E-marketplaces have exploded in popularity in recent years and the effects of this have been seen not just in the ever-growing numbers of customers making purchases online or in the total value of these but also in the fact that e-marketplaces have proved to be fundamentally more efficient than their older, off-line predecessors. Thus, e-marketplaces greatly reduce geographical limitations on market activity, they slash the overheads associated with entering the market as a seller or in sourcing goods as a buyer, and the algorithms that power modern e-marketplaces are increasingly efficient at matching buyers and sellers, while the prices of goods sold online continue to fall, and all the while, markets are becoming increasingly transparent. All this happens as a natural outgrowth of e-marketplace operators acting to preserve and to develop their markets because the actions that operators tend to undertake to build value for their businesses and to increase their competitiveness also tend to have the consequence of increasing market efficiencies overall. The moves that are involved in this process generally fall under the heading of either maintaining and extending the existing user-base or of increasing access to and use of two types of information: (i) data that is used to identify and verify information about buyers and sellers, the quality of goods sold and the payment methods that are available, together with data that relates to the tracking of orders and the safety of buyers’ personal information; and (ii) that which relates to the reliability of data on products that are for sale. Given this, the role of the government in this area should be limited to setting and enforcing standards for managing and supporting the use of e-marketplaces rather than interfering directly in the activities of online operators. In particular, the government should focus its efforts on matters related to consumer protection, maintaining online privacy, securing the data of both buyers and sellers, and maintaining fair and equitable online competition .

E-marketplaces are more efficient than earlier types of market with regard to both the number of buyers and sellers that they attract and the greater access to information that they provide

Exchanges of goods between buyers and sellers can be thought of as a way of allocating resources within the economic system that use the market as a means of generating the greatest utility, and if this allocation is made efficiently, this will then produce benefits for the buyer, the seller and society at large. Buyers will benefit from acquiring goods at a fair price, since the price is set as a result of competition between vendors within the market. For their part, sellers (or producers of goods) will benefit by gaining easier access to buyers due to the lower costs of entry to the market as well as by their having better information on the goods for which consumers have expressed a desire, while competition between sellers will also spur the development of new goods and improvements in their quality, and this will then benefit society overall and will allow for the most efficient and cost-effective use of resources. In this way, increasing market efficiencies increases the benefits accruing to all members of society. In terms of identifying markets that are efficient in economic terms, these have five characteristics[6]. These are:

- Efficient markets are home to a sufficiently large number of sellers that any given seller lacks the power to set prices and is instead bound to sell at a price dictated by the market.

- Efficient markets also have a large number of buyers and as with suppliers, no buyer has the power to individually set prices.

- Sellers are free to enter and leave the market as they wish.

- Goods and services are homogenized within the market.

- Sellers and buyers have complete access to information, that is, they should have access to and full use of information relating to the price and quality of goods and services for sale, as well as full information on the buyers and sellers themselves.

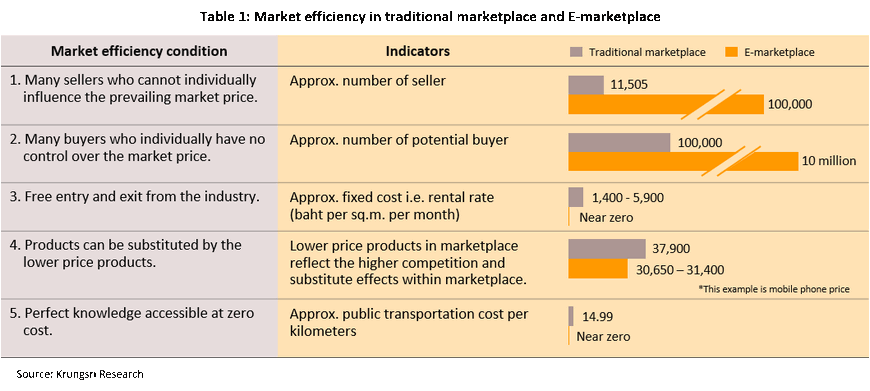

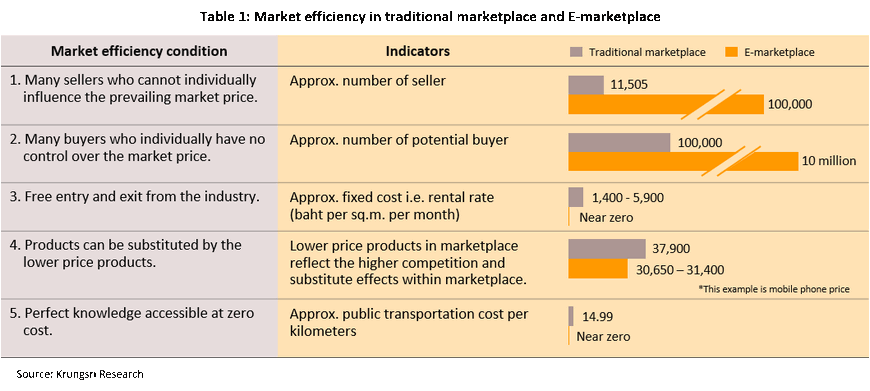

When traditional and e-marketplaces are compared with regard to the above conditions, it is clear that of the two, e-marketplaces are the more efficient (Table 1).

Condition 1: E-marketplaces have the potential to house a greater number of sellers since they are not restricted in terms of the physical space that they occupy in the way, for example, that bazaars are. In the case of the latter, over the short-term, it is not possible to expand the space that they occupy to serve a greater number of buyers so, for example, Chatuchak Market is restricted to its 11,505 semi-permanent stalls (as of 2012)[7], compared to e-marketplaces, which have no such physical limitations on their ability to grow to serve additional sellers. E-marketplaces are instead able to respond almost instantly to increasing numbers of both buyers and sellers entering the market and serving more than 100,000 buyers or sellers poses no problem to them8/.

Condition 2: E-marketplaces also serve a greater number of buyers because, as with condition 1, they do not face physical limits on their ability to serve buyers, and in addition, it is also possible for buyers to enter the market to browse or to make a purchase at any time that suits them. Physical markets do not have these benefits so Bangkok’s Chatuchak Market, is open only on Saturdays and Sundays and serves approximately 100,000 visitors[9] between around 8.00 in the morning and 9.00 at night (the exact times depend on the part of the market), which contrasts sharply with e-marketplaces that can host over 10 million users (buyers or sellers)8/ who may visit the market at any time.

Condition 3: Sellers may enter and leave e-marketplaces more freely than traditional markets. The ability to enter and to leave markets is determined by many factors, including high costs of entry, which may be monetary (e.g. the expenses incurred in renting shop space or in accessing public utilities) or non-monetary (e.g. ensuring compliance with regulatory frameworks). If one compares just the financial overheads, renting a stall at Chatuchak costs between THB 1,400 and

THB 5,900 per month[7],[10], while establishing a presence on the Lazada or Shopee platforms incurs no initial fees[11].

Condition 4: Both online and traditional markets typically make available a wide range of products so this condition is less relevant. However, if one compares similar products which are marginally differentiated on quality, such as many electronic goods, e-marketplaces usually show greater levels of competition on price for comparable goods and so they usually set lower prices than those found in traditional markets, thus benefiting buyers.

Condition 5: Buyers and sellers may access data via e-marketplaces at a lower cost since both groups are able to find information on prices and the quality of goods almost instantaneously, thus incurring low time-costs. This compares with the considerable time it may take to find comparable information in traditional markets and travelling between markets or department stores to compare prices or other aspects of goods that are for sale carries with it considerable overheads in terms of time and money (the average cost of travel in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region is THB 14.99/kilometer.)[12]

When one considers the five factors described above, it is clear that the structure of e-marketplaces is such that they will generally be more efficient than traditional, offline markets and because of the way that they greatly increase the number and range of contacts between buyers and sellers and make available a wider range of goods, e-marketplaces help to generate greater utility on both sides of a transaction. At the same time, operators of e-marketplaces also benefit from the access that they gain to a potentially vast quantity of data (so called ‘big data’) on all points of the purchasing pathway, from deciding to look at a particular item, putting that in a shopping basket, making a payment (including the type of payment and the payment provider, i.e. whether this is made via a bank or an e-wallet), through to choosing the means of delivery. Making this information available to operators allows them to analyze all aspects of the users’ interactions and so improve the overall user experience for both buyers and sellers. However, the most important factor in building efficiencies in e-marketplaces stem from operating within a platform ecosystem (Box 2).

The increased efficiency of e-marketplaces is a consequence of the emergence of platform businesses

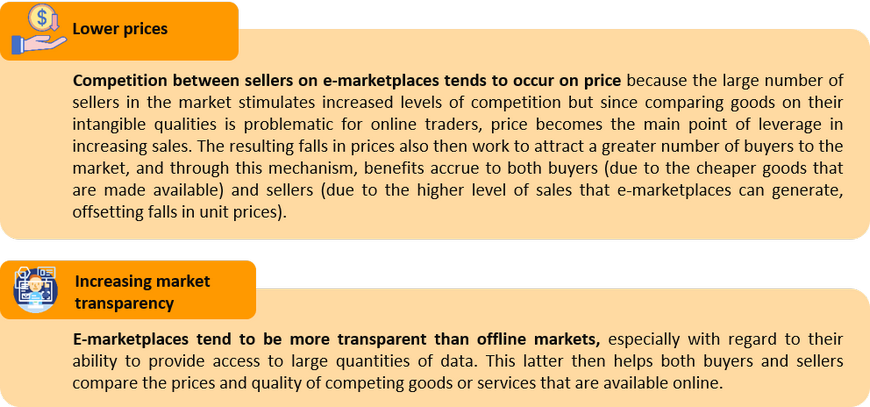

E-marketplaces typically operate through the platform business model, and in doing this they exploit the fact that large numbers of people now have access to the internet, thus giving operators the opportunity to build their user-base and to accumulate larger datasets on those same users. In contrast to earlier times, when buyers and sellers had to be located close to one another, the extension of the internet has helped to vastly expand the number and range of the points at which buyers and sellers may meet and this has then led to growth in borderless trade, as well as cutting the costs associated with the data gathering that it is necessary to carry out when buying products and services (e.g. the costs arising from searching for products and finding sellers of these). In addition, platform businesses are also able to use these benefits to improve the efficiency of their business in attracting increased numbers of buyers and sellers to the platform, and this then generates increased competition on price through the impact of network effects and the greater transparency that the platform data provides for buyers and sellers. Connecting buyers and sellers in just a few e-marketplaces will help operators to better match these as well as generating higher levels of competition, which will in turn guarantee that no individual operator within the market is able to sell goods at an unreasonable price, in addition to ensuring that access to information is fully and equally available to all by maintaining this in a single space.

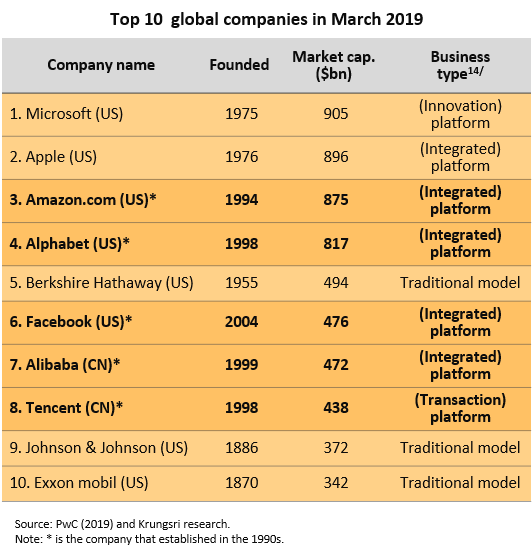

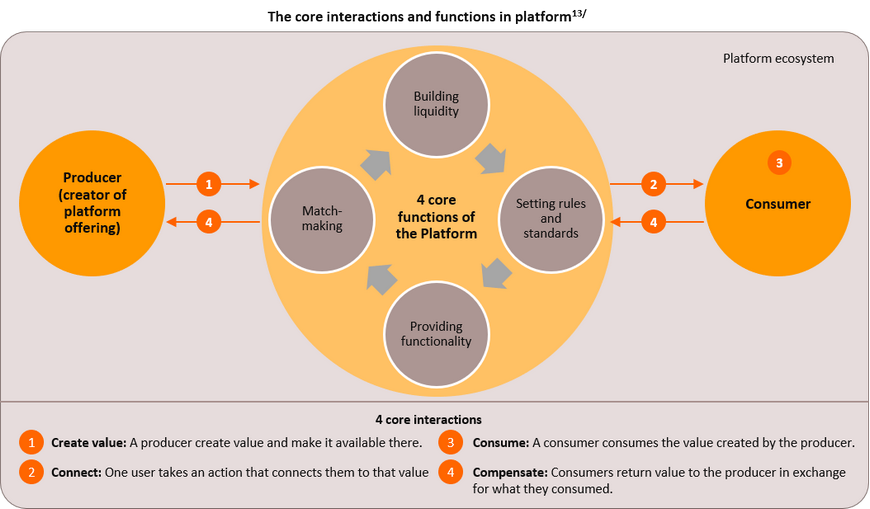

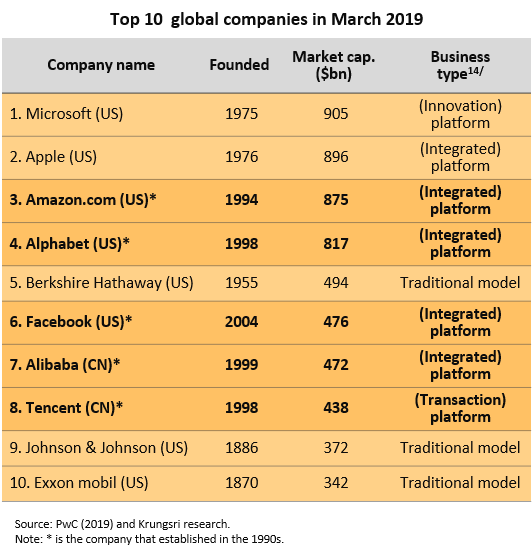

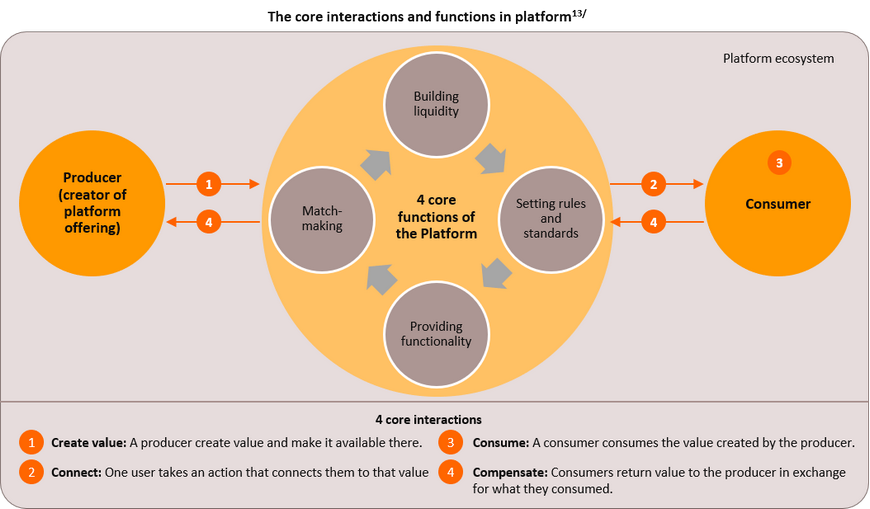

A very notable feature of the business environment that has developed over just the past few years has been the extraordinarily fast growth of a number of companies, in particular tech-based operations, which have been able to establish themselves as world-leaders in a very compressed period of time. The majority of these are also platform-based and as of 2019, of the ten companies worldwide with the highest market capitalization, seven were platform operations (see the table to the right) and five were only established in the 1990s, these being Amazon, Alphabet (Google) and Facebook from the US and Alibaba and Tencent from China. Compared with earlier business models, this rate of expansion is almost unbelievably rapid but the most important factor in explaining these companies’ meteoric rise is the impact of network effects, which may be split into the two main categories of (i) positive same-side network effects, which attract users on the same side of an exchange, for example, with regard to Facebook, how new users are attracted to the platform by the fact that a large number of their friends are already active there and (ii) positive cross-side network effects, which attract users on the other side of the exchange. The latter describes, for example, how buyers are attracted to Amazon by the fact that there are a large number of sellers already on the platform, although at the same time, sellers will also be attracted to the platform for the same reason, that is that there are large numbers of potential or actual customers to be found there. The number of active users, the growth rate of the user base, the frequency of use and the continuation of this use through time all help to increase the exchange of value and this is then how these types of business produce their value[13]. The interactions that occur on platforms and the way in which they generate and exchange value is illustrated below but assessing this type of value differs in important ways from traditional businesses, where business value stems largely from the value of the goods and services that are traded.

Market-based self-regulation

Unlike earlier business models, which built value directly through the goods and services that they sold, platform businesses create value and develop competitive advantages through the interactions that occur on the platform, the strength of which is underpinned by its number of active buyers and sellers, and the volume and frequency of economic transactions that occur within it. Beyond this, as has been shown, platforms’ value-creation processes also tend to pave the way towards greater market efficiencies and so platform operators have an incentive to improve the performance of their own markets by continuously maintaining, reviewing and developing their services to meet the needs of both buyers and sellers (i.e. to engage in a kind of market-based self-regulation) with the goal of attracting new users to the platform on both the selling and buying sides, while also encouraging existing users to continue to use their e-marketplace services. Moves that are made by operators as they pursue these goals can be split into two major groups: those that aim at increasing the number of new users entering the market and those that aim at using data resources to keep existing users active there. Details of these are given below.

1. Increasing the number of new users active on the platform

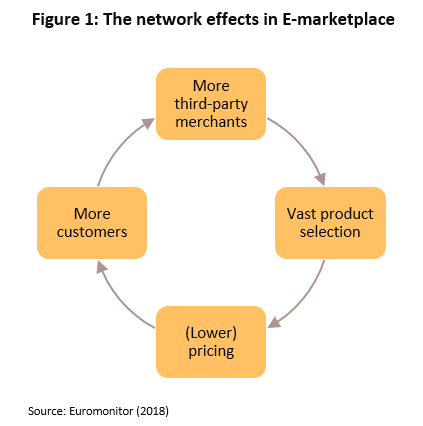

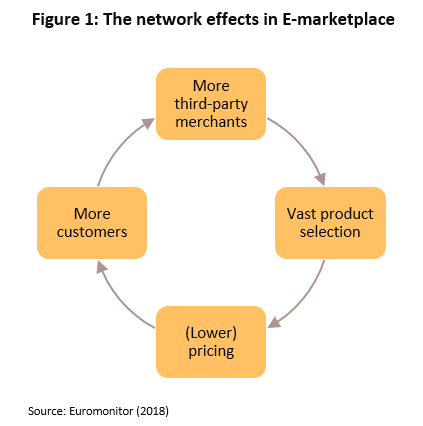

At the heart of platform business operations lies the network effect, which creates value for platforms by attracting ever greater numbers of buyers and sellers in a self-reinforcing virtuous circle. Operators will begin by trying to attract third-party merchants to their platform, with the goal of making available as vast a product selection as possible. This will then generate price competition between sellers, thus pulling down prices overall and this will act as an incentive to buyers to enter the e-marketplace in increasing numbers, but as the number of buyers present in the market rises, this will also then attract a greater number of new sellers, who will compete against one another within the market. This kind of attractive force, which operates both on the same side of the market (i.e. between buyers and buyers and between sellers and sellers), and across the market (i.e. between buyers and sellers and vice versa), is the most prominent feature of the network effect and when this builds over time, it can have the effect of very rapidly increasing the number of users buying and selling on a platform (Figure 1).

However, when platforms are structured so that they rely on the two main user-groups of buyers and sellers, this may lead to a chicken-and-egg problem because buyers may decide not to enter the market if there are only a few sellers there, while sellers will not be interested in establishing a presence in an online market that has an insufficient number of buyers. This is a problem that new operations routinely encounter, and attempts to overcome it often rely on investing in two main strategies: building trust in the operator of the e-marketplace and choosing to support the right user group[14].

In the first case, operators try to build trust and faith in the stability of their e-marketplace by emphasizing the amount of money that has been invested in it. Sellers, in addition to needing to have access to large numbers of buyers, need to be assured that the market that they are entering is secure and stable because of the up-front investment that they need to make in understanding and mastering a new e-marketplace, and if this market then turns out to be unsuccessful, then clearly sellers will be unhappy about having squandered the time and money it took to build a presence there. To overcome the hesitancy in sellers that this problem may generate, operators attempt to underscore the confidence that they have in their operations by highlighting the often considerable investment funds that they attract. For example, in 2017, Alibaba announced that it would increase its investment in Lazada by more than USD 1 bn, while in 2019, SEA announced that it was investing over USD 1.5 bn in Shopee. An alternative to this is for operators to first build confidence in the viability of the market among buyers by taking on the role of sellers themselves before allowing in other distributors. This was the route taken by Amazon, which began as the sole provider of goods on its own market but then switched to a policy of opening the platform to third-party sellers.

In the second case, platform operators attempt to support an important part of the user-base, the growth of which will then help to stimulate an expansion in the user-base overall. This may be done through promotions or by providing services that are easier and more convenient to use. Appealing to users in this way may take one of two forms.

(1) Attracting users who are already active on another platform by developing services that are easier or more convenient for sellers to use, for example by developing a Thai-language platform or sales channels that customers prefer, such as presentations of products that are broadcast live.

(2) Attracting users who are new to these kinds of platforms, for example by waiving or discounting fees when first using the platform.

2. Developing and exploiting a range of data resources

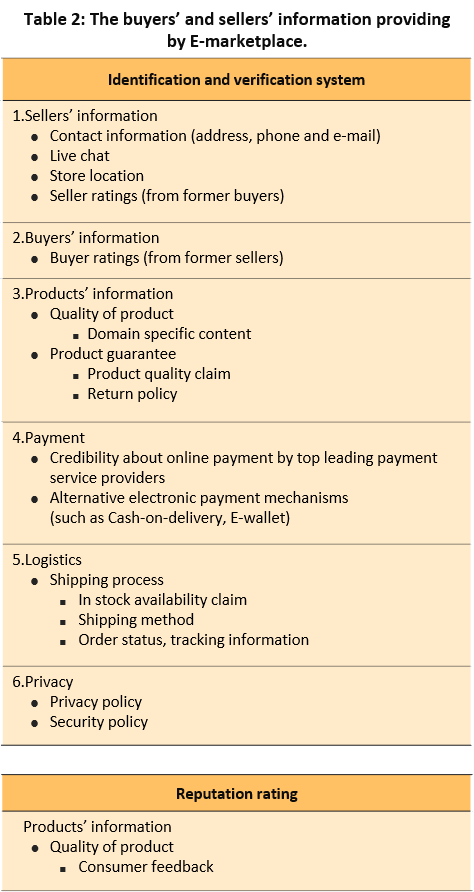

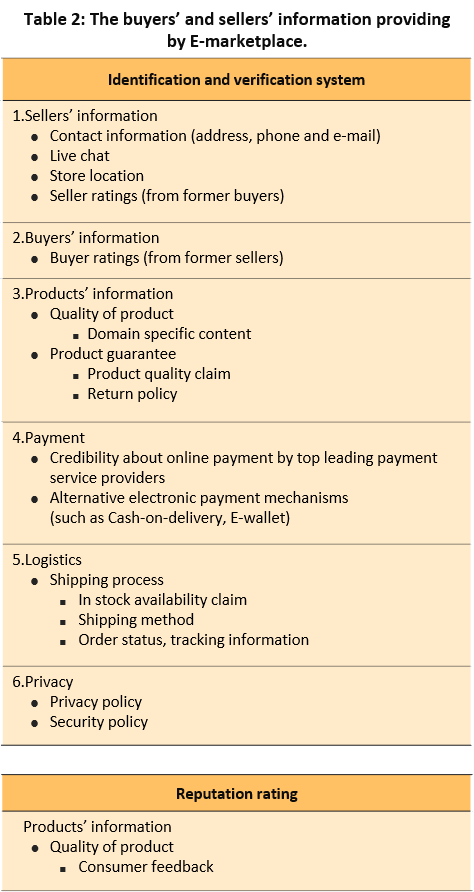

As shown above, the emergence of e-marketplaces has greatly reduced search costs by extending the range of buyers and sellers that may be included within any search and by increasing the number of goods that meet a particular consumer preference for quality and price, but having access to this greatly increased number of buyers, sellers and goods has also had the effect of making the role of the market operator clearer, while simultaneously reducing the operator’s role as a middleman. Thus, in offline markets, buyers are restricted to purchasing goods only from those sellers in the market that the buyer is able to locate, or in the case of imported goods, to buying only those selected product groups that will be represented in the market, but in e-marketplaces, buyers are able to make purchases from the greatly expanded number of sellers present on the e-marketplace, and both buyers and sellers face much reduced costs in entering this latter type of market. In addition to this, the information available on the number of buyers and sellers and on the wider and more varied range of products available helps e-marketplace operators develop algorithms that better match market participants and this then increases the chance that purchases will be made. However, at the same time, exchanges of goods and services that are made online suffer from problems related to the asymmetry of information between buyers, sellers and e-marketplace operators. It is therefore necessary to make this information more widely available and by doing so, make it easier to identify buyers and sellers and to ensure the quality of goods that are for sale. In pursuit of this, e-marketplace operators have developed both identification and verification systems and reputation systems, which together can be divided into the following six main categories.

- Information on sellers: This allows buyers to check the trustworthiness of individual sellers by supplying contact information, the location of the seller and ratings provided by buyers who have previously purchased from them.

- Information on buyers: This includes ratings provided by other sellers on individual buyers and this allows sellers to check their trustworthiness.

- Information on goods: This information provides a way for buyers to check on the quality of goods that are for sale and may originate either from the seller, who may supply specific information for particular items, or from the e-marketplace operator, which can confirm the quality of goods by checking against returns.

- Information on payment methods: User confidence in the security of payment systems is boosted by, for example, prominently displaying the company logos of leading payment providers, although consumer confidence and satisfaction can also be increased by extending the payment options to include choices such as cash on delivery services, which allow consumers to check the quality of goods before completing their purchase. In Thailand, cash on delivery payments have proved to be very popular and account for some 60%-70% of online purchases[15].

- Information on delivery services: This permits both buyers and sellers to check on the ability and trustworthiness of delivery agents and shippers, and to track deliveries from the moment a sale takes place. This may include the ability to check on the quantity of goods remaining in a seller’s stock and to investigate a wide range of delivery options available from trusted and well-established delivery agents, and usually also includes some kind of interface for following a package’s progress.

- Information on buyer’s data security: This information includes the platform’s policy with regard to data security, privacy and the release of buyers’ personal information and data on sales to third parties. It may also include ways of preventing operators from releasing information for unauthorized uses. This aims to build trust in the security of any personal information that may be collected by or stored on the platform.

As regards developing information related to particular goods, there is a single channel, that is simply information on the good’s quality. By allowing those who have already made purchases to award points and/or to leave comments, potential buyers may check an item’s quality and so their confidence in any purchases that they may make should increase.

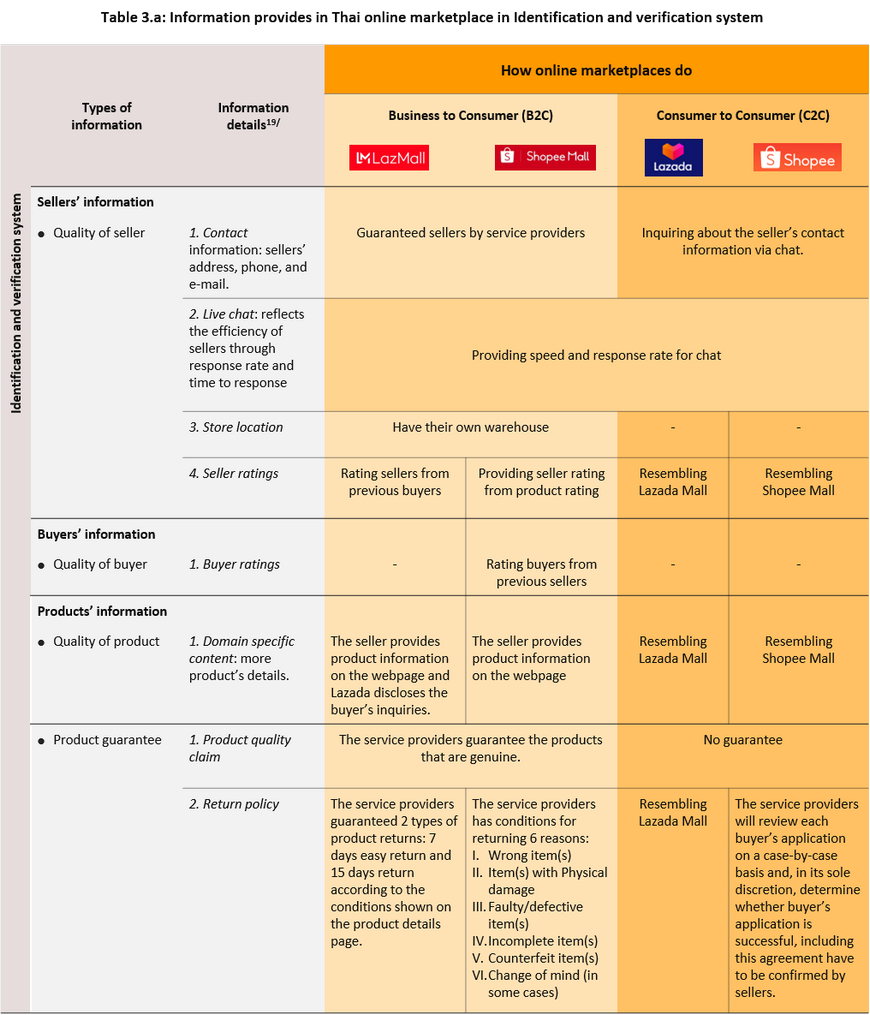

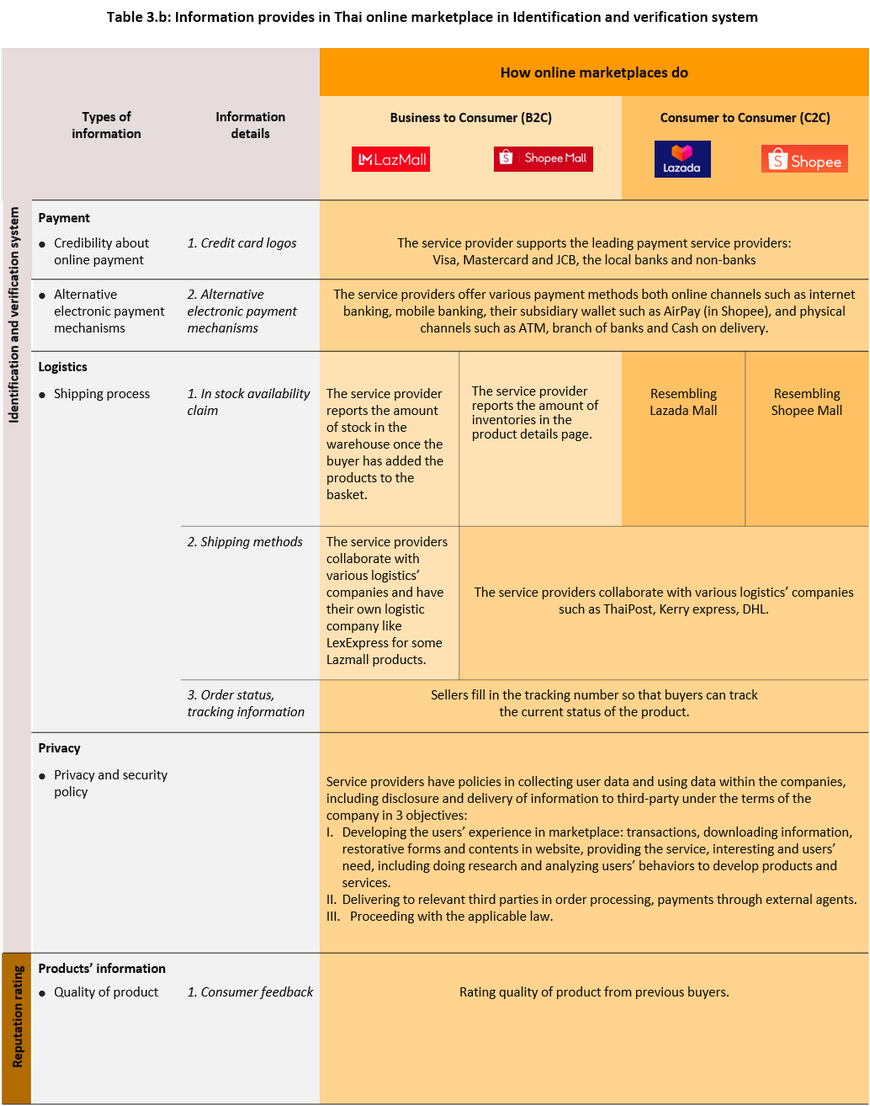

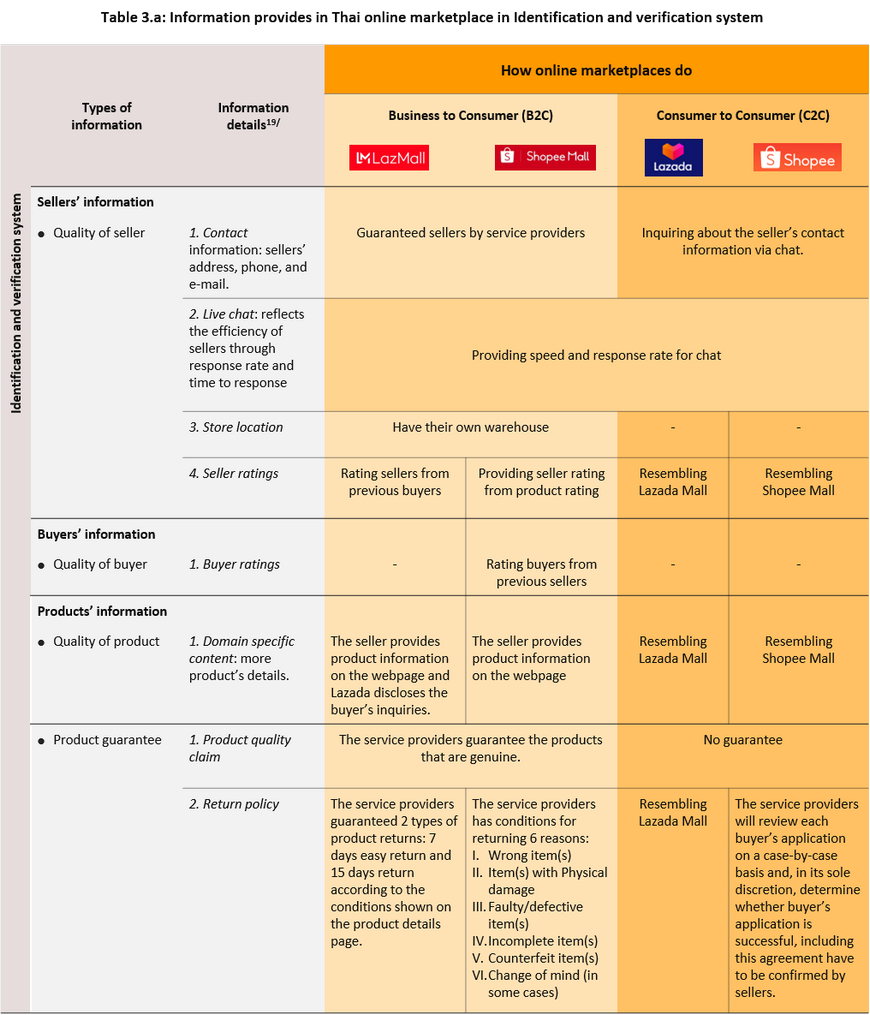

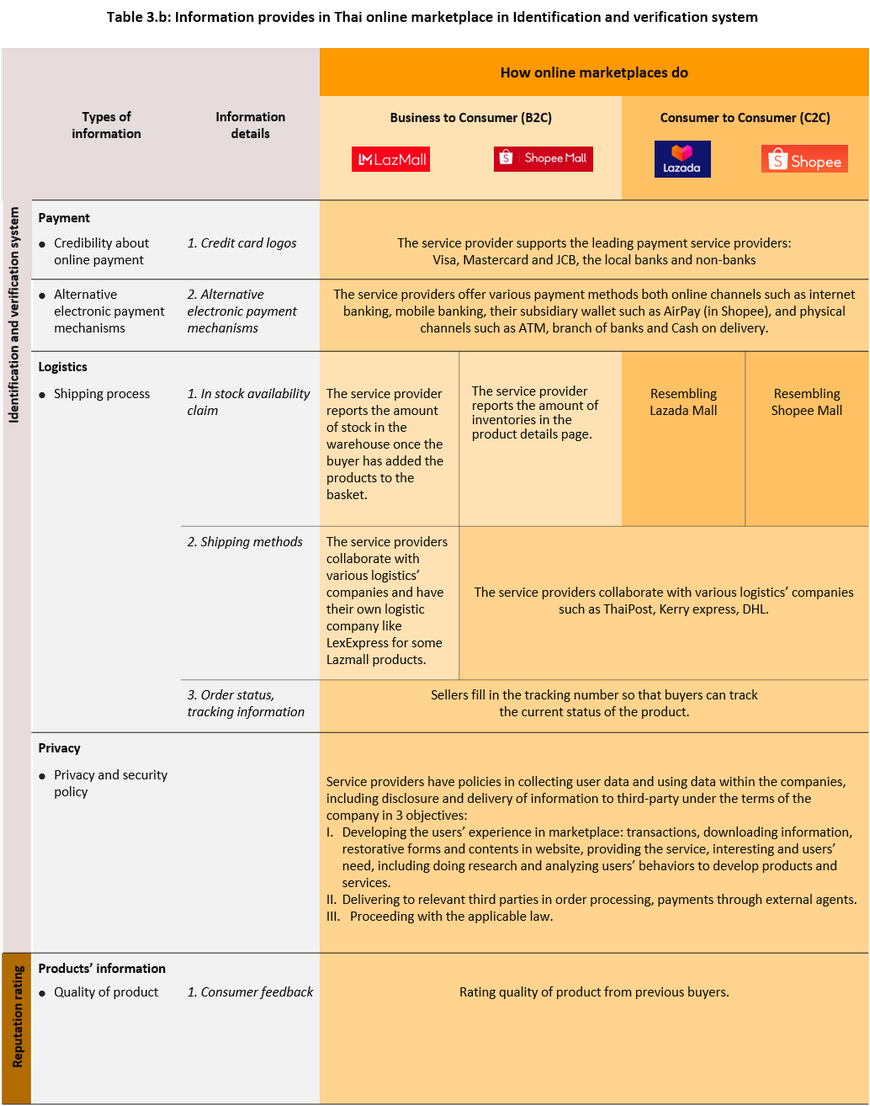

In the particular case of Thailand, research shows that the two largest e-marketplaces of Lazada and Shopee have both developed systems to make available and to check information in each of the six categories outlined above, but there are nevertheless some differences in how these two platforms put these into practice. These differences take three separate forms (see Table 3 for details on the information that is provided by Lazada and Shopee).

- Returns policy: Because it is not possible to check the quality of goods purchased on an online platform before making a payment, it is important that the site’s policy on returns is made clear to customers, in particular with regard to the window of time within with purchases may be returned after delivery. In this case, Lazada’s conditions are more favorable towards buyers than are Shopee’s. Lazada makes it easier and cheaper to return goods, especially for those shops that guarantee to take returns within 7-14 days, and it is shops not buyers who pay the cost of this postage. This contrasts with Shopee, where both sellers and buyers need to agree to an item’s return and the customer needs to cover the initial cost of posting the return (for which they will not receive compensation if the shop decides not to offer it).

- Additional details on the quality of goods for sale: Platforms support the inclusion of additional information on goods that are for sale beyond the basic data provided by sellers to varying degrees. Lazada displays questions that are asked by different customers about particular items on the page for that item so that both the questions and the answers to them are publicly available to anyone interested in the product, whereas Shopee uses a private chat system to link buyers and sellers, with the result that previous enquiries are not publicly available and different prospective buyers may receive different answers to the same question.

- Providing support for buyer ratings: When participating in e-marketplaces, information demands are not limited to just knowledge about sellers and their goods, and traders too may need access to this kind of data about prospective buyers, especially for exchanges that occur between smaller sellers or buyers. Thus, Shopee makes it possible to rate buyers after they have completed a purchase, and this then allows other sellers (though especially small and medium-sized players) to check the trustworthiness and general quality of a buyer, and so hopefully protect themselves against the possibility of fraud. However, problems exist with this since systems where two parties mutually award points tend to generate over-inflated scores because awarding an excessively high mark avoids the risk of one side retaliating by awarding a low score should it receive one, although one way of avoiding this is not to reveal scores until after both sides have submitted theirs16/.

The value generated by e-marketplaces is increased by raising the number of sellers and buyers active in the market and by collecting more comprehensive information on market activities. With regard to the latter, of particular importance is developing information resources where the market operator specifies the framework that governs the collection of information, ensures that appropriate prices have been set and records user behavior by checking any comments that they have left. At the same time, the competition that occurs between operators of e-marketplaces pushes each to put in place measures to supervise and to monitor its own market, which leads to a situation of market-based self-regulation.

However, self-regulation is not always sufficient or effective and in some cases, e-marketplace operators may grow to the point that they have too much power, such as when a platform acquires a market share and a user-base that puts it a long way ahead of its competitors so that it then begins to demonstrate monopoly behavior. In this situation, a platform may then set conditions for entry to the e-marketplace that provide more benefit to the operator than they do to platform users. When this happens, government agencies have an important role to play in ensuring that the situation is resolved and that the greatest possible benefits result for buyers, sellers and other e-marketplace operators. To take a real-world example, the development of Amazon has moved in a similar direction to this. Amazon is the largest platform operating in the US and as such enjoys a 39.7% market share by value of online sales17/, which the company protects by running a policy of checking to see whether the same seller distributes the same goods on other online platforms and if they are, whether or not they are available cheaper at a site other than the Amazon platform. If the latter turns out to be true, to prevent sales being lost to a third party, Amazon then warns that supplier and applies pressure to them to raise their off-Amazon prices, with the threat that failing to do so may lead to their being prevented from trading on the Amazon platform in the future18/.

Government agencies may monitor and support buyers and sellers on platforms through the implementation of consumer and data protection policies

E-marketplaces that are marked by an appropriate level of competition tend to monitor the activities of buyers and sellers within the market, and because this then leads to more efficient markets, the role of government in this area should be restricted to setting the big-picture regulatory framework for monitoring and supporting users of e-marketplaces, rather than interfering in the actual operations of these platforms. In particular, the government should concern itself with issues related to consumer and data protection, user privacy, and ensuring fair competition between e-marketplaces.

- Consumer protection policy and legislation: The sale of goods and services online tends to encounter recurring problems with ensuring that buyers and sellers are who they say they are and making sure that goods or services are as described. In response to this, the majority of e-marketplace operators will typically turn to solutions based on the development of identification and verification and reputation ratings systems, which help to improve the quality of information that is available. However, while measures such as these can help to improve the efficiency of the screening that goes on within the platform, being absolutely confident about correctly identifying users or guaranteeing the quality of goods is extremely difficult, and it is here that government agencies may have a role to play in helping to monitor the situation and in issuing regulations or implementing policies to alleviate these types of problems. Within Thailand, the Office of The Consumer Protection Board (OCPB) is, as its name suggests, tasked with consumer protection, as set out in the 1979 Consumer Protection Act, although this extends only as far as business to consumer sales that are made domestically.

- Data protection policy and legislation: An extremely important aspect of e-marketplaces is the capture of the information that arises from the huge number of transactions that occur across their very large user-bases and the use of this for the development of those same e-marketplaces. These improvements may be in the system for matching buyers and sellers or in that for selecting goods and services for prospective customers but either way, the value of this data derives in part from its scale and the greater the quantity and variety of data that is available to e-marketplace operators, the more efficient the e-marketplace’s backend is likely to be. However, in some cases, this data may be used not to improve the internal workings of the market (and so lead to benefits for platform users) but may instead be used to generate business advantages for the e-marketplace operator directly, for example by being used to suggest goods to customers that are being promoted but which may not best match those customers’ actual needs. Alternatively, data generated within an e-marketplace may be used outside that market by another company, either in cooperation with the platform operator or by being sold to a third party without the consent of platform users having been sought in advance. This is another point where state agencies have a role to play, and it is incumbent on them to develop policies to monitor infringements of users’ data rights (for both buyers and sellers) on e-marketplaces and to put in place laws and regulations to protect the use of online personal data. A notable example of this is the European Union’s 2018 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), while in Thailand the Electronic Transactions Development Agency is responsible for data protection issues, as specified in the 2019 Personal Data Protection Act, which comes into effect on May 28, 2020.

- Competition and antitrust policy and law: Problems with unfair competition between platforms and e-marketplaces are beginning to attract increasing interest, and a striking example of this is Amazon’s so-called ‘most-favored nation’ clauses, which the company has been including in contracts signed with e-book publishers. Under these agreements, e-book publishers are contractually obliged to ensure that the conditions offered to Amazon are at least as good as those agreed with other distributors, which then makes it very hard to compete against Amazon, although in this case, the company has been investigated by the European Commission, which has ordered it to cease the practice[19]. Problems such as this may be encountered and then resolved by governments in countries that are home to large-scale domestic platforms, such as the United States or within the European Union, but in Thailand, the government has yet to develop a clear policy to counter these types of threats.

Krungsri Research view

The extremely rapid growth in e-marketplaces and the explosive expansion in their user-bases has incentivized operators of these to increase the efficiencies of the online markets that they operate. At the same time, they have added value to their operations and extended their potential by attracting large numbers of buyers and sellers to their platforms, while using the data generated from the markets to retain and further attract users. However, although the development of these services helps to look after the interests of users on the platform, there is also room for government agencies to look after users’ interests by issuing supporting regulations, monitoring the situation, and resolving problems as they arise, although this should not extend to direct interference in the operation of particular e-marketplaces. In Thailand, the use of e-marketplaces has risen very dramatically over the past five years, although operators of the larger markets active in the country have been able to respond to this and to improve the efficiencies of their markets appropriately. Over the same period of time, government agencies have also attempted to develop a place for themselves in the new business landscape by more actively looking after the interests of platform users, through the use of both existing laws, such as the Consumer Protection Act, and new laws, including the Personal Data Protection Act. It is hoped that this will then help to develop an environment within which Thai e-marketplaces will be able to see sustainable and beneficial levels of growth.

[1] Euromonitor (2018). How brands survive in a digital marketplace world.

[2] ETDA (2019).

[3] The Standing Committee on Commerce, Industry and Labour, The National Legislative Assembly (2016). The structure of the retail trade in Thailand, its problems and possible solutions, published by.

[4] From a survey of the value of e-commerce in Thailand in 2018, published by ETDA (2019).

[5] Krungsri (2019), Industry Outlook 2019-2021: Modern Retail Trade.

[6] Mansfield and Yohe, (2004). Microeconomics: Theory ] Application.

[7] The Center for Economic and Business Forecasting, University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce (2019).

[8] From a report published by Lazada on July 11, 2019 stating that they had more than 10 million users, over 800 official stores on the LazMall site, and at least 100,000 sellers.

[9] From a report published on mcot.net which made reference to comments by the Assistant Director of Chatuchak Market.

[10] These are the rental rates set by the State Railway of Thailand between 2014 and 2019 for renting space at Chatuchak Market.

[11] At present, neither Lazada nor Shopee impose initial fees for establishing a presence on their platforms. This is with the exception of opening a shop on either Lazmall or Shopee Mall, for which fees are set according to the type of goods sold. Instead, both platforms collect commissions on sales, though again, the rate depends on the goods sold. Value added tax is also collected by the platforms.

[12] From a report by BLT Bangkok published June 12, 2019. The report refers to research carried outby the Thailand Development Research Institute Foundation (TDRI).

[13] Krungsri Research (2019). From Pipeline to Platform: New Wave of Changes in Payment Business, Applico

[14] Parker, G.G., Alsyne, M.W.V., & Choudary, S.P, (2016). Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You. New York, NY: Norton & Company, Inc.

[15] Australian Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade), (2018). E-Commerce in Thailand: a guide for Australia business.

[16] Martens, B. (2016). An economic policy perspective on online platforms. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies Digital Economy Working Paper, 5.

[17] Euromonitor (2018). Understanding global marketplace trends.

[18] Bloomberg (Aug 5, 2019). Amazon Squeezes Sellers That Offer Better Prices on Walmart.

[19] OECD (2019). Implications of E-commerce for Competition Policy.