Following Thailand’s rapid eradication of community transmission of Covid-19 and the subsequent reopening of businesses across the country, the Thai baht has steadily strengthened and this appreciation in value has outpaced that of the currencies of the country’s major trade partners, leading to fears over the effects of this on the wider economy. However, the strengthening of the baht is not a recent phenomenon and over the past two decades, the baht has risen in value by more than 30% relative to these same currencies, generating concerns over the export sector, a key driver of growth for the Thai economy. An analysis of the structure of Thailand’s production sector and the connections between exports and national economic activity based on input-output tables shows that Thai industries/businesses who are net exporters (export value exceeds import value ) account for over half of Thailand’s total outputs and these industries will be negatively affected by the appreciating of the baht. A sensitivity analysis based on a general equilibrium model reveals that a 10% appreciation in the value of the baht will reduce 0.4 percentage points (ppt) from Thai GDP growth over the short-term, decreasing as much as 0.8 ppt over the long-term, in addition to slashing foreign direct investment by 17 ppt. Automobile industry is among the industries most severely affected by this. Computer and electronics industries see moderate negative impacts. Overall, the effect of a stronger baht is to undermine the competitiveness of the export sector, potentially pushing foreign investors to move production facilities out of the country and eroding the long-term growth potential of the Thai economy.

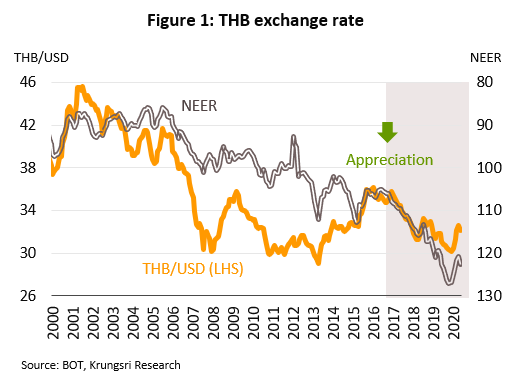

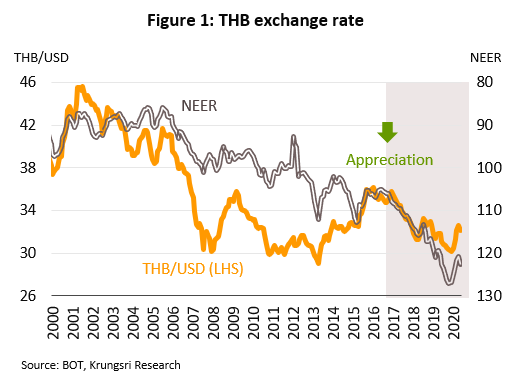

Over the past 20 years, the baht has tended to appreciate relative to both the US dollar and the currencies of Thailand’s major trading partners. In the case of the former, the baht has appreciated by roughly 25% against the US dollar, while with regard to the latter, the baht’s nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) has risen as much as 34%. Over the last 2-3 years, this relative appreciation of the baht has accelerated, leading to increased worries not just for domestic businesses and foreign investors but also more widely over the growth rate for the entire economy, both now and into the future. This Research Intelligence paper thus analyzes the impacts of the baht’s appreciation on Thai industries over the short- and long-term and how this will affect the Thai economy, in particular with regard to foreign direct investment and the outlook for economic growth.

Factors underpinning the appreciation of the Thai baht

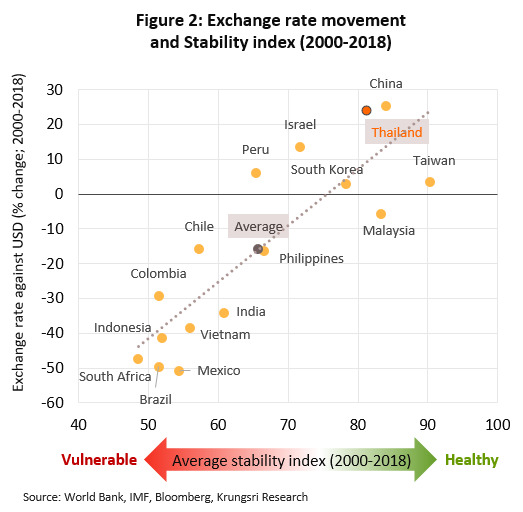

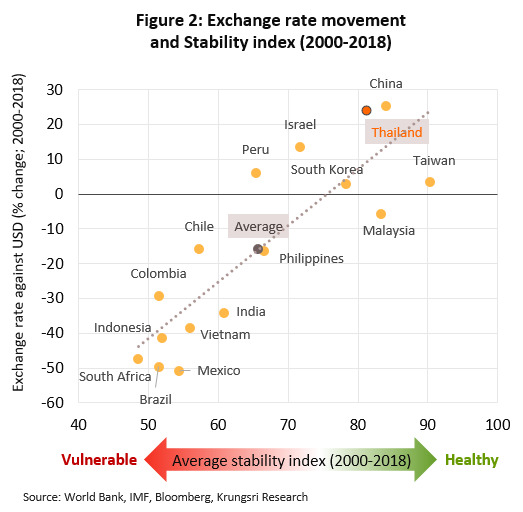

The strength of the baht can be attributed in part to the basic issue of Thailand’s external stability, that is, the country’s ability to maintain resiliency in response to external risks. Since the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998, Thailand has consistently run a current account surplus, while maintaining large foreign exchange reserves, reflecting the fact that foreign currency inflows tend to outrun outflows. In addition, domestic inflation remains low and the ratio of external debt to foreign exchange reserves is lower than that in many other emerging markets. To investigate this further, Krungsri Research has analyzed the relationship between the strength of the Thai baht and the country’s stability index. The index is in line with the International Monetary Fund’s methodology which is composed of four key economic indicators: the ratio of the current account balance to GDP; the ratio of foreign exchange reserves to GDP; the inflation rate; and the ratio of external debt to foreign exchange reserves. Data for the past two decades show that the stability index and the strength of the baht are indeed positively correlated and so countries that are more stable tend to have relatively stronger currencies (Figure 2).

In Figure 2, Thailand is on the upper right of the chart because through the previous 20 years, the baht against the US dollar has tended to appreciate faster than local currencies of other Asian countries, including South Korea, Taiwan and Malaysia, and this is related to the country’s stability. In fact, at 81.1, Thailand’s stability index is somewhat higher than the emerging market average of 65.8 and this indicates that the strengthening of the baht is at least partly driven by Thailand’s sound stability. This is in turn makes the baht a relatively safe haven for investors and pushes up demand for the currency. However, the baht appreciation generates long-term problems, both by lowering the competitiveness of the export sector and by making the country a less appealing target for foreign direct investment, and ultimately the effects of this will be felt across the economy.

The value of the baht is playing a greater role in determining the fate of the export sector

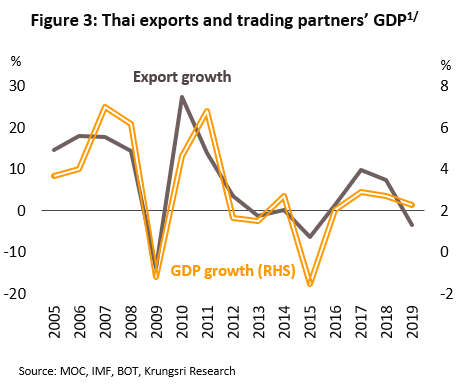

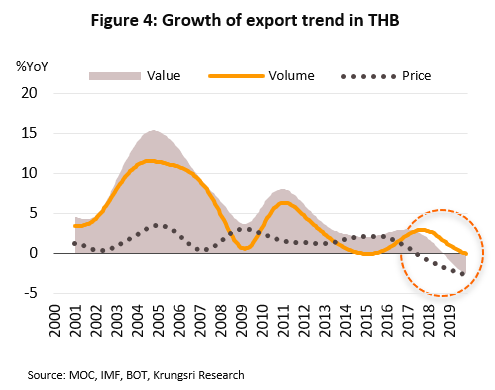

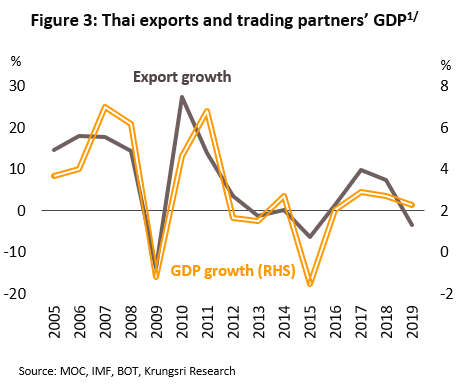

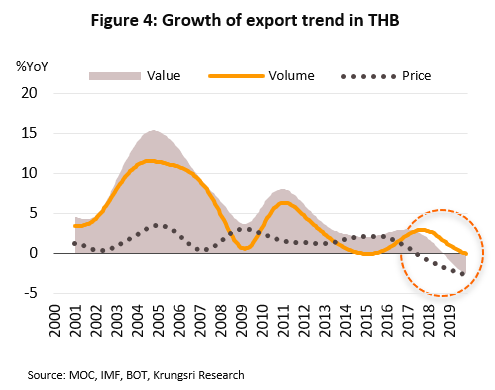

Generally, falls in the volume of exports are caused by a weakening of demand in export markets rather than by the costs of the goods or exchange rates, and data on Thai exports indicate that economic growth in export markets has indeed been relatively closely coupled with growth in Thai exports (Figure 3). Thus, in the past, as trade partners’ growth rates slowed, demand in these markets softened and this then undercut Thai exports. Figure 4 shows that the growth in exports slowed significantly in terms of both volume and value. Furthermore, over the past 1-2 years, the export price index in terms of baht has fallen at a faster pace, reflecting the reduction in manufacturers’ profit margins in order to cushion the impact of Thai baht appreciation.

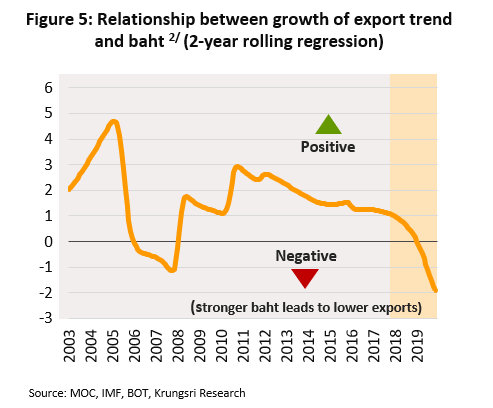

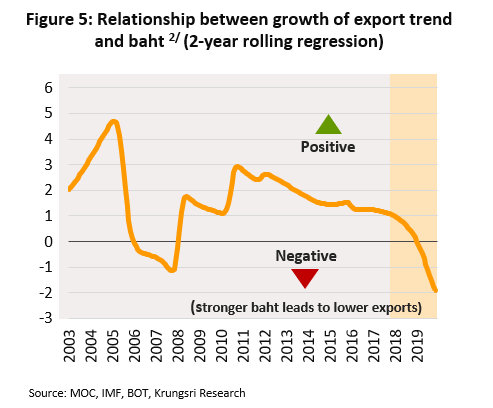

To further investigate the relationship between the value of the baht and trends in export growth, the data were analyzed using a rolling regression (Figure 5) and this shows that over the past 2 years, the appreciation of the baht has led to a drop in exports. In situations when the baht strengthens over the short-term, the fall in the volume of exports may prompt exporters to try to maintain revenue and competitiveness by sacrificing a degree of profitability and cutting export prices. However, if the appreciation in the currency happens over an extended period or is driven by structural factors, the pressure to continually cut prices will in the end erode exporters ability to generate any returns on investments, leading to a reduction of total output of the economy, although the exact impacts for individual businesses will vary from one industry to the next.

Most of Thai industries are negatively affected by the appreciating of the baht

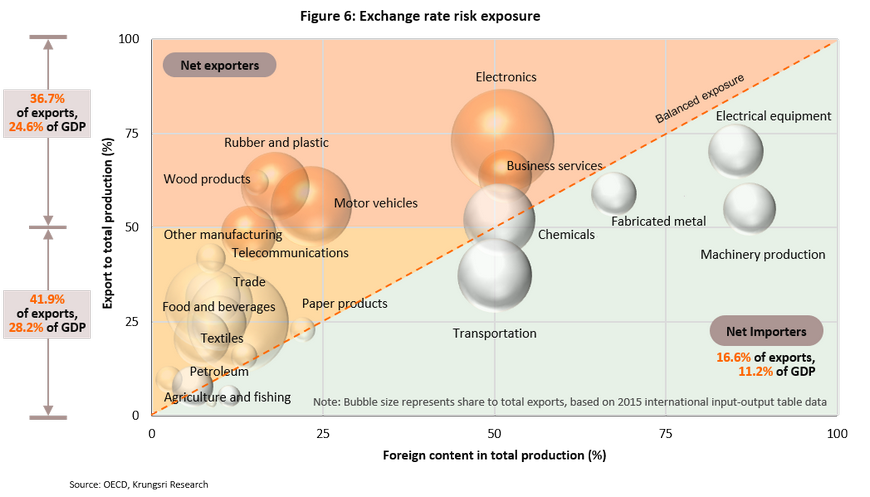

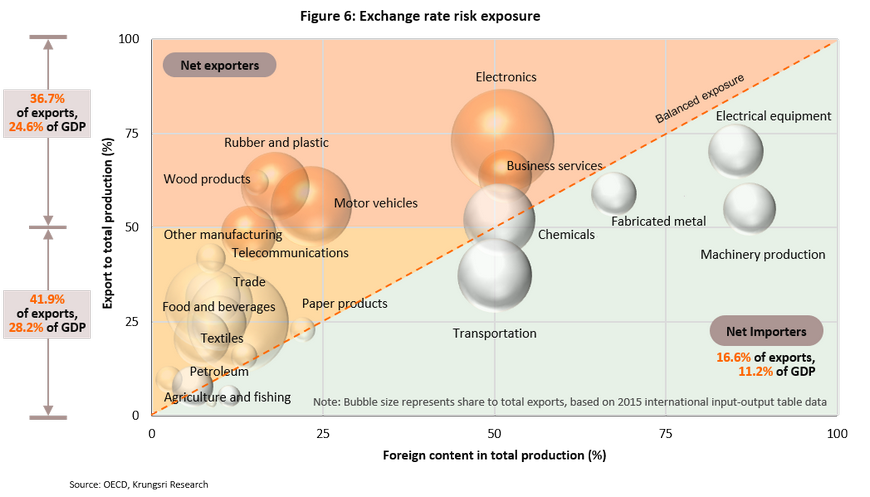

Based on the production structure of Thailand’s industries, the impacts of the appreciation in value of the baht will have either positive or negative consequences for industries, partly depending on the proportion of imports of raw materials and intermediate goods within each industrial sector. Overall, industries can be classified into three groups according to where they stand with regard to this. (i) Natural hedgers are companies for which impacts are approximately evenly weighted between positive and negative. In these industries, business activities are such that the gains and losses arising from transactions carried out in foreign currencies are largely self-cancelling, leading to a balanced exposure where currency appreciation results in losses on the export side being compensated by gaining through lower import cost. (ii) Gainers are companies that are net importers (i.e. the value of imports exceed the value of exports) and thus when the currency appreciated, they benefit from the lower costs of imports at a greater rate than they incur losses from a drop in exports. (iii) Losers are in the opposite situation, being net exporters whose main revenue derives from exports and which thus tend to have a net loss as a result of falling incomes from export sales not being sufficiently offset by the lower cost of imports. With regard to the extent of negative impacts, these will differ according to the degree of export (domestic) markets reliance. Thus, if an exporter sells more to domestic markets, or if exports account for less than 50% of total production, it will experience moderate impacts but if it relies primarily on export markets, or if exports account for greater than 50% of production, the rise in the value of the baht will cause severe impacts to be felt. Using an analysis of Thailand’s production structure and the linkages between the export sector and economic activity that is based on the input-output tables, it is possible to split industry into 3 groups according to the impacts of an appreciating baht (Figure 6).

- Industries that are positively affected by baht appreciation are net importers, but these account for only a small proportion of Thai economy, covering 16.6% of Thai exports, or 11.2% of GDP. Industries in this group typically import raw materials or intermediate goods in large quantities and so benefit from the falling cost of imports. These industries includes electrical equipment production, transportation, machinery production and fabricated metal production.

- Industries that experience moderately negative impacts of baht appreciation account for 41.9% of Thai exports or 28.2% of GDP. These industries principally sale to the domestic markets and are not primarily rely on exports. Examples include the textiles industry, telecommunication, accommodation and real estate, food and beverages industry and financial services providers.

- Industries that experience severe impacts of baht appreciation are typically producing primarily for serving external demand and these account for 36.7% of Thai exports, or 24.6% of GDP. These industries consist of electronics industry, motor vehicles, wood products, rubber and plastics products, and providers of business services.

In light of the above, the appreciation in the value of the baht cannot be described simply as good or bad and the impacts are different depending on the specific type of industries, the proportion of imports and exports, and the relative dependency ratio on export or foreign markets. However, that said, total industries that are negatively affected are larger than those that are positively impacted, while in addition to its effect on exports, the appreciating of baht also influences other economic variables, in particular, the extent to which the economy can attract foreign direct investment (FDI) and how well it can maintain its long-term growth potential.

For every 10% of Thai baht appreciation, GDP loses 0.8% over the long-term, and FDI drops 17%, with impacts especially hard for motor vehicles industry

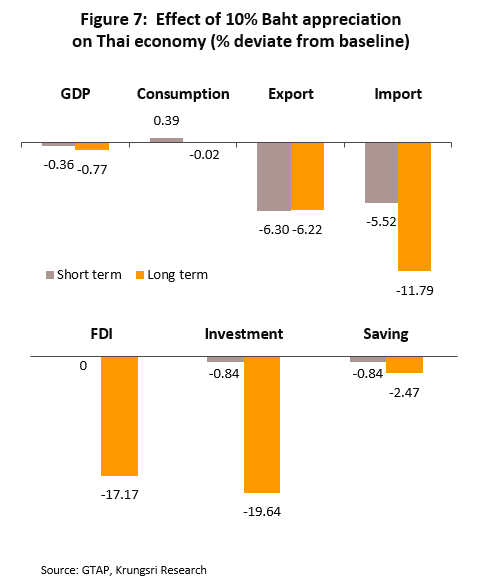

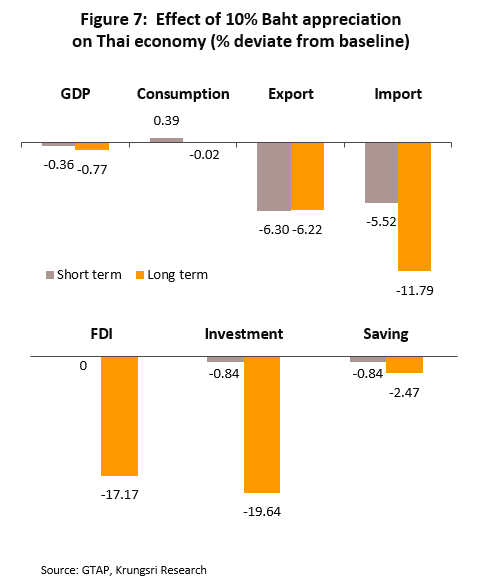

Krungsri Research has carried out additional research into the short- and long-term impacts on economic variables of the appreciation of the baht. This applies a sensitivity analysis under a general equilibrium model, with the assumption that in the short-term, FDI will be unaffected by changes in exchange rates but over the long-term FDI will respond to currency movements. The results of this analysis are given below.

- In the short-term, a 10% appreciation of the baht will lead to a decline in GDP of 0.4%, a drop in domestic investment of 0.8%, and a contraction in imports and exports of respectively 5.5% and 6.3%, respectively. In this case, the fall in imports will be caused by a drop in demand for raw materials and intermediate goods that would otherwise have been processed into exports.

- Over the long-term, assuming that investors are able to relocate their production base and FDI can be freely flow, this analysis indicates that with the same 10% strengthening of the baht, exports will fall by 6.2%, while FDI and domestic investment will contract by 17% and 20%, respectively. This would then slash 0.8% from GDP relative to the baseline condition, doubling the short-term impacts, and so this leads to the conclusion that the longer the baht’s value appreciates, the greater the resulting economic losses (Figure 7).

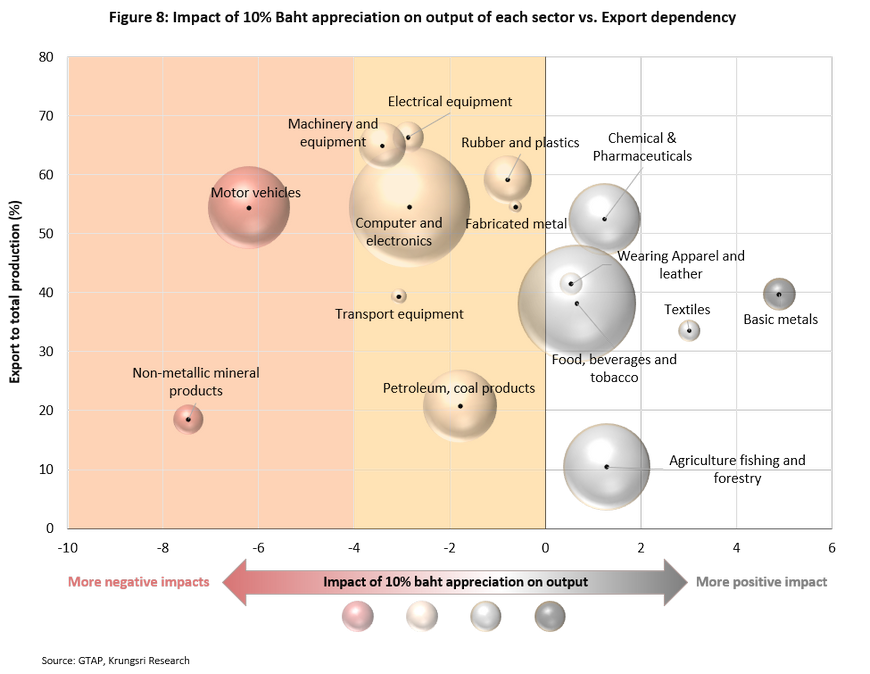

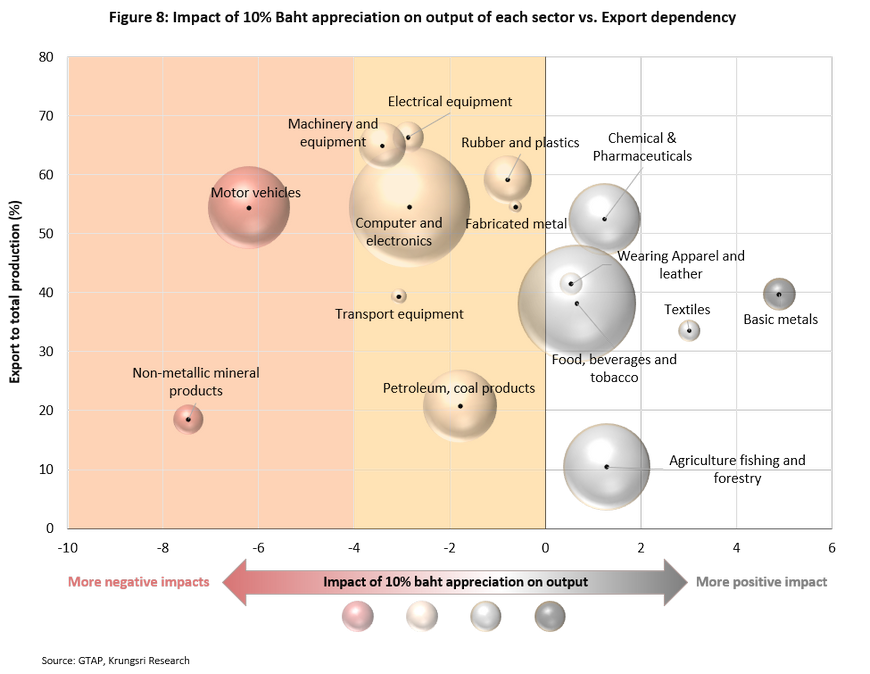

In addition, when the analysis of the long-term output losses arising from the 10% appreciation of the baht is split according to industrial sector (Figure 8), it becomes clear that only a few industries are net gainers (i.e. they are in a position to gain from lower import costs and selling to domestic markets) and for these, the benefits are mostly worth less than 2% of total output, whereas for over 60% of Thai industry, the long-term effects would be negative, resulting in a decline in total output between -8 to 0%. These negative impacts may be classified as either moderate or severe:

- Severely affected industries under this analysis are those that would see a long-term loss in output of -8% to -4% and this would include motor vehicles manufacturers and non-metallic mineral producers. These industries account for 11.6% of national output.

- Moderately affected industries are classified as those that result in a drop in output of 0 to -4%, led by computer and electronics manufacturers, manufacturers of machinery products and transport equipment, and producers of rubber and plastic products. These industries attributed 48.4% of Thailand’s total output.

The above analysis shows that the industrial sectors affected by the appreciating of the baht are major growth engines of the Thai economy and that over the long-term, the impacts of the baht’s appreciation are overwhelmingly negative. Most notably, looking back over Thailand’s recent economic history, especially over the last decade, the rate of growth in the economy has clearly slowed, while private-sector investment has also weakened, which is precisely the situation that this analysis would predict. In the coming period, it is therefore important that serious efforts are made to counter the effects of the baht’s appreciation in value because without this, the currency’s strength will continue to erode the export sector’s competitiveness, reduce incentives to invest in Thailand and hold back long-term growth in the economy.

Although recent macroeconomic policy has led to the country’s sound external stability, the long-term costs in terms of losing competitiveness and weak investment are now clear, and to avoid extending these problems, a new balance between stability and growth needs to be found. If this is achieved, it may then help to solve the Thai economy’s structural problem of being ‘strong on the outside but weak in the middle’.

[1] Averages weighted according to the GDP of trade partners, these comprising

China, the Eurozone, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines,

Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam.

[2] The value of the Thai baht relative to the US dollar (THB/USD).