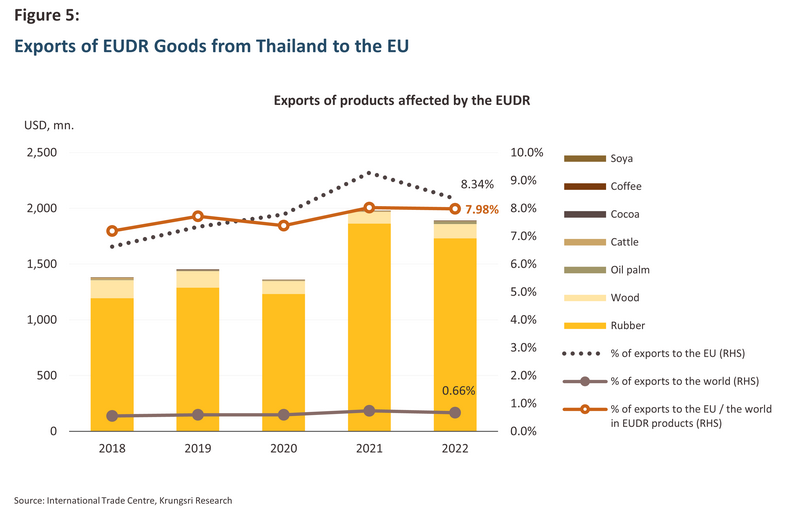

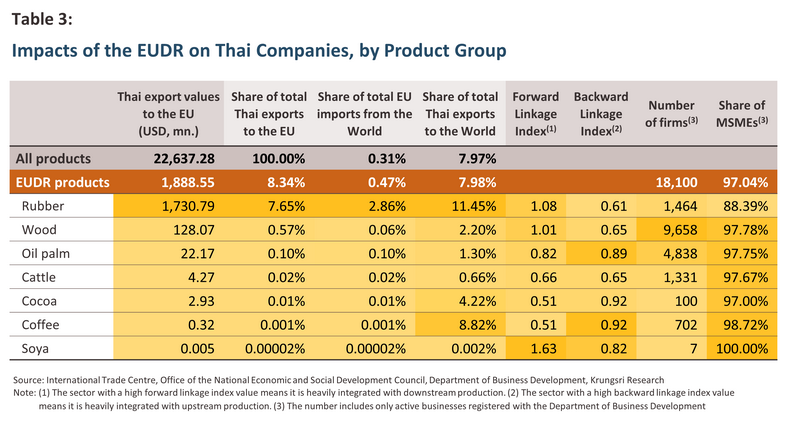

Having surveyed the positive and negative impacts of the EUDR on Thai companies overall, the following section will consider the effects of the regulations on individual industries.

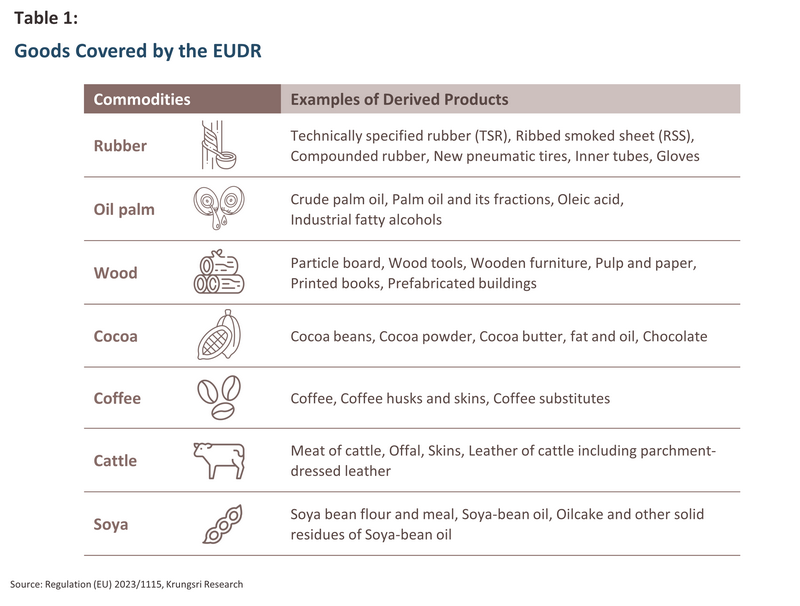

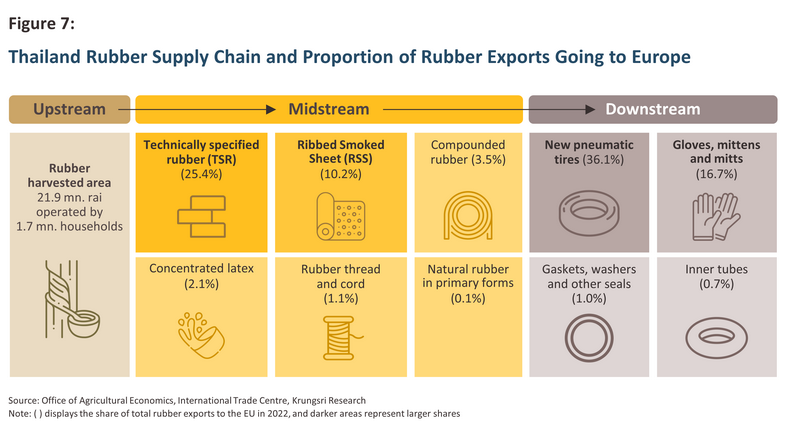

Thailand generated income worth USD 1.7 billion from exports of rubber goods to the EU in 2022, and so of the various industries covered by the EUDR, the rubber industry will be the most seriously impacted part of the economy. The upstream section of the domestic supply chain comprises rubber growers, rubber tappers, and some primary processing that converts the fresh field latex into dried products. As of 2022, 1.7 million households were involved in the cultivation of rubber, which covered a total area of 3.5 million hectares (21.9 million rai), over half of which was in the south of the country. Almost all primary production of latex is used in the manufacture of the main intermediate products of rubber smoked sheet (RSS), technically specified rubber (TSR), concentrated latex, compound rubber, and mixed rubber. These intermediate products are used by downstream industrial consumers (mostly in overseas markets) to produce end-products such as tires, latex gloves, condoms, and rubber bands, of which Thailand is also a major exporter.

The rubber products most heavily affected by the EUDR will be processed rubber goods (TSR and RSS), tires, and latex gloves since these account for the greatest share of Thai rubber exports to the EU. In 2022, Thai exports to the EU of natural rubber goods had a total value of USD 654 million, which represented 37.8% of all Thai rubber exports. Of this, the most important product categories were

TSR (25.4% of all rubber exports),

RSS (10.2% of exports) and

concentrated latex (2.1%). The importance of the European market to Thai rubber producers is reflected in the fact that the EU is respectively the 2nd and 3rd most important market for exports of TSR and RSS from Thailand, and so producers and processors of intermediate rubber goods will certainly feel the impact of the introduction of the EUDR.

At the same time, exports to Europe of downstream goods such as pneumatic tires had a total value of USD 625 million (36.1% of exports of all rubber products) and so manufacturers of these will be just as seriously affected. The most important exports from Thailand to Europe are bus, truck and auto tires, but producers of rubber apparel and clothing accessories will also be impacted, though in particular, this will hit manufacturers of latex gloves since these account for a full 16.7% of all exports of rubber goods. Moreover, because companies manufacturing downstream goods will have to carry out due diligence on their midstream and upstream suppliers, the overall burden of the additional EUDR requirements will be heavier for players in this group.

In some regards, the Thai rubber industry is reasonably well placed to respond to the introduction of the EUDR since the majority of rubber plantations (18 million rai from a total of 22 million across the country) are registered with the Rubber Authority of Thailand (RAOT)18/. Therefore, most growers can be assumed to be able to provide proof of the geographical source of their products and so to be harvesting rubber legally. However, the EUDR covers a wide range of issues relating to society and the environment, and one mechanism for demonstrating that growers have met the EUDR requirements for sustainability is international accreditation, such as that offered by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). This provides a certification and labeling system, and only wood from socially and environmentally responsible plantations (thus not from natural or reserved forests) is permitted to carry the FSC label19/.

The Rubber Authority of Thailand estimates that at present only around 64,000 hectares (400,000 rai) of Thai rubber production is certified by the FSC, or just 1.8% of the total area under cultivation across the country, and thus only a small fraction of rubber producers is likely to be in full compliance with the EUDR. Moreover, given the significant obstacles that have to be cleared before a producer can be certified and the costs involved in applying for the certification and then meeting its requirements (e.g., restrictions on the use of pesticides), it is generally only major players such as the Sri Trang Group20/ that have done so. Independent growers and small-scale processors are thus at a distinct disadvantage, though it may well be the case that the EUDR rules will entail unavoidable costs either way, whether from the additional overheads entailed by reporting and verification or from applying for international certification and then using this to meet the EUDR requirements.

Another significant challenge relates to data management and supply chain verification, and there is now a race underway to get systems for this up and running ahead of the implementation of the EUDR, though the authorities are also keeping an eye on how other EU trade partners (e.g., China, Malaysia, and Indonesia) are managing this situation. The Rubber Authority of Thailand plans to use a geographic information system (‘GIS Rubber’) to manage information relating to the location of rubber plantations and to check land deeds, and it is hoped that it will be possible to use this for provenance checking by 202521/. In the private sector, Sri Trang Group is developing ‘Sri Trang Friends Platform’, the company’s in-house system for managing and verifying the source of goods entering its supply chain, and this will help the company to expand into markets with trade partners manufacturing downstream goods22/. However, because of the nature of the EUDR stipulations, the ability of Thai players to maintain and expand market share will be highly dependent on the functioning of systems for supply chain verification.

Wood and wood products

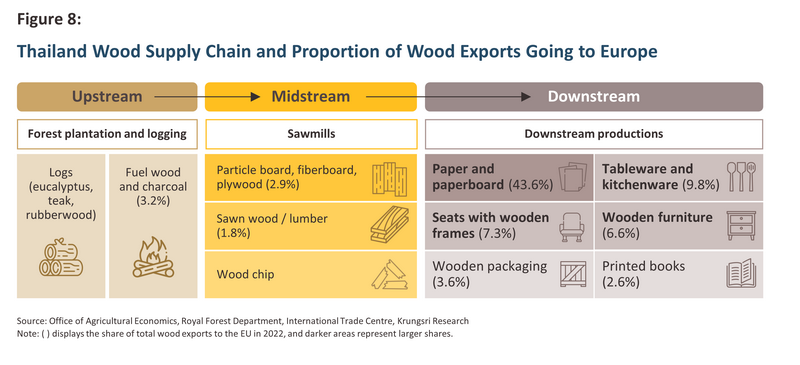

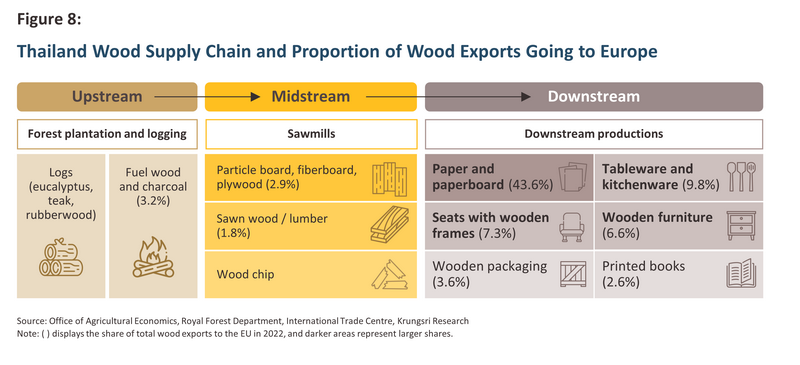

Almost all wood processed by Thai mills is sold on to Chinese manufacturers, where it is typically consumed by China’s enormous furniture industry, and so Europe is not a major export target for Thai players. Nevertheless, in 2022, exports of wood and wood products from Thailand to the EU generated income worth USD 128.1 million and so for Thailand, after rubber, wood and wood-derived goods will be the second most important category of EUDR products, and for players in this area, impacts may be significant. Indeed, of all the main commodities covered by the EUDR, wood has the broadest selection of goods associated with it. This is because of the wide range of downstream industries that use wood, and this diversity is reflected in the wood manufacturing supply chain, which is composed of the following: (i) In the upstream section of the industry supply chain, forest plantation results in felled lumber, which in Thailand is mostly eucalyptus, teak, and rubber23/ (imports are limited to a small quantity of pine and oak); (ii) In intermediate processing in sawmills24/, the felled timber is cut into sawn wood. Waste products from this (e.g., scraps and offcuts) are converted into processed wood products such as particle board and fiberboard, while waste wood chip is processed into paper. (iii) Finally, midstream processed wood is made into downstream products, such as packaging, kitchen appliances, paper, books and furniture.

The most seriously affected wood products will be downstream goods and those produced by related industries. Most notably, this will include paper products since these comprise 43.6% of all exports of wood and wood-derived products to the EU (uncoated paper and paperboard and toilet paper). This will be followed in importance by tableware and kitchen appliances (9.8% of wood exports), seats (7.3%), furniture (6.6%), carvings, statues and home decorations (3.8%), and packaging (3.6%). The quantity of processed wood products exported to the EU is fairly slight and thus only 2.9% of particle board, fiberboard, plywood and veneered products is bound for markets in Europe, indicating that direct impacts will be limited. However, Thai players will be exposed to indirect effects since over 90% of exports of Thai processed wood products go to China, Europe’s most important supplier of wooden goods, especially of furniture. However, the introduction of the EUDR and the accompanying risk of losing market share should Chinese imports contravene the new regulations may encourage Chinese manufacturers to switch to sourcing inputs from countries that are better placed to carry out due diligence. This would then place Thailand in the unwelcome position of having to compete more aggressively with countries already supplying China with processed wood, including Vietnam, Australia, New Zealand, and countries in the EU itself, and given the overwhelming importance of China for Thai exporters, this has the potential to be an important issue.

Compared to those in other parts of the economy, players in the wood industry will be at something of an advantage since exporters to Europe are already familiar with the EU Timber Regulations (EUTR), which have been in effect since 2013 and that likewise require suppliers to carry out due diligence. Under the EUTR, suppliers need to check the provenance of wood and wood products imported into the European Union and to be assured that these have been sourced legally25/, and title deeds have played an important evidential role in proving that wood has not entered the market as a result of deforestation26/. To this end, the Royal Forestry Department has played a central role overseeing the market for wood products and managing supply chains. This includes registering forest plantation, permitting logging, licensing sawmills, and certifying wood and wood-derived products prior to export, and this should all transfer smoothly to being used to demonstrate compliance with EUDR legal requirements.

In addition to its forestry conservation measures, the European Union has been pushing forward with measures to promote environmental and social sustainability, and so companies involved in the trade in wood or wood products that wish to maintain or expand their place in European markets will need to operate in line with international sustainability standards. The latter includes not only the FSC standards, which can be used to certify rubber and wood goods, but also the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), a well-regarded scheme for the certification of the sustainability of wood products. The PEFC in fact operates a meta-certification program under which it assesses and evaluates national forestry certification schemes. In the case of Thailand, this is the Thailand Forest Certification Council (TFCC), which since 2019 has been the certifying body for the PEFC27/. In keeping with those set by international bodies28/, these standards are focused on the sustainability of forestry management, labor rights, biodiversity, land use, and compliance with other relevant laws, and PEFC-accredited goods commonly include paper, wood packaging or boxes, and processed wood products.

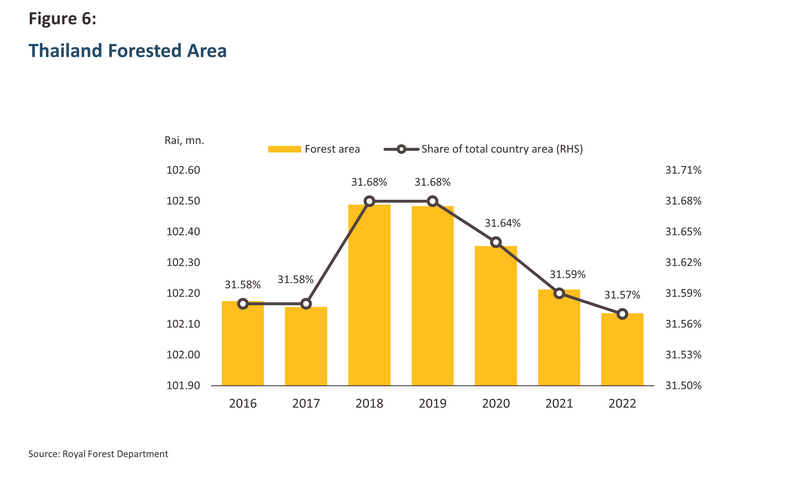

Overall, Thai exporters of wood and wood-derived products have significant potential to expand into European markets. This will be especially so for those involved in rubber wood since there is a total of 3.5 million hectares (22 million rai) of rubber under cultivation in Thailand, and rubber is alone among wood products in not being subject to export controls. However, success in this will depend on companies obtaining international certification, and failure to do so will weigh heavily on growth, in particular now that the EUDR has added to the requirements laid out in the EUTR.

Oil palm

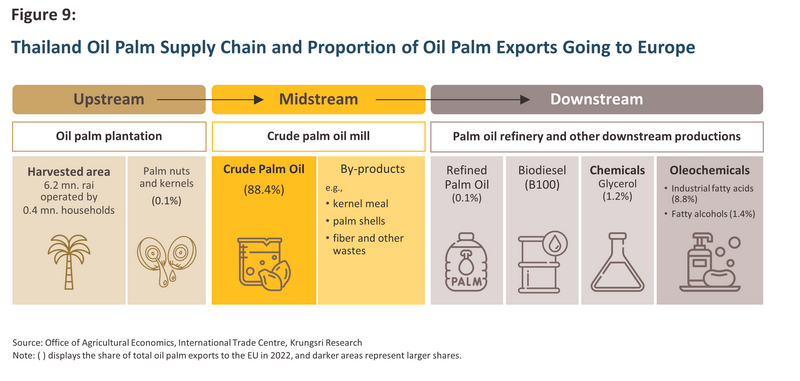

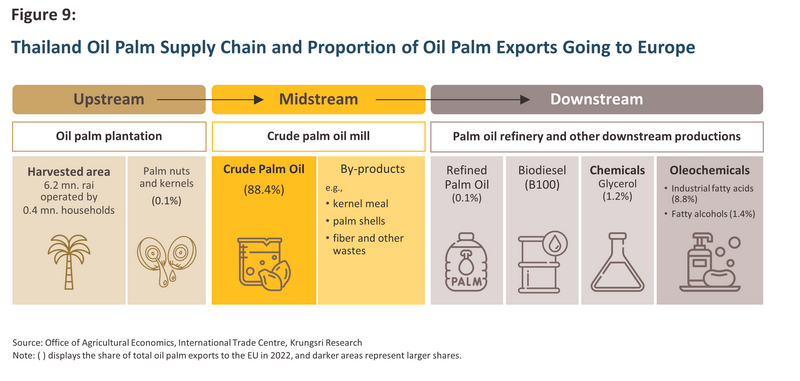

Following the rubber and wood industries, players in the oil palm industry will be the next most heavily impacted by the introduction of the EUDR. Upstream industrial production involves the growing of oil palm, with a total of 407,225 households cultivating 1 million hectares (6.2 million rai) of this across the country, though this is concentrated in the South. The number of farmers active in the industry has increased steadily, but these are overwhelmingly small independent operations. In midstream positions in the supply chain, fresh palm fruit is pressed to extract crude palm oil, with value generated from by-products (e.g., palm meal, oil cake and palm shells) that are processed into a range of secondary goods. Downstream production consists of purifying crude palm oil into refined palm oil, though in addition to this, other downstream industries include the manufacture of biodiesel, chemicals, and oleochemicals (e.g., soap and margarine).

Although Thailand is, after Indonesia and Malaysia, the third most important supplier of palm oil products to global markets, exports of EUDR palm products to Europe are fairly low, and in 2022, these brought in just USD 22.2 million. The vast majority of this (USD 19.6 million, or 88.4%) was of crude palm oil29/, though exporters of palm oil-derived chemicals will also be affected by the new rules. Chief among these will be fatty acids and fatty alcohols that are used in the oleochemicals industry (e.g., to produce soap and cleaning agents), which account for respectively 8.8% and 1.4% of exports of oil palm products. Because the value of exports to Europe of oil palm-derived chemicals is more stable than those of crude palm oil, the impacts for players in this segment should be more predictable, although supply chain checking and verification will be more complicated. For other oil palm products such as refined palm oil and palm seeds, impacts will be negligible due to the fact that exports of these amount to just 0.1% of the total.

For the oil palm industry, the challenges posed by the EUDR will be broadly similar to those faced by the rubber industry. Thus, the majority of Thai palm plantations are sited on land previously used for other agricultural purposes rather than having been recently deforested, and growers typically have legal right to this land. However, around 80% of the land given over to oil palm cultivation is managed by small, independent growers, and these are generally lacking in knowledge about how to farm sustainably, for example how best to apply fertilizer and how to re-use processed palm fruit bunches. Given this, only around 2% of growers have met the sustainability standards set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)30/. The latter certifies oil palm plantation practices across a range of areas including respect for the environment, conservation of natural resources and biodiversity, fair labor practices, respect for local communities impacted by oil palm cultivation, and compliance with relevant laws31/. These align closely with the EUDR, and so it is reasonable to conclude that because so few producers are accredited by the RSPO, a considerable amount of work remains to be done to prepare for the introduction of the EUDR.

The authorities have tried to accelerate the uptake of sustainable farming techniques. As part of this, the German international development organization (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH: GIZ)32/ has worked with around 1,000 Thai palm oil growers to help these meet the RSPO standards. The GIZ has also helped to develop the i-Palm app, which can be used by growers to store data on the location of their plantations and the growing and harvesting period of their palm. By aligning on-farm practices with the RSPO standards, growers will be well prepared for the implementation of the EUDR, and so although links between Europe and the Thai palm oil industry are fairly weak, the latter has the potential to adapt well to new circumstances and to deepen its penetration of European markets.

Other industries

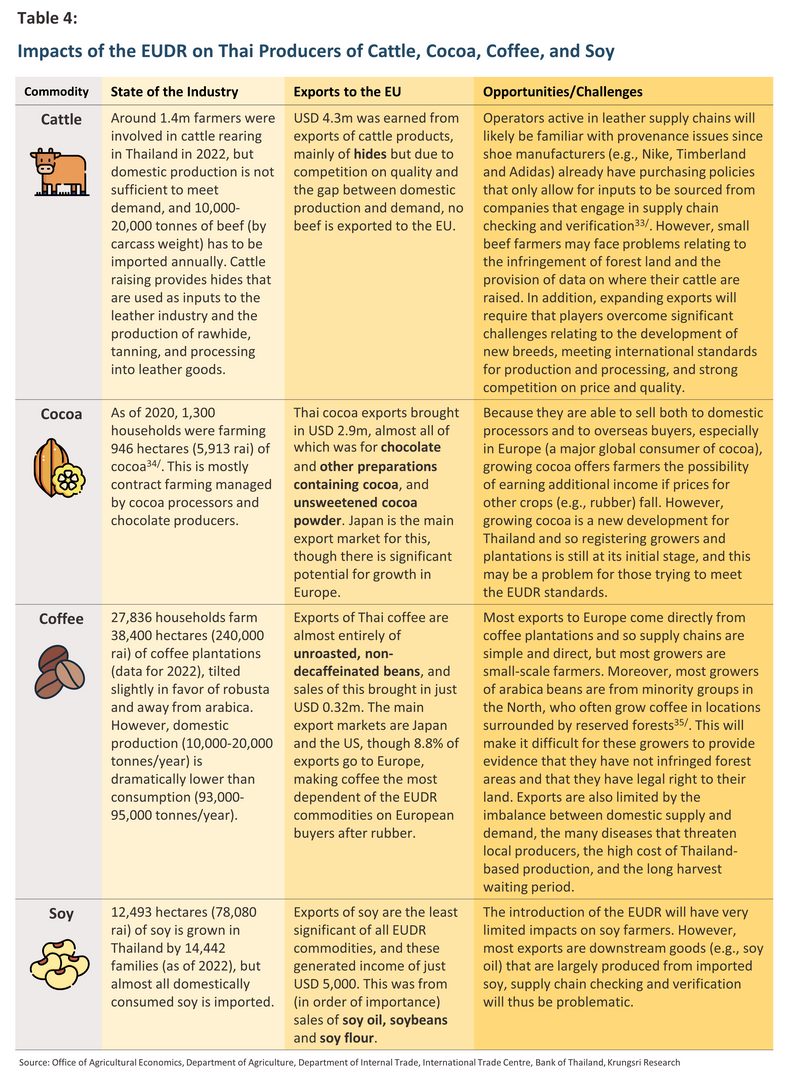

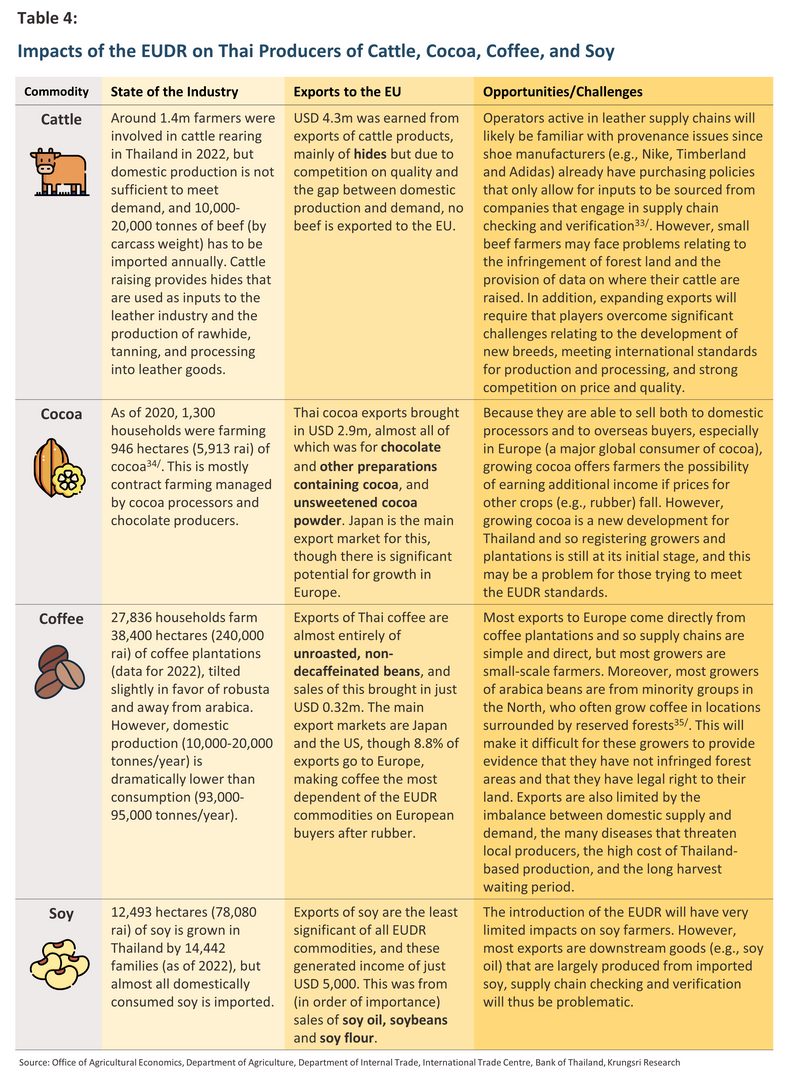

Beyond rubber, wood, and oil palm, exports from Thailand to the EU of goods covered by the EUDR are very limited and therefore the impacts on Thai industry, which are summarized in Table 4, will be slight. Nevertheless, most of those involved in these supply chains are small farmers, and because they may have difficulty providing the documentation required to show that production has not involved deforestation, in the future, they may face difficulties trading in Europe.

However, the current low level of exports to the bloc also reflects the fact that sales into the EU have significant room for growth. In particular, sales of cocoa have strong growth potential because while exports are low, the EU is still an important export market for Thai producers. Given the existence of receptive markets at home and abroad, the Thai authorities are also trying to extend cocoa cultivation. The industry will, though, face challenges arising from the need to adapt to the EUDR as well as from competition from major suppliers, such as Côte d’Ivoire, and regional competitors, including Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

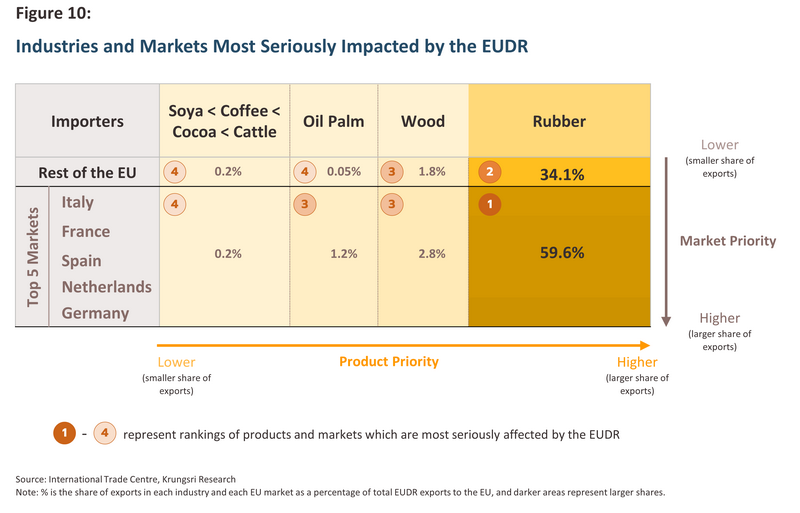

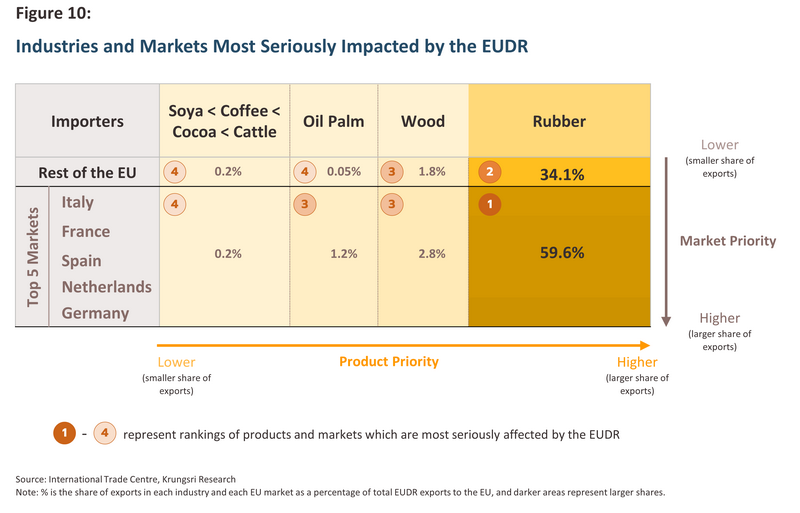

It is possible to rank the impacts arising from the EUDR and to evaluate how urgent responding to these challenges is by evaluating differences in the production and export capabilities of the industries affected by the EUDR, variations in the extent to which Thai players are dependent on overall exports to the EU, and their level of sales into particular EU member states. The results of this analysis are summarized in Figure 10, which ranks product priorities (i.e., the product’s share of overall exports) on the horizontal axis and the market priority (i.e., the market’s share of overall exports) on the vertical axis. This shows that by far the most heavily affected product-market combination is exports of rubber to the top five EU markets of Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, France and Italy, which with a 59.6% share of exports of EUDR goods to the EU should be the primary focus of adaptation measures (number 1, Figure 10). Exports of rubber to the rest of the EU (i.e., the EU excluding the top 5 markets) account for a further 34.1% of EUDR exports to Europe, placing these in second place in the rankings of importance (number 2, Figure 10). Combined, exports of rubber across the bloc thus account for 93.7% of the value of all EUDR exports, and so rubber will be by an enormous margin the industry most severely impacted by these new rules.

By comparison, other industries will be much less seriously affected, and the 6.3% of export value remaining for EUDR goods once rubber’s contribution has been deducted are split between wood and wood-derived goods (4.6%), oil palm products (1.3%) and in order, cattle products, cocoa, coffee, and soy, though with the last four, there are no significant differences between the value of exports to the top five markets and the rest of the EU, which are in any case very minor. However, it should be emphasized that this analysis considers only goods exported directly from Thailand to the European Union and the consequences arising directly from this. Indirect impacts that will be felt as a result of the export of agricultural goods, raw materials, or intermediate products to third party countries for conversion into downstream goods that are sold on to European markets are not included in this assessment.

Krungsri Research view: How should Thailand respond to changes in the rules governing world trade?

Preparing stakeholders for change

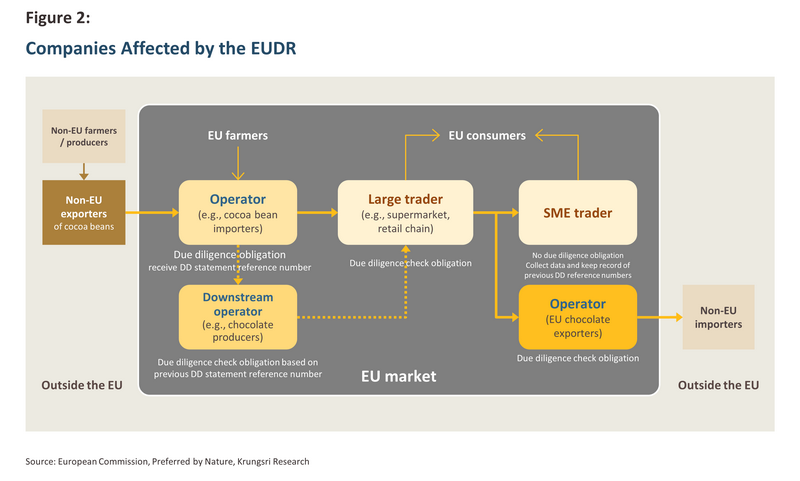

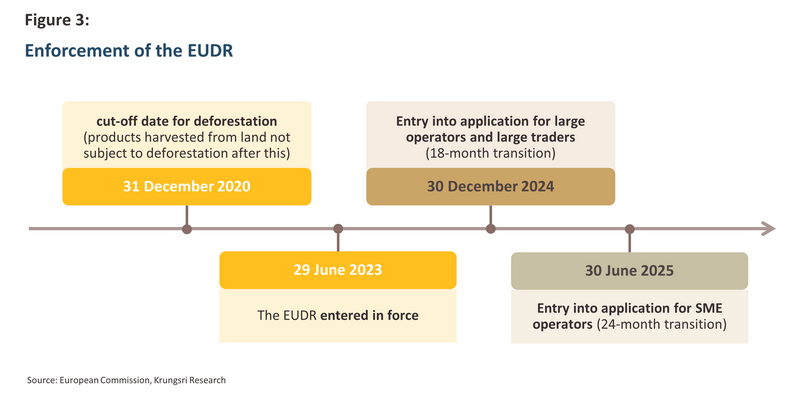

The EUDR came into force in June 2023, sending a clear signal that Thailand needs to rapidly understand and adapt to a changing environment within which trade rules and the drive to sustainability have become much more closely intertwined. It is true that at present the regulations are in a transitionary stage and how these will be enforced should become clearer in 2024, but at least initially, Krungsri Research sees the impacts of the EUDR on Thai industry being somewhat limited. As demonstrated above, the most significant consequences will be for rubber supply chains, and to a lesser extent, the wood and oil palm industries, and so Thai exporters shipping these products to Europe will need to shoulder higher costs arising from data collection and processing, supply chain checking and verification, and applying for international accreditation. Failure to do this will result in non-compliance with the EUDR standards, and thus potentially being excluded from EU markets and global supply chains.

Over the longer term, the impacts of the EUDR are likely to deepen as a result of: (i) assessing and classifying countries according to the risk of their continuing to engage in deforestation and of infringing other relevant regulations; (ii) the broadening of the rules to encompass other products, which are likely to include a wider range of agricultural produce, livestock, and downstream goods; and (iii) the introduction of similar measures in areas beyond the EU.

To prepare for these changes and to alleviate any negative consequences that may arise from this over both the short and long term, it is important that stakeholders in both the public and private sectors undertake the following.

- Ensure that Thailand is categorized as a low-risk country: This will reduce the administrative and financial burdens associated with carrying out due diligence checks prior to the export of EUDR goods to the European Union and obviate the need for European importers to switch to alternative, lower risk suppliers. Both during the EUDR’s transitionary phase, when the EU is assessing individual country’s risk status (due to be announced in 2024), and in future, when the risk categories will be reviewed, it is imperative that Thailand makes clear its readiness to meet the EUDR requirements. This will include: (i) revising the procedures for permitting and licensing for, e.g., land ownership, commercial use of forested areas, and logging to make these quicker and more responsive; (ii) developing agricultural and business data gathering and storage systems that will allow for provenance and supply chain checking; and (iii) effectively enforcing laws and regulations relating to environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. With regard to the latter, laws are in fact already on the statute book covering land usage, labor rights, the environment, taxation, and corruption, but enforcement can be patchy and irregular, and so checking for compliance needs to be tightened. It is also important that in addition to work in the public sphere, awareness of these issues is improved across the private sector.

- Extend support for SMEs: SMEs will find it more difficult than large companies to adjust to the EU’s new requirements, and so these will be disproportionately heavily impacted by the risk of being excluded from domestic and international supply chains. Independent farmers and SMEs, which constitute the greatest share of participants in EUDR value chains, should therefore be offered assistance to help understand these changes and to prepare the required documentation (e.g., to show that they have the right to use the land that has been farmed and its location). Farmers should also be trained on how to farm according to international sustainability standards.

- Promote sustainability accreditation: Although the EUDR does not specify that successful completion of the due diligence checks requires that suppliers be accredited, doing so provides additional evidence that goods being imported into the EU have been produced in line with recognized international environmental and social standards. For example, the FSC and PEFC standards offer assurances that wood and rubber products originate from responsibly managed forests or plantations, while the RSPO offers similar assurances that palm oil products have been produced sustainably. The authorities should therefore support efforts to educate farmers and businesses about these standards and to build capacity in these areas. This should include financial support as part of the Board of Investment’s Smart and Sustainable Industry project, which helps with the costs entailed in developing operations to meet international sustainability standards36/. Businesses will also need to take responsibility for educating themselves about the importance of these issues and for investing in the changes needed to align their operations with international trends in improving sustainability.

Opportunities for business and the financial sector

While it is true that the EUDR regulations will apply equally to suppliers in countries around the world, the latter will have markedly different abilities to respond to these challenges. This means that if Thailand is able to steal a march on its competitors by preparing to meet these changes swiftly and efficiently, Thai exporters will be well placed to expand their share of European markets. Moreover, this need not be limited to areas where Thailand already exports in volume (e.g., rubber, wood, and oil palm products), since opportunities will certainly present themselves in markets where Thailand has demonstrable growth potential (e.g., cocoa). Thai companies will also have the opportunity to expand their presence in global value chains by stepping up exports of intermediate goods where Thailand has a competitive advantage (e.g., processed rubber and wood products), which will be processed into downstream goods in third-party countries and then exported into Europe. Other, less direct business benefits that will flow from increased attention to issues connected to sustainability will include improvements to corporate or brand image, and this may then make it easier for companies to expand their business or to raise funds, for example by being included in the Thailand Sustainability Investment index (THSI). More broadly, deepening concerns with sustainability across society will help to improve forest conservation efforts and to accelerate the accomplishment of net zero goals.

The EUDR will also generate new opportunities and open up markets for new services, including for example the development of systems to help with supply chain checking and verification, consultancy services relating to potentially complicated and involved due diligence requirements, and international sustainability accreditation. Thus, while it is true that on the tails-side of the EUDR coin, the introduction of new regulations will add to the burdens faced by exporters, for those who correctly call heads, the EUDR will open the door to a wealth of new possibilities.

Beyond its effects on the real economy, the EUDR also has the potential to impact the financial system. The EU will review the implementation of these rules after two years, and these may then be expanded to include blocks on the financing or investing in operations connected to deforestation. However, if players in the financial system become more alert to these issues, they will be able to place themselves at the center of moves to deepen business sustainability and to become drivers of environmentally and socially sustainable growth, which would ultimately establish a new set of global practices.

The EU has a history of breaking new regulatory ground that the rest of the world then follows, and as with the introduction of the CBAM, which many countries are now considering using as a model for their own cross-border carbon taxes, the EUDR will likely serve as a global prototype for further measures to tackle ongoing deforestation and address environmental issues. If, as seems likely, the EUDR has an outsize influence on the development of global trade and environmental regulations, Thailand should use the time it has to prepare as fully as possible for these changes, and through this, position itself to seize future trade and investment possibilities.

References

Directorate-General for Environment. (2023). “FAQ – EU deforestation Regulation”. Retrieved from https://environment.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-06/FAQ%20-%20Deforestation%20Regulation_1.pdf

Lopes, Cristina L., Joana Chiavari, and Maria Eduarda Segovia. (2023). “Brazilian Environmental Policies and the New European Union Regulation for Deforestation-Free Products: Opportunities and Challenges”. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Brazilian-Environmental-Policies-and-the-New-EUDR.pdf

Official Journal of the European Union. (2023). “Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation and repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010 (Text with EEA relevance)”. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023R1115

Office of Agricultural Economics. (2023). “Agricultural economic information by product, year 2022”. Retrieved from

Phichitphon Kaewngam. (2019). “Rubber wood, value and opportunities in the Thai wood industry”. Retrieved from

Ratchanapak Innukul, Pattareeya Nuanyai and Naraporn Sangsana. (2021). “How to unlock Thai cocoa...so we can go further”. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/th/research-and-publications/articles-and-publications/articles/regional-articles/reg-article-2021-07.html

Solidaridad Network, The Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries, and The Netherlands Oils and Fats Industry. (2023). “Briefing Paper: Implications of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) for oil palm smallholders”. Retrieved from https://www.solidaridadnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Briefing-paper-EUDR-and-palm-oil-smallholders.pdf

1/ Deforestation means the conversion of forest to agricultural use, whether human-induced or not

2/ Forest degradation means structural changes to forest cover, taking the form of the conversion of (i) primary forests or naturally regenerating forests into plantation forests or into other wooded land; or (ii) primary forests into planted forests.

3/ Companies may prepare and submit their due diligence statement themselves or they may appoint an authorized representative to do this on their behalf. However, at present, the EUDR law does not provide details on appointing an authorized representative, but this will likely follow in subsidiary regulations to be issued by the EU. At present, companies offering due diligence related services include Global Traceability, TraceX, Know Your Vendor and Satelligence.

4/ Source : European Union Law, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1115/oj

5/ Operator means any natural or legal person who places relevant products on the market or exports them.

6/ Trader means any person in the supply chain other than the operator who makes relevant products available on the EU market, such as large supermarket or retail chains.

7/ SMEs (including micro enterprises) in the EU refer to enterprises which on their balance sheet dates do not exceed the limits of at least two of the three following criteria: (i) balance sheet total of EUR 20m, (ii) net turnover of EUR 40m, and (iii) 250 employees (Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013L0034)

8/ Source : S&P Global, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/deforestation-rules-impact-on-supply-chains.html

9/ Source : Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/brazilian-environmental-policies-and-the-new-european-union-regulation-for-deforestation-free-products-opportunities-and-challenges/

10/ Source : International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), https://www.iisd.org/articles/policy-analysis/ppms-rise-new-sustainability-oriented-trade-policies-process-production-methods

11/ The 17 countries are: Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Paraguay, Peru, and Thailand (source: https://www.matichon.co.th/foreign/news_4173622)

12/ Source : Resilient communities, sustainable and equitable forest landscapes, https://www.recoftc.org/stories/what-eu-regulation-deforestation-free-products-means-communities-and-smallholders-asia

13/ Source : S&P Global, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/deforestation-rules-impact-on-supply-chains.html

14/ Source : Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), https://www.thai-german-cooperation.info/th/eudr-a-trade-barrier-or-an-opportunity-for-the-thai-palm-oil-industry/

15/ Source : Seub Nakhasathien Foundation, https://www.seub.or.th/document/สถานการณ์ป่าไม้ไทย/2023-235/

16/ Land use change involves an alteration in the use made of a given area of land. This will be done to meet particular social, economic or environmental needs, and the change may be temporary or permanent. A common change involves the conversion of forested land to agricultural use

17/ The 20-year strategic plan lays out the goal of extending national forest coverage to 55% of the country, split between 35% natural forests, 15% forest plantations, and 5% green areas in urban and rural locations.

18/ Source : Thansettakij, https://www.thansettakij.com/business/trade-agriculture/577663

19/ The most important FSC requirements are closely aligned with those of the EUDR, including e.g., conservation of forests, ecosystems and the environment, fair employment practices, respect for the rights of indigenous peoples, and compliance with relevant laws (Source : https://fsc.org/en/fsc-standards)

20/ Source : Sri Trang Agro-Industry Plc., https://www.sritranggroup.com/th/news-update/company-news/view?id=507

21/ Source : Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, https://www.moac.go.th/news-preview-451291792895

22/ Source : Thaipublica, https://thaipublica.org/2023/08/sta-sri-trang-friends-platform-eudr-pr-11082023/

23/ Data on timber production comes from the Forest Industry Organization, https://forestinfo.forest.go.th/Content.aspx?id=9

24/ As of 2021, there were 5,761 sawmills in Thailand (data from the Royal Forestry Department and the Office of Agricultural Economics).

25/ Source : Rubber Intelligence Unit (Office of Industrial Economics), http://rubber.oie.go.th/file/1_EU%20Timber%20Regulation.pdf

26/ Source : Thai-EU FLEGT Secretariat Office (TEFSO), https://tefso.org/th/ความพร้อมของอุตสาหกรรม/

27/ Source : Office of Industrial Economics,

28/ Source : Rubber Intelligence Unit (Office of Industrial Economics), https://rubber.oie.go.th/file/PEFC.pdf

29/ The value of exports of crude palm oil from Thailand to the EU can be highly volatile, and while this was significant in 2022, in 2021, it was very slight. Domestic palm outputs have an important role to play in determining overall export volume.

30/ Source: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), https://www.asean-agrifood.org/palm-oil-thai/

31/ Source : The British Standards Institution (bsi.), https://www.bsigroup.com/th-TH/RSPO-for-Sustainable-Palm-Oil/rspo-principles-and-criteria/

32/ GIZ assistance was made through the Sustainable and Climate-Friendly Palm Oil Production and Procurement project (SCPOPP). For more details, see: https://www.thai-german-cooperation.info/th/eudr-a-trade-barrier-or-an-opportunity-for-the-thai-palm-oil-industry/

33/ Source : Thai-EU FLEGT Secretariat Office (TEFSO), https://tefso.org/th/อุตสาหกรรมหนังและอาหาร/

34/ Source : Bank of Thailand, https://www.bot.or.th/content/dam/bot/documents/th/research-and-publications/article/regional/2564/2564_RL_07_unlock_coco.PDF

35/ Source : The 101 .World, https://www.the101.world/gastro-politics-ep-3/

36/ The Smart and Sustainable Industry project began at the start of 2023, and for the period January-September 2023, applications for assistance for 223 sustainability projects with a total value of THB 12.33bn had been received https://www.boi.go.th/th/smart_sustainable