Executive Summary

The Thailand Taxonomy is a national classification framework that divides economic activities into three tiers—green, amber, and red—based on their level of environmental sustainability. Currently, it applies to six key sectors that are major contributors to Thailand’s greenhouse gas emissions: energy, transport, agriculture, manufacturing, construction and real estate, and waste management. For businesses, the Thailand Taxonomy provides several advantages. It strengthens credibility with investors and trading partners by enabling firms to disclose the proportion of revenues and investments aligned with the Taxonomy. In addition, it offers a roadmap for companies to adjust their operations toward greater sustainability, thereby improving their access to sustainable finance. However, although adoption of the Taxonomy is still voluntary, its establishment brings both pressure and challenges for the private sector in two critical areas: (1) collecting and reporting business data consistent with the Taxonomy, and (2) transforming business models toward sustainability, including securing internationally recognized sustainability certifications.

Understanding the Thailand Taxonomy: A Standard for Classifying Sustainable Economic Activities

As the climate crisis intensifies, the world is accelerating its transition toward achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Thailand is no exception, having publicly committed on the global stage to reach net-zero emissions by 2065. In response, the government has been advancing green legislation and regulations, such as the Climate Change Act and a carbon tax. At the same time, the private sector is increasingly proactive, responding to pressures from both domestic and international measures, including the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). As a result, we have seen more organizations setting net-zero targets and investing in carbon reduction projects, which has, in turn, fueled rapid growth in the green finance market that supports environmentally friendly investments.

Amid this expansion, the risk of greenwashing arises when businesses claim to be “green” without actually reducing their environmental impact. This makes it difficult for financial institutions, investors, and consumers to accurately identify genuinely sustainable activities. The Thailand Taxonomy was introduced as a tool to screen and classify environmentally sustainable economic activities, enhancing transparency in the sustainable finance market and supporting the country’s net-zero ambitions.

This article focuses on exploring the Thailand Taxonomy, which was most recently launched in May 2025, and evaluates its benefits, impacts, challenges, and opportunities for stakeholders across various economic sectors.

What is the Thailand Taxonomy?

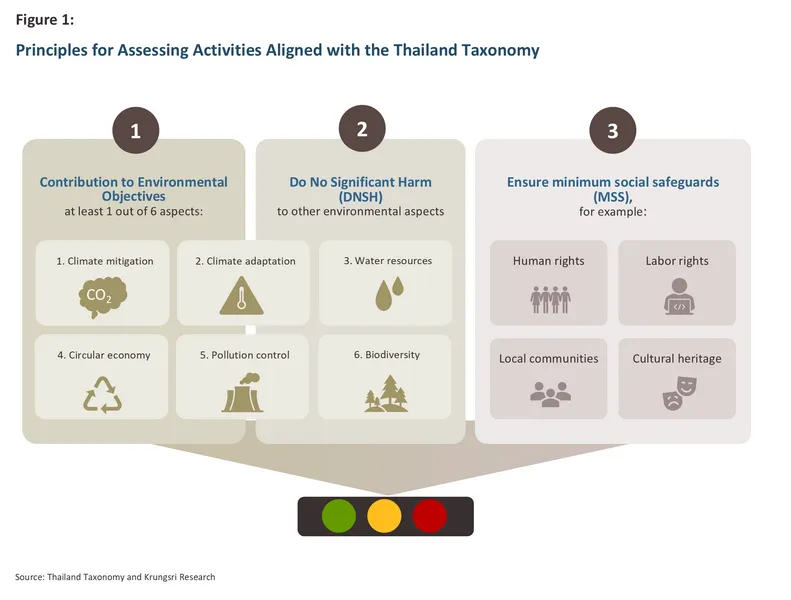

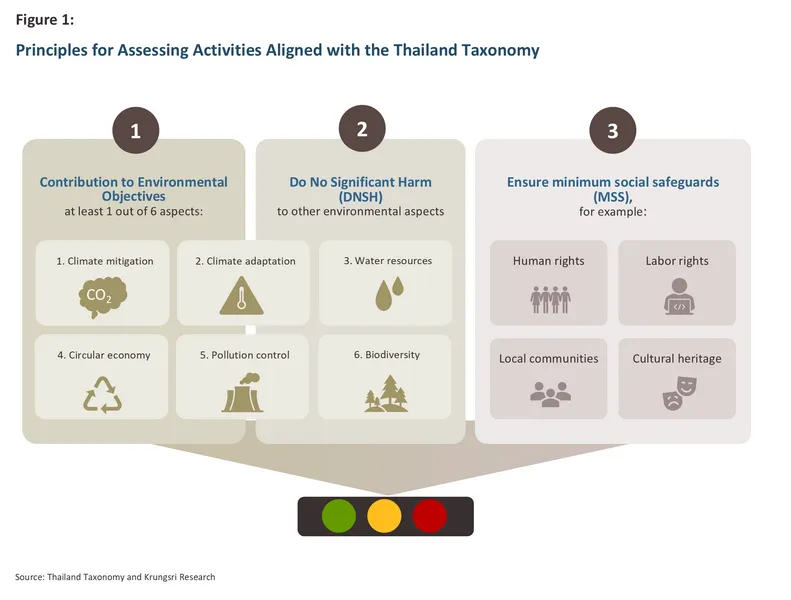

The Thailand Taxonomy is a classification framework that defines and categorizes economic activities based on their environmental impact. It applies technical screening criteria to determine whether an activity qualifies as environmentally friendly.1/ While the Taxonomy primarily emphasizes environmental criteria, activities that align with it must also meet broader sustainability requirements, taking into account both environmental and social dimensions. Specifically:

-

Contribution to Environmental Objectives: Activities must make a substantial contribution to at least one of six environmental objectives, namely, (1) Climate Change Mitigation, (2) Climate Change Adaptation, (3) Sustainable Use and Protection of Water Resources, (4) Transition to a Circular Economy and Sustainable Resource Use, (5) Pollution Prevention and Control, and (6) Protection and Restoration of Ecosystems and Biodiversity.

-

Do No Significant Harm (DNSH): Activities must not cause significant adverse impacts on the remaining five environmental objectives.

-

Minimum Social Safeguards (MSS): Activities must uphold social considerations, including human rights, labor rights, community well-being, and cultural heritage, in line with international standards such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) Core Conventions and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

For instance, a wind power project may contribute significantly to reducing carbon emissions, yet if it generates excessive noise that disturbs wildlife or involves unfair labor practices, it will not qualify under DNSH and MSS. In such cases, the responsible entity must prepare and implement a remediation plan within three years; otherwise, the project will be considered non-aligned with the Taxonomy.

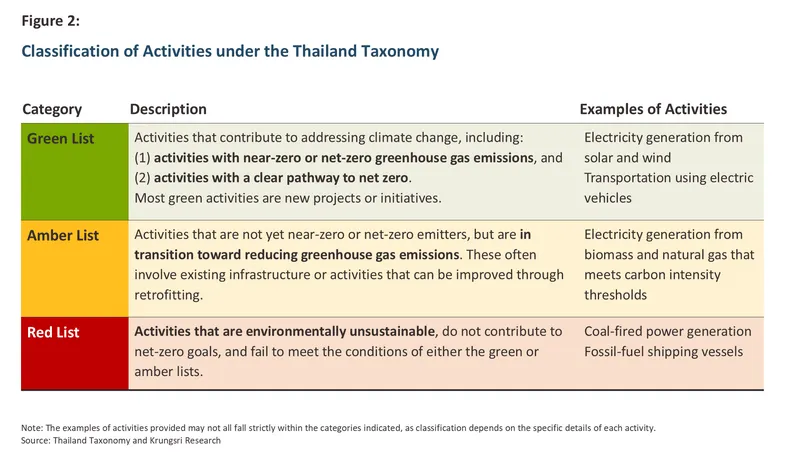

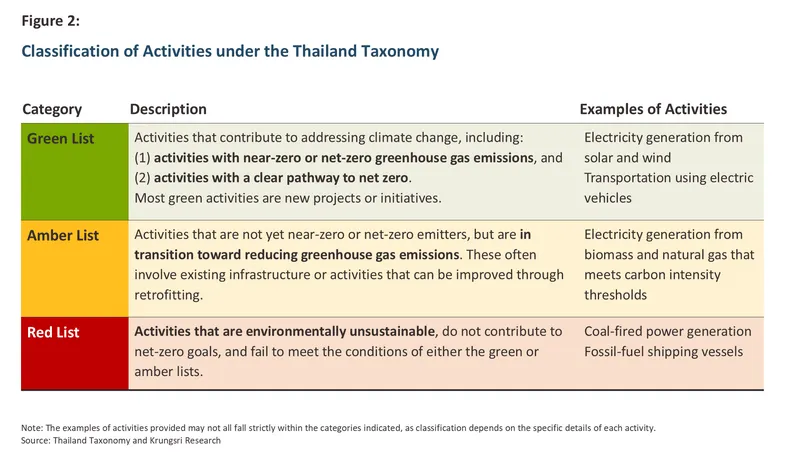

The classification of activities under the Thailand Taxonomy is structured into three levels of environmental performance, following a “traffic-light system.” Green refers to activities that make a substantial contribution to climate action, such as electricity generation from solar power. Amber represents transitional activities that are in the process of becoming more environmentally sustainable, for example, natural gas power plants that meet carbon intensity thresholds. Red refers to activities that are environmentally unsustainable, such as coal-fired power generation. A detailed explanation is provided in Figure 2.

The inclusion of the amber category provides businesses that continue to face challenges in reducing carbon emissions with additional time to adapt. This differs from the European Union’s Taxonomy (EU Taxonomy), which recognizes only green and red activities. However, amber activities must demonstrate measurable improvements in line with criteria established from the best-performing practices within their sector (“best in class”). Moreover, the sunset date for amber activities is set at 2040, after which such activities will no longer be permitted under the Thailand Taxonomy. This requirement is intended to encourage all sectors to transition their investments toward green activities and technologies.

Which economic activities does the Thailand Taxonomy cover?

Currently, the Thailand Taxonomy encompasses activities across six sectors, implemented in two phases as follows:

-

Phase 1: Launched in June 2023, this phase initially focused on the energy and transport sectors, which are the country’s major greenhouse gas emitters, accounting for approximately two-thirds of national emissions.

-

Phase 2: Published in May 2025, this phase expanded coverage to other sectors, including manufacturing, agriculture, construction and real estate, and waste management.

Collectively, these sectors account for approximately half of Thailand’s GDP while contributing over 90% of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions.2/ Activities within the Taxonomy are divided into three main groups: (1) Construction—such as the development of new power plants; (2) Operation—such as industrial production processes; and (3) Retrofit—such as enhancing energy efficiency in existing buildings.

Economic activities not included in the Taxonomy are considered out of scope, typically because they have limited relevance to climate change mitigation or adaptation, or because there is insufficient scientific evidence to justify their inclusion.

Assessing the Benefits and Impacts of the Thailand Taxonomy

Benefits

The Thailand Taxonomy serves as a tool for classifying the sustainability of economic activities, available for voluntary use by all sectors. It is expected to generate positive outcomes for businesses, the financial sector, and the country as a whole, including:

1. Businesses gain guidance for their transition and greater opportunities to access sustainable financing.

Businesses are likely to benefit from the Taxonomy in several ways, such as:

- Improving corporate image through Taxonomy-aligned reporting: Companies can enhance their reputation by disclosing the proportion of revenues and expenditures aligned with the Taxonomy, potentially attracting sustainability-conscious investors, partners, and customers. For example, B.Grimm Power PCL reported that in 2024, although only 7% of its revenue came from green activities due to its traditional power plant structure, 67% of its capital expenditure (CapEx) was allocated to green initiatives, reflecting its commitment to clean energy technology development.3/

- Guiding business transition towards sustainability: Organizations can use the Taxonomy as a roadmap for improving energy efficiency, reducing carbon intensity, managing supply chains, and encouraging partners to align with the defined criteria. Early adoption of sustainable practices also helps mitigate transition risks associated with increasingly stringent green regulations.

- Opening doors to green business opportunities: The Taxonomy facilitates engagement in sectors such as electric vehicles and related infrastructure, renewable energy components, climate technology, and sustainability services, including carbon assessment, consulting, and verification, which are essential for demonstrating compliance with the Taxonomy.

- Enhancing access to sustainable finance: Activities aligned with the Taxonomy are more likely to secure funding. Green activities—whether improving existing operations or investing in new projects—can access green loans or issue green bonds. Amber activities can also obtain transition loans or bonds. Furthermore, businesses could benefit from government-planned climate funds designed to support private sector investment in carbon-reducing technologies through loans or grants, with the Taxonomy expected to serve as a key eligibility criterion.

2. Financial sector receives a framework to assess risks and design sustainable financial products.

The financial sector can use the Taxonomy as a guide to design financial products that support the transition of Thai businesses and to develop strategies for funding companies aligned with the net zero pathway. For example, banks may review and adjust their lending portfolios to increase green financing, while investment funds may shift allocations toward businesses that comply with the Taxonomy. In addition, the Taxonomy serves as a common tool for effectively assessing risks associated with sustainable financial products and mitigating greenwashing, thereby supporting the sustainable growth of Thailand’s sustainable finance sector.

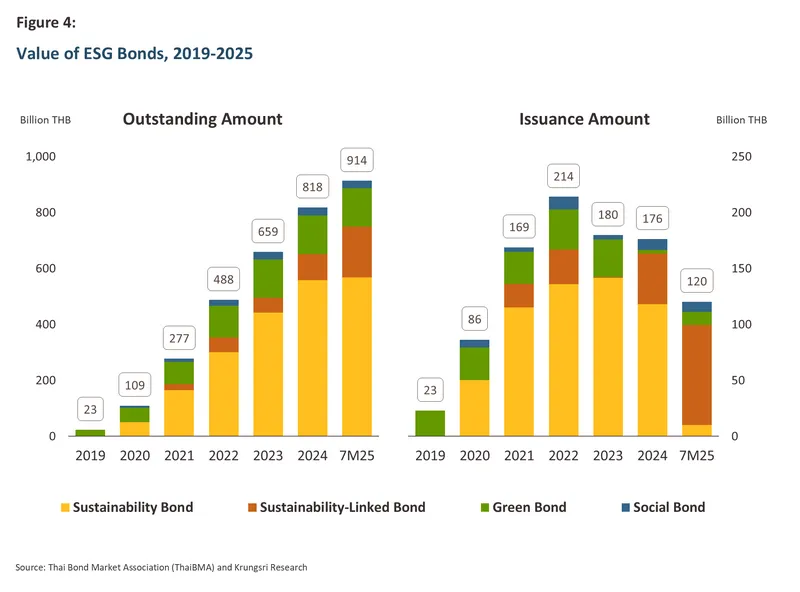

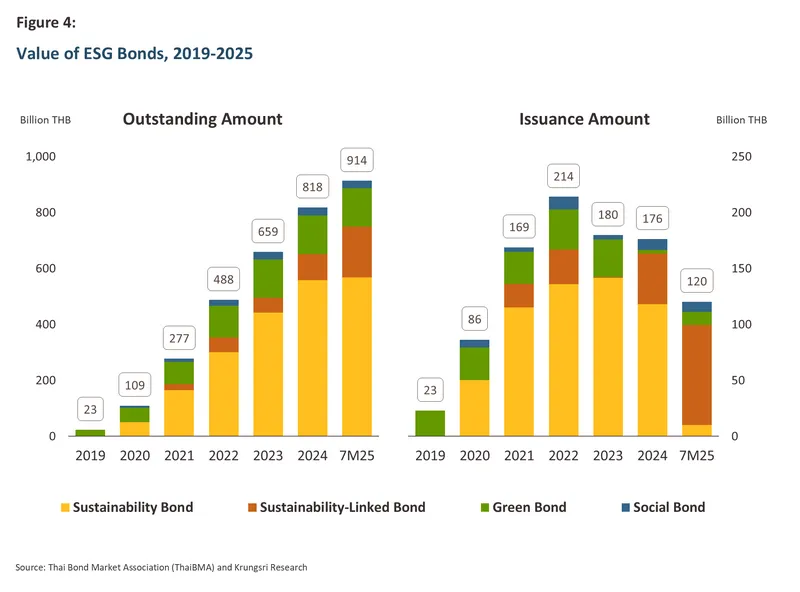

The sustainable finance market in Thailand has shown continuous growth. As of July 31, 2025, the outstanding value of ESG bonds4/ stood at THB 910 billion, nearly 40 times higher than in 2019 (Figure 4)5/, with more than half of this amount raised by the energy and transport sectors. However, ESG bonds still account for only 5.3% of total bonds6/, highlighting substantial room for further expansion, with the Taxonomy expected to play a key role in driving sustainable finance. This is reflected by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) waiving registration fees for Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) aligned with the Thailand or ASEAN Taxonomy from June 1, 2025, to May 31, 20287/, which enhances the appeal of these financial instruments.

3. Thailand is equipped with a tool to drive the green economy and advance national sustainability goals.

Government agencies can design climate change regulations and policies based on the technical criteria of the Taxonomy. This tool also provides guidance for directing investments toward green businesses and low-carbon technologies. Together, these will help support the achievement of national sustainability targets, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30–40% from business-as-usual (BAU) levels by 2030, achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, and reaching net-zero emissions by 2065.

Impacts and challenges

The Thailand Taxonomy creates impacts and challenges for various sectors in two main areas: (1) data collection and reporting, and (2) the transition toward sustainability, as outlined below.

1. Business data collection and reporting under the Taxonomy

Although adoption of the Thailand Taxonomy is currently voluntary, businesses may face peer pressure from other industry players to disclose information categorized by green, amber, and red activities. This includes reporting proportions of revenues, capital expenditure (CapEx), operating expenditure (OpEx), supplier shares, bank lending portfolios, and investment fund allocations. Furthermore, businesses may be subject to mandatory reporting obligations in the future, similar to those required under the EU Taxonomy.

In addition to financial reporting, businesses also face challenges in collecting technical environmental data required to demonstrate compliance with the Thailand Taxonomy. Such data include greenhouse gas emissions8/, the percentage of energy efficiency improvements, water savings, and information on compliance with social and labor standards. However, most Thai companies are still developing their carbon measurement capabilities. Among companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand, only about half currently disclose carbon footprint data. Disclosure is most common in the energy, transport, and agribusiness sectors, while smaller firms report at roughly half the rate of larger firms.9/ As a result, the Taxonomy may exert pressure on businesses to invest in sustainability data collection processes, requiring financial resources and skilled personnel, which disproportionately affects smaller enterprises.

2. The business transition toward sustainability

Thai businesses are increasingly under pressure to align their operations with the high environmental and social standards set by the Taxonomy. This transition is expected to raise costs in two main areas: (1) investment in green technologies such as renewable energy, hydraulic cement, green steel, and low-emission rice farming, which remain more expensive than conventional, carbon-intensive alternatives—for example, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is currently priced at two to three times the cost of traditional jet fuel; and (2) obtaining sustainability certifications, which serve as proof of compliance with the Taxonomy criteria, particularly for companies in real estate and agriculture where certification provides a viable pathway to meeting the Taxonomy’s standards.

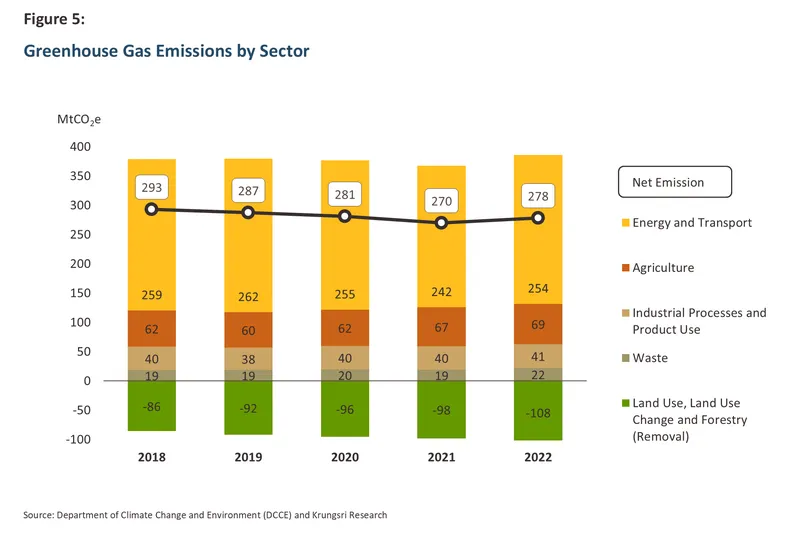

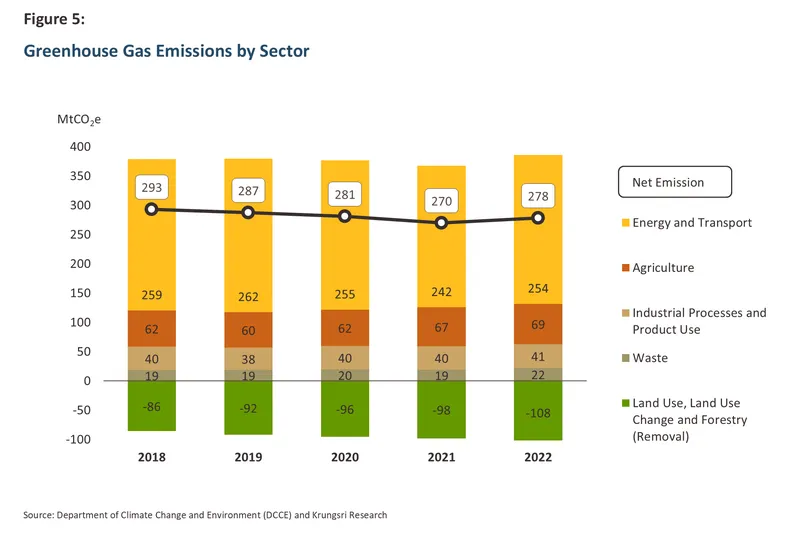

While the transition will initially be gradual, urgency will mount as Thailand approaches its climate commitments. In 2022, Thailand’s net greenhouse gas emissions—after accounting for forest carbon absorption—stood at 278 million tons of CO₂ equivalent (MtCO₂e).10/ This figure remains far from net zero and emissions are expected to continue rising in the post-COVID recovery (Figure 5).

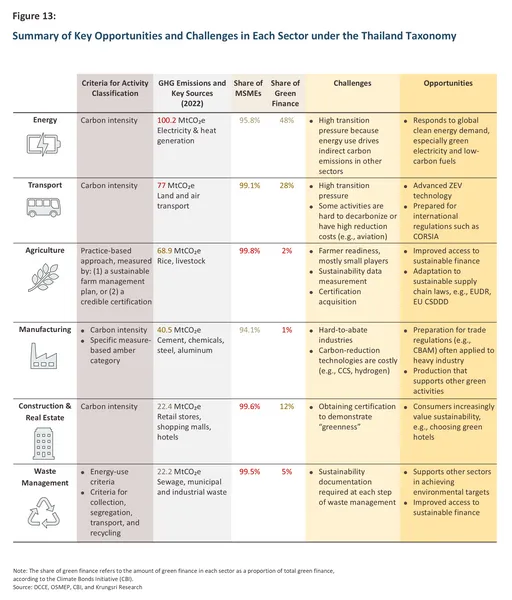

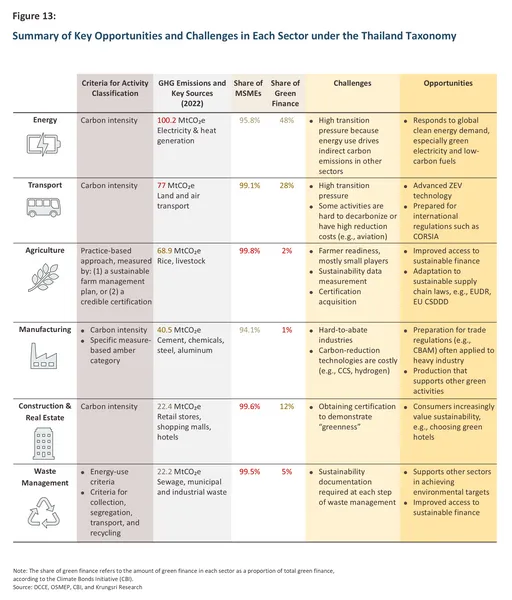

At the sectoral level, each industry under the Taxonomy faces distinct transition challenges. Transport and industrial sectors continue to record rising emissions, whereas the energy sector shows a downward trend thanks to its growing reliance on renewables. Nonetheless, energy remains the highest-emitting sector and thus faces sustained pressure to decarbonize further. Agriculture poses another major challenge. It accounts for 17.9% of emissions—only behind energy and transport—and is characterized by a dominance of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which make up as much as 99.8% of the sector.11/

Ultimately, firms in sectors unable to transition (red) or only able to transition slowly (dark amber/brown) may find it difficult to remain competitive. Not only could access to finance become more constrained, but buyers and consumers are also likely to shift toward more sustainable alternatives.

Sectoral Deep Dive: Opportunities and Challenges under the Thailand Taxonomy

Because the classification of activities varies across economic sectors—depending on factors such as their significance in greenhouse gas emissions and the availability of green technologies—businesses under the Thailand Taxonomy face different opportunities and challenges. The sector-specific details are as follows:

Energy

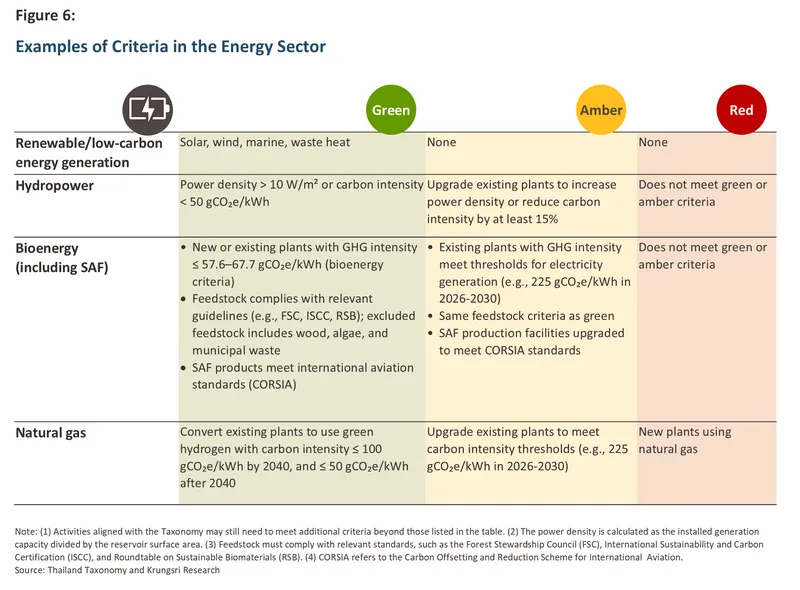

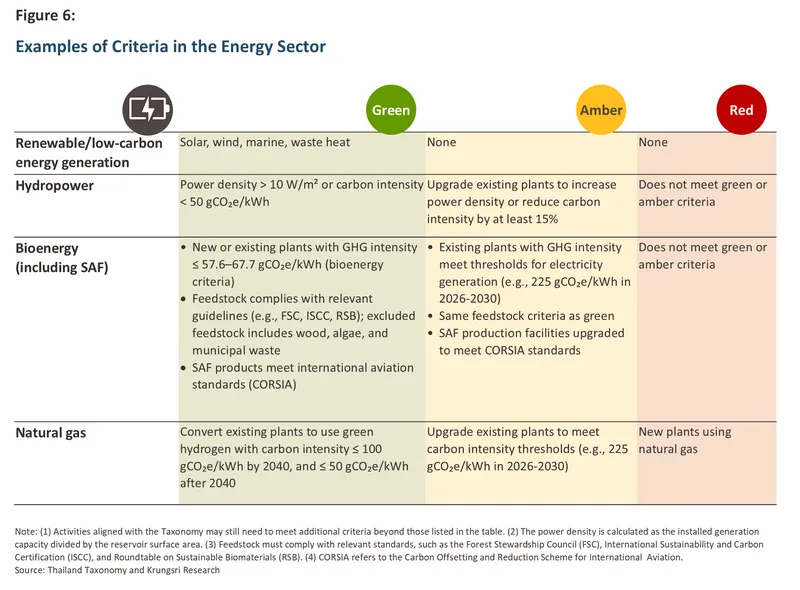

The energy sector is the highest-emitting sector in Thailand, with electricity and heat production alone accounting for 21.4% of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Accordingly, most activities under the Taxonomy focus on energy generation from various sources, as well as related activities such as storage, transmission, and distribution. A key criterion for classifying energy-sector activities is the greenhouse gas intensity per unit of energy produced. Green activities include electricity generation from solar, wind, marine, and waste heat. For natural gas, biomass, bioenergy, hydropower, and combined-heat-and-power plants, green classification requires meeting emission thresholds and/or other criteria, such as the feedstock used for bioenergy or the power density of hydropower plants.12/ Amber criteria generally require upgrading existing power plants to reduce carbon emissions in line with the net-zero transition pathway. Finally, activities involving fossil fuels, such as coal and oil, are classified as red.

The Taxonomy underscores that the energy sector must lead the transition to net zero, as reliance on carbon-intensive energy increases the indirect emissions of other sectors. This has driven a clear shift from fossil fuels toward renewable energy over recent years. Comparing commercial bank lending data from 2019 to 202413/ reveals a significant contraction in outstanding loans: coal mining fell by -41.5% (averaging -10.2% per year), and crude oil and natural gas extraction declined by -74.3% (-23.8% per year), reflecting the banking sector’s continued reduction of financial support for fossil fuels.

At the same time, energy companies demonstrate strong sustainability awareness, evidenced by their dominant share in the sustainable bond market—accounting for roughly 30% of total outstanding bonds—primarily from large players such as Global Power Synergy PCL (GPSC), Ratch Group PCL, and BCPG PCL. The Taxonomy not only pressures these businesses to accelerate their transition but also facilitates access to sustainable finance, particularly for renewable energy ventures that are poised for high growth amid rising global clean energy demand and are key targets for banking sector support. Nevertheless, renewable energy projects must comply with the Taxonomy’s comprehensive environmental criteria, including noise control for wind turbines and designing solar panels and other renewable energy systems for durability, ease of maintenance, and recyclability according to international standards.

Transport

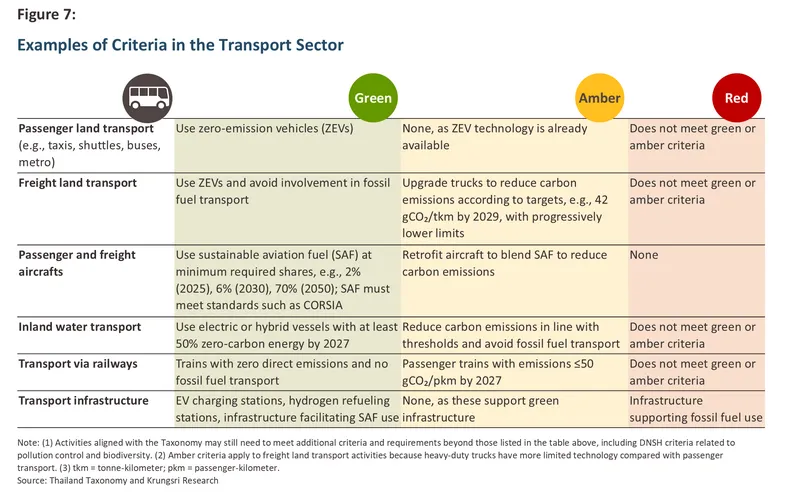

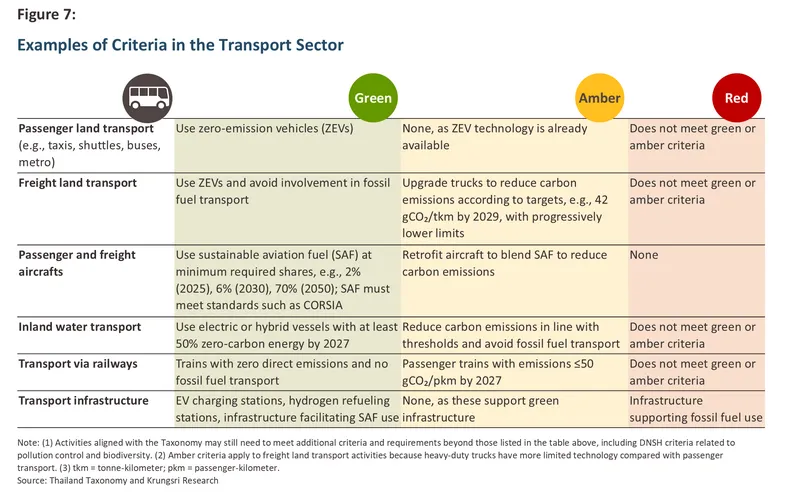

The transport sector accounts for about one-fifth of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions, making it the second-largest emitter after the energy sector. Accordingly, the Taxonomy applies carbon emission criteria and considers the availability of low-carbon technologies, which vary across different modes of transport. In general, green activities require the use of zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), such as battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and hydrogen-powered vehicles14/, or the use of low-carbon fuels, such as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), while also prohibiting activities that support fossil fuel use. Amber activities typically set annual maximum carbon emission limits, which gradually decrease to zero by 2040 (Sunset Date) (Figure 7).

Within the transport sector, land transport businesses—such as passenger services, public transit, and freight—are expected to be most affected by the Thailand Taxonomy, as they collectively account for more than 96% of transport-related carbon emissions. This segment is also where low-carbon vehicle technologies have advanced the furthest, compelling businesses to transition toward ZEVs to remain aligned with the Taxonomy. The next most affected subsector is aviation, which ranks second in carbon emissions. Airlines are therefore encouraged to increase the use of SAF, even though its cost remains higher than conventional jet fuel. Nonetheless, this pressure may facilitate compliance with international aviation requirements such as CORSIA15/, which aims to reduce global aviation emissions. At the same time, businesses across various industries will find opportunities to invest in infrastructure that supports low-carbon transportation—spanning road, water, air, and rail.

In terms of sustainable finance activity, the transport sector has demonstrated significant momentum, ranking second only to the energy sector in sustainable bond issuance. Leading examples include BTS Group Holdings PCL and Bangkok Expressway and Metro PCL (BEM), both of which have leveraged the Taxonomy to access financing. For instance, BEM has applied the Taxonomy framework in issuing bonds and securing loans for the development of environmentally friendly transport systems, totaling more than THB 34 billion during 2021-2024.16/

Agriculture

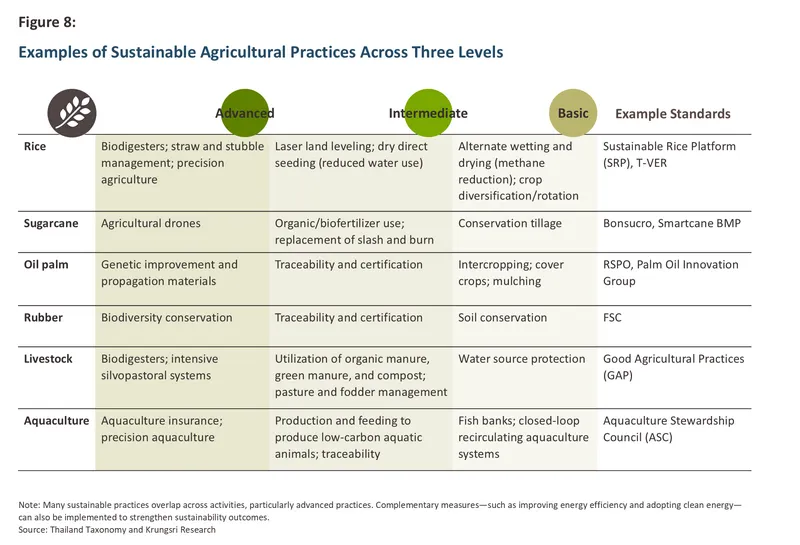

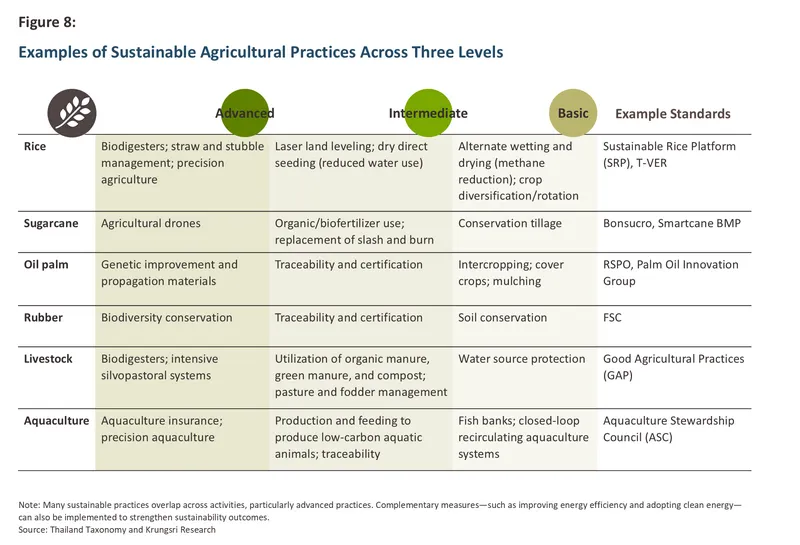

Unlike other sectors, the classification of agricultural activities under the Thailand Taxonomy does not employ the traffic-light system. This is largely due to challenges in defining technical screening criteria—for example, measuring carbon emissions at the farm level—stemming from limitations in data availability and completeness. Instead, the Taxonomy applies a practice-based approach to assess sustainable agriculture. Currently, it covers eight subsectors: rice, sugarcane, oil palm, rubber, cassava, other crops, livestock, and aquaculture. For each subsector, sustainable practices are categorized into three levels: basic, intermediate, and advanced.17/ Farmers or project developers are required to adopt at least two practices, of which at least one must be intermediate or advanced. Projects may then proceed through either of two pathways:

- Integrated Farm Management Plan (IFMP): A structured plan that outlines objectives, the farm’s current status, and activities to achieve sustainability based on the chosen practices.

- Certification by recognized standards: Attaining credible international or national certifications, such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) for rubber, or the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Program (T-VER) methodology for rice cultivation. In such cases, an IFMP is not required.

Among agricultural activities, rice cultivation generates the highest greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for more than half of the sector’s total, and will thus face the strongest pressure under the Taxonomy. Key areas of focus include reducing methane from rice paddies and curbing carbon emissions from stubble burning. Other major crops such as sugarcane and cassava also contribute emissions through tillage and fertilizer use. In contrast, rubber, oil palm, and aquaculture emphasize traceability as intermediate sustainable practices, which may help businesses prepare for emerging EU’s supply chain due diligence regulations such as the EUDR and CSDDD.18/ Meanwhile, the livestock sector will be significantly affected, ranking second only to rice cultivation in terms of emissions, with the primary sources being enteric fermentation and manure management.

So far, the agribusiness sector has had limited access to sustainable finance compared to other sectors. Notable participants include Thai Foods Group PCL (pork and poultry) and Thai Union Group PCL (processed seafood), both of which have raised funds through sustainable bonds. In addition, Thai Union Group secured over THB 5 billion in “Blue Loans” from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and commercial banks to support sustainable shrimp farming aligned with the Thailand Taxonomy.19/

Finally, the Taxonomy also incorporates forestry activities, including sustainable forest management, afforestation, and conservation, with the core aim of enhancing carbon sinks and protecting biodiversity. Financial support for forestry has been rising, as reflected in a 68.7% increase in forestry and logging loans in 2024 compared to 2019. However, access to finance may remain challenging, as alignment with the Taxonomy requires certification in sustainable forest management from either international or domestic standards.20/

Manufacturing

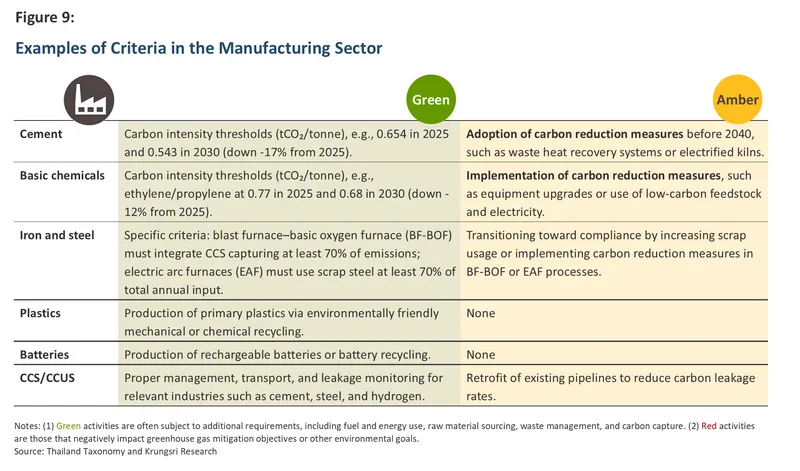

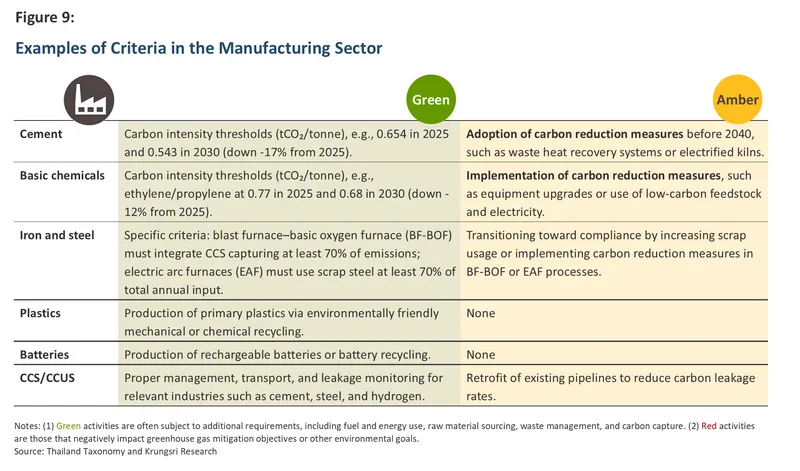

The Thailand Taxonomy classifies manufacturing activities into five groups:

-

Hard-to-abate industries such as cement, chemicals, steel, aluminum, and hydrogen. Green criteria for these industries are typically based on carbon intensity, measured as carbon emissions (tCO₂e) per unit of production (tonne). Given the challenges businesses face in meeting these thresholds, a specific measure-based amber category is included, allowing firms to adopt targeted carbon-reduction measures alongside a credible transition plan toward net zero.

-

Transitional activities that will be phased out by 2050, such as the production of plastics in primary form.

-

Enabling activities that support green industries, including the production of batteries, renewable energy components (solar panels, wind turbine blades), and energy-efficient building materials. These activities fall only under the green category.

-

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) / Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) covering activities for capturing, transporting, utilizing, and storing carbon emissions.

-

Auxiliary transitional activities applicable to other manufacturing subsectors such as textiles, food, and furniture. Green criteria are benchmarked against international standards such as the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi), while amber criteria require improvements in energy efficiency or increased use of renewable energy.

The sectors under the greatest pressure from the Taxonomy are cement, chemicals, steel, and aluminum, which together represent the largest sources of industrial carbon emissions in Thailand.

Cement and chemical production alone account for 40% and 29% of total industrial emissions, respectively. These industries therefore face stringent carbon reduction requirements. However, businesses may gradually transition by investing in carbon reduction measures that qualify as amber activities. Such capital expenditures (CapEx) can be reported as Taxonomy-aligned and may improve access to sustainable finance. In addition, these efforts help industries prepare for compliance with the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and similar measures in other jurisdictions. Conversely,

manufacturing activities that enable the green transition—such as renewable energy components or energy-efficient building materials—

stand to benefit from the Taxonomy. They are expected to gain from both greater financing opportunities and rising demand for green technologies across energy, transport, construction, and building sectors.

Construction and real estate

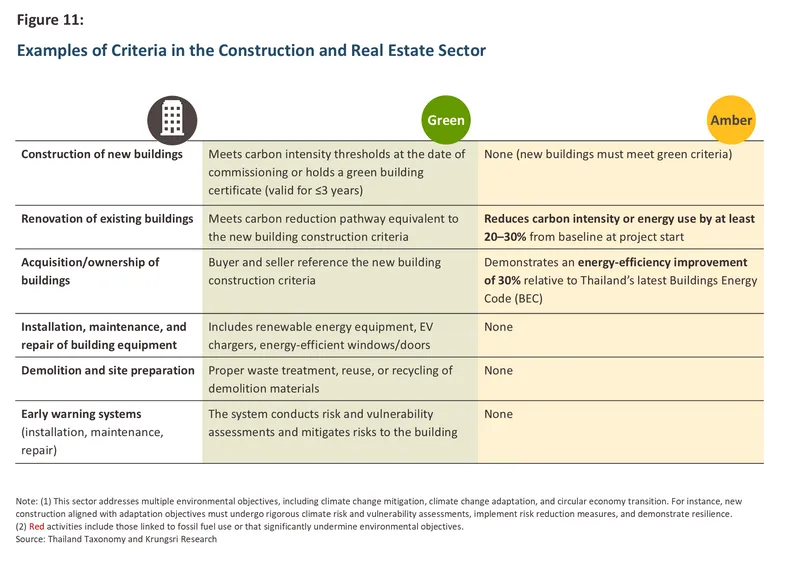

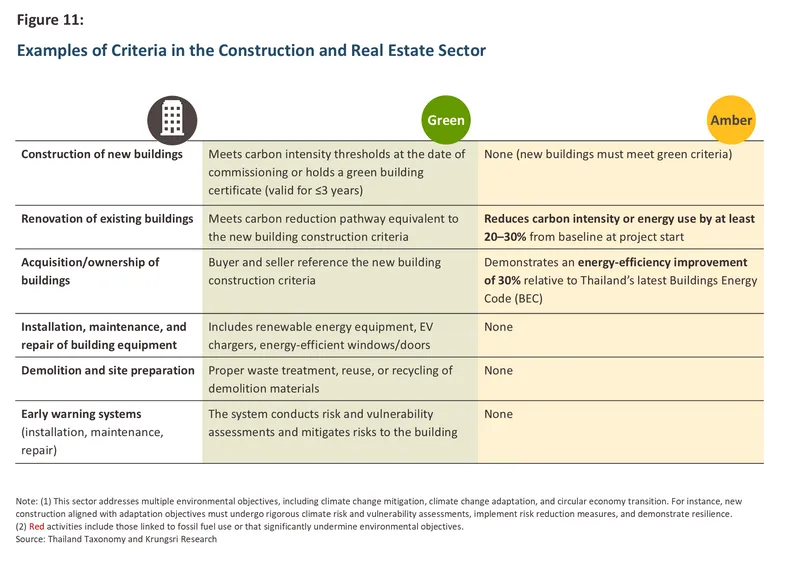

The Thailand Taxonomy classifies activities related primarily to greenhouse gas emissions from building operations, with a particular focus on energy consumption throughout a building’s life cycle.21/ The scope covers residential buildings (e.g., houses and condominiums) and commercial buildings (e.g., offices, retail stores, and hotels), including renovation or demolition. However, it currently excludes industrial buildings, construction materials, and construction processes. Green criteria for this sector follow two main approaches:

-

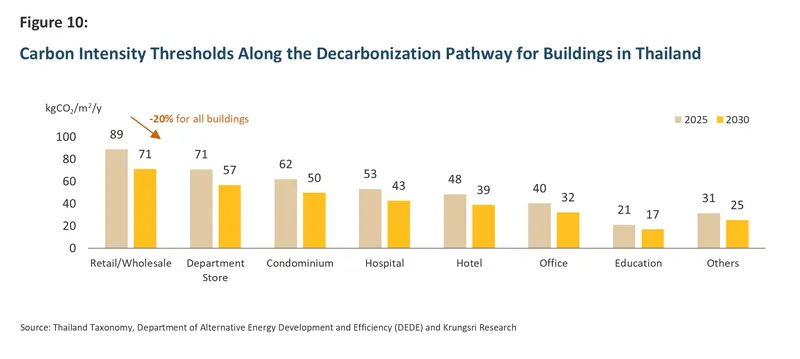

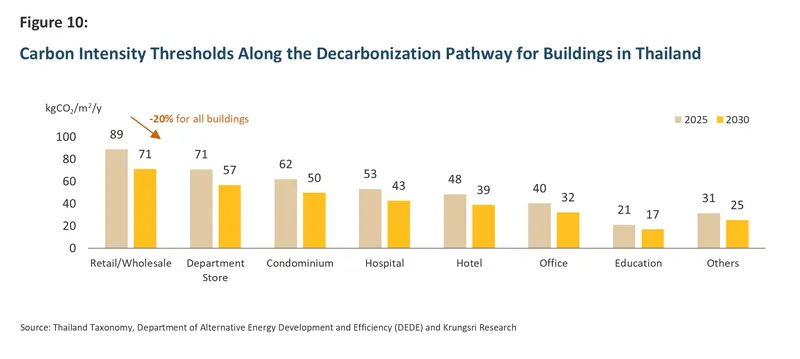

Decarbonization pathway for buildings in Thailand: Newly constructed buildings must comply with annual carbon intensity thresholds. For example, in 2025, retail and wholesale commercial buildings—considered the highest emitters—must not exceed 88.6 kgCO2/m2/year, followed by department stores, condominiums, hospitals, hotels, and offices (Figure 10). These thresholds will gradually decline each year, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050.

-

Sustainability certification for buildings: Where direct carbon emissions data are unavailable, internationally or nationally recognized green building certifications may be used to demonstrate compliance. Examples include Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Thai’s Rating of Energy and Environmental Sustainability (TREES), the Building Environmental Assessment Method (BEAM), and Thailand’s sustainable energy and environmental label (Building No.5). Additional requirements also apply, such as certification levels, validity periods, and building types.

As a result, new construction activities must meet green-level criteria only, whereas building renovation and acquisition/ownership may qualify under amber-level criteria, provided carbon intensity or energy use is reduced (Figure 11). This creates strong pressure on high-emission sectors—such as retail/wholesale, condominiums, hospitals, and hotels—to lower operational emissions and/or pursue green building certifications to improve access to sustainable finance. Indeed, major players in the hotel and retail sectors have already tapped into sustainable financing, such as Minor International PCL, Central Pattana PCL, and Central Plaza Hotel PCL, which have issued sustainable bonds.

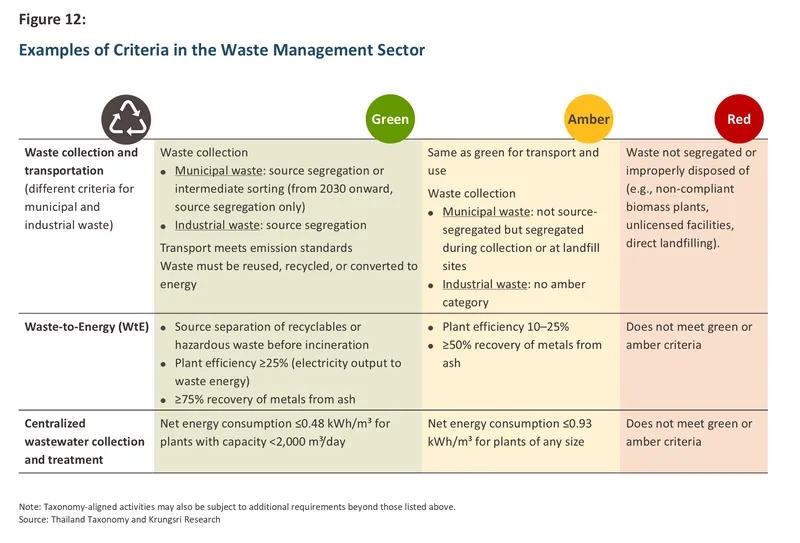

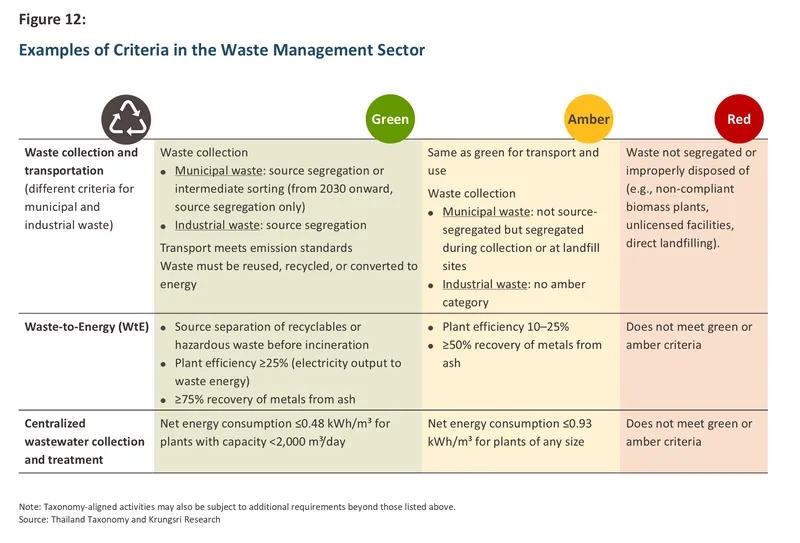

Waste management

The Thailand Taxonomy covers waste-related activities such as organic waste treatment, waste collection and transportation, waste-to-energy (WtE), sorting and recycling, and hazardous waste disposal. These activities primarily support objectives related to the circular economy, pollution prevention, and greenhouse gas reduction. Within this sector, most emissions arise from wastewater management (53.2%) and solid waste management (45.1%). However, unlike other sectors, the waste sector does not have its own GHG reduction pathway. Instead, it aims to support other sectors in achieving their emission reduction targets. Accordingly, technical screening criteria emphasize waste minimization, segregation, reuse, and recycling, drawing heavily on the EU and Singapore taxonomies (Figure 12).

Waste management businesses are expected to benefit significantly from the Taxonomy, as they play a vital role in enabling other sectors—such as agriculture, industry, and services—to achieve environmental goals. However, compliance will require stricter standards and documentation, including environmental licenses and permits, standard operating procedures (SOPs), internal and external audit reports, and water quality test results. This will also strengthen access to sustainable finance, which remains relatively limited in this sector compared with others.

Krungsri Research View: Preparing Businesses for Thailand’s Green Investment Standard

The Thailand Taxonomy functions as a strategic guide or “common language” that clarifies which activities qualify as environmentally sustainable. By providing this shared framework, it enables businesses across all sectors to move in a coordinated direction toward collective sustainability goals. While adoption is currently voluntary in Thailand, experience from the EU suggests it could become mandatory in the near future. Moreover, early adopters create a ripple effect, incentivizing other firms to align their operations—an economic externality that reinforces market-wide sustainability. To navigate this evolving landscape, businesses should act as follows:

-

Begin disclosing performance in alignment with the Taxonomy, even before it becomes legally required. This can include the proportion of revenue, capital expenditures (CapEx), and operational expenditures (OpEx) aligned with the Taxonomy. Accurate collection of environmental and social data is critical, as it forms the basis for benchmarking against Taxonomy criteria. While implementing measurement and reporting systems may involve short-term costs, early adoption provides a competitive advantage in transparency and credibility.

-

Accelerate the transition toward low-carbon and sustainable operations, particularly in high-emission sectors such as electricity, aviation, cement, chemicals, rice, and livestock, which face increasing pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Aligning with the Taxonomy prepares firms for emerging Thai regulations, such as the Climate Change Act22/ and Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), as well as international frameworks like CBAM and CORSIA. Businesses must also address broader sustainability dimensions, including social responsibility, human rights, and labor practices, to meet both Thailand Taxonomy and global standards.

-

Leverage the Taxonomy to access sustainable finance. In addition to helping businesses reduce regulatory risks and avoid penalties (the “stick”), complying with the Taxonomy also provides incentives (the “carrot”) for sustainable investment. This includes improved access to financing through green bonds, capital markets, loans, or government-backed climate funds. Furthermore, sustainable businesses may benefit from lower financing costs, as some investors are willing to accept lower returns on green debt instruments—known as the “greenium.”23/ Because the Taxonomy evaluates activities rather than entire companies, firms have flexibility in how they qualify. For example, a hotel can meet transport-sector criteria by converting its operational fleet to EVs or installing EV charging stations, while simultaneously meeting criteria for real estates by improving energy efficiency or obtaining green building certification.

-

Monitor changes to the Taxonomy, as it is a living document that is regularly revised. Future updates may adjust technical criteria and expand the scope of economic activities, taking into account progress toward net zero targets, advancements in green technologies, and alignment with international standards (interoperability). Staying informed thus ensures that Thai businesses remain attractive to global green investors, partners, and customers.

In conclusion, the Thailand Taxonomy is more than a technical standard—it serves as a catalyst for investment in green activities and low-carbon technologies. The financial and banking sector emerges as a pivotal stakeholder in this sustainability landscape, both by leveraging the framework to identify businesses with high potential for sustainable growth and by channeling capital into projects that generate tangible environmental and social benefits.

References

Bank of Thailand. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Agriculture Sector [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/taxonomy/03_TH_Thailand_Taxonomy-Agriculture_Sector.pdf

Bank of Thailand. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Construction and Real Estate Sector [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/taxonomy/04_TH_Construction_and_Real_Estate_sector.pdf

Bank of Thailand. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Energy Sector [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/taxonomy/07_TH_Thailand_Taxonomy-Energy.pdf

Bank of Thailand. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Introduction [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/taxonomy/01_TH_Thailand_Taxonomy-Introduction.pdf

Bank of Thailand. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Transportation Sector [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/taxonomy/08_TH_Thailand_Taxonomy-Transportation_sector.pdf

Bank of Thailand. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Waste Management Sector [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/taxonomy/06_TH_Thailand_Taxonomy-Waste_Management_Sector.pdf

Bloomberg. (2023). The importance of global cooperation on green taxonomies. Retrieved February 15, 2025, from https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/insights/markets/the-importance-of-global-cooperation-on-green-taxonomies/

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2023). ASEAN Sustainable Finance: State of the Market 2022 [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.climatebonds.net/data-insights/publications/asean-sustainable-finance-state-market-2022

Department of Climate Change and Environment. (2025). Thailand Taxonomy – Webinar: A Deep Dive into the Transportation Sector [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.dcce.go.th/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Webinar_ThailandTaxonomy_Transportation.pdf

Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research. (2023). Sustainable Bonds: What Types Are There and What Is Greenium? Retrieved from Sustainable Bonds: What Types Are There and What Is Greenium?

World Business Council for Sustainable Development, & Deloitte. (2024). Harnessing taxonomies to help deliver sustainable development [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.wbcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Harnessing-taxonomies-to-help-deliver-sustainable-development-WBCSD-and-Deloitte.pdf

1/ The Thailand Taxonomy working group comprises the Bank of Thailand, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET), the Department of Climate Change and Environment (DCCE), as well as other relevant government agencies, private sector representatives, and financial institutions.

2/ Major economic activities such as the service sector, which accounts for more than half of Thailand’s GDP, are not included in the Taxonomy, as they do not significantly contribute to climate change.

3/ Source: B.Grimm Power PCL, Annual Report 2024, 20250326-bgrim-one-report-2024-th-v04 and https://www.dcce.go.th/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Panel-2_B.Grimm-Khun-Solaya.pdf

4/ ESG Bonds include (1) Green, Social, and Sustainability Bonds, which are issued to raise funds for projects or activities related to environmental conservation and/or social development, and (2) Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs), which contain terms that adjust interest rates and/or impose issuer obligations based on sustainability performance measured against specific indicators and targets (Source: Securities and Exchange Commission, SustainableFinance).

5/ Sustainability Bonds account for the largest share at 62.2%, while Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) have been increasingly significant and were the most issued bonds during the first seven months of 2025.

6/ Calculated as the outstanding value of ESG Bonds divided by the total outstanding value of Government Debt Securities, Corporate Bonds, and Foreign Bonds (Source: Thai BMA, Green, Social & Sustainability Bond)

7/ Source: Manager Online, “SEC Waives Registration Fees for Sustainable Bonds and Digital Tokens – Soft Power Impact, effective 1 June 2025–31 May 2028.”

8/ Generally, the greenhouse gas emission criteria under the Thailand Taxonomy cover only Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, while certain activities—such as bioenergy and hydrogen production—may require a lifecycle carbon assessment that includes Scope 3 emissions.

9/ For further reading, see Krungsri Research’s article Carbon Footprint: Critical Data in the Global Boiling Era

10/ Source: Department of Climate Change and Environment, Thailand GHG Platform

11/ Source: Office of Small and Medium Enterprises Promotion (OSMEP), Number of Small and Medium Enterprises – SME Data Catalog

12/ The power density of a hydropower plant is calculated as the installed generation capacity divided by the surface area of its reservoir.

13/ Bank lending data from the Bank of Thailand

14/ For further reading, see Krungsri Research’s article Hydrogen-Powered Vehicles: A Clean Energy Alternative for Greener Future

15/ CORSIA refers to the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation. For further detail, see Krungsri Research’s article CORSIA Paving the Way for Flying Net Zero

16/ Source: BEM, The Amalgamation Bangkok Expressway and Metro Plc. (BEM)

17/ Farmers or project developers are also required to provide a compliance statement demonstrating adherence to all relevant Thai laws and regulations governing farm operations.

18/ The EU sustainable supply chain regulations include the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

19/ Source: SD Thailand, Establishing Sustainable Finance Standards: ADB Approves THB 5 Billion Blue Loan for Thai Union to Advance Sustainable Shrimp Farming.

20/ Examples of relevant certification standards include international frameworks such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC). Thai standards include the Thailand Forest Certification Council (TFCC) and the Premium T-VER program for forest-based carbon credits.

21/ Other building-related emissions—such as embodied emissions from construction materials (e.g., cement, steel), as well as energy use and transport during construction—are generally smaller in scale compared to operational emissions over the building life cycle. These are covered separately under other sectors, such as energy and manufacturing.

22/ Currently, the act is under consideration by the Secretariat of the Cabinet before being reviewed by the Cabinet and the Office of the Council of State within 50 days. It will then proceed to the parliamentary process and is expected to be approved by Parliament by 2026 (Source: Thansettakij, “Accelerating the Enactment of the Climate Change Act: Unlocking Three Mechanisms to Combat Global Carbon”).

23/ Source: Darika Deesamoh & Swisa Pongpetch. (2023). “Sustainable Bonds: What Types Are There and What Is Greenium?”