Social Commerce: The New Wave of E-commerce

Online shopping, or e-commerce, has undergone an explosion in demand worldwide, Thailand included. Although the e-commerce market has been expanding rapidly for many years, the outbreak of Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdowns and stay-at-home orders that many countries issued during 2020 and 2021 forced consumers to replace trips to bricks-and-mortar shops with online alternatives. This then vastly accelerated the integration of e-commerce into consumers’ daily lives. Alongside the growth in e-commerce, over the past decade, the world has seen an equally transformative expansion in social media, and these two trends have now converged in the phenomenon of ‘social commerce’, that is, retailing through social media.

E-commerce has developed very rapidly in Thailand, and the country’s Electronic Transactions Development Agency (ETDA) estimates that in 2019, the entire national e-commerce market had a value in excess of THB 4 trillion, with just the wholesale and retail component of this generating receipts of THB 1.3 trillion. In addition to sales through e-marketplaces, social commerce has figured prominently in the expansion of the Thai online retail environment, and Krungsri Research believes that in 2020, this accounted for 28% of the entire wholesale and retail e-commerce space. Globally, it is estimated that in 2020, social commerce had a value of USD 240-470 billion (or THB 7.2-14.3 trillion), with the Asia-Pacific region the standout leader.

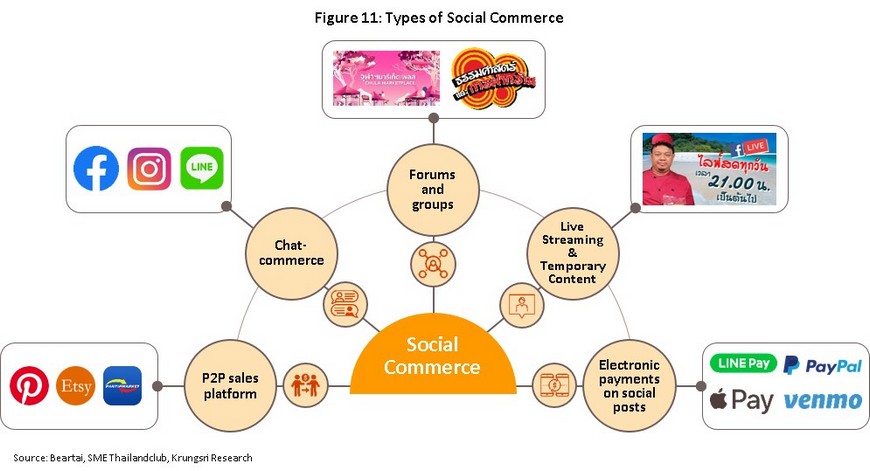

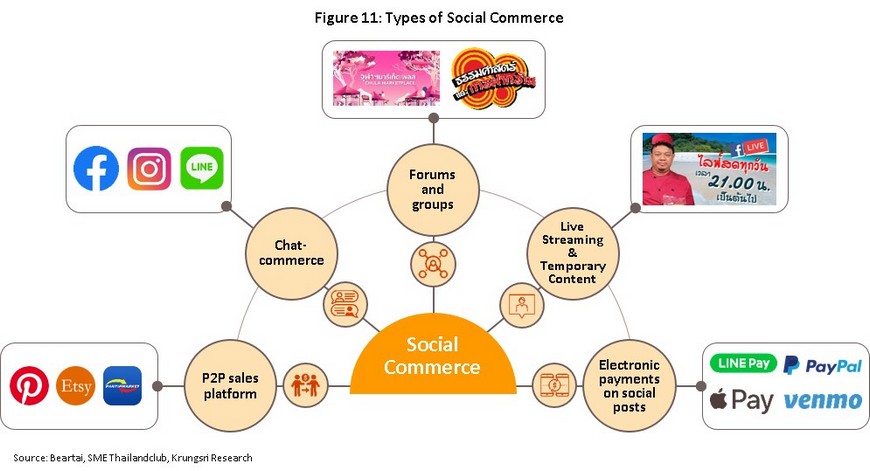

For greater analytic clarity, the general category of social commerce can be divided in to the five sub-groups of: (i) peer-to-peer sales platforms, or community-based marketplaces; (ii) sales made via chat apps, also called ‘conversational commerce’ or ‘chat commerce’; (iii) sales made through forums and social media groups; (iv) live streams broadcast by sellers or other types of temporary content; (v) electronic payments made through social media posts. In the Thai context, social commerce is most often encountered in the second, third and fourth of these forms.

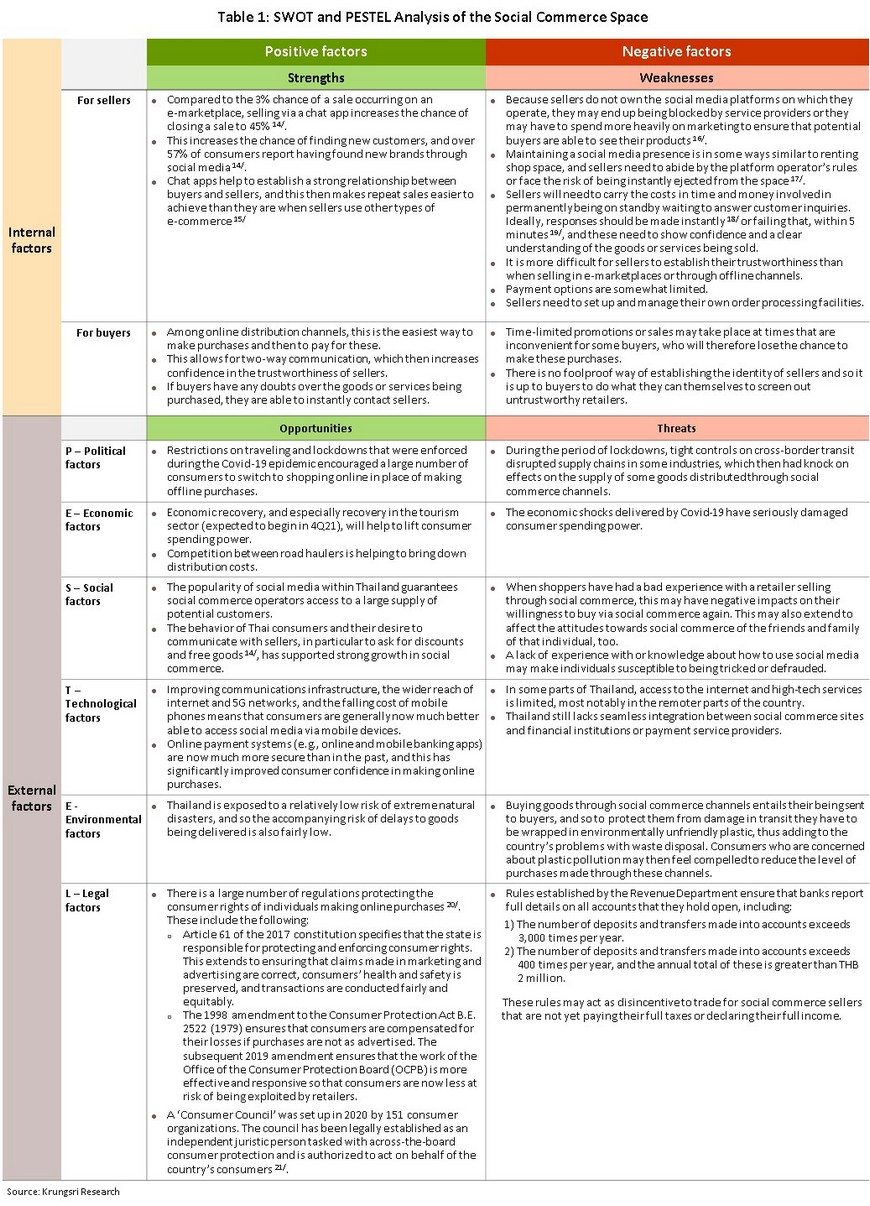

However, because the surge in interest in social commerce has been so closely tied to the Covid-19 crisis, observers may question how the segment will fare once the epidemic has been brought under control and consumers and the economy have been able to settle into whatever form the ‘new normal’ will take. Krungsri Research has thus carried out SWOT and PESTEL analyses, and these reveal that although social commerce will continue to be buoyed by a mix of its internal strengths and favorable external circumstances, the segment is also exposed to both its own weaknesses and challenges from outside that will need to be overcome. Not least among these are issues related to the safety of online shopping and payment systems, and online sellers and financial institutions will need to give these issues careful consideration.

To better understand consumer behavior with regard to social commerce services, Krungsri Research carried out an online survey of the opinions of 522 individuals between March 29 – May 1, 2021. The results show that Facebook was the most popular social commerce channel. The majority of purchases fell into one of the three categories of clothing, food and drinks, and cosmetics, perfume, and beauty and skin products. Most purchases had a value of THB 100-1,000 and generally this was paid for through a mobile banking app, especially if that app was connected to the consumer’s primary account for making payments and transfer. When asked, survey respondents said that they would like payment service providers to partner with sellers to run joint promotional campaigns or to offer loyalty point programs that could be set against discounts or exchanged for gifts from the seller or the bank/payment provider. Respondents also stated that they would like payment to be seamless and fully integrated between the seller and the payment sides so that payments could be completely automated; taking account of this diversity of opinion will be an important step on the road to better meeting future consumer demand.

From e-commerce to social commerce

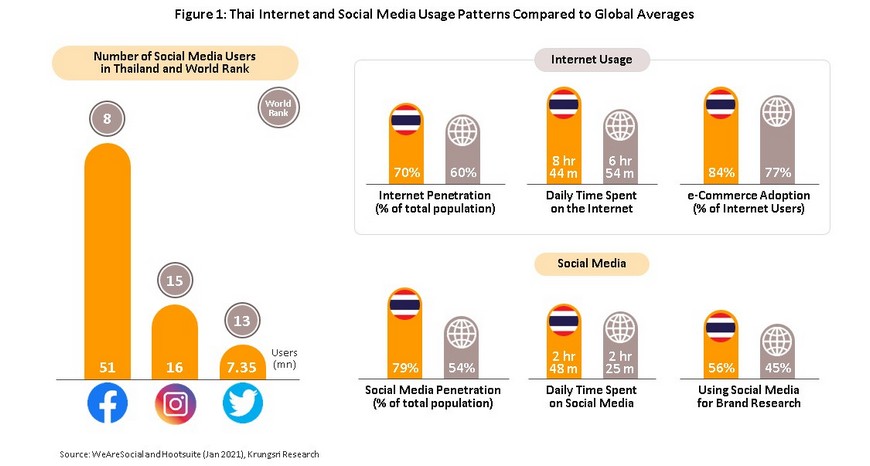

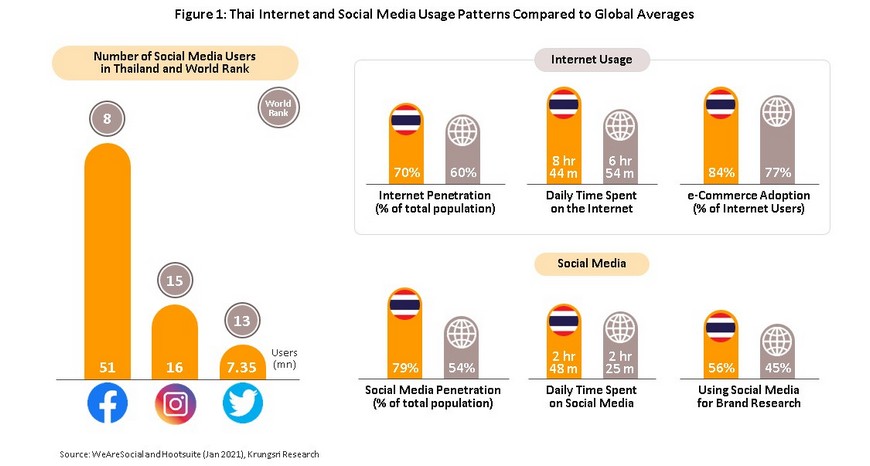

Almost no corner of the world has escaped the impacts arising from the emergence of the internet, and the effects of this have only been accelerated by the Covid-19 crisis. Indeed, as a result of the transformations witnessed over the past 18 months, the internet is now even more tightly woven into the fabric of consumers’ day-to-day lives worldwide, in Thailand just as much as in any other country. Thus, over the period 2013 to 2020, the number of Thais using the internet jumped 91.6% [1] from 26 million to 50 million. Alongside the rising total number of users, average daily usage rates have also climbed, and a 2020 report by the ETDA indicates that in the year, Thais spent an average of 11 hours and 25 minutes online every day. Thais are in fact now among the world’s most avid consumers of social media and the same report reveals that for Thai internet users, accessing social media services is their preferred online activity (95.3% of users report doing this). Data from WeAreSocial also shows that 51 million Thais have Facebook accounts, making Thailand the company’s 8th most important market, while there are also 16 million Thai users of Instagram (the image-based social media site and app), putting the country in 15th place in the global ranking. Moreover, in addition to raw penetration rates, Thais tend to be more engaged than average with these platforms, and so for example on Facebook, Thai users make an average of 8 comments per person per month, against a global average of just 5 (Figure 1).

The rising penetration and engagement rates for the Thai internet is naturally one factor that has encouraged the local success of e-commerce, interest in which has seen extremely high rates of growth over the past 5 years. The WeAreSocial report referenced above reveals that a full 84% of Thai internet users have bought goods online, higher than the global average of 77% and the 3rd highest rate in the world, beaten only by Indonesia and the UK. Here, ‘e-commerce purchase’ extends to encompass both those made on the major platforms or e-marketplaces [2], which in Thailand include Shopee, Lazada and JD Central, individual sellers’ own websites or apps, and sales made on social media platforms by both individual sellers and brands, or so-called ‘social commerce’. The latter is increasingly popular in Thailand, and sometimes takes the form of live streaming on social media.

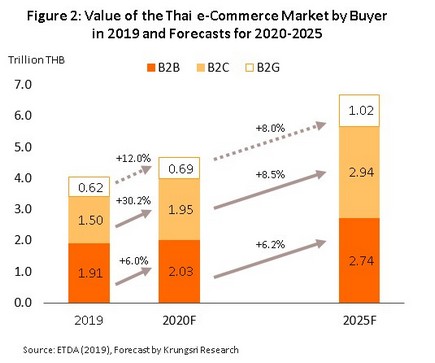

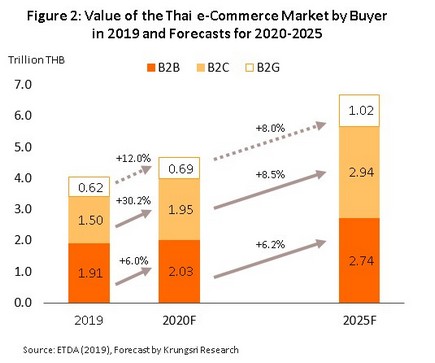

However, making an accurate assessment of the e-commerce sector is complicated by the fact that much activity takes place in the informal sector and as a result, valuations of the Thai e-commerce sector vary widely. Google, Bain and Temasek reports that in 2020, the market was worth around THB 270 billion, or USD 9 billion [3], whereas in 2019, the ETDA put a value of THB 4.03 trillion on the sector. Based on the latter figure, around half of all activity is comprised of business-to-business (B2B) sales, these having a value of THB 1.91 trillion, followed in importance by business-to-consumer sales (B2C), which generated income of around THB 1.5 trillion. With a value of just THB 0.62 trillion, or 15% of the entire market, business-to-government (B2G) sales come in in a more distant third place.

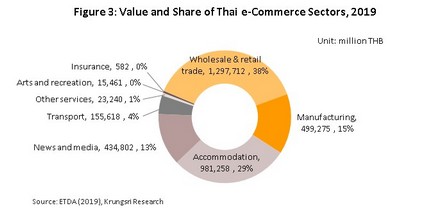

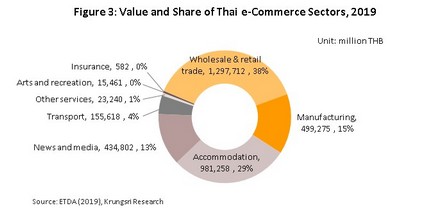

Exclusively private-sector e-commerce [4] (i.e., not including the B2G category) had a value of THB 3.4 trillion in 2019. Within this, the most important segment was wholesale and retail trade, which contributed 38.1% of the total, followed in order by hotels and accommodation (28.8%), manufacturing (14.7%), news and media (12.8%) and transport and distribution (4.6%) (Figure 3). Krungsri Research estimates that in 2020, the unusual circumstances of the Covid-19 outbreak pushed the combined value of the B2B and B2C segments to somewhere in the region of THB 4 trillion, and that over the next 5 years, receipts from the B2B and B2C markets will rise by a further 6.2% and 8.5% respectively.

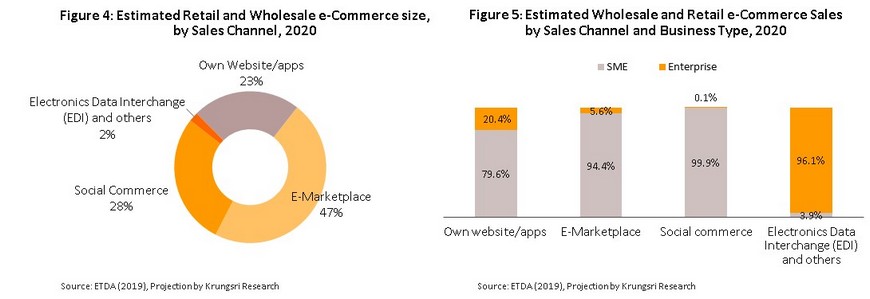

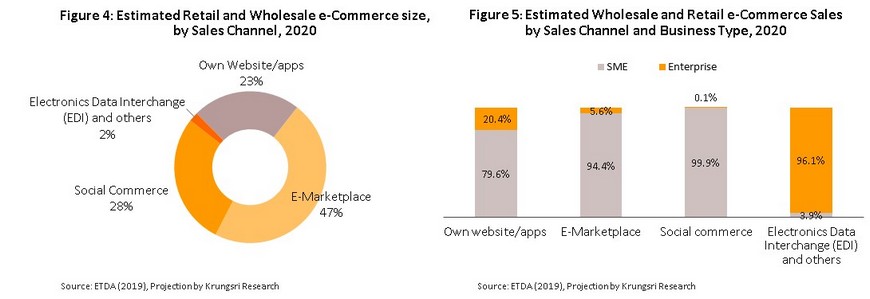

With a 2019 value of THB 1.3 trillion, the wholesale and retail segment is at the heart of the e-commerce sector, and within this market, e-marketplaces and social commerce are the two prominent channels; Krungsri Research’s analysis indicates that in 2020, these accounted for respectively 47% and 28% of wholesale and retail e-commerce (Figure 4). Moreover, these two channels are especially important for SME operators, and the role of SMEs in supporting these is such that sales by small and medium-sized enterprises are estimated to account for 94% of the value of goods distributed through e-marketplaces and a full 99.93% of the value of social commerce sales. This assessment is in line with the WWTH 2020 report [5] (Figure 5), which noted that smaller SME-sized brands benefit from sales through social commerce, while large brands are more dependent on e-marketplaces.

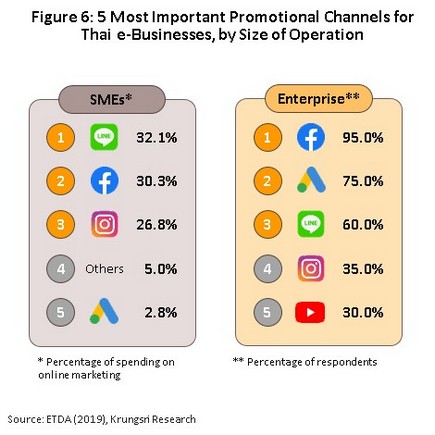

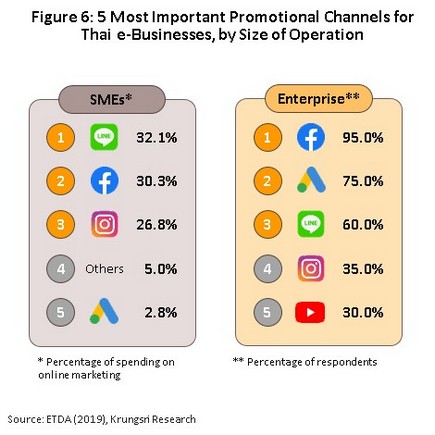

Although the mix and preferences differ according to business size, the communications channels used by both SMEs and enterprise-level operations for public relations and marketing are broadly similar. For these players, social media (most likely Facebook, Line or Instagram (Figure 6)) is the primary means of connecting with their current or potential customer base, and so within the e-commerce space, social media doubles as a channel for promotional activities and a place for making sales, these being two of the 4 marketing Ps [6]. For sellers, distributing through social media is also a good choice for those just starting out with online sales since this has the advantage of being easy to use, effective and rapid, as well as providing good practice for sellers before they move to distributing through other channels such as e-marketplaces, where the market is much bigger and competition correspondingly stiffer.

Although e-commerce began as one option for shoppers looking for greater ease and convenience, data on sales show that being active on e-commerce channels has grown into becoming much more of a necessity for distributors. As discussed above, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused a shift in consumer attitudes, which have now moved to a much greater preference for online shopping. A survey by the Office of the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) reveals that in January and February 2020 (i.e., at the very start of the Covid-19 crisis) purchases on the Shopee and Lazada platforms jumped by respectively 478.6% and 121.5%, with growth continuing through March and April, when the government restricted travel and instituted a nationwide lockdown as it tried to halt the spread of the pandemic.

Given this general preference for e-commerce in Thailand (the country is 3rd in the world rankings) and social media’s deep penetration rates (the country has a similarly high ranking for social media use), it was perhaps inevitable that interest in and uptake of social commerce has been so extensive. However, in addition to promising opportunities, these developments are also generating threats and challenges for both buyers and sellers, and these extend to include the banking sector, which plays a crucial role connecting these two sides of the e-commerce market through the banks’ payment systems. This then leads to the question of how banks should try to navigate through the evolution of social commerce during a period in which it is developing into a force as potent as any other part of the e-commerce mix.

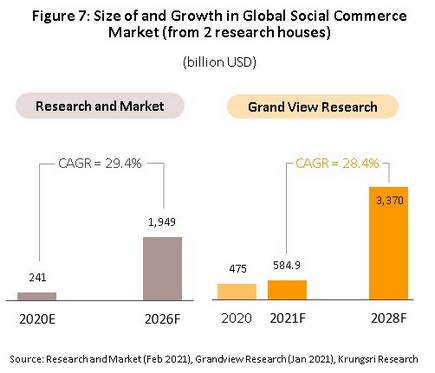

The place of social commerce in global markets

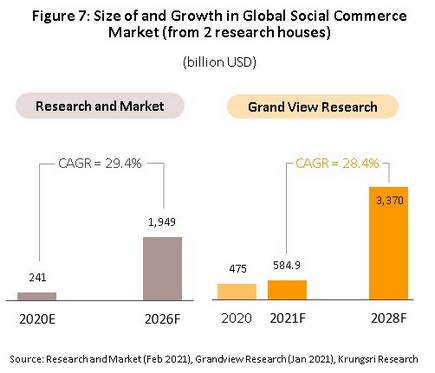

The popularity of social commerce seen in Thailand has been duplicated around the world, and in January 2021, Research and Markets estimated that the value of all sales made through social commerce worldwide in 2020 came to around USD 240 billion [7] (or some THB 7.2 trillion). By 2026, this is forecast to rise to USD 1.95 trillion (or THB 58.5 trillion), and although the Covid-19 crisis has caused supply chain disruptions of varying intensity, improving technology and better telecommunication infrastructure will ensure that social commerce remains on a solid growth track, and that very rapid rates of growth will continue.

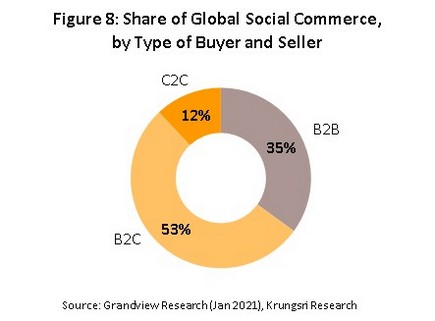

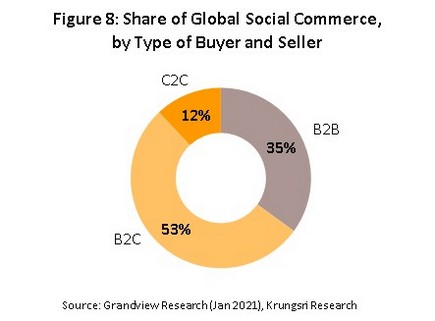

Grand View Research has also tried to estimate growth in the value of the social commerce market, and their assessment of the situation is that this will grow to USD 3.4 trillion (approximately THB 101 trillion) by 2028, giving a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 28.4% over the period 2021-2028 (Figure 7). By type of business, Grand View Research also believes that as of 2020, the world social commerce market was split between B2C, B2B and C2C (consumer-to-consumer) segments in the ratio 53%, 35% and 12% (Figure 8). It is notable that in the same year, Asia-Pacific housed the lion’s share of the global social commerce market and that within the region, social media sales generated revenue of USD 325 billion (THB 9.8 trillion), or 68.5% of the world total. Part of the explanation for this lies in the region’s continuous and ongoing investment in tech infrastructure, which is now fully capable of meeting consumer demand for mobile internet services, and from strong uptake rates of social media services, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

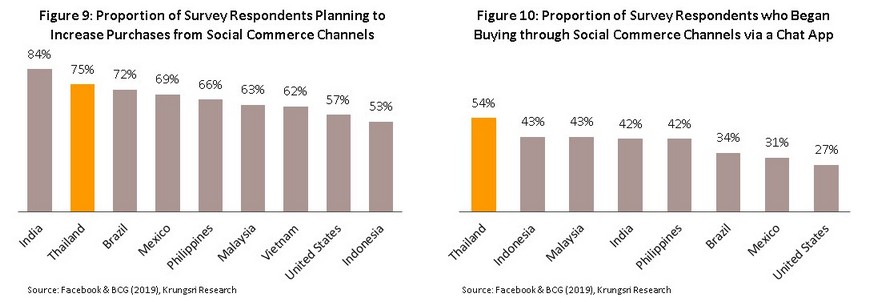

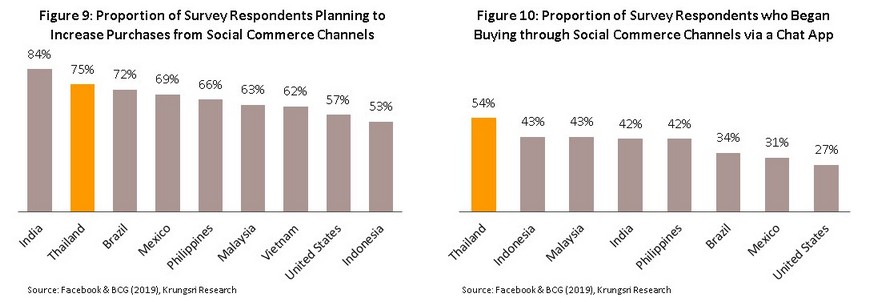

Although social commerce is becoming much more widespread at the global level, a 2019 survey by Facebook and BCG shows that it is uniquely popular in Thailand. In fact, Thailand came second in the ranking of countries surveyed with regard to the proportion of the population planning to increase the level of purchases made through social commerce (75% of Thai respondents planned to do so), with the country beaten only by India. In addition, buying through social commerce acts as a route into the market for consumers experimenting for the first time with the broader area of online shopping, and 54% of survey respondents reported that they had begun online shopping by buying through a chat app, which is one form of social commerce. This was the highest proportion of any country surveyed (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Types of social commerce

Analysis of the social commerce phenomenon is complicated by the fact that trends and preferences in social media use vary significantly from one country to the next, and this then necessarily means that the social commerce usage patterns can be highly specific to one area. Moreover, because of the extremely dynamic nature of the technology that supports it, social commerce can go through very rapid evolution and some forms that are very popular can rapidly lose their lead position before ultimately disappearing from the market altogether. This situation is further complicated by the fact that any individual purchase may involve shoppers using more than one social commerce channel. Nevertheless, some of the general types of these are given below (Figure 11).

1) Peer-to-peer sales platforms: These are websites or apps that have been set up to allow members to sell their own goods or services. There are numerous examples of these, including Etsy, a community-based e-marketplace that is centered on the sale of handicrafts and related goods, and Pinterest, a social media image sharing platform that also allows members to buy goods similar to those that appear in the pictures shared on the platform. Marketplace on Facebook is also one of the examples of this type of social commerce. In China, the Xiaohongshu app (also called ‘Little Red Book’ or simply ‘Redbook’) fills a similar role. This app allows users to share images or video and lifestyle news and although in this regard it is similar to Pinterest and Instagram, it has also expanded into online sales. In Thailand, an example of a peer-to-peer sales platform is PantipMarket. This is an extension of the Pantip web forum (Thailand’s oldest forum) and it has been established to allow Pantip members to sell goods and services to one another.

2) Conversational or chat commerce: This involves making sales through chat app that connects directly to actual or potential buyers. The chat app may be hosted on the seller’s own website or it may be part of a social media app that has the primary goal of enabling the sharing of information, images or video, such as the messaging systems that Facebook and Instagram make available, or the LINE app, which began life as a chat app but which has subsequently broadened its reach. Adding complexity to this, some sellers may make their operations more efficient by investing in labor-saving technology such as chatbots [8]. Chat-commerce may also be connected to other forms of social commerce since interest from buyers may initially be generated via another channel before the sale is closed through the chat app.

3) Selling through social media forums and social media groups: This often occurs through online groups that have been explicitly established to allow users to buy and sell goods, and often these will have a particular focus, such as ‘mother and child’ goods, though in Thailand, popular examples are centered on particular universities, such as the Facebook groups Thammasat Alumni Marketplace and Chula Marketplace. Following the outbreak of Covid-19, these have gained significantly in popularity.

4) Selling through livestreams or other types of temporary content: Selling through livestreams first began to gain popularity in China on the Chinese platforms TaoBao and Douyin (more famous outside China under its alternative name TikTok). Generally, it is only possible to buy goods that are presented or advertised during the livestream itself, when prices will be discounted from their normal rate or other types of temporary promotion may operate. This forces viewers to make snap decisions over whether or not to buy. A prominent Thai example of this is ‘Bang Hasun’, a retailer of dried seafood products based in Satun province who is able to generate up to THB 1 million in sales daily through his unique livestreams 9/. In addition to livestreams, temporary content such as Facebook and Instagram ‘stories’ is increasingly being used for sales and advertising. Retailers and marketers are attracted to the limitations of these channels, which in the case of ‘stories’ mean that content is displayed for just 5 seconds for images and 15 seconds for video. Each story is also available for only 24 hours, after which it is automatically deleted but perversely, the ephemeral nature of this content acts as a strong incentive to consumers to click through before it disappears.

5) Electronic payments linked to social media posts: Social media platforms are now adding functionality to their services that allows users to make payments for purchases made on that platform without having to use a third-party payments app. Examples of this include Facebook Pay, Twitter Buy [10] and other offerings from FinTech players that combine e-payment systems with social media services, such as Venmo [11].

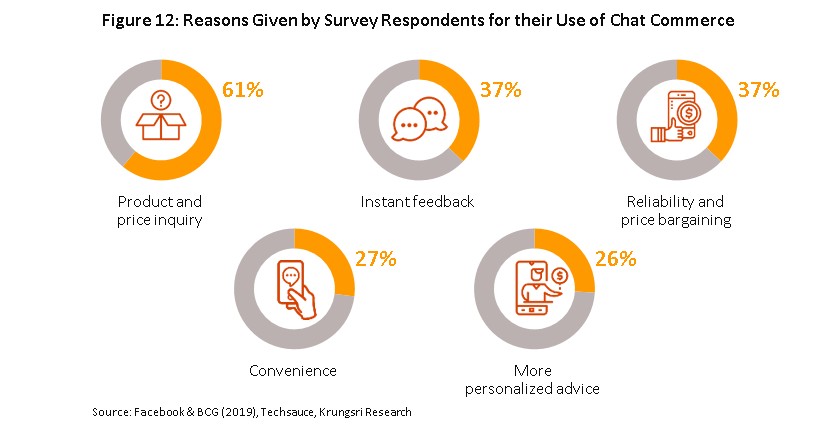

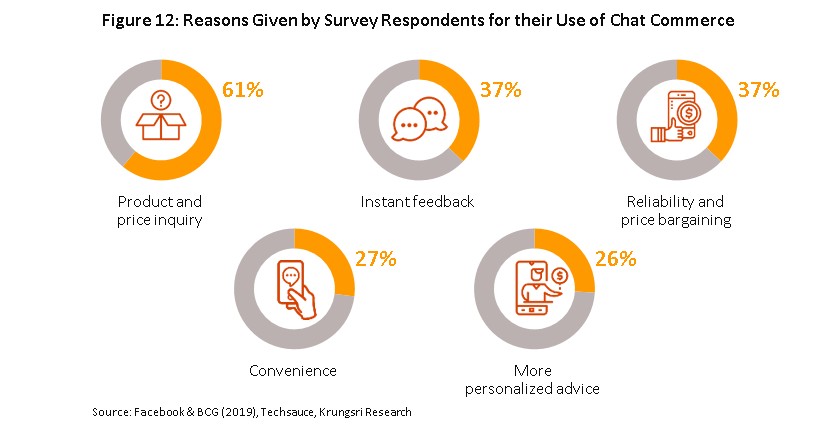

The discussion above illustrates the difficulties involved in attempting to give a tight definition of social commerce, and in fact at the borders, there may be significant overlap between social commerce and other types of e-commerce, especially on e-marketplace platforms that allow selling between users, such as Shopee and Lazada. This is further complicated by the fact that bundling the ability to make electronic payments with social media functionality might also be regarded as an extension of other types of social commerce. In the Thai context, social commerce most often occurs through chat apps, social media forums and groups, and livestreams. Chat commerce in particular has a strong presence in the broader social commerce space, and a survey by Facebook and BCG revealed the following reasons for using chat commerce: it allows buyers to make additional product and price inquiries (61% of respondents); buyers receive instant feedback (37%); it allows buyers to confirm the reliability of sellers and to negotiate prices (37%); it is easy to use (27%); and it allows sellers to provide better and more personalized advice (26%) (Figure 12).

Trends in Thai Social Commerce: Expansion or Stasis?

At the end of 2019, the managing director of Facebook Thailand revealed that because social commerce (and in particular chat commerce) is such an important sales channel for SMEs, within the next two years, he expected major new players to enter the space and increasingly contest market share. In fact, prior to the start of the Covid-19 crisis, it was forecast that over the next 3-5 years, social commerce was expected to see growth rates that would go as high as 20-35% per annum [12]. However, as described earlier, the epidemic has given an unprecedented boost to social commerce, and the Chief Commercial Officer of LINE Thailand estimates that in large part thanks to the pandemic, 83% of the Thai adult population has now bought online, with 71% of these having done so through their mobile phone [13]. LINE Thailand also estimates that 62% of online shoppers locate and then buy products through chat apps, and this figure likely reflects Thai buyers’ preference for speaking with sellers before confirming their purchases. Using chat apps also benefits sellers since this helps them to create stronger personal relationships with their customers, and this can then influence the latter’s purchase decisions at least as much as do simple matters of price.

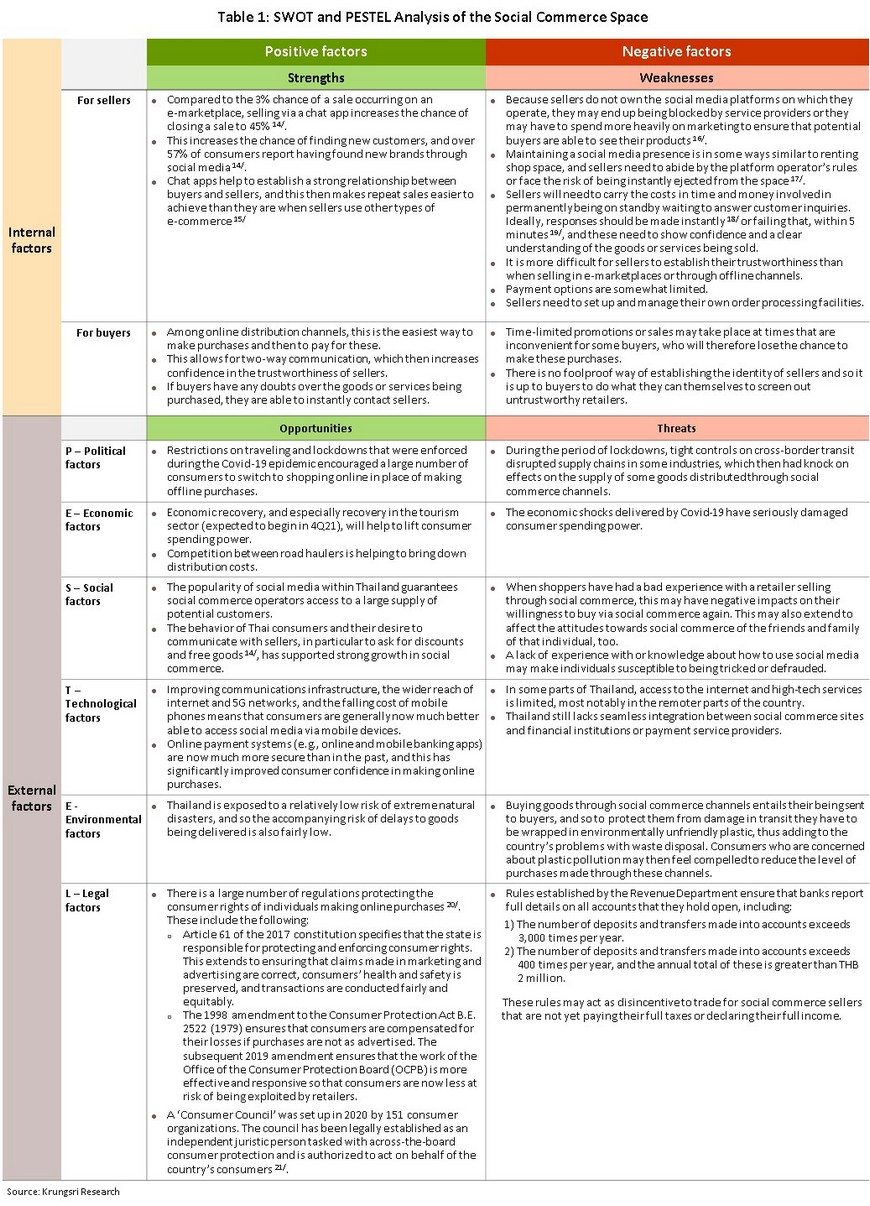

Looking into the future, however, it is somewhat unclear how social commerce will fare in the post-Covid-19 ‘new normal’, and although consumer behavior has been profoundly reshaped during the almost two years of the crisis, it is not immediately obvious how far or how long the market will be propelled by the huge boost to social commerce that this has provided. To help clear up these uncertainties, Krungsri Research has used the SWOT and PESTEL analytic frameworks. The former provides insight into the impact of (i) internal factors, comprised of strengths and weaknesses, and (ii) external factors, namely opportunities and threats. This has then been combined with an understanding of the influence of factors found in the broader business environment, which is provided by the PESTEL analysis, itself comprised of an analysis of political (P), economic (E), social (S), technological (T), environmental (E) and legal (L) factors.

Our analysis shows that social commerce benefits from a significant number of internal positives, especially with regard to how some of the features of social commerce line up with Thai consumers’ preferences for chatting with sellers before committing themselves to a purchase. For those on the selling side of the market, social commerce helps to increase their exposure to potential new buyers and to develop stronger relationships with their existing customers and through this, to build brand loyalty. Externally, social commerce has been boosted by a range of forces, including: the spread of Covid-19 and the subsequent much higher familiarity of Thai consumers with online shopping; the country’s generally good transport and logistics infrastructure, the strong competition within the sector and the resulting low costs; and the advanced state of the e-payments infrastructure. Given the alignment of these positive factors, Thai social commerce finds itself looking forward to a growth-oriented future.

Nevertheless, despite the broad array of positive factors supporting its development, the market for social commerce still has to contend with a large number of weaknesses and limitations. By definition, social commerce sellers need to establish operations on social media platforms and in some ways, this can be comparable to renting a shop, given the fact that sellers will need to abide by the rules and regulations of the platform provider, which may change without warning. Traders also need to put in place their own system for managing orders, as well as being prepared to give timely responses to customer enquiries, while beyond this, questions over the safety of purchases and payments continue to trouble the sector, and both social commerce sellers and providers of payment services need to work hard to solve these problems (Table 1).

Survey results of Social commerce behavior of Thai consumers

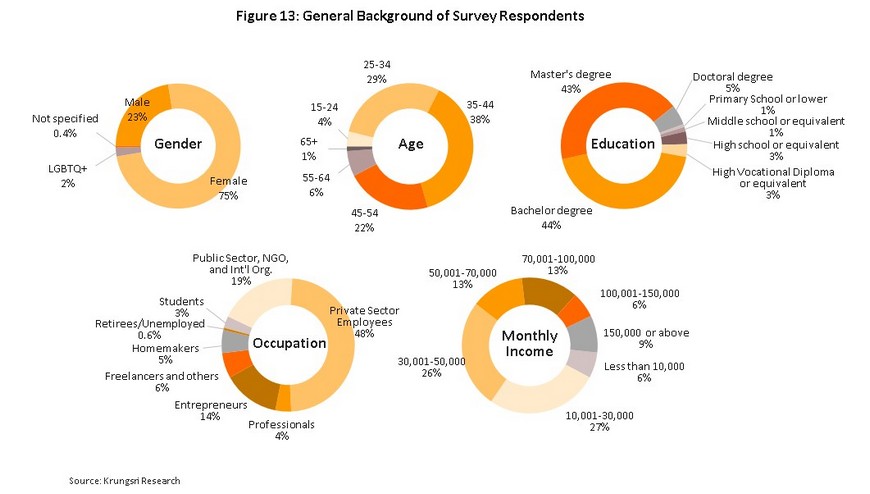

To better understand the behavior of Thai consumers with regard to purchasing goods through social commerce, between March 29 – May 1, 2021 (a period that coincided with the start of Thailand’s 3rd wave of Covid-19 infections), Krungsri Research carried out an internet-based survey that resulted in 522 responses. The survey consisted of three sets of questions: (i) general information on the respondent (gender, age, area of residence, education, and income); (ii) frequency and types of purchases made on any of Thailand’s four most popular social media platforms (Facebook, LINE, Instagram and Twitter); and (iii) preferred means of making payments for these purchases.

75% of respondents were female, 89% were working age (29% were 25-34 years old, 38% were 35-44 and 22% were 45-54), 44% finished their education with a bachelor’s degree and 43% with a master’s degree, 48% worked in the Thai private sector, 19% either worked for the public sector, a non-profit organization or an international organization, and 14% were self-employed, and over half had an income of THB 10,000-50,000 , despite an overall relatively good income distribution (Figure 13).

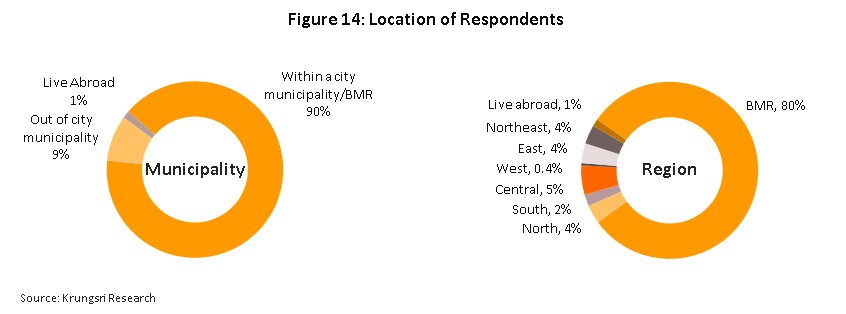

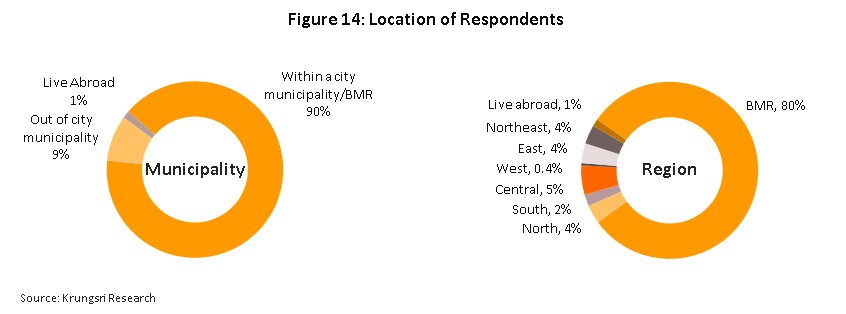

Over 90% of respondents lived either in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR) or in another municipal district, 9% lived outside a city district, and 1% lived abroad. By area, 80% lived in the BMR, 5% lived in the central region, and approximately 4% lived in each of the eastern, northern, and northeastern regions (Figure 14).

-

Behavior of social commerce shoppers

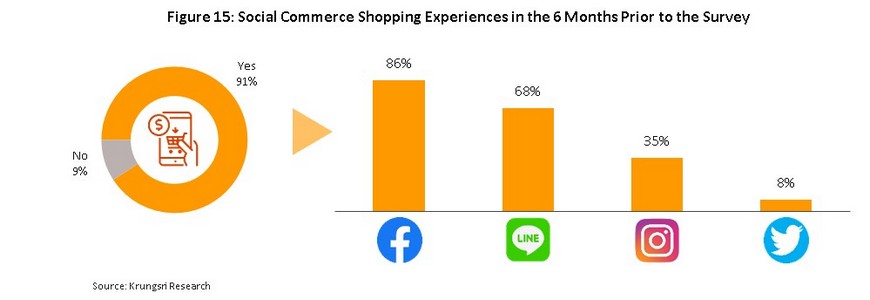

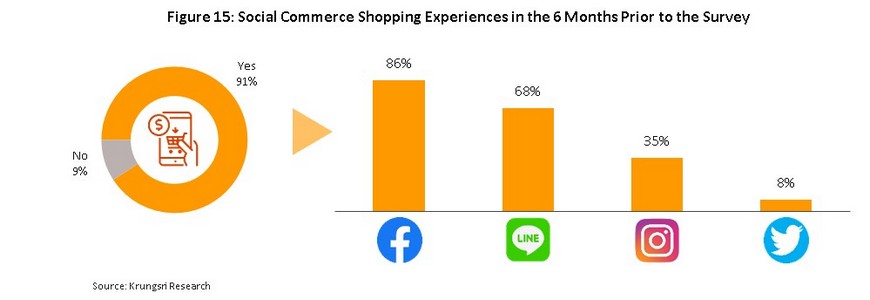

Over the 6 months prior to completing the survey, 91% of respondents had made a purchase through a social commerce channel. The most popular platforms for making purchases were Facebook (used by 86% of respondents), LINE (68%) and Instagram (35%). Twitter sat in last place and only 8% of respondents reported having made a purchase through it (Figure 15).

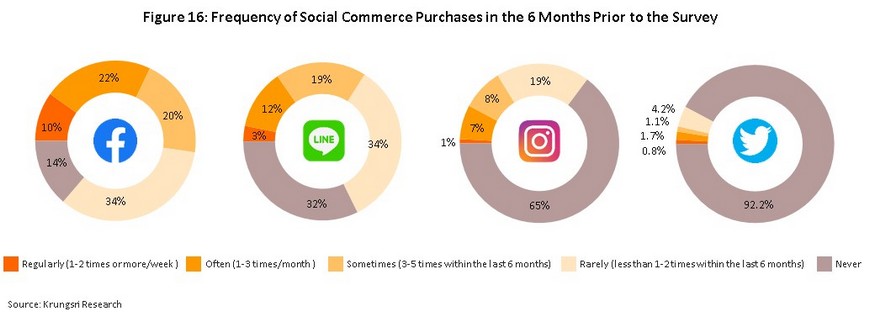

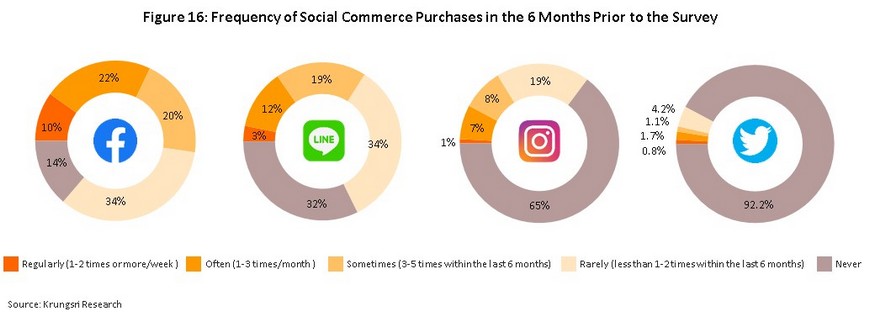

The frequency with which respondents made purchases via social commerce was somewhat correlated with the social media channel through which this happened. Social commerce took place most often on Facebook, with respectively 10% and 22% of respondents buying on Facebook ‘regularly’ (1-2 times per week) and ‘often (1-3 times per month). For LINE, the equivalent figures dropped to 3% and 12% and then to 1% and 7 % for Instagram. Twitter proved to be somewhat unpopular as a sales channel, and only 0.8% of respondents bought goods ‘regularly’ through the micro-blogging app (Figure 16).

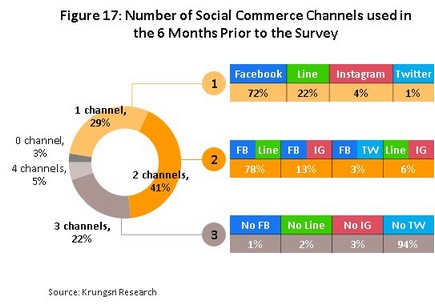

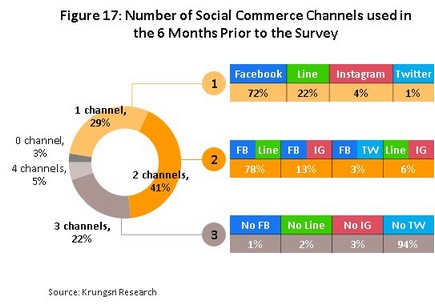

When asked how many social commerce channels they used, respondents most often answered ‘two’ (41% of the survey group), and for these individuals, the most common combination was Facebook and LINE (reported by 78% of those who bought from exactly 2 social media platforms). 29% of respondents only bought from a single channel, and for 72% of these, that channel was Facebook (Figure 17).

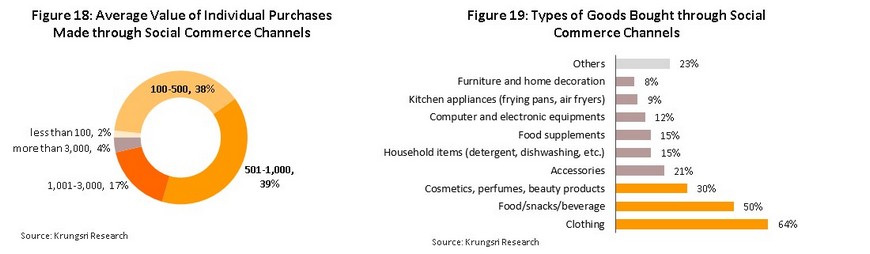

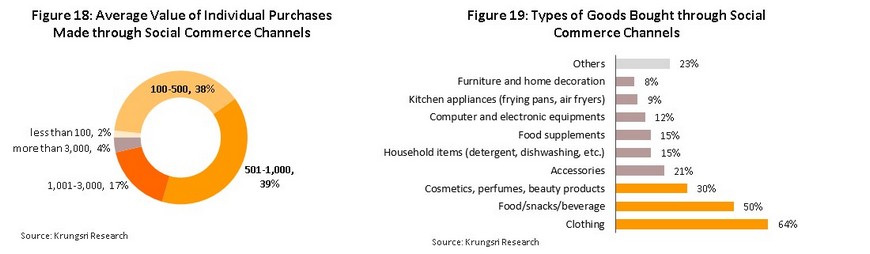

Ticket size fell into the THB 100-500 and THB 501-1,000 bands at broadly similar rates (Figure 18), while the most commonly bought goods were clothing and accessories (purchased by 64% of respondents), food and beverages (50%), and cosmetics, perfume, and beauty and skincare products (30%) (Figure 19).

-

Paying for social commerce purchases

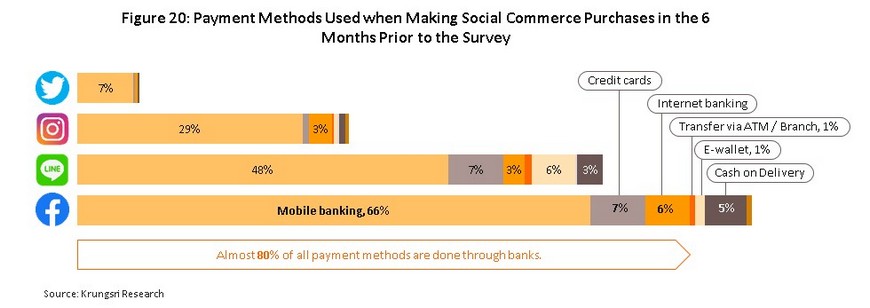

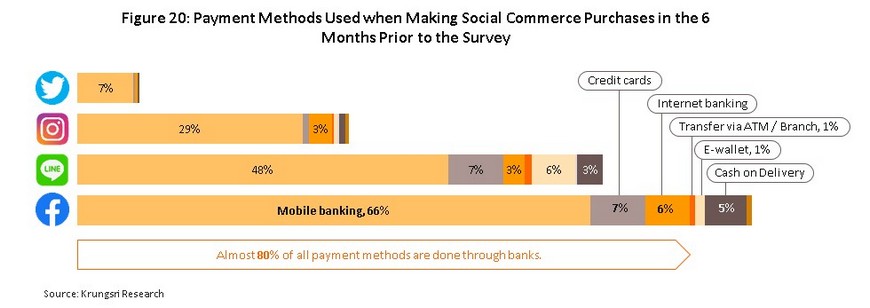

Considering all respondents regardless of their preferred social commerce channel, the majority paid for their purchases through the payment services provided by a traditional intermediary, such as a commercial bank or specialized financial institution. This was particularly notable for those buying through Facebook (the largest share of respondents), 80% of whom chose to pay through a bank, generally by making a transfer through a mobile banking app (66% of respondents reported doing this). This was followed in a very distant second place by making a debit or credit card payment (7%) and then by internet banking transfer (6%) or paying cash on delivery (COD) (5%) (Figure 20).

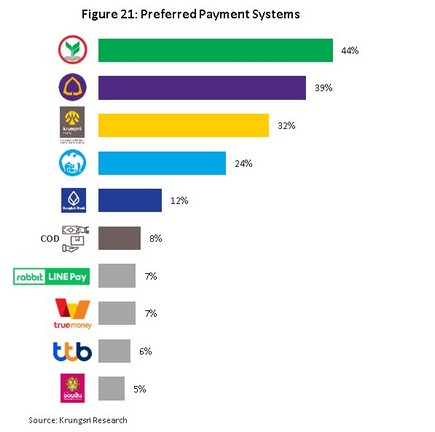

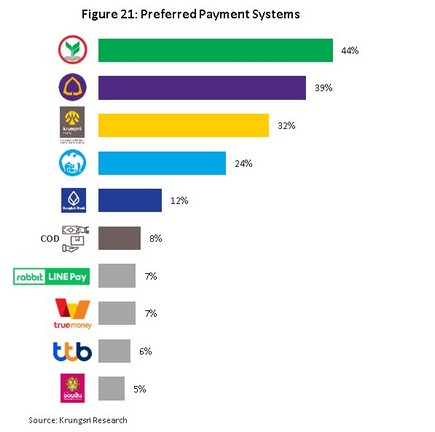

With regard to payment methods, there was a clear preference for using services provided by traditional banks. Thus, 44% of respondents made payments through Kasikorn Bank, 39% through SCB, and 32% through Krungsri. Uptake rates for non-bank service providers (e.g., Rabbit, LINE Pay and True money) were low and at just 7% each, these were all close to the proportion paying cash on delivery (Figure 21).

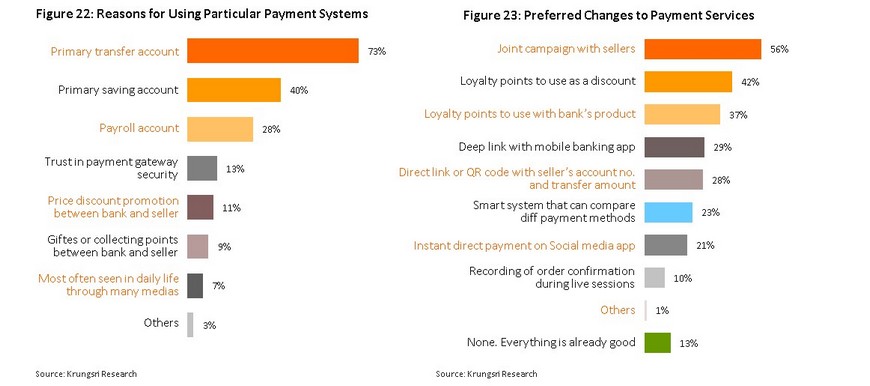

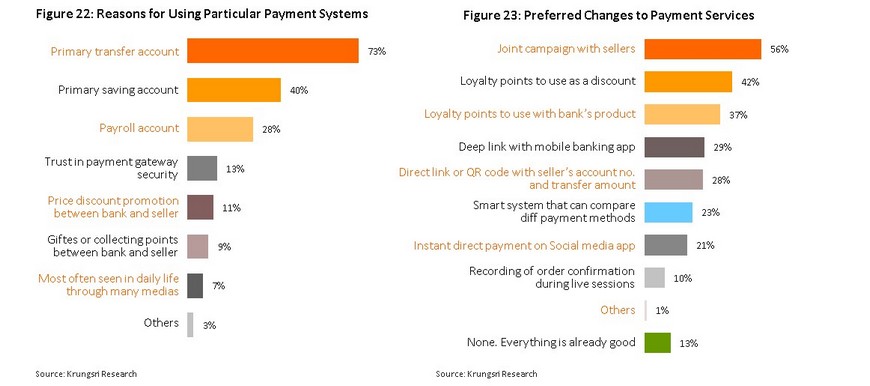

When asked about their primary motivation for choosing a particular payment service provider, the most common response was that this was the buyer’s main account for making payments and transfers (73% of respondents gave this response). The next most important reasons were that the account was the buyer’s main saving account (40%) or payroll account (28%). Other less frequent reasons included confidence in the safety of the payment services (13%), discounts or free gifts for service users (11%), the ability to participate in a bank’s points/rewards scheme (9%), and familiarity with the bank or service provider gained online or in day-to-day life (7%) (Figure 22). At first glance, it therefore appears to be the case that the effect of communications and marketing efforts that aim at building brand awareness of the service provider do not have a significant effect on buyers’ decisions over which financial service provider to use when making purchases on social commerce.

Banking services that support or encourage social commerce sales may be divided into three groups. Group 1 covers joint promotions between the bank and the social commerce seller (colored orange in the accompanying illustration), group 2 includes the development of payment systems (gray), and group 3 encompasses systems to compare and to recommend payment gateways (blue).

Survey respondents were most interested in the first of these groups, that is, promotions between banks and sellers. Most popular in this group was the possibility of seeing joint marketing campaigns between these two (56% of respondents), reward/loyalty schemes from sellers that allowed buyers to collect points with each purchase and then to exchange these for gifts (42%), and reward/loyalty schemes that allowed buyers to collect points for purchases and to swap these for gifts from the bank (37%). Overall, group 2 and the development of payment systems was the next most attractive set of options, and within this group, respondents were most keen on being able to link directly and automatically between social media and mobile banking, or to ‘deep link’ (29% of respondents). This was followed by a desire to have links or QR codes generated automatically that included the relevant account numbers and the transaction total (28%), the ability to make instant payments without having to leave the social media platform (21%), and being able to record orders and confirm transactions while sellers were livestreaming (10%). 23% of respondents were also interested in a smart system that would compare different payment gateways and then recommend the most suitable (Figure 23).

Krungsri Research view: Directions of change for banking service that can improve the overall social commerce experience

Growth in the social commerce market, which has been especially notable in Thailand, has benefitted from the conjunction of the explosion in the popularity of social media and the surge in demand for online shopping. Social commerce has thus become both a door into the world of e-commerce for a considerable number of buyers and sellers, and a major part of the broader e-commerce ecosystem in its own right. Indeed, the social commerce space is continuing to attract a greater number of consumers and greater inflows of money, and it is clear that rather than being a temporary phenomenon, social commerce is not just here to stay but will in all likelihood continue to expand through the coming period. In particular, the ability to communicate directly between buyers and sellers helps to bring the two sides of the market closer together, deepen relations and pave the way towards greater sales. The market is also helped by external factors, such as the transformation of consumer behavior and the jump in uptake of e-commerce services that the Covid-19 crisis has brought about. Nevertheless, the social commerce market faces a broad range of challenges, especially with regard to the security of online purchases and payments, but even here, the difficulties that currently affect the market also provide an opening for banks to extend and widen their participation in the social commerce space. If banks seize this opportunity, not only will they be able to support the further development of the sector, they will also be helping themselves.

The survey of consumer behavior and social commerce shopping habits that Krungsri Research has carried out has helped to underscore the economic importance of this market. Of particular note is the discovery that 91% of respondents had made at least one social commerce purchase in the past 6 months. The popular channels such as Facebook and LINE, which are the main channels of social commerce in Thailand, should continue to gain their importance, especially in an era where online shopping has become the new norm of spending.

Looking out over the near future, when the turmoil of the last two years stabilizes and the world settles into a ‘new normal’, it is likely a large share of daily life will remain permanently mediated by the internet. In light of this, financial service providers, who are really a kind of support agency for businesses active in the social commerce space, will need to develop with these changing circumstances. However, because of the sometimes marked differences between consumer groups, the most suitable path for banks to take in order to expand their customer base among social commerce buyers will very much depend on exactly which consumer groups they are attempting to appeal to.

In conclusion, it is notable that although the technological development of payment systems continues unabated, when it comes to social commerce platforms, payments generally still rely on somewhat basic mobile and internet banking systems, or even on ATM transfers, which have the considerable disadvantage of not providing protection against being defrauded by unscrupulous sellers. It is therefore incumbent on operators of payment gateways to do their best to alleviate pressure on the most obvious pain points found in the social commerce ecosystem. This is especially so for banks, which thanks to the degree of trust placed in them by the public, find themselves in the position of performing the fundamentally important role of intermediating market transactions. This trust is in fact one of the banking sector’s most important intangible assets, and banks need to find a way of using this as a lubricant to oil the market and through this, increase overall ease of making transactions, reduce friction between buyers and sellers, and alleviate problems arising from asymmetric information problem 22/. If they are successful in achieving this, both sides of the social commerce market will benefit from improved payment services and banks will be able to continue to provide long-term support for this important part of the e-commerce market.

Reference

Alix, Thomas and Stephan Samouilhan (2014) “O2O Commerce in China: What are the winning models?” KeyRus Expert Opinion Web. Retrieved Apr 2, 2021 from https://keyrus-prod.s3.amazonaws.com

Facebook IQ Insight and BCG (July 2019) The Evolution of Ecommerce: Conversational Commerce Web. Retrieved Dec 25, 2020 from https://www.facebook.com

Grand View Research (Jan 2021) Report Summary: Social Commerce Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Business Model (B2C, B2B, C2C), By Product Type (Apparel, Personal & Beauty Care, Accessories, Home Products), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2021 – 2028 Web. Retrieved Mar 16, 2021 from https://www.grandviewresearch.com/

Heroleads (Nov 2020) จับตา Social Commerce โอกาสโตของธุรกิจ รับเทรนด์ “ชีวิตติดแชท” Web. Retrieved Dec 25, 2020 from https://heroleads.asia/

Hobart, Bryan (Sep 9, 2020) “No One’s Splitting the Bill, But Venmo Is Surging” Medium.com [Blog post] Retrieved Mar 30, 2021 from https://marker.medium.com/

Indvik, Lauren (May 10, 2013) “The 7 Species of Social Commerce” Mashable [Blog post] Retrieved Mar 16, 2021 from https://mashable.com/

KBV Research (Jan 2021) Report Summary: Global Social Commerce Market By Business Model, By Product Type, By Region, Industry Analysis and Forecast, 2020 – 2026 Web. Retrieved Mar 16, 2021 from https://www.researchandmarkets.com/

Kemp, Simon (Feb 18, 2020) “Digital 2020: Thailand” DataReportal Web. Retrieved Dec 25, 2020 from https://datareportal.com/

Mahittivanicha, Narongyod (Feb 8, 2020) สถิติและพฤติกรรมการใช้ social media ทั่วโลก Q1 ปี 2020

Maxidea Studio (Apr 14, 2019) “Stories” เทรนด์ของการทำโฆษณาออนไลน์ในยุคต่อไป [Blog post] Retrieved Mar 16, 2021 from https://www.maxideastudio.com/

Muangtum, Nattapon (Feb 1, 2021) “สรุป Digital Stat 2021 จากรายงาน We Are Social เจาะลึกในส่วน Social media” การตลาดวันละตอน Web. Retrieved Mar 10, 2021 from https://www.everydaymarketing.co/trend-insight/social-media-digital-stat-thai-2021-from-we-are-social/

Muangtum, Nattapon (Jan 30, 2021) “สรุป Digital Stat Thai 2021 จากรายงาน We Are Social ตอนที่ 1” การตลาดวันละตอน Web. Retrieved Mar 10, 2021 from https://www.everydaymarketing.co/knowledge/digital-stat-thai-2021-from-we-are-social-report/

Muangtum, Nattapon (Mar 1, 2021) “สรุป 16 สถิติ Insight E-commerce Stat 2021 จาก We Are Social” การตลาดวันละตอน Web. Retrieved Mar 10, 2021 from https://www.everydaymarketing.co/trend-insight/thailand-insight-ecommerce-digital-stat-2021-we-are-social/

Pigabyte (Jan 2, 2021) “ความสำคัญของ Social Commerce และกลยุทธ์ในการสร้างการเติบโต” MarketingOops Web. Retrieved Apr 1, 2021 from https://www.marketingoops.com/

PYMNTS (July 28, 2016) “The 'Why' And The 'Wow' Of Pay With Venmo” PYMNTS.com Web. Retrieved Mar 30, 2021 from https://www.pymnts.com/

Sangwongwanich, Pathom (May 8, 2020) “Social commerce new key to survival” Bangkok Post Web. Retrieved Dec 25, 2020 from https://www.bangkokpost.com/

Sellsuki (2017) ขายได้-ไม่ได้ อยู่ที่ 2 นาทีแรก [Blog post] Retrieved Mar 30, 2021 from https://blog.sellsuki.co.th/

Simplicity Marketing () Type of Social commerce [Blog post] Retrieved Mar 16, 2021 from http://www.simplicitymktg.com/

Supachai Parchariyanon (2020) Perspective on Thailand Digital Ecosystem Web. Retrieved Mar 10, 2021 from https://www.boi.go.th

We Are Social & Hootsuite (Jan 2021) Digital 2021: Global Overview Report Web. Retrieved Mar 5, 2021 from https://datareportal.com/

Web Wednesday (Oct 2020) D2C : Direct to Customer Conference presentation. WWTH 2020: Web Wednesday 21 Bangkok, Thailand. https://www.facebook.com/webwedth/

ฐานเศรษฐกิจ (May 13, 2020) e-commerce ดันยอดค้าปลีกค้าส่งรับวิกฤตโควิด Web. Retrieved Jan 5, 2021 from https://www.thansettakij.com

เดลินิวส์ (Jan 27, 2021) "ไลน์"เผยพฤติกรรมช้อปคนไทยชอบแชตถามก่อนซื้อ Web. Retrieved Apr 1, 2021 from https://www.dailynews.co.th/

พริสม์ จิตเป็นธม (16 พฤษภาคม 2019) “ฮาซัน: ไลฟ์ได้แรงอก เปลี่ยนชีวิตพ่อค้าอาหารทะเลตากแห้ง” BBC Thai Web. Retrieved Mar 21, 2021

มูลนิธิเพื่อผู้บริโภค (Jan 6, 2021) “สภาองค์กรผู้บริโภคเกิดแล้ว! ดีเดย์ 6 มกรา ประชุมนัดแรก” มูลนิธิเพื่อผู้บริโภค Retrieved Apr 7, 2021 from https://www.consumerthai.org/

สถาบันพัฒนาวิสาหกิจขนาดกลางและขนาดย่อม (2018) เข้าสู่ยุค “อี – คอมเมิร์ซ” เครื่องมือทำธุรกิจ “ที่ขาดไม่ได้ Web. Retrieved Dec 25, 2020 from https://ismed.or.th/

สำนักงานพัฒนาธุรกรรมทางอิเล็กทรอนิกส์ (Aug 2020) รายงานผลการสำรวจมูลค่าพาณิชย์อิเล็กทรอนิกส์ในประเทศไทย ปี 2562 Web. Retrieved Dec 25, 2020 from https://www.etda.or.th/

[1] http://webstats.nbtc.go.th/netnbtc/INTERNETUSERS.php

[2] For more details on e-marketplaces, please see https://www.krungsri.com/th/research/research-intelligence/ri-online-marketplace-en

[3] Not including social commerce

[4] B2B and B2C

[5] WWTH 2020 : Web Wednesday 21, 28 October 2020

[6] .The 4 Ps, or the marketing mix, play a fundamental role in developing marketing plans. The four Ps are: product, price, place, and promotion.

[7] Calculated from an estimated 29.4% cumulative annual growth rate (CAGR) for the period from 2020 to 2026.

[8] A chatbot is a computer program that is able to respond automatically to users in a realistic way, though generally this is restricted to text messaging only.

[9] Paris Jitpentom (2019), “Hasun: How Expert Livestreaming Changed the Life of a Dried Seafood Seller’.

[10] Services began in 2015 but have since been discontinued.

[11] In the case of the online payments provider Venmo, users are able to make money transfers to one another through the Venmo app, but the app also provides a news feed and so it may be regarded as a combined social media and payments app.

[12] https://heroleads.asia/th/blog/social-commerce-trends-2020/

[13] https://www.dailynews.co.th/economic/821696

[14] https://positioningmag.com/1305388

[15] https://positioningmag.com/1254171

[16] https://marketeeronline.co/archives/116516

[17] https://contentshifu.com/blog/why-you-should-no-rely-on-social-media

[18] https://www.marketingoops.com/

[19] From “Thin Slices of Negotiation: Predicting Outcomes From Conversational: Dynamics Within the First 5 Minutes” in Journal of Applied Science. This shows that the first 5 minutes of a conversation provide sufficient information to predict the results of discussions and whether or not customers will make a purchase. See also https://blog.sellsuki.co.th/impression-in-5-mins/

[20] https://www.parliament.go.th/ewtadmin/ewt/elaw_parcy/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=1803

[21] https://www.komchadluek.net/news/scoop/385297

[22] Asymmetric information is a problem identified by economists that describes how buyers and sellers usually have different access to relevant business information. Generally, sellers are likely to have greater access to the relevant data, to the point of knowing whether or not they will actually deliver the goods being sold.