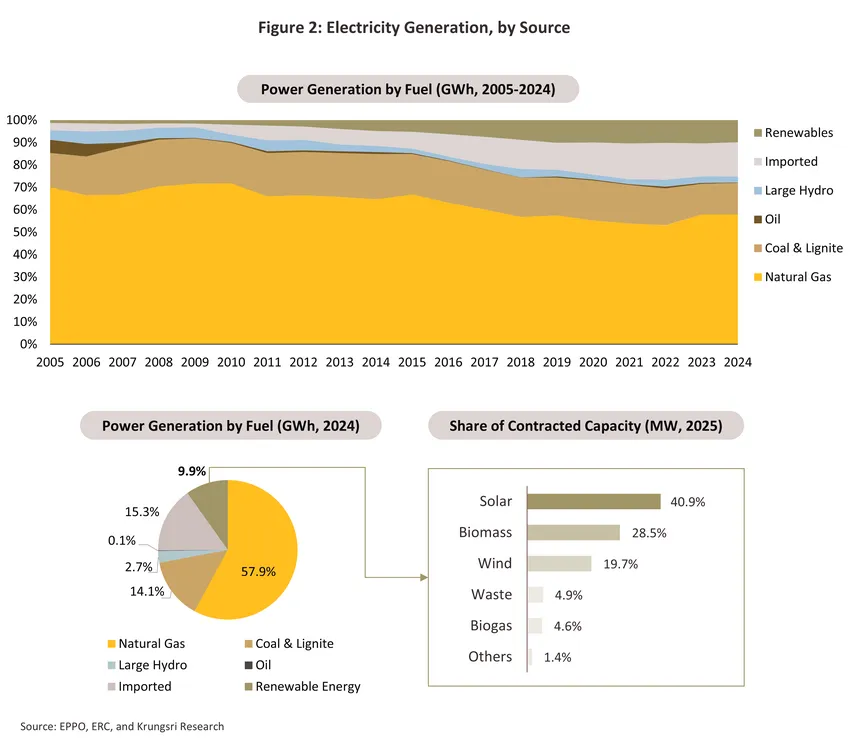

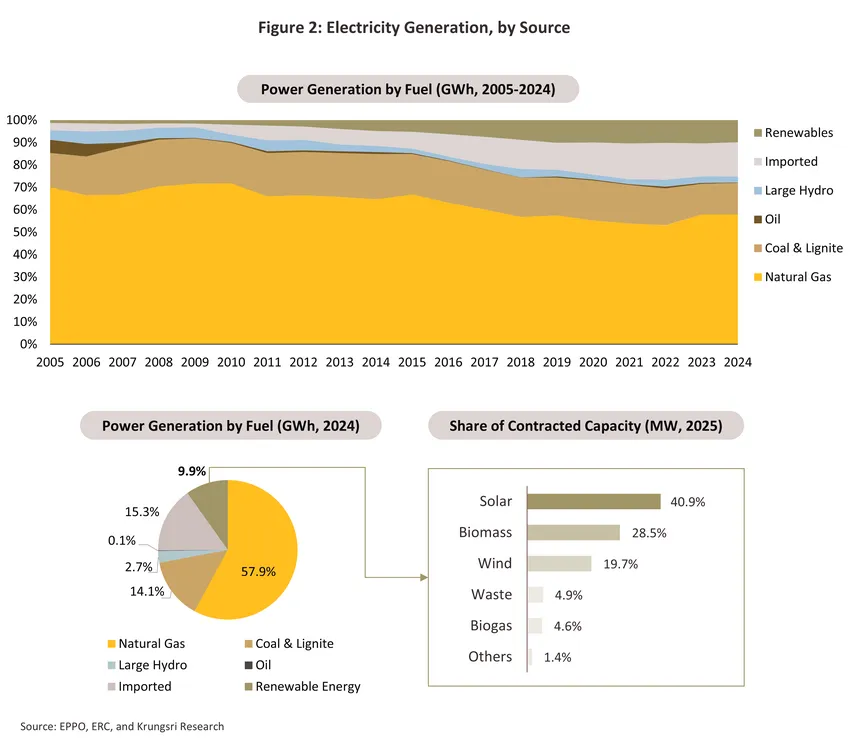

The majority of domestic supply comes from IPPs, which typically distribute power generated from fossil fuels. The most important of these is natural gas (the source of 57.9% of all electricity supplied to the grid), followed by coal/lignite (14.1% of supply) and oil (0.1%). However, the share of power coming from fossil fuels is trending downwards and in line with global shifts, Thailand’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are leading to an increase in supply from renewables. Thus, as of 2024, 10% of power supplied to the grid came from renewables, a doubling from 2015’s level. Almost 70% of this was from solar and biomass (Figure 2).

Renewables supply is largely in the hands of SPPs and VSPPs, which is then bought either by: (i) EGAT, MEA or PEA at prices specified in the feed-in tariff (FiT)4/; or (ii) industrial and commercial end users in specified locations, such as industrial estates. Independent power suppliers (IPSs) may also generate electricity for use themselves (e.g., via rooftop solar installations) and in 2026, the authorities are expected to allow providers to agree ‘direct power purchase agreements’ (direct PPAs) for the supply of renewables power to commercial end users (e.g., data centers). This will be enabled through third-party access (TPA) to the national grid.

Types of renewables

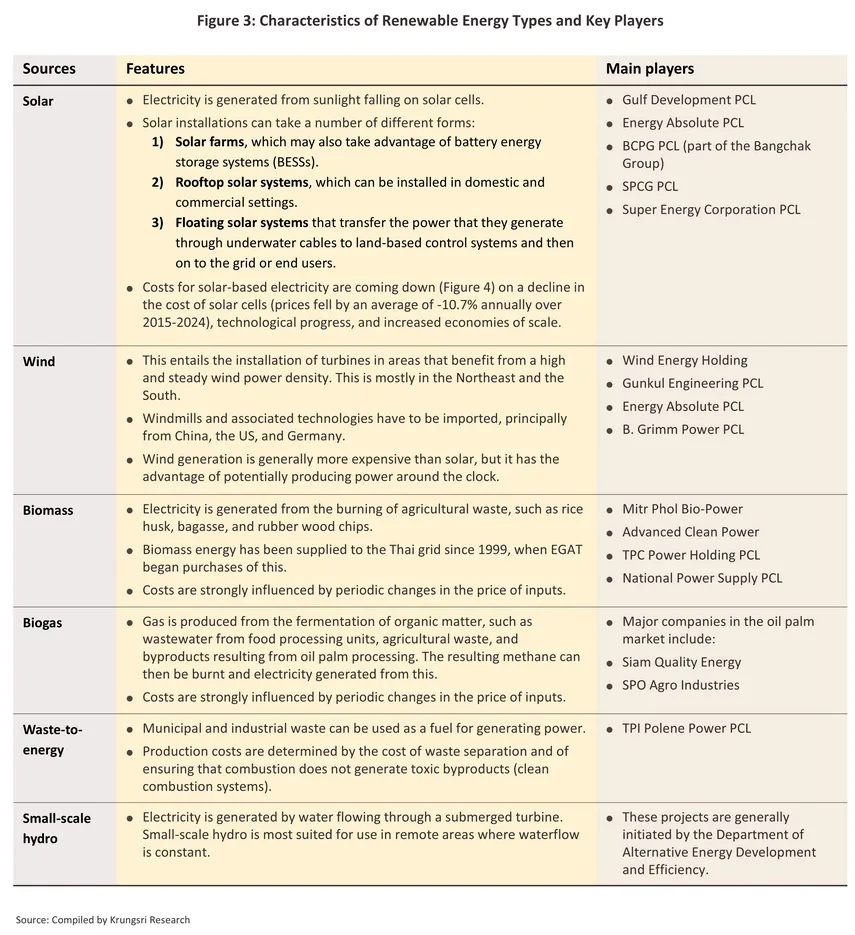

The major renewables technologies deployed in Thailand encompass solar, wind, biomass, biogas, waste-to-energy and small-scale hydro. The core characteristics of these are described below, along with the major players active within each segment.

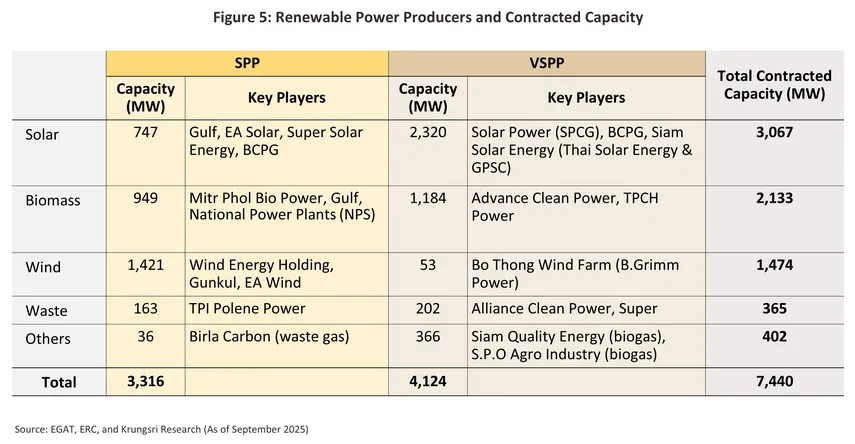

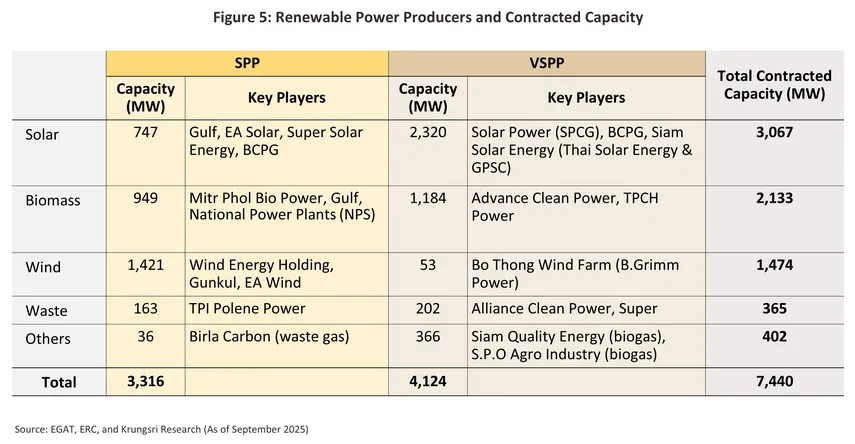

69.4% of Thai renewables capacity comes from solar and biomass, and over two-thirds of this is from VSPPs. A further 19.7% comes from wind, though due to its higher investment overheads, this is mostly produced by SPPs. Biogas, waste-to-energy, small-scale hydro and other sources of renewables account for the remaining 10.9% of contracted capacity (Figure 5).

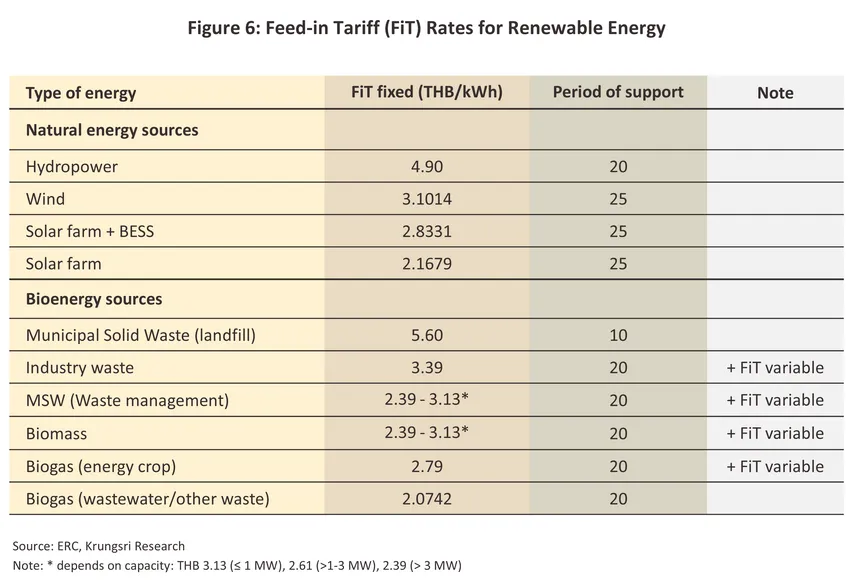

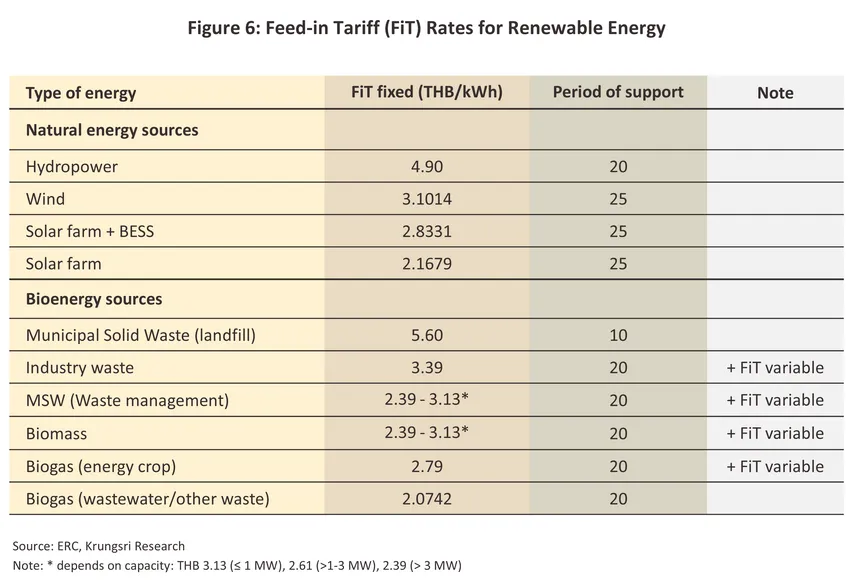

The three state bodies responsible for purchasing electricity from private-sector suppliers (EGAT, MEA and PEA) do so at varying rates according to the costs associated with each generating technology. Some contracts still operate under the old Adder system, but most purchases are now made under the Feed-in Tariff (FiT), of which there are two components. (i) The fixed FiT is calculated on the basis of the costs associated with the construction of a generating facility together with overheads relating to operations and maintenance. This will thus vary according to differences in the underlying means of generation, though the FiT will be fixed across the lifetime of the facility. (ii) The variable FiT, by contrast, is calculated on the basis of the costs of the inputs or fuels used to generate the electricity, which will naturally vary with time (these are based on average core inflation across the previous year)5/, though because suppliers generating power from natural sources like solar and wind have free access to these, they face no associated fuel costs. At present, solar is the cheapest natural energy source; the current THB 2.17 per kWh (or per unit) is less than half of both 2015’s THB 5.66/unit for solar and current hydro costs. At THB 3.1/unit, wind power is also nearly half of its 2015 cost of THB 6.06/unit. Depending on the fuel type, the fixed FiT component for power generated from bioenergy sources is in the range of THB 2.0-5.6/unit, with an additional variable component (Figure 6).

Situation

-

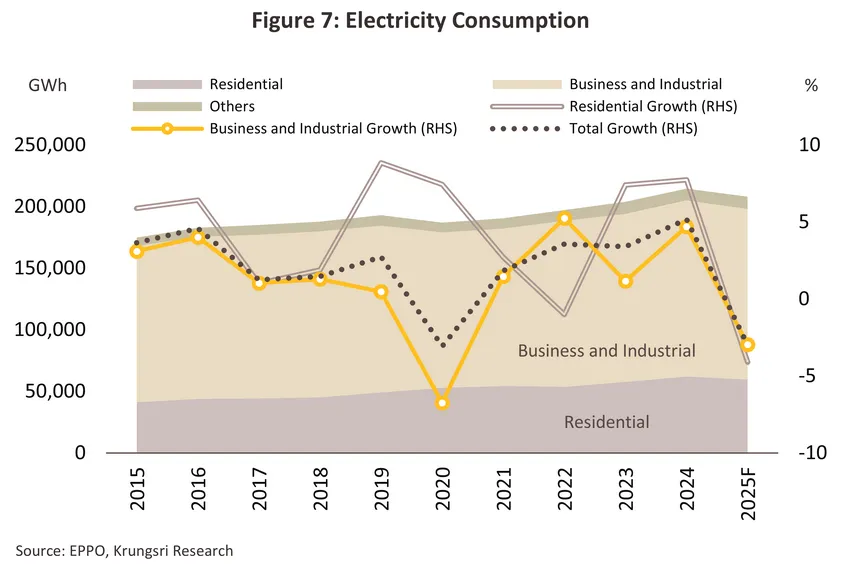

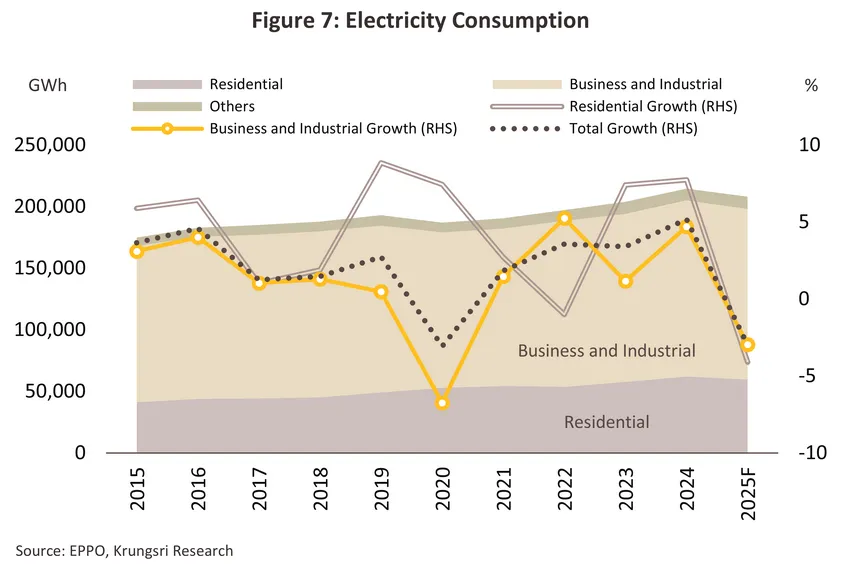

In 2025, Krungsri Research sees overall demand for electricity slipping by between -2.5% and -3.5% to somewhere between 206,963 GWh and 209,107 GWh (or million units). This is a result of sluggish economic conditions and high household debt, which are encouraging consumers to spend more cautiously, as well as cooler weather (the average temperature from January to October was 27.9 °C, down -1 °C YoY). Demand for electricity over the first 9 months of the year contracted -3.3% YoY, split between declines of -2.9% YoY for industrial users (66.5% of demand) and -5.7% YoY for households (29.0% of demand). In response, the government cut prices for domestic users, which thus fell from THB 4.15/unit for January-April to THB 3.94/unit for September-December, and added to incentives encouraging the installation of solar cells by households and companies. These include offering buy-back prices fixed at THB 2.2/unit for 10 years to household suppliers, tax deductions to a maximum of THB 200,000 (for residential installations made over 2025-2027), and special financing schemes provided by financial institutions. This has then helped to encourage some consumers to cut long-term expenditure by turning to solar power, and so more generally, solar is increasingly seen as a viable option among the commercial and household sectors (Figure 7).

-

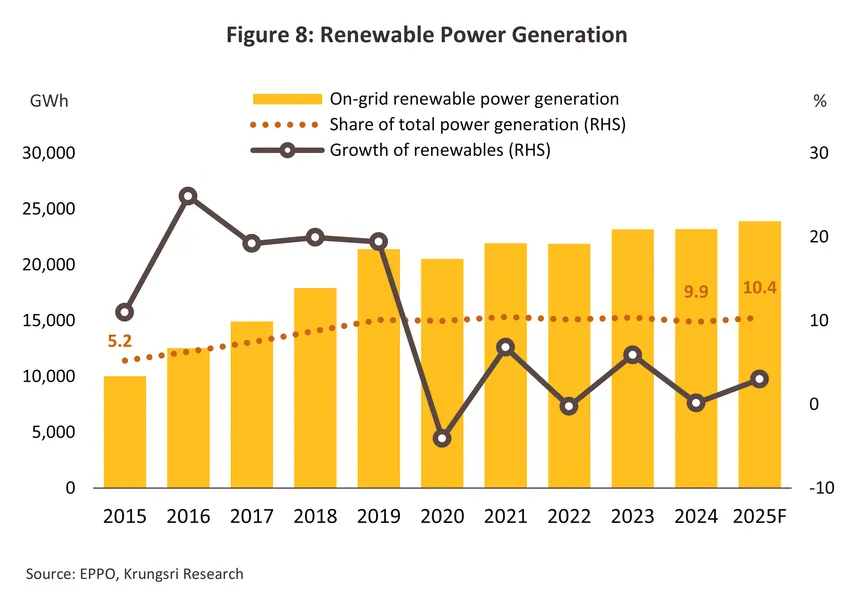

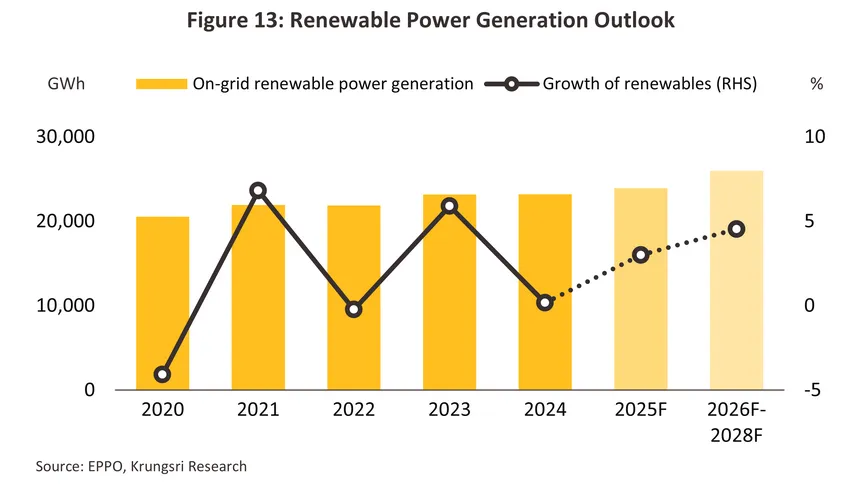

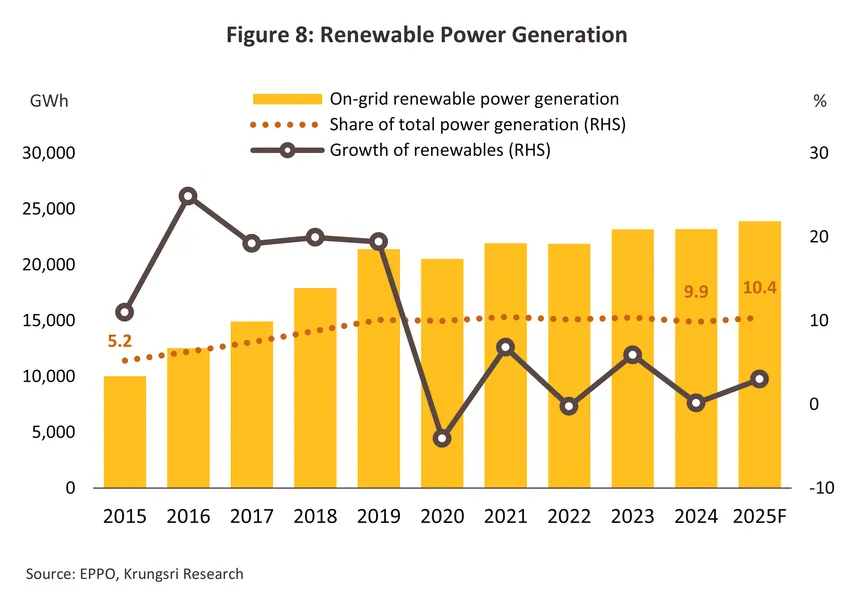

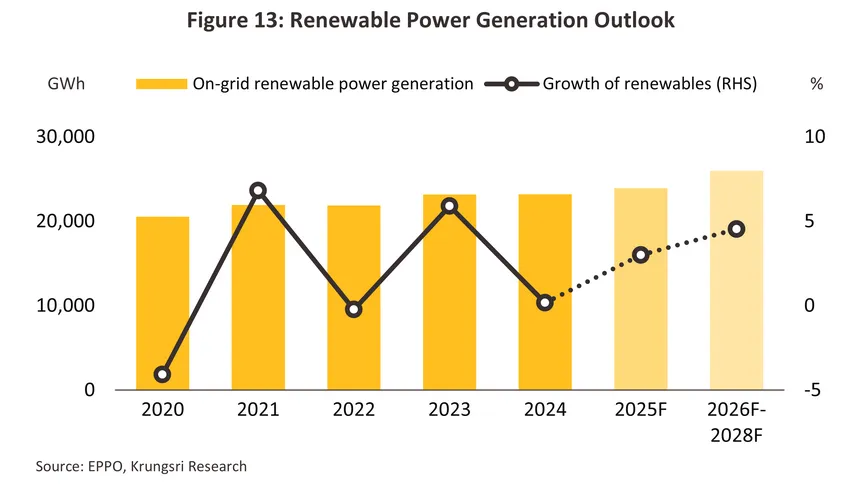

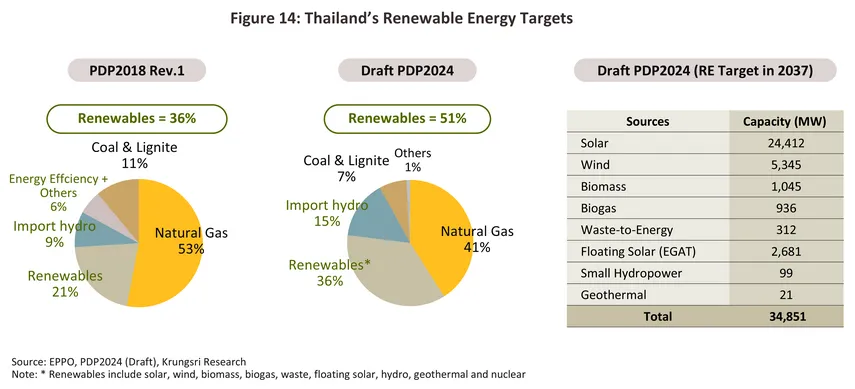

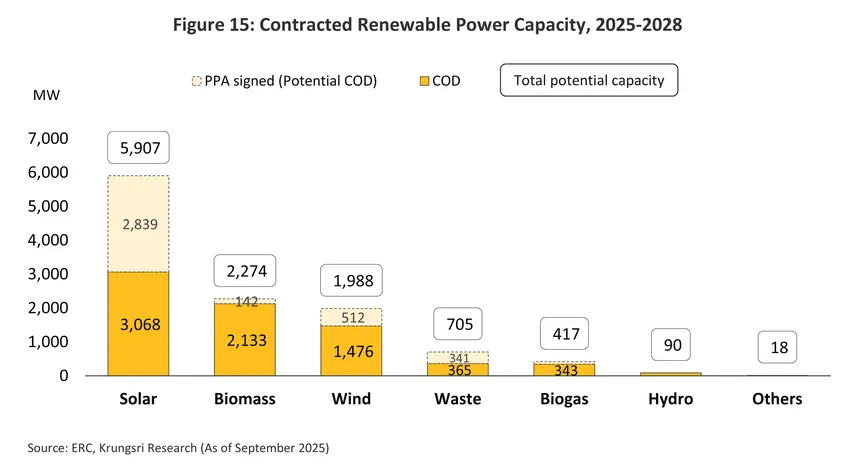

Total supply to the grid from renewables continues to trend upwards (Figure 8) and so in 2024, this came to 23,204 million units. Over the first 9 months of 2025, supply increased 3.1% YoY to 18,102 million units, and for the year as a whole, this is expected to reach 23,900 million units (+3.0% YoY). Supply will be lifted by new capacity coming on-stream as per CODs6/ that includes, for example, 354.3 MW of power from 7 new solar plants operated by Gulf Energy Development and 57.3 MW from another 10 solar projects run by Absolute Clean Energy. This is in keeping with government efforts to increase the contribution of renewables to national power supply, and these targets are reflected in the draft 2024 Power Development Plan’s (PDP2024) goal of raising this to 51% of supply by 2037 (originally set at 36% in PDP2018 Rev.1).

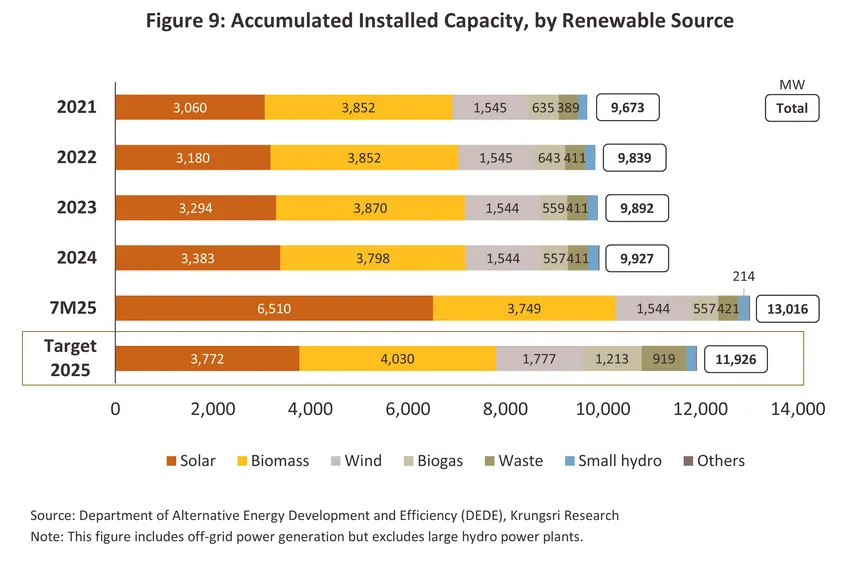

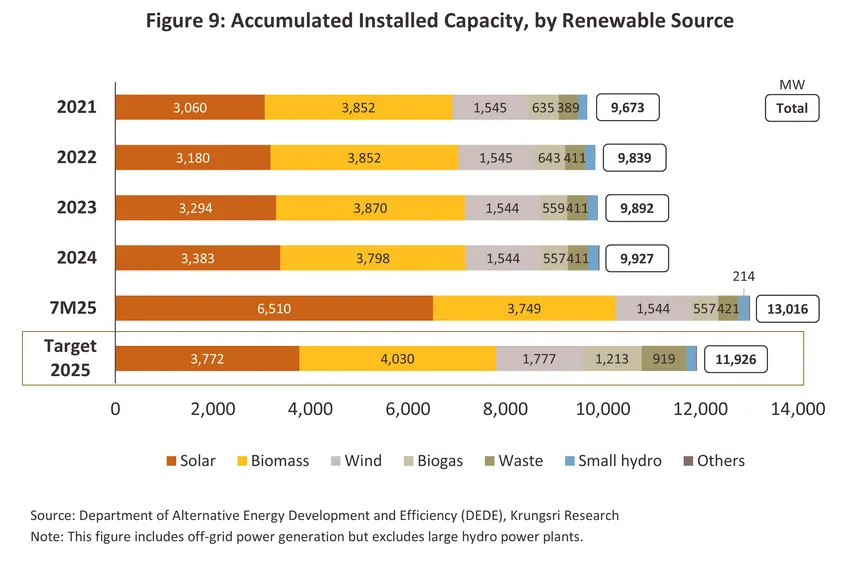

In 2025, solar power generation is showing significant growth, reflected in the cumulative installed capacity (as of July 2025) of 6,510 MW, up 92.5% from the end of 2024, accounting for half of all installed renewables capacity. Growth is being driven by purchases of solar-powered electricity from VSPPs, which began in 2021, as well as by the buy-back scheme allowing owners of domestic and commercial rooftop solar installations to sell surplus electricity back into the grid. Next in importance in the national energy mix is biomass (28.8% of installed capacity), wind (11.9%) and other sources (9.3%). Renewables cumulative installed capacity thus currently runs to 13,016 MW7/ (+31.1% from the end of 2024), somewhat above the 2025 target of 11,926 MW and 49.1% of the 2037 target of 26,491 MW laid out in the 2018 Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP 2018) (Figure 9).

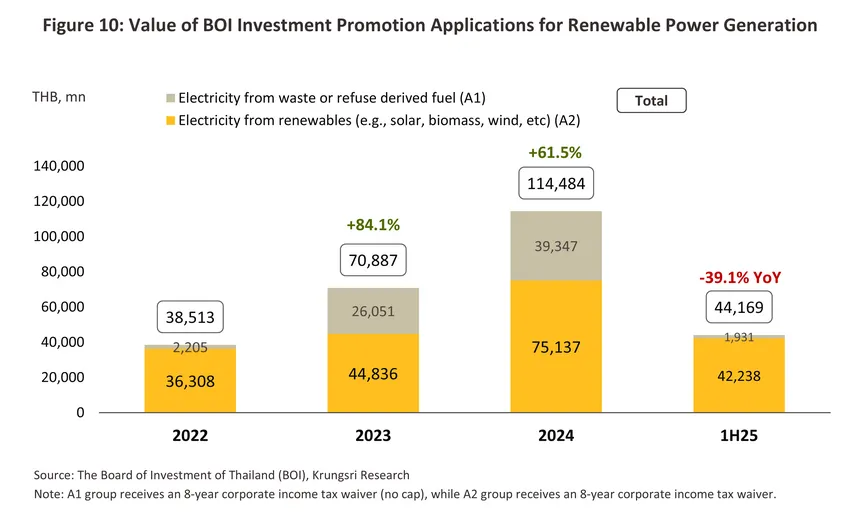

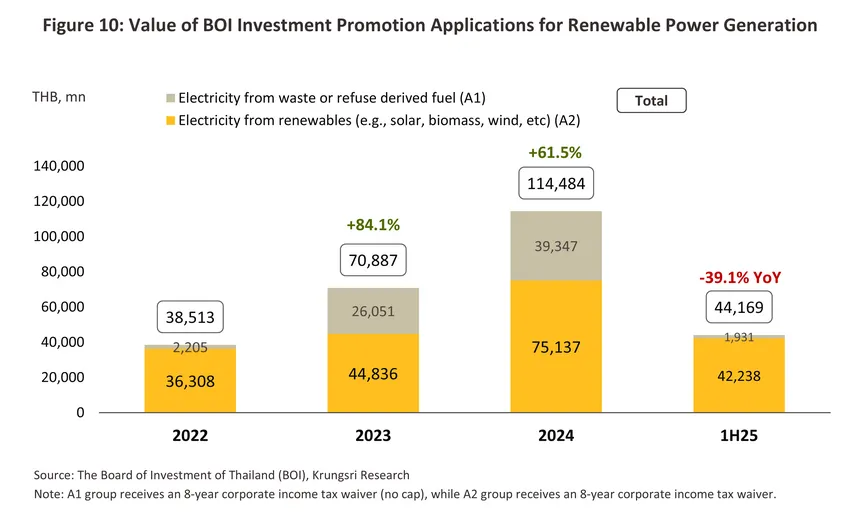

Investments in renewables have also continued to strengthen (Figure 10), partly thanks to government-backed incentives operated by the BOI that include tax waivers of up to 8 years. Thus, in 2024, 515 applications for investment support were submitted to the BOI (+15.7% from 2023), and these had a combined value of THB 114.5 billion (+61.5% from 2023)8/. In the first half of 2025, the value of applications slumped -39.1% YoY to THB 44.2 billion. This was attributable to a -93.8% YoY crash in the value of applications from waste-to-energy programs, which over the previous two years (2023 and 2024) had totaled THB 65.4 billion. By contrast, the value of applications from other types of renewables edged up 2.7% YoY. Among these were the Alpha One Project and Alpha Two Project wind plants, which had a combined value of more than THB 8 billion.

-

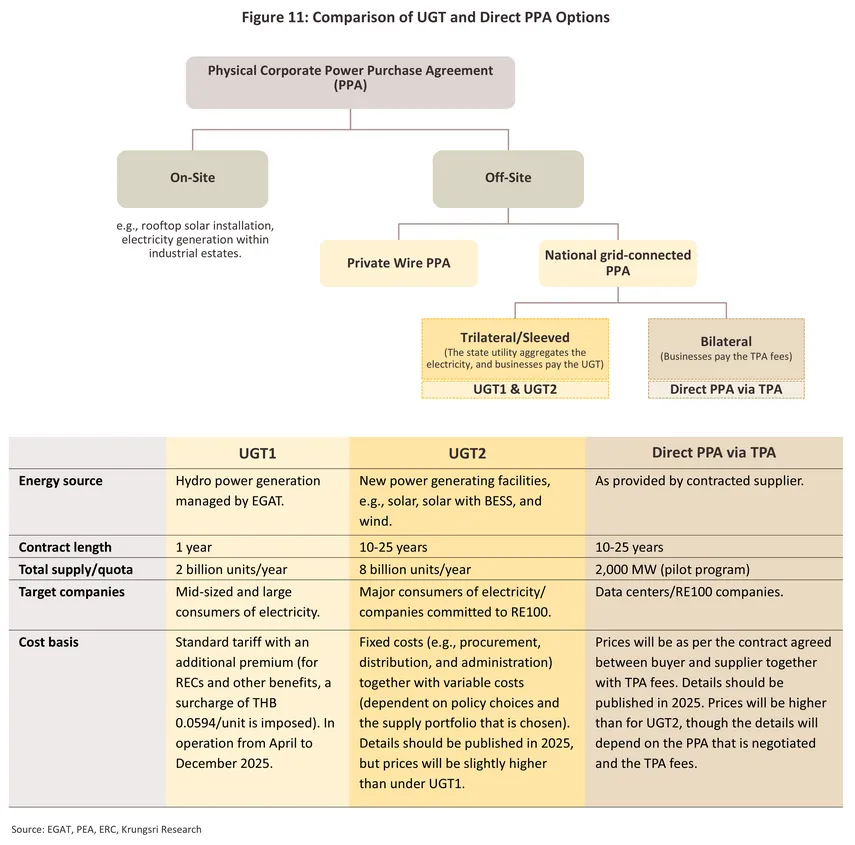

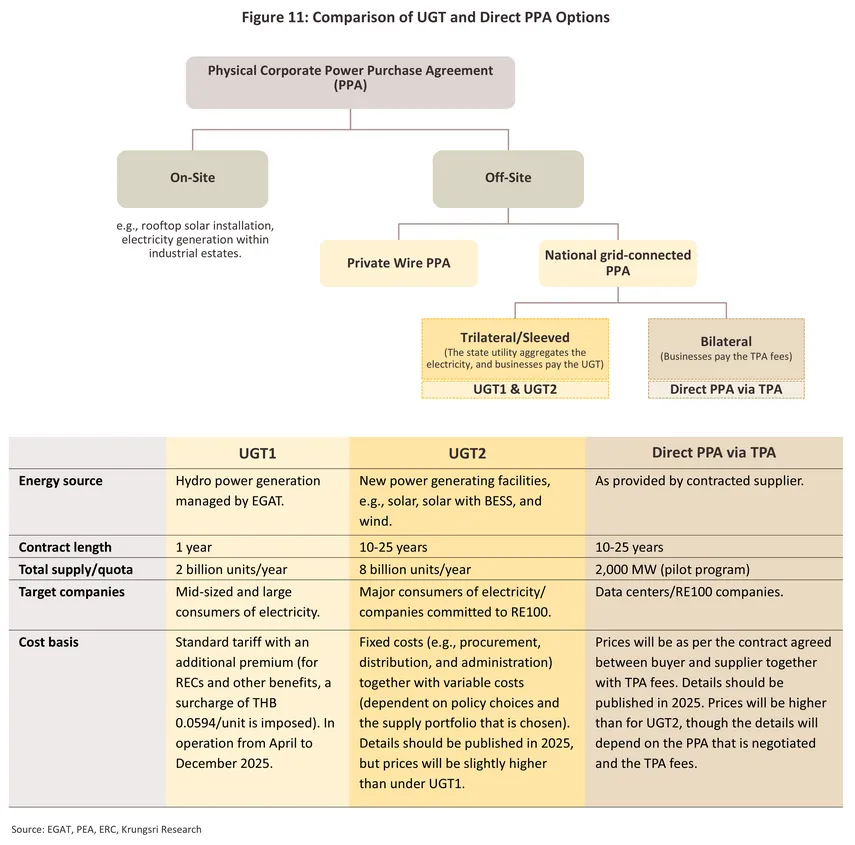

Rising demand for renewables power has prompted the government to increase purchases of clean energy. As per PDP 2018 Rev.1, the target for new installed capacity was set at 3,185 MW for 2018-2025 and 15,648 MW for 2026-2037. The government has also rolled out two tariff-setting mechanisms that provide additional options for businesses (Figure 11).

1) Utility Green Tariff (UGT): This is split between the following.

-

UGT1: This is a non-source-specific tariff (the electricity comes from hydro projects managed by the national electricity supplier) under which end users are required to pay a per-unit premium of THB 0.06, for which they are reimbursed with a renewable energy certificate (REC). Registrations for this opened on January 2, 2025, and contracts will run for 1 year, with the overall target of reaching 2 billion units annually, and it is expected that this will be sufficient to meet initial demand from the private sector. Companies joining the UGT1 scheme have included Nestlé Thai (to cover electricity supplied to 6 sites) and Siam Piwat, which draws more than 30% of its total electricity supply from renewables.

-

UGT2: This is a source-specific tariff (electricity comes from new projects, e.g., new wind and solar installations) that offers RECs targeted at major commercial consumers of electricity. Contracts must be for at least 10 years, with prices calculated on the basis of the actual generating costs for the chosen project. This is supplemented by additional charges such as those for transmission and management services. Pricing should be finalized before the end of 2025.

2) Direct Power Purchase Agreements (Direct PPAs): These involve a generating company agreeing a contract to supply renewables power directly to a customer, with this distributed through the national grid via a third-party access (TPA). Prices will be agreed in advance and will be determined by the cost of the TPA, including the connection and wheeling charges (i.e., the costs of connecting to the grid and then of using this to transmit electricity). Contracts will be for 10-25 years, and by reducing exposure to price fluctuations, confidence will be boosted among both electricity generators and buyers. Pilot direct PPAs will be targeted at particular industries, most notably data centers since these involve major upfront investments and their parent companies often have a policy of using clean energy. Initially, supply will be capped at 2,000 MW. Details are expected to be released before the end of 2025.

Outlook

Over 2026-2028, the market for renewables-based power will improve. Tailwinds will come from a combination of stronger demand for electricity, thanks to a generally improving economic outlook, and greater interest in clean sources of electricity more particularly. The latter will in turn be driven by the rising importance of sustainability as a key metric of corporate performance, which is then intensifying the competitive pressures facing Thai businesses and underscoring the importance of access to renewables as a means of appealing to overseas investors that may be looking to offshore operations to Thailand. These moves will be supported by the government, whose recognition of the importance of renewables is reflected in the draft PDP2024 and the ongoing work to prepare the physical and regulatory infrastructure required to transition to a clean-energy system. Overall, these moves fit into broader concerns with climate change and so play a central role in helping Thailand meet its commitments to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The outlook for the industry over the next three years is described below.

-

Overall electricity demand is expected to grow by 2.5-3.5% annually, in line with Thailand’s gradual economic expansion. However, demand for green electricity is projected to increase significantly during this period, driven by the following factors.

1) Demand from industry and commerce (around two-thirds of national electricity consumption) will be boosted by tighter environmental regulations in major economies (e.g., the implementation of the EU’s CBAM regulations in 2026)9/ and the increasing push to use clean energy in manufacturing processes. For Thai players, this will then add to demand for renewables as companies try to sharpen their trade competitiveness, attract investment inflows from overseas, and meet the needs of partners operating within the same supply chains.

2) Growth in electric vehicle numbers of around 11-12% annually10/ which will be driven in part by the government’s policy requiring that 30% of domestically produced automobiles be zero-emission vehicles by 2030. Naturally, the need to charge these will add to demand for electricity, and so the draft PDP2024 specifies that by 2037, around 20% of all demand for electricity will be for EVs.

3) Investments by major transnationals in Thailand-based data centers total more than THB 200 billion, and this will add an additional 6 billion units to total demand by 2030, rising to 10 billion units by 203711/. Some of the companies involved in these investments are committed to powering their operations with 100% renewables; Google and Microsoft have set a goal of achieving this by 2030, while Amazon aims to reach net zero a decade later. Moreover, some multinational corporations that operate manufacturing facilities in Thailand are also targeting 100% renewables power12/, including Nestlé and Unilever (producers of consumer goods), Continental (manufacturers of tires), and Samsung and Panasonic (electronics and electrical appliances) (Figure 12).

4) Government policies that aim to boost demand for renewables mirror global trends by setting a target of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by -47% (relative to the 2019 baseline) by 2035 and of reaching net zero by 2050. The latter has been brought forward 15 years from the earlier target of 2065, and this will help to accelerate commercial and industrial users’ transition to clean energy.

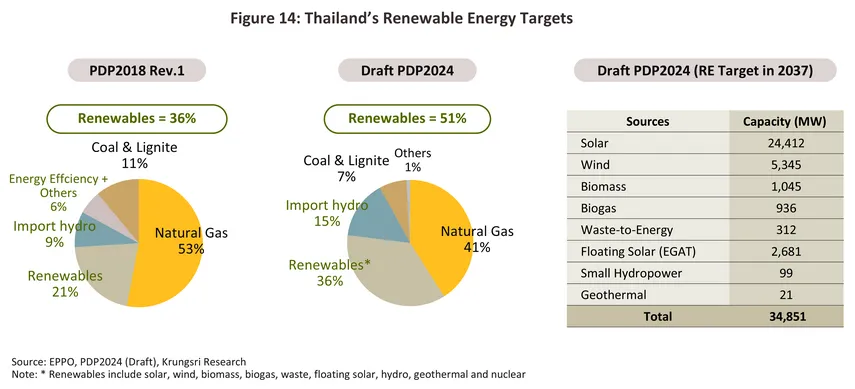

1) Government support for the development of renewables will include incentives for domestic and international investors in the industry (e.g., waivers for corporate tax for up to 8 years), buying in renewables from SPPs and VSPPs on 10-25-year contracts, and the Solar for the People program, under which the government set a target of buying 1,500 MW of power from community solar farms at a price capped at THB 2.25/unit for up to 25 years13/ and offered households a 10-year plan for selling excess power generated from rooftop solar back into the grid at prices of up to THB 2.2/unit (this began operating in 2021). The government is also supporting the emergence of new technologies by, for example, preparing the infrastructure and regulations required for the development of hydrogen power and carbon capture and storage projects. Beyond this, the new Power Development Plan (PDP) is currently being drafted (it should be formalized in 2026) and this will require that by 2037, more than 50% of national electricity generation should come from renewables, up from the 36% set in PDP2018 Rev.1 (Figure 14). The Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) further supports the transition to a sustainable and renewables-fueled future.

Most recently, the authorities have published the ‘Thailand Taxonomy’. This aims to help guide private-sector investment decisions made in multiple parts of the economy, including within the renewables sector, especially for wind and solar14/. Power plants that meet the standards in the Taxonomy will have greater access to green funding (e.g., green loans and green bonds), and in addition to strengthening a company’s competitiveness, this will also help to enhance wider perceptions of its efforts towards responsible social and environmental stewardship and its support for sustainable investments.

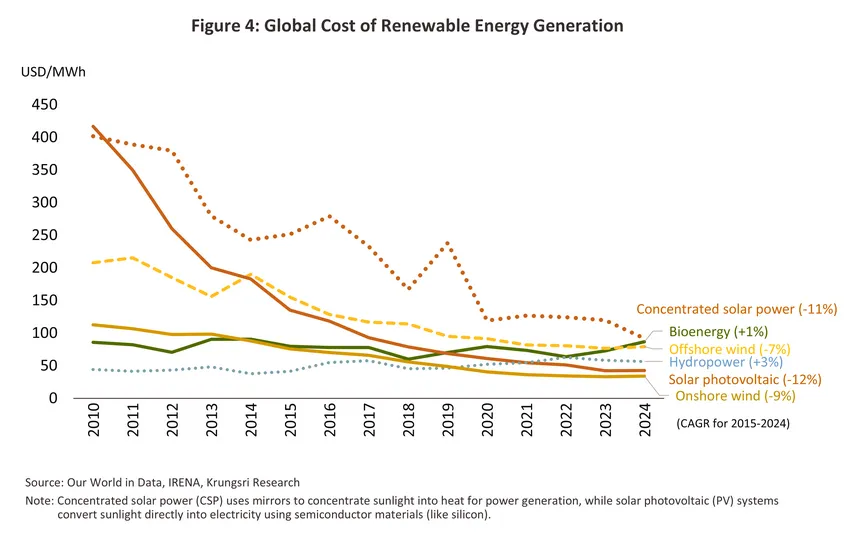

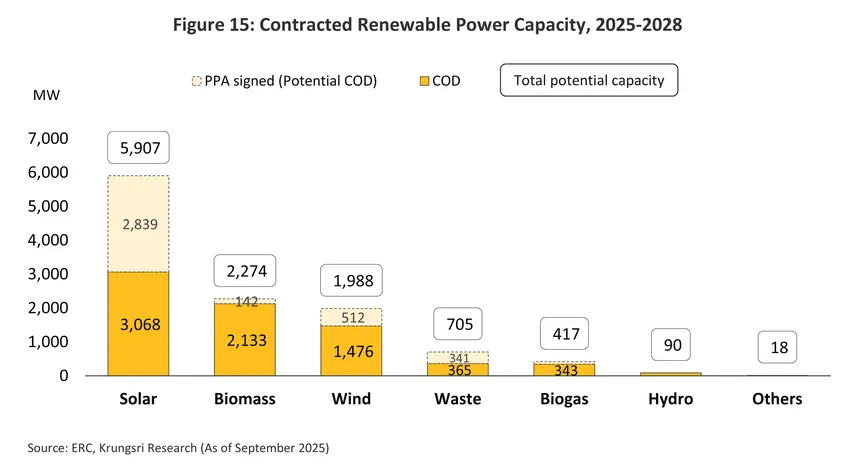

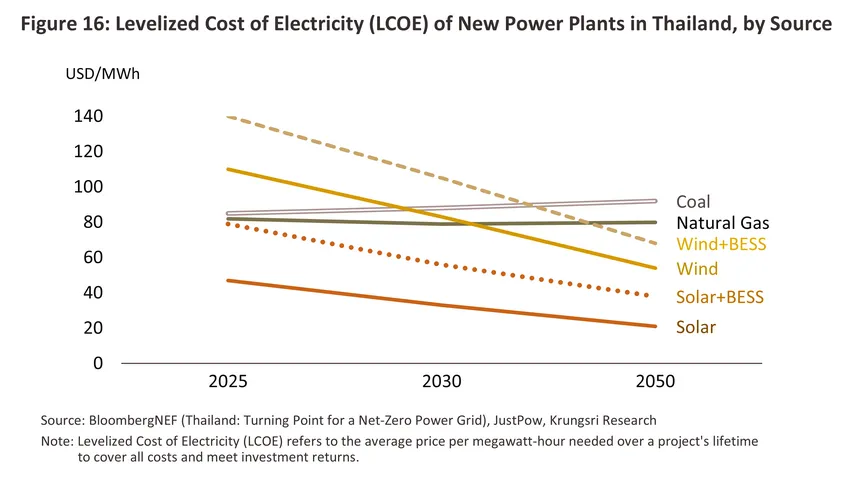

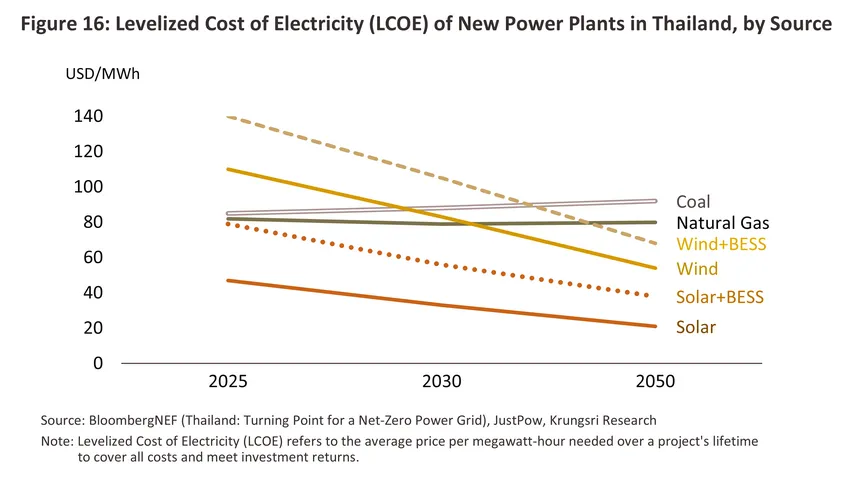

2) The costs of renewables technology have been trending downwards, and in particular, the prices for solar cells fell from THB 0.45/watt to THB 0.26/watt between 2019 and 2024 (a drop of more than -40%). The steady decline in the cost of generating power from solar will help to entrench this as the country’s renewable of choice, and indeed at present, solar accounts for 52% of all renewables power as contracted to supply the grid, with this followed in importance by biomass (20%), wind (17%) and other sources (11%)15/ (Figure 15). In addition, the costs associated with battery energy storage systems have also been declining, especially for lithium-ion batteries (down -36%, falling from USD 156/unit in 2019 to USD 100/unit in 2025). BloombergNEF thus estimates that by 2030, at USD 44-80/MWh, the Thai per-unit costs of generating electricity from battery-coupled solar will be lower than for doing so from newly constructed power stations running on natural gas. Moreover, although wind power is currently more expensive than coal or natural gas, over the long term, the falling cost of technology will shift the market balance significantly (Figure 16). As a result, electricity generation from solar and wind is becoming increasingly economical and in the future, these will likely become the most viable options for producing green electricity.

1) Delays in government policy: In particular, the new PDP is still under review (as of December 3, 2025, despite earlier expectations that it would be completed in 2024) and as a result, targets for capacity and purchases are unclear and this may disrupt investment plans. Public-sector delays are also showing up in the government’s decision to delay scheduled procurement (e.g., in May 2025, the purchase of 3,668.5 MW of fuel-free renewable energy will now be deferred until the new PDP is approved). In addition, delays to the work on improving the energy ecosystem (e.g., establishing green tariffs, launching direct PPAs, permitting peer-to-peer electricity trading, implementing smart grid systems that improve energy management processes, and deploying microgrids in local communities and in remote areas) will also hinder planning for capacity expansion and restrict private-sector access to green energy.

2) Slow growth in the Thai economy: Going forward, annual economic growth is forecast to run to just 1.5-2.5% and this will drag on total demand for electricity. The industry will also be impacted by the introduction by the US of anti-dumping measures and countervailing duties on imports of solar cells from Thailand that run in the range 375.19-972.23%16/. Unfortunately, the US absorbs 90% of exports of Thai solar cells so these measures will have significant consequences for the domestic industry, and indeed over the first 9 months of 2025, exports to the US slumped -57.3% YoY by value. Beyond this, the expanded use of US trade-restrictive policies may increase the risk that Chinese solar cell manufacturers relocate their production bases out of Thailand. This could lead to higher import prices for solar panels or delays in sourcing key equipment, such as panels and batteries, which would in turn push up the cost of generating electricity from renewable energy17/.

3) Problems with intermittency and costs: The main challenges with renewable power supply center on the natural variation in solar insolation and wind speeds, which can then lead to only intermittent and patchy generation of electricity from these. To manage these issues, suppliers need to invest in additional technologies such as battery energy storage systems and ways of managing load balancing/demand response, though this adds substantially to costs beyond installation and maintenance. Producers must also import technology from overseas, such as from China and South Korea18/, and so costs may be impacted by shifts in global markets. As a result, renewables remain at a price disadvantage relative to fossil fuels, and so while using these undoubtedly helps to address problems with ecological impacts (or energy sustainability), they remain problematic from the point of view of supply (or energy security) and cost (or energy equity), a three-legged problem that has been christened ‘the energy trilemma’.

Over the long term, answering the question of whether or when Thailand’s national energy system will transition to being primarily based on renewables will depend on progress on the twin fronts of technology and infrastructure. Generating power from solar and wind depends on access to suitable high-capacity energy storage systems that can be used to guarantee continuity of supply, while generating power from the burning of waste or biomass runs the risk of adding to problems with greenhouse gas emissions, and so this requires the simultaneous deployment of carbon capture systems (CCS/CCUS). Other sources of non-fossil-fuel power also exist, including hydrogen and small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs), and it remains to be seen how these will contribute to Thailand’s energy mix in the future.

1/ Suppliers with an installed capacity in excess of 90 MW. These facilities are typically powered by natural gas and coal.

2/ Suppliers with an installed capacity of 10-90 MW. These may be powered by either fossil fuels or renewables. Revenue comes from a combination of sales to EGAT agreed through long-term supply contracts and of purchases of electricity by industrial users in nearby locations.

3/ Suppliers with an installed capacity of less than 10 MW that are powered by renewables. Suppliers of solar, wind, and hydro power generally have a relatively high cost-base due to the need to construct and fit out power plants. For companies generating power from biomass, biogas and waste, income will be strongly influenced by access to and the prices of inputs.

4/ In 2014, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) changed the process for buying in renewables to the national grid, and in place of the Adder system, which added a premium to the electricity purchase price, offered contracts typically lasting 7-10 years, and for which participation was granted on a first-come, first-served basis, it introduced the Feed-in Tariff (FiT). Under the new system, the purchase price reflects the actual cost associated with each generating technology, with contract periods extended to 10-25 years. Participation is also now determined through competitive bidding that is supervised by the ERC.

5/ There is also a FiT premium rate for waste-to-energy, biomass, biogas, and projects in the southern border regions.

6/ The commercial operation date, or the day a power plant starts generating revenue by meeting its contractual obligations to begin delivering power to customers.

7/ Includes power not supplied to the grid, but excludes large-scale hydro.

8/ This includes electricity generating and electricity-and-steam cogenerating businesses that use sources of renewable energy such as solar, wind, biomass, biogas, and waste-to-energy.

9/ The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (EU CBAM) is currently in a transitionary phase. The measures apply imports

of cement, electricity, fertilizer, aluminium, hydrogen, and iron and steel. At present, exporters of these are required merely to inform the EU of the carbon emissions associated with any imports of these made into the EU. Full enforcement will begin on January 1, 2026, when exporters may need to pay an additional fee determined by the carbon content of their goods. Exporters, especially those of carbon-intensive products, will therefore face higher costs.

10/ Krungsri Research estimates that over 2026-2028, new registrations of BEV and PHEV autos will reach respectively 125,000 and 28,000 vehicles per year.

11/ Thailand’s cost-optimal pathway to a sustainable economy | Ember

12/ As of December 3, 2025, 446 leading global corporations have committed to RE100 (i.e., using 100% renewable energy).

13/ This is part of the government’s ‘Quick Big Win’ energy policy. This reallocates unused quotas for purchases of power from solar farms that were opened to private developers but that never reached the power purchase agreement stage.

14/ Biomass, biogas and hydro qualify as ‘green energy’ if they meet the specified criteria for cuts in greenhouse gas emissions and/or other criteria, such as for the types of feedstocks used in biogas/biomass production or the power-density requirements for hydropower plants. For further details, please see Krungsri Research’s article ‘Decoding the Thailand Taxonomy: How Classification Drives Sustainable Business’.

15/ Estimated from the contracted capacity agreed in PPAs. Typically, SPPs and VSPPs will take 1-3 years to reach their commercial operation dates (CODs) (as of September 2025).

16/ The US announced new tariffs on imports from ASEAN nations (including Cambodia, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand) on April 21, 2025,

claiming that these countries hosted Chinese-operated solar cell manufacturing facilities.

17/ China is the world’s foremost supplier of the machinery used to generate renewable power, including batteries and solar cells (the country has an 80% market share for the latter).

18/ Major Chinese and South Korean manufacturers of lithium-ion batteries include CATL BYD and LG Energy Solution.

.webp.aspx)