Now that Covid-19 infections are on a distinct downward trend in many advanced countries, governments have moved to return economies to something like their pre-crisis state by easing the lockdowns. However, with the lifting of control measures and a sharp acceleration in economic activity, inflationary pressures have surged, putting governments on alert that economies may overheat and that it may be necessary to transition from an expansionary fiscal stance to a position that is more cautious. Central banks are thus considering easing back on the support that they have been providing to markets since the start of the crisis by tightening their monetary policy. Against this general background, any change to monetary policy in the US is particularly important since this has the potential to generate turbulence and uncertainty globally, though this an especially intense risk for emerging economies.

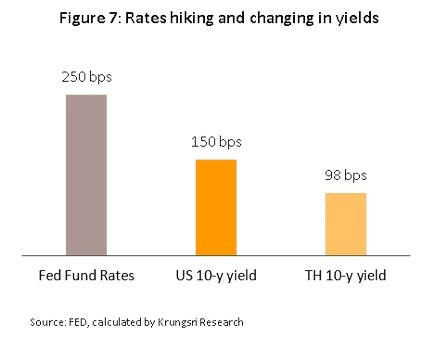

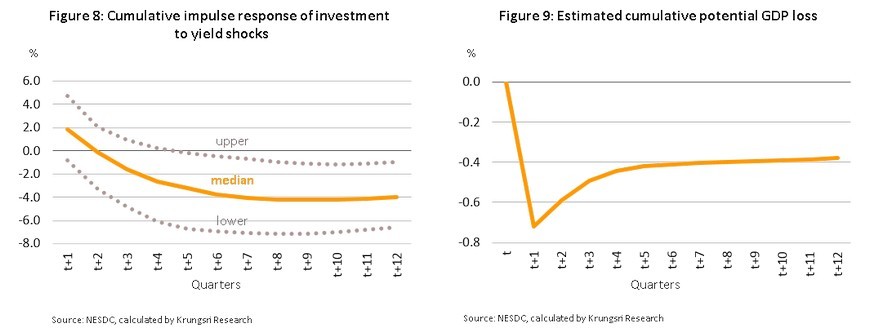

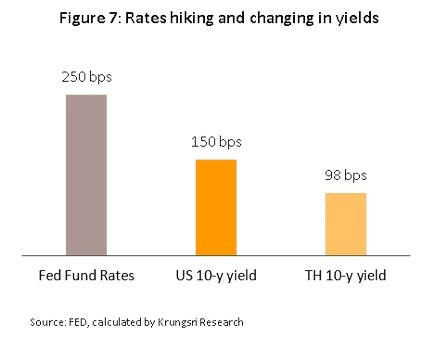

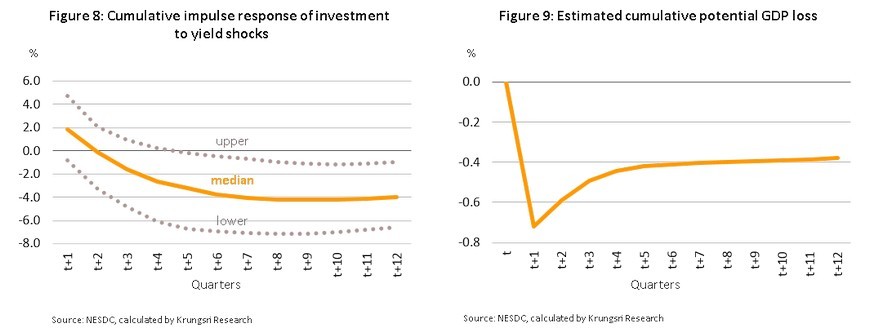

In light of this, Krungsri Research has analyzed how changes in US monetary policy will be transmitted to emerging markets generally and Thailand in particular through the three channels of bond markets, equity markets and exchange rates. Thus, if the Fed tightens monetary policy and hikes policy rates to 2.5%, this will have the effect of triggering a sell-off of government securities and of raising yields on 10-year US and Thai government bonds by respectively 1.5% and 0.98%. For Thailand, these higher yields would increase the cost of raising capital, which would translate into a 3.2% fall in domestic investment compared to the baseline case. It would take 5 quarters for the full effects of these changes to become manifest, but that when they do so, they would shave 0.4% from long-term Thai GDP growth.

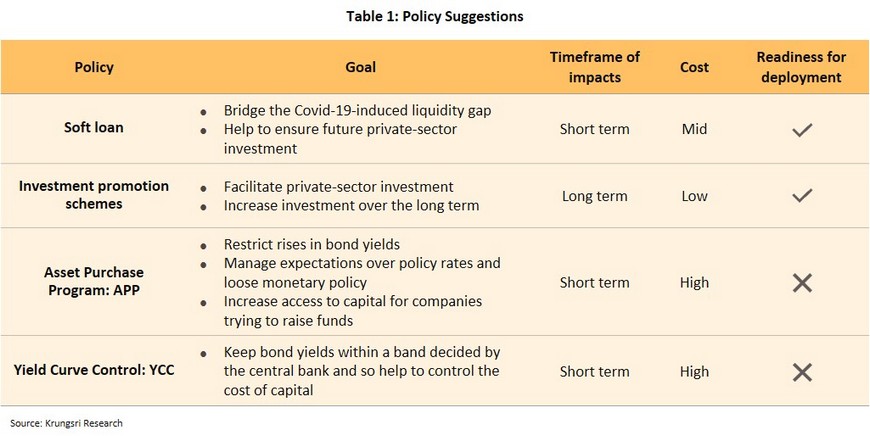

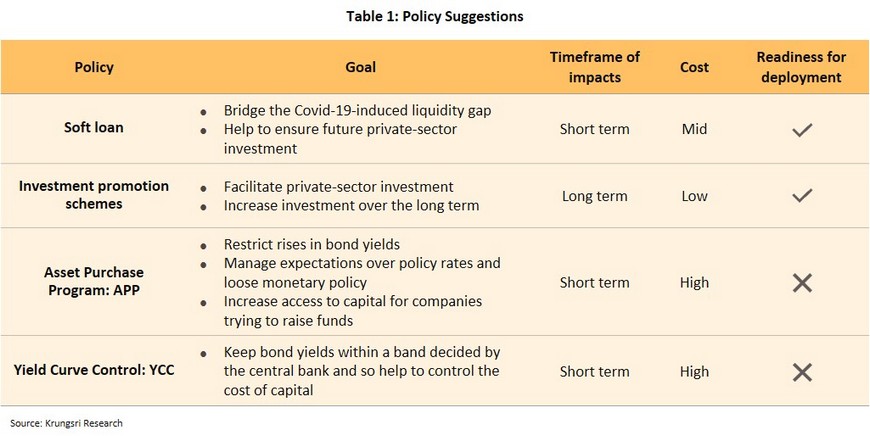

The pause between any rise in bond yields and the impact of this being felt on the broader economy will provide a breathing space for policymakers to mitigate the effects of the oncoming disruption, whether that is by pulling on existing policy levers or by deploying new monetary tools. There are three main classes of tool available: policies that may be deployed rapidly and that generate results equally rapidly (e.g., soft loans), policies that may be deployed rapidly but that generate results only over the long term (e.g., investment promotion schemes), and policies that are perhaps not yet ready for full deployment but that should be considered for future use (e.g., Asset Purchase Program and Yield Curve Control schemes), though all three of these aim equally to reduce the risk of a long-term slowdown in the Thai economy.

Since the start of the Covid-19 crisis, policymakers worldwide have deployed the broadest range of fiscal and monetary firepower assembled since the global financial crisis of 2008, and this reflects the decision to tackle the current crisis on the two fronts of public health and the economy. In many countries, fiscal responses to the pandemic have focused on sustaining domestic consumption by providing financial support to the workforce and ensuring that businesses remain above water, while monetary policy has followed both conventional policy responses, such as cutting interest rates to historic lows, and more unconventional routes, for example through the quantitative easing (QE) seen in some countries. This has been implemented via significant purchases of short- and long-term government and corporate bonds, made with the aim of stabilizing financial markets, maintaining liquidity, and increasing the potential flowthrough of monetary policies to the real economy.

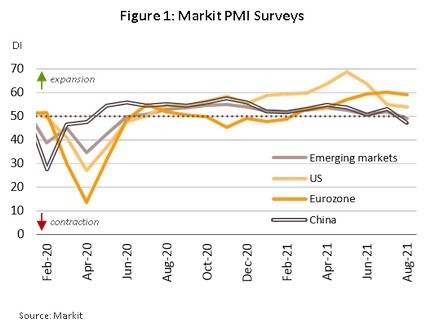

National responses to the outbreak of Covid-19 began to take shape in March 2020 as the need to counter the economic costs imposed by the pandemic became clear, but the type, scale, and length of the measures put in place have varied from country to country, as has the ability of local authorities to bring infections under control. These differences have put countries on quite distinct paths to recovery, with advanced economies able to implement and sustain significantly more comprehensive support for their economies, which then helped these countries rebound from the pandemic more rapidly. The variation in recovery rates is reflected in the divergent tracks of the national and regional Purchasing Managers Indices (PMIs). Thanks to their much greater financial power, the advanced economies have seen PMIs for both their service and manufacturing sectors break through the all-important 50-point barrier and continue upwards into expansionary territory, whereas developing economies and emerging markets have continued to struggle against the spread of the Delta variant, which has weighed on economies, pulled PMIs back under the 50-point waterline and prevented a speedy recovery (Figure 1).

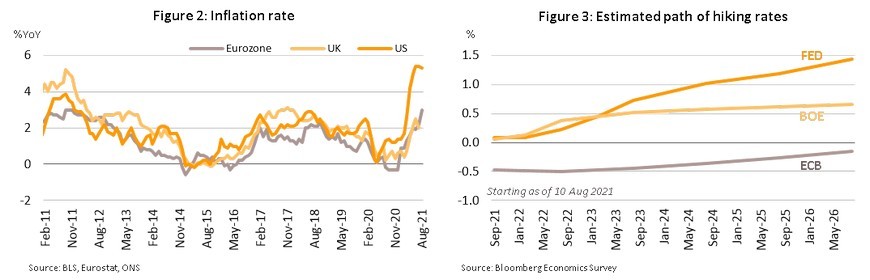

As part of their remit to secure economic growth and to guard against threats to this, central banks are principally concerned with maintaining price stability, and so bankers have naturally looked on with some concern as spikes in inflation in the US, the UK and the Eurozone have pushed prices close to their highest this century. This sudden rise in inflationary pressures has been caused by a combination of comparison with last year’s low baseline, the sudden release of demand for goods and services as economies restarted (Figure 2), and the strong rebound in advanced countries.

Krungsri Research believes that there are three principal channels by which the impacts of changes in US monetary policy will be transmitted to emerging markets:

Or will history repeat itself?

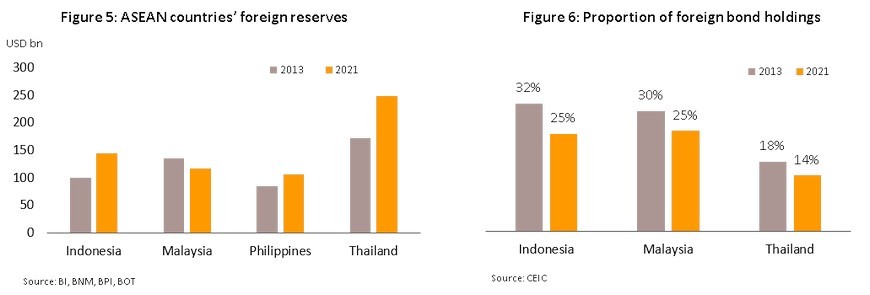

Thailand is among the group of emerging markets exposed to the risk of fallout from changes to US interest rates. The potential damage that could be wrought by changes to US policy was exposed in 2013, when investors anticipated a tightening of the monetary taps by the Fed that then triggered a wave of uncertainty. This roiled markets globally, causing a temporary outflow of capital from Thailand, but at the time, the country benefited from a high degree of fiscal and monetary stability compared to its regional competitors and so in fact, the events of 2013 resulted in a net inflow of funds. Krungsri Research believes that the country now faces international markets from a stronger position than was the case eight years ago, and that current foreign currency reserves are such that there is unlikely to be any aggressive sell-off in the wake of the Fed winding up its asset buying program. Thailand is therefore well positioned to weather any economic storm that may result from this, though the likelihood of this happening has in any case been reduced by the Fed’s messaging at the annual Jackson Hole bankers’ meeting, where it indicated clearly that a reduction in bond buying can be expected before the end of the year. In contrast to 2013, the markets have responded positively to developments this year, and the risk of investors reacting badly has clearly been significantly reduced by the much better communication of the bank’s intentions.

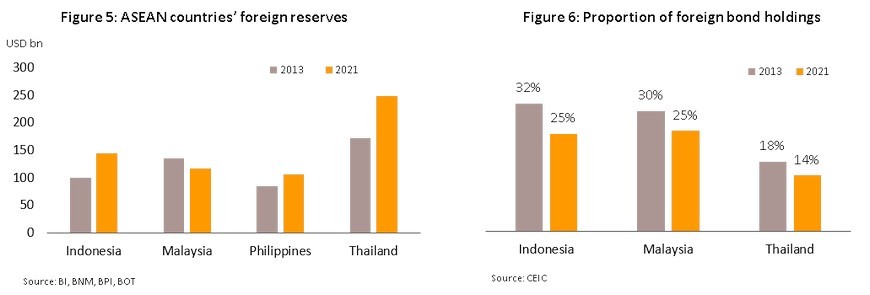

Nevertheless, Thailand’s role in the global economic system has changed since 2013 and comparing the Thai economy now to other emerging markets casts the country in a less flattering light. Unlike eight years ago, the Thai economy is currently more fragile, while the country’s neighbors are in a stronger financial position and so Thailand may no longer enjoy its earlier role as an emerging market safe haven. Thus, the foreign currency reserves of countries in the region are generally higher (Figure 5) while foreign bond holdings are down (Figure 6), and so although Thailand’s financial stability may have improved relative to its historical record, compared to these countries, its position has worsened. Making matters worse, recovery from the Covid-19 crisis is at best sluggish, and the hugely important tourism sector remains in an extremely depressed state, further weakening its relative position.

Krungsri Research therefore believes that although reducing the scale of assistance to the US economy may not now significantly add to financial risk or affect liquidity, tighter US economic policy could still have knock-on consequences for the Thai economy through the greater cost of financing that it may entail.

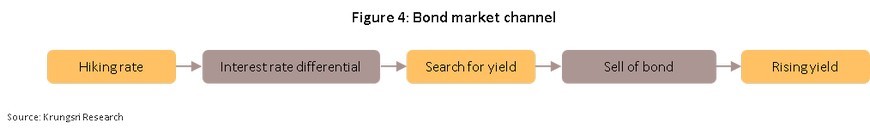

The bond market will be the principal channel through which changes in US monetary policy will be transmitted to the Thai economy

To assess the potential impacts of a change in US monetary policy on exchange rates and the Thai bond market, and through this on the broader economy, Krungsri Research has analyzed quarterly market and economic data for the period from 2000 through to the first quarter of 2021. The results of this analysis indicate that tightening policy is positively correlated with sell offs in Thailand and outflows of capital from the country, which then puts downward pressure on the baht. However, in contrast to what might be expected, the weakening of the baht that results from this is not significantly correlated with a strengthening of exports. Rather, the main determinate of any improvement in the latter is economic growth in export markets.[1]

Instead of helping exports, US monetary tightening tends to generate negative impacts for Thailand that are transmitted through the bond market, because for every 100 bps increase in policy rates made by the Federal Reserve, yields on 10-year treasuries rise by around 60 bps, which then feeds through into a 39 bps rise in yields on 10-year Thai government bonds. On the assumption that US policy rates are likely to rise to 2.5% over the long term (as per the Fed’s June dot plot), this would then mean that the yields on 10-year US and Thai government bonds will climb by some 1.5% and 0.98%, respectively (Figure 7). However, bond yields serve as a benchmark for comparing returns on investment in other asset classes, and so increases in bond yields are one factor underpinning widespread increases in the cost of financing, which may then weigh on future increases in investment.

More expensive financing reduces private-sector investment, and a 0.98% increase in bond yields will result in the long-term loss of 0.4% of GDP growth

Krungsri Research’s analysis shows that the forecast rise in yields on 10-year Thai government bonds, the impact of this on pushing up the cost of financing, and the resulting weakening in private-sector investment in the Thai economy will take approximately five quarters to play out, but declines in economic growth will begin to show up in the next period. Assessment using a VAR model indicates that the predicted 1% increase in bond yields translates into a 3.2% drop off in private-sector investment (Figure 8). Using that as an input into an impulse response model then reveals that the fall in investment impacts all the major components of GDP, from imports of machinery to industrial output to labor markets, which then undercuts consumption and helps to generate a negative feedback loop such that the 3.2% decline in investment ultimately means that long-term economic growth is reduced by 0.4% (Figure 9).

There is thus a delay between the implementation of a more hawkish approach in the US, higher bond yields and the real-world effects on the Thai economy, but when these become manifest, they will be long lasting. The breathing space that exists prior to the higher cost of capital showing up in data on investments therefore gives policymakers a crucially important opportunity to buy time and to consider how best to reduce the approaching impacts by deploying more unconventional monetary policies, perhaps mixed with fiscal measures.

Low-interest loans and investment promotion schemes can be set up without delay, but unconventional monetary policies remain future possibilities

If or when the rising cost of financing begins to eat into economic growth, policymakers will need to respond, and to this end, they will have access to a range of tools. The authorities may turn to tried and trusted policies that can be deployed more-or-less instantly, but they should also consider the possibility of using new tools that are able to provide a comprehensive but direct response. In choosing the most efficient and effective route to take, attention should be given to the nature of the policy choices available, each policy’s objectives and costs, and their readiness for use and expected timeframe. The available policy tools can be split into three groups according to their speed and viability of deployment. These are described below.

1. Policies that can be implemented quickly and that return rapid results

Many of the most accessible policy levers have been worn smooth with use, but with some tweaking, they still provide a viable means by which assistance can be channeled rapidly and directly to trouble spots within the economy. Soft loans are prominent among this class of interventions, and although the Bank of Thailand has been keen to use these to target precariously positioned SMEs and to increase their access to liquidity throughout the period of the Covid-19 crisis, their potential has not yet been exhausted. If the cost of borrowing rises in the post-Covid environment, soft loans will still have a role to play in supporting investment by high-potential SMEs as these adjust to the changing business landscape.

It would be possible to roll out a low-interest loan program more-or-less instantly, but the experience gained from earlier policy implementations indicates that changing or relaxing some qualifying criteria would widen access and so increase any future program’s efficiency. When new soft loan program was introduced, some of the loan criteria were altered, and this then increased the authorities’ ability to reach troubled SMEs; compared to the earlier soft loan program, which managed to distribute only 28% of the THB500 billion allocated to it, as of 30 August, 2021. This new program had managed to disburse 40% of its allocations. Some of the changes made to the program included: expanding its reach to cover a wider range of debtors, simplifying and streamlining the terms and conditions and qualifying criteria, raising the collateral required to 70% of the loan value for companies with a turnover of less than THB50 million, and extending the repayment term from 2 to 5 years.

Low interest loans offer the significant advantage of funneling assistance directly to SMEs, which are a mainstay of the Thai economy. These businesses will be able to put this money to use immediately and this will then generate benefits for the economy in a fairly short timeframe. In addition, although it is true that soft loans are more expensive than other types of monetary policy used under normal conditions, these costs are tolerable and will not threaten the stability of the central bank.

2. Policies that can be implemented rapidly but that make returns only over the long term

Investment promotion schemes are another way of supporting and increasing investment inflows even as borrowing costs rise, this time with a mixture of fiscal policy added to the blend. Investment promotion schemes should be designed to unfold in stages, for example as follows

- Attract greater private sector investment by developing the ability of national infrastructure to support business activity, increasing digital and technological preparedness, reforming tax codes and business regulations to create a more business friendly environment, and ensuring that market mechanisms function correctly and make appropriate returns to business[2].

- Increase market access through joining free trade agreements, offering special tax rates, and opening to markets that are rich in consumers and/or consumer spending power. This will then provide businesses with entry to larger markets and open the way to greater profitability.

- Develop links with local manufacturers to help accelerate technology and know-how transfer related to manufacturing processes. This will help to increase manufacturing capabilities at all levels and so boost competitiveness.

Investment promotion schemes typically require regulatory reform and active participation in trade agreements, and on the positive side, the costs of pursuing policies such as these are relatively low, while in any case, Thailand is already doing much of the necessary groundwork, so more actively promoting Thailand as an FDI target would be relatively easy. However, although this holds out the possibility of offsetting future problems with weak domestic investment, there would be a significant lag between the policy’s implementation and the resulting economic benefits becoming apparent.

3. Policies that are not yet ready for full deployment but which should be carefully considered

Although the Covid-19 crisis is beginning to slacken in intensity, continuing uncertainty is likely to pose a challenge to policymakers trying to pursue conventional monetary policy. To avoid these obstacles, it may therefore be necessary to begin considering a switch to the deployment of unconventional monetary tools, and these now offer the possibility of interesting and fruitful new policy choices for Thailand. In particular, it may be possible to address problems with rising yields for government bonds directly through the implementation of an asset purchase program (APP) and by moving to a policy of yield curve control (YCC), and indeed, the crisis of 2020 saw many emerging economies (e.g., Mexico, Indonesia, and the Philippines) begin to do just this. Clearly, these policies require significant expenditure and over the long term, the resulting bills may weaken central bank stability, but they do present a way of tackling the problem of rising yields directly at the source. Research by the IMF issued in 2020 also reveals that if central banks want to prevent excessive increases in government bond yields, quantity-based interventions that impose a ceiling on the scale of bond buying are more effective than price-based tools that specify target yields. This is because the former make clear how extensive purchases will be and this helps to control the costs borne by the central bank. Given this, careful attention should now be paid to the development of a viable plan for an asset buying program and for setting a target for government bond yields.

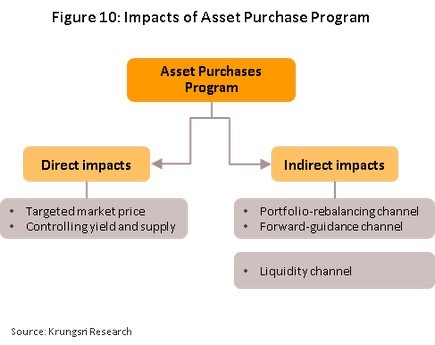

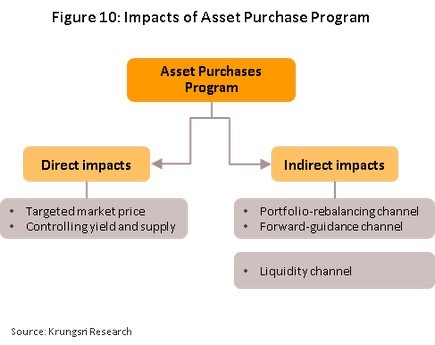

- Asset Purchase Program involves central bank purchases of government bonds up to a clearly specified ceiling. Research on these types of intervention in the advanced economies shows that these have direct and indirect effects on both financial markets and the wider economy. The direct effects include stronger demand and higher prices for bonds, which then directly reduces yields, while the indirect consequences are felt by markets and include the following:

- Portfolio-rebalancing channel: Widespread asset buying brings down yields and this then prompts investors to switch to higher-paying instruments, such as corporate bonds. Higher demand suppresses the yields of these and because of this, private-sector financing costs are lowered.

- Forward-guidance channel: An announcement by the central bank that it will begin large-scale asset purchases will tend to reduce market expectations of a short-term hike in interest rates and increase expectations that the authorities will continue to provide liquidity by keeping monetary policy relaxed. This will help to suppress any increases in the cost of financing and will therefore protect against a slowdown in investment.

- Liquidity channel: Injecting additional funds into the economic system will alleviate any tightness in the supply of money and will help to improve liquidity across the economy overall.

Nevertheless, all policy options carry costs, whether financial or not, and large-scale asset buying by the central bank is no exception to this. Because quantitative easing-type interventions require the central bank to print enormous quantities of money, over the long run, asset buying schemes may erode trust and confidence in central banks and their ability to control the money supply, a situation that may then worsen if governments’ lack fiscal discipline. In addition, there is a risk that asset buying will disproportionately benefit large corporations since these are much more likely to turn to bond markets when they are raising capital. Moreover, central bank support of asset markets typically plays out over fairly long time horizons, and the longer asset buying takes place, the greater the risk that market mechanisms will be distorted, thus raising the chance that heavy central bank spending may translate into a sudden inflation of prices for a broad range of asset classes. To help counter this and to maintain confidence in the economy, central banks will need to be extremely careful to preserve their credibility and to communicate policy intentions clearly, honestly and directly.

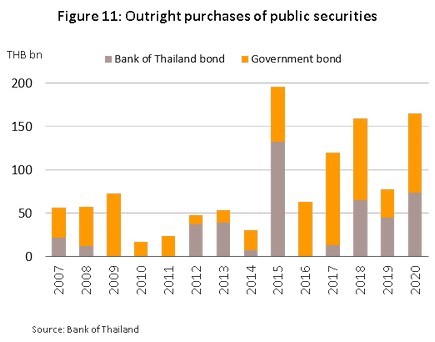

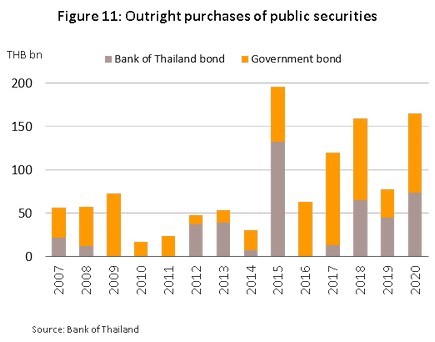

In the particular case of Thailand, although the central bank has intermittently stepped into the bond market, this has generally been to ensure that short-term needs for liquidity are met and so the scale of these interventions has been limited, a situation that has not changed during the Covid-19 crisis. In Krungsri Research’s view, this represents a shortfall in the bank’s approach to the current situation, and policymakers now need to consider significantly expanding the scale of future asset buying if they wish to directly reduce the costs of raising finance for Thai businesses. In addition, such a move would help to increase liquidity across the economy and to peg market expectations over future changes in policy rates (Figure 11).

- Yield Curve Control (YCC) is a new weapon in the monetary policy armory. This has been introduced to try to restrict increases in yields to pre-specified targets, and has been tried out in Australia and Japan, the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Japan having pledged to intervene in bond markets to the extent necessary to keep yields on 3-year and 10-year government bonds to respectively 0.25% and 0%. Clearly, if YCC is successfully implemented, it will result in exactly what it sets out to do, that is, hold any increase in yields to the central bank’s target range but pursuing this policy is very expensive and unlike APP, it is not possible to say in advance just what the end cost will be.

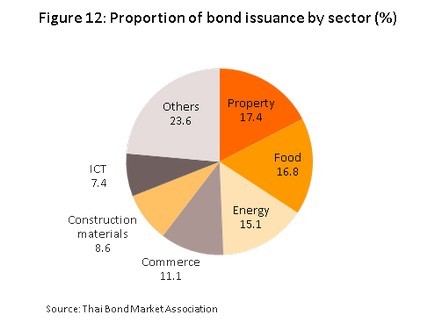

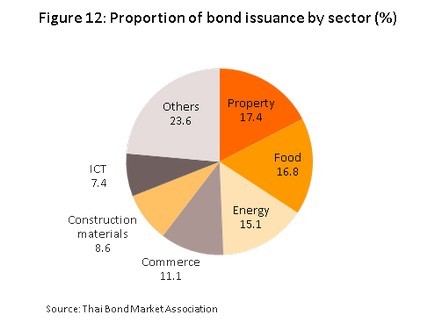

Research into Australia’s experiment with yield curve control shows that the Reserve Bank of Australia purchased over THB3.2 trillion worth of bonds, with the result that yields were 15 bps lower than they would otherwise have been. The total value of the market for Australian government bonds is around THB17 trillion, so central bank spending represented around 18.8% of the entire market value. In Thailand, the market for government bonds is lower at THB9 trillion, but assuming similar returns on investment, an equivalent impact on yields would necessitate THB1.13 trillion in spending by the central bank, and compared to the consequences of more expensive finance on the economy, this is a significant expenditure. Pursuing a policy that involves this kind of broad-based YCC is thus difficult to imagine, but a targeted policy would carry a less weighty price tag while offering the possibility of making more focused interventions. For example, in Thailand, lenders are more wary of extending credit to real estate developers, which then have to raise capital by issuing bonds or debentures. Because of this, the real estate sector accounts for over 17% of corporate bond issuance (Figure 12), making it realistic to target YCC at just this segment of the bond market.

Successfully implementing unconventional policies such as these requires that central banks stay completely in control of quantitative and qualitative issues because otherwise, the gap that may open between reality and policymakers’ prior commitments will mean that their credibility will hang by a thread. Likewise, large-scale interventions in capital markets also generally lead to huge expansions in central bank balance sheets, and once started, it can be hard to control this growth or to scale it back in the future. To counter these issues and to ensure that unconventional monetary policies are successfully implemented, it is essential that central banks maintain their credibility, and this depends on the bank’s clarity, transparency and verifiability. Abiding by the dictates of this holy trinity will then help to determine the expectations of players in the business sector, build greater trust in the authorities, and increase the efficiency of the flowthrough of effects from monetary policy to the real economy.

In conclusion, the tightening of monetary policy that the Federal Reserve is likely to implement within the fairly near future will raise yields on 10-year Thai government bonds, pushing up the cost of capital, suppressing the level of investment, and cutting 0.4% from the Thai economy’s long-term growth. The movement from US policy hikes to a fall in Thai GDP will take around 5 quarters to complete, providing the authorities with a breathing space within which they will be able to consider, prepare and roll out policy responses to blunt the pain inflicted by the approaching turbulence. Faced with this, policymakers are likely to reach for a mix of fiscal tools and soft loans, since these are both quick to execute and quick to yield benefits, but serious consideration should also be given to how unconventional monetary policies could be implemented. These, which might include asset purchasing and yield curve control programs, should be coupled with ceaseless efforts to build the credibility of the central bank, and the result of this would be to significantly improve the authorities’ ability to respond directly and effectively to the core problem of rising bond yields. By adopting this stance, policymakers would be able to buy time for the Thai economy to recover further before the full impact of higher capital costs hits. It is true that these policies carry with them the risk of increasing economic instability over the long run, but if this is the cost of preserving the Thai economy’s growth potential and of preventing it from slipping into a long-term slump, it may prove to be a price well worth paying. As the old adage has it, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”.

References

Bank of Thailand, Monetary Policy Report, June 2018

Brandao-Marques, Luis and Gelos, R. Gaston and Harjes, Thomas and Sahay, Ratna and Xue, Yi, Monetary Policy Transmission in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (March 1, 2021). CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP15931

Brooks, Jordan and Katz, Michael and Lustig, Hanno N., Post-FOMC Announcement Drift in U.S. Bond Markets (March 27, 2019). Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 18-2,

Elias Albagli & Luis Ceballos & Sebastián Claro & Damian Romero, 2018. "Channels of US monetary policy spillovers to international bond markets," BIS Working Papers 719, Bank for International Settlements.

Eser, Fabian & Schwaab, Bernd, 2016. "Evaluating the impact of unconventional monetary policy measures: Empirical evidence from the ECB׳s Securities Markets Programme," Journal of Financial Economics, Elsevier, vol. 119(1), pages 147-167.

Estrada, Gemma Esther & Park, Donghyun & Ramayandi, Arief, 2015. "Taper Tantrum and Emerging Equity Market Slumps," ADB Economics Working Paper Series 451, Asian Development Bank.

Hattori, Takahiro and Yoshida, Jiro, Yield Curve Control (January 18, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3396251

International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Update, March 2021

Lim, Jamus Jerome and Mohapatra, Sanket and Stocker, Marc, Tinker, Taper, QE, Bye? The Effect of Quantitative Easing on Financial Flows to Developing Countries (March 1, 2014). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6820

Ms. Helene Poirson, 2021. "Unconventional Monetary Policies in Emerging Markets and Frontier Countries," IMF Working Papers 2021/014, International Monetary Fund.

Oo, Thida & Kueh, Jerome & Hla, Daw. (2019). Determinants of Export Performance in ASEAN Region: Panel Data Analysis. International Business Research. 12. 1. 10.5539/ibr.v12n8p1.

Pastpipatkul, Pathairat & Yamaka, Woraphon & Wiboonpongse, Aree & Sriboonchitta, Songsak. (2015). Spillovers of Quantitative Easing on Financial Markets of Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. 374-388. 10.1007/978-3-319-25135-6_35.

Pol, E. (2021), The Economic Logic of the Yield-Curve Control Policy*. Econ Pap. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-3441.12317

Ṣebnem Kalemli-Özcan, 2019. "U.S. Monetary Policy and International Risk Spillovers," NBER Working Papers 26297, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Stephanie E. Curcuru & Steven B. Kamin & Canlin Li & Marius del Giudice Rodriguez, 2018. "International Spillovers of Monetary Policy : Conventional Policy vs. Quantitative Easing," International Finance Discussion Papers 1234, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

[1] Bank of Thailand, Monetary Policy Report, June 2018

[2] https://www.krungsri.com/th/research/research-intelligence/thailand-sectoral-potential-2021