Krungsri Research projects conditions for the Thai sugar industry would improve in 2021-2023 along with the recovery of the overall economy, stronger demand from downstream industrial consumers, especially the food and beverage industry. There are also expectations of better climate, which would boost sugarcane output and sugar production. However, the industry is facing several challenges, including high sugar inventory worldwide and the effect on global sugar prices, imposition of sugar tax in many countries, rising awareness of personal health globally, and lingering uncertainty over government regulations for the industry, especially the reform of the Sugarcane & Sugar Act and its potential impact on operators’ margins and earnings.

Overview

Sugar is derived from plants and is used to increase sweetness[1]. There is strong global demand for sugar, both directly and indirectly. In the latter case, it is used as additive or flavoring in a wide range of products, including food, beverages, processed dairy products (milk, butter, yoghurt, etc.), candy, and baked goods.

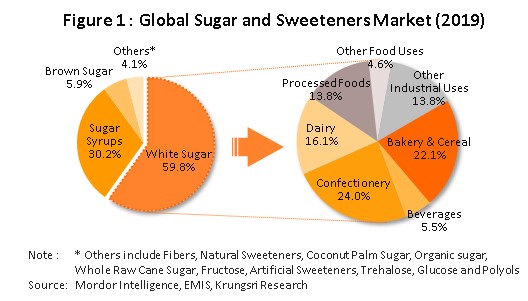

In 2019, sugar[2] accounted for 65.7% of all sweeteners consumed globally, with the remainder attributed to non-nutritive sweeteners. These include natural products such as honey, stevia and monkfruit (also called luohan guo), artificial sweeteners including aspartame cyclamate and erythritol, and dietary fibers (e.g., maltrodextrin fructo-oligosaccharides and inulin) (Figure 1).

Products derived from sugar processing can be split into the following.

- Raw sugar: This color can be anywhere from light to dark brown. It has moderate moisture and high molasses content, exhibits a tightly-packed crystalline structure, and tends to contain large quantities of impurities and residues. Raw sugar is further processed into white sugar, refined sugar, and other sugar-derived products including ethanol, alcohol and plastics. This refining process is what converts raw sugar into a consumable product.

- White sugar: This is obtained by removing impurities from raw sugar. White sugar has a crystalline structure and is white to pale yellow in color, has a low molasses and moisture content, and is loose and more friable than raw sugar. White sugar is favored for domestic household consumption and as raw material in the food and beverage (F&B) industry.

- Refined sugar: This goes through the same refining process as white sugar but the end product has less impurities and tends to be in the form of clear white granules. Refined sugar is very pure, with zero molasses content and very low or zero moisture content. Refined sugar is generally produced for household consumption and for industrial processes that require very pure sugars, such as making carbonated and energy drinks, and pharmaceuticals.

- By-products of sugar refining: By-products or value-added products include molasses[3], bagasse[4], filter cake[5], vinasses[6] and steam[7].

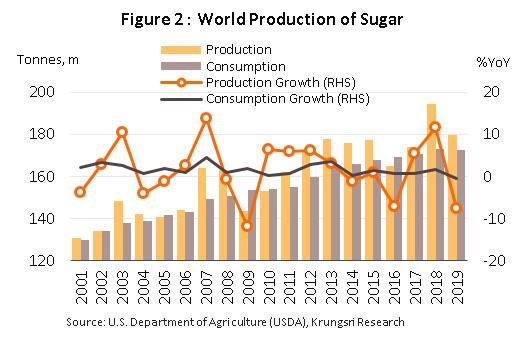

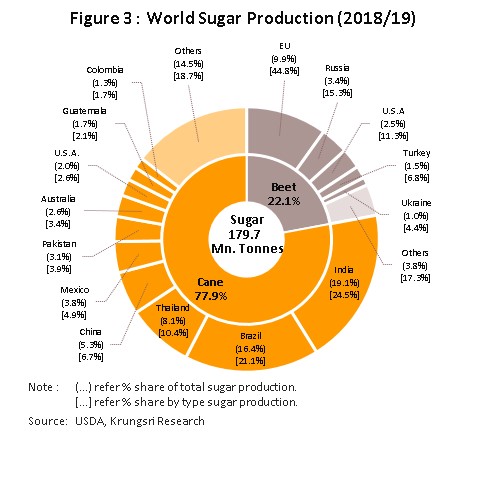

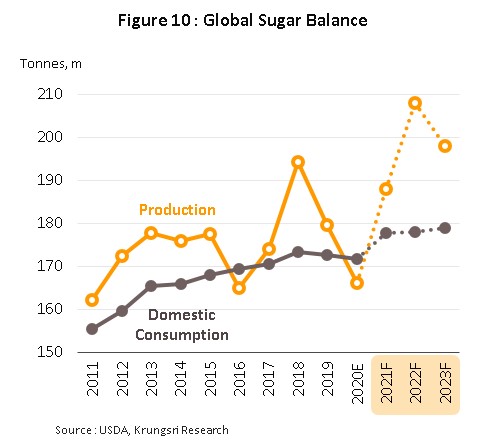

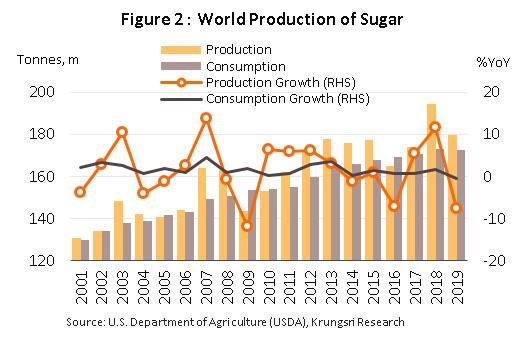

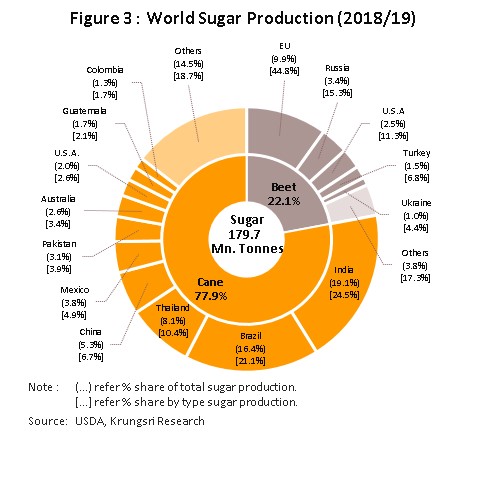

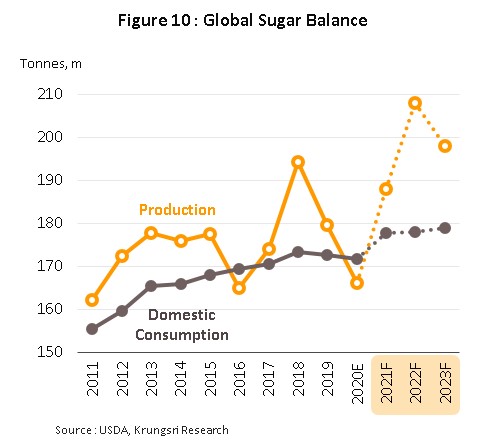

Between 2000 and 2019, global output and consumption of sugar had climbed steadily (Figure 2) thanks to: (i) growth of the world population, from 6.1 billion in 2000 to 7.7 billion in 2019; and (ii) rising demand for sugar from industrial consumers, especially food, beverage and ethanol producers. In 2019, global sugar production topped at 179.7 million tonnes (measured as raw sugar). The largest producers were India (19.1% of global output), Brazil (16.4%), the European Union (EU, 10.0%) and Thailand (8.1%) (Figure 2). Production can be categorized according to the type of input used. (i) 77.9% of global output comes from sugarcane, with most of this grown in countries near the equator, including Brazil and Asia-Pacific region (e.g., India and Thailand). India produces about a quarter of all sugarcane-derived sugar, followed by Brazil (21.1%), Thailand (10.4%), China (6.7%) and Mexico (4.9%). (ii) The remaining 22.1% of the world’s supply of sugar is derived from sugar beet, almost half of which originates from the EU, followed by Russia (15.3%), the United States (US, 11.3%), Turkey (6.8%) and Ukraine (4.4%) (Figure 3).

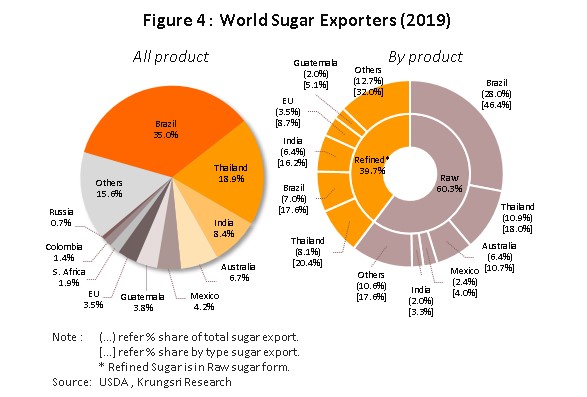

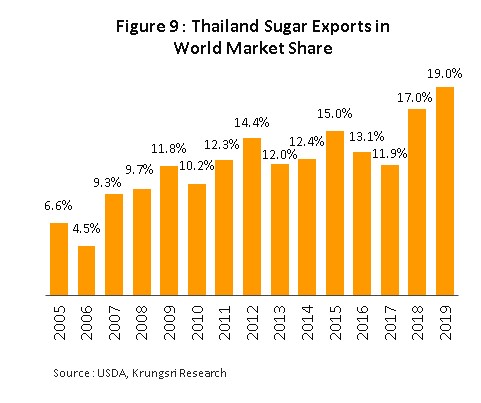

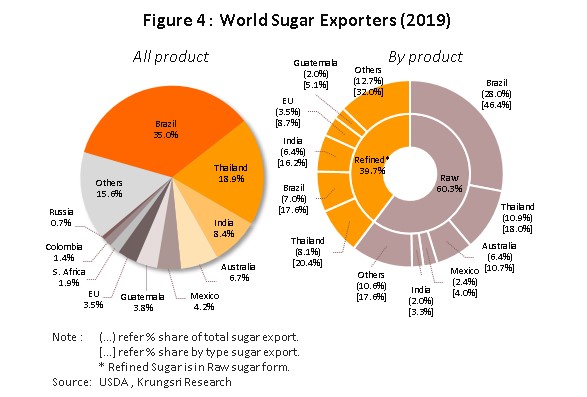

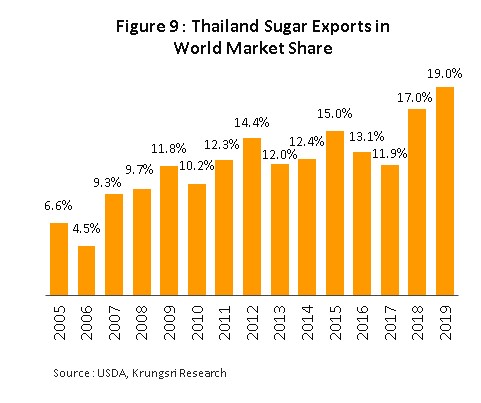

At last count, 56.0 million tonnes of sugar (measured as raw sugar) were traded annually on world markets, representing 31.2% of global production. The largest exporter is Brazil which controls over a third of the market, followed by Thailand (19.0%) and India (8.4%) (Figure 4). By product type, exports are split between: (i) raw sugar (60.3% of global exports); Brazil is the largest exporter (46.4% of raw sugar exports), followed by Thailand (18.0%) and Australia (10.7%); and (ii) refined sugar (39.7% of global exports); the major exporters are Thailand (20.4% of refined sugar exports), Brazil (17.6%), India (16.2%) and the EU (8.7%) (Figure 4).

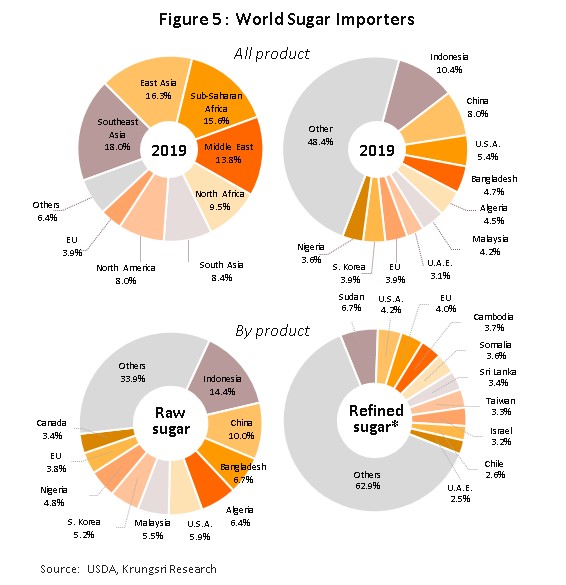

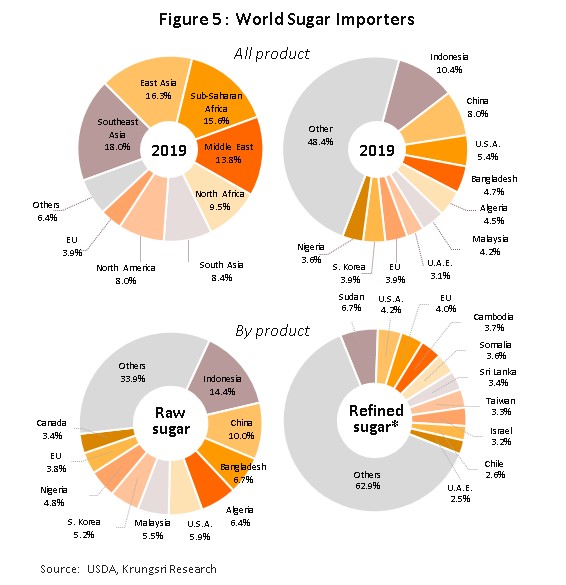

As regards imports (Figure 5), Indonesia is the world’s largest importer, buying 10.4% of all sugar traded on world markets. This is followed by China (8.0%), the US (5.4%), Bangladesh (4.7%) and Algeria (4.5%). By type, Indonesia is the world’s largest importer of raw sugar (14.4% of global sales of raw sugar), followed by China (10.0%) and Bangladesh (6.7%). For refined sugar, the biggest importers are Sudan (6.7% of global sales of refined sugar), the US (4.2%), the EU (4.0%) and Cambodia (3.7%).

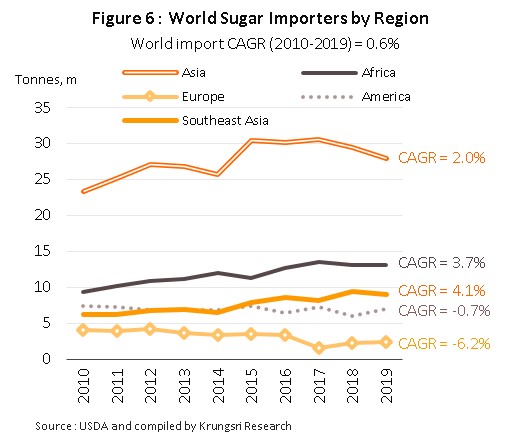

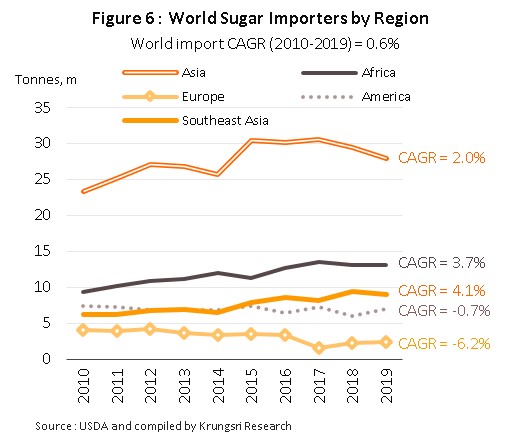

The Thai sugar industry is highly competitive on world markets, partly because of competitive production cost. At THB970-980/tonne, domestic sugarcane prices are low and second only to that in Brazil (THB890-900/tonne)[8]. Thailand also benefits from its geographical location in Asia, where demand for sugar is both high and rising. Sugar imports into Asia has been rising by an average of 2.0% per year, with imports into Southeast Asia climbing significantly faster at 4.1% per year, substantially higher than the world average of just 0.6% per year. This reduces transportation costs, putting Thai producers at a competitive advantage to other major sugar-producing countries such as Brazil and Australia (Figure 6).

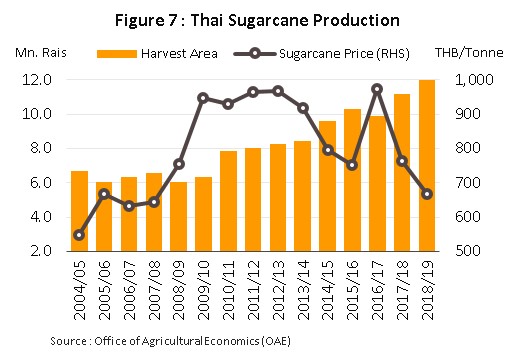

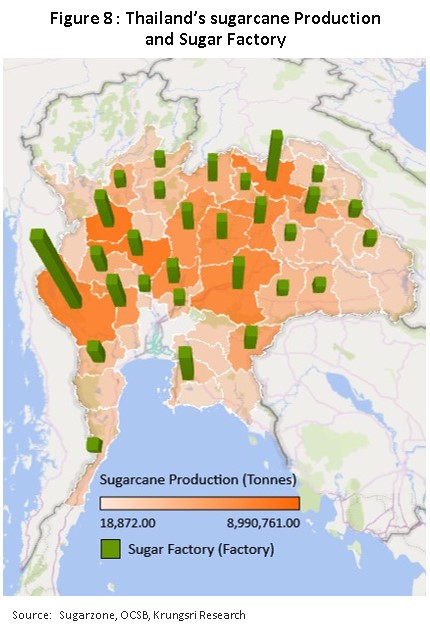

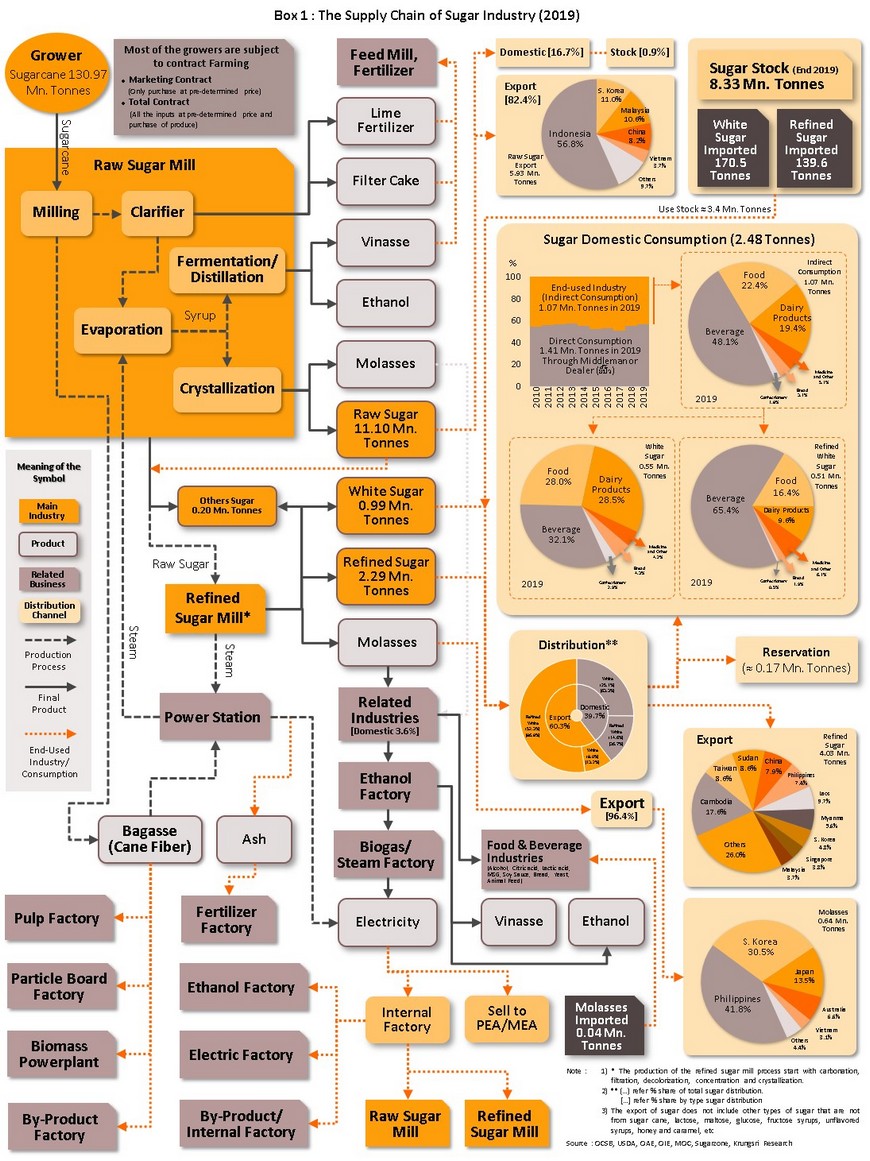

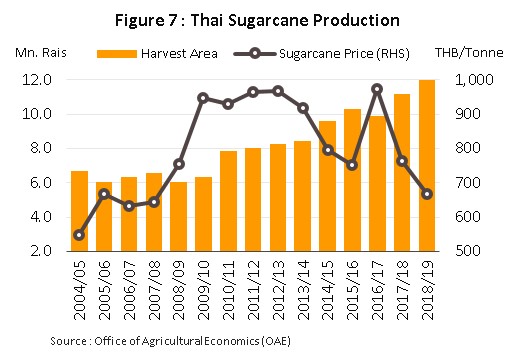

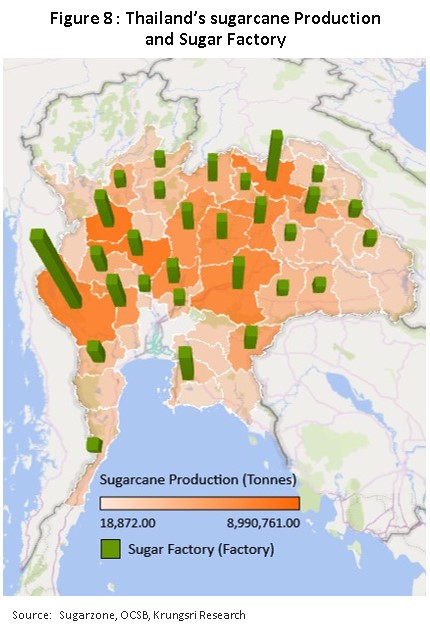

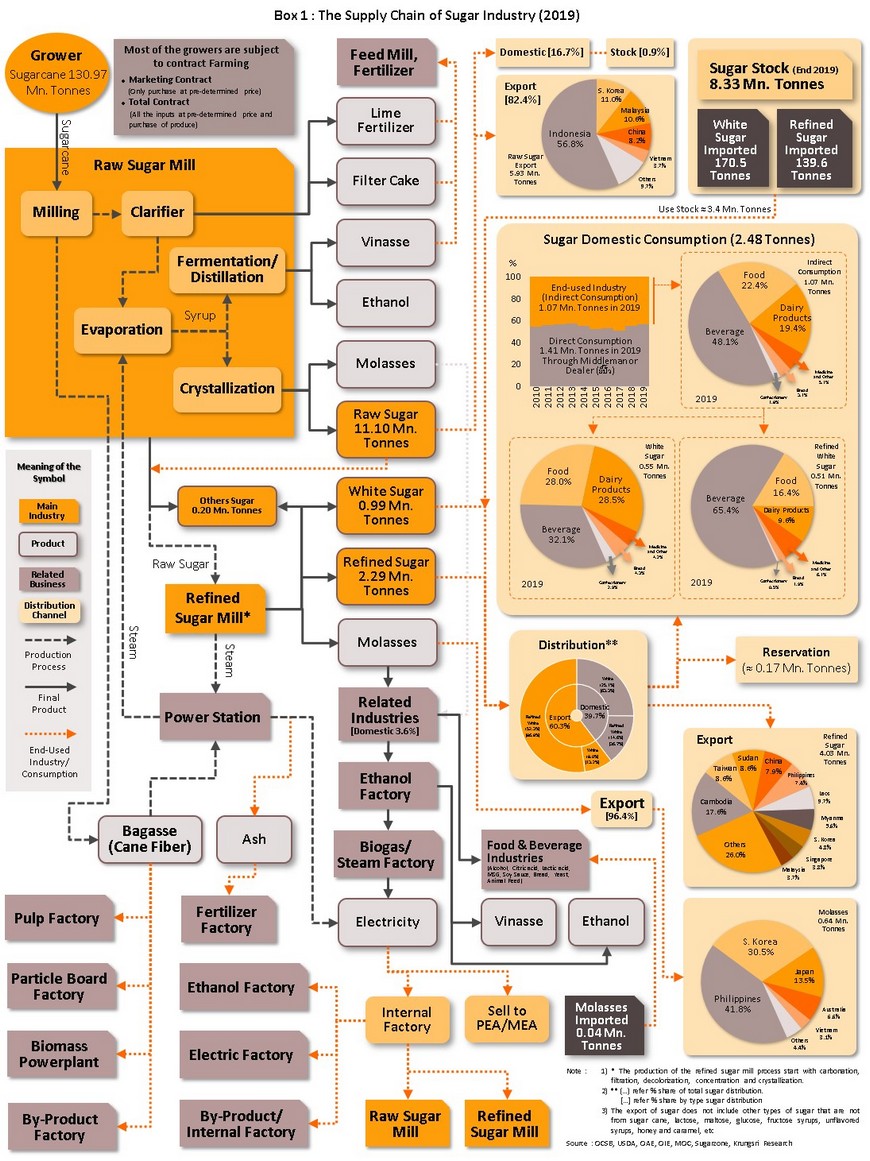

Sugarcane cultivation in Thailand has accelerated rapidly in recent years, with cultivated area almost doubling from 6.3 million rai in 2010 to 12 million rai in 2019 (Figure 7). This rapid expansion in supply was spurred by a combination of attractive prices and steadily rising domestic and international demand from both consumer and industrial end-users, in the latter case, the F&B industry and dairy processors (Box 1). Within Thailand, sugarcane cultivation is concentrated in the central, northeastern and western regions. The most important provinces are Nakhon Sawan (7.0% of Thai sugarcane farms), Kamphaeng Phet (6.9%), Kanchanaburi (6.4%) and Udon Thani (6.3%) (Figure 8).

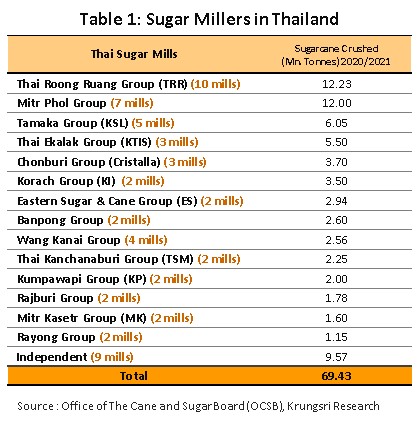

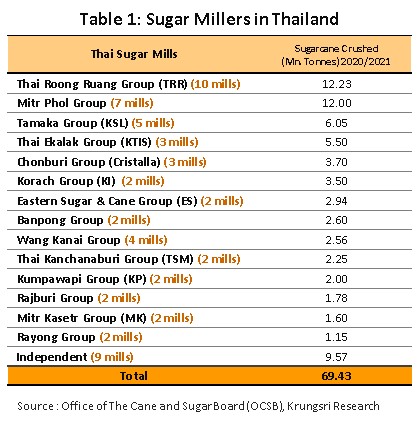

At present, there are 57 sugar mills in Thailand[9] (Table 1). The majority is located close to sugarcane growing areas for the following reasons: (i) easier to source input according to production plans; (ii) reduces transportation costs; and (iii) easier to communicate with sugarcane growers or to offer assistance. In addition, logistics consideration often have an influence on mill locations, so they are also often close to urban areas, ports and major trade centers. Hence, the greatest concentration of sugar mills is in Kanchanaburi which is home to 8 mills, followed by Udon Thani and Chonburi with 4 each.

The Thai sugar industry exports 81% of total sugar sales volume. This means Thailand accounts for 19.0% share of the global sugar market (Figure 9). Exports are split between: (i) raw sugar – Thailand is second with 18.0% share of world exports, after Brazil 46.4%; (ii) white sugar – Thailand lead with 20.4% market share (Figure 4); and (iii) molasses – Thailand is third largest with 8.8% market share. Thailand’s main export markets are Indonesia (buys 32.9% of Thai sugar exports), followed by South Korea (9.8%), China (7.6%), Malaysia (7.4%) and Cambodia (6.7%). The situation for exports of these different product groups in 2019 is outlined below.

- Raw sugar: Exports of raw sugar comprised 56.0% of all sugar exports, or 5.9 million tonnes. The main markets for this were Indonesia (56.8% of Thai exports of raw sugar), South Korea (11.0%), Malaysia (10.6%) and China (8.2%).

- White sugar: 4.0 million tonnes of white sugar were exported (38.0% of sugar exports). The biggest markets were Cambodia (17.6% of Thai exports of white sugar), Taiwan (8.6%) and Sudan (8.6%).

- Molasses: Exports amounted to 6.0% of Thai sugar exports, or 0.6 million tonnes. This was principally imported by three countries – the Philippines (41.8% of Thai molasses exports), South Korea (30.5%) and Japan (13.5%).

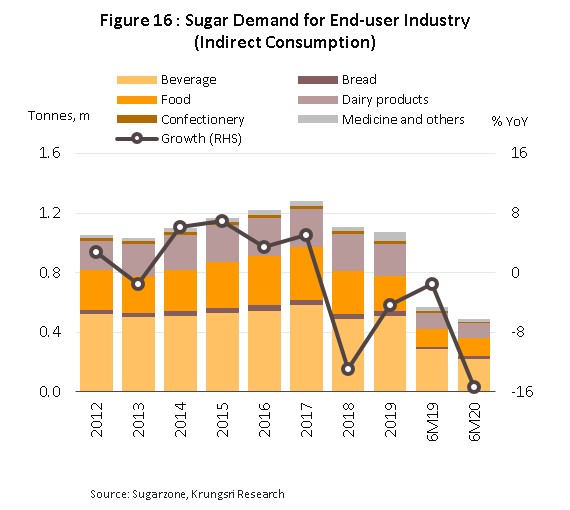

Domestic consumption of sugar reached 2.5 million tonnes in 2019, or 19% of Thailand’s total sugar sales volume[10]. This comprised 56.9% sold to the end-consumer (households) and 43.1% sold to industrial buyers (indirect consumption) for use in beverage production (48.1% of total indirect consumption), food processing (22.4%) and processed milk products (19.4%).

Companies can generate revenues not only from the sale and distribution of sugar, but also from the commercial exploitation of by-products created by the sugar refining process. These include molasses, which is now used to produce ethanol. And with the government promoting ethanol use (mainly by increasing ethanol content in gasohol)[11] demand for this is growing. Many sugar mills have also invested in downstream businesses that use by-products as inputs, including biomass energy production[12] and the manufacture and production of paper pulp, particle board and fertilizer (Box 1).

Situation

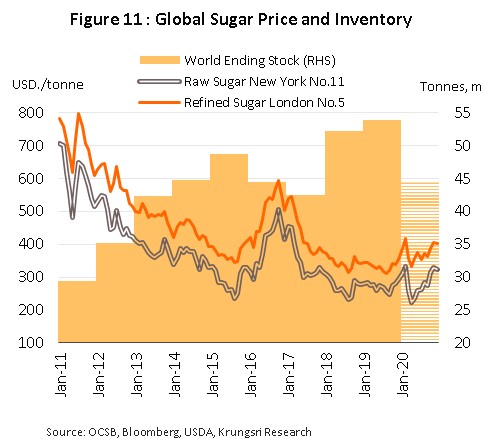

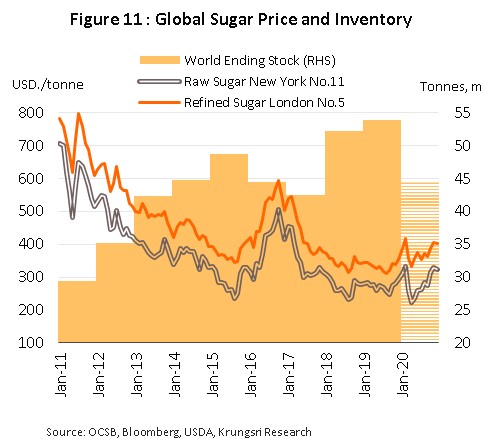

In October 2016, the average price for sugar on global exchanges rose to a 5-year high of USD505.3/tonne. For the year, average prices jumped 38.1% from 2015 level. This was driven by a combination of drought in Asia and excessive rains in Brazil. They reduced sugarcane output, and global sugar supply by 7.1% (to 165.0 million tonnes). Simultaneously, demand rose by 0.7% to 169.3 million tonnes.

However, in 2017, prices tumbled following a steep rise in sugar inventories driven by: (i) dissipating drought conditions in Asia which boosted sugarcane output, and consequently, global sugar output; (ii) weaker crude oil prices which reduced incentive to manufacture ethanol, prompting some Brazilian producers to switch to sugar production; (iii) the move by China to hike in import tariffs on excess-quota from 50% to 95% to address high domestic inventories; and (iv) the 5-6 million tonnes/year increase in sugar exports from India. These factors led to global sugar inventory surging from 44.5 million tonnes in 2016 to 54.0 million tonnes in 2019. And over the same period, world sugar prices slipped from USD400.0/tonne to an average of USD272.3/tonne.

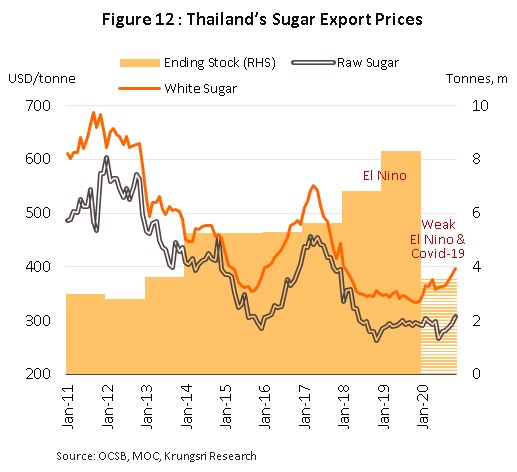

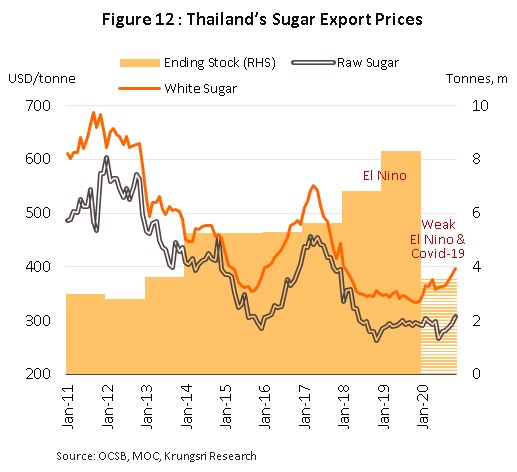

In 2018, Thailand removed sugar export quotas and stopped controlling domestic sugar price. This altered the sugar and sugarcane industry supply chain substantially. The Thai sugar reference price is now linked to prices on global markets (London Sugar No. 5 price) plus domestic raw and refined sugar cash premiums. Thus, export prices of Thai raw sugar fell to USD307.2/tonne (-28.1%) in 2018 and USD292.9/tonne (-4.7%) in 2019 (Figure 12). Domestic sugarcane prices fell along with global sugar prices, dropping to THB763.4/tonne (-21.5%) and THB668.2/tonne (-12.5%) in those years.

In 2020, global sugar production fell by 7.5% due to a combination of severe drought in major sugar producing areas in Brazil, India and Thailand, and the COVID-19 pandemic which temporarily halted most economic and industrial activities and created uncertainty about global quantity of sugar exports. Against this background, world prices for raw sugar reached a 4-year high of USD332.2/tonne in February. For the year, prices for raw and white sugar averaged USD284.1 and USD375.7 per tonne, respectively (+4.3% and +12.8% from 2019 prices).

The situation for the Thai sugar industry in 2020:

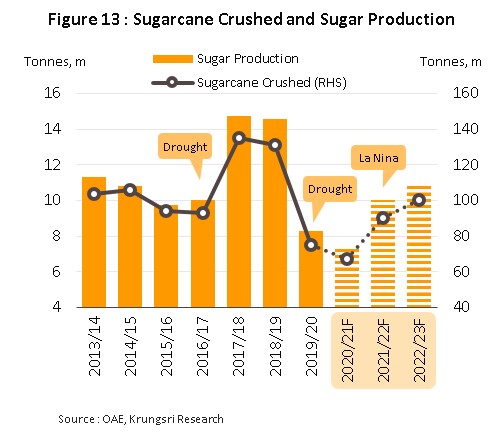

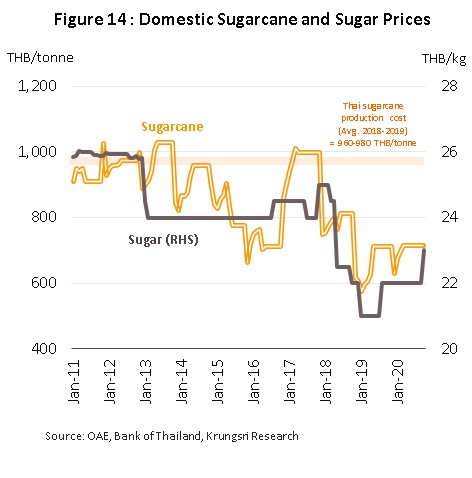

- Sugarcane and sugar output crashed to 10-year lows of 74.9 million (-41.7%) and 8.3 million tonnes (-43.1%), respectively (Figure 13), as a result of severe drought and smaller sugarcane cultivation area. The latter was caused by low sugarcane prices, which prompted growers to switch to more profitable crops. This pushed up domestic sugarcane prices, by 7.3% to THB716.8/tonne. But despite this, market prices remained below production cost of THB960-980/tonne (Figure 14). Average white sugar retail price also climbed in the year, but at a slower rate of 3.8% to THB22.1/kilogram.

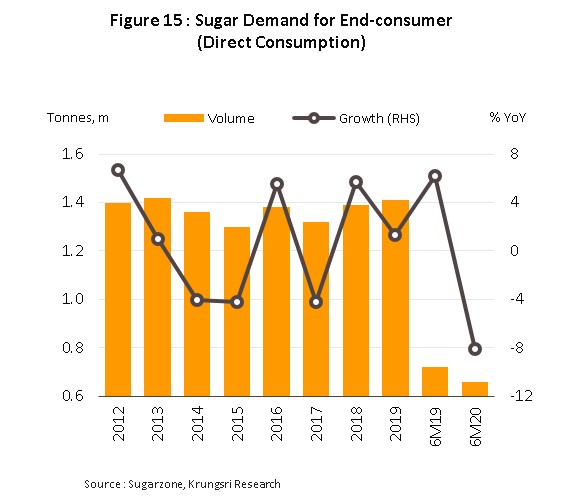

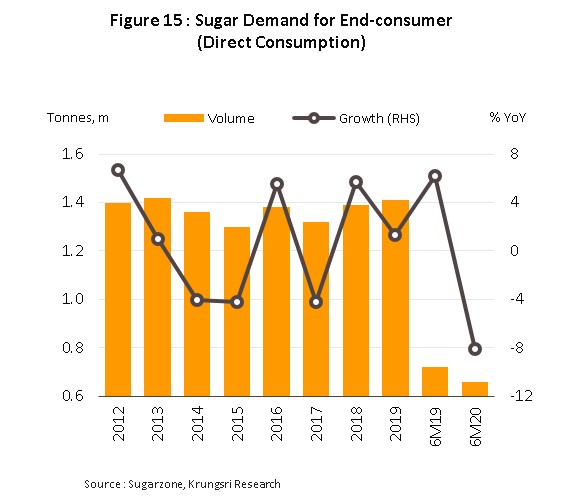

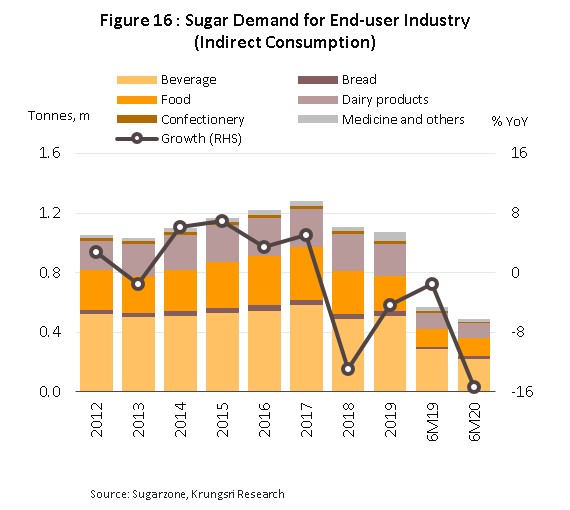

Demand for sugar contracted by 3.2% to 2.4 million tonnes, following a fall of 3.9% in 2019. In the first half of 2020, demand plunged 11.3% YoY to 1.1 million tonnes, because the COVID-19 pandemic had weakened consumer spending power and halted most industrial activity, including downstream food and beverage production and dairy processing industries (Figures 15 and 16). But in the latter half of the year, the government had relaxed lockdown measures and reopened the economy, and demand for sugar started to rise again.

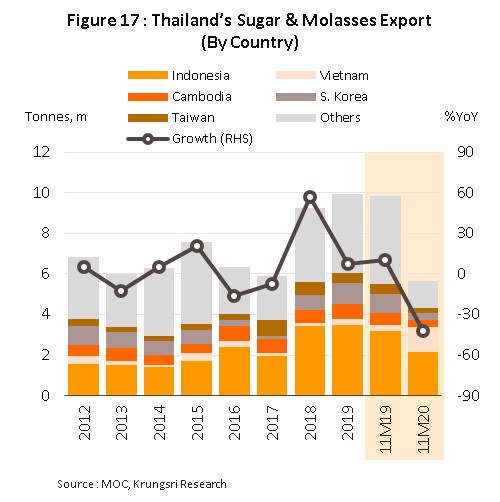

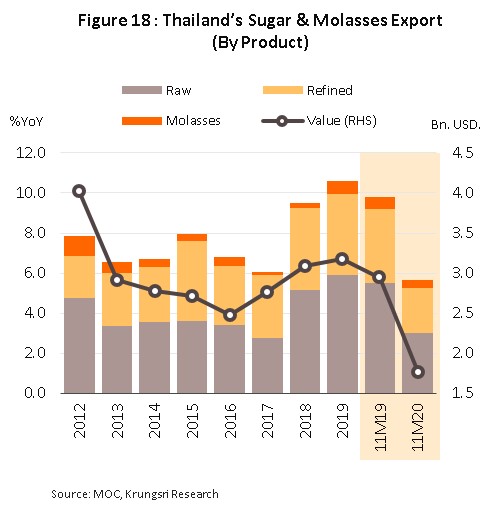

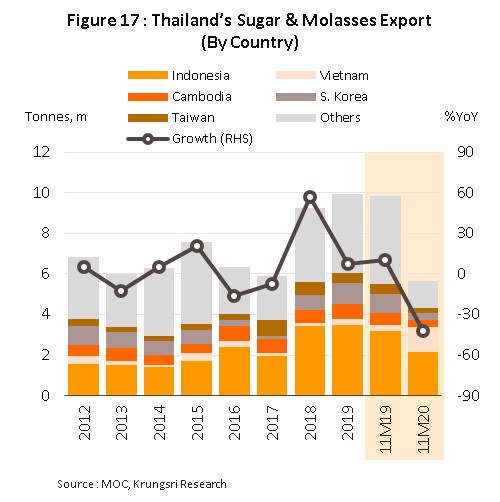

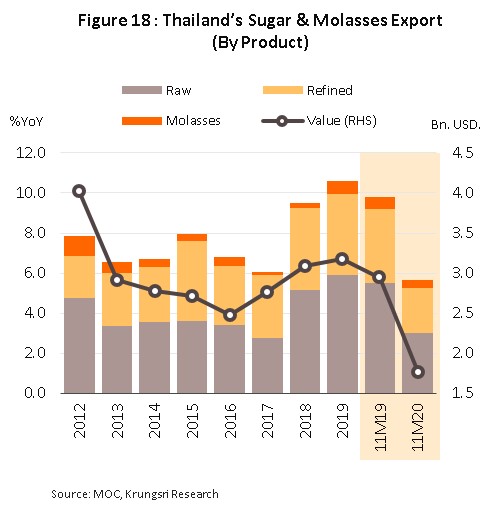

- Exports also fell. For the first 11 months of 2020, exports of sugar and molasses dropped to a 4-year low of 5.6 million tonnes (-42.4% YoY) and generated receipts of USD1.8bn (-40.0% YoY). The drought-driven crash in output and the sharp contraction of the global economy in 2020, which the IMF estimates at -3.5%, reduced exports to most of Thailand’s main markets. They include Indonesia (-33.0%), Cambodia (-39.3% YoY) and South Korea (-64.5%); only Vietnam bucked the trend (+320.6%)[13]. Against this, export prices rose slightly by 4.2% YoY. Details of exports for the different product categories are given below (Figures 17 and 18).

- Raw sugar: Exports reached 3.0 million tonnes (-45.2% YoY), generating USD0.9bn (-45.3% YoY). Shipments to most markets contracted, including to Indonesia (-32.6% YoY), Japan (-47.0%), South Korea (-71.8%), and Taiwan (-41.4%). Only Vietnam stayed in the black (+131.8%). Export prices for raw sugar also dipped 0.7% to USD290.9/tonne.

(-47.0%) และไต้หวัน (-41.4%) ยกเว้นเวียดนาม (+131.8%) ด้านราคาส่งออกน้ำตาลทรายดิบอยู่ที่ตันละ 290.9 ดอลลาร์สหรัฐ (-0.7% YoY)

- White sugar: Exports fell 39.5% YoY to 2.2 million tonnes, but export value fell at a slower rate of 35.1% YoY (or USD0.8bn). Again, exports fell to most markets; only Vietnam (31.9% of all exports of white sugar) bucked the trend and it did so spectacularly, with exports exploding 1,257%. Export prices improved 7.1% YoY to USD368.5/tonne.

- Molasses: This segment did little better than others. Though exports fell by 35.4% YoY to 0.4 million tonnes, receipts held up fairly well, dropping by only 2.3% to USD59.3 million. Exports fell across the main markets – the Philippines (-42.0% YoY) and South Korea (-53.0%), which together account for more than 60% of all molasses exports by volume. However, export prices did well in the year, jumping 53.3% YoY to USD180.3/tonne.

Outlook

Over the next 3 years (2021-2023), conditions will improve for the Thai sugar industry with the recovery in the domestic and global economies.

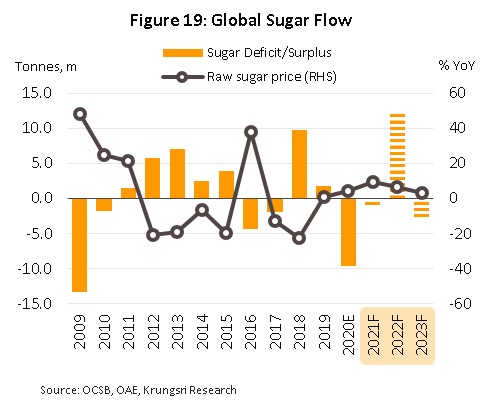

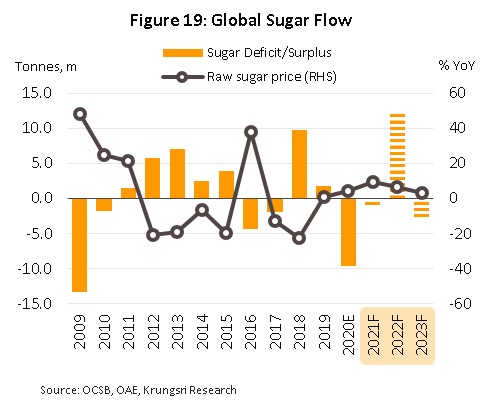

- In 2021, global sugar production is forecast to expand by 13.2% to 188 million tonnes (source: USDA). Krungsri Research predicts this will rise by another 10% annually (CAGR) in 2022 and 2023. This would be partly driven by Brazilian production which is expected to jump 32% in 2021 to a new-high of 39.3 million tonnes and would continue to rise over the next 2 years. Prices for raw sugar on world markets are also expected to rise to an average of USD310-340/tonne (or 14.0-15.5 cents/pound) from 2020 average of USD284.1/tonne (or 12.9 cents/pound) (Figure 19).

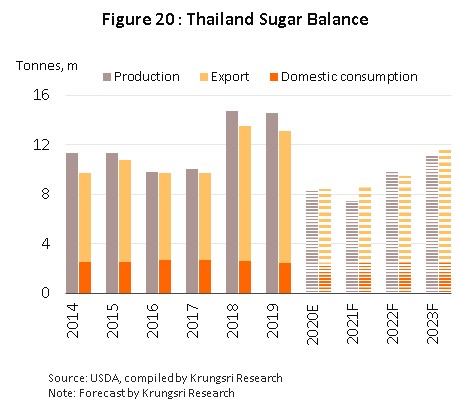

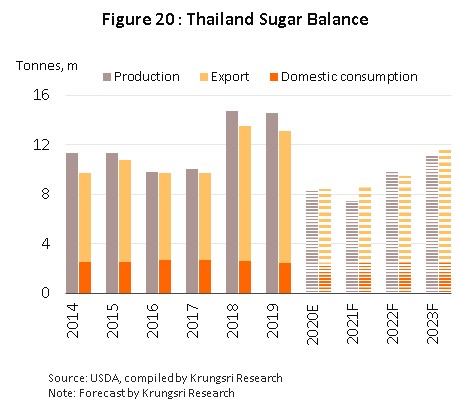

- However, domestic sugar production is expected to contract by 10.2% to 7.4 million tonnes in 2021. This would be attributable to the lingering impact of the severe drought in 2020 (the worst in 40 years), which prompted farmers to reduce sugarcane cultivation area and caused cane stumps to die-out (sugarcane that is harvested and then left in the ground to regrow). The situation should turn around in 2022 and 2023. Sugar production is forecast to rise to 9-10 million tonnes per year, or by an average of 10.0% per annum (Figure 20), as emerging La Niña[14] conditions in 2020 would likely lead to higher rainfall and greater availability of water for irrigation. Prices are also projected to rise by an average of 4.0-7.0% annually and lift sugarcane prices to THB800-875/tonne, following a 7.3% increase in 2020.

- Domestic demand for sugar will rise by an average of 2.0-3.0% per year to 2.5-2.6 million tonnes (Figure 20). Consumption will be supported by the return to growth of the Thai economy, and greater demand from industrial users, especially the F&B industry. At the same time, lingering COVID-19 fears will sustain demand for disinfecting alcohol (made from sugar), while demand for ethanol will rise with greater activity in the transport sector given the recovering broad economy and government rules on ethanol content in gasohol[15].

- Sugar exports is expected to increase to 7-8 million tonnes annually, up 10.0-15.0% per year (Figure 20). This is premised on the recovering world economy, rising domestic sugar production, and progress in new free-trade agreements (FTAs)[16]. However, Thai exporters will face greater competition from producers in Brazil, who are switching from ethanol to sugar production to meet rising demand from the F&B industry, and in India, who like Thai producers, produce more sugarcane with better climate and access to irrigation water.

- Challenges facing the domestic sugar industry in the coming period include the following:

- Global stocks of sugar are already high, and there is a risk that these will expand further, putting greater downward pressure on sugar prices.

- 2)Growth in demand for sugar would be capped due to:

–The imposition of sugar tax in many countries (including Thailand) on sweetened drinks[17]; this has been reducing the beverage industry’s demand for sugar.

Generally rising concerns about personal health in many countries.

- Lingering uncertainty over changes to government regulation for the industry. This is partly due to proposed revisions to the Sugarcane and Sugar Act, and amendments to the definition of ‘sugarcane’ and ‘sugar’ which might be extended to include sugarcane extract, and of ‘byproducts’ which might include bagasse, filter cake and ethanol. This would affect how sugar mills calculate their share of revenue and profits. Currently, mills retain all the profits from the processing and sale of byproducts, but the proposed new regulations would force them to allocate a portion of the profits to farmers.

Rules and regulations affecting the Thai sugarcane and sugar industries

- In April 2016, Brazil brought a case against Thailand under the WTO platform, alleging the Thai government used the Sugarcane and Sugar Act to interfere in the global sugar export market. Brazil alleged the Thai government: (i) maintained domestic sugar prices at rates above prevailing world market rates, and that this allowed Thai producers to subsidize their exports which they sold at below-market prices; and (ii) supported sugarcane farmers and sugar mills through payments to sugarcane growers, providing subsidies to farmers through the Cane and Sugar Fund, underwriting soft loans for farmers, and other subsidies for a variety of factors of production that were in excess of those allowed under WTO rules, as well as unfairly supporting ethanol production (largely made from molasses).

- In an attempt to reduce pressure from the Brazil case, the government announced that starting from 2017/18 harvest season, it would float domestic sugar prices (effective 15 January 2018). This would be part of a move to implement systematic, industry-wide reform in the sugarcane cultivation and sugar production industry. However, this had implications on how the domestic sugar price is calculated, as described below.

1) The domestic price of sugar is now linked to global prices, from being set by the authorities[18]. It now moves in line with world prices. The reference price in the domestic market is now London price for No. 5 white sugar plus Thai price premium for sugar[19] which is calculated in Thai baht. This determines the minimum price of sugar (on monthly basis) in Thailand, though the changes might have unwelcome effects those selling mostly to the domestic market because revenues would be volatile.

2 ) All three parts of the quota system have been abolished. ‘Quota A’ which determined sales to the domestic market, ‘quota B’ which determined exports by the Thai Cane and Sugar Corporation[20], and ‘quota C’ which determined exports by individual companies. Under the new system, to protect against the possibility of domestic sugar shortage, sugar manufacturers now need to maintain a buffer security reserve of 250,000 tonnes/month. However, repealing the quota system has not had serious consequences on players because the quantity of sugar which they are required to reserve is similar to the requirements imposed under the old system. The effects of removing ‘quota B’ and ‘quota C’ (which determined exports) has had different impact on operators’ revenues, depending on their individual ability to anticipate movements in world prices.

3) The THB5/kilogram collection from factory-gate sugar prices for the Cane and Sugar Fund[21] has been replaced with contribution to the fund under a new formula. This is calculated based on the difference between factory-gate prices (determined by a survey of the market) and the minimum price. However, this new formula has led to greater uncertainties over what level of contributions will be required of mills since the exact charges will depend on the state of domestic and international markets. And when factory-gate prices are lower than the minimum price, they do not need to contribute.

- At present, the House of Representatives are considering amendments to the Sugarcane and Sugar Act with the intention that: (i) its provisions should be brought in line with the requirements for membership in the WTO; and (ii) solutions should be found to the problem of low prices for sugarcane and sugar. The most important proposed changes are as follows:

1) The Sugarcane Growers Association has proposed that the definition of ‘sugar’ under the existing legislation be changed, which would affect how revenue is calculated within the industry. If the definitions of ‘sugarcane’ and ‘sugar’ are extended to include ‘sugarcane extract’ and that for ‘byproducts’ is expanded to encompass bagasse, filter cake and ethanol, these products would be included in calculating the 70:30 split in revenue between sugarcane growers and sugar mills[22]. This would reduce revenue for mills because they would no longer be able to claim exclusive right to revenues derived from the processing and distribution of byproducts arising from the milling of sugarcane.

2) The Cane and Sugar Fund may be removed from the process of making compensation payments when there is a difference between preliminary and final sugarcane prices. This will be especially important when the preliminary price is higher than the final price[23] (that is, when the mill has effectively overpaid in advance for sugarcane). It is expected that the amendments to the Sugarcane and Sugar Act will specify that sugar mills be responsible for collecting overpayments from sugarcane growers, by setting this overpayment against purchases in the next harvest season. This contrasts with the earlier system where the Cane and Sugar Fund acted as an intermediary[24].

- Proposed new measures to alleviate problems associated with burning sugarcane. From 2020 to 2022, new policies have been implemented to encourage sugar mills to cut purchases and pressing of burnt sugarcane. In the 2019-2020 crop season, these should not exceed 50% of purchases, and would drop to no more than 20% in 2020-2021 season and just 0-5% in 2021-2022 season. The government has also adjusted conditions for growers to receive subsidies. In 2019-2020, payments to sugarcane growers were split into the two portions (i) assistance with production/cultivation costs, and (ii) additional payments to those harvesting fresh sugarcane. From the 2020-2021 crop season onwards, only the second payment will be available. This payment is set at THB130/tonne, yielding a total cost of THB7.28 billion (based on forecast 70 million tonnes of sugarcane being crushed in 2020-2021, of which 80% (56 million tonnes) will be harvested fresh).

Krungsri Research’s view

Business conditions will improve for the Thai sugar industry through to 2023. This would be driven by an expansion in the total quantity of products distributed across all markets, but the extensive dependence on exports will expose players to a degree of uncertainty.

- Sugar mills: Revenue will grow in the coming period along with rising consumption, supported by: (i) a recovery in economic growth, which will improve purchasing power at home and abroad; (ii) recovery of downstream industries (especially F&B) as the COVID-19 impact wanes; (iii) linger fears of infection would sustain demand for disinfectant alcohol; and (iv) a rebound in economic activity would create an uptick in the transport sector, and with this, demand for ethanol would rise. The industry would also benefit from strong and secure supply chains (thanks to the revenue-sharing scheme), the development of a wide range of products, and ongoing investment in high-value downstream industries that largely involve the commercial exploitation of waste and byproducts arising from the sugar milling process.

- Sugar traders: Traders selling to overseas markets are expected to benefit from rising exports, but they may also face greater risks from misjudging price movements affected by uncertainty over global supply. Traders on the domestic market will face more volatile market conditions since the government has floated domestic prices; this means they will have to absorb larger stock management costs.

- Sugarcane growers: Improved weather conditions should increase output and boost sugar content of domestic sugarcane. But because Thai prices are now moving along with world markets, growers are exposed to greater risk of losses, and the resulting drop in revenue would affect future planting decisions. However, it is hoped that the government and/or sugar mills will introduce measures to support income for sugarcane growers to maintain a steady supply of input.

[1] Sugars are found in most plant tissues but sugarcane and beet have sufficiently high concentrations that they can be commercially cultivated for sugar.

[2] Considering only white and brown sugar.

[3] Obtained from the process of simmering sugar. Molasses is a viscous, dark brown liquid used as an input into ethanol production (which is then mixed into gasohol) or in the food and drinks industry to make products including alcohol, yeast, monosodium glutamate, pet food, vinegar and a range of different sauces.

[4] Obtained by crushing sugarcane. It is one of the main products used in biomass energy production. Bagasse is also used to produce packaging and different construction materials including fiber board, particle board, melamine faced chipboard, medium-density fiberboard (MDF), synchronized MDF, lacquer high gloss MDF, and pure cellulose.

[5] Filter cake is produced from the filtering of liquid sugarcane extracts. It contains nutrients and minerals that can be used to make fertilizer, animal feed and biogas.

[6] Used to make organic fertilizer and animal feed.

[7] Used to drive machinery and to generate electricity for use within the sugar mill.

[8] Source: The Brazilian sugar and ethanol industry

[9] The Royal Thai Government Gazette on 17 August 2015 announced that sugar mills are required to be sited at least 50 kilometers away from one another, compared to 80 kilometers in the previous announcement.

[10] Does not include imports of raw sugar that are used to make white sugar or stocks of raw sugar in the country.

[11] In 2019, installed production capacity for the manufacture of ethanol from crushed sugarcane and molasses came to 3.01 million liters per day (this does not include another 0.93 million liters per day of capacity in facilities that use both cassava chip and molasses). This then generated annual demand for molasses of over 4.6 million tonnes (+14.1%) and for 1.1 million tonnes of crushed sugarcane (+10.2%).

[12] Energy produced from bagasse-powered biomass facilities is generally consumed within the sugar mill itself, with any surplus sold on to nearby consumers.

[13] Following the implementation of the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) on 1 January 2020, Vietnam cut its quotas on imports of Thai sugar and slashed duties to just 5% from the earlier level of 30-40%.

[14] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates that for January-April 2021, there is a greater than 50% chance that La Niña conditions will emerge, resulting in greater than normal rainfall and that for May-August 2021, rainfall should be close to average for the period (source: Weekly ENSO Evolution, Status, and Prediction Presentation, NOAA, 11 January 2021).

[15] Krungsri Research predicts that the promotion of E20 in place of 91-octane E10 (10% ethanol) will lead to a rise in consumption that will take it from 20% of all gasohol sales in 2020 to 30% over 2021-2023.

[16] The Department of Trade Negotiations hopes to move forward with discussions over the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and FTAs between Thailand and Turkey, Thailand-Pakistan, Thailand-Sri Lanka, the United Kingdom and the European Union, among whom are major global sugar importers.

[17] At present (between 1 October 2019 and 30 September 2021) the sugar tax is set at six rates: (i) A sweetness level of 0-6 grams per 100 milliliters is tax exempt; (ii) a sweetness level of 6-8 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 0.1/liter; (iii) a sweetness level of 8-10 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 0.3/liter; (iv) a sweetness level of 10-14 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 1/liter; (v) a sweetness level of 14-18 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 3/liter; and (vi) a sweetness level of 18 grams per 100 milliliters and over incurs a duty of THB 5/liter. The rates of tax within these bands will be steadily stepped up, and 2 more rounds of increases are scheduled, the first running from 1 October 2021 to 30 September 2023 and the second from 1 October 2023 onwards. This tax has had the effect of prompting manufacturers to cut the quantity of sugar in their drinks but its impacts on domestic sugar production have been limited by the fact that the tax rates are relatively light and only some 4-6% of the output of the domestic sugar industry is consumed by Thai drinks manufacturers.

[18] Previously, officials controlled the sugar price by stipulating that factory-gate prices for white sugar and of refined sugar were fixed at THB 20.3/kilogram and THB 21.4/kilogram, respectively (set by an announcement by the Ministry of Commerce in 2012). Producers also had to make THB 5/kilogram contributions to the Cane and Sugar Fund, meaning that their income ran to THB 15.0-16.5/kilogram, or USD450-515/tonne. This was higher than the world price for white sugar, which over the three years earlier had averaged USD435/tonne, and this thus helped to maintain artificially high levels of income and profits for Thai sugar producers.

[19] This is an addition made for selling Thai sugar for export, although the premium fee may be either positive or negative, depending on (i) the market price of sugar on the day of export, (ii) demand from buyers, and (iii) the sugar’s quality.

[20] The Thai Cane and Sugar Corporation is a joint venture between sugarcane growers, sugar mills, and Thai government agencies. The nine sugar exporters are: The Thai Sugar Trading (TSTC), Pacific Sugar Corporation (PSC), Siam Sugar Export (SSEC), Sugar Industry Trading (SITCO), T.I.S.S. Company, K.S.L. Export Trading (KSL), Thai Cane and Sugar (TCSC), World Sugar Export Corporation and Ruamkamlarp Export Company.

[21] The Cane and Sugar Fund (CSF) was established to research, develop, and promote the production, use, and distribution of sugarcane and sugar. The CSF is also responsible for maintaining the stability of the industry and of prices for domestically consumed sugar.

[22] A revenue-sharing system (the ‘70:30 system’) has been established by law to split revenue between sugarcane growers and sugar millers. The system divides net profits from distribution to domestic and export markets for each growing season between farmers, who receive 70% of net profits as ‘compensation for the sugarcane price’, and processors, who receive 30% as ‘compensation for production’. At present, these proportions are set according to definitions contained in the 1984 Sugarcane and Sugar Act.

[23] The preliminary price of sugarcane, estimated by the Office of the Cane and Sugar Board and announced in December at the start of the growing season, is the initial compensation that sugarcane growers receive from mills, who pay this money in advance at the beginning of the growing season. The preliminary price should be no less than 80% of estimated income, which is calculated on the costs of producing sugarcane and processing the sugar. The final price is the price realized by the sugarcane and which growers will receive for that season. This is calculated on the basis of the actual prices for sugar on domestic and export markets, which is announced at the end of the crushing season, usually in November.[24] The Cane and Sugar Fund makes compensation payments to mills on behalf of growers if the preliminary price of sugarcane paid to farmers is higher than the final price that the sugarcane realizes in that season.

.webp.aspx)