EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Krungsri Research sees the Thai cassava industry enjoying solid rates of growth over the years 2023 to 2025. Through the period, demand will remain strong from both domestic industrial consumers, especially the food processing and ethanol industries, and overseas buyers, most obviously from market expansion in China. Demand from the latter will be buoyed by: (i) increased consumption by industry, especially for use as an input into the production of ethanol, animal feed, and disinfecting alcohol, for which demand will continue to be stoked by ongoing outbreaks of COVID-19; and (ii) concerns over food and energy securities that are being driven by the now drawn-out war in Ukraine and that have fed into increased stockpiling of commodities, including cassava. Nevertheless, players will also have to contend with challenges that will include uncertainty over outputs caused by variability in the climate and outbreaks of cassava mosaic disease, and the market that is highly dependent on exports to China.

Krungsri Research view

Overall, players in cassava supply chains will benefit from favorable business conditions in downstream industries on domestic and overseas markets, and this will then support increases in income across the industry over the period 2023-2025.

-

Producers of native starch: An improving outlook for food and drinks processors, paper manufacturers, and ethanol distillers (produced principally from cassava starch slurry) will support stronger demand on domestic and overseas markets and as such, incomes will tend to rise.

-

Producers of cassava chip: Income will likely edge up slightly on stronger sales in China, where cassava chip is used as an input into food processing and the production of ethanol, alcohol, and animal feed, and this will then provide players with the opportunity to build additional profits. However, exporters are exposed to risk arising from greater domestic competition to secure what may be insufficient supplies of fresh cassava. In addition, players remain highly dependent on the Chinese market, leaving them exposed to changes in demand or purchasing policies in China, while competition for the Chinese market is also rising from the CLMV region.

-

Producers of modified starch: Income will grow solidly on an expansion in downstream industries, especially in Asia, that include manufacturers of medicines, cosmetics, food, paper, sweeteners, and chemicals. Growth will also come from a broadening of exports into new markets, but on the downside, players may face stronger competition from starches produced from other sources that have a wide range of desirable qualities.

-

Producers of cassava pellets: Players’ income is exposed to risk from uncertain market conditions, and demand will tend to rise only when food security is threatened and the supply of alternatives is disrupted, for example by the Ukraine war or outbreaks of COVID-19. Thus, if the impact of these lessens, demand for cassava pellets for use as an animal feed or as a biofuel will tend to weaken.

-

Traders in cassava products: It is expected that demand for cassava on domestic and export markets will grow steadily and as prices rise, farmers will expand the area under cultivation. This will then support higher incomes, allowing operators to remain in profit.

- Cassava growers: Incomes will gradually edge up on rising demand from industry that will result in stronger prices. In addition, farmers are also benefiting from government support (e.g., price guarantees, soft loans, and measures to absorb additional supply), and so it will be possible for growers to stay in profit. However, the spread of cassava mosaic disease and the rising cost of fertilizer and labor will pose challenges that will need to be overcome.

OVERVIEW

Cassava is a carbohydrate-rich crop that has a wide range of uses in the so-called ‘4Fs’ of: (i) food for human consumption, (ii) feed for animals, (iii) fuel, which in the form of ethanol is produced from cassava, and (iv) factories, where it is used to make alcohol, citric acid, clothing, medicines, paper, and chemicals.

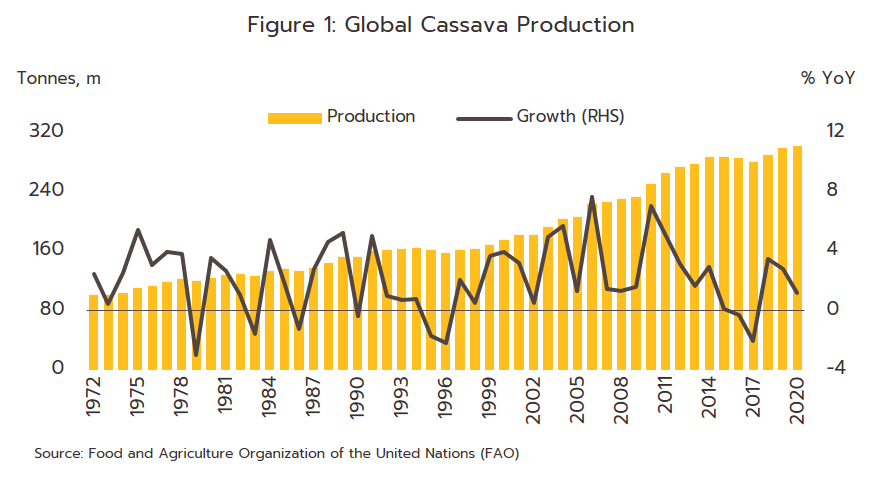

For many years, global demand for cassava has grown strongly thanks to its many industrial uses and the fact that it has often been cheaper than other starchy crops. This has then lifted it to the status of being the world’s 5th most important crop, after corn, wheat, rice, and potatoes.

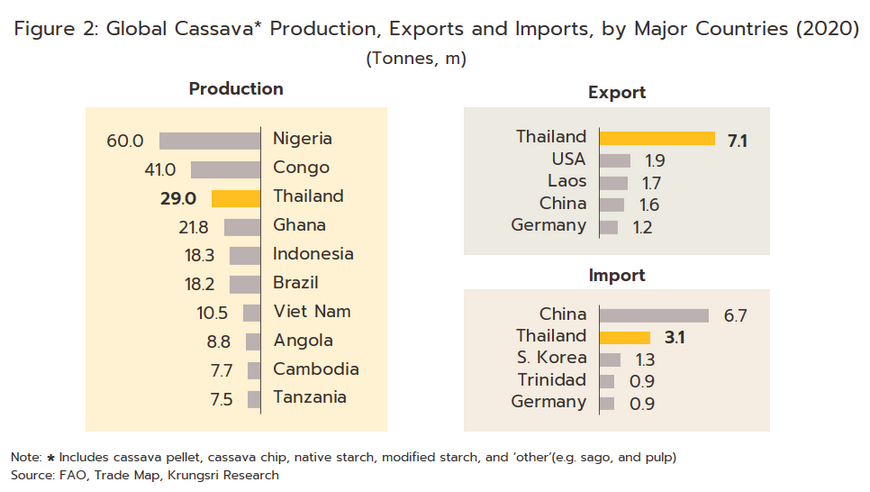

As of 2020, a total of 303 million tonnes of cassava were produced globally (Figure 1). Contributing 64.0% of the total, Africa was the most important cassava-producing region, followed by Asia[1] (27.0% of the total), the Americas (8.9%) and Oceania (0.1%). By individual country, Nigeria was the world’s biggest producer, with 19.8% of all outputs globally, followed by the DR Congo (13.6%), Thailand (9.6%), Ghana (7.2%), Indonesia (6.1%), and Brazil (6.0%) (Figure 2), although heavy investment by Thai and Chinese players in production in Vietnam and Cambodia has meant that outputs in these two countries have been rising rapidly over the past 10-15 years.

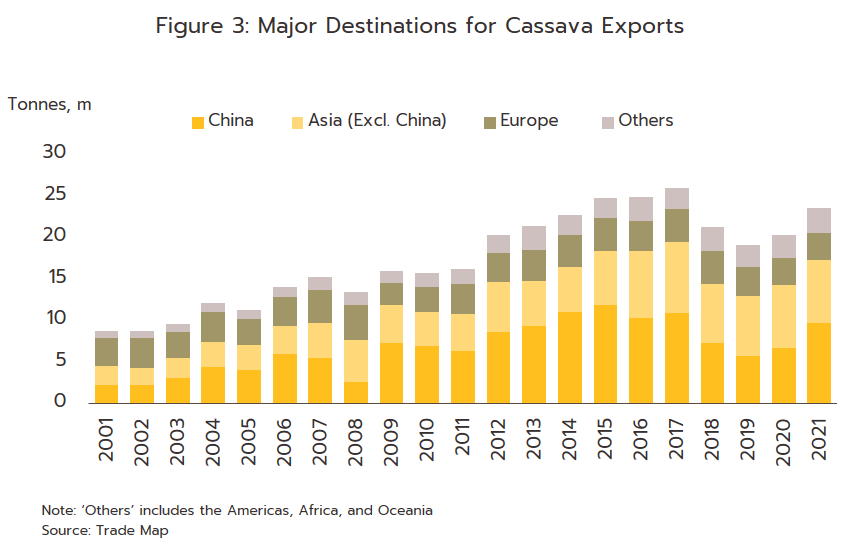

However, although Africa is home to the world’s most important cassava-producing nations, African production is largely for domestic consumption since in these countries, the crop plays an important role in local diets, and in ensuring food security and supporting economic activity. African-produced cassava is therefore principally consumed as fresh and processed products that are distributed on domestic markets. By contrast, Thai production is oriented towards overseas markets and the country is thus the world’s most important exporter (Figure 2). In terms of export destinations, global markets for cassava are largely supported by demand from Asia, especially China, which alone accounts for 41.3% of all cassava imports made worldwide (Figure 3).

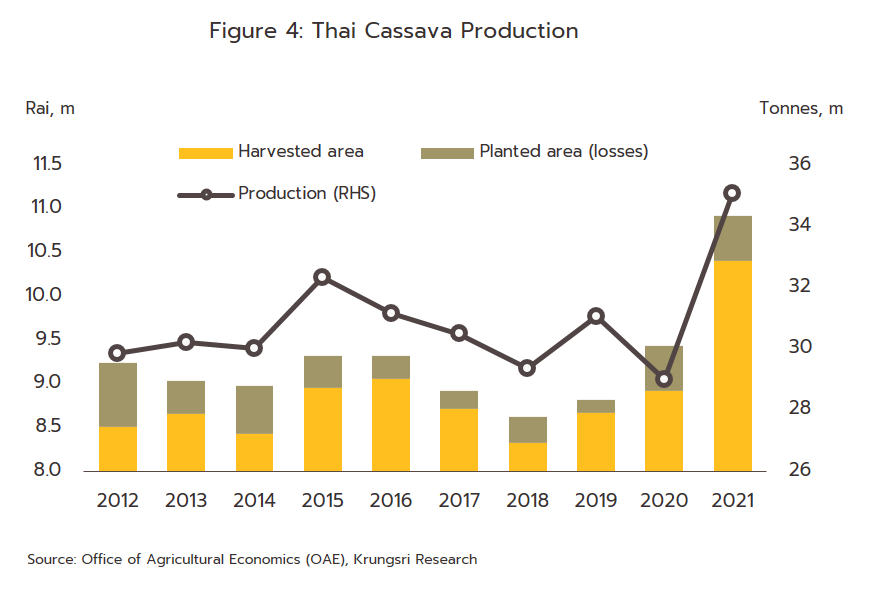

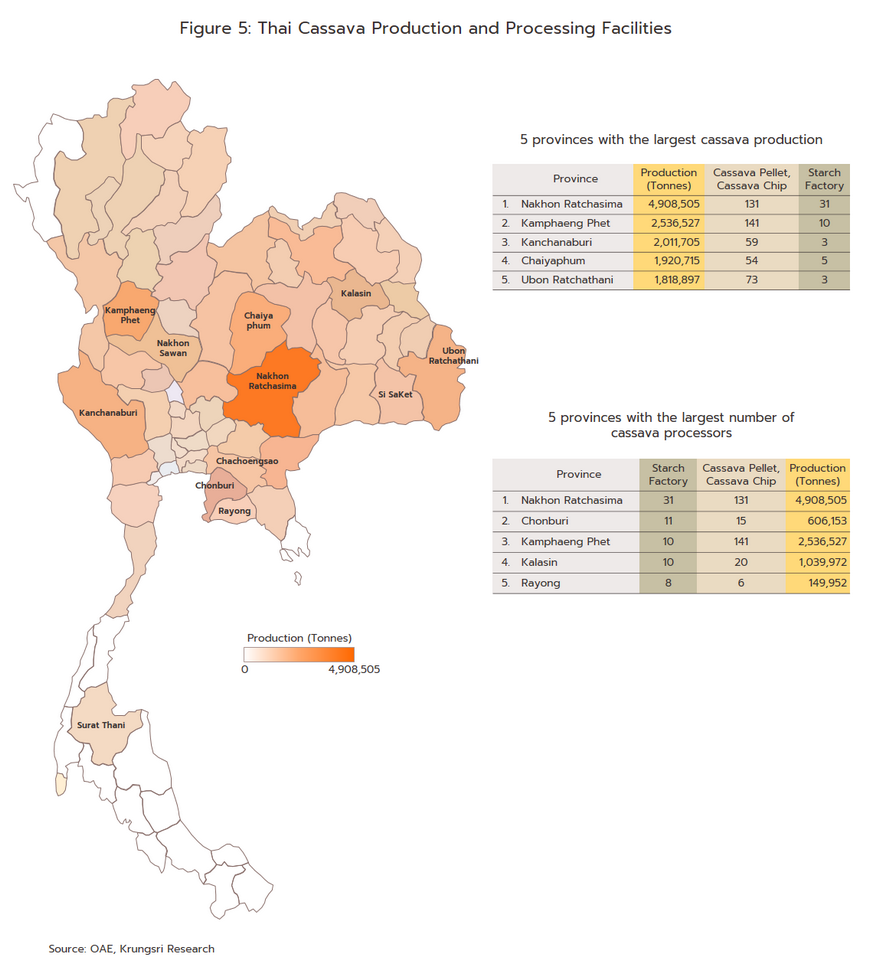

Over the past two decades, rising demand on export markets has fed into an expansion of Thai cassava processing capacity and through this, to a steady rise in the total area planted with cassava; as of 2021, 10.4 million rai (1.66 million hectares) of Thai farmland was harvested with cassava, and this yielded roughly 35.1 million tonnes of raw product[2] (Figure 4). Cassava cultivation is clustered most heavily in Nakhon Ratchasima (14.1% of all Thai cassava harvested area), followed by Kamphaeng Phet (7.3%), Kanchanaburi (5.8%), and Chaiyaphum (5.5%).

As of 2022, Thailand was also home to 1,205 cassava processing facilities[3] but for convenience and to save on transportation costs, these are generally located close to cassava producing areas, and so with 162 plants, Nakhon Ratchasima has the highest concentration of all of Thailand’s provinces, followed by Kamphaeng Phet (151), Nakhon Sawan (88), and Chaiyaphum (59). Thai players have also sited facilities in positions that allow them easy access to imports from neighboring countries, especially Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar, though to ensure secure supplies of inputs, players have in addition established basic processing facilities in these countries. Thus, there are 76 cassava plants in Ubon Ratchathani, 62 in Kanchanaburi and 33 in Sri Saket, while to make exports more convenient, there are a further 26 facilities in Chonburi, 14 in Rayong and 14 in Chachoengsao, these locations having the advantage of ready access to major ports (Figure 5).

Thai cassava outputs can be divided into two principal categories.

-

Dried cassava products: In this group, the most important product is cassava chip, which is used as an input into the manufacture of animal feed, alcohol and citric acid. Thailand is currently home to 1,025 facilities (96% of all cassava processing plants) that produce dried cassava chip. A further 28 (2.6%) process cassava pellets[4], 12 (1.0%) provide drying yards[4], and 8 (0.2%) produce other types of processed cassava goods (e.g., cassava chip snacks and crushed or milled cassava used as an animal feed).

-

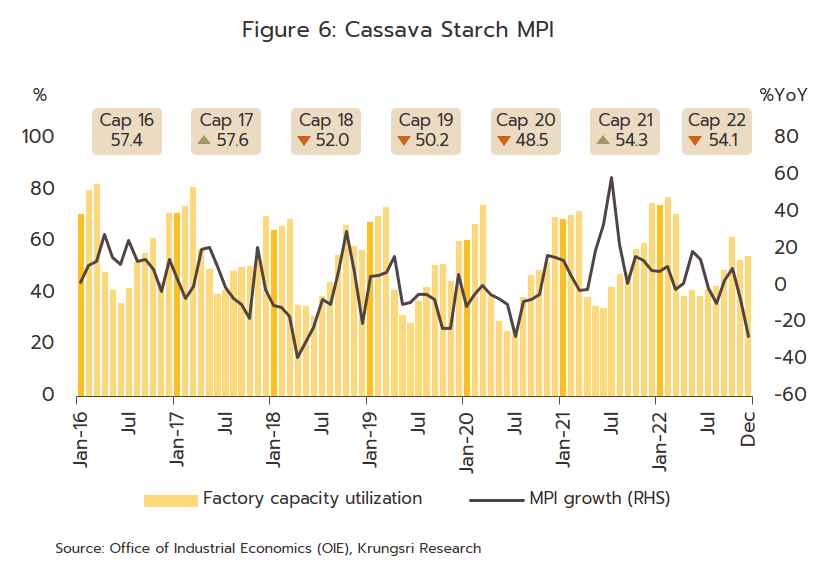

Cassava starch products: The initial output of cassava starch processing is ‘native starch’, which may be sold for household consumption as a cooking ingredient, or used in the manufacture of ‘modified starch’[5], a high value-added good that is an input into a wide variety of downstream industries, including the production of monosodium glutamate, sweeteners, sauces, cosmetics and medicines. At present, there are 105 facilities in Thailand producing native starch and a further 27 producing modified starch. Generally, the initial processing of cassava into starch occurs at the end of the year or the start of the next year because this period follows on immediately from the main harvest. Thus, both the cassava starch manufacturing production index and the industry’s capacity utilization typically peak between December and March (Figure 6).

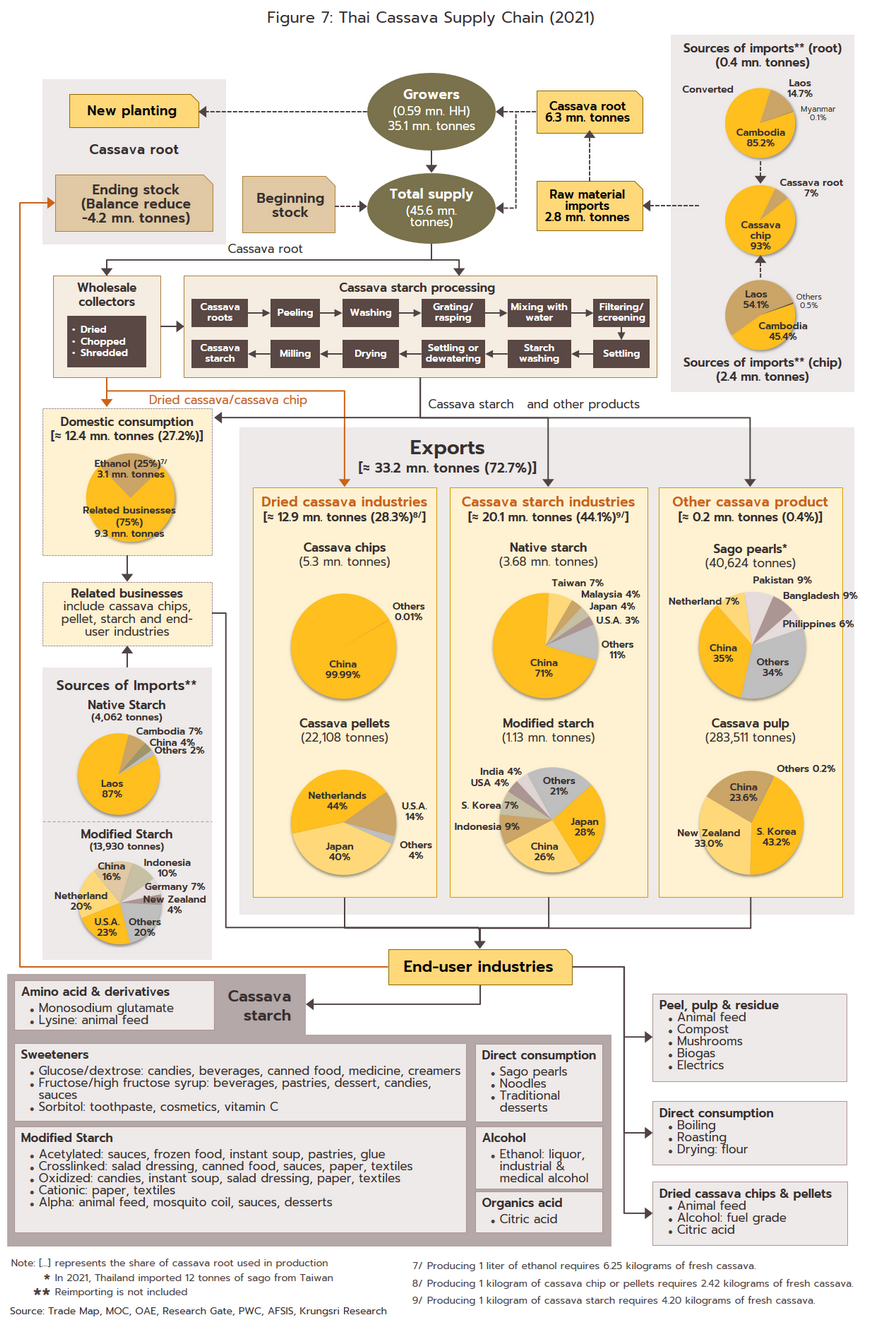

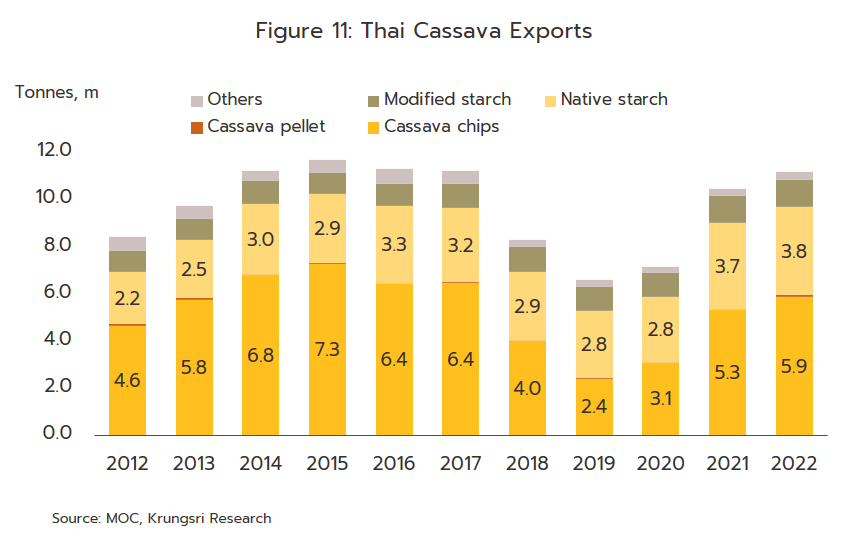

Considering the Thai cassava supply chain as a whole, in 2021, 77.0% of inputs to cassava processing was sourced domestically and only 13.8% came from imports (from neighboring countries). These supplied 2.4 million tonnes of cassava chip[6] and 0.4 million tonnes of fresh cassava, and together these accounted for 99.3% of all cassava imports by volume. The balance of supply (9.2%) came from stocks held from the previous year. In total, 72.7% of Thai cassava output was used to supply export markets, with the remainder going to the domestic market, where it is either consumed directly or used as an input into industrial processing (Figure 7).

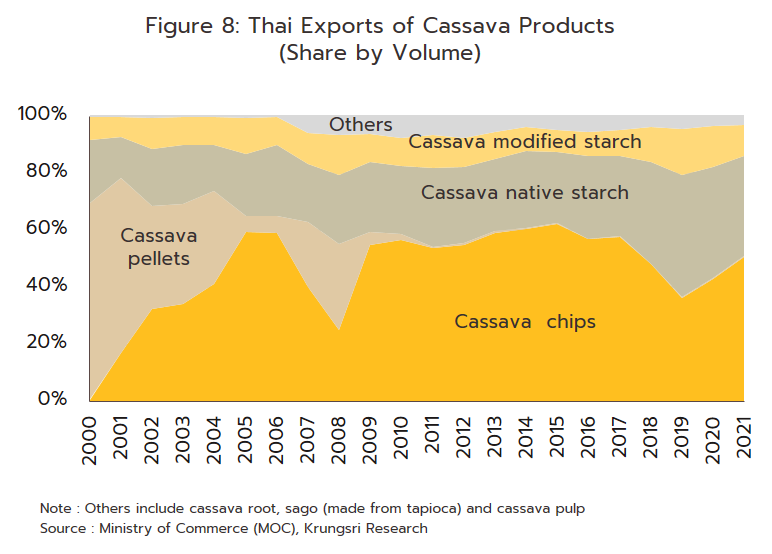

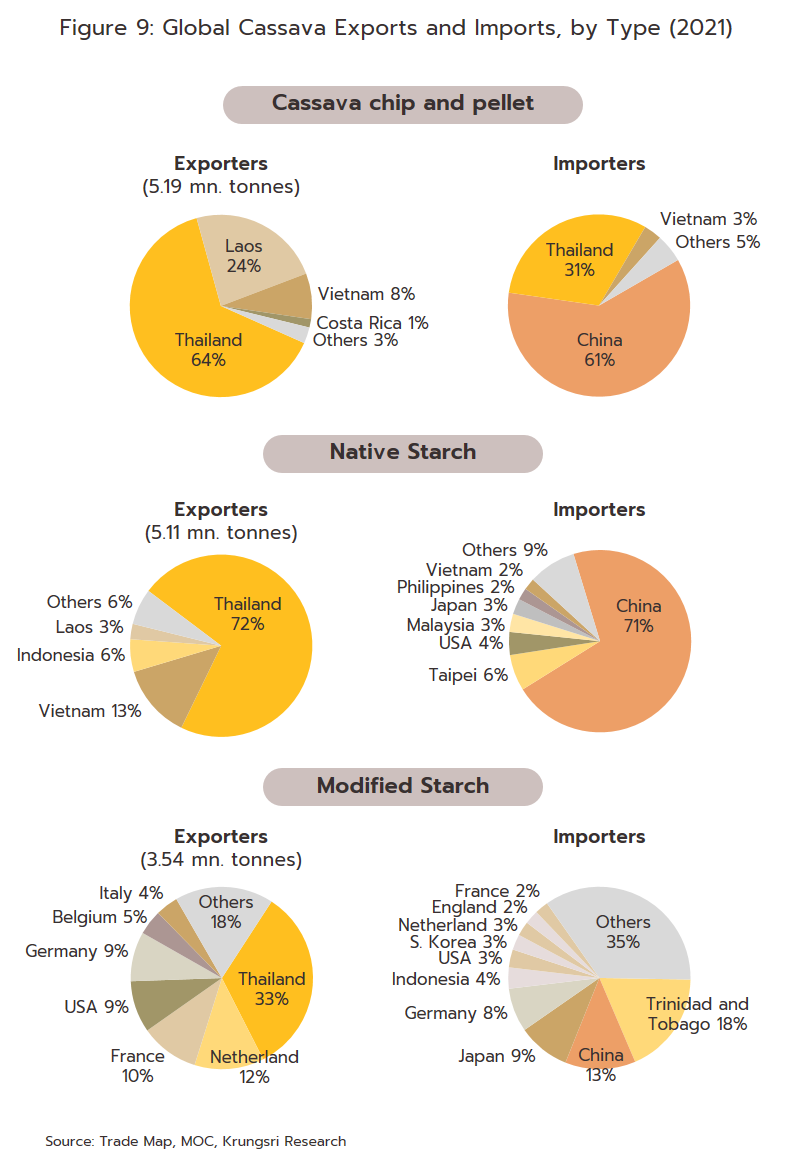

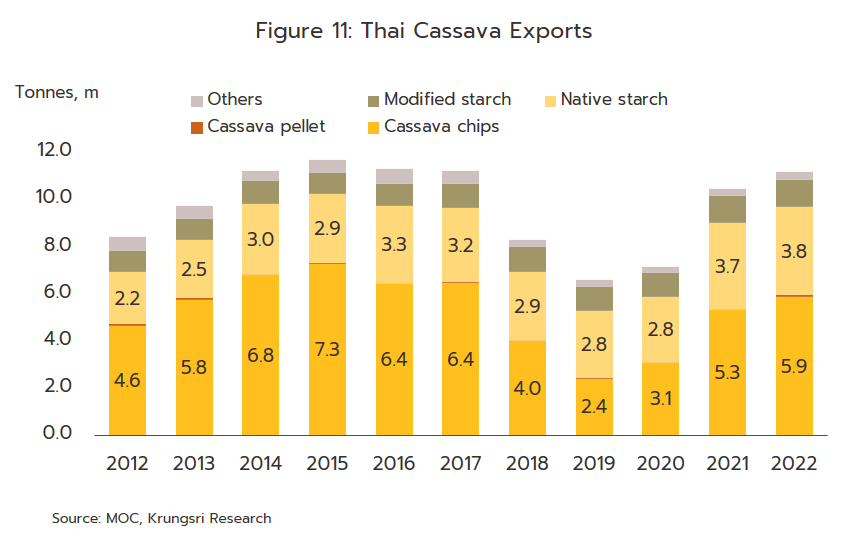

Thanks to its ready access to inputs, Thailand is the world’s leading exporter of cassava products, and the country’s market share of global export sales now extends to 72% for native starch, 64% for cassava chip, and 33% for modified starch. However, following the 2005 decision by the EU to stop imports of cassava pellets[10] (the EU had until then been a major importer) and to switch to the use of alternatives, exports of these from Thailand have dropped to very low levels (Figure 8). The change in EU policy also had the effect of significantly altering the structure of Thai exports, which moved to an almost total dependency on Asian export markets, and in particular on sales to China[11], which with an 80% share of all Thai exports of cassava products is by far Thailand’s most important market (Figure 9).

-

Cassava chip: In 2021, by volume, 50.7% of Thai cassava products were of cassava chip (Figure 8), almost all of which went to China (the market for close to 100% of Thai exports of cassava chip), where it is used to manufacture alcohol, ethanol, animal feed[12], and citric acid. However, the structure of the export market and the extreme concentration of purchasing power means that Thai suppliers have only a weak bargaining position, and so they are exposed to significant levels of risk should there be a change in Chinese policies towards sourcing imports. This is in fact what happened in 2018-2020, when China cut its imports of cassava chip and switched instead to using domestically produced corn, with significant knock-on effects for Thai exporters.

-

Native starch: This accounted for 35.2% by volume of all exports of cassava products from Thailand. The main markets for this again include China (which took 71% by volume of all exports of native starch), followed by Taiwan (7%), Malaysia (4%), Japan (4%) and the US (3%), although the exact state of export markets depends to a large degree on the health of industries that use native starch as an input. These include food processing, paper production, beverages, and textiles.

-

Modified starch: This accounts for another 10.8% of Thai cassava exports by volume. Strong global demand has been sustained by a positive outlook in downstream industries, including for producers of food, cosmetics and medicines. The main export markets for modified starch are Japan (which bought 28% of all 2021 exports of modified starch by volume), China (26%), Indonesia (9%) and South Korea (7%).

-

Cassava pellets: The 2005 decision by the European Union13/ to cut imports of cassava pellets had profound impacts on producers, and pellets now account for just 0.2% of total cassava exports by volume. This segment has in addition been handicapped by the difficulty Thai players have in competing with similar products made from other substitute crops (e.g., corn, wheat, and barley).

-

Other cassava products: The remaining 3.1% of Thai cassava exports by volume comes from sales of fresh cassava, sago (made from cassava starch), and cassava pulp. In 2021, the main buyers of these products were South Korea (38% of exports of these, by volume), New Zealand (29%), and China (25%).

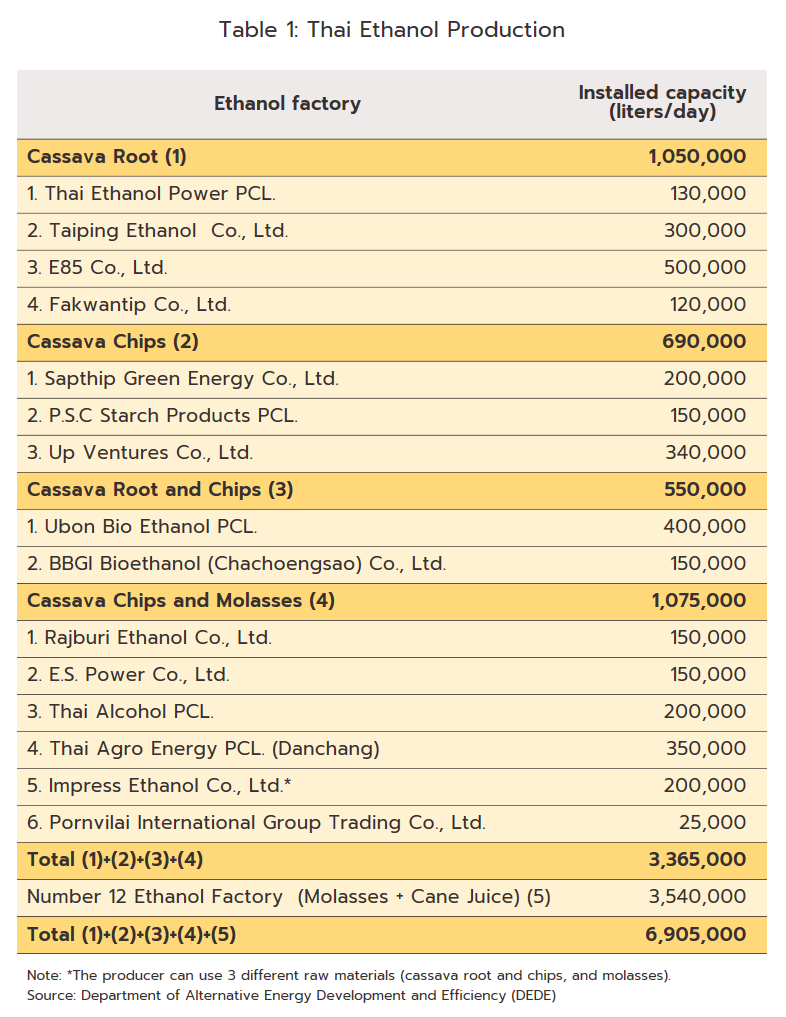

In addition to being consumed directly in households and in the manufacture of animal feed, cassava is also used domestically as an input into other industries, including the processing and production of food and beverages, medicines, cosmetics, chemicals, and alcohol. Large players have also invested in downstream industries, including ethanol production and the generation of bioenergy from cassava pulp and other waste products. The electricity that is produced from this may then be sold on or used by the cassava processor itself (Table 1).

SITUATION

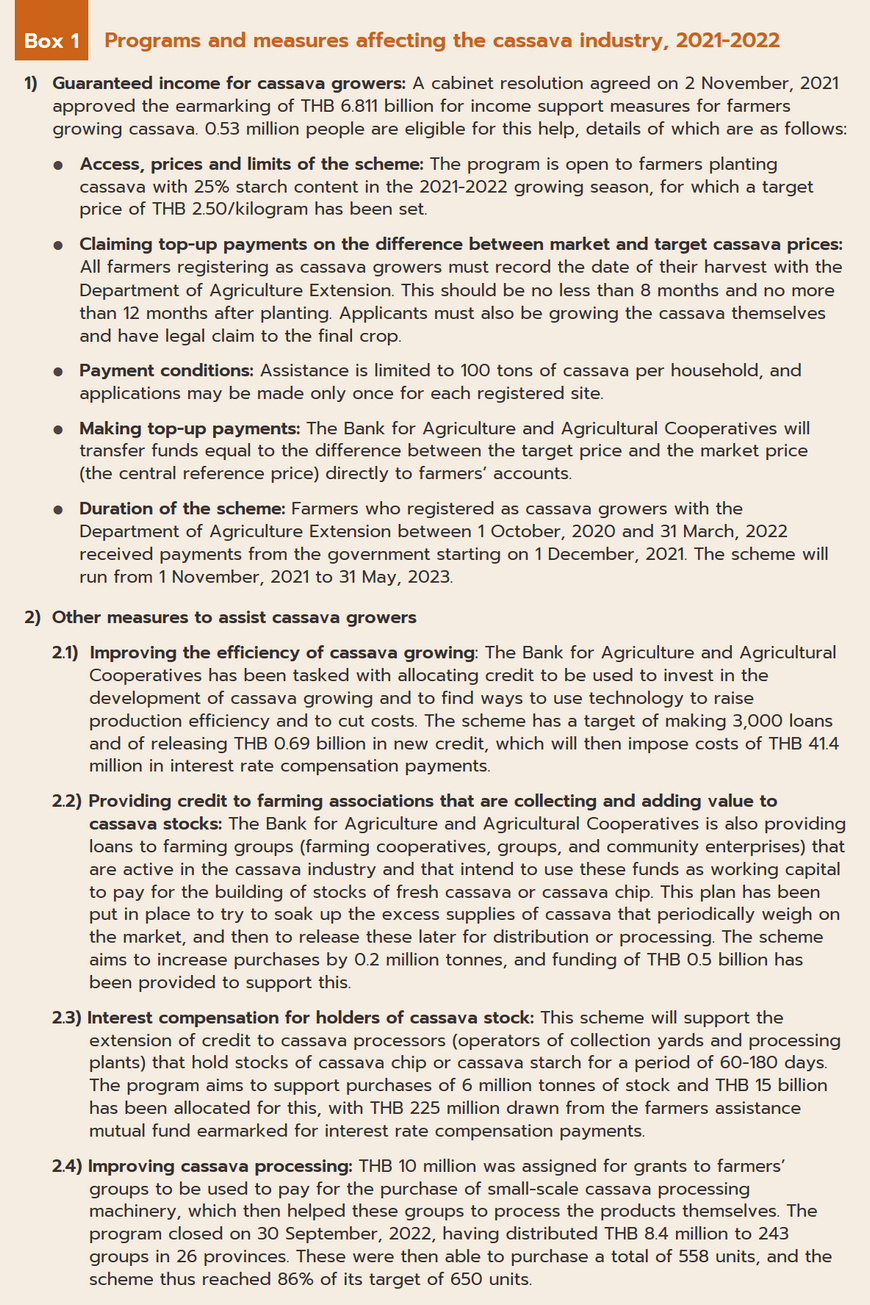

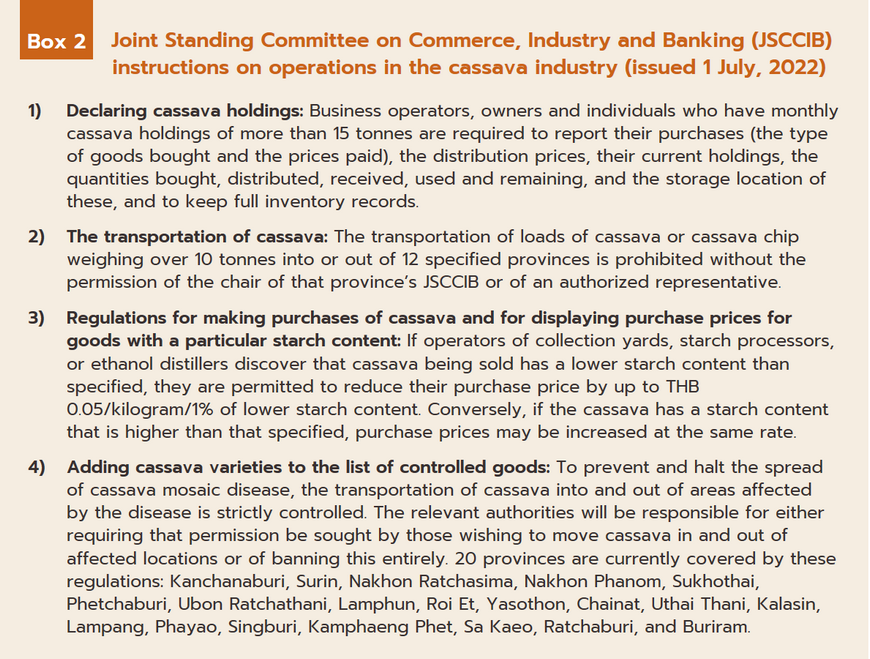

The Thai cassava industry enjoyed positive business conditions through 2022, with growth supported by a combination of stronger demand for cassava as an alternative to other crops, recovery in purchases from industrial consumers, and concerns over food and energy security. However, despite the incentive effects of high prices, support from the government, and favorable climatic conditions, the extent of the flooding in 2022 caused quantities to dip.

-

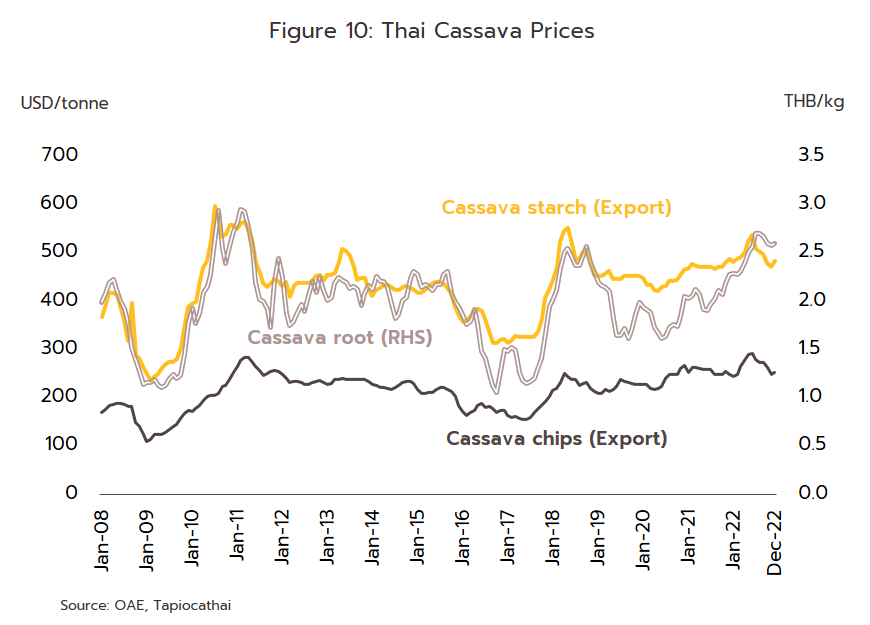

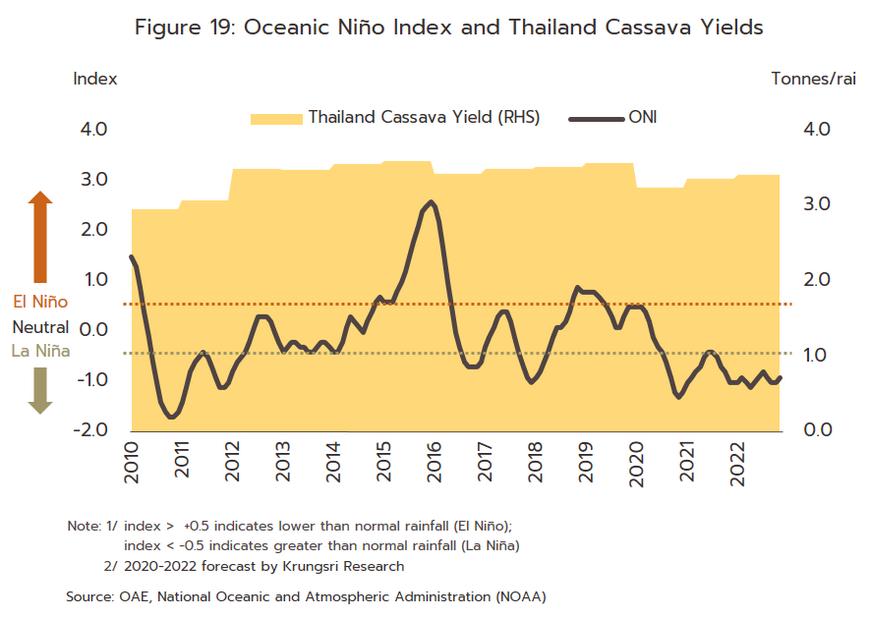

Outputs have slipped in 2022, and these are expected to be down -3.1% to 34.0 million tonnes on the impact of flooding in September and October 2021. The Office of Agricultural Economics therefore estimates that despite the incentive effect of prices that have remained high since 2H20 (Figure 10) and government income guarantee schemes, at 9.9 million rai (1.58 million hectares), the total harvested area of cassava will have shrunk by -4.7% in 2022. However, per rai yields are up 1.7% to 3,428 kilograms/rai (21,425 kilograms/hectare) on: (i) better weather and greater access to irrigation water; and (ii) use of higher yielding cultivars and better techniques for managing and protecting against infections with cassava mosaic disease.

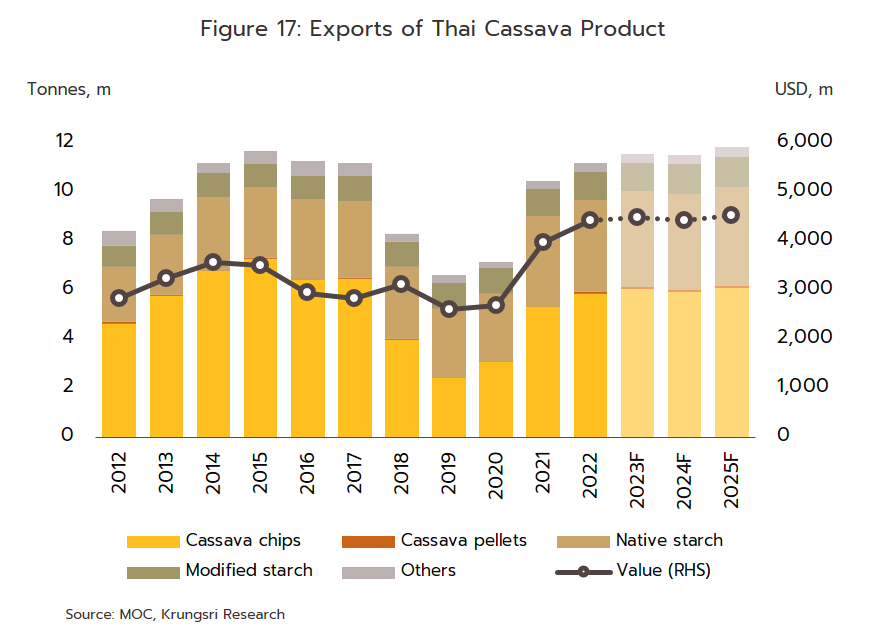

- Exports to the main overseas markets are strengthening, and for 2022, these are up 6.9% YoY to 11.2 million tonnes and this brought in income of USD 4.41 billion (+11.2%) on: (i) stronger Chinese demand that is attributable to (i.i) the effect of the zero-COVID policy on maintaining demand for disinfecting alcohol; (i.ii) the easing of the outbreak of African swine fever, which is then adding to demand for animal feed; and (i.iii) the need to replace diminishing domestic stocks of corn; and (ii) rising fears concerns over food and energy security caused by the war in Ukraine, which is then pushing many countries to step up imports of cassava. The situation for individual product categories is given below.

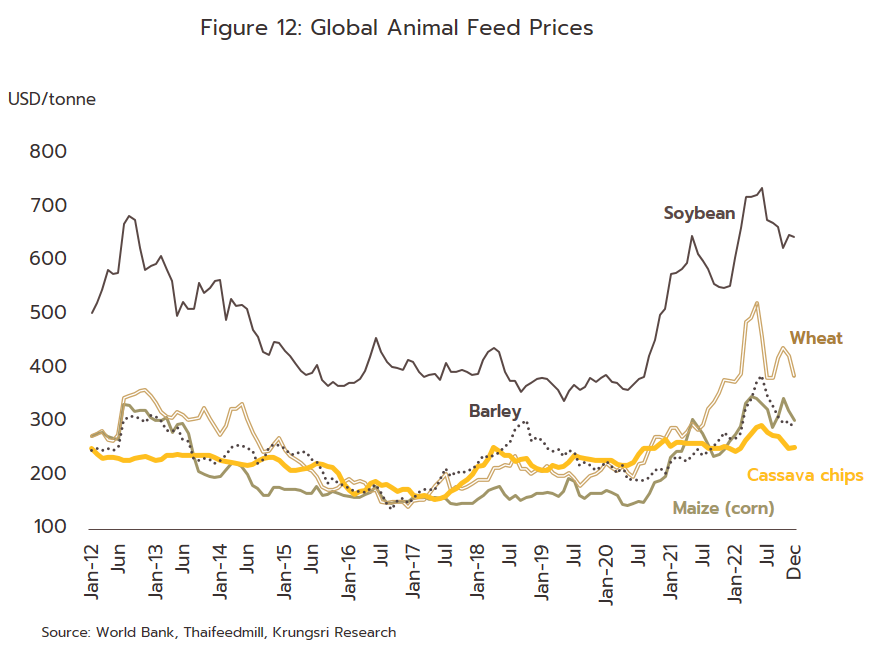

- Native starch: Over 2022, exports totaled 3.8 million tonnes and this generated receipts of USD 1.84 billion, these figures representing increases of respectively 2.0% by volume and 8.2% by value. Exports benefited from the fact that while cassava prices increased 4.6% YoY, the prices for alternatives escalated much more sharply, with prices of barley, corn, and wheat up by respectively 30.1%, 22.8%, and 36.4% (Figure 12). Given this, buyers in the main markets in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines all increased imports, principally for use in the production of food and drinks, paper, glue, textiles, and fiber and particle board. Stronger demand fed through into higher export prices for Thai native starch, and thus this rose 6.2% to USD 490/tonne.

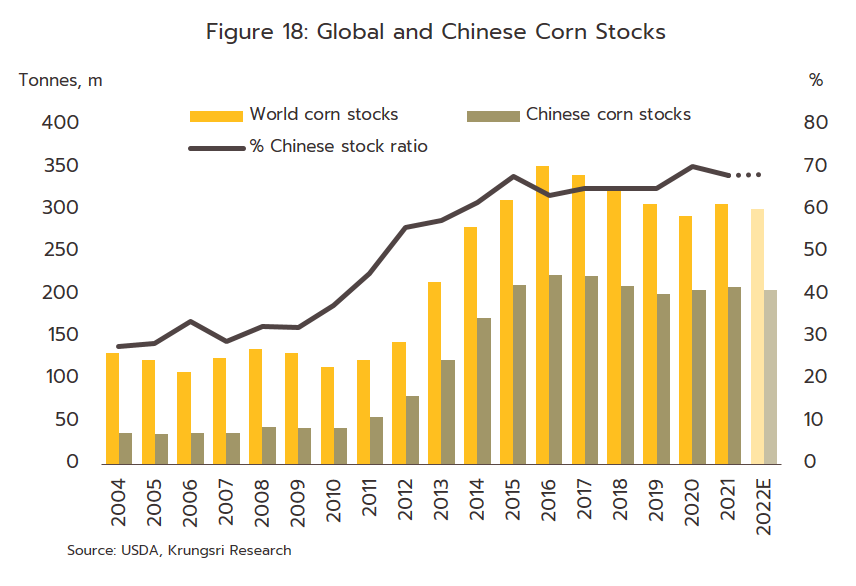

- Cassava chip: 2022 exports rose 10.3% by volume and 13.6% by value to totals of 5.9 million tonnes and USD 1.50 billion respectively. The strength of the market can be attributed to: (i) the spread of COVID-19 in China that then created additional demand for cassava chip for use in the production of ethanol and alcohol; (ii) recovery in the animal feed industry; and (iii) a decline in stocks of corn (used in China as an alternative to cassava) over 2018-2019. As a result of this, export prices increased by 4.4% YoY to USD 260/tonne.

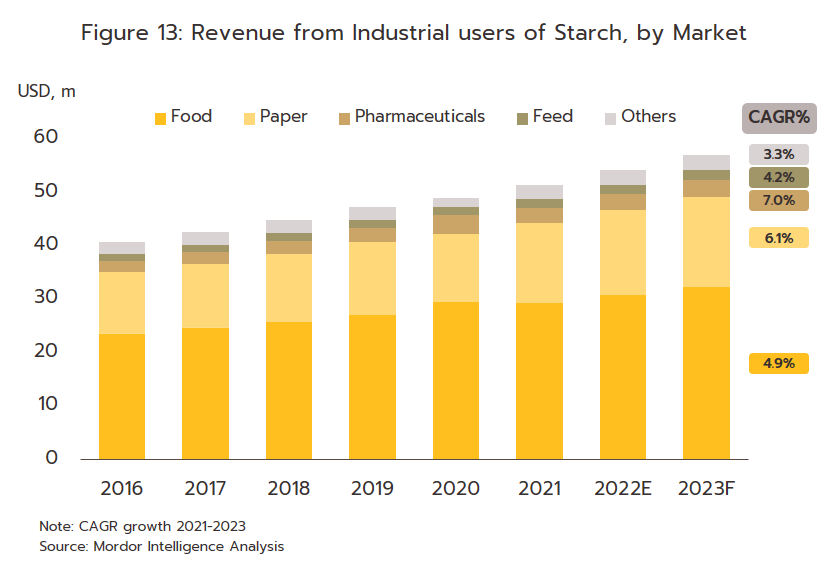

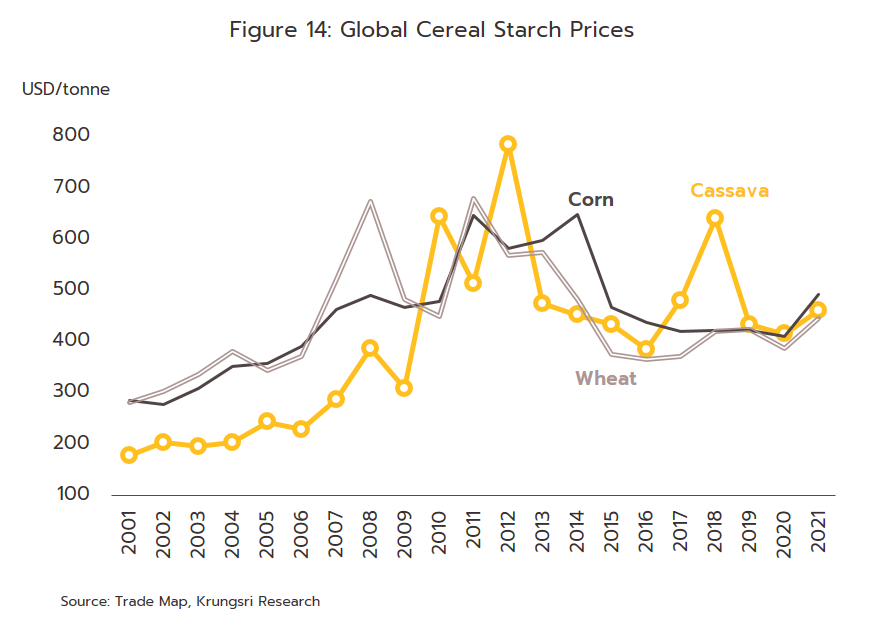

- Modified starch: Overseas sales totaled 1.14 million tonnes (+1.4%), and this brought in income of USD 956.4 million (+11.9%). Demand increased in Japan, South Korea and the US, with purchases used largely as an input into the food processing industry and in the production of sweeteners, paper, medicines, and cosmetics. However, weak economic conditions in export markets limited increases in sales (Figure 13), while demand was further undercut by stronger competition on price from starches produced from other inputs that have similar properties (Figure 14). Nevertheless, export prices still managed to climb 10.4% to an average of USD 839/tonne.

- Cassava pellets: Although in absolute terms, 2022 exports remained low at 0.078 million tonnes, which brought in earnings of just USD 22.1 million, this represents growth of 251.0% in volume and 243.0% YoY in value. Demand was boosted by the outbreak of war in Ukraine and the resulting increase in orders from the Netherlands, China, and Japan for cassava pellets to produce animal feed and to generate energy. Export prices also climbed 10.0% to an average of USD 346/tonne.

-

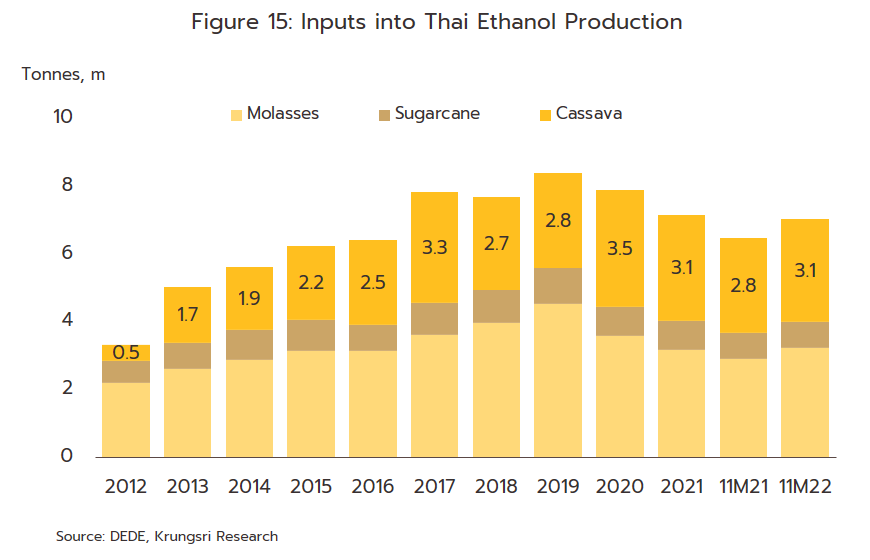

Domestic demand is strengthening on growth in downstream industries, most obviously for use in food processing and ethanol production. For all of 2022, demand for fresh cassava is therefore expected to top out at 14.2-14.5 million tonnes, up 15.0-17.0% from a year ago. Consumption of fresh cassava will be split between two groups. (i) Households and industry will absorb 10.9-11.1 million tonnes of fresh cassava (up 17.0-20.0%), with this being used in particular to produce alcohol and disinfecting products that contain alcohol. (ii) 3.35-3.38 million tonnes of fresh cassava will be used to produce energy. Demand will be pushed up 7.0-8.0% by domestic economic recovery, government support for the use of clean energy, for example through higher sales of E20 and E85 gasohol, and the switch by some ethanol producers to using cassava when faced with the rising cost of sugarcane and molasses (Figure 15).

-

Prices for fresh cassava jumped 22.0% to THB 2.52/kilogram through 2022 as demand firmed up on domestic as inputs in downstream production including alcohol, ethanol and energy productions and overseas markets. In the latter case, this was driven principally by the strength of demand in China, where cassava is being used to produce ethanol and animal feed in place of declining stocks of corn[14].

OUTLOOK

Demand for cassava will continue to strengthen over 2023 to 2025. Details of this are given below.

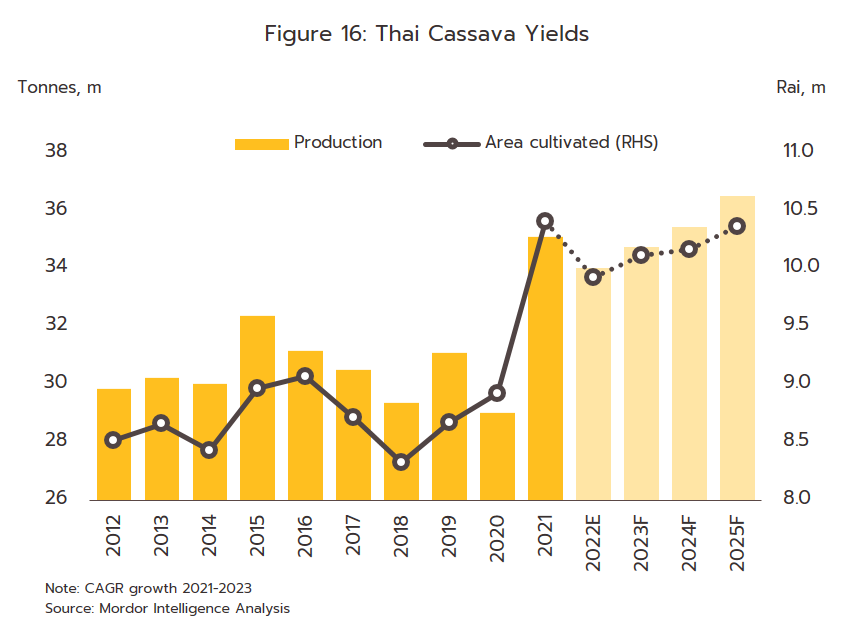

Production: Continuing high prices will mean that domestic cassava outputs should increase by 1.5-2.5% to 34.5-34.9 million tonnes of fresh cassava in 2023. Demand will be underpinned by the extension of the Russia-Ukraine war, which is sustaining ongoing worries over food security that are adding further to demand. Outputs are forecast to rise by another 2.0-3.0% in 2024 and 2025 to a total of 35.5-36.5 million tonnes of fresh cassava on: (i) likely favorable weather and access to irrigation water; and (ii) strengthening demand in downstream export markets (Figure 16). At THB 2.4-2.6/kilogram, average prices for fresh cassava should remain broadly unchanged in 2023, though over 2024 and 2025, lively export markets will lift these to THB 2.5-2.8/kilogram.

Domestic market: Demand for cassava products is forecast to rise by 3.0-4.0% annually, lifted by: (i) the easing of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic recovery, which will trigger a 2.0-3.0% annual increase in demand for cassava from the food processing industry; (ii) the government push to respond to growth in the tourism and transport sectors by supporting the use of gasohol E20 and E85, which will then increase demand for cassava-based ethanol by 3.0-4.0% per year; (iii) greater use of alcohol or alcohol-based products due to elevated worries over public health and hygiene; (iv) increased demand for fresh cassava, cassava chip, and cassava starch from ethanol producers in place of sugarcane and molasses, for which quantities may fall and/or prices rise.

Export markets: By volume, exports should strengthen by 2.0-3.0% per year over the next three years, and although growth will be restrained in 2023, this will accelerate over 2024 and 2025 with what is expected to be a brightening outlook for downstream industrial consumers in overseas markets (Figure 17). Details for individual segments follow.

-

Native starch: Annual exports are forecast to rise by 2.0-3.0% to 3.9-4.1 million tonnes as demand from industrial consumers rises, most notably from the food industry. However, producers will face a number of challenges arising from: (i) price competition from other similarly priced vegetable starches, though this will be especially so for corn flour, which has a 71% global market share by value; (ii) the possibility that China will increasingly swap out cassava for corn products (Figure 18); and (iii) increasing exports to China from the CLMV countries[15], where Chinese players have been investing in cassava farming and basic processing facilities.

-

Cassava chip: Overseas sales should grow by 1.0-2.0% annually to 5.8-6.0 million tonnes on greater demand from China that will be driven by: (i) continuing waves of COVID-19 infections that are stoking demand for disinfecting alcohol; (ii) economic growth, which will feed additional demand for ethanol from the construction and energy sectors; and (iii) increased demand for animal feed now that the outbreak of African swine fever is under control.

-

Modified starch: Exports will hit 1.2-1.3 million tonnes annually, which would represent average yearly growth of 3.0-3.5%. Sales will be lifted by an uptick in export markets in 2024 and 2025 and expansion in output by downstream industries, including medicines, cosmetics, food, paper, sweeteners, and textiles. Mordor Intelligence therefore estimates that the value of markets for starch derivatives and sweeteners will rise by 5.2% CAGR over 2022-2025[16].

-

Cassava pellets: Exports should run to around 0.15 million tonnes annually, and although demand will come for use as an animal feed and as a bioenergy source (especially from the Netherlands and Japan), markets will remain uncertain, and stronger demand will be limited to periods when alternative goods are in short supply, for example as a result of the Ukraine war or outbreaks of COVID-19.

In the coming period, players will tend to switch production to higher value-added products (e.g., bio-plastics and renewable bio-polymers) or cut marginal production costs by investing in the expansion of their clean-energy capacity (e.g., in ethanol production facilities or biomass power generation). However, competition over sourcing inputs is likely to intensify as demand for cassava rises in other industries, while exporters will have to contend with increased use of non-tariff barriers to trade that will likely include those focused on ESG goals (e.g., measures targeting products with water or carbon footprints).

[1] In Asia, cassava is used principally as an input to downstream industries rather than for human consumption. However, many countries have been moving to strengthen their food security, especially India, Indonesia and the Philippines, and in these countries, cassava has been promoted as an alternative to rice, while in Latin America, governments have promoted the commercial cultivation of cassava mainly for use as an input to industry.

[2] Data is from the Office of Agricultural Economics. Cassava can be grown in poor soils and is drought tolerant so it can be planted year-round, although in Thailand planting usually occurs between March and May for harvesting in the period from January to March in the following year.

[3] Data correct as of 2 October, 2022, though this does not include unregistered businesses, those that may have suspended or ceased operations, or those that have a size as determined by the Factory Act (No. 2). The data includes cassava processing facilities that output products including pellets, chips, starch, pulp and other goods (source: Department of Industrial Works).

[4] This does not include processing into cassava chip or other cassava-related businesses.

[5] Modified starch is made from native starch that has its physical and chemical properties altered through the application of heat, enzymes, and/or chemicals. This gives the modified starch particularly desirable qualities that then make it more useful in industrial applications, such as making its viscosity less variable, increasing its stability at a wider range of temperatures, and altering its acidity and shear strength.

[6] Equivalent to 5.8 million tonnes of fresh cassava.

[7] Producing 1 liter of ethanol requires 6.25 kilograms of fresh cassava.

[8] Producing 1 kilogram of cassava chip or pellets requires 2.42 kilograms of fresh cassava.

[9] Producing 1 kilogram of cassava starch requires 4.20 kilograms of fresh cassava

[10] The 2005 reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) encouraged member states to increase the area given over to crops that could be used as alternatives to imported cassava. In addition, prices for the latter were low, and as such, EU-based producers of animal feed switched from using cassava pellets to different products, most notably potatoes.

[11] China sources supplies of cassava for use in its food, energy, ethanol, and animal feed industries from overseas markets since Chinese farmers prefer to grow other crops (cassava growing imposes high costs, farmers benefit from only weak incentives, and it is difficult to mechanize production). In addition to domestic supply being unable to fully meet demand, the opening of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area means that importers benefit from favorable duties, though they are still liable for 9% VAT on fresh cassava and cassava chip, and 13% VAT on starch products. Given this, inputs of cassava to Chinese industry are largely imported (source: Thai Biz In China Business Information Center).

[12] To produce a nutrient profile similar to corn, animal feed is made by mixing 87% cassava chip with 13% soy pulp.

[13] As a result of reform of the EU Common Agricultural Policy, Thai exporters of cassava pellets switched to manufacturing cassava chip.

[14] The Chinese authorities have published an ‘Action Plan on Saving Food’ that calls for a reduction in the use of specified crops in the production of animal feed. Since 2018 this has resulted in farmers reducing their dependency on imports by growing soy in place of corn (the main input into ethanol production) and as such, stocks have dwindled.

[15] Chinese players have invested in growing cash crops and basic processing facilities in countries in the region, including Cambodia (rubber, acacia, cassava, and sugarcane), Lao PDR (rubber, sugarcane, corn for animal feed, bananas, cassava, teak and eucalyptus, with most investments being made in the north of the country in areas close to the Chinese border) and Myanmar (rubber, cassava, sugarcane, bananas and watermelons). Source: Chinese Agriculture in Southeast Asia: Investment, Aid and Trade in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

[16] This includes starches derived from corn, wheat, cassava, potato, and other sources. Source: Mordor Intelligence Analysis.

.webp.aspx)