EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

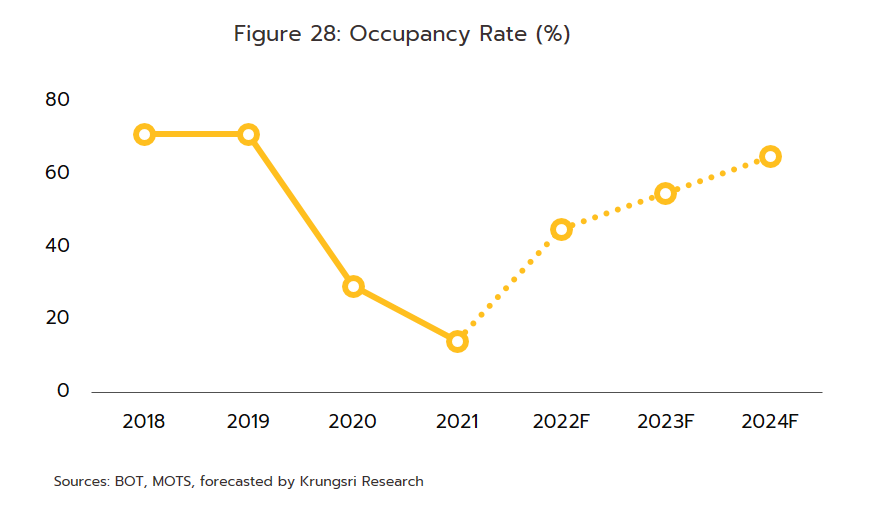

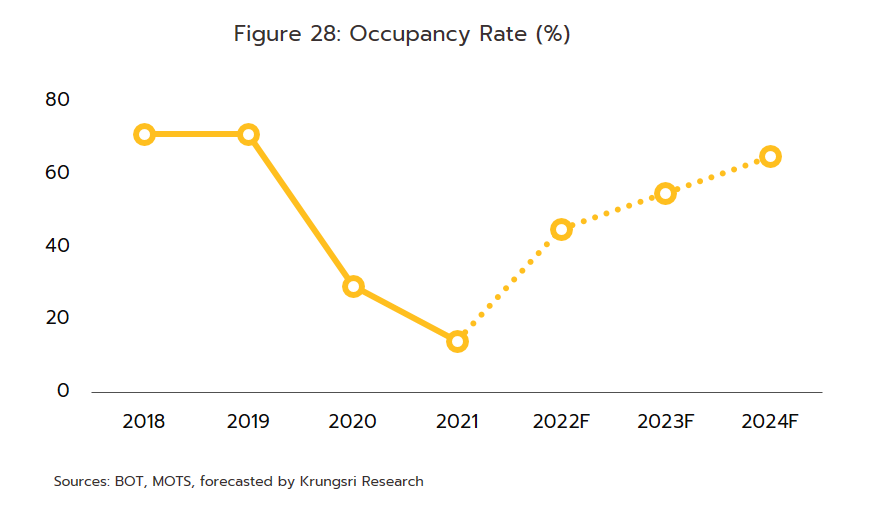

The hotel business will enjoy a steadily improving outlook over the next three years. However, recovery will remain only sluggish through 2022 given the limited number of tourist arrivals, and in particular the continuing depressed state of the Chinese market, where the government is still strictly implementing Zero-COVID policy. In addition, the global economy is facing significant headwinds as a result of the outbreak of Russia-Ukraine war, and this too is weighing on the industry. Nevertheless, the number of foreign arrivals should build at an accelerating rate through 2023 and 2024, and by 2025, the industry is expected to return to its pre-COVID level of 38-40 million arrivals annually. Alongside this, the domestic market will also continue to strengthen on government policies to stimulate internal tourism. On the supply side, large hotel operators are expected to continue with their expansion plans, though possibly at a slower rate than initially intended. As such, the national occupancy rate will remain somewhat underwhelming, hitting an average of just 45% in 2022 and then improving to around 55% in 2023 and 65% in 2024. Thus, the significant oversupply of accommodation seen in all parts of the country will combine with the slow recovery in arrivals to impose a tight limit on how much space operators will have to raise room rates.

Krungsri Research view

-

Hotels in the major tourist areas of Bangkok, Pattaya and Phuket: Because hotels in these cities are dependent primarily on foreign tourists, conditions will remain depressed in 2022, but the outlook will improve in 2023 and 2024 on greater demand from both Thai and international visitors. By the end of the period, occupancy rates should be back to around 65-70%, compared to 79% in 2019.

-

Hotels in regional centers and other popular tourist areas[1]: These hotels will see ongoing recovery. Because most of these establishments serve the domestic market, they will benefit from the government’s policies to stimulate the tourism sector, but occupancy rates are expected to climb to just 50-52% over the next three years, some way off the 66% recorded in 2019.

- Hotels in other provinces: For these hotels, recovery will remain a slow and protracted affair, and although government efforts to support the tourism sector will help, travelers in these provinces are in fact often on their way to provincial centers or tourism sites elsewhere. Given this, recovery in income and occupancy rates will tend to lag that of the two groups described above.

In all parts of the country, hoteliers will have to contend with a rise in competition that will be stoked by an oversupply of short-term accommodation from both hotels and other types of daily accommodation. This will be worsened by the only slow recovery in demand, and because of this, average occupancy rates will remain at just 45%, 55%, and 65% over 2022, 2023, and 2024 (down from 71.4% in 2019). This will then place a tight cap on how far operators are able to raise room rates.

OVERVIEW

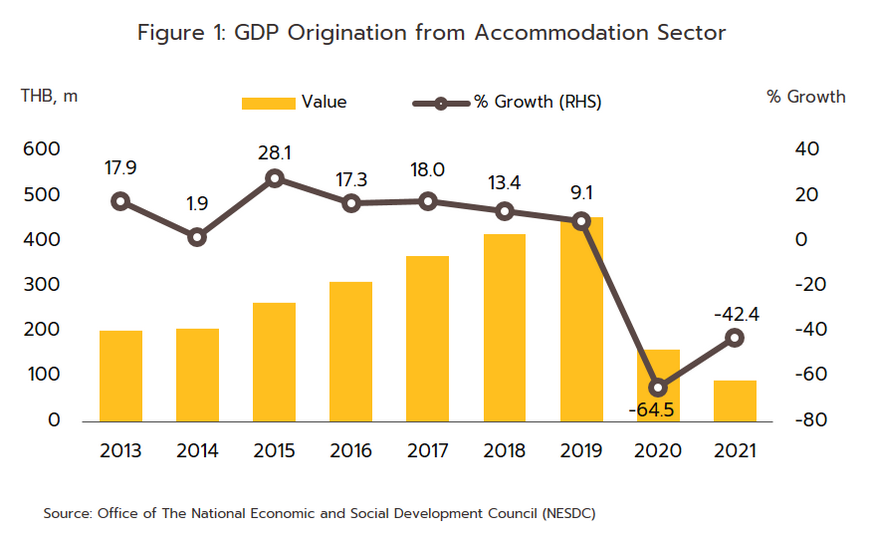

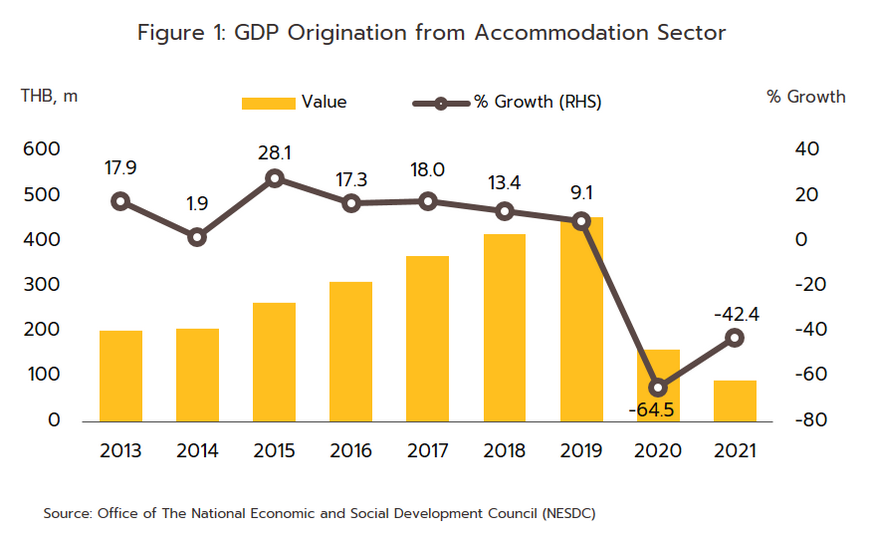

The hotel business (which here covers hotels, resorts, and guesthouses) is directly connected to the wider tourism sector, of which it forms an important part. In terms of its contribution to the Thai economy, over 2017-2019, short-term accommodation services accounted for 2.5% of Thai gross domestic product (GDP), but the outbreak of COVID-19 was a severe body blow to the industry and its contribution to GDP slumped to 1.0% of the total in 2020 and then to just 0.6% in 2021 (Figure 1). Naturally, hotel revenue comes mainly from room charges, and these account for approximately 65-70% of all hotel income. A further 25% comes from sales of food and drink, though the percentage varies with the type of hotel, and four- and five-star hotels will typically derive a greater portion of their income from food and drink than will smaller hotels. Income from other sources, such as providing washing and ironing services and collecting rents from shops operating on hotel premises, will usually contribute an additional 5-10% to total receipts.

The central role of the industry within the overall economy is explained by the fact that Thailand is regarded as one of the world’s foremost tourist destinations, and this is partly because of the world-class tourism attractions that are spread throughout the country, in particular the world-class destinations such as Bangkok, Pattaya, and Phuket. In addition, the country benefits from the competitive pricing of its accommodation and the low cost of living, which provides tourists with considerable value for money compared to other countries. Beyond this, the domestic travel industry’s potential is further enhanced by the country’s extensive and comprehensive transport networks, national infrastructure that is constantly being upgraded, and the steady rise in the number of low-cost carriers serving the local market, and these factors have helped to give Thailand an edge over its competitors. Indeed, the 2021 Travel and Tourism Development Index, compiled by the World Economic Forum and published in May 2022 (the most recent data available), places Thailand 36th out of the 117 countries surveyed and 3rd in Southeast Asia, sitting behind just Singapore and Indonesia (Figure 2). Within the Travel and Tourism rankings, relative to other countries in the Asia-Pacific region, Thailand scores particularly highly with regard to its price competitiveness and tourist service infrastructure, and comes after only Singapore and Indonesia on safety and security.

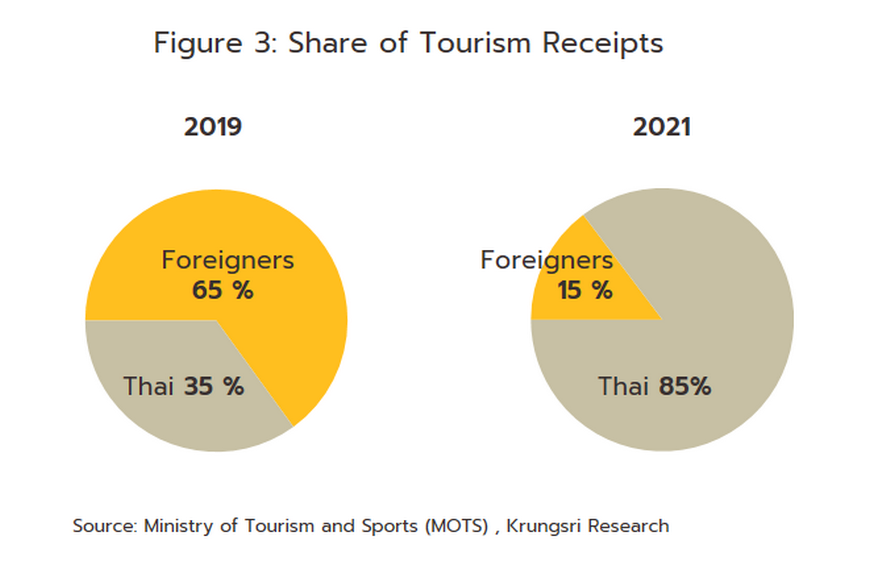

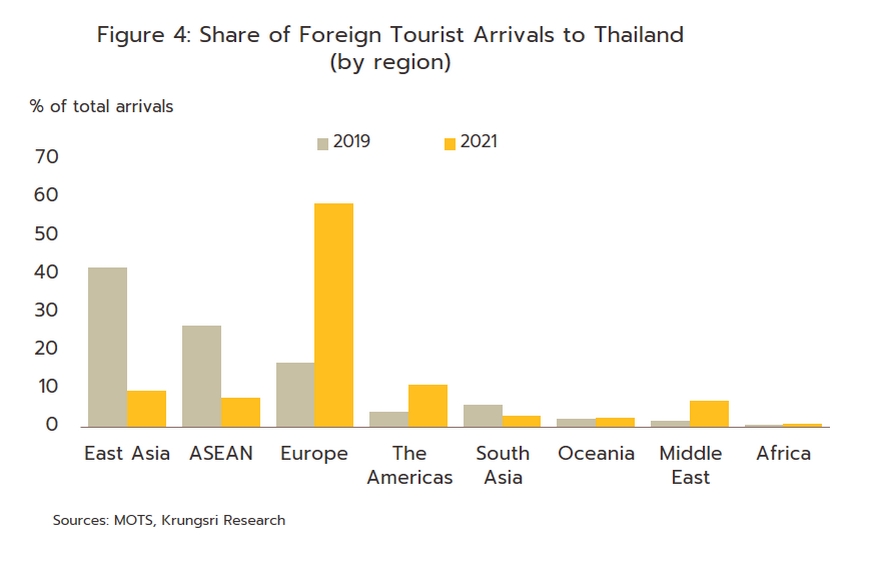

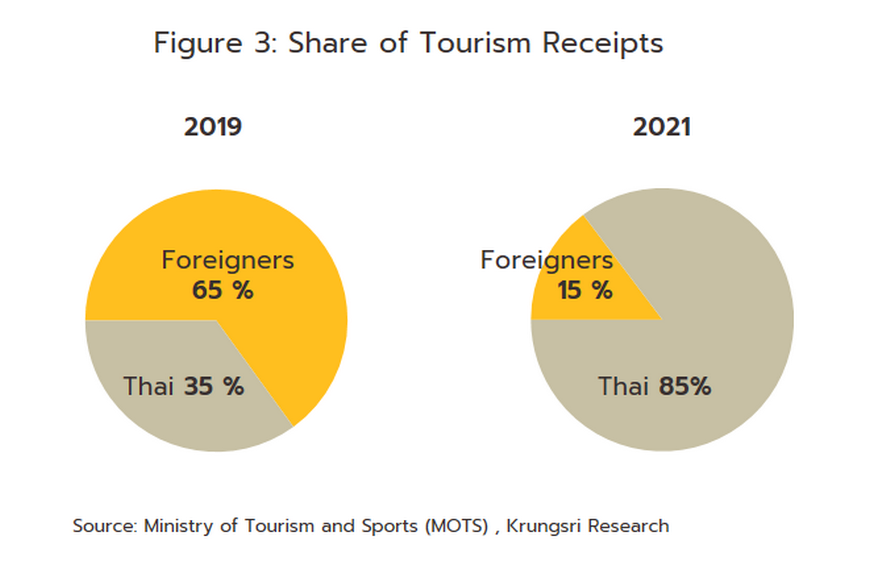

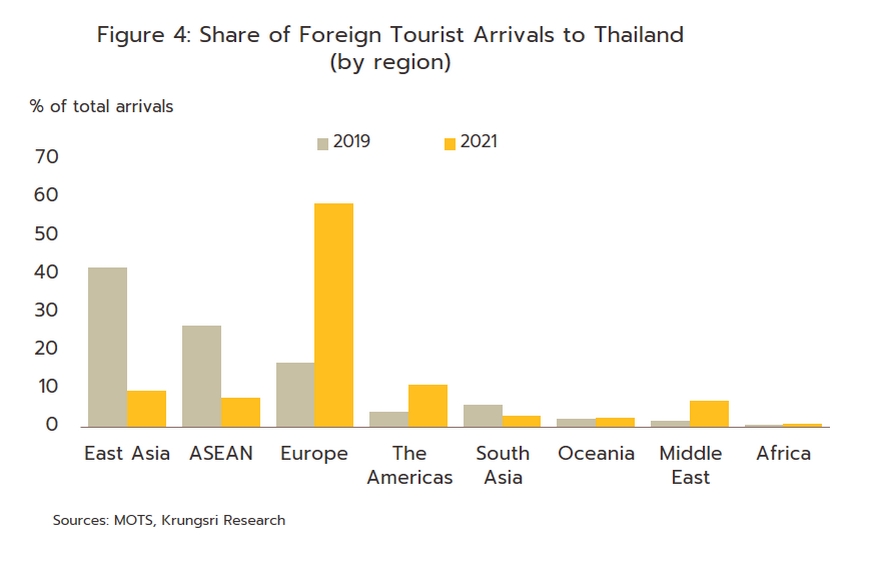

In normal circumstances, the tourism sector is a major driver of the Thai economy, though because their hotel stays are longer and they tend to spend more per head, the market is heavily dependent on foreign arrivals, which in 2019 accounted for 65% of total income to the sector (Figure 3). By originating area, the most important market is East Asia (i.e., China, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), which pre-Covid contributed 42% of all overseas arrivals and 41% of spending by foreign tourists. However, the extended COVID-19 pandemic meant that over 2020 and 2021, the number of tourists visiting Thailand crashed, so in 2020 income from foreign tourists slumped to 41% of all receipts from tourism and then to just 15% in 2021, or to THB 330 billion and THB 40 billion, respectively. As such, the industry pivoted to a much greater reliance on the domestic market, with the THB 220 billion in spending by Thai travelers providing 85% of income in 2021, up from 35% in 2019 (Figure 3). The shape of the overseas market has also changed. In 2021, Europe’s 59% market share established it as the largest segment, followed in importance by the Americas, with 11% of the total. This change is attributable to the favorable international view of Thailand’s management of COVID-19 and the resulting high level of confidence in the country’s tourism industry, coupled with the relaxation of controls on international travel in these regions. However, continuing restrictions on outbound tourism in China means that the East Asian market has dropped in importance, and with just 9% of tourists coming from the region, it has slipped to third place in the rankings (Figure 4).

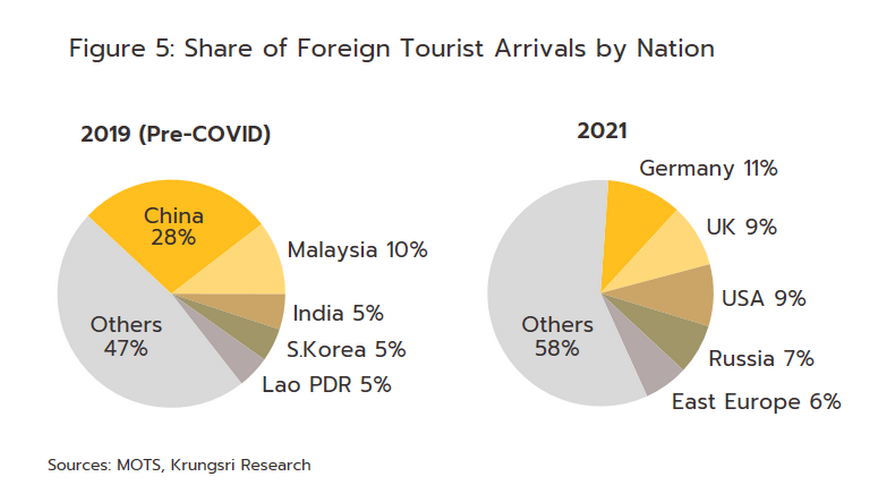

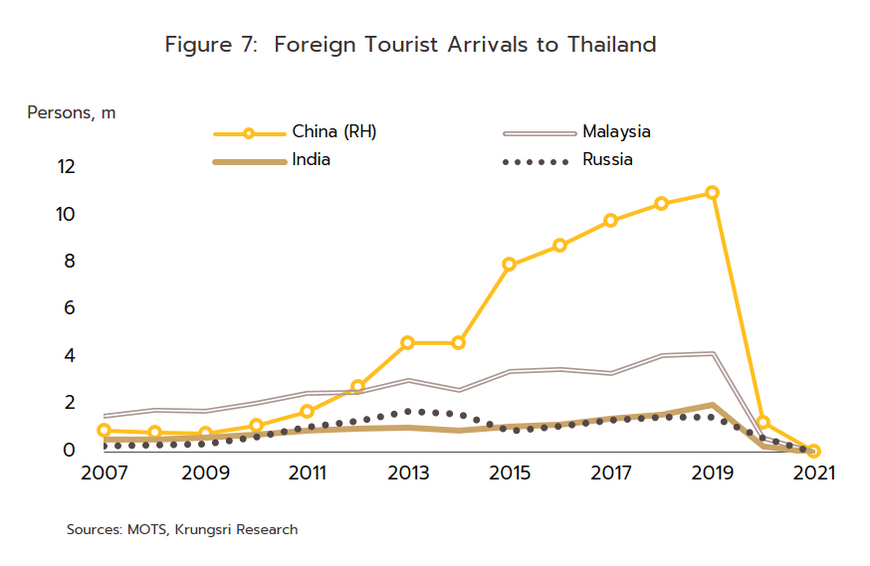

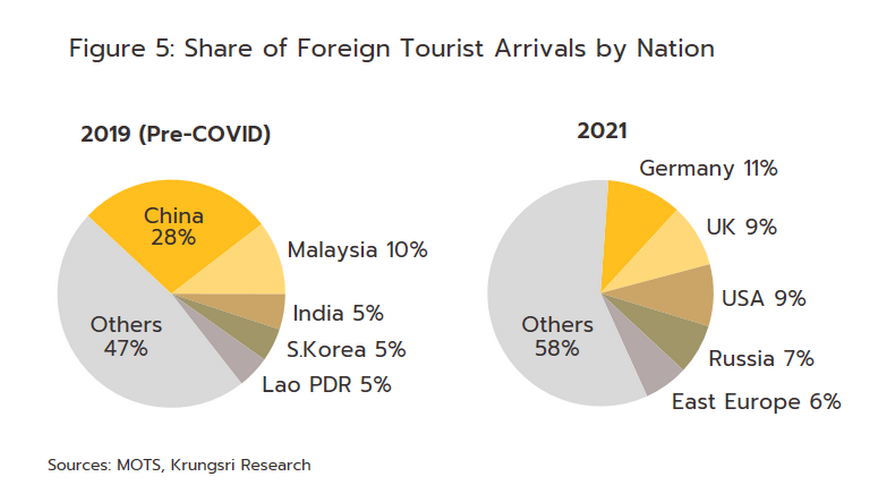

In 2019, prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, the most important markets were China, Malaysia, India and Russia, and together these accounted for 47.2% of all tourist arrivals. The pre-pandemic situation for these markets is thus described below.

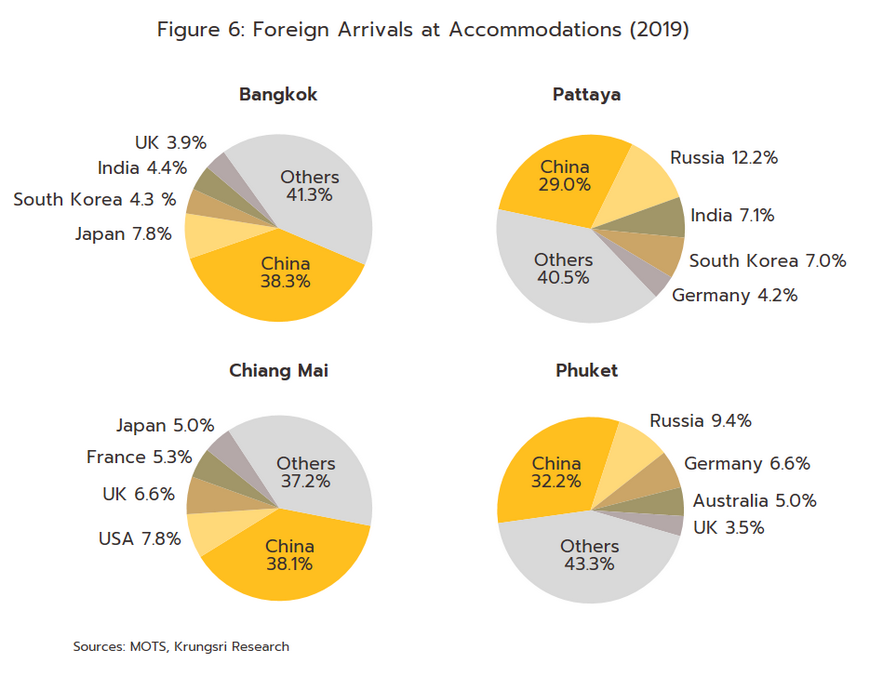

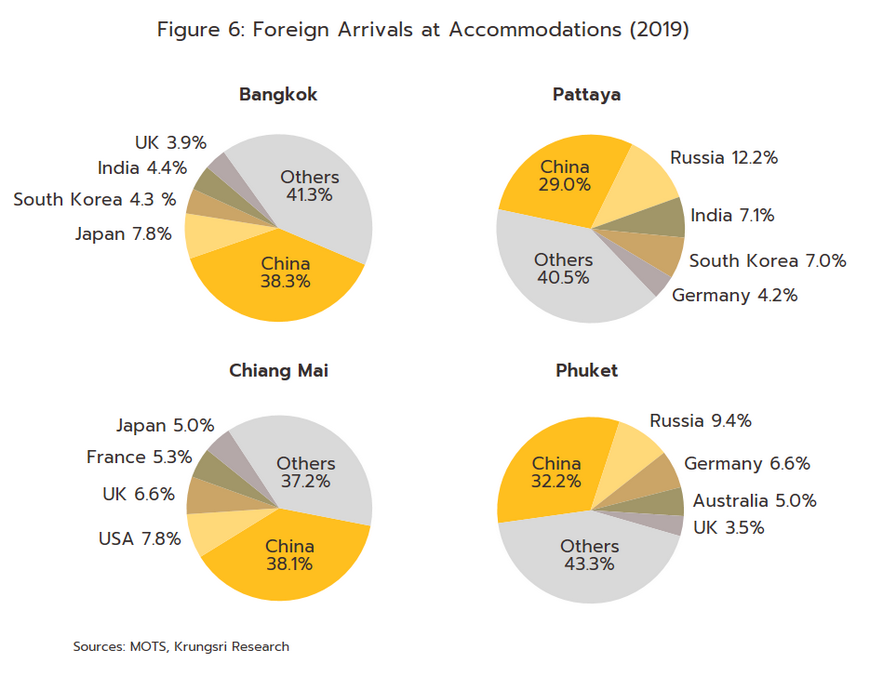

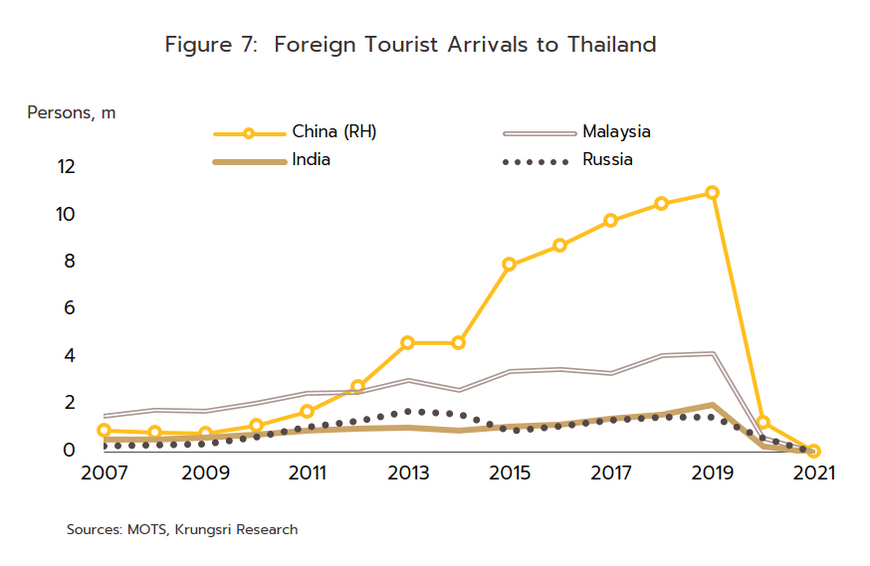

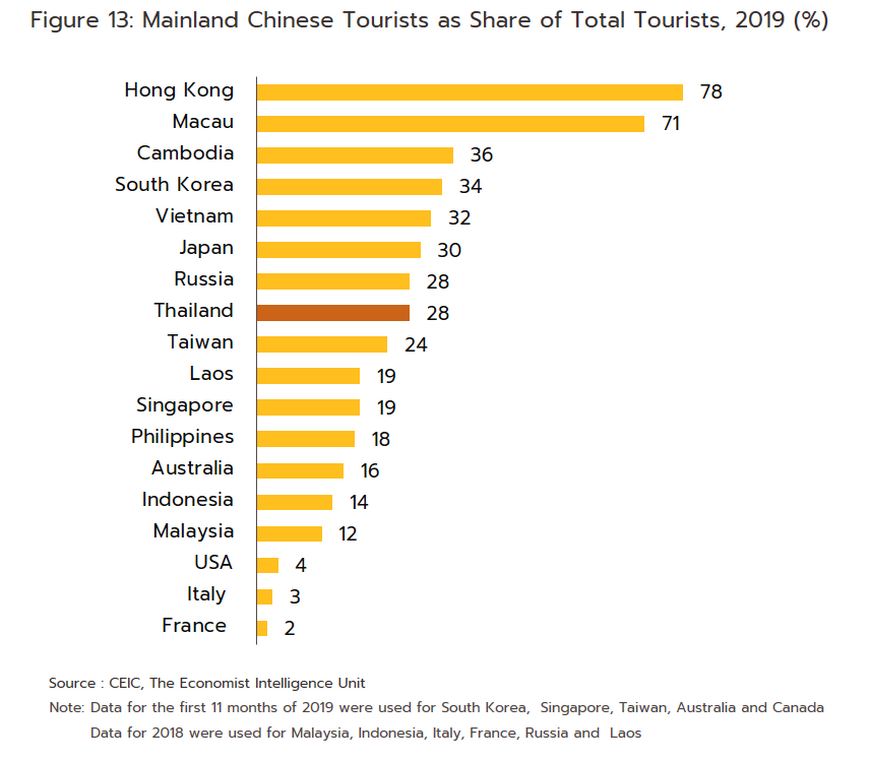

China: With 11 million Chinese tourists coming to Thailand in 2019 (28% of all foreign arrivals) and income from these totaling THB 540 billion, China was Thailand’s most important market for tourism (Figure 5), but this dominance is a recent development and the Chinese market has expanded more than ten-fold since 2007. Chinese visitors were also the most important segment in many of Thailand’s major tourism destinations (Figure 6). A number of factors had combined to encourage Chinese visitors to come to Thailand in ever greater numbers, including: (i) the relaxation of regulations on outbound tourism[2] ; (ii) the rapid growth of the Chinese economy and the equally rapid expansion of the Chinese middle class from 80 million in 2002 to 700 million in 2020 (source: Statista); and (iii) the increasing number of low-cost carriers and direct flights linking Thailand and China. Several ‘pull’ factors had also affected the market, including: (i) Thai government policies to promote tourism, for example the waiving of fees for issuance of visas on arrival (VOAs) for Chinese citizens; and (ii) marketing efforts by the Thai authorities that aimed to encourage visits by Chinese tourists, such as the ‘road shows’ in Chinese cities and the presence of Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) offices in Beijing, Shanghai, Kunming, Chengdu, and Guangzhou.

Malaysia: Malaysia had been Thailand’s second most important tourist market pre-COVID, and in 2019, income from Malaysian tourists alone totaled THB 110 billion (10.5% of the total), compared to THB 140 billion from all CLMV tourists combined. Indeed, until it was overtaken in importance by China in 2012, Malaysia had been Thailand’s most important tourism market. Tourism from Malaysia has been helped by the strength of cross-border Thai-Malaysian trade and the opening of travel lines connecting the two countries (e.g., the Kuala Lumpur-Chiang Mai air route) (Figure 7).

India: With a 5.0% share in 2019, India was Thailand’s 3rd biggest market. Before the pandemic, this segment had been growing strongly and for the five years from 2015-2019, the Indian market sustained double-digit growth, generating annual receipts of THB 86 billion in 2019. This growth has been supported by several factors. (i) India’s economy has been performing well, and with this the middle class is expanding. The Indian National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) estimates that as of 2016, 267 million Indians qualified as middle class, and this is forecast to explode to 547 million by 2025-2026. (ii) Growth in the market has been helped by the expansion in services provided by low-cost airlines, and flying between Thailand and Indian cities including Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Bangalore takes just 4-5 hours. (iii) Indians, and especially the wealthy, prefer to hold marriage ceremonies in Thailand due to its cheaper accommodation and overall lower costs compared to India or elsewhere.

Russia: Before the pandemic, the Russian market generated THB 100 billion in income and accounted for 3.7% of all foreign arrivals in 2019, making it the most important component in the European segment. Thanks to a combination of several factors, the Russian market also has potential for continued growth. (i) Unrest in the Middle East had the effect of encouraging Russian tourists to switch from travel destinations such as Turkey and Egypt that had previously been popular to travelling to Thailand instead. This was especially the case during 2010-2013, when the number of Russian arrivals jumped by an average of 46.1% per year, compared to annual growth of 22.5% between 2006 and 2009. (ii) The Thai government has promoted Thailand as a tourist destination to Russians by signing an agreement with the Russian government to allow visa-free tourism between the two countries for periods of up to 30 days (with effect since April 2007) and by putting on TAT roadshows in Russia. (iii) There had been an increasing number of direct and charter flights between Russia and Thailand.

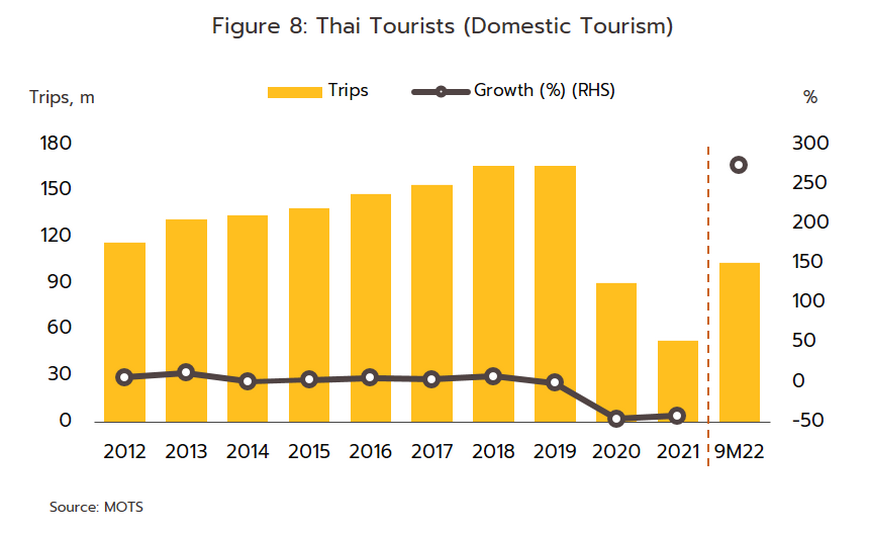

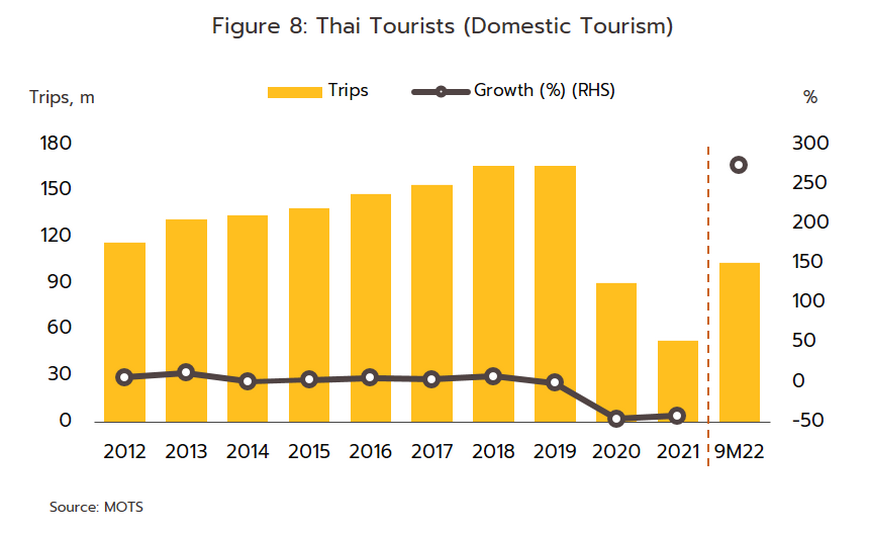

As regards domestic tourism, over the years from 2012-2019, annual growth averaged 5.5% in terms of the number of trips made within Thailand by domestic tourists, and this total had reached 144.8 million by the end of the period (Figure 8). Growth in the domestic market had been supported by: (i) ongoing efforts to encourage tourism, including the government’s introduction of tax allowances for expenditure on domestic tourism and the private sector’s promotion of domestic tourism through annual travel fairs; (ii) the expansion in the services offered by low-cost airlines and the upgrade and development of provincial airports; and (iii) easier access to tourist sites for independent travelers thanks to improvements in national communications networks, especially the road system. However, with the outbreak of COVID-19 and the resulting imposition of lockdowns, curfews, and prohibitions on travel between provinces, domestic tourism contracted by -43.6% per year over 2020 and 2021.

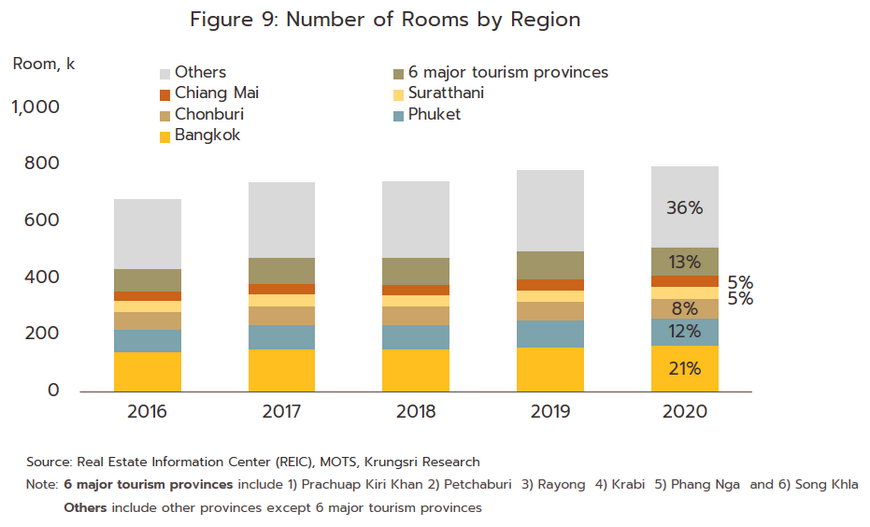

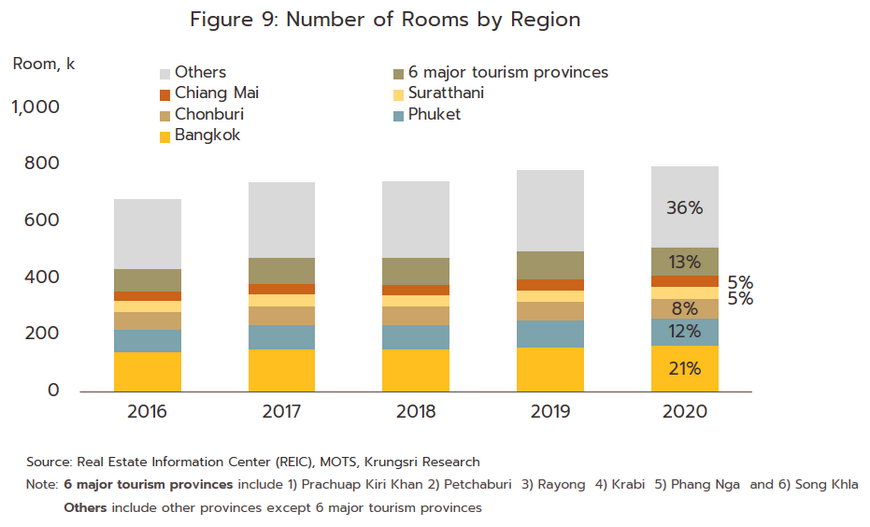

The pre-COVID expansion of the tourism sector fed into growth in the number of hotels and a rise in the number of rooms in the major tourist centers. Foreign tourists tend to be concentrated in Bangkok, which is both a center of tourism in its own right and the national travel hub, and the world-famous seaside resorts of Phuket and Pattaya (in Chonburi province). However, over the recent past, official policy has been to push through the development of tourism across the country (for example, in second-tier tourist centers) and to improve the standards of regional airports and the national transport network. This has then attracted inflows of private-sector investment to hotels in regional centers and in tourist areas such as Chiang Mai, Krabi, and Ko Samui (in Suratthani province). The net effect of this was then to increase the national supply of hotel rooms from 682,824 in 2016 to 799,894 in 2020, which represented average annual growth of 4.3% (Figure 9), down slightly from the 5.5% maintained over 2012-2015. However, through 2018-2020, growth in the supply of hotel rooms slowed to 2.5% per annum, compared to 10.6% over 2015-2017 as prices for land rose and sites suitable for development became harder to find. Given this, rooms provided by both Thai and international hotel chains continue to be concentrated in the major tourist areas (Figure 10), and as of 2020, 65% of all hotel rooms in Thailand were found in the 11 most important province[3]. The greatest concentration of these was in Bangkok, which was home to 165,870 rooms (21% of the total), followed by Phuket with 93,348 rooms (12%), Chonburi with 71,748 rooms (9%), Suratthani with 41,067 rooms (5%), and Chiang Mai with 38,741 rooms (5%).

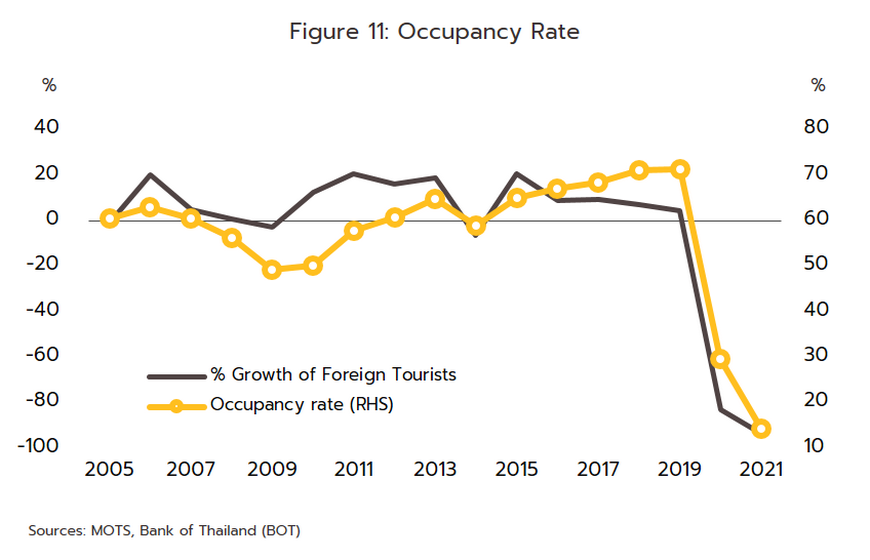

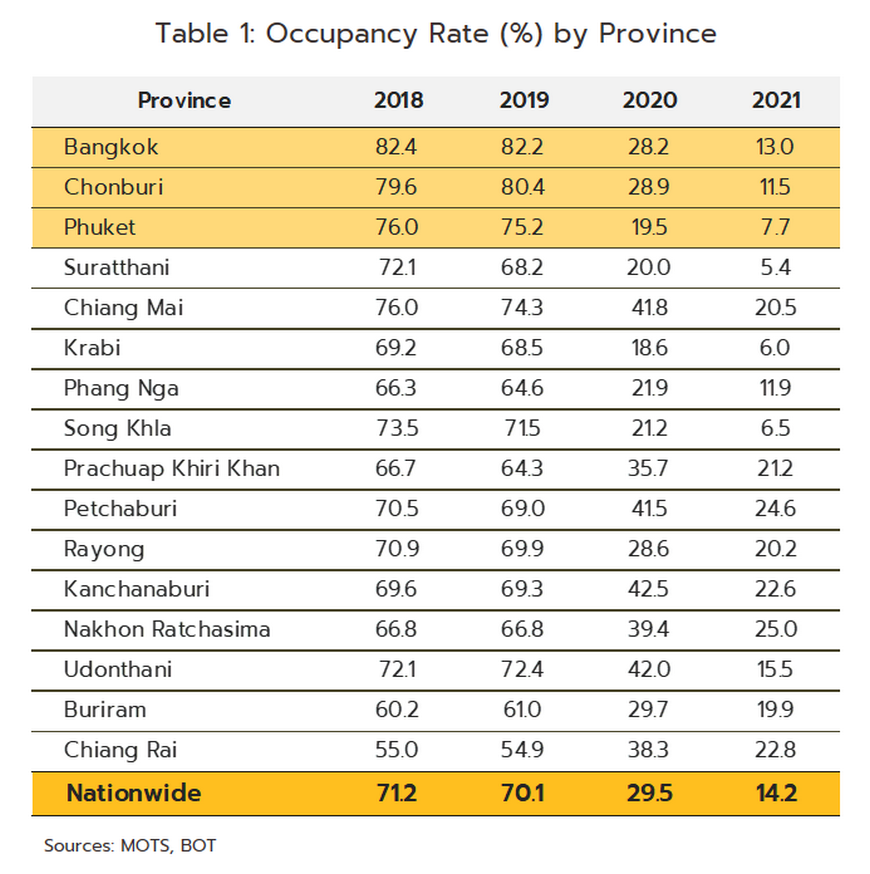

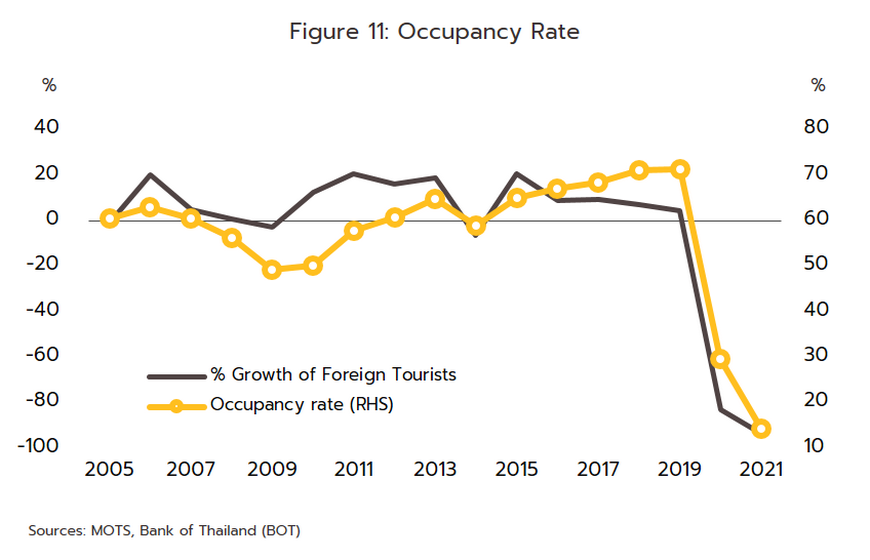

Occupancy rate (OR) fell sharply in 2020-2021. Over 2007-2019, the normal occupancy rate (OR) for the country as a whole tended to run in the range 60-70%[4]. However, this was also subject to the influence of external circumstances, such as the political crisis that rocked the country over 2009-2010 when the occupancy rate hovered around 50%, the coup in 2014 when it dipped to 55%, and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 when it crashed to 29.5%. Worse, the occupancy rate then slipped further, hitting just 14.2% in 2021 as both domestic and international tourists disappeared from the market (Figure 11).

SITUATION

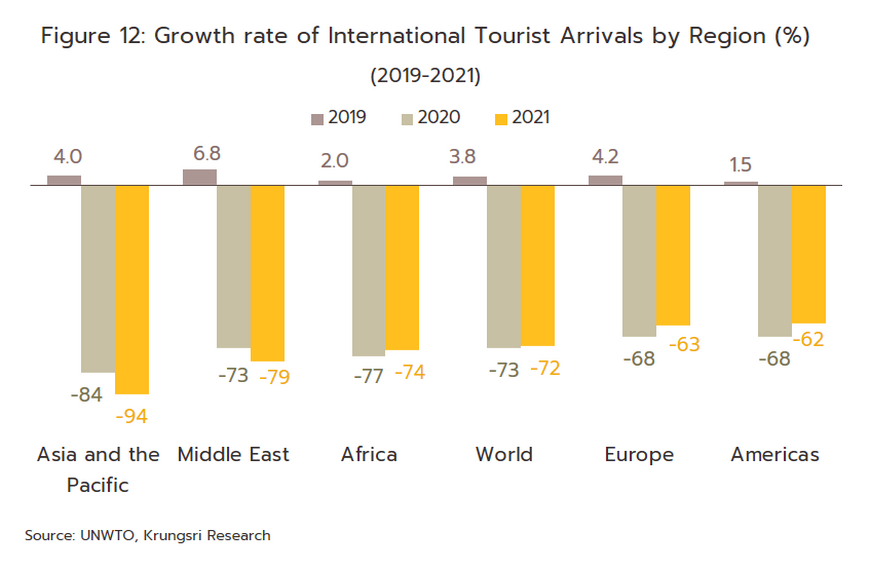

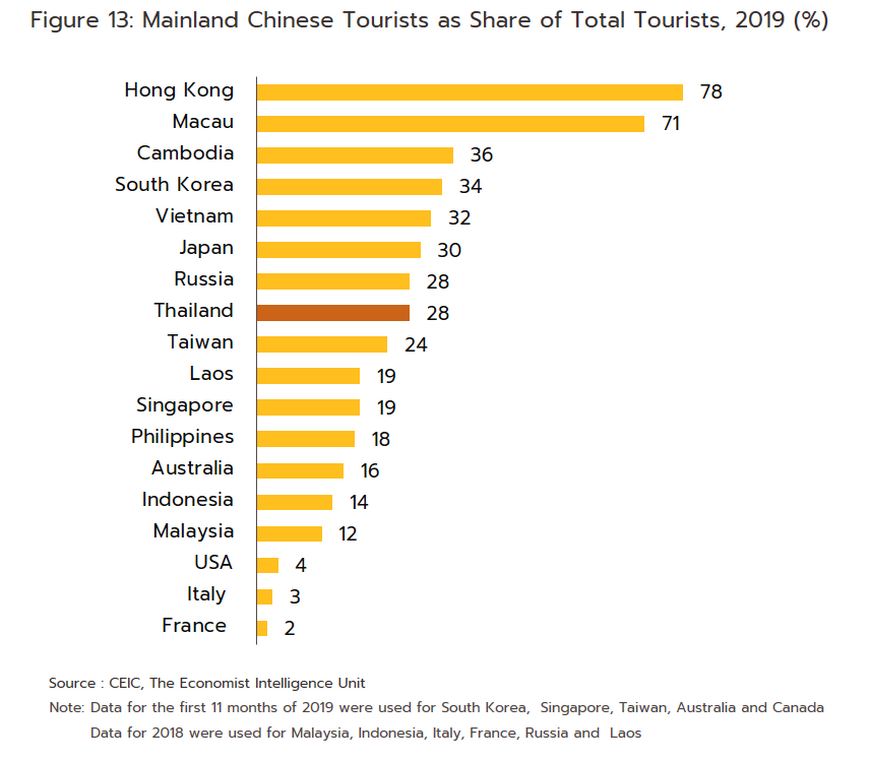

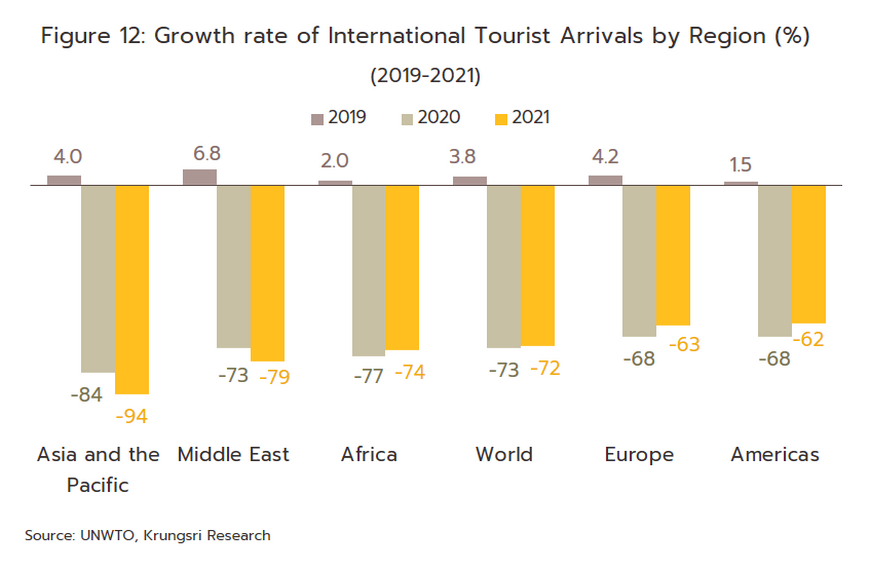

For hotel operators and players in the tourism industry, the crisis that began in 2020 with the initial outbreak of COVID-19 extended into 2021. Over these two years, governments around the world continued with their attempt to control the spread of the virus by implementing lockdowns and imposing restrictions on international travel. Because of this, the number of international tourists globally fell -72% in 2021, having already slumped -73% in 2020 (Figure 12). This decline was particularly intense in Chinese market due to the Chinese government’s decision to maintain tight controls on international travel from the start of the pandemic onwards, and the effects of this were especially noticeable in the Asia Pacific region. In these countries, the absence of Chinese travelers (on whom local tourist industries are generally highly reliant) led to a -94% collapse in the market (Figure 13). Individual countries affected by this thus included Malaysia (foreign arrivals were down -96.9%), Japan (-94.0%) and Singapore (-87.9%).

Thailand did not escape this general trend, and the global situation meant that the local market for tourism and hotel industries remained severely depressed over 2021.

-

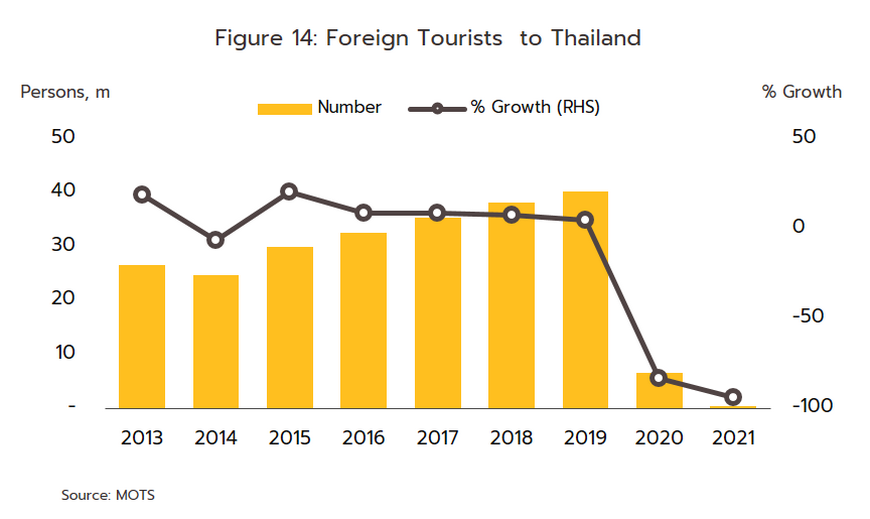

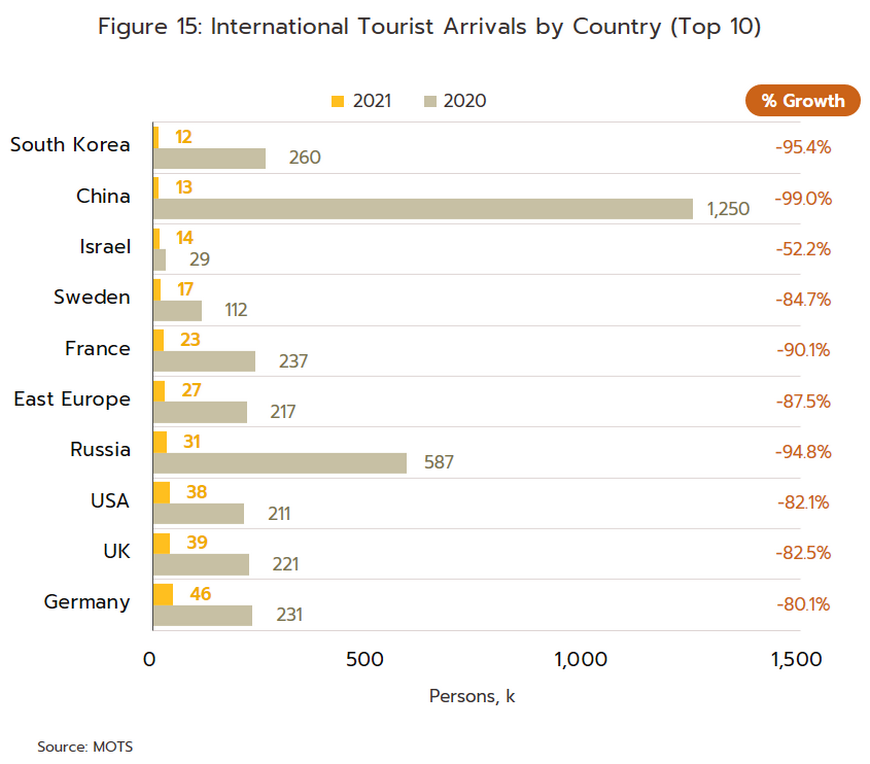

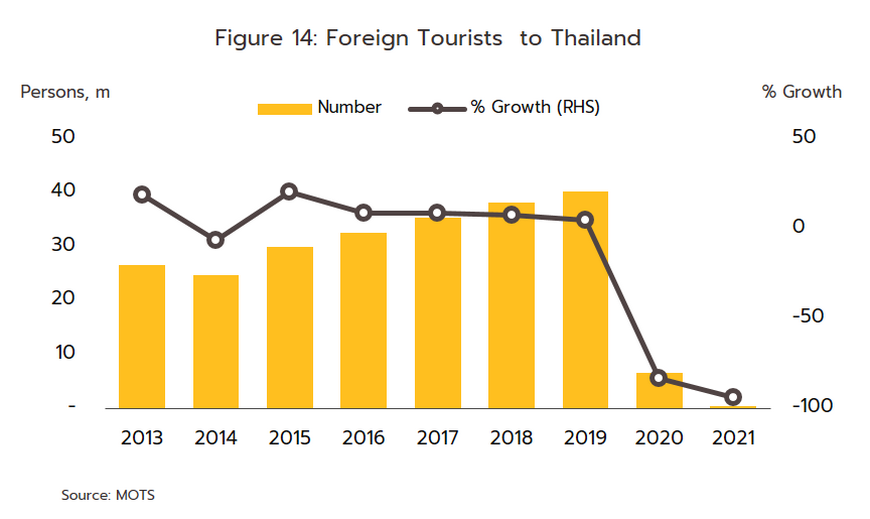

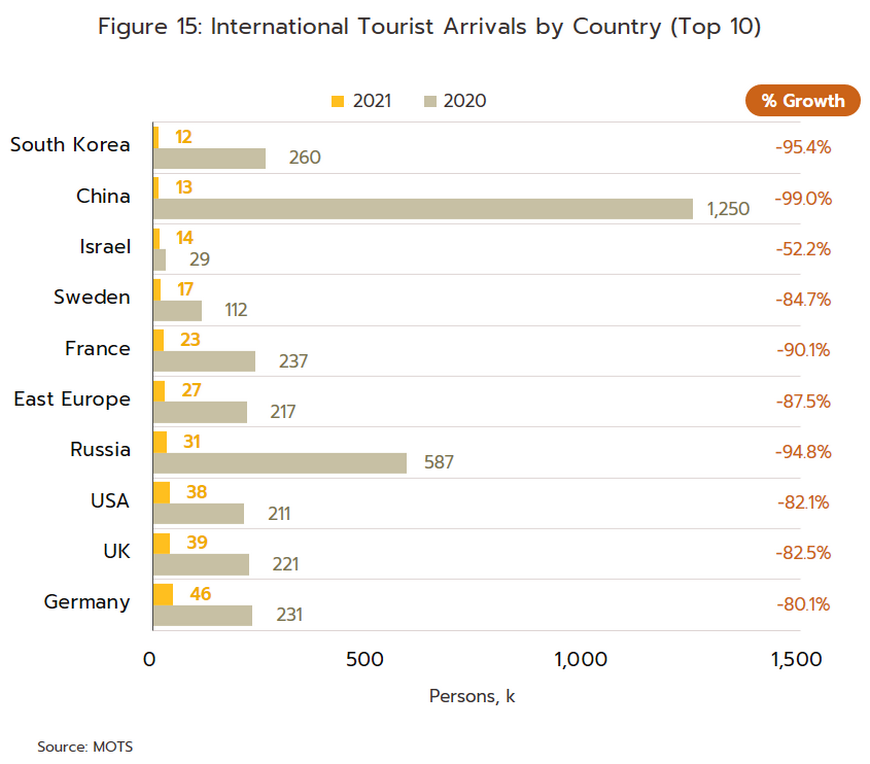

In 2021, tourist arrivals crashed -93.6% to just 0.43 million, having already contracted -83.2% to 6.7 million in 2020 (Figure 14), and this then generated receipts of just THB 38 billion (-88.6%). However, the figures for arrivals began to improve in the second half of the year as the government relaxed some COVID-19 controls by cutting the number of days that arrivals were required to stay in quarantine, allowing tourists to travel to a greater number of destinations, and instituting a number of schemes to help hotels and to attract tourists back to Thailand. This included the Phuket Sandbox (from July 1, 2021), the Samui Plus Model (from July 15, 2021), and the Phuket Sandbox 7+7 Extension Program (from August 16, 2021). At the same time, vaccine rollouts were making considerable progress and many countries were loosening controls on outbound tourism and so this too boosted the Thai tourism sector. In terms of individual countries, Germany was the most important market in 2021 with 11% of the total (or 46,000 visitors), followed by the UK (9%), the USA (9%) and Russia (7%) (Figure 15).

-

The domestic segment also suffered badly in 2021, and across the year, Thai tourists made just 53.0 million trips domestically, a drop of -41.4% (Figure 8). Unfortunately, income was down even more, falling -60.6% to THB 220 billion. The contraction was sharpest in the third quarter, when an average of just 1.1 million trips were made each month, compared to the 8.1 million trips/month made during the third quarter of 2020. Naturally, this was attributable to the severity of the pandemic and the introduction of lockdowns and curfews, and the postponing or cancelling of inter-province travel. The situation began to improve in the last quarter of the year with the loosening of these controls and the introduction of policies that aimed to stimulate the domestic market (e.g., phase 4 of the ‘We Travel Together’ program, which ran from October 1, 2021, to January 31, 2022). For the quarter, Thais therefore made an average of 8.5 million domestic trips per month.

-

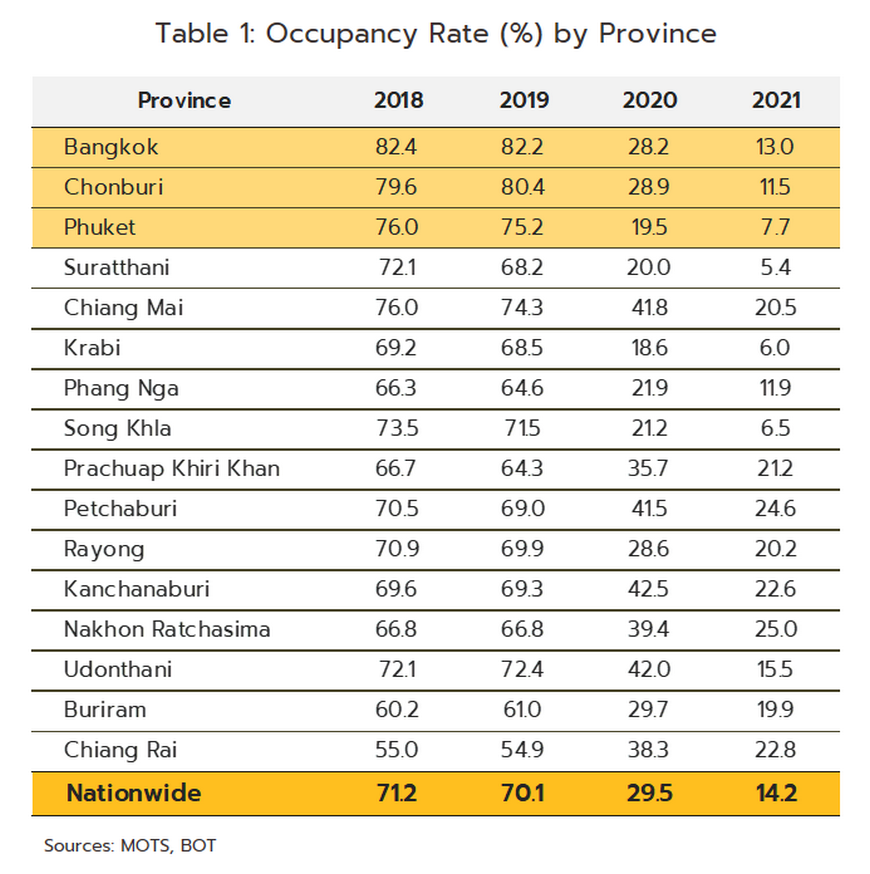

The average national occupancy rate also crashed to a historic low of 14.2% in 2021, down from the already low 29.5% seen in 2020 (Figure 11). The situation was even worse in major tourist areas such as Phuket, Suratthani, and Krabi, where operators are especially reliant on overseas visitors. In these areas, the occupancy rate fell below 10%. By contrast, provinces such as Phetchaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Kanchanaburi, and Nakhon Ratchasima are more dependent on the domestic market and so in these areas, occupancy rates typically remained above 20% (Table 1).

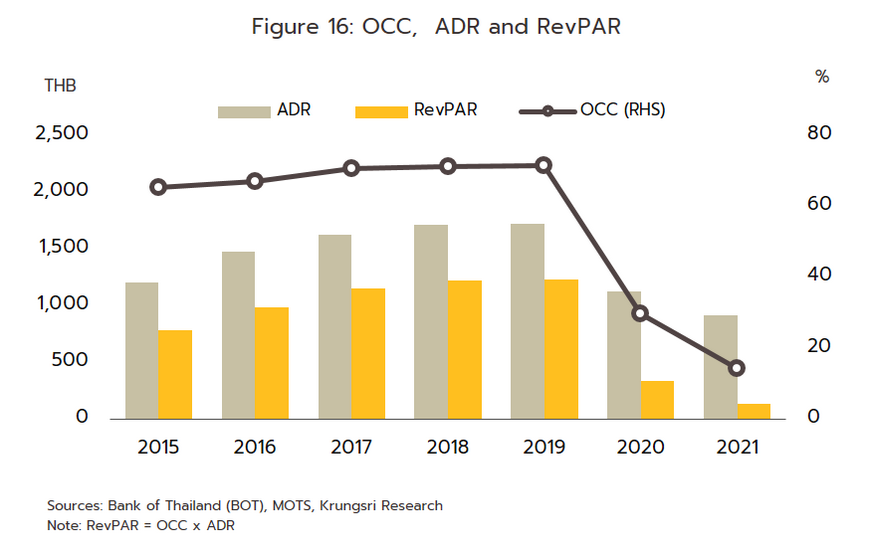

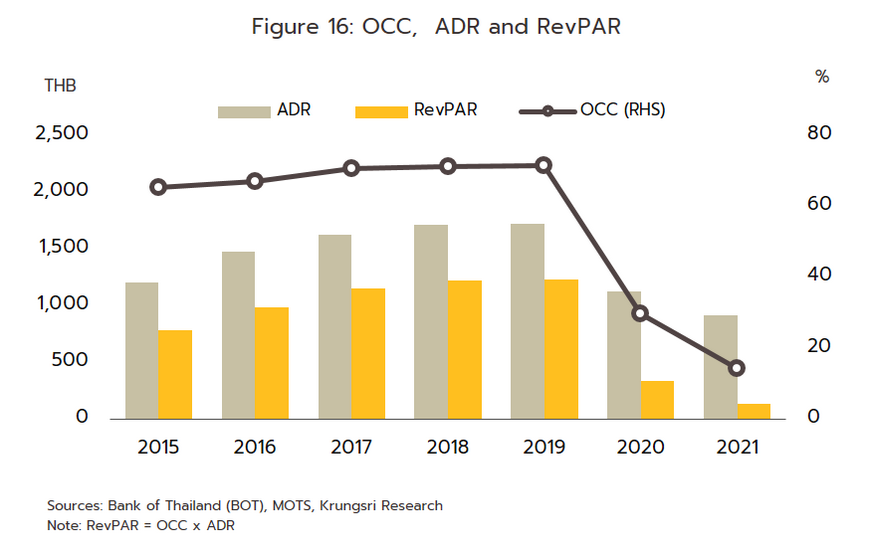

- Average daily rates (ADRs) across the country dropped -18.5% to THB 914, and this then helped to slash revenue per available room (RevPAR) by -60.9% to THB 129, down from THB 311 in 2020 (Figure 16).

-

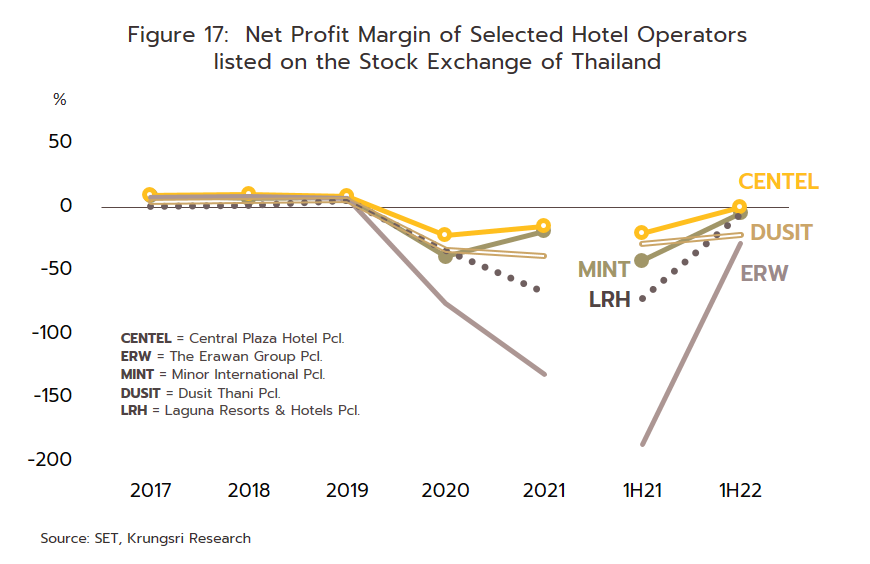

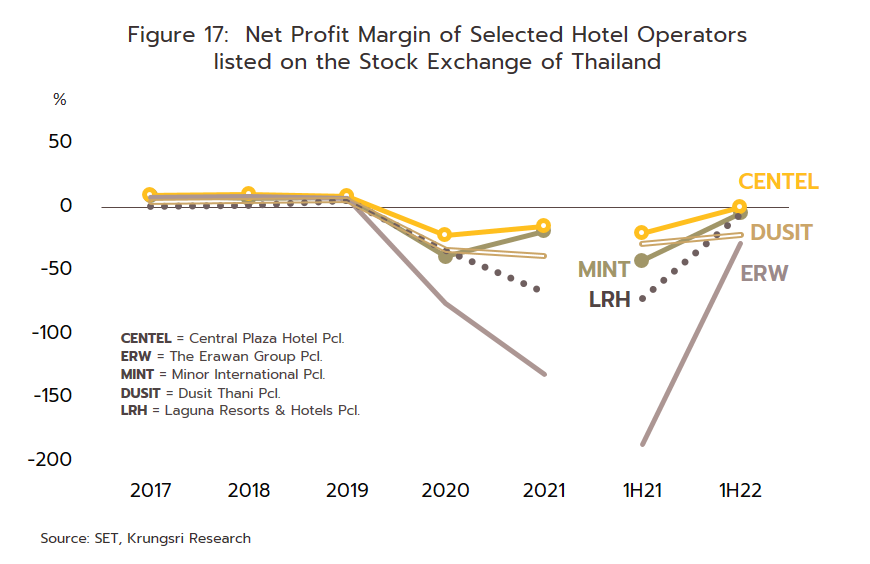

Returns were therefore depressed for hoteliers throughout the period, and for the five hotel operators registered on the Thai stock exchange, net profits dropped -54.1% in 2021, which came on the heels of a -40.7% contraction in net profits a year earlier (Figure 17). However, the impacts of this difficult business environment varied from one business to the next depending on the structure of companies’ income streams and the extent to which their businesses were diversified. Thus, because Central Plaza Hotel (CENTEL) and Minor International (MINT) were able to generate additional income from other sources (e.g., sales of food and the distribution of fashion goods), their bottom line was less severely affected than was that of other players.

-

In response to these difficulties, businesses were forced to overhaul their operations by cutting room rates, revising their service operations, slashing their overheads, and developing alternative income streams. Thus, many hotels began to offer ‘work from hotel’ packages to meet the sudden uptick in working from home, and to work with food delivery apps to develop their ability to sell food prepared in their own kitchens, though this was largely restricted to 4- and 5-star hotels. In addition, many hotels in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region partnered with clinics and hospitals to offer ‘alternative state quarantine’ (ASQ) services, while hotels in Phuket, Suratthani (i.e., Ko Samui), Chonburi (i.e., Pattaya), Prachinburi, Buriram, Chiang Mai, and Phang-nga moved to set up ‘alternative local state quarantine’ (ALSQ) services. Both the ASQ and ALSQ services were targeted at foreign travelers coming to Thailand who were required by law to quarantine on arrival. Unfortunately, many smaller and medium-sized businesses were not able to adapt in these ways and faced with unprecedented difficulties, a significant number were left with no option but to shut their operations.

The situation has continued to improve over the first 9 months of 2022, and signs of recovery are becoming increasingly evident in the tourism sector. Details of this recovery are given below.

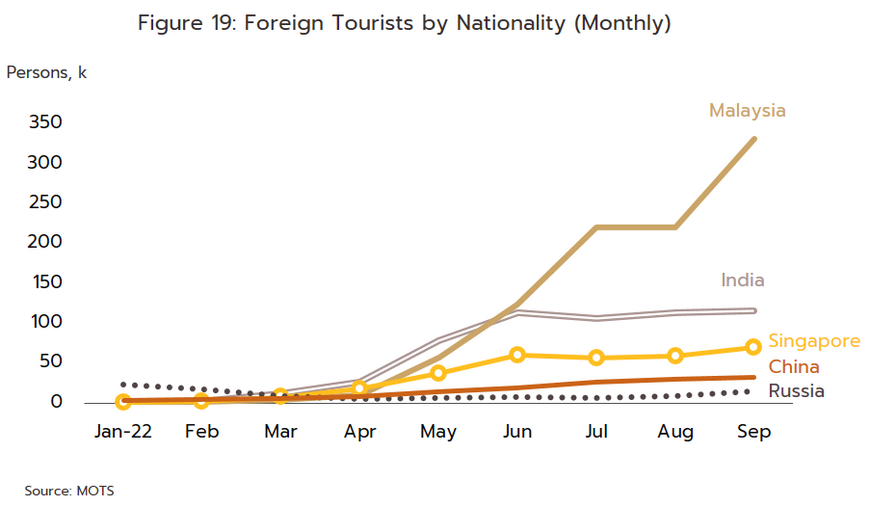

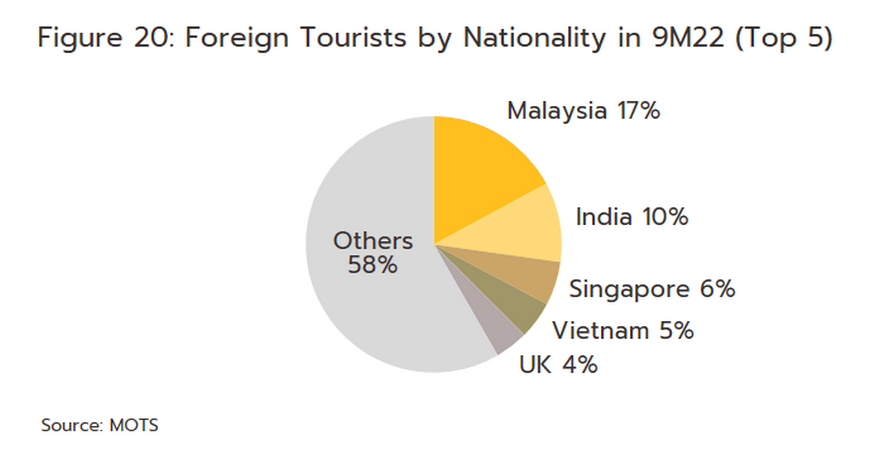

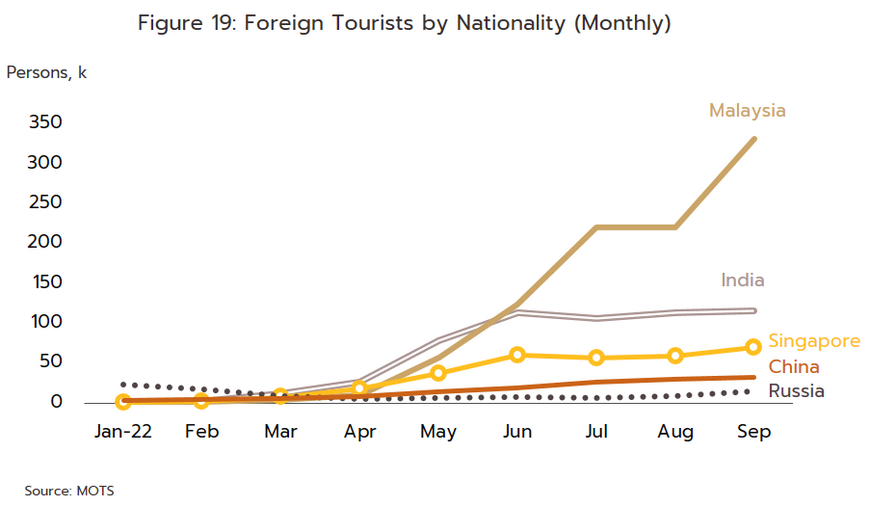

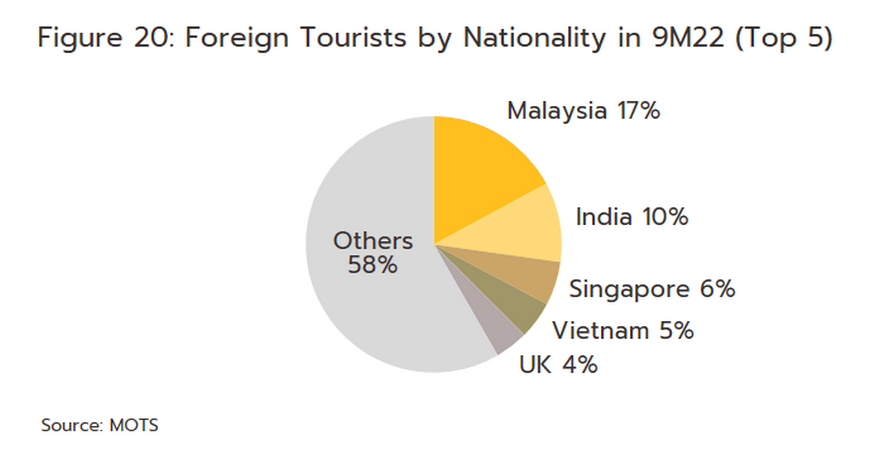

- The number of arrivals has continued to strengthen since the start of 2022 (Figure 18) and as of 9M22, 5.7 million arrivals have been recorded, up from just 85,845 a year ago. The market has been stimulated by: (i) the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions by the Thai government, including the ending of the Test & Go system for fully vaccinated arrivals from May 1, 2022; (ii) the ending of restrictions on outbound travel in many originating countries; and (iii) the creation of a ‘travel bubble’ connecting Thailand and India in March 2022, which since April has helped to steadily increase the number of arrivals from India (Figure 19). In addition, thanks to the April-1 opening of the land crossing Between Thailand and Malaysia, Malaysia has been the most important originating country for arrivals to Thailand since June (Figure 19). Thus, for 9M22 in total, 0.97 million Malaysian tourists have come to Thailand, representing 17% of all foreign arrivals, and followed in importance by India and Singapore respectively (Figure 20).

However, despite this broadly positive outlook, the outbreak of war in Ukraine in February has severely restricted the Russian market, and instead of the 7% share of all arrivals seen in 2021, Russians accounted for just 2% of foreign tourists coming to Thailand over 9M22. Likewise, China’s continuing pursuit of its Zero-COVID policy means that the 28% share attributable to the Chinese market in 2019 had shrunk to just 3% by 9M22.

-

Thai tourists took a total of 103.4 million domestic trips in 9M22, which represented an increase of 274.2% YoY. This was largely attributable to the easing of pandemic restrictions and the continuation of government measures that aimed to stimulate domestic tourism, including the extension of phase four of the We Travel Together program (July-October 2022) (Figure 18).

-

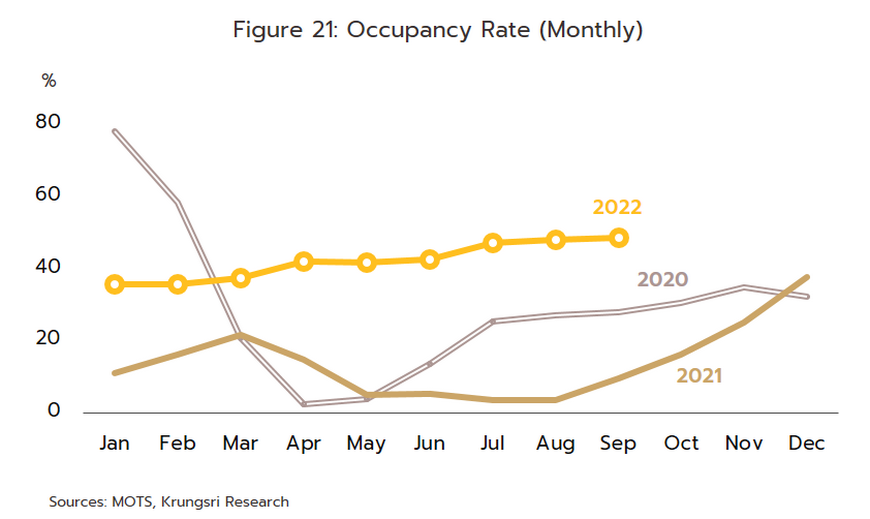

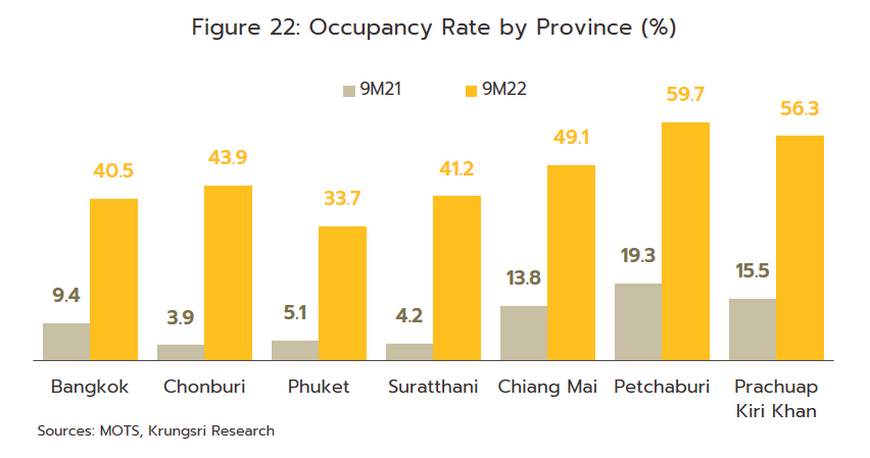

The occupancy rate has continued to strengthen, and this reached 42.0% in 9M22, up from just 9.9% in 9M21 (Figure 21). The occupancy rate has improved across the country thanks to the increase in the number of both Thai and overseas visitors (Figure 22). However, compared to the pre-COVID period, the occupancy rate remains very weak (i.e., over 9M19, the national occupancy rate was 71.1%). Average room rates also increased by 9.7% YoY, and this pushed revenue per available room to THB 417 compared to just THB 90 in 9M21.

-

For the five hotel operators registered on the SET, income grew but net profit margins continued to fall, though at a slower rate than previously (Figure 17). In the first half of 2022, combined income for these five companies jumped 82.8% YoY to THB 67 billion on recovery in tourist numbers, though the scale of the increase is attributable to last year’s low base. Average net profit margins remained negative at -12.0%, though this was an improvement on 1H21’s -70.0%.

OUTLOOK

The hotel industry will see an accelerating rate of recovery over 2022 to 2024 as it emerges from two years of deeply depressed conditions. Recovery in the overseas segment is predicted to be complete by 2025, by which time the number of foreign arrivals should be back to its pre-COVID level of 38-40 million annually. The domestic segment is rebounding more rapidly, helped in part by the effect of ongoing government stimulus packages, and it is now forecast to return to the pre-pandemic level of around 185 million trips annually in 2024. Operators of larger chains are also expected to move forward with their investment plans, though progress may be slower than initially imagined. Given this, the national occupancy rate is expected to reach an average of just 45% in 2022 before climbing to 55% in 2023 and 65% in 2024.

-

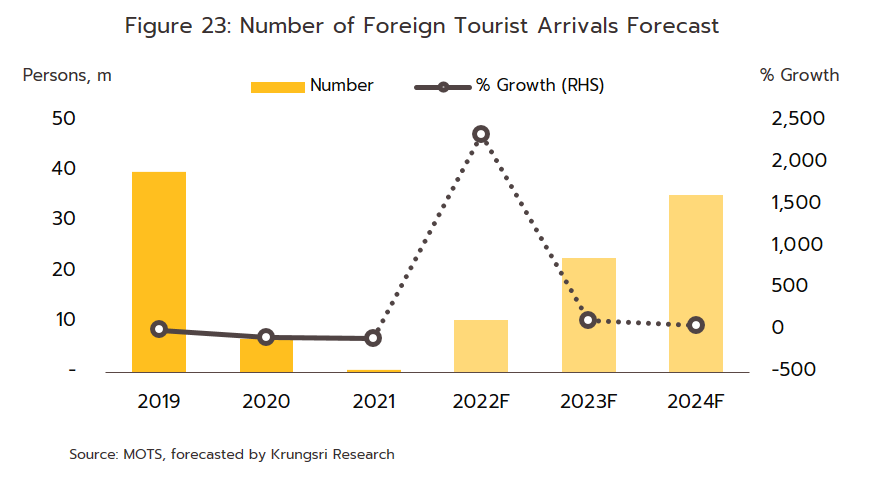

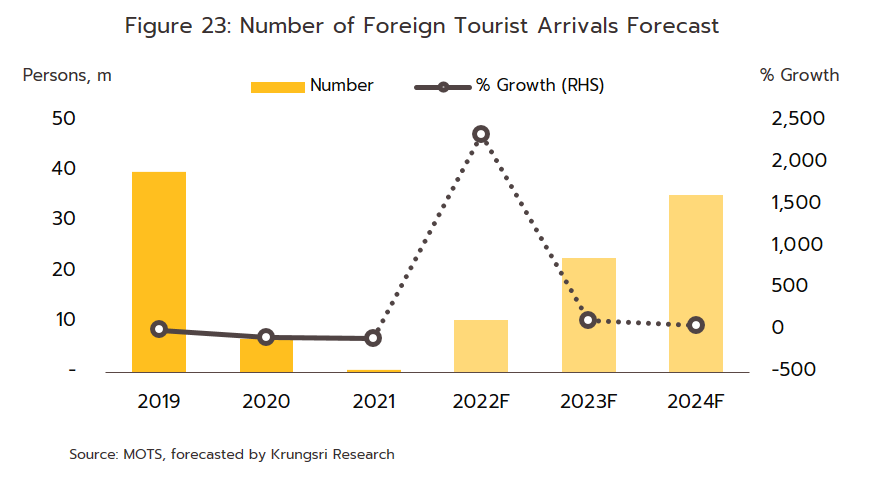

The number of foreign tourists coming to Thailand will increase at a quickening pace over the next few years. Krungsri Research therefore expects 10.4 million arrivals in 2022, and although this would be a sharp improvement on 2021’s total, it will still be significantly below the pre-COVID norm. This is because China, Thailand’s most important market for tourism, is still pursuing its zero-COVID strategy. In addition, weakness in the global economy caused by the war in Ukraine is also dragging on the tourism industry. The situation should improve over 2023 and 2024, when foreign tourist arrivals are forecast to increase to 22.7 million and 35.3 million, respectively (Figure 23). This recovery will be helped by the following factors.

1) The full reopening of Thailand on July 1, 2022, clearly helped to boost tourist arrivals, and this was especially noticeable in the main tourist destinations of Bangkok, Pattaya, and Phuket.

2) The successful rollout of vaccination programs has meant that most countries have now relaxed controls on international travel, and this has then rebuilt confidence in the tourism sector.

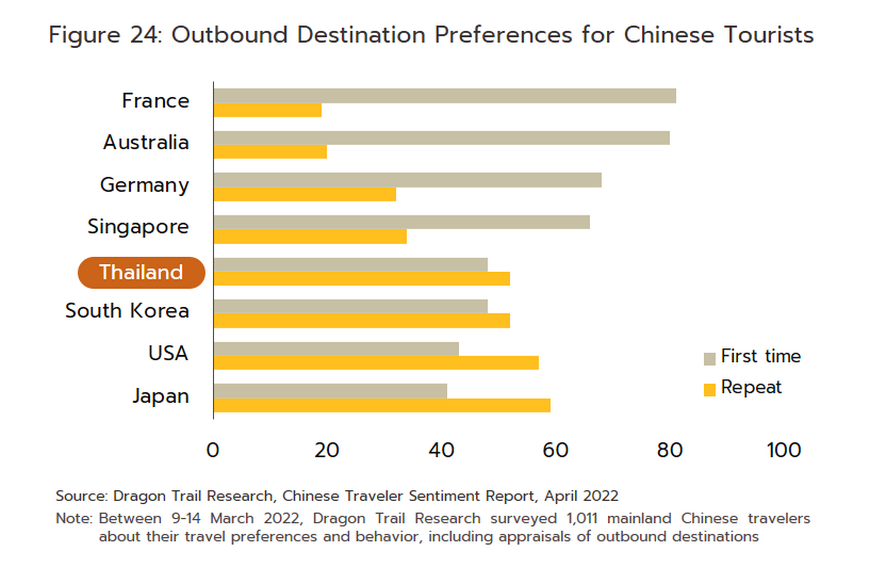

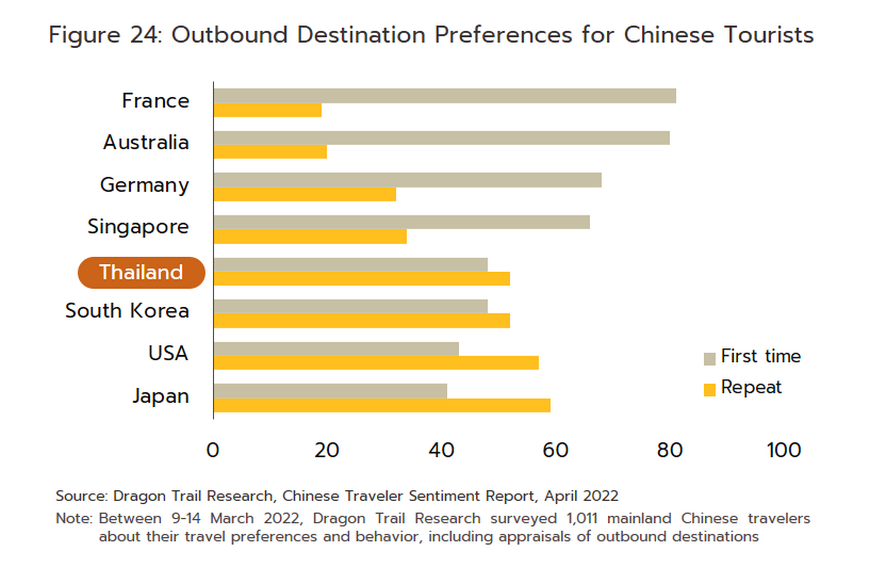

3) China, Thailand’s most important tourist market, is expected to begin relaxing controls on outbound travel in mid-2023 (Figure 24).

4) The government is continuing to use policy tools to stimulate the tourism sector by, for example, creating a travel bubble linking Thailand with major markets such as China and India, and running roadshows targeting new high-end markets, including in Saudi Arabia.

5) Thailand’s unique charms continue to support high levels of interest among travelers and to maintain the country’s position on the world stage as a widely admired tourism destination. The most recent Visa Global Travel Intentions study[5] found that Thailand was the world’s fourth most attractive tourist destination, coming after only the US, the UK and India, while TAT Newsroom (May 2022) reports that Bangkok, Phuket, Chiang Mai, and Hua Hin are among the world’s most googled travel destinations.

-

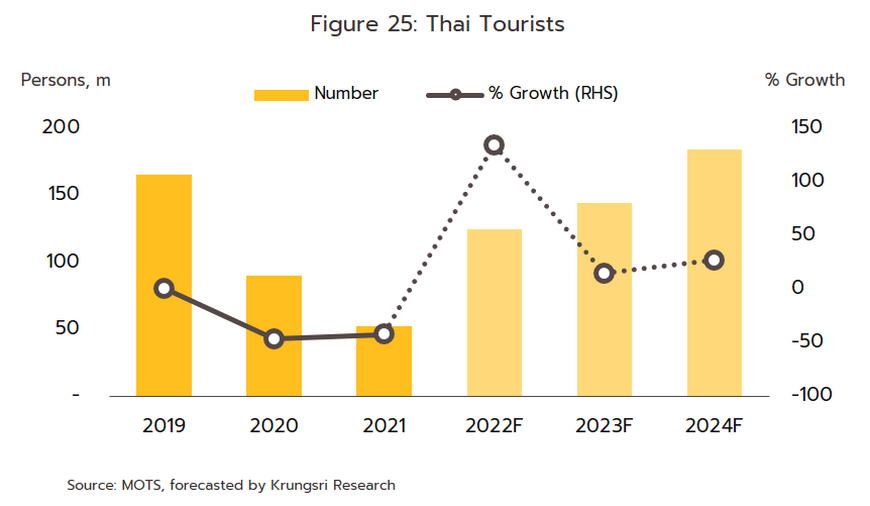

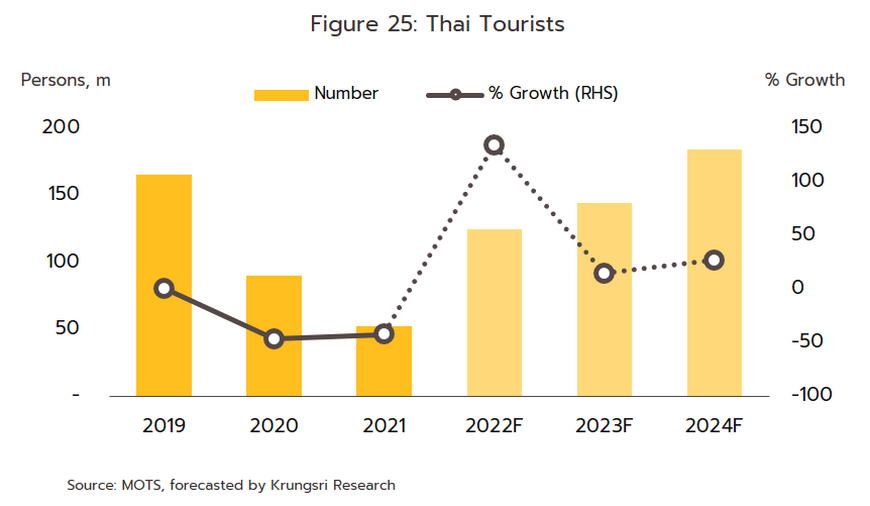

The domestic segment will also continue to strengthen. Because the number of foreign tourists will remain significantly below normal levels for all of 2022, businesses offering hotel and tourism services will remain dependent primarily on the domestic market. Krungsri Research sees Thai tourists making a total of 125 million domestic trips in 2022 and rising to 145 million in 2023 and 185 million in 2024, which would be somewhat higher than the 166 million trips recorded in 2019 prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 (Figure 25). This outlook is supported by the following:

1) Government measures to encourage domestic tourism will continue through 2022. This includes the ‘We Travel Together’ scheme, which has gone through various iterations since 2020 and is now in an extension to phase four of the program, and the designation of additional public holidays. These programs have proven to be very valuable for players in the tourism and hotel industries and will remain so as long as overseas markets are still depressed.

2) The development of national infrastructure will help to underpin an expansion in the tourism sector. Upgrades and expansions to provincial airports, and improvements to road and rail networks will be particularly important in achieving these ends, and one outcome of this will be to boost tourism in second-tier destinations.

-

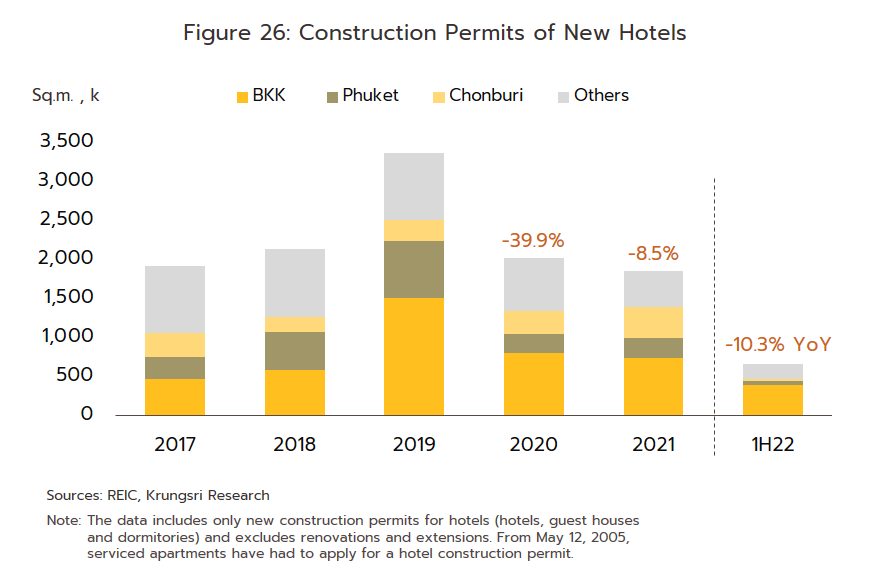

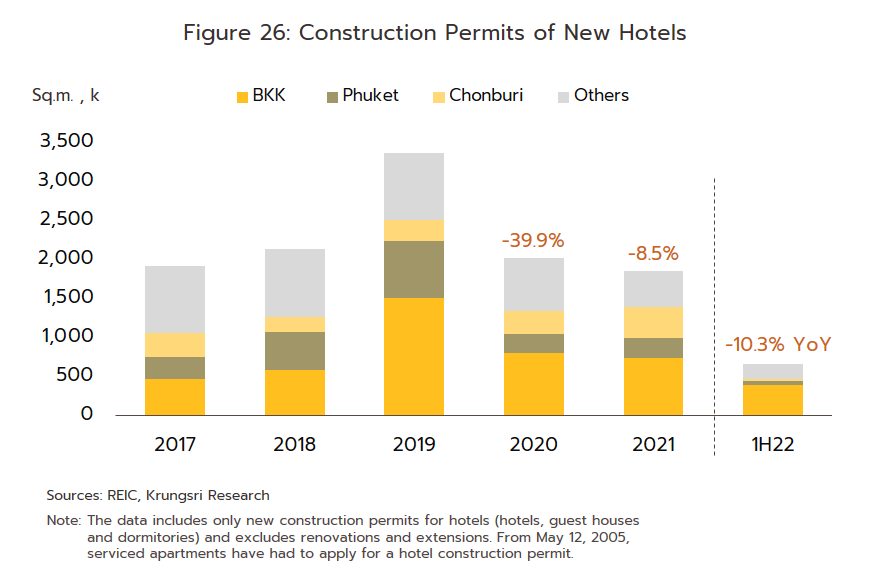

The expansion in the supply of new hotel rooms is tending to slow, as reflected in applications for hotel construction permits (these indicate new supply that will come to market in the next 1-2 years). In 2021, the total number of these permits fell -8.5% to 1.8 million sq.m. (Figure 26), 40% of which was for applications submitted in Bangkok totaling 0.75 million sq.m. or slipped -7.0% due to the weak state of the market, especially in the overseas segment. Bangkok was followed in importance by Chonburi, which had a 22% share, or a total of 0.4 million sq.m., although this was an increase of 38.3%; investment has risen in the EEC to meet anticipated future demand resulting from an expansion in industrial activity and tourism services in the region.

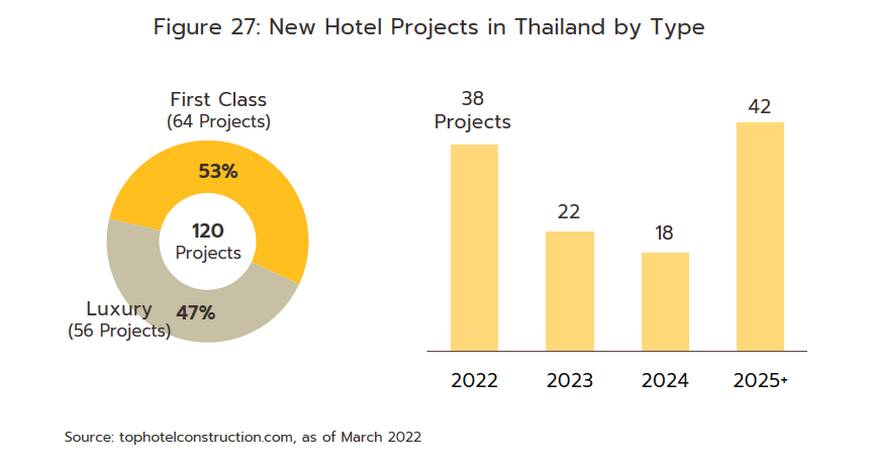

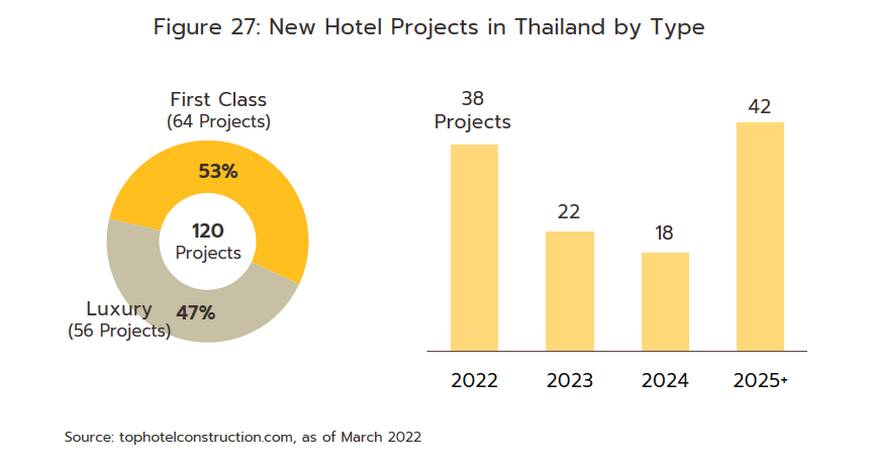

Investment in the industry is mostly being made by large operators in the construction of new hotels in regional centers, tourist areas, and border zones, where demand is being boosted by greater regional integration. These developments generally target the budget hotels and mid-range hotels (3-4 star) segments, and examples include Hop Inn (operated by Erawan Group), Fortune D (part of CP Land) and COSI (run by Central Plaza), although due to their continuing faith in the long-term potential of the Thai tourism sector, both Thai and international hotel chains are investing in new operations in the main tourist areas at all levels of the market from budget to luxury (Table 2). Investments are especially concentrated in destinations favored by the global market, such as Bangkok and Phuket. Data from the TOPHOTELPROJECTS construction database (data correct as of March 2022) indicates that over the period 2022-2026, 120 new hotels will open, adding 29,861 rooms to current supply. 64 of these (with 17,666 rooms) are in the ‘first class’ category, while 56 (with 12,195 rooms) are classified as ‘luxury’ developments (Figure 27). Considered by area, 47 hotels (12,089 rooms) are in Bangkok, 16 (3,383 rooms) are in Phuket, and 15 (4,896 rooms) are in Chonburi/Pattaya. 38 of the total are expected to open in 2022, though the greatest number of new openings will be in 2025, when 42 new hotels will begin operations. Nevertheless, the aftereffects of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to be felt, and this and the weak state of the world economy may combine to delay progress on some investment projects.

- In 2022, occupancy rates will remain at the low level of around 45%, though they will steadily improve over 2023 and 2024 (Figure 28). However, in the main tourist areas, the occupancy rate will likely remain below the normal level of 70-80% due to the only incomplete recovery in the international segment. This will be due to ongoing restrictions on travel in originating countries, the still-fragile recovery in the international airline industry, and the move by many governments to stimulate their economies by encouraging an increase in domestic tourism.

-

Over the next three years, geopolitical conflict may pose a risk to the tourism sector. Potential problems will include rising tensions between the US and China over the fate of Taiwan and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. A worsening of the former or an extension of the latter may have negative consequences for the world economy, in particular by keeping oil prices elevated. This would add to travel costs, which would drag on both long-haul markets (i.e., Europe and the Americas) and domestic travel, with Thai tourists becoming increasingly careful about expenditure on travel.

-

Competition will tend to strengthen within the hotel industry, with this coming from two separate sources.

1) Competition from other hotels will intensify as a result of investments continuing to flow into major tourist areas and regional centers. This is coming both in the form of investments made by hotel operators themselves and those who will appoint a third-party hotel management team to operate the hotel (generally from large operators that are part of extended commercial groups or that have their own chains).

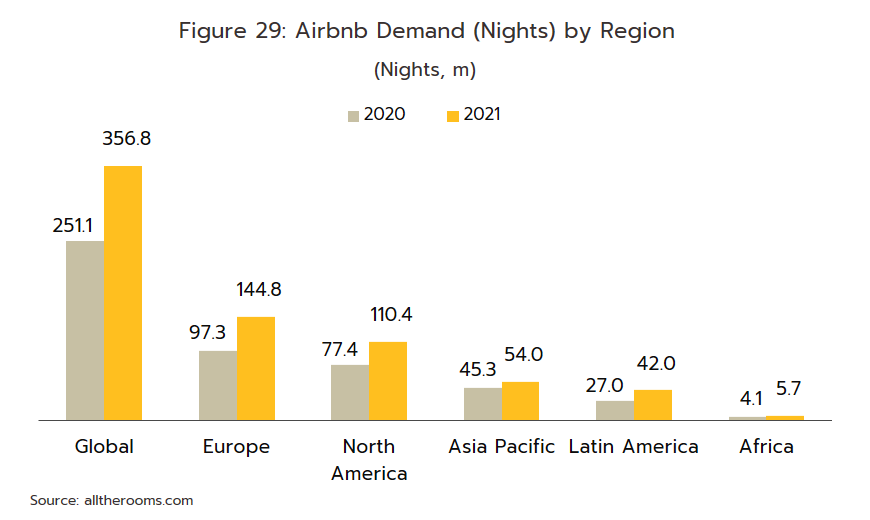

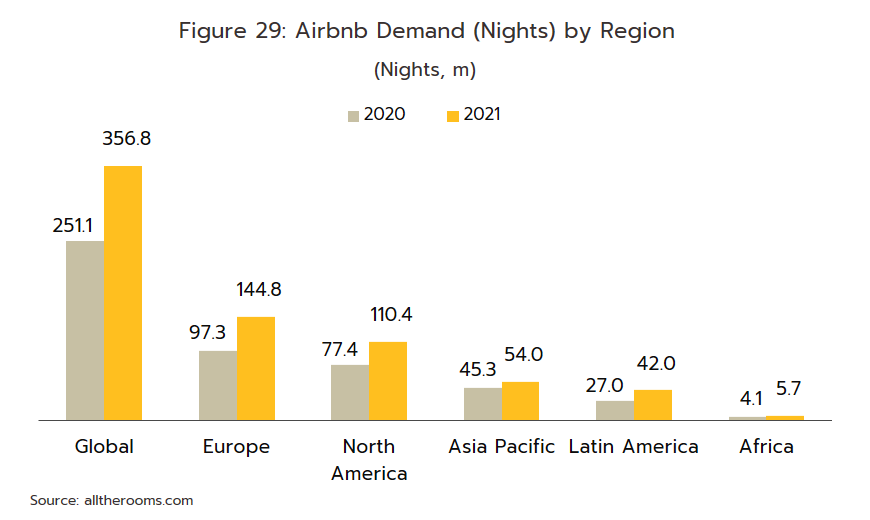

2) Although it is illegal under the Hotel Act B.E. 2547 (2004), hotels also have to contend with growing competition from alternative forms of short-term accommodation such as regular and serviced apartments and condominiums that are rented out by the day, generally with rates that undercut those of hotels. In addition, services offered by companies such as Airbnb are having an increasing impact on the market, with bookings made via Airbnb up 20% in the Asia Pacific region in 2021 (Figure 29). Unfortunately, because players will need to use more aggressive pricing strategies to attract visitors, income will suffer, especially for SMEs.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, a ‘new normal’ for the hotel industry is being established that will emphasize the maintenance of social distancing and reduced physical interactions. Because of this, returning to earlier ways of operating may not be sufficient to fully meet changing consumer needs, and operators in the tourism and hotel industries are thus moving their businesses onto a more sustainable long-term footing by making the following changes.

1) A greater utilization of modern technology will allow operators to respond better to varied and diverse consumer needs. This might include making life easier for visitors by allowing them to use technology to remotely control equipment and fittings in their room, for example by using internet-enabled devices that could be manipulated via a smartphone. This would be attractive to many, especially those in younger generations who use their smartphone as a central tool for interacting with the world. This could then be extended to allow visitors to use their phone to check in and make payments (thus avoiding the need to contact staff at the main counter), to control heating and lighting, and to gain access to their room (i.e., by using their phone as a contactless key).

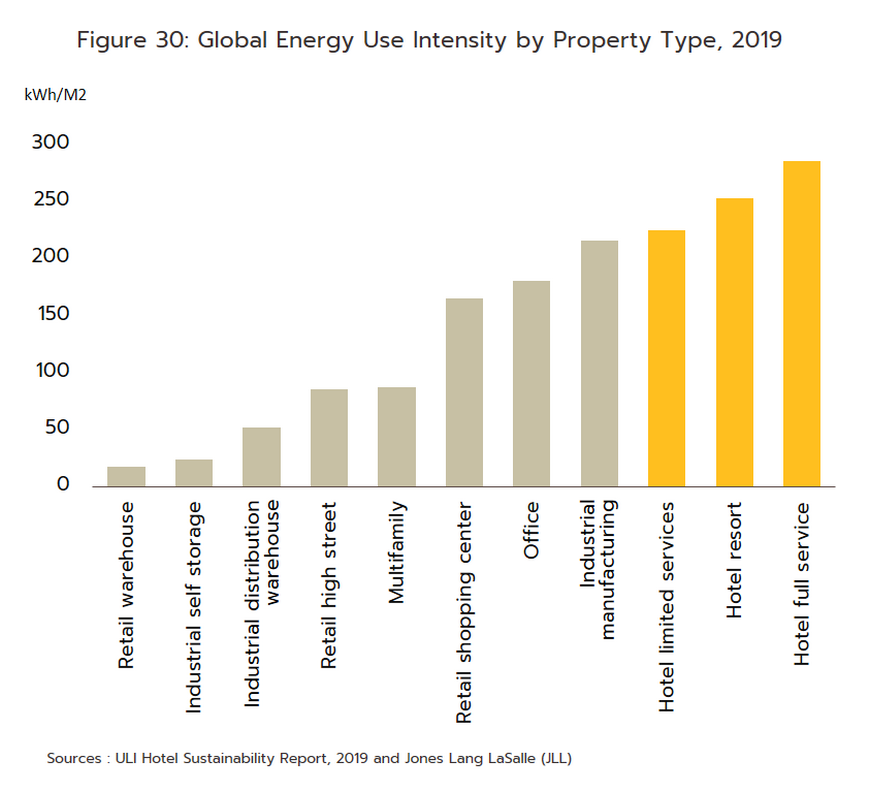

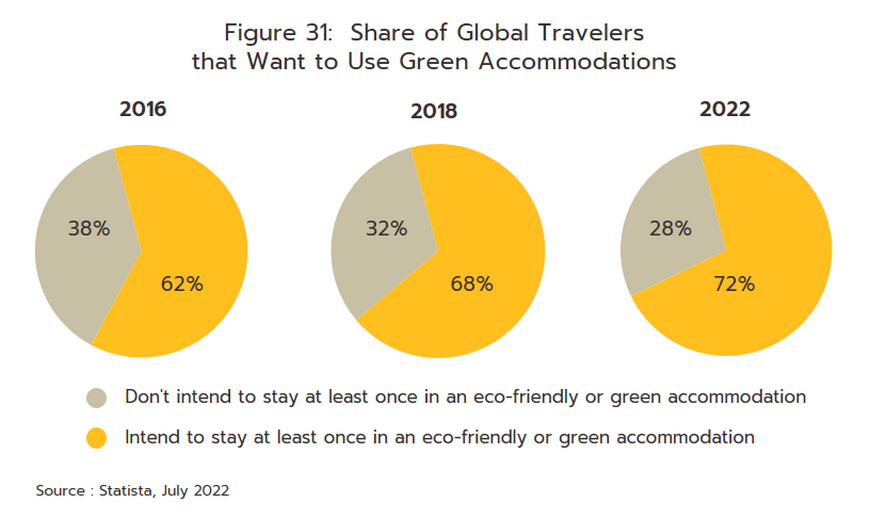

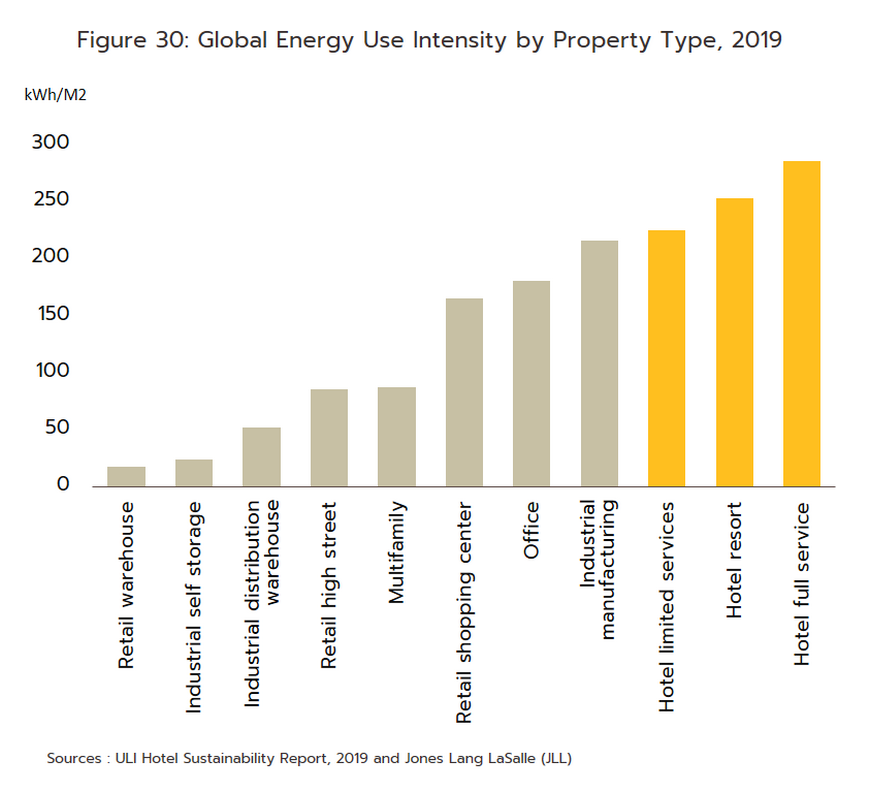

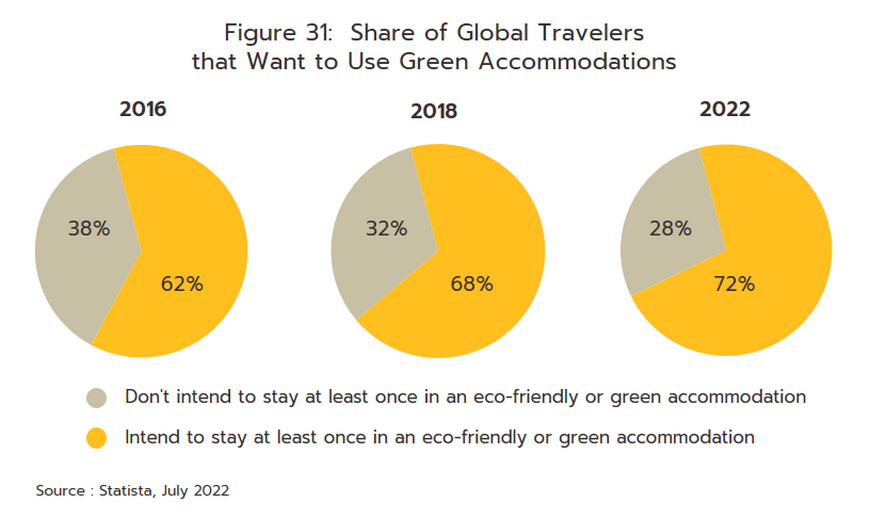

2) The development of ‘green hotels’ is being spurred on by greater consumer concern with environmental issues. This includes cutting back on energy use, ensuring that services and products offered in the hotel are all environmentally friendly, and reducing the amount of waste that is generated by the business. This is a difficult but important task; the ‘ULI Hotel Sustainability Report 2019’, which analyzed the energy intensity[6] of various types of building, showed that with an average energy consumption of 286 GWh/sq.m., full-service hotels (most of which are large scale operations) are the most energy hungry of all the buildings surveyed (Figure 30). Hotels thus have the largest carbon footprint of the latter. Many hotel operators are therefore now in the process of reducing their consumption of non-renewable resources, for example by asking guests not to request a daily change of sheets and towels (to reduce consumption of water and energy), fitting energy-saving LED lights, and installing UV-blocking film over windows, which then helps to reduce the load placed on air conditioners. Data from Statista shows that in 2022, 72% of travelers intended to stay at least once in an environmentally friendly hotel in the year, up from 62% in 2016 (Figure 31) and so these measures should help to meet rising consumer demand.

3) Operators will need to pay greater attention to matters relating to health and hygiene, and even as the COVID-19 pandemic fades, tourists will remain concerned about the possibility of contracting a disease and how hotels and tourist attractions address these worries. Many tourists will thus tend to avoid crowded indoor spaces. As outdoor activities become more popular, operators will increasingly work with nearby communities to develop the local area and to keep it safe, clean and free from the risk of infection. In the process, this will also strengthen their corporate brand and image.

[1] Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Phitsanulok, Kanchanaburi, Chonburi, Rayong, Chachoengsao, Nakhon Ratchasima, Khon Kaen, Udonthani, Ubon Ratchathani, Phetchaburi, Prachuap Kiri khan, Songkhla, Krabi, Phang-nga and Suratthani (Koh Samui).

[2] In November 1983, the Chinese government first allowed Chinese citizens to travel to Hong Kong and Macau in order to visit family members. The process of travel liberalization was accelerated by China’s entry to the WTO in 2001, and the requirement that China operate under WTO regulations regarding tourism. The result of this has then been to increase the number of Chinese tourists traveling abroad (Bank of Thailand, June 2014).

[3] The 11 most important tourist provinces are: Bangkok, Chonburi, Phuket, Suratthani, Chiang Mai, Krabi, Phang-nga, Songkhla, Phetchaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, and Rayong.

[4] Interviews with hoteliers and an evaluation of data by the Bank of Thailand indicates that an occupancy rate of 65-70% is considered satisfactory by operators.

[5] The research was carried out over January-October 2021, and was based on keyword searches by tourists in 62 countries.

[6] In this context, lower energy intensity indicates that energy is being used more efficiently.

.webp.aspx)