In 2021, the market for retail space in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region will remain flat or possibly weaken slightly from the position last year as it struggles against: (i) the ongoing domestic spread of COVID-19 and the effects of this on recovery; (ii) the increasing burden of household debt, which is leaving purchasing power fragile and encouraging consumers to show greater care over their spending; and (iii) the continuing slump in the tourism sector that has been caused by the delayed reopening of the country. The outcome of this has been to undercut domestic demand, and at present, this remains too weak to fuel a recovery in the industry. However, the situation should improve in 2022 and 2023, when the emergence of the country from the COVID-19 pandemic will help to boost consumer demand and to lift the economy, while progress on government infrastructure projects will also help to crowd in greater private-sector investment in related areas of the economy, including rented retail space. Nevertheless, the industry faces a serious long-term challenge in the form of the ever-rising popularity of e-commerce, as well as from the growth in the supply of retail space that will come from several large new projects that are currently being developed.

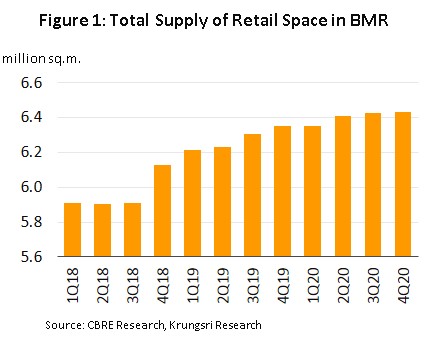

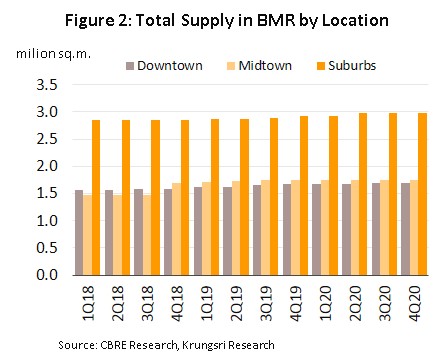

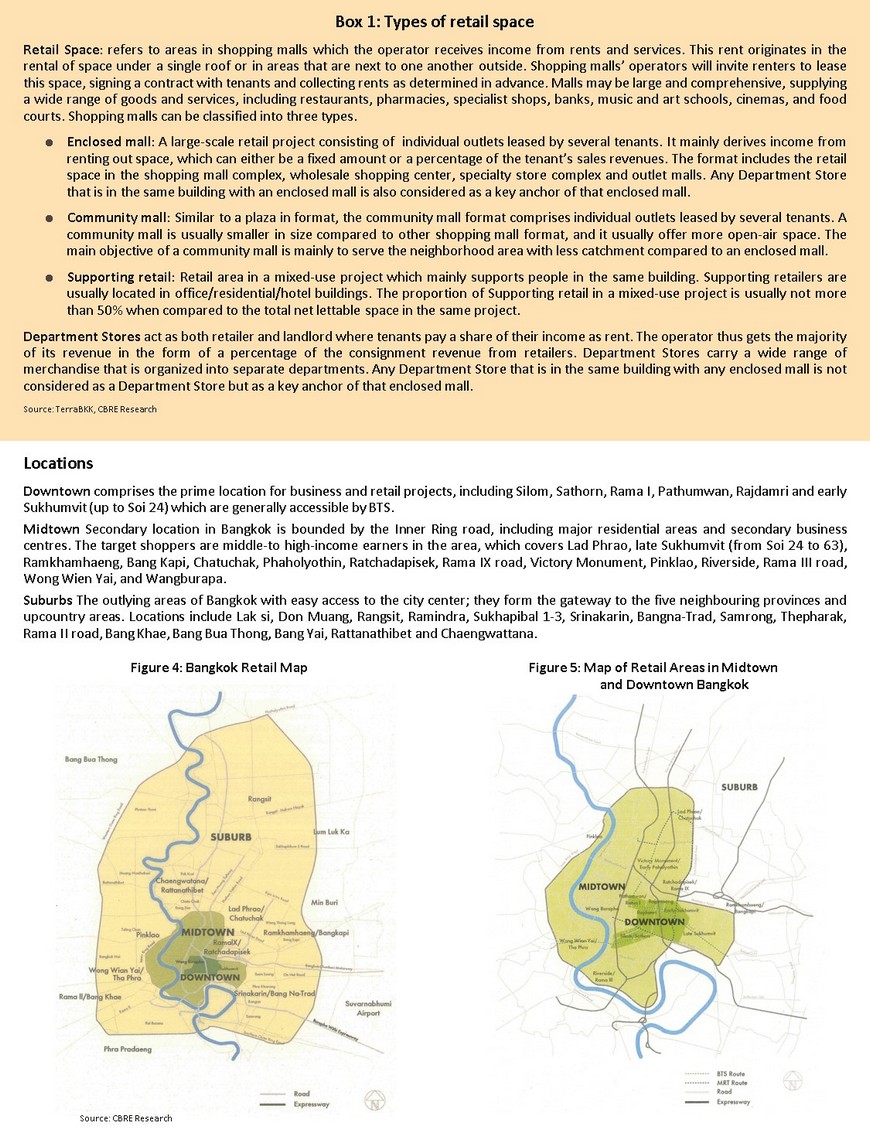

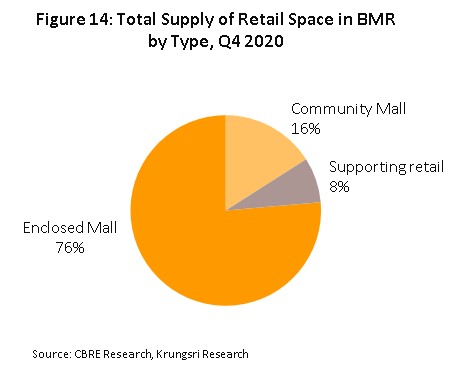

The greater part of Thailand’s retail space[1] is located in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR) and major regional centers[2]. Currently, the total supply of retail space in the BMR comes to around 6 million sq.m. (Figure 1), the majority of which is in shopping malls. This category includes only retail space for which the operator receives rental income. Shopping malls are sub-divided into enclosed malls, community malls and supporting retail (Box 1). Businesses operate primarily by developing the built infrastructure of a site and by providing amenities to renters and their main income then comes from the rental of this space.

Typically, leases will cover two types of charges: rental fees (around 40% of the total lease costs) and fees for the provision of utilities and services (60% of lease costs).

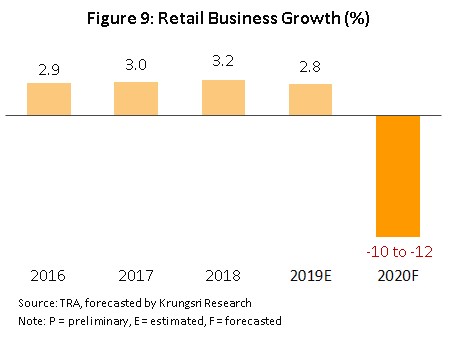

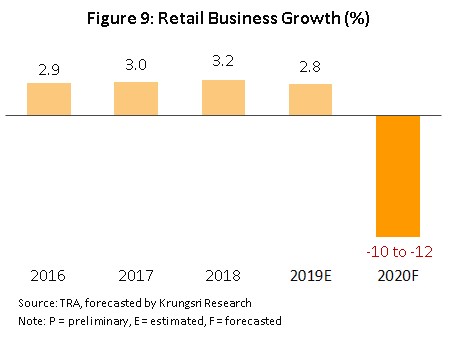

In 2019, the rate of growth in retail business dropped to 2.8%, decelerating with a weakening of consumer spending power and a slowing of the economy.

However, despite this, major investors in the retail sector moved forward with planned increases in investments as they looked to meet rising demand that is being driven by increasing rates of urbanization and work on new housing developments in more suburban parts of the Bangkok region. Given this,

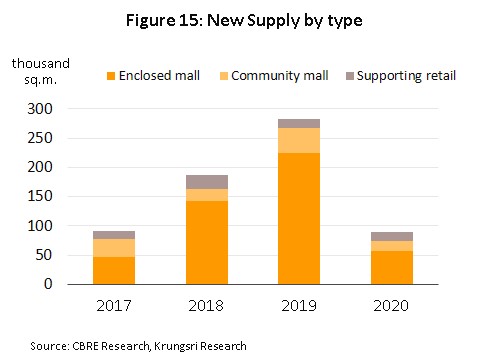

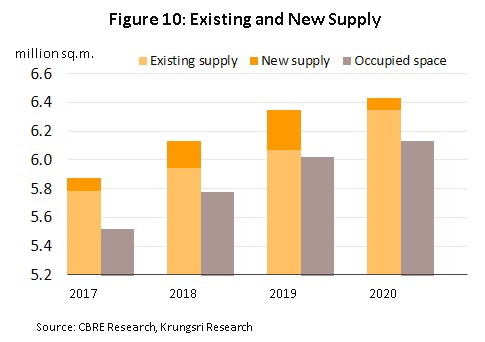

the cumulative total of retail space in the BMR rose 3.6% to 6.3 million sq.m., with most new supply being in enclosed malls (e.g., The Emsphere, Samyan Mitrtown, and Central Village), followed in importance by community malls and supporting retail.

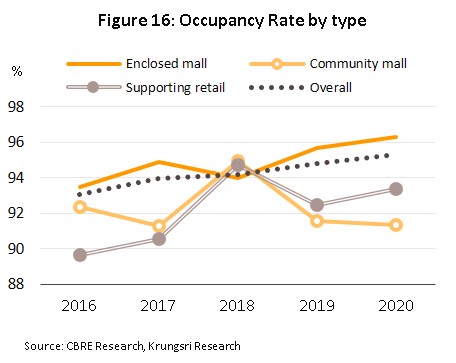

Demand for retail space also strengthened in the year, rising 4.2% to 6.0 million sq.m., and this then kept the occupancy rate at 94.8%, unchanged from 2018. This stronger demand came from both domestic retailers and distributors of international brands, which favor retail sites in malls that have easy access to the mass transit systems and that benefit from heavy footfall.

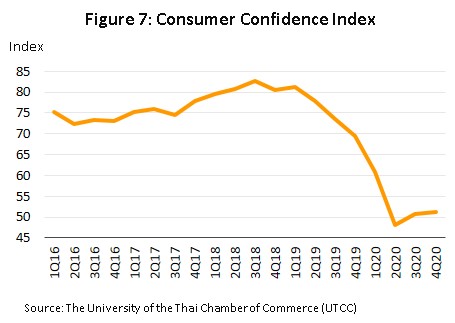

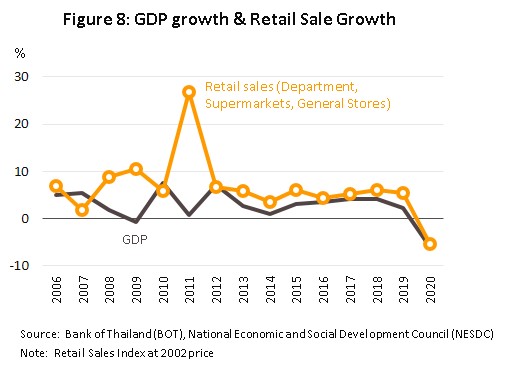

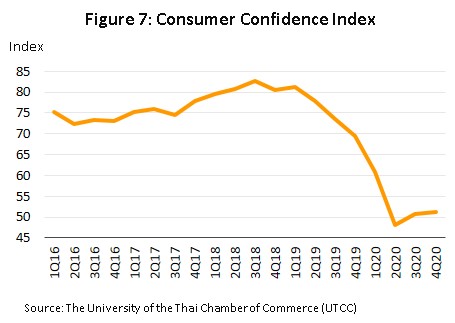

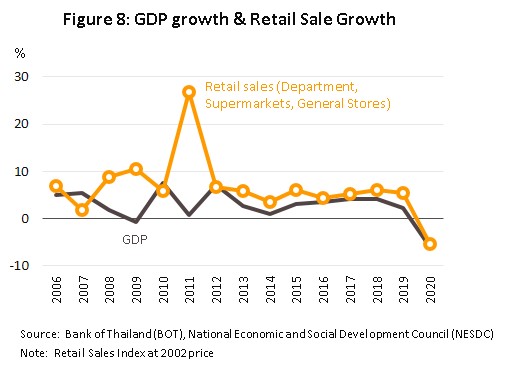

However, the situation worsened dramatically in 2020, and with the emergence of COVID-19, the retail sector experienced an extremely turbulent year. (i) Spending power among both domestic and international consumers was severely affected by the outbreak of COVID-19, which caused serious disruption to economic activity and cut Thai GDP by 6.1% in 2020. Consumer confidence also slipped to an all-time low (Figure 7) and tourist arrivals contracted 80%, piling pressure on retailers in locations that were particularly dependent on overseas spending (especially from Chinese tourists). (ii) In its initial response to the pandemic, the government ordered a nationwide lockdown that forced non-essential shops, including department stores and shopping malls, to shut temporarily, and this then helped to push the retail sales index into an unprecedented 5.4% contraction (Figure 8) and, as estimated by the Thai Retailers Association, to shrink the retail business by between 10.0% and 12.0% across the whole of 2020 (Figure 9).

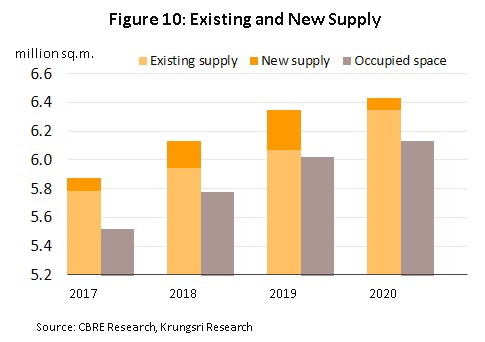

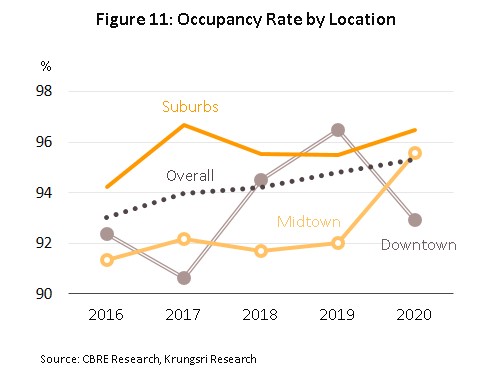

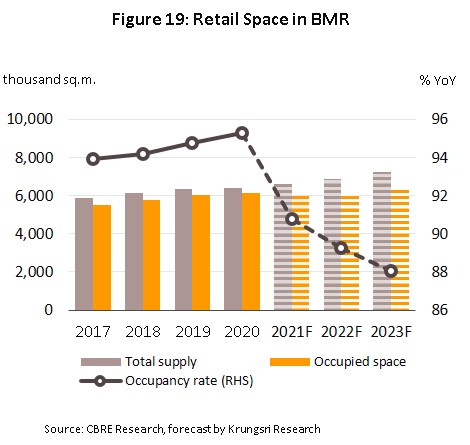

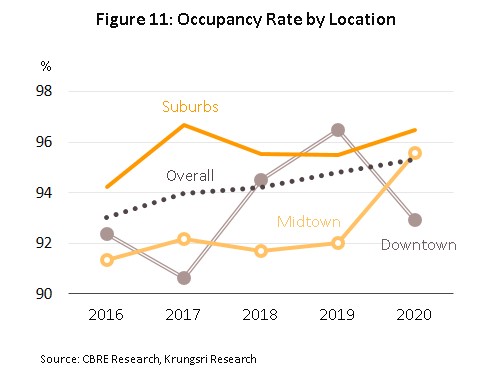

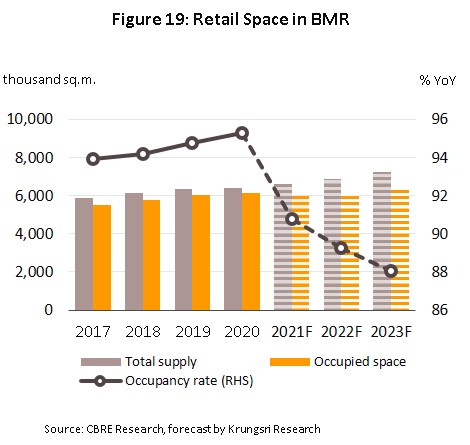

In response to these difficult conditions, players slowed the opening of new projects and as such, in 2020, supply expanded by just 90,000 sq.m., the lowest level of growth for many years. This then brought the total supply of retail space to 6.4 million sq.m., up 1.3% (Figure 10) but at the same time, demand rose 1.9% to 6.1 million sq.m., pushing the occupancy rate up from 94.8% at the end of 2019 to an average of 95.3% for the year (Figure 11). This surprising increase in demand amidst a severe recession is explained by the fact that leases are generally made for years at a time and it is usually not possible to give up a lease immediately. At the same time, many lessors reacted to the year’s sharp worsening of business conditions by offering leaseholders a cut in rates (generally assessed on a case-by-case basis) and this helped to persuade many renters not to walk away from their contracts, especially those that turned loss-making in the year and those that have e-commerce operations and which wanted to scale back their storefront presence. This then helped to prevent the overall occupancy rate from dipping, although it has had consequences for players’ income and profits.

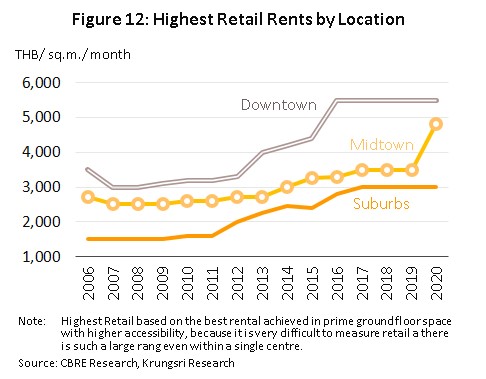

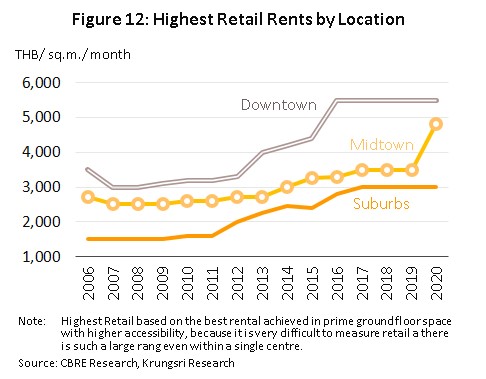

Overall, rental rates (as specified in leases and not including any discounts) have remained flat since 2017, having risen for a period prior to this. Players tend to keep occupancy rates high, especially in enclosed malls in downtown areas, where rental rates are highest.

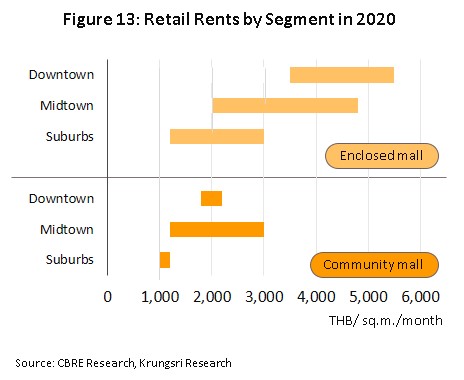

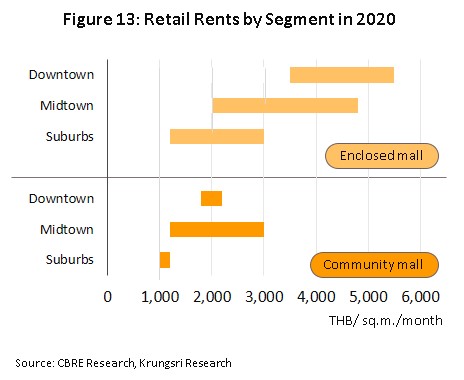

In 2020, average rental rates stood at THB 4,400/sq.m./month, though rates for space in midtown locations jumped from THB 3,500/sq.m./month in 2019 to THB 4,800/sq.m./month due to the extension of Bangkok’s mass transit system and the easier access that this then provided to much retail space outside the CBD, and renovation of stores such as CentralPlaza Ladprao, CentralPlaza Pinklao and The Mall Bangkapi, all of which are in midtown areas. However, prices for downtown and suburban space remained largely unchanged from 2019 (Figure 12). Considered by segments, enclosed malls were the most expensive, with prices running in the range of THB 1,200-5,500/sq.m./month, followed by community malls at THB 1,000-3,000/sq.m./month (Figure 13).

The situation for individual segments of the market is given below.

- Enclosed malls

- For many years now, the supply of space in enclosed malls has risen. These projects tend to have a large footprint, usually somewhere between 70,000 and 200,000 sq.m. and in some cases even larger, but restrictions imposed by town planning regulations and the shortage of suitable sites in downtown locations has encouraged investors to open projects in suburban areas that have the residential or business community required to support a new development. Examples of these include Mega Bang Na, CentralPlaza Chaengwattana, CentralPlaza Salaya, Central Westgate and Central Festival Eastville. Operators of downtown enclosed malls have, on the other hand, tended to invest in upgrading and modernizing facilities as they try to exploit the international tourist market, which grew at an average rate of 9.9% per annum over the years 2015 to 2019.

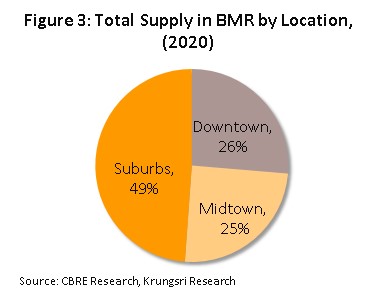

- In 2020, the supply of space in enclosed malls rose 1.2% YoY to 4.9 million sq.m. (76% of the supply of all retail space), while demand totaled 4.7 million sq.m., up 1.8% YoY. As such, the 2020 occupancy rate averaged 96.3%, an increase on 2019’s rate of 95.7%.

- Community malls

- Community malls have helped to meet increasing demand that has been driven by changing consumer behavior and a desire for a more convenient and more easily accessible shopping experience. Thus, consumers increasingly prefer to purchase the goods and services needed in daily life at sites near their homes or places of work, and this has then led to an expansion in the supply of community malls, though this has also been helped by the lower investment overheads of these compared to other similar developments. The supply of community malls has thus exploded, increasing in number by an average of 18% per year between 2012 and 2014 (source: Collier International) but rising competition, both between community malls and with other types of mall located in nearby areas, has meant that some developments have failed and have had to be abandoned. In the period 2015-2019, supply growth slowed, though at an annual average of 7.1%, this still raced ahead of growth in demand, and with the latter expanding by just 2.9% per year, occupancy rates have tended to weaken.

- In 2020, the supply of space in community malls totaled 1.0 million sq.m. (16% of all retail space in the BMR), which represented an increase of 1.1% from a year earlier. Demand rose 0.8% to 0.94 million sq.m., and the occupancy rate thus remained relatively stable at 91.4%.

- supporting retail

- supporting retail are a new type of rented retail space that began to be developed in 2017-2019. These offer retail space alongside other types of activity, most often office space, and these are in particular found in downtown locations. The new supply of supporting retail has grown by an average of 3% per year, matching expansion in the supply of mixed-use developments[3]. supporting retail typically meet demand from customers who are in the same building for a different purpose, and thus they are found alongside offices, condominiums and hotels.

- In 2020, supporting retail had a total footprint of 0.49 million sq.m. (8% of all BMR retail space), though this was a rise of 3.4% from the 2019 total. Demand strengthened 4.4% to 0.46 million sq.m., and the occupancy rate therefore stood at 93.4%, up from 92.5% at the close of 2019.

Industry Outlook

The forecast for 2021 is for the market to remain flat or to fall back slightly. This will be a result of the continuing negative impact of COVID-19 on Thailand’s economic recovery, together with the rising burden of household debt, which is now eating into consumer spending power and encouraging shoppers to be much more careful about their spending. In addition, the delayed reopening of the country means that the tourism sector remains mired in difficulty and receipts from tourist spending have collapsed; the Ministry of Tourism and Sports sees 2021 income from foreign arrivals reaching just THB 300 billion, compared to THB 1.9 trillion in 2019. These factors have thus conspired to erode income and profits for landlords and to put occupancy rates on a downward trend, and although government stimulus measures directed at household spending have helped to keep the economy ticking over and to support retailers located in malls and shopping centers, recovery in demand has been limited. Unfortunately, domestic spending power remains weak and this may not be sufficient to power recovery for landlords leasing out retail space. The latter are thus still waiting for a recovery in demand from foreign tourists, though when this is seen, the boost to sales and the accompanying strengthening of the recovery will help to put landlords on a much more secure footing.

The market for retail property will tend to improve in 2022 and 2023 on: (i) domestic economic growth that is expected to average 3.0-4.0% per year and that will then support higher private-sector consumption, a strong driver of recovery in retail sales; (ii) progress on the build out of government-backed infrastructure projects, which will help to stimulate other parts of the economy, including investment in the construction of retail space; and (iii) the reopening of the country and the rebound in foreign tourism that this will support. It is forecast that there will be 9.05 million foreign arrivals in 2022 and a further 20.7 million arrivals a year later (Figure 17), and this will be an important factor sustaining greater spending and, through this, recovery in the retail property market.

Over the next three years, landlords of retail space will be increasingly challenged by the rise of the e-commerce sector. The latter received a huge boost from the COVID-19 crisis, which encouraged consumers to experiment with carrying out a much greater proportion of their day-to-day shopping online, and although online shopping currently accounts for only 3.0-4.0% of all retail sales, the market has high potential for growth and the Thai Retailers Association estimates that this share will rise to over 10% as early as 2023. Given this, owners and lessors of retail space will need to look carefully at their business models as they attempt to meet these marked changes in consumer behavior.

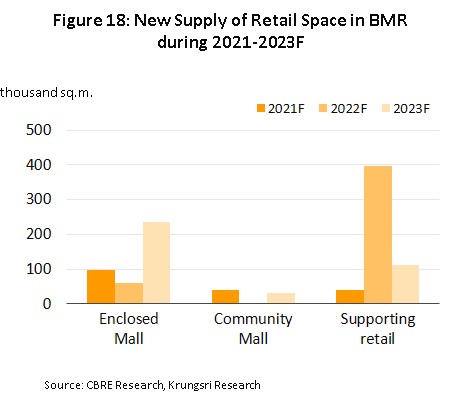

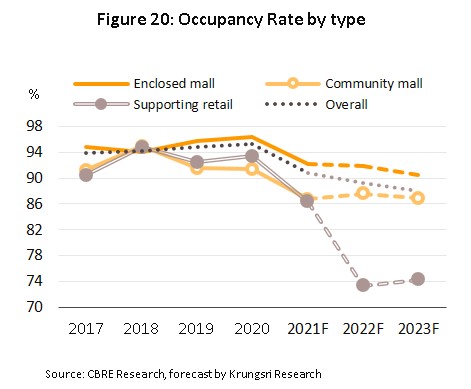

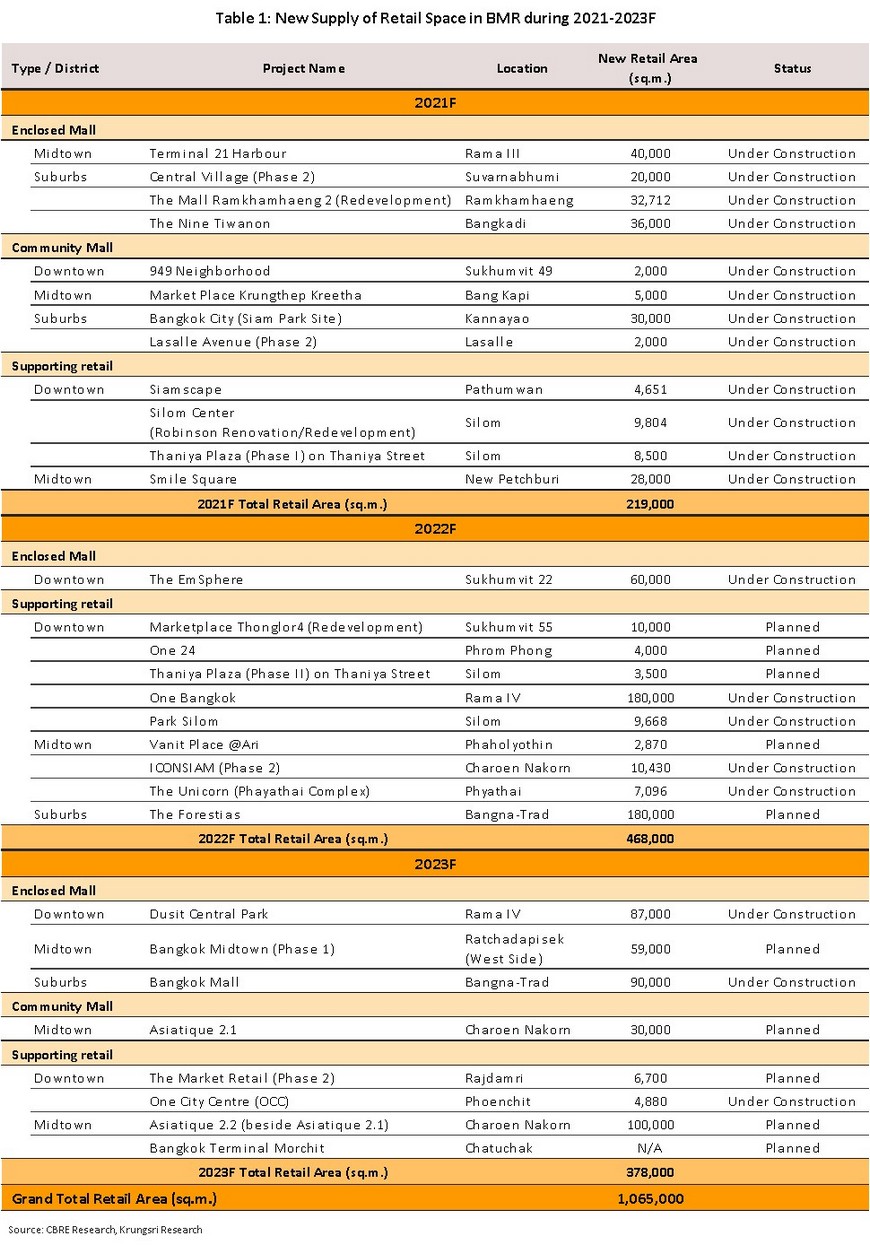

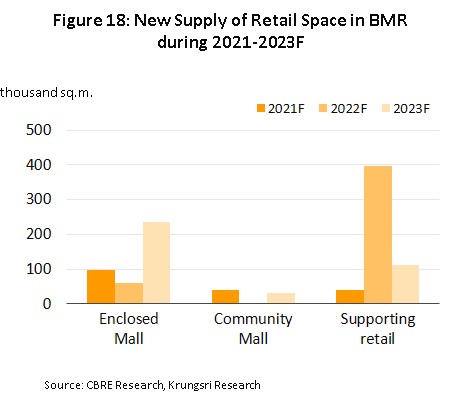

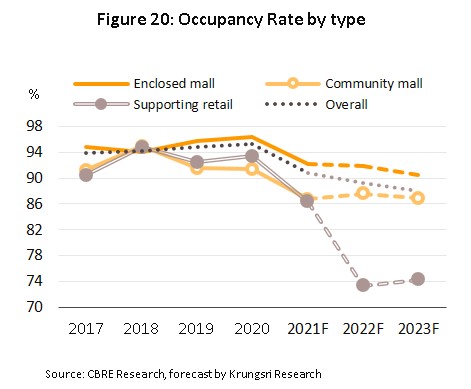

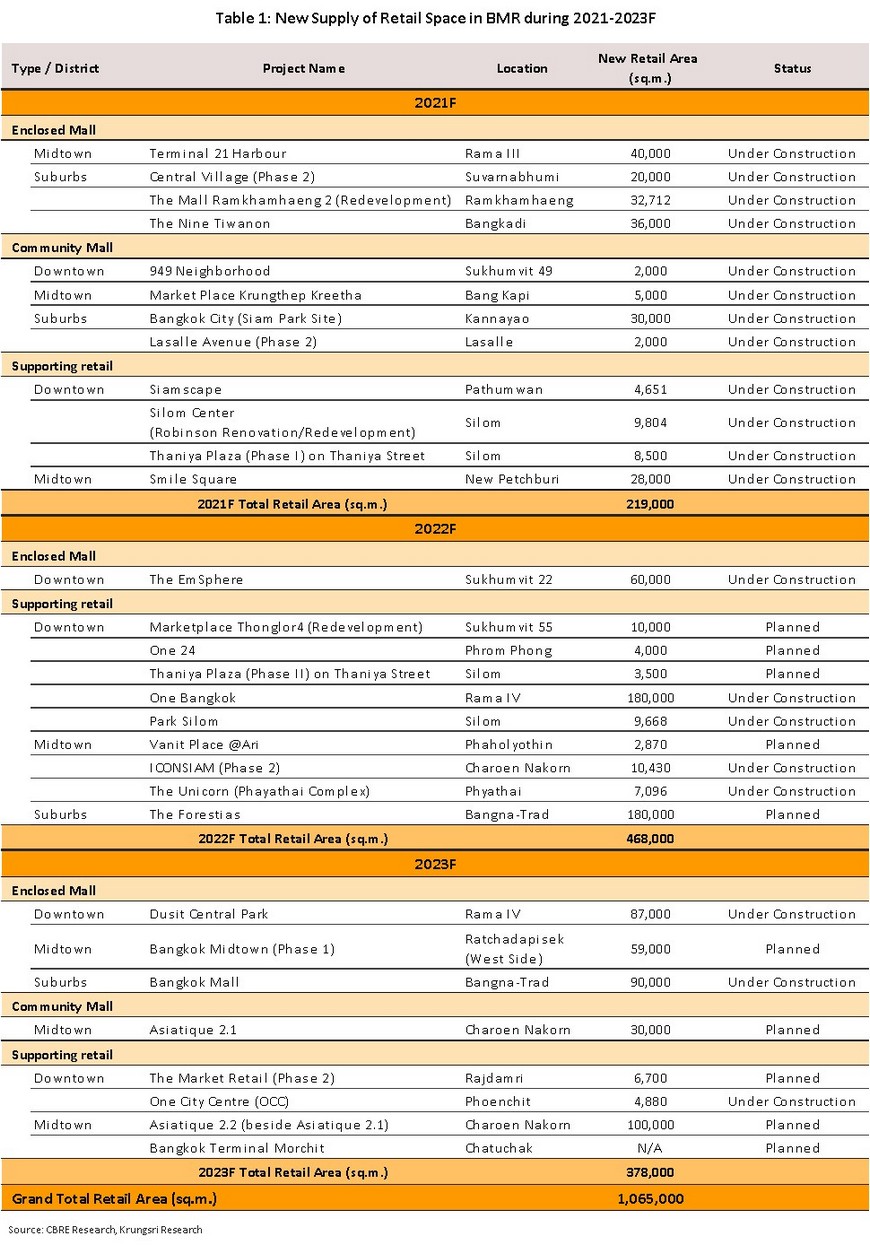

Overall, demand for rented retail space in the BMR is expected to contract by 2.2% in 2021 before returning to growth of 2.3-4.0% per year in 2022 and 2023. At the same time, landlords are moving ahead with plans to steadily release new properties to the market over the next 3 years that will have a total footprint of over 1 million sq.m. (including, for example, Central Village (Phase 2), the Rama 3 Terminal 21 development, Smile Square, and The Emsphere). Around 460,000 sq.m. of this new supply will be completed in 2022, and up to 80% will be in the form of supporting retail (Figure 18). Given this substantial increase in supply, average occupancy rates are expected to slip to 88-91% (Figure 20), though simultaneously, market rents are also being weakened by the impact of COVID-19, which has forced some renters to give up their leases and encouraged others to negotiate discounts.

- Enclosed malls: Supply will steadily expand, while demand will recover only slowly and this discrepancy will pull down occupancy rates to 90-92% from the average of 95.3% established over the previous three years. The shortage of space that is suitable for development in downtown areas means that developers and landlords will instead invest in upgrading and modernizing existing sites as they try to meet the varied and diverse lifestyles of modern consumers. Because of this, average rents will remain flat or increase only slightly.

- Community malls: Growth in supply will outpace any rebound in demand, which will remain weak due to the ongoing impact of COVID-19 on the spending power of typical community mall shoppers (i.e., middle- to lower-income consumers). The latter is expected to take an extended period of time to recover and the negative effects of this on tenants’ sales and income means that occupancy rates are forecast to slide to 87-88% from the 3-year average of 92.6%. In this environment, landlords will also find it difficult to raise rents.

- supporting retail: Supply will expand rapidly in the coming period, though in 2022 and 2023, this will rise by as much as 27% per annum. The proportion of supporting retail in downtown locations will also increase as large mixed-use developments are completed and come onto the market. However, demand will not strengthen at anything like the same rate, with this generally coming from consumers visiting mixed-use developments for other purposes (e.g., work, attending meetings, visiting the gym or accessing residential accommodation). The surge in new properties will therefore tend to weaken the occupancy rate and in 2021, this is forecast to fall to 86% before dropping as low as 73-74% in 2022 and 2023 (compared to a 3-year average of 93.4%).

A changing business landscape, the increasing ease of shopping online and the shifts in consumer behavior encouraged by the COVID-19 pandemic have all pushed landlords to change the strategies that they use to entice consumers into their malls and shopping centers. This has included modernizing sites and building in new functions, for example by coordinating and combining indoor and outdoor spaces, increasing the provision of family-friendly zones, and allocating areas for pets, all of which helps to present a more varied shopping experience that better meets the new and evolving needs of modern consumers. Landlords are also now showing more flexibility in their dealings with existing tenants. Details of this are given below.

- Rents will be more flexible and contract periods will be shorter: Instead of traditional fixed rates, rental contracts would increasingly take the form of ‘partnership rents’ calculated as a percentage of store income, with a minimum sales guarantee. Landlords are also tending to be more flexible about rental terms and conditions, for example by offering shorter contracts or variable rents depending on the use to which a space is put, for example, by quoting different rents for kitchens and eating areas (source: CBRE Research).

- Smaller rental units: Services are increasingly moving online and it is predicted that demand for offline stores will drop by 20-40% relative to its pre-COVID-19 level (source: CBRE Research). Renters of retail space are tending to carry out a greater proportion of their business activities online, and as businesses try to balance their shop sizes with demand from shoppers who still prefer to make offline purchases or who need access to aftersales services, this is translating into storefronts shrinking in size or being given up altogether for renters that are managing multiple outlets.

Beyond this, difficult market conditions, the shortage of sites for development, steep land costs, and the high concentration of shopping malls and, therefore, stiff competition that exists in downtown areas in Bangkok is limiting opportunities in central parts of the city. As they expand their customer base among Thai consumers as replacements for lost and only very slowly recovering tourist markets, developers are therefore increasingly investing in new projects in more suburban parts of the BMR, as well as expanding into upcountry markets in the provinces, where spending power is now sufficient to make these investments an attractive proposition.

Krungsri Research’s view

The market for retail space in the BMR will slowly recover from 2021 to 2023, helped by gradually strengthening consumer spending power and government efforts to stimulate the economy. However, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to weigh heavily on economic growth and retailers that are dependent on tourist spending, especially those in downtown areas that are especially reliant on foreign shoppers, are unable to look forward to any immediate resolution of their difficulties. Given this, competition will tend to worsen, and this will then limit any increase in profitability among landlords.

- Retail space in BMR (not including community malls): Given the slow strengthening of current demand and ongoing investment to meet anticipated future demand for retail space, the forecast is for players to see only slight increases in income. Players with a presence in the market benefit from the obstacles (including high investment costs) that stand in the way of new entrants, and as such existing players dominate the market, enjoying advantages in terms of their financial strength and their access to sites with high potential. Because it is difficult to expand into new sites downtown, operators in central Bangkok will instead put their efforts into modernizing retail spaces in order to better meet the needs arising from the wide variety of lifestyles present in their customer base, and this will then tend to slightly increase rental rates.

- Community malls in BMR: Income is expected to remain flat for this group. Because community malls are generally small, investment costs are not prohibitive and it is relatively easy to find sites that are suitable for development, especially in cheaper, more suburban areas. This will then encourage new players to enter the market and the supply of properties can thus be expected to rise. The latter will tend to stoke higher levels of competition, but at the same time, continuing weakness in consumer spending power among mid- to lower-income earners will mean that any growth in demand will likely remain relatively weak and recovery will be a protracted affair. In light of this, renters’ income will remain under threat and it will be difficult for landlords to raise rents.

[1]Retail Space is defined as shopping malls are sub-divided into enclosed malls, community malls and supporting retail.

[2]Major regional centers’ refers to important tourist destinations and centers of economic development in the regions of the country, excluding the five provinces surrounding Bangkok. Examples include Chiang Mai, Nakhon Sawan, Phitsanulok, Khon Kaen, Nakhon Ratchasima, Chonburi, Rayong, Phetchaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Songkhla, Surat Thani, Krabi, Phang Nga and Phuket.

[3]Mixed-use real estate developments include both commercial and residential uses. Mixed-use developments may thus contain retail units, office space and residential accommodation within the same project.

.webp.aspx)