- Between 2019 and 2021, outputs of Thai rice will tend to rise slightly. Through these three years, although drought at the beginning of the main planting season may cut some production in 2019, higher prices will incentivize farmers to expand the area under cultivation and/or to increase the number of plantings they make during the years. As regards exports, the total volume will likely decline following the final running down of government rice stocks, but export prices will remain strong on the high quality of Thai rice that meet demand in export markets, although global rice stocks continue to increase. With high export price, it is still expected that the value of rice exports will rise overall.

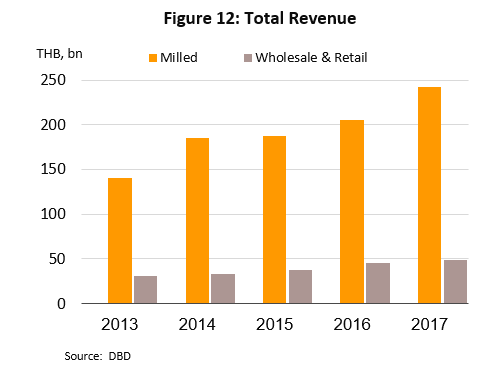

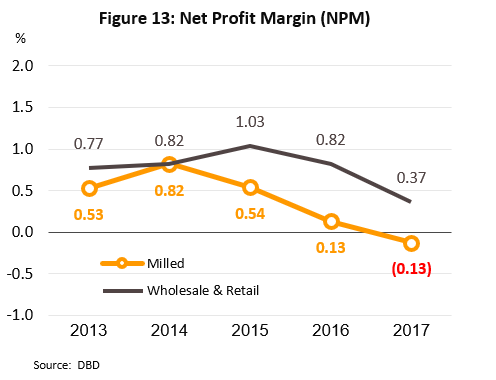

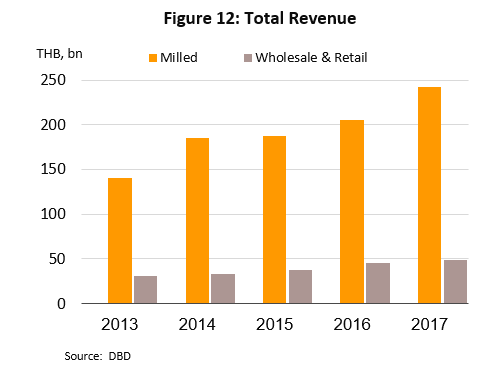

- Given these likely trends, rice exporters will still be able to remain profitable. However, some players especially rice mills, silo operators and independent rice retailers, are expected to encounter rising competition due to high levels of overcapacity.

Overview

Rice is a major cash crop which is important both for consumption (as main food of Thai people) and export (as a major agricultural export product of Thailand). Given its role as a vital economic crop, rice naturally has a central place in the provincial economy. In terms of land under cultivation, rice is Thailand’s most planted crop, taking 45.2% of all Thai farmland, and a total of 4.3 million Thai households (74.4% of agriculture household share1/). The overarching importance of rice has naturally led governments of all types to pay special attention to rice farmers and their needs, and a wide range of policies to help rice farmers have been tried out over the years. These have included 1) price-based policies, such as the rice price guarantee scheme, the rice pledging scheme; and 2) other similar policies, together with other forms of help, including financial assistance with production costs for rice farmers and schemes to help with the costs of harvesting and improving rice quality.

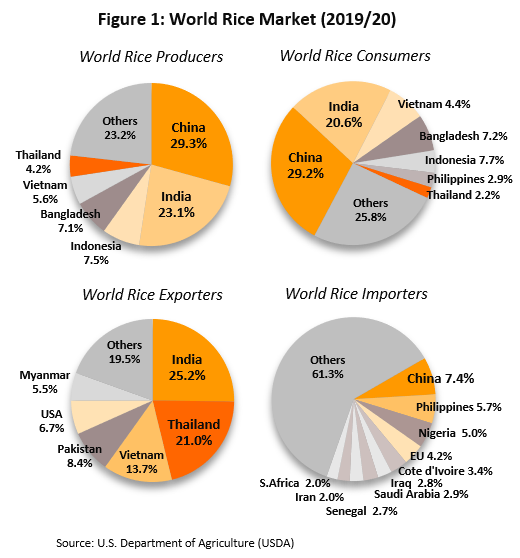

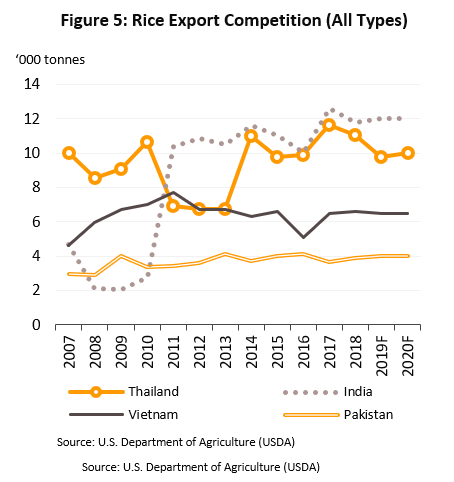

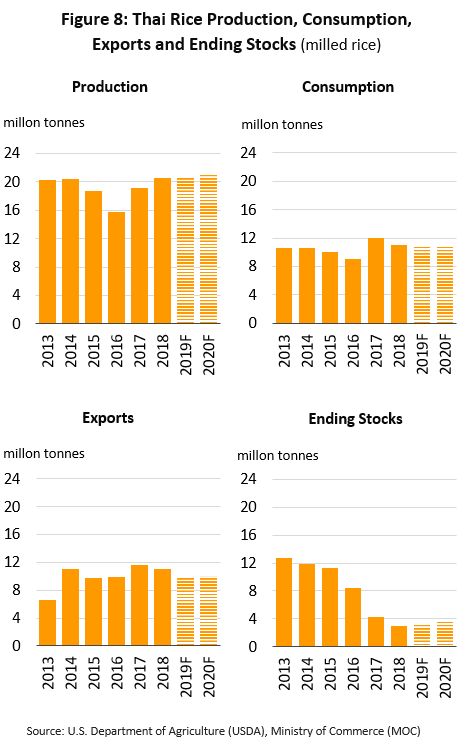

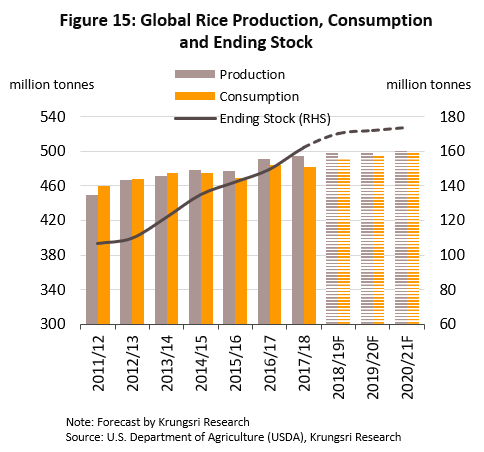

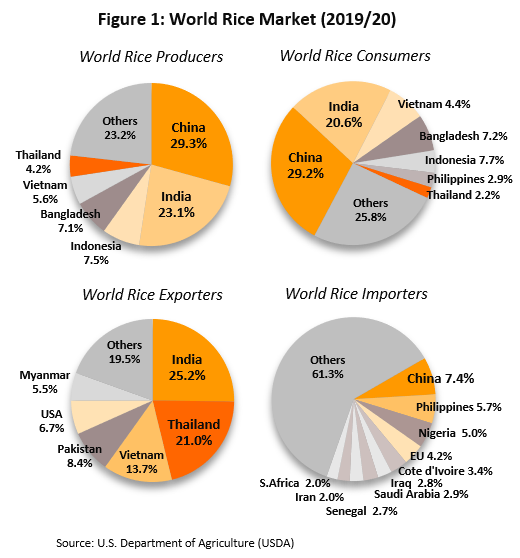

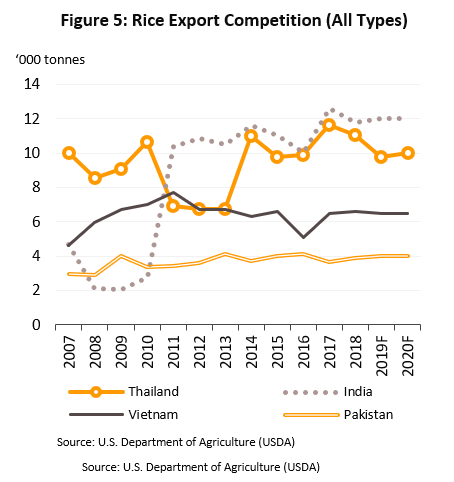

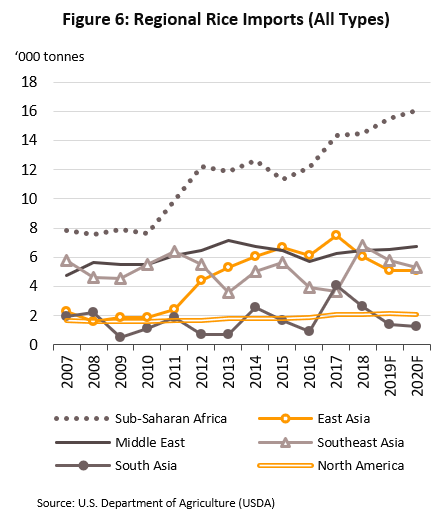

Thailand has long been a globally important producer and exporter of rice and in 2019/2020, Thailand ranked 6th in the world in terms of the total yield of milled rice. Last year, Thai output represented 4.2% of global yields, with Thailand coming behind China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Vietnam, countries that produced 29.3%, 23.1%, 7.5%, 7.1% and 5.6% of the world’s rice, respectively. In terms of exports, however, Thailand sat in 2nd place, accounting for 21.0% of global exports, only slightly behind India, which had a 25.2% market share. Thailand’s other competitors in export markets include Vietnam, Pakistan, the United States and Myanmar (Figure 1). This discrepancy between total yields and exports originates in the fact that rice is mainly planted to provide national food security (i.e. to provide a food source for domestic consumption) so the level of international trade in rice is determined by the degree of surplus production and/or the portion removed from domestic consumption. Thus, only some 9.6% of rice produced worldwide reaches global markets (Figure 2), although the exact amount traded on world exchanges will fluctuate according to yields and demand in producing and exporting nations.

The Thai rice supply chain

The Thai rice supply chain has the following structure:

- The upstream segment consists of rice farmers. Many of these are small-scale farmers and in fact over 4.3 million Thai households are involved in rice cultivation. The output of the upstream segment is paddy rice, also called unmilled rice, and because most rice farmers lack storage facilities, this is usually sold on immediately, although doing so puts growers at a disadvantage when negotiating with distributors. Rice farmers have two main channels through which to sell their rice: they may sell directly to a local mill or they may sell on to or via middlemen such as agricultural cooperatives, paddy rice center market or paddy rice collectors, who will then distribute paddy rice to rice mills at a later date. (Most rice growers do not transport rice directly to mills themselves because of the high costs involved).

- The intermediate segment comprises rice mills, which use unprocessed rice as an input to produce finished, milled rice. Typically, 1 kilo of paddy rice produces 0.6-0.7 kilos of milled rice, although the exact proportion will depend on the strain of rice and the time of harvest (source: Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives). Currently, Thai domestic milling capacity is significantly higher than demand; at more than 100 million tonnes per year, it is in fact more than three times domestic rice output (source: TDRI). Large rice mills, defined as those with a processing capacity of over 20 tonnes paddy rice/day, that have invested in new technology to improve milling techniques and the quality of the rice which they produce and that have their own silos for the storage of rice often benefit for being within the same commercial network as exporters. Alternatively, they may be contracted by major exporters to mill or to process rice bound for export markets and so these operators will have a better market position and will likely be less affected by the national over-supply of milling capacity than will small rice mills (i.e. those with a capacity of less than 20 tonnes paddy rice/day).

- The downstream segment is composed of trading companies that buy rice from mills for distribution to domestic or export markets. Sales may be made through rice brokers (locally called “Yong”), which act as middlemen between rice mills and exporters or domestic distributors. Traditional rice retailing store and manufacturers/distributors of pre-packed rice form the final link in the domestic supply chain, while as regards exports, importers buy produce for distribution to their customers at a later date. Currently, similar quantities of Thai rice are consumed on the domestic and export markets.

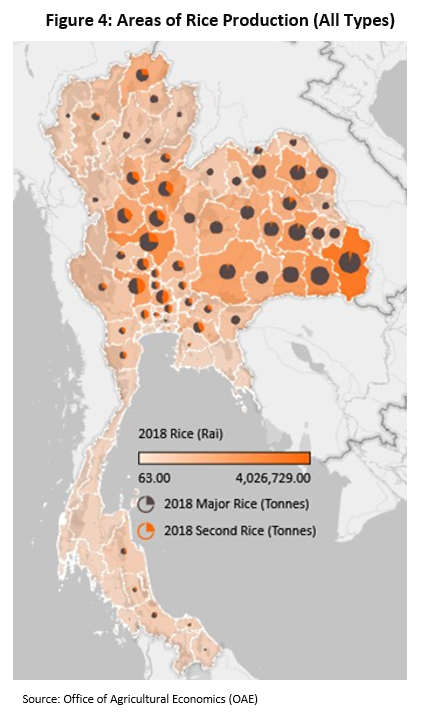

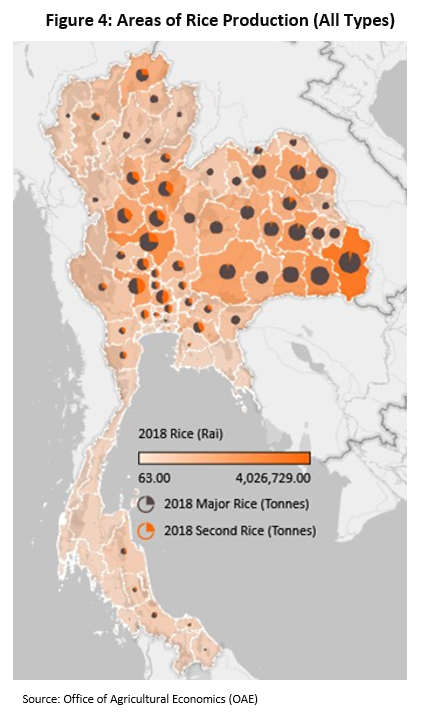

In a crop year 2018/2019, a total of 71.9 million rai of farmland was given over to rice cultivation, most of which was in the lower north, the central region, and the northeast. Thai rice cultivation relies largely on rainfed condition and so the principal annual growing season coincides with the rainy season and runs from July to September, with the harvest occurring at the end of the year. Consisting of a mix of standard white rice, jasmine rice and glutinous (or sticky) rice, this crop comprises over 83% of the annual rice yield in Thailand and is called ‘Major Rice’. This contrasts with ‘Second Rice’ rice, the remaining 17% of annual yields. This crop relies on artificial irrigation and is grown mainly in the north and central regions[2], [3].

In a typical year, average annual outputs of Thai paddy rice run to 31-33 million tonnes, or 20-22 million tonnes of milled rice. Most consumption of rice that used in domestic consumption, accounting for about 53% of total rice production (The rest is exported). Of the rice that is consumed domestically, about 30-40% is used as inputs into other sectors, including the manufacture of animal feed, rice flour, rice-based snacks, biomass-based electricity and ethanol. The remaining 60-70% is consumed directly, although this rice will be distributed in one of two ways. (i) Rice may be sold loose in traditional rice stores. These stores remain the main distribution channel up-country and account for 50-55% of the domestic sales of rice to consumers. (ii) 45-50% of rice is distributed pre-packed in bags. In the past, the Thai market for rice for consumption as a foodstuff was predictable and grew at a steady pace but consumer preference for pre-packed rice has gradually risen as consumption patterns have shifted with increasing urbanization.

In response to this, an increasing number of players have entered the market4/, especially mills and exporters, which have turned to the domestic market and tried to expand their presence there as a way of reducing exposure to risks arising from uncertainty over fluctuating export income. Players in the modern trade sector, including Ek-Chai Distribution System (Tesco brand) and Siam Macro (Aro brand), have also entered the pre-packed rice segment. These operators have been able to steadily expand their market share by the advantages that they naturally have distribution and pricing strategies (no fees for getting access to shelf space in a modern retail outlet and low advertising cost for pre-packed rice under house brands5/, unlike other players).

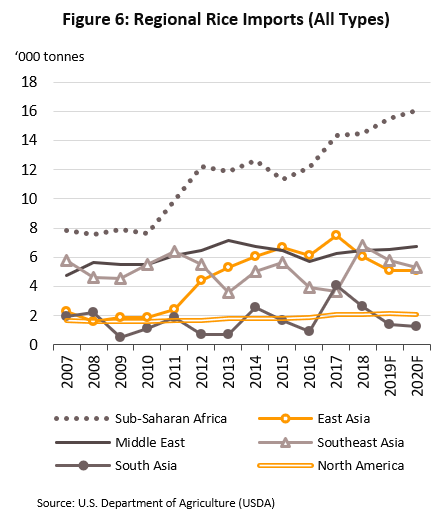

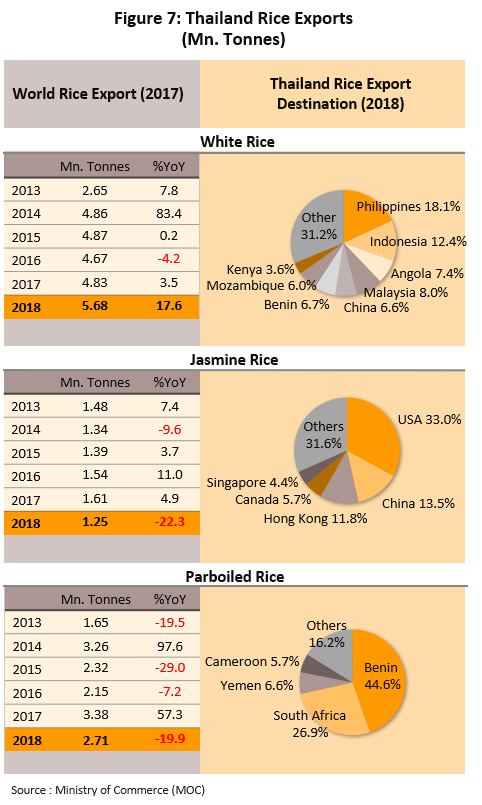

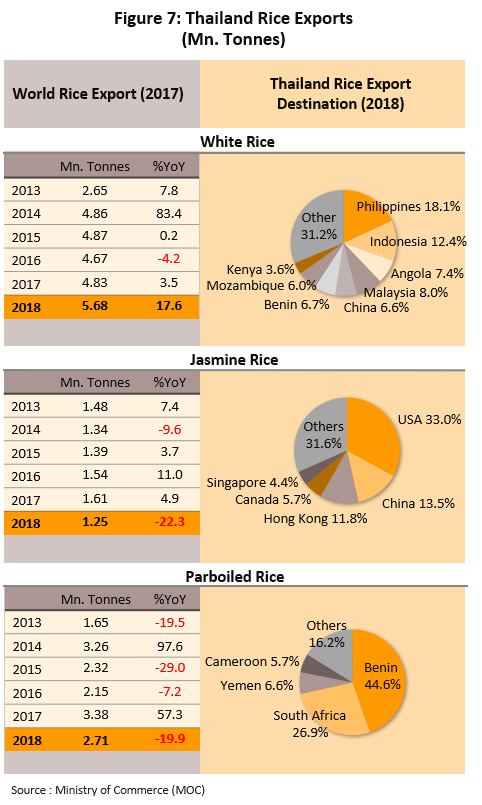

As regards exports of Thai rice, as stated above, the quantity of rice consumed domestically is close to that sent for export. Thai rice is recognized globally for its high quality and as such it is in demand in a large number of countries; Thailand’s most important export markets are Benin, China, the United States, the Africa region, ASEAN and the Middle East. The main export categories are white rice, jasmine rice and parboiled rice. The structure of the export market is described below.

- White rice is a cheap variety of rice and is the most widely traded on global markets, accounting for 55-60% of all rice on world exchanges. White rice is graded and the price of each grade depends on the proportion of broken rice which it contains; cheaper varieties of white rice have a higher proportion of broken grains.[6]

- Around 45-50% of Thai rice exports are of white rice. This translates to some 4.5-5.0 million tonnes of milled rice exported from Thailand annually. The main export markets are in Asia and Africa, though different countries prefer different grades. For example, the Japanese market typically buys 100% white rice, while ASEAN and African customers prefer the next grade down, which is 5-10% white rice.

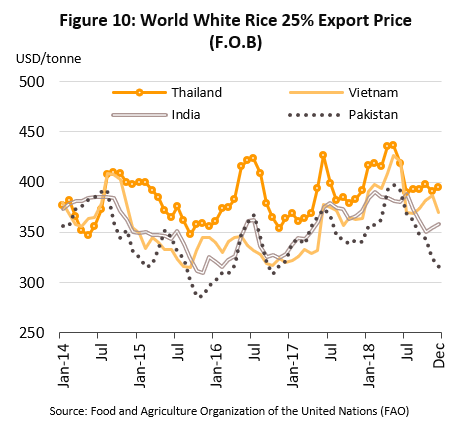

- However, exports of white rice are seeing fairly high levels of competition as India, Vietnam, Cambodia and Myanmar are all able to offer products at a price that is lower than that of Thai products. Markets have thus come to demand goods at this price-point, despite the inferiority of this rice to Thai exports. In addition, the market is currently also showing a greater preference for soft white rice but only 10% of Thai exports of white rice are of this type. As such, Thailand is losing ground to competitors, especially to Vietnam and Cambodia, which have developed new varieties of softer white rice over the past two to three years. Vietnam, for example, has developed its long grain 5141 and Nang Hua varieties, while Cambodia has worked with China to jointly develop their own new varieties.

- Jasmine rice is a high-quality, high-price product but by volume, annual exports come to only 12-14% of the rice traded on global markets.

- Exports of jasmine rice account for 11-15%7/ of the volume of Thai rice exports. In terms of quantity, this is around 1.3-1.6 million tonnes of jasmine rice sent abroad annually. The most important export markets are the United States, which takes 33% of Thai exports of jasmine rice, China and Hong Kong.

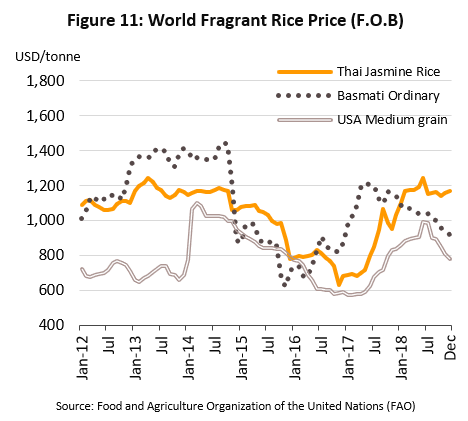

- Thailand is the world’s biggest exporter of jasmine rice but it is facing rising levels of competition from countries that are developing varieties of rice which have similar qualities. Examples of these include Indian basmati rice, a number of different types of American rice, including the Arborio, Black Japonica, Della, Dellrose, Delmont, Jasmati Texmati, and Jazzman varieties, Cambodian jasmine and Phka Rumdoul fragrant rice, and the Vietnamese KDM (Khao Dok Mali) and ST21 varieties.

- Exports of parboiled rice[8] contribute a roughly 14-18% share of all world exports of rice. The major export markets are Africa (which consumes 85% of all parboiled rice globally) and the Middle East.

- Around 23-28% of exports of Thai rice are of parboiled rice, although as a result of fluctuations in the annual Thai rice production and changes in the policies of both the Thai government and the governments of trade partners, there has been a degree of variation in the exact volume of exports.

- Thailand is the world’s second biggest exporter of parboiled rice, and only India[9] exports more. However, India enjoys lower production costs and is able to sell at more attractive prices, so Thai parboiled rice faces competition from Indian products.

In addition to these major categories of rice exports, Thailand also exports 1.1-1.5 million tonnes per year of broken rice[10] for use in the production of rice flour and animal feed (China and Africa are the most important consumers of this). Glutinous rice and brown rice are also bought by overseas buyers, but these types of rice are mainly consumed on the domestic market so exports of these combined come to only 0.3-0.4 million tonnes/year.

Given the above outline of the situation with regards to outputs and trade in the world market, it is clear that competition is multiplying on global rice exchanges and this is having an effect on the Thai rice sector because it is dependent on a relatively high level of exports which still have to rely on the export market around 47% of the total output. In addition, players in the rice sector have seen significant fluctuations in rice yields and prices, caused by a number of factors. (i) In importing countries, many governments have encouraged a domestic expansion in the total own area of rice cultivated in order to be better able to meet demand. (ii) Increasing variability in climatic conditions is having an impact on the global rice harvest. (iii) Thai government’s policies on Thai rice price that has hindered Thai products competitiveness in the world markets.

Situation

Thailand domestic consumption is relatively stable, running at an average of around 10.0-11.0 million tonnes/year (source: USDA) but in 2017, the market was boosted by short-term factors, when operators in the pre-packed rice segment sold on rice that had been auctioned off from government stocks. The domestic market was also helped by the government auctioning off large quantities of low-quality rice which was not suitable for human consumption (it was used in animal feed and for biomass energy production). As a consequence of this, total domestic consumption rose to 12.0 million tonnes for the year.

Thailand rice industries have fluctuated somewhat in the recent past and the historical situation is summarized below.

- In 2012 and 2013, the then government operated its famous rice pledging scheme. Under this, the government offered to purchase paddy rice from growers at a price that was set above the prevailing rates, though the result of this was to distort the market and for the government to become the largest buyer and so to assume monopolistic purchasing powers. Because the government bought at a price that was higher than that then set by global exchanges, farmers were encouraged to sell their crop to the government under the rice pledging scheme, rather than to rice mills or rice traders, as would normally happen. An analysis of the available data shows that during the 2011/2012 and 2012/2013 growing seasons, a total of respectively 21.7 million tonnes and 22.5 million tonnes of paddy rice was sold to the government, compared to the figure for 2008/2009 of 9.8 million tonnes, the prior maximum for purchases made under any Thai government-backed rice pledging scheme. This state of affairs then had knock-on consequences for private sector players in the rice sector, including farmers, whose normal business operations were severely disrupted. Because of the sharp drop in the quantity of rice available on the open market, rice traders had difficulties buying sufficient stocks and some operations had to cease trading as a result11/. At the same time, mills had to revamp their operations and switch to working on contract to the government instead, milling and storing rice for the public sector, which then prompted significant investments to be made in the expansion of silo capacity[11]. Meanwhile, exporters also had to contend with rising export costs that made it difficult for them to compete on world markets[12]. while at times it became impossible for them to source rice at all for export. Instead of relying on the Thai market for supplies, exporters were forced instead to turn to buying greater quantities of rice in neighboring countries but despite this, exports in 2012-2013 fell to just 6.6-6.7 million tonnes, compared to 10.7 million tonnes in 2011. In terms of value, exports in 2012 and 2013 came to USD 4,628 mn and USD 4,419 mn, respectively.

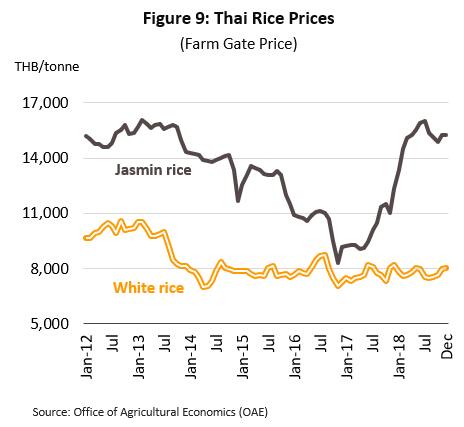

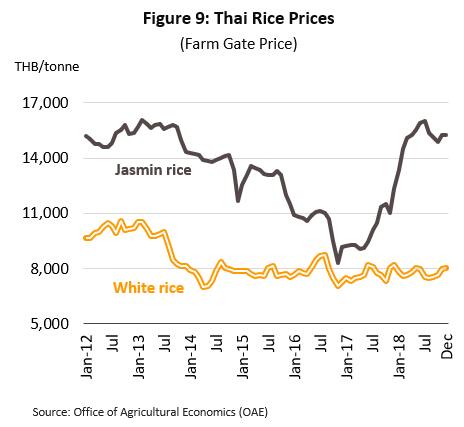

- Between 2014 and 2016, following the termination of the every grain of rice pledging scheme, the volume of rice held in government stocks was exceptionally high and at the start of 2014, stocks hit 17.76 million tonnes, a new record. Of this, 12.2 million tonnes was rice suitable for general consumption[13] (compared with stocks of milled rice which normally total 4-6 million tonnes/year), with the remainder being low-quality rice unfit for human consumption (this is typically used as an input for further processing by related industries). With such a large overhang of rice, the government needed to run down this stock rapidly, which it did partly by negotiating government-to-government (G-to-G) deals, under which Thai rice was sent to a large number of countries including China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Iraq and Iran. The government also steadily auctioned off its rice stock to bidders from the private sector. In addition to these measures, the return of more normal conditions to the rice sector also helped business conditions for rice traders to swing back to positive territory and operators’ income recovered on a higher volume of trade. Meanwhile, rice mills and exporters were able to source rice in the new growing season at a price that had fallen back in line with market prices (Figure 9) and so the export price of Thai rice was able to return to a level that was more competitive. The main losers in this period were silo operators, who were saddled with a large oversupply of storage capacity once the government had run down its stock and because of this, incomes for silo owners declined steadily. Yields of rice in Thailand were also subject to large swings over this period as a consequence of climatic variations. The result of this on exports is described below.

- In 2014, exports of rice rose on improved domestic outputs and, at the end of the year, the beginning of the release of government rice stocks. Through the year, the weather was generally favorable to agriculture and this and the high price of rice in 2013 encouraged farmers to plant a greater area of rice and/or to increase their plantings in the off-season, the effect of which was then to lift that year’s national rice crop to 36.8 million tonnes of paddy rice. In addition, the government began the slow process of running down its stocks with the release of around 1 million tonnes of rice to the market, and this pushed total exports to 11.0 million tonnes, a jump of 66.0% YoY. However, the average export price for all kinds of rice dropped by -26.1% YoY to USD 499.9/tonne, with the fall in the price of Thai white rice being particularly sharp and bringing its cost close to that of Thailand’s competitors (the difference between exports of Thai white rice and the price of its competitors fell to just USD 4-5/tonne, compared to a gap of USD 100-210/tonne in 2013) (Figure 10). This then helped to boost the value of exports by 23.1% YoY to USD 5.44 bn.

- 2015 and 2016: Over these two years, the release of government stocks helped to maintain earlier levels of exports against declining outputs caused by a severe drought brought about by a particularly strong El Niño. In addition to cutting yields directly, the drought also led to a precipitous decline in the volume of water stored in the nation’s dams and this fall in the amount of water that was available for irrigation caused the farmers to abandon second crop cultivation. As a result, the aggregate outputs of paddy rice for 2016 came to the relatively low figure of only 28.3 million tonnes. However, because this coincided with the distribution of some 8 million tonnes of government rice stocks in 2015 and 2016, exports remained at a high level and over these two years averaged 9.8-9.9 million tonnes per year. The average price realized by rice exports fell steadily to USD 477.2/tonne (down -4.5% YoY) and USD 449.8/tonne (down -5.7% YoY), respectively. This was partly caused by the continuing sale of older, lower quality rice (rice remaining from earlier purchases by the government that was sold abroad at auction) and increasing competition on world markets, and these factors combined to cut the value of exports by -15.2% YoY in 2015 to USD 4.61 bn and then by another -4.4% YoY in 2016 to USD 4.41 bn.

- In both 2017 and 2018, Thai rice outputs rose substantially, while continuing efforts to sell off government stocks helped to boost exports to high levels. In the two years, generally beneficial climatic conditions and the maintenance of sufficient water in reservoirs to support the outputs of paddy rice to increase to 31.6 million tonnes (up 11.3% YoY) in 2017 and then to 32.2 million tonnes (up 2.0% YoY) in 2018. At the same time, the government tried to reduce its rice stocks simultaneously with an increase in demand on world markets time, the government tried to reduce its rice stocks simultaneously with an increase in demand on world markets and in 2017 these together pushed exports up by 17.8% YoY to the historically high level of 11.7 million tonnes, bringing in receipts of USD 5.19 bn (up 17.6% YoY). In 2018, exports fell slightly (down -5.0% YoY) but remained at the still high level of 11.1 million tonnes, while by value, exports in fact rose in the year by 8.3% YoY to USD 5.62 bn. In terms of prices, in 2017 these stood at USD 443.7/tonne before rising by 14.4% YoY to USD 507.7/tonne in 2018.

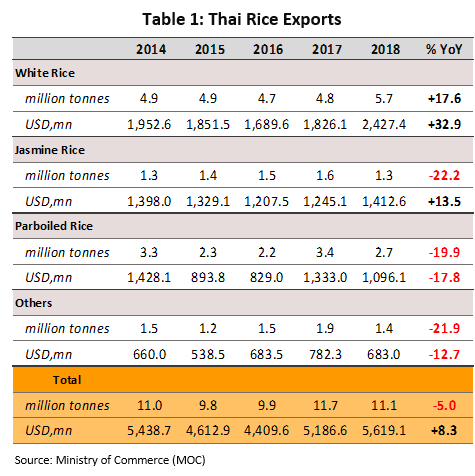

The situation for exports of individual types of rice in 2018 is given below.

- White rice: Exports rose 17.6% YoY to 5.7 million tonnes, which had an average sale price that increased to USD 427.7/tonne from its 2017 price of USD 379.6/tonne (an increase of 12.7% YoY) on greater demand on world markets. This then boosted the total value of exports of white rice by 32.9% YoY to USD 2.42 bn. The majority of exports went to the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Congo and Togo.

- Jasmine rice: The export volume is 1.3 million tonnes (-22.2% YoY), shrinking in line with the global jasmine rice demand. As a result of the price that has risen to USD 1,132.8 /tonne, compared to USD 776.0/tonne in 2017 (+ 46.0% YoY) following the lower supply of rice from the flood in 2017. However, the higher price causing the jasmine rice export value to increase to USD 1,412.6 million (+ 13.5% YoY)

- Parboiled rice: Although prices increased following rises in the cost of the inputs principally used in the preparation of parboiled rice (prices rose 4.6% YoY to USD 407.0/tonne from USD 389.2/tonne in 2017), the volume of exports dropped by -19.9% YoY to 2.7 million tonnes and this cut the value of exports by -17.8% YoY to USD 1.10 bn. Falling demand was behind this decline, especially that from markets in Bangladesh, where the government slapped tariffs on imports at the same time as domestic production improved sufficiently to meet demand from within the country.

- Other types of rice: Details for the volume and value of exports of other types of rice in 2018 are given below.

- Broken rice[14] - Exports of broken rice totaled 1.18 million tonnes (down -24.0% YoY) and brought in income of USD 491.7 m (down -16.9% YoY). Declining demand was seen in almost all of Thailand’s main export markets, including China, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Indonesia, partly became these export markets diverse to buy low quality rice remaining from the earlier rice pledging scheme to industrial uses[15] and the 9.4% YoY average increase in price (up from USD 382.6/tonne in 2017 to USD 418.3/tonne in 2018).

- Glutinous rice - Exports fell -15.3% YoY to 0.18 million tonnes, while income from this fell at the lower rate of -7.2% YoY to a total of USD 121.5 m on a decline in yields caused by the 2017 floods and the switch (driven by more attractive prices) by some rice farmers from glutinous to jasmine rice. Nevertheless, as the discrepancy between the fall in volume and value indicates, this decline in supply supported price rises that pushed the average price for glutinous rice to USD 674.6/tonne from USD 615.9/tonne in 2017 (up 9.5% YoY).

- Brown rice - Both export volume and export prices lifted for this category of goods. In the case of the former, exports increased by 19.4% YoY to 0.16 million tonnes, while with regard to the latter, 8.2% YoY increases were recorded as prices rose to USD 626.9/tonne compared to USD 579.3/tonne in 2017, and as such, total value jumped by 29.2% YoY to USD 98.7 m. This segment benefited strongly from exports to developed economies, particularly the United Kingdom, the United States, Spain, France and Portugal, where there is a bigger market for healthier or more nutritious foods.

Outlook

The forecast for rice outputs in the period 2019-2021 is for growth of just 1-2%, which would translate into an annual harvest of paddy rice in the range of 32.5-33.0 million tonnes, or 21.0-21.8 million tonnes of milled rice (Figure 14). This would then represent a slight increase on the 2018 harvest of 32.2 million tonnes of paddy or 21.2 million tonnes of milled rice. However, for 2019, drought at the onset of the rainy season indicates that yields are likely to fall for the year, although it is expected that in 2020 and 2021, weather conditions, and more particularly rainfall, will be more suitable for the cultivation of rice. In addition, government support for the agricultural sector through its plan to manage water resources and to ensure sufficient supplies for the sector[16] should help alleviate further losses from drought and assist farmers in making more efficient planting plans. Beyond this, though, rice prices, especially those for jasmine rice, remain at the high levels of 2018-2019 and this is providing a strong incentive to farmers to increase the area of rice planted and/or to plant more off-season crops, while government measures that have aimed to encourage farmers to switch from planting rice to growing other vegetables instead[17] have yet to make significant inroads into the farming community.

Domestic demand for rice is expected to be in the high range of 11.0-11.5 million tonnes per year in 2019-2021, compared to total annual demand of 10.8 million tonnes in 2018-2019. Demand will be boosted by rising household consumption (33% of all domestic consumption of rice[19]) and the trend for its increased use as an input into food processing industries, such as snack production (another 10-13% of rice goes to this kind of processing).

For the three years of 2019 to 2021, annual exports of rice from Thailand are expected to average 9-10 million tonnes. This will be somewhat lower than the 2018 total of 11.1 million tonnes resulting from the termination of selling off of rice in the stocks remaining from the rice pledging scheme after the acceleration in 2017-2018. In addition, some buyers are turning to imports of cheaper rice from other countries, especially from China, which is forecast to be a leading source of exports given its excessive domestic stock holdings of 117 million tonnes of rice, which China will be trying to run down through to 2020. Nevertheless, despite these problems in the market, the outlook for exports for 2019-2021 should be seen as a return to more normal levels following the disruption of the rice pledging scheme.

Through the same period, export prices for Thai rice should remain relatively stable at the high levels set in 2018, with this outlook supported by several factors: (i) Demand from rice on the global market should increase steadily; (ii) Although much of the rice exported in the recent past from government stocks was not suitable for direct human consumption, Thai rice is generally of high quality and this will help to maintain high prices, even while global rice stocks increase in size due to additional exports from Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam (Figure 15); and (iii) The impact of drought and the resulting cut in supply will tend to lift prices.

Krungsri Research view

Through 2019-2021, the overall situation in the rice sector is forecast to remain largely unchanged from conditions over the last several years. Exporters will be able to continue generating profits, while turnover for many other players will likely weaken and it will take some time for conditions to improve. This will be particularly the case for mills, silos and retailers of rice, most of which are SMEs and these may continue to feel the effects of an oversupply to the market and strong competition within their segment.

Rice growers: Outputs may increase, though the rise will not be substantial and so growth in income for farmers will be only limited. In addition, farmers will face further problems, including the possibility of receiving lower payments for their rice from middlemen and traders and, at the same time, higher costs, which are expected to rise from THB 10,022/tonne/year in 2018 to THB 10,500-10,600/tonne/year in 2021 (CAGR 2.5-3.0%). Profits will therefore tend to be held back, although the outlook is better for growers of jasmine rice.

Rice mills: The continuing high degree of oversupply of milling capacity will be the main factor weighing on these businesses. Small players will inevitably be most affected by this and some will likely face the risk of insolvency, that result from the government's reduced rice storage service (The result of accelerating the drainage of old rice stock of the government). The competitive group is still a large rice mill that can manage costs well.

Producers of packaged rice: Income for these players will be at a level sufficient to keep them in business. The majority of producers benefit from being large companies that operate through much or all of the supply chain, including milling and exporting, while growth in sales of pre-packed rice within Thailand will also be supported by continuing urbanization and the changing consumer behaviors that come with that. However, the entry of new players to the market is increasing competition on price, meanwhile business costs, for example for marketing and buying space on supermarket shelves, are also rising.

Traditional retailers of rice: Against a backdrop of increasing competition in the packaged rice sector on price, convenience and shelf-life, traditional sellers of rice are expected to lose market share to modern trade outlets, and they will find the competition increasingly hard to overcome.

Rice exporters: Exports of rice from Thailand are expected to fall relative to their levels in 2017-2018, when they were boosted by additional sales of government stocks but despite this, income from exports will tend to increase on rising export prices, especially of jasmine rice. Exporters of white rice will be able to maintain their margins thanks to anticipated stronger demand from trade partners.

Operators of silos: Following the ending of the rice pledging scheme and the completion of efforts to sell off accumulated government rice stocks in 2017 and 2018, operators of silos will likely see their income drop because the market continues to be affected by a significant oversupply of storage capacity (a result of a rush to build out additional storage space to meet higher demand while the rice pledging scheme was operating). In response to this, the competition will be intense and put downward pressure on rental price that would affect business income although the operators try using the spaces for storing other types of crop instead.

[1] Source: Department of Agricultural Extension, Department of Internal Trade, Office of Industrial Economics and National Statistical Office Thailand

[2] Major rice is usually planted mature at fairly predictable times. Its growth cycle runs according to the daily quantity of light that the plant receives. During transition period from the wet season to the winter, the length of the days shorten and these major rice will then divert from growing the main stem to reproducing (i.e. developing rice ears). These types of rice are thus called ‘photoperiod sensitive’ and popular varieties include Khao Dok Mali 105, Ko Kho 15, Ko Kho 6, and Prachinburi 1. Second rice is different in that these varieties typically do not use the sun to time their growth cycle but will instead produce on a fixed calendar, and thus after an average of 120-130 days, it will be possible to harvest, regardless of when the crop was planted. Popular off-season rice varieties include Phitsanulok 2, Suphanburi 1, Pathumthani 1 and Chainat 1.

[3] The main irrigated areas in Thailand (accounting for 80-90% of all the country’s irrigated areas) receive water from the Bhumibol and Sirikit dams, which are located in the catchment area of the Chao Phraya River.

[4] At present, over 150 companies are registered with the Thai Rice Packers Association. There is also a significant number of small provincial operators packing rice that have not registered with the association because many of these are rice farmers bagging their own rice for distribution themselves.

[5] A house brand is an item that is branded as the retailer’s own product. Generally, this will involve a retailer contracting a producer to manufacture goods and package these under the retailer’s brand. These products are then usually sold at lower price-points than those of other national brands.

[6] n line with the 1997 Ministry of Commerce guidelines on Thai rice quality, sample grades are as follows: (i) 100% white rice is the highest quality rice and contains only a very small proportion of broken rice such as 100% white rice grade A contains not more than 4% broken rice; (ii) 5% white rice is 5-7% broken rice; and (iii) 25% white rice is 25-28% broken rice.

[7 The proportion is the export volume during the past 5 years (2014-2018) but the average export value is approximately 24-29% of the total rice export value

[8] Parboiled rice is prepared by soaking paddy rice until it has a moisture level of 30-40%. It is then steamed or boiled until cooked, before being dried and then milled to remove the husk.

[9] India has long been the world’s most important exporter of parboiled rice. This is with the exception of the period 2008-2010, when the Indian government put a halt to exports in order to build up domestic stocks, and during those two years, Thailand briefly became the world’s biggest exporter of parboiled rice.

[10] Broken rice is rice that is damaged during processing.

[11] Data from the analysis of “Advantages and Disadvantages of Rice Pledging Scheme” by “Thailand Research and Development Institute”

[12] In the case of non-glutinous rice, the Thai government set a purchase price for paddy rice of THB 15,000/tonne, or USD 484/tonne. This was higher than the cost of paddy rice in the other major exporting countries at that point in time. For example, the price in the United States was USD 352/tonne, in India it was USD 230/tonne, and in Vietnam it was USD 225/tonne (source: Commission on Agriculture and Cooperatives, National Legislative Assembly).

[13] This includes 2.2 million tonnes of rice that had passed the ‘Premium Grade’ standards and a further 10 million tonnes of rice that had failed to pass the standards but which it was still possible to process to make fit for human consumption. This consisted of 6.26 million tonnes of Grade A rice and 3.74 million tonnes of Grade B rice.

[14] Most of the grits rice are used as a 25% ingredient in rice production. However, there are other industries that use grit rice such as animal feed, flour and beer.

[15] The rice used in most industrial sectors is divided into 2 main groups: rice that is not suitable for people's food, which will be used in the animal feed industry. Rice that is not suitable for consumption, both people and animals will be used in the energy industry such as ethanol, alcohol, biomass, electric power and organic fertilizer, etc.

[16] The cabinet approved the 20-year master plan on water resource management (2018-2037) on 18 June 2019, following the proposal by the Office of the National Water Resources. Its objectives are that to solve, manage and develop Thai water resources throughout the whole system for country’s water security, this master plan comprises 28 strategies and 54 work plans, in six major areas, involving the management of water for consumption, water security in the production sector, water management to tackle floods, water quality and water resource conservation, watershed rehabilitation and soil erosion prevention, and efficient management,

[17] The cabinet has approved the allocation of THB 20 bn to the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives to incentivize farmers to reduce the amount of rice grown in locations that are not suitable for rice cultivation and instead to replace rice with alternative crops, including corn grown as an animal feed (with a target of 2 million rai to be planted) and green manure crops, for which the target is 2,000 new sites. Loans of up to THB 10 mn are available for each participating location, repayable over 5 years (between December 2016 and December 2021) at 0.01% interest

[18] Ratio of paddy rice to milled rice conversion is 1 : 0.66

[19] Most of the rice produced is directly consumed around 33% of all rice is produced. The rest that kept for next crop about 5% , kept 4% of the stock, sent to the processing plant 11% and exported 47%

.webp.aspx)