Krungsri Research sees the ethanol industry enjoying growth over the next three years that will move in step with rising demand for gasohol, the latter helped by: (i) government support for the biofuel sector and the promotion of gasohol mixes containing a higher proportion of ethanol; (ii) the success of the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines, which will feed into economic recovery and through this, stronger demand for transport fuels; and (iii) a likely expansion in the number of vehicles on the road that can run on gasohol.

Alongside these tailwinds, the industry will have to contend with headwinds arising from the fluctuating price of inputs, which may put pressure on production costs and operators’ margins, as well as from persistent consumer worries over problems arising from the use of gasohol that has a high ethanol content. Over the longer term, increasing sales of hybrids and electric vehicles will weigh on demand for gasoline and with this, the ethanol industry may be negatively affected.

Overview

Ethanol, or ethyl alcohol, is produced either directly from sugary or carbohydrate-rich plants, or from cellulose or hemicellulose-rich plant waste that is left over from other agricultural processes. These inputs, the most common of which are sugarcane, rice, straw, corn and cassava, are fermented to produce 99.5% pure ethanol, which is then generally used as a liquid fuel (directly or mixed with gasoline) or subjected to further industrial processing, such as in the manufacture of food and beverages or pharmaceutical products.

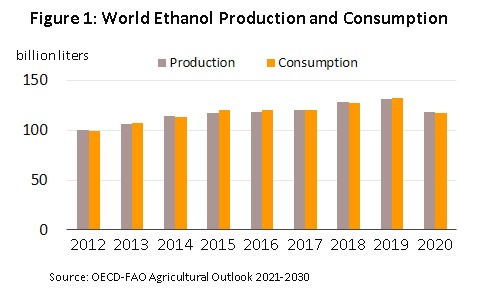

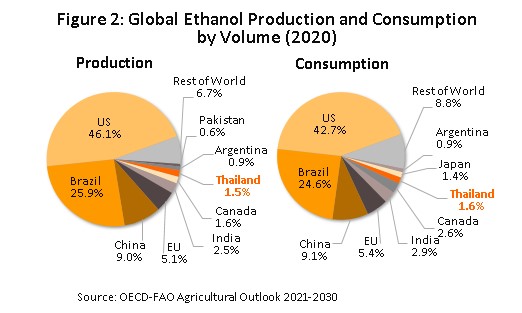

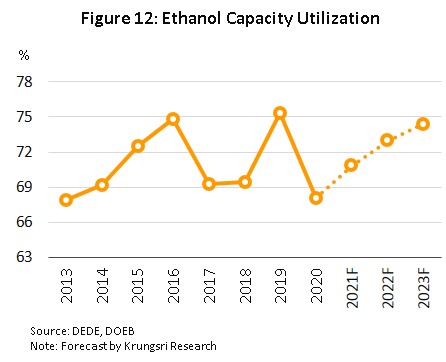

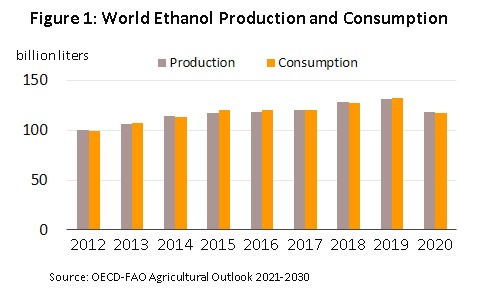

Demand for ethanol was rising steadily in the years before the outbreak of Covid-19. Between 2012 and 2019, annual global demand rose from 100.7 billion to 132.1 billion liters, or average growth of 3.3% per year, while over the same period, yearly output climbed by 3.2% (Figure 1). The largest consumers and producers of ethanol are the US, Brazil and China, which account for around 80% of global production and consumption (Figure 2). These countries generally use corn and sugarcane as their primary inputs.

Thailand sits in 7th place in the world rankings of both ethanol producers and consumers[1]. The majority of domestic ethanol production is used as a transport fuel because it is mixed with benzene to sell as gasohol, movements in the ethanol market are naturally tightly correlated with domestic demand for liquid fuels. However, government policy also exerts a strong influence over the industry because, since 2001, the authorities have required that regular petrol be mixed with 10% ethanol when sold to the public, and this then yields the gasohol 91[2] and 95 that is sold on Thai forecourts. From 2008, 20% (E20) and 85% (E85) ethanol mixes have also been available, and this has helped to stoke steadily stronger demand. However, set against this is the fact that the domestic market for ethanol is tightly regulated and sales to distributors of transport fuels are subject to the provisions of the 2000 Act on sales of oil fuels, while using ethanol in industrial processes is also only possible with the permission of the Liquor Distillery Organization (which operates under the oversight of the Excise Department).

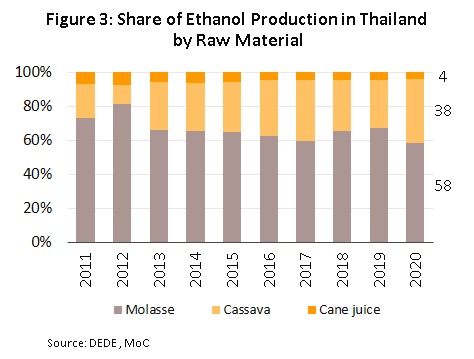

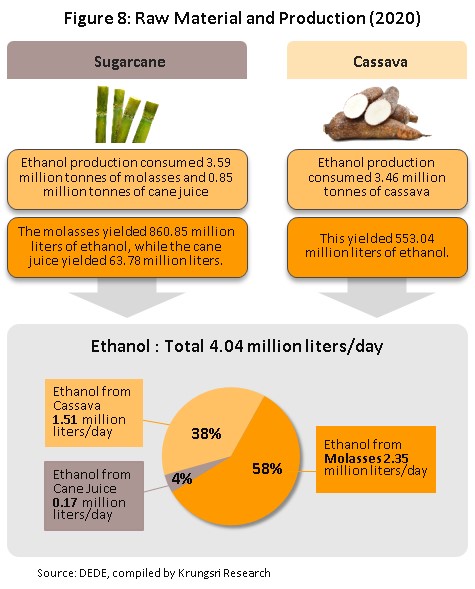

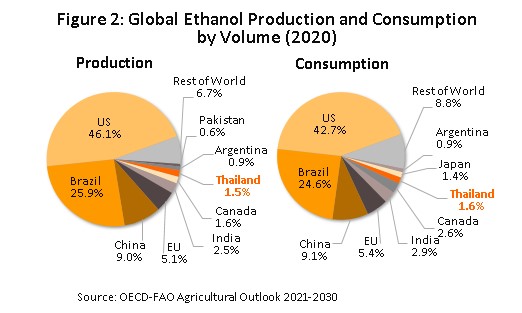

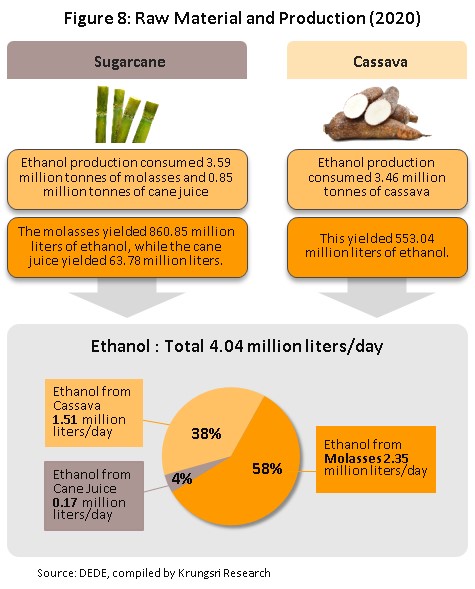

The most important inputs into Thai ethanol production are molasses, cassava and sugarcane, and in 2020, these three accounted for respectively 58%, 38% and 4% of all ethanol produced in the country (Figure 3), though the exact proportions of the different inputs used will vary according to their relative costs at any given moment in time. Within the Thai ethanol industry, molasses-based production has tended to dominate over cassava due to the generally better access to molasses and the fact that the majority of molasses-based ethanol production is undertaken by large players operating ethanol distilleries downstream from their own sugarcane processing plants. By contrast, sometimes the intense competition with other industries for cassava products can lead to problems securing supplies, which can also be affected by government interventions in the market (undertaken to support farmers) and the uncertainty over prices that these generate.

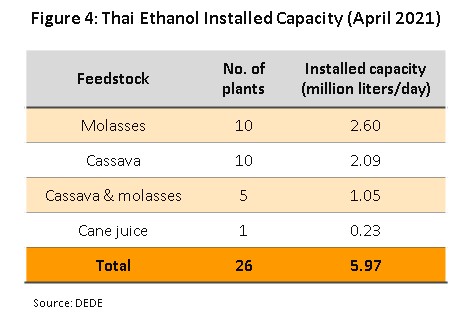

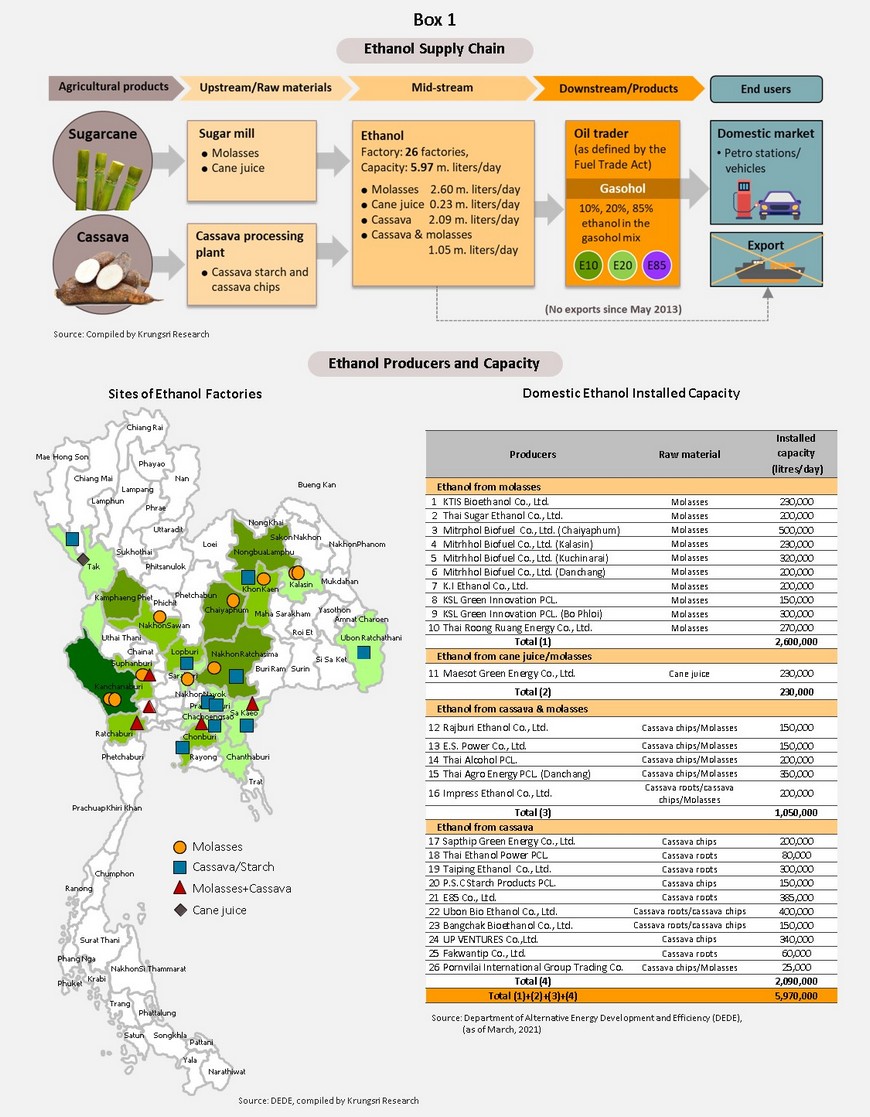

At present (as of April 2021), there are 26 ethanol distilleries operating in Thailand, most of which are downstream operations that are part of larger companies active in the sugar or cassava markets (Box 1). The majority of distilleries are located in the central and northeastern parts of the country, and these have a combined output of 5.97 million liters per day, up from an average of 5.92 million liters a year earlier. Of total daily production, 2.6 million liters is generated from molasses, 2.09 million liters comes from cassava, 1.05 million liters comes from a mixture of cassava and molasses, and 0.23 million liters is produced from sugarcane/cane juice (Figure 4).

The cost structure of the industry depends on the inputs used.

1) For molasses-based production, raw materials account for 60-70% of production costs. Operating costs take up a further 25-35%, and 5% goes towards fixed costs.

2) For cassava-based production, at 55-60%, raw materials contribute a lower share of overall production costs but operating costs are higher (35-40% of the total), while fixed costs are the same at 5%. Compared to molasses, using cassava as an input imposes higher overheads due to the more complex processing required to convert cassava starch into the sugars that are needed to produce ethanol.

The ethanol market is guided by a reference price, and this is determined by data collected by the Excise Department on sales of ethanol to fuel retailers on the domestic market. An average price, weighted according to the volume of actual sales, is thus announced on the 1st day of the month, and this has been used as the ethanol reference price since 1 January 2012. Producers’ margins (i.e., the gap between sale prices and production costs) are determined by: (i) the cost of inputs; (ii) changes in the reference price that may be driven by shifts in the proportion of the total output coming from molasses and cassava; and (iii) marketing costs of around THB 1-2 per liter.

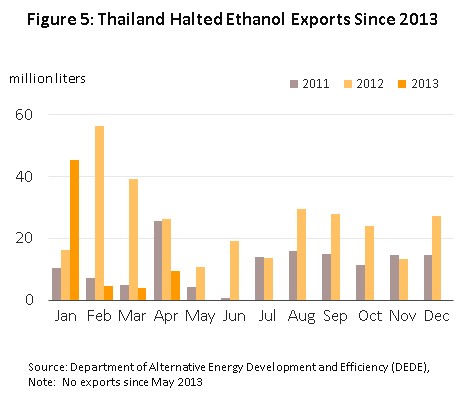

The ethanol market is slightly unusual in that there are generally no exports at all, the then government having ordered a halt to these in May 2013 (Figure 5) because at the time, the government was keen to ensure that following the ending of sales of 91 octane petrol on 1 January 2013, stocks of ethanol would be sufficient to maintain gasohol supplies. Despite this general prohibition, exports are in fact allowed in some circumstances, as happened in March 2014, when 4 million liters were exported, and again in December 2020, when the export of 54,000 liters was approved. (Prior to the ban, exports had taken place since 2007, though these had to be approved on a case-by-case basis by the Director-General of the Excise Department. At that time, the main export markets were the Philippines, Japan and the UK).

Major government policy and support for the ethanol industry is laid out in the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP), and this includes: (i) setting goals for production with reference to demand from the transport sector and the promotion of gasohol consumption; (ii) promoting the development of vehicles that are able to run on E85 gasohol; and (iii) encouraging the wider and more comprehensive distribution of biofuels (E20 and E85) on forecourts across the country. These policies have helped to underpin the expansion of the ethanol market, and their continued implementation is expected to positively influence demand in the coming period.

Situation

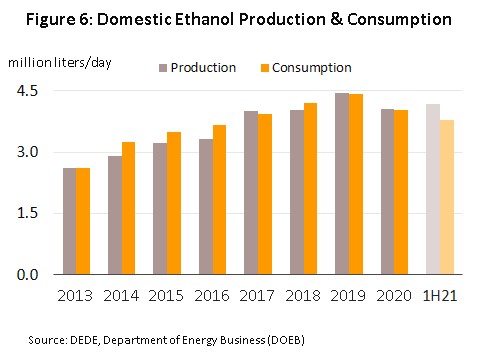

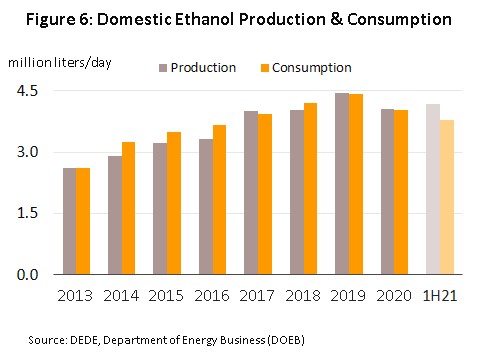

The move by the government to end sales of 91 octane benzene in January 2013 (at the time, 41% of sales of all benzene products) and instead to promote the use of gasohol as one of the AEDP alternative fuels helped to alleviate problems with an oversupply of production capacity that had weighed on the market through the period 2007-2012. Over these past few years, demand for ethanol has also been boosted by: (i) the effect of the First Car Buyer scheme, which pushed new car registrations to historic highs in 2011; (ii) prices for benzene that averaged THB 46.3/liter in 2013-2014, compared to average gasohol prices of THB 38.9/liter; (iii) the use of the Oil Fund to cross subsidize the sale price of E10 and E20, which has then caused a substantial increase in sales of the latter since 2016; (iv) the development and release to the market of new car models that can run on E20 and E85; and (v) the increase in the number of forecourts selling E20 and E85. Thanks to the combined effect of these factors, average daily ethanol consumption rose from 2.60 million liters in 2013 to 4.41 million liters in 2019, or average annual growth of 20.3%. At the same time, average daily ethanol output rose 14.5% per year, or from 2.60 million liters to 4.44 million liters per day (Figure 6).

and this then sharply reduced demand for travel and cut average car use. Alongside this, the serious drought that extended into 2020 meant that ethanol producers were simultaneously confronted with sharply increasing costs for inputs, and these factors caused disruption to the ethanol market, as described below.

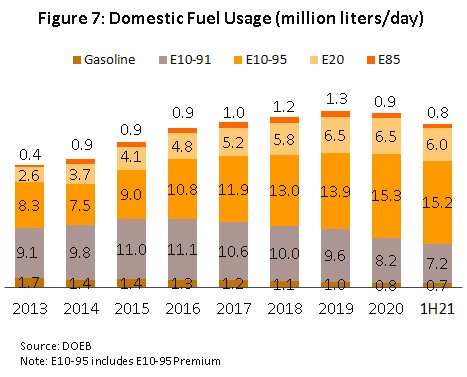

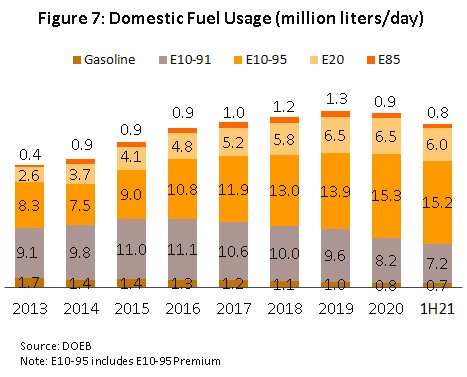

- Across the year, consumption of ethanol dropped 8.7% to an average of 4.03 million liters per day. The decline was strongest in the first half of the year (down 12.8% YoY), especially during the lockdown in April and May, when demand dropped on the widespread switch to working at home. However, the situation picked up in the second half of 2020, and consumption of ethanol returned to levels that were close to their pre-pandemic level. The easing of the lockdown naturally helped lift demand but in addition, consumer behavior underwent a major shift, and with take-up rates for e-commerce services exploding (Priceza estimates that the e-commerce market grew 81% in 2020), demand for delivery services saw very strong growth. Thus, for all of 2020, consumption of gasohol averaged 30.9 million liters daily, which represented a drop of just 1.0% from a year earlier (Figure 7). This was split between:

- E85 gasohol (2.9% of all gasohol sales): Down 30.2% YoY to 0.9 million liters per day.

- Gasohol E10 (75.9% of all gasohol sales): Up 0.2% YoY to 23.5 million liters per day.

- E20 gasohol (21.2% of all gasohol sales): Up 0.5% YoY to 6.5 million liters per day.

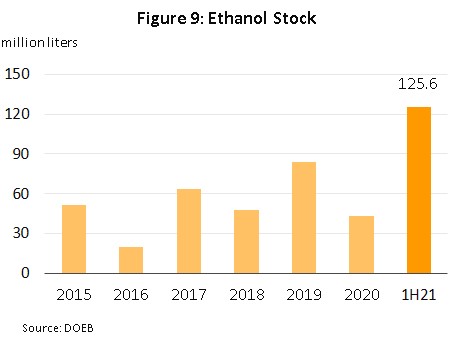

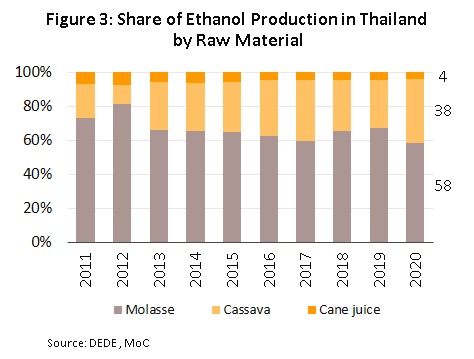

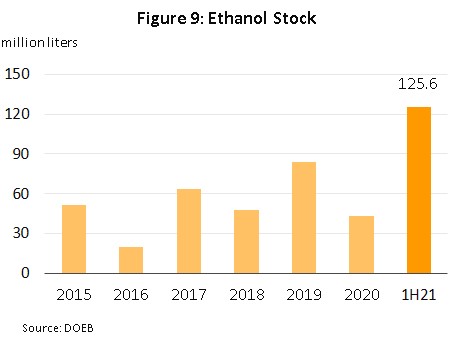

- The year’s troubles also pulled down ethanol production, which dropped 8.9% to an average daily total of 4.04 million liters on lower demand and the disruption to production caused by the lockdown. Production from molasses and cane juice (which together accounted for 62% of output, compared to 72% in 2019) slumped by respectively -21.3% YoY and -20.3% YoY to 2.35 million liters and 0.17 million liters per day, partly due to a drop in sugarcane yields. At the same time, cassava-based production (38% of the total) jumped 23.1% to 1.51 million liters (Figure 8) on an increase in the area of cassava under cultivation and consequent higher yields. Overall, production declined faster than demand and so by the end of 2020, stocks had fallen 57.6% from the previous year to a 4-year low of 42.8 million liters (Figure 9). For the year, capacity utilization also dipped to an average of 68.0% from its 2019 level of 75.3%.

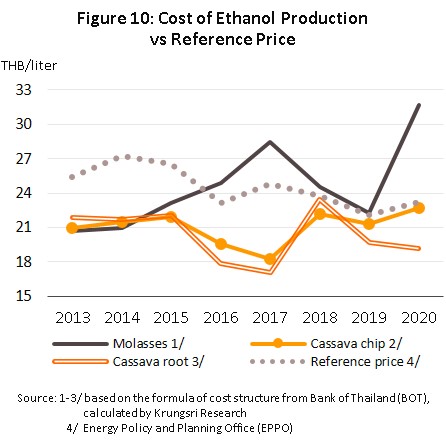

- The average 2020 reference price strengthened 5.2% to a 2-year high of THB 23.2 per liter (retail prices ran in the range of THB 24-25 per liter for the year[3]). Prices were pushed up by the higher cost of sugarcane and molasses, as well as by a surge in demand for industrial grade ethanol for use in the manufacture of pure alcohol and sterilizing hand gels.

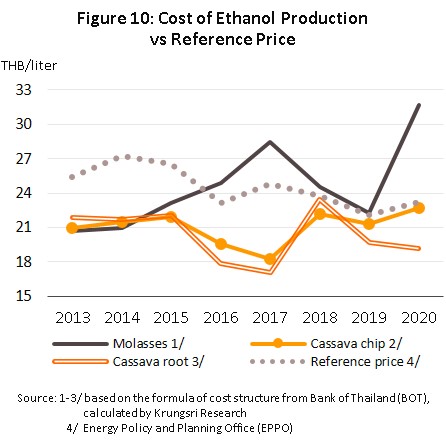

- The rising cost of molasses and fresh cassava contrasted with the falling cost of cassava chip (Figure 10), and so the direction of change in operators’ margins varied according to their preferred raw materials.

- Molasses-based production: Margins for ethanol producers using molasses narrowed to their slimmest in a decade on price rises for inputs that took the cost of molasses to a 10-year high of THB 5.8 per kilogram. Supplies were affected by the drought and the resulting fall in sugarcane that was processed during the year (in the 2019-2020 season, this totaled just 74.89 million tonnes compared to 130.97 million tonnes in the 2018-2019 season) and because of this, production costs rose 42.1% YoY to THB 31.7 per liter.

- Cassava-based production: Krungsri Research estimates that for ethanol distillers using fresh cassava, margins widened to a 3-year high on a fall in prices for inputs to THB 1.8 per kilogram (down 4.9%). Previously, farmers had increased the area of cassava that they had planted and this then boosted yields and lowered prices, gifting ethanol producers a -3.0% YoY cut in production costs (these fell to THB 19.2 per liter). However, for those using cassava chip, margins tightened following stronger demand from China, where a fall in corn stocks and an explosion in demand for ethanol-based products fed into a surge in demand and an 8.1% jump in costs, which then rose to an average of THB 5.6 per kilogram. As such, production costs for those using cassava chip climbed 6.5% YoY to THB 22.7 per liter.

Through the first half of 2021, domestic demand for ethanol suffered again under the impact of a new outbreak of Covid-19 that gathered strength through the year, and in response to this, the authorities were forced to issue new lockdown orders and to restrict inter-province travel. Inevitably, this again undercut demand for transport fuels, and consumption of ethanol thus slipped 2.2% YoY to an average of 3.77 million liters per day. At the same time, though, daily output edged up 2.53% to 4.19 million liters on a surplus of cassava during the period of the harvest, and this discrepancy was reflected in an expansion in stock holdings to 125.4 million liters (as of June 2021).

For 1H21, the ethanol reference price climbed 11.3% YoY to an average of THB 25.5, its highest since 2016. Prices were buoyed by a 63.5% YoY leap in the cost of molasses and, thanks to the new waves of Covid-19 infection, stronger demand the manufacture of alcohol-based sterilizing products.

Outlook

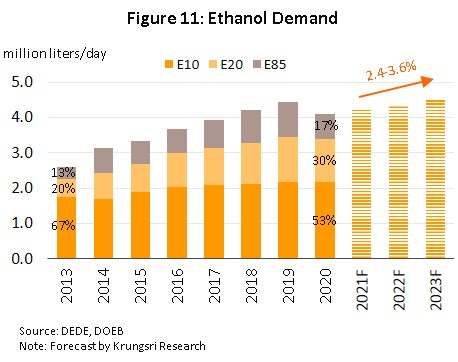

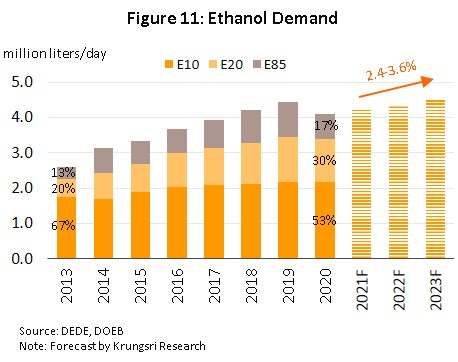

Krungsri Research sees demand for ethanol rising 2.4-3.6% annually over 2021-2023, which would then bring total daily consumption up to 4.2-4.5 million liters (Figure 11). The market for ethanol will move in step with sales of gasohol E10 (95) and E20, with sales of the latter expected to rise from 21% of all gasohol sales in 2020 to 25-30% of the total by 2023, which would in turn then increase the proportion of Thai-made ethanol used in gasohol mixes to 55-60% of all end uses. Factors supporting the expected increase in demand will include the following.

- The government is promoting the use of E20 gasohol and to help encourage greater consumption of biofuels, E20 will replace E10 as the standard mix in 2023 (at present, the authorities are in the process of developing a new model for calculating the reference price). As part of this strategy, distribution of E10 (91) will also cease in 2022, and these reforms are expected to lift overall demand for ethanol from the 2020 level of 4-5 million liters per day to closer to 6-7 million liters per day. However, from 2021, subsidies to the sale price of E85 will end as the government looks to reduce pressure on the Oil Fund, and production of E85 will cease entirely in 2022, though because sales of E85 represent just 2.9% of all gasohol distributed to the market, the effects of this will be limited.

- Overall sales of gasoline are forecast to strengthen by 2.4-3.6% per year as the economy returns to more normal conditions, and this is expected to happen during the second half of 2022, once vaccination targets have been reached and the country is able to fully reopen to foreign arrivals.

- The size of the national vehicle fleet that is able to run on gasohol is forecast to expand by 1.5-2.5% annually, rising from 29.5 million in 2020 to 30-32 million over the next 3 years. Most significantly, sales of new vehicles, which are now generally all able to run on E20, are expected to run to 0.8-0.9 million per annum.

Operators are responding to this anticipated increase in demand by investing in additional production capacity, as seen in, for example, the Nakhon Sawan Biocomplex, which is expected to open for commercial operations in 2023. The industry is benefiting from the government’s 2015-2026 strategy for sugarcane and sugar processors, which has set a target of increasing the total area given over to sugarcane from 10 million to 16 million rai by 2026, and from the 2017-2036 cassava strategy, which aims to double cassava yields from 3.5 to 7.0 tonnes per rai. This would then allow daily output to expand to around 7 million liters by 2026, but the relatively slow rate of demand growth will mean that over the next 3 years, capacity utilization will average 68-70%, barely up from the 2020 level of 68% (Figure 12).

Despite the generally positive outlook described above, challenges remain for the industry, and the following three in particular will have to be addressed.

(i) Players may have to contend with a shortage of inputs since cultivation and yields of raw materials is dependent on inherently unpredictable climatic conditions, while molasses and cassava are also finding new uses in downstream industries, e.g., in the production of food and beverages, animal feed and alcohol. In addition, demand from Chinese manufacturers for cassava (in place of corn) to use in alcohol production is also strengthening.

(ii) The cost of inputs is rising, and this may put pressure on operators’ production costs and margins.

(iii) Consumer fears over the use of gasohol mixes with a high ethanol content are proving to be very persistent. These complaints include a greater number of engine problems and higher fuel consumption compared to low-ethanol mixes, and the impact of these and their effect on consumer preferences is likely one factor underlying the weak sales of E20 and E85 compared to E10.

Over the longer term, the industry is also exposed to significant risks arising from the growing popularity of hybrid and electric vehicles and the expected effect of this on sales of transport fuels. The rising impact of vehicle electrification is in fact reflected in the amendments made to the AEDP2018 plan compared to the 2015 version; in the latter, the government set a target for daily ethanol production that climbed to 11.3 million liters in 2037, but in the version produced 3 years later, this had been cut to 7.5 million liters, with a greater share of this going to electricity generation.

Krungsri Research’s view

Over the period 2021 to 2023, the ethanol industry will enjoy ongoing growth on: (i) government plans to establish E20 as the standard fuel mix by 2023; (ii) growth in the consumption of gasoline that should average 2.4-3.6% per year; and (iii) an annual 1.5-2.5% increase in the number of vehicles on Thai roads that are able to run on gasohol. Players that operate comprehensive, vertically integrated ethanol supply chains that stretch from upstream production to downstream distribution will have a clear competitive advantage over those operating more isolated businesses. However, all players will have to face the possibility of shortages and rising prices for raw materials, and this may then put pressure on profitability.

- Molasses-based ethanol producers: Income is expected to remain broadly unchanged from last year. Compared to smaller, independent operators, ethanol producers that are owned and operated by sugar processors will have much more secure access to raw materials and will generally have lower production costs. Independent players will thus be exposed to a significantly higher risk of rising costs and shortages of inputs.

- Cassava-based ethanol producers: Income will rise slowly in this segment. The cost of inputs is expected to fluctuate with demand for cassava from other domestic industries (e.g., processors and producers of food and beverages, animal feed, and alcohol) and from the export market. This may then lead to periodic gaps between demand and supply, which will push up costs and weigh on operators’ margins.

[1]A replacement for octane additives in benzene, or Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether.

[2]Gasohol 91 and 95 are made by mixing lead-free benzene with 10% ethanol. This results in 91and 95 octane gasohol, which can then be used in vehicles in place of regular 91 and 95 octane mineral fuels.

[3]The domestic sale price is calculated from the ethanol reference price and a further THB 1.5-2.0 for marketing.

.webp.aspx)