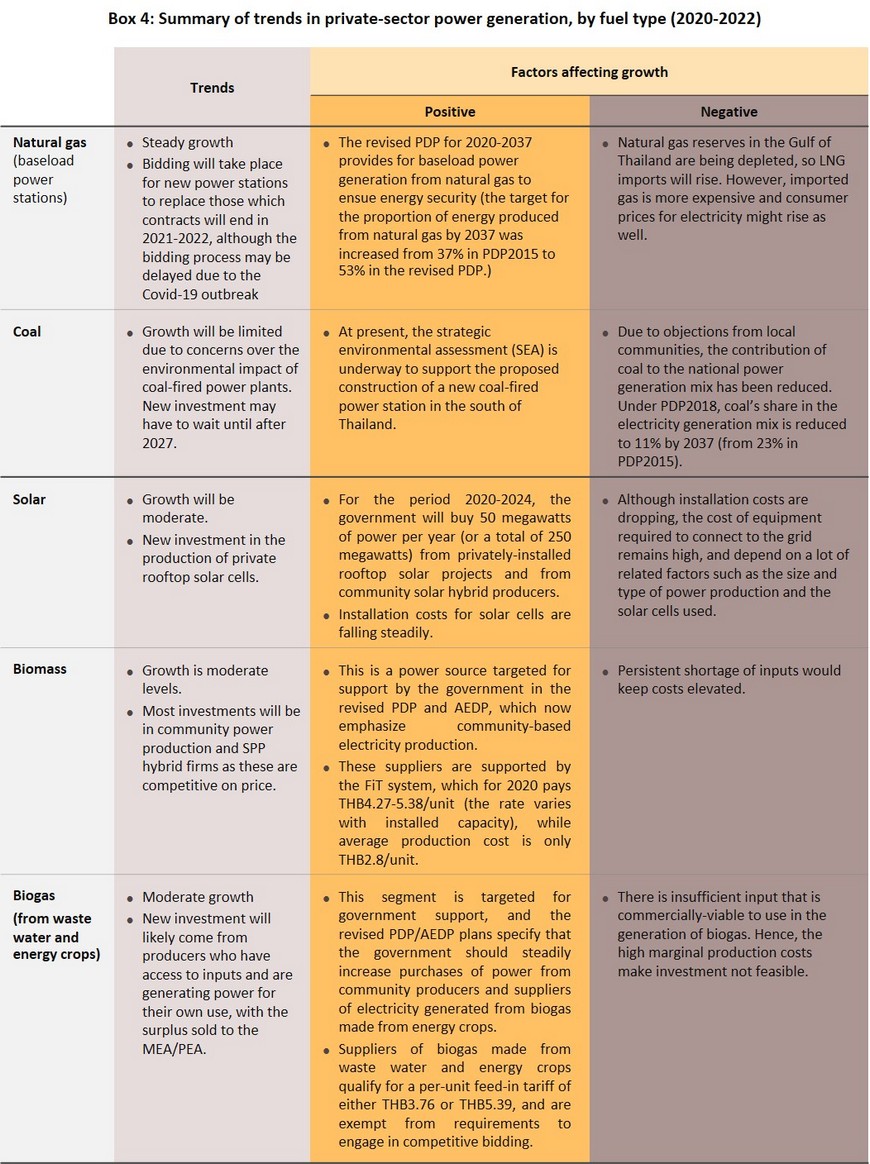

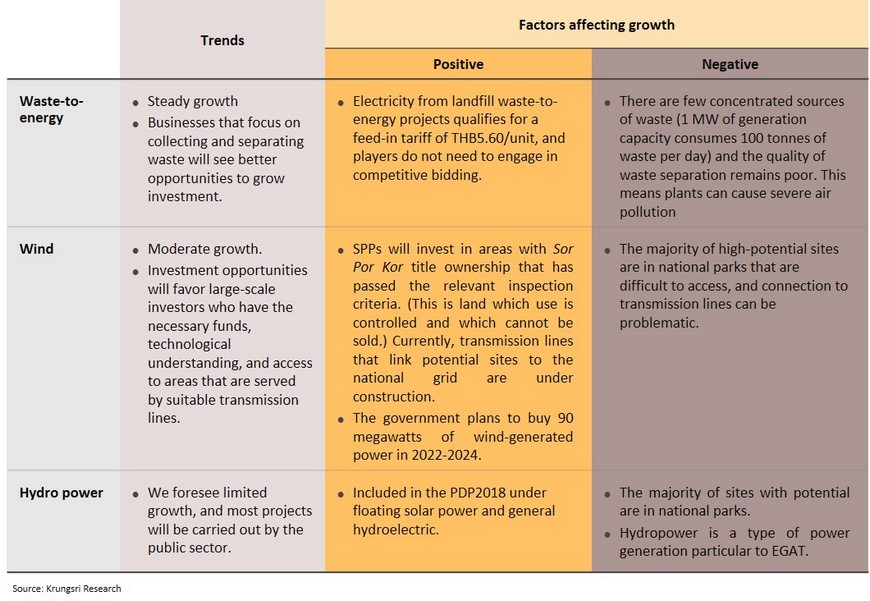

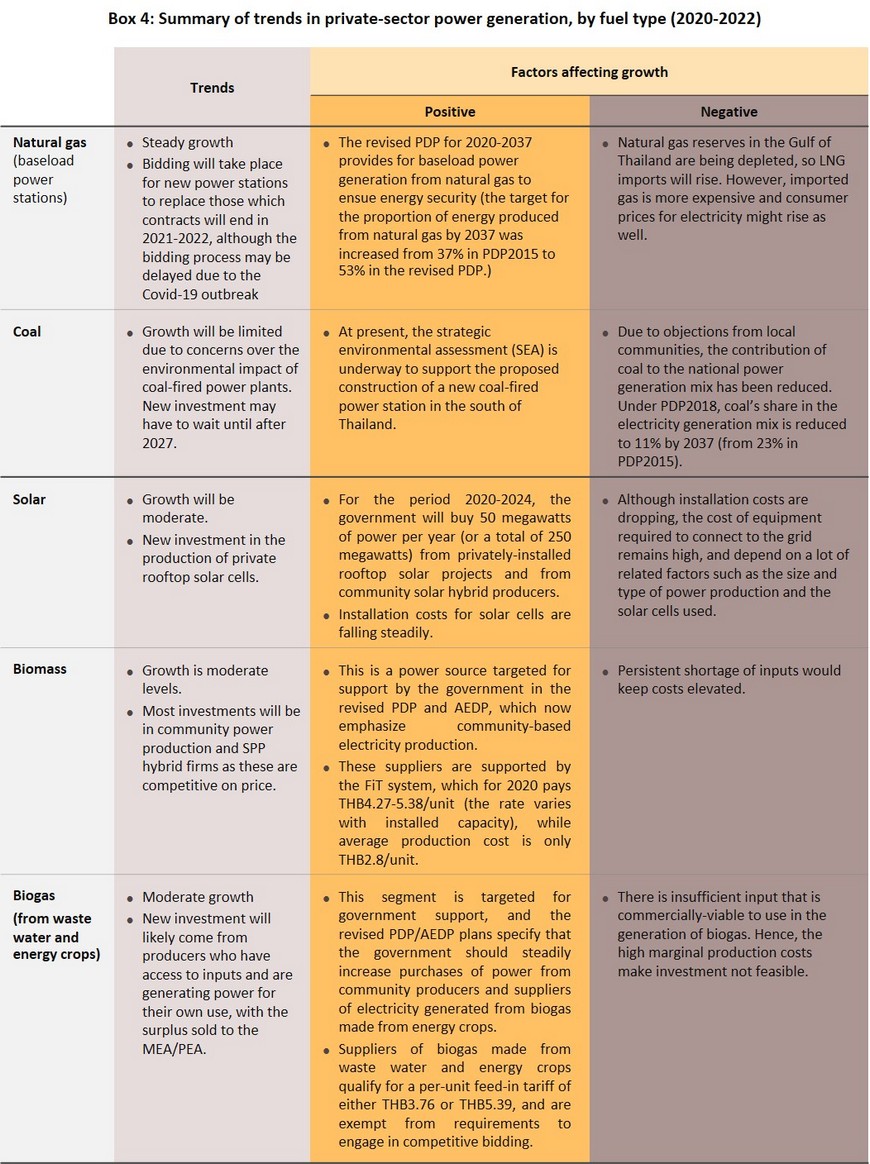

In the first half of 2020, the government had rushed to contain the Covid-19 pandemic by imposing a nationwide lockdown that effectively halted most economic activities (manufacturing and services) in the country. For full year 2020, this will reduce electricity demand by 2.0-3.0%, compared to 2.7% growth in 2019. However, in 2021 and 2022, demand is expected to rebound and private-sector power plant operators should see better business conditions as the economy returns to near-normal. Meanwhile, generation capacity will continue to be driven by the government’s investment support measures under the Power Development Plan and Alternative Energy Development Plan. After 2021, we anticipate greater investment from players in the rooftop solar, biomass, biogas, and waste-to-energy segments. These players will benefit from government support that will take the form of a steady increase in electricity purchases, and they would also be more competitive with better cost-control and access to raw materials. In the wind power segment, the government will start to buy wind-generated power in 2022-2024, when high-voltage lines to connect wind farms to the grid should be completed.

Overview

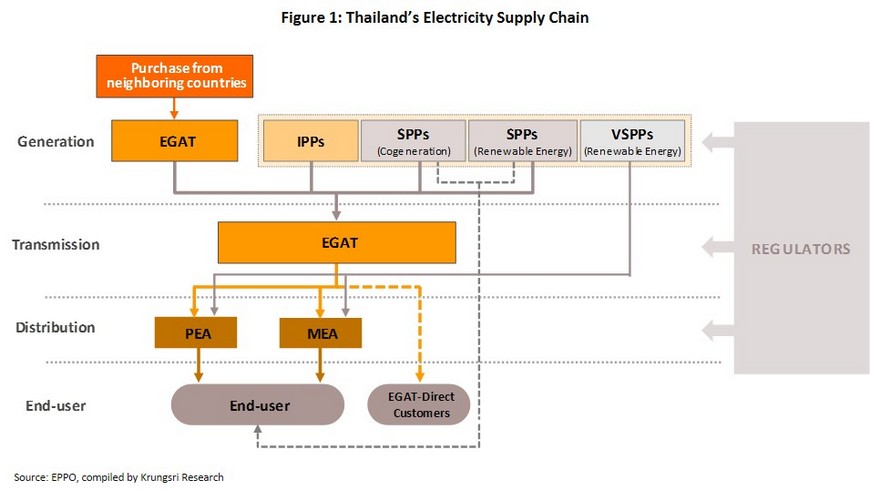

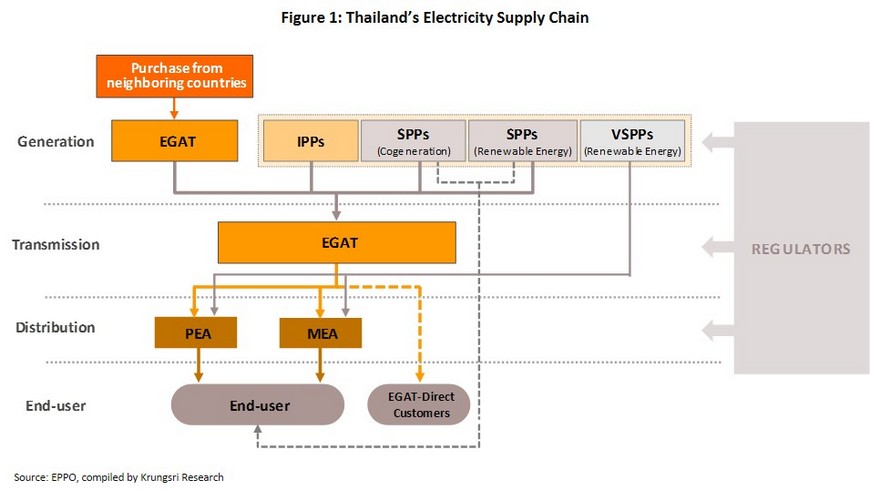

Thailand’s power generation industry is structured in line with the enhanced single-buyer model with state bodies being the sole buyers and distributors of power through the national grid. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) is both a producer and, by purchasing power from private-sector ‘independent power producers’ (IPPs) and ‘small power producers’ (SPPs), a buyer of electricity. It also has a monopoly in the distribution of electricity in the country. In addition, the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) and the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) are responsible for distributing power as well as buying electricity from ‘very small power producers’ (VSPPs) (Figure 1).

The most important features of the Thai electricity generation industry are as follows: (i) Unlike other goods, electricity cannot be stored and must be distributed to users immediately through a transmission and distribution system. (ii) Expanding capacity to meet future demand requires long-term planning because power stations take 5-7 years to construct depending on the type of power plant. This long-term plan is the national power development plan, which main objective is to ensure that electricity supply is sufficient to meet future demand. (iii) Hence, state bodies have a major role in managing generation and distribution, as well as setting tariffs and investment targets to increase supply to the national grid.

Electricity demand growth will depend on the following:

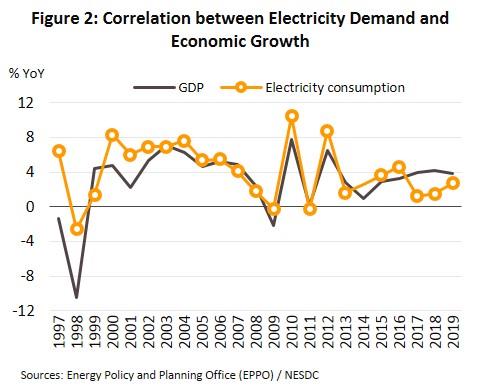

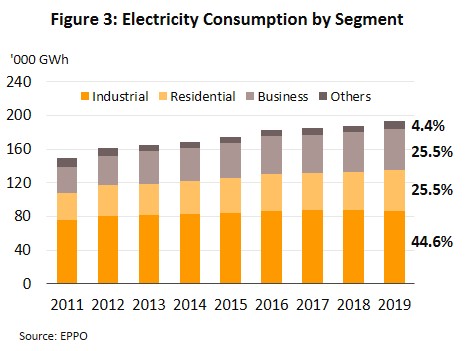

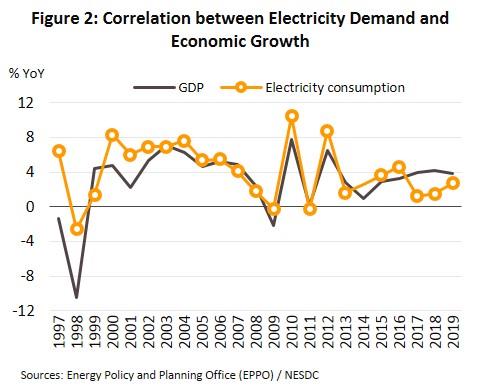

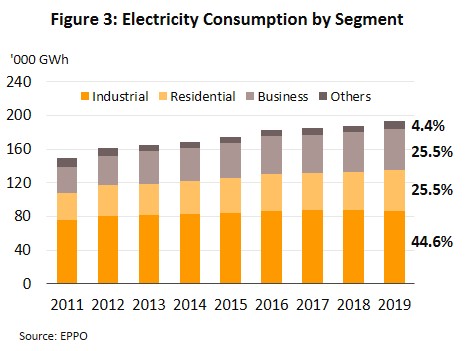

- Rising domestic demand. This would be determined by the health of the economy. Generally, demand for electricity grows at 0.9-1.1 times the rate of GDP growth (Figure 2). In 2019, the major sources of demand were industrial, business, and household sectors which accounted for 44.6%, 25.5% and 25.5% of national electricity consumption, respectively, and others 4.4% (Figure 3). Within the industrial sector, the food industry was the biggest consumer, followed by steel & basic metals, electronics, auto assembly, and plastics production. In the services sector, there was strongest demand from serviced apartments and guest houses, followed by department stores, hotels, retailers, and wholesale operations.

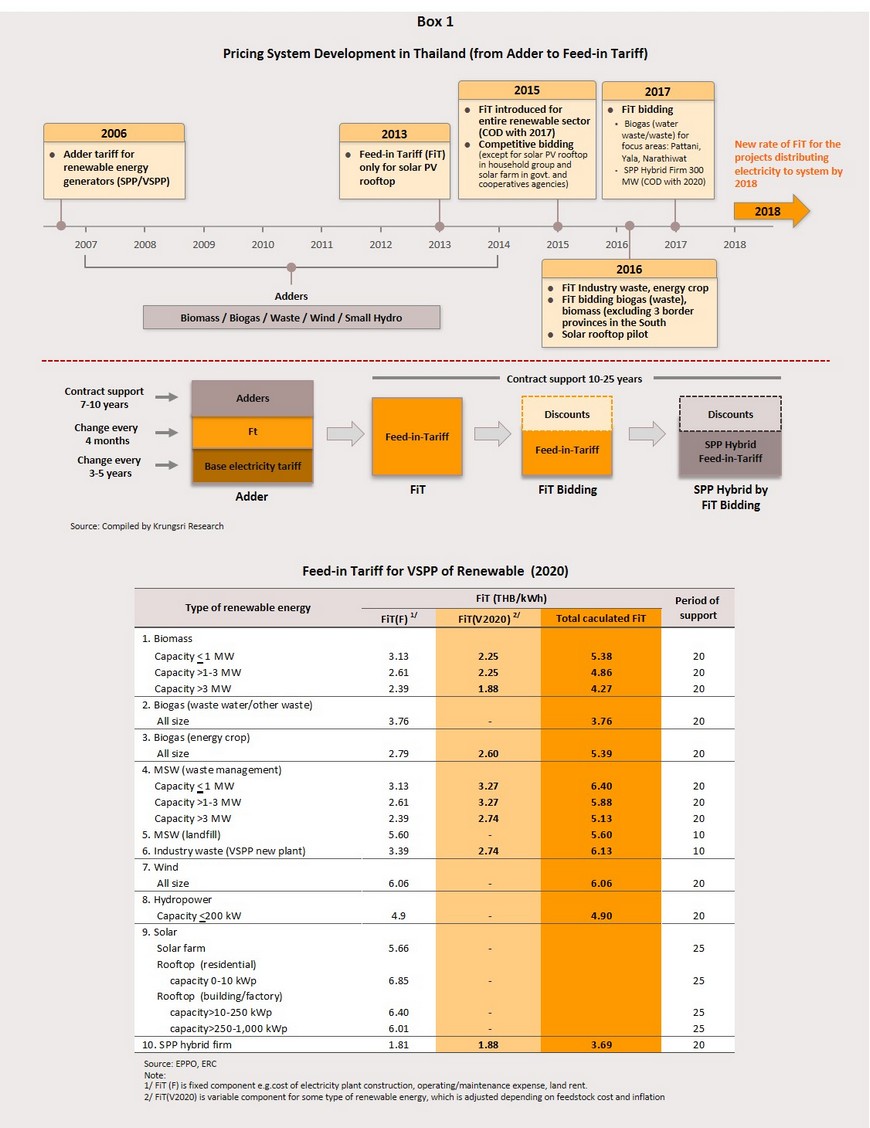

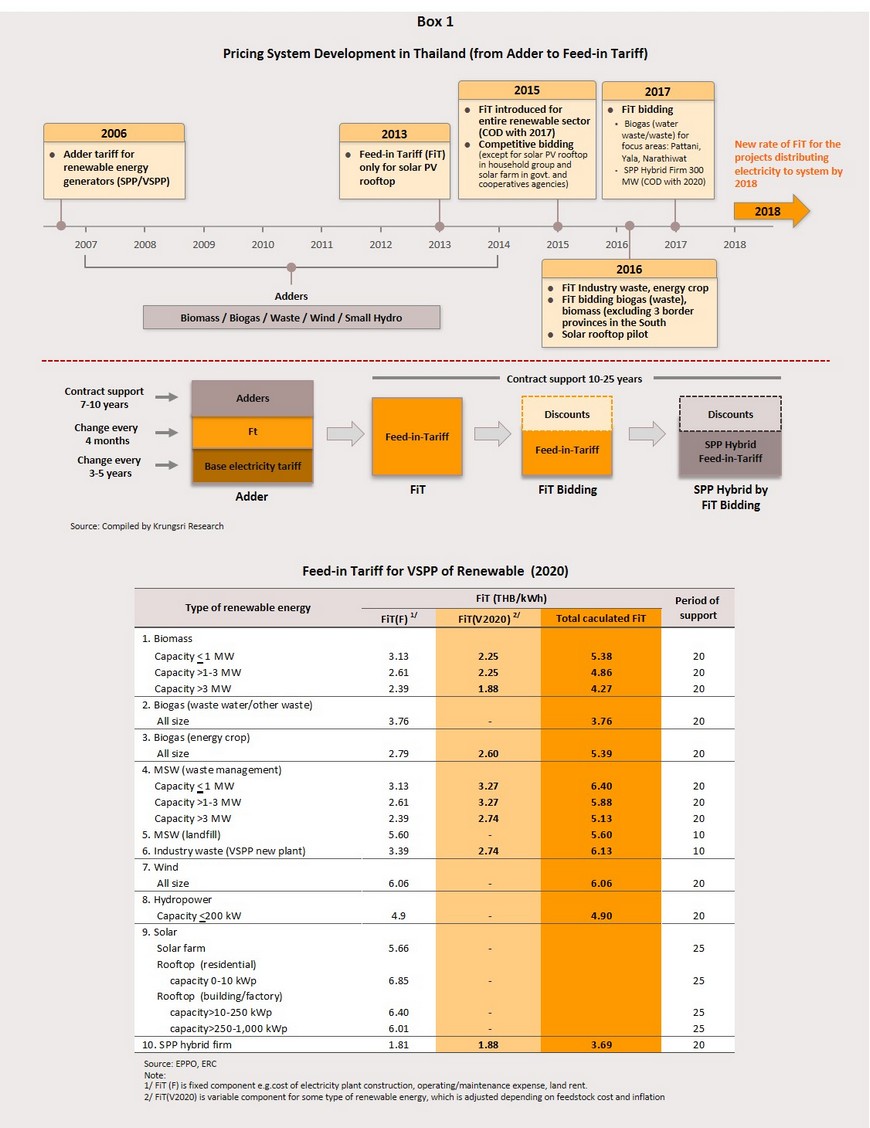

- Government policy: (i) The Power Development Plan (PDP) and the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) lays out the desired total generating capacity for each type of power plant[1]. (ii) They also set the pricing for renewable energy (because producing power from renewables costs more than electricity produced from fossil fuels, i.e. natural gas, coal, and oil), and this is now used to determine the feed-in tariff[2] (FiT). Previously, the adder system was used to calculate payments[3] (Box 1). (iii) The government also has plans to expand the power distribution network to support the increasing generation capacity, especially from renewable sources.

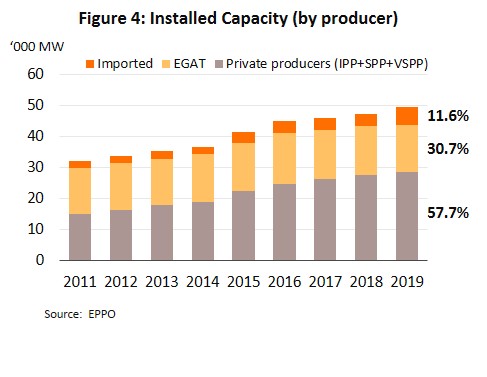

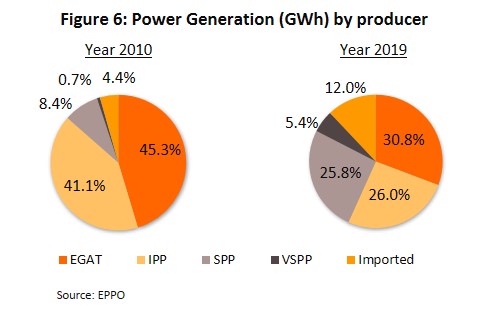

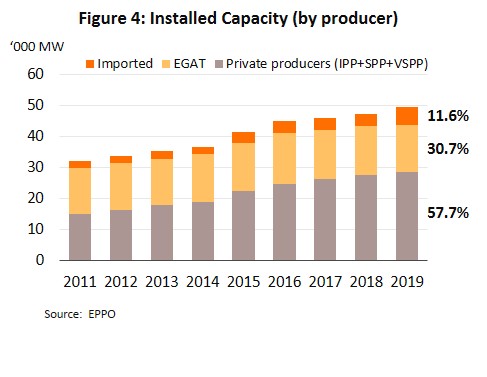

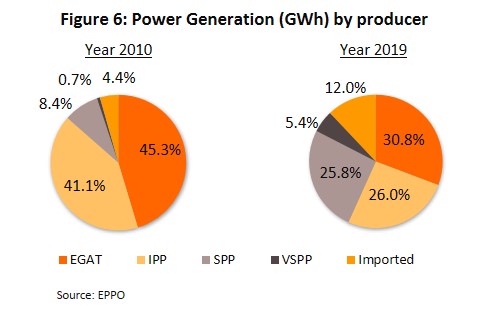

Private power producers have an increasing role in the sector (Figure 4). In 2019, the private sector controlled 57.7% of power generating capacity (or 49,304 megawatts), split between IPPs (30.3% of total power supply) and SPPs and VSPPs (27.4%). The remaining 42.3% is produced by EGAT, which is also responsible for buying-in power from neighboring countries.

Power plant operators can be split into two groups, by fuel source.

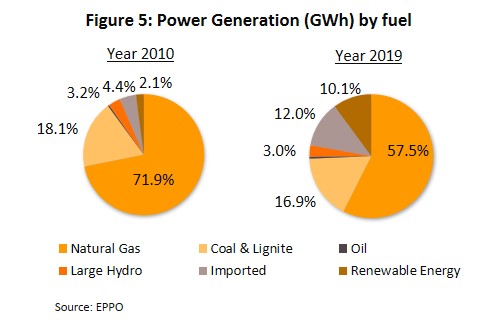

- Fossil fuel and hydropower. This includes plants that are fueled by natural gas, coal/lignite and oil, as well as large-scale hydropower plants. In 2019, 57.5% of the electricity produced in Thailand were fueled by natural gas (down from 72.0% in 2010), followed by coal, hydroelectric and oil (Figure 5).

- Renewables and alternative sources. This includes plants fueled by biomass (generally agricultural waste), biogas (including manure, waste water from agro-processing industries, and bioenergy crops), waste (consumer and industrial), solar, wind and micro-hydro plants. Electricity from these sources contributed 10.1% of national electricity consumption in 2019 compared to only 2.1% in 2010.

Currently, proven reserves (P1) of natural gas in the Gulf of Thailand is 6.4 trn cubic feet[4], while annual national consumption is 1.3 trn cubic feet (source: Department of Mineral Fuels, December 2018). This means Thailand has sufficient supply for only another 5-6 years, after which we would have to import gas, most probably from Myanmar. Because of this, the PDP emphasizes the increasing use of renewables in power generation.

There are three major groups of private-sector players in the power-generating sector.

Independent Power Producers (IPPs)

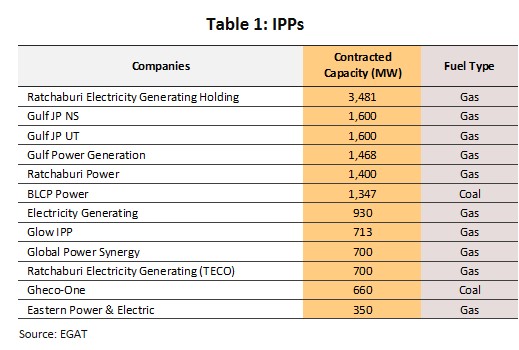

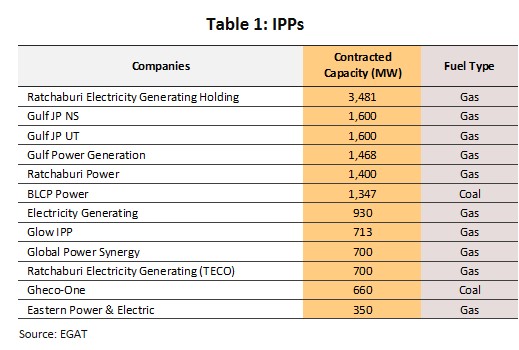

- Total installed generating capacity: Over 90 megawatts. These producers mainly use natural gas and coal to fuel their power stations. The most important players are (i) Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holdings, (ii) Gulf JP NS, (iii) Gulf JP UT, (iv) Gulf Power Generation, (v) Ratchaburi Power, (vi) BLCP Power, (vii) Electricity Generating, (viii) Glow IPP, (ix) Global Power Synergy, (x) Ratchaburi Electricity Generating, (xi) Gheco-One, and (xii) Eastern Power & Electric.

- Revenue: The revenues of players in this group are exposed to low risk because the IPPs sign long-term (25-year) power supply contracts with EGAT. Revenue is generated from two sources: (i) a guaranteed ‘minimum intake’ specified in the contract with EGAT, and (ii) power supply directly to the grid to meet demand. Hence, their revenues are dependent on national electricity consumption, although some players also get receipts from their investments in power-generating facilities overseas, including Myanmar, Laos PDR, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia.

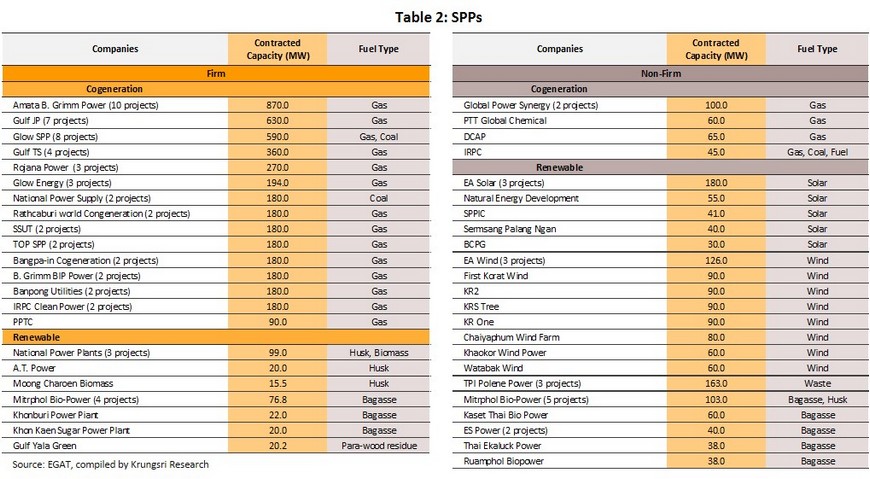

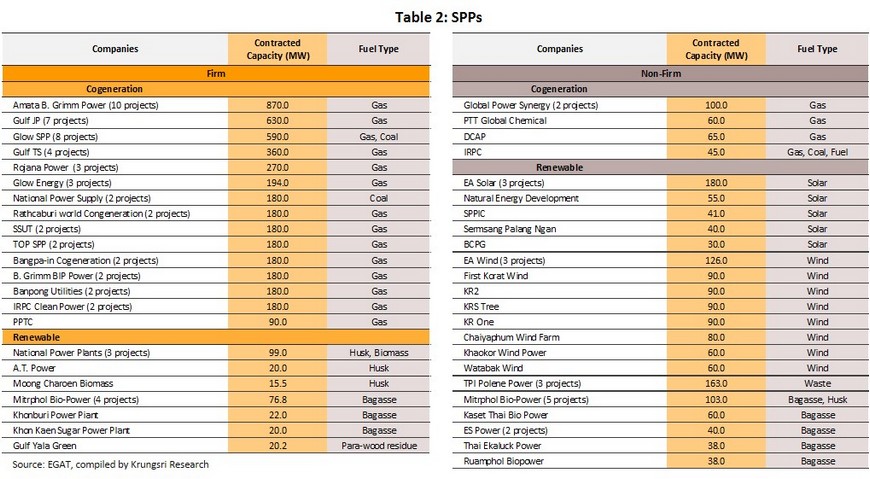

- Installed capacity required to qualify as an SPP: 10-90 megawatts. SPPs typically generate power from natural gas, coal, oil and renewables, and sell mostly to EGAT. A small proportion of their output is sold to industrial consumers that are located near the SPP’s power stations. SPPs can be split into (i) ‘firm’-type SPPs, which have a 20-25-year contract to supply power to EGAT and are normally fueled by natural gas or coal, and (ii) ‘non-firm’ SPPs, which have 5-year contracts (extendable in 5-year increments) and are normally fueled by renewables such as such as solar power, wind power, waste and biomass.

- Revenue: SPPs have two primary sources of revenues. (i) Derived from long-term contracts with EGAT that, like IPP contracts, come with a minimum revenue guarantee. This means SPPs only have mild exposure to risk of weak earning. (ii) Derived from supplying electricity to industrial consumers located close to the power stations. However, this revenue can fluctuate according to the overall economic conditions and the individual industry cycles. Beyond this, some players also receive returns on investments in power assets overseas, including solar-based electricity generation assets in Japan, China and Taiwan, and wind-power assets in Vietnam.

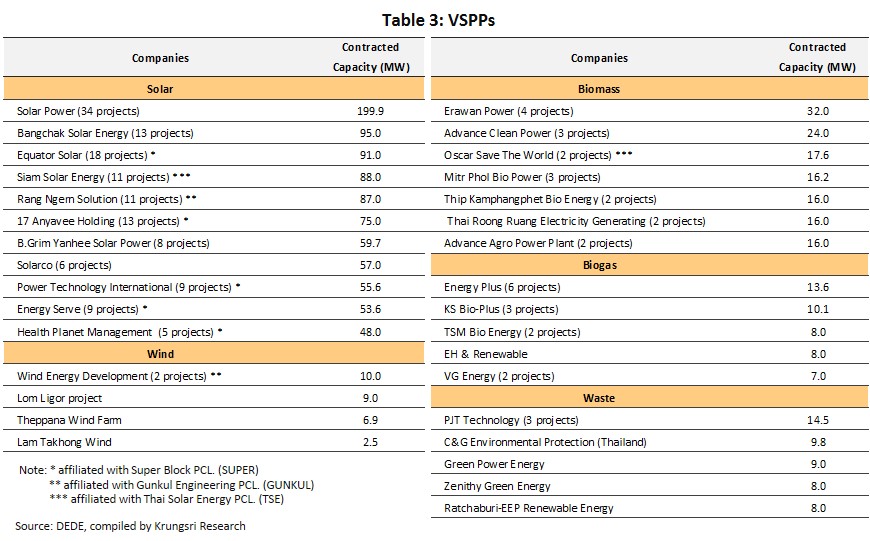

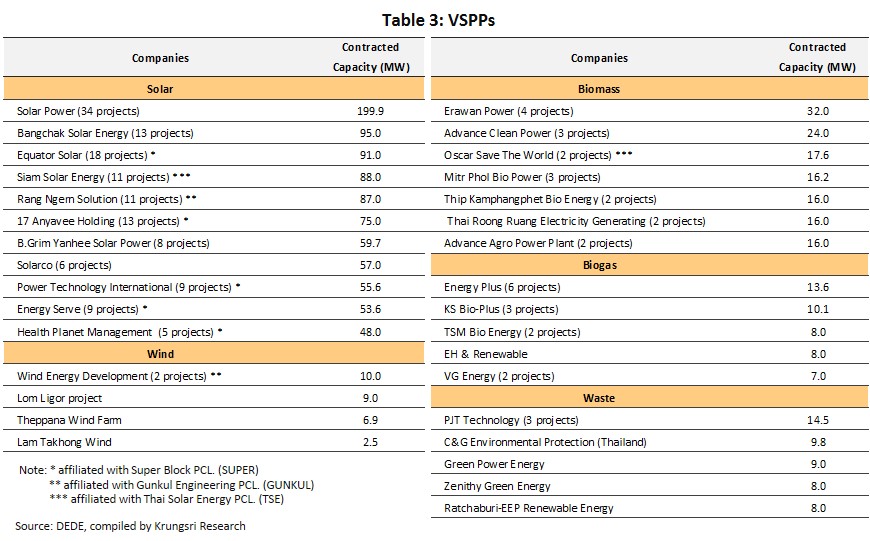

- Installed capacity to qualify as a VSPP: Under 10 megawatts. VSPPs typically generate electricity from renewables (including solar, wind, hydropower, biomass, biogas and waste) for their own use, and sell any surplus production to MEA or PEA at rates determined by the feed-in tariff (FiT) for that particular generating technology and other circumstances for as long as the project runs (Box 1). The majority of VSPPs that sell electricity fueled by renewables are involved with engineering, designing, procurement and construction, or manufacturers of solar cells and related equipment, as these operators have the necessary expertise to install and maintain the renewable electricity systems.

- Revenue: VSPPs supply electricity to the MEA or the PEA according to conditions specified in their contracts. They will receive payment when the electricity enters the grid (i.e. it is a COD system). Players that generate power from natural sources (i.e. solar, wind or hydropower) are likely to run at a loss in the first 1-2 years due to high cost of building and outfitting production sites, but following this initial period, the situation will improve supported by revenue from the sale of electricity. However, earnings could be volatile for players which produce electricity from biomass, biogas and waste, because of limited access to and fluctuating prices of raw materials.

Between 2013 and 2019, the share of electricity produced by SPPs and VSPPs had surged with government support under the AEDP and increasing purchases of electricity from this group of suppliers. By 2019, their contribution to the national energy mix had jumped to 5.4% of all electricity sold through the grid from only 0.7% in 2010 (Figure 6).

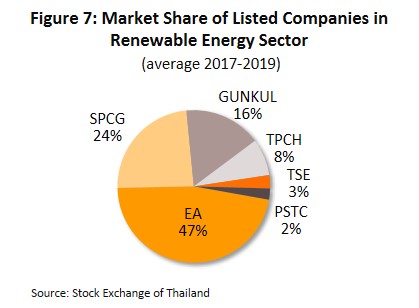

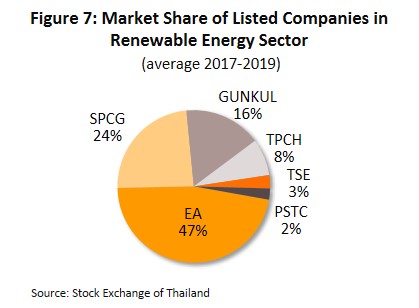

The major players in the energy sector that are listed on the stock exchange and that produce power from renewables include Energy Absolute (EA) (solar and wind), SPCG (solar), Gunkul (solar, wind and biomass), TPC Power Holdings (TPCH) (biomass), Thai Solar Energy (TSE) (solar and biomass), and Power Solution Technologies (solar, biomass and biogas) (Figure 7). Some of these companies also invest in renewables-based power generation assets abroad.

Situation

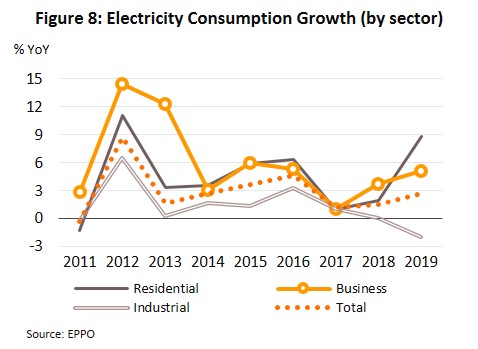

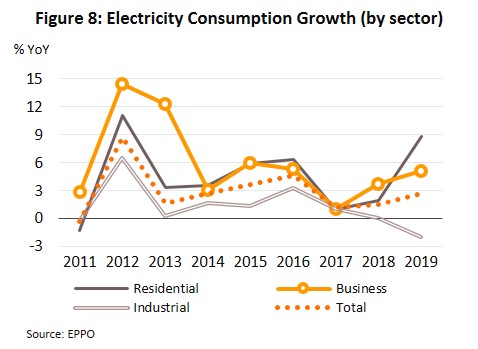

National electricity consumption rose by 2.7% to 192,960 gigawatt-hours in 2019, accelerating from +1.5% in 2018. This was driven by greater demand from the business sector and households, which each accounted for 25.5% of electricity consumption. Demand from households rose by 8.8% (Figure 8) due to exceptionally hot weather, which pushed up peak demand in May to a new high of 30,853 megawatts. Demand from the business sector increased by 5.9% due to greater energy consumption at apartments & guesthouses (+13.6%), hospitals & clinics (+6.3%), and restaurants (+5.5%). But power consumption by the industrial sector (44.8% of total) slipped 2.0% due to weaker demand in the following sectors: steel & basic metals (-9.9%), auto assembly (-6.3%), electronics (-6.0%), and food (-0.9%).

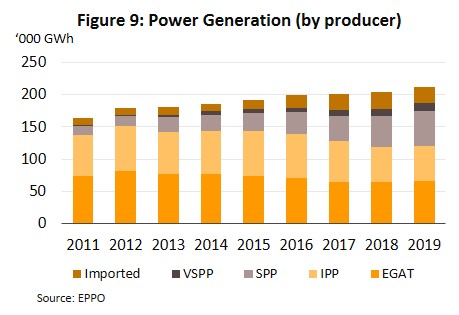

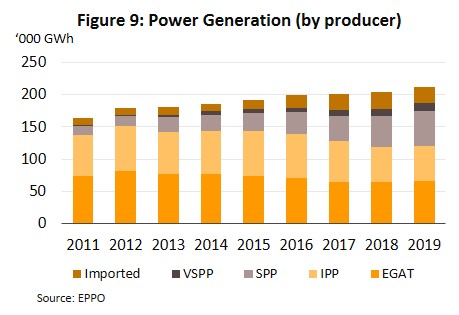

2019 national power generation rose by 3.7% (from +1.6% in 2018) to a total of 212,050 gigawatt-hours. Following a 0.8% increase in 2018, the volume of electricity supplied to the grid by EGAT (account for 30.8% of electricity produced in the country) rose by 1.4%. IPPs (26% share) saw their production increase by 1.6%, following a decline of 14.7% in 2018. SPPs and VSPPs (31.2% combined share) expanded power generation by 12.2% and 9.9%, respectively (Figure 9). This uptick for SPPs and VSPPs was driven by the push in the past few years to buy electricity generated from renewables, and the subsequent signing of supply agreements with EGAT. In 2019, the volume of electricity from renewables supplied to the grid (10.1% of total) rose by 19.4%. Natural gas-generated electricity (primary source of electricity with 57.5% share) rose by 4.8%, reversing from -4.0% in 2018. Electricity generated from coal (16.9% of total) was almost unchanged (+0.1%), while total electricity imported from neighboring countries (12.0% of electricity consumption) fell by 4.2%.

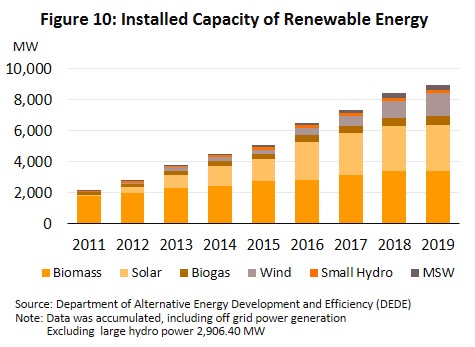

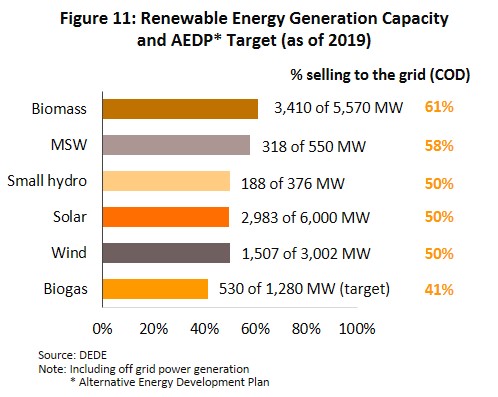

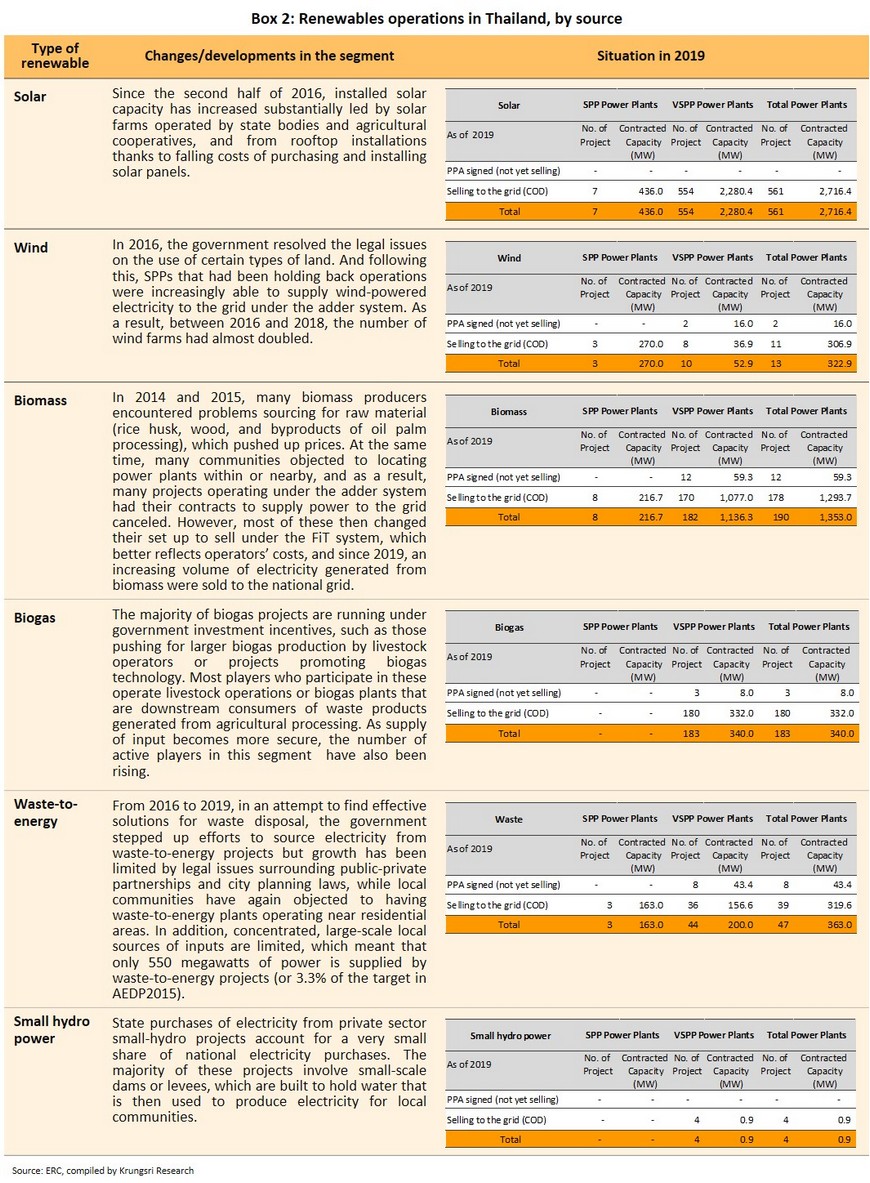

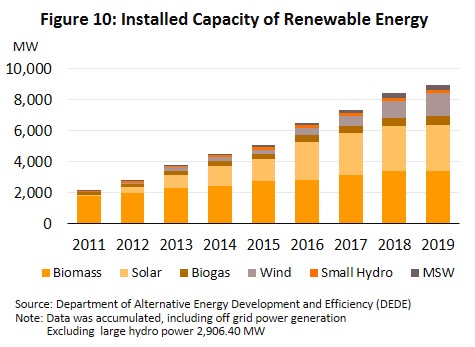

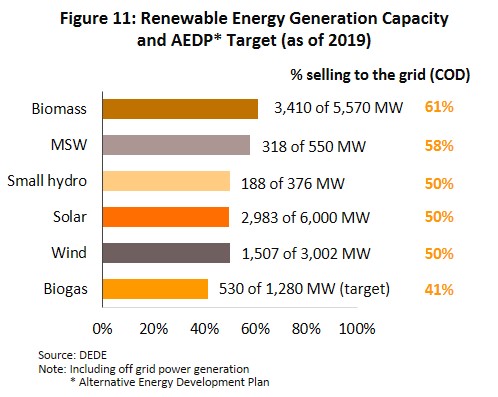

In 2019, there was 8,935 megawatts[5]of renewables generating capacity was installed and ready to sell power to the grid, which represented an increase of 5.8% from 2018 (Figure 10). The largest share was taken by wind and biogas, for which installed capacity rose by 36.6% and 4.9% each. This growth in renewables generation capacity was driven by: (i) SPP suppliers of wind-power, which continued to distribute electricity through the grid as per their contracts with EGAT; (2) a biogas project in southern Thailand starting to sell to the grid; and (iii) progress in phase 2 of the program to install solar projects on sites operated by the government and agricultural cooperatives, with electricity from these installations now being available through the grid. However, when we compare the targets set in the 2015 Alternative Energy Development Plan with the current installed capacity, the national power system is only 53% of the planned 16,788 megawatts of renewables capacity envisioned for 2036. So far, power generated from biomass has made the greatest progress at 61% of target. This is followed by waste-to-energy (58% of target), micro-hydro (50%), solar (50%), wind (50%) and biogas (41%) (Figure 11).

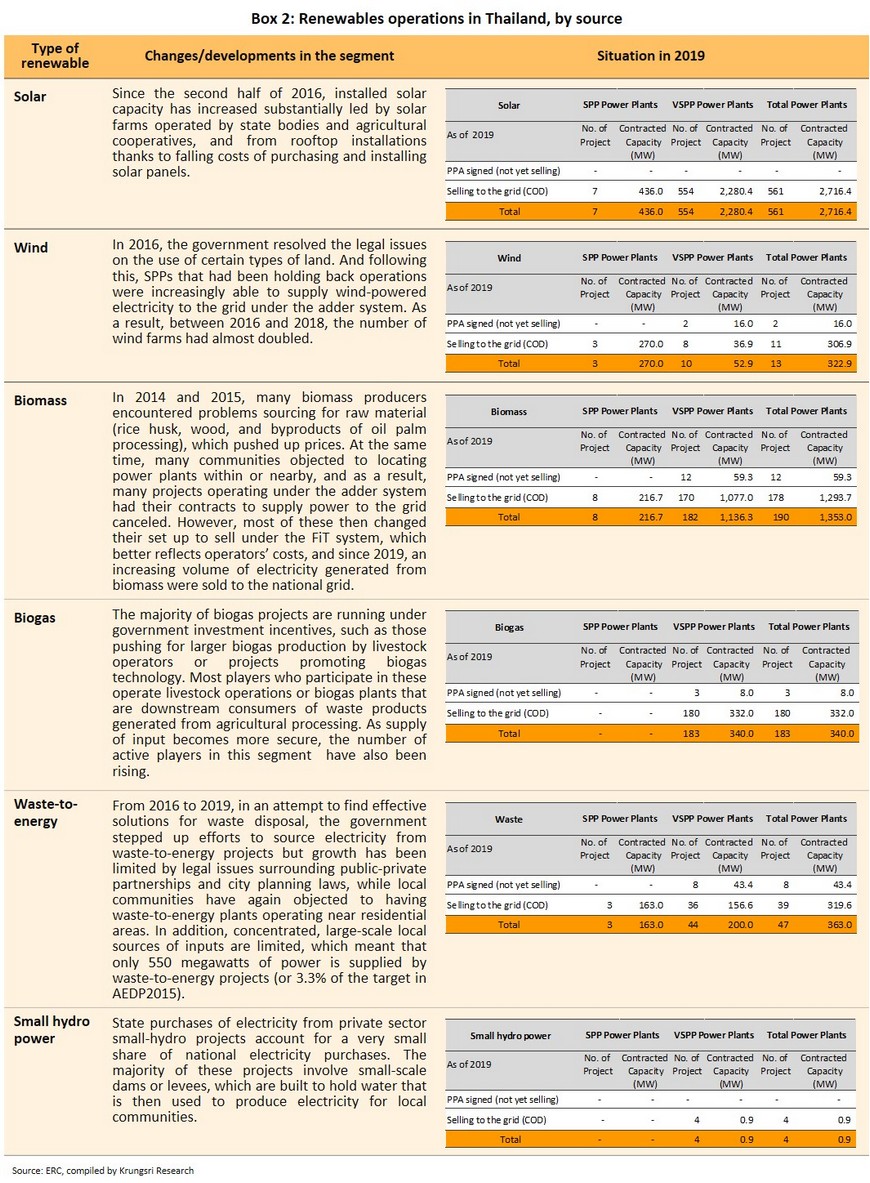

Looking at the structure of private-sector renewables projects, in 2019, including projects that received support under the adder and FiT systems, there was a total of 973 SPP and VSPP projects selling electricity to the national grid. These had a contracted capacity of 4,965.5 megawatts. The largest capacity expansion was in waste-to-energy projects, followed by biomass, biogas, wind, and rooftop solar (Box 2).

Electricity demand for 5M20 shrank by 3.2% YoY due to the Covid-19 pandemic and mandatory shutdown. Demand from business and industry sectors fell by 10.4% and 5.4% YoY, respectively, because of the harsh economic effects of social distancing measures, temporary shuttering of department stores, hotels, restaurants, and entertainment sites, and closures in most sector in the economy. Against this overall decline, the shutdown meant that a large proportion of the workforce had to work from home temporarily, and this, together with steadily rising average temperatures, had boosted household electricity demand by 7.0% YoY.

Similarly, power output from generation plants fell by 1.7% YoY in 5M20. Power generated by EGAT (which contributes 34.1% of all electricity supplied to the grid) increased by 5.5% YoY. For private-sector generators, IPPs (22.3% of the total) saw production decline by 19.3% YoY, while SPPs and VSPPs (combined contribution of 31.5%) increased their production by 3.1% and 2.2% YoY, respectively. But with the government easing lockdown measures since May, demand from industry and business sectors will again pick up again the rest of the year.

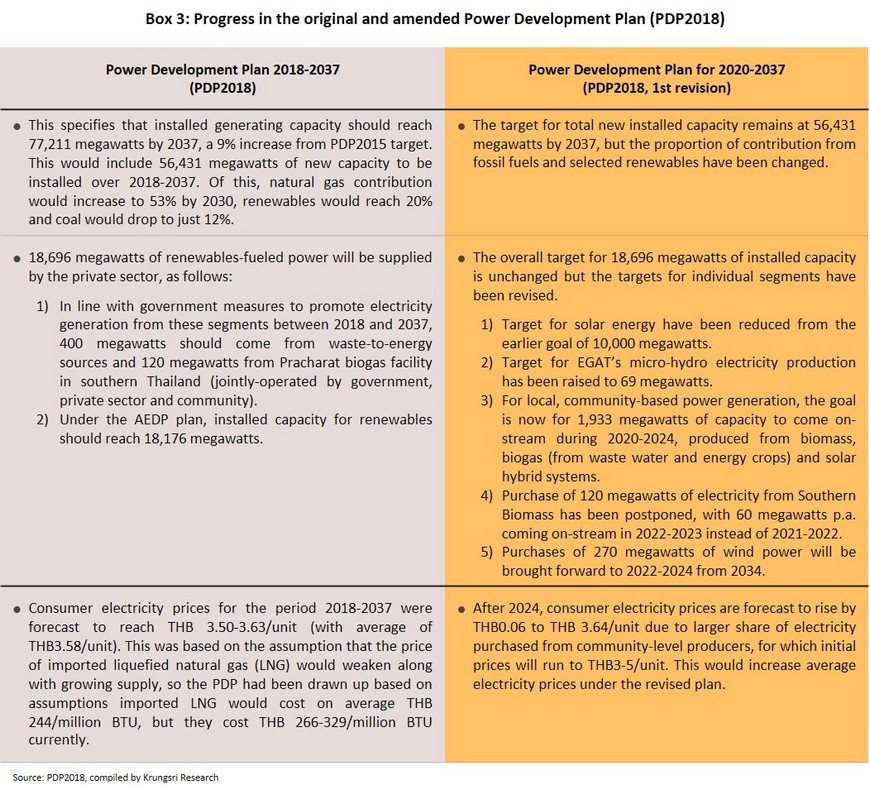

The first revision for the 2018 Power Development Plan for 2020-2037 is currently awaiting cabinet approval (Box 3), and unfortunately this has delayed the implementation of some renewables projects, especially community power-generating ‘quick win’ schemes which will now be selling to the grid from 3Q20 instead of 1Q20.

Outlook

For full-year 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic and the national lockdown will reduce annual electricity demand by 2.0-3.0% (compared with +2.7% in 2019). This would be principally driven by stalled economic activity in both services and manufacturing sectors due to the lockdown, although that has been partially offset by higher demand from the household sector as employees had been encouraged to work from home. Unfortunately, the long-term outcome of this uncertainty within the sector was to to postpone investments in private-sector renewables projects until 2021.

In 2021 and 2022, business conditions will improve somewhat for private-sector power generators, premised on assured demand and government support to invest more in the sector, as specified in the PDP.

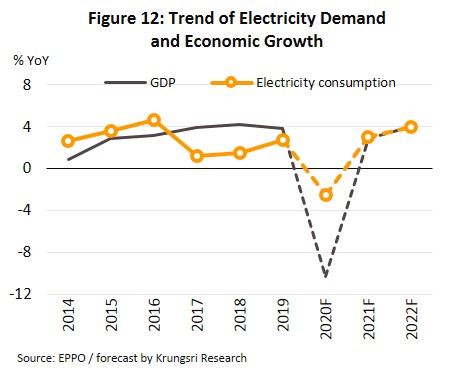

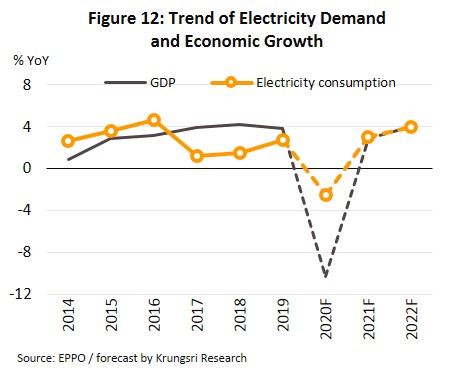

- Total domestic electricity consumption is forecast to grow by an average of 3.0-4.0% p.a. over the next 2 years[6] as the economy slowly returns to growth mode (Figure 12) and lift demand for electricity in both the business and industrial sectors. However, demand growth in the household sector will slow down as employees start returning to work in offices and working conditions normalize.

- Power Development Plan for 2020-2037 (PDP2018, 1st revision) encourages the expansion of installed capacity and investment in new power stations in the near future with the following goals.

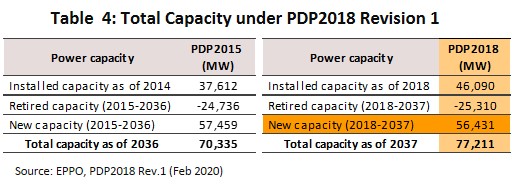

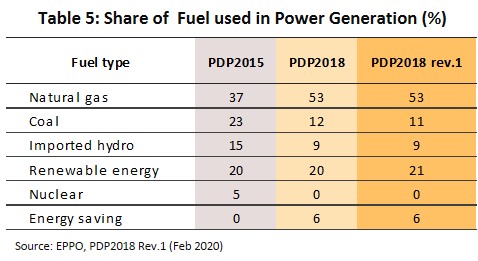

- The revised PDP2018 targets 56,431 megawatts of installed capacity by 2037 (Table 4). Although natural gas contribution will be unchanged at 53%, electricity generated from renewables will play a larger role with their contribution rising to 21% of generation mix, while coal-fueled generation mix will fall to just 11% (Table 5).

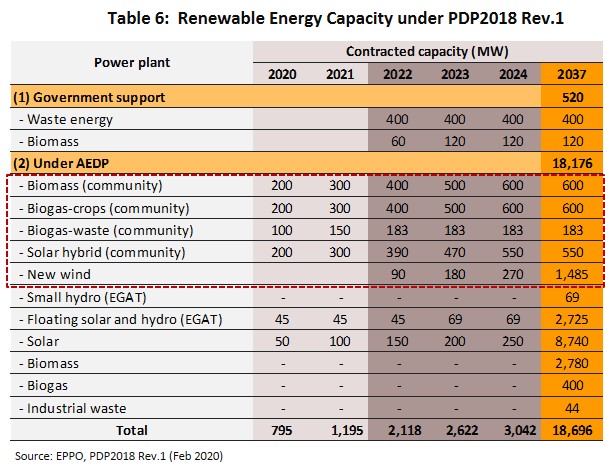

- The overall target for the purchase of renewables-fueled electricity is unchanged at 18,696 megawatts, comprising: (i) 400 megawatts from waste-to-energy sources and 120 megawatts from government-run biogas facilities in the south of Thailand (coming online at a rate of 60 megawatts/year in 2022-2024), following government measures to promote electricity generation in these segments between 2018 and 2037; and (ii) 18,176 megawatts from renewables projects per the AEDP, though this now includes 1,933 megawatts of new capacity from local, community-based power generation capacity (from biomass, biogas, waste water and energy crops, and solar hybrid systems) in 2020-2024, and 270 megawatts of wind power which will come on-stream in 2022-2024 (Table 6).

- From 2024, consumer electricity tariffs are expected to average THB3.64/unit, up from THB 3.5[8]unit specified in the earlier version of the plan. This is partly due to buying electricity from community-level producers, for which the government has set initial purchase price at THB 3-5/unit.

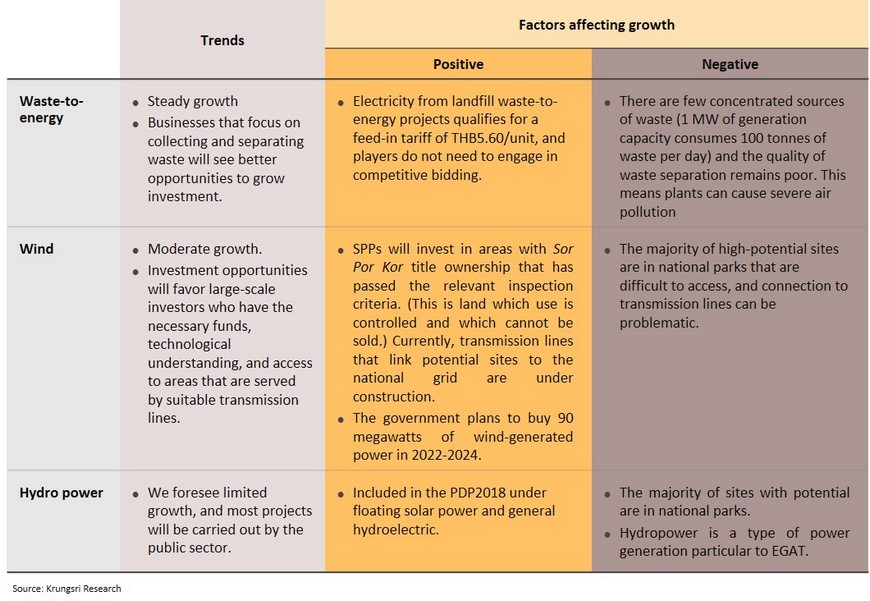

The above factors will encourage more investment in the three types of power generation projects, as described below.

- For IPPs, there should be competitive bidding within the next 3-5 years. The government will call for bids for about 700 megawatts of capacity in the west of the country in 2021-2022, to replace gas-fired power plants that will gradually reach the end of their supply contracts and lose access to the grid over 2025-2027. This will affect 8,300 megawatts of installed capacity .

- SPPs would increase installed generation capacity and investment in new power stations, especially natural gas-fueled cogeneration power plants which contracts will expire in 2019-2025[7]. SPPs will also invest in renewables in the form of mixed-fuel power generation, or ‘SPP hybrid firms’, which Thai authorities are increasingly supporting. These power suppliers will now be paid for the next 20 years at a feed-in tariff rate of THB 3.69/unit, up from the THB3.66/unit received in 2019.

- VSPPs are expected to step up investment from 2021, especially in solar rooftop, biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy electricity projects because the volume of electricity supplied to the grid by these segments is still short of government targets. This presents an investment opportunity. And, in line with the PDP and AEDP, the government is supporting these segments by increasing purchases of electricity from these suppliers, while the players are also generally competitive in terms of access to raw materials and costs. For players active in wind power, the government plans to buy-in another 270 megawatts of electricity from wind farms over 2022-2024, by which time EGAT should have completed its work on the high-voltage power lines in the Northeast and South, which are required to connect commercial wind farms to the grid.

Krungsri Research’s view:

Players will see revenue growth slow in 2020 in line with the worsening economic outlook. But in 2021 and 2022, domestic economic conditions are forecast to improve and GDP will register healthy growth again. And this will benefit larger power companies. However, costs would rise, especially for renewables projects, which could cap earnings growth at moderate levels.

- IPPs: For 2021-2022, the forecast is for better revenue growth driven by sales to the domestic market and higher returns from overseas investments. There will be more investment in renewables, encouraged by the revised PDP2018 plan for 2020-2037, which allows competitive bidding for only 700 megawatts of generation capacity to replace gas-fired power stations in 2021-2022 (but this might be postponed because of the Covid-19 outbreak). In addition, large-scale power stations may not be environmental-friendly and might provoke opposition from local communities. Overseas, there will be more investments in new natural gas- and coal-fired power stations and renewables (especially solar and wind) in Myanmar, Laos PDR, Indonesia, the Philippines, Australia and Japan.

- SPPs: Over the next three years, revenue will be sufficient for SPP’s to be self-supporting. SPPs can benefit from investing in: (i) cogeneration natural gas power stations that will reach the end of their contracts over 2019-2025 but which will still be able to supply power to industrial parks and estates; (ii) new renewables projects in the form of ‘SPP hybrid firms’, which will enjoy fuel costs that are lower than consumer prices for electricity (costs about THB 1.81/unit whereas consumer prices are about THB 3.60/unit); and (iii) new electricity production in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), where demand will rise in the near future.

- VSPPs: Revenue will rise steadily driven by solid demand but investment opportunities may be restricted to producers that are beneficiaries of government support measures laid out in the revised PDP and AEDP, notably private rooftop solar, biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy projects from which the government plans to increase electricity purchases. New entrants to the market that are investing in biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy projects may experience difficulty sourcing for input, while government purchases of electricity from new wind-powered projects should start in 2022-2024.

Overall, competition in the sector has grown more intense, especially for renewables, because existing operators have been expanding generation capacity and there have been several new entrants. Notably, there is increasing influence from players with huge financial and technological strengths, such as IPPs and SPPs that have a background in engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) because they have the necessary expertise to install electrical systems, or those that manufacture solar equipment. These operators have started to supply renewable power to the grid.

[1] In the past, this was a 15-year framework, which was then extended to 20 years. At that time, the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) undertook planning in cooperation with the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) but planning for 2018-2037 is within the remit of the PDP and the AEDP.

[2] The net price for purchases of electricity is set at a rate that reflects the real costs of production of different types of power over the course of the 20-25 years for which contracts to supply run. These are allotted through a process of competitive bidding organized by the Office of Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC).

[3] Under this system, an additional payment is added to the cost of electricity sold to the grid for a period of supply running for 7 years. Admission to the system is on a first-come, first-served basis.

[4] Reserves are in deposits that have already been explored. Plans, which have been approved in accordance with national laws, have been put in place for the exploitation of these reserves and extracting this gas should be commercially viable.

[5] Including off grid power generation, exclude large hydro power 2,906 MW

[6] This is on the assumption that (i) energy saving measures reduce demand by an average of 1 billion units annually, and (ii) independent power suppliers, which produce electricity for their own use or who bypass EGAT and supply electricity directly to consumers, supply some portion of this, though information is only available on suppliers generating over 1 megawatt of power.

[7] SPPs are required to construct new power plants to sell electricity to EGAT, while selling prices are based on types of electricity generated from natural gas and coal.

.webp.aspx)