Sugar is a product obtained from plant sources that is used as a sweetner[1]. Global demand for sugar is high, both for consumption directly and as an additive in a wide range of industries, including soft drinks, processed-milk products (milk, butter, yoghurt, etc.), sweets, baked goods and so on. In 2016, sugar accounted for over 80% of all sweeteners consumed globally, with products such as high intensity sweetener (HIS), an artificial sweetener, and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a product obtained by processing corn, making up the difference.

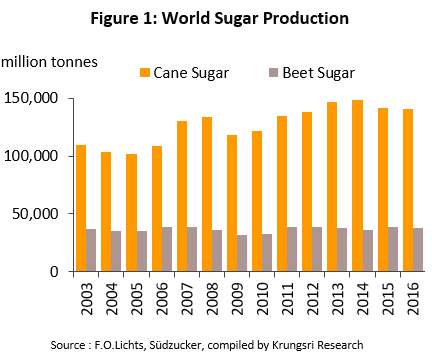

Approximately 85% of all sugar produced globally comes from sugarcane (Figure 1), which grows in equatorial regions such as Brazil and parts of Asia-Pacific. The remaining 15% comes from beet, which is grown in Europe, parts of the United States, Canada, and China. In 2016, combined

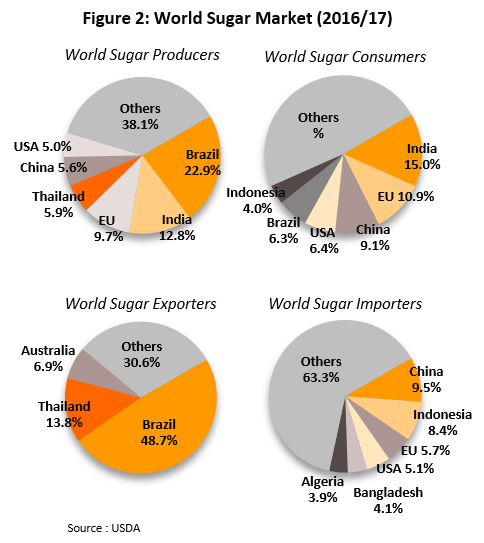

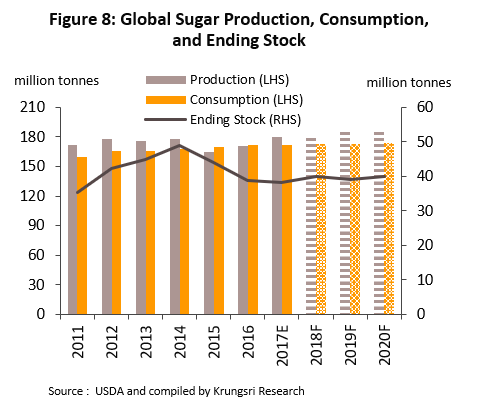

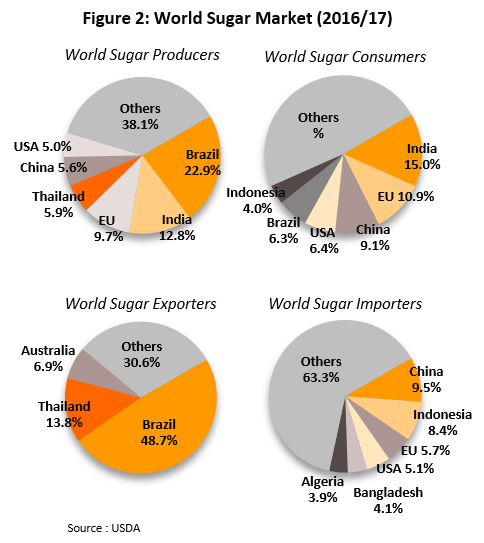

A total of some 55-60 million tonnes of raw sugar, or a third of world production, is traded on world markets, although the volume that is actually sent for export will depend on the production and export policies of those exporting countries and on demand in countries which either do not produce their own sugar or produce it in insufficient quantities to meet domestic demand. International trade in sugar is therefore one factor which helps to determine trends in prices on global markets. In terms of net exports, the countries that play the most important role in supplying world sugar markets are Brazil, which has a 48.7% market share, Thailand (13.8%), and Australia (6.9%). The biggest net importers of sugar are China, Indonesia, the European Union, and the United States (Figure 2).

In addition to basic supply and demand, world prices for sugar are also influenced by the commodities futures markets since speculation on sugar on futures markets is so widespread. Futures markets which are at present influential and which help to determine reference prices include the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), the Brazilian Mercantile and Futures Exchange (BF&M), the Kansai Commodities Exchange (KEX), the Multi Commodity Exchange (MCX), and the National Commodities and Derivatives Exchange (NCDEX).

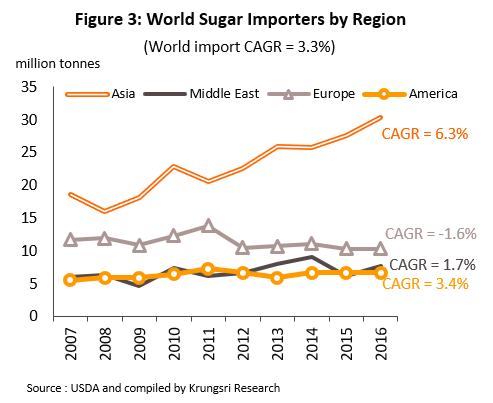

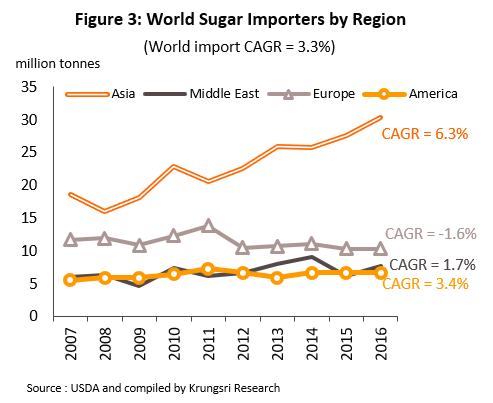

The Thai processed sugar sector enjoys a number of advantages that enable it to compete effectively on world markets. The cost of producing Thai sugar is at the relatively low level of 13.6 cents/lb2/, a figure which is only beaten by Brazil, where the cost of sugarcane is 11.2 cents/lb. In addition, Thailand is centrally located in Asia, a region with high levels of demand for sugar imports. Indeed, between 2007 and 2016, imports of sugar in Asia grew by 6.3% per annum, significantly faster than global growth in imports, which ran to 3.3% per annum (Figure 3). Thailand is close to these major markets and so transportation costs are lower, particularly in the cases of China (most exports of sugar from Thailand to Myanmar and Cambodia are in fact for re-export to China), Indonesia, India, and Japan, all countries which are continuing to increase imports of sugar[3].

The Sugarcane and Sugar Act of 1984 has also helped to strengthen the domestic processed sugar sector by systematically safeguarding the industry in the following ways:

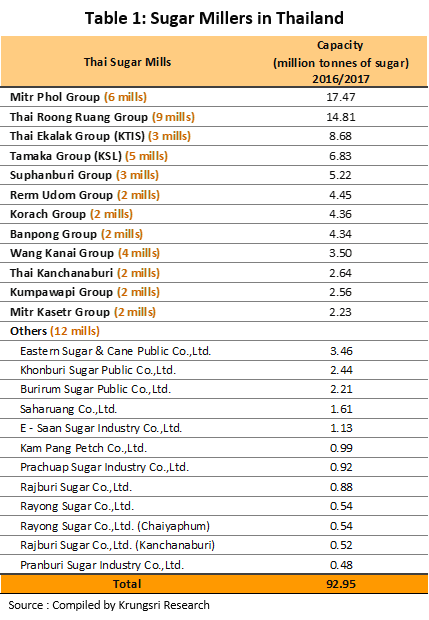

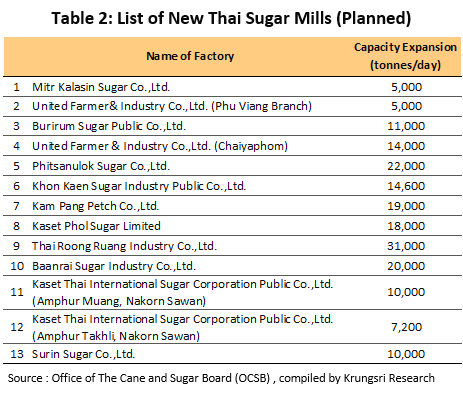

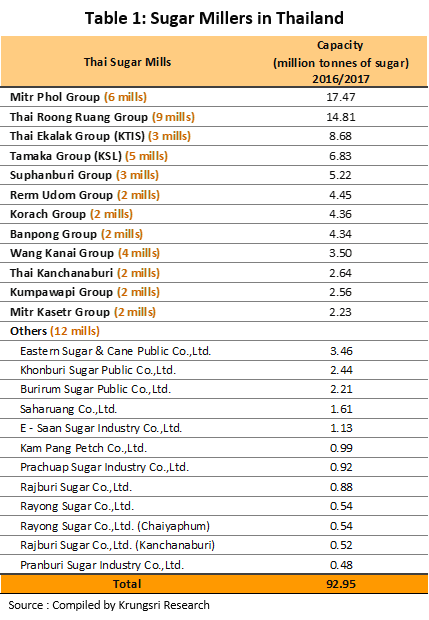

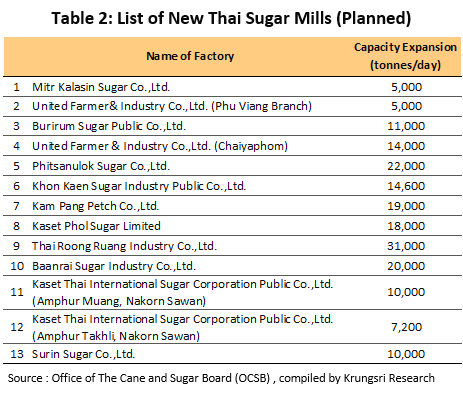

- The Act provides a mechanism for controlling the number of players in the sector. Operators are required to obtain permission from the authorities if they wish to open a new mill or to expand an existing one and so the state is able to control both the total number of plants and the national production capacity, or expressed in another way, to protect the income of existing players from competition from new entrants. However, over the last 7-8 years, officials have issued permits for new mills twice, in 2010 and again in 2015. These were the first new permits issued since 1989 and raised the number of sugar processing plants from 46 in 2010 to 54 in 2017, the majority of these being new mills operated by existing players in the sector (Table 1). One new permit for exporter was also granted in 2017, adding to the previous six permitted operations[4]. There are also more than ten more mills which have received permits and that will come on stream by 2021, most of which are operations for which permission was granted in 2015. (New plants are required to begin operations within five years of their permit being granted.) (Table 2).

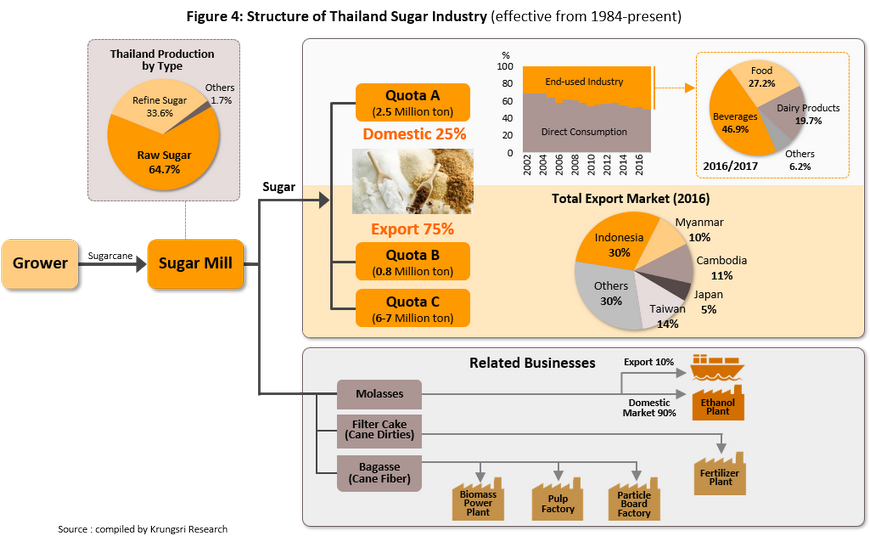

- A revenue-sharing system (the ‘70:30 system’) is enshrined in the law and this splits revenue between sugarcane growers and sugar millers. The system splits incomes from distribution to domestic and export markets for each growing season between sugar growers, who receive 70% of incomes as ‘compensation for the sugarcane price’, and sugar millers, who receive 30% as ‘compensation for sugar production’. This system helps to reduce the risk of fluctuations in the price of sugarcane paid by mills and the result of this is that sugar millers enjoy stable gross profits (i.e. income less the cost of sugarcane). The system also allows Thai mills to manage costs better than can those in other countries, helps to develop upstream segments of the supply chain (i.e. sugarcane production) and provides security of supply of raw materials.

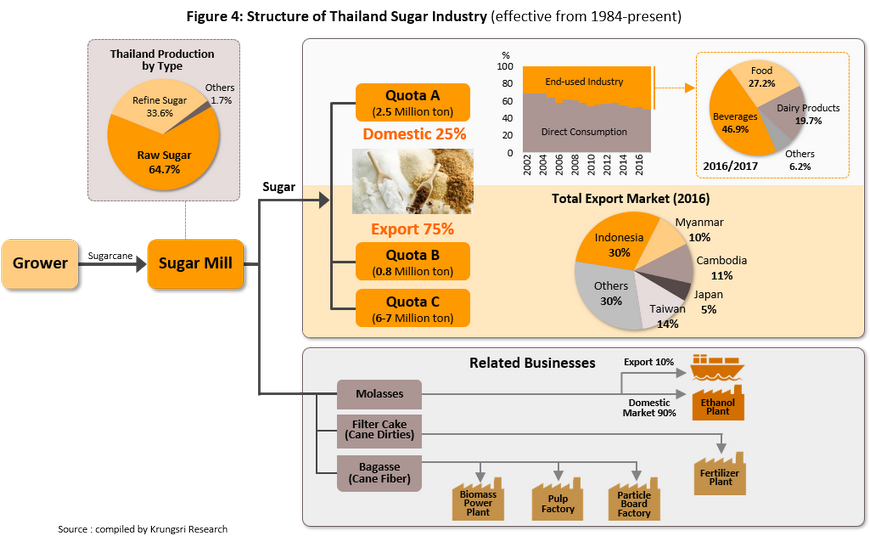

- The amount of sugar produced for domestic and export markets is also controlled through a three-part quota system. (i) ‘Quota A’ specifies the amount of sugar bound for the domestic markets, determined in terms of refined white sugar. Domestic demand is estimated annually and the quota set so that this is met. In the past, ‘quota A’ has taken 25-30% of total domestic output. (ii) ‘Quota B’ sets the amount to be exported by the Thai Cane and Sugar Corporation Ltd. This is fixed at 800,000 tonnes of raw sugar per year[5]and the price which this realizes is used to calculate reimbursements made under the revenue sharing agreement. (iii) ‘Quota C’ is calculated as the remainder of national production less quota A and quota B and this is then sold on export markets by individual operators. Officials will set quotas annually for domestic and international distribution for each individual processor, taking into account the quantity of sugarcane which is pressed in the mill and the amount of sugar which is produced.

- The law also controls prices by stipulating that the domestic price of sugar be set by the authorities[6]. Officials specify the factory-gate prices of white refined sugar and of pure refined sugar, which are currently at THB 20.30/kg and THB 21.40/kg, respectively (fixed by an announcement by the Ministry of Commerce in 2012). Producers have to make contributions to the Cane and Sugar Fund of THB 5/kg and so their income is currently THB 15.0-16.5/kg, or USD 450-515/tonne. This is higher than the world price of refined sugar which, over the past three years, has averaged USD 435/tonne and so this helps to maintain elevated levels of income[7] for Thai sugar producers and to keep them in profit.

- The government set up the Cane and Sugar Fund (CSF), which has a statutory obligation to research, develop, and promote the production, use, and distribution of sugarcane and sugar. The CSF is also responsible for maintaining a stable price for domestically consumed sugar but its most important duty is to compensate sugar millers with the difference when in one producing season, the price of sugarcane falls so that the preliminary price, which mills pay for all their sugarcane, is higher than the final price of the sugarcane[8].The CSF also pays subsidies on sugarcane prices in some seasons and so Thai sugarcane growers are relatively insulated from fluctuations in sugar prices on world markets.

In 2017, Thai sugar mills had the capacity to process around 100 million tonnes of sugarcane and to produce 10-11 million tonnes of raw and refined sugar. The most important players in the market are the Mitr Phol and Thai Roong Ruang groups, which have a market share of 19% and 16%, respectively. These two groups are also important on the world stage, though especially Mitr Phol Group, which has invested in production facilities in many countries. F.O. Licht reports that on 2016 data, Mitr Phol and Thai Roong Ruang have a total capacity in all their production facilities which places them 5th and 13th in the world rankings of sugar producers, respectively.

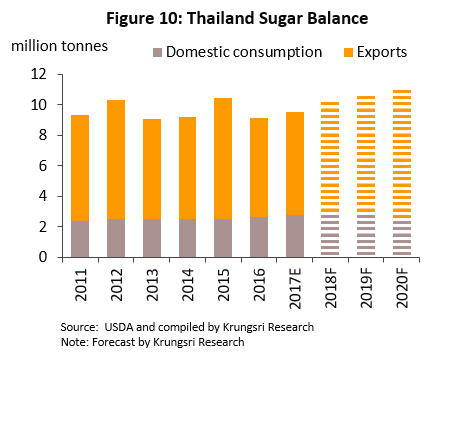

The Thai sugar sector is increasingly reliant on exports for income, and 75% of all Thai sugar production is now exported, mostly to Asia since these markets are close and Thailand therefore enjoys advantages in terms of transportation costs. Indonesia is the biggest export market, taking 25% of Thai exports by value, followed by Myanmar (23%), Cambodia (9%) and Japan (9%). The remaining 25% of domestic production is consumed on the Thai market, and by quantity, 55% of this is for household use, while 45% is used in food-related industries such as drinks (45% of the quantity of sugar used in industry), food and milk products.

In addition, Thai sugar millers also generate additional income from distributing the by-products of sugar processing, such as molasses. Currently demand for molasses for the production of ethanol is growing steadily thanks to government support for the use of ethanol fuels and so this can represent a significant source of earnings[9]. Some players have also invested in connected industries that use sugar by-products as raw materials. Examples of these include the production of biomass energy[10], pulp for paper production, fertilizer and particle board.

Situation

Since 2011, the global sugar sector has been affected by unstable but declining prices (prices are quoted on the benchmark ‘Sugar No. 11’ prices on the New York market) since they hit a peak of 32.09 cents/lb (average prices for January 2011).

- Between 2011 and 3Q15, the global price of sugar slid steadily following an easing of speculative pressures on commodities markets. In addition, sudden increases in the price of sugar and sugarcane in the preceding few years had fed both an expansion of the area under cultivation and an increase in the number of mills and the level of processing capacity around the world and so supply to world markets rapidly expanded. The resulting increase in stocks put downward pressure on prices for raw sugar and these fell continuously to a low of 10.7 cents/lb, the average for August 2015.

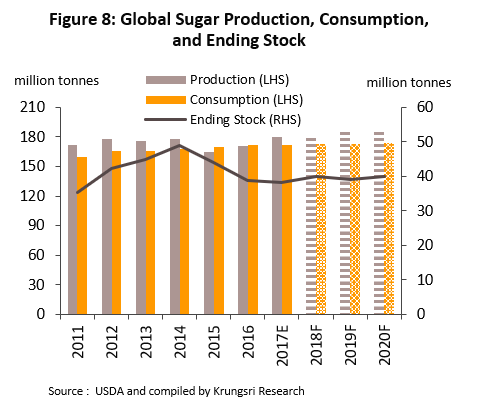

- From the end of 2015 through 2016, prices rose and the average price of 22.9 cents/lb seen in November 2016 was in fact the highest price for 56 months. Indeed, for the whole of 2016, average prices of 18.2 cents/lb were 37.5% higher than those in 2015. This rise in prices was triggered by the year’s extreme El Niño and the accompanying drought in Asia and heavy rains in Brazil, which led to cuts in sugarcane yields and so supply to world markets fell to 165 million tonnes (-6.8% YoY), while as a result of a strengthening world economy, demand increased by 1.2% YoY to 168 million tonnes.

- In 2017, prices again declined and the average price for raw sugar for the year was only 15.8 cents/lb (-12.7% YoY). Three factors were behind this fall. (i) The El Niño abated and weather patterns returned to more normal conditions so supply to world markets increased. (ii) An increasing supply of crude to world markets helped to depress oil prices and the cost of gasoline thus fell below the production costs of the ethanol mix, with the result that, despite government support for biofuels in many countries, global demand for and production of ethanol weakened. This was particularly the case in Brazil, where there was an increase in the amount of sugar produced following declines in the profitability of ethanol production because in Brazil, ethanol is produced from sugarcane. (iii) China instituted a new policy to support domestic farmers by tightening regulations on imports of sugar above quota levels and so the annual cutoff point for over-quota import tariffs was reduced from 2 million tonnes to 1 million tonnes above quota and for 2017, tariffs were increased from 50% to 95%. This helped to reduce imports of sugar to China and as trade on world markets weakened, prices fell accordingly.

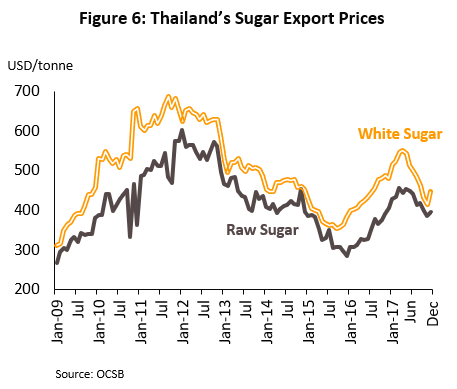

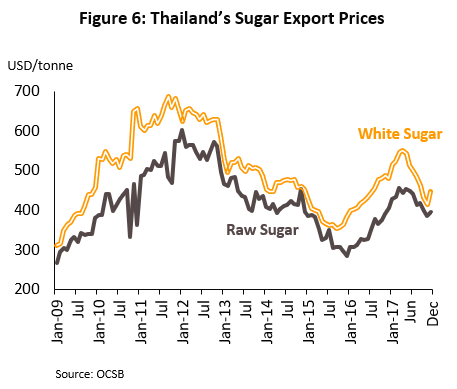

However, despite the situation on world markets, the state of affairs for prices for sugar distributed by Thai producers was somewhat more positive because the export of sugar operates on the futures market (typically, processing of inputs takes place over five months but distribution goes on throughout the year) and the timing of this favored Thai exporters. In addition, the growing seasons and so contracted delivery times of Thailand and Brazil differ (in Brazil, the season runs from April to October, while in Thailand, it begins in November and ends in April) and this helps to reduce competitive pressures in export markets. Moreover, the domestic price of sugar is higher than that on world markets and this helps to maintain profitability for Thai millers, while large operators also benefit from increased income derived from related businesses in, for example, molasses distribution, ethanol production and biomass energy.

Income for sugar mills in 2017 was at a healthy level, supported by an increasing output of sugar and the strong price of sugar in advance export contracts.

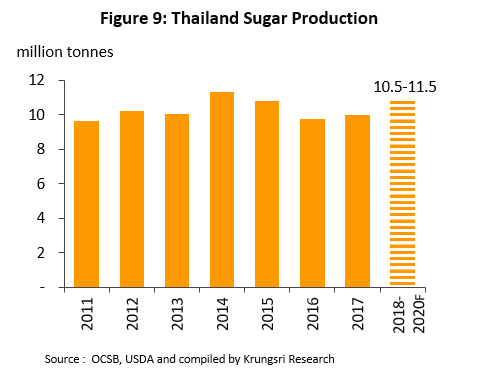

- Output of sugar by Thai mills increased by 2.5% YoY to 10 million tonnes as the sweetness of domestic sugarcane, measured by the commercial cane sugar (CCS) value, improved. This was despite the 2016 El Niño depressing yields of sugarcane for two years running; in the 2017 growing season (November 2016-April 2017) yields fell -1.2% YoY to 92.9 million tonnes.

- Income from exports (75% of production) grew solidly on high contract prices. By good luck, the period when advance contracts for the supply of sugar were agreed coincided with high world prices and so average prices for Thai exports were higher than world averages. In 2017, the volume of Thai exports shrank to 5.6 million tonnes (-12.0%), with falls being strongest in raw sugar (-23.5%), as rising output in Brazil prompted Brazilian producers to look for more export markets, especially in Indonesia but despite this, thanks to these high prices, the value of exports rose. For the year, exports were thus worth USD 2.61 bn (up 7.3% YoY), with Thai exports of raw sugar averaging USD 425.8/tonne (up 22.7%) and those of refined sugar averaging USD 493.9/tonne (up 11.8% YoY).

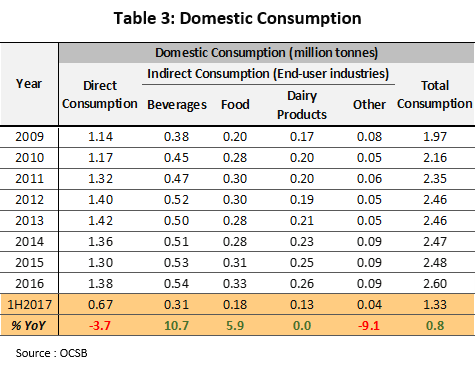

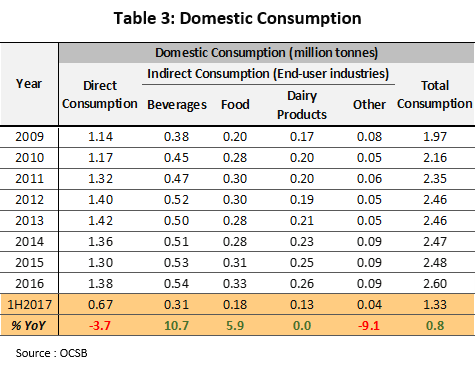

- Income from distribution to the domestic market (25% of output) should grow slightly relative to the previous year’s. The Ministry of Commerce has maintained sugar prices at the same level as last year (THB 20.30/kg for white refined sugar and THB 21.40/kg for pure refined sugar). The Office of the Cane and Sugar Board has announced that for 1H17, the total volume of sugar distributed to the domestic market increased by 0.8% YoY to 1.33 million tonnes, a result of increasing demand from industry (household demand fell relative to 1H16) (Table 3).

- Income from investments in businesses related to sugar processing continues to increase, especially in the case of ethanol production, which has benefited from a recovering economy feeding into growing demand and in 2017, demand for ethanol thus increased 7.6% YoY. Income from biomass energy production is also rising in line with generally increasing demand for electricity, particularly from commercial and industrial consumers.

Industry Outlook

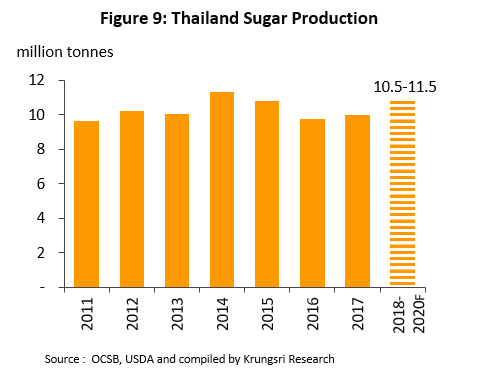

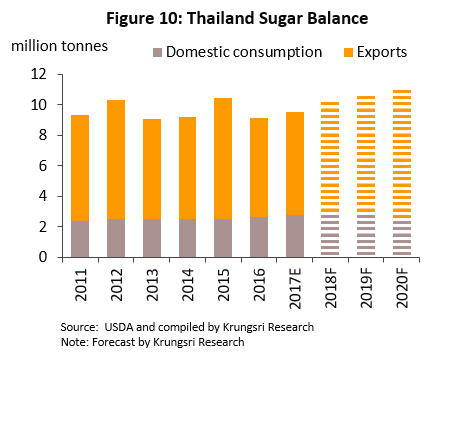

Over the period 2018-2020, turnover for operators should remain at healthy levels as yields of sugarcane and outputs of sugar rise. This analysis is supported by forecasts that climatic conditions are not expected to go through dramatic change[11] and the expansion of sugarcane cultivation that is anticipated in support of new sugar mills (in line with the planned investments for which permits have already been granted). As such, the total Thai sugar production is forecast to reach 10.5-11.5 million tonnes annually and millers will therefore need to increase exports, which for 2018-2020 are expected to average 7.5-8.5 million tonnes per year.

However, despite expectations that the volume of sugar distributed by Thai players will increase, income for operators is unlikely to rise substantially since world prices are forecast to remain at low levels. Beyond this, reform of the Thai sugar sector is being hastened by officials, as obligations and commitments made under WTO agreements[1]/ require. From 2018 onwards, these reforms will gradually have an impact on the sugar production system, especially in terms of the price of refined sugar, which is likely to fall.

- Global sugar exchanges will, between 2018 and 2020, likely continue to suffer from a glut. Although the forecast is for the world economy to see continuous growth in this period (the IMF forecasts growth of 3.9% per year over these three years), which will support growth in demand for sugar of 1-1.5% annually, growth in the supply of sugar to the global market is forecast to outrun this rise in consumption and this will depress prices. Supply pressures on world markets will come from the following.

- Brazil, the world’s biggest producer of sugar, may keep the proportion of sugar production higher than the previous level of 40% of all sugarcane since low oil prices are limiting demand for ethanol. An analysis of the data indicates that for the 2016-2017 growing season 53% of the domestic sugarcane crop was used for ethanol production and the remaining 47% for sugar production. For 2018, the forecast is that rising oil prices will have the effect of increasing the proportion of sugarcane used for manufacturing ethanol to 55% of the crop and for sugar production at 45%. (Krungsri Research forecasts that the price of WTI will average USD 64-66/barrel in the period 2018-2020, compared to an average of USD 53/barrel in 2017.)

- Production of sugar from beet in the EU is set to increase dramatically and exports from the EU to world markets will likewise rise, with importers in Africa and the Middle East (to whom Brazil currently exports) likely targets. This will increase competition on global markets and prices will therefore fall. The European Commission expects that yields of beet in the EU will rise from 16.5 million tonnes in 2016 to 20-21 million tonnes by 2020. As a consequence, imports of sugar will slide from an average of 3.5 million tonnes per year between 2011 and 2016 to just 1.8 million tonnes annually for 2017 to 2020, while exports will rise from an average of 1.2 million tonnes per year to 4.0 million tonnes in the same periods, respectively.

- Demand from China for sugar (the world’s biggest importer of sugar) will tend to soften as growth in the Chinese economy more generally slows. The IMF forecasts growth rates for China of 6.5%, 6.3% and 6.2% for 2018, 2019 and 2020, respectively, figures which compare unfavorably with the double-digit growth rates seen in 2010-2012. Growth in demand for sugar in the Chinese market has also been weakening and in 2016-2017, this grew by just 1%, compared to 3% per year in 2011-2014. Moreover, the Chinese government plans to reduce its stockholdings of sugar since at present, its buffer stock of sugar stands at over 2 million tonnes. The plan is to sell off this stock at 10-15% below market prices and to impose higher over-quota import tariffs, which have been raised from the previous rate of 50% to 90% for 2018 and 85% for 2019.

- The expectation generally is that the global supply of sugar will expand rapidly, outpacing only a slight strengthening in demand. As a result, the global stock of sugar is expected to steadily increase and this situation will keep prices depressed. Prices for raw sugar for 2018-2020 are therefore forecast to be in the range 15.0-16.5 cents/lb, compared to 15.8 cents/lb in 2017.

- From 2018, the domestic sugar sector may be affected by changes to production and marketing as a consequence of structural changes in the sector, but these will not be pronounced.

- The imposition of a sugar tax on soft drinks[13] will reduce demand for sugar from domestic soft drink manufacturers. This duty is collected from manufacturers of soft drinks at a rate calculated on the amount of sugar in their products (i.e. the higher the sugar content, the higher the rate) and so manufacturers are likely to adjust their products and to reduce the amount of sugar that they contain. On the other hand, the duty is not set at a particularly high rate and total demand for sugar from soft drinks manufacturers accounts for only some 5-6% of all Thai sugar production so the impacts of this policy on sugar producers are likely to be limited.

- Amendments to the Sugarcane and Sugar Act will bring about changes in the structure of the domestic sugarcane and sugar industry. Most importantly, these changes will reduce government support for sugar exports but currently, the details of the reform are still being discussed. Progress on this is as follows.

- On the 15th January 2018 and in accordance with article 44 of the constitution, the National Council for Peace and Order issued an order announcing that to support structural reform of the sugarcane and sugar sector, for the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 seasons, the price of refined sugar would be allowed to float freely. This move will not only change the way that the price of sugar is calculated for distribution domestically but will also have consequences for the whole domestic market. The most important of these are described below.

- The price of domestic sugar will switch from being set by the authorities to floating freely and moving in line with world prices. The reference price on the domestic market will now combine the London price of No. 5 white refined sugar with the price of Thai premium refined sugar[14] and this will be calculated in Thai baht. This will then determine the monthly minimum price of sugar sold in Thailand, though these changes may have unwelcome effects on the income of those selling to the domestic market since for many years, the domestic price of sugar has been fixed at a point higher than that which has prevailed on global exchanges. In January 2018, domestic prices of refined sugar and pure refined sugar averaged at 17.22 and 18.33/kg, respectively (fell by THB3 from the previous fixed price specified by government)

- The repeal of the quota system will affect all three of its parts, that is ‘quota A’, which determines sales to the domestic market, ‘quota B’, which determines exports by the Thai Cane and Sugar Corporation, and ‘quota C’, which determines exports by sugar millers. Under the new system, sugar manufacturers will instead need to maintain a buffer security reserve of 250,000 tonnes/month to protect against the possibility of shortages in Thailand but it is thought that the repeal of the quota system will not have serious consequences for sugar mills because the quantity of sugar which they are required to reserve is similar to requirements imposed under the old system. The effects of removing ‘quota B’ and ‘quota C’, which determine exports, on operators’ income will vary from player to player and will depend on the ability of each to anticipate movements in prices on world markets since sellers will now have more freedom to consider what action to take when distributing to domestic and export markets.

- The THB 5/kg collections from factory-gate sugar prices for the Cane and Sugar Fund will be cancelled and replaced with contributions to a new fund. These will be calculated on the difference between factory-gate prices (determined by an analysis of the market) and the minimum price (determined with reference to the London price of No. 5 sugar and premium Thai sugar). This new formula will lead to greater uncertainties over what level of contributions will be required of mills since the exact level of the charges will depend on domestic and international markets and in the case that factory-gate prices are lower than the minimum price, no contributions at all will be required. However, at present, it is not clear how exactly factory-gate prices will be determined.

- Other details of the amendments to the Act being considered are likely to come into force for the 2018-2019 growing season, that is with effect from November 2018. This is with the exception of changes to the way in which sugar is distributed domestically as announced in the government order of 15/01/2018, and which have already come into effect for the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 growing seasons. These additional changes will have the following effects.

- Opening the domestic market for sugar to imports is not thought likely to have significant impacts on domestic players because imports will be under the control of the authorities, which will periodically issue operators’ permits.

- Changes to the definition of ‘sugar’ in the Act, as proposed by sugarcane growers, would have effects on industry revenues. If ‘sugar’ is expanded to cover by-products of sugar production such as molasses and sugarcane juice, and income from the sale of these is then included with the sale of sugar for the purpose of calculating revenue-sharing agreements between sugarcane growers and sugar mills. This will have consequences for revenues because in this case, sugar millers would no longer be able to claim all the revenues arising from the sale of these items.

- It is likely that the Cane and Sugar Fund will be removed from the process of making compensation payments when there is a difference between the preliminary and final sugarcane prices. This will be especially important when the preliminary price is higher than the final price (that is, the mill has effectively overpaid in advance for sugarcane), and it is expected that the amendments to the Sugarcane and Sugar Act will specify that sugar mills will be responsible for collecting overpayments from sugarcane growers themselves by setting this overpayment against purchases in the next growing season. This is in sharp contrast to the earlier system, under which the Cane and Sugar Fund acted as an intermediary, making compensation payments within the same season. This change will likely have two effects. (i) Compensation transfers will take longer to make than they did in the past. (ii) When growers have to make repayments to mills and these are deducted from sales in the following season, the income for sugarcane growers will fall and if the government and/or producers do not implement measures to help support growers for this loss of income, this may lead to less sugarcane being available for processing in the following season.

[1] Sugars are found throughout plant tissue but sugarcane and beet have sufficiently high concentrations that they can be cultivated forcommercial production of sugar.

[2] This is calculated from the sugar content, that is the amount of sugar obtained per tonne of sugarcane and the price of the sugarcane which farmers are able to obtain but it does not include other costs of production and distribution. These add around another 2.5-3.5 cents]lb.

[3] Having examined the link between per capita GNP and per capita consumption of sugar, by Krungsri Research shows that there is a positive relationship between the size of a developing economy and sugar consumption and so economic growth in developing economies leads to growth in sugar consumption. The relationship is reversed in developed economies and as income rises, consumers in developing countries will increasingly consider the health consequences of sugar consumption and]or will have greater access to alternative sweeteners. Demand for sugar thus slows and the rate of consumption falls.

[4] The seven exporters of sugar are the Sugar Industry Trading Company, Thai Sugar Trading Corporation, K.S.L. Export Trading Company, T.I.S.S. Company, Pacific Sugar Corporation, Siam Sugar Export Corporation and World Sugar Export Corporation.

[5] Exports from the Thai Cane and Sugar Corporation, a joint venture between sugarcane growers, sugar processors, and the Thai state.

[6] Controlled by the Department of Internal Trade, a part of the Ministry of Commerce.

[7] Calculated from the export and domestic prices of sugar, weighted according to the proportions distributed to these markets.

[8] The preliminary price of sugarcane, estimated by the Office of the Cane and Sugar Board and announced in November at the start of the growing season, is the initial compensation which sugarcane growers receive from mills, who pay this money in advance at the beginning of the sugarcane season. The preliminary price should be no less than 80% of estimated income, which is calculated on the costs of producing sugarcane and processing the sugar. The final price of sugarcane is the price realized by the sugarcane and which sugarcane growers will receive at the finish of the season in October, which is when the final price is announced, and this is calculated on the basis of the actual price for sugar on domestic and export markets.

[9] In 2017, production capacity for ethanol manufactured from sugarcane and molasses totaled 2.49 million liters]day. Annual demand for molasses exceeded 3 million tonnes and that for sugarcane came to approximately 0.8 million tonnes annually.

[10] Total domestic electricity production from bagasse comes to around 900 megawatts. This energy is consumed by sugar processors themselves and distributed to nearby areas.

[11] Analysis by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the climate over the past 60 years indicates that strong El Niños and La Niñas should occur roughly every 12-15 years; the last strong El Niño and El Niña were in respectively 2015-2016 and 2010-2011.

[12] This is partly a consequence of a case brought by Brazil under WTO rules against Thailand. The complaint was that Thai policy unfairly supports exports of sugar by specifying export quotas and by setting domestic prices which are higher than export prices. In addition, the THB 5]kg transfers made by the Cane and Sugar Fund from the retail price of sugar to sugarcane growers are a subsidy to producers, who therefore carry costs which do not reflect reality and this gives Thai operators an unfair advantage when compared to other exporters.

[13] The sugar tax is set at six rates: (i) A sweetness level of 0-6 grams per 100 ml is tax exempt; (ii) a sweetness level of 6-8 grams per 100 ml incurs a duty of THB 0.1]liter; (3) a sweetness level of 8-10 grams per 100 ml incurs a duty of THB 0.3]liter; (iv) a sweetness level of 10-14 grams per 100 ml incurs a duty of THB 0.5]liter; (v) a sweetness level of 14-18 grams per 100 ml incurs a duty of THB 1]liter; and (vi) a sweetness level of 18 grams per 100 ml and over incurs a duty of THB 1]liter. These regulations will be in effect from 16thSeptember 2017 until 30th September 2019. Following that, the government will review and adjust the rates in 2019 and again in 2021.

[14] This is an addition made for selling Thai sugar for export although the premium fee may be either positive or negative, depending on (i) the market price of sugar on the day export, (ii) demand from buyers, and (iii) quality and service.

.webp.aspx)