The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting lockdown have hurt purchasing power of Thai and foreign patients this year, and we project private hospitals’ revenues would contract by 10.0-12.0%. Operations would recover in 2021-2022 underpinned by structural changes in Thai demographics including an aging society, urbanization, a growing middle-class, and rising health-awareness worldwide as individuals take greater interest in personal health and wellness.

On this note, hospital operators will likely invest to offer a more comprehensive set of integrated services to meet a wider range of needs. In this environment, private hospitals that are part of extended commercial networks will have an advantage in terms of operating costs, human resource, and access to a wider market. Stand-alone hospitals will need to increase competitiveness to address several challenges, including the entry of new operators.

Overview

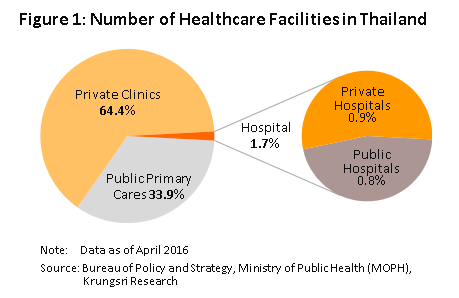

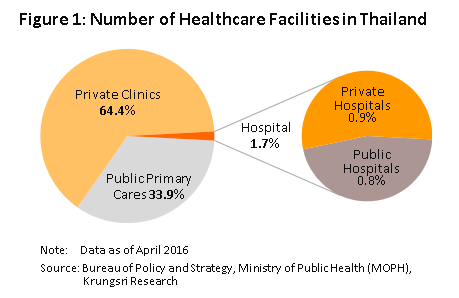

Thailand is home to 38,512 facilities that offer some form of healthcare services [1]. About 35% of these are state-funded (e.g. public health centers, district public health offices, and community and general hospitals), and the remaining 65% are private ventures (i.e. private clinics and hospitals). Divided according to size and range of medical services offered, 98.3% are classified as primary healthcare providers[2] (9,800 public health and district health promotion centers and 24,800 private clinics). The remaining 664 (1.7%) are secondary and tertiary healthcare providers, comprising 294 (0.8%) managed by the government, Ministry of Public Health, local administrative bodies, state enterprises or Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, and 370 private hospitals (0.9%; Figure 1).

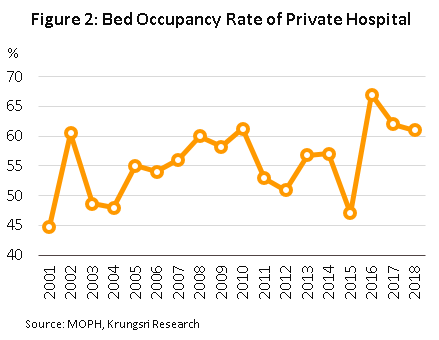

Although there are state hospitals dotted across the country, their capacity to serve patients is limited in some locations: (i) Bed occupancy rate3/ is high, and in some areas, it is close to or over 100%. Current bed occupancy rate is 126% in Loei, 100% in Mukdahan, 97% in Kanchanaburi, 94% in Pathum Thani, and 90% in Surat Thani. This means the supply of public hospital beds in some areas is insufficient to meet demand; and (ii) outpatients typically face long waits before being seen by a healthcare professional. The failure of the government healthcare system to meet rising demand has created an opportunity for private healthcare providers, which typically emphasize the speed and convenience of their services. This has prompted more middle-class consumers who have sufficient spending power to turn to private hospitals, despite them charging more than government hospitals for equivalent services.

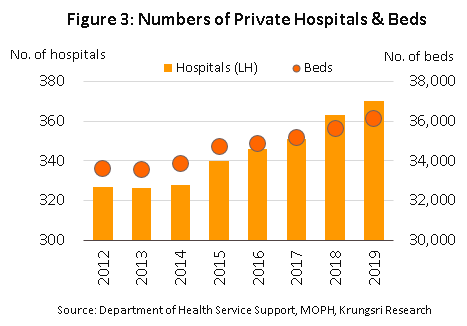

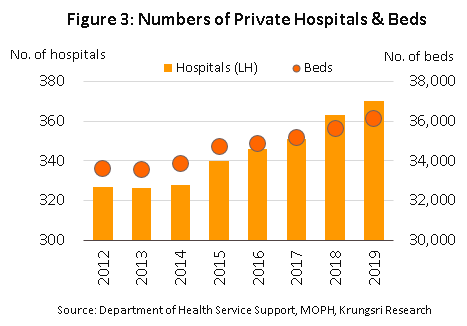

Currently, there is 370 registered private hospitals[4] in Thailand. 116 are in Bangkok (31.4%) and 254 in upcountry (68.6%). These hospitals house a total of 36,000 beds, including 14,000 in Bangkok and 22,000 in upcountry (Figure 3).

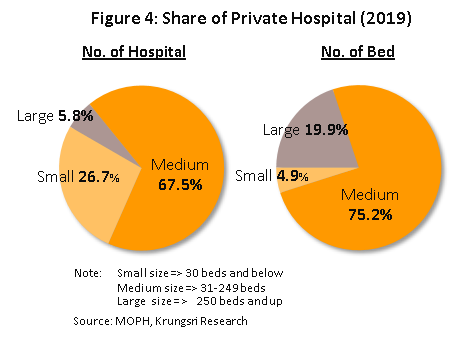

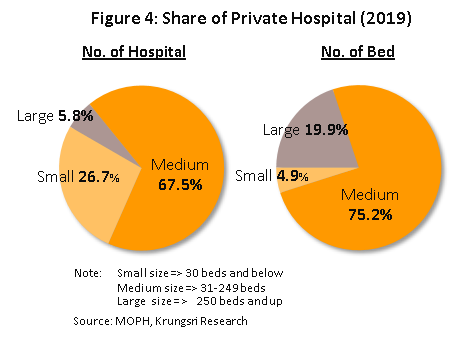

Private hospitals may be divided into three subgroups according to the number of registered beds. This is a good proxy to evaluate the range of medical services that each hospital offers (Figure 4).

- Large hospitals (more than 249 beds): Bangkok and the central region of Thailand have the highest concentration of mid- to high-income consumers. Hence, about 90% of large hospitals (5.8% of the total) are located in these areas. Currently, there are 22 large private hospitals in Thailand, and although this is only 6% of all private hospitals in the country, they offer a combined 7,162 beds, or 19.9% of all private hospital beds in the country.

- Medium-size hospitals (31-249 beds): There are 255 hospitals in this subgroup (67.5% of total) offering 27,069 beds (75.2% of total).

- Small hospitals (1-30 beds): There are 101 small hospitals in Thailand (26.7% of total) offering 1,766 beds (4.9% of total).

Private hospitals have benefitted from tax-exemption and other supporting government policies. In addition, business expansion has been driven by rising demand especially from patients in neighboring countries following the opening of the Asian Economic Community in 2015. The number of health and wellness tourists from further afield have also been rising steadily. These factors helped to stimulate a marked uptick in investment by private healthcare operators that has transformed the sector; large, dynamic operators have engaged in mergers and acquisitions, opened new hospitals in Bangkok and important regional centers, and bought into other private hospitals as investment and to extend their commercial networks. This led to the creation of several large commercial groups that operate private hospitals, including Bangkok Hospital Group, Thonburi Healthcare Group and Bangkok Chain Hospital (Kasemrad Hospital group). The mergers have increased their competitiveness, and the groups have their own clear target customer groups. And amid changes in the market structure, mid- and small-size operators have had to adjust their operations by specializing to target more niche markets.

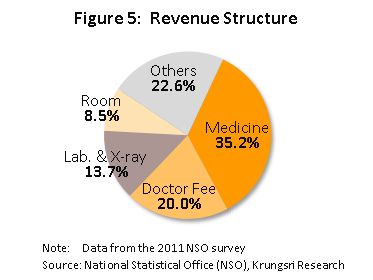

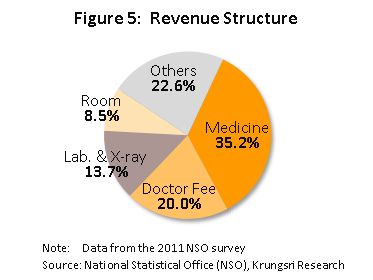

The largest share (35.2%) of private hospitals’ revenue is derived from the sale of medicines and pharmaceuticals. This is followed by medical treatment/services (20.0%), laboratory tests and x-rays (13.7%), accommodation fees (8.5%), and other revenues (22.6%) (Figure 5).

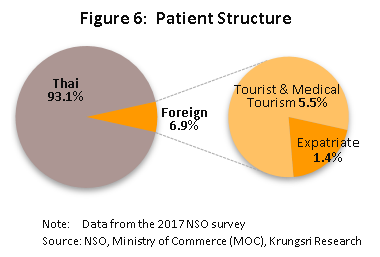

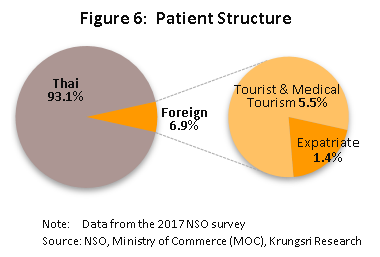

There were a total of 61.6 million patient visits[5] at private hospitals in Thailand (2016, latest data available). Of these, 58.8 million (95.5% of the total) were for outpatient services and 2.8 million (4.5%) were for in-patient treatment. The largest share were registered in Bangkok at 32.2 million (52.2% of total), followed by the central region (29.1%), the north (8.0%), the northeast (5.4%) and the south (5.3%). 93.1% of patients were Thai citizens and 6.9% were foreign nationals (Figure 6); the latter group comprised expatriates (1.4%) and general and medical tourists (5.5%)[6]. The foreign nationals were mostly from Myanmar, Japan, the Middle East and Europe.

The size of a hospital is important in determining competitiveness and profitability. Large hospitals tend to have stronger financial footing and will typically be part of an extended business network. This allows them to take advantage of economies of scale because the individual units within a commercial group will be able to pool resources, such as to make joint purchases of medical supplies and equipment to obtain lower pricing. They also provide services to a wide range of customer groups, so revenues are less volatile. And, they have larger capacity to absorb pressures arising from a changing business environment, compared to small- and medium-size competitors. Nevertheless, for all healthcare operators, the industry offers security and relatively low risk because healthcare services are a necessity and economic slowdowns affect healthcare services less than they do other sectors. This also means the operators are in a better position to pass on rising costs to patients. Indeed, revenues and profits of private hospitals listed on the stock exchange have been rising steadily in recent years.

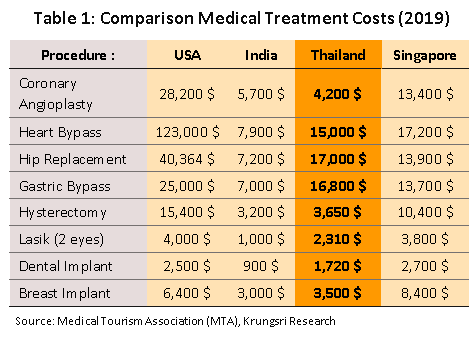

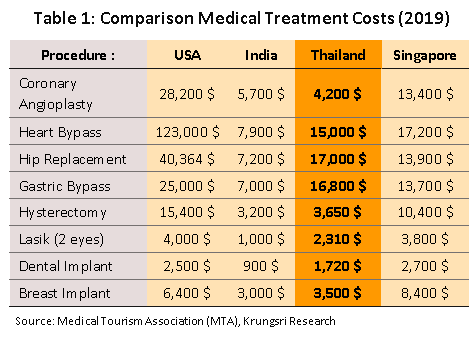

Since 2003, successive Thai governments have pursued the goal of establishing Thailand as a medical hub. This has been a major driver of the growth of the private healthcare sector and development of the medical tourism industry. It has pushed private hospitals to raise their standards and Thai healthcare services are now internationally-recognized for their world-class quality. The industry also benefits from competitive healthcare costs compared to other countries that offer services of a similar standard (Table 1). Thailand is also blessed with many tourist attractions which natural beauty makes them suitable for patients in recovery and long-term care. The country is now home to 62 institutions which are accredited by Joint Commission International (JCI) for meeting international standards. Thailand is in fourth place, behind the United Arab Emirates with 195 JCI accredited healthcare centers, Saudi Arabia (93), and China (84), but ahead of India (35), Malaysia (16) and Singapore (7). In 2019, foreign patients made 3.42 million visits to Thai hospitals, including 2.8 million for medical tourism and 620,000 by expatriates. These generated THB140bn revenue.

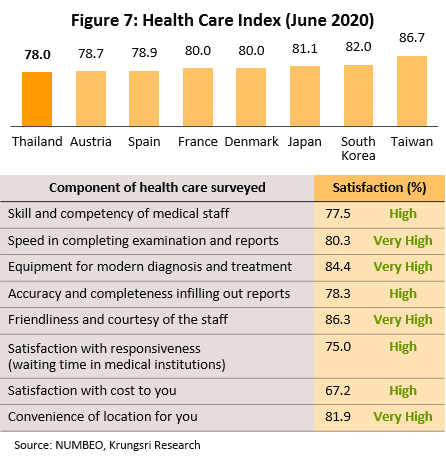

Indeed, in 2019, worldsbesthospitals.net declared one of Thailand’s hospitals among the five best in the world for medical tourism, CEOWORLD ranked the quality of Thai healthcare sixth in the world after Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Russia and Denmark. Numbeo (a website with access to the world’s most extensive database of cost of living and public healthcare systems) placed Thailand eighth in its world rankings for public healthcare systems (June 2020) (Figure 7).

The government will continue to support the healthcare industry under a strategic plan to develop Thailand into a global medical & wellness hub by 2026. Some of the priority segments are cosmetic surgery, anti-aging treatments, surgery, dental work and fertility treatments. The measures include: (i) extending the length of permitted stay in the country from 30 to 90 days for those seeking treatment (who may travel with up to 4 other people) who come from the CLMV countries or from China.

Access to medical services and public healthcare in Thailand

Access to medical services and public healthcare is a fundamental right. The state has an important role to play in establishing a healthcare system and facilitating access. The World Health Organization (WHO) stated that Thailand’s universal healthcare coverage (UHC) is one of the best models available for low-cost healthcare systems[8], even though per capita income in Thailand is relatively low compared to other countries with UHC systems.

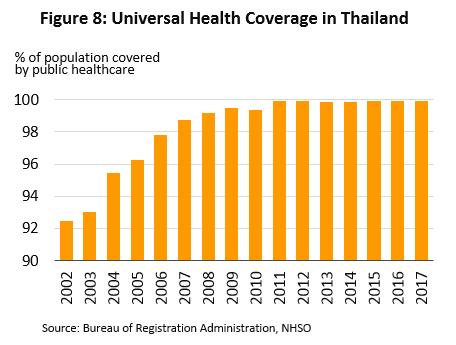

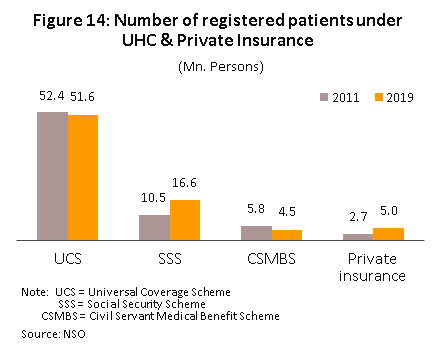

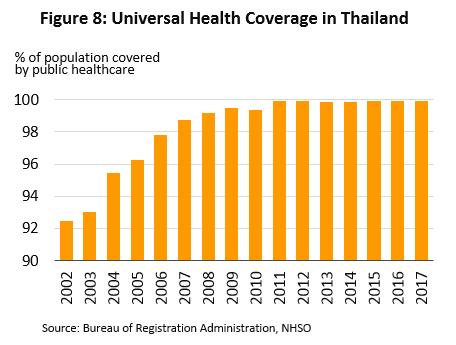

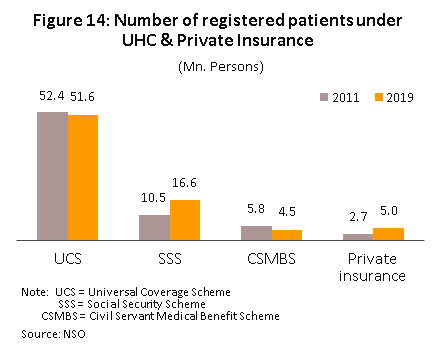

Thailand implemented the system in 2002 after enacting the National Health Security Act. Most recent data show 66.5 million people, or 99.92% of the population, are covered by this scheme (Figure 8). There are three funds which facilitate this: (i) Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS)[9]; (ii) Social Security Scheme (SSS)[10]; and (iii) Civil Servants Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS)[11].

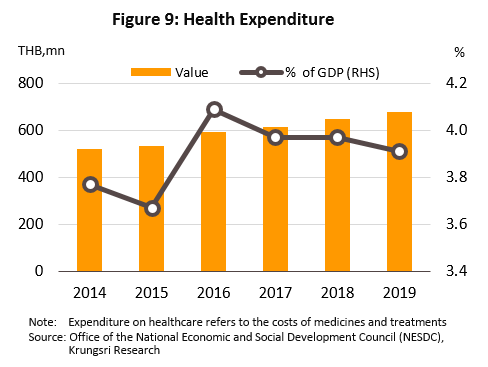

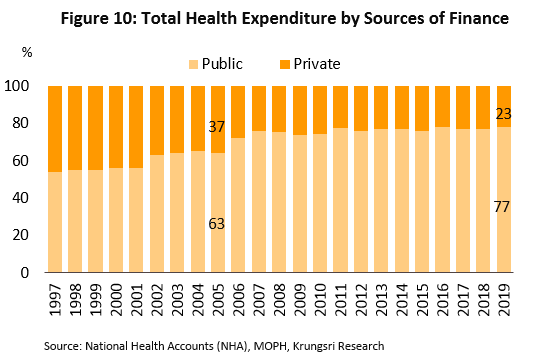

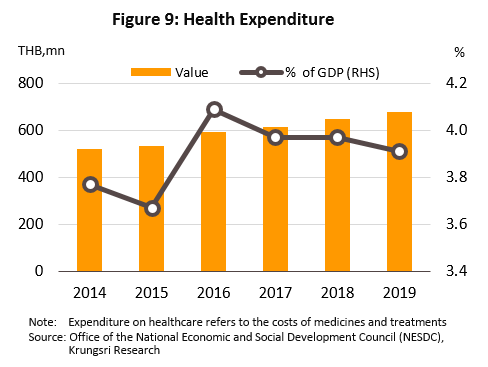

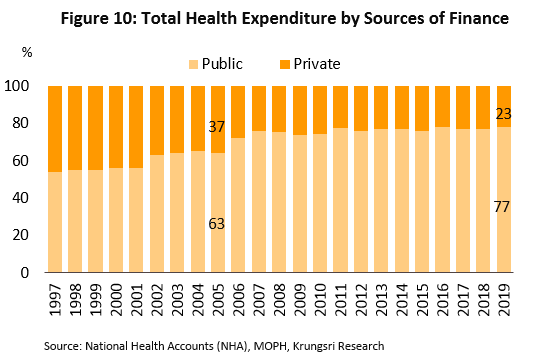

Since implementing the UHC, national healthcare spending has risen from 3.2% of GDP in 2001 to 3.9% in 2019 (Figure 9). 2019 data indicate 77% of this expenditure originated from public sources (Figure 10), while private sector contributions to the total had been falling. At the same time, the share of Thai households that experienced ‘catastrophic health expenditure’[12] has dropped from 5.7% of total households in 2003 to 2.3% in 2017.

There are plans to include patients from Japan, the US, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway; (ii) extending long-stay visas for visitors from 14 countries[13] from 1 year to 10; (iii) offering 30-day visa-on-arrival to those arriving for medical tourism; and (iv) offering dental and health-check packages to foreign arrivals. These measures helped to push private hospitals to capture more overseas patients, who typically spend more on healthcare than locals. This has steadily raised revenues and sustained healthy profits across the industry.

Situation

To increase market share and secure long-term growth, hospitals have been investing more to expand their premises, increase the range of facilities, establish centers for specialist and complicated treatments (to penetrate niche segments), and expand into overseas markets. Large hospitals that are part of wider commercial networks and have advantages in terms of costs and staffing, have been able to attract several patient groups, both domestic and international. But mid- and small-size stand-alone hospitals face greater challenges because their main source of revenue is mostly from the lower-middle income groups (with the exception of hospitals that participate in the social security system or that offer specialist treatment). However, mid- and small-size hospitals have the skills and expertise to raise capital through the stock market for working capital, to renovate their facilities, for business expansion, or to partner with large hospital chains. They have the ability to increase their competitiveness and broaden their revenue base.

Many large hospitals with potential have been expanding their commercial network. This includes developing existing premises, building new hospitals and clinics in regional centers, tourist locations, and border regions to meet demand from neighboring countries, buying shares (and securing board seats) in other profitable hospital groups (e.g. Bangkok Hospital is a shareholder in Muang Raj Hospital and Mayo Poly Clinic, Bangpakok Hospital has a stake in Sotharavet and Piyavate hospitals, and Ramkhamhaeng Hospital holds shares in Rajthanee Hospital), or buying shares in hospitals that pay healthy dividends (e.g. Bangkok Hospital bought shares in Bumrungrad Hospital). Some hospitals have formed partnerships with other healthcare providers both at home and abroad, to expand their network to receive or refer patients, or to develop new specialist market segments. Beyond this, some players are also generating additional income by developing new product lines, including pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, food supplements, and cosmetics, and running beauty clinics and care homes for the elderly. Some small and mid-size stand-alone operations have evolved into specialist treatment centers or established a solid income stream by offering treatments to patients covered by the social security system. Overall, the private healthcare sector in Thailand is just as competitive as any other sectors of the economy.

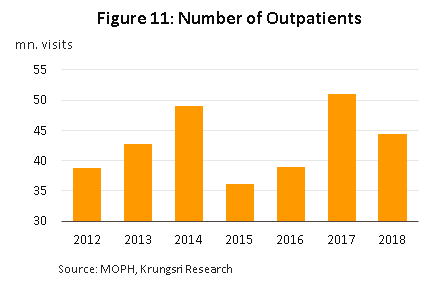

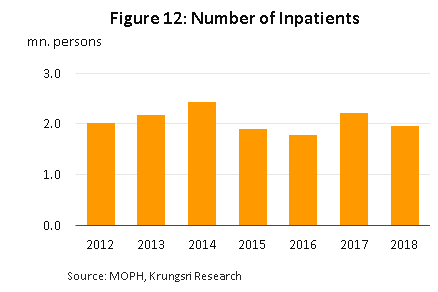

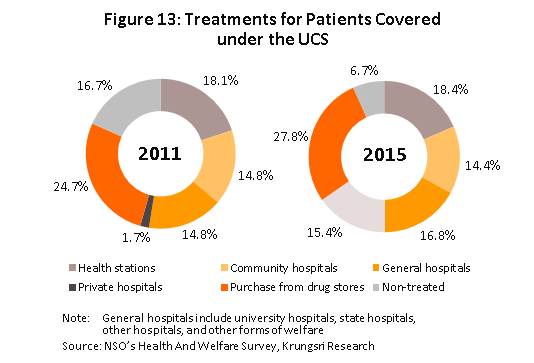

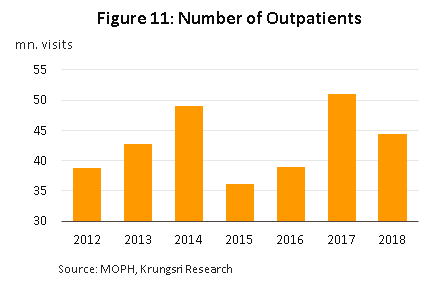

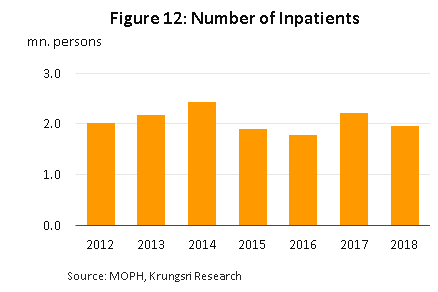

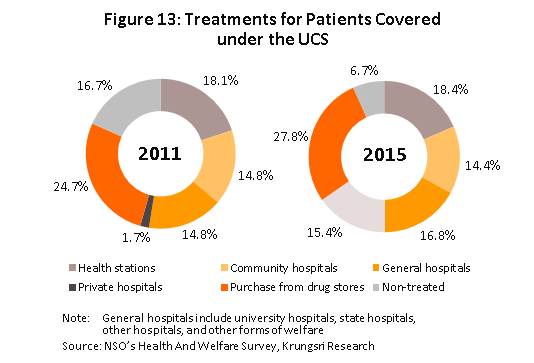

But since 2015, private hospitals have had to deal with the effects of slowing economic growth. This has affected middle-income consumers, who are the hospitals’ main customer group. For several years, this group has been cautious about spending on healthcare. The number of people seeking treatment in hospitals has fallen significantly (Figure 11 & 12) and healthcare expenditure has dropped as individuals purchase medicines from pharmacies, seek treatment in government-run hospitals or cheaper private-sector clinics (Figure 13), or postpone treatment altogether for less urgent/serious conditions. Most hospitals have responded to this by marketing their services to those who qualify for private or state-backed health insurance, the numbers of which have been rising steadily (Figure 14). However, employing pricing strategies and selling healthcare packages to attract customers have stoked greater competition.

At the same time, hospitals that target foreign patients were also being pressured, especially hospitals that target patients form the Middle East, where weak oil prices have been pressuring state budgets. The United Arab Emirates has slashed government subsidy for overseas hospital treatments from 90% to 50%, and the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait are reducing demand for overseas treatment by building their own modern, fully-equipped hospitals. In response to falling demand in traditional markets, private hospitals have developed new markets that comprise high-income earners from China, Russia, Africa and the CLMV nations. Their efforts have been successful and have helped to sustain the growth of the medical tourism industry. The Tourism Authority of Thailand estimates an average of 2 million visits annually to Thailand are for medical tourism[14].

The Ministry of Tourism and Sports reported medical tourism generated THB32bn revenue in 2018, an 18% increase on 2017 figure. The most popular treatments sought by medical tourists are health checks, surgery, dental work and anti-aging treatments. These have been steadily pushing up patient numbers and revenues.

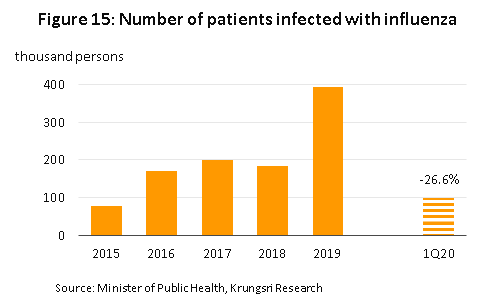

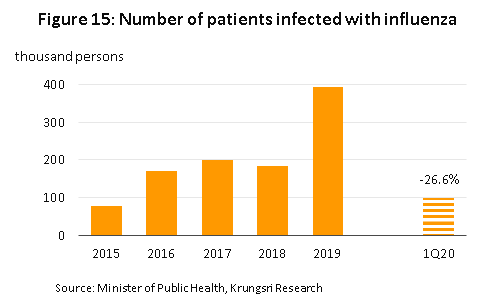

In 2019, weaker consumer spending power continued to affect the industry. Annual revenue growth for hospitals listed on the stock market slipped to +7.2% from an average of +10.8% in 2014-2018. However, the industry continued to be buoyed by: (i) a 35% increase in the number of patients infected with notifiable diseases relative to a year earlier, with a sharp rise in influenza (up 114%) (Figure 15) and dengue fever (up 49.5%); (ii) a 3.6% rise in the number of people covered by the social security system, which benefited hospitals that serve large numbers of social security patients (79 private hospitals are part of this scheme); (iii) the continuing development of the medical tourism segment, with patient numbers and revenue rising in the year[15]; and (iv) the creation of new income streams through the development of new integrated healthcare services that offer a mix of traditional and preventative treatments. Bangkok Hospital opened the Mövenpick BDMS Wellness Resort Bangkok, World Medical Hospital opened the Oasis Wellness Center, and Praram 9 Hospital now runs the W9 Wellness Center. Some operators have opened new hospitals overseas (e.g. Thonburi Healthcare Group opened Ar Yu Hospital in Myanmar in March 2019).

In the first half of 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic caused a crash in the number of people seeking treatment in hospitals, driven by fears of getting infected and to comply with social distancing. Many had delayed or postponed non-urgent hospital visits. In 1Q20, the number of patients reported to have a notifiable disease shrank by 19.5% YoY[16], with cases of dengue fever and influenza falling by 42.0% and 26.6%, respectively.

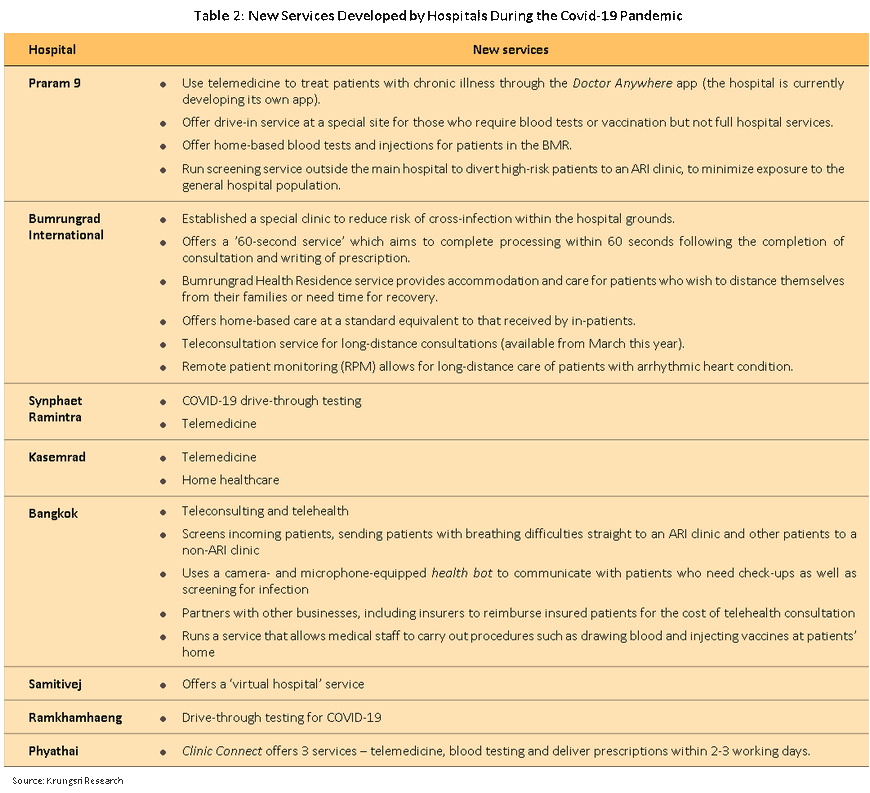

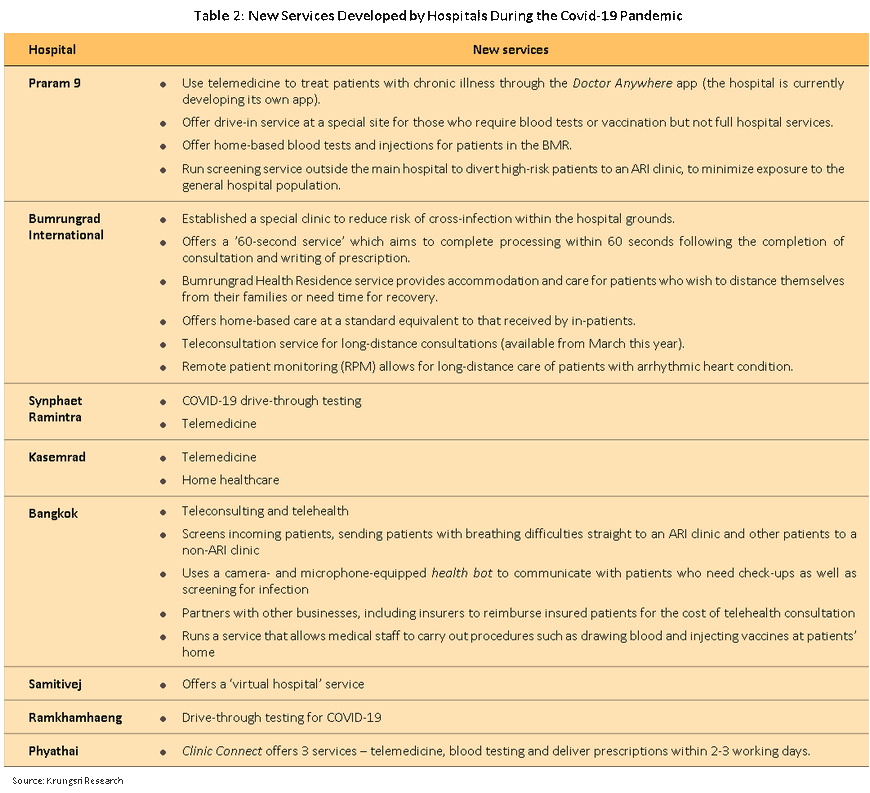

The number of foreign patients (business people and medical tourists), particularly those from China, also slumped because of the lockdown first in China and then worldwide. Large hospitals that were heavily dependent on receipts from foreign patients saw revenues tumble. For mid-size and small operations that treat patients who are covered by the social security scheme, revenues dropped by a much smaller magnitude. However, across the industry, hospitals are now focusing on the domestic market and have adjusted their service offerings to make up the lost revenues. For example, they are offering telemedicine and 24-hour online consulting services, Covid-19 drive-through testing, home visits for blood tests and injections, and health residences (Table 2).

Results of a Survey of Medical Tourism in Thailand

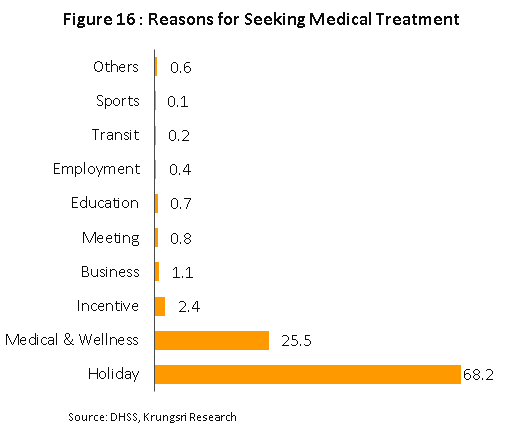

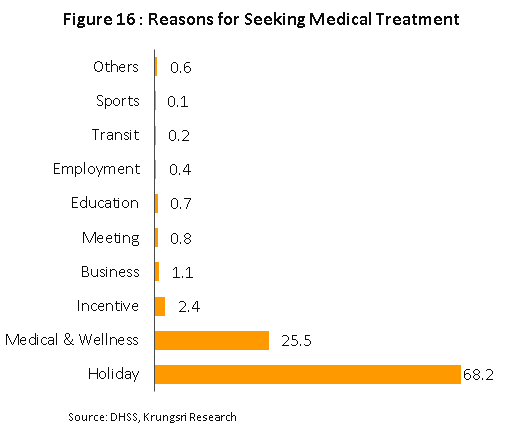

In 2019, the Ministry of Public Health conducted a survey of foreign tourists who had received health/medical care in Thailand. Among the respondents, the five largest groups were from China (4.6%), Myanmar (4.2%), Lao PDR (2.3%), South Korea (1.1%) and Japan (0.8%). The results of the survey are summarized below.

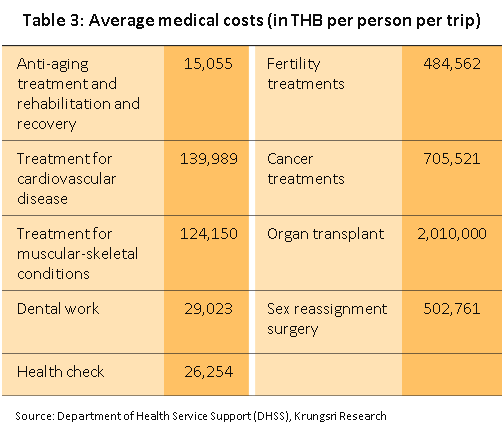

- The Ministry of Tourism and Sports estimates that in 2019, 630,000 travelers came to Thailand for medical treatment and spent THB120bn, up 8.5% from 2018 figure. Average spending was THB254,202 per person per trip (over five-times higher than spending by general tourists), and 72.3% of this or THB183,858 was for medical expenses.

- The major factors that influenced the decision to seek treatment in Thailand were: (i) relatively low healthcare cost in Thailand compared to countries that offer similar standards of medical care (85.5%); (ii) reputation of Thai hospitals (84.3%); (iii) reputation of Thai doctors (77.7%); (iv) recommendation by a doctor in their home country (76.2%); and (v) recommendation by an advisor or representative of a healthcare provider (40.5%)

- The major healthcare providers were private hospitals (92.7%), followed by public hospitals (4.7%), general clinics (1.5%) and specialist clinics (1.1%).

- 41.7% of respondents said Thai healthcare facilities offered good value for money, 24.3% said it was extremely good value for money, 31.2% said it was moderately good value, and only 2.8% said they were not worth the money spent.

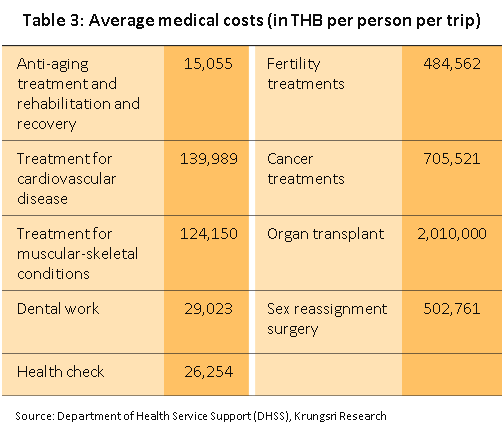

- The most commonly sought services were health checks (50.2%), muscular-skeletal treatments (8.6%), cancer treatment (8.4%), treatment for cardiovascular diseases (4.1%), and dental work (4.1%) (Table 3).

- 87.3% of respondents paid for their treatment themselves, 9.0% were covered by health or accident insurance, 1.0% by their social security system, and 0.8% by a government welfare program. Healthcare costs for 66.7% of Japanese tourists were covered by health or accident insurance.

- Brief profile of medical tourists from several countries:

- China: 81.3% sought services in private hospitals and 18.8% sought treatment in public hospitals. The most commonly sought services were fertility treatments, treatment for muscular-skeletal conditions, dental work, sex reassignment, anti-aging treatments, and rehabilitation and recovery.

- Malaysia: The most commonly sought services were health checks (35.0%), dental work (25.0%), treatment for cardiovascular diseases (10.0%), and treatment for muscular-skeletal conditions (10.0%).

- South Korea: The most commonly sought service was sex reassignment (60.0%).

- Lao PDR: All visitors came for health checks

- Japan: Japanese visitors came for anti-aging treatment, rehabilitation & recovery, sex reassignment, and health checks in equal proportions.

Industry Outlook

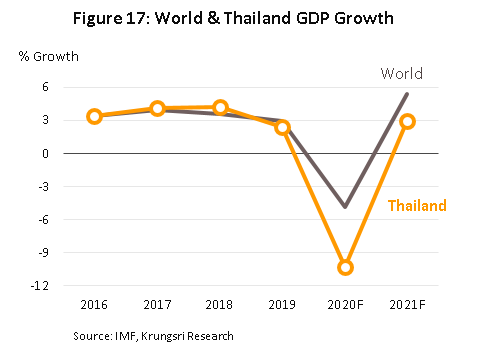

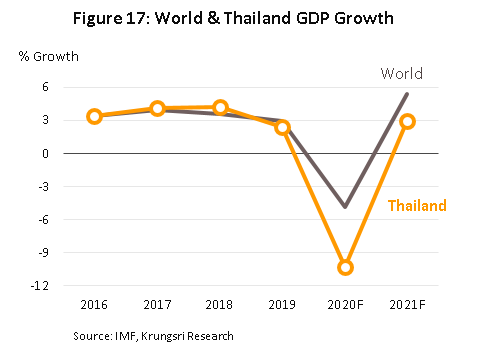

In 2020, private hospital revenues are projected to drop by 10.0-12.0% because of the Covid-19 impact. The IMF forecasts the world economy will shrink by 4.9% this year, while Krungsri Research sees the domestic recession knocking 10.3% off Thai GDP, the worst projection since the Global Financial Crisis in 2009 (Figure 17). This had already caused a sharp drop in consumer spending power in the first half of the year, when uptake of hospital services crashed. But in the second half of 2020, the situation should improve mildly led by (i) reopening of economic activities, which could encourage consumers to seek hospital services again; (ii) the move to gradually allow foreign visitors (including medical tourists) to enter the country, although this is likely to be limited to about 30,000 foreign patients[17] initially. Many hospitals are also generating additional income by registering as ‘alternative hospital quarantine’ facilities; and (iii) other positive factors, including an increase in the ceiling for medical treatment costs by the Social Security Office (effective January 1, 2020), which will boost revenues for hospitals that participate in this scheme. However, private hospitals that are heavily dependent on revenues from overseas patients would see a slow recovery in patient numbers and revenues.

In 2021 and 2022, prospects for private hospitals should improve significantly. This is premised on recovering consumer spending power and the number of medical tourists returning to pre-pandemic level, probably near the end of 2021. Revenues would grow by an average of 4.0-5.0% per year, supported by the following:

Structural changes to support greater demand for healthcare will include the following.

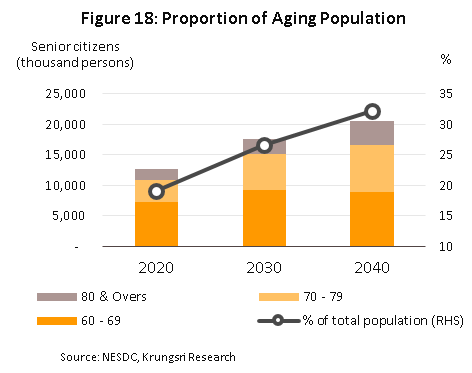

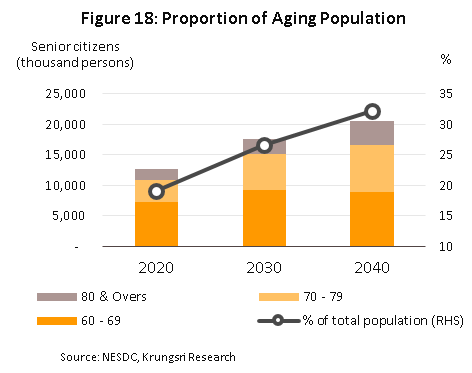

- An aging Thai society: This will boost demand for more complicated and technologically-intensive medical interventions. The Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council forecasts Thailand will become an ‘aged society’ - where more than 20% of the population are aged over 60 - by 2021. By 2040, this will rise to 32% (Figure 18) and about 60% of the elderly would have some kind of health problem[18]. And, the TDRI expects that by 2032, expenditure on healthcare for the elderly will rise three-fold compared to the base case, implying that as society ages, health costs would rise disproportionately. There would be a larger number of people with circulatory disorders, diabetes, and chronic breathing problems.

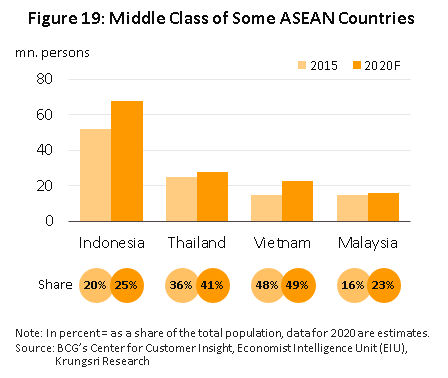

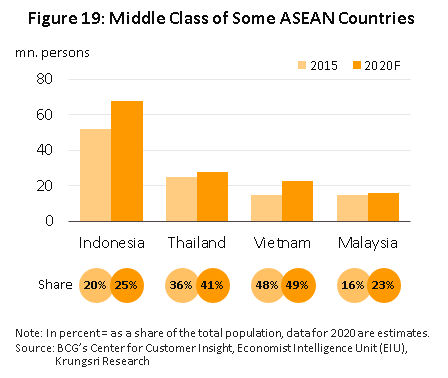

- A growing middle-class: In 2020, about 41% of the population will be middle-class compared to 36% in 2015. This expansion and their rising spending power[19] will increase demand for services provided by private hospitals. There is also a growing middle class population across the ASEAN zone (Figure 19), which would create opportunities for Thai healthcare providers.

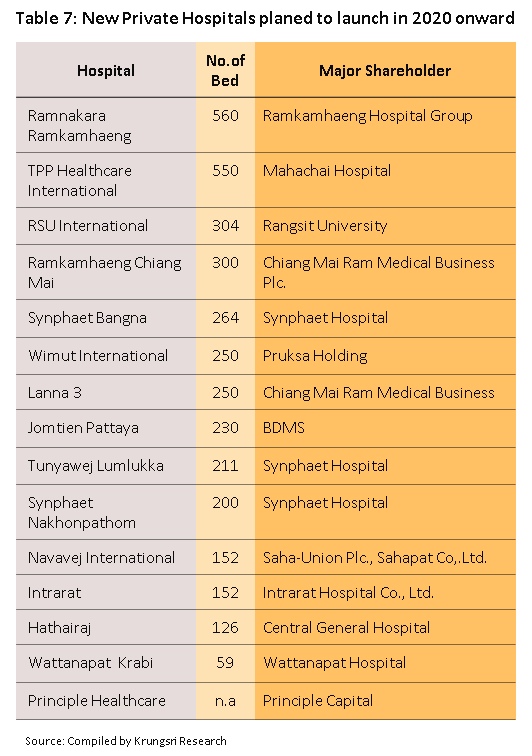

- Urbanization: The United Nations projects urbanization rate in Thailand will climb from 50.4% in 2015 to 60.4% by 2025 (Figure 20). Coupled with several government policies including the extensive build out of new infrastructure, establishment of special economic zones (SEZs) and the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), these will create opportunities for operators to generate additional income by meeting rising demand in the SEZs, the EEC, and surrounding areas. The rising number of foreigners who invest in or work in these locations will also create a new market for healthcare providers. For example, Ramnakhra Hospital will open in 2021 on Sukhapiban 3 Road to meet anticipated new demand for healthcare services in eastern Bangkok and the EEC.

Factors that could affect the health of the Thai population

- Infections with a notifiable disease, new diseases, and the resurgence of recent diseases: The Department of Disease Control estimates that in 2020, around 140,000 people will be infected with a notifiable disease such as dengue fever. And the country could see a resurgence of recent diseases such as SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome, first reported in 2003), H5N1 bird flu (first reported in 2004) or the H1N1 flu (first appeared in 2009, and returned between October 2019 and February 2020 in Taiwan), as well as the emergence of new diseases such as Covid-19 (first appeared in December 2019 and continues to spread). The Red Cross Society claims there are an estimated half a million unknown viruses that could mutate and infect humans.

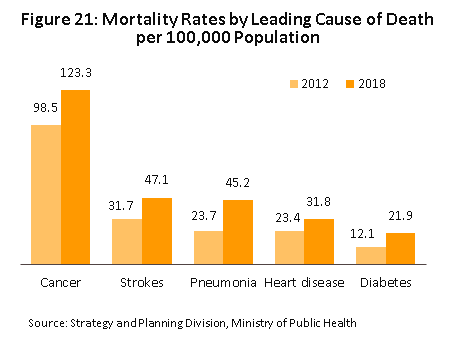

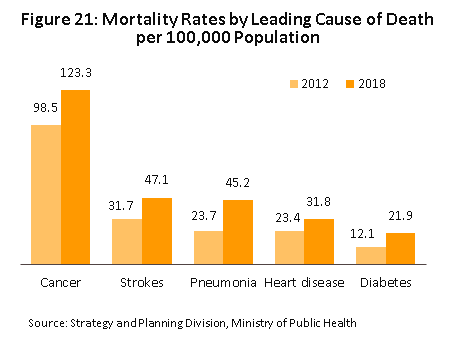

- Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)[20]: The rate of illness and death from non-communicable diseases (e.g. cancer, stroke, pneumonia, heart disease and diabetes) is rising among the Thai population (Figure 21). The Ministry of Public Health claims about 400,000 people die annually from NCDs (2018), and that NCDs in the working-age population generate at least THB200bn[21] losses to the economy annually. Risky behavior is increasing; in 2019, consumption of alcoholic beverages rose by 4.5%, smoking (cigarettes) increased by 1.5%[22], and consumption of sugar was almost five-times higher than the recommended safe levels. There are also conditions which are becoming a concern - ‘computer vision syndrome’ which can be caused by spending more than two consecutive hours on a computer or digital device.

Private-sector responses and public-sector support

Hospitals are trying to penetrate new markets by investing in the development of comprehensive supply chains.

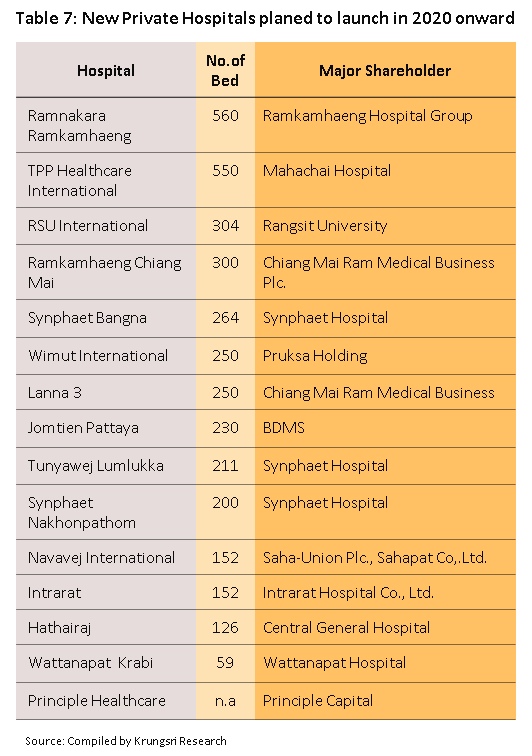

- Meeting increased demand by expanding existing sites and building new branches in Bangkok and upcountry: Bangkok Hospital plans to expand from 49 branches in 2019 to 50 by 2023, and construct new facilities named ‘Bangkok International Hospital’. Bumrungrad Hospital will open a branch on Phetchaburi Tad Mai Road this year. Kasemrad Hospital will open a branch in Aranyaprathet (this year) and Principal Healthcare has ambitious plans to expand from 10 branches in 2019 to 20 by 2023, mostly in second-tier cities. Many mid-size operators are also working with partners to conduct joint-expansion; Synphaet Hospital has tied up with Ramkhamhaeng and Vibhavadi hospital groups to develop the Phatthanakan and Amata branches of Vibharam Hospital.

In addition, some hospitals are in joint-ventures with local players upcountry, especially in the EEC where demand for healthcare services is forecast to rise. Krungsri Research estimates that between 2020 and 2022, the supply of in-patient facilities will increase by at least 2,000 beds nationwide.

- Partnering with other hospitals to penetrate new, high-potential markets: Hospitals may benefit from participating in a patient referral network. For example, Praram 9 Hospital works with nine hospitals upcountry to refer patients with kidney problems, and Bumrungrad Hospital has partnered with 58 healthcare providers across the country to establish ‘centers of excellence’ in partner hospitals which have the potential to engage in joint operations. This helps to expand their customer base to include middle-income earners and those who have private health insurance. These partners need to meet a level of investment, expenses, resources, revenue and supply chain management that would enable them to set prices for their services that are suitably competitive. Earlier this year, Ramkamhaeng Hospital also expanded their branch network upcountry with the acquisition of shares in Thonburi Hospital Group.

- Developing competitiveness by establishing a unique value proposition: This applies especially to the increasing use of technology and new innovation to treat illnesses, for example, by using robotic assistants in surgical procedures and establishing centers of excellence to attract domestic and international patients. The latter might include setting up comprehensive cancer treatment centers and selling packages for a course of treatments, or developing the organization as a healthcare leader, like how Bumrungrad Hospital has set a goal to become a world-class holistic healthcare provider by 2022.

- Expanding upstream and downstream into non-hospital businesses: This include manufacturing medicines, providing medical laboratory services, producing food supplements and medically-approved food, running pharmacies, health centers and care facilities for the elderly, and selling beauty products and operating beauty clinics. Moving into these separate but related areas will help private hospitals develop more comprehensive supply chains, connect to a wider range of consumer groups, and help them to broaden and grow their sources of income over the long term.

- Partnering with other types of business: Hospitals may tie up with real estate developers, life insurers, and hotels. Bumrungrad group has tied up with MK Real Estate Development and Minor International to invest in an anti-aging and preventative healthcare clinic (scheduled to open in 3Q20).

Increasing the share of and types of foreign patients being treated: New markets with significant growth potential include the CLMV region, China, Russia and Africa because healthcare services often fall short of consumer expectations there. This creates an opportunity for Thai hospitals to respond to untapped demand, a move that would also reduce their reliance on a single customer group. In pursuit of this strategy, many hospitals have opened fertility clinics to appeal to the Chinese market, where many couples seek IVF treatment to conceive a second child.

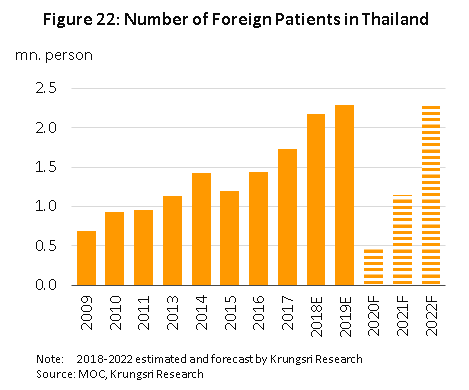

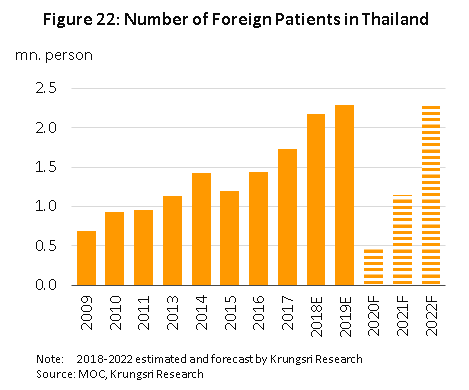

Thonburi Healthcare opened Thonburi Bamrungmuang Hospital in 2019 to appeal to foreign and medical tourists. Many other hospitals are expected to follow suit. This would lead to a steady increase in the number of foreign patients coming to the country for treatment (Figure 22). Allied Market Research estimates the market for medical tourism in Thailand will grow by an average of 13.7% p.a. during 2018-2025. Looking ahead, Thai healthcare operators are also expected to expand their network overseas by building their own hospitals, forming joint-ventures with local partners, or setting up an agency to refer local patients to Thai facilities. They include Thonburi Hospital’s new hospital in Lao PDR (a joint investment with Chinese players), Myanmar and Vietnam, Kasemrad Hospital’s new Kasemrad International Hospital Vientiane in Lao PDR (opening in 2021), and Ramkamhaeng Hospital’s 70% stake in Vientiane International Hospital, also in Lao PDR (opening in 2022).

Government support for the industry included the following:

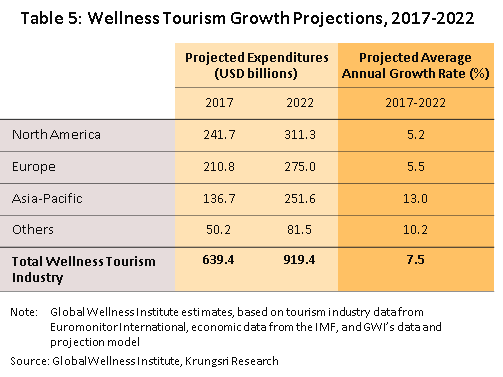

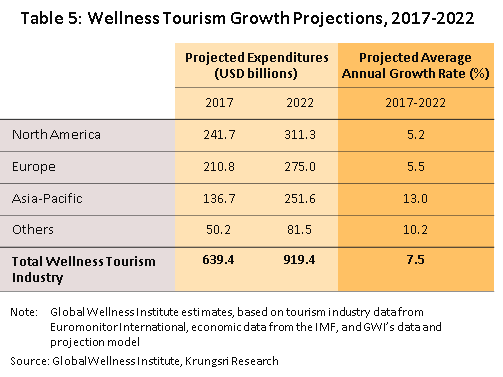

- Promoting Thailand as an international healthcare hub: This strategy is aligned with rising interest worldwide in medical tourism. The Global Wellness Institute estimates that in Asia, the market for medical tourism will grow by 13% annually (Table 5). Additionally, to help attract more foreign patients, the government is trying to raise standards to internationally acceptable levels in the areas of cosmetic and beauty treatments, sex reassignment, treatments for knee and heart disorders, fertility treatment, and dental work. There are also efforts (now successful) to have Thai massage recognized as an intangible cultural heritage. From now to 2024, The Tourism Authority of Thailand will promote the country as the ‘medical and wellness resort of the world’.

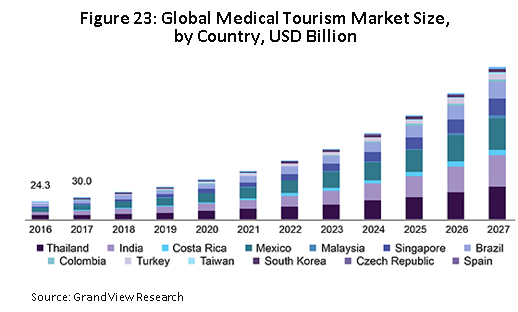

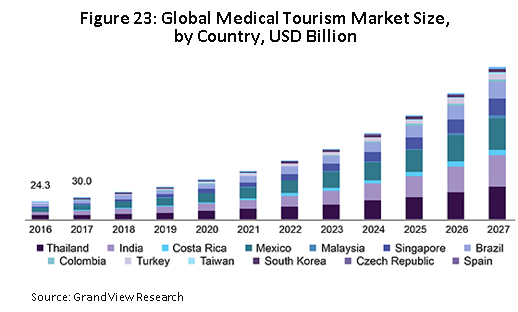

They are trying to achieve this through several programs: (i) ‘Telemedicine for overseas Thais’, which aims to help Thais living overseas receive medical and beauty treatment in Thailand. This is expected to generate THB80,000 per person; (ii) ‘global health insurance companies’, to increase uptake of Thai healthcare services by civil servants in Myanmar, Lao PDR, Cambodia and the Middle East; (iii) ‘online health’, which focuses on visitors seeking healthcare and beauty treatments arriving from Myanmar, China and the Middle East; the services are promoted on the online marketplace; (iv) ‘hotelistic’ (a portmanteau of hotel and holistic), which promotes health services such as health checks and checking for toxins in patients and removing these in-situ at tourist hotels or wellness centers; and (v) ‘agent/media outreach’, which aims to establish Thailand as a global ‘top of mind destination’ for medical and wellness tourism. Rising interest in personal health and wellbeing is also prompting hospitals to venture into the wellness industry. These include the BDMS Wellness Clinic (Bangkok Hospital), Vitalife Wellness Center (Bumrungrad Hospital, expected to open this year), and Medical City (Thonburi Hospital). Combined, these measures will support the ongoing growth of the medical tourism industry in Thailand over the long term (Figure 23).

- Designating Thailand’s medical industry and ‘medical hub’ status as ‘new S-curve’ industries: The government has offered a range of incentives (including generous tax breaks)23/ to attract overseas players to invest in Thailand. That includes setting up facilities for the research and development of medical innovation and pharmaceutical products. This could help private hospitals to cut costs, increase their competitiveness against overseas players, and strengthen related industries in the area of medical tourism. In April this year, the government responded to anticipated new demand for medical equipment created by the Covid-19 pandemic by introducing more investment support measures.

As a result, in 1H20, there received 52 applications (+174% YoY) for investment support for projects related to the medical industry with a combined value of THB13bn (+123% YoY). Within the EEC, the government has also given the green light to Thammasat University’s new EECmd project in Pattaya, which will be home to medical innovation and an important part of the medical hub strategy. Several parties have expressed interest in investing in the project, including Japan’s Mizuho Bank, which will offer loans to customers who invest in the healthcare industry in the area, Chinese players looking to establish a center for research into traditional Chinese medicine in the ASEAN zone, and a Taiwanese clinic for the elderly. Beyond this, there will also be an international health center that specializes in medical genomics, and there is support for private-sector investment in the construction of a new hospital to meet rising demand for healthcare services from those working in industrial estates in the area.

However, there are lingering challenges for the industry, including the following:

- Shortage of doctors and other medical staff: The World Health Organization recommends 2.8 doctors per 1,000 population. But in Thailand, it is only 0.4 per 1,000 population, significantly lower than in Singapore (1.92) and Malaysia (1.2). The rising number of private hospitals would increase competition for doctors and other medical staff, and push up operating costs.

- Government regulations: The inclusion of pharmaceuticals, medical supplies and fees charged for medical care on the list of controlled prices means hospitals have less room to raise charges. This will affect stand-alone, small and mid-size operations the most. These players are normally more dependent on revenue from patients covered by the social security system, and so any changes to funding regulations would affect their operations.

- Thai private hospitals lack competitiveness: The Fiscal Policy Research Institute awarded Thai hospitals a total of just 4.31 points, after market leaders Germany (7.0 points), the US, Japan and Singapore, although Thailand performed better than Malaysia and India. Relative to its competitors’ average scores, Thailand’s worst scores were for technology and innovation, business environment and strategy, and productivity. Thai private-sector hospitals achieved mid-level score for readiness to enter the ‘industry 4.0’ era. Unfortunately, the worst scores were for strategic readiness and investment. And over the next 5 years, operators need to concentrate their efforts to overcome shortfalls in these two areas.

- Rising competition in the healthcare industry: There is rising competition not only from other private-sector hospitals, but also from outside the industry. (i) Hospitals are increasing investments, especially upcountry. This includes government hospitals which have raised service standards to match those in the private sector. They also enjoy advantages with regard to their reputation, use of technology, and expertise of their staff (e.g. Siriraj Piyamaharajkarun Hospital, part of the Siriraj group of hospitals, and Ramathibodi Hospital’s Somdech Phra Debaratana Medical Center). (ii) Major investors from other economic sectors such as real estate, are showing more interest in the industry. This is because, against a background of rising awareness about personal health, investing in private hospitals opens up the possibility of securing recurring, long-term revenues. (iii) Overseas investors (especially from China) are interested in opening healthcare centers. They include fertility clinics to meet rising demand from Chinese couples which are seeking treatment in Thailand. (iv) Many other countries, particularly in the ASEAN region, have also laid out plans to develop their respective medical tourism industry. In many cases, these plans depend on attracting the same customers as Thailand. Thus: (a) Singapore has established its own medical hub to attract medical tourists (largely business people) from within the country as well as neighboring countries. This year, Parkway Pantai (a Singapore-based healthcare provider) opened a 250-bed hospital in Myanmar; (b) in Malaysia, major hospitals and medical centers are focusing on the Muslim market and attracting patients from Indonesia; (c) India is attracting foreign patients with its low treatment costs; (d) China has plans to develop Hainan Province as a hi-tech center for medical tourism targeted at Chinese citizens who might otherwise travel abroad for medical treatment, while large international healthcare operations are also investing in China (e.g. investments by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Cleveland Clinic, the latter in a new hospital in Shanghai); and (e) the UAE plans to become a medical hub to serve patients from Russia, China and the Gulf.

There is intensifying competition in the global medical tourism industry. If operators do not actively respond to the changing landscape, Thai private-sector healthcare providers would lose market share in the near future.

- Other factors: Digital and technological transformation is having a larger impact on hospitals. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, consumer behavior have changed and consumers are willing to pay a premium for hygiene and cleanliness. In addition, the success of the Thai public healthcare system in rapidly containing the spread of Covid-19 and gaining worldwide recognition for this, may also increase demand for medical tourism services in the country.

The combined impact of the challenges outlined above could limit growth if operators are unable to adapt quickly and appropriately. Failure to respond to potential problems could cause hospitals to lose customers to competitors. Operators may also need to invest more in technology. So in the coming period, partnerships between hospitals will become more popular as players seek to cut costs, increase competitiveness, and adjust business strategies. This will put hospitals in a better position to address rising competition and seize new opportunities.

Krungsri Research’s view

Revenues will drop sharply across the industry this year. But in 2021 and 2022, they should recover along with demand from domestic and international patients. However, general clinics and small and mid-size hospitals will be at a disadvantage; some may be forced to cease operation or be swallowed up by larger domestic or international players that are expanding horizontally and vertically.

- Large private sector hospitals, specialist hospitals and medical centers, specialist diagnosis and treatment clinics, and care centers and care homes for the unwell and the elderly: These will continue to growth at a healthy rate because the players are prepared to provide high-quality care. And there is rising demand, mostly from the middle- and upper-income groups or individuals who need special care (especially elderly patients with chronic or complicated conditions or who need specialist, technologically-intensive intervention). In addition, at this end of the market, the quality of service is equal to or better than that offered by competitors in other countries, but fees are lower. This is important to attract foreign patients, who comprise a significant share of revenues for some hospitals. Ongoing investment to expand branch networks and service offering will also enable players to capture specific target groups which would add to or diversify their income streams.

- Small and mid-size hospitals (especially stand-alone operations): Earning will improve slowly in this segment. Operators will likely remain loss-making or lack investment funds (for example, to address shortage of equipment or staff) for an extended period. This will force some players out of business or lead to their being acquired by larger operations. To make matters worse, both government hospitals and large private-sector hospital groups are increasingly competing to treat the same patient group as small and mid-size players. However, hospitals that participate in the social security system will be less affected by this and will enjoy a level of guaranteed revenue.

- Private-sector clinics: Earnings should remain satisfactory. But, it will be difficult for clinics to expand their customer base because: (i) the large universal healthcare coverage means the public will increasingly prefer to access healthcare through hospitals; (ii) many hospitals have changed their business model; to expand their reach, they are increasingly focusing on providing services outside hospital settings. For example, they would establish community clinics, stand-alone specialist clinics, and smaller clinics upcountry, in regional centers and in border zones. This has increased competition for independent players; and (iii) low-income groups have access to alternatives, such as buying modern or traditional medicines themselves or seeking alternative or complimentary treatment.

[1] Data released on April 4, 2017 by the Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Office of the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Public Health.

[2] The criteria for the classification is based on a geographic information system (GIS).

- Primary care providers include public health centers, municipal centers, community health centers, community hospitals, general hospitals, and other units. These may be in either the private or public sector.

- Secondary care is split between: (i) basic secondary care, which comprises community hospitals, general hospitals, and state and private medical units that have in-patient facilities to treat general conditions; (ii) mid-level secondary care, which comprises medical institutes that offer common specialist treatments; and (iii) upper-level secondary care, which comprises medical institutes that offer less common specialist treatments.

- Tertiary care is provided by some general hospitals, teaching hospitals, specialist hospitals or other public or private units, which offer treatments in sub-specialties or interventions that use advanced equipment, such as those for the treatment of heart disease.

[3] Data from the health and welfare survey conducted in 2017 by the National Statistical Office, National Health Security Office.

[4] Bureau of Sanatorium and Art of Healing, Department of Health Service Support, Ministry of public health

[5] From a 2017 survey of private hospitals (based on 2016 operating result); the survey is carried out every five years by the National Statistical Office, the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society.

[6] Data on foreign patients comes from a paper outlining the strategy for developing Thailand as an international medical hub between 2017 and 2026 issued by the Department of Health Service Support.

[7] www.hfocus.org

[8] ‘Good health at low cost, 25 years on: what makes a successful health system?’ World Health Organization.

[9] The Universal Coverage Scheme (also called the Gold Card or the 30 Baht Healthcare Scheme) began operating in 2002 under the management of the National Health Security Office (NHSO) and is the largest of the healthcare funds. The fund guarantees access to treatment for all Thai citizens without restriction, and covers around 80% of the population. The majority of those who use the Gold Card are low-income earners, those who work in informal employment, the elderly, and those who do not have access to other medical funds, and these combined represent some 75% of the total population. The government is responsible for managing healthcare through both state hospitals and private medical providers that are partners in the scheme.

[10] The Social Security Scheme (SSS) is a form of social welfare that was first rolled out in 1990 under the management of the Social Security Office (under Ministry of Labour). The SSS is the second most important public healthcare funds and provides care for the ‘self-insured’, who account for around 10% of the population. Financing comes from three sources: premiums paid by participants in the scheme, employers’ contributions, and government funding. The fund may pay for treatment in both public and private facilities. The Social Security Office pays a lump sum annually to hospitals to cover treatment for registered members, calculated based on the number of ‘self-insured’ patients which the hospital has treated over the course of the year.

[11] The Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) has been in operation since 1963 and uses tax receipts to pay for treatment for civil servants and their families in either state or private hospitals, without them having to make any contribution. Approximately 10% of the population is covered by this scheme.

[12] Classified as spending on healthcare that is greater than 10% of all household spending. Source: Household socio-economic survey, National Statistical Office.

[13] These countries are: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States

[14] BLT Bangkok, The market for Chinese and Middle Eastern tourists: a golden opportunity for Thai tourism, 31 May – 6 June 2018

[15] For hospitals listed on the stock exchange that generate a high proportion of their revenue from the treatment of foreign patients.

[16] Source: NESDC

[17] Visitors will need to isolate for 14 days in ‘alternative quarantine’, where their condition will be continuously monitored. Following the completion of this period of isolation, those arriving on the medical and wellness program will be able to travel on to their chosen destination

[18] BOT

[19] BCG’s Center for Customer Insight

[20] Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are those which cannot be transmitted and the category includes some chronic conditions which may take a considerable period of time to cure and to recover from. Bangkok Hospital reports that 73% of deaths in Thailand occur due to NCDs, which is higher than the world average of 63%. This situation is likely to lead to significantly greater expenditure on healthcare.

[21] From the Thai Health Promotion Foundation’s press release ‘World Diabetes Day Thailand 2019 Together Fight Diabetes’.

[22] The National Statistical Office of Thailand and the Department of Disease Control of Thailand.

[23] Investments related to the activities of the Ministry of Public Health that qualify for BOI or EEC investment support include: (i) The production of medicinal food and food supplements; (ii) the production of robotics and automated systems, or parts of these; (iii) the manufacture of electronic control and measurement equipment that has medical applications; (iv) the provision of digital services; (v) activities related to scientific research; (vi) calibration and measurement services; and (vii) three types of specialist medical center (those for the treatment of heart and kidney conditions and of cancers). The BOI targets its assistance at new activities and businesses that will support the development of medical hubs in Bangkok and major tourist areas, whereas the EEC encourages investment that will lead to the establishment of ‘future medicine’ healthcare centers or of laboratories, clinical research facilities or ‘cosmetic valley’-related ventures. In addition, the EEC also functions as a regulatory sandbox where testing and research on new innovations can be carried out under the oversight of state authorities.

.webp.aspx)