EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The overall trend for the cassava industry from 2025 to 2027 indicates that production is expected to remain stagnant or experience low growth. This is primarily due to fluctuating climatic conditions resulting between El Niño and La Niña phenomena. There is a particular concern that drought conditions may re-emerge and potentially cause significant damage to the 2027 harvest. Conversely, domestic demand for cassava products is projected to slowly expand, driven by downstream industries, particularly the food and ethanol sectors. This growth is anticipated as the economy and transportation sector gradually recover to support tourism and infrastructure investment. Meanwhile, the volume of exports in 2025-2026 is expected to increase, primarily due to growing demand for cassava chips from China to compensate for dwindling corn stocks, which are being utilized in its domestic downstream industries such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, food, paper, and sweeteners. However, the United States' tariff policies may somewhat limit the overall growth of the export market. In addition, in 2027, export volumes are anticipated to contract, primarily due to a shortage of raw materials resulting from the expected return of the El Niño phenomenon. Additionally, the availability of raw materials from neighboring countries is expected to decline due to the closure of the Thai-Cambodian border and increased domestic demand from recovering Thai processing plants.

Krungsri Research view

Overall, the industry can look forward to improving conditions through the next three years. Players active across the cassava supply chain can expect to benefit from stronger demand from downstream industrial consumers in both domestic and overseas markets. Less positively, the cassava industry remains vulnerable to risks arising from its significant dependency on orders from Chinese buyers.

-

Producers of native starch: Revenue is expected to increase, driven by demand from the food and drinks industry and from ethanol producers that will rise on both domestic and export markets. However, increased investment in processing plants elsewhere in the ASEAN region will mean that these positives will be undercut by stiffening competition.

-

Producers of cassava chip: Revenue is expected to increase, driven by increased demand for cassava as an alternative input into China’s food processing, animal feed, and energy industries. While this will continue to boost Thai turnover and profits, Thai exporters’ heavy reliance on the Chinese market means that they are highly exposed to any shifts in China’s export policy or buying behavior within the market. In addition, players in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are increasingly challenging Thai exporters for market share.

-

Producers of modified starch: Revenue should rise on stronger demand from downstream Asian manufacturers and processors of food, paper, sweeteners, drinks, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and textiles. New markets are also opening up, adding further to growth opportunities. However, sales are under pressure from the supply of starches produced from other inputs that have a broader range of properties.

-

Producers of cassava pellets: Revenue should rise, driven by stronger demand from China for use in the bioenergy and animal feed industries, although the possible return of El Niño conditions in 2027 may restrict the supply of inputs to processors, which would then reduce exports. In addition, Chinese players are expected to increasingly switch to corn as a replacement for imported cassava pellets.

-

Distributors of cassava products: Traders still have an opportunity to generate normal levels of profit, driven by the expanding demand for cassava in both domestic and export markets.

-

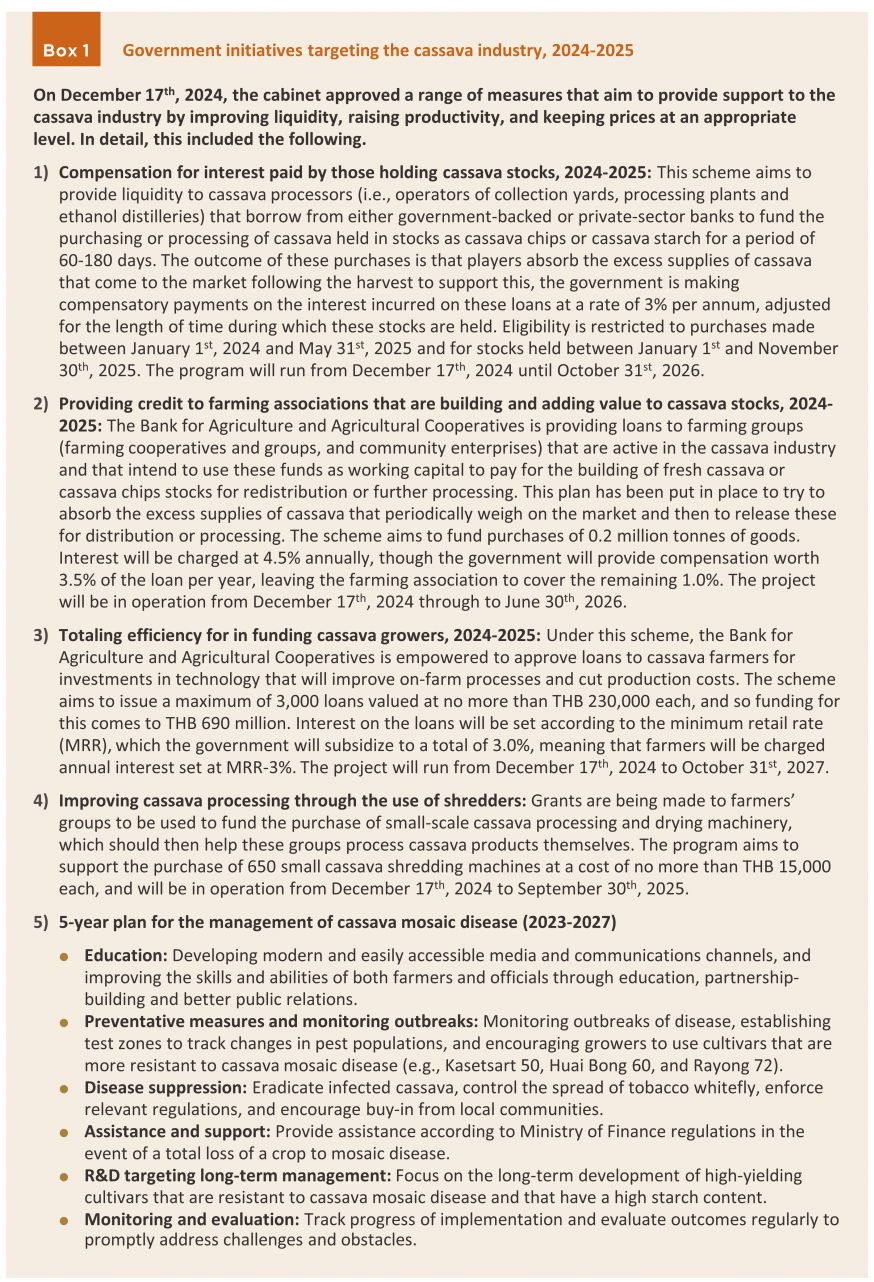

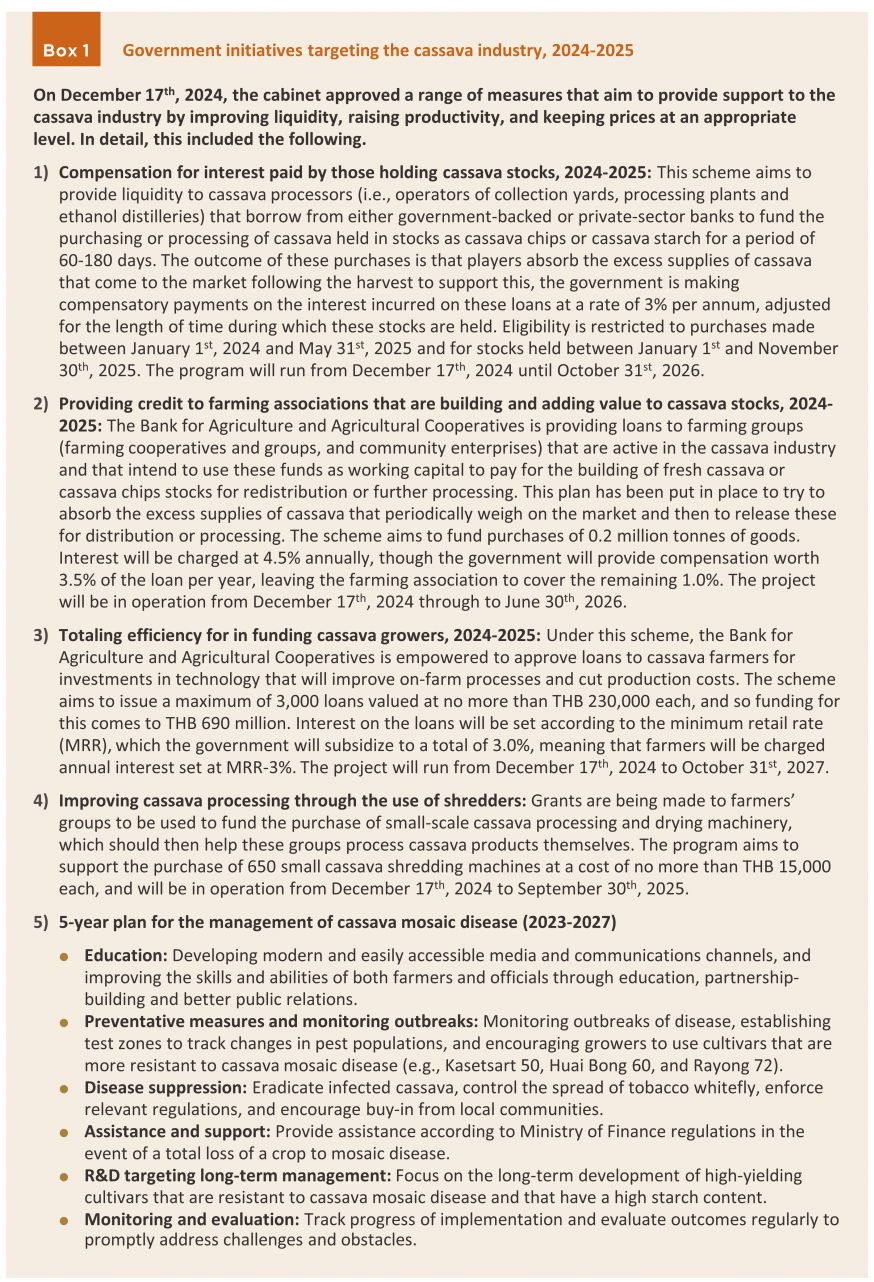

Cassava growers: Revenue is projected to remain stable or experience a slight increase, largely in line with production volumes. Farmers continue to receive support from government policies such as low-interest loans, crop efficiency enhancement programs, and measures to absorb excess produce. Despite a gradual recovery in demand for fresh cassava roots from downstream industrial sectors, several supply-side challenges persist. These include natural disasters, cassava mosaic disease, a shortage of planting material, and rising production costs (due to higher fertilizer prices and harvesting wages). Coupled with the need to clear existing stockpiles and the risk of suppressed purchase prices for fresh cassava roots from processors, these issues are expected to result in low profit margins.

Overview

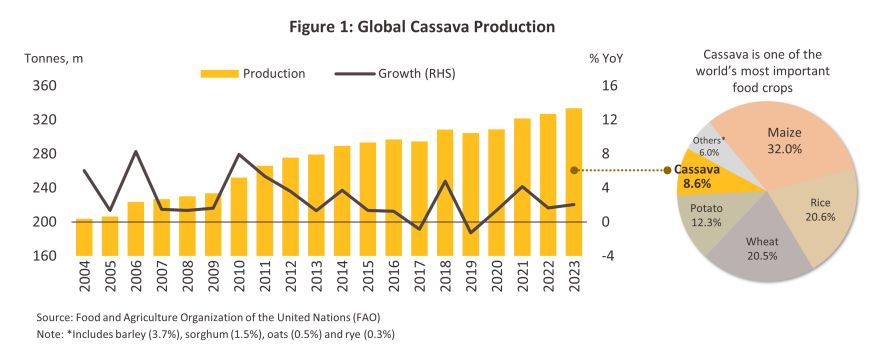

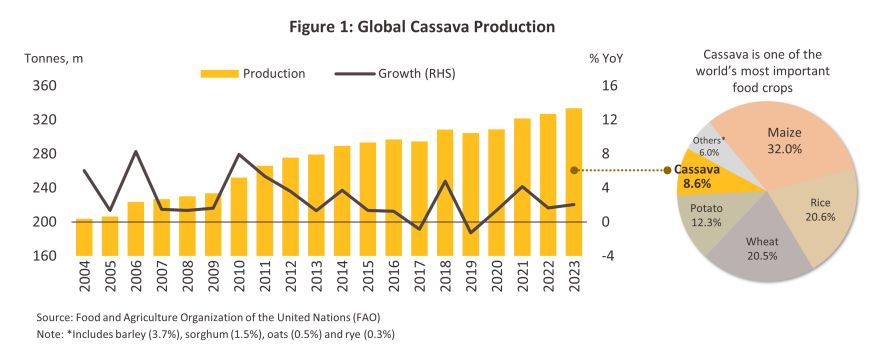

Cassava is a carbohydrate-rich crop that has a wide range of uses in the so-called ‘4Fs’ of: (i) food for human consumption, (ii) feed for animals, (iii) fuel in the form of ethanol, and (iv) factories, where cassava is used to produce, for instance, alcohol, citric acid, clothing, medicines, paper, and chemicals. The diverse characteristics of cassava have led to a continuous increase in its global market demand. This has then lifted it to the status of being the world’s 5th most important crop by output, after only corn, rice, wheat and potatoes.

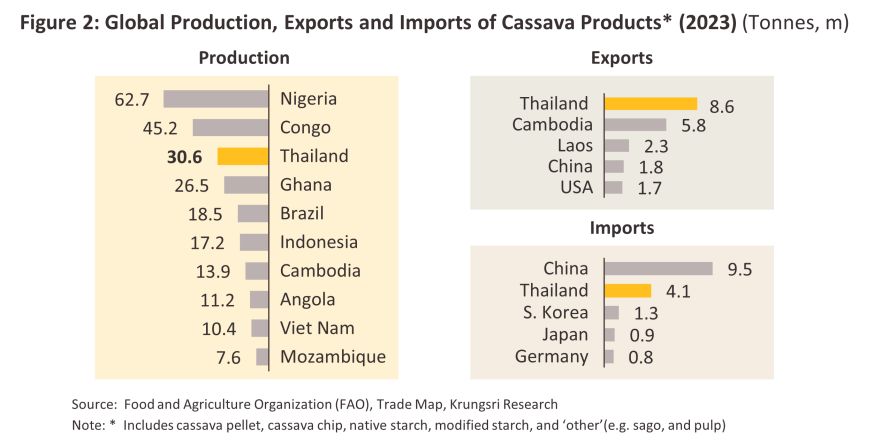

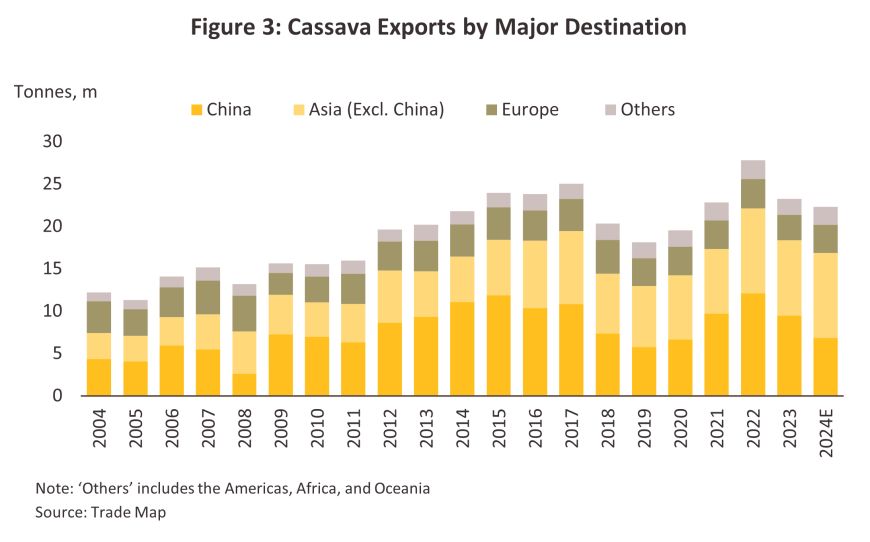

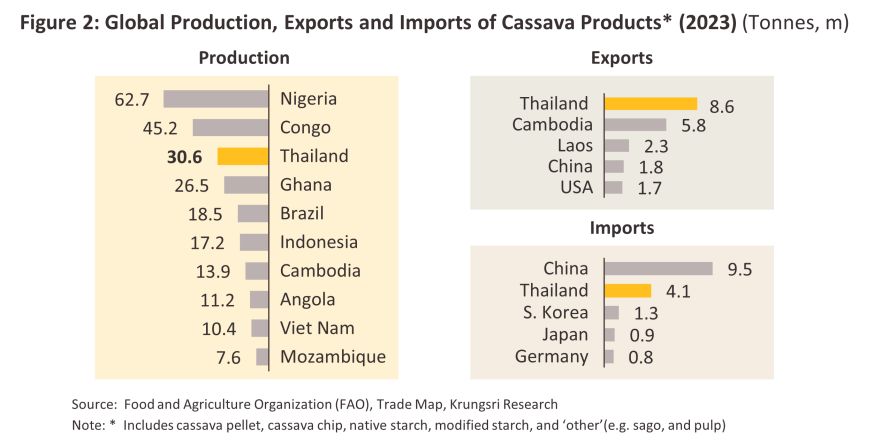

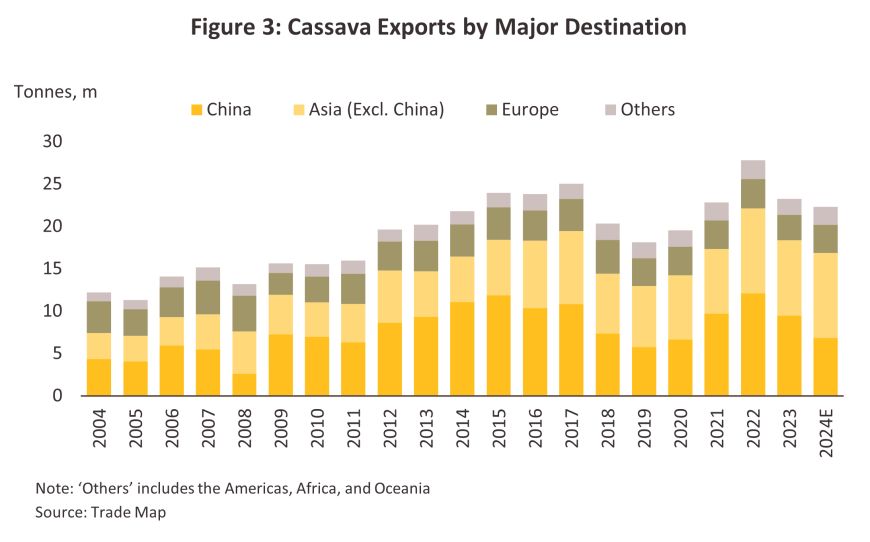

As of 2023, a total of 333.7 million tonnes of cassava were produced globally (Figure 1). Contributing 63.9% of the total, Africa was the most important cassava-producing region, followed by Asia1/ (27.8% of the total), the Americas (8.2%) and Oceania (0.1%). By individual country, Nigeria was the world’s biggest producer, with 18.8% of all outputs globally, followed by the DR Congo (13.5%), Thailand (9.2%), Ghana (8.0%) (Figure 2). Meanwhile, Cambodia2/ (4.2%), Vietnam (3.1%), and Laos (1.9%) have significantly increased their cassava production, growing at average annual rates of 9.6%, 1.3%, and 28.3% respectively over the past 15 years (2009-2023). This growth is a result of investments from Thai and Chinese entrepreneurs. Concurrently, the total global export volume of cassava products stands at 26.3 million tonnes3/, with Thailand being the world's largest exporter (Figure 2). In terms of export destinations, global markets for cassava are largely supported by demand from Asia, especially China, which alone accounts for 40.8% of all cassava imports made worldwide (Figure 3).

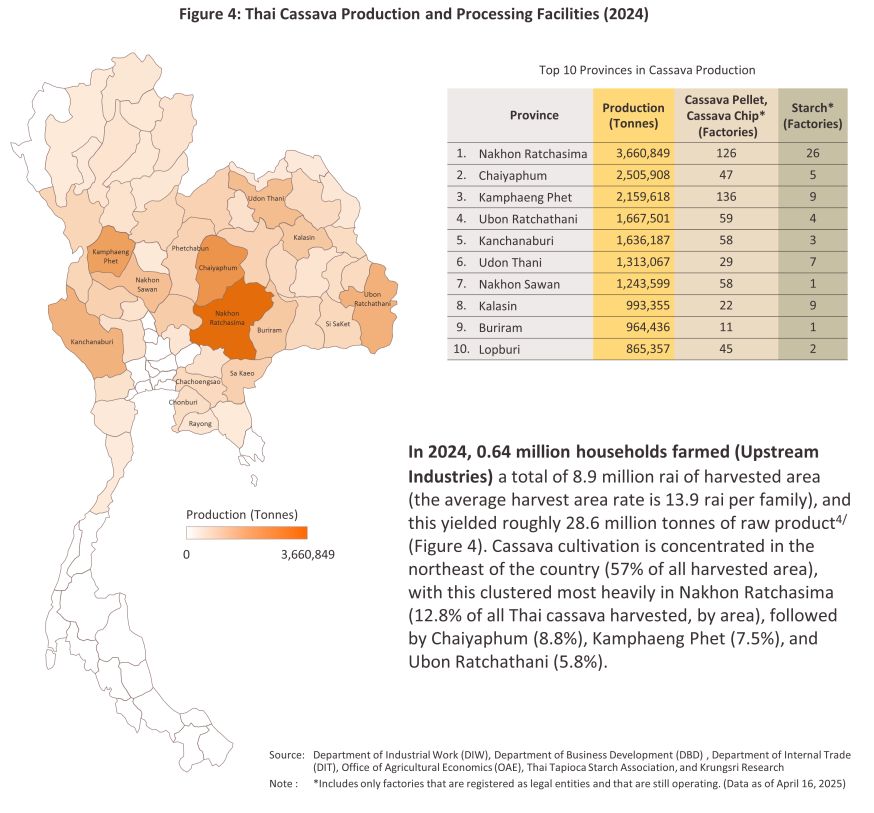

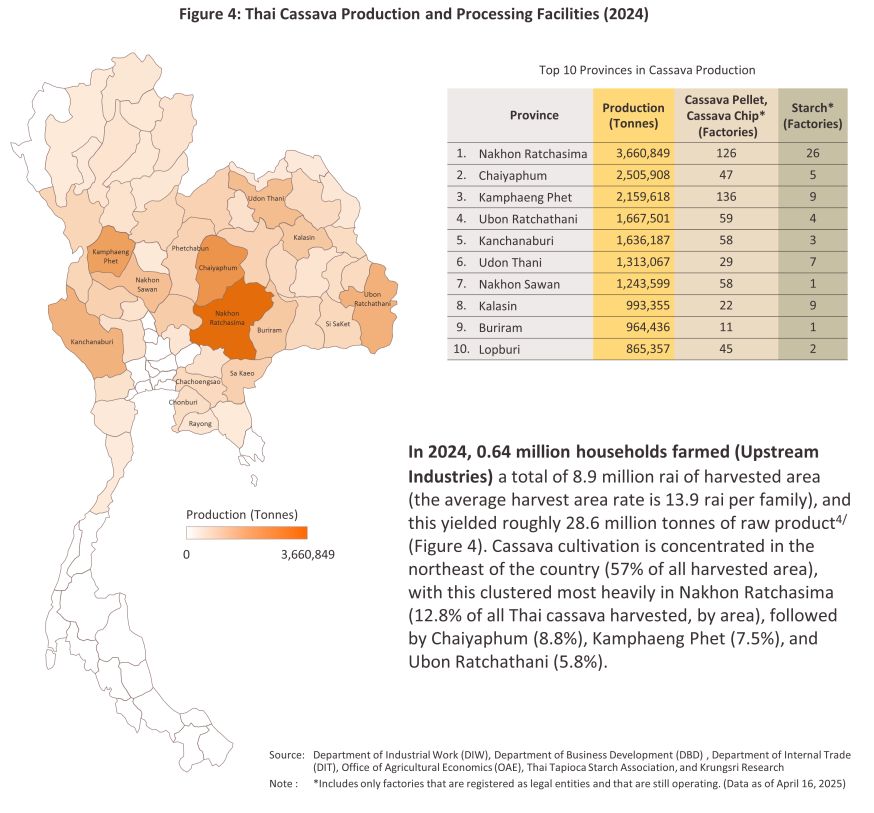

Thailand was home to 1,157 cassava processing facilities5/ (Midstream Industries), which for convenience and to save on transportation costs are generally located close to cassava producing areas, and so with 152 plants, Nakhon Ratchasima has the highest concentration of all of Thailand’s provinces. Nakhon Ratchasima is followed by Kamphaeng Phet (145 plants), Ubon Ratchathani (63 plants), Kanchanaburi (61 plants), and Nakhon Sawan (59 plants). Thai players have also sited facilities in positions that allow them easy access to imports from neighboring countries, especially Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar, though to ensure secure supplies of inputs, players have in addition established basic processing facilities in these countries. Thus, there are 63 cassava plants in Ubon Ratchathani, 61 in Kanchanaburi and 41 in Sa Kaeo, while to make exports more convenient, there are a further 20 facilities in Chonburi, 12 in Rayong and, 10 in Chachoengsao, these locations having the advantage of ready access to major ports (Figure 4).

Thai cassava products can be divided into two principal categories.

-

Dried cassava products: The most important product in this group is cassava chip, which is used as an input into the manufacture of animal feed, alcohol and citric acid. Thailand is currently home to 969 facilities that produce dried cassava chip, cassava pellet, cassava drying yard, and pulverized cassava for animal feed. Thus, there are 136 (14.0%) plants in Kamphaeng Phet, followed by 126 (13.0%) plants in Nakhon Ratchasima and 59 (6.1%) plants in Ubon Ratchathani.

-

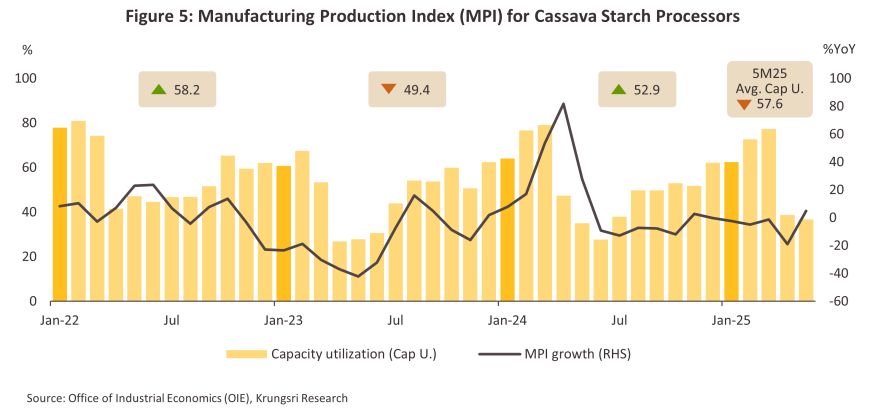

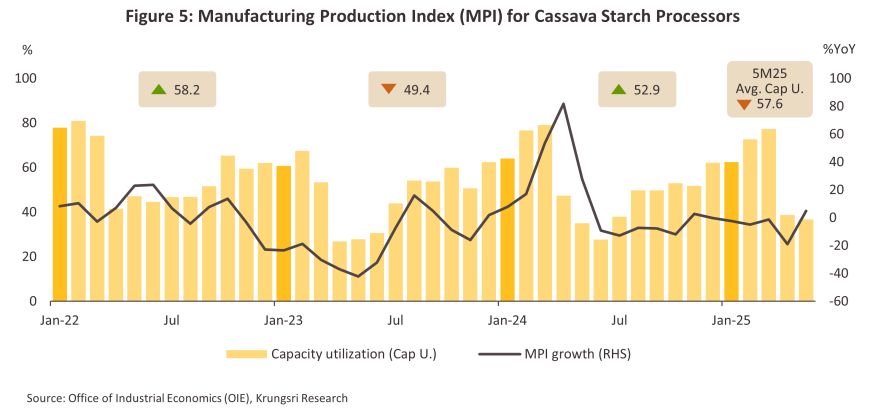

Cassava starch products: The initial output of cassava starch processing is ‘native starch’, which may be sold for household consumption as a cooking ingredient or used in the manufacture of ‘modified starch’6/, a high value-added good that is an input into a wide variety of downstream industries, including the production of monosodium glutamate, sweeteners, sauces, cosmetics and medicines. At present, there are 188 starch facilities in Thailand. Thus, there are 57 (33.7%) plants in Bangkok, followed by 26 (15.4%) plants in Nakhon Ratchasima and 9 (4.7%) plants in Kamphaeng Phet. Generally, the initial processing of cassava into starch occurs at the end of the year or the start of the next year because this period follows on immediately from the main harvest. Thus, both the cassava starch manufacturing production index and the industry’s capacity utilization typically peak between November and March (Figure 5).

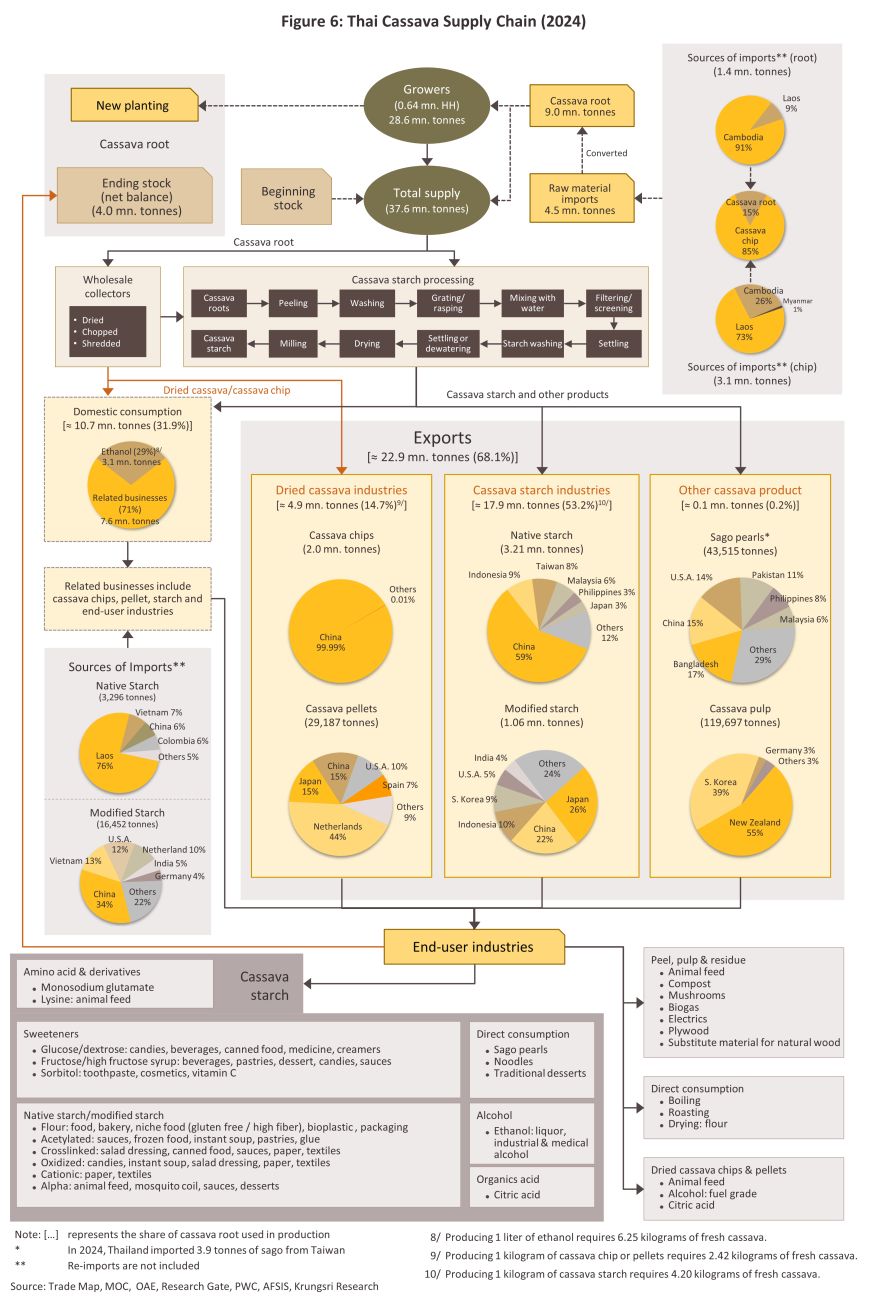

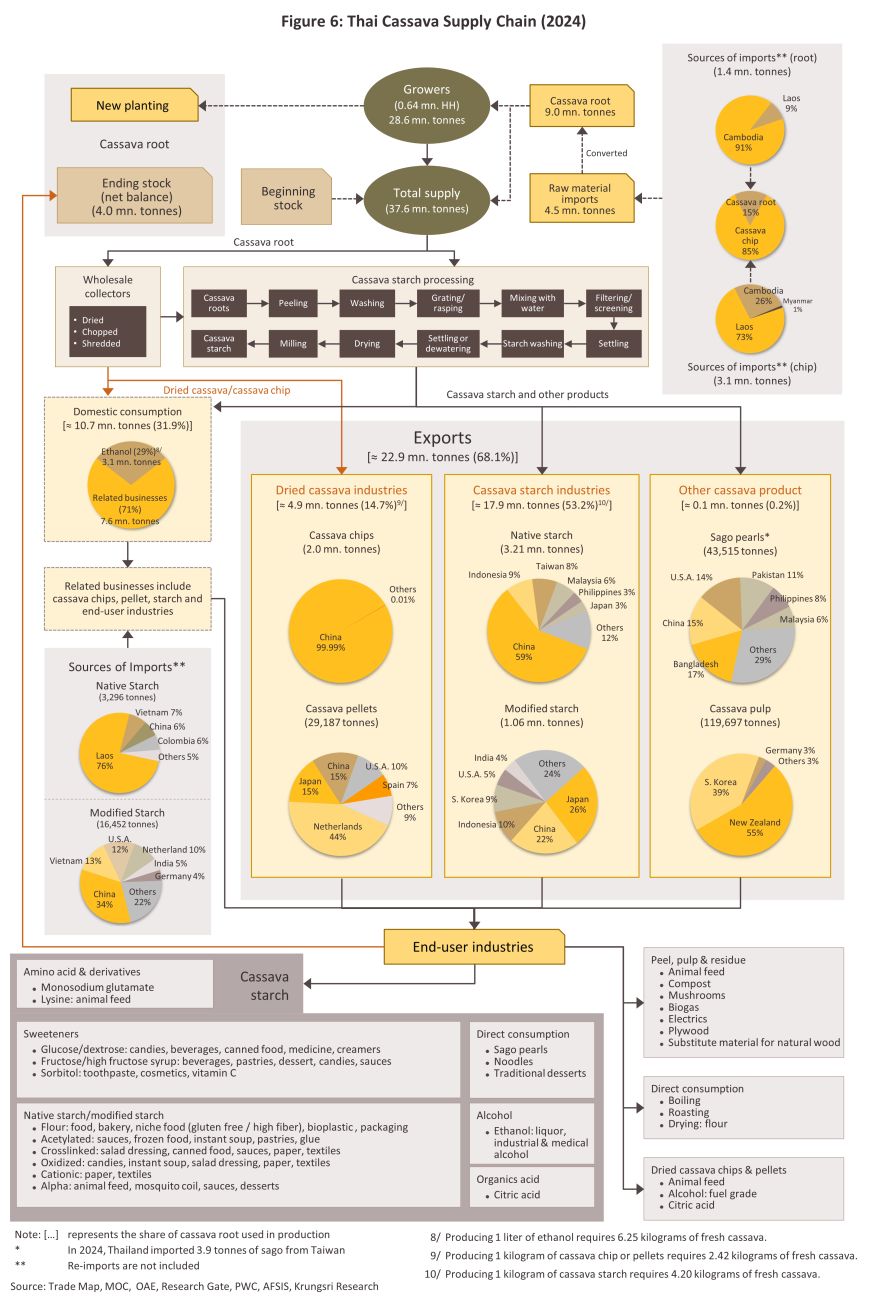

Considering the Thai cassava supply chain as a whole, in 2024, 68.8% of inputs to cassava processing was sourced domestically and only 21.5% came from imports, 99.4% of which was sourced in neighboring countries. These supplied 3.1 million tonnes of cassava chip7/ and 1.4 million tonnes of fresh cassava, and together these accounted for 99.5% of all cassava imports by volume. The balance of supply (9.7%) came from stocks held from the previous year. In total, 68.1% of Thai cassava output was used to supply export markets, with the remainder being distributed domestically, either for direct consumption or for use as an input into industrial processing (Figure 6).

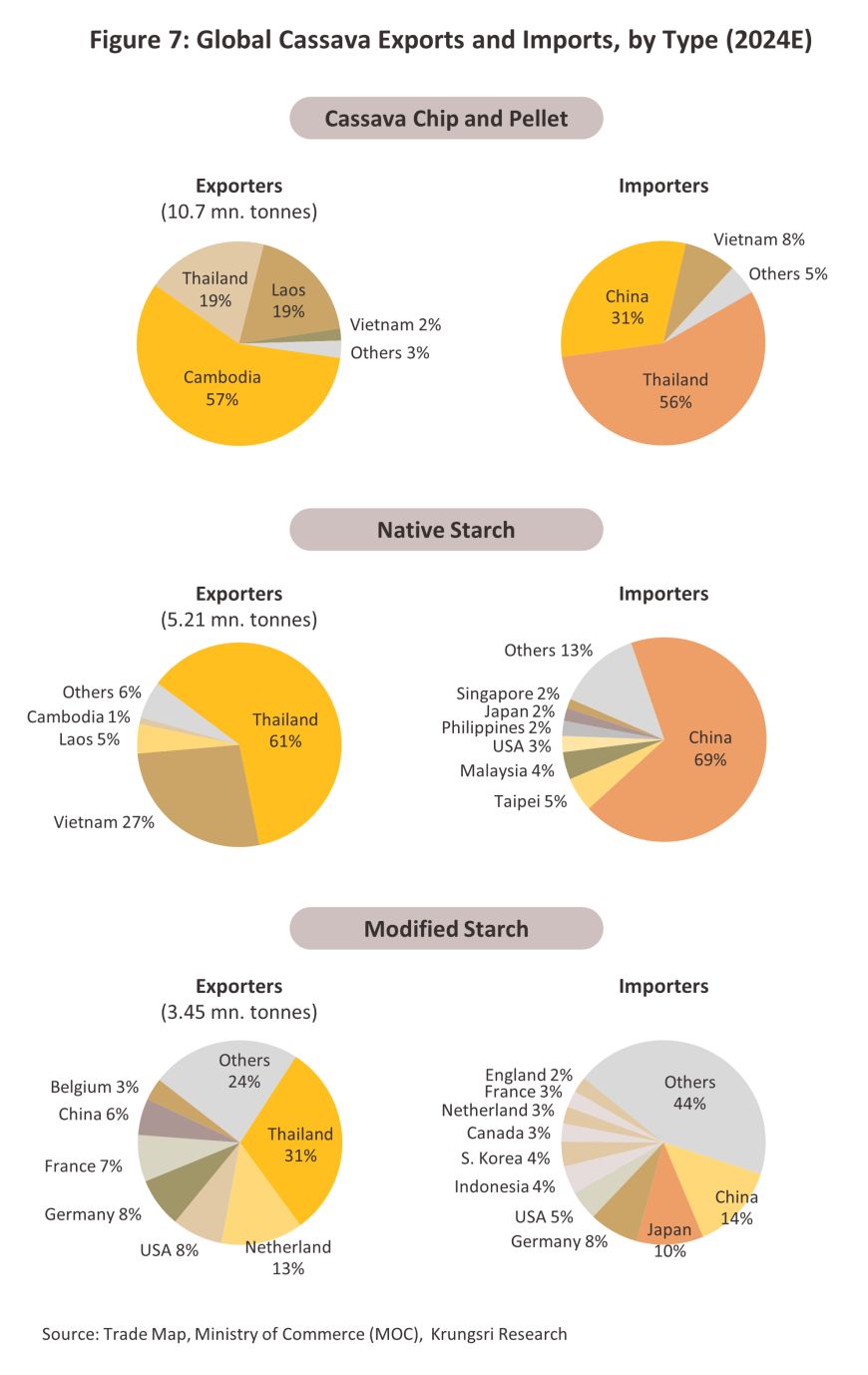

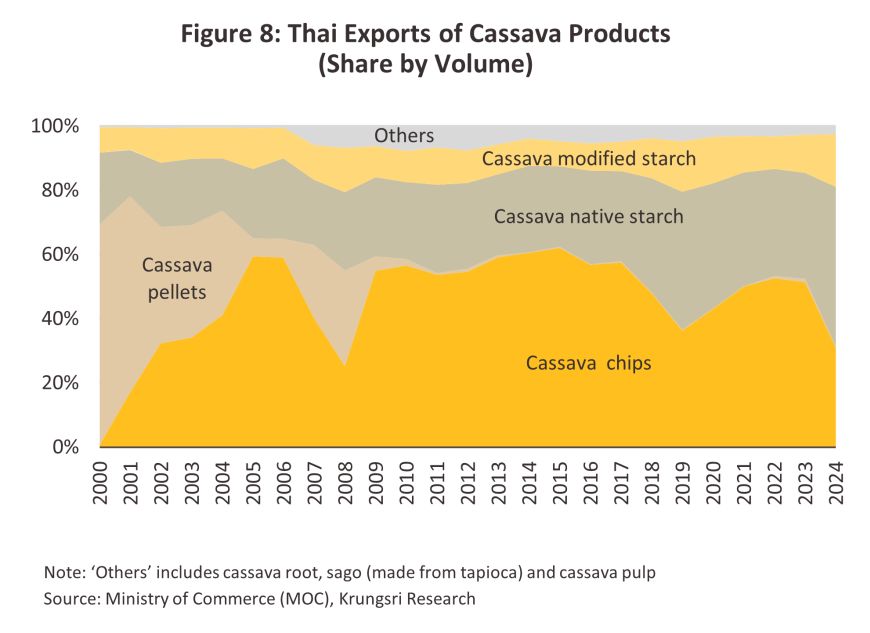

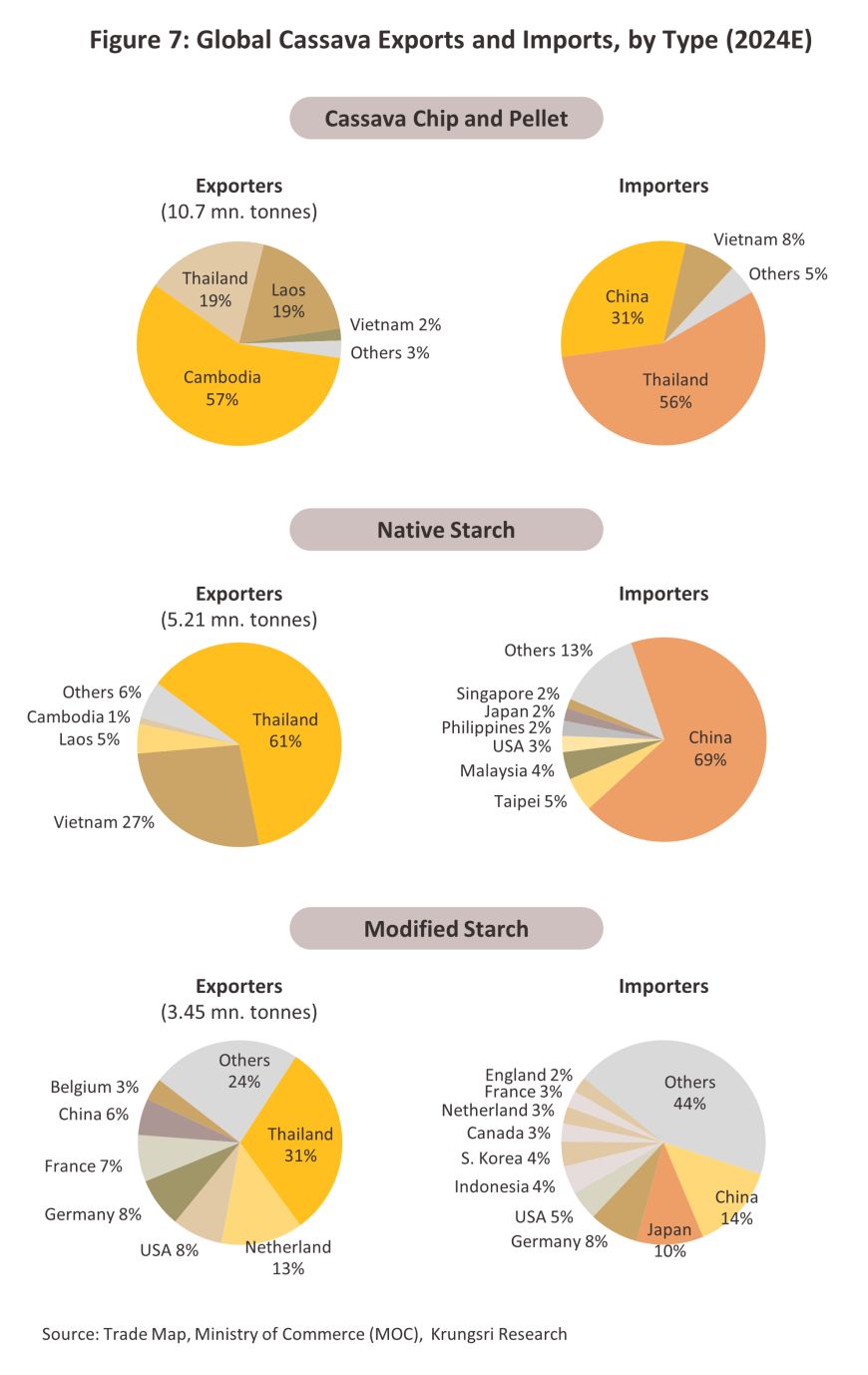

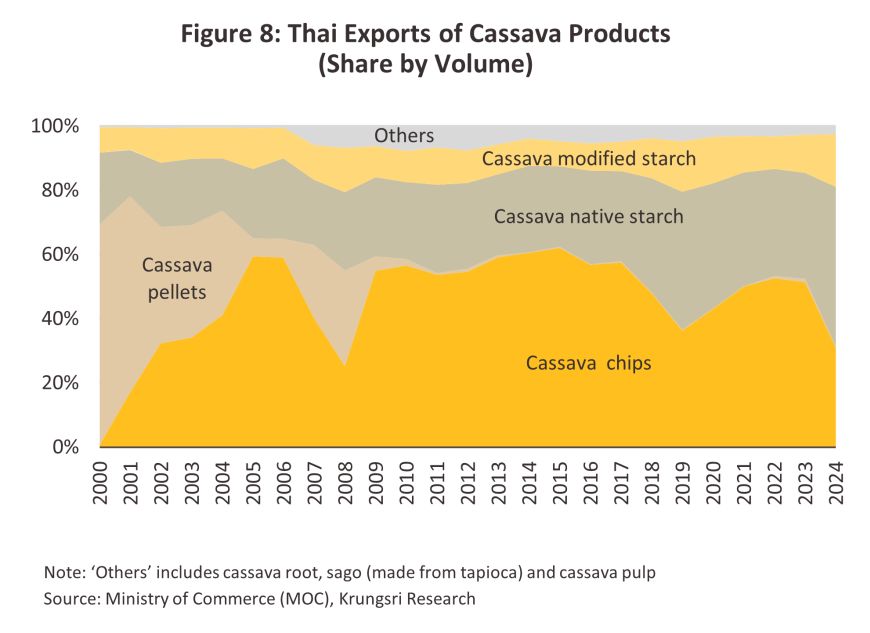

In 2024, Thailand is projected to remain the world's largest exporter of cassava products, securing the top market share at 25% of the total global export volume. Within Thailand's export portfolio, cassava chips account for 19%, native tapioca starch for 62%, and modified tapioca starch for 31% (Figure 7). Conversely, the export volume of cassava pellets is very small. This is primarily due to the European Union (EU), once a major importer of cassava pellets and a key market for Thailand, implementing policies since 200511/ to reduce cassava pellet imports and substitute them with other grains. Consequently, the export value of Thai cassava pellets has progressively declined. Currently, the export market structure for Thai cassava products is almost entirely reliant on the Asian region, particularly China12/, which serves as the number one export market with a 64% share of Thailand's total cassava product export volume. Other significant markets include Japan (6%), Indonesia (6%), Taiwan (4%), and Malaysia (4%). The specific export markets for each type of Thai cassava product are detailed as follows:

-

Cassava chip: In 2024, 31.0% of Thai cassava product exports by volume were of cassava chip (Figure 8), almost all of which went to China (the destination for 99.9% of Thai exports of cassava chip in the year), where it is used to manufacture alcohol, ethanol, animal feed13/, and citric acid. However, the structure of the export market and the extreme concentration of purchasing power means that Thai suppliers have only a weak bargaining position and they are in addition exposed to significant levels of risk should there be a change in Chinese policies towards sourcing imports. This is in fact what happened in 2023-2024, when China cut its imports of cassava chip and switched instead to using corn, with significant knock-on effects for Thai exporters. This led to a significant decrease in Thailand's exports, falling to 2.0 million tons.

-

Native starch: This accounted for 49.6% by volume of all exports of cassava products from Thailand. The main markets for this again include China (which took 59% by volume of all exports of native starch), followed by Indonesia (8%), Taiwan (8%), Malaysia (6%), and the Philippines (3%), although the exact state of export markets depends on the health of the industries that use native starch as an input. These include food processing, paper production, beverages, and textiles.

-

Modified starch: This represents another 16.4% of Thai cassava product exports by volume. Strong global demand has been sustained by a positive outlook for downstream industries, including producers of food products, medicines and cosmetics. The main export markets for modified starch are Japan (which bought 26% of all 2024 exports of modified starch by volume), China (22%), Indonesia (10%) and South Korea (9%).

-

Cassava pellets: The 2005 decision by the European Union to cut imports of cassava pellets had profound impacts on exporters, and pellets now account for just 0.5% of total cassava product exports by volume. This segment has in addition been handicapped by the difficulty Thai players have in competing with similar products made from other crops (e.g., corn, wheat, and barley). The main export markets are now the Netherlands (44% by volume of cassava pellet exports), Japan (15%), and China (15%).

-

Other cassava products: The remaining 2.5% of cassava product exports comes from sales of fresh cassava, sago (made from cassava starch), and cassava pulp. In 2024, the main buyers of these products were New Zealand (41% of exports of these, by volume), South Korea (29%), and China (5%).

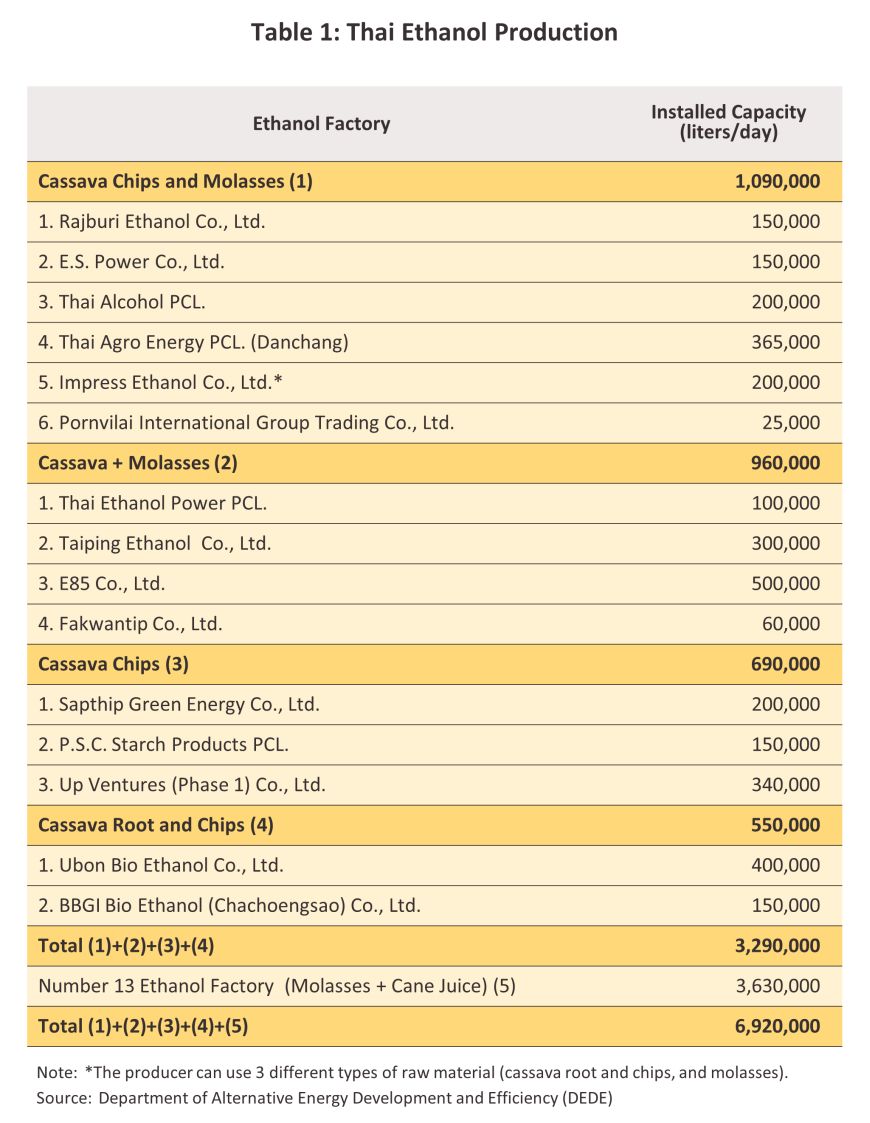

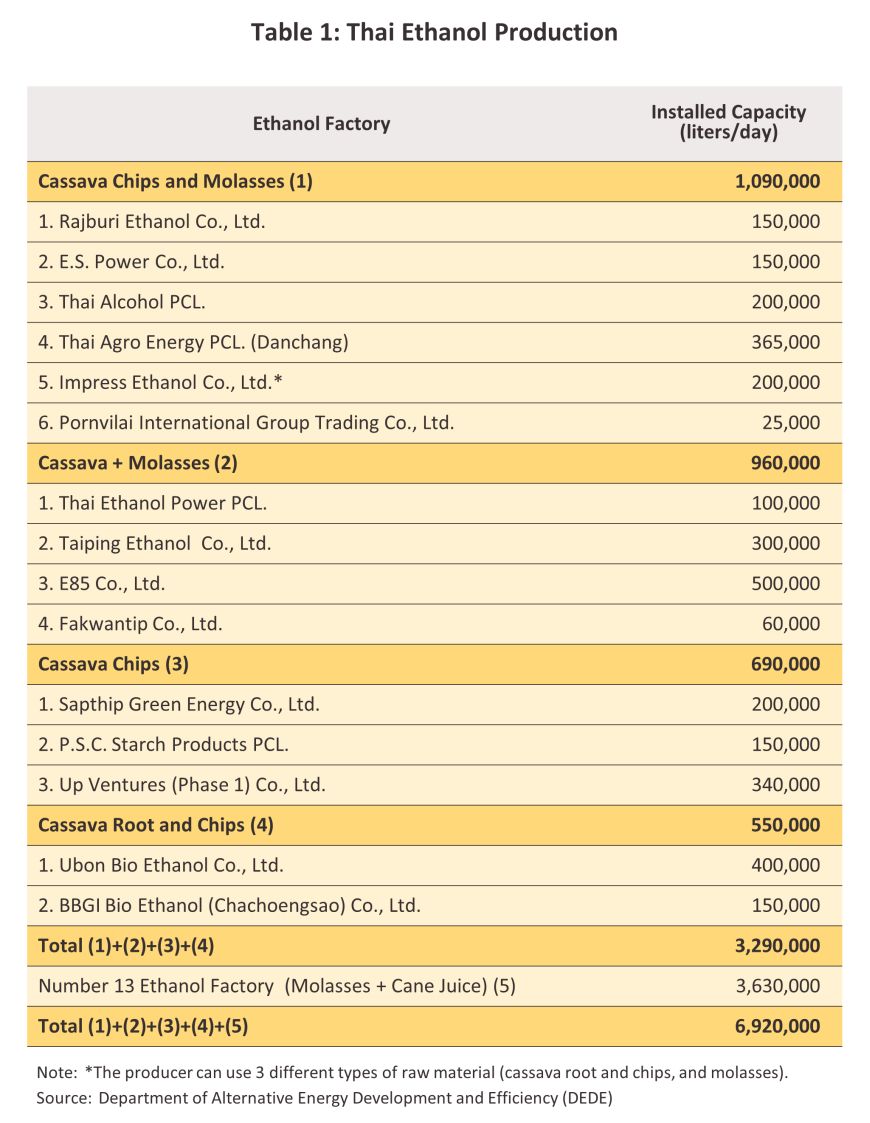

In addition to being consumed directly by households and processed into animal feed, cassava is also used domestically as an input into other industries, including the processing and production of food and beverages, medicines, cosmetics, chemicals, and alcohol. Large players have also invested in downstream industries, including ethanol production and the generation of bioenergy from cassava pulp and other waste products. The electricity that is produced from this may then be sold on or used by the cassava processor itself (Table 1).

Situation

The industry contracted through 2024. On the supply side of the market, a combination of drought and then flooding undercut outputs and deprived processors of inputs, while on the demand side, consumption of cassava chips was undercut by the switch in China (the main market) to the use of their domestic corn as an input for further processing. The sharp dislocation that resulted from these shifts then caused cassava prices to drop.

-

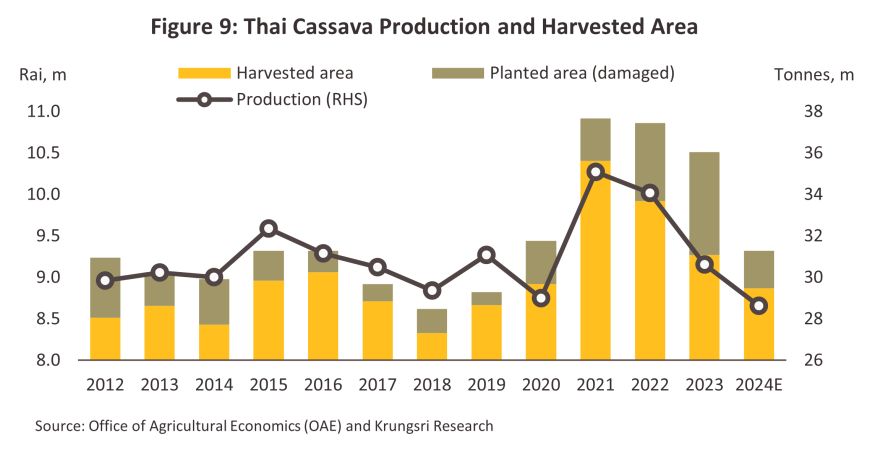

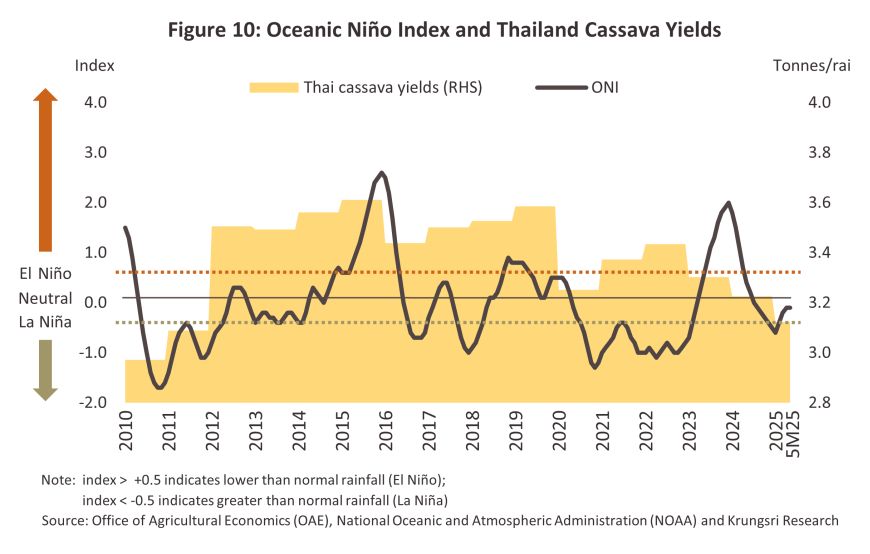

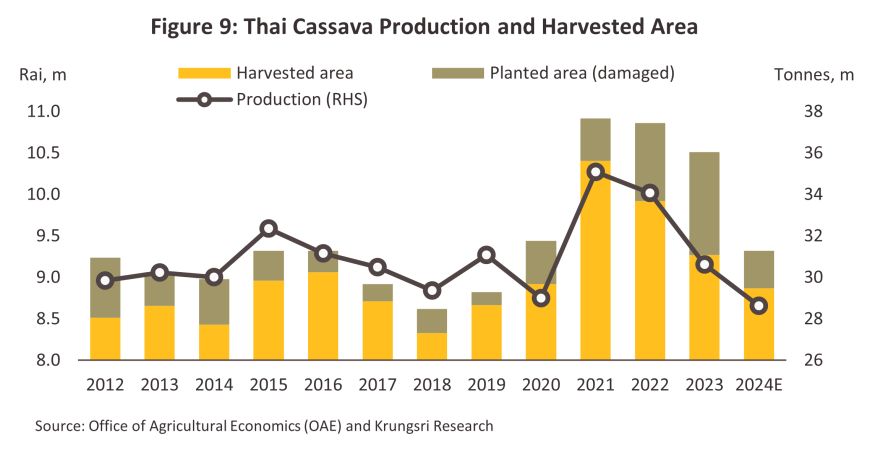

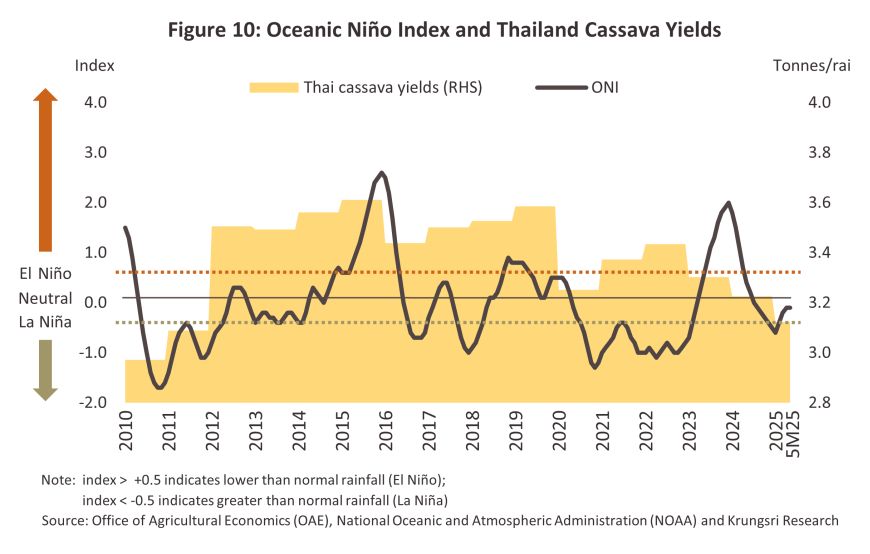

Outputs declined in the year, with data from the Office of Agricultural Economics indicating that these dropped -6.5% to a total of 28.6 million tonnes in 2024, the same time, the total harvested area contracted -4.3% to 8.9 million rai. Per unit yields thus declined -2.4% to 3,226 kg/rai (Figure 9). This was a result of: (i) farmers are facing a shortage of cassava stem cuttings, due to flooding in 2022 that then restricted access to the cuttings needed for planting in the 2023/2024 growing season, and with prices for these rising, some farmers switched to alternative crops; (ii) in the 2023/2024 growing season, below-average rainfall through the 1H2023, combined with the onset of an El Niño that lasted from the 2H2023 through to the 1Q2024 to delay and disrupt monsoon rains (Figure 10); (iii) per-unit yields are dropping due to the continued spread of cassava mosaic disease, to which was added the additional destruction caused by pest infestations; and (iv) high prices for fertilizer and other agricultural chemicals, which forced growers to cut back on applications, further damaging outputs. These factors collectively resulted in a reduction in both planted area and overall output, causing some processing plants to gradually cease operations due to raw material shortages. Through the first 5M2025, the fresh cassava production index slipped by another -4.0% YoY on the combined effects of the El Niño (and resulting heat and drought) that the country experienced in the 1H2024 and the flooding that was then seen in the second half of the year.

-

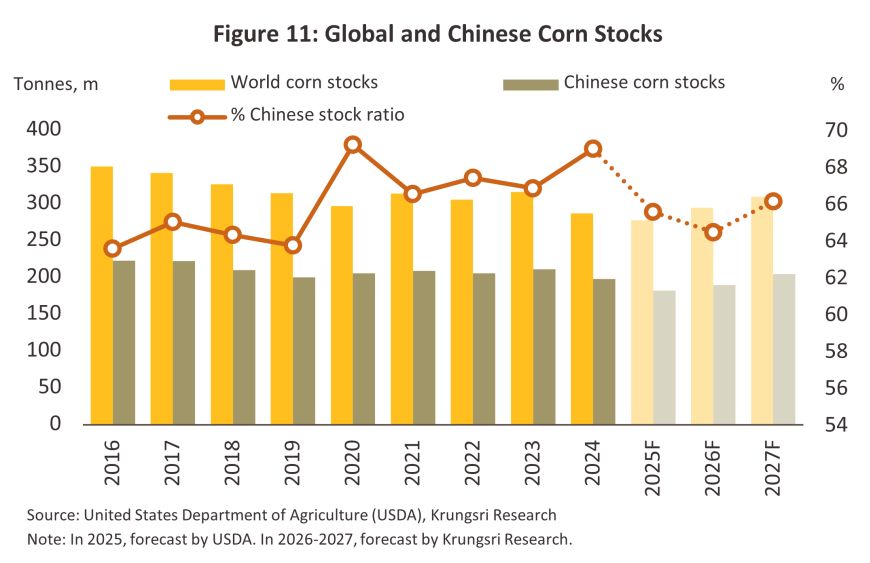

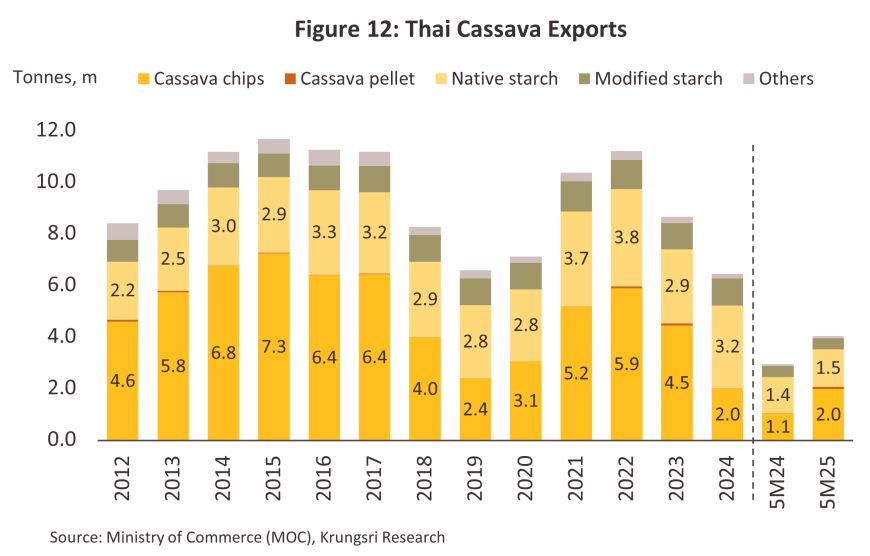

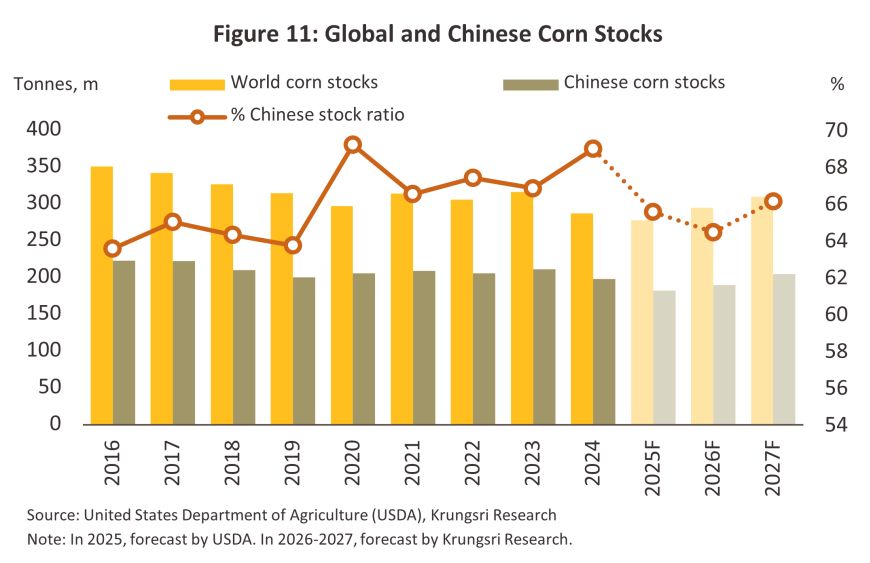

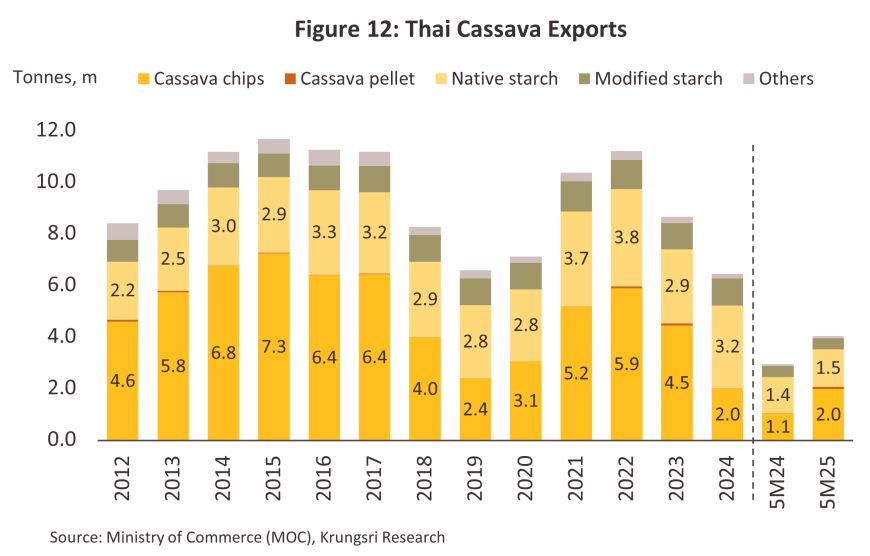

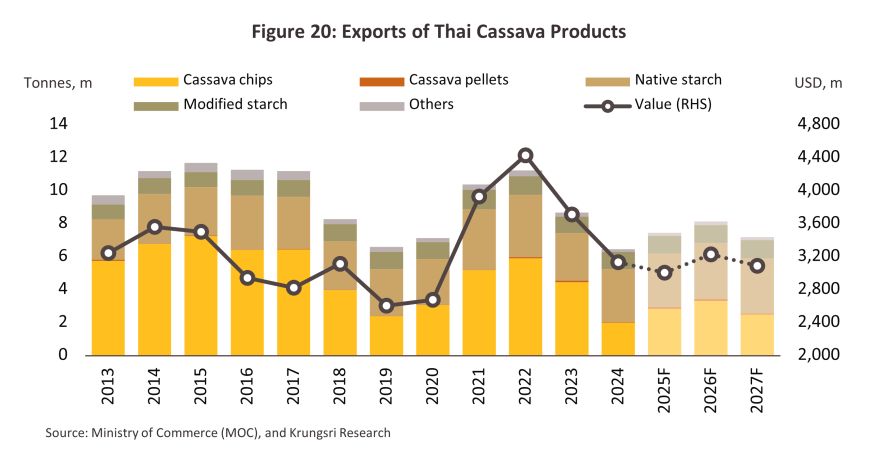

Exports likewise declined in 2024. This was caused primarily by policy shifts in China that then undercut sales. (i) The Chinese government is encouraging the domestic production of appropriate crops to maintain stability of supply. This is being achieved through a mixture of rural recovery and productivity gains in domestic farming, especially in corn production14/, which implies an accompanying decline in imports. (ii) Following pandemic-inspired worries over food security and the resulting run up in food stocks, these are now being run down again (Figure 11) and as such, Chinese purchases have gone into reverse. Thus, total global imports of cassava products to China shrank -27.9% in the year, though this was most pronounced for imports of cassava chips, which crashed -55.9%. Exports of Thai cassava products to China slumped -37.3% to 4.1 million tonnes, down from 6.6 million tonnes a year earlier, though again, declines were sharpest for cassava chip, these falling -54.5% to just 2.0 million tonnes. Having already fallen by respectively -22.7% and -16.2% in 2023, exports of Thai cassava products were therefore down by -25.6% by volume (to 6.47 million tonnes) and -15.6% by value (to USD 3.13 billion). This was somewhat offset by gains in secondary markets, including Indonesia (+260.6% by volume), the US (+28.1%), the Netherlands (+65.8%), Malaysia (+5.3%) and Taiwan (+4.0%), but with sales into the segment’s main market performing so badly, stock holdings rose sharply and prices for almost all cassava products dropped. Through the first 5M2025, exports of cassava products bounced back to growth of 37.3% YoY, or to 4.06 million tonnes as demand for cassava chips recovered. However, with competition still intense and players engaging in a process of destocking, prices came under pressure and so export earnings fell -7.1% YoY to USD 1.35 billion. The situation in individual export segments is described below (Figure 12).

-

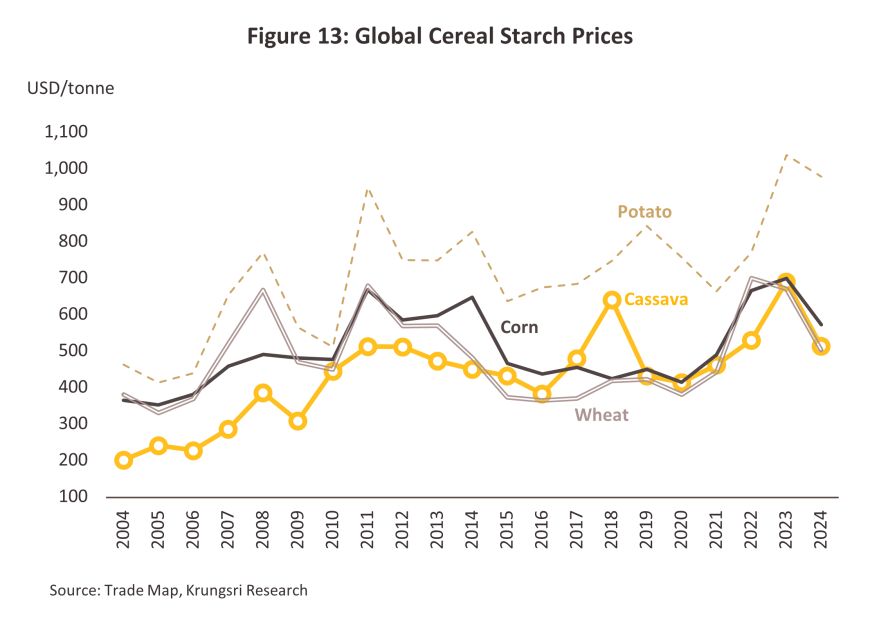

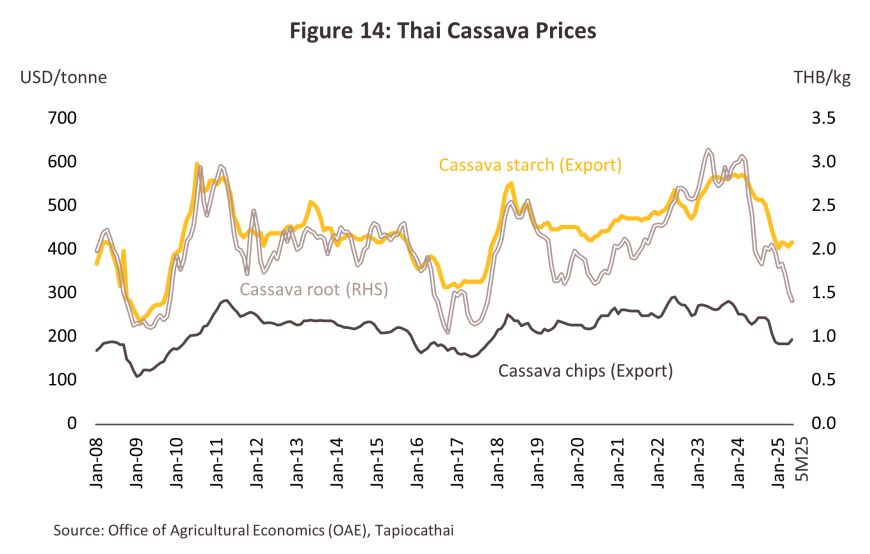

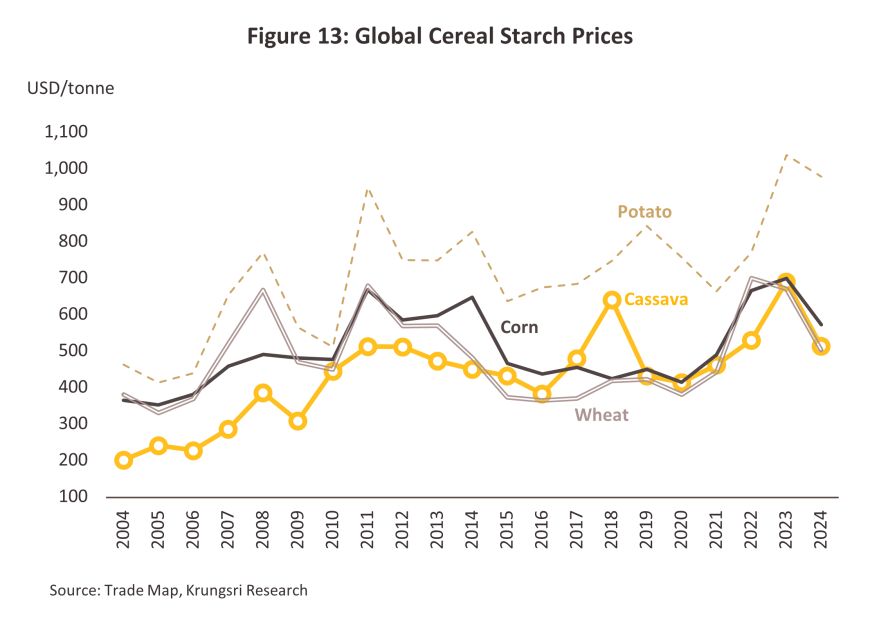

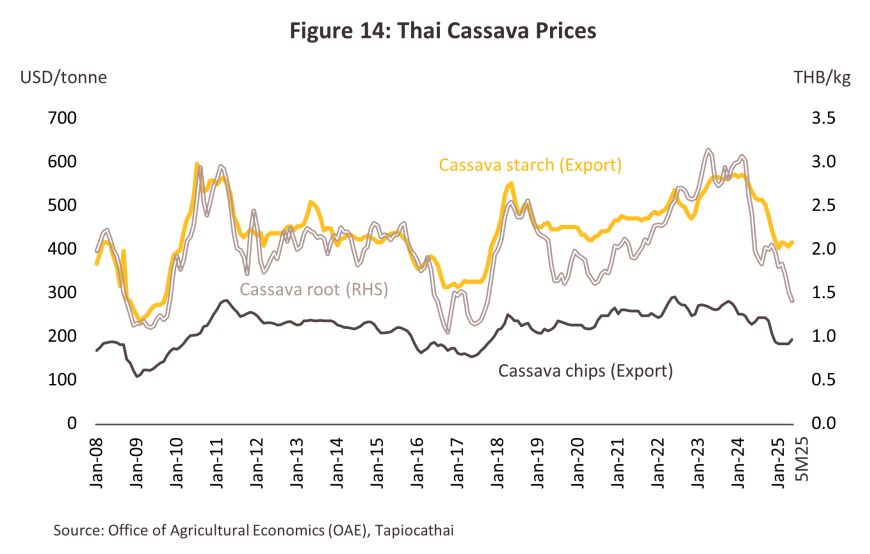

Native starch: 2024 exports totaled 3.2 million tonnes, up 11.7% on stronger demand from downstream industrial consumers, in particular for processing into food, beverages, and food additives and flavorings. Growth was seen in the main market of China (+2.2%), as well as in less important markets including Indonesia, where imports surged 1,816.6% as companies rushed to replace losses resulting from drought and cassava mosaic disease, the USA (+27.2%), Taiwan (+4.0%), the Netherlands (+85.2%) and Malaysia (+4.3%). At the same time, export earnings came to USD 1.6 billion (+8.2%). Global cassava flour prices slumped -25.4%, ahead of declines in prices for alternatives including wheat flour (-24.9%), corn flour (-18.6%) and potato flour (-5.7%) (Figure 13), though prices for exports of Thai native starch softened by just -3.3% to touch USD 512/tonne (Figure 14). Over the first 5M2025, exports inched up by another 1.5 million tonnes (+4.0% YoY), but thanks to falling production costs and intense competition, prices were down -28.1% to an average of USD 397/tonne, and so earnings came to just USD 0.6 billion (-25.3% YoY).

-

Cassava chips: Exports slumped -55.0% to 2.0 million tonnes, though earnings fell at the even faster rate of -59.1% to total just USD 472.8 million. The market suffered under the impact of: (i) the switch by Chinese industrial consumers from cassava chips to domestically produced corn, for which prices slumped following the move by sellers to run down sizeable stock holdings; (ii) the shift by ethanol producers to an increased reliance on using coal as an input; and (iii) the harvesting of cassava when supplies were tight during the drought, although this resulted in poor-quality outputs that had a low starch content. As a result, average prices dropped -11.6% to USD 232/tonne. Over the first 5M2025, exports jumped 90.7% to 2.00 million tonnes on a rebound in orders from China, although average price dropped -25.1% YoY to USD 183/tonne from falling of input costs and intensity of price competition as players sold off old stock. As a result, receipts from overseas sales increased at 42.8% YoY to USD 366.9 million.

-

Modified starch: Exports expanded 3.6% to 1.1 million tonnes by volume and rose 1.8% to USD 948.5 million by value as global demand for starch from manufacturers and producers of food, sweeteners, paper, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics remained solid. Growth was seen not only in the main market of China (+0.4%) but also in the secondary markets of Indonesia (+19.9%), the USA (+25.2%), Singapore (+37.2%) and Malaysia (+11.5%). However, the cost of production, influenced by the declining price of fresh cassava roots and intensifying price competition within the modified starch industry, pushed average export prices down to USD 893/tonne (-1.9%). For the 5M2025, exports remained broadly flat (+0.2% YoY to 0.4 million tonnes), though prices dropped -8.1% to USD 835/tonne, and so earnings were down -7.9% YoY to USD 366.4 million.

-

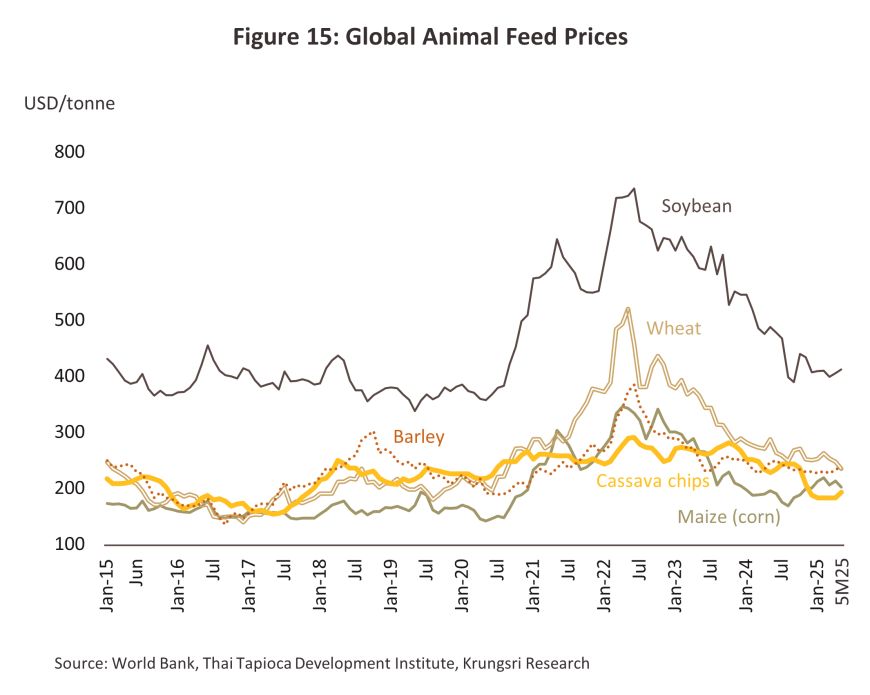

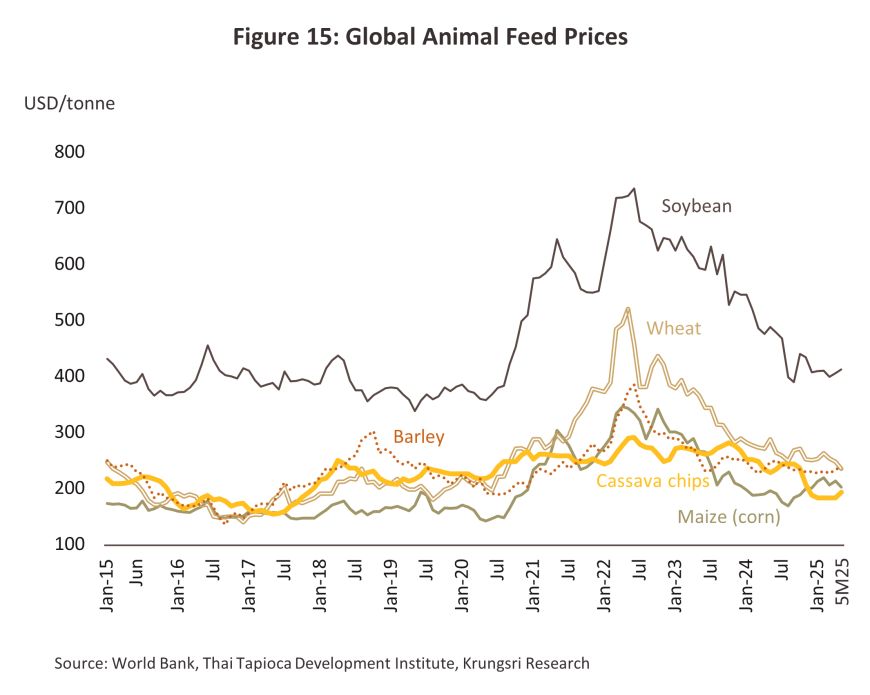

Cassava pellets: Exports slumped in the year, crashing -69.2% to 29,187 tonnes, with earnings moving similarly to fall -67.6% to USD 8.9 million. The segment was devastated by the almost complete collapse of the Chinese market (-94.7%) that resulted from China’s switch from importing cassava pellets to using domestically grown corn, especially in the power sector and among manufacturers of animal feed (Figure 15). This then pulled down average export prices, which slipped -4.6% to USD 320/tonne. Over 5M2025, exports then rebounded, jumping 806.6% YoY to 81,771 tonnes, though this is explained by baseline effects and the move by sellers to run down aging stocks. The latter accelerated competition on price, causing price to drop by another -36.7% to an average of USD 199/tonne. Consequently, growth in receipts rose at only half the pace of export volume, climbing 474.1% to USD 16.3 million.

-

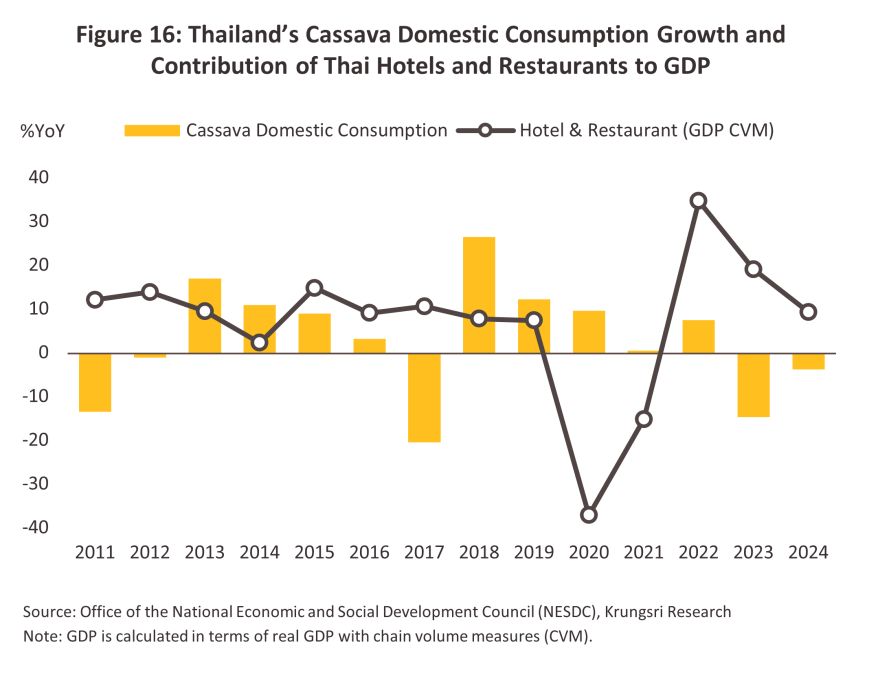

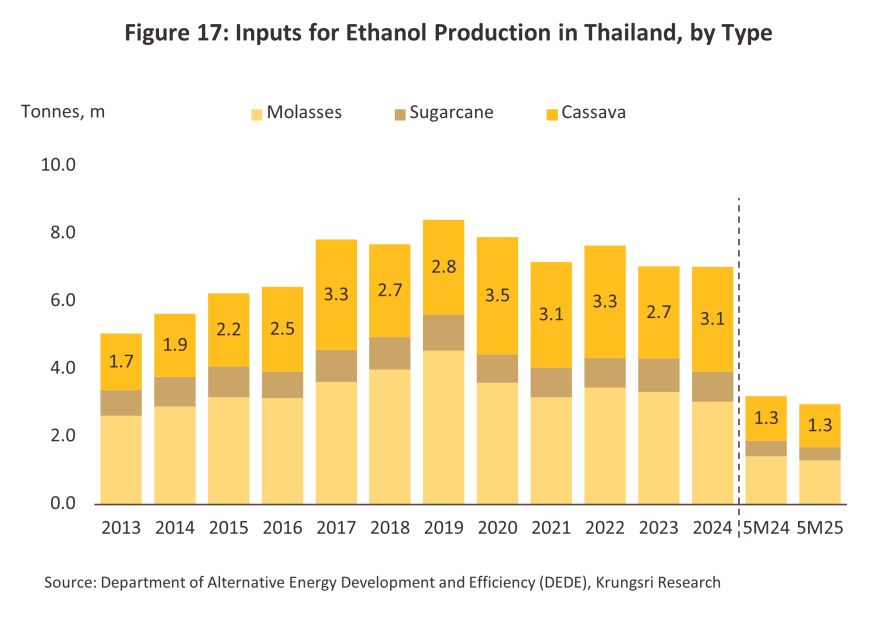

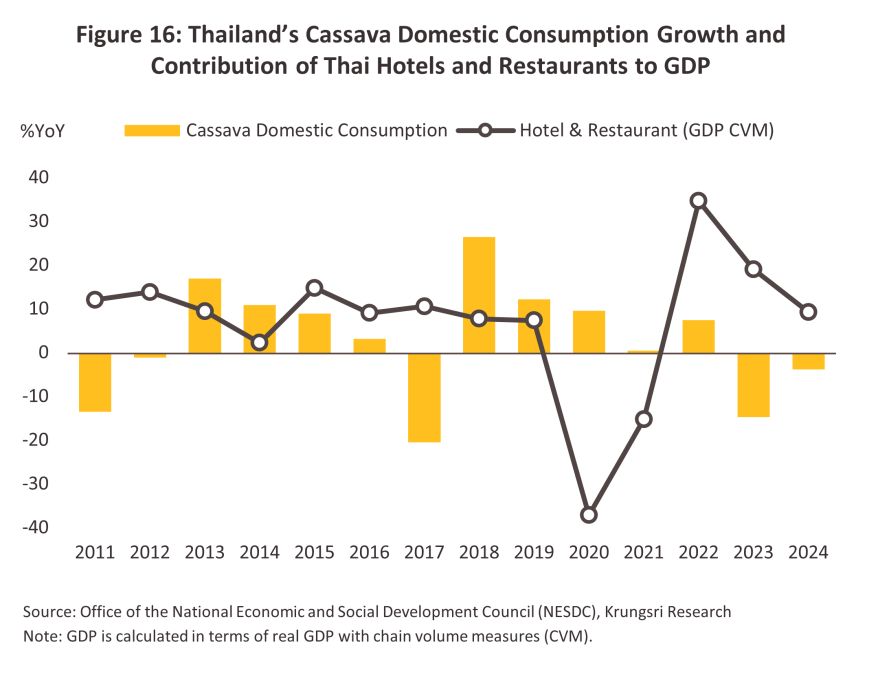

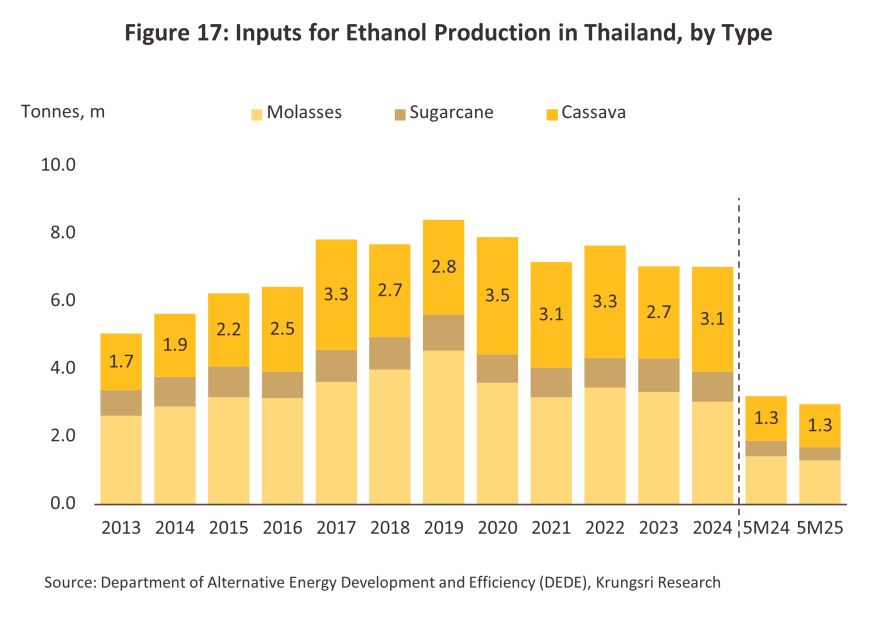

Domestic demand slipped -2.1% to 10.8 million tonnes in 2024, having already softened -14.7% in 2023. Demand from households and from downstream industries fell -7.3% to 7.7 million tonnes of fresh cassava on the back of slowing growth in overall household expenditure and a worsening outlook for hotels and restaurants (Figure 16). More positively, demand for cassava for use in the production of ethanol jumped 14.0% to 3.1 million tonnes (Figure 17). This increase was driven by: (i) the drop-off in demand for cassava chips from China that then helped to push up domestic stock holdings and to cut prices by more than -20%; and (ii) the impact of El Niño, which caused a 24% increase in sugarcane price, thereby increasing demand for cassava as a substitute for cane and molasses in ethanol production.

-

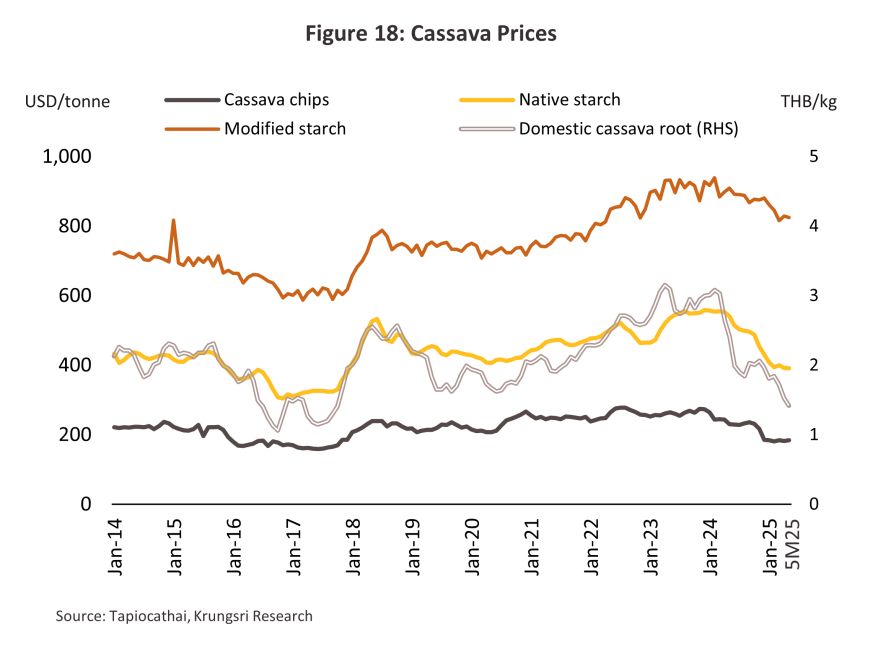

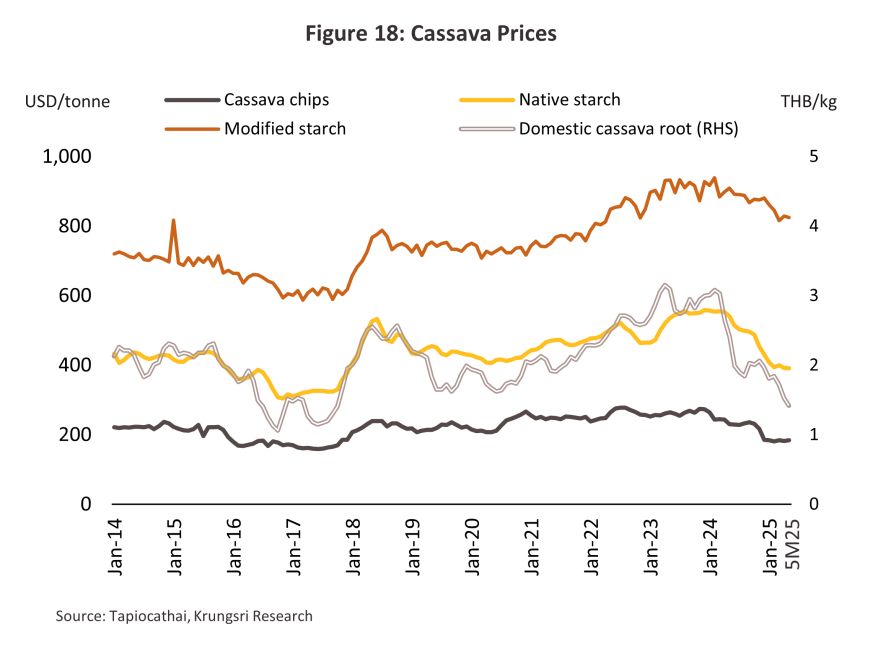

Domestic prices for fresh cassava averaged THB 2.33/kg over 2024. These were thus down -19.8% against a rise of 15.3% (to THB 2.91/kg) a year earlier (Figure 18). Declines were driven by: (i) softer demand on both domestic and export markets; and (ii) the harvesting of worse-quality produce with a lower starch content, which was itself a result of: (ii.1) drought and the continuing spread of cassava mosaic disease; and (ii.2) the replanting of cassava in areas that had been negatively impacted by the climate at the start of the year or that were flooded in its latter half, which then encouraged growers to harvest before their crops were fully grown15/. For the first 5 months of 2025, the price of fresh cassava declined by -41.4% YoY to an average of 1.66 Baht/kg. This decrease was driven by lower quality and starch content, as farmers accelerated harvesting before crops fully matured due to concerns over drought and cassava leaf mosaic disease outbreak.

Outlook

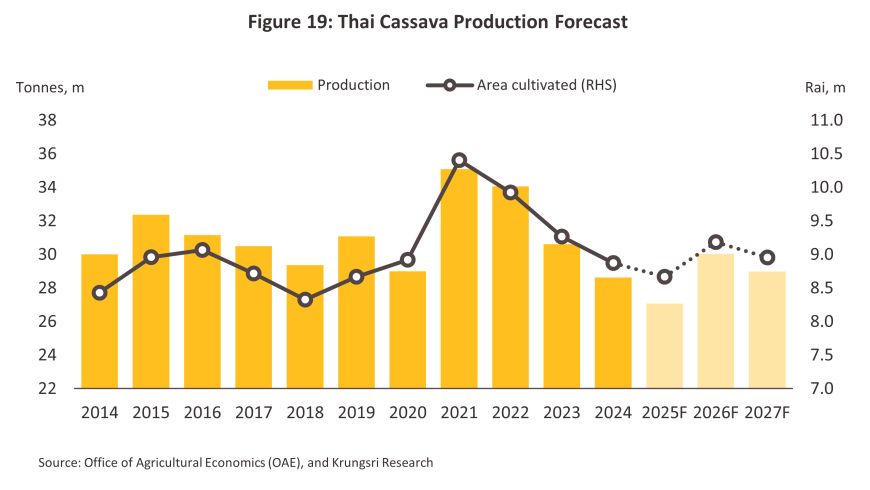

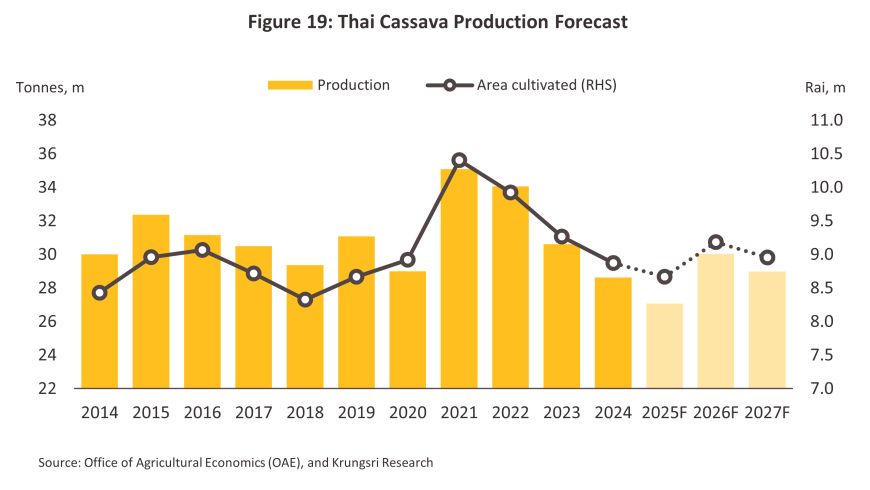

Outputs: Following a fall of -6.5% in 2024, due outputs are expected to remain unchanged or to grow by up to 1.0% annually over 2025-2027 due to fluctuating climatic conditions resulting from the alternating phenomena of El Niño and La Niña.

-

Domestic outputs are expected to contract by between -4.5% and -6.5% in 2025, thus falling to somewhere in the region of 26.8-27.3 million tonnes of fresh cassava. This will be a result of a combination of the El Niño and the consequent below-average rainfall in the 1H2024, along with the continuing spread of cassava mosaic disease and pest infestations. Outputs and per unit yields will therefore be down in 2025. However, in 2026, cassava supply should expand again on the emergence of La Niña and later neutral conditions that will lead to better weather and greater access to water. In light of this, farmers will tend to expand the area under cultivation, while per unit yields will also climb, though baseline effects over the previous 2 years will further boost the figures. In 2026, total national cassava outputs are therefore forecast to expand by 10.0-12.0% annually to 29.8-30.3 million tonnes of fresh cassava (Figure 19). However, the supply of cassava in 2027 is likely to decline by -2.5% to -4.5%, or to 28.7-29.3 million tonnes due to the anticipated return of drought conditions in 2027 coupled with ongoing problems with cassava mosaic disease and pests that tend to spread easily during dry spells.

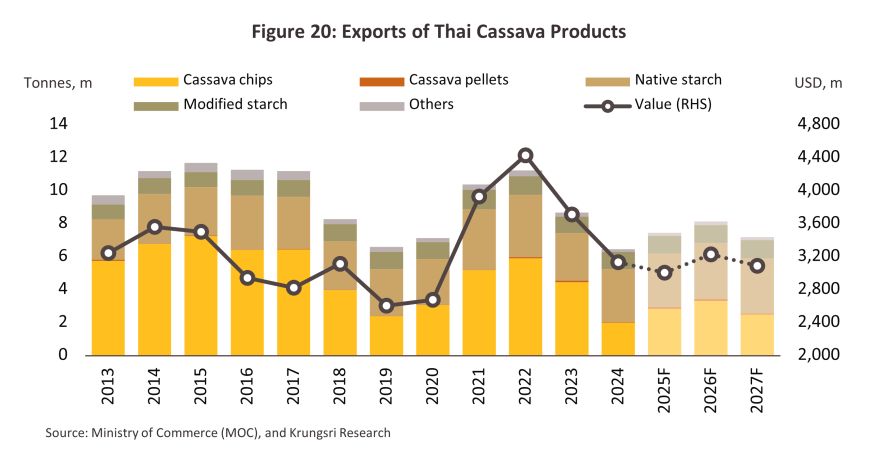

Exports: Export volume is expected to grow by 2.7-4.7% annually over 2025-2027, which would mark a sharp turnaround from -25.6% contraction in 2024. Although in general, export markets will struggle against the headwinds generated by the recent round of US tariff hikes and the resulting undercutting of both economic certainty and growth in spending power, exports of cassava should still expand through 2025 and 2026. This is a result from several factors, (i) Chinese players will need to source alternatives to domestic corn, for which stocks have been depleted and prices have risen, and this will tend to add to the demand for cassava coming from downstream industrial processors. (ii) As economies grow in overseas markets, demand for cassava for use in the production and processing of pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, paper, textiles, food and sweeteners will likewise strengthen. (iii) Worsening geopolitical tensions and the intensifying trade war will add to worries over food security, and many countries will respond to these challenges by rebuilding stocks of food and other agricultural products. (iv) Domestic supply for exports will benefit from ongoing destocking. (v) Comparison with the low baseline set in 2023 and 2024 will add a further boost to the data. However, the outlook will worsen in 2027, when exports are forecast to weaken again on: (i) the possible return of El Niño conditions and the resulting supply shortages; (ii) an expansion in the supply of corn (an alternative to cassava) to the Chinese and world markets; and (iii) an intensification in competition, especially from players in Cambodia. Details of the outlook for individual segments are given below (Figure 20).

-

Native starch: Exports are forecast to increase by 0.6-2.6% annually to 3.3-3.4 million tonnes. Sales will be boosted by strengthening demand from Chinese industrial consumers, though at the same time, headwinds will come from: (i) competition on price from alternative flours, especially corn flour, which will encourage Chinese players to increasingly substitute this for cassava; and (ii) increasing supply to the Chinese market from competitors in the CLMV nations16/, where Chinese companies have been investing in local cassava farms and processing plants for some years.

-

Cassava chip: By volume, annual exports are expected to jump 6.6-8.6% to 2.5-3.3 million tonnes. Higher prices for corn in China will encourage Chinese buyers to switch to cassava through 2025 and 2026, but in 2027, the possible transition to El Niño conditions may reduce access to inputs and so exports of cassava chips from Thailand to China could go into reverse, although demand will remain strong.

-

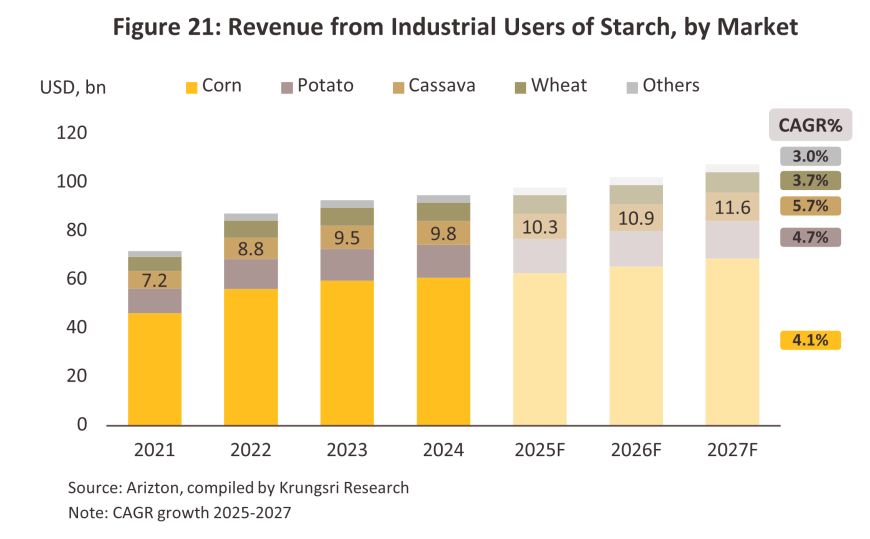

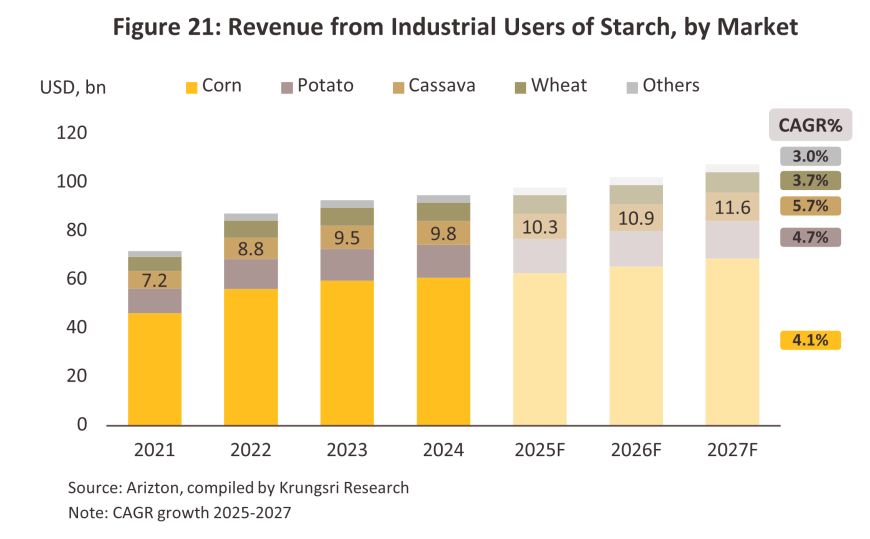

Modified starch: Overseas sales should run to 1.06-1.10 million tonnes annually, which would then represent a rise of 0.1-2.1%. Demand will be driven by sales into downstream industries including food and beverage processing and the manufacture of paper, sweeteners, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Arizton sees the global market for modified starch derivatives enjoying compound annual growth of 4.3% over 2025-2027 (Figure 21).

-

Cassava pellets: Exports will surge by 18.0-20.0% to an annual total of some 49,100-98,300 tonnes. The market will be lifted by stronger demand from China for use in the bioenergy and animal feed industries, though the data will also be flattered by comparison with 2024’s low baseline. However, as with other segments, the return of an El Niño in 2027 would reduce access to inputs and thus cut exports, though in addition, if local stocks of corn grow, Chinese players will likely switch away from the use of cassava pellets.

Domestic market: The Thai market is expected to strengthen by 0.7-2.7% annually over 2025-2027, supported by three principal sources. (i) Demand from downstream industries should expand at a similar rate of 0.7-2.7% per year. A combination of gradual recovery of overall economic activities and government measures targeting the cassava industry will help boost demand from the food processing industry and from producers of MSG, food additives, paper, textiles, and chemicals. (ii) In response to plans contained in the 2024-2037 Oil Plan that will increase consumption of E20 and E85, improving demand for travel and transport services, an acceleration in the pace of work on government infrastructure projects, and a rise in the number of vehicles on Thai roads that can run on gasohol, sales to ethanol producers are forecast to increase by 0.8-2.8% annually. (iii) Because sugarcane is typically more sensitive than cassava to drought, the emergence of an El Niño in 2027 would add to demand for fresh cassava, cassava chips and cassava starch in place of the cane and molasses used in ethanol production.

Prices for fresh cassava: Prices will fall from 2024’s average of THB 2.33/kg to THB 1.70-2.20/kg through 2025 and 2026 on the back of higher outputs and rising stockholdings, which will outpace combined domestic and international demand. In particular, the authorities in the all-important Chinese market will be focused on maintaining a balance between the domestic supply and demand for food, and as plans to revive rural communities and to overhaul the agricultural sector are implemented, imports of grains and other food crops will decline and instead, reliance on domestically sourced corn will grow. However, as stated above, a possible 2027 El Niño will cut both outputs and stocks of cassava and encourage Chinese buyers to increase imports from Thailand, which would then lift prices for fresh cassava to THB 2.2-2.5/kg.

Headwinds facing the industry will include the following.

-

Competition for inputs will be increased, driven by: (i) tight supply, especially during El Niño conditions, which will force downstream consumers to compete for access to cassava sourced from both Thai suppliers and those in neighboring countries; (ii) the spread of disease, potentially transmitted through infected cuttings or partially processing cassava products; (iii) the Thai-Cambodian border conflict, which may impact access to imports; and (iv) the aging of the rural population and subsequent worsening problems with labor shortages.

-

Market competition remains intense due to the prevalence of alternatives to cassava, the entrance of new players to the market, and ongoing investment by incumbents. As a result, capacity utilization slipped to 51% in 2023-2024, down from 58% in 2021-2022.

-

Overseas buyers, especially in China, will increasingly source goods from countries other than Thailand, most notably Lao PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam. This change is being caused by: (i) the better ability of players in these countries to compete on price; (ii) the construction of 20-30 cassava production facilities in Lao PDR in 2024, with an additional 40 sites by 2026; (iii) the construction of the China-Lao railway, which has helped to cut transportation times and costs; (iv) the development of contract farming networks, new cultivars and improved harvesting technologies by Chinese investors in Vietnam and Lao PDR; and (v) the signing of a China-Cambodia free trade agreement and an MOU promoting economic cooperation between the two countries.

-

The costs associated with growing and processing cassava are rising, due to worsening international environment, examples of which include the conflicts between Russia and Ukraine, Israel and Hamas, and India and Pakistan, as well as recent tariffs imposed by Donald Trump. As a result, production costs are being pushed up, especially for fertilizer and pesticides/insecticides.

-

Official support for the sale of electric vehicles (EVs) includes setting the target of 30% and then 50% of new autos being ZEVs (zero emission vehicles) by respectively 2030 and 2035. In addition, the cut in the standard diesel mix from E20 to E10 may impact the total number of vehicles on the road that can run on gasohol/ethanol.

-

Players are tending to overhaul their production lines and shifting to a greater focus to a higher value-added products (e.g., bio-plastics and renewable bio-polymers) and/or to increase investments in clean energy (e.g., ethanol production and the generation of electricity from biomass). This will then allow companies to extend further across supply chains, build new sources of revenue, and cut marginal costs. This may however also increase exposure to risk arising from competition for access to inputs, especially if an El Niño negatively impacts outputs.

-

Non-tariff barriers to trade are becoming increasingly prevalent in overseas markets. These include those targeting compliance with ESG (environment, social and governance), water and carbon footprint, and broader sustainability measures.ains and other food crops will decline and instead, reliance on domestically sourced corn will grow. However, as stated above, a possible 2027 El Niño will cut both outputs and stocks of cassava and encourage Chinese buyers to increase imports from Thailand, which would then lift prices for fresh cassava to THB 2.2-2.5/kg.

1/ In Asia, cassava is used principally as an input into downstream industries rather than being consumed directly by humans. However, in recent times, many countries have begun to prioritize food security,leading to increased promotion of cultivation for direct consumption or as input for the food industry.

2/ Cambodia is accelerating its cassava production to leverage benefits under the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with China.

3/ While African nations are the world's leading cassava producers, their output primarily serves domestic consumption. This is because cassava plays a crucial role in food security, livelihoods, and the economy within the region.

4/ Data is provided by the Office of Agricultural Economics. Cassava can be grown in poor soils and is drought tolerant so it can be planted year-round, although in Thailand this usually occurs between March and May for harvesting in the period from January to March in the following year.

5/ Data correct as of 16 April 2025, though this does not include unregistered businesses, those that may have suspended or ceased operations, or those that have a size as determined by the Factory Act (No. 2). The data includes cassava processing facilities that output products including pellets, chips, starch, pulp and other goods (source: DIW, DBD, TTSA).

6/ Modified starch is made from native starch that has its physical and chemical properties altered through the application of heat, enzymes, and/or chemicals. This gives the modified starch particularly desirable qualities that then make it more useful in industrial applications, such as making its viscosity less variable, increasing its stability at a wider range of temperatures, and altering its acidity and shear strength.

7/ Equivalent to 7.6 million tonnes of fresh cassava.

8/-10/ see figure 6

11/ The 2005 reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) encouraged member states to increase the area given over to crops that could be used as alternatives to imported cassava. In addition, prices for the former were low, and as such, EU-based producers of animal feed switched from using cassava pellets to different products, most notably potatoes. This has led Thai cassava pellet producers to shift towards increased production of cassava chips for export.

12/ China sources of supplies of cassava for use in its food, energy, ethanol, and animal feed industries are from overseas markets since Chinese farmers prefer to grow other crops (cassava growing imposes high costs, farmers benefit from only weak incentives, and it is difficult to mechanize production). In addition to domestic supply being unable to fully meet demand, the opening of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area means that importers benefit from favorable duties, though they are still liable for 9% VAT on fresh cassava and cassava chips, and 13% VAT on starch products. Given this, inputs of cassava to Chinese industry are largely imported (source: Thai Biz in China Business Information Center).

13/ To produce a nutrient profile similar to corn, animal feed is made by mixing 87% cassava chip with 13% soy pulp.

14/ Chinese policy on food security has led into a drop in imports of cassava. These policies encompass: (i) the ‘No. 1 Central Document’ issued on 13 February, 2023, which focuses on supporting rural growth and upgrading the agricultural sector to maintain stability of food production and supply (this includes an expansion in corn cultivation); (ii) the issuing of new food security regulations effective on June 1st, 2024, specify that national food production should aim at self-sufficiency, partly through ensuring a domestic supply of cereal crops and reducing imports; and (iii) the 14th five-year plan for agricultural and rural development (2021-2025), which aims to expand corn and soy cultivation and so to raise annual cereal and grain production to 650 million tonnes, in part by further developing farmland and increasing the use of agritech.

15/ Cassava typically takes 10-12 months to grow to maturity. Crops that are replanted or that are planted after the main rice harvest will therefore typically not be fully mature by the time that they are harvested and so they may be of inferior quality and may have a lower starch content.

16/ Over the past few years, Chinese players have been investing in cash crops and basic processing facilities in countries in the region, including Cambodia (rubber, acacia, cassava and sugarcane), Lao PDR (rubber, sugarcane, corn for animal feed, bananas, cassava, teak and eucalyptus, with most investments being made in the north of the country in areas close to the Chinese border) and Myanmar (rubber, cassava, sugarcane, bananas and watermelons). Source: Chinese Agriculture in Southeast Asia: Investment, Aid and Trade in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

.webp.aspx)