EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Overall, Thai palm oil industry is expected to see improving conditions through 2022. Supply is benefitting from an expansion in the area under cultivation, the positive incentive provided by strong prices, and better climatic conditions that improved yields, while demand is being lifted by worries over food security that were prompted first by the COVID-19 pandemic and then by the war in Ukraine, which has boosted export orders. However, a softening of demand in downstream industries has undercut distribution to the Thai market. Nonetheless, both domestic and overseas demand is forecast to strengthen over 2023 and 2024. This will come especially from players in the food and oleochemical industries, which will enjoy growth as the economy gradually rebounds with the post-COVID reopening of the economy, and from biodiesel refiners, where greater demand will come from growth in the transport sector. Prices tend to weaken on higher outputs from domestic and overseas producers, especially as output in Indonesia and Malaysia returns to normal, but the high cost of crude will support healthy prices for palm oil.

Krungsri Research view

Overall, the palm oil industry will continue to enjoy positive growth through 2022. Supply will benefit from a combination of an expansion in the area under cultivation and prices that will encourage growers to maximize their harvest, while demand will be boosted by fears over food security brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war that will then lift overseas sales. Through 2023 and 2024, operators will continue to see growth in both domestic and export markets, especially from the food, oleochemical and biodiesel industries. Although prices will tend to soften, crude will likely remain expensive, and this will help to underpin palm oil prices. Over the coming few years, players will therefore remain in profit.

-

Oil Palm growers: Income will tend to rise on steadily strengthening domestic demand, strong prices, and support from the government ensuring that the sell price of palm fruits stays above production costs. Nevertheless, farmers will be exposed to risk in the form of the rising cost of fertilizer and increasing output both at home and abroad, especially in Malaysia and Indonesia, where conditions are returning to their pre-pandemic norms.

-

CPO mills: Through 2022, strong demand in export markets will mean that profitability will improve for mills, while in 2023 and 2024, the outlook will improve further thanks to the forecast strength of both domestic and overseas markets. Help will also come from government moves to support the industry and to raise energy standards, for example by using CPO to produce biodiesel and other higher value-added goods, and to promote an expansion in exports. Nevertheless, national milling capacity exceeds the quantity of palm oil supplied to the market, and this excess in production capacity leads to competition for inputs that then adds to CPO production costs. As such, profitability may come under pressure, and some producers of CPO may have to shoulder periodic stock losses. This will be a particular problem for small, independent operators that are not part of commercial networks that are linked to downstream palm oil refiners.

-

Palm oil refiners: Refiners will continue to see their turnover grow at a healthy rate. Demand for CPO to convert into refined palm oil will expand by 10.0-11.0% annually on recovery in the tourism, hotel and restaurant businesses, which will then trigger greater demand for palm oil products from food industry. Demand from the oleochemical industry for palm oil and fats (produced from the purification of palm oil) is also forecast to rise with improving sales of consumer goods manufactured by downstream industries (e.g., detergent, soap, medicine, and cosmetics).

-

Traders in crops used in the production of vegetable oil/oil palm collection yards: An expansion in the total size of palm plantations and consequently increasing outputs of palm fruit will strengthen income for middlemen. In addition, most palm plantations are small-scale operations that lack bargaining power and so they are dependent on sales to collection yards and traders.

OVERVIEW

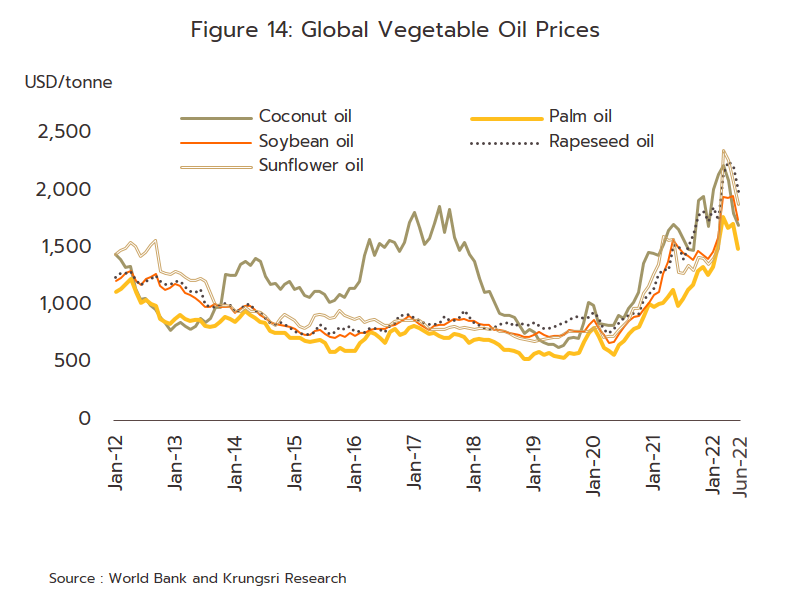

Palm oil[1] is the cheapest vegetable oil to produce, partly because it has yields that are 6-10 times[2] higher than those of other oil crops such as soy, rapeseed, sunflower, coconut and olive.

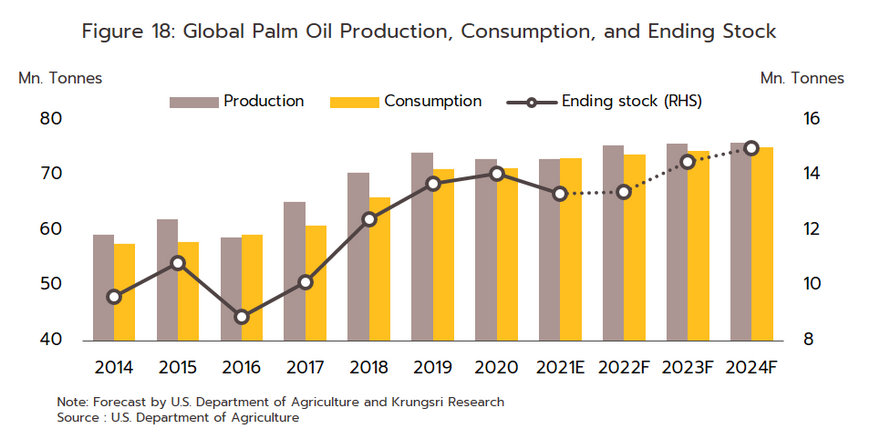

In 2021, global production of palm oil totaled 72.9 million tonnes, while worldwide consumption came to the slightly higher total of 73.5 million tonnes, figures that represent respectively 36.3% and 36.5% of total global vegetable oil production and consumption. The world’s principal palm oil producing region is the ASEAN area, and because they are the most important producers and exporters, Indonesia and Malaysia play a significant role in setting prices on global exchanges; Indonesia produces some 43.5 million tonnes of palm oil annually, while Malaysia contributes another 17.9 million tonnes to world markets and so together, they account for 83.9% of combined global output. Naturally, these two countries are also the world’s major exporters, producing 89.2% of the palm oil bound for international markets. In terms of imports, India is the single biggest market, taking 17.7% of world imports in 2021, followed by China (14.3%), the European Union (13.0%), and Pakistan (7.2%). Over the five years between 2015 and 2019, global demand for crude palm oil (CPO) for both direct consumption and for production of energy grew by an average of 4.8% per year, while production has risen at an annual rate of 2.8%. By the end of 2021, accumulated stocks of crude palm oil stood at a total of 12.9 million tonnes (Figure 1 and Table 1)

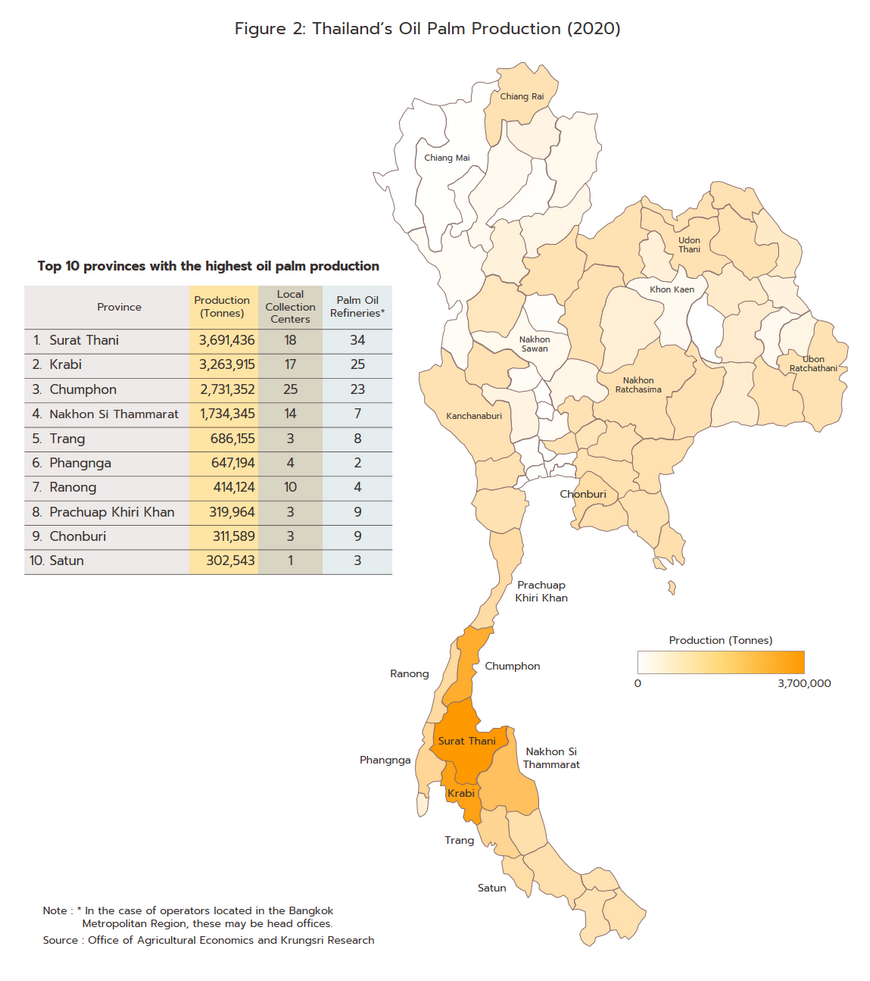

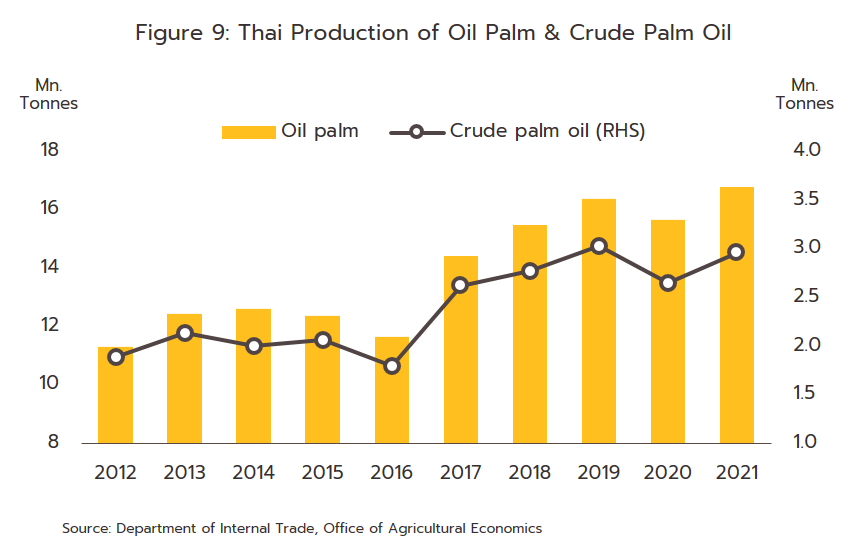

As for Thailand, although the country is in third place in the world palm oil production rankings, its output comes to only 3.8% of the global total. Thai influence on global prices is thus negligible. The industry is very geographically concentrated, and 86.1% of the harvested area of oil palm is in the south of the country[3], clustered in particular in the provinces of Surat Thani, Krabi, and Chumphon, which together are home to some 58.3% of the country’s oil palm plantations. In order of importance, the remainder is found in the center, the northeast and the north of the country (Figure 2). Oil palm cultivation expanded in the decade from 2009-2018 as a consequence of the government’s strategy for developing renewable and alternative energy supplies (The Alternative Energy Development Plan : AEDP), and so in 2021, Thailand’s total harvested area of oil palm came to 5.1 million rai (+3.5% from 2020). In the same year, national output totaled 16.8 million tonnes of oil palm (+7.3%)[4], which was converted into 3.0 million tonnes of crude palm oil (+11.8%) (source: The Office of Agricultural Economics, and Department of Internal Trade).

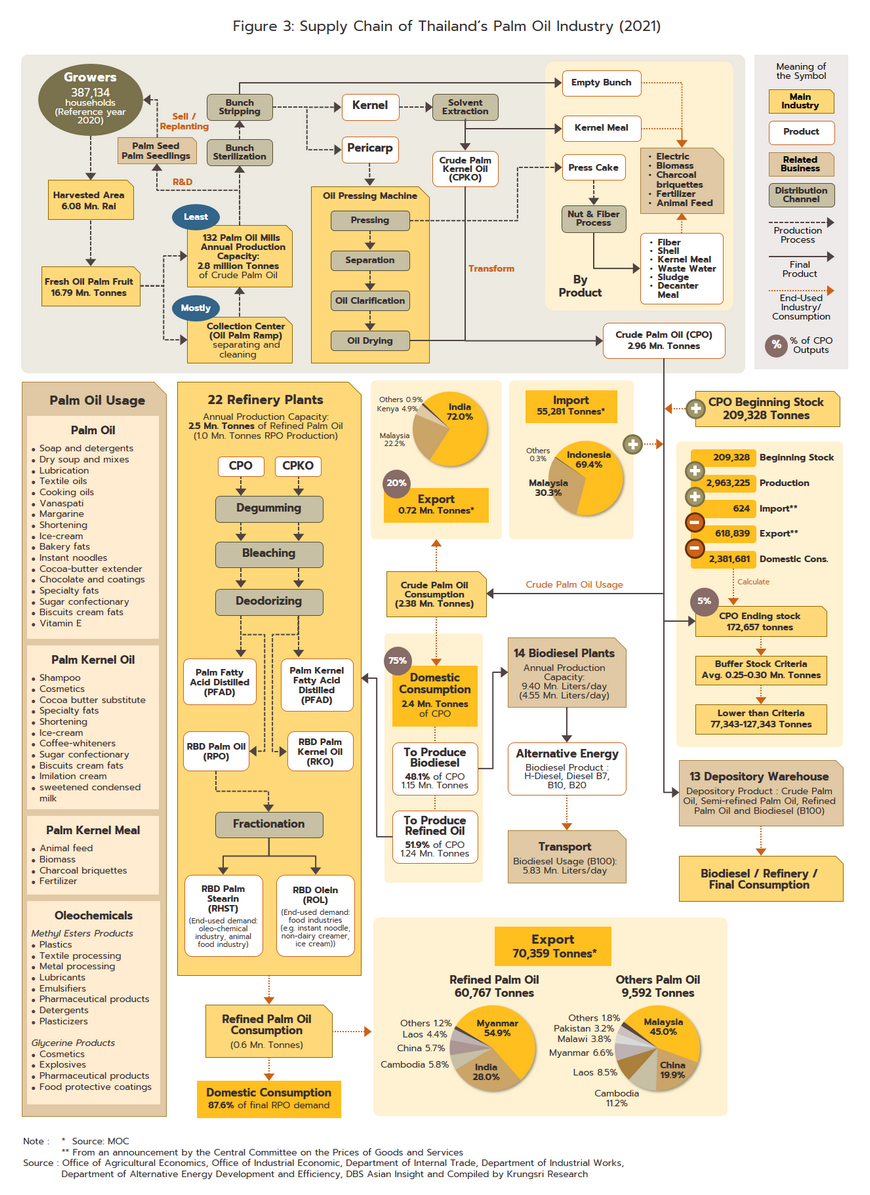

One strength of the Thai palm oil sector is its comprehensive supply chain (Figure 3). This is composed of the following:

-

Oil Palm growers (Upstream production): This is centered on the roughly 0.39 million households across the country that grow oil palm, the majority of which are small-scale producers. Large producers typically invest in running their own mills for extracting crude palm oil.

-

Crude Palm Oil Mill (Midstream production): Currently there are 131 of mills that output crude palm oil in Thailand (source: Department of Internal Trade), and the Office of Industrial Economics (OIE) estimates that the country’s installed processing capacity comes to around 5.6 million tonnes of crude palm oil per year. Large operators of palm oil mills may also expand into investing in their own palm oil plantations and in developing new palm cultivars. Processing plants also produce a wide range of by-products from the milling of palm, and these may be used to generate additional income; kernel meal is used as an animal feed and the palm shells, fiber and other waste may be used for the production of biomass energy or electricity and organic fertilizer.

-

Refined Palm Oil Mill (Downstream production): The final stage of the industry supply chain is comprised of palm oil refineries, of which there are 21 in Thailand. The OIE reports that these have an annual production capacity of 2.5 million tonnes. Large operators are often connected through their investments to other parts of the palm supply chain including, for example, crude palm oil mills and the production of vegetable oils.

-

Other industries: Help absorb additional supply of palm oil and include biodiesel (B100) refineries, food processors, the chemicals industry, and oleochemicals production[5]

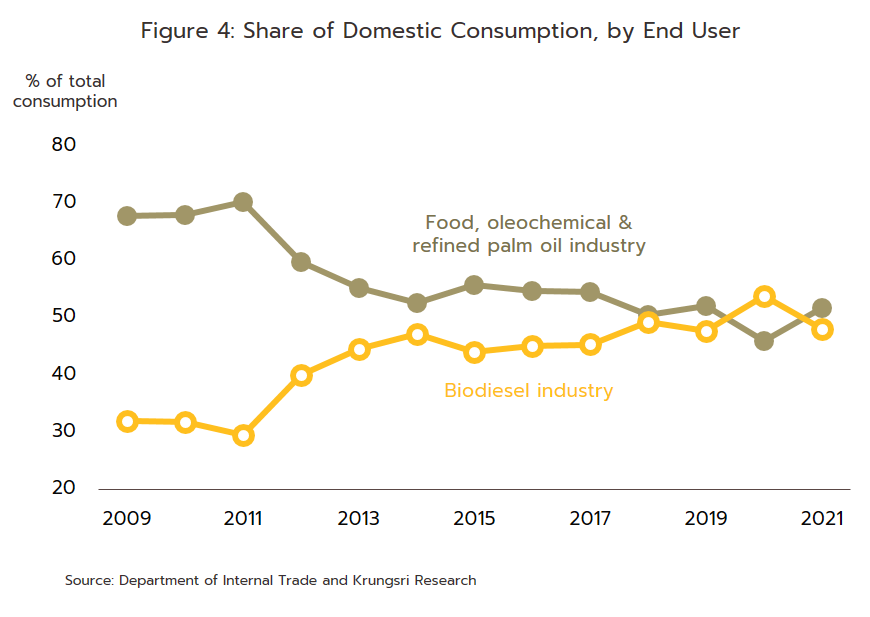

As of 2021, around 75% of Thailand’s output of crude palm oil was distributed to the domestic market (Figure 4).

-

Refined Palm Oil: 52% of crude palm oil is used in the production of refined palm oil, which is then used in the food industry to make snacks, instant noodles, condensed milk, creamer, margarine, shortening, ice cream, food supplements and vitamins, and chemical. And, oleochemical products such as soap, cosmetics, shampoo, and lubricants (Figure 3).

-

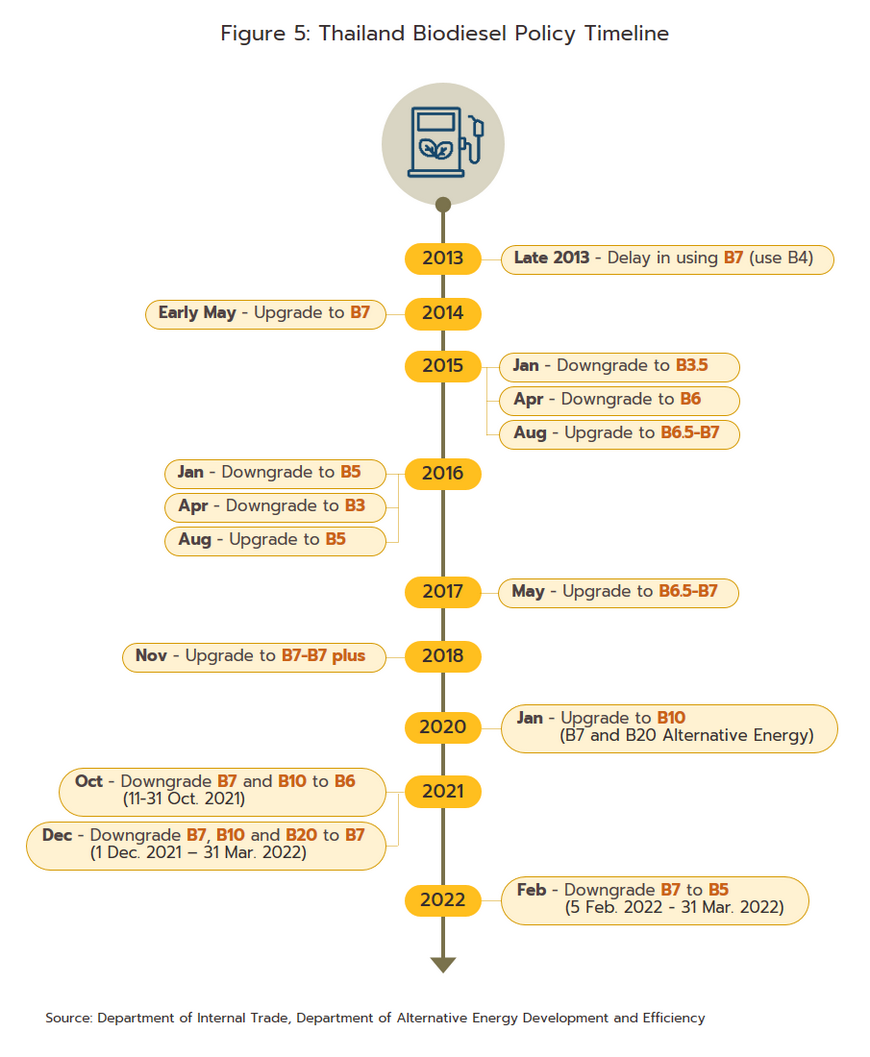

Biodiesel: The remaining 48% of the domestic output is accounted for by the production of biodiesel/B100, which is then mixed with mineral diesel for sale as a transport fuel. The authorities typically adjust the amount of B100 included in the diesel mix to match each season’s output of CPO. Thus, in 2019, the mix was raised from B7 to B10 as part of the move to soak up the CPO supply glut, but this was then cut to B7 in 2021 and then to B5 [6] in 2022 as domestic prices for CPO rose and stocks ran down (Figure 5).

Annual exports of CPO tend to be somewhat limited, though because the government periodically instigates programs to reduce supply gluts by promoting CPO exports, the exact size of the export segment depends on the extent of oversupply to the market at any particular time. Likewise, imports tend to be limited to periods when there are domestic supply shortages and when the CPO buffer stock falls below the reserve level, which is set by the authorities at 0.25-0.30 million tonnes[7].

At present, the palm oil industry falls under the oversight of the Thailand Oil Palm Board, which is tasked with maintaining stability within the industry and building competitiveness throughout the palm oil supply chain. The Board meets these goals through its planning and policy development activities, allocating the oil palm harvest between household and industrial consumers, controlling imports of oil palm and palm oil[8], and intervening to buy up the harvest when prices are low and slowing the use of goods when prices are high. However, the organization does not act alone, as it needs to coordinate with a number of other government bodies, including the Ministry of Industry (which provides support for the food and oleochemical industries[9]), the Ministry of Energy (which is responsible for the biodiesel, power generating, and bioenergy industries) and, through the Department of Internal Trade, the Ministry of Commerce, which sets prices for fresh palm and for palm oil. Details of the latter follow.

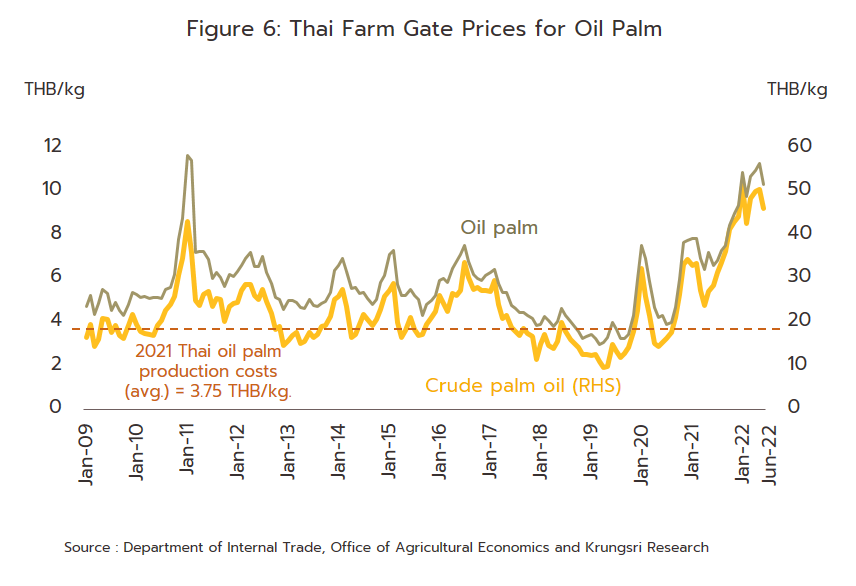

- The purchase price of oil palm from farmers is set by the Central Committee on the Prices of Goods and Services (operating under the Department of Internal Trade within the Ministry of Commerce), which specifies the reference prices for mixed grades of palm fruits according to their oil content. Since 2017, the regulations have stated that CPO mills should buy only fruits that are at least 18% oil (up from 17%), and as of June 2022, the palm purchase price was set at THB 9.22/kilogram (+62.3% YoY) (Figure 6). By setting a minimum oil content, it is hoped that the quality of Thai palm oil will increase, since harvesting fully ripe oil palm fruits increases the yield of oil and so helps farmers sell their oil palm fruits at a higher price.

-

The price for crude palm oil (CPO) is set with reference to the cost of inputs (i.e., the domestic cost of fresh oil palm) and trends in the price of crude palm oil on world markets. As of June 2022, the CPO purchase price has been set at THB 51.6/kilogram (+56.3% YoY). This takes into account the drop in the supply of fresh palm and CPO to world markets (Figure 7).

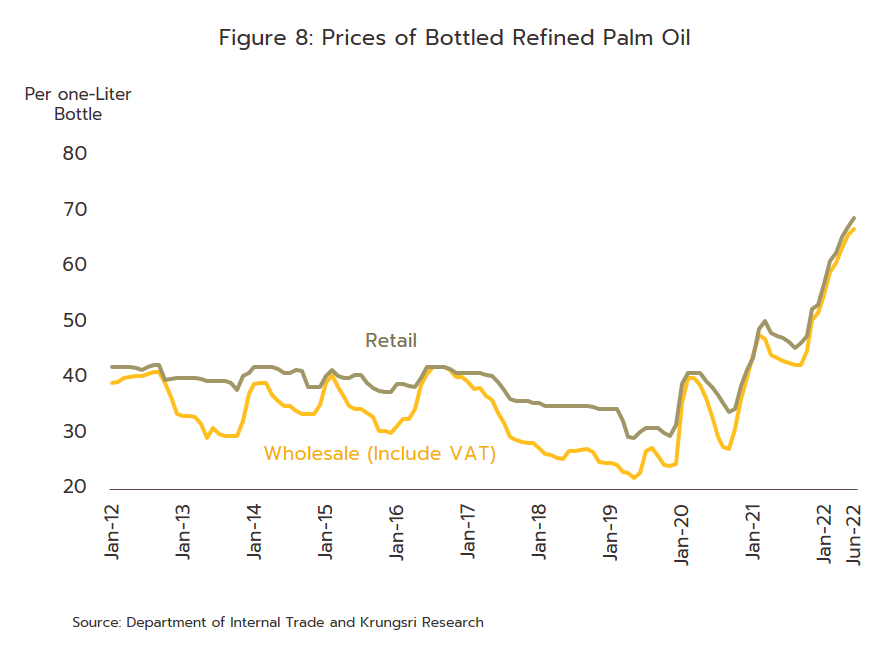

- The retail price of bottled refined palm oil is determined by the Department of Internal Trade, which allows the price to move with the cost of inputs. As of June 2022, the retail price for bottled refined palm oil stood at THB 69.0 per bottle[10] (+46.0% YoY) (Figure 8).

SITUATION

Through 2021, Thai palm oil producers benefited from a drop in output from competitor nations and a rundown in world stocks that then helped to lift prices globally.

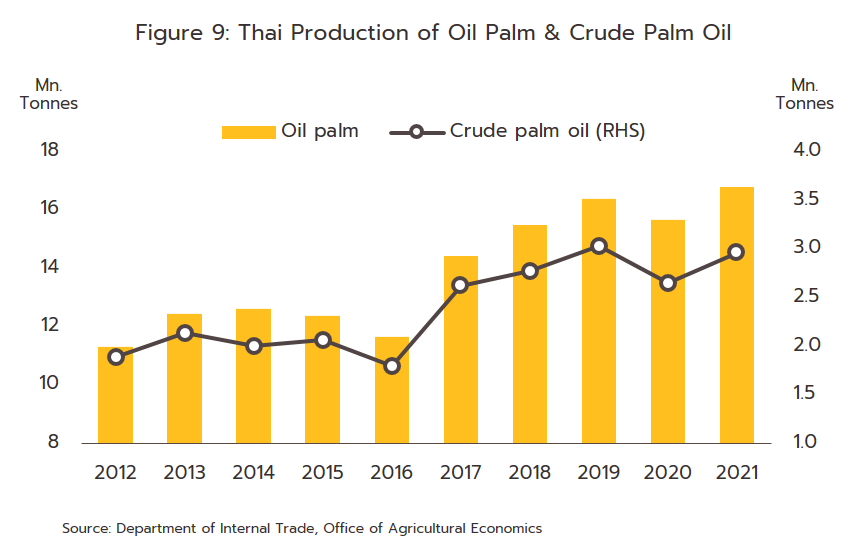

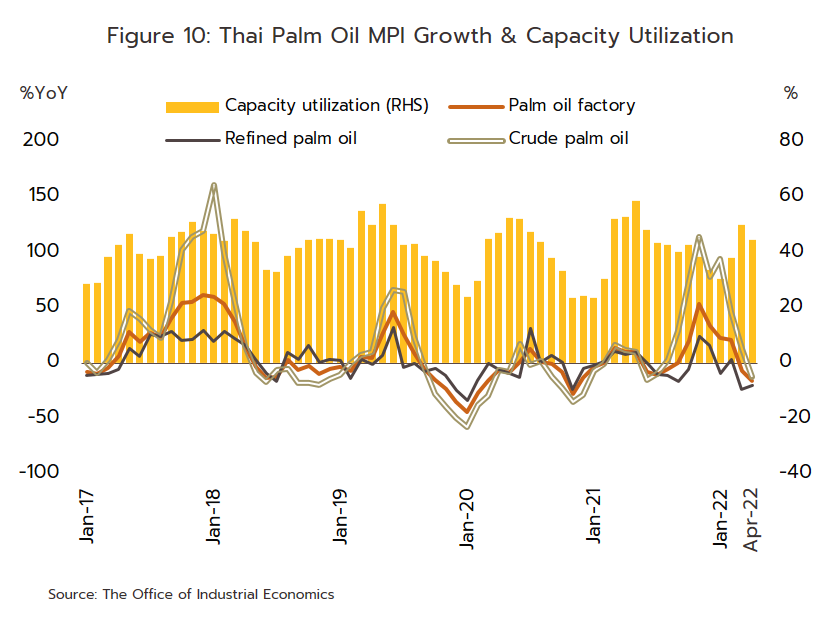

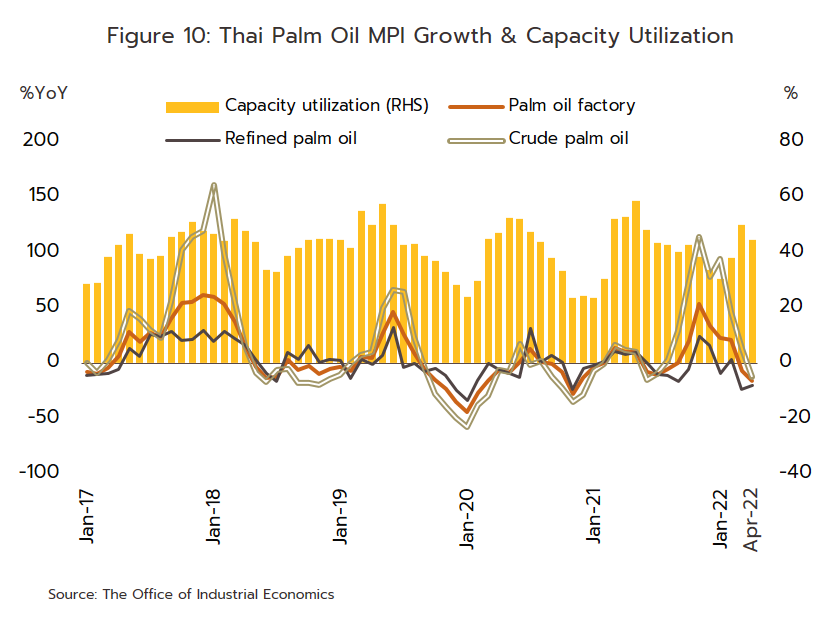

- Outputs of fresh palm and output of CPO hit historic highs in 2021 (Figure 9). The Office of Agricultural Economics estimates that in 2021, Thailand’s total harvested area of palm came to 6.08 million rai (+3.5%), which then generated a record-breaking output of 16.8 million tonnes of fresh palm, up 7.3% from 2020’s total of 15.7 million tonnes. Outputs per rai also increased 3.6% to 2.76 tonnes/rai, helped by: (i) better climatic conditions and heavier rainfall; and (ii) a surge in the global cost of palm oil that helped to lift domestic prices 47.4% to THB 6.7/kilogram. This incentivized growers to better look after their orchards and to harvest fruits only as per the official requirements, which increased the quantity of oil that could be extracted from the fruits. Production of CPO in 2021 reached 2.96 million tonnes or increased 11.8% from 2020’s total of 2.65 million tonnes. This was in line with the 7.1% rise in the CPO mill manufacturing production index (Figure 10).

- Although domestic distribution softened with a decline in demand from the transport sector, this was offset by growth in export markets (Table 2).

Domestic demand for CPO slipped -5.8% to 2.38 million tonnes in 2021 on the effects of the lockdown and much greater working-from-home policy, which then reduced sales of biodiesel. However, the market was buoyed by stronger demand for refined palm oil. Details of the market are given below.

-

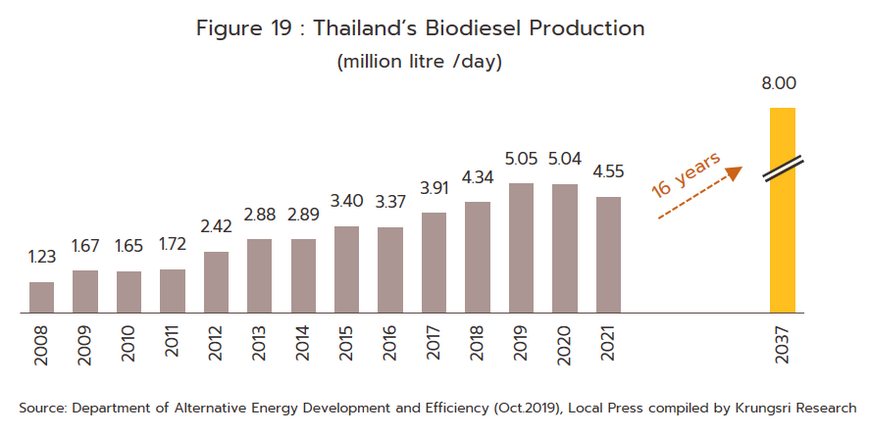

The biodiesel industry: Demand for CPO from biodiesel producers dropped -15.9% to 1.15 million tonnes in 2021. This fall was mirrored in the overall slide in purchases and production of biodiesel (for mixing with mineral diesel), which slipped by respectively -10.3% and -9.7% to averages of 4.59 and 4.55 million liters per day (Figure 11). These falls were driven by the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 12), during which movement was restricted causing many employees stayed at home to work, and this then eroded demand for transport fuels. Given this slump in sales, average capacity utilization for all 14 of Thailand’s biodiesel producers (Table 3) was cut from 60.9% in 2020 to 50.4% in 2021.

-

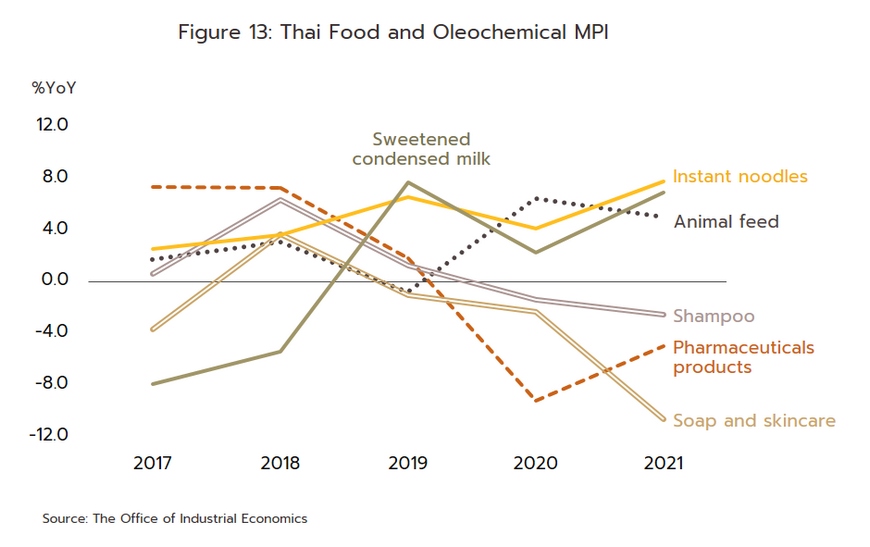

Producers of refined palm oil: In 2021, demand for CPO to be turned into refined palm oil and for use in the oleochemicals industry (for both domestic and industrial applications) increased 6.0% to 1.24 million tonnes. Growth was driven principally by greater consumption in the food processing industry (for example, in the manufacture of instant noodles, condensed milk, and ice cream), an effect that arose from the COVID-19 pandemic and the desire among consumers to buy goods that could be stored safely at home. Following this in importance was demand from manufacturers of pet food selling into both domestic and export markets. However, consumption of oleochemical products (e.g., detergent, soap, medicines, and cosmetics) tended to soften in line with the greater care shown by consumers over their spending, especially on goods such as cosmetics. Overall, the outlook for the food and oleochemical industries moved in line with changes in these industries’ manufacturing production indices (Figure 13).

2021 exports of palm oil products surged 165.2% to a total of 0.79 million tonnes, generating receipts of USD 941.6 million (+346.4%). Exports received a major boost from the drop in output in competitor nations and government moves to reduce the domestic supply glut by encouraging greater overseas sales. Details for individual segments are given below.

-

Crude palm oil: Exports of CPO surged 223.9% to 0.72 million tonnes in 2021, which then brought in income of USD 847.8 million (+484.9%). Exports were boosted by additional sales to: (i) Malaysia, where sales increased to 0.16 million tonnes (+265.7%) due to COVID-19-induced labor shortages that made it difficult to bring in the harvest, and the resulting rundown in stocks had to be replaced by Thai imports; and (ii) India, where sales jumped 215.4% to 0.52 million tonnes as importers looked to replace lost imports from Indonesia and Malaysia with those from Thailand. Sales to India were also helped by the cut in import duties on vegetable oils (i.e., palm, soy, and sunflower oils) as the government tried to reduce food processors’ overheads and protect the public from the impacts of a sharp rise in global prices for vegetable oils (Figure 14).

-

Refined palm oil: Exports edged down -5.1% to 60,767 tonnes on an almost complete halt to purchases by Malaysia (in 2020, sales to Malaysia totaled 21,700 tonnes). Instead, Malaysia switched to sourcing CPO (an input into a number of downstream processes) from Thailand and refined palm oil from Indonesia. Fortunately, this was offset by gains elsewhere and the overall decline was somewhat mild. Thus, following the Indian government’s cut in import duties[11], sales into India came to 17,007 tonnes, while exports to other important markets also improved, including those to Myanmar (+3.3%), China (+6.1%)[12] and Lao PDR (+21.6%). The total value of refined palm oil exports for 2021 was USD 82.2 million, up 43.5% on a 51.2% increase in export prices, the latter being attributable to the higher cost of palm fruits and of CPO.

Other palm oil products: Exports of other palm oil goods declined -17.5% to 9,592 tonnes as depressed purchasing power translated into sharp drops in sales to Malaysia (-26.3%), Lao (-60.6%), Cambodia (-28.9%), and Malawi (-30.2%). One bright spot was sales to China, which were up 118.7%. In the year, the Chinese government placed controls on energy use by industrial consumers that affected the domestic supply of vegetable oils, and imports from Thailand were used to plug this gap[12]. Because export prices were driven up by higher costs, the total value of exports jumped 32.9% to USD 11.6 million.

- This surge in exports meant that at the end of 2021, CPO stocks came to only 0.17 million tonnes, down -17.5% from 2020 and below the target level for buffer stocks of 0.25-0.30 million tonnes.

- Prices for oil palm and palm oil have been on a steady upward track thanks to restricted global supply (most obviously from falling output in Indonesia and Malaysia) and the decline in Thailand’s stocks of CPO, which have slipped beneath the buffer stock target. These factors have then combined to push prices to historic highs, with palm fruits at THB 8.9/kilogram (as of December 2021) and averaging THB 6.7/kilogram across the year (+47.4%), and CPO at THB 46.8/kilogram in December and THB 38.0/kilogram (+35.2%) for the year as a whole. Export prices for palm oil products were also up 68.3%, and as a result the government, (specifically the Committee on Energy Policy) agreed that to reduce demand and to prevent too sharp an increase in prices, it would cut the diesel mix from B7 to B5 with effect from 5 February to 31 March, 2022. In addition, the Thailand Oil Palm Board also agreed to the implementation of measures that aim to stabilize the market, including the income guarantee scheme for palm growers (2021-2022), export promotion policies, and schemes that will help add value to oil palm and palm oil products.

Through 5M22, the palm oil industry continued to enjoy solid rates of growth on tight global supply that then boosted Thailand’s penetration of export markets.

- The supply of palm fruit used for processing into palm oil slightly fell by -1.1% YoY to 7.2 million tonnes. However, with the extraction rate that expanded 2.5% YoY due to the more appropriate harvest period of fully ripe oil palm fruits, this then allowed for output of CPO to rise to 1.3 million tonnes (+1.0% YoY).

- The total quantity of CPO distributed to the market expanded by 5.3% YoY in the period to reach 1.3 million tonnes, mostly thanks to the strength of exports.

-

Exports jumped 131.6% YoY to a total of 0.4 million tonnes on the impacts of COVID-19 and the war between Russia and Ukraine, which raised fears over food security and encouraged an increase in imports of CPO into Malaysia and India, which are Thailand’s main markets. Sales were further boosted by the cut in Indian import duties on CPO to just 5% in February 2022 (sales to India surged 169.8% YoY).

- Domestic distribution of CPO slumped to just 0.86 million tonnes (-15.9% YoY) in the period, with declines seen for both use in the production of refined palm oil and for conversion into biodiesel. Demand from producers of refined palm oil slipped -11.4% to 0.46 million tonnes on high prices that have eroded demand from downstream consumers, some of whom have switched to other similarly priced vegetable oils (e.g., soy and rice bran). Demand from biodiesel producers fared even worse, dropping -20.5% YoY to 0.4 million tonnes. Sales were hit by the switch to B5 for the diesel mix from February 2022 and by the impact of the Ukraine war on diesel prices, and these have now reduced demand for biodiesel by -23.1% YoY to a daily average of 3.82 million liters. These declines are in line with the falloff in demand for CPO and consumption of biodiesel, which has dropped by between -23% and -27% YoY per month since February 2022.

- As of the end of May 2022, stocks had fallen -33.4% YoY to 0.17 million tonnes, lower than the target buffer stock level. This then added pressure to the prices for palm fruit and palm oil to rise, and thus, as of the end of June 2022, palm fruit sold at THB 9.22/kilogram (+62.3 YoY), while the price for CPO was THB 51.6/kilogram (+56.3% YoY).

OUTLOOK

The Thai oil palm and palm oil industry is seeing steady growth through 2022. Details are as follows.

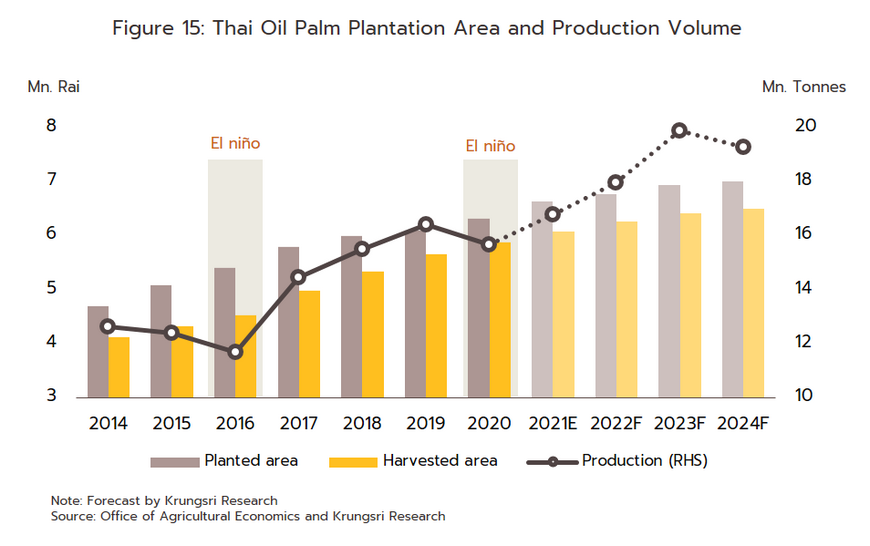

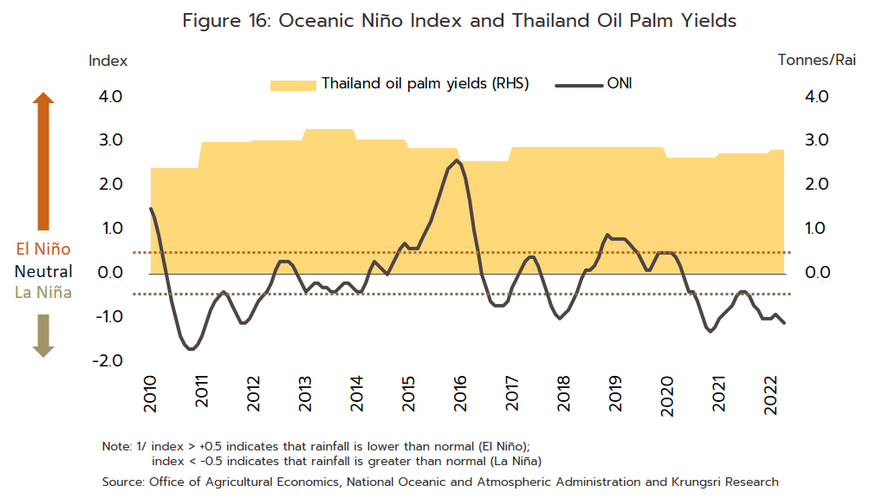

- The supply of palm fruit and CPO is forecast to expand by around 6%-7% this year. (i) Government policy aims to extend the total area under cultivation to 10 million rai by 2029 for use as an alternative source of energy, and this has led to an average annual increase of some 0.1-0.2 million rai. This is mostly concentrated in the northeast of Thailand, and because a rising proportion of this is now greater than 8 years old, yields are increasing[13] (Figure 15). (ii) Farmers are being incentivized to increase plantation sizes by high prices and the government income guarantee scheme. (iii) An improvement in climate and rainfall is supporting an uptick in yields[14], particularly with regard to likely heavier rainfall in the south of the country that is linked to the emergence of La Niña conditions and that will affect the weather over the next 1-2 years (Figure 16). As per-rai yields rise, annual output of CPO is expected to climb to 3.1-3.2 million tonnes.

-

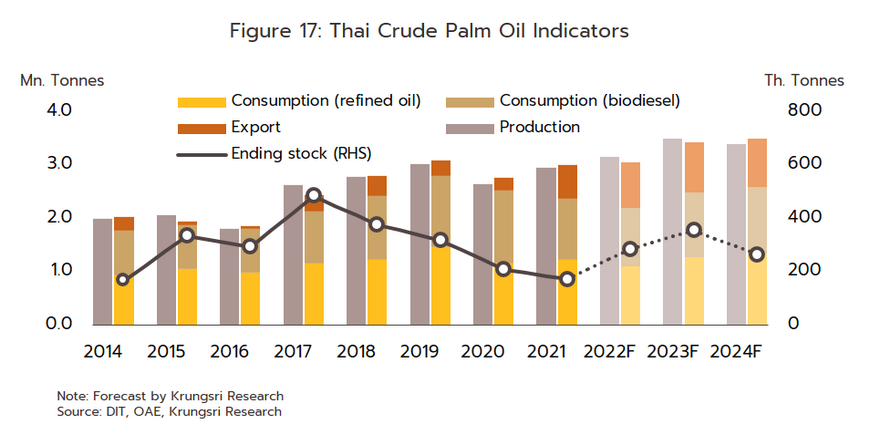

Distribution of CPO will strengthen on a 30-40% surge in exports that will be driven by: (i) the effects on fears over food security of COVID-19 and the unexpectedly extended war in Ukraine; (ii) increased efforts by importing nations to build stocks as they try to limit the extent of domestic price rises for vegetable oils; and (iii) the hunt for alternative sources of CPO following the decision by Indonesia (the world’s principal source of CPO) to halt exports between 28 April-23 May 2022. Consumption by downstream industries will slip by -7% to -8%. Consumption of refined palm oil will slip by between -10% and -12% on higher prices for inputs that will erode demand for downstream goods. Likewise, the switch to B5 and higher diesel prices (and thus lower sales) will mean that demand from the biodiesel industry will shrink by -4% to -6%.

-

Year-end stocks of CPO are forecast to reach 280,000-290,000 tonnes due to supply growth that will outpace that of demand. Given this, domestic prices for oil palm and palm oil will weaken, but overseas demand should keep them in the range of THB 9-11/kilogram.

Over 2023 and 2024, the supply of oil palm will increase on an expansion in the area under cultivation and the maturing of previously established plantations. High prices will also incentivize growers to maximize their outputs, and so the supply of fresh palm fruits is expected to increase by 3-4% annually, which will then bring Thailand’s yearly output of CPO to an average of around 3.4-3.5 million tonnes (Figure 17). Alongside this, the global supply of palm fruit and of palm oil will strengthen, and with the easing of the COVID-19 pandemic, production in Indonesia and Malaysia will return to more normal conditions (Figure 18). This greater supply of CPO will thus tend to suppress domestic prices, but demand will remain high and the drawn-out war in Ukraine will place a floor under global crude oil prices, meaning that the space within which domestic of palm fruit and palm oil prices may fall will be limited.

Domestic demand for CPO should expand by 8.0-9.0% per year over 2023 and 2024 as economic recovery translates into growth in downstream industries, though the food, oleochemical and transport industries will be particularly important.

- Demand for CPO for use in the production of refined palm oil is forecast to increase by 10.0-11.0%. This improvement will be driven by recovery in the tourism, hotel, and restaurant industries, which will then feed into greater demand for goods from food processors. In addition, consumption of palm oil/palm fats (obtained from the palm oil purification process) by players in the oleochemical industry will strengthen on greater demand for products such as detergent, soap, medicines, and cosmetics. Moreover, as laid out in the 2018-2037 plan for the reform of the Thai oil palm and palm oil industry, officials have put in place measures to promote the production of 8 target oleochemical product groups. It is hoped that this will both add to demand for CPO and help to develop the domestic oleochemical industry.

- Demand for biodiesel should continue to rise by an average of 6.0%-7.0% annually to around 5.3-5.5 million liters/day.

-

Use of diesel-powered vehicles in the transport sector will increase on: (i) a recovery in economic activity; (ii) an expansion in e-commerce, which will then support greater use of commercial vehicles, especially of pickups; (iii) greater economic integration within the ASEAN zone that will also tend to increase demand for commercial vehicles; and (iv) an expected 3.0-4.0% annual rise in the number of diesel vehicles on Thai roads.

-

Major auto manufacturers are developing new engines that are capable of running on diesel that contains a greater proportion of biodiesel, and these will be fitted to pickups, SUVs, trucks, and large vehicles.

Growth in exports is likely to return to more normal levels of around 2.5-3.5% per year. Demand will continue to come from the main export markets of India and Malaysia, while the Thai government will also keep measures in place to promote exports of CPO as a way of absorbing excess domestic production.

Potential risks and headwinds that may challenge the industry will include the following.

-

Energy prices that are being pushed up by the war in Ukraine may undercut demand for diesel from the transport sector.

-

Competition remains stiff, this coming from alternative products, new entrants to the market, and existing players that have added to their production capacity. Indeed, over the 3 years from 2019-2021, capacity utilization in the palm oil industry averaged just 41.1%, which is very low when compared to similarly priced alternative oils such as soy (95.0% capacity utilization) and rice bran (61.6% utilization).

-

Across the industry, production costs are higher in Thailand than in competitor nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia. This difference is due to the low capacity utilization of Thai CPO mills, which raises their marginal costs and makes Thai products uncompetitive on global markets.

-

Non-tariff barriers stand in the way of exports. These are particularly important in the context of EU environmental protection measures (the EU is one of the world’s largest markets for palm oil) since these specify that EU member states will steadily reduce consumption of biofuels made from potentially high-carbon palm oil. Europe has thus set the goal of EU industries becoming ‘zero palm oil’ by 2030[15]. In addition, there is also growing interest in Europe becoming ‘palm oil free’ given the fact that palm oil is a saturated fat and it contains a much higher proportion of carcinogenic adulterants than do other vegetable oils.

-

Government promotion of electric vehicles (EVs) will affect demand. The government hopes that by 2030, at least 30% of auto production will be for ZEVs (zero emission vehicles), which would then likely weaken demand for biofuels.

Government measures/programs targeting the palm oil and oil palm industry, 2021-2022

1) Income support program for oil palm growers - The cabinet authorized payments to be made to palm growers for the difference between the guaranteed price for oil palm and its reference price for households operating plantations up to 25 rai in size that were at least 3 years old and already producing fruit (when market prices were beneath the set price). The guaranteed price was set at THB 4/kilogram for 18% palm oil, and the program is running from September 2021 to August 2022. The program has been approved in principle by the Thailand Oil Palm Board, and it is now awaiting cabinet approval of its THB 7.66 billion budget.

2) Additional measures to return the domestic palm oil market to equilibrium

2.1) The government cut the biodiesel component of B7, B10 and B20 all to 7% (from December 2021 to March 2022), and to help offset the rising cost of diesel and to reduce the impact of the cost-of-living crisis, from 5 February 2022, the standard diesel mix was also reduced from B7 to B5.

2.2) The government put in place a CPO export promotion scheme to help dissipate the domestic supply glut. This provided THB 2/kilogram subsidies to cover administrative costs when domestic stocks rose above the target level of 300,000 tonnes and domestic prices were higher than those on global markets. The relevant subcommittee approved the following for the 2021-2022 period.

-

The ending of the export scheme was delayed from September to December 2021. THB 618 million was allocated to cover the project from December 2021 to March 2022.

-

An export promotion scheme was approved in principle for 2022 that aims to achieve exports of 150,000 tonnes by September.

3) The government plans to add value to the oil palm and palm oil industry by targeting 8 product groups, namely: (i) base oil; (ii) bio-transformer oil; (iii) environmentally friendly detergents (these are based on methyl ester sulfonate); (iv) bio-lubricants and bio-greases; (v) paraffin; (vi) pesticides and insecticides; (vii) bio-hydrogenated diesel (BHD)[16]; and (viii) bio-jet fuels[17]. Plans and progress on these is described below.

3.1 Manufacturing processes, technology, and innovation: The government has encouraged Thai companies to register innovations, and to register and certify environmentally friendly goods and services. At present, the National Science and Technology Development Agency is working with the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, the Provincial Electricity Authority, the Metropolitan Electricity Authority, and the private sector to test and analyze bio-transformer oil and to compare this against an imported alternative.

3.2) Standards and testing: The government has encouraged the establishment of standards to cover industrial production, usage, and other areas, and the improvement of laboratories and safety testing facilities for the checking of goods produced by the oleochemical industry. The Thai Industrial Standards Institute has established a technical subcommittee that has been tasked with drawing up standards for the production and use of bio-transformer oils.

3.3) Benefits and incentives: The types of business activities qualifying for investment support have been expanded to include the oleochemical industry so that these businesses can claim benefits in the same way that producers of environmentally friendly polymers and chemicals can. A green tax expense write-off has also been put in place to promote the use of bioproducts by corporations. The Board of Investment is now preparing a list of 6 product groups, production of which will make businesses eligible for investment support.

3.4) Demand: Measures have been implemented to promote the use of environmentally friendly products that have been awarded the highest ‘green label’ or ‘green basket’ award or at least a level 4 ‘green industry’ award. Currently, the Marine Department, the Bangkok Mass Transit Authority, and the State Railway of Thailand have agreed to use products that meet these requirements. The Ministry of Finance has also issued ministerial regulations that cover the procurement of environmentally friendly supplies.

3.5) Other measures: These include promoting manufacturing and supporting the oleochemical industry by amending town planning and ministerial regulations, and offering incentives for businesses investing in oleochemical businesses in the EEC (these stipulate that factories must be sited on industrial estates). The authorities are also considering additional measures to promote investment in areas designated for the promotion of the bio-economy.

4) Managing stocks of CPO: The cabinet has approved the allocation of THB 372.5 million for the development and installation of a system for checking and managing stocks of CPO held in operators’ stores. This will be run by the Department of Internal Trade.

5) Management and control of imports and goods in transit: Imports of palm oil are managed via: (i) customs checkpoints (for normal imports) at Map Ta Phut, Bangkok, and Laem Chabang; and (ii) checks at Bangkok for goods bound for Thailand and at Chanthaburi (for goods in transit to Cambodia), Nong Khai (for goods going on to Lao PDR) and Mae Sod (for goods to be shipped on to Myanmar).

Plans for the Development of the Thai Oil Palm Sector

1) Alternative Energy Development Plan for 2018-2037 (AEDP2018): In 2020, the National Energy Policy Office and the cabinet agreed to a new alternative energy development plan that reduced the targets for consumption of biodiesel by bringing these into line with the Power Development Plan (PDP) for 2018-2037. This increases the proportion of energy being produced from other types of alternative and renewable sources but reduces targets for consumption of ethanol and biodiesel because of the likely increase in use of electric vehicles (tentative plans for 2037 biodiesel production are for this to be reduced from 14 million liters to 8 million liters per day).

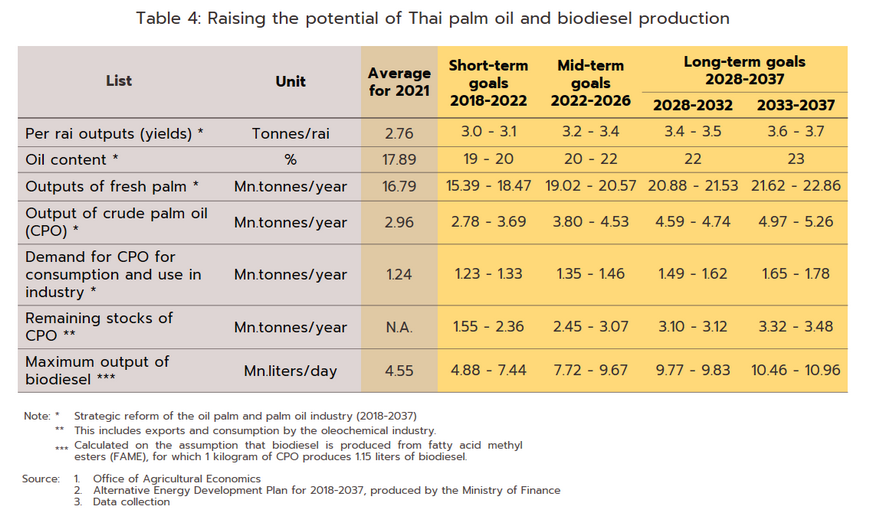

2) Plan for the systemic reform of the oil palm and palm oil industry (2018-2037): This sets targets for improving production efficiencies and for raising output of CPO for consumption by households and industry. Its main principles are as follows:

[1] Palm oil may be extracted both from the oil palm fruit and from the kernel of oil palm, although as of the 2020/2021 season, extraction of oil from palm fruit accounted for 89.7% of global palm oil production.

[2] Yields (Output per rai) for particular types of vegetable oil are: oil palm: 512 kg/rai; oil palm seeds/kernels: 73 kg/rai; rapeseed: 89 kg/rai; sunflower seed: 81 kg/rai; coconut: 54 kg/rai; soy: 52 kg/rai; and peanut: 51 kg/rai.

[3] Generally, crude palm oil mills are located close to plantations since the palm fruits need to be processed within 24 hours of harvesting to guarantee high-quality oil.

[4] Typically, harvesting can begin when oil palms are 3.5-4 years old. Yields peak when palms are 6-16 years old and then decline, although production can continue until trees are 25-28 years old. At this point, the trees are usually cut down and replaced.

[5] The oleochemicals industry includes the use of palm oil and fats for the production of consumer goods such as lubricants, laundry detergent, insecticides, etc.

[6] B5, B7 and B10 refer to mineral diesel mixed with respectively 5%, 7% and 10% biodiesel.

[7] The safety stock or buffer stock is the stock level (here of CPO) that the Public Warehouse Organization maintains in reserve in order to protect against shortages that may occur from sudden increases in consumption by downstream industrial consumers. In the event of temporary disruptions to supply, the existence of the safety stock means that producers will be able to continue manufacturing goods that use palm oil as an input. The Ministry of Commerce is responsible for setting an appropriate level for the stock buffer, and at present it has been decided that this should not exceed or below than 0.25-0.30 million tonnes.

[8] The Thailand Oil Palm Board has appointed the Public Warehouse Organization, as the sole importer of palm oil for periods when shortages are seen in the domestic market. Import duties are levied on palm oil at the rates of: (i) 20% for imports up to the quota limit of 4,860 tonnes, (ii) 143% for over-quota imports, and (iii) 0% for imports made under the ASEAN Free Trade Area Agreement.

[9] Oleochemicals are biochemicals produced from vegetable oils and animal fats. These include fatty acids, glycerin, fatty acid esters, and fatty alcohols, and these are typically used in the food processing and energy production industries.

[10] Since February 2019, the Department of Internal Trade has allowed the price of bottled refined palm oil to float freely and for the market to set its retail price. In the past, a price ceiling of THB 42/bottle had been set.

[11] The Indian Customs Department announced that for MFNs (most favored nations), duties on imports of CPO would be reduced from 10% to 2.5%, while those on imports of refined palm oil would be cut from 37.5% to 17.5%. At the same time, cess taxes placed on importers of CPO to pay for support for the agricultural sector and to assist with social security payments would be cut from 24.75% to 8.25%. These measures ran from 14 October, 2021, to 31 March, 2022, and were put in place to reduce the public’s exposure to cost-of-living price increases, to restrain a rise in the costs of edible oils, and to cut manufacturing overheads for food processors, and as a result of these moves, food price inflation was kept under control.

[12] China experienced a spate of power shortages in 2021, and in response, the authorities placed controls on the activities of industrial users, including producers of vegetable oils. As a consequence, China had to import a greater volume of palm oil and other palm products to compensate for falling output and rising demand in the domestic market.

[13] Palm trees planted in response to government incentives that ran from 2008-2012 are now 8-12 years old, and so these are now within their peak producing age range of 7-16 (source: Office of Agricultural Economics).

[14] Analysis of weather patterns by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) shows that over the last 60 years, on average strong El Niño and La Niña occur every 12-15 years. The last strong La Niña was in 2010-2011, and the last strong El Niño was in 2015-2016. In 2021, rainfall rose slightly on a weak La Niña but the effect of this on oil palm production was limited.

[15] In March 2019, the European Commission agreed to draft a ‘delegated act’ that laid out sustainable alternative energy standards. Under these rules, palm oil did not qualify as a sustainable product, but the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a joint effort by palm growers and palm oil producers to raise industry standards, has fortified its measures to promote economic, social and environmental sustainability. The RSPO hopes that this will help to ease the way to an improvement in exports of palm oil to Europe.

[16] This will allow the diesel mix to return to B10 as per the Euro 5 standards and to keep any drop in consumption of CPO to no more than 0.635 million tonnes per year.

[17] Bio-jet fuels are being developed in response to the imposition of a carbon tax on planes burning non-biofuels in EU airspace. Under the REDII directive, the European Commission announced its target of meeting commitments made in the Paris agreement to reduce CO2 emissions by 40% before 2030. This is to be achieved by replacing these with alternative energy by the same date, and then to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

.webp.aspx)