Executive Summary

Despite the heightened uncertainty in global trade and investment caused by trade policies under President Trump’s second term (“Trump 2.0”), Krungsri Research assesses that ASEAN will remain a key global investment destination. This outlook is underpinned by the region’s distinctive structural strengths, most notably its strategic geographic proximity to China, supporting the ongoing supply chain diversification trend.

At the same time, each economy in ASEAN has its own unique strengths that enable them to attract foreign investment and cater to the specific needs of different types of investors. For example, Thailand and Malaysia are well-positioned to appeal to investors prioritizing infrastructure readiness and established manufacturing supply chains, whereas Indonesia is particularly attractive to those prioritizing domestic market potential

In terms of potential industries, nearly all ASEAN countries show strong potential in digital industries and strategic manufacturing, with particularly promising prospects for countries able to leverage their advantages in services and digital capabilities. However, the region’s ability to sustain its long-term investment appeal depends on qualitative improvements. These include greater regulatory transparency, enhanced public sector efficiency, upgraded infrastructure, and workforce skill development. Such factors will be crucial in strengthening competitiveness and ensuring that ASEAN economies can continue to attract investment amid an increasingly uncertain global trade environment

Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has long been a key driver of economic growth in the ASEAN. Despite challenges such as complex regulatory frameworks and inadequate infrastructure in some member countries, ASEAN continues to hold notable appeal for investors, particularly given its strategic geographic location amid the ongoing diversification of supply chains away from China (the “China+1 Strategy”).

However, trade policies under President Trump’s second term (“Trump 2.0”) may raise questions regarding ASEAN’s investment potential and attractiveness. Of particular concern are policies targeting trade rerouting through the imposition of transshipment tariffs, as well as higher import duties, including reciprocal tariffs and sector-specific tariffs.

As a result, ASEAN’s competitiveness in attracting FDI going forward may no longer rest solely on quantitative factors—such as lower production costs and tariff advantages over China, as was the case under Trump’s first administration.

Instead, qualitative factors are taking on greater importance. These include the overall investment climate and ease of doing business, alongside structural fundamentals that underpin long-term economic growth.

Accordingly, this study aims to assess ASEAN’s investment competitiveness across two dimensions. At the macro level, the analysis focuses on each country’s investment attractiveness, considering economic fundamentals, institutional factors, and investment-related policies.

At the micro level, we examine industries with investment potential in each country. The scope of this study covers Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines, while excluding Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Myanmar due to data limitations and the differing levels of economic development compared to the selected countries.

ASEAN’s Strengths as an Attractive Investment Destination

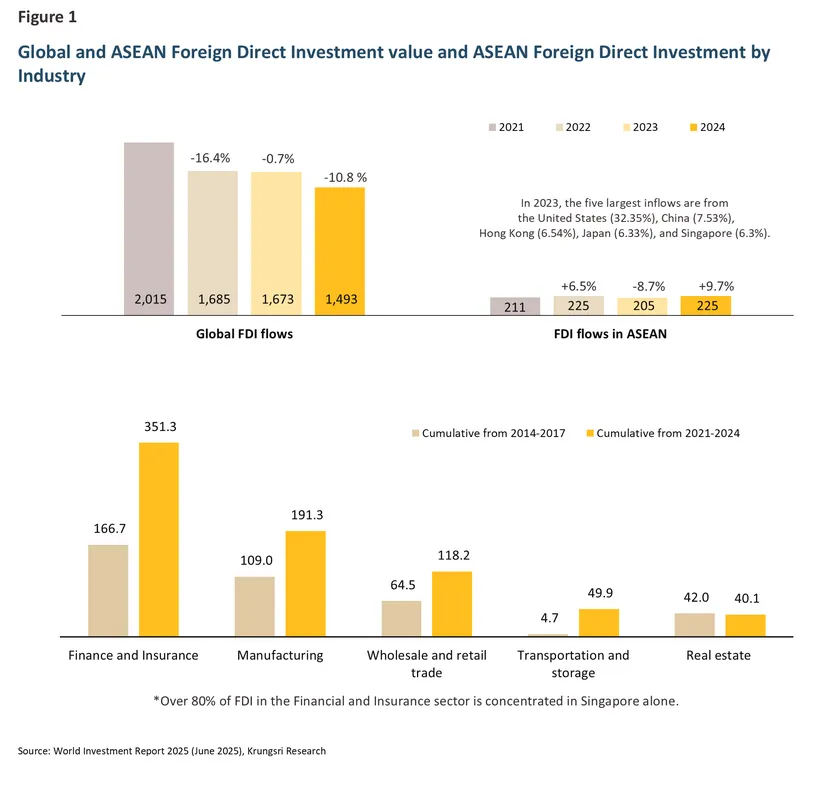

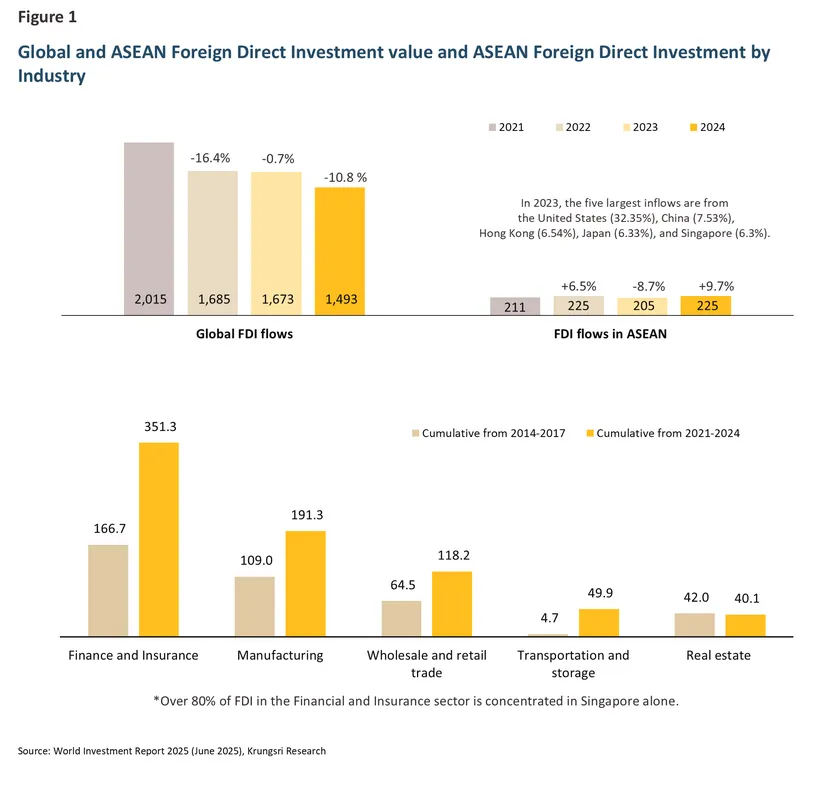

According to UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2025, although global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows slowed in 2024, ASEAN was able to attract an additional 10% increase in inflows (Figure 1). This growth was led by strategic manufacturing industries, such as semiconductors and electric vehicle (EV) components, underscoring both the diversification of production bases by multinational enterprises (MNEs) and ASEAN’s role as a major investment destination This continued momentum is underpinned by several structural strengths beyond cost advantages and lower import tariffs compared with China. The region’s strengths as an investment destination can be summarized as follows:

1/

1. Large Economies Serving as Both Consumer Markets and Key Labor Sources

ASEAN has a population of over 680 million people, with a median age of only 31 years. This not only reflects a vast consumer base with a rapidly expanding middle class, but also provides a sizeable labor force that remains cost-effective and competitive. Moreover, ASEAN continues to record some of the highest rates of economic growth compared with other regions globally.

2. Strategic Geographic Location

Situated close to China—the world’s primary manufacturing hub—and in proximity to Asia’s major consumer markets, ASEAN has become a critical destination for multinational enterprises (MNEs) relocating production bases under the “China+1” strategy.

3. Abundant Natural Resources

The region’s geographical endowment has provided ASEAN with a rich and diverse natural resource base. Indonesia, in particular, possesses critical resources such as nickel, which plays an essential role in the electric vehicle (EV) industry.

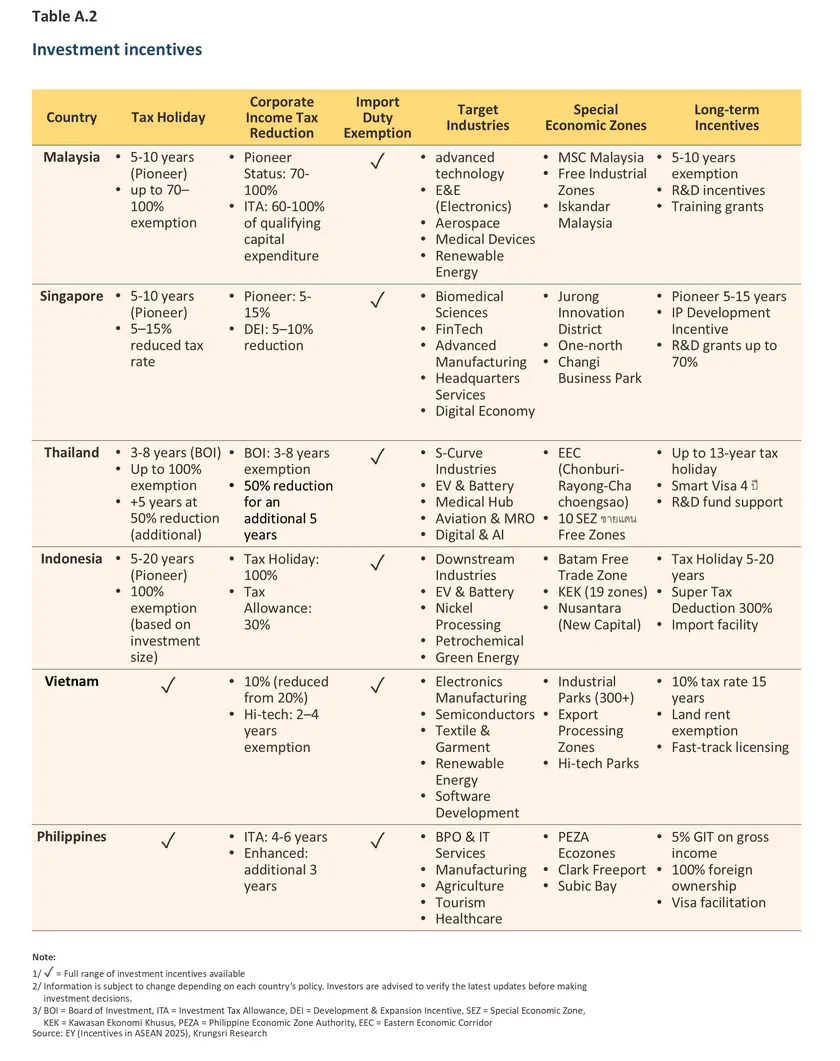

4. Investment-Friendly Government Policies

Nearly all ASEAN member states have accelerated domestic infrastructure investment while simultaneously offering investors tax incentives and facilitation measures aimed at attracting foreign investment, particularly into strategic and priority industries.

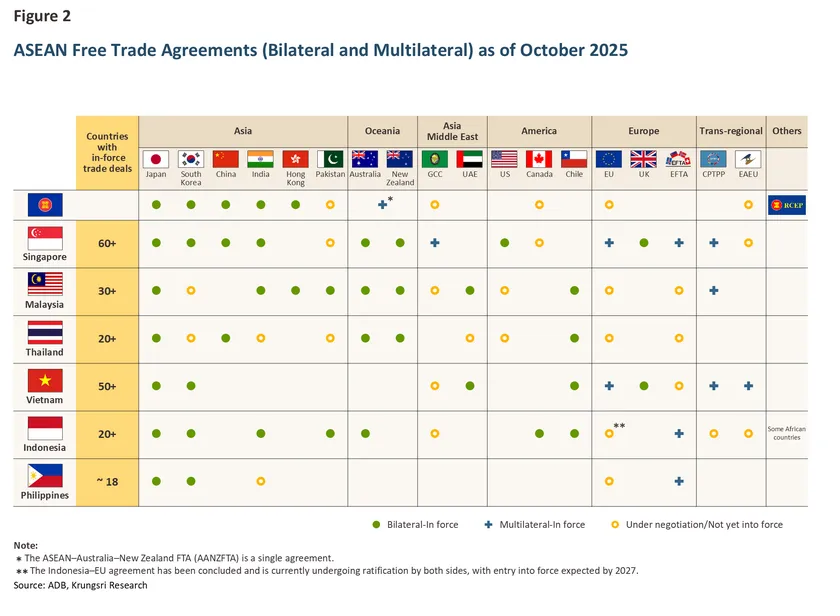

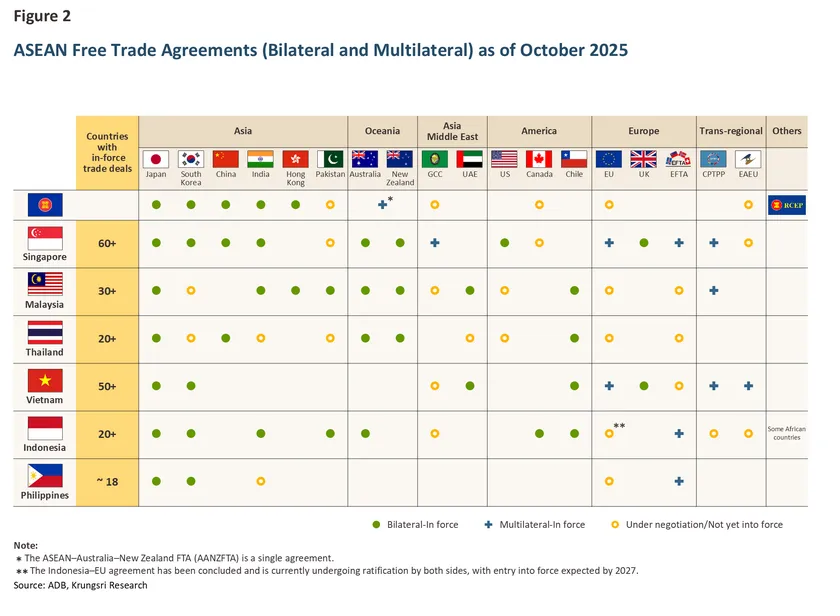

5. Extensive Economic Integration Both Within and Beyond the Region

ASEAN has established a wide range of free trade agreements (FTAs), both bilateral and multilateral, designed to promote seamless trade and investment flows with partners inside and outside the region. These agreements reduce trade barriers, enhance competitiveness, and serve as a key strategy for attracting investment. At present, ASEAN and its member states have concluded numerous trade agreements, with many more currently under negotiation (Figure 2).

In recent years, ASEAN member states have increasingly sought to expand trade agreements with other regions to build broader networks and diversify trade risks—particularly in the context of intensifying trade tensions among major powers. Nevertheless, while several factors continue to support investment in the ASEAN region overall, a country-level analysis reveals that each country has its own unique strengths and challenges, which will be elaborated in the following section.

An Assessment of Investment Attractiveness Across ASEAN Countries

Global competition to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) is undergoing a structural transition—from reliance on cost-based advantages in production toward an emphasis on quality-based competitiveness. This shift is taking place within an increasingly complex trade and investment environment, shaped by the adoption of protectionist policies as well as the implementation of a Global Minimum Tax (GMT) framework.

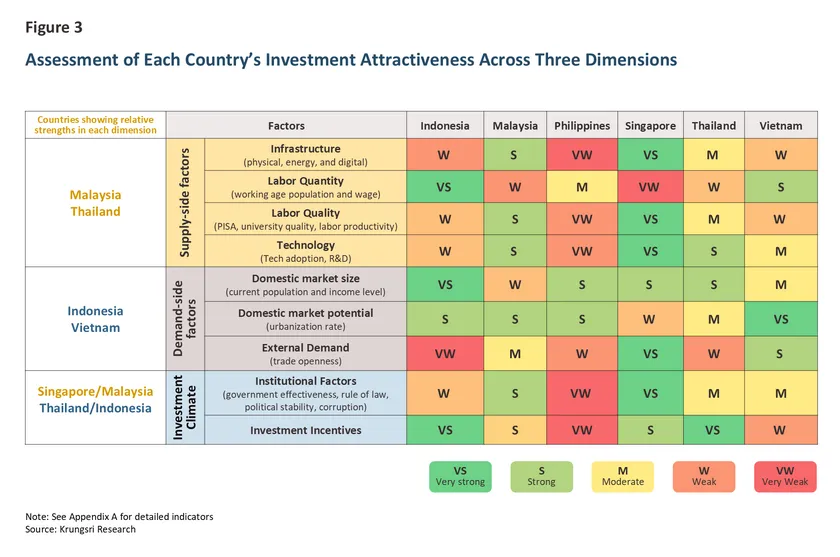

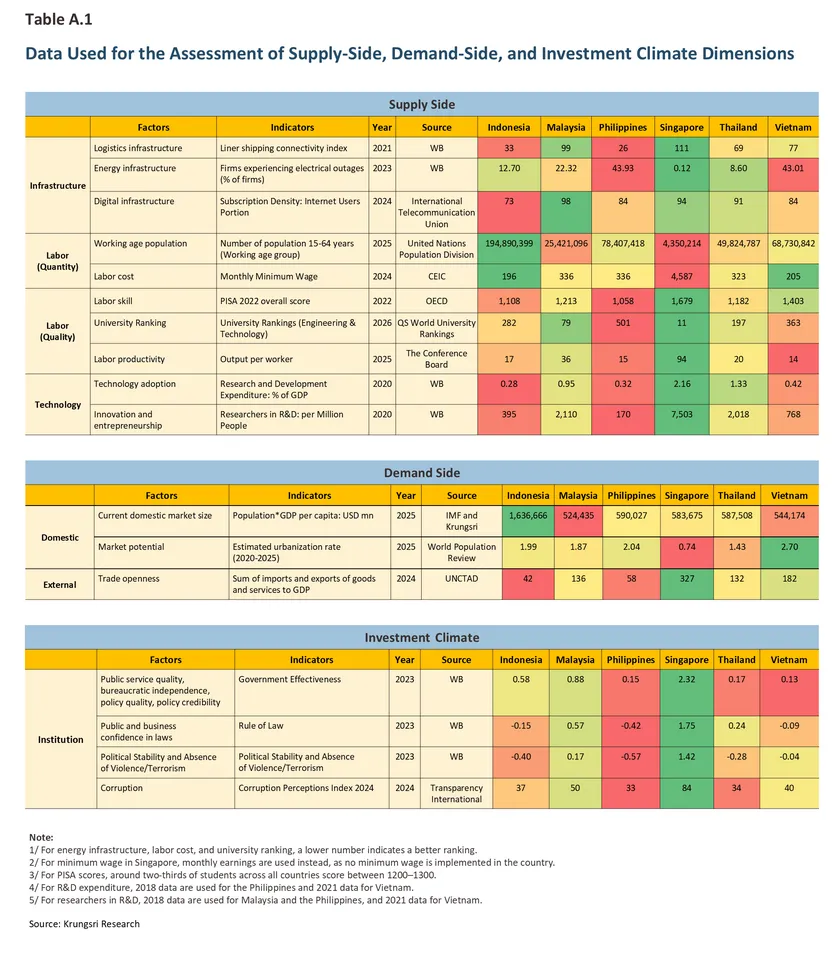

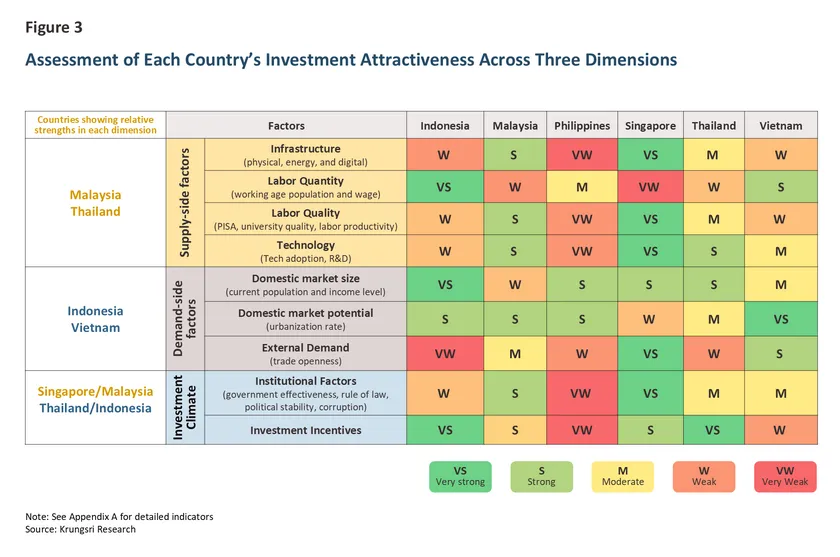

Hence, this section examines the competitiveness of ASEAN countries in attracting investment from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. The analysis is structured around three dimensions: supply-side dimension, demand-side dimension, and the overall investment climate dimension (Figure 3).

The assessment can be summarized as follows:

1. Supply-Side Dimension—Excluding Singapore, which outperforms nearly all components except labor availability (given its high wage levels and smaller working-age population relative to its peers), the supply-side potential of other ASEAN countries can be categorized into three groups:

-

High potential group: Malaysia and Thailand. Both countries demonstrate strong infrastructure readiness for manufacturing and relatively effective technology adoption. Malaysia stands out for its digital infrastructure despite limited labor supply, while Thailand benefits from stable energy-related infrastructure, although labor quality remains at a moderate level.

-

Moderate potential group: Indonesia and Vietnam. Indonesia has the region’s largest labor force but faces persistent constraints in infrastructure quality and technological readiness. Vietnam, while still in need of major infrastructure improvements (especially in energy), benefits from a low-cost and competitive labor force with a still-growing working-age population.

-

Countries requiring further development: The Philippines. Despite its large working-age population share, it lags in nearly all supply-side components.

2. Demand-Side Dimension—This reflects market potential for investment attraction, encompassing both domestic and access to external markets.

-

Domestic demand: Considering market size alone, Indonesia stands out due to its large population. When combined with rapid urbanization (a proxy for future market potential), Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines emerge as the most attractive. By contrast, Singapore and Malaysia may have limited market expansion potential but benefit from high per-capita incomes, translating into stronger purchasing power.

-

Access to external markets: Vietnam and Singapore have a clear advantage due to their high trade openness, while Malaysia and Thailand are also competitive, though to a lesser extent.

3. Investment Climate Dimension—This dimension covers both institutional factors influencing investor confidence and specific investment incentives.

-

Institutional factors: These factors clearly differentiate investment attractiveness across countries. Singapore stands out as the clear regional leader, followed by Malaysia. When these are considered alongside supply- and demand-side factors, Malaysia ranks ahead of Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia, which remain broadly comparable. Thailand’s weakness lies in corruption, Vietnam faces limitations in government efficiency, and Indonesia struggles with rule of law and political stability. The Philippines ranks lowest in almost all institutional-related indicators.

-

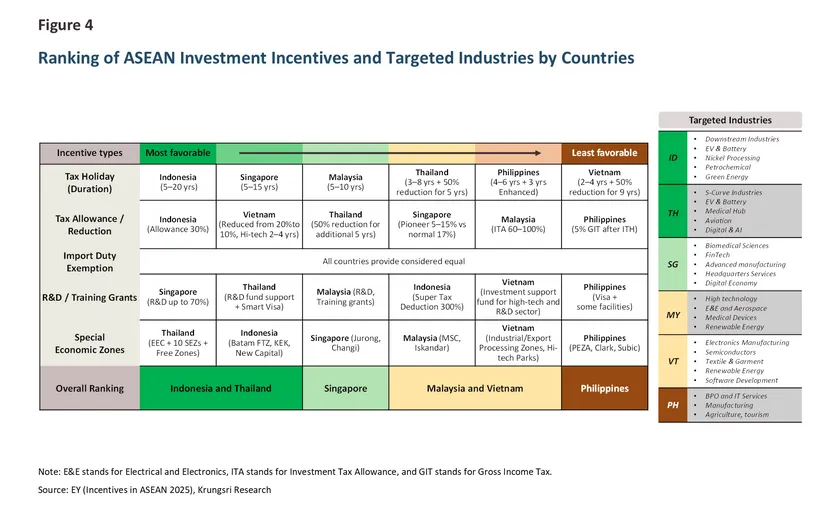

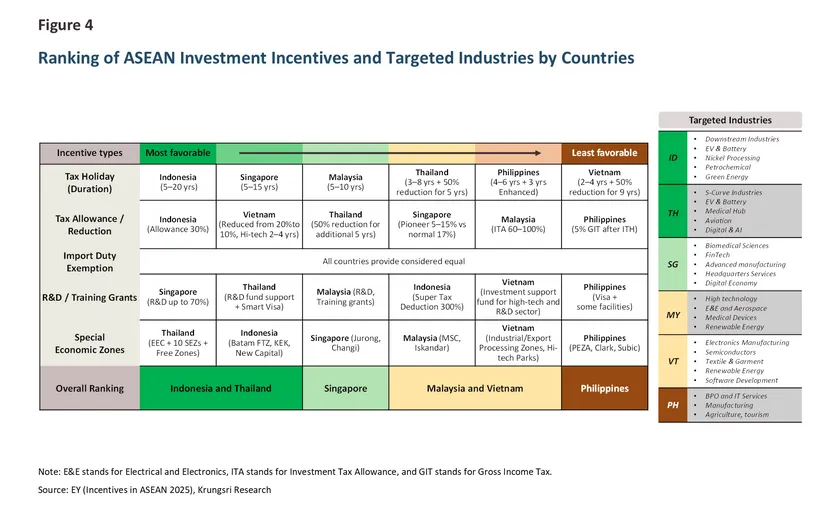

Investment incentives: These remain an important determinant for investors, with countries tailoring incentives toward strategic industries aligned with national development priorities.A comparison of overall investment incentive frameworks (Figure 4) yields the following:

-

Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore provide the highest level of investment incentives in ASEAN. Indonesia is particularly generous with tax incentives, offering the longest tax holidays and greater deductions in corporate tax rates than its peers. Thailand, while less competitive on taxation compared with Indonesia, offers more comprehensive incentives—especially those linked to strategic zones and special economic areas that match targeted industry needs. Singapore, in addition to tax exemptions, emphasizes support for research and development (R&D) and investment in advanced industries.

-

Malaysia and Vietnam, offering shorter tax holidays and fewer tax-related measures, but compensating with a greater range of additional incentives for priority sectors.

-

The Philippines ranks last, with relatively limited tax incentives and a stronger emphasis on attracting investment in digital services and facilitating investment procedures.

In summary, when considering investment attraction potential across the dimensions of supply, demand, and the investment climate, Singapore emerges as the most competitive economy in the region, while Malaysia demonstrates strong potential in both infrastructure and institutional factors. Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia each possess distinct strengths as well as targeted investment incentive schemes; however, all three countries need to accelerate institutional reforms to enhance long-term competitiveness. The Philippines, meanwhile, continues to face persistent constraints in infrastructure, labor quality, and several investment climate indicators.

It is worth noting that this assessment does not assign weights to the relative importance of each factor. Nevertheless, under the current global trade environment characterized by heightened uncertainty, combined with the implementation of a 15% Global Minimum Tax (GMT)2/ that is eroding the effectiveness of tax incentives as a key instrument for attracting foreign direct investment, thus qualitative factors are becoming increasingly decisive in shaping investor decisions.

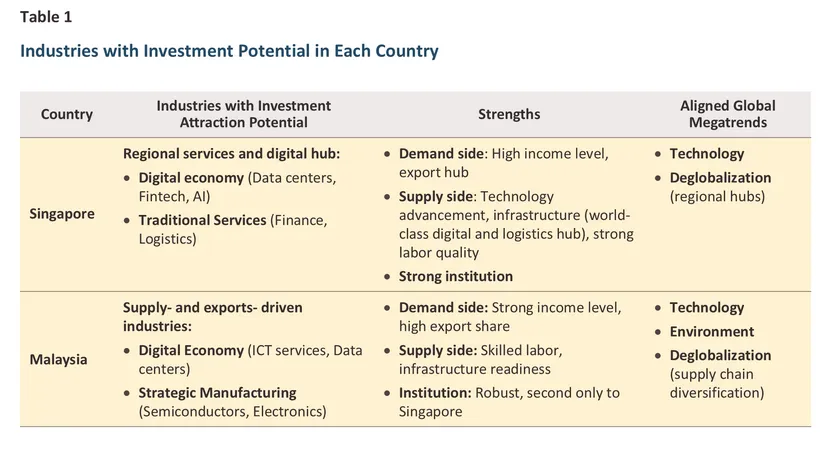

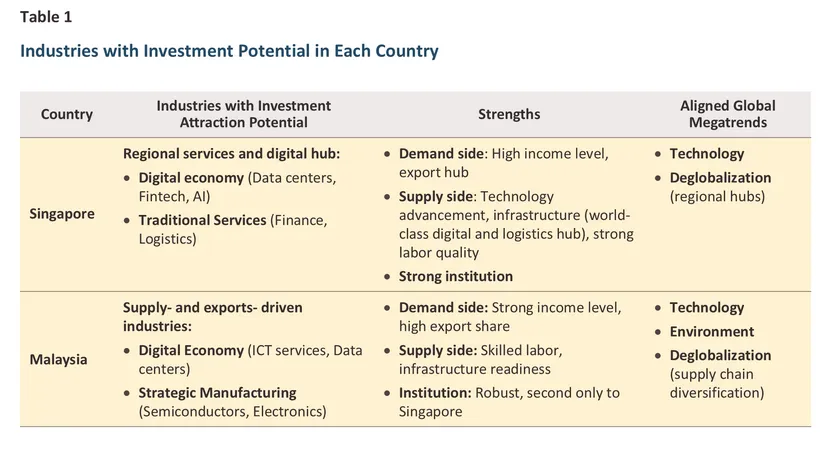

An Assessment of Industries with Investment Potential Across ASEAN Countries

Although global foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2025 may come under pressure from economic uncertainty and shifting trade policies under the context of Trump 2.0, looking beyond short-term volatility, the long-term attractiveness of investment is largely determined by structural factors and Global Megatrends3/. The analysis in Section 2 indicates that ASEAN continues to hold considerable potential to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) in the coming years. Nevertheless, each country possesses distinct competitive advantages, resulting in varying industries with investment potential.

This section draws upon and classifies target industries within the context of developing economies, based on UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2025. Four key groups are identified as follows:

-

Digital Economy Sectors, such as Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Cloud Computing, and Cybersecurity

-

Strategic Manufacturing, such as Semiconductors, Electronics, and Electric Vehicles (EVs)

-

Infrastructure Industries, such as Energy (Fossil Fuels and Renewable Energy), Transport, Telecommunications, and Public Utilities

-

Traditional Manufacturing Sectors and Services, such as Oil and Gas, Mining, Textiles, Food and Beverages, Financial Services, Education, and Healthcare

Accordingly, the industries with investment potential in each country can be classified based on demand-side factors, supply-side factors, institutional conditions, and country’s target industries as analyzed in Section 3, as well as their alignment with global megatrends, as summarized in the Table 1.4/

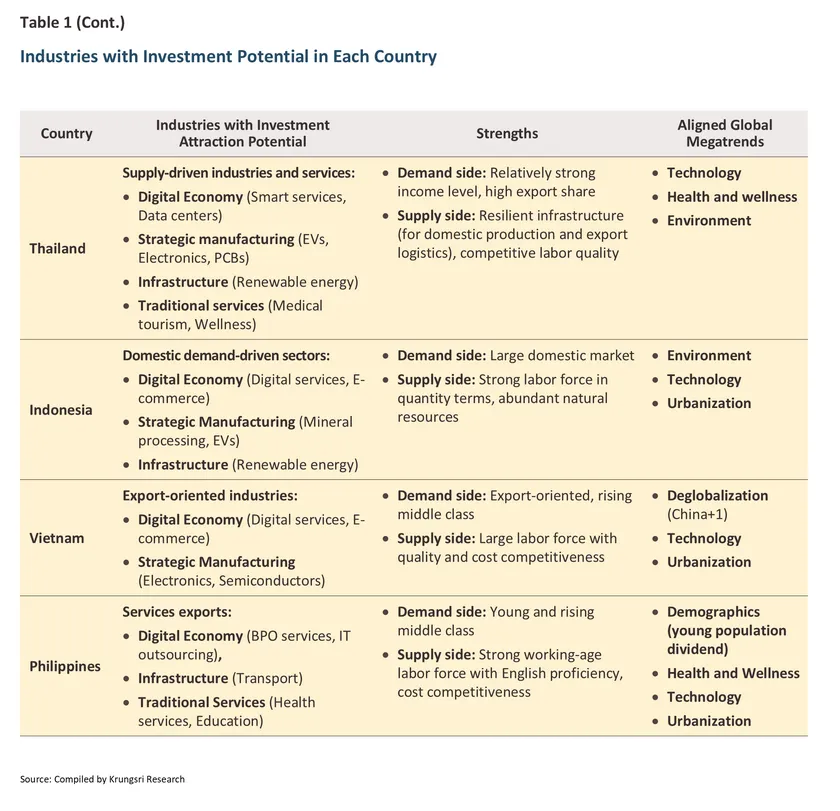

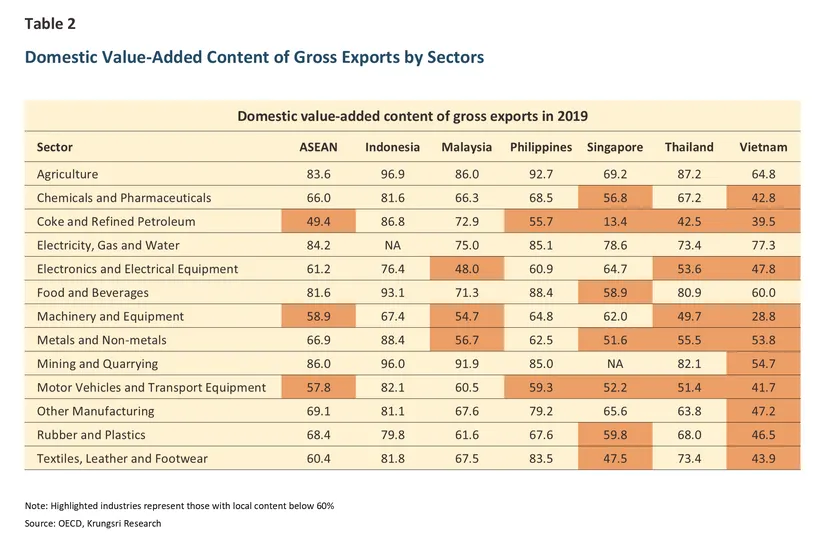

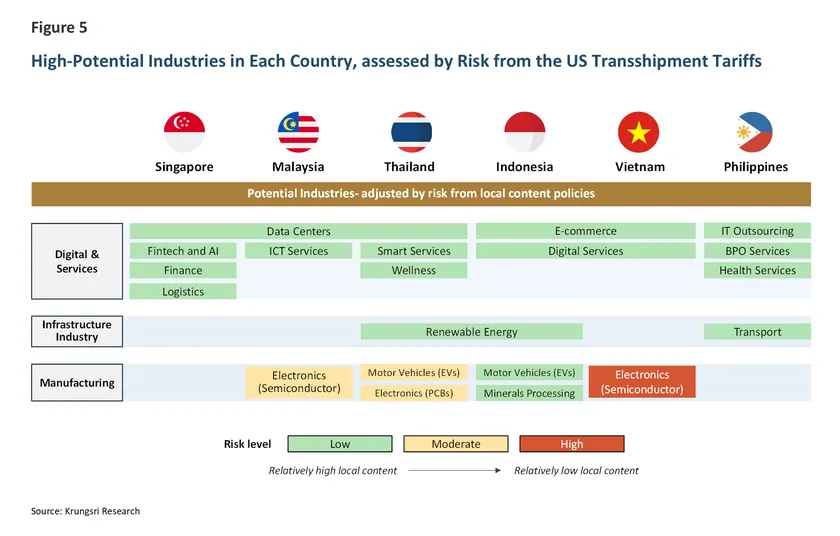

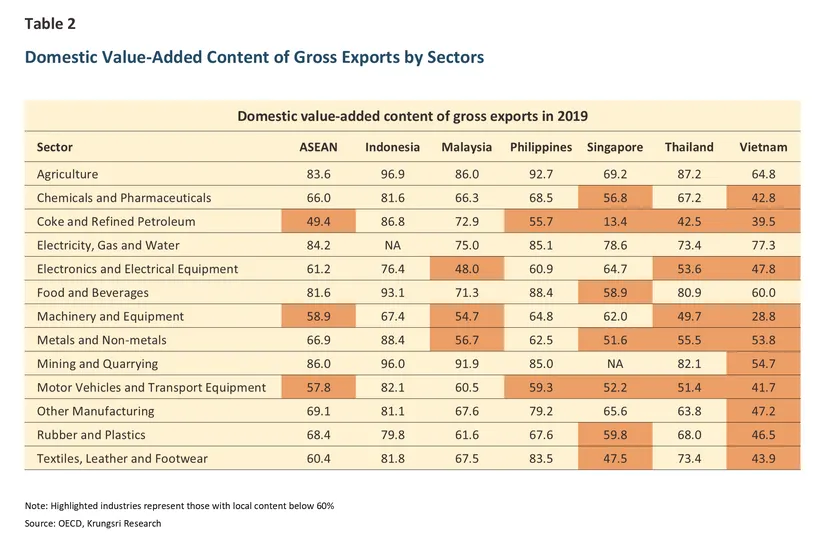

However, the relatively low utilization of local content—the use of domestically sourced raw materials and production inputs—in several ASEAN countries (Table 2) may undermine the region’s investment attractiveness under current U.S. trade policies, which seek to curb the transshipment of Chinese goods through ASEAN by imposing transshipment tariffs. Industries with insufficient local content are particularly exposed to the risk of being subject to such tariffs. Ultimately, the degree of this risk will depend on the specific criteria and threshold for the required minimum local content.

From Table 2, it is evident that the risk of ASEAN’s manufacturing sector being subjected to transshipment tariffs varies across countries, as follows:

-

High-risk countries: Vietnam faces a low proportion of local content in several key industries, including machinery, automotive, and electronics. This reflects a high dependence on imports—particularly from China5/—which could hamper investment in these sectors.

-

Medium-risk countries: Thailand and Malaysia fall into this category. Although Thailand possesses a strong manufacturing base, it must further increase local content in industries such as electric vehicles (EVs), electronics, and machinery to comply with potentially stricter evaluation criteria. Malaysia encounters similar challenges, particularly in electronics and machinery.

-

Low-risk countries: Indonesia and the Philippines. Indonesia benefits from a high degree of local content, especially in resource-based industries such as mining and energy. The Philippines, while generally at low risk, presents a different case: local content is less relevant as a criterion given its economic structure, which relies more heavily on the services sector, with manufacturing still relatively small compared to other ASEAN countries.

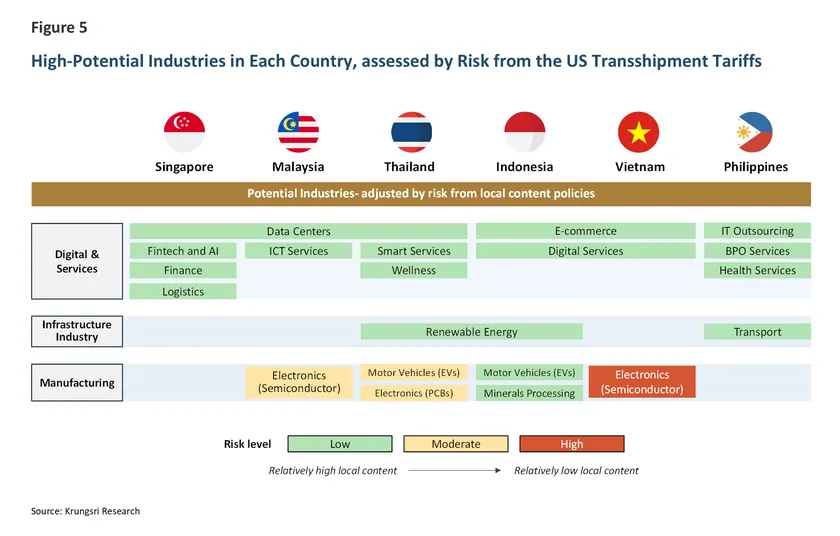

When assessing each country’s potential industries together with their respective levels of local content, the analysis suggests that manufacturing industries are more likely to face risks associated with transshipment tariffs. These risks can be ranked according to the degree of reliance on domestic inputs, as illustrated in Figure 5. Consequently, while certain manufacturing subsectors in ASEAN may remain attractive to foreign direct investment (FDI), in the long term, countries with strengths in services and the digital economy, as well as those with greater capacity to source raw materials and production inputs domestically, will hold greater advantage in attracting investment.

Krungsri Research View

In recent years, ASEAN has emerged as an attractive destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). However, with global trade and investment trends increasingly shaped by uncertainty in policy—particularly under the second Trump administration—questions have arisen regarding the region’s potential to attract foreign investment. This study highlights four key observations:

First, ASEAN remains an appealing investment destination despite heightened global economic and policy uncertainties. These challenges are not unique to ASEAN but are shared across regions. Importantly, ASEAN benefits from a variety of structural strengths, most notably its strategic geographic location in proximity to China. This advantage aligns with the ongoing diversification of global supply chains, ensuring ASEAN’s continued relevance as a prime choice for international investors.

Second, in terms of each country’s investment competitiveness, Singapore stands out as the most competitive, despite its constraints of a small labor force and relatively high costs. Malaysia follows closely, particularly in terms of quality factors, supported by infrastructure comparable to Thailand. Vietnam and Indonesia fall into the medium-potential category, each with distinct strengths, while the Philippines continues to face multiple challenges that may limit its investment attractiveness in the short term.

Third, in terms of industries with strong investment potential, most ASEAN countries show promising prospects in digital industries and strategic manufacturing, which align with each country’s strengths, strategic industries, and global megatrends. Nonetheless, the risks associated with local content requirements remain a critical challenge. Countries with higher reliance on domestic inputs, such as Indonesia, face lower risks compared to those more dependent on imported components, such as Vietnam. Moreover, countries with strengths in services and the digital economy are likely to gain further advantages in an environment of heightened global trade uncertainty.

Fourth, each ASEAN country’s unique strengths generate opportunities to attract investment that aligns with the needs of different investor groups. For example, Thailand and Malaysia appeal to investors prioritizing infrastructure readiness and supply chain integration; Indonesia offers unparalleled potential for those seeking large domestic markets; and Vietnam and Singapore stand out for investors aiming to access export markets.

In summary, ASEAN retains significant potential to attract foreign investment. However, the evolving competitive landscape increasingly emphasizes value creation and ease of doing business. This suggests that countries capable of continuously strengthening qualitative factors will be best positioned to sustain their investment advantages. Based on the data assessment (see Appendix), Singapore clearly outperforms its regional peers, particularly in institutional and qualitative dimensions. This underscores the development gaps across ASEAN, especially in areas such as regulatory frameworks, government efficiency, infrastructure, and workforce skills. Addressing these qualitative factors will be essential to narrowing the gap and enhancing each country’s competitiveness.

At the same time, the distinct strengths of ASEAN countries—including Indonesia’s large domestic market, Vietnam’s labor and export competitiveness, and Thailand and Malaysia’s roles as strategic manufacturing bases—can be mutually reinforced through deeper regional economic integration and financial connectivity. Initiatives such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and Regional Payment Connectivity (RPC) provide platforms for leveraging collective strengths, mitigating volatility, and enhancing ASEAN’s long-term attractiveness as an investment destination.

References

ASEAN Secretariat. (2024). ASEAN Investment Report 2024 : ASEAN Economic Community 2025 and Foreign Direct Investment. Jakarta. Retrieved from https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AIR2024-3.pdf

Asia Regional Integration Center. (n.d.). Free Trade Agreements. Retrieved from https://aric.adb.org/fta-country

Boonyanuwat, T. (2011). Relative foreign direct investment attractiveness among ASEAN countries. Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.58837/CHULA.THE.2011.1906

EY. (2025, July). Incentives in ASEAN 2025. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/content/dam/ey-unified-site/ey-com/en-sg/services/tax/documents/ey-sg-incentives-in-asean-07-2025.pdf

OECD. (2022). OECD Regional Development Papers No. 36: Measuring the attractiveness of regions. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/measuring-the-attractiveness-of-regions_cc2921e6/fbe44086-en.pdf

OECD. (2025). Measuring foreign direct investment. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/foreign-direct-investment-fdi.html

The European House - Ambrosetti. (2025). Global Attractiveness Index: The thermometer of a Country’s attractiveness, 10th edition. Retrieved from https://www.ambrosetti.eu/en/site/get-media/?type=doc&id=23752&doc_player=1

UNCTAD. (2024). World Investment Report 2024: Investment Facilitation and Digital Government. Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD. (2025). World Investment Report 2025: International investment in the digital economy. Geneva: United Nations.

Appendix

1/ See also Supply Chain Diversification amidst Rising US-China Trade Tension: Implications for Key ASEAN Countries

2/ See also Global Minimum Tax: New Rule, Challenges, and ASEAN’s Response

3/ Include, Deglobalization, Technological Change, Environment and Sustainability, Demographic Shifts, Urbanization, and Rising Health and Wellness Consciousness

4/ See also Supply Chain Diversification amidst Rising US-China Trade Tension: Implications for Key ASEAN Countries

5/ See also Supply Chain Diversification amidst Rising US-China Trade Tension: Implications for Key ASEAN Countries