Carbon credits are a tool for decarbonizing the economy that work by allowing organizations or individuals to set greenhouse gas reductions made in an accredited project against other emissions. Once a project has been certified, credits for its emissions reductions can be traded on a carbon market, and the credits then provide a mechanism by which the buyer can offset their own emissions against greenhouse gas reductions made elsewhere, and through this, move towards carbon neutrality. At present, the market for carbon credits in Thailand is small and underdeveloped, but it is growing rapidly in terms of both trade volume and carbon prices, and going forward, the many pledges made at corporate and national levels to sustainable growth and to hitting net zero mean that its potential for growth is considerable, with demand in particular coming from energy, aviation, finance and conference organizers. On the supply side, carbon credits will originate from the energy, transportation, agricultural and forestry industries, though the last of these and in particular ongoing efforts at reforestation will have an especially important role to play in generating high-quality credits. Nevertheless, despite this positive outlook, the Thai carbon credit market faces a number of more immediate challenges, including high project implementation costs, the disordered state of the regulatory environment, and a lack of enforcement of the relevant laws. Nevertheless, once these problems are overcome, the unstoppable rise in global interest in the green economy will ensure that new players will enter the market in increasing numbers, and that the market itself will balloon in size.

What are carbon credits, and why do they matter?

Understanding the carbon market

With the consequences of climate change increasingly evident in the day-to-day lives of people around the world, this is no longer a theory to be debated or a problem to be put off to another day. Indeed, July 2023 was the hottest month in the instrumental record, and the rapid emergence of global warming as a worldwide threat recently prompted United Nations secretary general Antonio Guterres to warn that, “The era of global warming has ended. The era of global boiling has arrived.”1/

In recent years, organizations, stakeholders and nations worldwide have made ever-more ambitious efforts to address problems related to climate change. Among these, one approach commonly used by policymakers attempting to accelerate the transition to a green economy has been to rely on market or pricing mechanisms. Carbon pricing thus attempts to establish a cost associated with the release of carbon that emitters are required to pay, which, it is thought, then encourages a reduction in emissions of greenhouse gases. This may take the form of a carbon tax set at a particular rate per unit of carbon to be collected at the point of emission (i.e., an emission tax), or it could be based on the use of a product, for example, by charging a rate determined by the quantity of carbon in oil products2/. The most important mechanisms by which emissions are traded are described below.

- Emissions trading schemes (ETS) allow organizations to emit greenhouse gases only when they have an allowance to do so. Under these systems, the government sets a ceiling on total emissions and then provides businesses with a limited quantity of permits to emit, which may be traded so that companies can then release emissions in excess of their allowance if they can find a counterparty willing to sell them their permits. These are therefore called ‘cap and trade’ systems, and generally these operate as regulatory tools at the organizational level, primarily for large emitters (i.e., they are site-based or facility-based mechanisms). Examples of ETS schemes that have been implemented to reduce greenhouse gas emissions include those in the EU, the UK and China.

- Trading in carbon credits provides a means for organizations to trade in the reductions or capture of greenhouse gases made by certified projects (i.e., this is a kind of project-based mechanism.) Under these schemes, companies may buy credits generated by reductions made elsewhere and then use these to count against their own emissions.

In addition, carbon markets may be divided according to the level of enforcement. Markets such as the EU ETS are compulsory, and companies may be punished for non-compliance with the relevant laws, whereas other markets are voluntary, and participants are free to participate or not as they wish. The Thai carbon market is of the latter type. This paper focuses primarily on carbon credits since the market for these will likely expand, and as both Thailand and the world move towards a greening of business, opportunities in this area will multiply.

What are carbon credits?

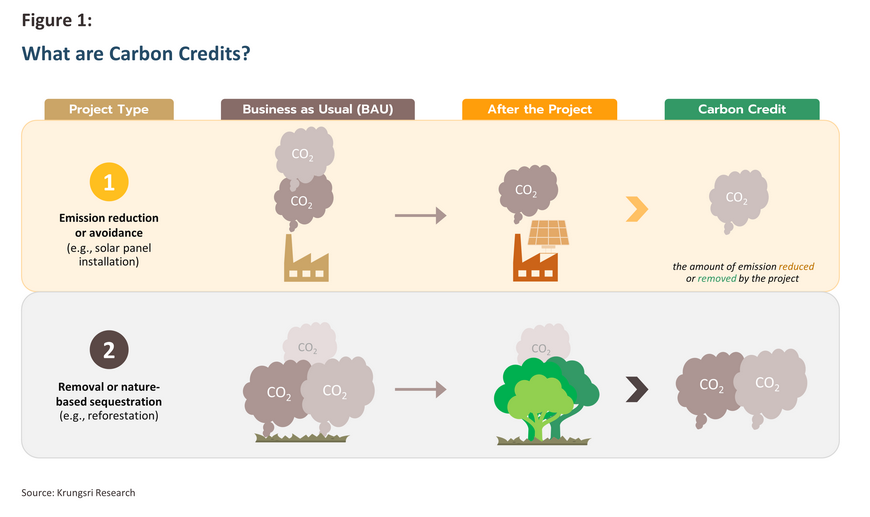

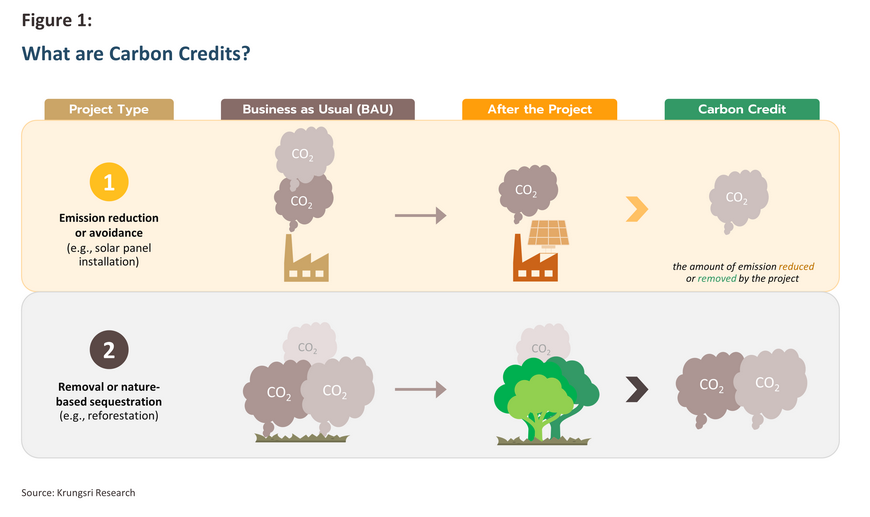

Carbon credits are a way of accounting for and benefiting from reductions in greenhouse gas emissions that are associated with a particular project and that happen in excess of baseline expectations under a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario. To account for the different warming potential of different greenhouse gases, these are all converted into a single metric, carbon dioxide equivalent, which is then measured in tonnes (tCO2e). These reductions need to be verified, but once this has happened, they can then be traded between those who have achieved these reductions and those who wish to offset their own. This then provides for a mechanism that incentivizes parties to attempt to increase revenue by maximizing greenhouse gas reductions.

There are two principal sources of carbon credits: (i) emissions reduction or avoidance schemes, e.g., clean energy projects, improving energy efficiency, and better waste management; and (ii) emissions removal or nature-based sequestration schemes, e.g., carbon capture and storage technology, and reforestation programs. Greenhouse gas emissions relative to the BAU baseline need to be verified and registered by an approved authority, but once these have been recorded as carbon credits, supply from those responsible for emissions reductions can meet demand from those in the market for offsets.

The highest profile and most widely accepted international carbon credit mechanisms are the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), an international scheme developed by the UN, the Gold Standard (GS), developed by the WWF and other nonprofits, and the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), which is run by Verra. Thailand also has its own carbon credit scheme, the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Project (T-VER). At the international level, the most widely accepted and used of these is the VCS, which accounted for 42% of all carbon credits sold globally over 2018 to 2022, followed by the CDM (32%) and the GS (8.2%). Thailand’s T-VER scheme covers just 0.8% of the world’s carbon credits3/.

What is the point of carbon credits?

Carbon credits fulfil a useful function since while many organizations realize the importance of addressing looming environmental threats, some are unable at present to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions and so instead these rely on alternative mechanisms to reach this goal. Carbon credits are one way of doing this and of compensating for a company’s own emissions, whether those are at the organizational level, for a particular product or event, or for an individual’s emissions. These therefore provide a mechanism for achieving carbon neutrality, that is, the point when an organization’s emissions are in balance with reductions in emissions, the latter being achieved through the three means of reductions, drawdowns, and offsets4/.

The use of carbon credit mechanisms promotes the development of more efficient strategies for the reduction and capture of greenhouse gas emissions, including the development of new technologies to achieve these ends. In addition, improvements in measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) naturally follow from this since these are a core determinant of how successful carbon credit schemes are. Moreover, from the point of view of the buyer of carbon credits and their PR efforts, it is important to be able to report honestly and faithfully on corporate efforts to increase sustainability5/, which in turn affects the ability of project operators to generate income from the sale of credits.

Beyond this, carbon credits that have been generated by reductions in greenhouse gases can be traded internationally, as per Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, though this is subject to tracking and restrictions that aim to reduce problems with double counting. Operators of carbon credit schemes may thus benefit from selling not just at the national level, but also by trading on international markets that have been established to encourage the transition to a more sustainable economy.

The state of global carbon credit markets

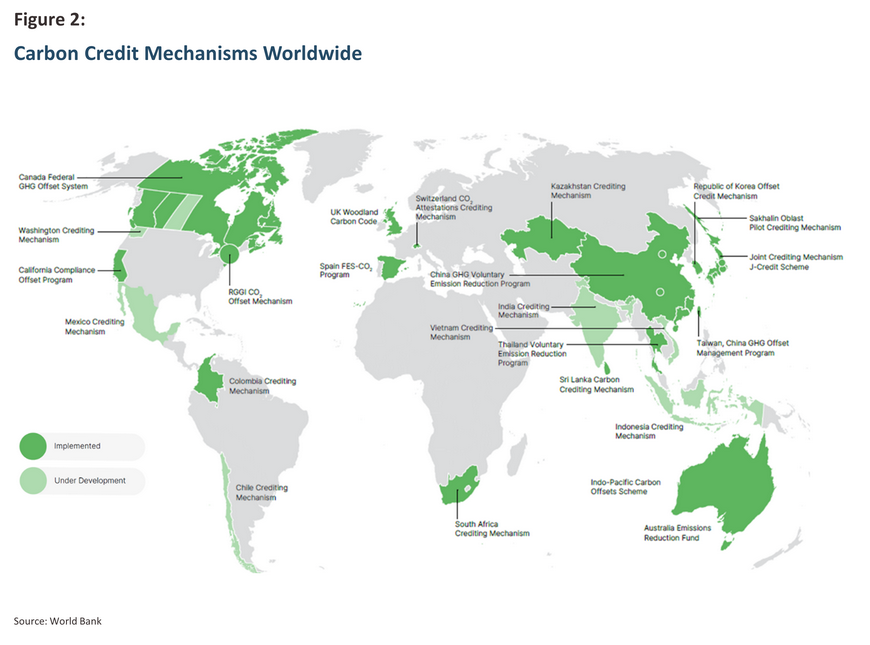

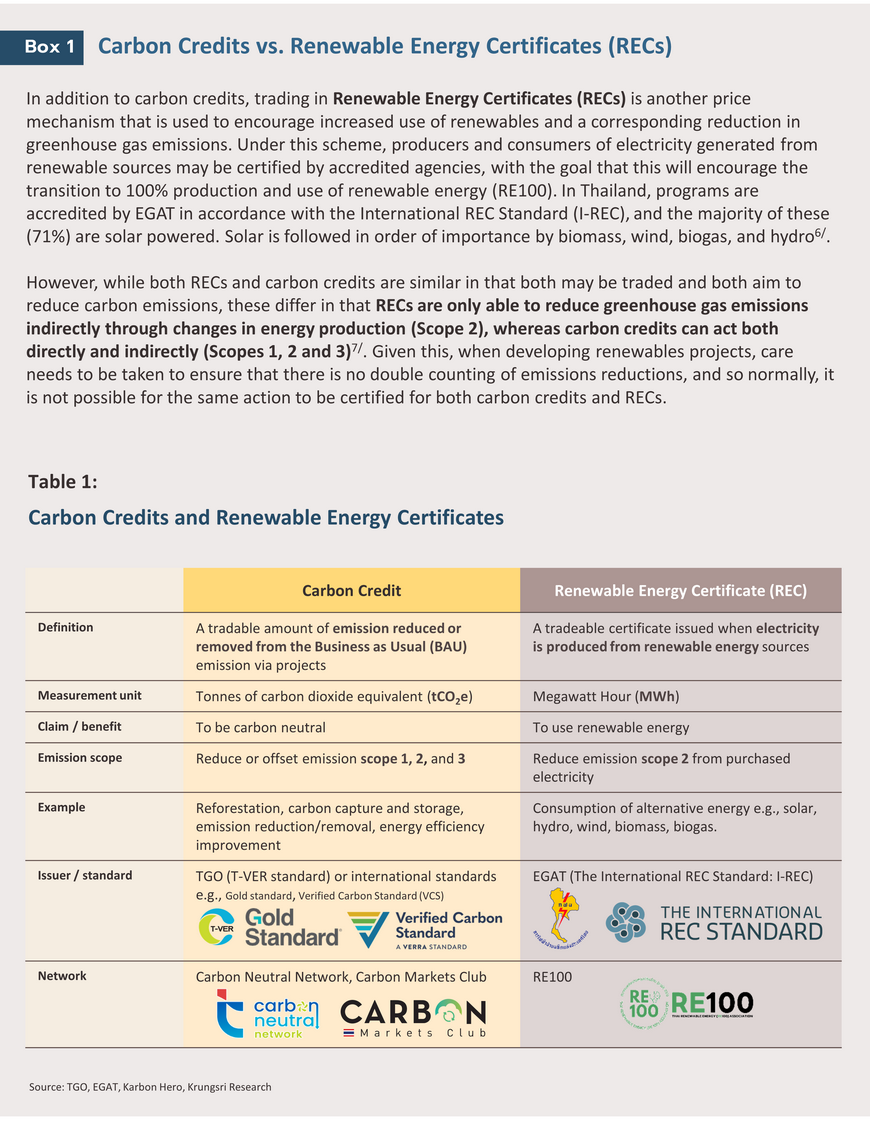

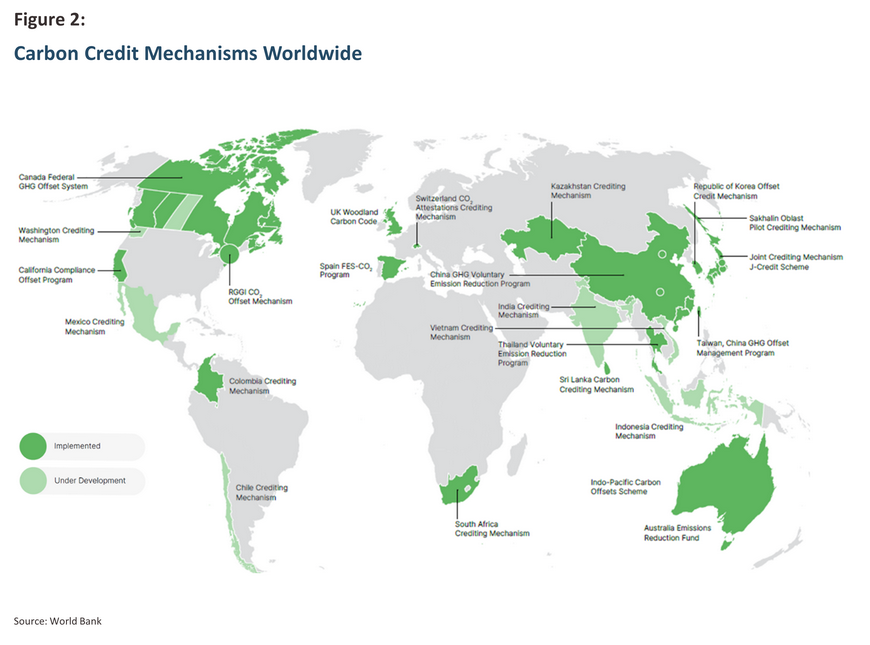

The World Bank’s 2023 report ‘State and Trends of Carbon Pricing’ shows that over 2018-2022, the volume of carbon credits traded globally rose steadily, reaching a total of 475 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2022. These credits originated mostly from private sector organizations such as VCS and GS, though an increasing proportion of credits are being certified by national and international organizations, as might be expected given the rising number of domestic carbon credit verification mechanisms being established around the world at both national and state levels. These often operate alongside ETS schemes or carbon taxes since these kinds of pricing mechanisms generally increase demand for carbon credits. In the case of Thailand’s regional peers, both Indonesia and Vietnam rolled out their own carbon credit schemes in 2022, and India is in the process of passing a law establishing a system for verifying carbon credits and operating a domestic ETS scheme.

Globally, alternative energy projects have been the most important source of carbon credits, and as of 2022, these accounted for 55% of the total. However, the cost of switching from fossil fuels to alternative energy is falling and so rather than buying credits from another organization that has made this change, companies are increasingly doing this themselves. Instead, nature-based sequestration (e.g., reforestation projects) is taking on a more important role, and so in 2022, forestry and land use projects accounted for 54% of newly registered schemes.

How is the Thai market for carbon credits developing?

Within Thailand, the market for carbon credits is managed by the Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization, or the TGO, which began development of a voluntary carbon market in 2012. This covered: (i) trading in carbon credits from voluntary reduction programs that met international standards (i.e., verified reductions in emission); and (ii) trading in carbon credits from voluntary reduction programs that met domestic Thai standards (the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Project, or T-VER). In addition, the TGO began operating the Thailand Voluntary Emissions Trading Scheme (TVETS) in 2015, with this initially covering the 10 pilot industries of petrochemicals, cement, iron and steel, paper and paper pulp, food and drink, plastics, oil refining, glass manufacturing, ceramics, and textiles8/.

The T-VER, Thailand’s own carbon credit scheme

At present, the Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction (T-VER) scheme is the most developed carbon market in the country. This is run by the TGO, which registers projects and certifies their emissions reductions. Parties wishing to enter this market may do so through a wide range of undertakings, such as developing renewable energy projects, improving energy efficiency, reforestation schemes, better transport management, improved waste management, and improvements to the agricultural system. Because this list spans such a wide range of areas, the means of calculating emissions reductions and the resulting carbon credits will vary according to the details of each project. For example, credits for planting trees, reforestation programs, and forest conservation and restoration projects will typically be calculated over a 10-year time span, whereas generally, calculations are made over 7 years9/.

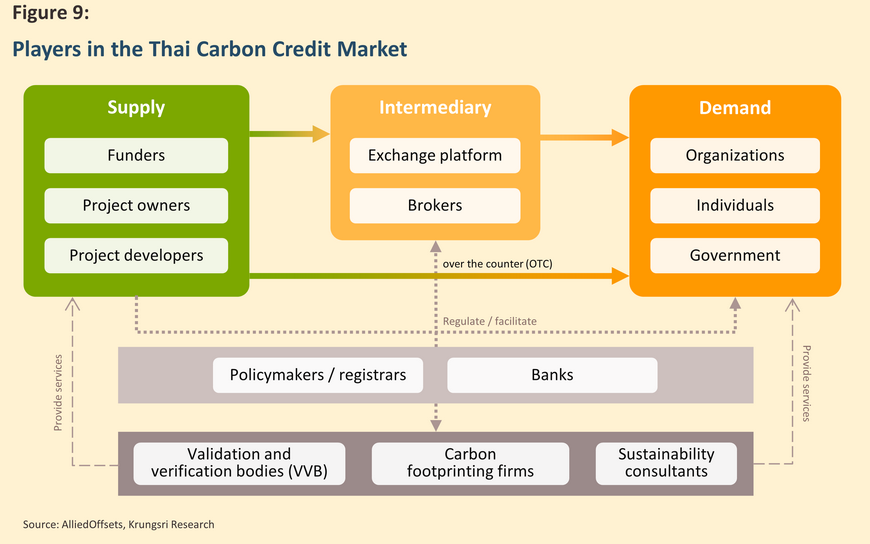

In addition to the TGO and the developers of carbon credit projects themselves, a third key stakeholder in the T-VER process is the validation and verification bodies (VVBs). These are registered with the TGO10/ to perform the vital task of validating projects prior to their being registered and then verifying the extent of carbon sequestration that is associated with that project. Once this has been completed, an application for carbon credits will be submitted to the TGO.

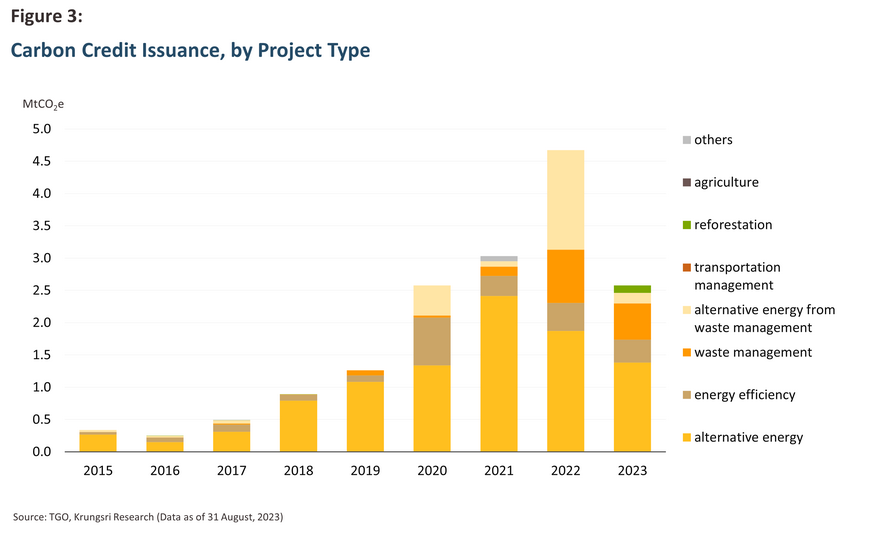

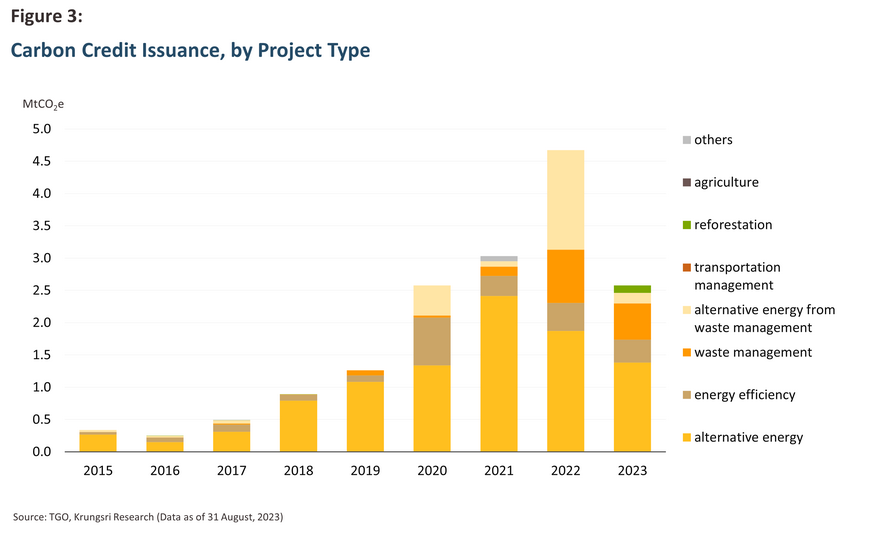

The volume of carbon credits issued by the TGO has risen steadily since the inception of the T-VER scheme (Figure 3). 2022 saw a strong uptick in activity, with 4.7 MtCO2e of credits assigned to 59 projects, and as of 31 August, 2023, a total of 16.1 MtCO2e of emissions reductions from 298 projects had been accredited by the TGO. Unfortunately, although issuance of carbon credits is growing strongly, reductions made under the T-VER scheme in 2022 accounted for just 1.2% of all Thai greenhouse gas emissions11/.

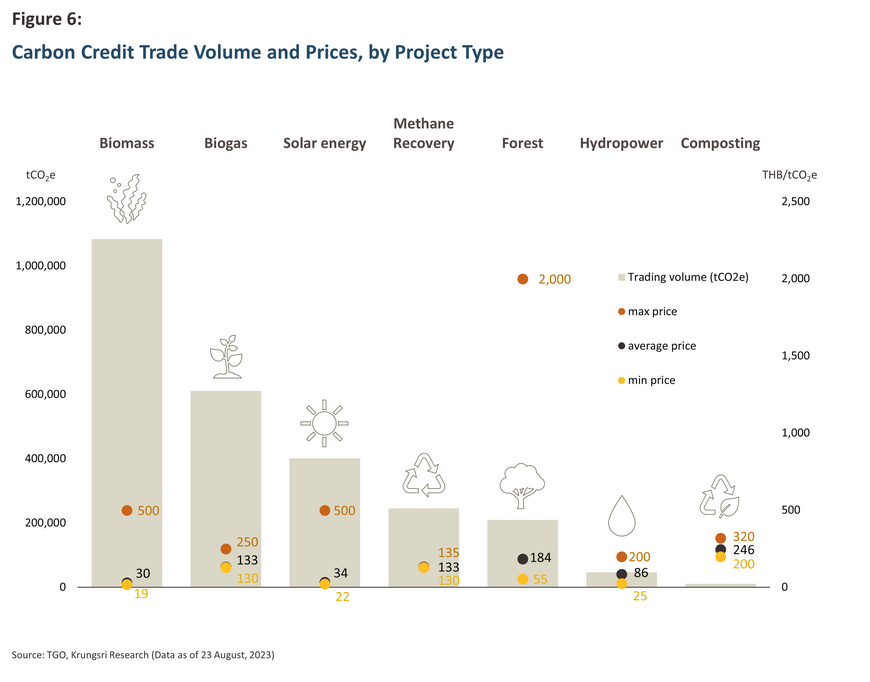

The majority of T-VER projects are for biomass, biogas and solar energy, as well as for improvements to energy efficiency, but in 2023, an increasing number of carbon credits were issued for waste management and reforestation projects, and the growing importance of Thai tree-planting and reforestation efforts reflects the increased global recognition of carbon credit markets, as described above.

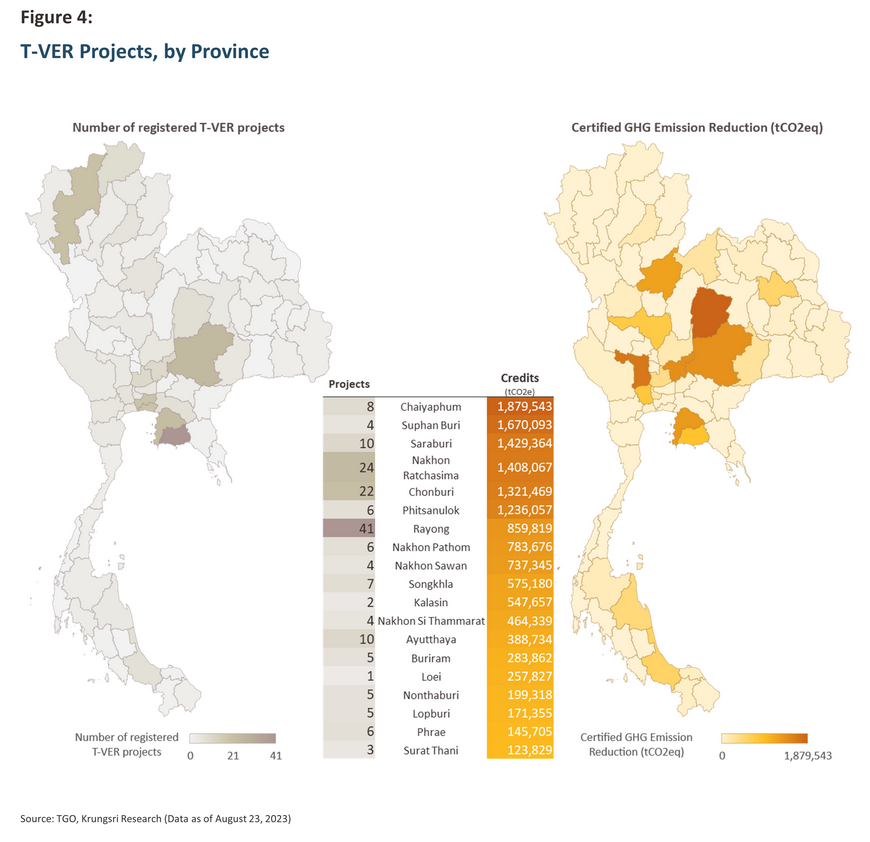

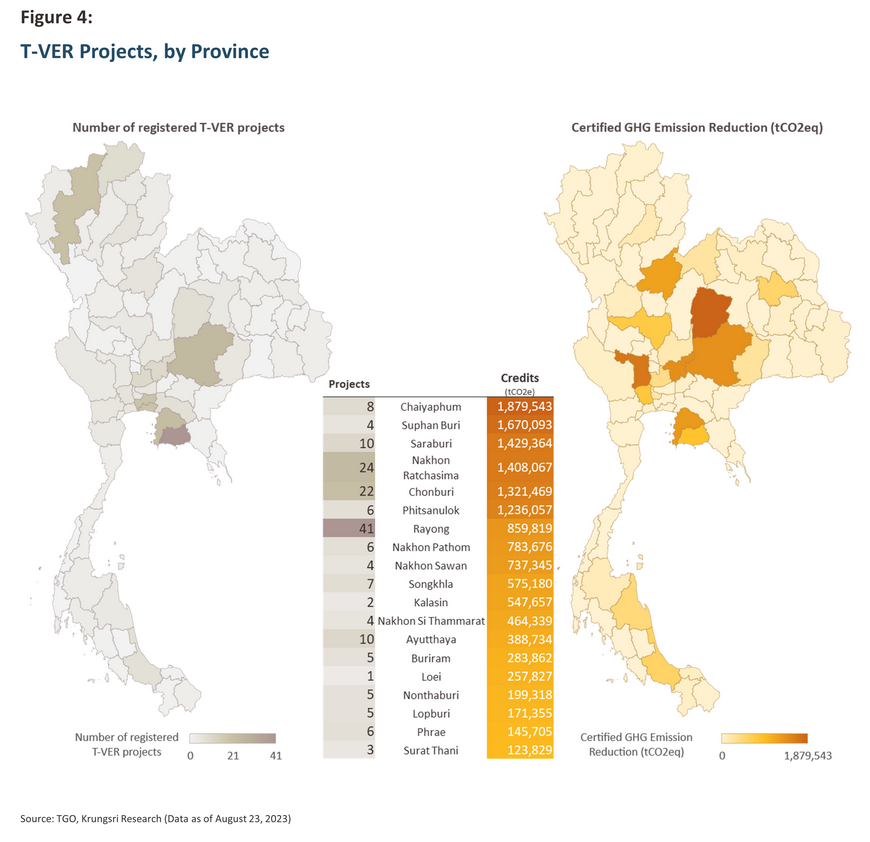

Projects registered with T-VER are most concentrated in Rayong, which is followed in importance by Nakhon Ratchasima, Chonburi, Chiang Mai, Samut Prakan, and Bangkok (Figure 4), likely because these provinces are more economically active than elsewhere. However, when looking at the total number of carbon credits that have been issued, the situation changes and although Chaiyaphum, Suphanburi, and Saraburi are home to a relatively small number of registered projects, these have made an outsized contribution to lowering emissions of greenhouse gases. In the case of Chaiyaphum, all the province’s carbon credits are issued for renewables projects, these including Mitr Phol Bio-Power’s biomass energy plant and wind power generation by the Hanuman Wind Farm Project (many companies have participated in this). Mitr Phol Bio-Power also operates large-scale biomass energy plants in Suphanburi, Kalasin, and Loei.

One example of an energy efficiency project that has been registered for the issuance of carbon credits is Top SPP’s combined-cycle co-generation power plant in Chonburi, which is estimated to help reduce annual emissions by as much as 335,674 tCO2e. Likewise, TPI Polene’s project to run a power plant in Saraburi on municipal solid waste has also earned a large number of carbon credits12/.

Although T-VER projects connected to agriculture, forestry, and transport management have not yet generated a significant volume of carbon credits, some interesting projects can still be found in these areas.

- Transport management: Examples of companies earning carbon credits by switching to electric vehicles include the use of e-buses for staff transport by SCG Chemicals and electric-powered tuk tuks by MuvMi Hero, while PTT is using bio-derived fuels in place of petrol and diesel.

- Agriculture: In the agriculture sector, Sri Trang Rubber and Plantation is earning carbon credits by reducing emissions in its operations in Chiang Mai, Phayao, Lampang, Phrae, and Sukhothai13/. Other carbon reduction schemes in the sector include improved farming practices, better use of fertilizers, and the cultivation of perennial crops.

- Forestry and related areas: Phrae has attracted the most carbon credits for forestry-related projects, though large-scale reforestation projects in Chiang Rai and Nan should also help to sequester significant quantities of carbon. These types of activities are being promoted more heavily now since they offer a way to both draw down a considerable volume of greenhouse gases and generate income for project developers and local communities when these work together.

The current state of the Thai carbon market

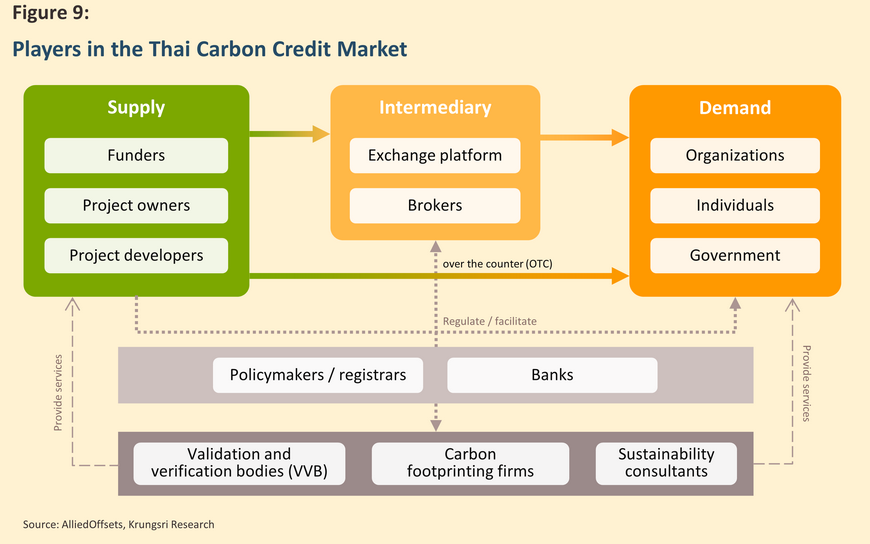

Once an application has been approved and the carbon reductions associated with a project have been verified by the TGO, the resulting carbon credits can be traded. At present this can be done in two ways. (i) Credits can be sold ‘over the counter’ (OTC), meaning that buyers and sellers agree terms of sale directly without the involvement of any intermediaries. (ii) Credits can also be traded on the FTIX platform15/, a carbon exchange that functions much like a stock exchange does, matching buyers and sellers who wish to trade at an agreed price.

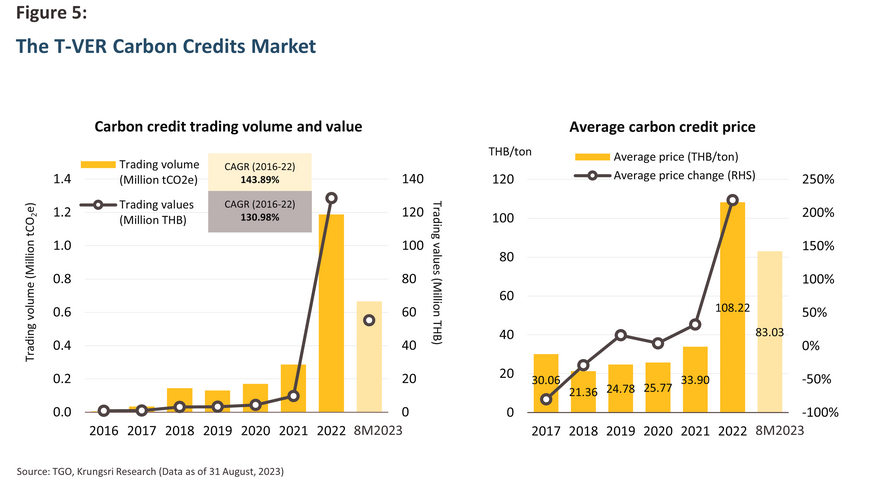

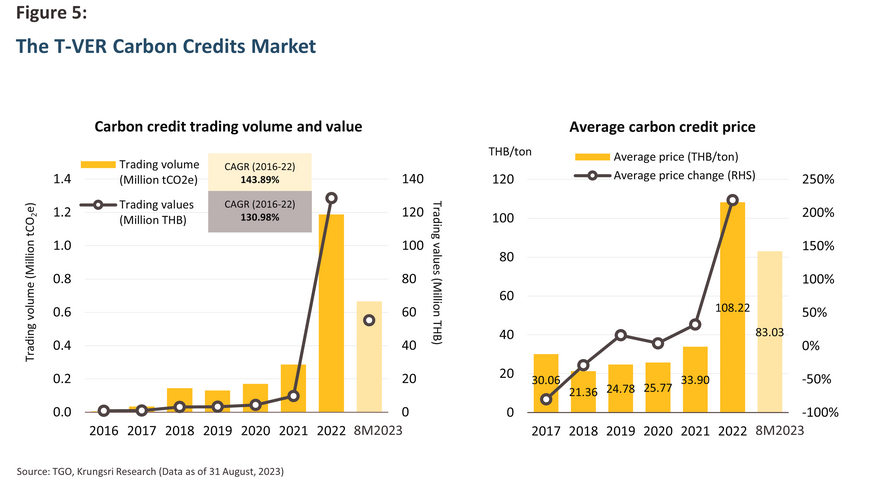

Overall, the Thai market for carbon credits remains somewhat underdeveloped, and although as of 2022, 4.7 MtCO2e of carbon credits had been validated and verified by the TGO, only around a quarter of this, or 1.2 MtCO2e, had been traded. Nevertheless, after sluggishness in its initial stages of development, trading in T-VER carbon credits has gained pace through the last few years, and over 2016-2022, this grew by an average of 144% by volume and 131% by value. Growth was especially strong in 2022, when trades hit a historic high on both counts as public awareness of the importance of addressing environmental issues rose to new highs. The latter was driven by reporting of the COP26 meeting16/, the announcement by the Thai government of more challenging sustainability targets, and the increasing tendency of businesses to set their own targets for carbon neutrality and net zero emissions. This then fed stronger demand for carbon credits to offset emissions, while prices for these remained fairly low17/.

Despite these trends to growth, by both volume and value, the trade in carbon credits weakened over the first 8 months of the year relative to a year earlier, though this was still more than double the total for all of 2021, indicating that trade volume is starting to track normal supply and demand. Carbon trading volumes are also determined on the demand side by an organization’s carbon footprint and what will be needed to offset this, as assessed by the TGO. Organizations will be informed of the results of the latter in November, and so demand for carbon credits will rise at the close of 2023.

In 2022, domestic prices for carbon credits averaged THB 108/tCO2e, but although this was up more than three-fold from 2021, Thai prices are still far below global averages. The World Bank’s State and Trends in Carbon Pricing 2023 indicates that average prices for carbon credits originating from nature or technology-based sequestration ran in the range of THB 500-700/tCO2e, while those from alternative energy projects came in at THB 170-350/tCO2e. Compared to compulsory carbon credit markets, the gap was even wider. For example, in the EU, where the EU ETS is enforced, prices for emissions rights are around THB 3,500/tCO2e. One reason why Thai prices are so low is that the domestic market is still voluntary, unlike in many countries, where carbon pricing and credit systems are mandatory.

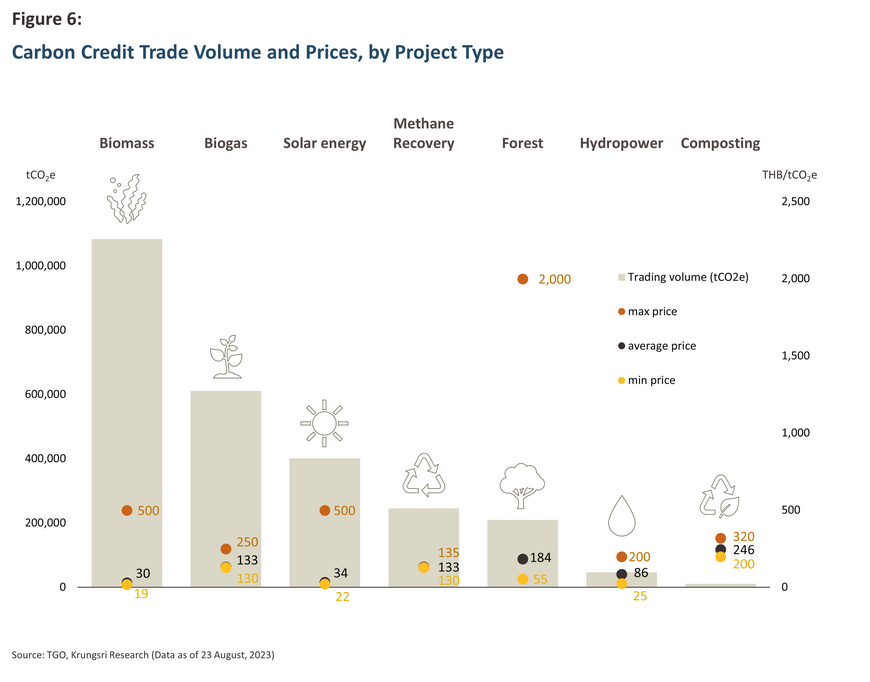

Prices may differ significantly depending on the type of project generating the carbon credits, with the highest domestic prices going for forestry projects (in 2022, prices ran as high as THB 2,000/tCO2e). This is because although these may carry high investment overheads, they promise to generate emissions reductions over an extended period of time, and given these advantages, global demand for forestry credits is strengthening. However, because of the different timescales over which credits are generated, the Thai trade in forestry credits remains somewhat weak compared to those from renewables projects (e.g., for biomass, biogas, and solar), and so over January to August 2023, while trade in forestry-derived carbon credits totaled 208,030 tCO2e, this was behind the total for biomass projects. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that whereas forestry carbon credits sold for an average of THB 173/tCO2e, for biomass projects, the average price was just THB 36/tCO2e, though in 2023, the highest priced carbon credits came from schemes centered on composting and the generation of power from wind and biogas, for which prices were all above THB 200/tCO2e.

In addition to the type of project, other factors affecting the price of carbon credits include: (i) the issuing authority, since prices will vary depending on the scrupulousness with which standards are enforced; (ii) the age of the credits, with more recently verified credits typically being in more demand and so these command higher prices; and (iii) the overall benefits accruing from the project, for example, establishing a green space and reducing pollution will meet demand differently for different buyers18/.

The question then arises, who is buying Thai carbon credits? Data from the TGO on carbon offset certificates shows that buyers are both organizations or individuals, who buy credits to offset emissions from four classes of activities: those occurring at the organizational level, those being generated by the provision of goods and services, those being generated from meetings and events, and those attributable to individuals19/. Overall, private- and public-sector entities are the largest participants in the market, with 164 organizations having bought carbon offsets totaling 1.2 MtCO2e since 2013, or an average of 7,582 tCO2e of offsets each.

The biggest purchasers of carbon credits are operations in the manufacturing, banking and finance, transportation, and real estate industries (Figure 7). Companies buying credits in large quantities and then regularly renewing these purchases as they expire include Kasikornbank, Bangkok Bank, the Bank of Thailand, and BTS Group. In the manufacturing sector, the most important buyers are Mitr Phol Group and Lion Corporation (manufacturers of consumer products), while there are also many buyers in the transport industry, such as BTS Group, Precious Shipping, and Bangkok Aviation Fuel.

Another area that is generating demand for carbon credits is, perhaps surprisingly, the need to offset emissions from events, and in fact, demand from this segment is second only to demand for offsets against organizational-level emissions. Several recent events have led to large-scale purchases, most notably Wave BCG’s Mobile Expo, PTT Exploration and Production’s International Petroleum Technology Conference 2023, and the 2023 Kasetfair, for which 1,995 tCO2e of offsets were purchased. In the area of product offsets, the most important purchases have been for CP’s chemical-free eggs and for Scratch First’s marketing communications and materials. However, demand for credits for offsets against products and for individual use is relatively low. For the latter, purchases of carbon credits came to an average of just 16 tCO2e per person, which in this case were for the ‘Carbon-neutral Thais’ program that drew in participants from universities, the energy sector, and the TGO itself.

Opportunities and threats facing the Thai carbon credit market

Factors promoting growth in the carbon credit market

1) Setting sub-national and national sustainability targets

Global recognition of the importance of addressing our ecological problems has recently taken large steps forward, and 151 out of 198 nations worldwide have now set targets for reaching net zero and carbon neutrality20/. Below the level of nation states, organizations are also moving forward with the setting of ambitious targets, and at present, 157 states or provinces, 257 cities, and 968 corporations have set their own targets for sustainability. This has given a major spur to growth in carbon credit markets, and as organizations look to meet nationally agreed targets, growth in demand for offsets will continue to strengthen. Beyond this, the internationalization of the trade in carbon credits will also mean that overseas demand will spread to markets in other countries, and so those with greater spending power will have the opportunity to buy or transfer carbon credits from Thailand.

Thailand itself has been no laggard with regard to laying out a sustainability roadmap, and the country has set targets for reaching carbon neutrality and net zero in respectively 2050 and 2065. To reach these targets, it will be necessary to extend forested areas to cover over more than half of Thailand’s landmass and to do this by 2037 if the drawdown of greenhouse gases is to be swift enough to meet the net zero goals. Against this backdrop, carbon credits that offer the possibility of combining emissions reductions with reforestation projects will clearly have a major role to play at the national level.

Concerns about sustainability are spreading and so in addition to national commitments, many organizations are making their own plans for reaching carbon neutrality, which in many cases have more ambitious timeframes. Many of these players are also joining together to push forward with the accelerated development of the domestic market for carbon credits. Examples of these include the Carbon Neutral Network, which has over 500 members, and the Carbon Markets Club, which has more than 300 organizational and individual members.

2) Progress developing green technology

Development of low-carbon technology is making significant strides forward, and this is helping to sustain greater growth in carbon credit markets. This includes advances in the technology underpinning electronic vehicles and batteries, progress on which has jumped forward on a combination of much greater capacity and lower costs, and this has then made it much easier for organizations to switch to the use of EVs. Likewise, improved efficiency, the lower cost of inputs, the introduction of measures to promote greater usage, and rising economies of scale21/ have combined to reduce the overall cost of renewables and in turn, this is making it easier to generate carbon credits from renewables projects. In addition, carbon capture and storage projects also have significant potential as a source of carbon credits. For example, PTT Exploration and Production hopes to begin commercial use of CCS by 202622/.

Beyond this, a range of technologies are being used to develop the carbon credit ecosystem, foremost among these being platforms to measure, validate and verify carbon emissions, which then helps organizations calculate their carbon footprint and the volume of credits that they need to buy to offset this. Platforms that facilitate carbon trading that are similar to stock trading apps are also coming to market, and these will then facilitate the trade in carbon credits. It is also possible that Thai blockchain-based carbon trading platforms will also be developed23/.

3) Growth in the supply and demand of carbon credits

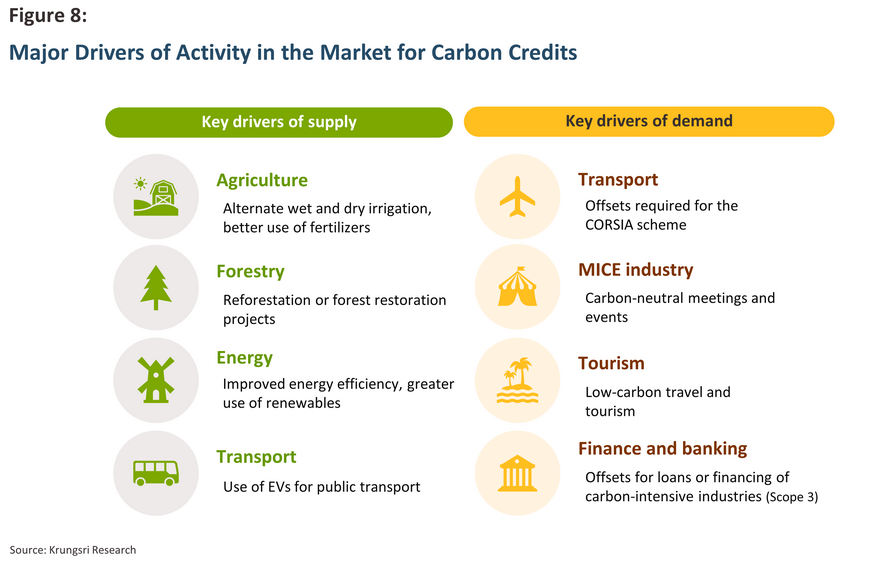

Issues related to the environment and sustainability have become strategic factors that businesses can no longer afford to overlook. This rising importance is reflected in the rapid increase in the value of carbon credits generated and traded in Thailand, and looking forward, activity on both the supply and demand sides of the market for carbon credits will intensify. The major players that will be responsible for this are described below.

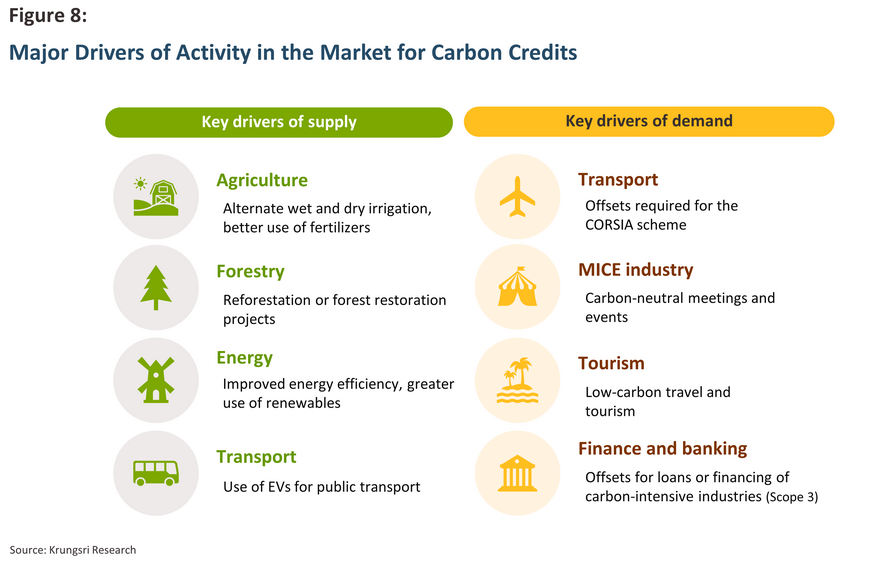

Key drivers of the supply of carbon credits

Agriculture: Changes to farming methods have the potential to substantially cut greenhouse gas emissions and so to generate additional carbon credits. In particular, the flooding of rice fields typically practiced by Thai rice farmers leads to the anaerobic decomposition of organic materials and with this, the release of significant amounts of methane. To help address these problems, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives has joined with the main German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) to promote a project to improve farming efficiencies and cut the release of greenhouse gases. The Thai Rice NAMA (Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action) thus aims to help implement low-emissions rice growing techniques through 4 actions: (i) laser land leveling; (ii) alternative wetting and drying of rice fields; (iii) site-specific nutrient management; and (iv) better straw/stubble management that avoids the need for burning. Using these methods, it is possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 30% relative to standard practices24/, and over 2018-2021, this project is estimated to have generated 305,000 tCO2e of greenhouse gas reductions. These reductions can then be used to generate carbon credits, and so for example, farmers in Suphanburi have been able to generate an additional THB 800 per rai per year (THB 5,000 per hectare per year)25/. The scope of the project has been expanded to include other provinces and so planting low-emission rice is now likely to become more widespread, and an important lesson to draw from the success of this is the role that farmers will have as future sources of carbon credits.

Forestry: Forests clearly have a very important role to play in sequestering atmospheric carbon, and so as part of the plans for reaching carbon neutrality and net zero, the government has set the goal of extending forest coverage to 55% of Thailand by 2037, up from 32% in 201826/. This would then require developing another 27 million rai (4.32 million hectares) of natural forest and agro-forestry stands27/, but fortunately, the supply of carbon credits from forestry projects is increasing and because these have a high potential to draw down carbon dioxide, these are regarded as high-quality credits and so command a correspondingly high price. In addition to sequestering greenhouse gases, forestry projects also provide additional benefits such as creating natural environments, boosting biodiversity, and generating additional income for local communities. Reforestry and forestry conservation projects are thus a favorite among organizations looking to offset their environmental impacts, and it is highly likely that forestry-based carbon credits will take on a more important role within carbon markets in the future. Indeed, there are already 49 forestry projects registered under T-VER and these are estimated to absorb 361,895 tCO2e per year, while over just January to August 2023, newly registered projects will lead to annual emissions reductions of 14,254 tCO2e, a figure that is greater than the 12,149 tCO2e in savings from new registrations for all of 2022. The outlook for forestry-based carbon credits thus remains strongly positive.

Energy: Although the energy sector is the largest source of greenhouse gases, this also means that if operators improve energy efficiency and step up their investments in alternative fuels, they have significant potential to contribute to emissions reductions and to become a major source of carbon credits. Examples of this include Gulf Energy Development’s combined cycle natural gas-fired power plant, which is forecast to generate annual emissions reductions of 2.9 MtCO2e, and the cogeneration plants operated by Top SPP (part of Thaioil) and Global Power Synergy (part of PTT), both of which are also producing large quantities of carbon credits. The renewables segment is naturally also a significant source of credits, with the most important of these being biomass plants operated by Mitr Phol, followed by wind and solar plants run by Energy Absolute (EA). As this survey shows, most carbon credits are coming from large private-sector power suppliers, and these will continue to play a role as major domestic sources of carbon credits as they attempt to reduce their own emissions.

Transport: Like the energy sector, transportation is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions but again, this means that the industry also has significant potential as a source of carbon credits. Over 90% of emissions in the industry come from land transport and so any reductions in the energy used in this area will have a large influence on overall emissions. Changes have thus included the transition from ICE-powered buses to electric buses, and so in 2022, Thai Smile Bus Company (part of the EA group) began operating e-buses (buses entirely powered by electricity). Financial assistance for this change came from the Swiss KliK Foundation, which in return benefited from the carbon credits generated from the use of these vehicles. It is estimated that over 2021-2030, the project will result in the generation of carbon credits equivalent to at least 500,000 tCO

2e

28/.

The transition to a greater reliance on the use of EVs for public transport services will also create new opportunities for carbon credit creation. Examples of this can be seen in the use of EV tuk-tuks by ride-hailing company MuvMi that operate in central Bangkok, and in the increasing deployment of e-buses by the private sector, while alongside this, the Bangkok Mass Transit Authority, a state-owned enterprise, plans to have 7,000 electric buses on the road by 2024

29/. Alongside this, companies large and small will also be able to reduce their own emissions by switching to the use of EVs within their organization. These changes will be reinforced at the national and industrial level by government support for EVs, in particular by its 30@30 policy, under which the authorities have set a target of 30% of all vehicles coming off Thai assembly lines being zero emission vehicles (ZEVs) by 2030. Overall, the transport industry will therefore remain a valuable source of carbon credits.

In addition to the above, better waste management also has potential as an increasingly important source of carbon credits since this is an area that is open to all organizations, and prices tend to be strong. For example, prices for credits from composting leaves, cuttings and branches have averaged THB 260/tCO2e in 2023, while improved management of wet waste by local authorities nationwide is estimated to have cut emissions by 492,212 tCO2e per year.

Key drivers of demand for carbon credits

Transport: In addition to being an important source of carbon credits, the transport industry will also be a major consumer of these since many activities in the industry are very carbon intensive and at least at present, it is difficult to replace these with low-carbon alternatives. This is particularly so in the aviation industry, and therefore as of 2016, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) began to roll out its Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), which is itself part of the industry’s move to net zero. This requires that all 192 member states of the ICAO (including Thailand) enforce measures to tackle emissions, and when these cannot be reduced by the application of new technology, changes to industry processes, or the use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), they will need to be offset by credits purchased in carbon markets. As a result, the introduction of the CORSIA scheme will boost demand for carbon credits by 270 MtCO2e during its voluntary phase (2024-2026) and by 2,300 MtCO2e when enforcement becomes mandatory (2027-2035)30/.

Although offsets used under the CORSIA scheme must meet high standards of verification, for example the Verra’s VCS standards31/, demand for these is high. For example, at an auction organized by the Regional Voluntary Carbon Market Company (RVCMC) in June 2023, a total of 2.2 MtCO2e of carbon credits that passed CORSIA quality checks were disposed of. This was the most ever sold at auction, underlining the strong and growing potential of the market for high-quality credits.

Beyond this, demand for carbon credits is also coming from the Thai rail system. Efforts by the BTS Group to offset emissions have been especially noticeable, and having made purchases of credits of at least 70,000 tCO2e of offsets annually since 2021, BTS has been certified as the world’s first carbon-neutral rail company. Demand is also picking up elsewhere in the road transport system, with Grab now inviting passengers to donate towards the purchase of carbon credits and tree planting schemes33/. The market will thus benefit from growing demand from consumers using transport services.

The MICE (meetings, incentive travel, conventions, exhibitions) industry: The MICE industry covers travel related to meetings, incentive travel, international conventions, exhibitions, festivals, concerts, and sporting events, but as both organizers and consumers become more interested in decarbonizing, demand for credits from the MICE industry is rising. Typically, emissions from events come from direct sources relating to, for example, food preparation (Scope 1) and electricity use (Scope 2), and from indirect sources, for example, travel and waste (Scope 3)34/. Given this, the carbon footprint of an event can be reduced by using more environmentally friendly and less carbon intensive materials and equipment, by better waste management, or by offsetting emissions through the purchase of carbon credits. The strength of demand for offsets for events has in fact been so strong that this has been the second most important segment of the market, after only offsets to use at the organizational level.

The importance of environmentally friendly event organization is expected to increase in the future, and international artists have already begun putting on low-carbon concerts. For example, Coldplay have performed to audiences at events powered entirely by renewables and where recycling was widespread, while Billie Eilish has worked hard to reduce consumption of bottled water35/. In Thailand, support for this segment has come from government agencies including the TGO and the Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau (TCEB), which have provided financial assistance for consultancy and verification of carbon offsets, and in the future, demand for carbon credits from the MICE industry will be sure to strengthen further.

Tourism: The travel and tourism industry is in the process of decarbonizing and transitioning to a new type of low-carbon tourism, and through its ‘adjust-reduce-compensate’ policy, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) is one of the organizations pushing forward with this. Under this policy, the TAT is encouraging the industry to move towards a new model of low-impact, environmentally friendly tourism that uses carbon credits to offset any negative impacts when these cannot be avoided, and evidence of the success of this is seen in tourism in local communities, farm-stays, and smart farms36/.

Hotels and tourist sites worldwide are increasingly appealing to the green tourist segment by embracing issues around sustainability, and the need to demonstrate external verification of the organization’s goals and its progress towards meeting these is driving additional demand for carbon credits across the industry. In Thailand, this can be seen in widespread purchases of carbon credits by hotels, including the Santiburi Hotel, which has bought 2,726 tCO2e of credits and is the first hotel in the South to be designated carbon neutral by the TGO37/, and Sivatel Bangkok, which has purchased 2,380 tCO2e and which also emphasizes the use of organic food in its restaurant and sustainable practices in its waste management38/.

Banking and finance: Although the banking and finance industry is not a major source of direct emissions, the provision of loans and other types of financing for carbon-intensive activities means that demand for carbon credit offsets for Scope 3 activities is significant. Currently, Thai banks are among the major buyers of credits on the T-VER market39/, and with financial institutions wishing to burnish their green credentials, demand will likely remain strong.

Challenges facing the domestic market for carbon credits

1) The cost and value of accredited projects

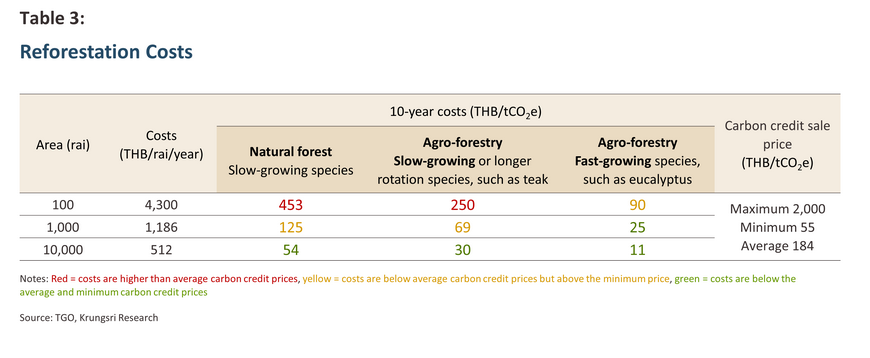

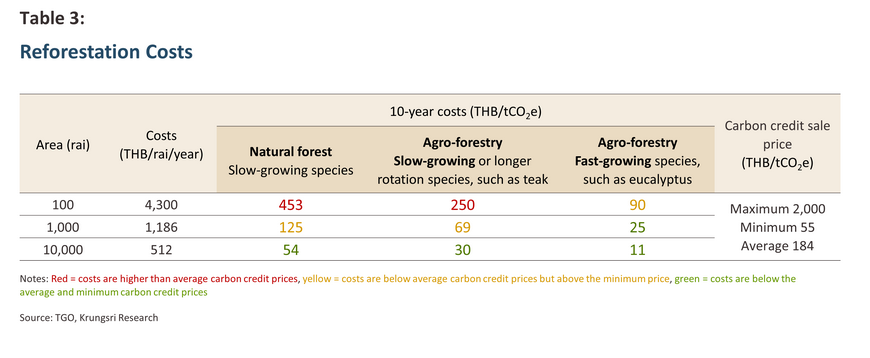

Although the domestic market for carbon credits is on track for growth, this will be limited by the fact that participation remains voluntary and so development of qualifying schemes is restricted to those managed by companies that have a special interest in this area or that have strong finances. The latter is due to the heavy expenses incurred at each stage of the project, including the costs involved in preparing documentation, project implementation, data collection (e.g., for monitoring and recording equipment), sample collection, and fees for validation and verification. These are generally calculated per day worked per person, but the exact rate will depend on a variety of factors, including the size of the project and the complexity of the verification process. In addition, registration fees of THB 5,000-10,000 need to be paid to the TGO for each project, together with a further THB 3,000-10,000 for each request to certify the resulting credits. The viability of individual projects may thus depend on their details. For example, the expenses involved in developing a 10-year reforestation project may vary substantially depending on the type of trees that are planted and their potential to sequester atmospheric carbon. A 100-rai forestry stand planted with fast-growing trees, such as eucalyptus, will have costs over the 10 years of around THB 90/tCO2e, which is comfortably below the current average sale price of carbon credits of THB 184/tCO2e. However, if this same 100-rai plot is planted with different trees, for example, it is used to develop natural forest ecosystems or is planted with slow-growing agro-forestry crops, the costs involved may well be higher than the income generated from the sale of the resulting carbon credits. Thus, for projects involving slower-growing tree species, it is necessary to plant over a wider area, thereby spreading the fixed costs and reducing the per unit overheads (Table 3).

A further problem facing the industry is the high initial cost of some projects. For example, to develop a natural forest ecosystem covering 1,000 rai (160 hectares), the annual costs are forecast to come to THB 209, THB 104 and THB 78 per tCO2e in the 3rd, 6th, and 10th years respectively40/, but setting these costs against the current prices for carbon credits indicates that the project’s break-even point will be far off. High overall costs and long repayment horizons are thus significant hurdles faced by parties looking to develop their own carbon credit projects, particularly for smaller organizations or communities that have limited budgets. That said, some of these problems may be overcome if those wishing to generate carbon credits work together to build economies of scale, such as by planting forested areas over many bordering plots and then sharing the consultancy costs and the fees charged by the validation and verification body.

2) Current state of the carbon credit ecosystem, regulatory framework, and oversight

At present, market prices for Thai carbon credits vary widely for particular project types since these are largely determined by a combination of the quality of the credits and the outcome of negotiations between individual buyers and sellers. At the same time, trading on the FTIX platform remains limited and prices are low, and so on 11 September, 2023, 616,845 tCO2e of credits were traded, just 1% of the total market, and almost all of this was for credits from biomass projects that had an average price of only THB 48/tCO2e. Thus, although prices for carbon credits are trending upwards, a closer look reveals that these are also strongly determined by the quality of the originating project. Moreover, there is currently no regulation of prices, and this remains an issue since if these are too low, suppliers will be disincentivized to generate new credits, but if they are too high, demand will evaporate and potential buyers may instead invest directly in their own carbon-reduction schemes.

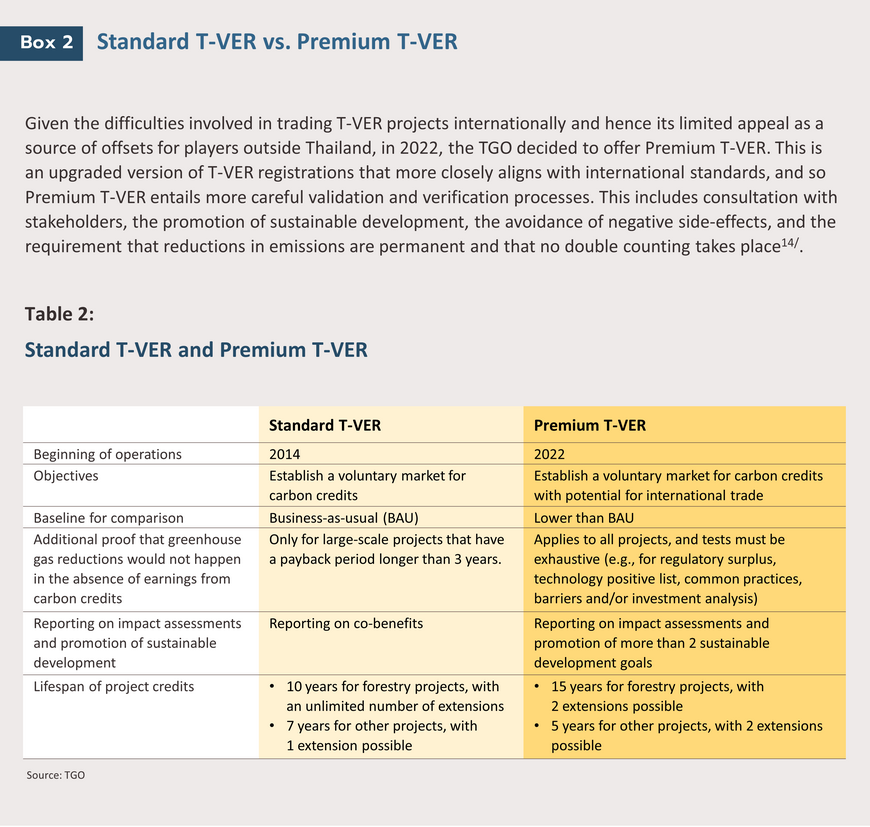

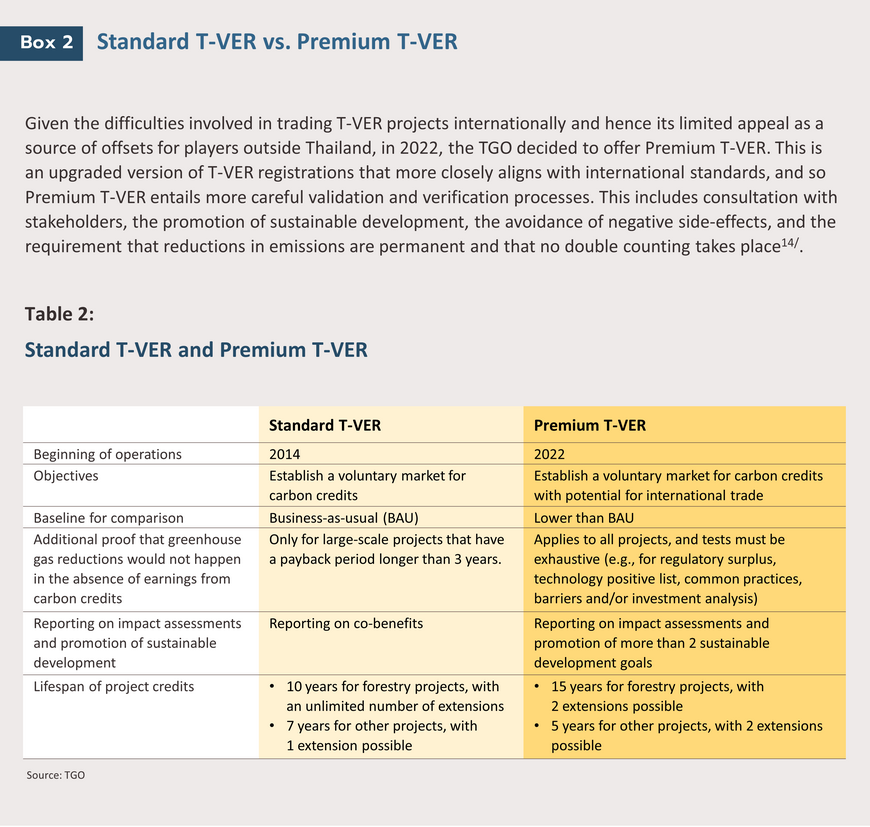

Verification and standards are other areas that remain problematic, and if Thailand wishes to benefit from international demand for carbon credits, this will need to be addressed. At present, T-VER certified credits are not eligible for CORSIA offsets, though in 2022, the TGO worked with Verra to develop the new Premium T-VER standards, and it is hoped these will be acceptable under CORSIA. It remains true, though, that tightening standards will present an increasing problem for inexperienced and less capitalized project developers.

3) Legal enforcement and environmental policies

Because the Thai carbon market is still voluntary, it has yet to see the levels of activity recorded in some markets overseas. In addition, Thailand lacks other types of mandatory pricing mechanisms, such as carbon taxes or an ETS scheme. Since these allow companies to offset carbon fees against carbon credits, they generally help to generate demand for the latter, and so when countries operate carbon credit markets alongside carbon taxes or ETS schemes, the price of carbon set by the latter is generally tied to the prices prevailing in the former.

Thailand also lacks a legal framework to compel stakeholders to make serious efforts to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, and given this broad lack of incentives to accelerate moves to measure, reduce and offset emissions, the Thai carbon credit market remains somewhat underdeveloped. It remains to be seen what the impacts of the passing of the Climate Change Bill will be and to what extent this will stimulate growth in the market for offsets.

Krungsri Research view: Stakeholders across the economy stand to benefit from an expansion in the domestic market for carbon credits

The direction of change in global carbon markets

Looking forward, global markets for carbon credits will grow as countries accelerate the drive to net zero, and research by McKinsey & Company indicates that world demand will reach 1,500-2,000 MtCO2e annually by 2030, a 15-fold increase from 202041/. Demand will be driven by organizations looking to offset their own emissions and to demonstrate to their customers that they take their environmental responsibilities seriously. The consumer side of the market will thus have an important role to play in increasing uptake of credits, and a survey by Boston Consulting Group shows that the majority of consumers are ready to change their brand allegiance to a company that is clear about using offsets to counter-balance its emissions, especially for rail and air transport services42/. Demand will therefore tend to come from large corporations such as Disney, Microsoft and Salesforce.com43/, while in the future, the main source of carbon credits will be projects involving natural sequestration, such as reforestation.

The direction of change in the Thai carbon market

As with international markets, the domestic market for carbon credit has significant growth potential, partly because Thailand has set decarbonization targets that keep pace with those agreed by the major economies. The TGO therefore sees domestic demand for carbon credits rising to around 182-197 MtCO2e per year by 2030, with this coming most obviously from the need to offset emissions made by players in the energy, finance, tourism, and events industries, as well as by the requirements placed on companies by international obligations, such as the CORSIA agreement, though in addition to domestic buyers, demand will also come from international companies looking to meet sustainability goals. In addition, improvements in the technology used to measure emissions and the introduction of rules greening international trade (e.g., the introduction of the EU’s CBAM, which requires that exporters must calculate and report their products’ carbon footprint) will improve the extent to which organizations are aware of their own emissions, and this too will tend to drive increased purchases of carbon credits to use as offsets.

However, with demand expanding rapidly, there is a risk that a gap may open up in the Thai carbon credit market and that buyers may have to contend with a supply shortage, and the current forecast for 2030 supply is that by then, new credits will come to just 6.86 MtCO2e annually. Over the coming period, new projects to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the energy, transport, farming and forestry industries will continue to generate carbon credits, especially in the last of these (forestry will be a source of a large volume of high-quality credits), but the high overheads involved in setting up carbon credit projects is dissuading smaller players from entering the market since at present, less well capitalized projects face elevated per-unit costs against only low average sale prices. In addition, the lack of an appropriate regulatory mechanism to oversee or to set prices and as yet the effective deployment and promotion of a trading platform to efficiently match buyers and sellers may also be discouraging players from establishing new projects to generate carbon credits and then to sell these on the domestic carbon market.

Opportunities for all stakeholders

The various head- and tailwinds described above are clearing the way for stakeholders to work together to develop the Thai carbon credit market. On the supply side, developers of emissions reductions projects will benefit from strengthening domestic and international demand, and although in the past, the reliance on OTC sales and the need for buyers and sellers to negotiate directly made it difficult to conclude sales, the development of carbon trading platforms and the increasingly high profile of market intermediaries, who act as sales channels or who buy credits for resale, is making it considerably easier to match buyers and sellers. As time goes by, it is likely that these intermediaries will take on a more important role as the market grows and they spot holes in the trading system. On the demand side of the equation, purchases of carbon credits will be made by Thai and overseas companies, individuals and government agencies, and this will drive the creation of higher-quality offsets. Beyond this, third party players such as assessing and verifying organizations, companies that measure carbon emissions, and environmental consultants will benefit from increased activity on both sides of the market, and as businesses green, these will take on a more prominent place in the economy.

Beyond immediate market participants, policy makers and standard-setting bodies will also play a major role in shaping the direction in which the market develops and in setting the conditions for its future success. The most important tools for achieving this will be developing the carbon market ecosystem, in particular by ensuring that the market can effectively handle the anticipated increase in sales volume and that verification criteria meet accepted international standards. This will be particularly important given Thailand’s goal of becoming a center of trade in carbon credits within the ASEAN zone. At the same time, the authorities will need to lay out incentives that ensure that carbon credit projects represent a more attractive investment target, and they will also need to push forward with the passing and enforcement of the relevant legislation (e.g., the Climate Change Bill). For its part, the financial industry will also have a role to play across the length of the carbon credit ecosystem.

With all roads leading to a future focused on sustainability, the outlook for the Thai carbon credit market remains positive. High growth potential will continue to attract an expanding supply of market participants, and collaboration between stakeholders to drive forward the development of market infrastructure and to raise standards of oversight and regulation will help to underpin solid and continuous growth.

References

AlliedOffsets. (2023). “Analysis of Voluntary Carbon Market Stakeholders and Intermediaries” Retrieved from https://carbonmarketwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Stakeholder-Analysis-for-the-Voluntary-Carbon-Market.pdf

German Environment Agency. (2018). “Discussion paper: Marginal cost of CER supply and implications of demand sources”. Retrieved from https://newclimate.org/sites/default/files/2018/03/Marginal-cost-of-CER-supply.pdf

Pongvipa Lohsomboon. (2019). “Combating Climate Change with Carbon Pricing”. The National Defence College of Thailand Journal Vol. 61 No. 1 January-April 2019.https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ratthapirak/article/download/189023/132430/554994

Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau. (2022). “How to organize Carbon Neutral Event”. Retrieved from https://www.micecapabilities.com/mice/uploads/attachments/Carbon_Neutral_Events_Guidebook_(TH).pdf

Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization. (2022). “Forest Carbon Credit”. Retrieved from http://www.fio.co.th/fioWebdoc65/p650215-2.pdf

Thanisa Thawitchasri. (2022). “Carbon neutrality and net zero emissions: What’s the difference and why is this important?”. Retrieved from https://www.pier.or.th/blog/2022/0301/

World Bank. (2023). “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023” Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/58f2a409-9bb7-4ee6-899d-be47835c838f

1/ https://thaipublica.org/2023/07/un-chief-says-era-of-global-boiling-has-arrived/

2/ Pongvipa Lohsomboon. (2019). “Combating Climate Change with Carbon Pricing”. The National Defence College of Thailand Journal Vol. 61 No. 1 January-April 2019.

3/ World Bank. (2023). “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023” retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/58f2a409-9bb7-4ee6-899d-be47835c838f

4/ Net zero emissions are said to be reached when the release of greenhouse gases is balanced by reductions, and this cannot be achieved by purchasing carbon offsets. Net zero emissions includes all greenhouse gases, and so in addition to carbon dioxide, this covers methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, etc. This is thus a more challenging target than reaching carbon neutrality (Thanisa Thawitchasri (2022). “How are carbon neutrality and net zero emissions different? And why does it matter?” Retrieved from https://www.pier.or.th/blog/2022/0301/)

5/ https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/about-tver/t-ver.html

6/ https://irecissuer.egat.co.th/statistic

7/ https://caacademy.tgo.or.th/ความแตกต่างระหว่างคาร์/

8/ http://carbonmarket.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=Y29uY2VwdF92ZXRz

9/ https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/about-tver/ask-answer-tver/item/2101-2019-01-03-03-17-38.html

10/ There are 10 external validation and verification bodies registered with the TGO: (i) The Centre of Excellence on Environmental Strategy for GREEN Business, Faculty of Environment, Kasetsart University; (ii) Greenhouse Gas Management and Certification Unit, University of Phayao; (iii) School of Renewable Energy and Smart Grid Technology, Naresuan University; (iv) SGS (Thailand) Limited; (v) Foundation for Industrial Development – Management System Certification Institute (Thailand) (MASCI); (vi) Bureau Veritas Certification (Thailand) Limited; (vii) ECEE Company Limited; (viii) Research Unit for Energy, Economics and Ecological Management, Science and Technology Research Institute, Chiang Mai University; (ix) Greenhouse Gas Verification Unit, The Mae Fah Luang Foundation Under Royal Patronage; and (x) TUV NORD Thailand Ltd. (https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/tver-external-evaluator/vvb-list.html)

11/ As of 2019, total Thai greenhouse gas emissions came to 373 MtCO2e https://climate.onep.go.th/th/topic/database/ghg-inventory/#1629282850097-8b14e636-4ba4) 12/ https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/tver-database-and-statistics/t-ver-registered-project/item/826-rdf-production-from-municipal-solid-waste.html

13/ https://storage-th-xbkk.stockradars.co/psims/News/202308/0254NWS100820232147520629T.pdf

14/ https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/about-premium-t-ver/about-premium-t-ver-project.html

15/ The FTIX platform was jointly developed by the Federation of Thai Industries (FTI), the TGO, and other organizations in the private sector. Trading operations began in the 2023 fiscal year, and in addition to carbon credits, participants can trade in energy generated from renewable sources and Renewable Energy Certificates issued by EGAT (http://carbonmarket.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=c2VtaW5hcg==&action=ZGV0YWls¶m=MTc2).

16/ The 26th Conference of the Parties, or COP26, concluded on 13 November, 2021, with a resolution to address climate change and to push for the phasing out of fossil fuels (https://www.bbc.com/thai/international-59264622).

17/ https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/environment/1086018

18/ https://carboncredits.com/6-key-takeaways-from-world-bank-2023-carbon-pricing-report/

19/ http://thaicarbonlabel.tgo.or.th/index.php?lang=TH&mod=WTI5dVkyVndkRjl2Wm1aelpYUjBhVzVu

20/ https://zerotracker.net/

21/ https://www.thansettakij.com/columnist/443004

22/ https://www.pttep.com/th/Sustainability/Carbon-Capture-And-Storage.aspx

23/ https://www.terrabkk.com/news/201759

24/ The Thai Rice NAMA project received funding from Germany, the UK, Denmark, and the EU. In its initial phase, the project ran for 5 years (2018-2023) in the 6 pilot provinces of Chainat, Pathum Thani, Singburi, Suphanburi, Phra Nakhon Sri Ayutthaya, and Ang Thong. The project was then extended until July 2024 and expanded to include Kamphaeng Phet, Lopburi, and Nakhon Ratchasima. The government now plans to extend this as the Thai Rice ECF project, which will cover 21 provinces (https://www.thansettakij.com/sustainable/zero-carbon/574434).

25/ https://www.salika.co/2023/08/06/low-carben-rice-innovation/

26/ https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1518826/new-laws-chased-to-boost-afforestation

27/ https://www.sac.or.th/portal/th/article/detail/438

28/ Swiss participation in Thailand’s e-bus project was carried out via the KliK Foundation, which partnered with the EA Group to provide funding for the buses in return for the transfer of carbon credits resulting from the scheme’s implementation. This agreement was signed on 24 June 2022, and falls within the scope of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which aims to promote international cooperation in the shared goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions (https://brandinside.asia/e-bus-programme-from-switzerland).

29/ https://www.komchadluek.net/quality-life/well-being/547519

30/ TGO and Marginal cost of CER supply and implications of demand sources, DEHSt (2018)https://newclimate.org/sites/default/files/2018/03/Marginal-cost-of-CER-supply.pdf

31/ https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Pages/default.aspx

32/ https://www.thairath.co.th/news/sustainable/2702350

33/ https://www.springnews.co.th/digital-tech/technology/832607

34/ https://www.micecapabilities.com/mice/uploads/attachments/Carbon_Neutral_Events_Guidebook_(TH).pdf

35/ https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/environment/1073860

36/ https://www.tatnewsthai.org/news_detail.php?newsID=5225

37/ https://www.singhaestate.co.th/th/เอส-บล็อก/santiburi-koh-samui

38/ https://readthecloud.co/sivatel-bangkok/

39/ Kasikornbank, Bangkok Bank, and Kiatnakin Phatra Bank are regular buyers of carbon credits on the T-VER market, though Kasikornbank is the most important of these.

40/ http://www.fio.co.th/fioWebdoc65/p650215-2.pdf

41/ https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/a-blueprint-for-scaling-voluntary-carbon-markets-to-meet-the-climate-challenge

42/ https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/next-frontier-in-consumer-carbon-footprint-credits

43/ https://capitalmonitor.ai/sector/tech/who-buys-carbon-offsets-and-why/