In 2020-2022, the palm oil sector is expected to register sluggish growth on the back of weaker demand. In addition, oil palm prices would continue to be pressured by oversupply as cultivated area had continued to grow since 2009 and global inventory levels are high. At the same time, domestic players have to contend with higher production costs than competitors abroad, growing concerns over the environmental and health impact of oil palm cultivation and consumption, and over a slightly longer time horizon, the trend towards electric vehicles. However, these headwinds will be partly offset by government support for the sector, specifically measures to encourage the switch to B10 as standard diesel mix and passage of the new Oil Palm and Palm Oil Act.

Overview

Palm oil[1] yield per unit of land is 6-10 times[2] higher than for other oil crops such as soy, rapeseed, sunflower, coconut and olive. This means oil palm has the lowest production cost among vegetable oils.

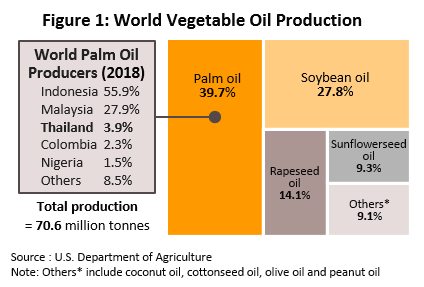

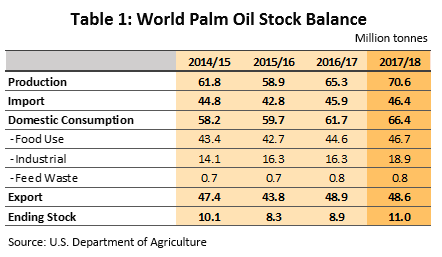

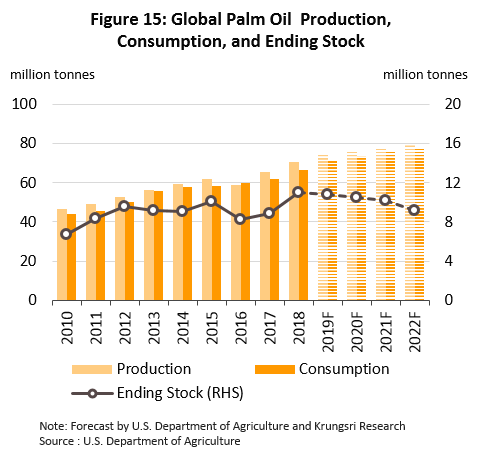

In 2018, global production and consumption of palm oil reached 70.6 million tonnes and 66.4 million tonnes, respectively. These represent 39.7% and 38.6% of total global vegetable oil production and consumption, respectively. The principal palm oil producing region is ASEAN, and because they are the largest producers, Indonesia and Malaysia have a large influence on palm oil prices on global exchanges. Indonesia produces 39.5 million tonnes of palm oil annually while Malaysia produces 19.7 million tonnes. Together, they account for 83.8% of combined global output. Naturally, these two countries are also major oil palm exporters, contributing 90% of global palm oil exports. Among the major importers of palm oil, India is the biggest at 18.6% of world imports in 2018, followed by the European Union (15.3%), China (11.5%), and Pakistan (6.5%). In 2014-2018, global demand for crude palm oil grew by an average of 3.4% per year driven by rising demand for both direct consumption and to produce alternative energy. Meanwhile, crude palm oil production rose at a slightly faster pace, averaging 4.5% p.a. As a result, total global stock of crude palm oil rose to 11.0 million tonnes at end-2018 (Figure 1 and Table 1).

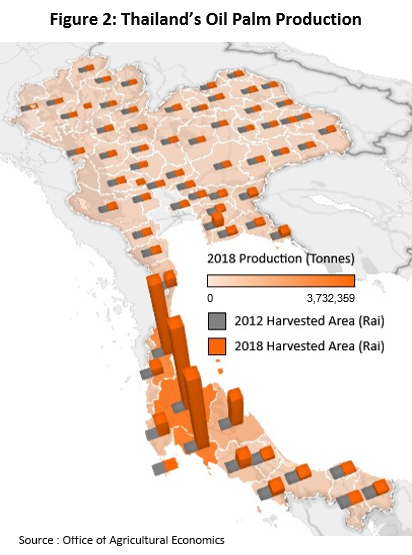

Thailand is third largest palm oil producer but it accounts for only 3.9% of global production. So, unlike Indonesia and Malaysia, Thailand has little influence on global palm oil prices. In Thailand, 86.4% of oil palm plantations and their processing facilities are located in the south[3], with the provinces of Krabi, Surat Thani, and Chumphon being home to 60% of the country’s oil palm plantations. The remaining 13.6% of oil palm plantations is found in the center, north and north-east regions of Thailand.

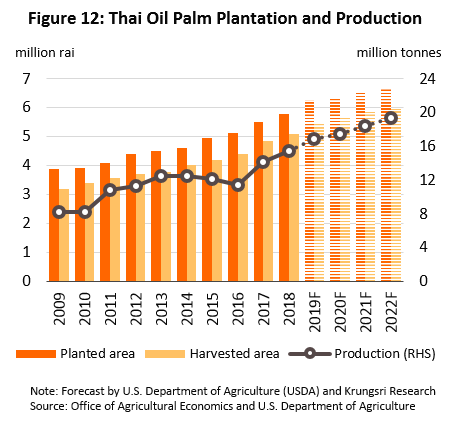

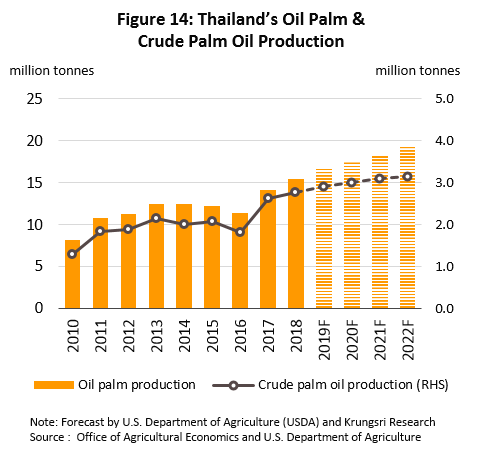

Oil palm cultivation had expanded in these regions between 2009 and 2018 under the government’s strategy to develop renewable and alternative energy supply (Figure 2). In 2018, total oil palm cultivated area nationwide reached 5.8 million rai (up 4.5% from 2017), with 5.1 million rai of matured estates (up 5.1%). In the same year, national output of oil palm products reached 15.4 million tonnes (up 9.1%)[4], which was refined into 2.8 million tonnes of crude palm oil (up 5.8%). (Source: The Office of Agricultural Economics).

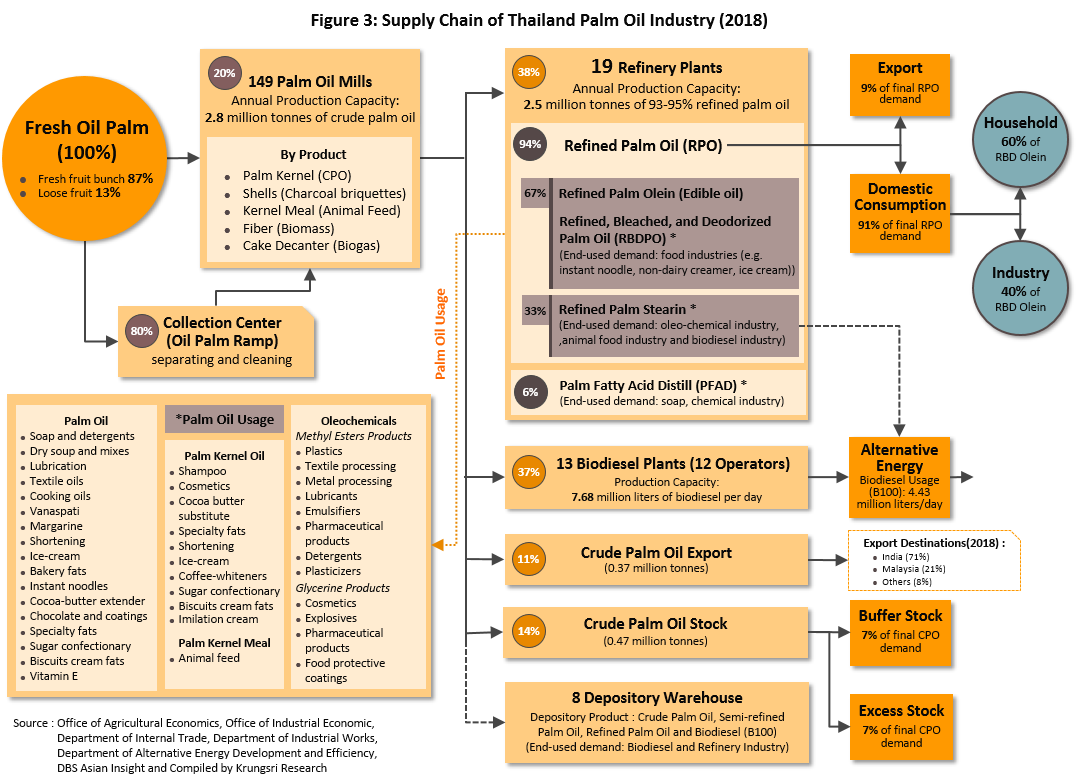

Thailand’s oil palm industry benefits from access to a comprehensive supply chain (Figure 3). (i) Oil palm cultivators (Upstream). About 0.24 million households across the country are involved in this sector, the majority (79%) of which are smallholders. Larger estates typically invest in their own mills to extract crude palm oil. (ii) Crude palm oil mills (Midstream). There are 149 mills in Thailand (source: Department of Industrial Works) and the Office of Industrial Economics (OIE) estimates they have the capacity to produce 2.8 million tonnes of crude palm oil per year. Larger mill operators are also investing in their own oil palm plantations and in developing new palm cultivars. The oil palm plant also produces a wide range of by-products that can generate additional income, such as kernel meal which is used to manufacture animal feed, and palm shells and fiber which can be used to produce biomass energy. (iii) Palm oil refineries (Downstream). There are 19 in Thailand and the OIE estimates these have an annual production capacity of 2.5 million tonnes. Large operators are often connected through investments in other parts of the oil palm supply chain including, for example, crude palm oil mills and vegetable (edible) oils business. But currently, the domestic palm oil refining capacity is insufficient to absorb the country’s crude palm oil supply, so mills depend on several other industries to take up the balance. They include the biodiesel (B100), electricity and steam generation, and biogas industries, and oil storage facilities.

Previously, Thailand did not have a plan to support the systematic development of the palm oil industry. For example, industry players who wanted to expand capacity had to deal with one government agency and a different agency was tasked with developing the national palm oil marketing strategy. Industry players that are involved in food production and oleochemicals (i.e. using chemical processes to produce consumer products from palm fat) are regulated by the Ministry of Industry, while the biodiesel industry is under the Ministry of Energy. Beyond this, productivity in the Thai palm oil sector is also relatively low and has limited its ability to compete in world markets. As a result, between 2014 and 2018, capacity utilization at Thai crude palm oil mills averaged only 43% and cost of production was higher than in Indonesia and Malaysia. We list selected productivity metrics: (i) fresh fruit bunches (FFB) output in Thailand is only 2.7 tonnes/rai compared to 3.3 tonnes in Malaysia and 2.9 tonnes in Indonesia; (ii) Thai farmers tend to harvest the FFB before they are fully matured, so the oil extraction rate (OER) averages only 17-18% compared to 20% in Malaysia and 22% in Indonesia[5]; and (iii) the majority of Thai oil palm cultivators are smallholders with an average plantation size of 20-25 rai each, whereas over 80% of oil palm produced in Malaysia and Indonesia is carried out by operators with plantations averaging over 200 rai each. In addition, plantations in Thailand are less efficient - from selecting cultivars, growing the oil palm, and harvesting and storing fruits through to selling. The oil palm fruit is often sold through middlemen at local collection centers because the small plantations find it less cost-effective to send their small harvest directly to mills[6]. Given these structural weaknesses, Thailand has been unable to liberalize the palm oil industry within the trade framework agreed for the ASEAN free trade area (AFTA) (ASEAN member states have agreed to apply zero-rate import duty on palm oil effective January 1, 2010, but Thailand continues to limit imports of palm oil to protect its domestic industry, and palm oil is one of 23 items on the country’s ‘sensitive list’). Thai officials will continue to manage the sector as they attempt to build competitiveness through almost the entire supply chain. As part of this effort, the government established the Thailand Oil Palm Board which is responsible for managing policy and development plans for the domestic palm oil sector, allocating oil palm output for retail consumption and industrial use, and controlling imports of FFB and palm oil[7]. The Board also buys up surplus palm oil when the market is facing a supply glut and prices are low. Meanwhile, the Department of Internal Trade, under the Ministry of Commerce, is responsible for setting purchase prices for FFB and palm oil[8].

- Purchase price for FFB is set by the Central Committee on the Prices of Goods & Services (under the Department of Internal Trade). They specify a general reference price for FFB based on an agreed level of oil content. In 2017, this was raised to 18% oil content (from 17% prior to 2017). The intention is to encourage Thai farmers to harvest ripe FFB - which have higher oil content – in order for them to fetch higher selling prices.

- Price for crude palm oil (CPO) is set with reference to input cost (i.e. domestic cost of FFB, milling and other costs) and global price trends for CPO. As at September 2019, CPO purchase price is THB16.2/kg (down -15.1% YoY).

- Retail price of bottled refined palm oil is determined by the Department of Internal Trade but the Department has since allowed this to float. The last time the price was fixed was in September 2019, at THB30.0/kg (inclusive of VAT)[9].

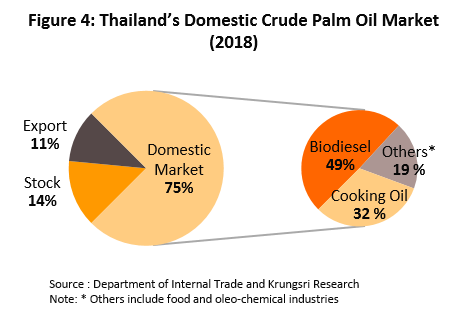

Given the factors above, the cost of producing palm oil in Thailand is naturally higher than in Indonesia or Malaysia, sometimes up to 10% higher[10]. This restricts the ability of Thai palm oil products to compete effectively in the export markets. Hence, around 75% of CPO originating in Thailand is consumed domestically. Exports account for only a small fraction of total output, and is volatile depending on surplus production. However, since 2017, Thai authorities have been trying to increase exports to absorb excess domestic production. Looking at palm oil import data, they tend to be spotty and normally rise when stocks of crude palm oil fall below the domestic buffer level, which is set at 225,000-250,000 tonnes[11].

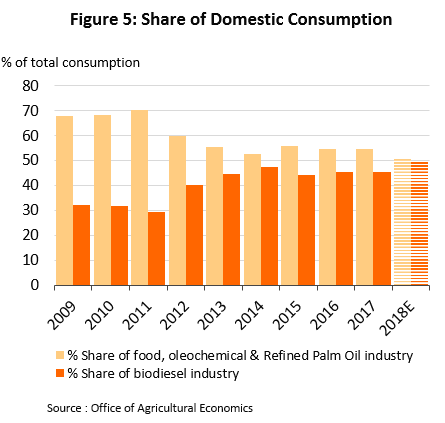

Domestic demand for palm oil originates from two main areas (based on 2018 data). (a) 68% of consumption is bound for other industries which use palm oil to make other products. These include: (i) biodiesel (or B100), which absorbs 49% of total domestic palm oil output. It is mixed with mineral diesel for use as fuel for vehicles, although the proportion of biodiesel used in the mix varies depending on the quantity of biodiesel available in the domestic market. In 2015, the standard diesel mix was reduced from B7 to B3.5 because of a shortage of CPO supply, while in 2019, the mix was increased from B7 to B10 as authorities tried to soak up excess CPO supply; (ii) food products (16% of output), where palm oil is used to produce snacks, instant noodles, sweetened condensed milk, creamer, margarine, shortening, ice cream, and food supplements such as vitamins; and (iii) chemicals and oleochemicals (3% of output) for use in the manufacture of soaps, cosmetics and shampoo, among other things (Figure 5). (b) The remaining 32% of Thai CPO production is refined by downstream industries for retail use.

Situation

A severe drought between 2014 and 2016 reduced Thailand’s CPO output to an 8-year low of 11.4 million tonnes in 2016 (Figure 6). This pushed up prices to a 5-year high of THB32/kg in 2016, rising 16.9% from 2015 average of THB 27.3/kg (Figure 7). This widened the gap between domestic and global prices to THB11-12/kg.

In 2017 and 2018, CPO output rose and depressed prices. This was because of favorable weather, especially higher rainfall, and also output from new plantings in 2008-2012 encouraged by government policy. FFP output rose to over 15 million tonnes per year and FFB yield increased from an average of 2,872 kgs/rai in 2014-2016 to 2,918 kgs in 2017 and to 3,024 kgs a year later. However, the sharp rise in supply pushed down FFB price to THB2.3/kg in December 2017, the lowest in almost 12 years (Figure 7).

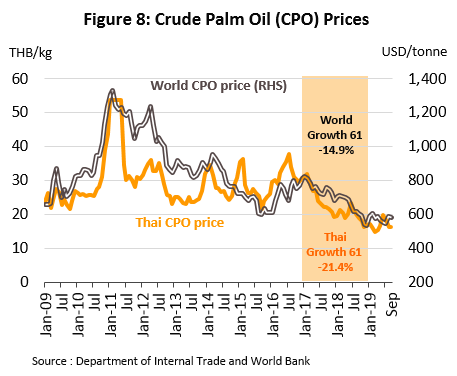

Improvements in FFB harvesting technology and processes also helped to raise CPO output by 45.6% to 2.6 million tonnes in 2017 and by another 5.8% to 2.8 million tonnes in 2018. Apart from the sharp rise in domestic CPO output, several other negative factors also hurt exports. They included high global inventories, the EU phasing out the use of biofuels derived from palm oil effective 2021, and India hiking import duties on all vegetable oils (duty on CPO was raised from 15% to 30%, while duty on refined palm oil was raised from 25% to 40%). As a result, domestic CPO prices fell more than global prices (Figure 8). The average price of Thai CPO fell 22.2% to THB 24.9/kg in 2017 and by another 21.4% to THB19.6 in 2018.

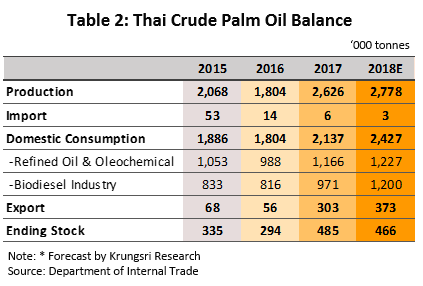

Meanwhile, domestic demand for crude palm oil also rose in line with Thailand’s economic growth, to 2.1 million tonnes in 2017 (up 18.5%) and and 2.4 million tonnes in 2018 (up 13.6%). There was especially strong demand from downstream industries to process into refined palm oil and to produce oleochemicals. There was also rising demand from biodiesel manufacturers, encouraged by supportive government policies, including raising standard diesel mix to B7 (i.e. 7% biodiesel) effective May 8, 2017, and promoting the use of B20 in large trucks effective July 1, 2018. The government also intensified efforts to absorb excess supply of CPO in the system by: (i) asking biodiesel producers and traders to increase their stockholdings; (ii) absorbing 160,000 tonnes of CPO to generate electricity; and (iii) promoting the export of 0.3 million tonnes of CPO per year. The latter lifted 2017 exports by 441% to 0.3 million tonnes and 2018 exports by 23% to 0.37 million tonnes from an average of 0.21 million tonnes per year in 2012-2016. Almost 90% of exports went to India, and the rest to other countries in Asia including Myanmar, Malaysia, Cambodia, and China. However, despite higher consumption, demand for CPO was insufficient to reduce stocks to reasonable levels (estimated at 225,000-250,000 tonnes). It rose to 470,000 tonnes at end-2018 (Table 2).

Throughout 2019, the domestic palm oil industry faced a supply glut which pushed down CPO prices to a 14-year low.

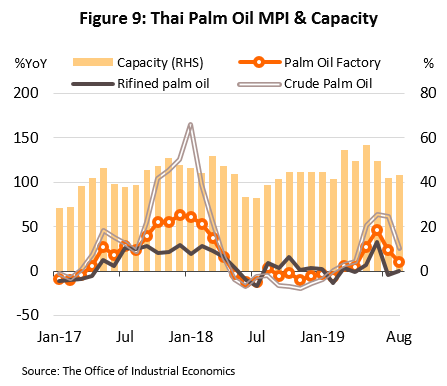

- In 2019, FFB and CPO output hit new highs in Thailand. The Office of Agricultural Economics estimates that in 2019, a total of 5.45 million rai of palm oil plantations were producing palm fruits (+7.1% ). The Ministry of Commerce forecast FFB output increased by 9.2% to a new high of 16.8 million tonnes (from 15.4 million tonnes in 2018). FFB yields also rose, climbing 1.9% to 3,083 kgs/rai. This produced 2.9 million tonnes of CPO, up from 2.6 million tonnes in 2018. This increase pushed up the manufacturing production index for the sector by 11.7% YoY in 8M19 (Figure 9).

- But demand for CPO lagged behind supply, and prices slipped during the year. The Ministry of Commerce estimates demand for CPO reached 2.5 million tonnes in 2019 (up 1.4%), comprising (i) 1.2 million tonnes for household consumption and industrial use, especially for refining and to produce oleochemicals, and (ii) 1.2-1.3 million tonnes used as alternative energy source. However, with supply reaching 2.9 million tonnes and 2018 stock added 0.47 million tonnes to this, FFB and CPO prices dropped to 14-year lows of THB1.9/kg (in April) and THB14.7/kg (in March), respectively.

Given this situation, the government responded by attempting to syphon off some of this excess supply and so return a degree of stability to the market and thus help prices recover. In pursuit of this, the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) was instructed to burn 0.3 million tonnes of CPO with natural gas to produce electricity[12], grants of THB 1,500/rai were made to palm growers, between December 1, 2018 and September 30, 2019 the retail price of B20 was kept THB 5/liter cheaper than that of B7 (the standard diesel mix), and the standard diesel mix was then raised to B10 with effect from January 1, 2020. These measures helped to remove a portion of excess supply from the market and prices subsequently recovered slightly; as of October 2019, the price of fresh palm stood at THB 2.77/kilogram, while that for CPO had risen to THB 16.63/kilogram.

- Exports of CPO fell by 18.8% YoY in 9M19, dropping to 0.25 million tonnes from 0.31 million tonnes in the same period a year earlier. Thai exporters continue to face difficulties arising from the depressed state of the world market and the supply glut that has affected global exchanges since the decision by the EU to halt consumption of palm oil in 2020-2021. This has had a dire impact on prices and these have slipped to their lowest level in 14 years, falling to USD 575/tonne from over USD 1,300/tonne in 2008. In addition, Thai exporters are further handicapped by the fact that India, a major export market, has cut duties on imports of CPO from Malaysia[13] and Indonesia but not from Thailand.

Krungsri Research believes that the continuing imbalance between the supply and demand of crude palm oil will increase stock holdings, and so these are expected to have risen to some 0.6 million tonnes by the end of 2019, a 29% rise from their 2018 levels and a full 2.4 times the levels of the buffer stock.

Industry Outlook

Between 2020 and 2022, Thailand’s palm oil industry will continue to experience a supply glut that will keep prices depressed. The glut would be supported by the following: (i) cultivated area is expected to expand by 0.3 million rai per year over the next few years, partly to meet the government’s target to expand to 10 million rai to ensure a secure source of alternative energy (the target area is northeastern Thailand). This would be compounded by the fact that oil palm bear fruit throughout the year;

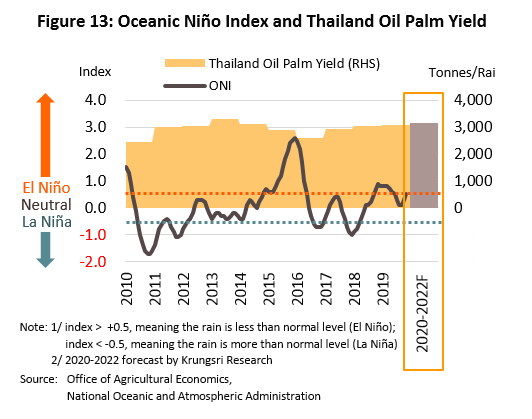

(ii) an influx of maturing oil palms (over 8 years old) planted earlier that are now producing high yields[14]; and (iii) more favorable climate[15] and rainfall in the south is expected to return to normal levels, which will improve yields (Figure 13). Given these factors, domestic CPO output is projected to increase to 3.0-3.2 million tonnes per year (Figure 14).

Domestic demand for crude palm oil will also grow over the next three years. But it would be limited by relatively weak economic growth and continue to lag behind new supply. Over the next few years, industrial demand for palm oil will be driven by the following.

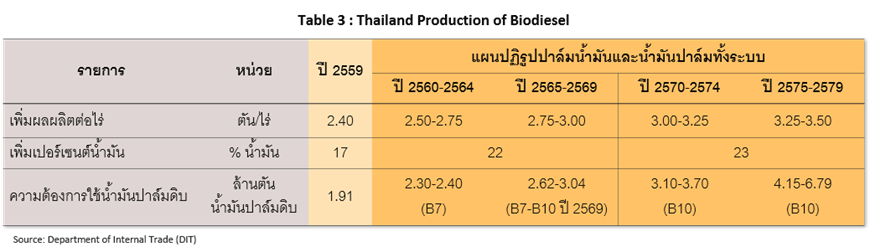

- Biodiesel industry: There will be strong demand in the coming period. National consumption of biodiesel is expected to rise to 5.8-6.4 million liters per day (rise by 5-10% per year). This would be supported by: (i) growth of the transport and logistics sector, especially land transport. Krungsri Research forecasts the national diesel-powered vehicle fleet would grow by 5-6% annually, which would raise diesel consumption by 3% annually; and (ii) the decision to raise standard diesel mix from B7 to B10 (with effect from January 1, 2020) and plans to set B20 as the standard mix. Following the mandate to use B10 diesel mix, the biodiesel industry would require about 2 million tonnes of CPO per year. This move mirrors that made by Malaysia (which plan to shift from B7 to B20) and Indonesia (from B20 to B30 this year).

- Refined palm oil: Demand for CPO to be processed into refined palm oil will grow only mildly. Domestic palm oil refining capacity utilization averaged only 43.4% between 2017 and 2019, compared to 91.2% for the soy oil and 66.7% for the rice bran oil which are alternative products which prices are similar to palm oil16/. In addition, the relatively high high content of saturated fats in palm oil makes it less popular than other edible oils among health-conscious consumers.

- Oleochemicals industry: Growth in the oleochemicals industry will support rising demand for CPO and palm fat (produced from virgin pressing of palm fruits). Growth would be fueled by rising consumption of downstream products, such as detergent, soap, medicines and cosmetics. Thailand recently introduced measures to support the growth of the oleochemical industry by expanding output of bio-lubricants; the global market for bio-lubricants is estimated to increase from THB85bn in 2018 to THB 125bn by 2026. If Thailand’s output increases along with global trends, it will also support demand for CPO and prices.

Krungsri Research forecasts domestic stocks of CPO will move in line with global trends, which means they will remain high. Demand will increase but it will not be sufficient to absorb the excess glut. As such, in 2020-2022, domestic CPO prices will mirror global prices and average THB 15-17/kg.

In the coming period, the Thai palm oil industry will face a several challenges. These will include rising concerns in developed economies over the environmental impact of oil palm cultivation; the strongest advocate is the European Union, one of the world’s major consumers of palm oil. The EU has introduced stringent measures to force member states to phase out the use of crop-based biofuels (including palm oil) that are planted in areas considered carbon sinks by 203017/. This has triggered the ‘zero palm oil’ movement in the transport sector. At the same time, rising concerns over the health consequences of palm oil consumption, particularly in reference to the high content of saturated fat and high proportion of carcinogenic chemicals in palm oil relative to other vegetable oils, are encouraging consumers to seek ‘palm oil free’ food products. Beyond this, there is the move by major importers (especially India) to introduce import restrictions to protect their domestic industries, the increasing use of electric vehicles, and still-high global inventories. These will force players to bring their operations in line with a rapidly changing business environment. However, despite the headwinds, Krungsri Research believes government commitment and plans to reform the palm oil industry (2017-2036), coupled with the introduction of a new act to regulate the production of palm oil and related products, will facilitate the setting up of a fund to manage palm oil supply. These will play an important role in driving sustainable growth in Thailand’s palm oil industry .

Important measures/projects related to the oil palm industry, 2018-2019

- Measures to balance the domestic palm oil market – The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand has been tasked with buying CPO to generate electricity during periods when the CPO supply glut is particularly acute.

- Measures to determine palm oil refining standards – The Ministry of Industry introduced measures to determine the minimum refining standards that palm oil refiners are required to meet (at least 18% for Group ‘A’ refined products and at least 30% for Group ‘B’). These were published in the Royal Gazette on April 23 and came into force on June 22, 2019.

- Set standards to promote diesel use – The Department of Energy Business has specified standards for particular vehicle types that should use B7, B10 and B20 diesel, and the cabinet has agreed to push forward the switch to B10 as standard diesel mix with effect from January 1, 2020.

- Income support program for oil palm cultivators – On August 27, 2019, the cabinet authorized payments to be made to oil palm cultivators, being the difference between the guaranteed price for FFB and reference price for farmers that operate plantations up to 25 rai in size. The guaranteed price is currently THB4/kg for 18% palm oil content.

Oil Palm and Oil Palm Products Act

This is still being developed and would be included in the Royal Gazette after it is approved. The Ministry for Agriculture and Cooperatives will present the draft to the cabinet for their consideration.

Plans for the Development of the Thai Oil Palm Sector

Plan to reform the oil palm and palm oil sector (2017-2036): This is issued by the Office of Agricultural Economics and the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. The objectives are as follows:

- To expand cultivated area and yield by at least 10% from current levels, and improve the efficiency of cultivation and other processes to increase CPO extraction rate to 22-23%. This would help to ensure sufficient palm oil output to meet future demand.

- To build domestic demand by (i) raising domestic consumption by an average of 3% per year, and (ii) encouraging the use of palm oil as a source of alternative energy. At the same time, the government would try to maintain palm oil exports at 0.3-0.7 million tonnes per year.

Alternative Energy Development Plan for 2018-2037 (AEDP2018): In 2018, the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (under the Ministry of Energy) revised its development plans and cut targets for biodiesel consumption to bring these in line with the Power Development Plan for 2018-2037 (PDP). It increased the proportion of energy produced from alternative and renewable sources, especially solar, biomass and waste-to-energy generation, but at the same time, targets for biofuel (especially from ethanol and biodiesel) were reduced premised on an increase in the use of electric vehicles (tentative plans biodiesel production to be reduced from 14 million liters to 8 million liters per day by 2037).

Krungsri Research’s view

Between 2020 and 2022, the palm oil industry will continue to experience a supply glut while demand growth will be slow. This means domestic prices will remain low, similar to prices in global exchanges. This will reduce profits in the industry.

- Oil palm cultivators: This group will remain exposed to risks. Although government intervention in the sector will help to keep the FFB prices above breakeven production cost, this would mostly help those with contracts to supply to mills. Price increases would be capped by excess supply of FFB, and small and independent growers will continue to face volatile demand from mills and collection yards.

- Palm oil mills: It will take time for the turnover of mill operators to improve, despite government efforts to support the sector and raise official energy standards (e.g. using CPO to generate electricity, encouraging the use of biodiesel, and supporting palm oil exports). Total milling capacity currently exceeds domestic requirement and the quantity of FFB available for processing, so capacity utilization remains low. Processors also compete for access to input, which has increased CPO production cost. This would eat into profitability or could cause mills to book stock losses. This risk is high especially for smaller mills that are not part of an extended supply chain.

- Palm oil refiners: Earnings and profitability should remain normal because CPO costs remain low. However, the price of soy oil (an alternative to palm oil) is also low and this will cap growth of the palm oil market.

- Traders of crops used in the production of vegetable oils (FFB collection centers): Income for middlemen and operators of bunch collection centers will rise along with palm oil output because the majority of Thai oil palm cultivators are smallholders and depend on sales to these yards.

[1] น้ำมันปาล์มสามารถสกัดได้จากเนื้อปาล์มและเนื้อในเมล็ดปาล์ม ปัจจุบันการผลิตน้ำมันจากเนื้อปาล์มมีสัดส่วน 89.4% ของผลผลิตน้ำมันปาล์มทั่วโลก

[2] ผลผลิตน้ำมันต่อไร่ของพืชให้น้ำมันแต่ละประเภท มีดังนี้ เนื้อปาล์มน้ำมันสกัดน้ำมันได้ 512 กก./ไร่ เมล็ดใน ปาล์มน้ำมัน (Kernel) 73 กก./ไร่ เรปซีด 89 กก./ไร่ เมล็ดดอกทานตะวัน 81 กก./ไร่ มะพร้าว 54 กก./ไร่ ถั่วเหลือง 52 กก./ไร่ และถั่วลิสง 51 กก./ไร่

[3] โรงสกัดน้ำมันปาล์มดิบมักตั้งอยู่ใกล้แหล่งวัตถุดิบ เนื่องจากผลผลิตปาล์มน้ำมันสดที่ตัดแล้วควรขนส่งให้ถึง โรงงานสกัดภายใน 24 ชั่วโมง เพื่อให้ได้น้ำมันปาล์มคุณภาพสูง

[4] โดยทั่วไปต้นปาล์มน้ำมันเริ่มให้ผลผลิตเมื่อมีอายุ 3.5-4 ปี และจะมีอัตราให้ผลผลิต (Yield) สูงสุดในช่วงอายุ 7-16 ปี จากนั้นผลผลิตจะทยอยลดลง แต่ยังสามารถให้ผลผลิตได้ถึงอายุ 25 ปี

[5] การสกัดน้ำมันปาล์มดิบของมาเลเซียอ้างอิงจาก Malaysian Palm Oil Board เป็นค่าเฉลี่ยช่วงมกราคม - สิงหาคม 2562 ส่วนอินโดนีเซียจากรายงานประจำปีของบริษัท IJM Plantations Berhad เป็นค่าเฉลี่ยปี 2561 - 2562

[6] จากการรวบรวม พบว่า ลานเทปาล์มน้ำมันมักรับซื้อผลปาล์มในราคาหน้าโรงงาน หักค่าบรรทุกประมาณ 0.10-0.25 บาท/กิโลกรัม และค่าบริการประมาณ 0.05 บาท/กิโลกรัม

[7] กนป. กำหนดให้องค์การคลังสินค้าเป็นผู้นำเข้าน้ำมันปาล์มในช่วงที่มีปัญหาขาดแคลนแต่เพียงผู้เดียว โดยกำหนดอัตราภาษีนำเข้า ดังนี้ 1) การนำเข้าในโควตาไม่เกิน 4,860 ตัน คิดอัตรา 20% 2) การนำเข้านอกโควตาคิดอัตรา 143% และ 3) การนำเข้าตามกรอบข้อตกลงการค้าเสรีอาเซียน (ASEAN Free Trade Area: AFTA) คิดอัตรา 0%

[8] อ้างอิงจากโครงสร้างการคำนวณราคาประมาณการของผลปาล์มน้ำมัน น้ำมันปาล์มดิบ (CPO) และน้ำมันปาล์มขวด 1 ลิตร ซึ่งประกาศโดยกรมการค้าภายในเมื่อวันที่ 26 ก.ค. 62

[9] ตั้งแต่เดือนกุมภาพันธ์ 2562 เป็นต้นไป กรมการค้าภายในประกาศให้ราคาน้ำมันปาล์มบริสุทธ์บรรจุขวดลอยตัวตามกลไกตลาด จากเดิมกำหนดราคาเพดานขาย (Ceiling Price) สูงสุดไม่เกิน 42 บาท/ขวด

[10]อ้างอิงข้อมูลเปรียบเทียบโครงสร้างต้นทุนการผลิตน้ำมันปาล์มดิบ (ปี 2556) ของสำนักงานเศรษฐกิจการเกษตรและกรมการค้าภายใน

11/ สินค้าคงคลังสำรองหรือสินค้ากันชน (Safety Stock/Buffer Stock) คือ ปริมาณสินค้าคงคลัง (ในที่นี้คือปริมาณน้ำมันปาล์มดิบ) ที่ทางองค์การคลังสินค้า (อคส.) กักเก็บสำรองเพื่อป้องกันการขาดแคลนวัตถุดิบระหว่างการผลิตหรือการบริโภคของอุตสาหกรรมที่เกี่ยวเนื่องภายในประเทศที่เพิ่มขึ้นกระทันหัน ทำให้ผู้ผลิตยังสามารถผลิตสินค้าได้ต่อเนื่องโดยไม่ขาดแคลนน้ำมันปาล์มที่เป็นวัตถุดิบสำคัญ โดยกระทรวงพาณิชย์เป็นผู้กำหนดหรือควบคุมให้อยู่ในระดับที่เหมาะสมซึ่งปัจจุบันระบุว่าไม่ควรเกินระดับ 2.25-2.50 แสนตัน

[12] คณะกรรมการนโยบายปาล์มน้ำมันแห่งชาติ (กนป.) มีมติให้กระทรวงพลังงานโดยผ่านการไฟฟ้าฝ่ายผลิตแห่งประเทศไทยรับซื้อน้ำมันปาล์มดิบจากผู้ประกอบการโรงสกัดน้ำมันปาล์มดิบ เพื่อลดระดับสต๊อกส่วนเกินที่อยู่สูงกว่าระดับสต๊อกสำรอง (Buffer Stock) รวม 3 ครั้ง ได้แก่ วันที่ 20 พฤศจิกายน 2561 อนุมัติให้รับซื้อจำนวน 1.6 แสนตัน วันที่ 7 พฤษภาคม 2562 จำนวน 2 แสนตัน และวันที่ 27 สิงหาคม 2562 จำนวน 1 แสนตัน

[13] อินเดียลดภาษีนำเข้าน้ำมันปาล์ม (RBD Palmolein) ให้แก่มาเลเซีย ตามความตกลง Malaysia-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (MI-CECA) จาก 54% เหลือ 45% ส่วนไทยเสียภาษีนำเข้าในอัตรา 50%

[14] ต้นปาล์มน้ำมันที่ปลูกตามนโยบายส่งเสริมช่วงปี 2551-2555 จะมีอายุระหว่าง 8-12 ปี ซึ่งอยู่ในช่วงอายุที่ให้ผลผลิตสูง (อายุที่ต้นปาล์มให้ผลผลิตสูงคืออยู่ระหว่าง 7-16 ปี อ้างอิงจากสำนักงานเศรษฐกิจการเกษตร)

[15] จากข้อมูลของ NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) ในช่วง 60 ปีที่ผ่านมา พบว่าปรากฎการณ์ El Nino และ La Nina รุนแรงจะเกิดขึ้นทุกๆ 12-15 ปี (La Nina รุนแรงเกิดขึ้นล่าสุดในช่วงปี 2553-2554 และ El Nino รุนแรงเกิดขึ้นล่าสุดในช่วงปี 2558-2559) ในขณะที่ปี 2562 เกิดภัยแล้งอย่างอ่อน (Weak Elnino) ซึ่งส่งผลไม่รุนแรงมากแก่พืชปาล์มน้ำมัน

[16] น้ำมันปาล์มมีข้อดีคือ ไม่มีกลิ่นหืนและทอดได้กรอบมากกว่าน้ำมันพืชชนิดอื่น รวมถึงไม่เกิดควันเมื่อผัดหรือทอดอาหารที่อุณหภูมิสูง อีกทั้งมีราคาถูกจึงเป็นที่นิยมใช้ในธุรกิจร้านอาหาร แต่ข้อเสียคือ มีกรดไขมันอิ่มตัวสูง และกรดไลโนอิกทำให้เกิดคอเลสเตอรอลสูงได้