EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The ethanol industry is expected to grow gradually. In 2026, ethanol consumption will remain flat, or contract slightly from weak economic growth. Even so, the industry will continue to receive support from the tourism and transportation sectors. However, the situation will improve in 2027 and 2028 thanks to: (i) growth in foreign arrivals, which will lift the tourism industry, and an overall strengthening in economic activity; (ii) an increase in the number of vehicles on Thai roads running on gasohol; (iii) the growth of e-commerce and hence of delivery services, supporting further growth in the transport industry; and (iv) greater demand for ethanol from downstream industries for use in the production of sustainable aviation fuel, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and bio-plastics.

Key challenges for the industry include the rising prices of raw materials due to the impact of climate change, concerns among consumers about the ability of their cars to run on gasohol with a high-ethanol content, a lack of clarity from the government about whether E10 or E20 will be set as the standard gasohol mix, and the increasing popularity of EVs. These factors will combine to undercut demand for ethanol.

Krungsri Research view

Players that operate supply chains that are integrated from upstream production through to downstream distribution will enjoy competitive advantages, but problems securing inputs and the rising cost of these may nevertheless put pressure on profits.

-

Manufacturers producing ethanol from molasses: Income will remain flat or edge up slightly. La Niña conditions in 2025 and 2026 will boost rainfall, sugarcane yields and the supply of molasses, thereby depressing costs. The return of El Niño conditions in 2027 will make it more difficult to source inputs. Smaller independent operations will have to contend with uncertainty over access to raw materials, but ethanol distillers that are part of commercial groups that operate their own sugar mills will have more secure access to inputs and will face lower production costs.

-

Manufacturers producing ethanol from cassava: Income will also remain unchanged or strengthen somewhat. Prices will fall thanks to the impact of the La Niña on the supply of fresh casava and on inventory sizes and a decrease in demand from China (processors there are switching to domestically grown corn instead). Nevertheless, the return of an El Niño in 2027 would threaten supplies, pushing up the cost of inputs and narrowing ethanol manufacturers’ margins.

Overview

Ethanol, or ethyl alcohol, is produced either from sugary or carbohydrate-rich plants grown specifically for the purpose, or from cellulose or hemicellulose-rich plant waste that is left over from other agricultural processes. These inputs, the most common of which are sugarcane, rice, straw, corn and cassava, are fermented to produce 99.5% pure ethanol. This is then used either as a liquid fuel (directly or mixed with gasoline) or subjected to further industrial processing, for example in the manufacture of beverages or pharmaceutical products.

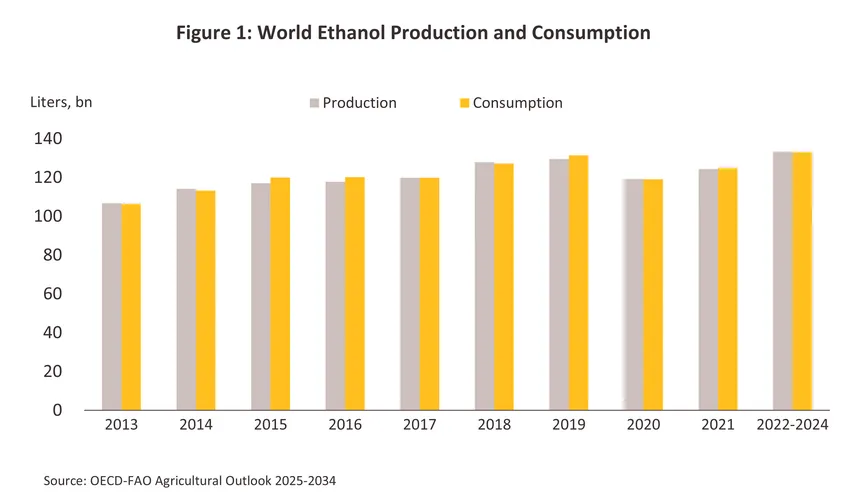

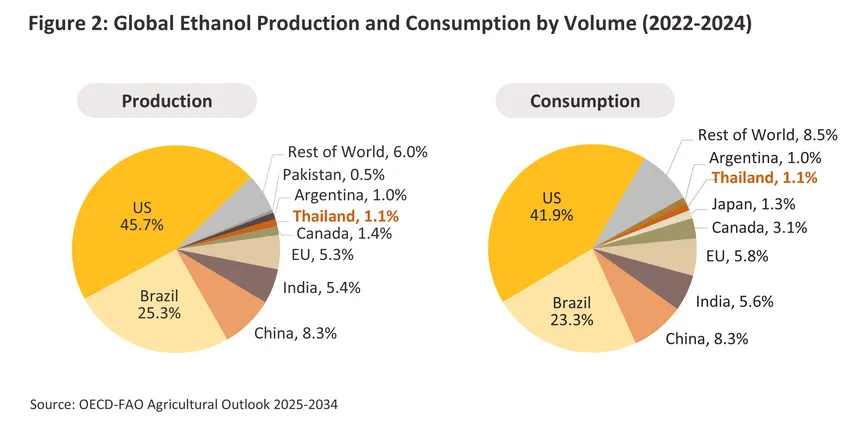

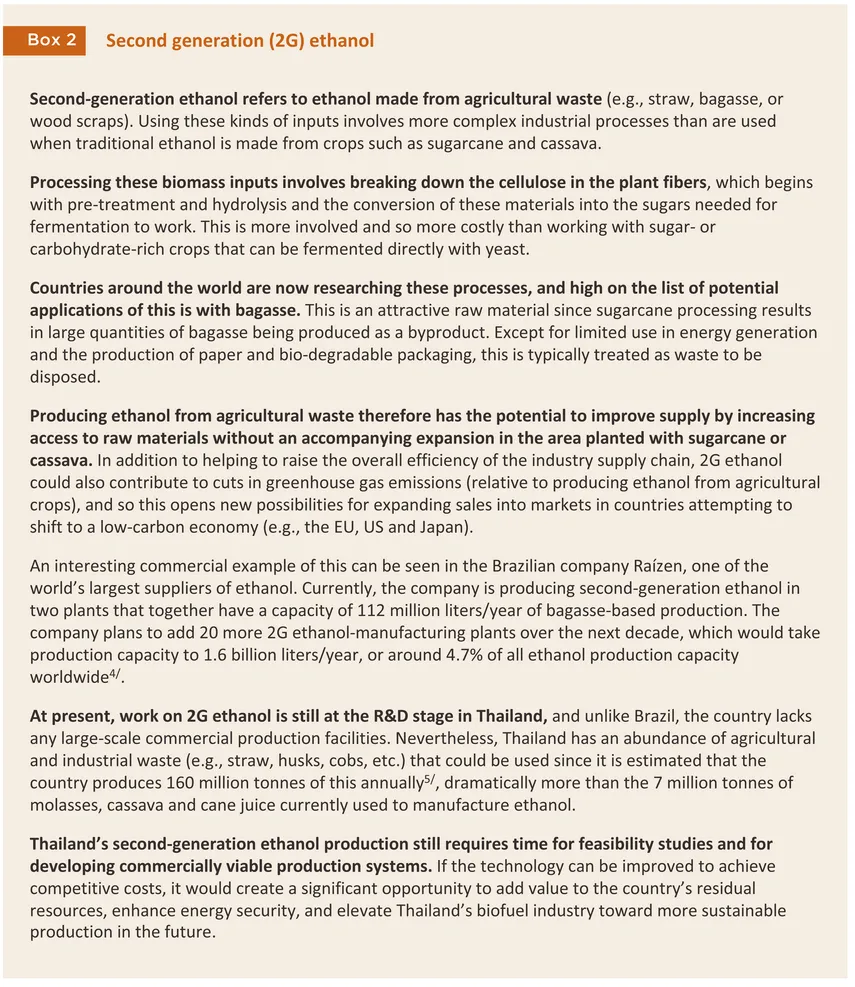

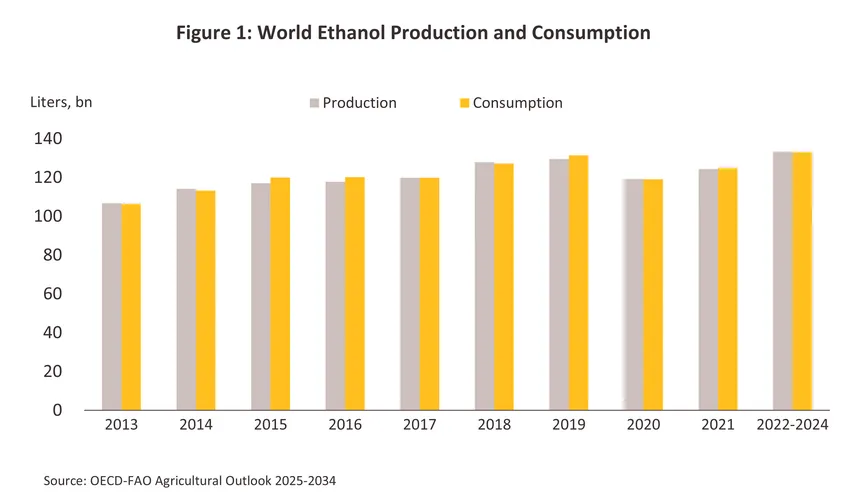

Worldwide demand for ethanol has been rising steadily, averaging 133 billion liters annually over 2022-2024 and thus slightly above its 2019 pre-Covid level of 131.4 billion liters. Demand has risen with the post-pandemic rebound in the global economy and the lift that this has given to domestic and international travel. These trends are then being compounded by helps from governments in many countries, including both direct financial support and indirect assistance in the form of mandates requiring that ethanol be mixed with regular gasoline. The latter is also part of government plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to deepen sustainability by shifting the economy to a greater reliance on biofuels (Figure 1). Globally, the largest consumers and producers of ethanol are the US, Brazil and China, which together account for around two-thirds of global production and consumption (Figure 2). These countries generally use corn and sugarcane as their primary inputs.

Thailand sits in 7th and 8th places in the world rankings of ethanol producers and consumers. The majority of domestically produced ethanol is used as a transport fuel. Since it is mixed with benzene to sell as gasohol1/, movements in the ethanol market are naturally correlated with domestic demand for liquid fuels. This is because since 2001, the authorities have required that regular petrol is mixed with 10% ethanol when sold to the public, and this then yields the gasohol 912/ and 95 that is sold on Thai forecourts. From 2008, 20% (E20) and 85% (E85) ethanol mixes have also been available, and this has helped to stoke steadily stronger demand. However, set against this is the fact that the domestic market for ethanol is tightly regulated and sales to distributors of transport fuels are subject to the provisions of the 2000 Act on Sales of Oil Fuels, while using ethanol in industrial processes is also only possible with the permission of the Liquor Distillery Organization (which operates under the oversight of the Excise Department).

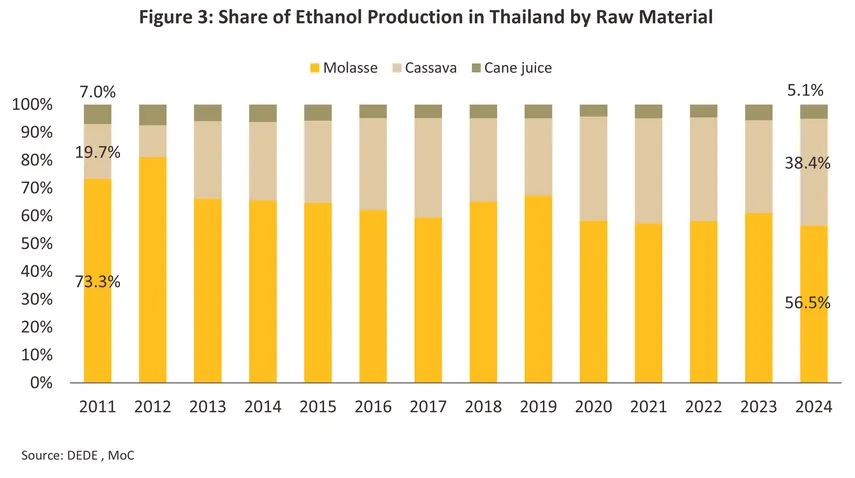

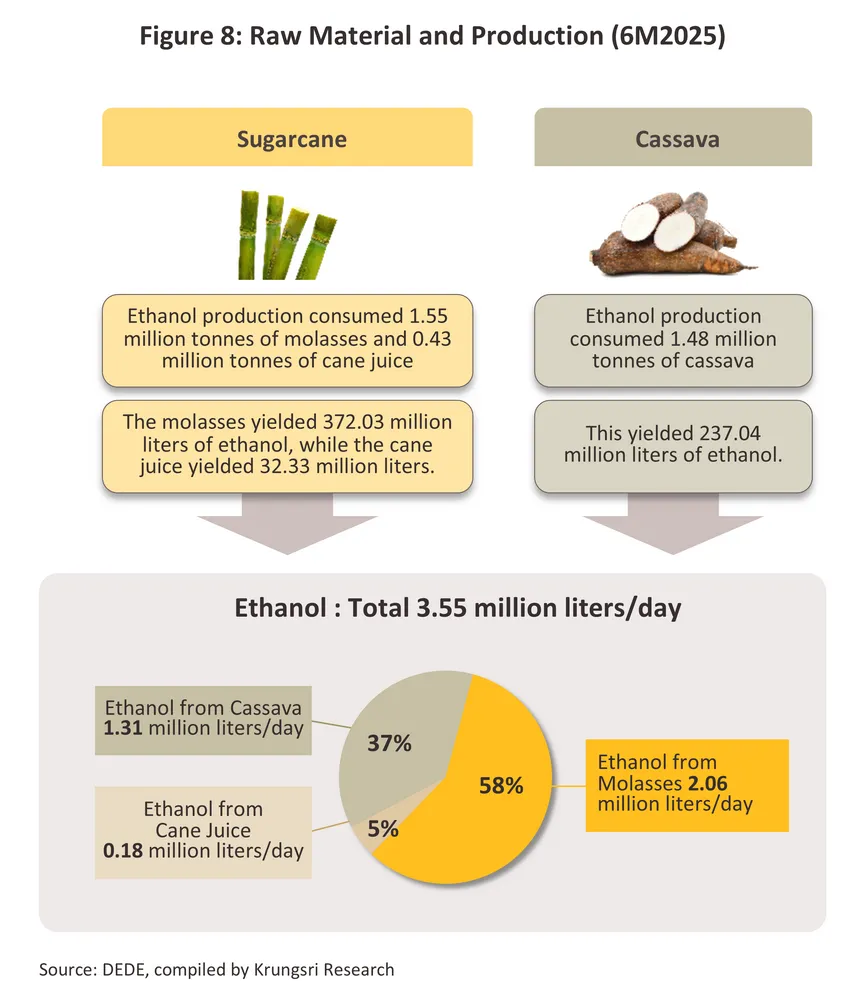

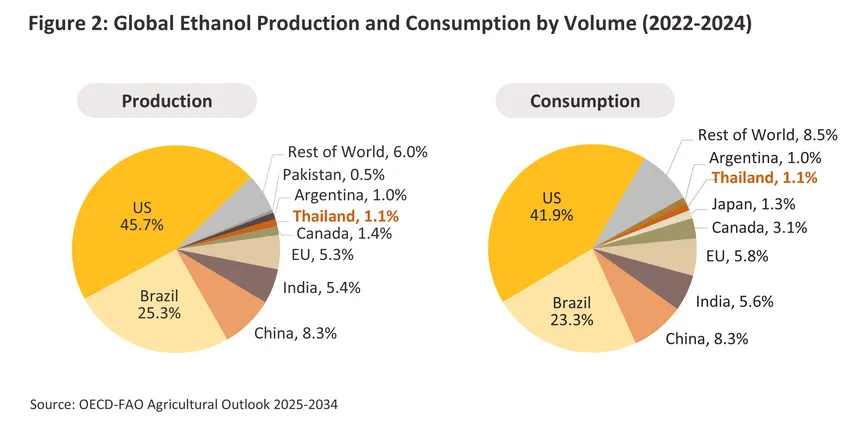

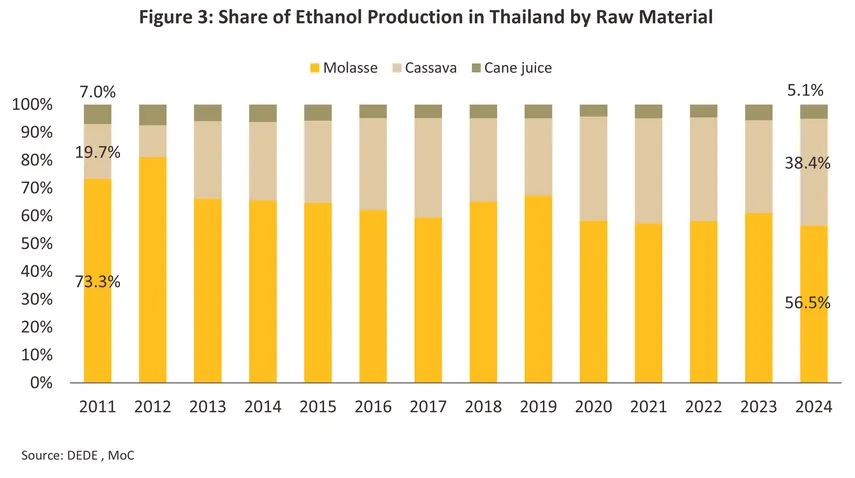

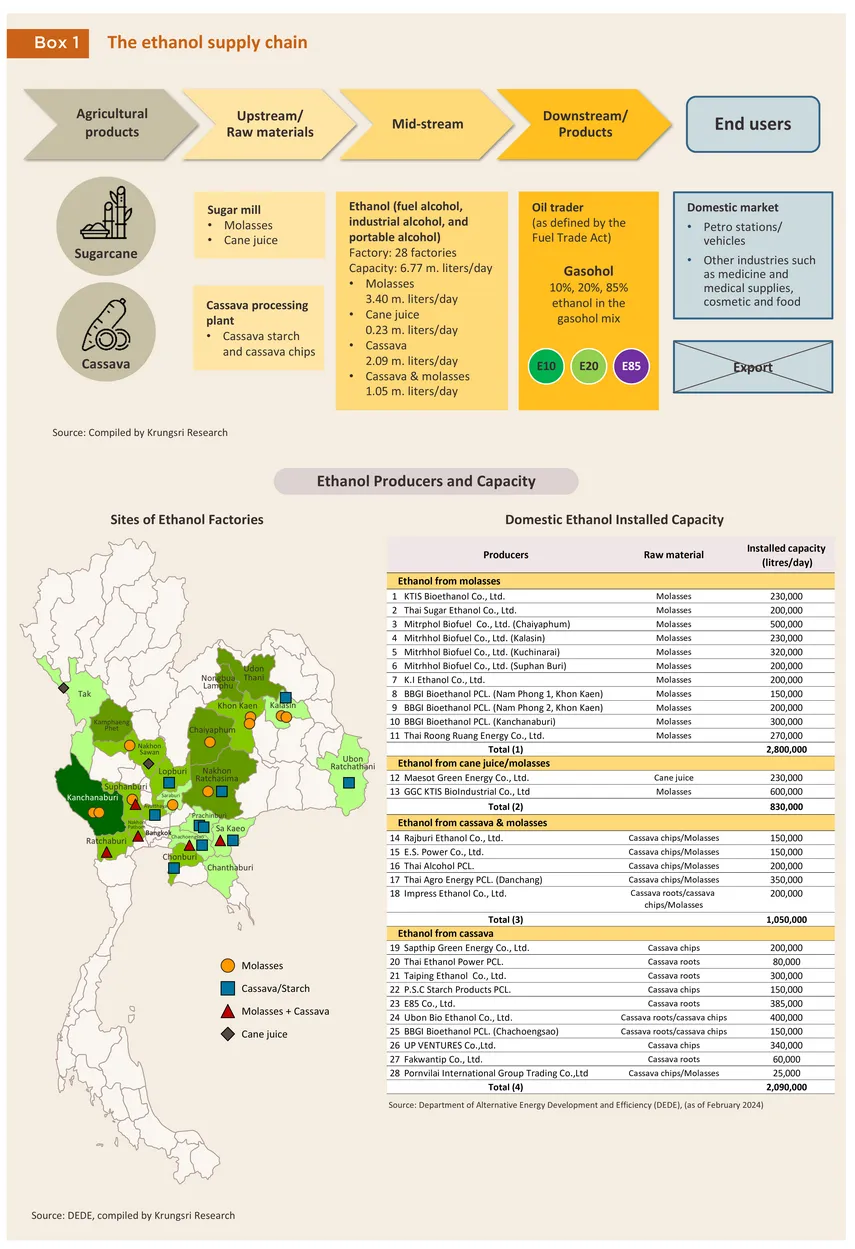

The most important inputs into Thai ethanol production are molasses, cassava and sugarcane, and in 2024, these three accounted for respectively 56.5%, 38.4% and 5.1% of domestic ethanol production (Figure 3). The exact proportions of the different inputs that are used will vary according to their relative costs at any given moment in time. Thus, as molasses prices rise, consumption by the ethanol industry will generally decline. However, use of molasses as a raw material typically outpaces that of cassava given the relative ease of accessing supplies of this, though this is partly because some ethanol producers are major players in the sugar market that have expanded downstream from sugar processing into the production of ethanol. By contrast, using cassava as an input may entail enduring stiffer competition with players from other industries that are also trying to secure raw materials, while government interventions in the market in support of farmers can also add to uncertainty over prices.

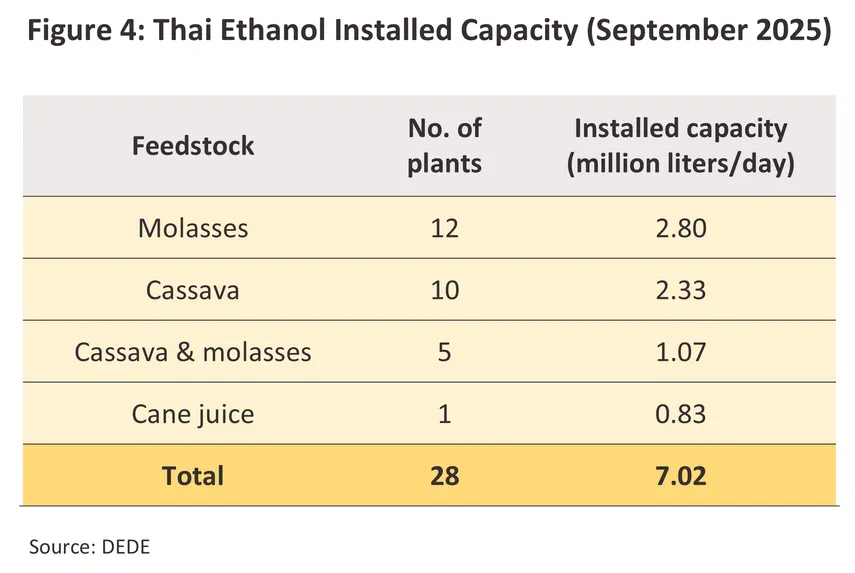

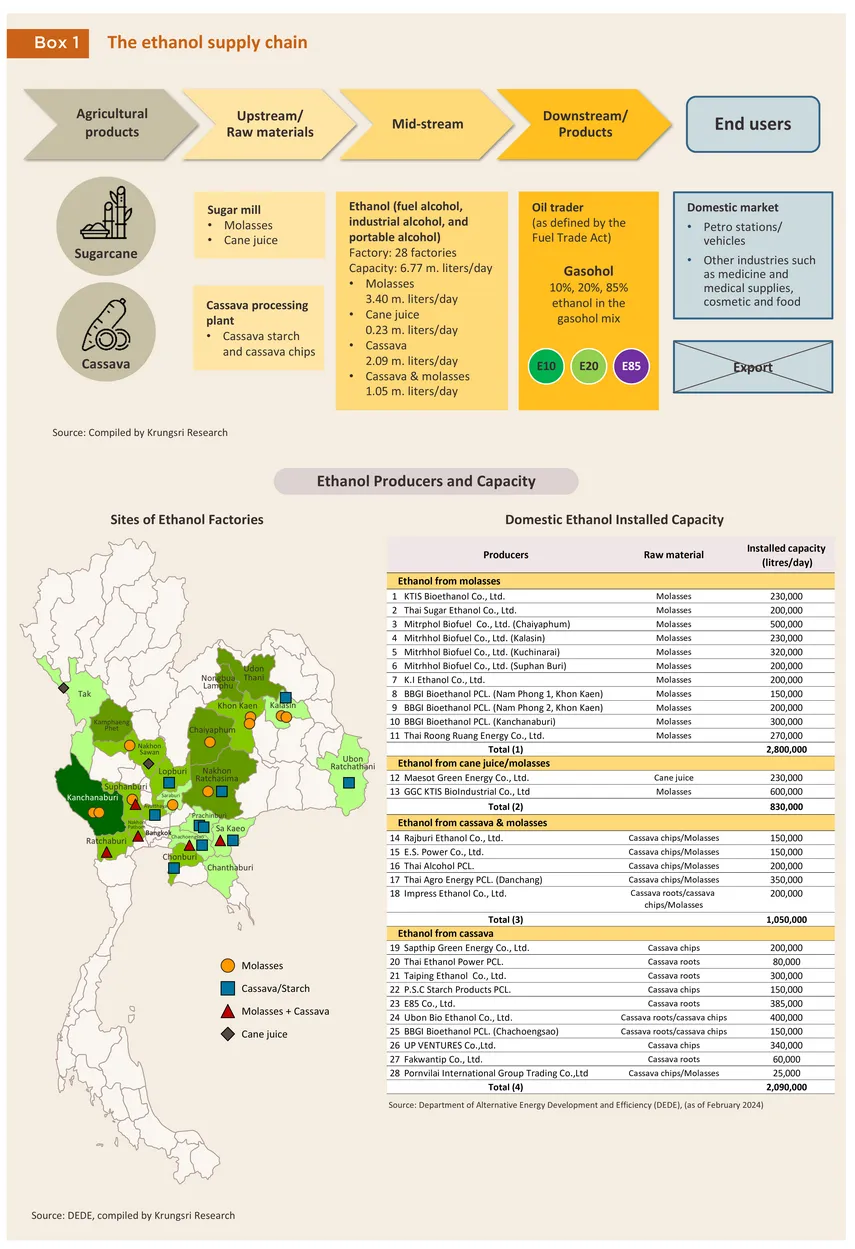

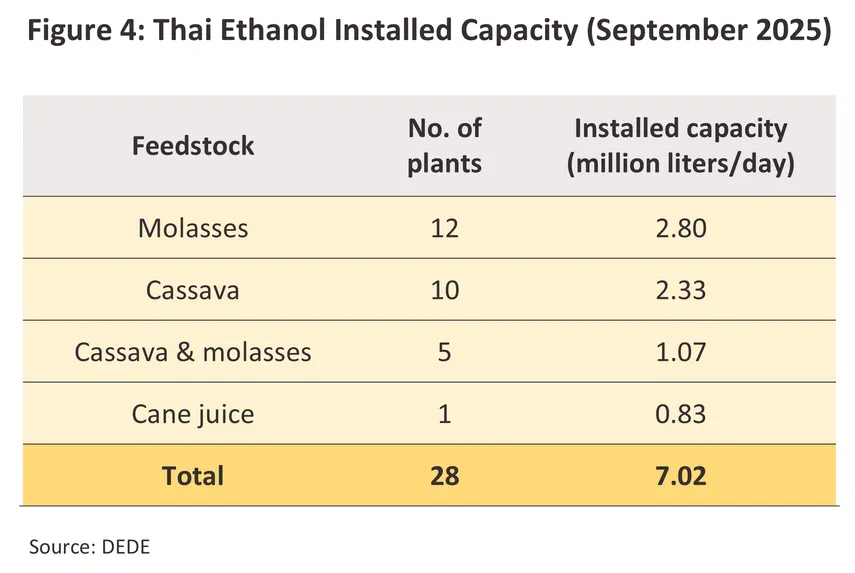

At present (as of September 2025), there are 28 ethanol distilleries operating in Thailand, most of which are downstream operations that are part of major players in the sugar or cassava markets (Box 1). These have a combined production capacity of 7.0 million liters per day, up from an average of 6.8 million liters in 2024. Of this, 2.8 million liters is for molasses-based production, 2.3 million liters for cassava-based production, 1.1 million liters for a mixture of the two, and 0.8 million liters for production from sugarcane juice (Figure 4). The majority of distilleries are located in the central and northeastern parts of the country

The cost structure of the industry depends on the inputs that are used.

-

For molasses-based production, inputs account for 60-70% of production costs, operating costs take up a further 25-35%, and 5% goes towards fixed costs.

-

For cassava-based production, at 55-60%, raw materials contribute a lower share of overall production costs but operating costs are higher (35-40% of the total), while at 5%, fixed costs are the same. Compared to molasses, using cassava as an input imposes higher overheads due to the more complex processing required to convert cassava starch into the sugars that are needed to produce ethanol.

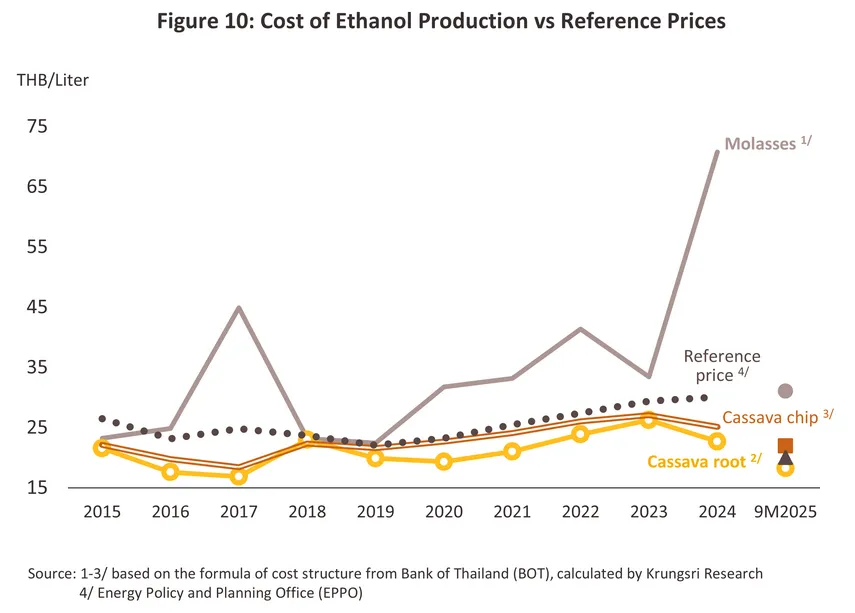

The ethanol market is guided by a reference price, and this is determined by data collected by the Excise Department on sales of ethanol on the domestic market. An average price, weighted according to the volume of actual sales, is thus announced on the 1st day of the month, and since 1 January, 2012, this has been used as the ethanol reference price. Producers’ margins (i.e., the gap between sale prices and production costs) are determined by: (i) the cost of inputs; (ii) changes in the reference price, which may be driven by shifts in the proportion of the total output coming from molasses and cassava; and (iii) marketing costs of around THB 1-2 per liter.

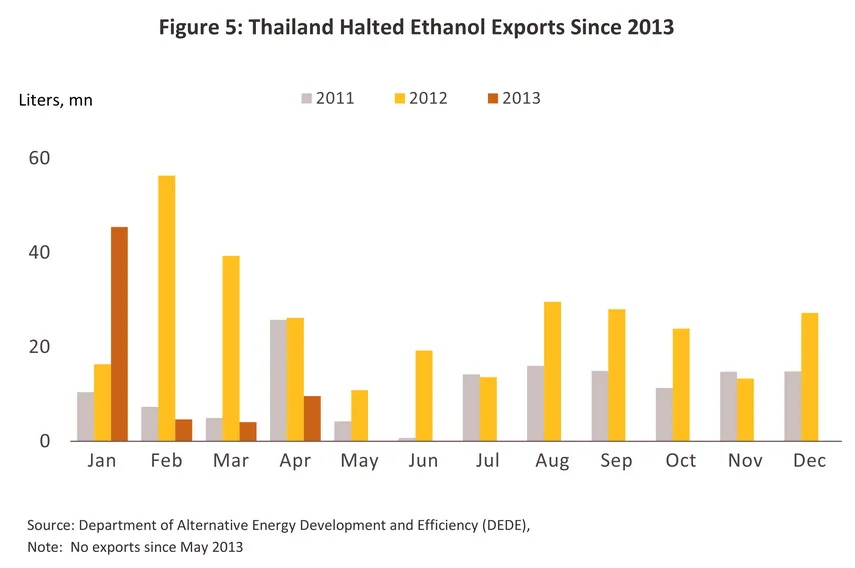

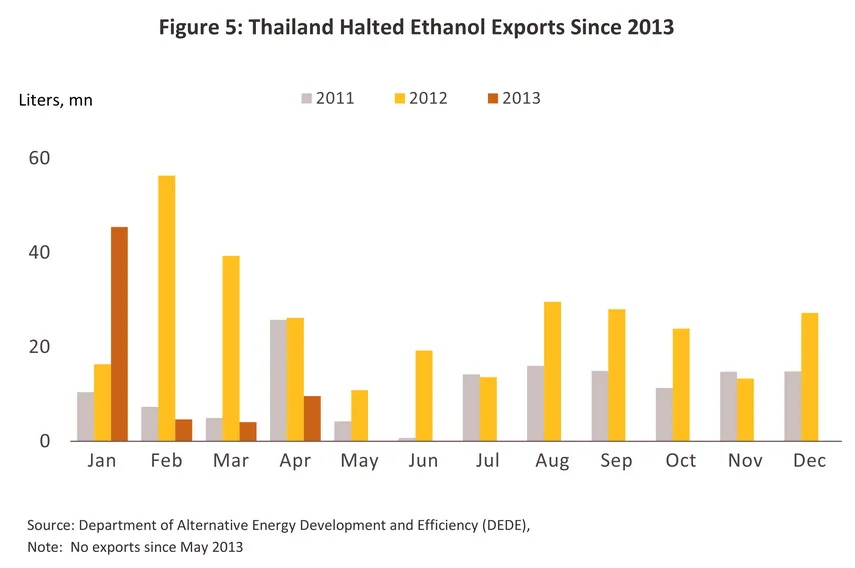

The ethanol market presents a slight peculiarity: typically, there are no exports at all. This can be attributed to a government having ordered a halt to these in May 2013 (Figure 5), prompted by officials' concerns about maintaining adequate ethanol stocks following the cessation of sales of 91 and 95 octane petrol on January 1, 2013. Despite this overarching prohibition, there are exceptions. For instance, in March 2014, 4 million liters were exported, and again in December 2020, the export of 54,000 liters of ethanol was approved. (Before the ban, exports were permitted since 2007, albeit subject to individual approval by the Director-General of the Excise Department. During this period, the primary export markets were the Philippines, Japan, and the UK).

Government policy and support for the ethanol industry is laid out in the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP), and this includes: (i) setting goals for production with reference to demand from the transport sector and the promotion of gasohol consumption; (ii) promoting the development of vehicles that are able to run on E85 gasohol; (iii) encouraging the wider and more comprehensive distribution of biofuels (E20 and E85) on forecourts across the country; and (iv) providing price subsidies via the Oil Fund. These policies have helped to underpin expansion in the ethanol market, but the government has now moved from relying on the price mechanism to stimulate demand towards making E20 gasohol the default option, with other fuel types relegated to alternative status. This is expected to positively influence demand in the coming period.

Situation

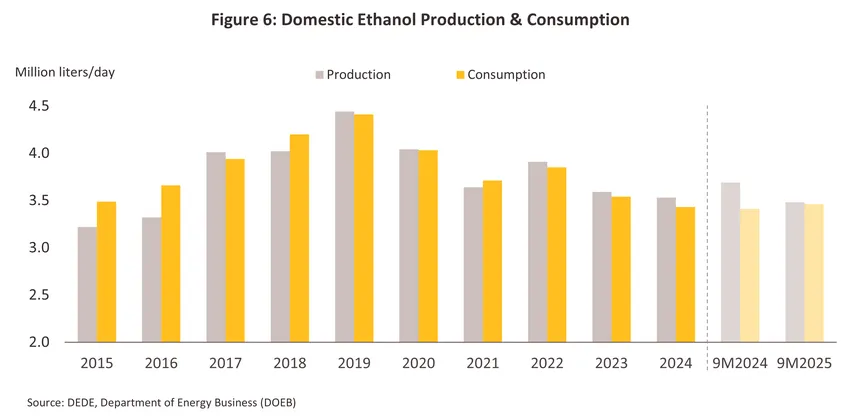

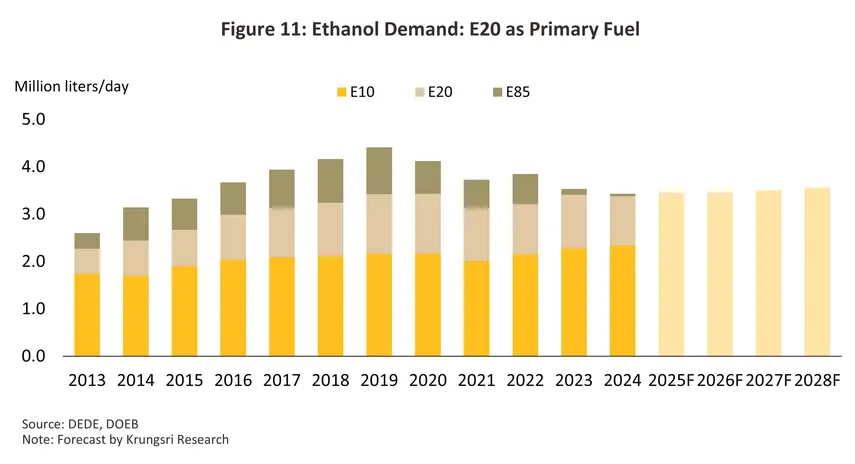

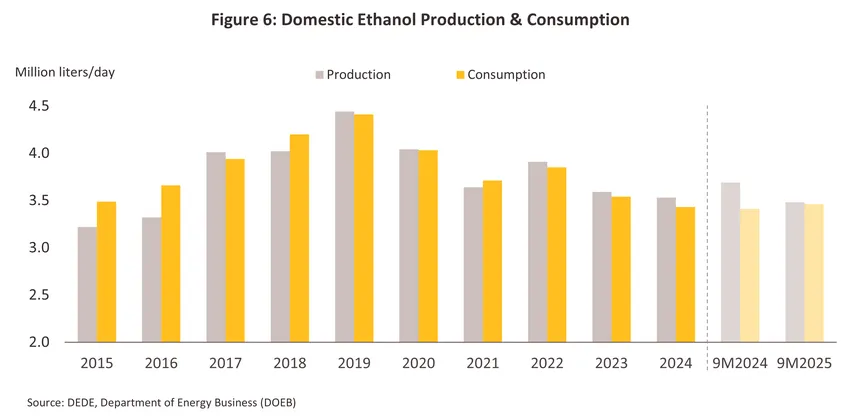

In January 2013, the government ended sales of 91 octane benzene (at the time, 41% of sales of all benzene products) and instead made gasohol the main petrol product sold on forecourts. This then helped to alleviate problems with excessive production capacity that had weighed on the market through the period 2007-2012. At the same time, the development and release to the market of new car models that were able to run on E20 and E85 help to stimulate greater demand for the former and so average daily ethanol consumption rose from 2.6 million liters in 2013 to 4.4 million liters in 2019, or average annual growth of 20.3% (Figure 6). However, consumption of ethanol slumped under the impact of the pandemic, dropping -15.9% to hit a 5-year low of 3.7 million liters/day in 2021. The reopening of the country to foreign tourism in July 2022 marked a return to growth, and with economic and social activity recovering, travel rebounded and demand for ethanol for mixing into gasohol climbed to an average of 3.85 million liters/day (up 3.8% relative to 2021).

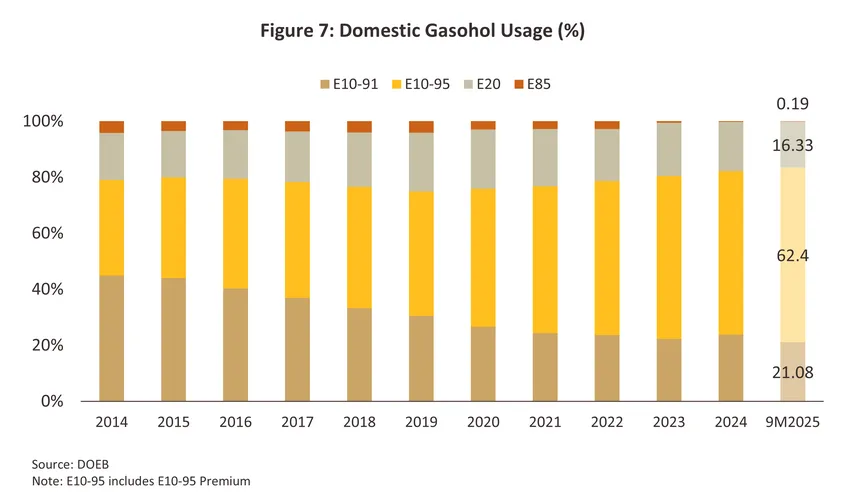

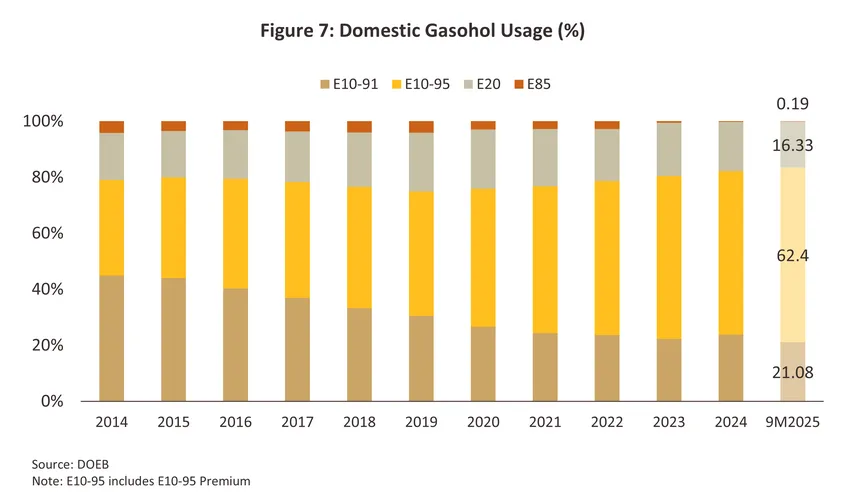

Economic recovery, which was led by the tourism sector, boosted demand for gasohol by 4.3% from its level in 2022, and so this rose to an average total of 30.9 million liters/day. However, the government will be making either E10 or E20 (currently under discussion) the nation’s primary petrol product and so from the end of 2022, it began to withdraw support for E85 that had been provided through the Fuel Fund3/. As a result, prices for E85 climbed to THB 34.8/liter, up 8.5% from its 2022 price of THB 32.1/liter and THB 0.3/liter above the cost of E20. This price discrepancy fed through into a 6.9% rise in demand for E20, while sales of E85 slumped -81.2% and the outcome of this was that the contribution of E85 to total sales of gasohol dropped from 2.8% in 2022 to just 0.5% a year later. Collectively, these factors combined to pull demand for ethanol down by -8.1%, and across 2023, this therefore averaged 3.5 million liters/day (Figure 7).

Demand for ethanol declined by another -3.0% in 2024 to an average of 3.4 million liters/day. Weakening consumption was driven by a number of factors. (i) The market is increasingly tipping in favor of electric vehicles (EVs or xEVs), especially battery electric vehicles (BEVs), and so registrations of new xEVs rose from 171,773 in 2021 to 203,913 in 2024, restricting growth in demand for gasohol to just 0.2%. (ii) The extension of the Bangkok metro system, in particular the opening of the Yellow and Pink lines and their connections to the main lines, has made it easier to travel around the capital without a car. (iii) Consumers remain worried about excessive fuel consumption and the effects on their cars of the long-term use of E20, and so despite this being on average THB 2/liter cheaper than E10, sales of the latter are greater than the former. (iv) Consumption of E85 is down -56.3% from its level in 2023, and so sales of this now come to just 0.07 million liters/day.

Demand for ethanol picked up slightly through 2025, in line with the consumption of gasohol expecting to expand by just 1.0-1.5% to reach 31.2 million liters/day. This was due to companies looking to push through orders before the imposition of the US ‘reciprocal’ tariffs in August, which then manifested as an uptick in activity in the domestic manufacturing and import-export industries. Sales also benefited from ongoing growth in e-commerce and the resulting need for fuel for transport and delivery services. However, this was counterbalanced by a number of headwinds. (i) The economy saw only sluggish rates of growth, and with foreign arrivals expected to decline -6.2% YoY to 33.3 million, the tourism sector struggled through the year. The heavy burden of household debt also dragged on spending, and so consumers are exercising greater care over their expenditure, while the new US tariffs have encouraged businesses to hold off on new investments and to see how the situation develops. Given this, growth in demand for transport fuels was only limited. (ii) The market for xEVs is growing rapidly, and over the first 10 months of the year, new registrations of these jumped 28% YoY to 227,678. For the year, sales are expected to surge 28.5% to 262,000 vehicles, and naturally, this is undercutting demand for transport fuels. (iii) Government policies to promote the use of Bangkok’s metro system have included the introduction of a flat THB 20 fare on the Red and Purple lines between October 2023 and November 2025, and as a result, some travelers switched from using their cars to traveling on public transport. Current conditions in the ethanol industry are described below.

-

Ethanol consumption averaged 3.46 million liters/day, up 1.4% from 2024, though the latter compares unfavorably with pre-pandemic growth of 3-4% per year. Demand was driven by the 1.4% increase in sales of benzene products, which thus rose to an average of 31.2 million liters/day. 62.4% of sales were of gasohol 95, which was followed in importance by gasohol 91 (21.1%). Sales of E85 fell by another -13.3% YoY over 9M25 to just 0.06 million liters/day, this contributed just 0.2% to overall sales (Figure 7).

-

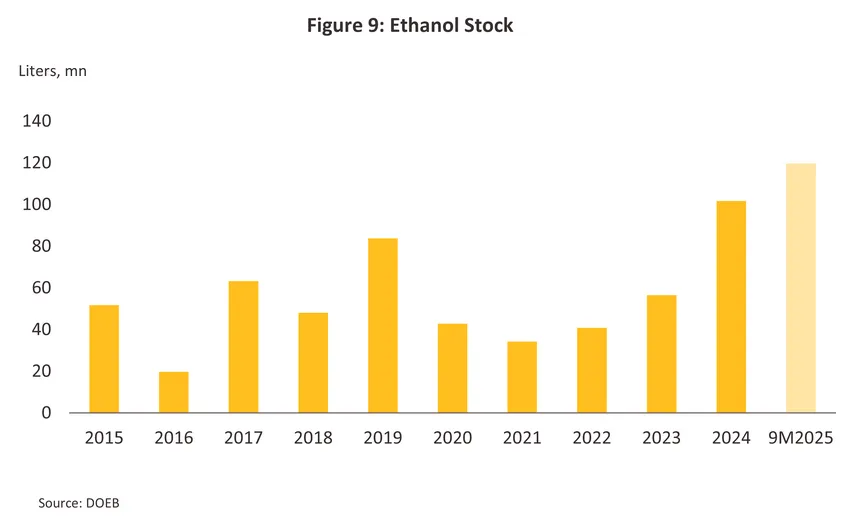

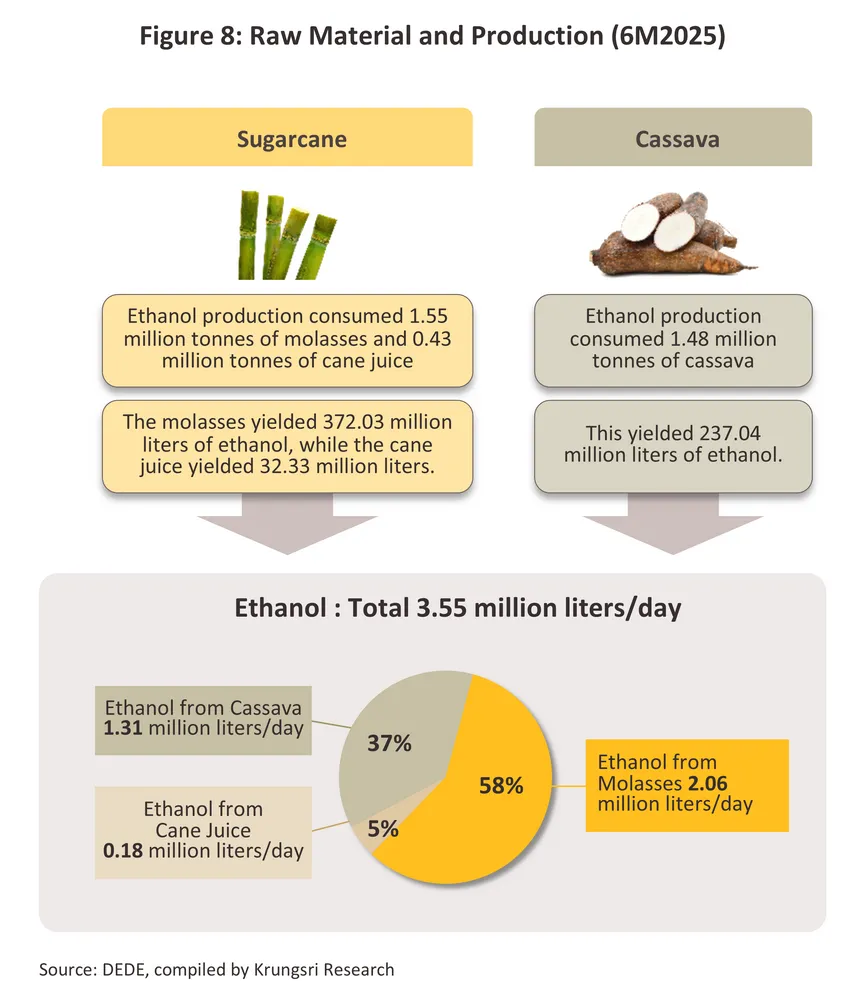

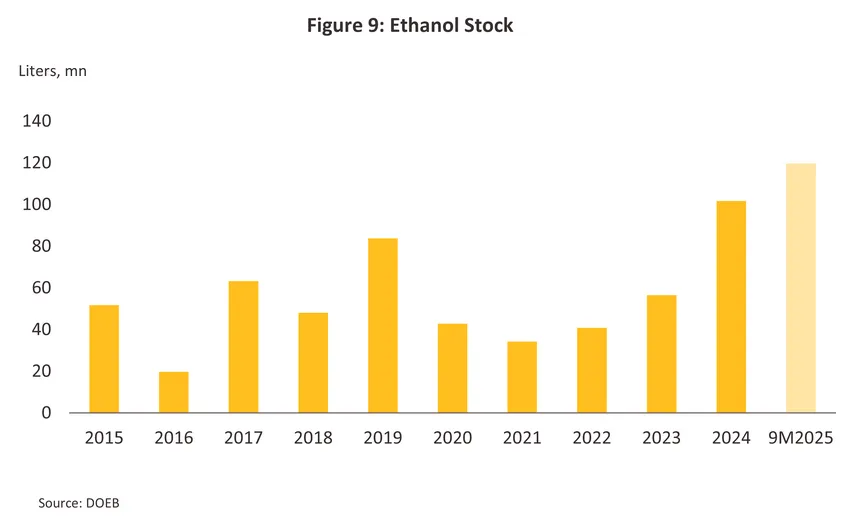

Output declined -5.6% to an average of 3.48 million liters/day as manufacturers looked to better match supply to slowing market demand. Daily production from molasses (59.5% of production), cassava (35.5% of output), and sugarcane juice (5.0%) fell by respectively -0.9%, -12.1% and -8.7% to daily averages of 2.1 million, 1.2 million and 0.17 million liters (Figure 8). 2025 year-end stocks should come to 100-110 million liters (Figure 9) but capacity utilization has dropped from 52.2% in 2024 to 49.6% a year later.

-

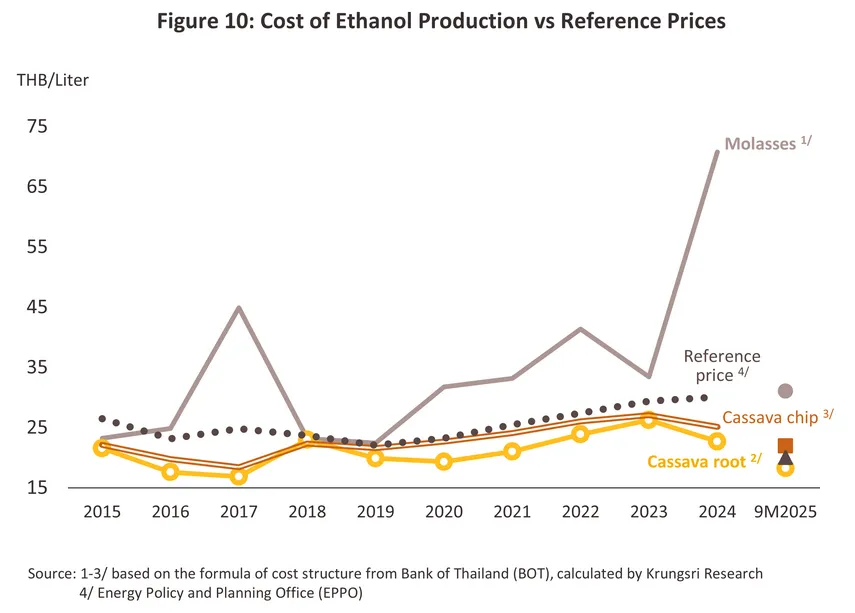

The ethanol reference price crashed -35.0% in the year, falling to an average of THB 20.0/liter on weaker prices for both molasses and cassava (Figure 10). However, the effects of this on margins varied for producers using different inputs.

-

Molasses-based production: The -69.0% slump in the cost of inputs (down to just THB 5.6/kg) led to an expansion in margins for players producing ethanol from molasses. This was a result of heavier rainfall through the latter half of 2024, which boosted the 2025 harvest, and lower cassava prices that encouraged farmers to plant sugarcane instead. These factors expanded the quantity of sugarcane and molasses coming to market. Molasses prices were also undercut by the slide in the cost of sugar, which slipped to its lowest point in 3-4 years on a jump in supply to global markets. This sharp dip in the cost of raw materials cut overall molasses-based manufacturing costs to an average of THB 31.0/liter (down -62.7% from 2024).

-

Cassava-based production: Margins widened slightly on a -33.2% drop in prices for fresh cassava, bring the average down to THB 1.6/kg. The spread of cassava mosaic disease encouraged farmers to harvest prematurely in 2025, resulting in lower-quality crops with reduced sugar content. This depressed prices further and pushed production costs down by 21.7% to THB 18.3/liter. Although fresh cassava prices dropped by a third, cassava chip prices fell by a smaller -21.4%, reaching THB 5.3/kg. In addition to cheaper fresh roots, efforts to clear inventory and weakening demand from China—where ethanol producers have shifted to cheaper domestic corn—also contributed to the decline in chip prices. As a result, overall production costs for ethanol made from cassava chips eased to THB 22.0/liter, a decrease of 14.7%.

Outlook

Krungsri Research sees demand for ethanol remaining largely unchanged at 3.46 million liters/day through 2026, with growth rates hovering in the range -0.5 to 0.5%. Sales will be impacted by a slowdown in overall economic growth, which is forecast to slip to 1.8% on a combination of a -1.8% contraction in exports and softer private-sector consumption (expected to grow by just 2.2% due to weak spending power). More positively, demand will benefit from tailwinds coming from the travel and transport sectors. Thus, an expected 6.6% increase in foreign arrivals will lift these to 35.5 million, wealthier Thai consumers will continue to support the market for domestic tourism, and ongoing growth in e-commerce will boost demand for delivery services.

The market will strengthen in 2027 and 2028 and a 1.0-2.0% expansion in demand will take average daily consumption to 3.50-3.55 million liters/day (Figure 11) (on the assumption that the government designates E20 as the standard petrol mix). The major drivers of consumption will include the following.

-

Rates of economic growth should inch up to 2.0-2.5%, helped by a better outlook for the tourism sector. In particular, foreign arrivals are now forecast to reach 39 million by 2028.

-

The number of vehicles on Thai roads running on gasohol will expand by 1.0-2.0% per year. Total domestic auto sales (including EVs) are forecast to grow by 0.5-1.5% annually, or to 0.56-0.59 million vehicles, and around 70% of these will be ICE-powered. At the same time, the total number of EVs registered in Thailand (including HEVs, PHEVs, and BEVs but excluding electric motorcycles) will likely not exceed 3-5% of the size of the ICE fleet. Research by the Thailand Automotive Institute (using the international Fuel Economy WMTC Mode, EURO4 standard) shows that although E20 was 7% cheaper than E10 95, it has approximately 8% greater fuel efficiency. At the same time, acceleration and engine performance are broadly comparable across E20 and other types of gasoline3/.

-

E-commerce sales will continue their relentless expansion, with annual growth in the domestic market forecast to average 5.1% over 2025-2030 (source: Statista), boosting uptake of delivery services (for parcels and documents) and adding to demand for transport fuels.

However, if the government decides to designate E10 rather than E20 as the standard petrol mix, the resulting fall in demand for ethanol for mixing with this will cut demand by between -3.6% and -4.6%, reducing overall consumption to 3.10-3.19 million liters/day.

Over the long term, the government plans to support ongoing expansion in the ethanol market, and to this end, the Alternative Energy Development Plan (2018-2037) has set a target of consumption reaching 7.5 million liters per day by 2037 (down from the 11.3 million specified in the AEDP 2015). This entails implementing plans for absorbing excess production capacity through greater use of ethanol in downstream industries. Details of this are given below.

-

Using ethanol in the production of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF): The 2024 Oil Plan has set a target of replacing 1% of standard A-1 jet fuel with SAF by 2027 as part of more general moves to green the energy system (However, at present, SAF is only available in small volumes since producing this is expensive and depends on access to a significant quantity of inputs). These trends are being seen worldwide, including in the European Union’s ‘Destination 2050–A Route to Net Zero European Aviation’ program. This aims to cut carbon emissions generated by flights leaving the EU, the UK and EFTA member states by 55% by 2030 and to reduce these to zero by 2050, and a central plank of this strategy is the use of SAF. Beyond this, many countries are planning to switch over to the use of the Airbus A321neo by 2035, which has been designed to increase fuel economy and to provide an all-round more environmentally friendly service.

-

Promoting greater use of ethanol in other industries: It is hoped that in the future, demand from the pharmaceuticals, herbal extracts, cosmetics, and bioplastics industries will grow, which would then be a significant source of added value for ethanol manufacturers. An example of these developments can be seen in the joint venture by Braksem and a Thai petrochemicals company to produce bioplastics including bio-ethylene and bio-polyethylene. This would not only help to build demand for ethanol but would also support the development of the BCG (bio, circular and green) economy and through this, help meet the national commitment to reach net zero by 2050 (brought forward from 2065). To this end, the Excise Department has considered extending the tax-exempt status of ethanol from that used in the production of fuels to also include ethanol used in the production of bio-ethylene and other bioplastics. This would help to add value to sugarcane and cassava supply chains but these changes are still in their infancy and over the next three years, their likely impacts on the ethanol industry will be restricted.

Nevertheless, such ambitious plans for growth in the ethanol industry will put pressure on supplies of inputs, in particular of sugarcane and cassava, and this may then impact demand for these for consumption. The authorities therefore need to press forward rapidly with plans to expand the area under cultivation and to research how ethanol can be made from agricultural waste (e.g., rice straw, bagasse and corncobs). This would then serve the twin goals of helping farmers generate added value from farm waste and assist the authorities in meeting their goal of seeing ethanol output increase sustainably.

The industry will face a number of challenges. (i) Worsening climate variability is impacting access to and the price of inputs, and so during spells of drought, sugarcane yields have contracted and output of sugarcane and sugar products has fallen. Simultaneously, demand for sugar, molasses and cassava from other industries (e.g., in the production of alcohol, animal feed and food and beverages) on both domestic and export markets is rising and this will tend to increase upward pressure on prices. Given this, production costs will tend to rise and margins will narrow. (ii) Consumer fears over possible engine problems and higher fuel consumption resulting from the use of gasohol with a higher ethanol content will continue to weigh on sales, as can be seen in demand that is currently weaker for E20 than for E10. (iii) Uncertainty remains over whether E10 or E20 will be set as the main gasohol variant. If the government comes out in favor of the latter, this will naturally lift demand and players will be able to push production capacity to 6 million liters/day, while settling for E10 would have the opposite effect and would substantially reduce overall demand. Moreover, whatever the outcome, the current lack of clarity is making it difficult to plan investments and is in addition generating inefficiencies in the sourcing of inputs. (iv) Purchases of EVs will build steadily, helped by the government’s goal of at least 30% of new auto production being of zero emission vehicles (ZEVs) by 2030, and these trends will then undercut demand for ethanol for blending into gasohol. Forecasts contained in the draft Oil Plan 2024 thus show that if E20 becomes the primary gasoline mix, demand for ethanol from the transport sector will peak at 4.7 million liters per day in 2027 before declining to 4.4 and 3.3 million liters daily in 2032 and 2037. (v) The Reciprocal Trade Framework agreed between Thailand and the US on 26 October 2025 permits US exports to Thailand of ethanol for use as a transport fuel, and this will only amplify pre-existing problems with an oversupply of production capacity within the industry.

1/A replacement for octane additives in benzene, or MTBE (methyl tertiary butyl ether).

2/Gasohol 91 and 95 are made by mixing lead-free benzene with 10% ethanol. This results in 91 and 95 octane gasohol, which can then be used in vehicles in place of regular 91 and 95 octane mineral fuels.

3/Ethanol oversupply weighs on the market; industry urges government to look to new markets’ Prachachat.

4/Brazil's Raizen ships 2G ethanol cargo to EU | Argus

5/These figures come from the AEDP2018, which is based on data on agricultural waste from 2017.

.webp.aspx)