Executive Summary

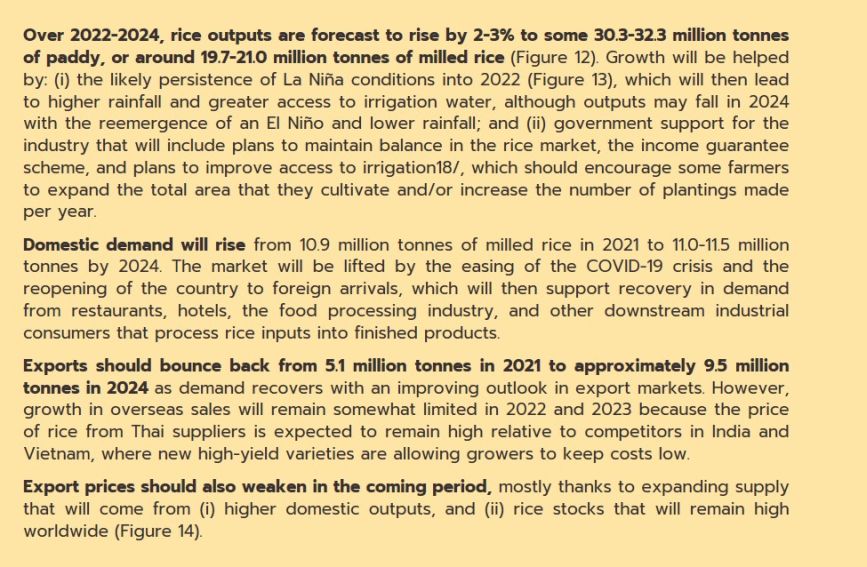

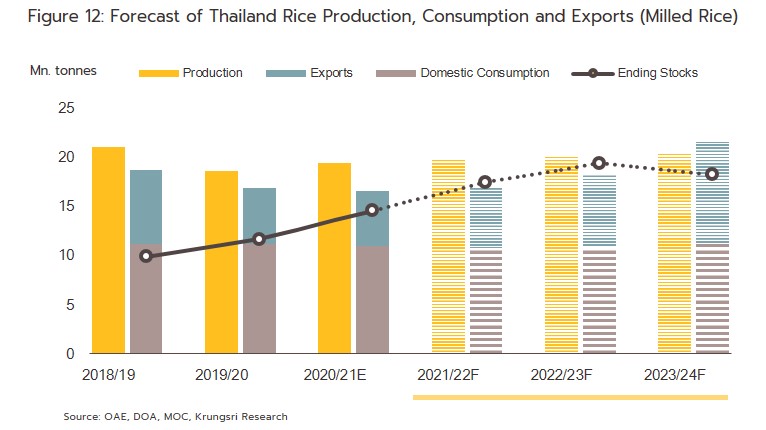

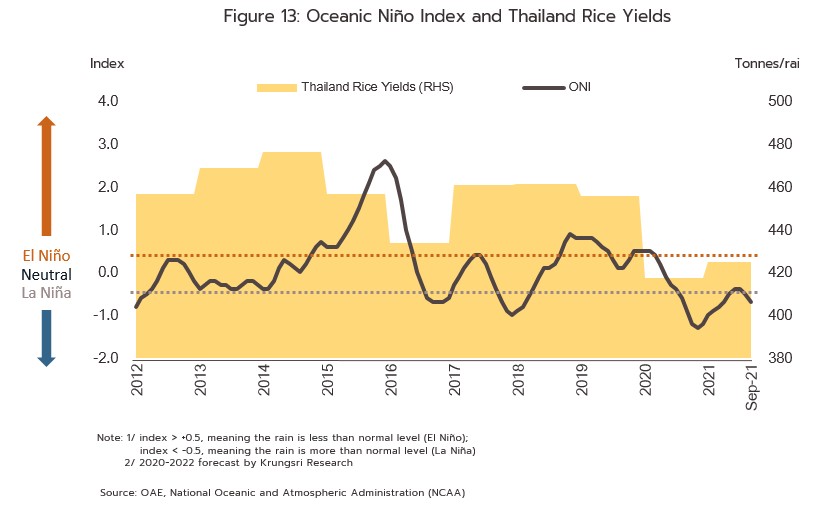

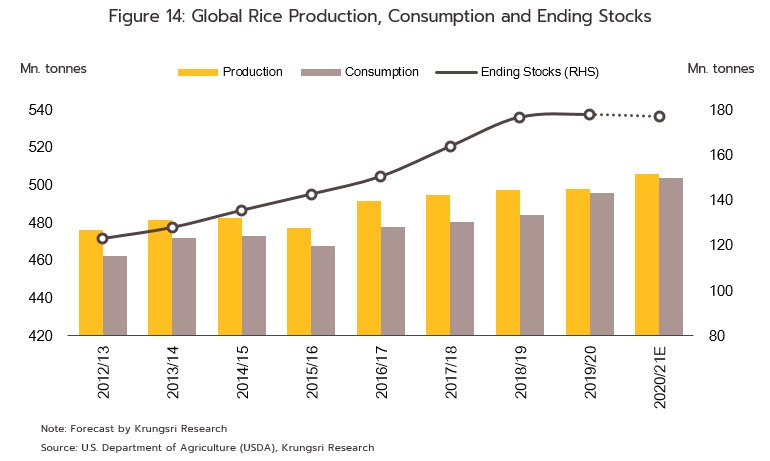

For Thai farmers, outputs of rice will tend to strengthen over 2022-2024, helped by what is forecast to be better weather, higher rainfall, and a greater supply of irrigation water. In addition, government support for rice growers, in particular income guarantees that are expected to be ongoing, will encourage farmers to expand the area under cultivation and/or the number of plantings. Domestic demand will rebound with recovery in restaurants, hotels, and downstream food-processing industries, while overseas sales will improve with strengthening consumer spending power in export markets. Exports will be helped further by prices for Thai rice that will tend to soften on higher outputs, and by the easing of problems with transport and logistics caused by COVID-19 that plagued the global economy through 2020 and 2021. However, despite this broadly positive outlook, exporters will be exposed to a degree of risk arising from stiffening competition from other rice-exporting nations, including India and Vietnam, which are developing new strains of rice that produce higher yields and carry lower costs.

Krungsri Research view

The outlook for the rice industry will improve slightly over 2022-2024 on higher outputs and weaker prices. However, competition remains stiff and this will drag on income for operators through the length of Thai rice supply chains, though mills, silos and retailers, most of which are SMEs, will be most seriously affected by this.

- Rice growers: Outputs are expected to rise on favorable climatic conditions and access to irrigation water, while the government will support the industry through income guarantees and measures to balance the rice market, and this will underpin rising incomes for rice growers. Against this, though, farmers will face problems that will include their weak market position, especially when negotiating with middlemen and traders, and higher production costs, which are expected to rise from THB 9,831/tonne/year in 2021 to THB 10,500-11,000/tonne/year in 2024 (CAGR 2.5-3.5%) (source: Office of Agricultural Economics).

- Rice millers: Although greater opportunities will come with higher outputs, the continuing extensive oversupply of milling capacity will weigh on profits. In particular, this will be a problem for small players, which will lose out to mid-sized and large operations and their stronger negotiating position when securing inputs, and this will then mean that small players will have to contend with higher costs. The most competitive players will be large integrated operations and mid-sized mills that are able to control costs most effectively.

- Producers of packaged rice: In this segment, income will tend to increase gradually, especially for large players that run integrated operations that extend to include milling and exports. The segment will be helped by the easing of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent growth in demand from household, restaurant and tourism markets. However, the entry of new players to the market is increasing competition, while business costs to the market through modern trade outlets are also rising, for example for marketing and buying space on supermarket shelves.

- Traditional rice retailers: Revenue and profitability will tend to remain very limited due to the increasing competition from packaged rice in competition on price, management process and quality of storing process. traditional rice sellers are expected to lose market share to modern trade outlets, and they will have to fight against ever-stiffening competition.

- Rice exporters: Exports of rice from Thailand are expected to rise steadily, helped by lower domestic prices for rice that will help to make exports more competitive. Demand will also strengthen overseas and so income will tend to climb within this segment.

- Silos: Income for silo operators will recover somewhat on: (i) higher outputs that will feed into stronger demand for silo space; (ii) the exit from the market of some players after years of running loss-making operations; and (iii) demand for silo space for the storage of other cereal crops. Nevertheless, despite an improving outlook, competition remains stiff and so operators are at a disadvantage relative to their customers, and this will limit players’ ability to generate profits.

OVERVIEW

Rice has long been Thailand’s most important crop and its major agricultural export. Rice cultivation thus accounts for 46.1% of all Thai farmland [1], and 4.9 million households (or 60.5% of those in the agricultural sector [2]) are dependent on its cultivation. Given this dominance within the agricultural sector, rice farmers are naturally the recipients of government aid, which includes price policies, such as price guarantees, a rice pledging scheme, and a mixed bag of other programs that extends over financial assistance with planting and harvesting costs and help with the development of new rice varieties.

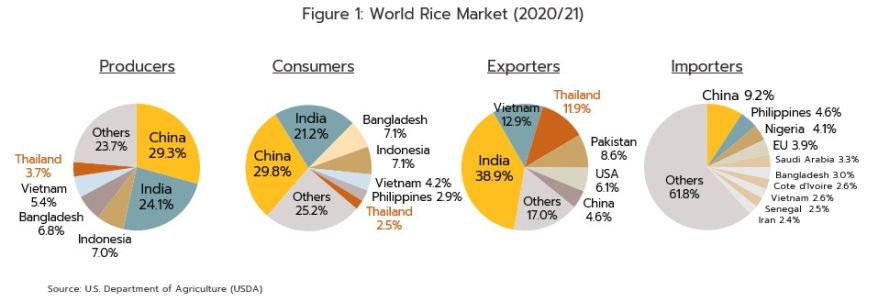

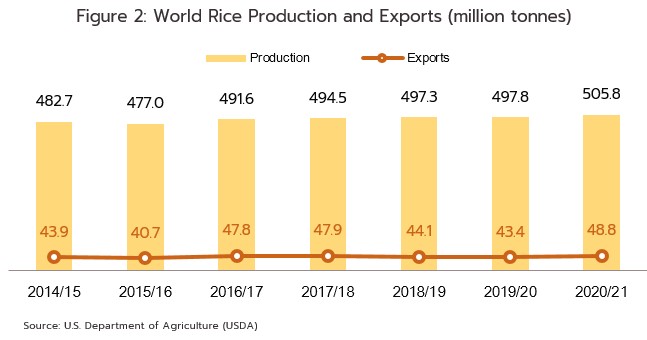

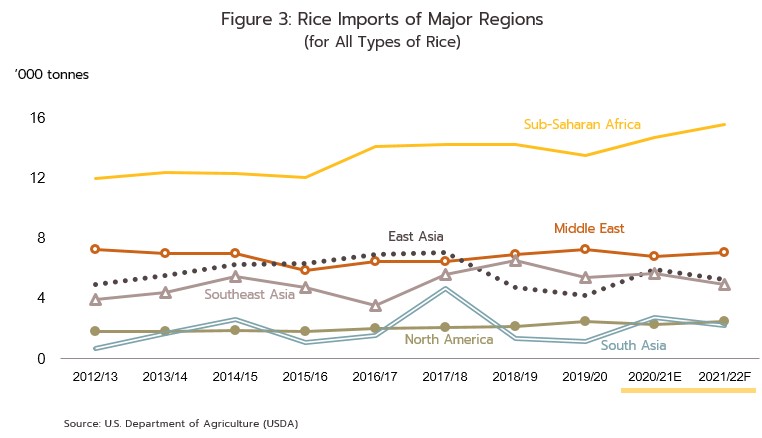

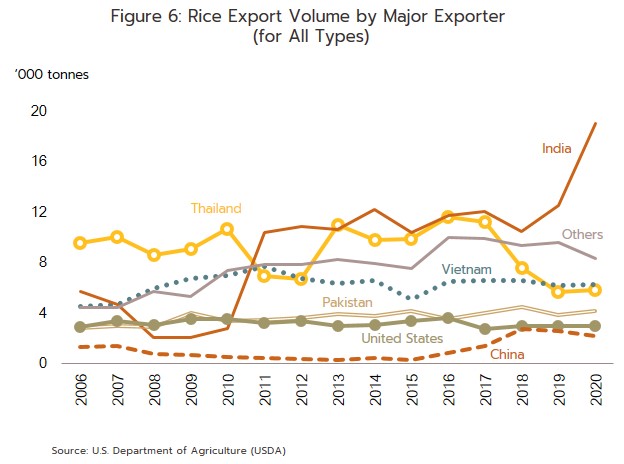

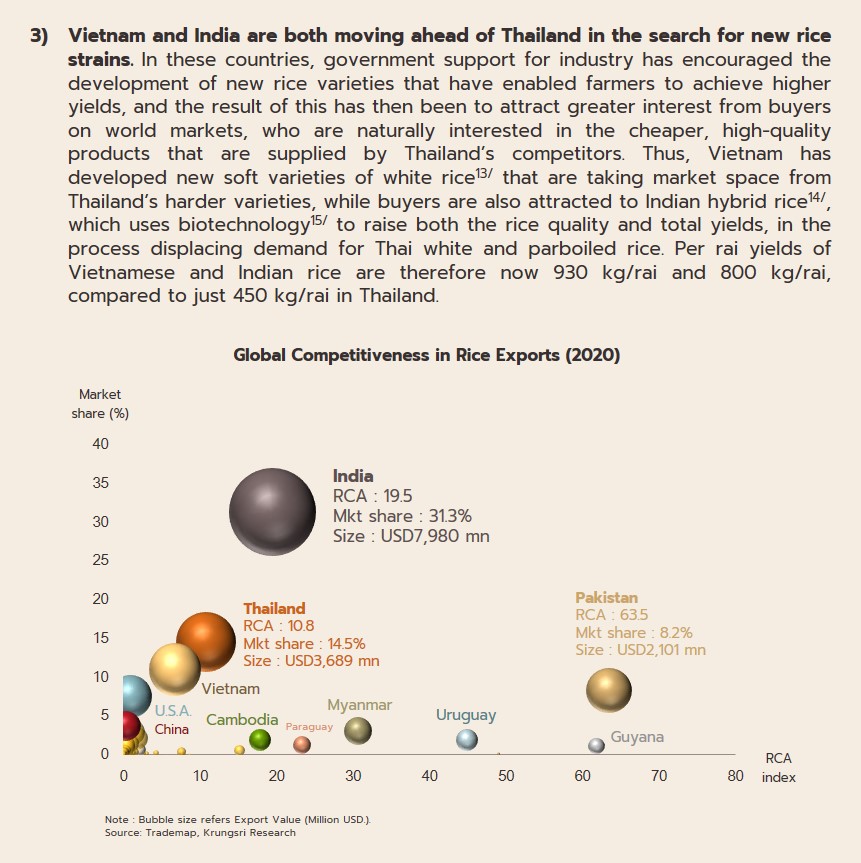

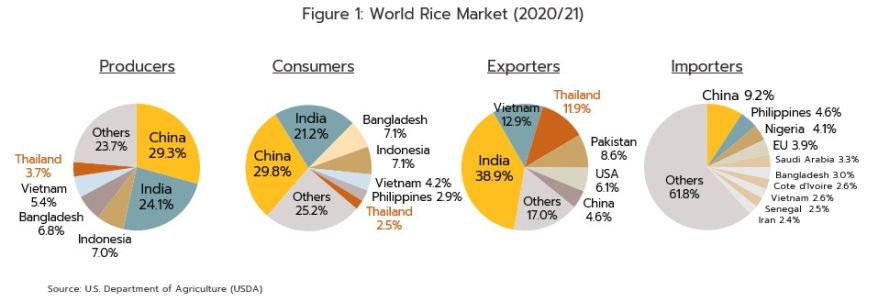

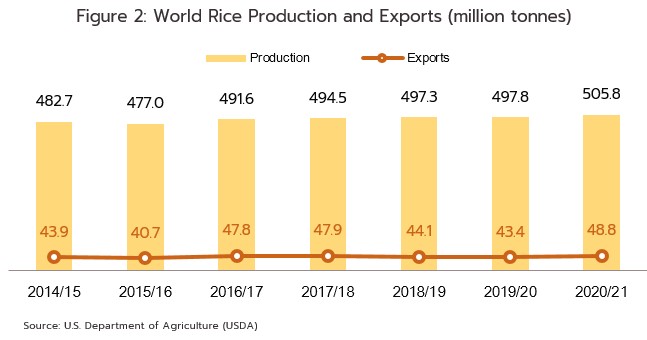

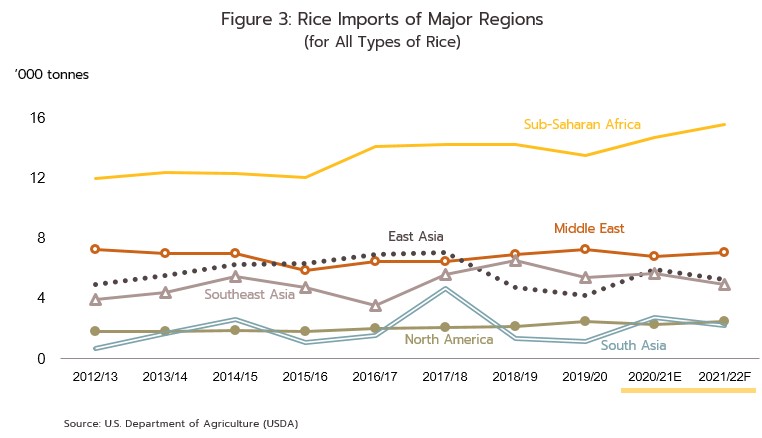

Thailand is a globally important producer and exporter of rice, and in the 2020/2021 growing season, Thai outputs placed the country 6th in the world rankings of raw production; by volume, Thai-grown rice accounted for 3.7% of global outputs, coming after China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Vietnam, which produced respectively 29.3%, 24.1%, 7.0%, 6.8%, and 5.4% of the global total. Considering just exports, though, Thailand ranked 3rd globally, having an 11.9% share of global markets after India (a 38.9% share) and Vietnam (12.9%), and followed by Pakistan, the US, and China (Figure 1). However, because rice is overwhelmingly grown for domestic consumption and to ensure domestic food security, only 9.7% of global outputs end up on world markets (Figure 2), with exports coming from any surplus that is available after domestic markets have had their share. The result of this is that global supply and demand may be somewhat turbulent, with imports mostly being made by countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia (Figure 3).

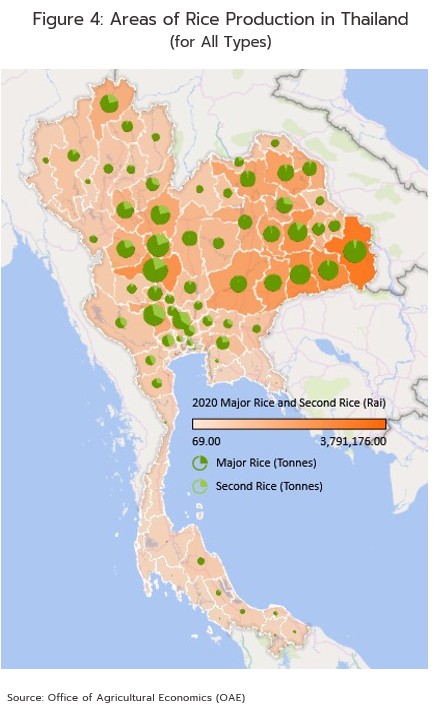

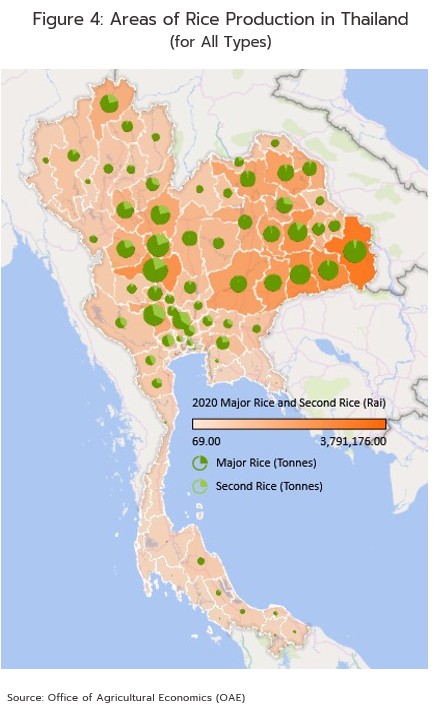

During the 2020/21 growing season [3], rice cultivation covered 68.86 million rai of farmland clustered in the northeastern, lower northern and central parts of the country (Figure 4). Generally, Thai rice is rainfed and so the major growing season begins in May-July (the beginning of the rainy season), with the rice harvested at the end of the year. This is ‘seasonal’ or ‘on-season’ or ‘major’ rice and during the main growing season, regular white rice, Thai jasmine rice and glutinous rice are all grown. 84% of the national output is grown during this period, with the remaining 16% coming from ‘off-season’ or ‘second’ rice grown during the dry season. The latter is dependent on artificial irrigation, and this largely restricts cultivation to the central and northern regions[4], [5].

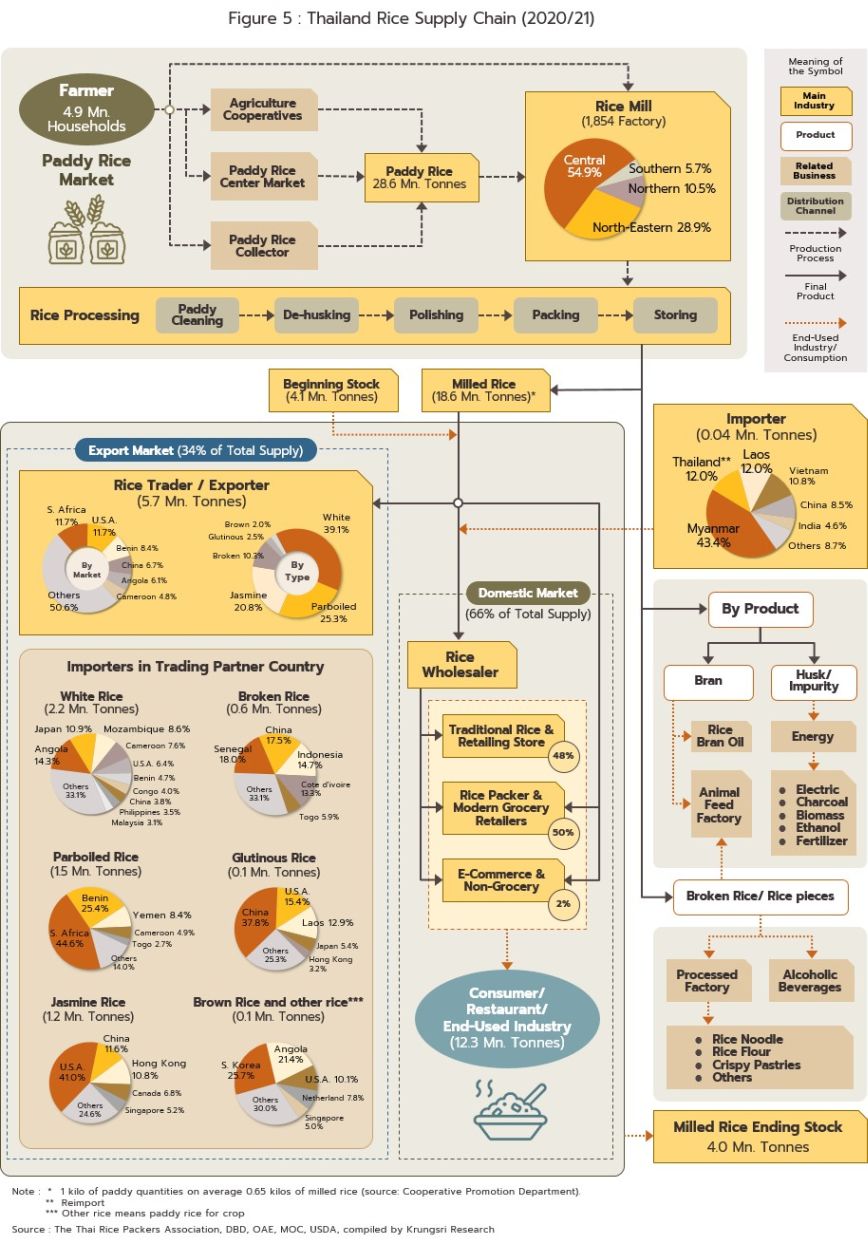

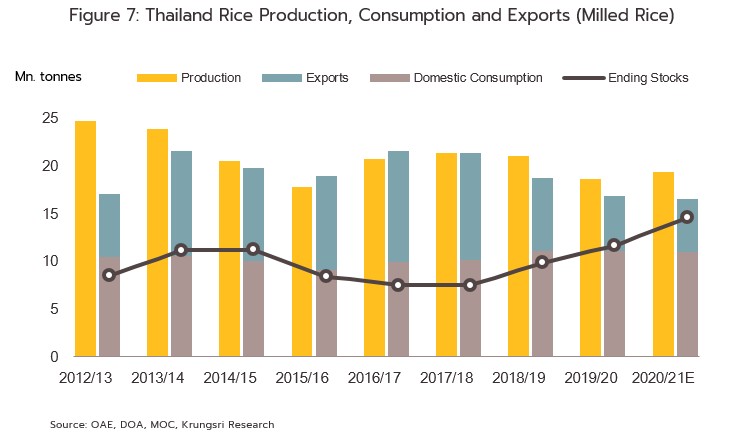

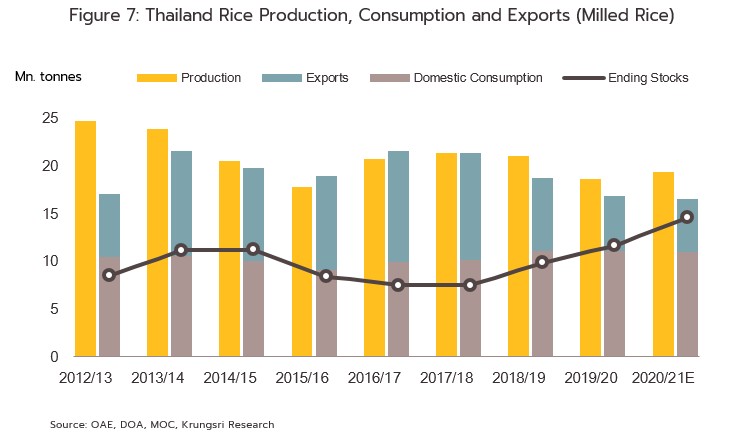

Over the last 10 years, annual outputs of rice paddy have averaged 31-33 million tonnes, which after processing has produced 20-22 million tonnes of milled rice. The domestic market absorbs around 11 million tonnes of this, with the balance either being exported or used to build stocks. This total is split between the following:

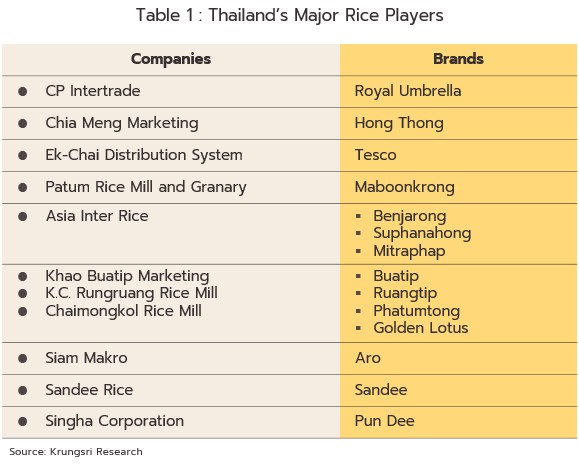

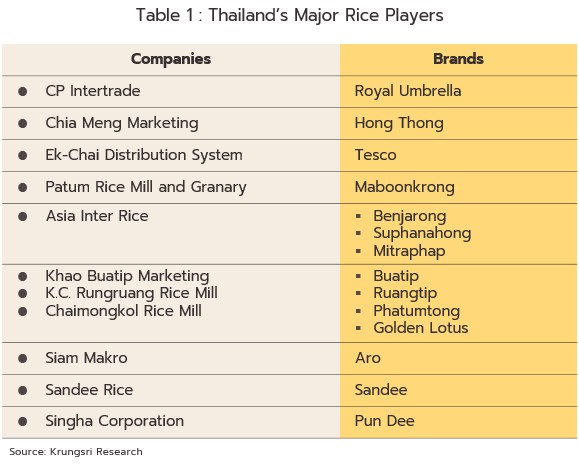

1) Direct consumption: Around 60-70% of the rice that is sold domestically is consumed directly, having been distributed in one of three ways. (i) 50% of rice distributed to Thai consumers is sold pre-packed in bags. Demand for bagged rice has been strengthening for some years with shifting consumption patterns and rising rates of urbanization. In response to this, an increasing number of players have entered the market [6], especially mills and exporters that have turned to the domestic market as a way of reducing exposure to risks arising from uncertainty over fluctuating export income. Players in the modern trade sector, including Ek-Chai Distribution System (selling under the Tesco brand) and Siam Macro (selling under the Aro brand), have also entered the pre-packed rice segment through the sale of house brands [7] (Table 1). These operators have been able to steadily expand their market share through pricing strategies, lower advertising costs, and the advantages that they naturally have in distribution; typically, getting access to shelf space in a modern retail outlet for pre-packed rice entails paying a fee, which naturally they exempt themselves from. (ii) Rice may be sold loose in traditional rice shops. These shops remain the main up-country distribution channel and account for 48% of domestic sales of rice to consumers. (iii) Distribution through non-grocery and e-commerce operations accounts for another 2% of sales.

2) Inputs into downstream industries: About 30-40% of rice sold domestically is used as inputs into other industries, including the production of animal feed, rice flour, rice-based snacks, biomass energy, and ethanol.

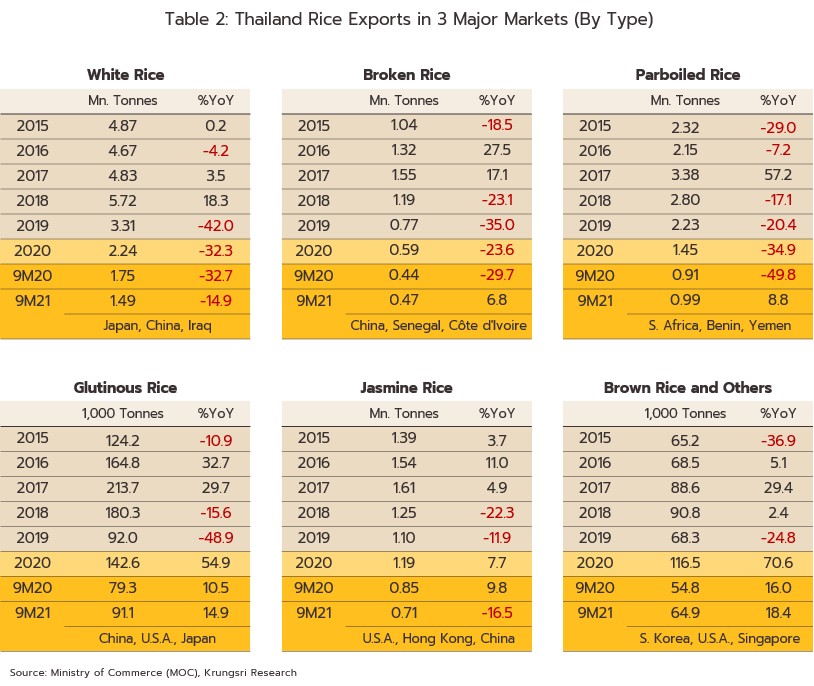

By volume, 2020 exports of Thai rice roughly equaled the quantity of rice consumed domestically. Because Thai rice is recognized globally for its high quality, it is in demand in a large number of countries, though the most important export markets are South Africa, the United States, Benin, the ASEAN region, China, Angola and the Middle East. A wide range of rice products are exported, but the main export categories are in order, white rice, jasmine rice, parboiled rice [8], broken rice, glutinous rice and brown rice (Figure 5 and 6). Individual segments of the export market are described below.

- White rice: Globally, this is the most widely traded type of rice. Thai exports totaled 2.24 million tonnes of milled rice in 2020, or 39.1% of Thai rice exports, with the main export markets in Africa and Asia. Angola was Thailand’s most important purchaser of white rice, taking 14.3% of Thai exports of white rice, followed by Japan (10.9%), Mozambique (8.6%), Cameroon (7.6%), and the US (6.4%). White rice is graded according to the proportion of broken rice that it contains, cheaper varieties containing a higher proportion of this [9].

- Parboiled rice: In 2020, Thailand exported 1.45 million tonnes of milled rice, and parboiled rice therefore accounted for 25.3% of Thai rice exports. Export markets are concentrated in Africa, with the most important of these being South Africa (44.6% of Thai exports of parboiled rice), followed by Benin (25.4%), Yemen (8.4%), Cameroon (4.9%), and Togo (2.7%).

- Jasmine rice: 20.7% of Thai rice exports were of jasmine rice (or 1.19 million tonnes of milled rice). The US was the biggest buyer, taking 41.0% of Thai exports of jasmine rice by volume, followed by China (11.6%), Hong Kong (10.8%), and Canada (6.8%).

- Broken-milled rice [10]: Thailand exported 0.59 million tonnes of broken rice in 2020, which comprised 10.3% of Thai rice exports. These went to Senegal (18.0% of Thai exports of broken rice), China (17.5%), Indonesia (14.7%), and Côte d’Ivoire (13.3%). Broken rice is generally used to produce rice flour and animal feed.

- Glutinous rice: Only 2.5% of Thai rice exports were of glutinous rice (these totaled 0.14 million tonnes of milled rice). The main buyers for this were in China (37.8% of Thai exports of glutinous rice), the US (15.4%), Lao PDR (12.9%) and Japan (5.4%).

- Brown and other types of rice [11]: This was the smallest category of exports and with total 2020 sales of just 0.12 million tonnes of milled rice, it comprised only 2.0% of Thai rice exports. The most important markets were South Korea (25.7% of Thai exports of brown and other types of rice), Angola (21.4%), the US (10.1%) and the Netherlands (7.8%).

SITUATION

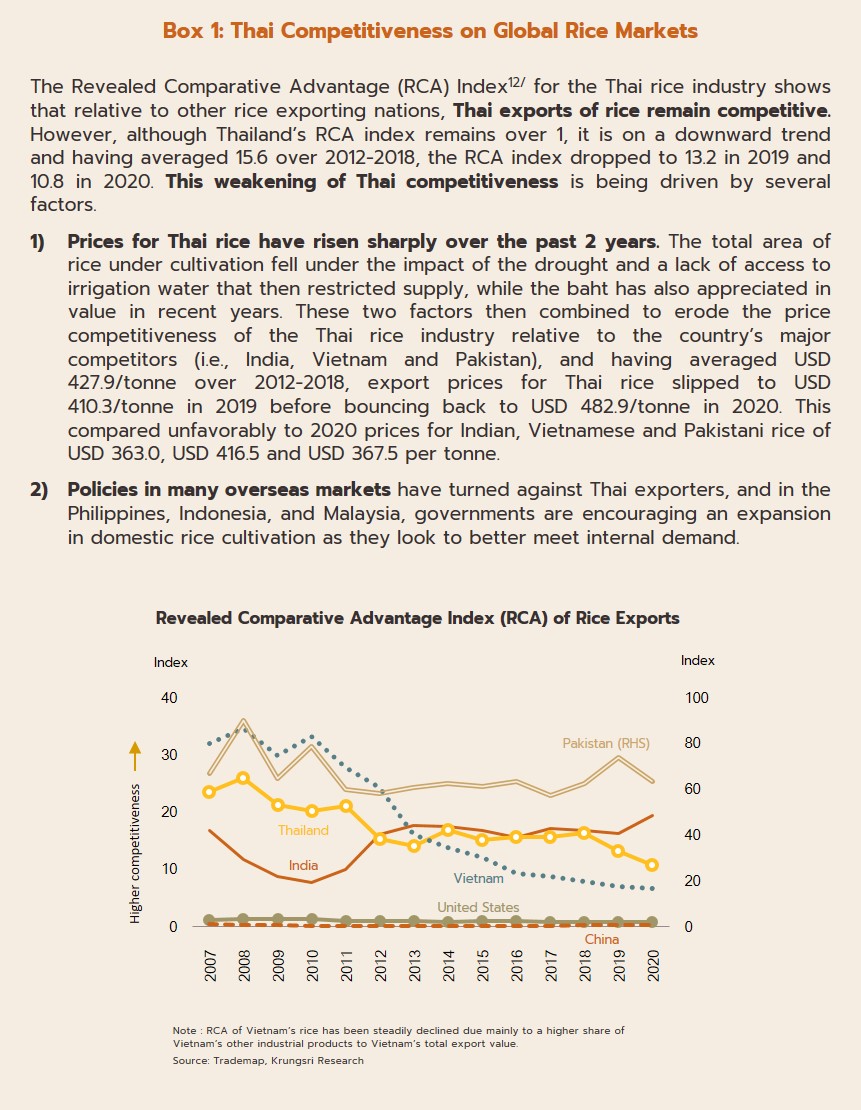

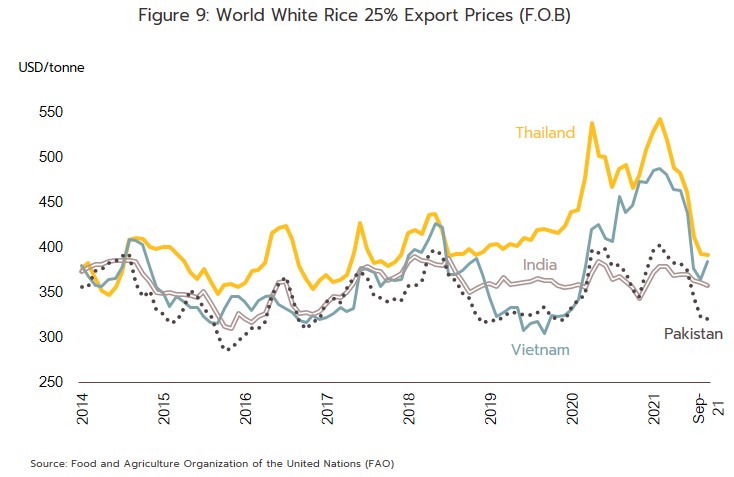

In 2021, both the domestic and export markets contracted with the weakening of consumer purchasing power due to, the depressed economic conditions, and problems with international shipping connected to the shortage of container space and the spike in freight rates. In addition, exports suffered from the high price of Thai rice relative to the country’s competitors (Figure 7).

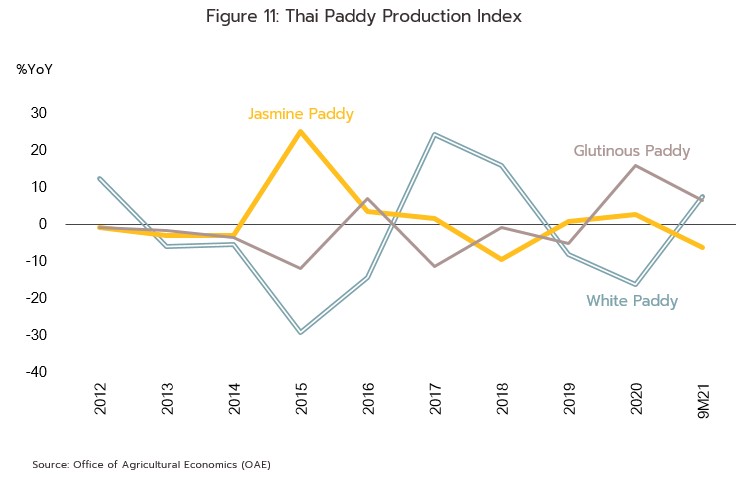

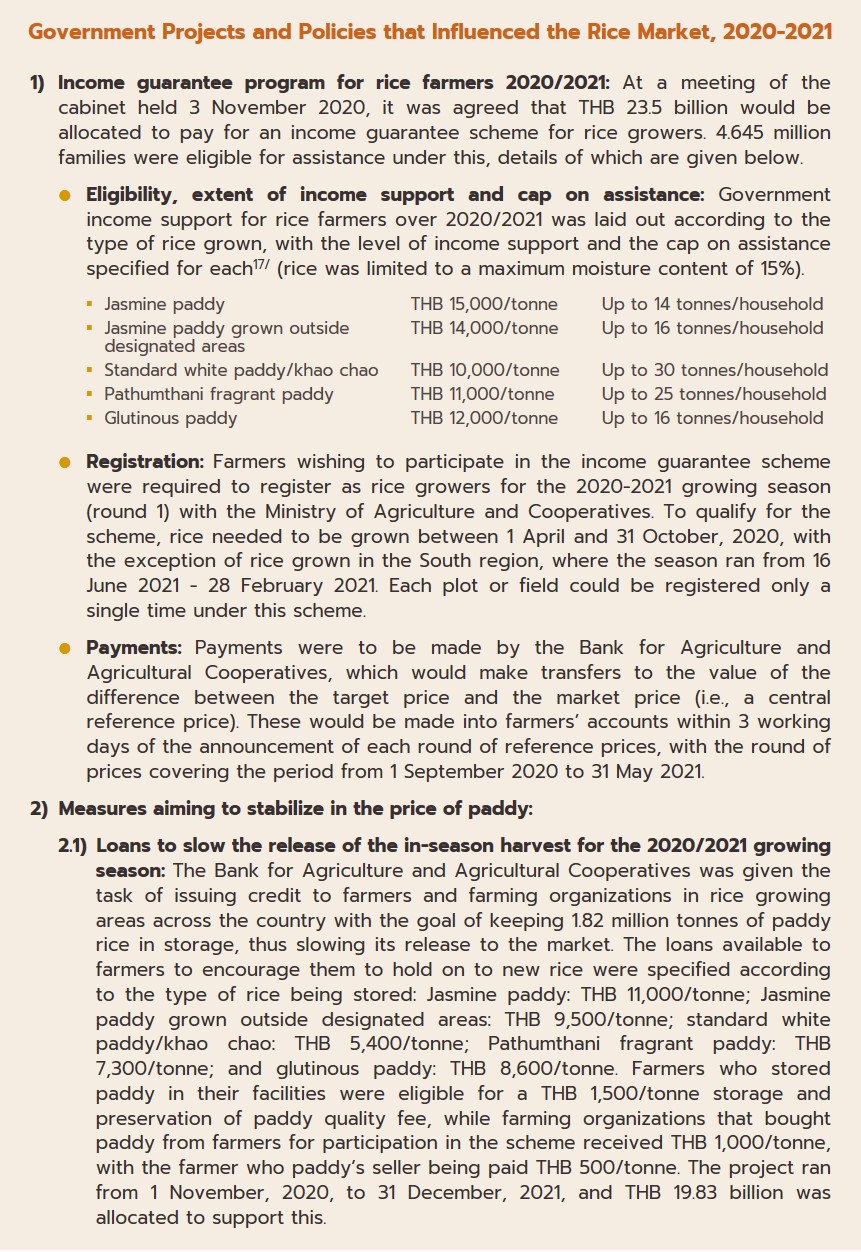

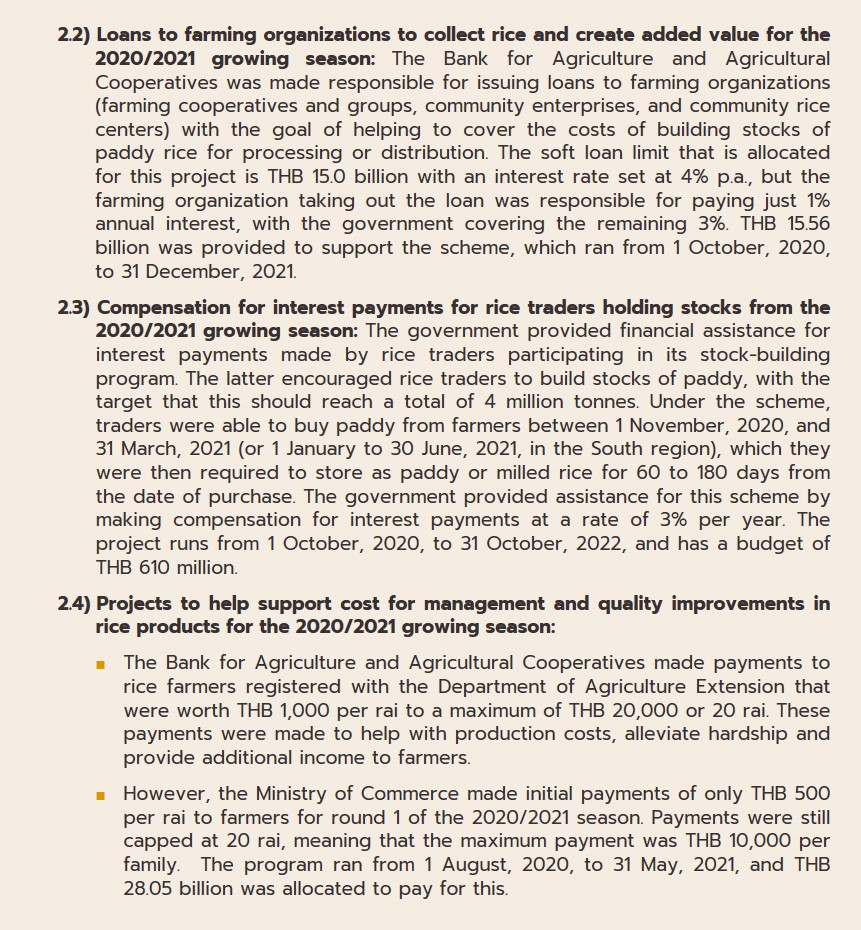

- Rice outputs improved in 2021, rising 4.4% from 2020 to reach 29.9 million tonnes of paddy, or 19.4 million tonnes of milled rice. These improvements can be attributed to several factors. (i) The Office of Agricultural Economics estimates that the total area planted with rice rose 2.6% to 70.3 million rai on (i.i) stronger prices for rice (Figure 8), and (i.ii) the effects of the income guarantee scheme for farmers; and (ii) following the 2020 drought, in 2021, the weather improved and more irrigation water was available, this then pushing up yields by 1.8% YoY to 425.0 kilograms/rai. Nevertheless, some farmers have switched to growing alternative crops, especially sugarcane for sale to downstream industrial consumers in the northeast of the country since prices for this are more attractive.

- Domestic demand softened in the year and dropped 1.5% to an estimated 10.9 million tonnes. (i) The COVID-19 outbreak forced the government to impose strict controls that temporarily banned eat-in dining in restaurants and kept the tourism sector in a severely depressed state. As a result of this, demand from retailers, modern trade outlets, and online sources declined in terms of both volume and value. (ii) Consumer preferences are changing and many individuals are now increasing purchases of alternative foods, including tinned goods and semi-cooked meals that are developed in a wide range of products with attractively priced varieties.

-

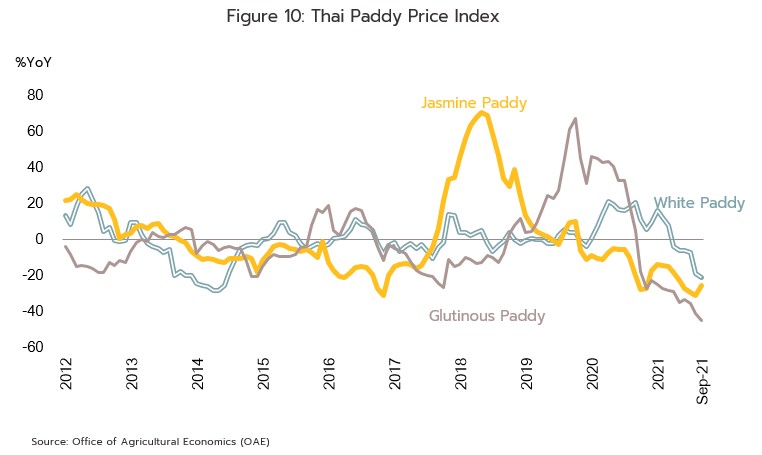

- Domestic rice prices slumped 18.4% YoY over 9M21, with prices down 3.8% YoY to THB 8,550/tonne for white rice, -22.3% YoY to THB 11,067/tonne for jasmine rice, and -33.5% YoY to THB 10,127/tonne for glutinous rice (Figure 8). This was caused by (i) higher outputs, and (ii) the greater use of pricing strategies by operators reacting to stiffer competition. For all of 2021, the price of white rice is expected to average THB 8,000-8,500/tonne (-3% to -9% YoY), while for jasmine and glutinous rice, prices are forecast to drop to respectively THB 10,000-10,500/tonne (-22% to -26%) and THB 9,500-10,000/tonne (-29% to -33%).

- Exports also weakened in the year and for 9M21, these dropped -6.6% YoY to 3.8 million tonnes of milled rice, though by value, the decline was at the much sharper rate of -17.9% YoY (to USD 2.2 billion). This worsening outlook was caused by: (i) the high price of Thai rice on global markets, and although this is softening, prices of Thai rice remained higher than the country’s major competitors such as Vietnam, India, Pakistan and China (which ran down stocks of older rice) (Figure 9); (ii) the shortage of container space and the strict public health measures in place controlling the offloading of goods in ports worldwide, though especially in the US region’s route; and (iii) the growing preference in many markets for soft rice from Vietnam, where the authorities are aggressively improving the quality of their exports. However, despite these clouds, exports to Thailand’s most important markets in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia all tended to improve over 2H21 as rice stocks in these countries ran down and had to be replaced. In light of this, overall exports for 2021 will likely decline by just 2.7%, slipping to 5.6 million tonnes. Details for individual segments are given below.

White rice: Over 9M21, exports of white rice totaled 1.5 million tonnes and generated receipts of USD 785.5 million, though these figures represent declines by volume and value of -14.9% YoY and -15.9% YoY. This sharp drop in exports was partly driven by the high price of Thai white rice, and although this remained relatively stable at USD 538.9/tonne, this was higher than the price of Vietnamese, Indian and Pakistani rice (Figure 9). In addition, overseas sales were hampered by the shortage of container space and the resulting high freight charges. By area, the most important export target for Thai suppliers of white rice is Africa with a 31.5% share of all Thailand’s white rice exports, though by country, the most important markets are Japan (13.7%), China (9.5%), Iraq (9.2%), Mozambique (8.9%), and Cameroon (8.1%).

For all of 2021, Thailand’s white rice exports are expected to be down -8.3% to 2.1 million tonnes.

Jasmine rice: Through 9M21, exports slumped 16.5% YoY by volume to 0.7 million tonnes, but by value, the decline accelerated to 32.5% (or USD 664.5 million). This steep drop-off was caused by: (i) the impact of COVID-19 on consumer spending power and the subsequent weakening in demand for premium-grade rice; (ii) a shift in demand towards soft rice; and (iii) the shortage of shipping containers and high sea freight charges that then pushed up transportation costs for exporters selling into the US region, the main export market for Thai jasmine rice. Over the period, export prices also dropped 19.2% YoY, falling from USD 1,158.8/tonne in 2020 to USD 936.8/tonne. The most significant market for jasmine rice is the US (this takes 41.6% of all exports of jasmine rice from Thailand), followed by Hong Kong (12.8%), China (6.1%), Canada (5.6%), and Singapore (5.2%). It is likely that Thailand’s jasmine rice export markets strengthened in the last quarter of 2021, and so for the year overall, exports are forecast to be down 7.2% to 1.1 million tonnes.

Parboiled rice: Exports of parboiled rice climbed 8.8% YoY by volume and 7.5% YoY by value in 9M21 to totals of respectively 1.0 million tonnes and USD 454.7 million. In the second half of the year, export prices rose 1.8% YoY to an average of USD 475.8/tonne, making Thai prices roughly equivalent to those of Indian exports (Thailand’s major competitor), and as such, demand from Africa (the source of 83.3% of Thailand’s parboiled rice exports) and the Middle East strengthened. By individual country, the main export markets are South Africa (54.0%), Benin (14.9%), Yemen (12.6%), Niger (7.4%), and Cameroon (4.8%). For all of 2021, parboiled rice exports are forecast to be up 10.9% to 1.6 million tonnes.

Broken-milled rice[16]: Exports climbed 6.8% YoY to 0.5 million tonnes in 9M21, though receipts from these dropped 9.9% YoY to USD 214.2 million. Overseas sales were boosted by a steep fall in prices that lifted sales at the end of Q2, especially those to China and Ghana, and at USD 461.5/tonne, prices for broken rice were down 15.1% YoY from their 2020 level of USD 543.5/tonne (15.8% YoY). By area, most sales were to Africa, which absorbs 48.9% of all exports of broken rice, but by country, the most important markets were China (26.9%), Senegal (20.9%), Côte d’Ivoire (10.8%), Indonesia (9.8%), and Ghana (4.9%). Total 2021 overseas sales are expected to strengthen by 8.8% to 0.6 million tonnes.

Glutinous rice: In 9M21, overseas sales of glutinous rice rose 14.9% YoY to 0.09 million tonnes, though income from this dropped 25.4% YoY to USD 66.2 million. High prices for glutinous rice in 2019 and 2020 incentivized farmers to expand the area planted, but this additional supply then drove down prices (figures 10 and 11), and with export prices sliding from USD 1,136.3/tonne in 2020 to USD 725.1/tonne (-36.2% YoY), income naturally slumped too. The main markets for Thai glutinous rice are China (39.4%), the US (15.3%), Japan (6.0%), Vietnam (4.9%), and Singapore (4.0%). F

or the year overall, the expectation is that glutinous rice exports will be up 15.4% to 0.2 million tonnes.

Brown rice and other rice products: Exports of this product category jumped 18.4% YoY to 0.06 million tonnes in 9M21. Sales were driven principally by demand from buyers in developed economies (especially in North America and Europe), where consumer interest in personal health and a desire to buy more nutritional food supports stronger sales of brown rice. In addition, the segment benefited from falling raw material (paddy) export prices, export prices which went from USD 1,066.2/tonne in 2020 to USD 958.5/tonne (-10.1% YoY), though this decline also had the effect of pulling receipts from these exports down to USD 50.9 million (also -10.1% YoY). The main markets for this category are South Korea (27.9% of Thailand’s brown rice and other rice products exports), the US (14.8%), Singapore (10.1%), Italy (5.8%), and Hong Kong (5.7%).

Overall, overseas sales are expected to rise 15.8% in 2021 to 0.13 million tonnes.

OUTLOOK

[1] Data on agricultural land use comes from the Office of Agricultural Economics

[2] Data on the number of households planting on- and off-season rice in 2019/20 comes from the Department of Internal Trade, the Office of Agricultural Economics, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives.

[3] 2020 outputs are calculated from 2020 off-season rice (planted in 2019-2020) and 2020 seasonal rice (planted in 2020-2021).

[4] Seasonal rice is generally grown from strains that produce grain on a predictable timetable since these varieties use the day length to determine their growth, and as the days shorten (i.e., as the climate moves from the rainy season into winter), seasonal rice varieties will switch from vegetative growth to reproduction. These types of rice are thus classified as ‘photoperiod sensitive’, and in Thailand, favored varieties include Khao Dawk Mali 105, RD 15, RD 6, and Prachinburi 1. However, because of the time of year during which off-season rice is grown, day length is not an appropriate determinate of the growing cycle, and so growers instead use rice that produces grain after a fixed period of time (generally 90-150 days) regardless of the planting season. Preferred varieties include Phitsanulok 2, Suphanburi 1, Pathumthani 1, and Chainat 1.

[5] The main irrigated areas in Thailand (accounting for 80-90% of all the country’s irrigated areas) receive water from the Bhumibol and Sirikit dams, which are located in the Chao Phraya watershed.

[6] In 2020, over 100 brands were registered with the Thai Rice Packers Association. This does not include the considerable number of exporters, mills, modern trade operations, small-scale producers, community groups, agricultural cooperatives, individual farmers, and other operators that are not registered with the association but which are carrying out their own branding and promotion.

[7] House brands are products that are sold under the brand of the parent retailer. Generally, this is produced by outside manufacturers operating on contract for the retailer, and usually house brands are sold at a discount relative to national brands.

[8] Parboiled rice is prepared by soaking paddy rice until it has a moisture level of 30-40%. It is then steamed or boiled until cooked, dehydrated and then milled to remove the husk. The parboiling process improves the quality of the milling, reduces the proportion of broken rice, and because the soaking pulls nutrients out of the bran and germ and into the grain, it also raises the final product’s nutritional value. Parboiling gives the rice a pale-yellow color.

[9] In line with the 1997 Ministry of Commerce guidelines on rice quality, sample grades are as follows: (i) 100% rice is the highest quality (e.g. Level 1 100% white rice contains not more than 4% broken rice); (ii) 5% rice is 5-7% broken rice; and (iii) 25% rice is 25-28% broken rice.

[10] Broken-milled rice is rice broken during the manufacturing process. The broken kernels have the length from 2.5 parts onwards but not reach the length of the head rice. and include split rice kernels with less than 80% of the kernels remaining.

[11] Brown rice comprises 88% of this category, with the remainder consisting of other types of rice, including rice seed for planting

[12] The RCA indicates the value of Thai exports of rice as a proportion of the global total. An RCA value less than/equal to/greater than 1 shows that competitiveness is less than/equal to/greater than competitors on global markets.

[13] Vietnamese soft rice is better than standard white rice, and is in fact nearby in quality to Thai jasmine rice, while having the advantage of being cheaper than the latter.

[14] Hybrid rice is created by breeding from different parent strains, and the resulting hybrid may have superior qualities to either parent, e.g., by producing higher outputs, or by being healthier, more drought resistant, or less prone to disease.

[15] Using bio-technology involves the introduction of material from one organism into another with the goal of improving the recipient organism’s function in some way. This can involve altering the plant tissue or using gene editing technologies. When applied to rice, bio-technology may be used to improve its breeding, or its resistance to pests and disease

[16] Most broken-milled rice is imported for production of 25% rice but it is also used in the production of animal feed, rice flour and beer.

[17] 18 varieties of quick-growing rice were excluded from the scheme: 75, C-75, rachini, phuang thong, phuang ngern, phuang ngern phuang thong, phuang kaew, khao pum, sampran 1, chao phraya (039 or PSLC02001-240), phothong, khao khlong luang, Malaysia, Tia Malay, khao Malay, Malay daeng, Batong, and e-lep. All other similar quick-growing varieties were also excluded.

[18] On 18 June, 2019, the cabinet gave the go-ahead to the 20-year water resource management plan (2018-2037). This aims to solve long-running national problems with water management and to develop access to national water resources. The plan is being implemented primarily by the Office of National Water Resources, and has 6 main concerns: (i) managing water supplies for general use; (ii) providing security of supply to the agricultural and industrial sector; (iii) managing floods and flood prevention; (iv) managing water quality and preserving water resources; (v) preserving and reviving degraded forests in watersheds and preventing soil loss; and; (vi) general management of water resources.

.webp.aspx)