What would happen to the Thai economy if the COVID-19 stays forever?

The new wave of domestic COVID-19 infections has impacted the Thai economy, slowing the recovery and increasing the risk that the country will struggle against the long-lasting pandemic. Krungsri Research has thus carried out a fresh analysis of the domestic impacts of the latest outbreak of COVID-19 on industry and households and the subsequent prospects for recovery. The results indicate that businesses connected to tourism, restaurants and transportation remain hardest-hit sectors, while income for unskilled workers will be more sharply reduced than will that of skilled laborers. However, middle-income earners and lower-income earners in urban areas will be the most severely affected and will have to endure the slowest recovery. In the coming period, recovery will not be spread evenly across the economy. Businesses and households will see significant variations in how quickly their situation improves. Worse, if the current outbreak is not suppressed, this recovery gap will widen and deepen, ultimately exacerbating pre-existing structural fault lines in the Thai economy. In Krungsri Research’s view, one response to this situation would be to facilitate the movement of production factors in the form of labor, capital and materials between industries and regions since it would help to reduce future economic losses and increase the economy’s growth potential.

The sudden discovery of the new cluster of infections at the close of 2020 has helped to trigger a reset in the improving outlook for the Thai economy, and although the authorities have used less strict, but more targeted, measures than they did last year, infection rates remain fairly high in economically important provinces that are home to a diverse but significant spread of activities, including hotels, restaurants, retail and wholesale businesses, and manufacturing. This has then served to put the brakes on the recovery and unfortunately, the economy is thus now being buffeted by a fresh range of problems.

These headwinds are now being transmitted across industries and over the short-term, this is adding to the range of negative effects being felt by workers and households. In light of these recent developments, an interesting question to pose is: How will the Thai economy be altered if COVID-19 remains a persistent threat? If this happened, in what direction would the economic center of gravity shift? In which industries would businesses remain profitable? And what should Thailand do to help still weak and fragile households and businesses pull through to better times?

Thai service sector is staggering under the heavy burden of pandemic-control measures

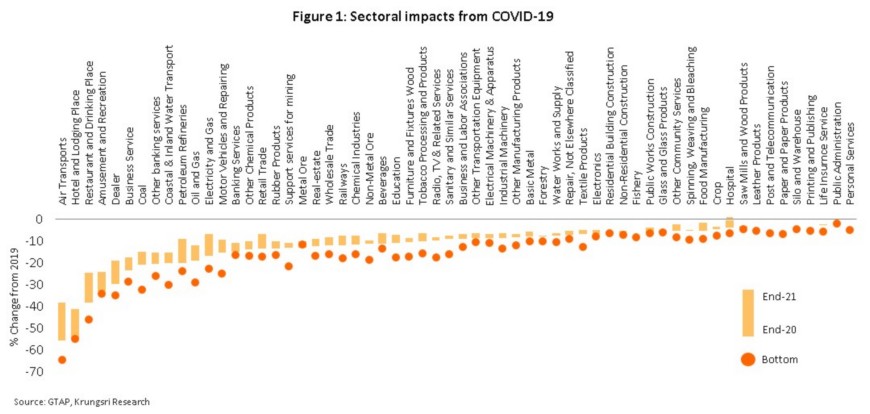

Controlling and suppressing the spread of COVID-19 is clearly the first priority in navigating this crisis, and this means that the government has had little options but to strictly limit international travel and to lockdown economically significant regions, even though this has had severe knock-on effects on industries (e.g., international tourism) that have hitherto been reliable economic growth engines. In addition, domestic consumption has also been temporarily restricted so although the public health benefits of these policies have been indisputably positive, they have had unavoidable and serious economic side-effects. To better understand this situation, Krungsri Research has therefore carried out analysis of the impacts of both the first and second waves of COVID-19 on different industries, and this confirms that tourism and the service sector are suffering the most, led by air travel, hoteling, and the restaurant industry (Figure 1). Through 2021, the overall picture will be one of recovery from the lows recorded in 2020 but despite this, in most areas, the sectoral output will nevertheless remain below its pre-pandemic level.

Domestic workers have suffered a drop in wages and a cut in hours, while unskilled laborers are most at risk of seeing their income decline

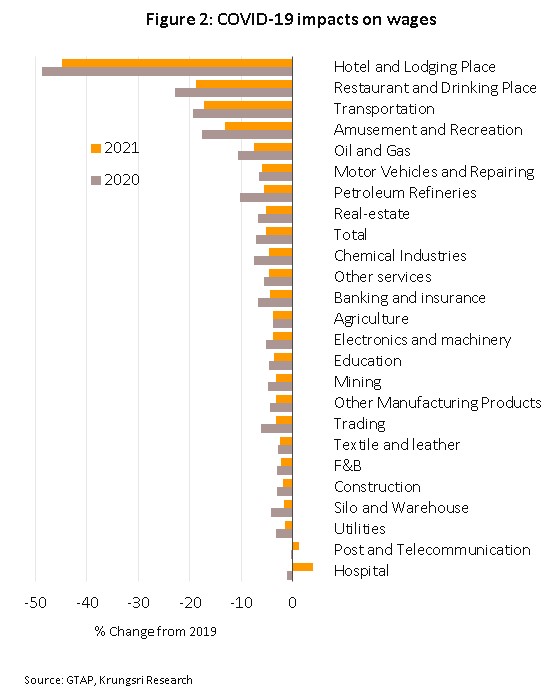

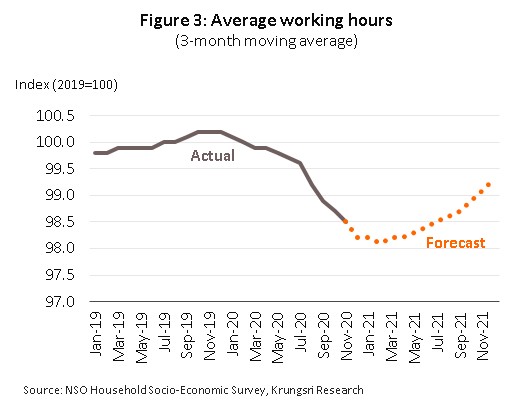

Although the effects of the pandemic vary by industry, they are tending to be transmitted to the workforce through the same mechanism, that is, business owners are responding to a weakening of income with cost-cutting moves that target staff overheads, most notably wage rates and hours worked. However, the extent of these losses is dependent on the negative impacts that COVID-19 has had on particular industries, and where 2021 wage-cuts are expected to be less than 10% of their pre-pandemic level, these are categorized as ‘weakly impacted’. Industries in this category include agriculture, construction and manufacturing (e.g., electronics, and clothing and accessories). On the other hand, highly impacted businesses are concentrated in the services and tourism sectors, where wage cuts run between 18% and 45%, with the worst affected businesses being in hoteling and other accommodation, travel, and restaurant. Although the proportion of highly impacted businesses is relatively low, wage cuts may be more extensive than is immediately obvious (Figure 2) due to the economic losses arising from the clustering of industries that are dependent on overseas demand, which then implies that the pace of domestic recovery will also be influenced by the intensity and impacts of the pandemic overseas. Beyond this, many business owners are trying their hardest to maintain payrolls, but the cost of doing this is that hours have been slashed, and overall, although the economic outlook will improve this year and many businesses should be able to start increasing workers’ hours again, they will likely remain below their level in 2019 (Figure 3).

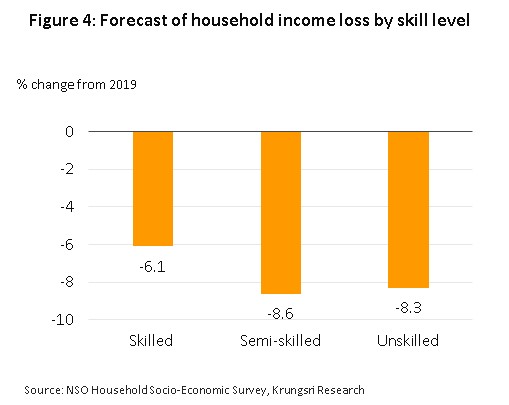

Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on the economy, flexibility and adaptability with regard to work is an important factor in determining the risk of an individual seeing his or her income fall, but Krungsri Research have shown that semi- and unskilled workers will see income fall by up to 8% relative to 2019 levels, and that a full 75% of workers fall into these categories (Figure 4), including those in the agricultural and construction sectors, cleaners, sale workers and numerous other jobs in the service sector. Several different factors lie behind these losses, including problems arising from work patterns that conflict with the requirements for social distancing and the effects of COVID-19 on particular industries, but given the cuts in hours and wages that they have endured, semi- and unskilled workers will be more heavily affected by this than others. Moreover, the Thai labor market will continue to feel the effects of this process for some time, which will undercut household incomes and pile further pressure on consumer spending power in the coming period.

Amid the general crisis precipitated by the pandemic, the urban poor are experiencing a financial crisis of their own

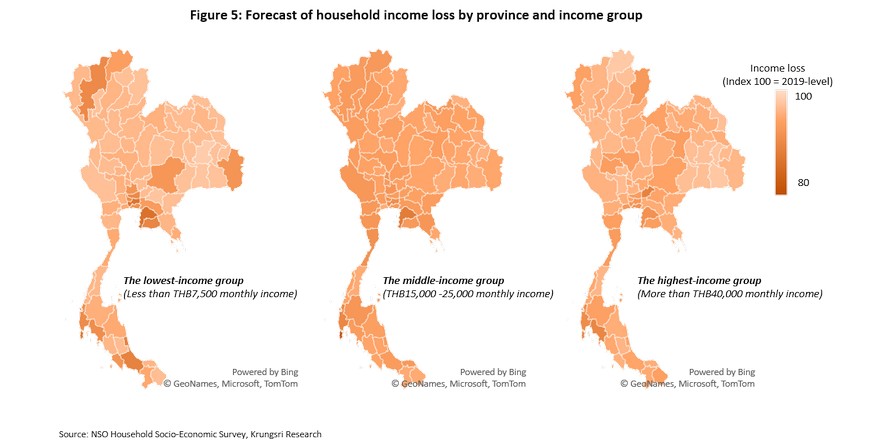

Among the many effects of the COVID-19 crisis has been its ability to shine a light on the depths of inequality in Thai society, and the sharply differentiated impacts of the pandemic on different income groups have served to throw the gaps between different segments of society into stark relief. To further understand this process, Krungsri Research has analyzed losses to household income on a province-by-province level, with provincial populations separated into groups corresponding to low-, middle- and upper-income earners. The results of this work show that middle-income earners have suffered the highest overall level of cuts to income by 7.6% relative to their pre-pandemic level, with this effect emerging across all provinces, while by contrast, high-income earners are the least badly affected, seeing their income drop by 6.6%. However, low-income earners (i.e., those earning less than THB 7,500/month) who live in economically-significant urban areas have had to endure the highest drop in income, and the worst affected of these are households in Chonburi, whose income is expected to fall by 12.7%, followed by those in Bangkok (-12.3%), Phuket (-12.2%), Chiang Mai (-9.8%) and Krabi (-9.4%) (Figure 5). With declines in incomes on this scale, many will be forced to look for new economic cushions to protect against the impacts of COVID-19 now and in the future.

Households with less financial buffers are most exposed to the loss of income

Even under normal conditions, the majority of Thai households lack savings or access to other buffers that can soften the impact of financial shocks and so are exposed to a fairly high degree of financial fragility, but the pandemic has significantly eroded even these minor abilities. Thus, as of the third quarter of 2020, Thai household indebtedness has now reached a historic high of 86.6% of GDP. This then comprises another rising risk that households will have to navigate as they attempt to pass through the COVID-19 crisis.

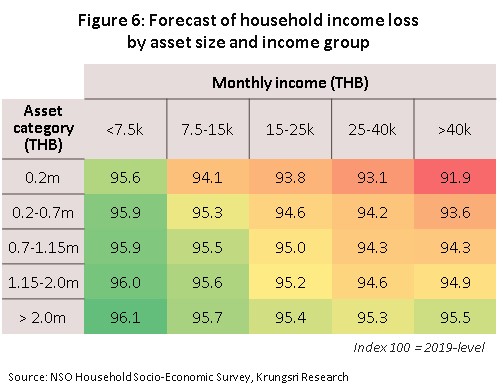

Additional analysis by Krungsri Research into the impacts of COVID-19 with regard to household income and wealth based on data drawn from the National Statistical Office of Thailand’s Household Socio-economic Survey shows that households with assets valued at less than THB 200,000 (22% of Thai households) will experience the most severe change in income, regardless of the latter’s level. This group’s lack of financial reserves and savings means that their ability to resist financial shocks is significantly lower than other groups, and so when crises occur, their impacts are sharper on poor households, who are less able to use assets to offset the resulting loss in income. On the other hand, households that have greater levels of wealth can better absorb and overcome reductions in income (Figure 6).

These results show clearly that Thai households are split into two distinct groups. Households that have a significant asset base will be more lightly affected by income losses, and although the economic effects of the crisis will be visible for some time, for these households, its immediate consequences will not be severe. On the other hand, households with only limited assets were already facing a precarious economic situation but the COVID-19 crisis has inflicted disproportionately heavy losses to income on this group. And, if the crisis is extended and the pandemic is not controlled domestically and internationally, the failure to return to normalcy will slow recovery in the Thai economy and delay even further the rebound to pre-pandemic levels of income for asset-poor households.

Household consumption would rebound moderately in 2021, but remain below pre-pandemic level

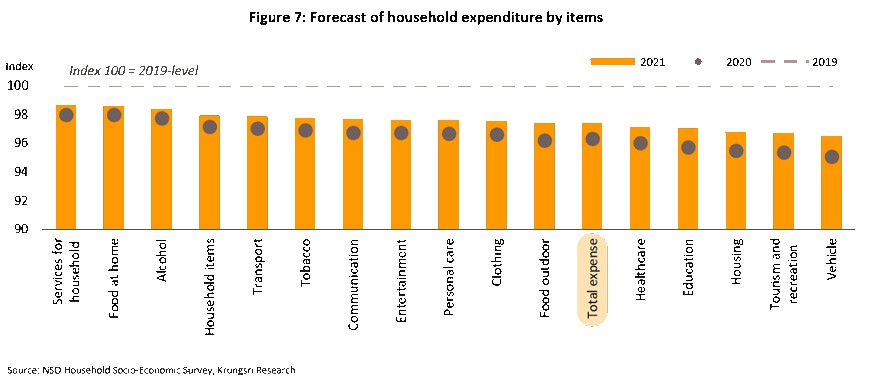

The continuing fragility of the domestic economic recovery is a significant contributor to the factors weighing on household incomes and purchasing power, and as long as incomes remain depressed, it is natural that levels of consumption are adjusted in compensation. Through 2021, this situation will slowly evolve, and household consumption will tend to rise at moderate rates, supported by ongoing government efforts to sustain household finances and boost expenditure, which the government has been doing through the ‘Half-half co-payment’, ‘Shop and Payback’, ‘We Stand Together’ and ‘We Travel Together’ programs. In addition, it is hoped that the rollout of the vaccination program will improve the economic outlook further through the second half of the year, but despite this support for the economy, it is likely that consumption will still not return to its 2019 level by the end of the year, and Krungsri Research estimates that, overall 2021 household expenditure will remain 2.5% below its pre-pandemic level (Figure 7).

Considered by category, expenditure on tourism, vehicles, and accommodation showed the greatest shortfall in 2020, and although these categories are heavy contributors to high-income earners’ consumption basket, the economic situation remains highly volatile, and this is weighing on recovery and a rebound in expenditure on these goods. This is especially the case for spending on tourism, which has been devastated by the continuing strict controls on international travel and weak domestic spending, and sadly any improvement in the situation is still only a remote possibility.

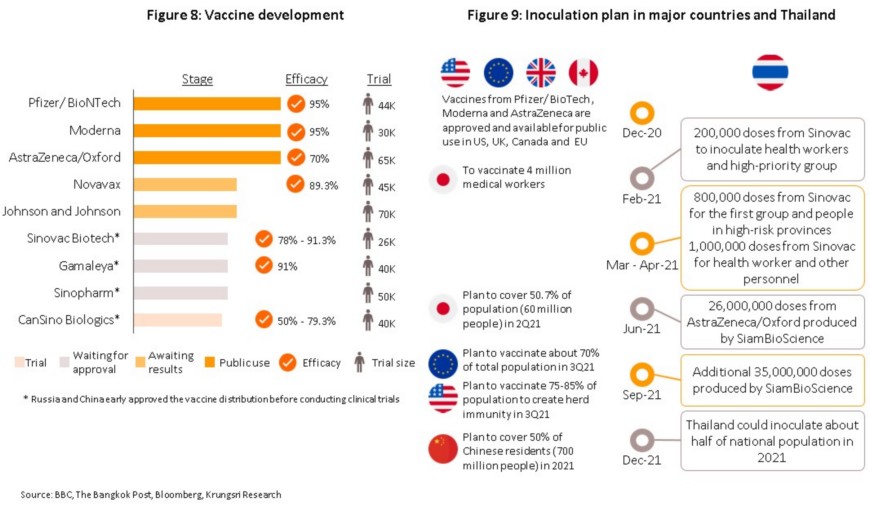

It should be noted that the analysis outlined above is predicated on the assumption that the new wave of COVID-19 infections is brought under control during February 2021. However, this latest outbreak is proving hard to suppress and there are two reasons to suspect that the new wave may last for longer than the initial burst of cases. (i) international experience shows that it is extremely easy for repeat waves of infection to erupt, and (ii) herd immunity may arise through two ways, either through mass infections or through mass immunization. In the latter case, Thai authorities expect to have at most half the population vaccinated by the end of 2021, and while the efficiency of the vaccines runs in the range of 70-91.3% (for the Sinovac and AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines), this may be reduced as COVID-19 spontaneously evolves into new variants. Thinking more generally then, if the risk of a re-emergence of infections persists, it is thus worth considering the question of what the consequences would be for the Thai economy, Thai industry, and Thai households if COVID-19 were never eradicated.

Krungsri Research has identified 6 areas where the Thai economic landscape would change, if COVID-19 stays forever.

- Expenditure on healthcare and public hygiene would rise as the public sector was called on to shoulder a greater share of healthcare costs, while private-sector and household spending on disease prevention would likewise strengthen.

- Measures to suppress the spread of disease and restrictions on travel would reduce the overall level of economic activity, especially those that involved mass public gatherings, such as exhibitions, sporting events and concerts. International travel would also be severely impacted over the long-term by the need for stricter travel controls.

- Business costs would rise due to the need for greater spending on disease prevention. In addition, although most businesses could adapt to the need to maintain social distancing measures, in many cases operations would have to be overhauled, and this would add further to overheads, especially for businesses that depend on a high degree of face-to-face contact.

- Productivity would decline. Research carried out by the Bank of England and Stanford University[1] shows that during the epidemic, labor productivity has worsened by around 10%, and will likely remain around 2% lower than its pre-pandemic level even once the pandemic has been brought under control. This surprising result is attributed to a combination of lower output and higher business overheads.

- Business adoption of technology would accelerate. Businesses would be especially eager to speed up their use of digital technology as a way of meeting the challenges posed by evolving customer needs and behaviors. Businesses would also look to technology as a means of facilitating the changes to working practices that would be necessary to stay afloat through a more prolonged crisis.

- Labor and assets would be reallocated between locations and industries. As has been shown, the COVID-19 crisis has differentially affected households and industries, and an extended pandemic would worsen these differences, resulting in a movement of resources (labor, capital and materials) from industries that are more seriously affected to those that have been less disrupted. Geographical differences in impacts would also tend to precipitate the spatial redistribution of labor.

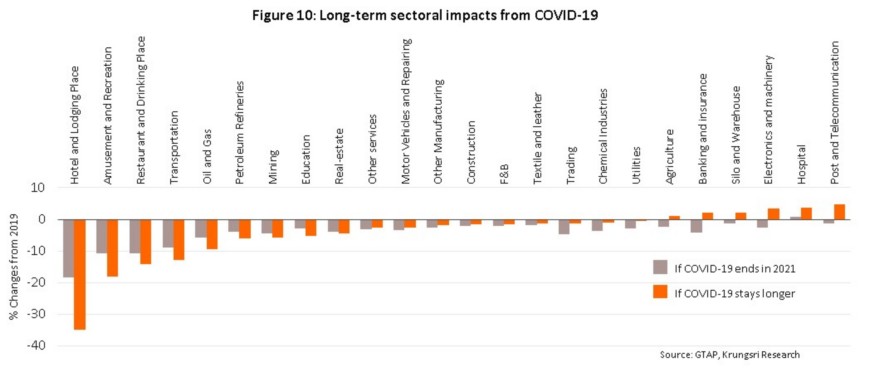

Based on the assumptions given above, Krungsri Research has used a general equilibrium model to assess the impacts on industry and the economy of a prolonged pandemic, and this shows, the economic costs are more substantial and the length of time that it would take to return the economy to better health lengthens substantially. However, businesses would adjust to these changed circumstances by reallocating factors of production from areas of the economy that were more heavily affected to those that had been touched more lightly by the pandemic, and this analysis then allows one to see more clearly which industries win or lose. In the case that COVID-19 is brought under control in February 2021, the Krungsri Research analysis shows that total output will decline by 4.7% relative to its pre-pandemic level but with the COVID-19 staying forever, the slump in economic activity would bring this up to a fall of 6.4%. Due to the necessity of imposing and maintaining strict social distancing measures, the worst affected industries would be those connected to tourism, restaurants and passenger transport. However, against this, output by the IT and telecoms, healthcare and electronics industries would still tend to return to their pre-pandemic levels of activity.

The effects of COVID-19 on the economy and an uneven recovery

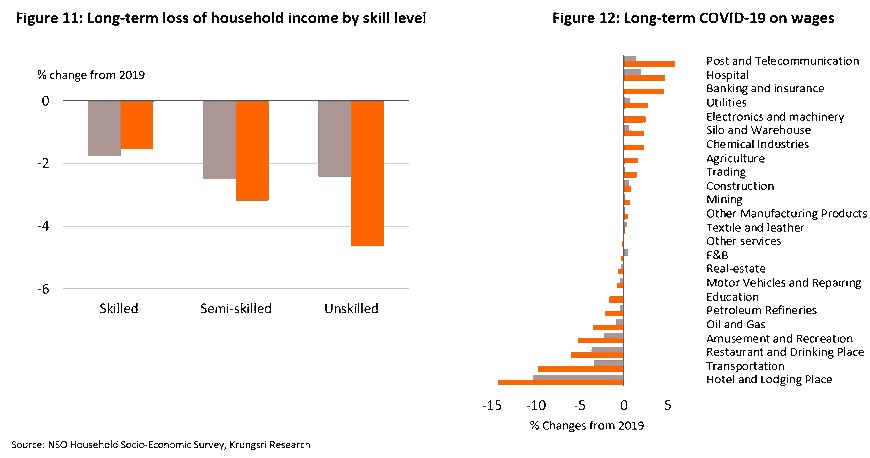

As described above, the COVID-19 crisis has amplified the structural weaknesses already affecting Thai households, and if the pandemic is extended, these problems would tend to worsen. Analysis carried out by Krungsri Research that differentiates these latter impacts on the basis of households’ income, location, skill level (i.e., whether skilled or unskilled workers), and industry of employment has revealed three important findings.

Finding 1: The differential impacts on skilled and unskilled workers are amplified, and the income of unskilled workers will recover slower. Thus, the long-term loss in income for this group increases from a drop of 2.4% to one of 4.6% if the pandemic is not suppressed in the immediate future. By contrast, skilled workers see no corresponding worsening of their income (Figure 11).

Finding 2: The differential impacts on income by industry widen, with workers in tourism, restaurants and passenger transport seeing their incomes suffer disproportionately heavily relative to other parts of the economy (Figure 12).

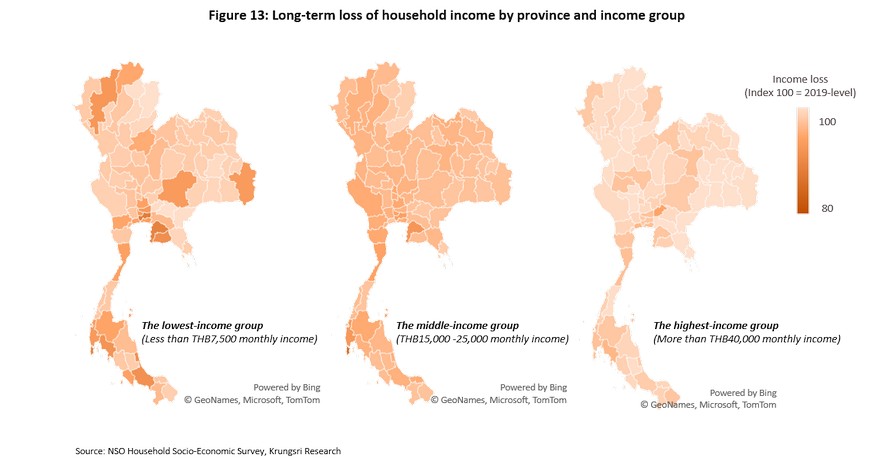

Finding 3: Under a prolonged pandemic, the urban poor and middle-income earners nationwide remain the most seriously affected demographics, and the differences in impacts between these groups and others widen. Figure 13 highlights these variations in the speed of the recovery for different income groups in different areas, showing that even with an extended crisis, high-income earners enjoy a rapid return to the status quo, while the middle-income group remain seriously impacted and the urban poor’s situation worsens.

Allowing the reallocation of resources could alleviate the pandemic’s impacts and reduce the recovery gap

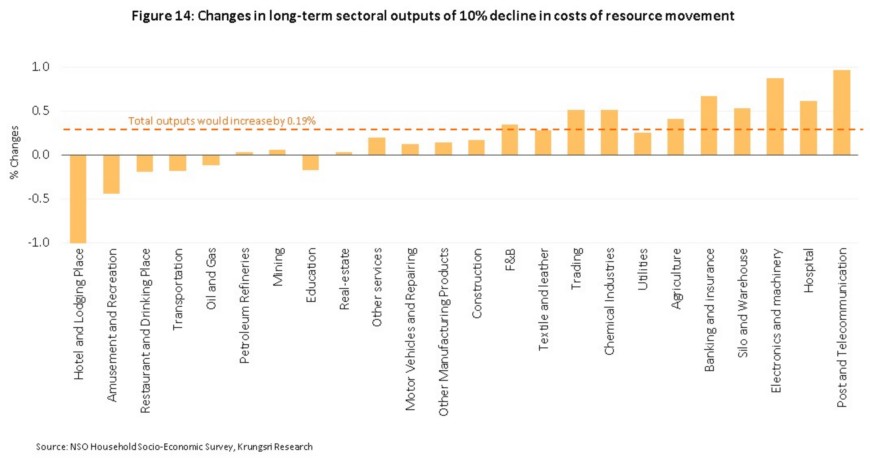

Although the COVID-19 crisis has triggered a decline in overall economic activity, with a prolonged pandemic, individuals and businesses would begin to adapt to the new situation, and one important part of this would be the movement of resources (labor, capital and materials) from more badly affected/less efficient industries to those that were less badly affected/more efficient. Krungsri Research’s analysis of this situation shows that

if the movement of labor and resources between industries were eased (in the test scenario, the costs of this movement are assumed to be reduced by 10%), this would raise total output by 0.19%, thus supporting growth in many industries. In addition, this intervention would also lead to a rise in average wages of 0.24%, thus underlining the fact that optimizing the allocation of resources will play a significant role in offsetting the impacts of COVID-19.

In conclusion, if the authorities fail to eradicate COVID-19 and it instead becomes a persistent feature of life, this would not just slow economic activity but would also exacerbate the preexisting inequalities between Thai households and delaying and pushing out recovery even further. However, as has been shown, increasing the ease with which resources are moved between industries would help to offset these problems. This might be achieved by establishing a platform that would allow workers to look for new positions or to train and acquire new skills, thus increasing labor market flexibility and widening the range of employment options open to individuals. Moreover, increasing the growth potential of new and existing small businesses could be achieved by helping them gain access to sources of finance, while relaxing regulatory requirements such as those related to tax and company ownership by investors would also help to increase investment. Implementing measures such as these to facilitate the reapportioning of factors of production to higher-potential businesses would then help to bring forward Thailand’s economic recovery.

The author would like to thank Kusalin Charuchart for her assistance in preparing this paper.

[1] Bloom, Nicholas and Bunn, Phillip and Mizen, Paul and Smietanka, Pawel and Thwaites, Greg, The Impact of Covid-19 on Productivity (December 21, 2020). Bank of England Working Paper No. 900