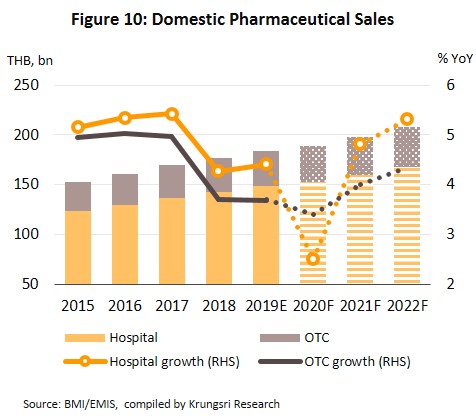

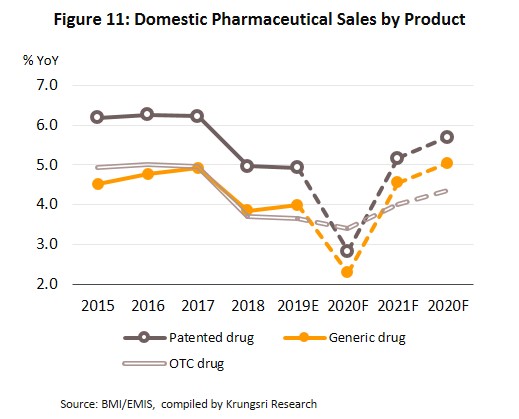

In 2020, the value of pharmaceuticals distributed to the domestic market is projected to grow by only 2.0-3.0% (vs 4.2% in 2019) because of fewer domestic and international patients seeking treatment in Thai hospitals. This is largely driven by fears of contracting Covid-19 coupled with social distancing measures and lockdown restrictions in 1H20. This would reduce the value of pharmaceuticals distributed through hospitals (the major distribution channel in Thailand). However,

in 2021 and 2022, domestic demand for pharmaceuticals should recover and growth should average 4.5-5.0% p.a. Sales volume would rise driven by the following: (i) the rising number of chronic non-communicable diseases which are typically treated with expensive imported medicines; (ii) an aging Thai population; and (iii) the provision of universal health coverage.

At the same time, competition will also rise. (i) The domestic market will see greater pressure from cheap imports from India and China. (ii) There will be more new players in the market, including overseas investors (e.g. from Japan) who are increasingly operating production facilities in Thailand to manufacture generic drugs for export back to their home country, or to penetrate markets in the CLMV region where there is rising demand for Thai medicines. (iii) Domestic players from outside the industry are also ramping up investment in the sector. Simultaneously, the additional outlay involved in meeting GMP-PIC/S standards and more expensive imported inputs are expected to push up production costs in the industry.

Overview

The pharmaceutical and medical supplies sector includes conventional medicines and chemicals which are used in the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses. Conventional pharmaceuticals can be split into two groups:

- Original drugs or patented drugs are medicines that have gone through the lengthy research & development (R&D) process, and therefore would involve significant production cost. Manufacturers of original drugs are normally given a 20-year patent[1] protection and when the patent expires, other manufacturers are then allowed to produce those medicines.

- Generic drugs are copies of original drugs that are typically manufactured under a trademark or brand name but do not have patent protection. Generic drugs normally contain active ingredients that are identical to those found in original drugs for which patent protection has expired. Since the production of generic drugs does not usually require expensive inputs or costly R&D and clinical trials, production cost is typically lower than for original drugs.

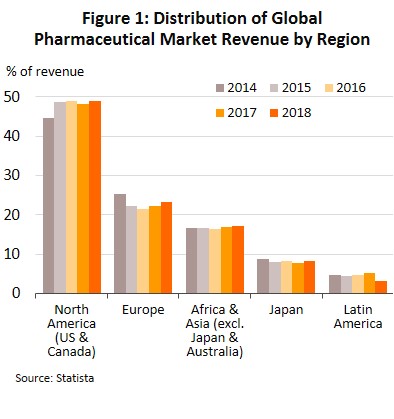

The continuous and costly R&D required in the development of new medicines and materials have prompted many global producers of pharmaceutical and medical supplies, especially original drugs, to cluster in developed economies such as the United States, Europe, and Japan, because of easy access to skilled professionals, expertise and manufacturing technology. These countries then export to meet global demand (Figure 1), while developing countries are left to play the role of importers of expensive patented medicines.

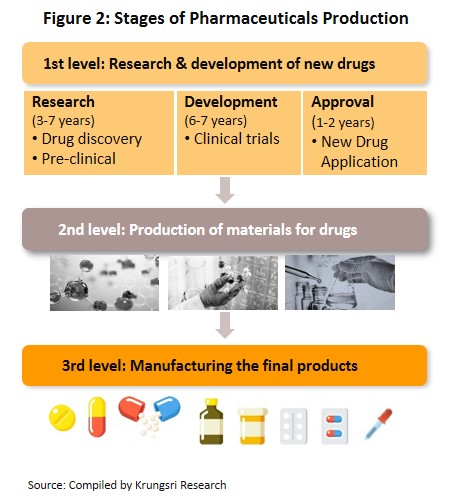

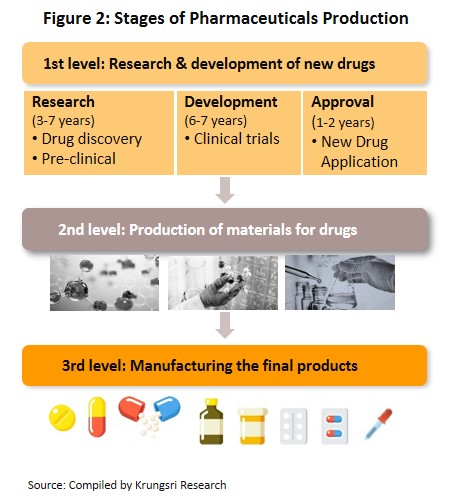

The conventional medicines production chain is split into three stages (Figure 2).

- Primary: This involves R&D of new medicines.

- Intermediate: This involves the production of ingredients to be combined to make the final product. These ingredients are either active or inert, and are normally added to speed up chemical reaction. The ingredients manufactured in this stage are normally already available in the market but require special processing techniques to produce the desired chemical reaction or to change the molecular structure of existing chemicals, which normally require advanced technology and a large investment.

- Finished product (or chemical formula): The active ingredients are imported and mixed to produce a range of finished products including tablets, liquid medicines, capsules, creams, powders and injectable medicines.

The majority of Thai conventional medicine manufacturers are final-stage producers of finished generic drugs. The active ingredients are usually imported for domestic mixing and production into several forms for use in treatments. Thailand imports about 90% of all inputs used in the production of finished products. The highest value medicines are analgesics and medicines for treating fever. Data from the Food & Drug Administration show that as at February 2020, there were 144 domestic pharmaceuticals producers accredited with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standard. But, not more than 5% have the ability to manufacture active ingredients (such as aluminum hydroxide, aspirin, sodium bicarbonate, or deferiprone) and they are largely for use in-house as inputs for finished products. In R&D, Thailand has been involved mainly in research into vaccines, for example against HIV, bird flu and influenza.

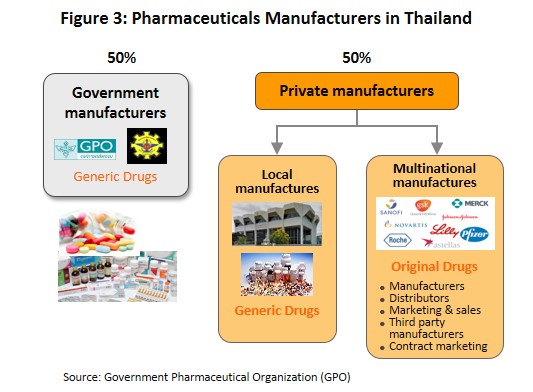

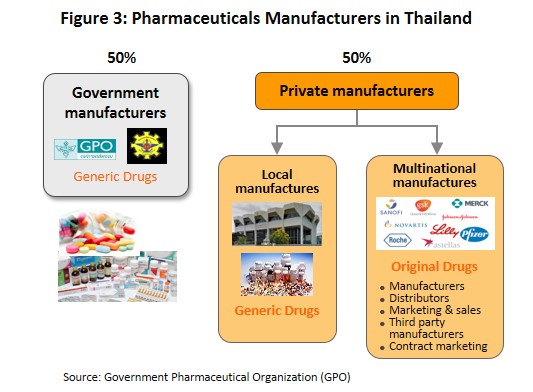

The main state manufacturer of pharmaceuticals is the Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO). Previously, government hospitals had to purchase their supplies principally from state suppliers. However, the Government Procurement and Supplies Management Act B.E.2560 which came into effect in August 2017 is intended to increase competition. This effectively allowed state hospitals to purchase supplies from non-GPO suppliers. This created a level playing field for private enterprises and increased competition between the GPO and private sector players, including suppliers in India and China which export low-cost products. Players in the medicines sector can be split into two groups (Figure 3).

- Group 1 comprises state enterprises, such as the GPO and the Defense Pharmaceutical Factory, which emphasize the production of generic drugs as alternatives to imported drugs.

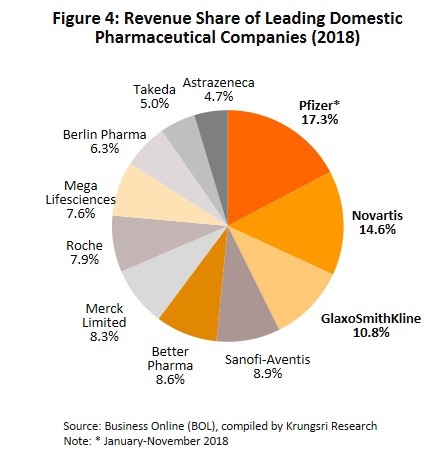

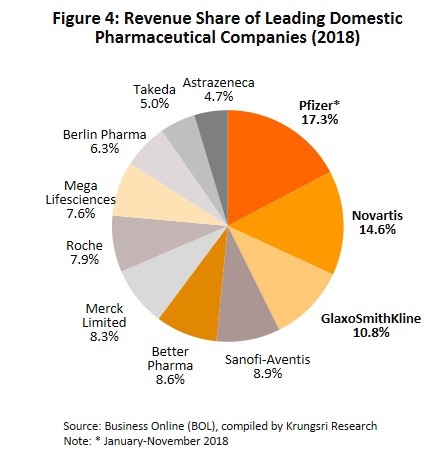

- Group 2 comprises private sector producers. This can be divided into two sub-groups: (i) local manufacturers with Thai shareholders, which typically produce general-purpose low-cost generic drugs. Examples include Siam Pharmaceuticals, Berlin Pharmaceutical Industry, Thai Nakorn Patana, Biopharm Chemicals and Siam Pharmacy. Contract manufacturers such as Biolab, Mega Lifesciences and Olic (Thailand) also belong in this group; and (ii) multinationals (or MNCs) with foreign shareholders, which focus on original drugs and operate as agents to import pricier drugs for distribution in Thailand, though some have also established production facilities in the country. Operators in this group include Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis (Figure 4).

Currently, two laws govern the manufacture of pharmaceuticals in Thailand. They are: (i) Patent Act B.E. 2522 (1979) and amendments, which grant patent-rights to discoverers and inventors (i.e. protects intellectual property rights), supervised by the Department of Intellectual Property; and (ii) Drug Act B.E. 2510 (1967) and amendments[2], which regulate the manufacture, import, sale and marketing of drugs in Thailand. In terms of regulatory bodies, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for overseeing compliance in the sector. Its tasks include licensing operators and registering drugs for domestic distribution. Potentially partnering in CPTPP would have a long-term effect on Thailand’s registration of drugs and licensing of patent.[3] This could extend drug patent rights for manufacturers of original drugs beyond 20 years, and domestic drug prices will remain extremely expensive.

Private sector pharmaceuticals manufacturers typically face pressure from factors that hinder profitability. (i) The Ministry of Public Health and the Comptroller General’s Department have set a list of reference prices for approved drugs, which is used as a tool to control expenses and set appropriate costs for the purchase of pharmaceuticals by public healthcare providers; (ii) Imports of cheap drugs from India and China, which have lower production costs than Thailand; and (iii) The domestic private sector still has disadvantages relative to the GPO in terms of manufacturing and distribution. The private sector is also experiencing rising manufacturing costs following the implementation of the GMP-PIC/S standards[4] (effective 1 August 2016).

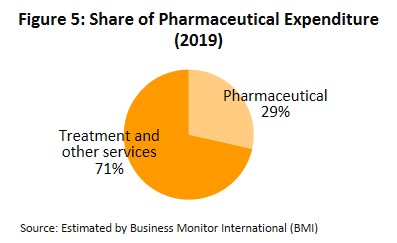

In distribution, approximately 90% of Thailand’s pharmaceuticals output is consumed by the domestic market. This was largely triggered by the expansion of national universal healthcare coverage (UHC)[5], specifically the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) which now covers 99.78% of Thailand’s population. That has increased access to healthcare for most of the population nationwide, which naturally caused the consumption of medicines to jump. Drugs and medicines now account for a quarter of all domestic medical expenses (Figure 5).

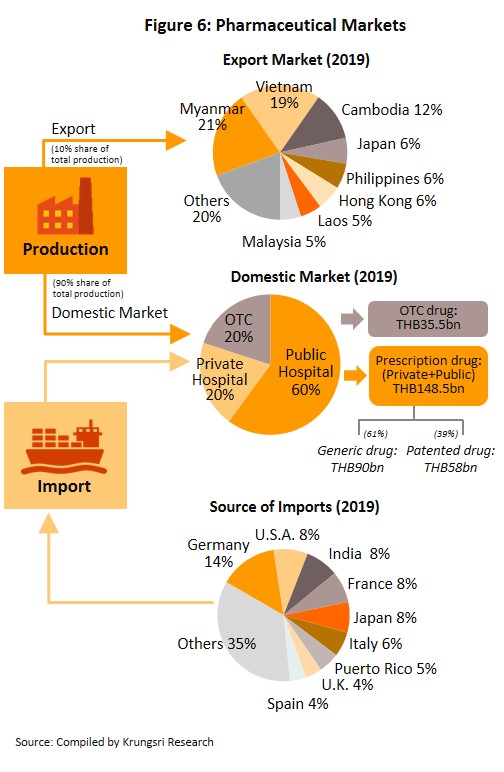

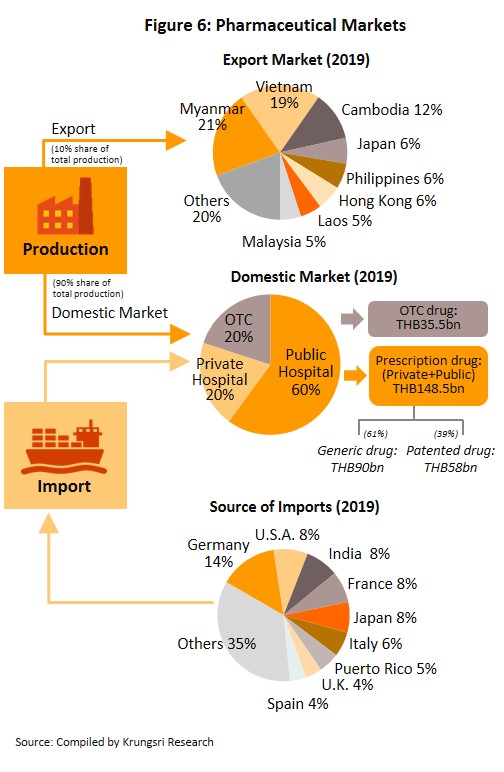

Medicines and pharmaceuticals are distributed through two main channels (Figure 6).

- Hospitals: Thailand’s public healthcare system is extensive, covering both civil servants and the majority of scheme claimants. By value, 80% of the total domestic market for medicines is distributed through hospitals, comprising 60% government hospitals and 20% private-sector operations. Medicines distributed through hospitals are generally prescription drugs, which can be further sub-divided into (i) generic drugs, which account for 61% of the value of medicines distributed via hospitals, and (ii) patented drugs, which make up the remaining 39%. But although this latter group has a smaller share, consumption of patented drugs is growing faster than the consumption of generic drugs, because they are mostly used to treat common chronic non-communicable conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease.

- Over-the-Counter (OTC) medicines: Although the government health insurance scheme encourages individuals to increasingly seek medical care in hospitals instead of buying OTC medicines from pharmacies, the latter remain an important distribution channel for those with common minor ailments which can be treated with a quick trip to a pharmacy. Hence, the value of the OTC drugs market has been stable at 19-20% share of the total market for medicines. Nationwide, there are 20,516 registered pharmacies, 25% of which are in Bangkok and 75% in the provinces (source: FDA, August 2019). Pharmacies can be split into the two major groups: (i) stand-alone stores, mostly SMEs, which account for over 80% of pharmacy outlets in the country, and (ii) chain stores, which may either be run, centrally-funded, or organized for expansion through franchising, such as Fascino and Save Drug (a member of BDMS). Beyond this, modern trade outlets (including discount stores, supermarkets, convenience stores and specialist health stores) are turning over a part of their floor space to medicines and pharmaceuticals, and so are able to reach a wide range of customers.

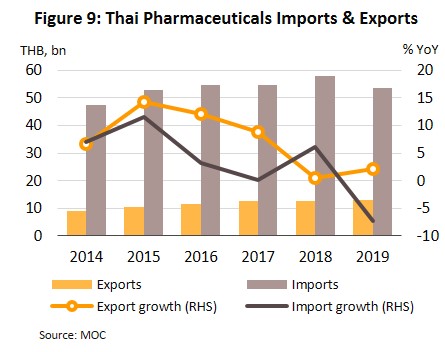

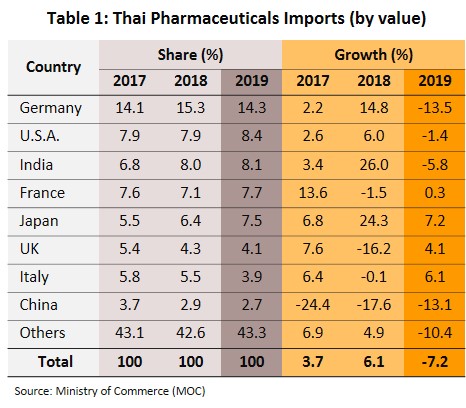

Thailand exports only about 10% of its pharmaceuticals output. Between 2012 and 2018, exports of Thai pharmaceuticals grew by about 8% per year, but since these are low-value generics, they accounted for only 0.20% of the value of pharmaceuticals exports. A large share goes to neighboring countries, with Vietnam, Myanmar, Lao PDR, and Cambodia taking 57% by value. Imports, on the other hand, are normally high-value products that the domestic sector is unable to produce. These include anti-anemia treatments, antibiotics, and cholesterol-lowering medications. The main exporters to Thailand are Germany, the United States, and France and because the exchange has been one-sided, there has long been an imbalance in the trade in pharmaceuticals. However, imports from India has been rising since 2014 to account for 7.5% of total pharmaceuticals imports in 2014-2018, from 5.9% in 2013. Most of these imports are cheap generics because India has benefited from open patents and a system of ‘compulsory licensing’[6] that allows local manufacturers to override patent rights in some cases and enables them to manufacture generic versions of original drugs at much lower costs.

Situation

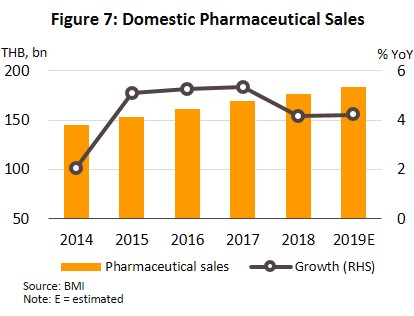

During 2013-2018, the Thai pharmaceuticals market was the second largest in Southeast Asia, after Indonesia.

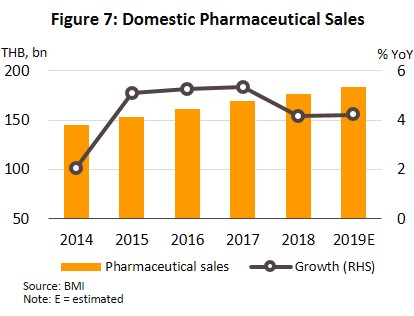

During the period, the total value of pharmaceuticals distributed to the domestic market grew by an annual average rate of 4.5% (Figure 7). However, the implementation of universal health insurance coverage in Thailand led to an increasing number of residents seeking treatment in hospitals, which pushed up the growth of medicines distributed through hospitals relative to sales through pharmacies (or OTC sales).

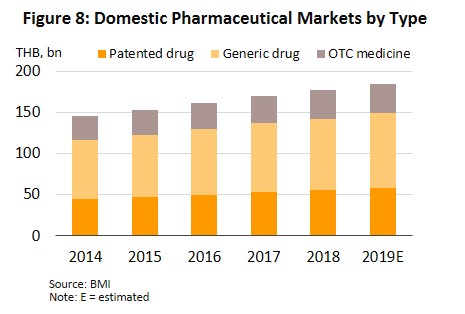

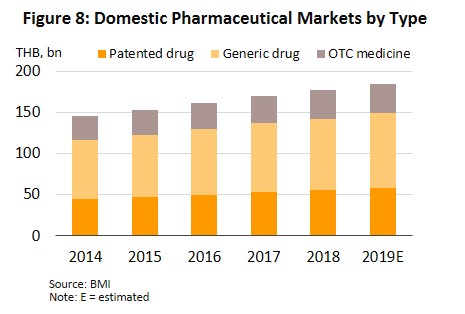

In 2019, the market for pharmaceuticals expanded by another 4.2% to THB184.1bn (Figure 7), split between: (i) medicines distributed through hospitals or with a doctor’s prescription, comprising THB90.2bn worth of generic drugs (+4.0%) and THB58.3bn worth of original or patented drugs (+4.9%); and (ii) pharmacy or OTC sales, which had a value of THB35.5bn (+3.7%) (Figure 8). The rising demand for medicines is driven by an increase in seasonal illnesses (e.g. influenza, dengue fever), persistent problems with air pollution, and rising number of patients with non-communicable chronic conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes) driven by more elderly people. In response to this and to control costs, both the government and private-sector hospitals are seeking to use more domestically-produced generic drugs.

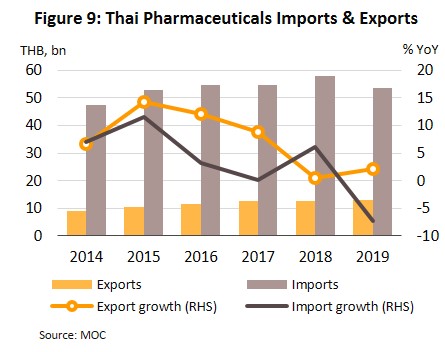

Exports also rose by 2.1% in the year, generating THB13bn receipts (Figure 9), thanks to expanding markets in Singapore, Vietnam, Japan, Lao PDR and Cambodia. Among these, the Vietnam market was particularly strong, with export value growing by 19.2% following a 30.7% drop in 2018 after the government there relaxed official restrictions on imports, including import quotas and the accompanying red tape. Thai manufacturers also benefited from admission into the ASEAN Listed Inspection Service[7], which made exports to the rest of the ASEAN zone easier and more convenient.

Total output of Thailand’s pharmaceuticals sector[8] was almost unchanged in 2019, falling by 0.04%. But the output of different product groups changed significantly. Liquid medicines, which account for 37.6% of pharmaceuticals by quantity, are the most important products. In 2019, their output fell by 12.5% following the government’s move in 2018 to restrict sales of goods that can cause intoxication or be used to manufacture illegal drugs[9], including cough medicines that are made from diphenhydramine, promethazine or dextromethorphan. However, output of other product groups jumped: tablets (32.0% of total output) rose by 14.0%, powders (7.3% of total) rose by 8.4%, capsules (6.8% of total) rose by 12.5%, and injectables (6.6% of total) increased by 6.2%. Given that larger operators expanded production capacity, capacity utilization remained close to 2018 level, at 73.7%.

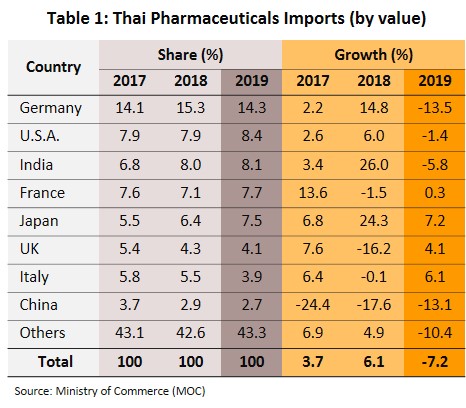

Imports fell by 7.2% to THB53bn in the year (Figure 9). They were mostly original or patented medicines, especially drugs for the treatment of hypertension and diabetes. Most of these came from Germany, the United States and India (a combined value accounts for 31% of medicines imported into Thailand). However, the value of imports from these countries shrank by 8.5% because of a stronger baht (which reduced import prices). A slide in the cost of active ingredients also reduced cost of imports from China (2.7% of total), which fell from a year earlier (Table 1).

Investment in pharmaceuticals dropped in 2019. There were only 9 applications in the entire year with a combined value of THB720.2m, down 93.5% from 2018 total. However, this was due to the rush to submit applications in 2017-2018, when the Thai government encouraged investors to upgrade production facilities to meet GMP PIC/S standards by offering 8-year tax exemption (starting 2019, but the exemption was subsequently reduced to 5 years). In 2018, Thailand approved 24 pharmaceuticals projects with a combined value of THB11.06bn.

In the first quarter of 2020, domestic sales of medicines increased by 7.5% YoY to THB5.7bn. The Covid-19 outbreak had bolstered demand for medicines to treat fever, painkillers, anti-inflammatory treatments, and vaccines. By individual product group, sales value of tablets rose by 14.6% YoY, capsules by 13.5% YoY, injectables by 9.8% YoY, and liquid medicines by 1.9% YoY.

In line with this, the value of imports inched up 0.7% YoY to THB13bn in the same period. The largest supplier of medicines and precursors was China (3.2% of imports vs 2.7% in all of 2019) and India (8.5%) which import values grew by 30.8% and 0.2% YoY, respectively. Exports moved in the opposite direction, falling 4.4% YoY (by volume) and 11.3% YoY (by value) because Thailand, like most countries, held back exports of medicines during the Covid-19 outbreak, and prioritized domestic demand.

In the coming period, Thai manufacturers would see rising input prices as a result of the temporary halt in the production of precursors and other ingredients in China earlier this year. India’s government has also banned the export of some pharmaceutical inputs and 26 listed medicines (including paracetamol), to keep these for use within the country. In addition, many world-leading manufacturers of patented medicines in the US, Germany and Britain have temporarily halted research and clinical trials of many products so that they can concentrate resources to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. However, this might cause a shortage or price hikes for raw materials and precursor chemicals, which would lift production costs for Thai operators, most of which depend on imported input and patented drugs.

Outlook

The pharmaceuticals market is forecast to grow by only 2.0-3.0% in 2020 as fears of being infected by Covid-19 and the enforcement of social distancing measures in the first half of the year are keeping both foreign and domestic patients away from hospitals. And because hospitals are the largest distribution channel for medicines in Thailand, consumption of medicines will drop.

However, in 2021 and 2022, growth would accelerate to 4.5-5.0% per year (Fig. 10 and 11) supported by several factors:

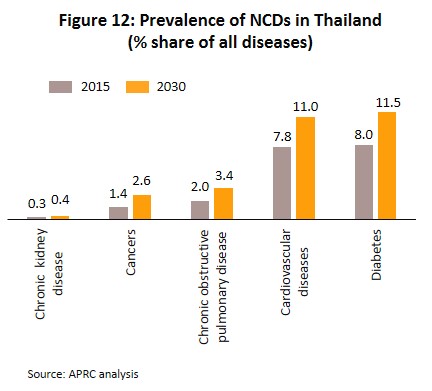

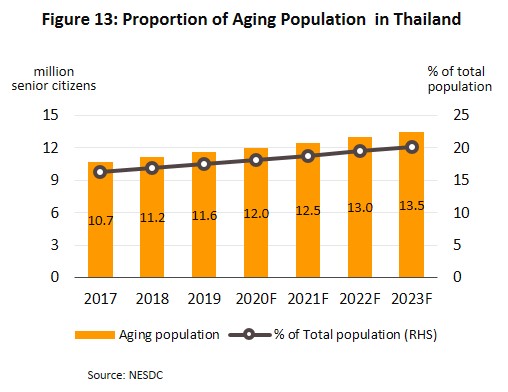

- Rising incidence of patients with communicable and non-communicable diseases[10]. The most common communicable diseases are diarrhea, pneumonia and dengue fever, while the most frequently encountered serious non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease and stroke (Figure 12). At the same time, Thailand has an aging population and among the elderly, large numbers are affected by chronic NCDs, especially hypertension which affects almost half of the elderly in Thailand[11], and less commonly, diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cancer. The Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council estimates the number of Thais over-60 will increase from 11.2 million in 2018 to 13.5 million in 2023 (Figure 13) and that expenditure on healthcare for the elderly will rise to THB228bn in 2022 (2.8% of GDP) from THB63bn in 2010 (2.1% of GDP) (source: Thailand Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017-2021)). Given this, domestic consumption of drugs and imports of patented medicines from overseas manufacturers are likely to increase steadily.

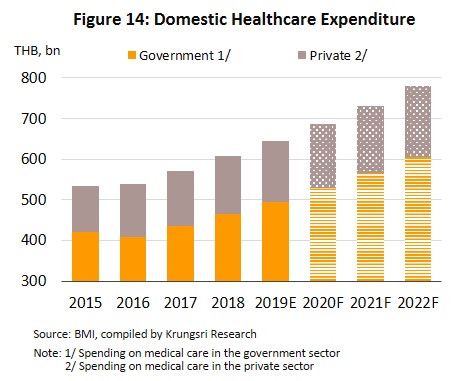

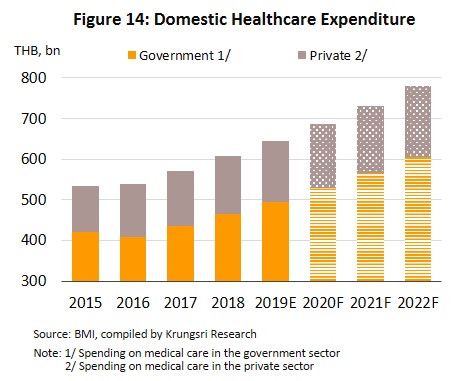

- The extension of the public universal health coverage scheme means that almost all Thais now have access to better quality healthcare. In fact, over 99% of the population is now covered by some kind of health insurance. Over 75% of the population has a right to free healthcare under the Gold Card scheme, followed by 17% who can access health services under the social security scheme, and 7% have private insurance. Because of this, during 2020-2022, expenditure on medical treatment (for both medicines and care) is expected to grow by 6.6% per year (vs 6.3% in 2019), comprising 6.9% growth in public-sector spending and 5.5% growth in private sector spending, which would be an increase from 6.7% and 5.1% growth in 2019, respectively (Figure 14).

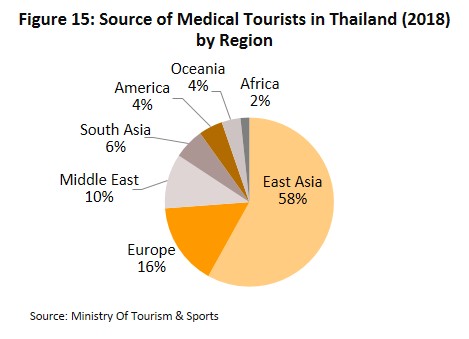

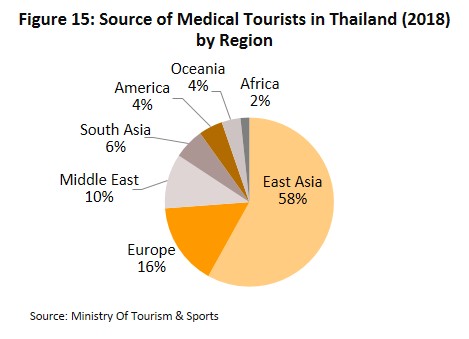

- Number of overseas patients seeking treatment in Thai hospitals will grow again in 2021 and 2022, following a decline in 2020. Private healthcare operators in Thailand offer superior quality healthcare and services as well as inexpensive medical fees. Many also operate specialist centers, especially for the treatment of NCDs including heart disease, rare bone conditions, and cancer, as well as senior care centers which are often cheaper than alternatives in Singapore and Malaysia. This has attracted a rising number of non-Thais to the country to seek treatment, with growth driven by both general and medical tourists which account for 80% of all foreign patients. Most of the foreign patients that seek Thai medical care come from East Asia, Europe and the Middle East. Krungsri Research estimates the number of foreign patients increased by 4.5% in 2019, but would shrink by over 60% in 2020 with the sharp drop in foreign tourist arrivals because of Covid-19.

- Health concerns have put people on high alert, which could encourage individuals to seek medical care in hospitals and/or buy medicines from pharmacies although they have only mild symptoms.

In 2021 and 2022, investment in the healthcare industry will increase. This would be driven by: (i) greater demand; (ii) the government’s pro-investment policies, which currently include 5-year tax-exempt period for projects approved under the BOI investment promotion scheme; and (iii) the fact that the pharmaceuticals industry is one of the government-designated new S-curve industries, for which investment support is available for projects in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). It is also a high-tech industry that the government is supporting through financial assistance for research and additional tax benefits for investors. These should thus help to stimulate greater levels of investment when the depressed conditions in 2020 dissipate.

Opportunities for players to improve domestic production processes and reduce reliance on imports. The government is encouraging domestic manufacturers to produce high-value original drugs and medicines for which patents have expired (such as medicines to treat hypertension and diabetes, and antibiotics) as well as to develop biologics such as anti-cancer treatments for which demand is expected to rise. These products are so appealing since companies that do not normally operate within the pharmaceuticals industry are planning to invest in facilities to produce active pharmaceutical ingredients. This includes PTT and the Government Pharmaceutical Organization, which are jointly investing in new facilities to produce three types of cancer treatment: (i) pill-based and injectable chemotherapy treatments, which are the conventional treatments for cancer; (ii) pills and injectable biosimilar versions of monoclonal antibodies; and (iii) targeted treatments that will attack cancer cells directly. SCG Chemicals is also putting money into biologics, while Medicpharma (part of Bangkok Hospital group) plans to begin manufacturing pharmaceutical precursors. Beyond this, because Thailand’s pharmaceuticals sector has dealt with disease outbreaks for many years, from SARS and MERS to Ebola and now Covid-19, the sector has several advantages: (i) expertise of Thai doctors and medical engineers in researching vaccines; (ii) ready access to a wide range of herbs and natural products[12] to produce extracts for use in biomedical/biopharma applications; and (iii) the advanced state of the country’s bioinformatics industry, which will support the further development of medical and pharmaceutical research. In the future, these factors will help the country develop high-quality medicines and vaccines at lower costs. This would, in turn, reduce dependence on imported high-cost inputs and patented drugs.

However, there will still be challenges. Competition will intensify in the industry because of (i) greater imports of low-cost pharmaceuticals from India and China; (ii) the entry of new foreign investors (e.g. from Japan) which are setting up production facilities in Thailand to manufacture generics for export back to their home country or to penetrate the CLMV market; and (iii) increasing interest in the sector from Thai corporations that operate in other industries.

Meanwhile, manufacturing costs are likely to rise due to a combination of additional overheads to meet GMP-PIC/S standards and escalating cost of imported inputs and patented medicines.

Krungsri Research’s view

Following flat growth in 2020, manufacturers’ and distributors’ earning will improve in 2021 and 2022. However, earnings growth should be moderate given more intense competition.

Manufacturers of pharmaceuticals: Hospital visits will drop in Thailand this year due to fears of contracting Covid-19 and the imposition of social distancing measures. Consequently, the volume of medicines distributed through hospitals would also drop. This would feed back into smaller orders for manufacturers of pharmaceuticals in 2020. However,

the pharmaceuticals market is expected to recover in the following two years, and along with that, earnings will improve. Sales of patented medicines will see persistent demand from patients with chronic NCDs (such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, stroke and cancer). Meanwhile, sales of generic drugs would be driven by rising demand triggered by the extension of the universal healthcare scheme to the entire Thai population, and greater incidences of communicable diseases, including the various types of influenza, respiratory illnesses and allergies. On the downside, competition will intensify and business costs will rise with the extra expenses required to upgrade facilities to meet GMP-PIC/S standards, higher costs for imported inputs, and the government’s move to control the costs of medicines in private hospitals. These will collectively cap earnings growth and profitability.

Distributors of pharmaceuticals (retailers and wholesalers): Distributors’ revenues will rise, albeit only gradually, supported by rising domestic demand for medicines. But as with manufacturers, competition will intensify, especially for stand-alone retailers and general pharmacies. They will face rising threat from large operators of chain stores, some of which have aggressive expansion plans. For example, Fascino (a pharmacy chain) plans to extend its current network of 100+ branches by opening 200 franchise outlets over the next 3 years, Save Drug (part of Bangkok Hospital group) hopes to expand its network of 100 branches nationwide, and large modern retail operations, including discount stores and supermarkets, also expect to divert more floor-space to medicines and supplements. Over the next 3 years, Thailand is expected to see at least 50 new pharmacy stores annually. These developments will increase the dominance of chain stores, but most convenience stores also carry a range of pharmaceutical products and they have outlets across the country. Thailand is projected to see 600-700 new convenience stores per year, which will increase competitive pressure for stand-alone operators. As such, pharmacy operators will register limited earnings growth.

Wholesalers of pharmaceuticals are also increasingly expanding into the retail market, and because they enjoy cost advantages by being able to place larger orders, their earnings should continue to grow.

[1] Under the WTO’s Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

[2] The Drug Act has been enforced since 1967 and was amended. The Drug Act (No. 6) B.E. 2562 the has been completed and is enforced.

[3] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is also responsible for checking whether generic drugs have a patent protection, in addition to checking for the quality and safety of the drugs that are requested for registration.

[4] The Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) is a cooperative framework which was set up by GMP inspectors from a number of countries (but especially European ones) that wished to establish universal standards for assessing GMP in pharmaceuticals production. Thailand officially became its 49th member on 1st August 2016.

[5] In November 2002, Thailand instituted a system of universal healthcare through the passing of the National Health Security Act. This means that all Thai citizens are able to access state-provided medical care through one of three funds: (i) the national health insurance fund, or ‘gold card’; (ii) the social security fund; and (iii) the civil service health fund.

[6] Compulsory licensing (CL) is employed to reduce the conditions of monopoly and to help other countries can apply CL to produce medicines for solving public health or treating hazardous communicable disease their countries.

[7] Thailand was formally admitted into the ASEAN Listed Inspection Service in March 2015 and this was then confirmed by the FDA. Entry allowed Thailand to join other members (Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia) in being able to export within the ASEAN region while being exempted from GMP or other examinations on entry into the export market and this helps to reduce duplication of work and cost burdens.

[8] Source: Office of Industrial Economics, produced liquid medicines, tablets, capsules, creams, powders and injectable medicines

[9] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed restrictions on the sale and distribution of these medicines. Pharmacists are also now required to maintain a register of sales of these items to prevent people from doing the repurchase and misuse of drugs.

[10] Source: Ministry of Public Health, Fiscal Year 2020 (October 2019 – March 2020)

[11] The Ministry of Public Health states that of 9 million elderly, over 4 million have hypertension and over 2 million have diabetes.

[12] The National Master Plan on Thai Herbal Development 2017-2021 added a list of Thai herbs to the National List of Essential Medicines, and allowed hospitals to use herbal treatments to reduce reliance on expensive imported drugs.

.webp.aspx)