Many different types of goods may function as security for a loan, from the goods traditionally used as collateral in financial institutions worldwide, such as land, houses and other properties, to property such as cars and financial goods (e.g., savings accounts) and more innovative and unusual items, though the use of these tends to be limited to only certain lenders. For example, Knight Frank Finance in Britain once accepted a thoroughbred world-champion showjumping horse as security. It was claimed that the horse had a value of GBP 300,000 and was used to secure a loan of GBP 120,000 (or 40% of the collateral’s value). In Italy, the bank Credito Emiliano has also accepted a quantity of Parmigiano Reggiano (or Parmesan cheese) as collateral, while in Hong Kong, Yes Lady Finance has authorized loans against brand-name handbags.

The extremely wide range of collateral in use can, however, be classified into the following major groups.

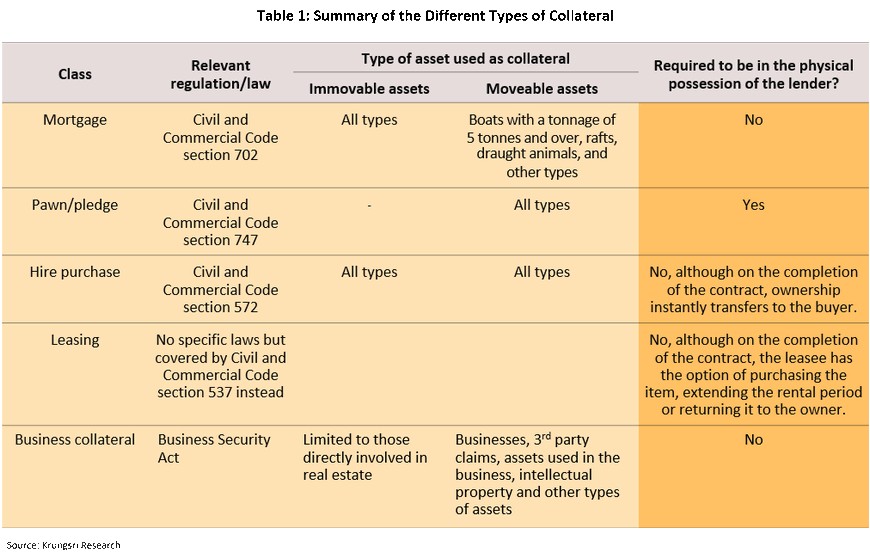

In Thailand, there are two legal structures governing the use of loan collateral; the Civil and Commercial Code, which has been enforced since 1925, and the Business Security Act B.E. 2558, which was written into the statute book with the intention of expanding and diversifying the range of property that could be used to secure business loans. The key features of the Thai regulatory framework are given below.

has been in effect for almost a century, though it has been constantly revised since its first introduction in 1925, most recently with the passing of the 2014 Civil and Commercial Code Amendment Act (No. 20). Although the Code has a total of 6 books3/ and 1,755 sections, those relating to the use of collateral can be summarized as follows:

It is worth noting that in practice, leasing, which is another type of arrangement, can be very similar to hire-purchase. Under lease agreements, an item is rented and on the completion of the pre-agreed rental period, the renter then has the option to buy the item at a pre-agreed price. However, leasing is not covered by its own legal framework, but rather it is considered to fall under the general provisions for rental agreements (Book III Specific Contracts of the Civil and Commercial Code, Title IV Hire of Property, Section 537-571) combined with the Principle of Freedom of Contract.

became law in 2015, and was drafted with the intention of expanding the possibilities open to enterprises (or ‘security provider’ as per the Act) and allowing them to use a much wider range of assets as security against loans agreed with financial institutions (or ‘security receiver’). Thanks to the new law, borrowers may now register these assets as collateral electronically with the Department of Business Development (part of the Ministry of Commerce), without their needing to be handed over to creditors.

In theory, the Business Security Act increased debtors’ flexibility in using collateral, especially for those that do not have the large immovable assets registered in their own name that are required under the earlier regulations as collateral. Following the passing of the act, borrowers have been able to secure loans against a much wider range of business asset classes, including items as varied as the business itself, food carts/stalls, shops, rental agreements, machinery, items in stock, raw materials, forests and even intangible goods such as intellectual property, trademarks, patents and copyrights. This flexibility also increases borrowers’ ability to pay, as they can still utilize their asset in the business operation.

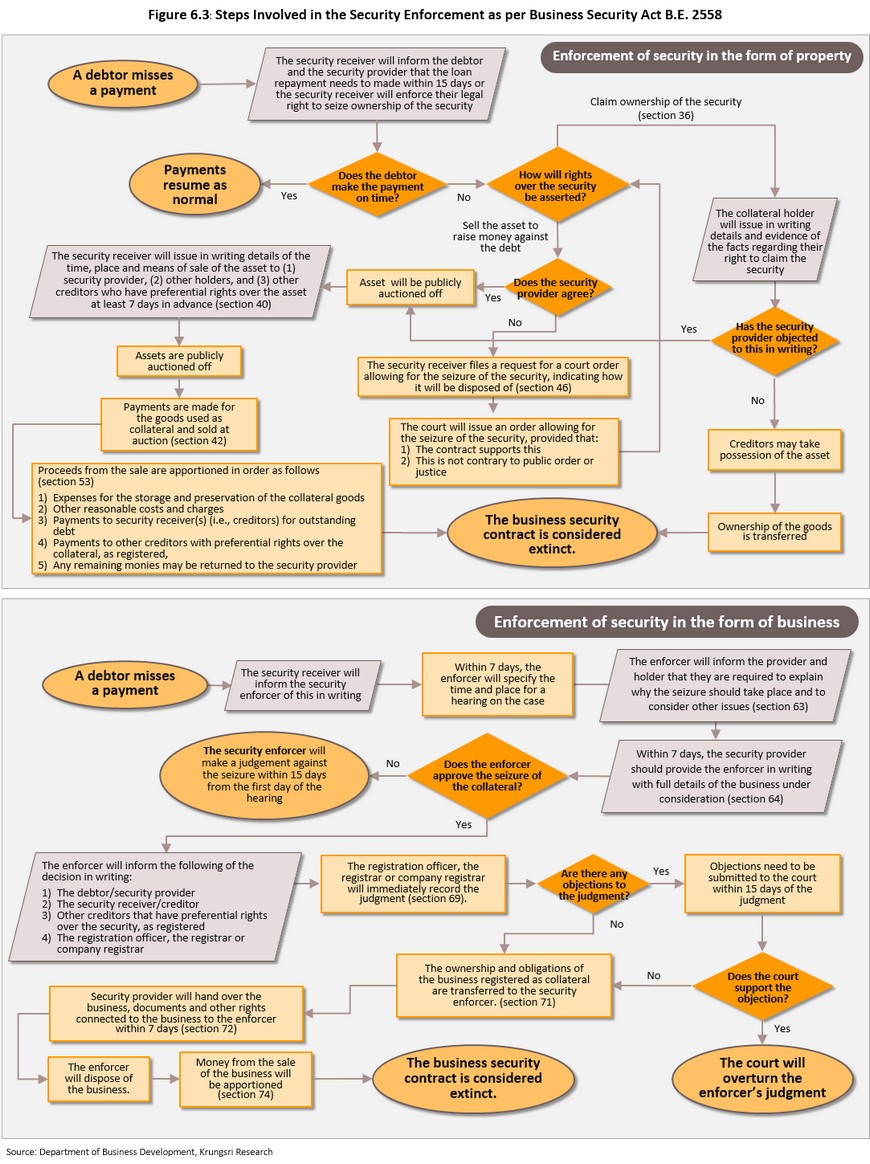

In addition, if the debtor defaults, creditors may take control of the loan collateral without the need of a court order. Even though this is contested by the debtor, the legal process provided for in the Act is less time-consuming than that required under the Civil and Commercial Code (Orawan Gaysorn, 2017).

The use of collateral in the Thai financial sector

Prior to 1997, issuing loans in Thailand was heavily dependent on the use of collateral (the industry took the form of collateral-based lending)[5] and lenders, especially commercial banks, would typically make loan decisions based largely on the quality of the collateral against which the loan was secured. Thus, potential borrowers with access to higher-quality collateral would be treated as good credit risks, with banks generally taking ‘higher-quality collateral’ to mean real estate of all types. Indeed, it came to be said that the rule for loan issuance was simply ‘Bring us your collateral, and you can take away your loan’ or even just ‘No land, no loan’[6], such that the business of approving bank loans became remarkably similar to how pawn shops operate, with the result that putting up high-quality collateral came largely to displace other forms of credit assessment, such as analyzing the project for which investments were being sought, or of assessing the borrower’s creditworthiness[7]. In this situation, the function of loan guarantees and collateral leaned heavily towards assuring lenders that their loans were sound and their losses would be minimized (i.e., reducing creditors’ potential LGDs) at the expense of overcoming problems resulting from asymmetries of information[5].

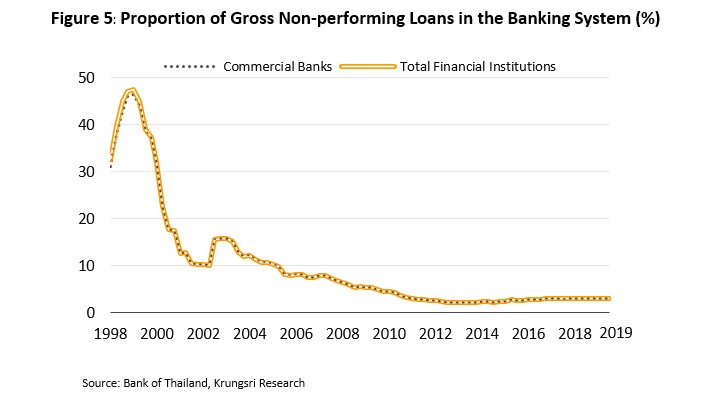

This situation changed with the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, which rocked the Thai banking system and led to a shake-up of the whole financial sector8/. These reforms focused especially on strengthening financial institutions, shifting industry oversight from a focus on compliance-based regulation to one that was much more centered on a risk-based approach9/, and increasing the financial sector’s ability to utilize information by establishing a number of new agencies, such as National Credit Bureau10/. However, major sectoral changes related to managing credit risk had to wait until 2008, when the Bank of Thailand (BOT) introduced rules for calculating the banks’ exposure to credit risk through the use of an internal ratings-based approach (IRB).

On the basis that this reflects the real risk to the lender, the IRB approach evaluates credit risk by calculating the value of expected losses, which then allows banks to set aside sufficient loan loss provisions to cover these. As they looked to cut their exposure to bad debts, this regulatory change then had the consequence of encouraging banks to much more carefully assess the risk of individual loans and borrowers, both with regard to the borrower’s ability to repay the loan on time and how they intended to cover the payments. These changes helped banks reduce the probability of debt default, banks’ potential losses in the case that such defaults do occur (their LGD) and the risks connected to the banks’ total exposure to unrepaid debt (the ‘exposure at default’, or EAD). Banks increasing care over how much credit they released and who they issued it to is reflected in the total rate of non-performing loans (NPLs) within the overall financial sector, which fell significantly following these changes. These reforms have therefore helped to protect the financial system from the kind of systemic risk that arose in the pre-crisis period as a result of reckless lending and loose appraisal of risk and collateral levels. (Details of the importance of collateral in the twin situations of expected and unexpected loss are given in Box 1 below).

Following the introduction of the Bank of Thailand’s Financial Sector Master Plan Phase II (2010-2014), the financial sector ramped up its efforts to extend access to financial services across the Thai population, while action by the public sector also emphasized the importance of improving the ease of doing business. In terms of accessing credit by business, all parties connected to the process attempted to make real progress in widening the range of collateral and loan guarantees that could be used, through for example, the passing of the aforementioned Business Security Act and the Bank of Thailand’s issuing of regulations covering digital lending. The latter allowed for the submission of digital information in support of loan applications, such as payments for utilities (water, electricity, telephone, etc.) and records of sales and purchases of goods online, and as a result, opportunities have improved for small businesses looking for credit, even when they lack assets such as land or buildings to use as a collateral[11].

Using Collateral in practice

Although the regulatory environment now allows for a large number of different types of asset to be used as collateral, in practice, the majority of loans issued in Thailand continue to be secured against the same kinds of asset as were used prior to the reforms, and in particular, land is favored as an especially high-quality collateral. This is at least partly because in the Thai context, market mechanisms help to ensure land and other types of immovable asset meet the four aforementioned criteria of ‘good collateral’ more fully than do other types of asset.

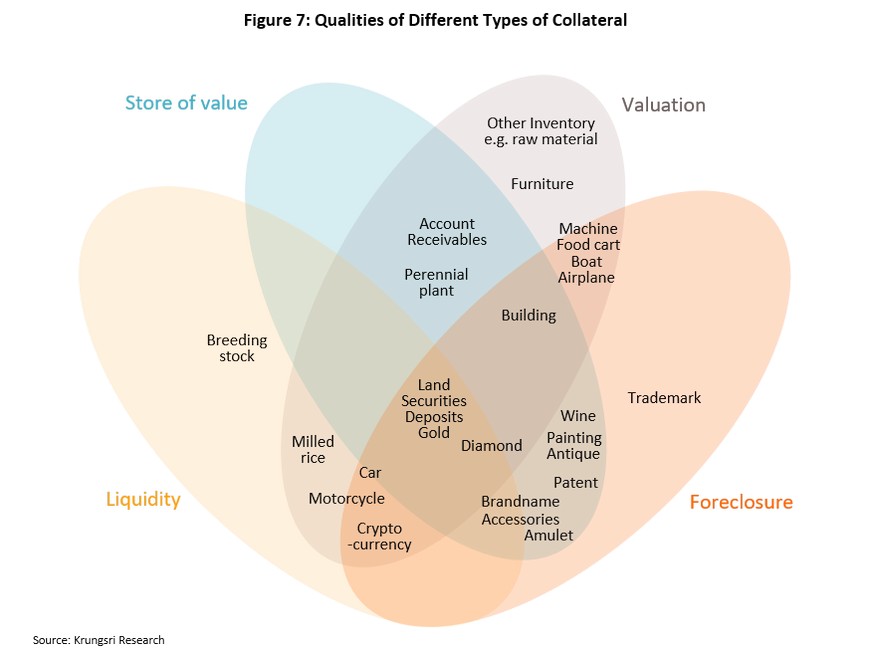

- Valuation: Land values may be ascertained with a reasonable degree of accuracy by reference to sales on open markets, while trained and licensed appraisers are also able to provide accurate judgements of the value of land and buildings. This differs from the values of other, more specialist types of goods, such as (in the case of Thailand) amulets, Buddha images and other sacred objects, and forestry. Although these items may command a high price, deciding what this value is outside a market relies on specialist knowledge, while the goods will also likely be of interest to only a small market of buyers and this makes it harder to determine a reference price. Given this, banks that accept more unusual items as collateral may need to shoulder the additional costs incurred in seeking out reliable expert appraisals, and these costs may increase in the event that the goods are seized and sold on the open market.

- Value retention: The fact that the supply of land within a country is strictly limited tends to raise its value over time, while the depreciation in value that may happen during a recession is usually only small and temporary. This differs from other items, such as stock or machinery, which may see a sharp decline in value during a recession. Land also benefits from not (except in extreme cases) being depreciated or degraded, which again differs from items such as buildings, cars, and rice stocks.

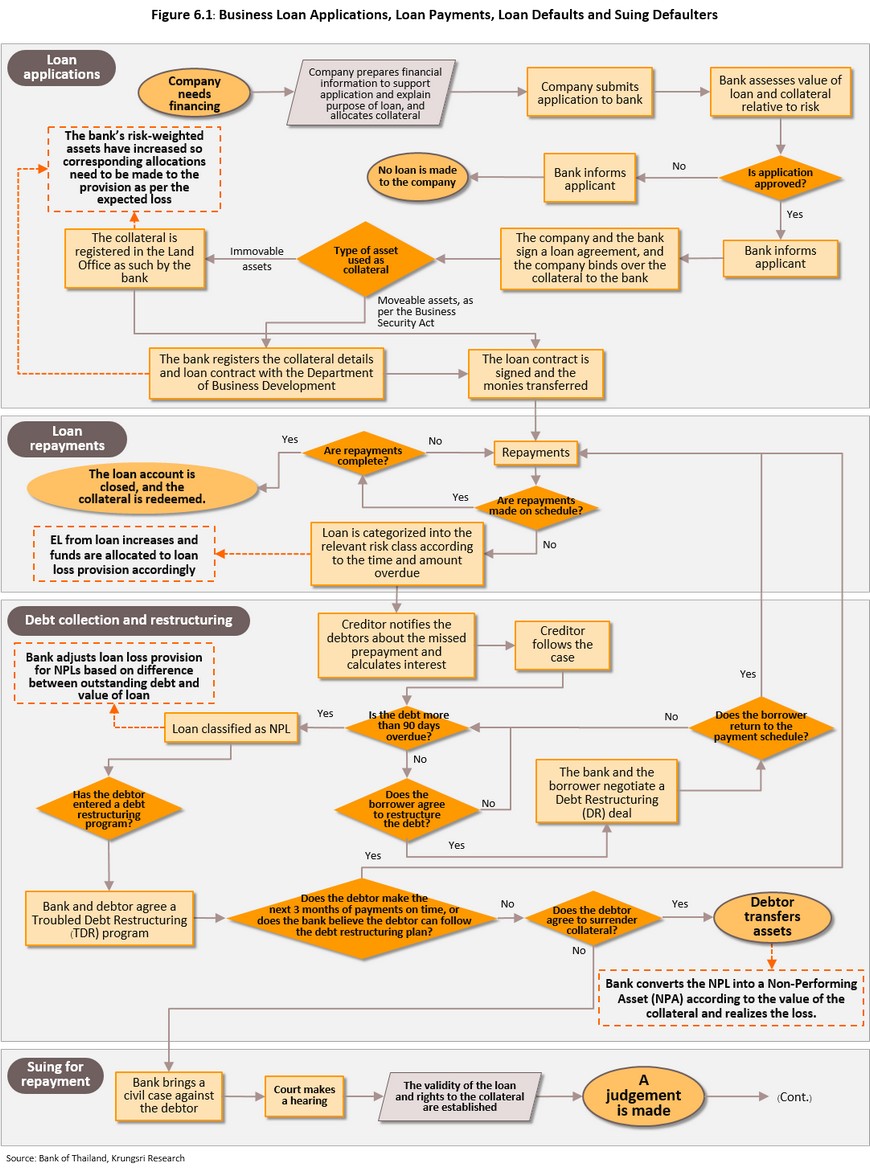

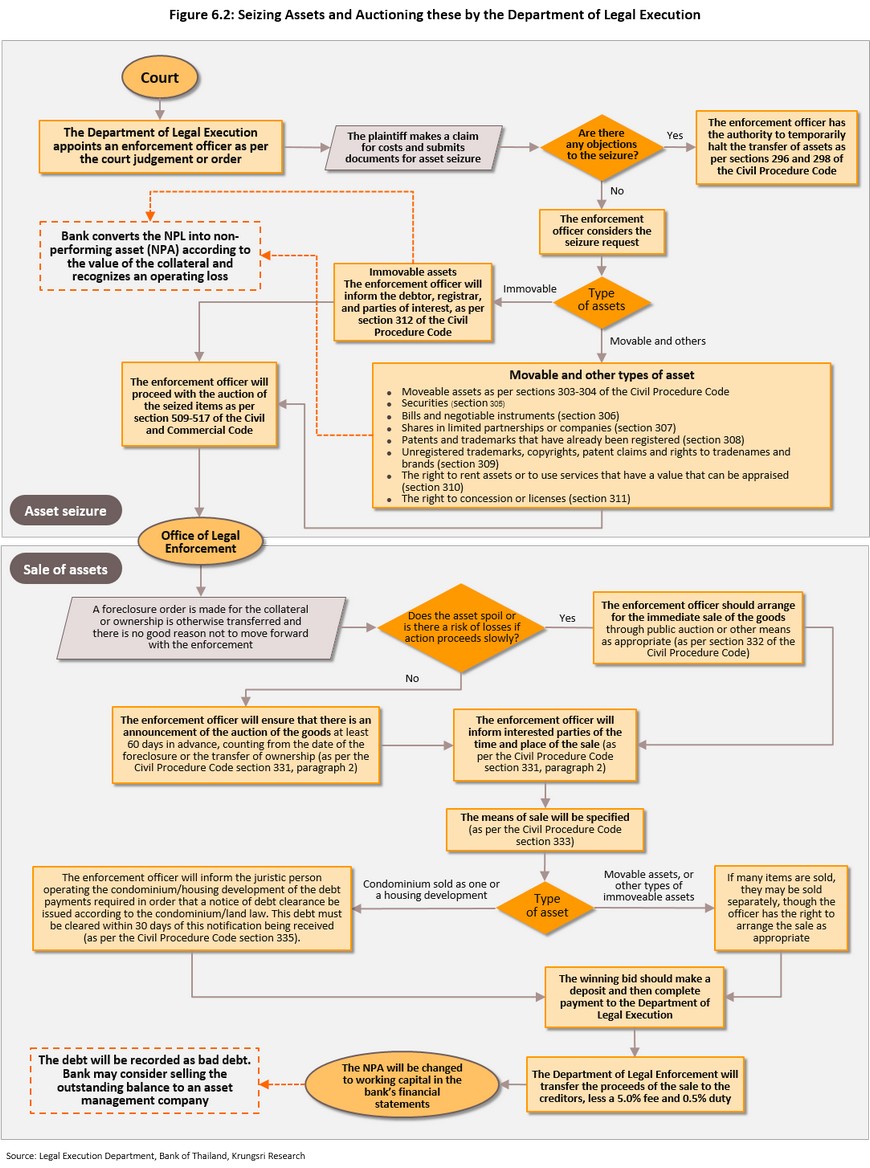

- Foreclosure: Land is a type of immovable asset and as such it is clearly not possible for it to be moved or relocated, while it is relatively straightforward to reassign ownership. Land also has advantages as a form of collateral since its ownership carries with it essentially no maintenance costs, which may become a factor if there is a prolonged court battle over ownership and the item then needs to be auctioned off by a lender looking to recoup their losses. With land, owners do not have to contend with fees for maintenance or storage, or worry about stock losses, destruction, transportation, or even substitution with another good. In addition, although it is true that the new regulations allow lenders to accept a much wider range of assets as collateral, in the event of a default, these remain the property of the borrower until a court order is issued in favor of the creditors, and working through the various stages of the legal process, from filing a case and enforcing a judgement to selling seized goods and recovering costs[12] (figures 6.1 and 6.2) can take at least 2 years, and in some cases, it may take as much as a decade for lenders to complete the process (the longest length of time permissible in law)[13]. As mentioned above, it is true that the Business Security Act has reformed the process of seizing collateral and this is now accomplished more rapidly than under the regulations provided for in the Civil and Commercial Code, and indeed, it may be possible to avoid going to court at all (Figure 6.3). However, banks might remain unwilling to accept guarantees made under the new business collateral rules since even in the shorter time it takes to recover these goods, lenders are open to the risk that during this period, the goods may depreciate substantially in value, whether that be because of natural declines in their quality or from a lack of care, attention, maintenance and so forth. Thus, it may be the case that owners who have defaulted on loans, aware that there is a strong possibility that lenders will forfeit their goods, lack the motivation to take good care of them. It may also happen that goods placed as collateral may decline in quality to a point where they lose both their use and financial value. For example, with many types of machinery, if some parts are removed and sold separately, the value of the machine as a whole will rapidly plummet, while over the course of a extended court case, goods may also become outdated or they may be superseded by new models and production may cease, which would then likewise cause the value of these to decline dramatically. In contrast, land is largely immune from these types of consideration.

- Liquidity: Because of the many functions served by immovable assets such as land, there is generally a relatively large market. This situation is significantly different from the market for, for example, much second-hand machinery, which may be designed for very specific purposes and so auctioning off these kinds of repossessed goods is considerably harder. Given this, although these goods may have high value for the borrower, for a lender, their value is likely to be much lower. For commercial banks, the requirement to sell seized goods within 5 years[14] imposes another cost that has to be managed, and so banks have a marked tendency to prefer collateral that can be converted into liquid assets rapidly (e.g., land) over other types.

Looking at these four qualities, it is clear that lenders will prefer collateral that display these most fully, that is liquid financial assets such as securities and money on deposit, followed by land, and then by other types of asset that may not meet all four criteria quite as well, e.g., buildings, cars (which meet three of these criteria), machinery, payments from trade debtors (which meet two) and business stock (which meets only one, that of having an easily appraisable value). Thus, with the exception of liquid financial assets and gold (which carries some additional storage costs), it is only land that can serve fully as good collateral (Figure 7).

In addition, for commercial loans, banks tend to prefer collateral that is a core asset of the business (e.g., a factory or office that is essential to the main business activity) over non-core assets, such as the home of a business owner or their cars, since the former are the means by which the business generates its income. In addition, taking core assets as collateral helps to prevent these being used to secure other loans[15] . Lenders take this position because the relative importance of core and non-core assets can open them to higher levels of risk, especially in situations where a debtor has loans from different creditors. In this case, if a borrower experiences financial problems and has difficulties making all their repayments, they will be forced to pay these in order of importance, and borrowers in danger of defaulting are very likely to consider loans secured against core business assets as having the highest priority because allowing these to become delinquent may further imperil business income. Given this, loans that are not secured against core assets are at higher risk of delayed or non-payment.

Despite these broad tendencies, lenders and especially commercial banks will tend to show individual preferences for the types of collateral that they accept, as well as the exact purposes that they expect the collateral to fulfill. Their choices will depend on the level of risk that they find acceptable as well as their expertise in individual markets. Thus, banks that are relatively risk-tolerant may decide to accept patents and copyrights. Those that have intimate knowledge of the real estate market might be keener to take land and buildings as collateral, while banks that focus on the tourism industry might be more willing to lend to players in this market in exchange for security in the form of land and buildings belonging to, for example, hotels.

The history of alternative types of collateral shows that in addition to their not being widely used, the value of the loans secured against them remains small relative to the value of new credit guaranteed against more traditional assets, and this reflects the hesitancy lenders continue to show in accepting non-standard collateral. This is partly because normally, lenders will not loan to the full value of the collateral because they need to protect against the risk of depreciation in the value of these assets if the collateral has to be seized and auctioned off in the future, while they must also take into account the additional costs involved in recouping loan losses. The latter is colloquially referred to as a ‘haircut’, while the proportion of the value of loan to the collateral that secures it is called the ‘loan-to-value’ (LTV) ratio. Normally, the LTV ratio will be less than 100%, although different types of collateral will generally carry their own LTV rates. Loans secured against land often have a higher LTV than do loans made against other types of collateral since the prices realized for land tend to increase over time, while the value of other assets (especially depreciable assets) may well decline. In addition, the value of some other types of asset is especially susceptible to changes in the business environment and the economy, and because the process of foreclosing on debt defaults can be very lengthy, there is a risk that the value of collateral may decline further. Indeed, as stated above, the situation can be worsened if debtors are convinced that they will forfeit their assets to a lender, they will be disincentivized to look after them, accelerating the likely impact of time on value to the point that some kinds of asset may become entirely unusable. This will then naturally add to lenders’ costs in the event that debts become delinquent, and as such their LGD will rise. Because of this, assets that lose value rapidly play only a subsidiary role as loan collateral, though while these may not be used to calculate lenders’ risk, they may still find a function in increasing the cost to borrowers’ of allowing loans to go bad.

Can traditional types of collateral still be used in the new economy?

As we have seen, banks tend to use high-quality collateral as a way of judging the quality of the loan that it secures, and by doing this, they help to reduce their exposure to credit risk. Unfortunately, this stance tends to encourage unintended side-effects. If banks continue to insist that loans must be secured against high levels of collateral, especially if they continue to favor traditional types of collateral while overlooking newer, alternative forms, they may inadvertently harm the business sector. This attitude to the release of new credit poses a particular danger to SMEs, which are both an important part of the wider economy and, at the macro-level, a significant determinant of the health of the financial sector, and so banks’ attitudes may ultimately be self-defeating.

1) SMEs may be locked out of the formal credit system because of their limited access to the type of collateral preferred by banks .

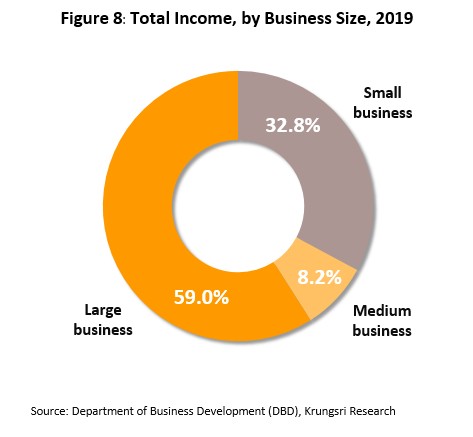

The Thai economy is marked by the large number of SMEs that comprise the majority of players in almost all industries, and their incomes account for around 40% of the total business income (Figure 8). Unfortunately, because they often lack access to the collateral required by banks, a significant number of these players encounter problems accessing credit. Moreover, a large number have been in operation for fewer than 3 years and so their financial history is insufficient to demonstrate that their business can thrive in both favorable and unfavorable conditions. Because of this, banks may ask SMEs to demonstrate their ability to repay a loan by instead putting up collateral. Unfortunately, in the absence of extensive company accounts, lenders are likely to expect SMEs to secure their loans with more extensive guarantees than is the case with large corporations[5],[16]. If SMEs are locked out of new credit, they may then encounter problems at all stages of their business, from startup to expansion and pulling through when cashflow is temporarily tight. On the other hand, if SMEs can indeed get access to new credit, lenders will often take the view that these loans are risky and so the cost of borrowing that SMEs have to shoulder is often higher than for bigger, more established players. At the macro level, these factors then place obstacles in the way of SMEs’ development, preventing them playing a fuller role as drivers of economic growth.

2) Modern businesses may own extensive intangible assets but the persistence of traditional lending models hinders access to credit

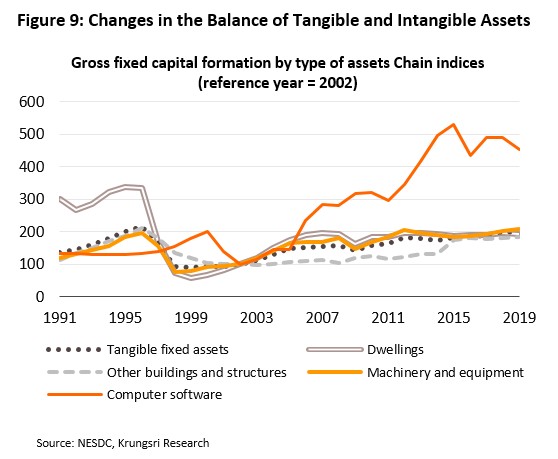

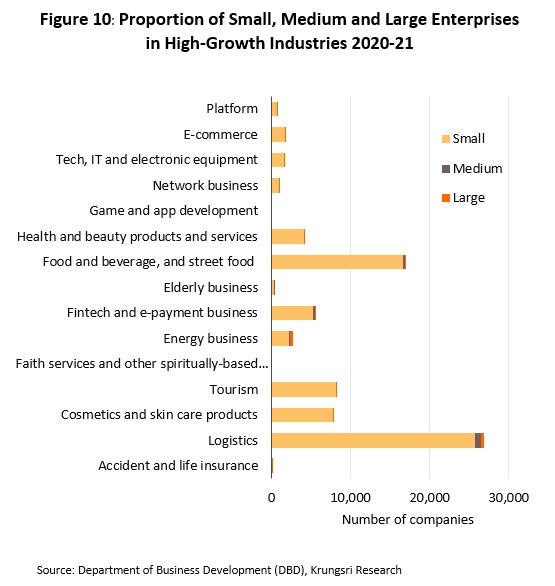

Much of modern business is developing in ways that sharply differ from earlier business models, both with regard to operations and factors of production. In many new industries, value is increasingly being built through the use of big data and analytics in developing industrial automation and robotics, or to the development and application of intangible assets, such as computer software and online platforms (Figure 9). Thus, many startups have reached the stage of generating incomes that rival those of vastly bigger and more established companies, but the entrepreneurs involved have worked from home with a skeleton staff and little else other than a handful of computers. As elsewhere in the world, these shifts in the economy are being seen in Thailand, and most recently the Department of Business Development has declared its stars of 2020 as being platform businesses, e-commerce players, network providers, game and application developers, and providers of logistics services, and the majority of these are new industries that are generally home to small businesses (Figure 10). Beyond this, in almost all industries, there is also a revolution underway in how businesses operate, and players that are likely to see the greatest growth in 2020 and 2021 will generally be those that are linked to the development and application of artificial intelligence (AI) and 5G networks and applications[17], to the use of big data and analytics in developing industrial automation and robotics, or to the development and application of other types of breakthrough technology, such as autonomous vehicles and smart homes. Distribution online/e-commerce is also rapidly rising in importance, as is the growing tendency to use virtual and augmented reality to extend the reach of product presentations to a much wider range of consumers[18].

Given the kinds of activities that are going to be successful in the coming period, one can see that in many cases, compared to traditional conceptions of business, modern industry operates in fundamentally different ways. Whereas in the past, businesses would build value through the use of their fixed assets (e.g., office buildings, production lines, warehouses, etc.), in the new economy, value is built through the gathering, analysis and application of big data. Indeed, for many modern businesses, their primary asset is exactly just this access to data, or as it has been called ‘data as an asset’. In this radically changed business environment, the traditional lending model and its reliance on a small set of asset types that are acceptable as collateral will likely fail to meet the future needs of many companies.

3) In industries where companies have access to a large supply of immovable assets to use as collateral, business turnover is high

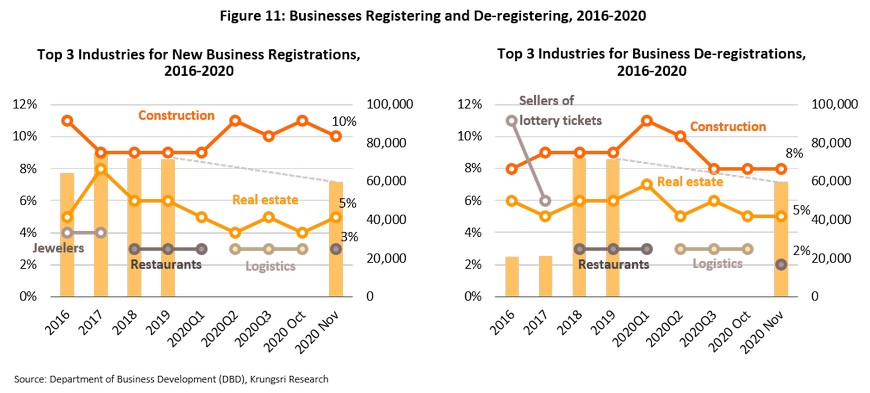

Over the past 5 years, the 3 industries that have seen the greatest number of new and ongoing businesses are, in order, (i) general construction companies (9% of new and ongoing businesses); (ii) real estate (8%), and (iii) wholesalers of machinery (2%). Clearly, players in these industries are likely to have access to either machinery or land and property that can be used as collateral when applying for loans. However, looking at the number of new businesses entering these markets and the number of those ceasing operations and deregistering, both general construction and real estate companies have been in the top 3 spots for both entering and exiting the market continuously over the past 5 years, while the other spots have tended to vary according to changes in the economy (Figure 11). With regard to reducing lenders’ LGD, issuing credit that is secured against real estate collateral to players in these industries may look reasonable since even if a large number of companies cease trading each year and are thus unable to clear their debts, it will still be possible to seize their core assets, convert these into cash and compensate creditors. However, the fact that there is a high level of business turnover in these two industries means that banks may face difficulties in assessing borrowers’ creditworthiness and in identifying companies that have the potential to grow, and so minimize the probability of default (PD).

4) At the macroeconomic level, the use of collateral (especially of immovable assets) tends to generate problems with procyclicality in the financial system

The value of real estate tends to be strongly procyclical, moving with changes in the economy overall. When the economy is in an expansionary phase, personal incomes grow and businesses have expanding cashflows and this increases both asset purchases and confidence in their future appreciation in value, which then in turn raises demand, causing prices to inflate even further. Banks will benefit from this because the collateral that they hold will likewise appreciate, and one effect of this will be to reduce their exposure to risk as LGDs decline. This will then tend to encourage banks to ease restrictions on access to credit, feeding a rise in household and corporate debt, but with this the economy will become more fragile, until problems with over-leveraging become widespread. At this point, if there is a cyclical turnaround in the economy or if an asset bubble pops and prices crash, it is possible that the debt problem will suddenly blow up, rapidly re-raising banks’ exposure to risk and pushing them to exercise much greater caution about authorizing new debt. Because access to credit has now tightened, households and businesses that are seeing shortfalls in their income may flip into a state from being over- to under-leveraged and they may then respond to their financial troubles by selling assets. Unfortunately, during a crisis, asset prices will be weak and declining and so if banks have to seize collateral from troubled borrowers and then dispose of these, the prices that they realize will tend to be poor, driving up expected losses across the financial sector. Given the role that assets in general and collateral in particular plays as a fuel powering this process, assets have been referred to as a ‘financial accelerator’, a description that matches research by Bernanke, Gertler, and Gilchrist (1998). Crowe et al (2011) and Davis and Zhu (2005) also present empirical evidence from many countries for this relationship.

Krungsri Research view: Overcoming problems with collateral

Collateral has for a very long time served a crucially important role in assessing creditworthiness and facilitating loan-making. The longevity of the practice stems from the fact that collateral addresses two problems simultaneously: problems with an asymmetry of information between debtors and creditors (here, a bank) and problems with expected losses suffered by the creditor in the event that the borrower defaults. The impacts of the latter may then be transmitted into the wider economic system thanks to the financial intermediary role that commercial banks play in the economy. Given this, the use of collateral helps to increase the efficiency with which financial resources are allocated.

However, due to the limitations discussed earlier, the use of collateral within the Thai financial system is as yet not very diversified compared to the situation in many other countries. Although it is true that in some regards, collateral helps to ease loan-making, in other ways, the need for collateral works as a barrier that prevents companies from accessing new credit. As described above, the requirements imposed by lenders particularly affect SMEs and players in the new economy because these typically do not own land or buildings that they can use as collateral. Instead, players in the new economy build value through their technological assets, and although these companies have access to big data and accompanying analytics, these are hard to appraise. Because of this imbalance, these players find it difficult to convince financial institutions to open credit lines for them, and even if they are successful in this, their borrowing costs are likely to be higher than those of other, more established companies. For lenders, collateral has also become a double-edged sword because if all creditors set the same loan conditions and require borrowers to secure loans against similar types of asset, this can work as a ‘financial accelerator’, as described above. In this case, when the value of the collateral increases, the outlook improves for creditors and debtors alike, which may then lead to excess borrowing, but when the economy contracts, the value of the collateral may crash, causing a precipitous decline in the fortunes of both lenders and borrowers, and possibly leading to the kind of systemic financial crisis that Thailand and other Asian countries experienced in 1997.

In the past, many attempts have been made to encourage commercial banks to increase their assessment of the riskiness of new loans and so reduce losses from NPLs, to reduce their dependency on assessing the LGDs, to increase their flexibility with regard to the types of collateral that banks accept, and to broaden their use of information-based lending which would help to cut the probability of default (PD) in stead of LGDs. If undertaken, these moves would help to ramp up the efficiency with which financial resources are allocated. However, change in this area is slow due to structural problems with market mechanisms, the legal framework and institutional inertia within commercial banks. Challenging and overcoming these problems will thus require the cooperation of all parties in exactly these areas, though change will be possible through the development of asset markets, the law and, for commercial banks, a broadening of the types of collateral that are used.

1) Speeding up the legal process by which creditors recover unpaid debts, from filing a case through issuing a court order for the seizure of collateral to selling foreclosed property, will help to protect against potential depreciation in the value of collateral. This will then cut banks’ exposure to credit risk, reduce their operating costs, help them to offer better credit to their customers, and extend the types of collateral that are considered acceptable, including those that degrade or lose value over time. Reforming the legal side of the problem in this way will help to overcome limitations with collateral with regard to its foreclosure and value retention characteristics. A precedent for these types of changes exists in the Business Security Act B.E. 2558, under which the enforcer and foreclosure can take place quicker and are less onerous than the processes laid out in other laws, and this might provide a model for future reforms.

2) Developing secondary markets for collateral, where at least initially, the government has a role to play as follows:

- Developing mechanisms for establishing reference prices will help to solve some of the problems with ascertaining the value of particular types of collateral. As banks cannot hope to have expertise in all the types of asset that might be used as collateral, this problem is especially salient for goods that might be used as collateral but for which at present it is difficult to make expert appraisals or that lack an established value. If these shortcomings were solved, this would have the benefit of increasing banks’ willingness to accept these assets as securities against loans, as well as cutting banks’ operating costs. One route to a solution to this might be by exploiting the power of artificial intelligence to assess prices for a particular type of asset on domestic and foreign markets and then to use this information to produce an initial benchmark price.

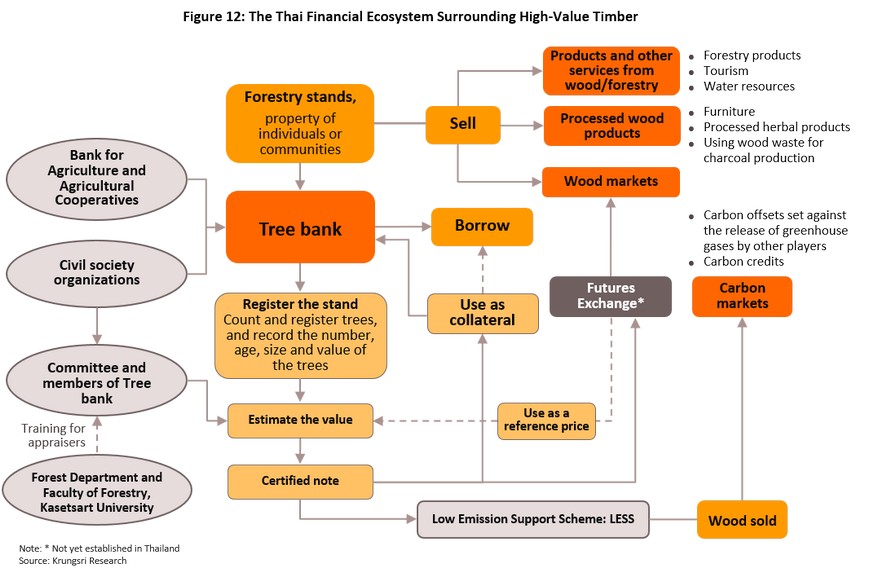

- Working with the private sector to develop tools to trade and auction assets will help the financial eco-system become more varied and complete, and this would then address problems with the liquidity of collateral. One example of a market mechanism that might be developed that would improve an asset’s perceived properties (as described above) and so increase the chance of its being accepted as collateral is a ‘tree bank’, which might allow individuals or communities to borrow against the high value of a timber plantation (Box 2).

3) Technology- and data-driven tools for evaluating credit risk, most obviously with regard to information on the business operations of potential borrowers, will help to alleviate limitations connected to asymmetric information. This could include electronic data on sales and purchases made for example via online platforms that can prove that a certain volume of business activities did indeed take place, which initially may be used in tandem with other types of collateral. In the future, it should be possible for lenders to develop a model for releasing new credit that is driven by big data (i.e., information-based lending) and success in this endeavor would help them to reduce the probability of default on debts, which would in turn lower their dependency on collateral.

4) Changing lenders’ attitudes has a crucially important role to play in overhauling use of collateral, given commercial banks’ role in assessing individual creditworthiness, recording customers’ financial history, deciding to demand collateral, and then agreeing to issue new loans. It is thus important to develop tools that help banks evaluate the potential of other, non-standard types of asset. Also needed are systems for connecting to other sources of customer financial data so that these can be used to evaluate creditworthiness, and processes that allow banks to check and track the new, more varied types of assets that might be used in the future as collateral.

If the banking sector is successful in overcoming the limitations described above, the financial system will substantially improve its ability to make loans, and commercial banks will more fully develop their role as financial intermediaries, with the use of collateral then helping to improve the efficiency with which resource allocation takes place within the economy.

Box 1: The importance of collateral to commercial banks for managing credit risk

Reckless lending has been the cause of innumerable past financial crises, most notably perhaps for Thailand during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Following these events, delinquent debts tend to pile up, while the value of assets held as collateral crashes, as a result of either a demand- or supply-driven popping of an asset bubble, to a level that is insufficient to offset accompanying losses from bad debts. As these debts sour, the financial footing of banks and of the wider financial system weakens. The trauma generated by these events has helped to underscore the necessity of commercial banks being much more careful in assessing credit risk and of maintaining a sufficiently generous cushion of capital, such that losses in a downturn, either a simple cyclical swing or a full-blown crisis, are not sufficient to destabilize the entire financial system.

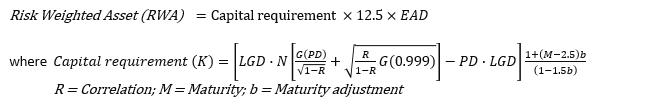

In 2008 in the wake of the global financial crisis, the Bank of Thailand overhauled the regulatory framework governing the operations of Thai commercial banks, which would henceforth be required to meet the Basel II regulations, set by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). These lay out new rules on how banks are to assess credit risk and rank customers’ risk of default, and the minimum capital requirements that banks need to maintain in order to meet both expected and unexpected losses arising from the credit that they have issued[19].

Expected losses are calculated from 3 factors:

- The Probability of default (PD)

- The Loss Given Default (LGD)

- The lender’s Exposure at Default (EAD)

Expected loss is calculated by simply multiplying these together:

EL = PD x LGD x EAD

For example, supposing that a bank issues a 30-year mortgage for the purchase of a house valued at THB 1,000,000 at an LTV of 90%, the initial value of the loan is THB 900,000.

- After 4 years, the remaining value of the loan is THB 800,000 and so a default at this stage carries an EAD of THB 800,000.

- If the market value of the house is THB 750,000 and the expenses entailed in selling the house come to THB 50,000, the LGD will be -800,000 + 750,000 - 50,000 = -100,000, or 12.5%.

- Assume now that the borrower has a 50% probability of default, given that the mortgage has a higher value than the house (i.e., the mortgage is now ‘underwater’).

- In this case, the expected loss will be 100,000 x 0.5 = THB 50,000 (PD x LGD x EAD = 0.5 x 0.125 x THB 800,000 = THB 50,000).

When evaluating the PD, banks may consider a variety of factors, and the ‘5C framework’ may be one of these. The LGD may also be influenced by the quality of the collateral, with these two moving inversely against one another (i.e., the higher the quality of the collateral, the lower the LGD). Collateral may also influence these calculations because it may disincentivize borrower defaults[20] and so although, debtors may put up collateral to demonstrate their ability to pay but this may simultaneously increase their willingness to do so as they try to avoid having their assets seized.

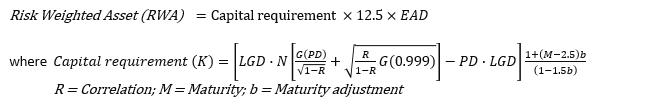

Regarding unexpected losses, both the PD and LGD are important inputs into calculating the risk weighting, and so these have a direct impact on capital requirements[21]. Given this, collateral has a significant impact on reducing commercial banks’ exposure to credit risk and on the opportunity costs that they must carry as a result of rules on minimum capital reserves that divert this from more profitable outlets.

Box 2: Developing a market mechanism to allow the use of high-value timber as collateral

The development of ‘tree banks’ is an example of how new types of market mechanism may be used to make more unusual asset types suitable as alternative choices for collateral, and so of extending access to credit to a broader range of borrowers[22]. The idea of using tree banks has been around since 2006, when civil society network began to discuss the idea, though the possibility of their use became much more concrete with the passing of the Business Security Act B.E. 2558, which opened the way for borrowers to use perennial plants listed in the relevant forestry regulations[23] as collateral for business loans. Government agencies led by the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives thus helped to establish the use of tree banks as guarantees for loans. At the same time, communities have been encouraged to plant, maintain and to more fully reap the benefits of plantation for the benefit of the broader value network, or “ecosystem”, surrounding forestry stands. This has been achieved by training inspectors in how to appraise the value of forestry stands that are used as collateral, and to add value to the timber being grown, community-level wood-processing businesses have been developed and communities have been connected to carbon markets.

Nevertheless, it remains possible to develop market mechanisms that will further extend the tree bank financial ecosystem. (i) Development of carbon markets and linking these to timber plantations will help to build value by allowing forestry communities to sell carbon credits[24] to industry, especially to carbon-intensive sectors such as petrochemicals, chemicals, construction and transport. These are responsible for the release of large quantities of greenhouse gases, though this can then be offset with carbon captured in forests. For example, research by the TDRI looked at Thai Airways, which has to pay around THB 1,000 in carbon offsets per passenger flying to locations in the European Union. This then imposed additional costs of around THB 500 million on the company. (ii) The development of a wood futures market would help to generate value by reducing risk arising from fluctuations in wood prices. This would also make available future reference prices for wood products to players in wood supply chains and help investors to better manage future supply and demand. (iii) Tree bonds would help the timber financial ecosystems add value and develop further by raising capital to be used for timber plantations, though this would necessitate recording data and estimating asset values, as well as requiring the provision of comprehensive care to the growing trees.

Reference

Aghion, Phillippe and Patrick Bolton (1992) “An Incomplete Contracts Approach to Financial Contracting”. Review of Economic Studies vol 59 pp. 1472-94

Bank of Thailand (Jan 13, 2004) “Financial Sector Master Plan (Phase I)” Financial Sector Master Plan, Bank of Thailand Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/FinancialInstitutions/Highlights/Pages/FSMP.aspx

Bank of Thailand (2008) “Regulation on the Calculation of Credit Risk-Weighted Assets for Commercial Banks under Internal Ratings-Based Approach (IRB)” The Notification of the Bank of Thailand No. FPG. 91/2551 Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://www.bot.or.th/

Bank of Thailand (2013) “Meeting to clarify the BOT's announcement and circulars on Regulations on Supervision of Capital in Accordance with the Basel III framework” Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/FinancialInstitutions/Highlights/Pages/Basel3.aspx

Bank of Thailand (2020) “Rules, Procedures and Conditions for the Undertaking of Digital Personal Loan Business.” the Bank of Thailand (BOT)’s the Circular Re Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/FIPCS/Documents/FPG/2563/ThaiPDF/25630236.pdf

Berker, Allen N., W. Scott Frame and Vasso Ioannidou (2011) “Tests of Ex ante Versus Ex post Theories of Collateral Using Private and Public Information” Journal of Financial Economics 100 pp. 85-97

Bernanke, Ben, Mark Gertler, and Simon Gilchrist (1998) "The Financial Accelerator in a Quantitative Business Cycle Framework," NBER Working Papers 6455, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Crowe, Christopher, Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, Deniz Igan and Pau Rabanal (2011) “Policies for Macrofinancial Stability: Options to Deal with Real Estate Booms” IMF Staff Discussion Note

Davis, E. Philip and Haibin Zhu (2005) “Commercial Property Prices and Bank Performance” BIS Working Paper No 150

Le, H. A. Chau and Hieu L. Nguyen (2019) “Collateral Quality and Loan Default Risk: The Case of Vietnam” Comparative Economic Studies vol. 61(1) pp. 103-118

Forrester (Oct 22, 2020) “Top Emerging Technology Trends To Watch In 2021 And Beyond” Forrester Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://go.forrester.com/press-newsroom/forrester-top-emerging-technology-trends-to-watch-in-2021-and-beyond/

Godlewski, Christophe and Laurent Weill (Nov 2006) "Does Collateral Help Mitigate Adverse Selection? A Cross-Country Analysis" Journal of Financial Services Research 40(1) pp. 49-78

Guyer, Stephen (Jun 5, 2005) “You’d be surprised what can be used for collateral” Denver Business Journal Web. Retrieved Sep 29, 2020 from https://www.bizjournals.com/denver/

Hart, Oliver (1995) Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure Oxford University Press

Hainz, Christa, Thanh Dinh, and Stefanie Kleimeier (2011) “Collateral and its Determinants: Evidence from Vietnam” Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Berlin 2011, No. 36

Manove, Michael., A. Jorge Padilla and Marco Pagano (2001) “Collateral versus Project Screening: A Model of Lazy Banks” Rand Journal of Economics vol. 32 pp.726-744

Menkhoff, Lukas, Doris Neuberger and Chodechai Suwanaporn (2006) “Collateral-based Lending in Emerging Markets: Evidence from Thailand” Journal of Banking & Finance vol. 30 pp.1-21

Menkhoff, Lukas, Doris Neuberger and Ornsiri Rungruxsirivorn (2012) “Collateral and its substitutes in emerging markets’ lending” Journal of Banking & Finance vol 36 pp. 817-834.

Mergermarket (Jan 23, 2020) “Top Tech Trends To Watch In 2020” Forbes Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/mergermarket/ 2020/01/23/top-tech-trends-to-watch-in-2020/?sh=3b915de54d1f

New Bond Street Pawnbrokers (Mar 23, 2018) The History of Pawnbroking and Collateral Loans Web. Retrieved Oct 9, 2020 from https://www.newbondstreetpawnbrokers.com/

Office of the Council of State (2003) Commercial Banking Act, B.E. 2505 Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from http://web.krisdika.go.th/

Office of the Council of State (2017) Civil and Commercial Code Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from http://web.krisdika.go.th/

Orawan Kesorn (2017) Principles and Essence of Business Collateral Act Web. Retrieved Mar 1, 2021 from https://www.parliament.go.th

Powley, Tanya (Mar 5, 2010) “Luxury assets used to fund mortgages” Financial Times Web. Retrieved Sep 29, 2020 from https://www.ft.com/

Rahman, Ashiqur, Jaroslav Belas, Tomas Kliestik, and Ladislav Tyll (July 2017) “Collateral requirements for SME loans: empirical evidence from the Visegrad countries” Journal of Business Economics and Management vol.18 pp. 650-675

Ratchakrit Klongphayabal (2015) ”Businee Plan and SMEs Chapter….The Origin of Business Plan.” Thai SMEs Center Web. Retrieved Dec 18, 2020 from http://www.thaismescenter.com/

Sakol Harnsuthivarin (Jan 12, 2016) “Business Collateral Act B.E. 2558 (2015): Increasing opportunities to access capital” BangkokBizNews Web. Retrieved Oct 1, 2020 from https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/

Saowanee Chantapong and Nitisan Phongpiyaphaiboon (Jun 2017). 20 Years After the 1997 Crisis: Lessons for a Balanced and Sustainable Economy, FAQ Issue 115, Bank of Thailand

Sarunjade (Dec 5, 2018) “”What is 5G? 5G in 5 minutes" MarketingOops.com Web. Retrieved Jan 14, 2021 from https://www.marketingoops.com/

Shepherd, Maddie (Sep 9, 2020) “7 of the Most Surprising Items Ever Used as Collateral” Fundera Web. Retrieved Sep 29, 2020 from https://www.fundera.com/

StartUs Insights (2020) “Top 10 Industry 4.0 Trends & Innovations: 2020 & Beyond” Research Blog Web. Retrieved Jan 22, 2021 from https://www.startus-insights.com/innovators-guide/top-10-industry-4-0-trends-innovations-2020-beyond/

Surapol Opasatien (Apr 17, 2019) “Open Surapol Opasatien's perspective on household debt situation - the future of Thai banks” mgronline Web. Retrieved Dec 18, 2020 from https://www.ncb.co.th/

Thailand Development Research Institute (2015) “The Design of Model for Forestry Bond in Thailand.” under MEAs (Multilateral Environment Agreements) Think Tank Web. Retrieved Feb 2, 2021 from https://tdri.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/REPORT-Forest_Bond.pdf

Thomas, Andrew (Feb, 2020) “7 Major Business Trends to Watch in 2020” Inc. Web. Retrieved Jan 12, 2021 from https://www.inc.com/andrew-thomas/7-major-business-trends-to-watch-in-2020.html

Wood, Meredith (Nov 20, 2020) “5 Different Kinds of Collateral Business Lenders Might Want to See” Fundera Web. Retrieved Nov 30, 2020 from https://www.fundera.com/

Yale University (2020) “Lecture 7: Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice and Collateral, Present Value and the Vocabulary of Finance“ ECON251 Web. Retrieved Oct 9, 2020 from https://oyc.yale.edu/

[1] Observed-risk hypothesis

[2] Bank runs occur when depositors lose faith in a bank and begin to believe that it may fail, taking their savings with it. In this case, depositors often rush to the bank to withdraw their deposits and close their accounts before they incur losses, though this very action may help to precipitate the event that they fear and with this, instability may spread through the financial system.

[3] Book I covers general principles, Book II debt, Book III specific contracts, Book IV assets, Book V households, and Book VI inheritance.

[4] As per section 723

[5] Thailand showed a very strong reliance on the use of collateral as a proxy for assessing loan quality, and this often exceeded the extent to which lenders did this in developed economies. See Menkhoff, L., Neuberger, D. & Suwanaporn, C. (2006). Collateral-based lending in emerging markets: Evidence from Thailand. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30: 1-21

[6] From an interview with a bank manager quoted in Rachakrit Klongpayabal’s ‘SME Business Plans – The history of Business Plans’, and ‘Views on the Situation with Household Debt and the Future of Thai Banking’ by Surapol Opasatien.

[7] Manove, M., Padilla, A. J. & Pagano, M. (2001). Collateral versus Project screening: a model of lazy banks. Rand Journal of Economics, 32: 726-744.

[8] Financial Sector Master Plan Phase I (Jan 13, 2004), Bank of Thailand

[9] Saowanee Chantapong and Nitisan Phongpiyaphaiboon (Jun 2017). 20 Years After the 1997 Crisis: Lessons for a Balanced and Sustainable Economy, FAQ Issue 115, Bank of Thailand

[10] National Credit Bureau (NCB) was established in 1999 to act as an intermediary collecting information on businesses’ and households’ credit history, with the intention of helping lenders better assess borrowers’ creditworthiness. The existence of credit bureaus also helps to encourage borrowers to maintain a healthy credit history since this will generally lead to easier and cheaper access to credit. Recording credit histories also helps to overcome problems with asymmetrical information and as such, this move has helped to allocate financial resources more effectively, increasing the overall efficiency of the Thai financial sector.

[11] Bank of Thailand (2020) Regulations, methods and conditions for offering digital consumer loans, Circular letter.

[12] This can be undertaken by private-sector players (as per paragraph 2, section 470 of the Civil and Commercial Code), the Legal Execution Department or by the administrator (when the case is being pursued via administrative enforcement).

[13] This is with the exception of cases involving auto hire-purchase agreements, which can be concluded rapidly since under the relevant law, ownership of the vehicle that is used as collateral remains with the lender until the conclusion of the repayment schedule.

[14] As per the Commercial Banking Act B.E. 2505, section 12 ter.

[15] Menkhoff, L., Neuberger, D. & Rungruxsirivorn, O. (2012). Collateral and its substitutes in emerging markets’ lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36:817-834.

[16] Collateral requirements for SME loans: Empirical evidence from the Visegrad countries (A. Rahman and et.al., 2017)

[17] 5G is short for ‘5th Generation’ of wireless technology. 5G technology will not only provide better mobile services but will also allow for the connection of a wide range of devices, leading to the so-called ‘internet of things’ (IoT).

[18] INC., StartUs insight, Forbes, Forrest research

[19] Bank of Thailand (2013) ‘Regulations on Supervision of Capital in Accordance with the Basel III framework’

[20] Chau H. A. Le & Hieu L. Nguyen, 2019. "Collateral Quality and Loan Default Risk: The Case of Vietnam," Comparative Economic Studies, Palgrave Macmillan; Association for Comparative Economic Studies, vol. 61(1), pages 103-118, March.

[21] The formula for calculating risk for government, financial and business borrowers is as follows:

[22] Thailand Development Research Institute (2015) ‘The Design of Model for Forestry Bond in Thailand’

[23] There are 58 species listed in relevant forestry plantation law, including Tectona grandis, Dalbergia cochinchinensis, Pterocarpus macrocarpus, Afzelia xylocarpa, Xylia xylocarpa, Shorea obtuse, Shorea siamensis, Hopea odorata, Azadirachta indica, Prunus cerasoides, Millingtonia hortensis, Lagerstroemia floribunda, Mangifera indica, Durio, Dipterocarpus, Phyllanthus emblica, Bambuseae Magnolia, Cassia bakeriana, Cassia fistula, Syzygium cumini, Samanea saman, Aquilaria crassna, and Lignum aloes.

[24] Carbon credits are a means of offsetting carbon that has or will be released against projects that aim to reduce the future quantity of CO2 deposited in the atmosphere.