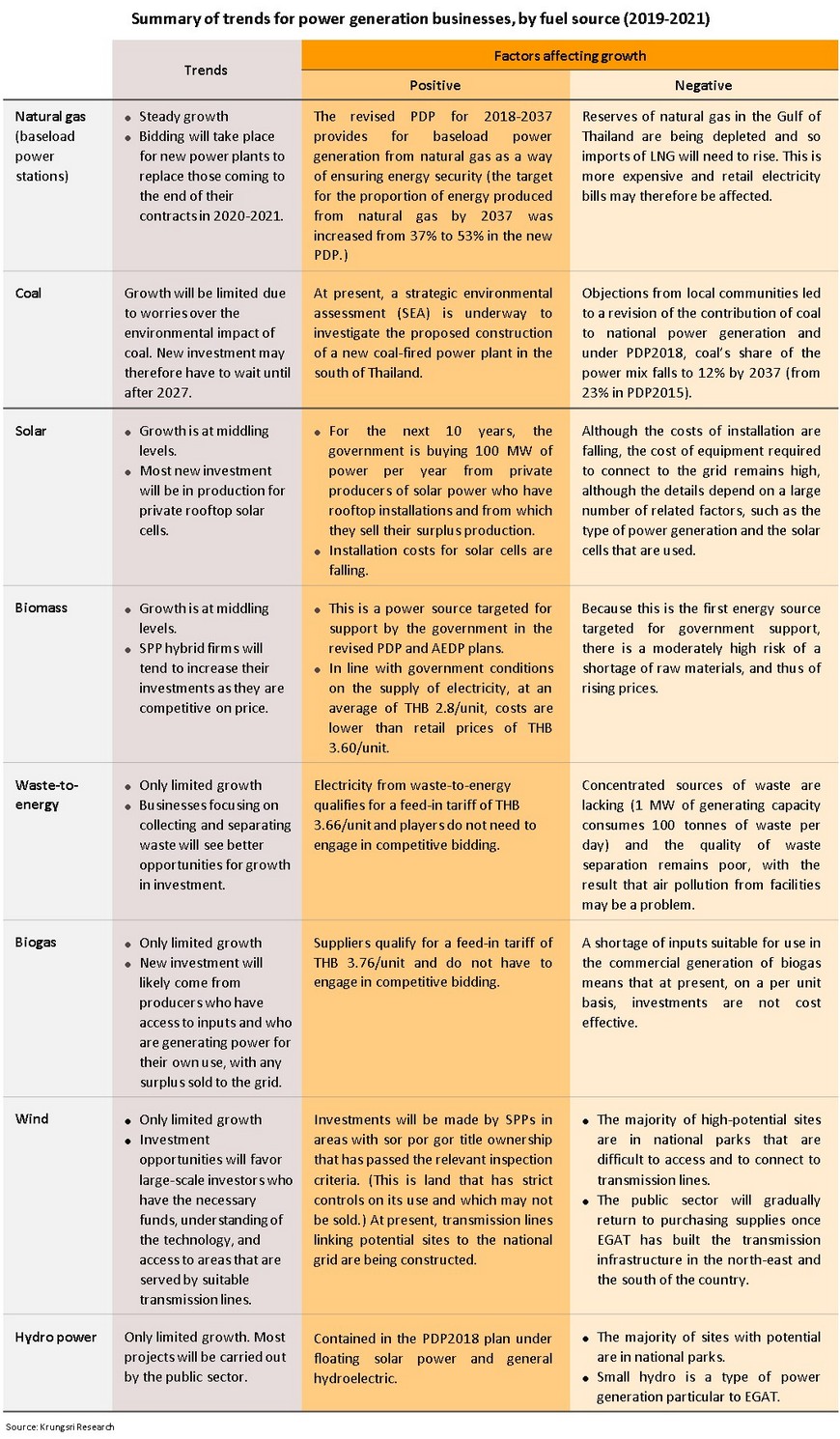

Private power generation business will see growth in business through 2019-2021, with electricity demand forecast to rise by an average of 3-3.5% per year. In addition to this strong and reliable demand, on the supply side, players will benefit from government support for investment as specified in the Power Development Plan (PDP), which lays out a regional roadmap for the sector and continues to promotes renewable sources of energy.

Power plants that are competitive in terms of their costs and their access to fuel sources will be the most likely to gain from ongoing investment, and among this group, solar power ranks very highly as the way has now been opened for rooftop production of solar power by the public, with, from 2019, the government promising to buy in 100 megawatts of this per year over the next decade. Other high-potential electricity producers include those generating power from biomass, waste-to-energy schemes, and biogas producers. For those looking to make new investments in wind and hydro power, it may be necessary to wait until after 2021, by which time, the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) should have installed the necessary new high-voltage transmission lines required to connect to these more remote sites.

Overview

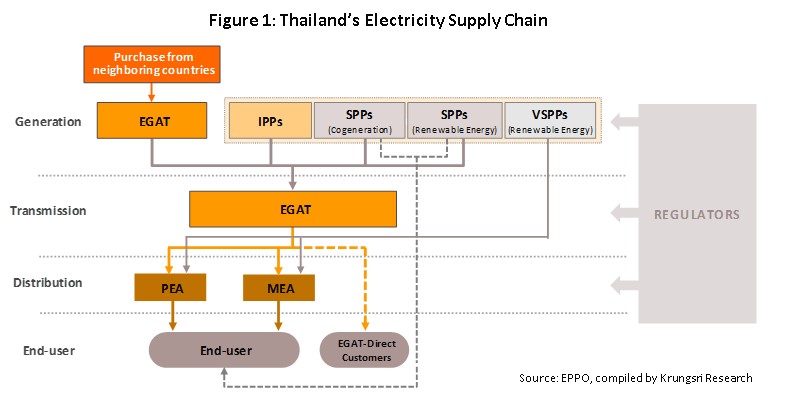

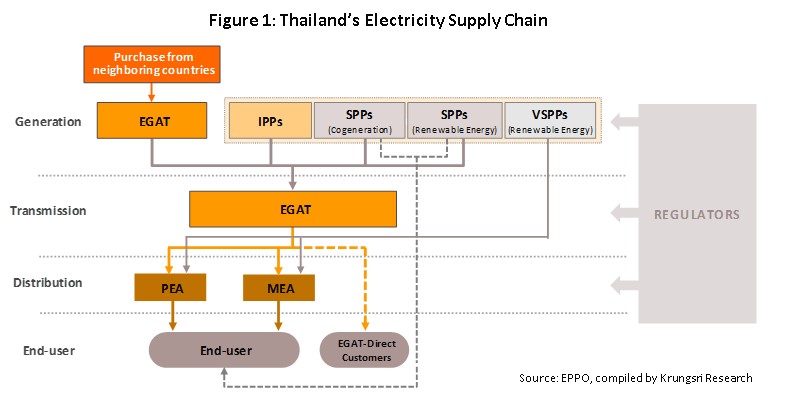

Thai power generation is organized so that state bodies are the sole buyers of power on the national grid, the sector thus being structured in line with the enhanced single buyer model. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) is both a producer and, by purchasing power from private-sector ‘independent power producers’ (IPPs) and ‘small power producers’ (SPPs), a buyer of electricity, as well as exercising a monopoly on the distribution of electricity in the country. In addition to EGAT, the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) and the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) have responsibility for distributing power, as well as buying in electricity from ‘very small power producers’ (VSPPs) (Figure 1).

The most important features of the Thai electricity generation system are that: (i) Unlike other forms of goods, electricity cannot be stored and must be distributed to users or consumers immediately through a transmission and distribution system. (ii) Production capacity expansion cannot be achieved in the short term, as constructing power stations takes 5-7 years, though the exact length of time will depend on the type of power plants being built. Because of this, power generation needs to be subject to national planning through the setting out of a power development plan (PDP), which will ensure that future supplies of electricity are sufficient to meet demand. (iii) State bodies thus have a major role to play in managing generation and distribution, as well as in setting prices and planning for investment to increase supply to the national grid.

Growth in demand for electricity will depend on the following factors.

- Total domestic demand for electricity which tends to fluctuate with the economic situation: The average rate of growth in demand for electricity is 0.9-1.1 times the rate of growth in GDP. Figures for 2018 show that industry, business, households, and other sectors accounted for 47%, 25%, 24% and 4% of electricity consumed in Thailand, respectively.

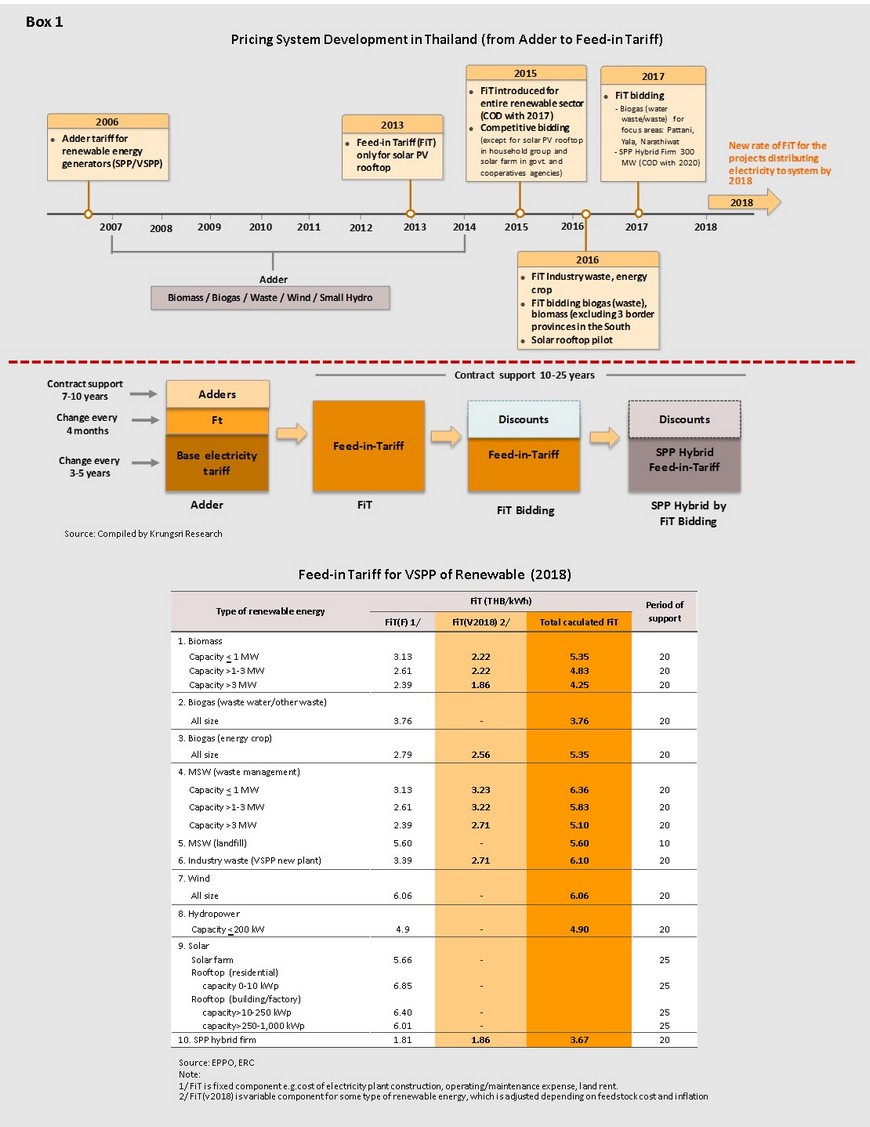

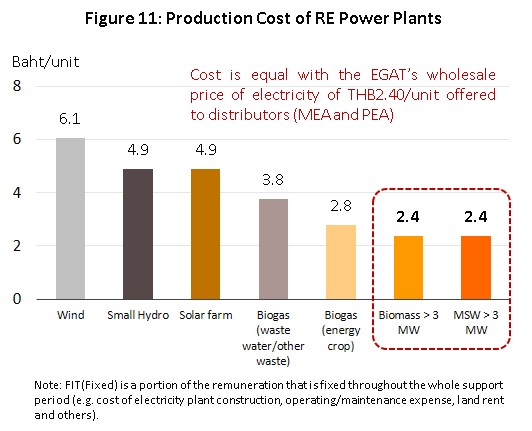

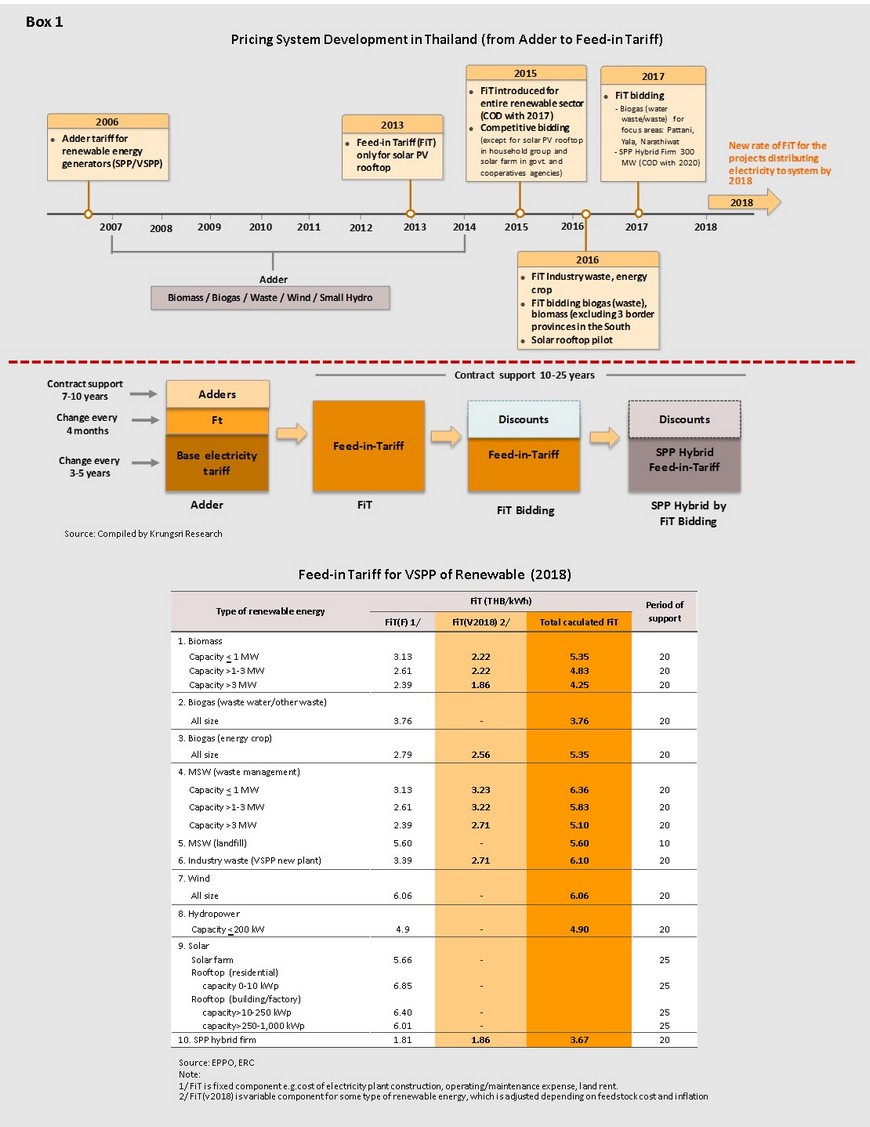

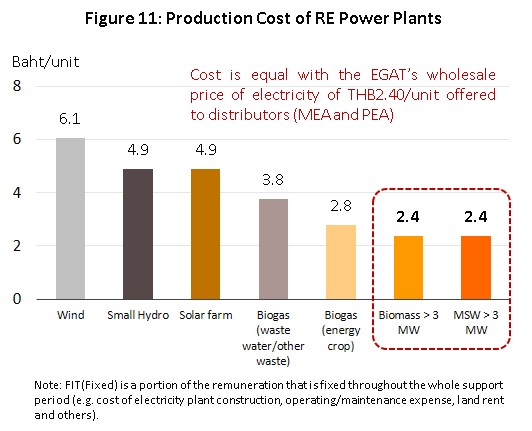

- Government policy: (i) The Power Development Plan (PDP) and the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) specify the desired total generating capacity for each type of power plant[1]. (ii) Policy is also set with regard to the price paid for purchases of renewable sources (because producing power from renewables incurs higher costs than electricity produced from fossil fuels, i.e. natural gas, coal, and oil) and this is now used in determining the feed-in tariff[2] (FiT), whereas in the past, the adder system was used to calculate payments[3] (Box 1). (iii) The government also plans for the expansion of the power distribution network, which is required to meet increasing production, especially that from renewable sources of power.

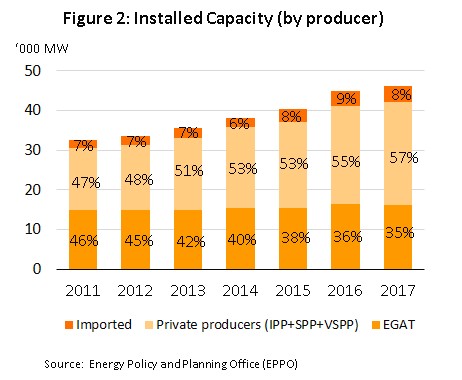

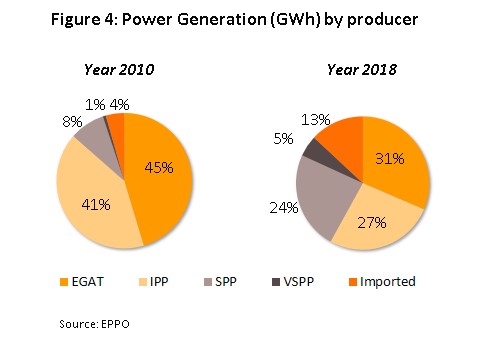

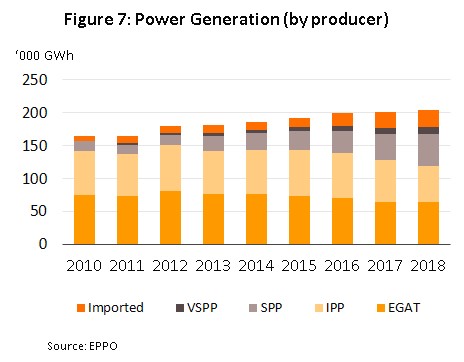

Private power producers have a steadily growing importance within the sector (Figure 2). In 2017, the private sector controlled 57% of power generating capacity (or 46,090 megawatts), split between IPPs (33% of total power supply) and SPPs and VSPPs (24%). The balance (43%) is made up by EGAT, which both produces electricity itself and is responsible for buying in power from neighboring countries.

Fuels used to generate electricity can be split into the two main groups of:

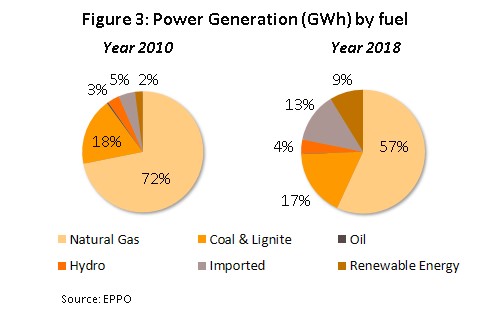

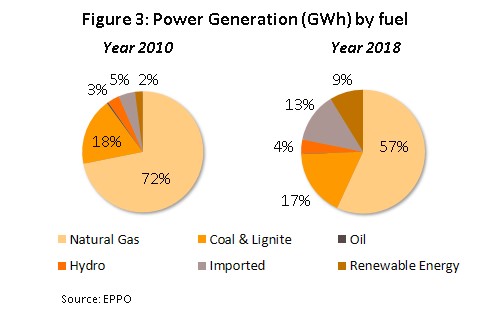

1) Fossil fuels (i.e. natural gas and coal/lignite) provide the bulk of Thai electricity, and Thailand relies in particular on natural gas, with this being used to generate 57% of the electricity used in the country. Natural gas is followed in importance by coal, which provides another 17% of Thailand’s electricity (Figure 3).

2) Renewables are used to generate around 9% of Thailand’s electricity. Examples include biomass (from agricultural products), biogas (from pig manure, waste water from the processing of agricultural products, and crops grown specifically for the purpose), waste-to-energy (from community or industrial waste), solar, wind and hydroelectric power.

At present, proven reserves (P1) of natural gas in the Gulf of Thailand come to 6.4 trn cubic feet[4], while Thai annual consumption runs to 1.3 trn cubic feet (source: Department of Mineral Fuels, December 2018) and so current proven reserves of natural gas are sufficient for only another 5-6 years. Thailand will thus soon have to import gas from abroad, with this likely to come especially from Myanmar, and in light of this, the PDP has emphasized the increased use of renewables in power generation. The result of this has then been to lift the proportion of renewables in the national power-generating mix from 2% in 2010 to 9% by 2018.

Private power producers can be divided into three main groups.

- Independent Power Producers (IPPs)

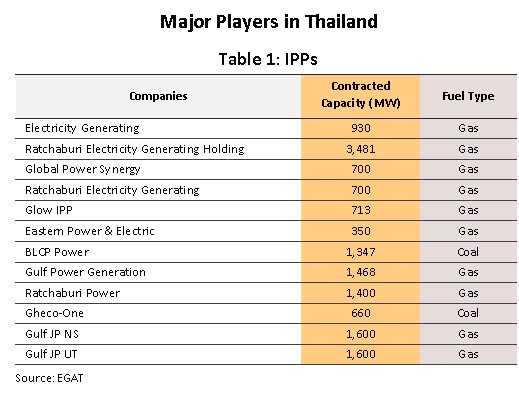

- Total installed capacity to qualify as an IPP: Over 90 megawatts. These producers depend principally on the use of natural gas and coal to fire their power plants. The most important players are: Electricity Generating, Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holding, Global Power Synergy, Ratchaburi Electricity Generating, Glow IPP, Eastern Power & Electric, BLCP Power, Gulf Power Generation, Ratchaburi Power, Gheco-One, Gulf JP NS and Gulf JP UT.

- Factors affecting turnover: For players in this group, there is only a slight chance of seeing low levels of income because they agree long-term contracts with EGAT for the supply of electricity. Income is generated from two sources: (i) directly from the quantity of electricity supplied to the grid to meet demand, and (ii) a guaranteed minimum income (the so-called ‘minimum take’) that is specified in the contract with EGAT. Income for these players thus depends on the total national consumption of electricity, although businesses also receive income from investments in power-generating facilities in countries including Myanmar, Laos PDR, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia.

- Small Power Producers (SPP)

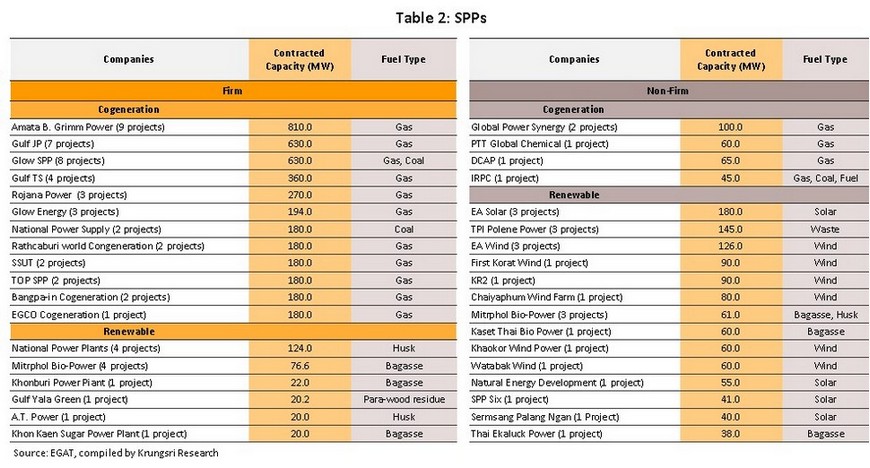

- Total installed capacity to qualify as an SPP: 10-90 megawatts. SPPs typically generate power from natural gas, coal, oil and renewables, and sell electricity to EGAT or to industrial consumers that are located near to the SPP’s power station. SPPs can be split into (i) ‘firm’-type SPPs, which agree 25-year contracts to supply power to EGAT and which generally generate power from burning natural gas or coal, and (ii) ‘non-firm’ SPPs, which agree 5-year contracts (extendable in 5-year increments) and which usually use renewable sources of energy, such as solar, wind and biomass.

- Factors affecting turnover: SPPs have two sources of income. (i) Income from contracts agreed with EGAT for the supply of electricity run for 20-25 years and, like IPP contracts, these have a minimum revenue guaranteed so SPPs face only low levels of risk of seeing weak turnover. (ii) Revenue may also be generated from supplying electricity to industrial consumers that are local to the power plants, but the extent of this income will tend to fluctuate according to the economic situation and the particular business conditions for the SPP’s customers.

- Very Small Power Producers (VSPPs)

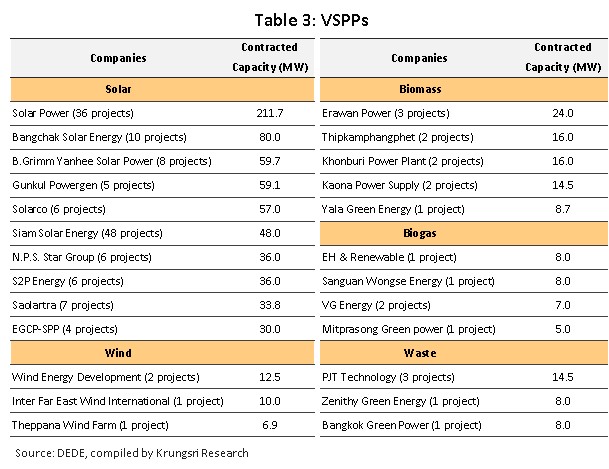

- Total installed capacity to qualify as a VSPP: Under 10 megawatts. VSPPs generate electricity from renewables (including solar, wind, hydro, biomass, biogas, and waste) for their own use, and selling on surplus production to MEA or PEA at rates determined by the feed-in tariff (FiT) for their particular generating technology and circumstances for as long as the project runs (Box 1). The majority of VSPPs selling electricity sourced from renewables are building contractors or engineers involved with designing and installing renewable electricity systems or manufacturers of solar cells and related equipment, as these organizations have the necessary expertise to set up and maintain these types of systems.

- Factors affecting turnover: Income from VSPPs depends on (i) costs arising from the required construction work, from buying and installing equipment, and from sourcing and purchasing the materials used in power generation, and (ii) revenue arising from the sale of power to the grid. For players generating power from natural sources (i.e. solar, wind or hydro power), operations are likely to run at a loss for the first 1-2 years due to high construction costs, though following this initial period, the situation will improve as income from the sale of electricity begins to support the business. However, for those producing electricity from biomass, biogas and waste, fluctuating access to and prices for raw materials will likely cause income to be similarly uncertain.

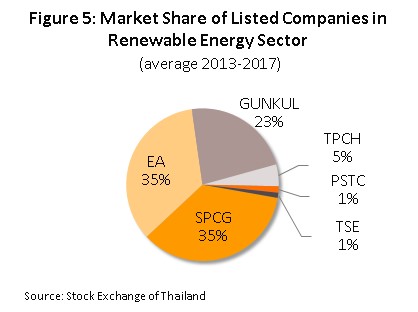

In the five years between 2013 and 2018, the proportion of electricity produced by SPPs and VSPPs increased sharply, with the contribution to the energy mix of VSPPs, which produce power from renewables, growing particularly strongly as a result of the government following the plans laid out in the AEDP and so increasing purchases from this group of suppliers. Indeed, by 2018, the proportion of electricity supplied by VSPPs had risen to 5.0% of all electricity sold on the grid from the 2010 level of just 1% (Figure 4). Important players in the energy sector that are listed on the stock exchange and that produce power from renewables include Energy Absolute (EA) (solar and wind), SPCG (solar), Gunkul (solar, wind and biomass), TPC Power Holdings (TPCH) (biomass) and Thai Solar Energy (TSE) (solar) (Figure 5).

Situation

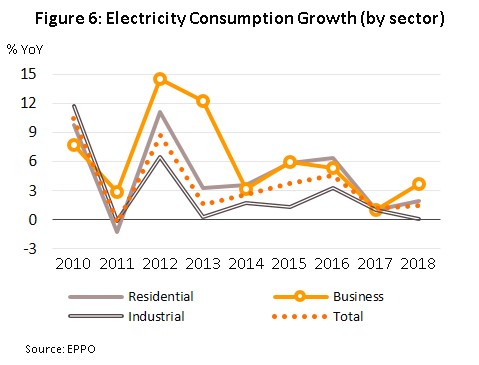

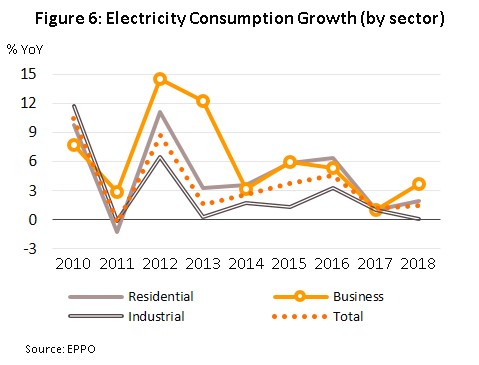

Total demand for electricity in 2018 came to 187,832 gigawatt hours (GWh). For the year, annual growth in demand rose to 1.5% YoY, up from 2017’s figure of 1.2%. This increase was driven by a recovery in Thai economy and an improving tourism sector. The government efforts to encourage energy-saving restrain increases somewhat. Thus, peak demand hit 28,338 megawatts (MW) in April, which was slightly lower than the peak demand in 2016 (29,619 MW). In terms of sources of demand, consumption by business and industry increased by 1.3% YoY in 2018, while household demand rose at the higher rate of 1.9% YoY (Figure 6).)

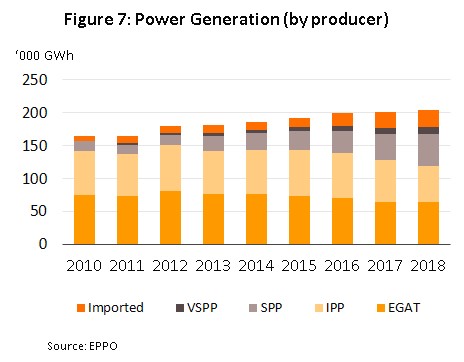

Electricity generation came to a total of 204,428 GWh in 2018, which represented growth of 1.6% YoY, double the 0.8% growth seen in 2017. Following a -10.0% reduction in 2017, the amount of electricity supplied to the grid by EGAT (31% of all electricity supplied) rose by 0.8%. IPPs (supplying 27% of Thailand’s electricity) saw their share of the mix shrink from the 2017 figure by -14.7% YoY. The situation for SPPs and VSPPs (a 29% combined share) ran in the opposite direction as they expanded their contributions by 21.7% YoY and 12.9% YoY, respectively (Figure 7), driven by a push over the past few years to buy electricity generated from renewables and the signing of agreements between EGAT and SPPs and VSPPs to supply this. Thus, in 2018, the proportion of energy from renewables supplied to the grid rose by 20.0% YoY, while use of natural gas (the sector’s primary source of energy) shrank by -4.0% YoY. Electricity generated from coal and electricity imported from neighboring countries rose by respectively 0.2% YoY and 9.2% YoY.

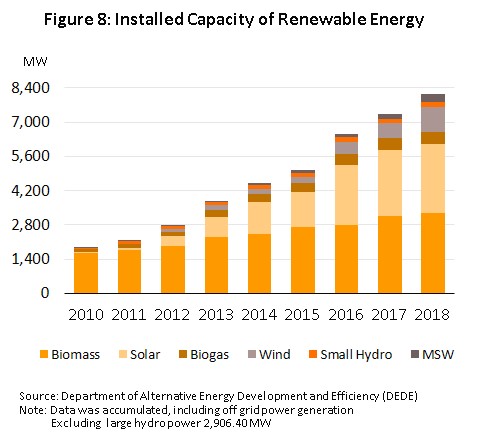

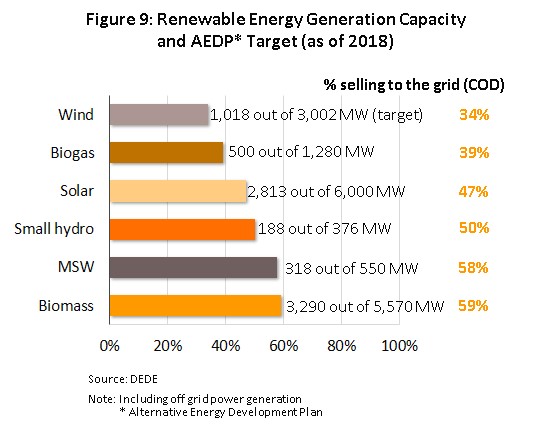

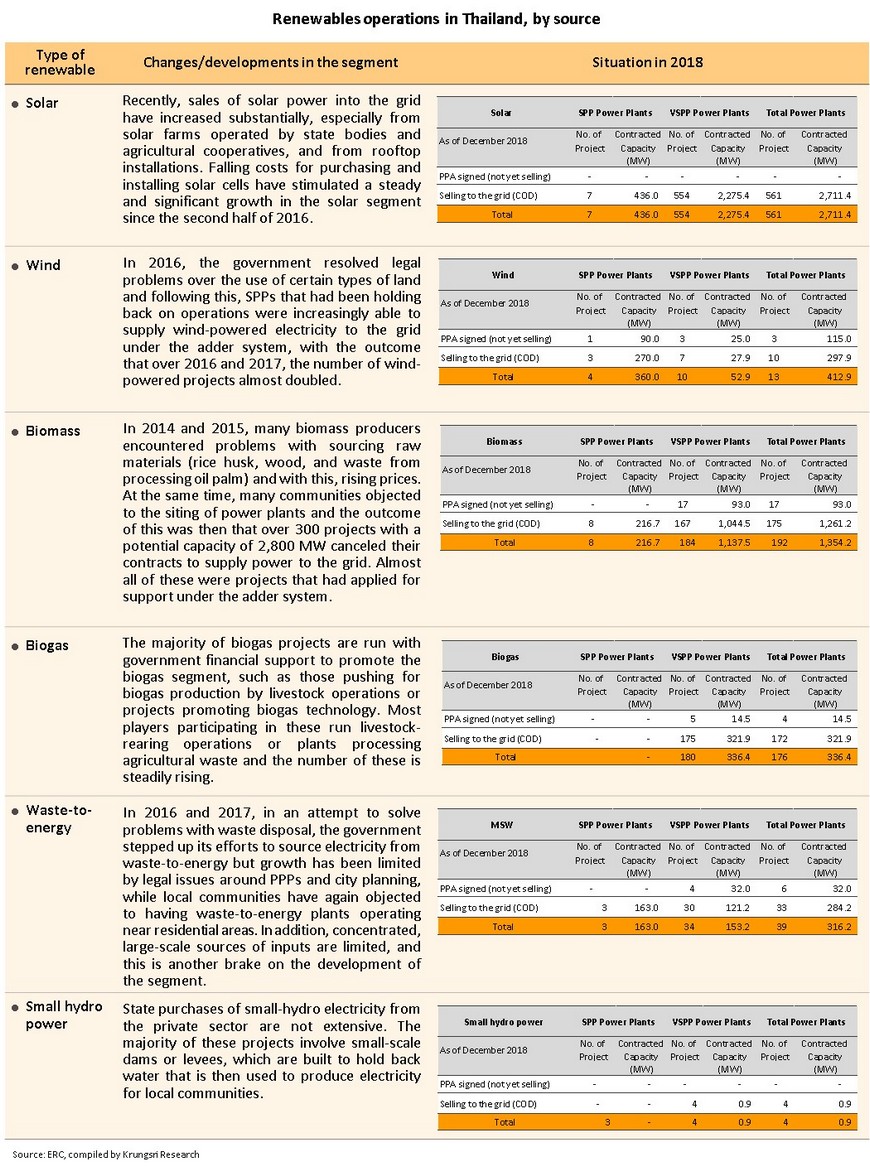

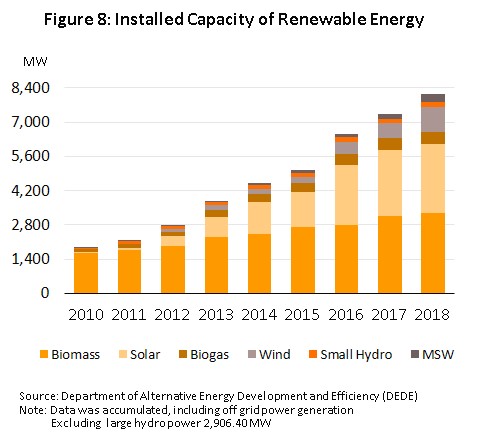

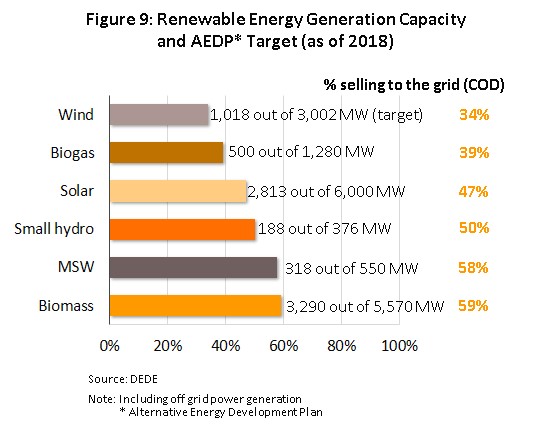

A total of 8,127 MW[5]of renewable energy were sold to the grid in 2018 by companies under contract to supply to the state electricity distributor, and over the year, the total installed capacity of renewables rose 10.8% from the capacity at the end of 2017 (Figure 8). Waste-to-energy and wind power saw the fastest growth, with installed capacity of these two sources rising by 66.5% and 62.1% thanks to a 2016 decision by the government to try to expand the number of sources of waste-to-energy electricity as a way of solving problems with excess rubbish, while legal problems with land ownership and usage have now been overcome, making the setting up of wind farms easier. The outcome of this has then been to make it more straightforward for SPPs producing electricity from these two sources to sell power to EGAT. However, the AEDP (2015-2036) has set a target of 16,788 MW of renewables capacity to be installed by 2036 and at present, the national power system is only 48.5% of the way there. So far, power generation from biomass has made the greatest progress towards its goal; this is for 5,570 MW of installed capacity, and the target for biomass generation is now 59% complete. In order of progress towards their goals, biomass is followed by waste-to-energy, micro-hydro, solar, biogas and wind (Figure 9).

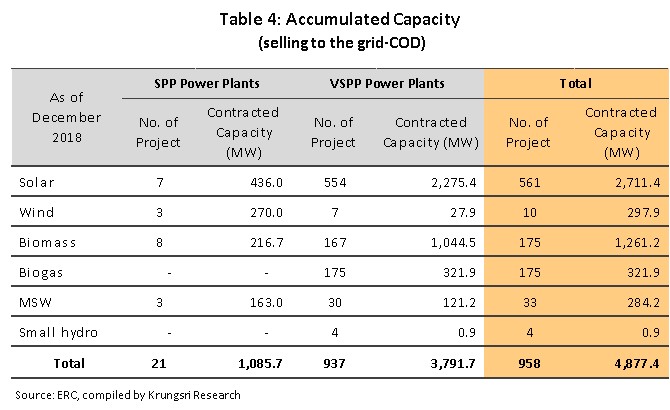

In terms of the situation of renewables energy business, in 2018, there was a total of 937 SPP and VSPP projects (including projects that received support under the adder and FiT systems) selling electricity to the national grid and these had a contracted capacity of 4,877 MW (Table 4). Solar power had the largest number of projects, while biomass generation has begun to experience problems over competition for inputs and from local communities objecting to the siting of biomass electricity generating plants nearby and this has led to a large number of operators cancelling their contracts to supply EGAT. In addition, some players are waiting to transition from the adder to the FiT system (details for different types of power generation are given on page 8).

Outlook

Through 2019-2021, power generation businesses is expected see steady growth, underpinned by both solid demand and government support for investment in supply.

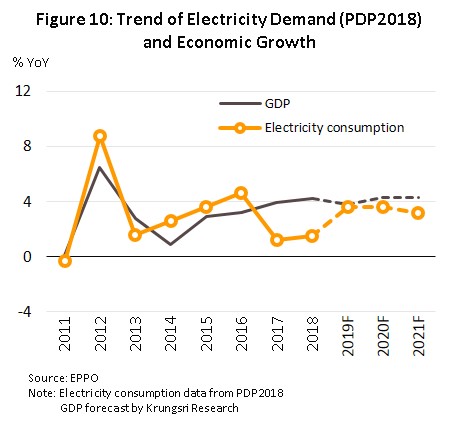

Domestic demand for electricity will grow in line with the state of the economy, while steadily growing investment in business and industry will also feed rising consumption of power; the PDP2018 plan forecasts demand increasing by 3.6% in 2019 and 2020 and then by 3.2% in 2021, on the assumption that GDP grows by an average of 3.8% per year (Figure 10).

The rolling out of the 2018-2037 Power Development Plan (PDP2018) and the extending of SPP cogeneration contracts is helping to expand generating capacity and to raise investment in new power plants in the near term. Important features of the plan are given below.

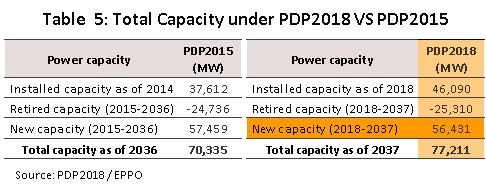

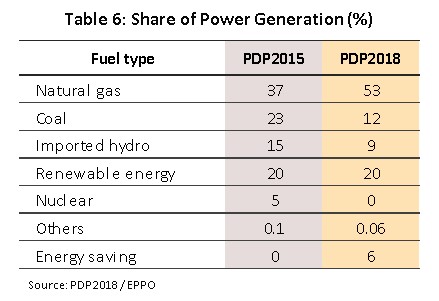

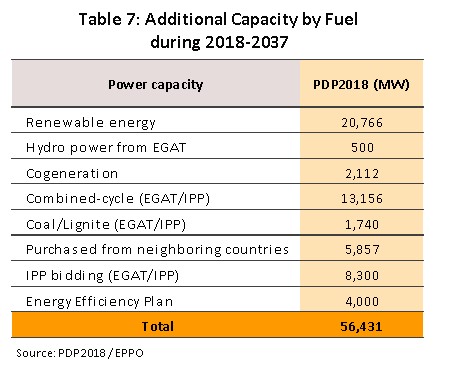

- The PDP2018 plan specifies a target of 77,211 MW of installed capacity by 2037, a 9% increase on the target set in PDP2015 and this will require 56,431 MW of new capacity to be installed over the period 2018-2037 (see Table 5 for details). The 2018 plan also increases the contribution of natural gas to the energy mix and this rises to a 53% share of all electricity generated by 2037, while under the new PDP, the share of renewables remains at 20% and coal’s contribution falls to 12% (Table 6). To meet these goals, new power plants or replacements for old power plants will be built directly by EGAT, though IPPs will also be able to engage in competitive bidding for contracts (Table 7).

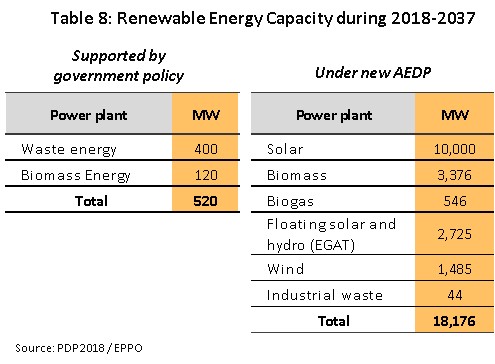

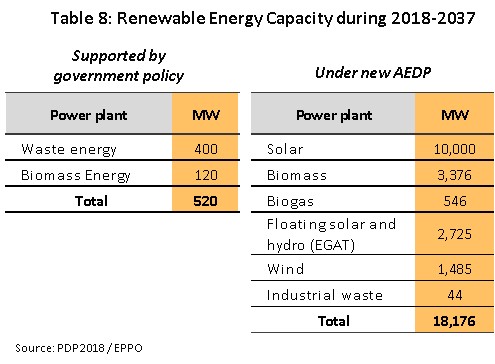

- Power supplied to the grid from private-sector renewables can be split between: (i) power plants that will receive government support through 2018-2037, which have a combined generating capacity of 520 MW (400 MW from waste-to-energy and 120 MW from biomass plants), and (ii) renewables power plants established according to the AEDP, which will have a generating capacity of 18,176 MW (Table 8).

- It is forecast that for 2018-2037, the retail electricity bills will be in the range THB 3.50-3.63/unit, with an average cost of THB 3.58/unit. This is based on the expectation that the price of imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) will tend to fall on an increase in supply and in fact, the average price of imported LNG that was used in the PDP forecasts was THB 244/MMBTU, compared to the current average price of THB 266-329/MMBTU.[6]

- The National Energy Policy Office (NEPO) has agreed to extend contracts for SPP cogenerating plants that expire during the period 2016-2025. This affects 25 operations with a generating capacity of 2,974.2 MW, split between 20 producers using natural gas as an energy source, and 5 coal-based operators. These power plants will continue to generate electricity from the sources specified in their original contracts and they will be paid in accordance with the type of fuel used; natural gas-powered supplies will be paid THB 2.80/unit while coal-based suppliers will receive THB 2.54/unit.

The factors outlined above will support increased investment in the three classes of power generators as follows.

- For independent power producers (IPPs), competitive bidding should take place within the next 3-5 years for replacements to large-scale power plants that use natural gas and which will gradually reach the end of their supply contracts and so lose access to the grid in the period 2025-2027. This will affect a total of 8,300 MW of production. Meanwhile, some 700 MW of capacity will come up for auction annually in the west of the country in 2021-2022.

- Small power producers (SPPs) will tend to increase their installed generating capacity and their investments in new power plants, especially for natural gas-fueled cogenerating power plants that will see their contracts expire in the years 2016-2025. These SPPs will continue generating power and/or be sites for the construction of new power plants, producing electricity for use by industrial estates and parks. SPPs will also invest in renewables in the form of mixed-fuel power generation, or ‘SPP hybrid firms’, which Thai authorities are increasingly supporting. (Purchases of electricity from these suppliers began in October 2017 and 300 MW of supply are being paid a feed-in tariff of THB 3.66/unit, which they will receive for the next 20 years.)

- Investments in renewables will be split between the following:

- Solar power has received the greatest quantity of on-going investment as a result of the liberalization of the rules governing the supply of power from private rooftop solar cells. The authorities will buy 100 MW of this supply for the next 10 years (starting in 2019). Renewables that are most competitive in terms of their costs and sources of inputs are, in order of importance, biomass, waste-to-energy and biogas.

- Investors in some renewables (e.g. wind and hydro) will have to wait as some of the sites with the greatest potential are in national parks and permission to build and access are both problematic. Opportunities for investment should, though, improve after 2021 as by then, EGAT are expected to have built the necessary transmission lines.

However, competition is also likely to strengthen within the sector due to the plan to introduce competitive bidding for private sector suppliers and the requirement that the costs of producing electricity should not be higher than the per-unit retail prices given in PDP2018, which were set at THB 3.50-3.63/unit (or an average of THB 3.58/unit). It is thus expected those IPPs and SPPs that are the most competitive on price will increase the scale of their investments, especially in renewables because government planning has already specified that purchases of these should rise in the future.

Krungsri Research’s view

Over the next three years from 2019 to 2021, income for large power generating companies is expected to grow at a fairly good rate on rising domestic demand for electricity. However, the price competition in generating power from renewables will tend to rise and this may hold back income for operators to middling levels, similar to those seen in the last few years.

- Independent power producers (IPPs): The forecast is for income from the supply of electricity to the domestic grid to grow steadily in step with increasing consumption, while income will also be generated from overseas investments. New investments within Thailand will tend increasingly to be made in renewables. As set out in PDP2018, competitive bidding for new natural gas power plants with a capacity of only 700 MW will be organized in 2020 and 2021. Overseas, more investments will be made in new power plants using natural gas, coal and renewables (especially solar and wind) in Myanmar, Laos PDR, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia.

- Small power producers (SPPs): Over the next three years, SPPs will have the opportunity to benefit from investing in: (i) cogenerating natural gas power plants that will steadily reach the end of their contracts in the period 2016-2025 but which will still be able to supply power to industrial parks and estates; (ii) new renewables production in the form of ‘SPP hybrid firms’, which will enjoy fuel costs that are lower than retail electricity prices (currently set at around THB 3.6/unit); and (iii) new power plants in the Eastern Economic Zone (EEC), where demand is set to increase in the near future.

- Very small power producers (VSPPs): Income will steadily rise on solid demand but opportunities for investment may be restricted to producers that are the beneficiaries of the government support laid out in the PDP. In addition, the level of competition within the sector has been raised by both existing operators’ expansion in generating capacity and the entrance of new players to the market. Of particular importance is the increasing influence of players who enjoy financial and technological strengths, such as IPPs and SPPs who have moved into renewables, and players who come from a background in construction engineering, in designing and installing renewables systems or in manufacturing solar equipment but that, because of their expertise, have begun to supply renewable power to the grid.

Opportunities for investment open to VSPPs in 2019-2021 will be concentrated in the production of electricity from private rooftop solar installations, and biomass and waste-to-energy plants because these segments of the electricity production sector are the targets of government support, in accordance with the revised PDP and AEDP, and are competitive in the cost of generation. These segments are also competitive on price, while for wind farms, the public sector will gradually increase purchases and the new investments wait start after 2021 (following the completion of work by EGAT to extend the transmission network in the north east and south of Thailand). As regards electricity generated from biomass, waste and biogas, room for investment may be limited for new players due to a lack of access to raw materials or fuels.

[1]In the past, this was a 15-year framework, which was then extended to 20 years. At that time, the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) undertook planning in cooperation with the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) but planning for 2018-2037 is within the remit of the PDP and the AEDP.

[2]The net price for purchases of electricity is set at a rate that reflects the real costs of production of different types of power over the course of the 20-25 years for which contracts to supply run. These are allotted through a process of competitive bidding organized by the Office of Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC).

[3Under this system, an additional payment is added to the cost of electricity sold to the grid for a period of supply running for 7 years. Admission to the system is on a first-come, first-served basis.

[4]Reserves are in deposits that have already been explored. Plans, which have been approved in accordance with national laws, have been put in place for the exploitation of these reserves and extracting this gas should be commercially viable.

[5]Including off grid power generation, exclude large hydro power 2,906 MW

[6]Source: Japan/Korea Marker (Platts), which specifies a price of USD 8.5-10.5/MMBTU (THB 31.4 against the USD).

.webp.aspx)